Pododermatitis is defined as inflammation of the pedal skin, including interdigital spaces, footpads, nail folds (paronychia), nails, or a combination thereof (1). Canine pododermatitis is a very common presentation in veterinary practice (2). Various descriptors have been used for canine pododermatitis and related lesions that develop from acute and chronic inflammatory changes. Such descriptors include pedal folliculitis and furunculosis, interdigital cysts, interdigital furunculosis, inflammatory interdigital nodules, and interdigital pyoderma (3–6). As pododermatitis in dogs is often complex and multifactorial, these terms may be used interchangeably, especially in the presence of pedal lesions, including (but not limited to) nodules, comedones, hyperplasia, and draining tracts.

Although pododermatitis may be easily identified based on its definition of inflamed or diseased pedal structures, it can be a frustrating condition to treat and manage (1,7). This is due partly to the long list of possible primary diseases that can cause pododermatitis (Table 1); and partly to a range of additional factors that complicate and contribute to the persistence, recurrence, and waxing and waning of symptoms and the associated patient discomfort. Pedal lesions and discomfort may improve spontaneously or in response to treatment, or may persist indefinitely despite therapy.

Table 1.

Primary conditions and other factors affecting canine pododermatitis.

| Examples | |

|---|---|

| Primary causes | |

| Allergic disease | Canine atopic dermatitis, cutaneous adverse food reaction, contact hypersensitivity |

| Foreign body | Endogenous (hair, keratin) or exogenous (sharp objects; vegetation including grass awns, splinters) |

| Endocrine disease | Hypothyroidism, hyperadrenocorticism |

| Parasites | Demodex, hookworm |

| Bacterial and fungal infections | Mycobacteria, dermatophytosis, blastomycosis, fungal mycetoma, sporotrichosis |

| Viral and protozoal infections | Canine papillomatosis, leishmaniasis, canine distemper |

| Autoimmune and immune-mediated diseases | Pemphigus foliaceus; erythema multiforme; cutaneous vasculitis (drugs, vaccines, infection); symmetric lupoid onychodystrophy; systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Neoplasia | Squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, mast cell tumor, keratoacanthoma, inverted papilloma |

| Other | Trauma; musculoskeletal disease (arthritis, soft tissue injury); idiopathic sterile granuloma; immunomodulatory-responsive pododermatitis; footpad hyperkeratosis; superficial necrolytic dermatitis |

| Predisposing factors | |

| Hair coat | Short hair coat, matted hair |

| Body weight | Obesity, large-breed dogs |

| Altered weight-bearing | Body conformation, osteoarthritis, limb deformity, cruciate disease |

| Perpetuating factors | |

| Chronic lesion formation and pedal inflammation | Hyperkeratosis, lichenification, fibrosis, scarring, pseudopad formation, deep tissue pockets, ingrown hairs, sinus tracts |

| Persistent infection | Superficial or deep, including bacterial, fungal, mixed |

| Secondary factors | |

| Bacterial infection | Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, E. coli, Pseudomonas, Corynebacterium, Enterococcus, other |

| Fungal infection | Malassezia |

Similarities with canine otitis externa

Canine pododermatitis has many similarities with canine otitis externa (Table 2); both are clinical presentations rather than diagnoses, and they are often seen together. As with otitis externa (8–10), it is vital that each pododermatitis case be evaluated as a multifactorial condition. Many underlying diseases can lead to similar overlapping pedal symptoms, especially in chronic cases. Also, the same disease may present with entirely different pedal clinical signs in 2 separate patients (8–10). A thorough diagnostic workup, including search for the primary cause and presence of predisposing, perpetuating, and secondary factors will help select treatment options and appropriate management needs in the pododermatitis patient (1,2,11,12).

Table 2.

