Abstract

Omidubicel is a cord blood derived ex vivo-expanded cell therapy product that has demonstrated faster engraftment and fewer infections compared with unmanipulated umbilical cord blood (UCB) in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. While the early benefits of omidubicel have been established, long-term outcomes are still unknown. We report on a planned pooled analysis of five multi-center clinical trials, featuring 105 patients with hematologic malignancies or sickle cell hemoglobinopathy who underwent omidubicel transplantation at 26 academic transplant centers worldwide. With a median follow-up of 22 months (range, 0.3–122), the 3-year estimated overall survival and disease-free survival were 62.5% and 54.0%, respectively. With up to 10 years follow-up, omidubicel showed durable trilineage hematopoiesis. Serial quantitative assessments of CD3+, CD4+, CD8+, CD19+, CD116+CD56+, and CD123+ immune subsets revealed median counts remaining within normal range through up to 8 years follow-up. Secondary graft failure occurred in 5 patients (5%) in the first year, with no late cases reported. One case of donor-derived myeloid neoplasm was reported at 40 months post-transplant. This was also observed in a control arm patient who received only unmanipulated UCB. In conclusion, omidubicel demonstrated stable trilineage hematopoiesis, immune competence, and graft durability in extended follow-up.

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) remains the only potentially curative treatment for most hematologic malignancies. Umbilical cord blood (UCB) provides an important alternative source of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) for allogeneic HCT, but its use is constrained by low cell dose. Early attempts at UCB expansion were able to achieve robust ex vivo expansion of stem cells, but have mostly relied on a co-administered unmanipulated UCB unit for long-term engraftment.1–3

Omidubicel is a first-in-class, UCB-derived cellular therapy product expanded using nicotinamide.4 It was the first ex vivo expanded stem cell graft to be transplanted as a standalone unit. A recent randomized multicenter phase III trial of allogeneic HCT with standalone omidubicel showed faster engraftment and fewer infectious complications compared to unmanipulated UCB transplantation.5 While the early benefits of omidubicel have been demonstrated, long-term outcomes are unknown.6 Given the theoretical concerns surrounding durability of expanded stem cell grafts, we set out to perform a long-term follow-up study to confirm the safety, immune function, and graft durability of omidubicel transplantation. Here we report on a pooled analysis of five multi-center clinical trials evaluating omidubicel transplantation in patients with hematologic malignancies and sickle cell hemoglobinopathy.

Methods:

In this planned secondary analysis (NCT02039557), long-term outcomes were pooled from five clinical trials evaluating omidubicel transplantation between January 2011 and April 2021. Four studies (HEME1: NCT01221857, HEME2: NCT01816230, HEME3: NCT02730299, SCD1: NCT01590628) have previously been reported, while the remaining (SCD2: NCT02504619) closed early due to sponsor decision.5,7–9 Three trials assessed patients with hematologic malignancies, and two enrolled patients with sickle cell hemoglobinopathy (Table 1). Patients treated in the two phase I studies received omidubicel co-administered with an unmanipulated UCB graft. All patients received myeloablative conditioning regimens, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis comprised of a calcineurin inhibitor and mycophenolate mofetil. Additional protocol information may be found in the supplemental appendix. In order to examine omidubicel-specific outcomes, all patients who fully engrafted with an unmanipulated UCB were excluded from this long-term follow-up study. Written informed consent was provided by all patients, and the study was approved by each site’s institutional review board. Survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Cumulative incidences were calculated via competing risk analysis, with the competing risks being death, graft failure, and relapse. Statistical analyses were performed using R 4.1.2 (R Core Team, Austria) and Graphpad Prism (Graphpad Software, USA).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Clinical Trial

| NCT01221857 HEME1 (N = 9) | NCT01816230 HEME2 (N = 36) | NCT02730299 HEME3 (N = 52) | NCT01590628 SCD1 (N = 7) | NCT02504619 SCD2 (N = 1) | Total (N = 105) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Phase | I | I / II | III | I | I / II | |

|

| ||||||

| Trial Design | Single Arm | Single Arm | Two Arm RCT‡ | Single Arm | Single Arm | |

