Abstract

The alternate RNA polymerase sigma factor gene, sigF, which is expressed in stationary phase and under stress conditions in vitro, has been deleted in the virulent CDC1551 strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The growth rate of the ΔsigF mutant was identical to that of the isogenic wild-type strain in exponential phase, although in stationary phase the mutant achieved a higher density than the wild type. The mutant showed increased susceptibility to rifampin and rifapentine. Additionally, the ΔsigF mutant displayed diminished uptake of chenodeoxycholate, and this effect was reversed by complementation with a wild-type sigF gene. No differences in short-term intracellular growth between mutant and wild-type organisms within human monocytes were observed. Similarly, the organisms did not differ in their susceptibilities to lymphocyte-mediated inhibition of intracellular growth. However, mice infected with the ΔsigF mutant showed a median time to death of 246 days compared with 161 days for wild-type strain-infected animals (P < 0.001). These data indicate that M. tuberculosis sigF is a nonessential alternate sigma factor both in axenic culture and for survival in macrophages in vitro. While the ΔsigF mutant produces a lethal infection of mice, it is less virulent than its wild-type counterpart by time-to-death analysis.

Tuberculosis is currently the seventh leading cause of disability and death globally and is expected to remain among the top seven causes until the year 2020 if current tools and patterns of control prevail (26). Successful treatment of cases requires multidrug therapy for a minimum of 4 to 6 months. The operational difficulties of ensuring uninterrupted drug therapy have led to the development of drug-resistant forms of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in many parts of the world, the spread of which poses a growing health threat to all nations, even those with good tuberculosis control programs (27).

Control of M. tuberculosis infection is made more difficult by the complex long-term nature of the host-pathogen interactions in tuberculosis. Initial infection is followed by bacterial multiplication within mononuclear phagocytes, release of intracellular organisms, and dissemination (5). Most often, the subsequent development of specific immunity serves to contain but not eradicate the organism, resulting in the persistence of latent foci of bacteria. Reactivation disease can therefore occur years after initial exposure (21, 34). Bacterial regulatory genes may play an important role in the ability of tubercle bacilli to adapt and survive during these different stages of infection and disease.

RNA polymerase alternate sigma factors are used by bacteria for conditional gene expression depending on the ambient environmental milieu (12, 25), and they have been shown to mediate in vivo-triggered responses necessary for conditional expression of virulence factors in diverse bacterial species (8, 10) including M. tuberculosis (4). The recently completed determination of the genomic sequences of M. tuberculosis identified a total of 13 sigma factors (3, 14): 2 principal-like sigmas known as SigA and SigB (4, 9, 15), 10 extracytoplasmic sigmas (11, 38), and one stress/sporulation-type sigma known as SigF (7). The M. tuberculosis sigF gene is upregulated by exogenous stress conditions (e.g., by the administration of antimycobacterial drugs [24], by entry into stationary phase in vitro [7, 24], and during macrophage infection [16]. Its gene product is structurally related to sigma factor from Streptomyces coelicolor (30), Bacillus subtilis (6, 17), Staphylococcus aureus (39), and Listeria monocytogenes (1, 37), which are also induced by entry into stationary phase or stress. In this report we describe the inactivation of the M. tuberculosis sigF gene by allelic exchange and we present a characterization of the phenotype of the ΔsigF mutant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Allelic exchange inactivation of the sigF gene.