Similarities between otitis and pododermatitis in dogs.

| Similar features |

|---|

| Not a disease — rather, a clinical presentation |

| Common presentation in general practice and referral dermatology practice |

| Underlying primary condition is present |

| Allergic disease is a common primary cause |

| May or may not be accompanied by other dermatologic symptoms |

| May or may not be accompanied by systemic clinical symptoms |

| Not every patient with predisposing factors is affected in the absence of primary disease |

| Symptoms/visual lesions at the affected site may or may not indicate primary disease |

| Inflammation and discomfort (including pruritus) are common |

| Secondary infection is common |

| Inflammation alone does not indicate infection |

| Cytological testing helps confirm or rule out secondary infection (except in deeper infection or with presence of chronic changes) |

| Secondary infection(s) complicate treatment and clinical picture |

| Affects patient quality of life |

| Frustrating condition for pet owners |

| Frustrating condition for veterinarians |

| Potential for chronicity, leading to further complications |

| Chronic changes complicate treatment and clinical picture |

| Ongoing maintenance therapy to control secondary and perpetuating factors may be required |

| Perpetuating factors may prevent symptom resolution even with primary disease controlled |

| Secondary unresolved infection may act as a perpetuating factor |

Various classifications have been used to help categorize canine otitis externa, including the PSPP system (primary and secondary causes, predisposing and perpetuating factors), which can help diagnose and treat canine otitis externa while also serving as a useful educational and prognostic tool (10). A similar approach can be used for pododermatitis due to similarities between the 2 conditions. If all or most of the factors involved are identified, then resolution of current paw disease and prevention of future pododermatitis episodes are likely.

Classification of causes and factors involved in canine pododermatitis

A. Primary causes

These create the initial, direct pedal inflammation or cutaneous change. Primary causes may be very subtle initially but can lead to chronic pododermatitis and pedal changes. At least 1 primary cause and 1 or more other factors are expected in each presenting pododermatitis case (1,2,11,12). However, some animals may be affected by more than 1 primary disease. Canine atopic dermatitis, demodicosis, and pedal trauma are some of the more common primary conditions affecting pedal skin.

B. Predisposing factors

These alter the local pedal skin environment and increase the risk of developing pododermatitis. These factors usually do not cause pedal disease themselves; however, they cause clinical disease by working in conjunction with primary, secondary, or perpetuating factors. Successful management of pododermatitis requires that predisposing factors be identified and corrected where possible (2,10,12).

C. Perpetuating factors

These do not initiate inflammation but lead to exacerbation of the inflammatory process and prevent resolution of pododermatitis. Perpetuating factors are not uncommon in canine pododermatitis and include pedal scarring, furunculosis, and ingrown hair; changes in conformation and weight bearing; and persistent infection. They may be subtle at first but, with chronicity, can develop into the most severe component of pododermatitis. Once present, they accentuate pedal inflammation and related complications (12). As they can become the driving force behind recurring or persistent discomfort or pedal lesions, perpetuating factors can lead to frustration for veterinarians and pet owners due to repeated veterinary visits, financial burden of care, patient discomfort, patient non-compliance, and persistence or progressive worsening of the disease (7,12). Perpetuating factors can maintain paw disease and lead to apparent treatment failure even if the primary cause has been identified and corrected.

