Abstract

Deconvolution of potential drug targets of the central nervous system (CNS) is particularly challenging because of the complicated structure and function of the brain. Here, a spatiotemporally resolved metabolomics and isotope tracing strategy was proposed and demonstrated to be powerful for deconvoluting and localizing potential targets of CNS drugs by using ambient mass spectrometry imaging. This strategy can map various substances including exogenous drugs, isotopically labeled metabolites, and various types of endogenous metabolites in the brain tissue sections to illustrate their microregional distribution pattern in the brain and locate drug action-related metabolic nodes and pathways. The strategy revealed that the sedative-hypnotic drug candidate YZG-331 was prominently distributed in the pineal gland and entered the thalamus and hypothalamus in relatively small amounts, and can increase glutamate decarboxylase activity to elevate γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) levels in the hypothalamus, agonize organic cation transporter 3 to release extracellular histamine into peripheral circulation. These findings emphasize the promising capability of spatiotemporally resolved metabolomics and isotope tracing to help elucidate the multiple targets and the mechanisms of action of CNS drugs.

Key words: Ambient mass spectrometry imaging, Spatiotemporally resolved metabolomics, Isotope tracing, Drug targets, Central nervous system, Drug candidate

Graphical abstract

A spatiotemporally resolved metabolomics and isotope tracing strategy has been proposed and validated for deconvoluting and localizing multi-targets of central nervous system drugs by ambient mass spectrometry imaging.

1. Introduction

The failure rate of drug development for neurological diseases is extremely high1,2. The deconvolution of potential targets is critical for successful drug development for the central nervous system (CNS). First, preclinically identification of the wrong targets is one of the main causes of high attrition rates in clinical trials3. Additionally, a more holistic understanding of binding targets can help in identifying potential off-targets, which is almost as important as defining the efficacy of CNS drugs4. Furthermore, multi-targeted drugs can be developed for new indications5 or aid in the design of improved next-generation compounds6.

Because of the intricate structure and function of the brain, multi-target deconvolution of CNS drugs is particularly challenging. Molecular neuroimaging that provides in vivo and spatially resolved measures of neurobiology, has proven informative for understanding the action of CNS drugs7. These mainly include positron emission tomography or single-photon emission computed tomography8,9, and magnetic resonance spectroscopy10. These imaging modalities allow for non-invasive, real-time, and in-body monitoring, but their analyte throughput is relatively low, which may limit their usefulness for multi-target discovery. In recent years, label-free mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) has emerged as a promising molecular imaging tool, as its high coverage and sensitivity allow simultaneous mapping of neurotransmitters, metabolites, and drugs in the brain11, 12, 13, 14, 15 and is particularly useful for probing brain metabolic heterogeneity12,13,16, 17, 18, 19, 20. Especially, its non-targeted nature21 helps in identifying multiple metabolic changes after drug administration. Based on these characteristics, MSI has been used to study brain neurobiology18 and pathophysiology16, and MSI-based spatially resolved metabolomics has enabled microregion-specific biomarker discovery in vivo and shed light on the mechanisms of action (MOAs) of CNS drugs22,23. Furthermore, MSI-based spatially resolved isotope tracing has been applied to probe various biological processes by providing the functional imaging data of isotopic lables24,25, but its application to drug development has not been reported. Currently, the bottleneck of MSI in discovering potential drug targets lies in ways to link metabolic biomarkers to protein targets in a unique biomedical pathway through pharmacological modulation. The combination of untargeted mapping of brain metabolic changes and targeted spatially resolved isotope tracing will allow for a deeper understanding of drug-induced metabolic activity, including transport and transformation of molecular species24, thus helping to address this bottleneck.

YZG-331 (N6-[(S)-1-(phenyl)-propyl]-adenine riboside, patent number: WO2011069294), a structure-modified drug candidate based on natural products from Gastrodia elata, has been preclinically identified with strong sedative and hypnotic effects26, 27, 28, 29. For example, orally administered YZG-331 could dose-dependently reduce spontaneous locomotor activity in ICR mice and significantly increase sleep duration in pentobarbital sodium-treated mice26. Although the sedative and hypnotic effects of YZG-331 are clear, its molecular targets have not been fully elucidated.

In this study, an MSI-based strategy that couples spatiotemporal metabolomics to isotope imaging was proposed to facilitate multi-target deconvolution of CNS drugs by using ambient air flow-assisted desorption electrospray ionization (AFADESI)-MSI (Fig. 1). A spatially resolved metabolomics approach and spatiotemporal analysis were applied to discover drug-related differential metabolites, and brain metabolic network matching and spatiotemporally resolved isotope tracing were used to further discover the altered metabolic pathways and nodes and their altered positions upon drug intervention. The disturbed nodes of metabolic transformation were further biologically validated to decipher potential molecular targets. This strategy was used to discover potential targets of the anti-insomnia drug candidate YZG-331, and provided a viable way to link metabolic biomarkers to protein targets in metabolic pathways. The multiple potential targets derived through this strategy will drive in-depth research into the MOAs of CNS drugs and provide comprehensive information on drug efficacy, safety, and repositioning.

Figure 1.

Strategy of the integrated MSI-based spatiotemporally resolved metabolomics and isotope tracing to deconvolute multiple targets of CNS drugs. MT, metabolite; TH, thalamus; PG, pineal gland; HP, hypothalamus; MB, midbrain; CB, cerebellum; CTX, cortex; CC, corpus callosum; PN, pons; MD, medulla.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Liquid chromatography‒mass spectrometry (LC/MS)-grade acetonitrile was obtained from Fisher (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Purified water was purchased from Wahaha (Hangzhou, China). Ammonium acetate, ammonium formate, diethyl ether and hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin were purchased from Sinopharm (Beijing, China). Acetic acid was obtained from TEDIA (Fairfield, USA). Formic acid was provided by Millipore (Merck, Burlington, MA, USA), and 0.9% NaCl was obtained from CSPC (Shijiazhuang, China). Histamine, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), 1-methyhistamine, decynium 22, S-adenosyl-l-methionine, and semicarbazide (SCZ) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Histamine-α,α,β,β-d4·2HCl was purchased from CDN isotopes (Quebec, Canada). [U–13C]glucose and isotopic histidine (Ring-2-13C) were obtained from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. (MA, USA). 4-Aminobutyric-2,2-d2 acid (GABA-d2) was purchased from ZZBIO Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Corticosterone, β-estradiol, 2-amino-2-norbornanecarboxylic acid (BCH), and amodiaquine dihydrochloride were purchased from MedChemExpress (Shanghai, China). YZG-331 was kindly provided by Professor Jiangong Shi (Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS), Beijing, China).