A 2.8-kb BamHI fragment containing sigF was used to construct the allelic replacement vector pPC47. Assembly of pPC47 was accomplished by removal of a 723-bp intragenic fragment of sigF by NruI and BstXI digestion and blunt-end insertion of a 1.7-kb cassette carrying the Streptomyces hygroscopicus hyg gene from p16R1 (13). The resulting 3.7-kb BamHI fragment, which contained 1.2 kb of sigF left-flanking DNA and 1.0 kb of sigF right-flanking sequences around a central hyg gene, was excised and blunt end cloned into pJG1001, which is a mycobacterial suicide vector encoding kanamycin resistance (Kmr; encoded by the aph gene) and sucrose sensitivity (Sucs; encoded by the sacB gene), to yield pPC47, a plasmid which contains a unique BamHI site adjacent to the inserted 3.7-kb fragment. Five micrograms of pPC47 was introduced into freshly prepared electrocompetent M. tuberculosis strain CDC1551 using standard methodologies (19, 29). After incubation for 7 weeks, nine hygromycin-resistant colonies were identified: one (the putative sigF knockout) was Kms Sucr, three were Kmr Sucs (putative merodiploid intermediates), and the remaining five were shown by subsequent Southern blotting to have random hyg gene insertions, some with gene rearrangements in the sigF locus. A subsequent effort to inactivate the sigF gene in the H37Rv strain of M. tuberculosis was also successful, with similar frequencies of recombinants. Southern blot analysis was used to confirm the chromosomal structure of candidate knockout strains. Later, PCR analysis of chromosomal DNA or a subcloned Hyr-conferring fragment from the putative ΔsigF mutant using primers directed outward from the hyg gene and inward from the left and right sigF flanking DNA gave the appropriately sized fragments. DNA sequencing of the junctions of the hyg gene and mycobacterial DNA using PCR products or the subcloned Hyr-conferring fragment confirmed the replacement of sigF by hyg.

Complementation of the M. tuberculosis ΔsigF mutant.

pPC51 contains the 2.8-kb sigF operon-containing BamHI fragment from pYZ99 (7) cloned into the XbaI site of pMH94 (20) to yield an integrative, single-copy complementing plasmid that confers Kmr. pPC51 was introduced into the M. tuberculosis ΔsigF mutant by electroporation and kanamycin selection.

In vitro phenotypic analysis.

In vitro growth rates of M. tuberculosis CDC1551 (wild type) and the isogenic ΔsigF mutant were determined in agitated cultures at 37°C in Middlebrook 7H9 broth with 5% glycerol, 10% albumin dextrose complex (ADC), and 0.025% Tween 80 (19). Each 100-ml culture was started by inoculation with 1 ml of a stationary-phase (>3-week) culture. Aliquots were sampled every 1 to 2 days, and the bacterial density was determined by plate counts. Assays of the uptake of [14C]chenodeoxycholate were performed with washed, concentrated log-phase bacteria exposed to 1.25 μCi of [14C]chenodeoxycholate for up to 50 min at 37°C (40). Assays were halted by the addition of excess buffer, and uptake was assessed by filtration. Uptake at each time point was normalized to the dry mass of cells determined by pre- and postweighing each filter. The S. aureus sigB mutant PC400 and its isogenic wild-type strain, 8325-4, were generous gifts from Simon Foster (2).

M. tuberculosis infection of human monocytic cells.

Ficoll-Hypaque-purified peripheral blood monocytes (105) from four unrelated, healthy, tuberculin-positive human volunteers were prepared (32) and plated in 96-well microtiter plates. The following day, M. tuberculosis strains were allowed to infect monocyte monolayers for 1 h in the presence of 30% autologous serum with a multiplicity of infection of 1:1; uningested mycobacteria were removed by aspiration and three washes. For selected samples autologous, peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) prepared as previously described (32) were added after removal of mycobacteria in a 10:1 PBL/monocyte ratio. The intracellular infection was allowed to progress in complete Iscove's modified Dulbecco medium with NaHCO3, 25 mM HEPES, 1% l-glutamine, and 10% noninactivated autologous serum. At 0, 1, 4, and 8 days after infection, the human cells were lysed with 0.067% sodium dodecyl sulfate in Middlebrook 7H9-ADC, and surviving CFU of intracellular mycobacteria were determined by plating.

Mouse time-to-death study.

