Abstract

Background

Education is an important step toward achieving equity in health care. However, there is little published literature examining the educational outcomes of curricula for resident physicians focused on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI).

Objective

Our objective was to review the literature to assess the outcomes of curricula for resident physicians of all specialties focused on DEI in medical education and health care.

Methods

We applied a structured approach to conducting a scoping review of the medical education literature. Studies were included for final analysis if they described a specific curricular intervention and educational outcomes. Outcomes were characterized using the Kirkpatrick Model.

Results

Nineteen studies were included for final analysis. Publication dates ranged from 2000 to 2021. Internal medicine residents were the most studied. The number of learners ranged from 10 to 181. The majority of studies were from a single program. Educational methods ranged from online modules to single workshops to multiyear longitudinal curricula. Eight studies reported Level 1 outcomes, 7 studies reported Level 2 outcomes, 3 studies reported Level 3 outcomes, and only 1 study measured changes in patient perceptions due to the curricular intervention.

Conclusions

We found a small number of studies of curricular interventions for resident physicians that directly address DEI in medical education and health care. These interventions employed a wide array of educational methods, demonstrated feasibility, and were positively received by learners.

Introduction

Graduate medical education about health care equity is an important step toward eliminating disparities. In recognition of this, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has enacted several changes to the Common Program Requirements addressing issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion, as well as the ACGME Equity Matters initiative.1 In order to meet the growing demand for education in this space, residency programs across all specialties have introduced topics such as diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in health care into their formal curricula, which vary widely by regional patient population needs, medical specialty, and scope of practice.

Despite the educational efforts to improve resident physician knowledge, skills, and attitudes, the sum of the published literature describing outcomes, such as learner changes in behavior or impact on patient care, has not been well characterized to date. We conducted a needs assessment of the existing literature to identify gaps and inform future efforts toward designing curricula in this space. The objective of our study was to perform a scoping review of the existing literature on curricular interventions in graduate medical education regarding DEI with a focus on educational outcomes using the Kirkpatrick Model2 as a framework.

Methods

We conducted a review of the medical education literature published prior to August 12, 2021, within the MEDLINE database, using methodology described by Cook and West and following PRIMSA guidelines for scoping reviews.3,4 Using an iterative process among the authors, one with expertise in health equity (C.O.) and one in medical education research (A.S.C.), we developed inclusion criteria and search terms. Our population of interest was resident physicians in graduate medical education programs of all specialties. We looked specifically for curricular interventions with measurable and reported outcomes focused on the topics of DEI in medical education and health care. Using the Medical Subject Heading “graduate medical education” and the search term “curriculum,” we cross-referenced the literature for the following search terms: diversity, inclusion, health equity, inequity, antiracism, cultural competency, critical race theory, implicit bias, microaggressions, and racism. Titles and abstracts of identified articles were screened for relevance by the first author of this study (A.S.C.). Intra-rater agreement was performed following the initial selection, and no additional studies were included or excluded. Publications were included for final analysis if they had a clearly stated and primary curricular objective focused specifically on DEI with reported outcomes. All other publication types were excluded, including abstracts, opinion pieces, and literature reviews. References of relevant articles were subsequently screened by one member of the study team (A.C., S.D., E.P., R.G., J.A., or C.O.) for additional publications that may have been missed by the search protocol.

For studies that met inclusion criteria through the search strategy identified above, the full article was reviewed by one member of the study team (A.S.C., A.C., S.D., E.P., R.G., J.A., or C.O.) to collect additional data including publication year, specialty, study population, number of learners, type of study, type of curriculum and brief description, measured outcomes, and main findings. Statistical findings were also included if available. Using previously published methodology, outcomes were classified by the authors according to the Kirkpatrick Model, which categorizes educational outcomes using increasing levels of complexity and impact.5 In this model, Level 1=reaction/satisfaction, Level 2=learning, Level 3=behavioral change, and Level 4=patient outcomes.2 Outcomes for each study were determined by the first author and one other study team member (A.C., S.D., E.P., R.G., J.A., or C.O.). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus.

This study was determined to be exempt by the Institutional Review Board of Maimonides Medical Center.