2.2. Animal experiments

The animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care & Welfare Committee (Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China). Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats (female, 180–200 g) were purchased from Charles River (Beijing, China). The SD rats were divided into 7 groups, consisting of a control group and 6 administration groups, and 3 rats of each group were sacrificed 5, 10, 30 min, 2, 4 and 8 h after the intravenous injection of 50 mg/kg YZG-331 in 15% (w/v) hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin prepared in saline. Control rats were injected intravenously with an equal volume of 15% (w/v) hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin made up in saline. They were sacrificed with diethyl ether. The entire brain of each rat was immediately removed, placed on ice, washed with cold saline, and then stored at −80 °C until sectioning. Brain tissue was embedded with optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Leica, Germany) and sectioned into 20 μm thick sagittal sections using a cryostat microtome (Leica CM 1860, Leica Microsystem, Germany), and the brain slices were thaw-mounted on a positively-charged microscope slide (Thermo Scientific, USA), and stored at −80 °C. To maintain consistency of brain tissue sections, sagittal sections were cut within a maximum of 1 mm along the sagittal suture to ensure that the pineal gland was included. All brain sections were dried at −20 °C for 1 h, and then at room temperature for 2 h prior to MSI analysis. Moreover, an adjacent brain section was obtained for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining or Nissl staining. Localization of brain microregions is performed by matching them to adjacent stained brain sections to ensure the microregional consistency of each brain tissue section.

Animal experiments for spatially resolved isotope tracing of GABA and histamine, and other animal experiments are described in Section 1.1 of Supporting Information.

2.3. AFADESI-MSI analysis

AFADESI-MSI analysis11 was performed in both positive and negative ion modes on a Q-Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) over an m/z range of 50–500 at a mass resolution of 70,000. A mixture of acetonitrile and water (8:2, v/v) was used as the spray solvent at a flow rate of 5 or 6 μL/min. The sprayer voltages were set to 7000 V in positive ion mode and −7000 V in negative ion mode. The transporting gas flow was 45 L/min, the capillary temperature was 350 °C, the spray gas pressure was 0.7 MPa, and the automated gain control (AGC) target was 5 E6. The MSI experiments were performed by continuously scanning the tissue surface in the x-direction at a constant speed of 160 μm/s, with a vertical step of 200 μm separating the adjacent lines in the y-direction.

2.4. Histamine release from RBL-2H3 cells

Cell culture of RBL-2H3 cells was described in Section 1.7 of the Supporting Information. To study different dosage concentrations of YZG-331, cells were separated with 0.25% trypsin–EDTA before the test, and 3 × 105 cells/mL were cultured in a 6-well plate. After 48 h, 1 mL of YZG-331 solutions at 0, 1, 5, 30, 50, 100, 200, 500, and 1000 μmol/L, were separately administered to the cells in triplicate. After 1 h, the cell supernatants were collected, and the cells were washed with Tyrode's solution and lysed with 1 mL of 1% Triton X100 (all from Solarbio, Beijing, China) at 4 °C. The cell supernatants and the cell lysates were centrifuged at 15,000 r/min for 5 min, and 0.5 mL of the supernatants were collected. Then, 10% ascorbic acid containing histamine-α,α,β,β-d4 as an internal standard was added to the supernatants and precipitated with ice-cold acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid after vortexing, and the supernatants were collected as test solutions after centrifugation at 15,000 r/min for 5 min. To examine different incubation times, 200 μmol/L YZG-331 was administered at 5, 10, 30, 45 min, 1, 1.5 and 2 h, and the sample preparation of the cell supernatants and the cell was the same as above. To test whether YZG-331 induced uptake of histidine via the large neutral amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1), solutions of LAT1 inhibitor BCH ranging from 0.1 to 10 mmol/L were preincubated with the cells for 10 min, and then BCH was administrated alone or in combination with 200 μmol/L YZG-331. After 1 h, the cell supernatants and the cells were processed as above. To test whether YZG-331 induced histamine release via the organic cation transporter 3 (OCT3), solutions of OCT3 transporter inhibitors, namely, decynium 22, corticosterone, and β-estradiol, ranging from 0.001 to 10 μmol/L were preincubated with the cells for 10–15 min, and then these OCT3 inhibitors were administered alone or in combination with 200 μmol/L YZG-331. After 1 h, the cell supernatants and the cells were processed as described above. To validate YZG-331-stimulated histamine release from RBL-cells, we separately conducted two assays: (1) Solutions containing 50 μg/mL isotopic histidine alone or combined with 200 μmol/L YZG-331 were added to the cell culture medium at 5, 20 min and 1 h; (2) After 15 min of preincubation with OCT3 inhibitor, solutions containing 42 μg/mL isotopic histidine alone or in combination with OCT3 inhibitor as a control group and each same group spiked with 200 μmol/L YZG-331 as an administration group were added for 1 h to the cell culture medium. All cell supernatants and cells were processed as previously described above. All test solutions were analyzed using ultra-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC–MS/MS) as described in Section 1.3 of the Supporting Methods. Histamine release was calculated as a percentage of extracellular histamine content to total histamine content (extracellular + intracellular).