Groups of BALB/c mice (6 to 8 weeks old; female; Harlan Sprague-Dawley) were infected with 0.1-ml volumes containing dispersed preparations of M. tuberculosis by intravenous tail vein injection. The inoculum was 106.02 CFU for wild-type M. tuberculosis and 105.97 CFU for the M. tuberculosis ΔsigF mutant. The animals were weighed twice weekly and monitored on a long-term basis. Moribund animals were sacrificed.

RESULTS

Construction of an M. tuberculosis ΔsigF mutant.

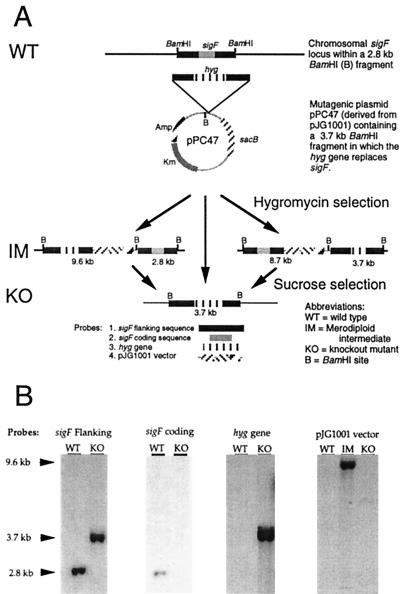

Using a virulent, recently isolated human outbreak strain of M. tuberculosis known as CDC1551 (35), we replaced the sigF gene with a hygromycin resistance gene using allelic exchange with sacB counterselection as illustrated in Fig. 1A (28). Phenotypically, the putative M. tuberculosis ΔsigF clone was resistant to hygromycin and sensitive to kanamycin, while merodiploid intermediate strains were resistant to both markers. These antibiotic resistance phenotypes confirmed that the desired second recombination event leading to loss of vector sequences had occurred. Analysis of the ΔsigF mutant, wild-type, and merodiploid intermediate strains by Southern blotting using probes specific for the sigF-flanking sequences, sigF-coding sequences, the hygromycin gene cassette, and the plasmid backbone revealed the anticipated hybridization patterns (Fig. 1B). Since the initial construction of the allelic exchange vector pPC47 included a deletion of 723 bp of the sigF coding sequence and since Southern blotting experiments with the 723-bp segment as a probe revealed its absence in the deletion strain, this sigF deletion/replacement mutation is nonrevertible to the wild type. As sigF (Rv3286c) is the distal member of a multigene operon, its interruption would not be expected to have polar effects on other genes in the operon. A single-copy, integrative plasmid (pPC51) harboring the entire sigF operon and upstream elements was introduced in the M. tuberculosis ΔsigF mutant to yield a complemented strain.

FIG. 1.

(A) Cartoon representation of the strategy used to interrupt the sigF gene using pPC47. The location and spacing of BamHI sites are shown. (B) BamHI-restricted chromosomal DNA from the recombinant M. tuberculosis strains was analyzed by Southern blotting using the four probes shown in panel A. The sizes of the hybridizing bands are indicated at the left margin.

In vitro phenotypes.

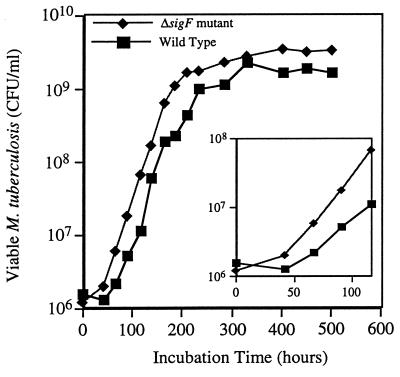

We studied the M. tuberculosis ΔsigF mutant for in vitro phenotypes which might differentiate it from the wild type. Comparisons of the growth characteristics of the sigF knockout mutant versus wild-type CDC1551 revealed that their exponential growth rates in rich medium were the same (Fig. 2). However, the mutant grew to a threefold-higher density in stationary phase than did the wild type in standard Middlebrook broth as assessed by both CFU assay and by optical density measurements. Also, when passed from a dense culture into fresh medium the mutant began regrowth more quickly than the wild type and did not exhibit the usual lag phase (Fig. 2, inset).