|

| ||||||

| Disease Type, N (%) | ||||||

| AML | 4 (44%) | 17 (47%) | 22 (42%) | 0 | 0 | 43 (41%) |

| ALL | 1 (11%) | 9 (25%) | 18 (35%) | 0 | 0 | 28 (27%) |

| MDS | 2 (22%) | 6 (17%) | 5 (10%) | 0 | 0 | 13 (12%) |

| Sickle Cell Hemoglobinopathy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 (100%) | 1 (100%) | 8 (8%) |

| Other | 2 (22%) | 4 (11%) | 7 (13%) | 0 | 0 | 13 (12%) |

|

| ||||||

| Disease Risk Index, N (%) | ||||||

| Low/Moderate | 6 (67%) | 22 (61%) | 34 (65%) | 0 | 0 | 62 (59%) |

| High/Very High | 2 (22%) | 12 (33%) | 18 (35%) | 0 | 0 | 32 (30%) |

| Unknown/Unevaluable | 1 (11%) | 2 (6%) | 0 | 7 (100%) | 1 (100%) | 11 (10%) |

|

| ||||||

| Transplantation Strategy, N (%) | ||||||

| Double Cord | 9 (100%) | 0 | 0 | 4 (57%) | 0 | 13 (12%) |

| Single Cord | 0 | 36 (100%) | 52 (100%) | 3 (43%) | 1 (100%) | 92 (88%) |

|

| ||||||

| Omidubicel Cell Dose, Median (range) | ||||||

| TNC Dose (x 107 cells/kg) | 3.9 (2.1–8.5) | 4.9 (2.0–16.3) | 4.7 (1.7–12.4) | 7.7 (4.2–11.8) | 28.8 | 4.8 (1.7–28.8) |

| CD34 Dose (x 106 cells/kg) | 3.7 (0.9–18.3) | 6.3 (1.4–14.9) | 9.0 (2.1–47.6) | 12.7 (6.6–19.0) | 50.8 | 7.3 (0.9–50.8) |

|

| ||||||

| Omidubicel HLA Match, N (%) | ||||||

| 4 / 6 | 6 (67%) | 26 (72%) | 36 (69%) | 7 (100%) | 1 (100%) | 76 (72%) |

| 5 / 6 | 3 (33%) | 8 (22%) | 15 (29%) | 0 | 0 | 26 (25%) |

| 6 / 6 | 0 | 2 (6%) | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 3 (3%) |

|

| ||||||

| Conditioning Regimen*, N (%) | ||||||

| TBI/Flu/Cy | 2 (22%) | 8 (22%) | 20 (38%) | 0 | 0 | 30 (29%) |

| TBI/Flu/Thio | 0 | 2 (6%) | 7 (13%) | 0 | 0 | 9 (9%) |

| TBI/Flu | 7 (78%) | 5 (14%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 (11%) |

| Bu/Flu/Clo | 0 | 2 (6%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (2%) |

| Bu/Flu/Thio | 0 | 19 (53%) | 25 (48%) | 0 | 1 (100%) | 45 (43%) |

| Bu/Flu/Cy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 (86%) | 0 | 6 (6%) |

| Bu/Flu/ATG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (14%) | 0 | 1 (1%) |

|

| ||||||

| GVHD Prophylaxis, N (%) | ||||||

| Tacrolimus + MMF | 9 (100%) | 15 (42%) | 29 (56%) | 0 | 0 | 53 (50%) |

| Cyclosporine + MMF | 0 | 20 (56%) | 23 (44%) | 7 (100%) | 1 (100%) | 51 (49%) |

| MMF | 0 | 1 (3%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) |

|

| ||||||

| Engraftment Outcome, N (%) | ||||||

| Omidubicel | 7 (78%) | 33 (92%) | 50 (96%) | 6 (86%) | 1 (100%) | 97 (92%) |

| Mixed Chimerism | 1 (11%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (14%) | 0 | 2 (2%) |

| Primary Graft Failure | 1 (11%) | 2 (6%) | 2 (4%) | 0 | 0 | 5 (5%) |

| Death Before Engraftment | 0 | 1 (3%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) |

|

| ||||||

| Male Sex, N (%) | 4 (44%) | 20 (56%) | 27 (52%) | 3 (43%) | 1 (100%) | 55 (52%) |

|

| ||||||

| Non-White or Hispanic, N (%) | 3 (33%) | 7 (19%) | 23 (44%) | 7 (100%) | 1 (100%) | 41 (39%) |

|

| ||||||

| Age at Transplant, Median (range) | 45 (21 – 61) | 44 (13 – 62) | 40 (13 – 62) | 14 (8 – 16) | 2 | 42 (2 – 62) |

|

| ||||||

| Karnofsky PS ≥ 80%, N (%) | 9 (100%) | 35 (97%) | 51 (98%) | 6 (86%) | 1 (100%) | 102 (97%) |

Baseline characteristics of patients included in the long-term follow-up study by clinical trial. Patients received either single cord transplantation with omidubicel or double cord transplantation with omidubicel and an unmanipulated UCB unit. Patients who engrafted with UCB were excluded from this long-term follow up study.