D. Secondary factors

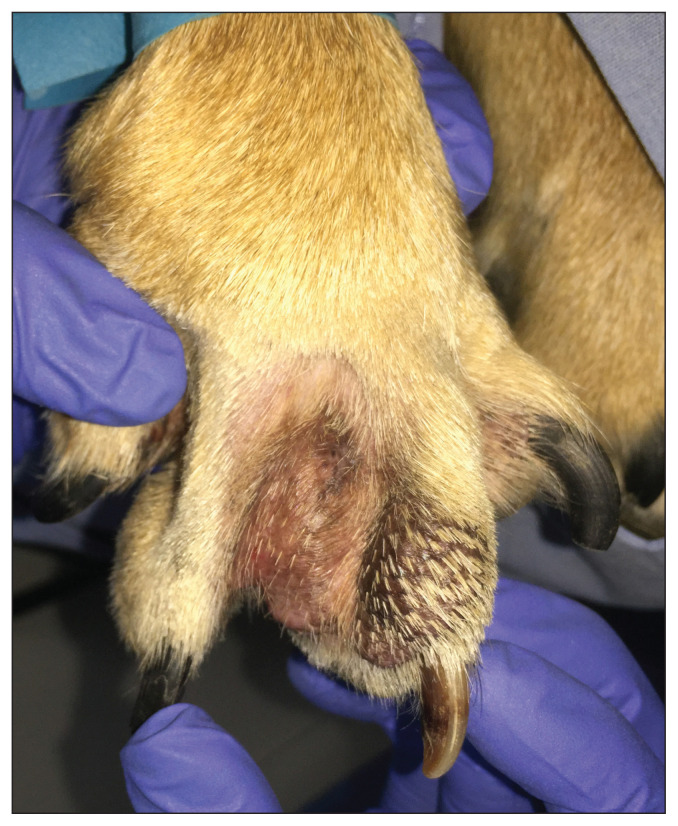

These include secondary bacterial or fungal infections due to an altered microenvironment and inflammation in the paws. Secondary infection may be superficial, deep, or a combination. There can be multiple infections at different depths within the pedal skin, especially with chronicity. When multiple paws are affected, each paw may be affected by a different infection, including a mix of multiple bacterial or fungal organisms. Drug-resistant organisms are not uncommon in chronic skin infection (Figure 1), or in infections where multiple antibiotic courses have been administered (7,13). Unresolved or persistent secondary infection can also act as a perpetuating factor.

Figure 1.

Chronic pododermatitis in a dog due to partially managed pemphigus foliaceus and persistent secondary drug-resistant pyoderma.

Photograph supplied by Dr. Jangi Bajwa.

Diagnostic testing and patient management

A thorough patient history, a detailed physical examination, and basic dermatologic tests such as deep skin scrapings, hair plucks, and cutaneous cytology form the baseline workup for canine pododermatitis (1,14). Based on the nature of the pedal lesions, cytological examination may be conducted using surface samples or by sampling exudative or draining lesions. Direct impression cytology provides information regarding the presence or absence of inflammatory cells, phagocytosed bacteria, and fungal infections (2,11). Fine needle aspiration-based cytology testing from nodules can be helpful in diagnosing conditions such as primary neoplasia; however, it may be of minimal value in other conditions such as chronic infected nodular lesions and sterile interdigital cystic lesions. Skin scrapings and hair plucks are useful for assessing parasitic pododermatitis (14).

Once pedal pyoderma is confirmed, bacterial culture and sensitivity testing can guide systemic antibiotic selection. Superficial secondary pyoderma can be effectively treated using topical antimicrobial therapy (15). However, surface swab samples may not be representative of the bacterial involvement in deeper pedal tissue. When lesions consistent with deep pyoderma, such as nodules and draining tracts, are present, tissue culture sampling under general anesthesia is preferred over superficial skin swabs. The appropriate length of culture-based systemic antibiotic therapy is indicated for deep pyoderma (7).

Histopathology can be helpful in diagnosing the primary disease, as well as for identifying some perpetuating and secondary factors. Histopathology is useful in confirming or ruling out conditions such as exogenous and endogenous foreign bodies (e.g., grass awns, free hair shafts); deep infection; parasites; autoimmune disease; and neoplasia (Figure 2) (1,7). When biopsy sampling is done, bacterial and fungal culture testing from pedal tissue should be strongly considered in combination (1). It is not uncommon for multiple bacteria to be isolated from deep pedal pyoderma lesions. When multiple paws are affected, separate culture and sensitivity tests from individual paws should be considered, as sampling from a single paw may be not representative of the infection in all affected paws.

Figure 2.

Fibroadnexal hamartoma in the interdigital space of a dog, non-responsive to various empirical drug trials. Resolution was achieved after CO2 laser removal of the interdigital mass.

Photograph supplied by Dr. Jangi Bajwa.

Pruritus and pain should be assessed in canine pododermatitis, and appropriate treatments instituted for the dog’s comfort. Pruritus is a common symptom associated with pododermatitis and may be either related to the primary disease or due to secondary infection (12). Pruritus may also be present with non-pruritic primary conditions such as demodicosis or autoimmune skin disease. In such conditions, pruritus is usually solely related to secondary infection. Similarly, pedal pain, lameness, and systemic signs such as lethargy may be produced by the primary cause, secondary infection, or a combination. Perpetuating factors may also contribute to pain, pruritus, and other systemic symptoms.