FIG. 2.

In vitro growth rates of M. tuberculosis CDC1551 (wild type) and the isogenic ΔsigF mutant agitated at 37°C in Middlebrook 7H9 broth supplemented with glycerol, 10% ADC, and Tween 80 (19). Each 100-ml culture was started by inoculation with 1 ml of a declumped suspension from freshly grown colonies. (Main panel) Results of a 22-day growth curve in which aliquots were sampled every 1 to 2 days and the bacterial density was determined by plate counts; (inset) display of the same data for the first 5 days plotted on an expanded scale to show differences in the lag phase between the strains. This experiment was performed twice by both plating dilutions and optical density determinations, each producing similar results in lag and stationary phases.

Using a sensitive CFU assay as our end point, we did not find significant in vitro survival differences between the ΔsigF mutant and wild-type M. tuberculosis in response to the following conditions: heat stress, cold stress, microaerophilic stress, and long-term stationary-phase growth. However, we did observe differences between the drug susceptibility profile of the M. tuberculosis ΔsigF mutant and that of the wild type. As shown in Table 1, the mutant showed increased susceptibility to rifamycin drugs including rifampin (eightfold). The rifampin hypersusceptibility was partially reversed in the complemented strain. Control experiments using M. tuberculosis transformed with a plasmid conferring hygromycin resistance did not reveal a change in rifampin susceptibility. Also, an S. aureus sigB mutant (PC400), which lacks a homologous sigma factor, showed no change in rifampin MIC compared with an isogenic wild-type strain (8325-4), suggesting that the rifampin hypersusceptibility phenomenon is not generalizable to loss of sigma factors of this class across species.

TABLE 1.

Antibiotic susceptibilities of wild-type M. tuberculosis, the ΔsigF mutant, and the complemented mutant

| Drug | MIC (μg/ml)a for indicated M. tuberculosis strain

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | ΔsigF mutantb | Complemented ΔsigF mutant | |

| Rifampin | 0.25 | 0.03125 | 0.625 |

| Rifapentine | 0.125 | 0.0625 | NDc |

| Isoniazid | 0.1 | 0.1 | ND |

| Ethambutol | 2.0 | 2.0 | ND |

| Streptomycin | 1.0 | 1.0 | ND |

| d-Cycloserine | 20 | 20 | ND |

MICs were determined by the Bactec method except for those for d-cycloserine, which were evaluated by agar dilution. Values are means of two to four determinations.

Values for rifampin and rifapentine represent eight- and twofold increases in susceptibility, respectively, with respect to the susceptibilities of the wild type.

ND, not done.

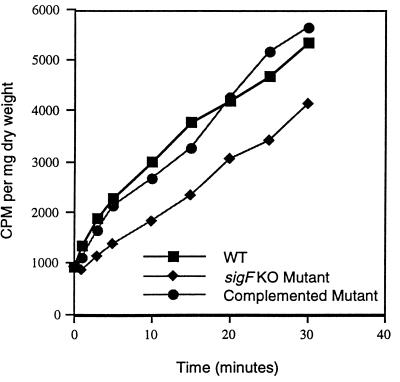

Because of these altered drug susceptibilities, we tested the mutant, wild-type, and complemented-mutant strains for rate of uptake of exogenous solutes, which might indicate alterations in the cell envelope or in cell wall-associated transport systems. As may be seen in Fig. 3, the M. tuberculosis ΔsigF mutant, but not the complemented strain, was less permeable to [14C]chenodeoxycholate in vitro than the wild type on the basis of the short-term uptake assay. Since chenodeoxycholate is a hydrophobic solute believed to enter mycobacteria through passive diffusion (40), these findings suggest that the sigF mutation produces structural alterations in the mycobacterial envelope which influence the passive diffusion rate.

FIG. 3.