Patients randomized to receive an unmanipulated UCB in the control arm of this phase III trial were not included in the study.

All conditioning regimens were myeloablative.

RCT: randomized controlled trial, UCB: umbilical cord blood, AML: acute myeloid leukemia, MDS: myelodysplastic syndrome, ALL: acute lymphoblastic leukemia, TBI: total body irradiation, Bu: busulfan, Flu: fludarabine, Cy: cyclophosphamide, Thio: thiotepa, Clo: clofarabine, ATG: antithymocyte globulin, PS: performance status, HLA: human leukocyte antigen, MMF: mycophenolate mofetil, GVHD: graft versus host disease.

Results:

Among 116 patients across 26 academic transplant centers who received omidubicel, either alone (N = 92) or co-administered with an unmanipulated UCB graft (N = 24), 11 fully engrafted with an unmanipulated UCB and were excluded from this analysis (Supplemental Figure 1). The remaining 105 patients were comprised of 97 (92%) who fully engrafted with omidubicel, 2 (2%) with mixed chimerism with omidubicel and an unmanipulated UCB, 5 (5%) with primary graft failure, and 1 (1%) who died before engraftment could be assessed. Baseline characteristics are described in Table 1. The median age at transplantation was 42 years (range, 2–62) and 41 (39%) belonged to a racial minority group. The most common indications for transplantation were acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (41%), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) (27%), myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) (12%), and sickle cell hemoglobinopathy (8%). At data cutoff in October 2021, the median duration of follow-up was 22.0 months (range, 0.3–122.5) for all included patients and 35.7 months (range, 11.7–122.5) among survivors.