2.5. GAD assay

Crude enzyme (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) of glutamate decarboxylase (GAD) briefly purified from engineered Escherichia coli was used. Next, 300x of the crude GAD solution was diluted with acetate buffer (pH 4.6) to obtain the appropriate enzyme activity. One hundred microliters of test compound (YZG-331 or SCZ) or vehicle, and 100 μL of 10 μg/mL GABA-d2 as an internal standard were preincubated with 100 μL of diluted GAD solution in acetate buffer at pH 4.6 for 20 min at 37 °C. The reaction was started by adding 1000 μmol/L l-glutamate for an additional 1 h of incubation and terminated by adding 1 mL of ice-cold acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid. The mixtures were centrifuged at 15,000 r/min for 5 min and the supernatants were analyzed by UPLC–MS/MS as described in Section 1.3 of the Supporting Methods.

2.6. Data processing

We use a previously established spatially resolved metabolomics approach11,22,30 to discover discriminatory metabolites in brain microregions. For MSI analysis of brain samples, the collected .raw files were converted into .cdf format by Xcalibur 2.3 (Thermo Scientific, USA) and then imported into custom-developed imaging software MassImager31 (Chemmind Technologies, Beijing, China) for ion image reconstructions11,30. After background subtraction, region-specific MS profiles were extracted by matching high-spatial resolution H&E or Nissl images. The MS profiles were exported as a .txt file and then imported into Markerview 1.2.1 (AB SCIEX, USA) for peak picking, peak alignment, and isotope removal (mass tolerance was 5 ppm). The discriminating endogenous molecules of different tissue microregions were screened by a supervised statistical analysis method: OPLS-DA run by SIMCA-P software (Version 14.1, Umetrics, Umeå, Sweden). Differential metabolites with variable importance for the projection (VIP) value > 1, P < 0.05 in Student's t-test and a fold change (FC) value of >1.2 or < 0.8 were screened and further confirmed by the MSI mapping. We used Excel 2016, GraphPad Prism 8 (San Diego, CA, USA) and other software to perform t tests, fold change calculations and data processing. The color scale for fold change was created in Excel14.

3. Results and discussion

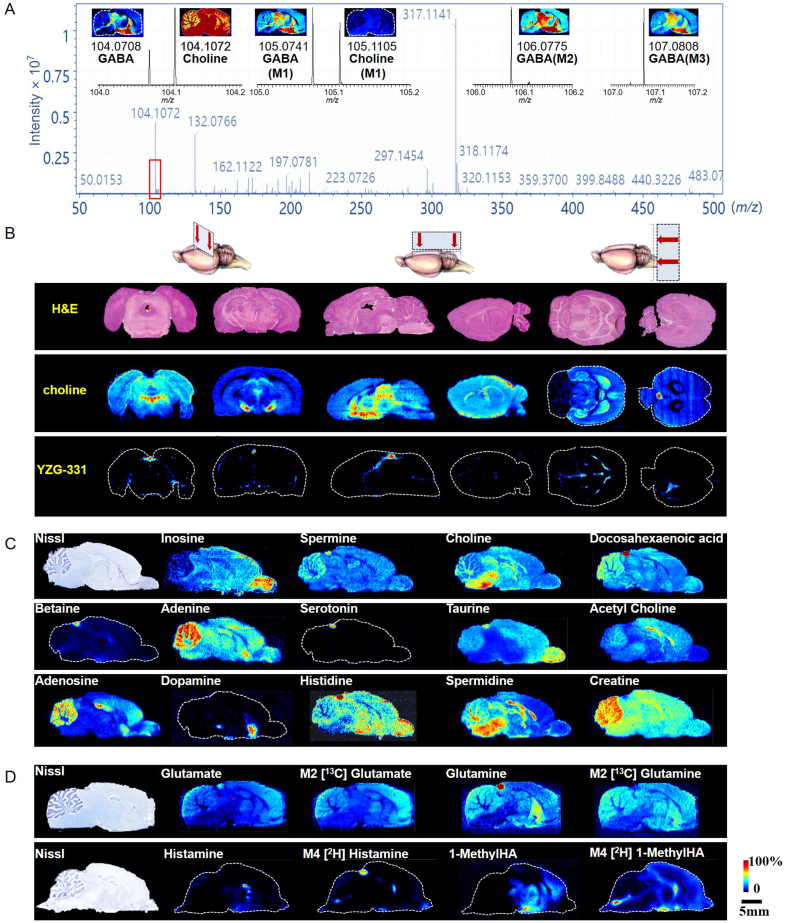

3.1. Mapping drugs and endogenous metabolites and isotopic metabolites in the brain by AFADESI-MSI

After optimization based on our previous report11, the established AFADESI-MSI method proved powerful not only for mapping the drug (Fig. 2B), neurotransmitters, and other polar endogenous metabolites (Fig. 2C) in rat brains, but also for visualizing isotopic tracers and their downstream substances (Fig. 2A and D, Supporting Information Fig. S2) in specific metabolic pathways11,12. The representative mass spectra obtained via AFADESI-MSI after isotopic glucose infusion can detect more than one thousand ion peaks with high specificity (Fig. 2A). For example, in the m/z range 104–108, six compounds, namely choline, GABA, and their isotopomers, were unequivocally differentiated and mapped (Fig. 2A). In addition, more than 180 brain metabolites were annotated, including amino acids, neurotransmitters (NTs), nucleotides, steroids, fatty acids and others (Supporting Information Table S1)11. More than 40 Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways were covered, 23 of which were enriched with more than three annotated metabolites (Supporting Information Fig. S1). In particular, this approach enables high-throughput mapping of function-specific metabolite collection. By the method, sleeping-related NTs and metabolites, such as GABA, histamine, serotonin, dopamine, and adenosine, were simultaneously mapped (Fig. 2). For example, adenosine, which accumulates during waking hours and ultimately triggers the need for sleep, was highly expressed in the cerebellum, hippocampus, and cortex (Fig. 2C), where the adenosine A1 receptor is also highly expressed32.

Figure 2.

The distribution of YZG-331 and metabolites in the rat brain. (A) A mass spectrum acquired by AFADESI-MSI with magnification of the m/z 104–108 region, the intensity thresholds for MSI imaging of choline and GABA isotopomers were 2.5 × 106 and 2.0 × 105, respectively; (B) H&E staining images of and MS images of choline and YZG-331 in coronal, sagittal and cross-sections of the rat brain; (C) Nissl staining images and distribution of neurotransmitters and other metabolites in a same brain section; (D) Nissl staining images and distribution of unlabeled and isotopic metabolites in specific metabolic pathways in the rat brain. Mn, where n indicates the number of heavy atoms in the molecule. GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; 1-MethylHA, 1-methylhistamine.