A discussion on the treatment of pododermatitis is beyond the scope of this review; however, many good resources are available (2–7,12,14,15). Due to the multifactorial nature of the condition, various treatment modalities may need to be combined, including systemic drug therapy, topical therapy, CO2 laser surgery, cold steel surgery, photobiomodulation therapy, lifestyle changes, pain management, pruritus control, immunosuppressive therapy, and immunomodulatory therapy. Treatment options for pododermatitis vary for each animal and are best selected based on identification of the animal’s individual primary disease(s), secondary infection(s), and predisposing and perpetuating factors. Importantly, an individual’s treatment needs may change over time due to factors such as general health changes, control of primary and pedal disease, lifestyle or life stage changes, body condition scores, seasonality of symptoms, and tolerance of drug therapy. These changes may lead to recurrence of pododermatitis, indicating the need to review the treatment and management plan.

In summary, when presented with a pododermatitis patient, obtaining a primary disease diagnosis while also correcting predisposing, perpetuating, and secondary factors is preferable to simply treating the presenting clinical signs (12). Follow-up assessments are vital in both acute and chronic cases. Follow-up assessments and monitoring-based individualized treatment plan updates in chronic cases will usually help ensure long-term comfort and disease management.

Footnotes

The Veterinary Dermatology column is a collaboration of The Canadian Veterinary Journal and the Canadian Academy of Veterinary Dermatology (CAVD). CAVD is a not-for-profit organization, with a mission to advance the science and practice of veterinary dermatology in Canada, in order to help animals suffering from skin and ear disease to live the lives they are meant to. CAVD invites everyone with a professional interest in dermatology to join (www.cavd.ca). Annual membership fee is $50. Student membership fees are generously paid by Royal Canin Canada.

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Bajwa J. Canine pododermatitis. Can Vet J. 2016;57:991–993. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nuttall T. How I approach chronic pododermatitis. 42nd World Small Animal Veterinary Association Congress; September 25–28, 2017; Copenhagen, Denmark. [Last accessed March 14, 2023]. Conference Proceedings available from: https://www.vin.com/apputil/content/defaultadv1.aspx?id=8506459&pid=20539&. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duclos DD. Canine pododermatitis. Vet Clin Small Anim Pract. 2013;43:57–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marchegiani A, Fruganti A, Gavazza A, Spaterna A, Cerquetella M. Fluorescence biomodulation for canine interdigital furunculosis: Updates for once-weekly schedule. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:880349. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.880349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marchegiani A, Spaterna A, Cerquetella M, Tambella AM, Fruganti A, Paterson S. Fluorescence biomodulation in the management of canine interdigital pyoderma cases: A prospective, single-blinded, randomized and controlled clinical study. Vet Dermatol. 2019;30:371–e109. doi: 10.1111/vde.12785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frey R, Varjonen K. A retrospective case series of the postoperative outcome for 30 dogs with inflammatory interdigital nodules surgically treated with carbon dioxide laser and a nonantimicrobial wound-healing protocol. Vet Dermatol. 2023;34:150–155. doi: 10.1111/vde.13146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller WH, Griffin CE, Campbell KL. Muller and Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology. 7th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2013. pp. 184–222. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bajwa J. Canine otitis externa — Treatment and complications. Can Vet J. 2019;60:97–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saridomichelakis MN, Farmaki R, Leontides LS, Koutinas AF. Aetiology of canine otitis externa: A retrospective study of 100 cases. Vet Dermatol. 2007;18:341–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.2007.00619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller WH, Griffin CE, Campbell KL. Muller and Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology. 7th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2013. pp. 741–753. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nuttall T. Chronic pododermatitis and interdigital furunculosis in dogs. Companion Anim. 2019;24:194–200. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marsella R. How to treat canine pododermatitis. Vet Focus. 2020. [Last accessed March 14, 2023]. p. 28. Available from: https://vetfocus.royalcanin.com/en/scientific/how-to-treat-canine-pododermatitis.

- 13.Hillier A, Lloyd DH, Weese JS, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and antimicrobial therapy of canine superficial bacterial folliculitis (Antimicrobial Guidelines Working Group of the International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases) Vet Dermatol. 2014;25:163–175. doi: 10.1111/vde.12118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saridomichelakis MN, Koutinas AF, Farmaki R, Leontides LS, Kasabalis D. Relative sensitivity of hair pluckings and exudate microscopy for the diagnosis of canine demodicosis. Vet Dermatol. 2007;18:138–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.2007.00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frosini SM, Loeffler A. Treating canine pyoderma with topical antibacterial therapy. In Pract. 2020;42:323–330. [Google Scholar]