Results

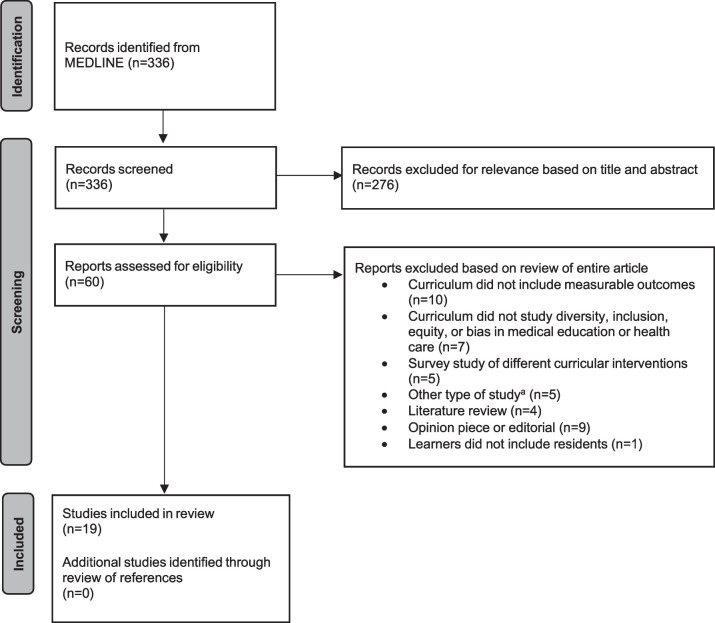

Our initial search strategy yielded 336 results. After screening titles and abstracts for inclusion, 60 articles remained for review. These articles were read in their entirety and assessed for eligibility based on the inclusion criteria. Nineteen articles were included for final analysis (Figure 1). No additional studies were identified through a review of references. Publication dates ranged from 2000 to 2021, with 74% (14 of 19) of included studies having been published since 2017 (Table).

Figure 1.

Search Strategy

a Other types of studies included assessment of non-curricular interventions (n=3) and surveys of educators (n=2).

Table.

Summary of Studies Included for Final Analysis

| First Author (Year) Journal | Title | Specialty | Population | Brief Curriculum Design | Educational Methods | Measured Outcome(s) | Kirk patrick Level | Main Findings (P values reported if available) |

| Ogunyemi (2021)6 Journal of Graduate Medical Education | Defeating Unconscious Bias: The Role of a Structured, Reflective, and Interactive Workshop | OB/GYN; FM; IM; Psych | Residents, faculty, program coordinators, medical students at a single institution (n=181) | Single 90-minute workshop to assess implicit bias. Workshop included a short lecture, video presentation, and 2 small group discussions (10 min each). Facilitator role unspecified. | Small group facilitated discussion | Pre-/post-survey to assess perceptions and knowledge | 2 | Significant increases in total perception scores (P<.001) and total knowledge scores (P<.001). |

| Ramadurai (2021)7 MedEdPORTAL: The Journal of Teaching and Learning Resources | A Case-Based Critical Care Curriculum for Internal Medicine Residents Addressing Social Determinants of Health | IM; FM; EM | Residents at a single institution (n=32) | Once weekly case-based 30-minute discussions over 4 weeks, following multidisciplinary rounds in the ICU. Combined with direct observation and templated feedback for residents on incorporation of social risk assessments. Facilitators were chief residents, MICU fellows, and a unit social worker. Facilitator training involved reviewing a facilitator guide and prompt questions. | Small group facilitated discussion | Pre-/post-survey to assess self- perceived change in knowledge, skills, and attitudes | 1 | Increased knowledge of resources for patients experiencing health disparities due to substance abuse (pre: 47%, post: 73%) and financial constraints (pre: 50%, post: 64%). |

| Fune (2021)8 MedEdPORTAL: The Journal of Teaching and Learning Resources | Lost in Translation: An OSCE-Based Workshop for Helping Learners Navigate a Limited English Proficiency Patient Encounter | Pediatrics | Residents at a single institution (n=40) | Single 3-hour workshop with a panel discussion, best practices presentation, video demonstration, and observing scenarios. Included a simulation-based OSCE pre-session, practice simulation sessions and debrief, followed by a post-session OSCE with feedback. Facilitators were certified health interpreters and hospital faculty. Facilitator training involved 60-minute practice sessions and pre-session didactics. | Small group discussion; formal lecture; simulation | Satisfaction surveys; pre-/post-workshop OSCEs | 3 | High learner satisfaction scores. Improved pre- vs. post-workshop OSCE performance (P<.01). |