Moreover, this method can trace different isotopomers of pathway metabolites with high coverage. Following intravenous infusion of isotopic [U–13C]glucose, the unlabeled and mass isotopomers of four intermediates of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, citric acid (isocitric acid), succinate, fumarate, and malate, along with glucose and related compounds (glutamine, glutamate, and GABA), were unambiguously outlined (Supporting Information Fig. S2 and Table S2). Furthermore, the method can sensitively capture the spatial discrepancies between endogenous unlabeled metabolites and exogenous isotopic parallels. For example, endogenous histamine was mainly expressed in the thalamus and hypothalamus, whereas intravenously administered isotopic histamine was mainly localized in the pineal gland of the rat brain (Fig. 2D). These differences in distribution can be traced to different pathways and sources and used to understand the kinetic characteristics of a particular metabolic pathway across organs or brain regions.

3.2. Spatiotemporal metabolomics analysis to localize the drug and alternated metabolic pathways and nodes

To investigate whether YZG-331 enters the brain and its distribution in brain microregions, the coronal, transverse, and sagittal sections of the rat brain were compared using MSI (Fig. 2B). We chose sagittal brain sections of the brain for subsequent analysis because they contained the most functional microregions and clearly depicted the distribution of the drug and metabolites (Fig. 2B and C). Furthermore, the spatiotemporal distribution (Fig. 3C and D) showed that YZG-331 was distributed mainly in the pineal gland, and entered the thalamus and hypothalamus in relatively small amounts.

Figure 3.

The screening of differential metabolites and spatiotemporal distribution of YZG-331 and the differential metabolites in the rat brain (n = 3). (A) Enriched metabolic pathways. The green box highlights pathways with pathway impact >0.08; (B) The bubble diagram of discriminating metabolites in terms of P values (axis x), FC values (axis y), and the correlation coefficient (R2) between YZG-331 and metabolites (size of bubble); (C) The relative changes in YZG-331, GABA, and histamine; the change ratio of AUC= (AUC after drug‒AUC before drug)/AUC before drug; (D) The spatiotemporal distribution of YZG-331 and drug-related metabolites. Pl, plasma; TH, thalamus; PG, pineal gland; HP, hypothalamus; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; HA, histamine; 1-MethylHA, 1-methylhistamine; AUC, area under the curve.

The 10-min administered and control groups were used to screen differential metabolites. Eight differential metabolites were screened using the method described in section 2.6, five of which, including histamine, betaine, taurine, adenosine, and melatonin, were obtained from the pineal gland, and three, including GABA, 1-methylhistamine, and an unknown compound, were acquired from the hypothalamus and thalamus (Supporting Information Table S3). Metabolic pathway analysis results produced by MetaboAnalyst showed that the differential metabolites were mainly enriched in three pathways, with the most significant enrichment occurring in the histidine metabolism pathway (Fig. 3A). Drug-related metabolites were further screened by an assessment of FC values and P values and correlation coefficients with drug concentration (Supporting Information Table S3). The results showed that histamine, 1-methylhistamine, and GABA were the most relevant metabolites (Fig. 3B).

Histamine had the highest FC value, with up to a 10.6-fold in the pineal gland among the metabolites screened (Table S3). The histamine level (Fig. 3C) in the plasma and pineal gland rapidly increased to reach the highest concentration after 5 min of administration, and then the histamine level decreased and slightly increased at 30 min. The trends in change in histamine levels of the plasma and pineal glands was consistent with that of YZG-331. In fact, the correlation coefficient of the change in levels between histamine and the drug substance in the pineal gland was as high as 0.92 (Table S3).

As a catabolite of histamine, the change in 1-methylhistamine level (Fig. 3C and Fig. S3B) was synchronized with histamine levels in the hypothalamus. Although both 1-methylhistamine and histamine increased in the hypothalamus, 1-methylhistamine increased approximately 1.5-fold, whereas histamine increased approximately 0.5-fold, suggesting that the catabolic rate of histamine is possibly faster than its synthesis.

GABA (Fig. 3C and D) was rapidly elevated 5 min after YZG-331 administration, and a high level of brain GABA persisted until 8 h post-administration. The area under the curve (AUC) showed that GABA levels in the hypothalamus increased approximately 1-fold.

Because the key metabolites do not represent the full map of events, we extended our investigations to related metabolic pathways to examine the nodes altered by the drug. Previously, we used the AFADESI-MSI method combined with MetaboAnalyst and KEGG database for the high-throughput construction of a metabolic network map of the rat brain, which included important neurotransmitters and metabolites, involving 20 metabolic pathways and their connective relationships11. By enriching the drug-related differential metabolites with the brain map without prior knowledge, two relevant metabolic pathways were found to be altered upon drug stimulation including GABAergic synapse and histidine metabolism (Supporting Information Fig. S4 and Fig. 4). For convenience, we refer to these as GABA- and histamine-related metabolic pathways, respectively. The GABAergic synapse pathway involves GABA synthesis and metabolism occurring at the level of the TCA cycle33, 34, 35 and includes a small module consisting of glutamine, glutamate, and GABA (Figure 4, Figure 7). No significant changes in the levels of glutamine and glutamate and their ratios in the brain microregions of interest between the control and YZG-331 groups, whereas GABA levels were elevated by 14%–21% in the thalamus, midbrain and hypothalamus (Fig. 4). Moreover, the FC in the GABA/glutamate ratio in the YZG-331 group relative to that in the control group can roughly indicate GAD activity; we noticed increased GAD activity in the hypothalamus and thalamus with an FC of 1.2 after YZG-331 administration (Fig. 4). In the histamine-related metabolic pathway, histamine in the pineal gland increased more than 10-fold in the YZG-331 group, whereas histidine was reduced by only 20% in the same region (Fig. 4); the FC in histamine/histidine ratio was approximately 18. Additionally, YZG-331 was not an agonist of histidine decarboxylase (HDC) (Supporting Information Fig. S6A). Furthermore, we observed a rapid increase in histamine levels in the rat plasma, skin, and stomach mucosa following YZG-331 administration (Fig. 3C and Supporting Information Fig. S7B). Evidence suggests that most of the elevated brain histamine is not produced from histidine, and therefore, could not rule out the peripheral origin.