[14C]chenodeoxycholate uptake by wild-type (WT) M. tuberculosis, the ΔsigF mutant, and the complemented mutant. Measured values for counts per minute taken up were normalized to the dry weight of bacterial pellets. Each value represents the mean of at least three determinations. Standard deviations were less than 5%. KO, knockout.

Phenotype in a human monocyte infection model.

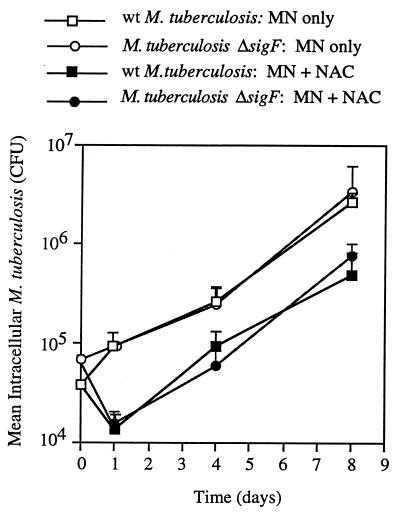

We studied the ability of the M. tuberculosis ΔsigF mutant to infect and proliferate within human monocytes in an in vitro infection model described previously (32, 33). We selected human peripheral monocytes because previous studies showed them to be a good surrogate for human alveolar macrophages (33) and because of their more direct relevance to human tuberculosis compared with animal macrophage lines. As shown in Fig. 4, the intracellular growth rates of the wild-type and ΔsigF strains were identical over the 8-day infection of monocytes from healthy, tuberculin-positive donors. To determine whether the two strains differed in their abilities to resist lymphocyte-mediated immune mechanisms, we also determined intracellular growth rates following addition of autologous PBL to infected monocytes in a 10:1 lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio. While the addition of PBL resulted in an initial burst of killing of intracellular M. tuberculosis at 24 h after infection, the magnitudes of this effect for the two strains did not differ and were comparable to that observed with laboratory strain H37Rv in the same assay (data not shown). Subsequent rates of growth of the organisms in cocultures of lymphocytes and infected monocytes were identical as well. These data indicate that the loss of the stationary-phase/stress response sigma factor gene sigF has no detectable effect on short-term intracellular survival and proliferation in human monocytes in vitro.

FIG. 4.

Intracellular survival of M. tuberculosis CDC1551 (wild type [wt]) and the isogenic ΔsigF mutant within monocytes (MN) or within MN plus PBL (nonadherent cells [NAC]) from four unrelated, tuberculin-positive, healthy human subjects. Each patient's cells were tested in triplicate under each of the conditions. Data points represent the surviving mycobacterial CFU per 106 MN plus 1 standard error.

Phenotype in a mouse infection model.

We investigated the in vivo phenotype of the M. tuberculosis ΔsigF mutant in the mouse tuberculosis model by analysis of median time to death. BALB/c mice infected with wild-type M. tuberculosis displayed significant weight loss about 100 days after infection in contrast to those infected with an equal number of cells of the ΔsigF mutant (Fig. 5A). All wild type-infected mice died within 184 days of infection (median survival, 161 days), while mutant-infected mice survived for up to 334 days (median survival, 246 days; P < 0.001 by Kaplan-Meier analysis), as may be seen in Fig. 5B. This long-term mouse survival study indicates that loss of sigF reduces the virulence of M. tuberculosis for mice.

FIG. 5.

Characteristics of infection by M. tuberculosis CDC1551 (wild type) versus the M. tuberculosis ΔsigF mutant in mice. Results are from a long-term infection model using 6- to 8-week-old BALB/c mice infected with wild-type (n = 12) and mutant (n = 11) M. tuberculosis, respectively. (A) Individual weights were determined biweekly and are plotted as mean weight per group ± 1 standard error. Asterisks, times at which the weight differences achieved statistical significance. (B) Survival data are shown as a Kaplan-Meier plot. The median time to death was 161 days for wild-type infection and 246 days for infection with the ΔsigF mutant.