| Chary (2021)9 Western Journal of Emergency Medicine | Addressing Racism in Medicine Through a Resident-Led Health Equity Retreat | EM | Residents and faculty at a single institution (n=56) | Three 1-hour sessions during a health equity retreat: (1) an interactive presentation about forms of racism; (2) workshop devoted to microaggressions using a 15-minute presentation, followed by small group discussion; and (3) impact of patient race on the management of agitated patients in the ED delivered by a panel of EM attendings, social workers, and psychiatrists. Facilitators were senior residents, including one resident with background in anthropology and race theory. No facilitator training specified. | Small group discussion; formal lecture | Satisfaction survey | 1 | 100% reported improved understanding of diversity in the workplace. 94% found sessions very or extremely useful. Major themes included need for continued discussion and involvement of key stakeholders. |

| Ufomata (2020)10 MedEdPORTAL: The Journal of Teaching and Learning Resources | Comprehensive Curriculum for Internal Medicine Residents on Primary Care of Patients Identifying as Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, or Transgender | IM | Residents at a single institution (n=153) | Four 45-minute modules over 4 months consisting of small group facilitated case-based discussions addressing 4 main content areas: (1) understanding gender and sexuality; (2) performing a sensitive history and physical examination; (3) health promotion and disease prevention; and (4) mental health, violence, and reproductive health. General medicine faculty facilitated these modules. Facilitator training involved review of a written facilitator guide. | Small group discussion | Satisfaction survey; pre-/post-survey to assess knowledge | 2 | Significant increase in confidence about providing resources to patients and to institute gender-affirming practices (P<.05). Significant increase in knowledge (P<.0001). |

| Zeidan (2019)11 Western Journal of Emergency Medicine | Targeting Implicit Bias in Medicine: Lessons from Art and Archaeology | EM; IM | Residents and medical students at a single institution (n=26) | Single workshop consisting of a pre-brief with session leaders; viewing 3 objects using a tool called “deep description” and a post-session reflective discussion. Facilitators were anthropologists and archaeologists. No facilitator training specified. | Small group discussion | Satisfaction survey; pre-/post-workshop surveys to assess self- reported understanding of implicit bias | 1 | Improved understanding of implicit bias (67%) and greater empowerment to address own biases (61%). |

| Jacobs (2019)12 Family Medicine | A Longitudinal Underserved Community Curriculum for Family Medicine Residents | FM | Residents at a single institution (n=22) | Three-year curriculum of workshops and seminars focused on social determinants of health and cultural competency. Facilitators were faculty practicing in underserved areas. Seminars were led by guest speakers. No facilitator training specified. | Small group discussion, simulation, formal lecture | Satisfaction survey; pre-/post-knowledge tests | 2 | Significant confidence (P<.03) and knowledge increases (P<.0001) in caring for people of culturally diverse backgrounds. |

| Dennis (2019)13 Family Medicine | Learner Reactions to Activities Exploring Racism as a Social Determinant of Health | FM | Residents and fellows at a single institution (n=37) | One-year curriculum consisting of lectures, workshops, and tours. Topics centered around privilege, intersectionality, levels of racism, and equity. Facilitators were a FM physician and a behavioral psychologist. No facilitator training specified. | Mixed methods: Workshops, didactics, interactive tours | Quantitative (Likert scale response) and qualitative (free test response) analysis of satisfaction surveys | 1 | Mean reactions ranged from 4.4-4.67 on a Likert scale of 1-5. Thematic analysis showed subjective increase in self-assessed understanding of racism and awareness. |