Figure 4.

Mapping of the two altered metabolic pathways after drug intervention (n = 3). ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001. Gln, glutamine; Glu, glutamate; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; His, histidine; HA, histamine; 1-MethylHA, 1-methylhistamine; TH, thalamus; PG, pineal gland; HP, hypothalamus; MB, midbrain; CB, cerebellum; CTX, cortex; GS, glutamine synthetase; PAG, phosphate-activated glutaminase; GAD, glutamate decarboxylase; HDC, histidine decarboxylase; HNMT, histamine N-methyltransferase; FC, fold change.

Figure 7.

The potential targets of YZG-331. (A) YZG-331 increases GAD activity to promote GABA; (B) YZG-331 increases GABA, histamine and 1-methylhistamine levels in the rat brain; (C) YZG-331 may accelerate the inactivation of histamine via OCT3; The increased peripheral histamine permeates the pineal gland; (D) YZG-331 enhances intracellular histidine uptake and acts upon OCT3 to increase the outward transport of histamine in the periphery. Gln, glutamine; Glu, glutamate; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; His, histidine; HA, histamine; 1-methylHA, 1-methyl histamine; SA, succinic acid; TCA, tricarboxylic acid; GS, glutamine synthetase; PAG, phosphate-activated glutaminase; GAD, glutamic acid decarboxylase; HNMT, histamine N-methyltransferase; HDC, histidine decarboxylase; OCT3, organic cation transporter 3; PMAT, plasma membrane monoamine transporter; VMAT2, vesicular monoamine transporter 2; H1R, histamine H1 receptor; H2R, histamine H2 receptor; H3R, histamine H3 receptor. The histamine pathway in the brain has been illustrated according to a previous report43.

3.3. Spatially resolved isotope tracing to validate the key altered nodes

Glucose is the main carbon source of brain glutamate25. During the infusion of [U–13C]glucose, YZG-331 and the control solvents were separately injected, and the brains were collected at different time points and analyzed. The intensity–time curves of 13C-labeled GABA and glutamate derived from the [U–13C]glucose were calculated as the sum of the detected GABA (M1 to M3) (Fig. 5A) and glutamate (M1 to M5) (Supporting Information Fig. S5) and plotted for each region of interest. The ratio of isotopic GABA to isotopic glutamate could minimize inter-individual variation and indicate GAD activity. As shown in Fig. 5B, the FC in the AUC ratio of isotopic GABA/glutamate in the YZG-331 group increased by 1.2-fold in the hypothalamus relative to that in the control group, whereas the FC in other regions remained unchanged (1.0–1.1). The results of spatiotemporally resolved isotope tracing further validated that YZG-331 induced GABA production mainly in the hypothalamic region.

Figure 5.

Spatially resolved isotope tracing of GABA and histamine. (A) Intensity-time curves of isotopic GABA in the rat brain microregion after infusion with [U–13C]glucose; (B) Regional heatmaps color-coded according to FC of AUC ratio of GABA/glutamate; (C) The mapping of YZG-331, histamine, and isotopic histamine in different groups; (D) The relative intensity of YZG-331 (up), histamine (middle), isotopic histamine (down) in the pineal gland, epithalamus and hypothalamus of different groups. GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; ; CTX, cortex; TH, thalamus; HP, hypothalamus; MB, midbrain; CB, cerebellum; PG, pineal gland; D&IHA, drug and isotopic histamine group; IHA, isotopic histamine group; BK, no YZG-331 and no isotopic histamine group.

To investigate the cause of the YZG-331-induced increase in brain histamine, we established three groups that received blank solvent (BK), isotopic histamine (IHA), or isotopic histamine in combination with YZG-331 (D & IHA). As shown in Fig. 5C and D, isotopic histamine mainly entered the pineal gland, and the levels of unlabeled and isotopic histamine in the pineal gland of the combined group were higher than those of the IHA group. The results showed that peripheral histamine was distributed mainly in the pineal gland, and that YZG-331 may promote the permeation of peripheral histamine into the pineal gland.

3.4. Altered nodes from the combined spatiotemporally resolved metabolomics and isotope tracing

GABA synthase was strongly implicated in the following: after YZG-331 administration, GABA levels increased in the rat brain and screened as differential metabolites by spatially resolved metabolomics; the AUC of GABA showed its accumulation mostly in the hypothalamus by spatiotemporal analysis; FCs in both unlabeled and isotopic GABA/glutamate ratios indicated that GAD activity increased in the hypothalamus. For the histamine-related metabolic pathway, based on the rapid degradation of histamine to 1-methylhistamine observed in the spatiotemporal analysis (Fig. 3C and Fig. S3B), we suspected that the histamine transporters and catabolic enzymes are potentially altered nodes in histamine metabolism. Furthermore, results of spatial isotope tracing suggested that elevated peripheral histamine levels contributed to pineal histamine content; therefore, the factors affecting peripheral histamine were also considered.

3.5. In vitro biological validation

3.5.1. YZG-331 increased GAD enzyme activity

We used crude GAD purified from genetically engineered E. coli to assess the effect of YZG-331 on GAD. YZG-331 significantly increased the GABA yield, compared to that induced by the vehicle, by 133% and 162% at 2 and 5 mmol/L, respectively (Fig. 6H). Moreover, YZG-331 markedly increased the enzyme activity inhibited by 0.5 mmol/L SCZ, but it had no significant effect at a higher inhibitor concentration of 2 mmol/L. The in vitro test indicated that YZG-331 is an agonist of GAD.

Figure 6.