DISCUSSION

In this study we report the interruption of the M. tuberculosis sigF gene by allelic exchange and we present a phenotypic analysis of the resulting mutant. Our in vitro analysis revealed few distinct differences between the ΔsigF mutant and the wild type. Importantly, the only exogenous stress condition for which the mutant was at increased susceptibility was exposure to rifamycin drugs, and with these drugs the change in MIC was relatively small (two- to eightfold). We also found that the ΔsigF mutant displayed reduced uptake of the hydrophobic solute chenodeoxycholate, suggesting that the mutant might have cell envelope permeability differences from the wild type. Both the rifampin hypersusceptibility and chenodeoxycholate uptake phenotypes were reversed or partially reversed by sigF complementation, indicating that they are sigF-mediated effects and not due to the presence of the hygromycin resistance gene or to a spurious second-site mutation. While the basis of rifampin hypersusceptibility in the M. tuberculosis ΔsigF mutant remains uncertain, it is unlikely to be related to increased permeability to the drug. Our chenodeoxycholate uptake experiments indicate that, if anything, the mutant is less permeable to exogenous solutes. Also, other drugs including isoniazid, ethambutol, and streptomycin did not show MIC changes as might be expected if the mutant had a general defect in permeability. Since an earlier study showed rapid induction of sigF expression in Mycobacterium bovis BCG exposed to various doses of rifampin (24), one hypothesis to account for the rifampin phenotype is that mycobacteria may have a baseline susceptibility to rifampin equivalent to that of the ΔsigF mutant, with sigF expression serving as an adaptive mechanism to achieve inducible resistance.

sigF has been reported to be induced by a number of in vitro stress conditions, including temperature, oxidative, and stationary-phase stress, using a reporter gene assay (24), while another study using molecular beacons and real-time PCR detection showed little effect of these conditions on sigF mRNA expression in vitro (22). A study of differentially expressed genes upon entry into macrophages found that sigF induction occurred at 18 h but that sigF expression levels returned to baseline by 48 h after infection (16). In the present paper, neither temperature shift, oxidative stress, entry into stationary phase, nor macrophage infection elicited a survival difference between the ΔsigF mutant and the wild type. Thus while M. tuberculosis sigF expression may be induced by these conditions, increased sigF expression does not appear to be essential for bacterial survival under these environmental conditions. This may reflect an abundance of overlapping stress response regulatory pathways in tubercle bacilli designed to ensure survival. Our study did not address the survival of the ΔsigF mutant in activated macrophages. Several reports have found that gamma interferon significantly enhances both phagosome maturation and the mycobacterial inhibitory capacity of macrophages (31, 36). Although we have observed that coincubation of macrophages with PBL leads to secretion of significant levels of gamma interferon and that there was no difference between the survival of the mutant and that of the wild type in the coincubation model, it remains possible that cytokine preactivation of macrophages might unmask an intracellular survival defect of the ΔsigF mutant in vitro.

Despite the relative lack of in vitro phenotypes, our mouse survival data reveal that the sigF gene plays a role in virulence in the whole animal. While loss of sigF does not prevent the mutant strain from producing a lethal infection, death is significantly delayed in BALB/c mice infected by the mutant strain. Although BALB/c mice have been classified as resistant to M. tuberculosis (23), this mouse strain exhibits a Th2 cytokine response to M. tuberculosis infection which is associated with increased susceptibility to the infection (18). It is possible that greater differences in virulence between the ΔsigF mutant and the wild type might be observed in other mouse strains such as C57BL/6 which are resistant and respond to infection with a Th1 profile. Future studies are being directed towards identifying the stage at which the M. tuberculosis sigF gene is needed in animal infections and whether the disease produced by the ΔsigF mutant differs immunopathologically.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank L. Moulton, T. Larson, B. Schofield, and J. Gomez for technical advice and N. Gauchet for assistance in manuscript preparation.