| Udyavar (2018)14 Journal of Surgical Education | Qualitative Analysis of a Cultural Dexterity Program for Surgeons: Feasible, Impactful, and Necessary | Surgery | General surgery residents at 3 institutions (n=32) | One-year curriculum consisting of flipped classroom e-learning modules with interactive role-playing sessions. Facilitators and facilitator training unspecified. | E-learning, small group discussion; simulation | Qualitative analysis of focus group discussions for learner reaction and satisfaction | 2 | Five major themes were identified: role modeling, relevance, barriers, buy in, and camaraderie and shared experiences. |

| Rosendale (2017)15 Neurology | Residency Training: The Need for an Integrated Diversity Curriculum for Neurology Residency | Neurology | Residents at a single institution (n=24) | Lecture series, developed from needs assessment survey of neurology program directors. Lecturers were community leaders, faculty, and trained interpreters. | Formal lectures | Satisfaction survey; pre-/post-workshop self- reported confidence navigating clinical scenarios | 1 | Improved appreciation of transgender health issues (P=.003); more skill in understanding impact of individual's disability (P=.009); more skill in assessing medical literacy (P=.044); and more comfort in apologizing for cross-cultural errors (P=.048). |

| Maguire (2017)16 Journal of Graduate Medical Education | Using a Poverty Simulation in Graduate Medical Education as a Mechanism to Introduce Social Determinants of Health and Cultural Competency | Unspecified | Residents at a single institution (n=74) | Three-hour simulated experience as a low- income family unit. Faculty, hospital staff, and community volunteers were embedded participants playing roles of police, teachers, and government workers. No specific facilitator or role training specified. | Simulation | Satisfaction survey including free text responses; pre-/post-surveys to assess opinions on poverty and equity | 2 | Feedback from participants, including free text responses, was unanimously positive supporting the exercise as a valuable, educational, and well-executed event. |

| Horky (2017)17 Maternal and Child Health Journal | Evaluation of a Cross Cultural Curriculum: Changing Knowledge, Attitudes, and Skills in Pediatric Residents | Pediatrics | Residents at a single institution (n=66) | Six online modules (cross cultural case stories); and control group that had no intervention. | E-learning | Pre-/post-surveys to assess knowledge, attitudes, and skills | 2 | Pre-test results showed no significant difference between the 2 groups (invention and control); post-test the intervention group had significantly higher scores in knowledge (P<.001); attitudes (P=.002); and skills (P=.016). |

| Basu (2017)18 Academic Medicine | Training Internal Medicine Residents in Social Medicine and Research-Based Health Advocacy: A Novel, In-Depth Curriculum | IM | Residents at a single institution (n=32) | Embedded curriculum into a yearlong ambulatory clinical rotation. One hundred hours of curricular instruction organized within two 2-week immersion blocks and 18 additional hours of didactics. Curriculum was delivered through small-group sessions consisting of lectures and group discussions, field trips, and research and advocacy skill workshops. Includes a group research-based health advocacy project. Facilitators were faculty. No facilitator training specified. | Small group discussion, formal lectures; field trips, workshops; group project | Satisfaction surveys; scholarly output | 3 | Residents rate the overall quality of the course highly (5.2 on 1-6 scale). Thirty-one residents have been involved as presenters and/or coauthors at national conferences. |

Table.

Summary of Studies Included for Final Analysis (continued)

| First Author (Year) Journal | Title | Specialty | Population | Brief Curriculum Design | Educational Methods | Measured Outcome(s) | Kirk patrick Level | Main Findings (P values reported if available) |

| Neff (2017)19 Journal of General Internal Medicine | Teaching Structure: A Qualitative Evaluation of a Structural Competency Training for Resident Physicians | FM | Residents at a single institution (n=12) | Three-hour session with presentation of a case and then discussion in the context of social determinants of health and advocacy. The session was prepared and facilitated by a working group of physicians, nurses, medical anthropologists, health administrators, community health activists, and graduate and professional students in several disciplines. | Formal lectures, small group discussion | Satisfaction survey; focus group 1 month after to assess impacts on clinical practice | 1 | Residents reported feeling overwhelmed by their increased recognition of structural influences on health, and the language they learned lowered barriers to having these conversations with their patients. |