YZG-331 increases histamine release from RBL-2H3 cells and affects HNMT and GAD. (A) Histamine release in the presence of different YZG-331 concentrations; (B) Histamine release stimulated by YZG-331 at 200 μmol/L over time; (C) The relative intensity of YZG-331-induced intracellular content of histidine in the presence of the LAT1 inhibitor BCH at different concentrations; (D) Effect of OCT3 inhibitors on histamine release stimulated by YZG-331; (E) Intracellular and extracellular contents of isotopic and unlabeled histidine, histamine, and histamine release; (F) Effect of OCT3 inhibitors on isotopic and unlabeled histamine release stimulated by YZG-331; YZG-331 acting on (G) HNMT and (H) GAD. All the results are the means ± standard error of the mean from three separate experiments for RBL-2H3 cells (except the data of β-estradiol at 1 μmol/L with n = 2). ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001. HA, histamine; C, corticosterone; D, decynium 22; E, β-estradiol; SCZ, semicarbazide; YZG, YZG-331; LAT1, large neutral amino acid transporter 1; BCH, 2-amino-2-norbornanecarboxylic acid; Con, control group without inhibitor (C) or no enzyme activity (G and H).

Moreover, in vivo studies have reported that the administration of 40 mg/kg YZG-331 can increase GAD activity in mouse hypothalamic brain homogenate by 58%29. SCZ, a GAD inhibitor, can significantly antagonize the sleep prolongation effect induced by YZG-331 in mice29. Taken together, these evidences indicate that GAD is involved in the process by which YZG-331 exerts sedative and hypnotic effects.

3.5.2. YZG-331 increased histamine release upon elevated histidine uptake and via the OCT3 transporter

RBL-2H3 cells were selected for this study because they reflect the most of the functions of mucosal mast cells and basophils36, which are major histamine reservoirs in the periphery37. YZG-331 increased histamine release from RBL-2H3 cells in a dose- (Fig. 6A) and time- (Fig. 6B) dependent manner. These results prompted us to investigate the role of YZG-331 in histamine release from RBL-2H3 cells. We found that the drug substance increased the intracellular histidine uptake by 2-fold, and this uptake was dose-dependently inhibited by an LAT1 inhibitor BCH, indicating that YZG-331 can increase histidine transport into the cell by agonizing LAT1 (Fig. 6C). Additionally, we tested whether YZG-331 affects the histamine transporter OCT3. Three OCT3 inhibitors, including decynium 22, β-estradiol, and corticosterone were separately co-incubated with YZG-331, and the results showed that the increasing histamine release stimulated by YZG-331 was dose-dependently inhibited by the OCT3 inhibitors (Fig. 6D), indicating that YZG-331 is an OCT3 agonist.

Histamine is differently distributed within the basophils depending on its origin: extraneous histamine is taken up and immediately stored in the granules, while newly synthesized histamine remains preferentially in the cytosol38. OCT3 modulates intracellular histamine levels in murine basophils by controlling newly synthesized histamine38. To further investigate the mechanism of histamine release by YZG-331 in RBL-2H3 cells, isotopic histidine was added to the cell culture medium so that the detected isotopic histamine was newly synthesized, and unlabeled histamine reflects the sum of the newly synthesized histamine, pre-synthesized histamine in secretory granules and histamine transported from the extracellular space. As shown in Fig. 6E, YZG-331 significantly increased the intracellular level of isotopic histidine within the first 20 min. Meanwhile, intracellular isotopic histamine level gradually increased during the first 20 min, indicating an increase histamine synthesis owing to the increase in histidine content. Newly synthesized intracellular histamine then showed a downward trend after 20 min, indicating that histamine release was dominant during this period (Fig. 6E). Accordingly, both the extracellular and overall release of isotopic histamine showed an increasing trend after 20 min. Moreover, the release of labeled histamine by YZG-331 was strongly inhibited than that of unlabeled histamine by OCT3 inhibitors (Fig. 6F). Therefore, OCT3 acts selectively on newly synthesized histamine in RBL-2H3 cells. In addition, we noticed that YZG-331 did not stimulate the degranulation of RBL-2H3 cells (Fig. S6C).

Taken together, in RBL-2H3 cells, YZG-331 increased histidine transportation into cells via LAT1, thereby stimulating the production of newly synthesized histamine within cells. Meanwhile, as an agonist of OCT3, YZG-331 enabled OCT3 to export more newly produced histamine to the exterior.

3.5.3. Source analysis of elevated brain histamine

As shown in Fig. 4, YZG-331 induced more than 10-fold increase in histamine level in the pineal gland, where the decrease in histidine could not entirely account for histamine enhancement, indicating the introduction of peripheral histamine. Furthermore, our isotopically spatial mapping showed that peripheral isotopic histamine was concentrated primarily in the pineal gland (Fig. 5C and D). Since the pineal gland has profuse blood flow, we ruled out the influence of blood histamine by adding cardiac saline perfusion after isotopic histamine injection and found that isotopic histamine still permeated the pineal gland (Fig. S7A). Histamine is considered to poorly penetrate blood–brain barrier (BBB)39, but the pineal gland is not covered with the BBB and is one of the communication points between the blood and the brain parenchyma40. Based on the above, the highly elevated histamine level in the pineal gland was primarily owing to permeation of the elevated peripheral histamine.

3.5.4. Discussion on YZG-331 to accelerate histamine inactivation

Astrocytes are involved in histamine clearance in the CNS41, 42, 43. Human astrocytes can transport histamine via plasma membrane monoamine transporter (PMAT) and OCT3; the transported histamine is then catabolized to 1-methylhistamine by HNMT in the cytosol of astrocytes42 (Fig. 7C). Our in vitro study showed that YZG-331 had no effect on HNMT (Fig. 6G). Interestingly, the amount of histamine added to the rat brain homogenate was linearly related to the amount of 1-methylhistamine produced, indicating that 1-methylhistamine rises with histamine because of the high HNMT activity in the rat brain (Fig. S6B). In addition, OCT3 has also been implicated in the histamine clearance44,45. YZG-331 was identified as an OCT3 agonist; therefore, we inferred that YZG-331 may activate the histamine transport via OCT3 into astrocytes and thereby accelerated histamine inactivation. The above results together may explain the reasons behind increased levels of 1-methylhistamine in the brain observed by AFADESI-MSI (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Fig. S3B).