This work was supported by NIH grants AI36973, AI37856, AI35207, HL59858, and ES03819 and ALA grant RG-148-N. R. F. Silver is a recipient of a Parker B. Francis Fellowship in Pulmonary Research sponsored by the Francis Families Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Becker L A, Cetin M S, Hutkins R W, Benson A K. Identification of the gene encoding the alternative sigma factor ςB from Listeria monocytogenes and its role in osmotolerance. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4547–4554. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4547-4554.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan P F, Foster S J, Ingham E, Clements M O. The Staphylococcus aureus alternative sigma factor ςB controls the environmental stress response but not starvation survival or pathogenicity in a mouse abscess model. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6082–6089. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6082-6089.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry III C E, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Barrell B G. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins D, Kawakami R, de Lisle G, Pascopella L, Bloom B, Jacobs W., Jr Mutation of the principal ς factor causes loss of virulence in a strain of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8036–8040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.8036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dannenberg A M., Jr Immunopathogenesis of pulmonary tuberculosis. Hosp Pract. 1993;28:51–58. doi: 10.1080/21548331.1993.11442738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeMaio J, Zhang Y, Ko C, Bishai W R. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis sigF gene is part of a gene cluster organized like the Bacillus subtilis sigF and sigB operons. Tuber Lung Dis. 1997;78:3–12. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(97)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeMaio J, Zhang Y, Ko C, Young D, Bishai W. A stationary phase stress-response sigma factor from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2790–2794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deretic V, Schurr M J, Boucher J C, Martin D W. Conversion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to mucoidy in cystic fibrosis: environmental stress and regulation of bacterial virulence by alternative sigma factors. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2773–2780. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.2773-2780.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doukhan L, Predich M, Nair G, Dussurget O, Mandic-Mulec I, Cole S, Smith D, Smith I. Genomic organization of the mycobacterial sigma gene cluster. Gene. 1995;165:67–70. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00427-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang F C, Libby S J, Buchmeier N A, Loewen P C, Switala J, Harwood J, Guiney D G. The alternative ς factor KatF (RpoS) regulates Salmonella virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11978–11982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.11978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandes N D, Wu Q L, Kong D, Puyang X, Garg S, Husson R N. A mycobacterial extracytoplasmic sigma factor involved in survival following heat shock and oxidative stress. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4266–4274. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.14.4266-4274.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finlay B B, Falkow S. Common themes in microbial pathogenicity revisited. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:136–169. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.2.136-169.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garbe T, Barathi J, Barnini S, Zhang Y, Abou-Zeid C, Tang D, Mukherjee R, Young D. Transformation of mycobacterial species using hygromycin resistance as selectable marker. Microbiology. 1994;140:133–138. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-1-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomez J E, Chen J M, Bishai W R. Sigma factors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis. 1997;78:175–183. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(97)90024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomez M, Doukhan L, Nair G, Smith I. sigA is an essential gene in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:617–628. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graham J E, Clark-Curtiss J E. Identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis RNAs synthesized in response to phagocytosis by human macrophages by selective capture of transcribed sequences (SCOTS) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11554–11559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haldenwang W. The sigma factors of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:1–30. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.1-30.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernandez-Pando R, Orozcoe H, Sampieri A, Pavon L, Velasquillo C, Larriva-Sahd J, Alcocer J M, Madrid M V. Correlation between the kinetics of Th1, Th2 cells and pathology in a murine model of experimental pulmonary tuberculosis. Immunology. 1996;89:26–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobs W, Jr, Kalpana G, Cirillo J, Pascopella L, Snapper S, Udani R, Jones W, Barletta R, Bloom B. Genetic systems for mycobacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:537–555. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04027-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee M H, Pascopella L, Jacobs W R, Jr, Hatfull G F. Site-specific integration of mycobacteriophage L5: integration-proficient vectors for Mycobacterium smegmatis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and bacille Calmette-Guérin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3111–3115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lurie M. Studies on the mechanism of immunity in tuberculosis: the fate of tubercle bacilli ingested by mononuclear phagocytes derived from normal and immunized animals. J Exp Med. 1942;75:247–268. doi: 10.1084/jem.75.3.