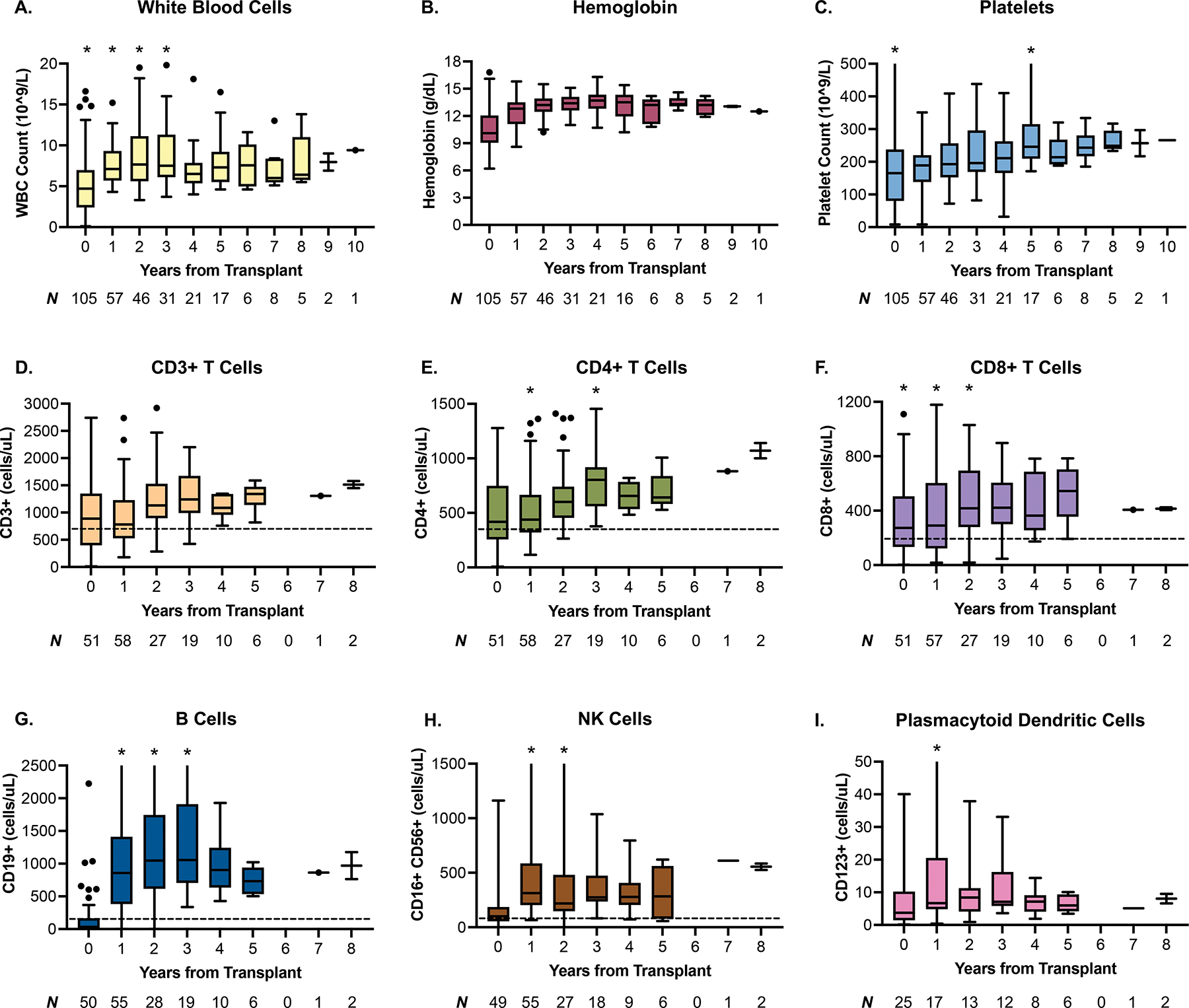

Omidubicel demonstrated durable long-term trilineage hematopoiesis with up to ten years follow-up (Figure 1A–1C). Similarly, lymphocyte subsets including median CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ T cell counts, as well as CD19+ (B-cell), CD116+CD56+ (NK cell), and CD123+ (plasmacytoid dendritic cell) counts, were within the expected range with up to 8 years follow-up (Figure 1D–1I). Secondary graft failure was observed in five patients (5%) at a median of 40 days post-transplant (range, 12–262) (Supplemental Table 1). Three of these patients underwent a second allogeneic HCT, one patient died without another transplant, and one patient with hemoglobinopathy received an autologous stem cell rescue infusion.

Figure 1.

Tukey box and whisker plots depicting trends of trilineage hematopoiesis and immune competence at up to 8–10 years post-transplant. A-C. Omidubicel demonstrates durable trilineage hematopoiesis over long-term follow-up. D-I. median counts of immune subsets fell within the normal range beginning at 1 year (early post-transplant immune reconstitution data not shown). Whiskers extend to the farthest points not considered outliers (1.5x the interquartile range from the median). Outliers are indicated by individual data points, while asterisk (*) indicate additional outlier points beyond the range of the figure. The lower limit of normal for various immune subsets are indicated by the dotted line, where available. WBC: white blood cells, NK cells: natural killer cells.