3.6. Potential targets of YZG-331

Taken together, driven by the MSI results from a strategy that consists of spatiotemporally resolved metabolomics and isotope tracing, several potential targets in GABA- and histamine-related metabolic pathways were discovered. Based on this, we envisioned how YZG-331 may be involved in metabolic pathways related to GABA and histamine, and causes their elevations in the brain (Fig. 7): It may act on GAD to produce more GABA in the hypothalamus, activate LAT1 and OCT3 transporters to transport more histamine to the periphery, and potentially help to inactivate brain histamine. Currently, drug action on GAD has been verified in vivo26; other potential targets require further validation. This study focused on discovering the potential drug targets in metabolic pathways using AFADESI-MSI as a visualization tool; elucidation of the MOA of YZG-331 and validation of the targets as well as evaluation of the contribution of different targets to drug efficacy merit further in-depth investigation. The application of the proposed strategy has provided valuable information for a more effective and deeper exploration of the MOA of YZG-331.

4. Conclusions

We proposed an MSI-based strategy that integrates spatiotemporal analysis, in situ metabolomics, and isotope imaging to discover the multiple targets of the sedative-hypnotic drug candidate YZG-331 and provide an effective way from the discovery of metabolic biomarkers to the search for metabolic pathway protein targets. The strategy can discover which metabolic nodes and pathways are altered and where they are altered after drug treatment. Using the strategy, the sedative-hypnotic drug candidate YZG-331 was found to primarily accumulate in the pineal gland and enter brain parenchyma in a relatively small amount. The results suggested that YZG-331 increased GAD activity to produce more GABA in the hypothalamus, and agonized LAT1 and OCT3 to export extracellular histamine in the periphery. The proposed strategy can help understand the MOA of CNS drugs and provide visualization tools and new perspectives for their efficacy and safety.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21927808 and No.81974500), and Chinese Academy of Medical Science (CAMS) Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS, No. 2022-I2M-2-002 and 2021-1-I2M-028, China).

Author contributions

Jiuming He and Zeper Abliz designed the research and supervised all of the research work; Bo Jin and Xuechao Pang planned and carried out the experiments and analyzed the data. Qingce Zang helped with the AFADESI-MSI experiments, Man Ga helped with the animal experiments, Jing Xu helped with the UPLC-MS/MS experiments. Zhigang Luo and Ruiping Zhang gave effective ideas on the experiment design. Jiangong Shi and Zeper Abliz applied for research grants. Bo Jin drafted the manuscript, Jiuming He and Zeper Abliz revised the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2022.11.011.

Contributor Information

Jiuming He, Email: hejiuming@imm.ac.cn.