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manganelli R, Dubnau E, Tyagi S, Kramer F, Smith I. Differential expression of 10 sigma factor genes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:715–724. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medina E, North R J. Resistance ranking of some common inbred mouse strains to Mycobacterium tuberculosis and relationship to major histocompatibility complex haplotype and Nramp1 genotype. Immunology. 1998;93:270–274. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michele T, Ko C, Bishai W R. Antibiotic exposure induces expression of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis sigF gene: implications for chemotherapy against mycobacterial persistors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:218–225. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller J F, Mekalanos J J, Falkow S. Coordinate regulation and sensory transduction in the control of bacterial virulence. Science. 1989;243:916–922. doi: 10.1126/science.2537530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murray C J, Lopez A D. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: global burden of disease study. Lancet. 1997;349:1498–1504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pablos-Mendez A, Raviglione M C, Laszlo A, Binkin N, Rieder H L, Bustreo F, Cohn D L, Lambregts-van Weezenbeek C S B, Kim S J, Chaulet P, Nunn P. Global surveillance for antituberculosis-drug resistance, 1994-1997. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1641–1649. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806043382301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pelicic V, Jackson M, Reyrat J M, Jacobs W R, Jr, Gicquel B, Guilhot C. Efficient allelic exchange and transposon mutagenesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10955–10960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pelicic V, Reyrat J M, Gicquel B. Expression of the Bacillus subtilis sacB gene confers sucrose sensitivity on mycobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1197–1199. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.4.1197-1199.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Potuckova L, Kelemen G H, Findlay K C, Lonetto M A, Buttner M J, Kormanec J. A new RNA polymerase sigma factor, ςF, is required for the late stages of morphological differentiation in Streptomyces sp. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:37–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17010037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schaible U E, Sturgill-Koszycki S, Schlesinger P H, Russell D G. Cytokine activation leads to acidification and increases maturation of Mycobacterium avium-containing phagosomes in murine macrophages. J Immunol. 1998;160:1290–1296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silver R F, Li Q, Boom W H, Ellner J J. Lymphocyte-dependent inhibition of growth of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv within human monocytes: requirement for CD4+ T cells in purified protein derivative-positive, but not in purified protein derivative-negative subjects. J Immunol. 1998;160:2408–2417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silver R F, Li Q, Ellner J J. Expression of virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis within human monocytes: virulence correlates with intracellular growth and induction of tumor necrosis factor alpha but not with evasion of lymphocyte-dependent monocyte effector functions. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1190–1199. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1190-1199.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stead W. Pathogenesis of a first episode of chronic pulmonary tuberculosis in man: recrudescence of residuals of the primary infection or exogenous reinfection? Am Rev Respir Dis. 1967;95:729–745. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1967.95.5.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valway S E, Sanchez M P, Shinnick T F, Orme I, Agerton T, Hoy D, Jones J S, Westmoreland H, Onorato I M. An outbreak involving extensive transmission of a virulent strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:633–639. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803053381001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Via L E, Fratti R A, McFalone M, Pagan-Ramos E, Deretic D, Deretic V. Effects of cytokines on mycobacterial phagosome maturation. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:897–905. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.7.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiedmann M, Arvik T J, Hurley R J, Boor K J. General stress transcription factor ςB and its role in acid tolerance and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3650–3656. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.14.3650-3656.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu Q-L, Kong D, Lam K, Husson R N. A mycobacterial extracytoplasmic function sigma factor involved in survival following stress. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2922–2929. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2922-2929.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu S, de Lencastre H, Tomasz A. Sigma-B, a putative operon encoding alternate sigma factor of Staphylococcus aureus RNA polymerase: molecular cloning and DNA sequencing. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6036–6042. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.20.6036-6042.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuan Y, Zhu Y, Crane D D, Barry C E., III The effect of oxygenated mycolic acid composition on cell wall function and macrophage growth in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1449–1458. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]