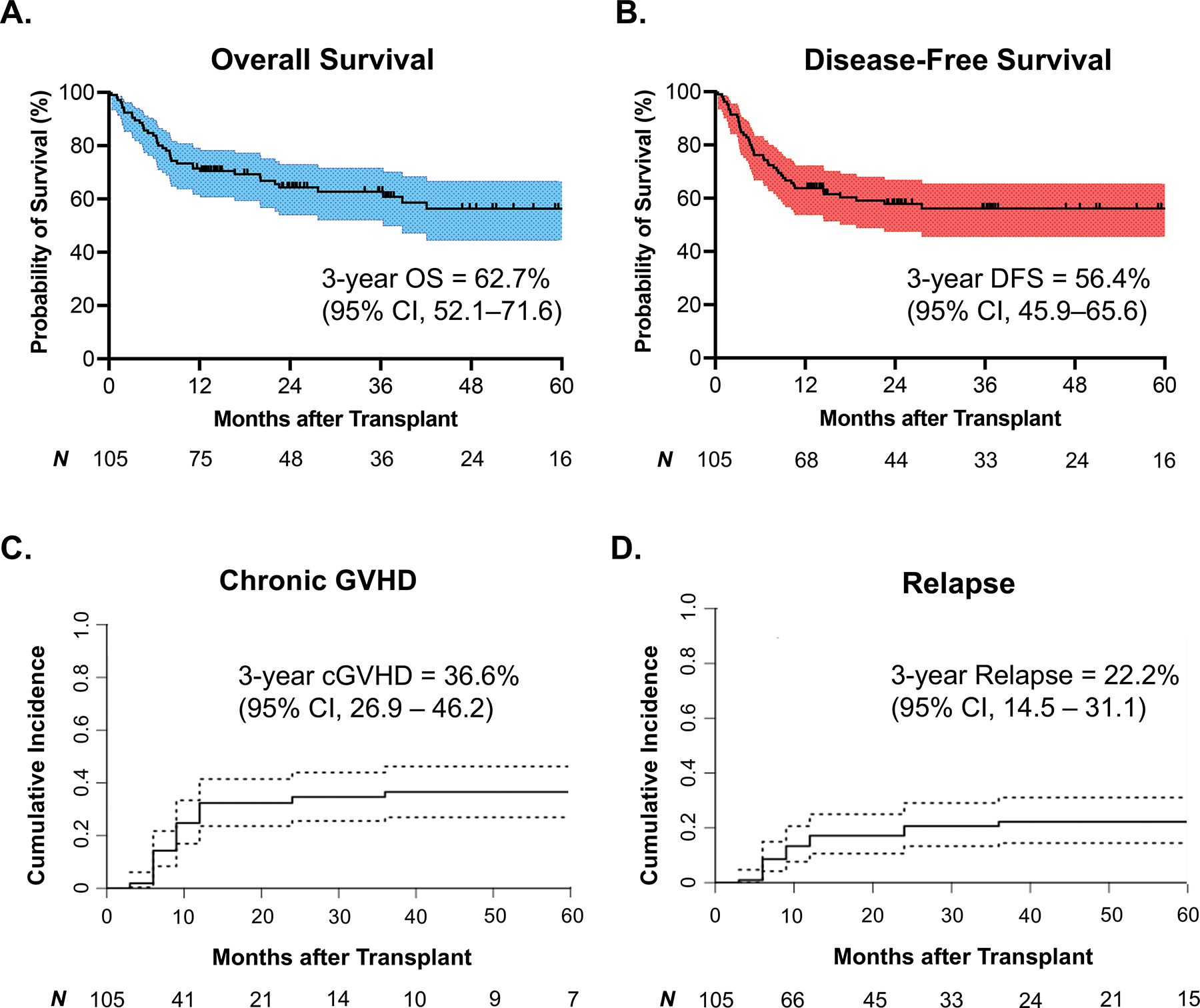

The estimated 3-year overall survival and disease-free survival were 62.7% (95% CI, 52.1–71.6) and 56.4% (95% CI, 45.9–65.6), respectively (Figure 2A, 2B). The most common primary causes of death were disease relapse (N = 16), infection (N = 11), and acute GVHD (N = 6). The 3-year cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD was 36.6% (95% CI, 26.9–46.2) (Figure 2C). The maximum grade of chronic GVHD was predominantly mild (55%), with 33% and 13% experiencing moderate and severe disease, respectively. No deaths were attributed to chronic GVHD. The estimated 3-year cumulative incidence of disease relapse in all patients was 22.2% (95% CI, 14.5–31.1) (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Survival analyses and cumulative incidence estimates among all included patients (N = 105). A, B. Kaplan-Meier survival curves depicting overall survival and disease-free survival in all patients. C, D. Competing risk analyses estimating the cumulative incidences of chronic GVHD and disease relapse in all included patients. The competing risks for chronic GVHD were death from any cause, disease relapse, and graft failure. The competing risks for disease relapse were death from any cause and graft failure. cGVHD: chronic graft-versus-host disease, CI: confidence interval. OS: overall survival, DFS: disease-free survival, CI: confidence interval.

Regarding secondary hematologic malignancies, two patients (2%) were diagnosed with post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder at 17- and 20-months post-transplant. In addition, one patient with AML received omidubicel alone and later developed a donor-derived MDS at 40 months post-transplant, requiring a second allogeneic HCT (Supplemental Table 2). Of note, there was also a case of donor-derived AML in the control arm of the phase III trial. This patient with ALL received an unmanipulated UCB transplantation and therefore was not included in the study cohort, but is reported here for comparison.