Zeper Abliz, Email: zeper@imm.ac.cn, zeper@muc.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Danon J.J., Reekie T.A., Kassiou M. Challenges and opportunities in central nervous system drug discovery. Trends Chem. 2019;1:612–624. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gribkoff V.K., Kaczmarek L.K. The need for new approaches in CNS drug discovery: why drugs have failed, and what can be done to improve outcomes. Neuropharmacology. 2017;120:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hutchinson L., Kirk R. High drug attrition rates―where are we going wrong? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:189–190. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hutson P.H., Clark J.A., Cross A.J. CNS target identification and validation: avoiding the valley of death or naive optimism? Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017;57:171–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010716-104624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ban T.A. The role of serendipity in drug discovery. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8:335–344. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2006.8.3/tban. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng W., Thorne N., McKew J.C. Phenotypic screens as a renewed approach for drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2013;18:1067–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howes O.D., Mehta M.A. Challenges in CNS drug development and the role of imaging. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2021;238:1229–1230. doi: 10.1007/s00213-021-05838-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong D.F., Tauscher J., Grunder G. The role of imaging in proof of concept for CNS drug discovery and development. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:187–203. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piel M., Vernaleken I., Rosch F. Positron emission tomography in CNS drug discovery and drug monitoring. J Med Chem. 2014;57:9232–9258. doi: 10.1021/jm5001858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egerton A. The potential of 1H-MRS in CNS drug development. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2021;238:1241–1254. doi: 10.1007/s00213-019-05344-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pang X., Gao S., Ga M., Zhang J., Luo Z., Chen Y., et al. Mapping metabolic networks in the brain by ambient mass spectrometry imaging and metabolomics. Anal Chem. 2021;93:6746–6754. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.1c00467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He J., Sun C., Li T., Luo Z., Huang L., Song X., et al. A sensitive and wide coverage ambient mass spectrometry imaging method for functional metabolites based molecular histology. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2018;5 doi: 10.1002/advs.201800250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shariatgorji M., Nilsson A., Fridjonsdottir E., Vallianatou T., Kallback P., Katan L., et al. Comprehensive mapping of neurotransmitter networks by MALDI-MS imaging. Nat Methods. 2019;16:1021–1028. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0551-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fridjonsdottir E., Shariatgorji R., Nilsson A., Vallianatou T., Odell L.R., Schembri L.S., et al. Mass spectrometry imaging identifies abnormally elevated brain l-DOPA levels and extrastriatal monoaminergic dysregulation in l-DOPA-induced dyskinesia. Sci Adv. 2021;7 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abe5948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu D., Huang J., Gao S., Jin H., He J. A temporo-spatial pharmacometabolomics method to characterize pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in the brain microregions by using ambient mass spectrometry imaging. Acta Pharma Sin B. 2022;12:3341–3353. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2022.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vallianatou T., Shariatgorji M., Nilsson A., Fridjonsdottir E., Kallback P., Schintu N., et al. Molecular imaging identifies age-related attenuation of acetylcholine in retrosplenial cortex in response to acetylcholinesterase inhibition. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44:2091–2098. doi: 10.1038/s41386-019-0397-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vallianatou T., Strittmatter N., Nilsson A., Shariatgorji M., Hamm G., Pereira M., et al. A mass spectrometry imaging approach for investigating how drug‒drug interactions influence drug blood‒brain barrier permeability. Neuroimage. 2018;172:808–816. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugiyama E., Guerrini M.M., Honda K., Hattori Y., Abe M., Kallback P., et al. Detection of a high-turnover serotonin circuit in the mouse brain using mass spectrometry imaging. iScience. 2019;20:359–372. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2019.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kadar H., Le Douaron G., Amar M., Ferrié L., Figadère B., Touboul D., et al. MALDI mass spectrometry imaging of 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) in mouse brain. Neurotox Res. 2014;25:135–145. doi: 10.1007/s12640-013-9449-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swales J.G., Tucker J.W., Spreadborough M.J., Iverson S.L., Clench M.R., Webborn P.J., et al. Mapping drug distribution in brain tissue using liquid extraction surface analysis mass spectrometry imaging. Anal Chem. 2015;87:10146–10152. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b02998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nilsson A., Goodwin R.J., Shariatgorji M., Vallianatou T., Webborn P.J., Andrén P.E. Mass spectrometry imaging in drug development. Anal Chem. 2015;87:1437–1455. doi: 10.1021/ac504734s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He J., Luo Z., Huang L., He J., Chen Y., Rong X., et al. Ambient mass spectrometry imaging metabolomics method provides novel insights into the action mechanism of drug candidates. Anal Chem. 2015;87:5372–5379. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo Z., Liu D., Pang X., Yang W., He J., Zhang R., et al. Whole-body spatially-resolved metabolomics method for profiling the metabolic differences of epimer drug candidates using ambient mass spectrometry imaging. Talanta. 2019;202:198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2019.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mellinger A.L., Muddiman D.C., Gamcsik M.P. Highlighting functional mass spectrometry imaging methods in bioanalysis. J Proteome Res. 2022;21:1800–1807. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.2c00220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L., Xing X., Zeng X., Jackson S.R., TeSlaa T., Al-Dalahmah O., et al. Spatially resolved isotope tracing reveals tissue metabolic activity. Nat Methods. 2022;19:223–230. doi: 10.1038/s41592-021-01378-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang B., Yu Y., Yu F., Fang J., Wang G., Jiang J., et al. The mechanism study of YZG-331 on sedative and hypnotic effects. Behav Brain Res. 2022;428 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2022.113885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X., Jiang J., Jin X., Liu Y., Xu C., Zhang J., et al. Simultaneous determination of YZG-331 and its metabolites in monkey blood by liquid chromatography‒tandem mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2021;193 doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2020.113720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jia S.B. Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College; Beijing: 2012. Hypnotic effects and mechanism of novel modifiers of N6-(4-hydroxybenzyl) adenosine riboside: YZG-330 and YZG-331. [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang W.Q. Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College; Beijing: 2018. Hypnotic effects and mechanisms of novel modifiers of N6-(4-hydroxybenzyl) adenosine riboside: YZG-331. [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun C., Li T., Song X., Huang L., Zang Q., Xu J., et al. Spatially resolved metabolomics to discover tumor-associated metabolic alterations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:52–57. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1808950116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He J., Huang L., Tian R., Li T., Sun C., Song X., et al. MassImager: a software for interactive and in-depth analysis of mass spectrometry imaging data. Anal Chim Acta. 2018;1015:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2018.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bynoe M.S., Viret C., Yan A., Kim D.G. Adenosine receptor signaling: a key to opening the blood‒brain door. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2015;12:20. doi: 10.1186/s12987-015-0017-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duarte J.M., Gruetter R. Glutamatergic and GABAergic energy metabolism measured in the rat brain by 13C NMR spectroscopy at 14.1 T. J Neurochem. 2013;126:579–590. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patel A.B., de Graaf R.A., Mason G.F., Rothman D.L., Shulman R.G., Behar K.L. The contribution of GABA to glutamate/glutamine cycling and energy metabolism in the rat cortex in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:5588–5593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501703102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Behar K.L. In: Encyclopedia of neuroscience. Larry R.S., editor. Academic Press; Cambridge: 2009. GABA synthesis and metabolism; pp. 433–439. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Passante E., Frankish N. The RBL-2H3 cell line: its provenance and suitability as a model for the mast cell. Inflamm Res. 2009;58:737–745. doi: 10.1007/s00011-009-0074-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borriello F., Iannone R., Marone G. Histamine release from mast cells and basophils. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2017;241:121–139. doi: 10.1007/164_2017_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schneider E., Machavoine F., Pleau J.M., Bertron A.F., Thurmond R.L., Ohtsu H., et al. Organic cation transporter 3 modulates murine basophil functions by controlling intracellular histamine levels. J Exp Med. 2005;202:387–393. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pardridge W.M., Oldendorf W.H., Cancilla P., Frank H.J. Blood‒brain barrier: interface between internal medicine and the brain. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:82–95. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-105-1-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verheggen I.C.M., de Jong JJA, van Boxtel MPJ, Postma A.A., Verhey F.R.J., Jansen J.F.A., et al. Permeability of the windows of the brain: feasibility of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI of the circumventricular organs. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2020;17:66. doi: 10.1186/s12987-020-00228-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huszti Z. Histamine uptake into non-neuronal brain cells. Inflamm Res. 2003;52(Suppl 1):S03–S06. doi: 10.1007/s000110300028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshikawa T., Naganuma F., Iida T., Nakamura T., Harada R., Mohsen A.S., et al. Molecular mechanism of histamine clearance by primary human astrocytes. Glia. 2013;61:905–916. doi: 10.1002/glia.22484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshikawa T., Nakamura T., Yanai K. Histamine N-methyltransferase in the brain. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20 doi: 10.3390/ijms20030737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu P., Hata R., Ogasawara M., Cao F., Kameda K., Yamauchi K., et al. Targeted disruption of organic cation transporter 3 (Oct 3) ameliorates ischemic brain damage through modulating histamine and regulatory T cells. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1897–1908. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ogasawara M., Yamauchi K., Satoh Y., Yamaji R., Inui K., Jonker J.W., et al. Recent advances in molecular pharmacology of the histamine systems: organic cation transporters as a histamine transporter and histamine metabolism. J Pharmacol Sci. 2006;101:24–30. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fmj06001x6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.