Discussion:

Data on the long-term outcomes of ex vivo expanded stem cell grafts have been limited.3,10,11 This planned secondary analysis of pooled multi-institutional data provides the longest follow-up thus far of patients who received omidubicel. In our cohort, patients with long-term engraftment of omidubicel showed durable trilineage hematopoiesis and immune reconstitution. These findings demonstrate the reliability of omidubicel over extended durations and support future studies in younger populations in need of alternative stem cell donors for allogeneic HCT.

Three of 98 patients with hematologic malignancies (3%) experienced secondary graft failure, which is comparable to the 1–3% reported after allogeneic HCT from mobilized peripheral blood and bone marrow.12 The two remaining patients with secondary graft failure had sickle cell hemoglobinopathy, which is associated with an increased risk of graft rejection.13,14 Although there has been concern that ex vivo expansion technologies may detrimentally impact long-term repopulating HSPCs, the ability of the nicotinamide-expanded omidubicel to maintain durable engraftment and hematopoiesis without the need for a concurrent unmanipulated UCB graft suggests that repopulating activity has been preserved.15–17

Donor-derived myeloid neoplasms were an adverse event of special interest in this population due to the expansion of the HSPCs involved in omidubicel production. Genetic aberrations related to myeloid neoplasms are known to occur as early as in utero and can be detected at low levels in a small minority of cord blood units.18,19 Retrospective case series have estimated the real-world incidence of secondary donor-derived myeloid neoplasms in UCB transplantation to be in the range of 0.6–2%.20–23 We observed donor-derived MDS in a single patient (1%) who received omidubicel, which was mirrored by a similar case of donor-derived AML in a patient who did not receive an expanded graft, suggesting comparable rates between ex vivo expanded grafts and unmanipulated UCB. The overall incidence may have been higher in this cohort due to the increased vigilance during a clinical trial compared to real world practice in which donor cell origins are not routinely assessed. The utility of screening for pre-malignant clones in at-risk stem cell donors and cord blood units prior to allogeneic HCT is still unclear and requires further investigation.24,25

The results from this multi-center analysis support the long-term safety and durability of omidubicel, and may inform survivorship care in patients who undergo omidubicel transplantation. On August 1st, 2022, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration granted priority review to the biologics license application for omidubicel in allogeneic HCT.26 Notably, 39% of this study’s cohort were non-white, highlighting a key demographic with more limited donor availability.27 If approved for commercial use, omidubicel will expand the potential donor pool for these underrepresented racial minority groups.28 Future studies are still needed to compare outcomes of omidubicel with other stem cell sources.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank all of the patients, caregivers, and research and clinical staff involved in this study, without whom this study and the associated clinical trials would not have been possible. The authors would also like to acknowledge The Emmes Company for their support in data management, and Einat Galamidi-Cohen, who was involved in the initial clinical trial design while at Gamida Cell. Editorial support was provided by Evidence Scientific Solutions. Author Chenyu Lin was supported by the NIH/NHLBI T32 training grant HL007057-46.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

Authors MEH, GS, JS, and PM have received institutional research grants from Gamida Cell. RTM reports consultancy and/or advisory roles with Artiva Therapeutics, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Celgene, CRISPR Therapeutics, Incyte, Kite and Novartis, research funding from BMS and Novartis, DSMB for Athersys, Novartis, NMDP and Century Therapeutics, and patents with Athersys. The remaining authors have no disclosures.

Data Sharing Statement:

Individual participant data will not be shared. Queries about the data can be made to corresponding author or medicalinformation@gamidacell.com.

References:

- 1.Popat U, Mehta RS, Rezvani K, et al. : Enforced fucosylation of cord blood hematopoietic cells accelerates neutrophil and platelet engraftment after transplantation. Blood 125:2885–2892, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delaney C, Heimfeld S, Brashem-Stein C, et al. : Notch-mediated expansion of human cord blood progenitor cells capable of rapid myeloid reconstitution. Nat Med 16:232–6, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner JE Jr., Brunstein CG, Boitano AE, et al. : Phase I/II Trial of StemRegenin-1 Expanded Umbilical Cord Blood Hematopoietic Stem Cells Supports Testing as a Stand-Alone Graft. Cell Stem Cell 18:144–55, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peled T, Shoham H, Aschengrau D, et al. : Nicotinamide, a SIRT1 inhibitor, inhibits differentiation and facilitates expansion of hematopoietic progenitor cells with enhanced bone marrow homing and engraftment. Exp Hematol 40:342–55.e1, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horwitz ME, Stiff PJ, Cutler C, et al. : Omidubicel vs standard myeloablative umbilical cord blood transplantation: results of a phase 3 randomized study. Blood 138:1429–1440, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin C, Sajeev G, Stiff PJ, et al. : Health-Related Quality of Life Following Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation with Omidubicel Versus Umbilical Cord Blood. Transplant Cell Ther, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horwitz ME, Chao NJ, Rizzieri DA, et al. : Umbilical cord blood expansion with nicotinamide provides long-term multilineage engraftment. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 124:3121–3128, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horwitz ME, Wease S, Blackwell B, et al. : Phase I/II Study of Stem-Cell Transplantation Using a Single Cord Blood Unit Expanded Ex Vivo With Nicotinamide. J Clin Oncol 37:367–374, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parikh S, Brochstein JA, Galamidi E, et al. : Allogeneic stem cell transplantation with omidubicel in sickle cell disease. Blood Adv 5:843–852, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen S, Roy J, Lachance S, et al. : Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation using single UM171-expanded cord blood: a single-arm, phase 1–2 safety and feasibility study. Lancet Haematol 7:e134–e145, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Lima M, McNiece I, Robinson SN, et al. : Cord-blood engraftment with ex vivo mesenchymal-cell coculture. N Engl J Med 367:2305–15, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anasetti C, Logan BR, Lee SJ, et al. : Peripheral-Blood Stem Cells versus Bone Marrow from Unrelated Donors. New England Journal of Medicine 367:1487–1496, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson TM, Fuchs EJ: Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for sickle cell disease. Curr Opin Hematol 23:524–529, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bolaños-Meade J, Fuchs EJ, Luznik L, et al. : HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation with posttransplant cyclophosphamide expands the donor pool for patients with sickle cell disease. Blood 120:4285–4291, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelly SS, Sola CBS, de Lima M, et al. : Ex vivo expansion of cord blood. Bone Marrow Transplantation 44:673–681, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sica RA, Terzioglu MK, Mahmud D, et al. : Mechanistic Basis of ex Vivo Umbilical Cord Blood Stem Progenitor Cell Expansion. Stem Cell Rev Rep 16:628–638, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dahlberg A, Delaney C, Bernstein ID: Ex vivo expansion of human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Blood 117:6083–90, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams N, Lee J, Mitchell E, et al. : Life histories of myeloproliferative neoplasms inferred from phylogenies. Nature 602:162–168, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mori H, Colman SM, Xiao Z, et al. : Chromosome translocations and covert leukemic clones are generated during normal fetal development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99:8242–8247, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dietz AC, DeFor TE, Brunstein CG, et al. : Donor-derived myelodysplastic syndrome and acute leukaemia after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: incidence, natural history and treatment response. Br J Haematol 166:209–12, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ballen KK, Cutler C, Yeap BY, et al. : Donor-derived second hematologic malignancies after cord blood transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 16:1025–31, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang E, Hutchinson CB, Huang Q, et al. : Donor Cell–Derived Leukemias/Myelodysplastic Neoplasms in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients: A Clinicopathologic Study of 10 Cases and a Comprehensive Review of the Literature. American Journal of Clinical Pathology 135:525–540, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagamura-Inoue T, Kodo H, Takahashi TA, et al. : Four cases of donor cell-derived AML following unrelated cord blood transplantation for adult patients: experiences of the Tokyo Cord Blood Bank. Cytotherapy 9:727–8, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeZern AE, Gondek LP: Stem cell donors should be screened for CHIP. Blood Advances 4:784–788, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibson CJ, Lindsley RC: Stem cell donors should not be screened for clonal hematopoiesis. Blood Advances 4:789–792, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gamida Cell announces FDA acceptance of biologics license application for omidubicel with priority review, News Release, Gamida Cell Ltd, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gragert L, Eapen M, Williams E, et al. : HLA Match Likelihoods for Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Grafts in the U.S. Registry. New England Journal of Medicine 371:339–348, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gergis U, Khera N, Edwards ML, et al. : Abstract 6 Projected Impact of Omidubicel on Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Access and Outcomes for Patients with Hematologic Malignancies in the U.S. Stem Cells Transl Med 11:S8, 2022 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Individual participant data will not be shared. Queries about the data can be made to corresponding author or medicalinformation@gamidacell.com.