| Chun (2014)20 Journal of Surgical Education | The Refinement of a Cultural Standardized Patient Examination for a General Surgery Residency Program | Surgery | Residents at a single institution (n=20) | Standardized patient encounter with videotaped pre- and post-test standardized assessments by a faculty member directly observing the encounter; combined with additional education via journal club and self-reflective writing; formal lecture. | Simulation, journal club, and self- reflective writing; formal lecture | Pre-/post-cross cultural care survey assessing knowledge, skills, and attitudes; pre-/post-checklist rating following SP encounter | 3 | Learners born outside the United States had higher scores on attitude (P=.02), but no differences were found in skill, knowledge, or overall rating. For overall rating, there was significant pretest to posttest change (P=.04). Students born in the United States demonstrated a significant increase in ratings (P=.01), whereas students who were not born in the United States showed little change (P=.74). |

| Staton (2013)21 Medical Education Online | A Multimethod Approach for Cross-Cultural Training in an Internal Medicine Residency Program | IM | Residents, students, staff, and faculty at a single institution (n=35) | Weeklong multi-method curriculum. Learners completed 5 online modules, attended dedicated noon conferences, watched a webinar by a national expert, attended small group discussions as well as a panel discussion, and dedicated grand rounds session. Small group facilitators and facilitator training unspecified. | E-learning modules, formal lectures, small group discussions, panel discussions | Post-session survey to assess satisfaction and confidence in cross-cultural encounters | 1 | 71% of participants believed they would be able to provide better care to culturally diverse patients; 81% noted improved confidence in cross-cultural encounters. |

| Harris (2008)22 Academic Psychiatry | Multicultural Psychiatric Education: Using the DSM-IV-TR Outline for Cultural Formulation to Improve Resident Cultural Competence | Psych | Residents in a single program (n=22) | Nine-week multi-method curriculum, alternating between large group lectures and experiential small group discussions. Two faculty facilitators were assigned per group and included volunteers from psychiatry, psychology, and social work. No facilitator training specified. | Formal lectures, small group discussion | Pre/post (immediate and 9-month) survey to assess knowledge, skills, and attitudes | 2 | Increase in 7 of 10 items for self-assessed multicultural knowledge/skills and increase in 4 of 7 clinical application items (P<.05). With the exception of awareness of privilege, 9-month follow-up scores were not significantly different. |

| Hershberger (2008)23 Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved | Implementation of a Process-Oriented Cultural Proficiency Curriculum | FM | Residents in a single program (n=12) | Four-month program (one 2-hour session per month) that included cultural didactic sessions and journal club. Learners also completed a pre-/post-curriculum survey and SP encounter. Faculty were facilitators. No facilitator training specified. | Small group discussion, interactive large group activities, and simulation | Satisfaction survey; pre-/post-knowledge tests and attitude surveys; pre-/post-videotaped reviews of patient encounters; pre-/post-patient perception surveys | 4 | No significant differences between pre-/post-test knowledge. No significant differences in pre-/post-behavior assessments and patient surveys. |

| McGarry (2000)24 Academic Medicine | Enhancing Residents' Cultural Competence Through a Lesbian and Gay Health Curriculum | IM | Residents in a single program (n=23) | Three-hour seminar addressed lesbian and gay health care issues consisting of: (1) didactics about the historical medical treatment of lesbians and gay men; (2) small-group discussions exploring the barriers to health care for lesbians, gay men, and other underserved populations; (3) review of a videotape entitled Tools for Caring about Lesbian Health, followed by discussion; (4) didactic instruction outlining the unique health care issues of lesbians and gay men, with specific suggestions for creating safe spaces; and (5) case discussions, including an adolescent struggling with sexual identity, the difficulty of dealing with the loss of a partner, and domestic violence among gays and lesbians. It concluded with open discussion of any remaining issues. Facilitators and facilitator training were unspecified. | Formal lecture, small group discussions, case discussions | Satisfaction survey | 1 | 96% (22 of 23) felt more prepared to care for lesbian and gay patients after the seminar; 70% (16 of 23) rated the seminar outstanding, and the rest rated it excellent. |

Abbreviations: OB/GYN, obstetrics and gynecology; FM, family medicine; IM, internal medicine; Psych, psychology; EM, emergency medicine; MICU, medical intensive care unit; OSCE, objective structured clinical examination; ED, emergency department; SP, standardized patient.

Study Participants

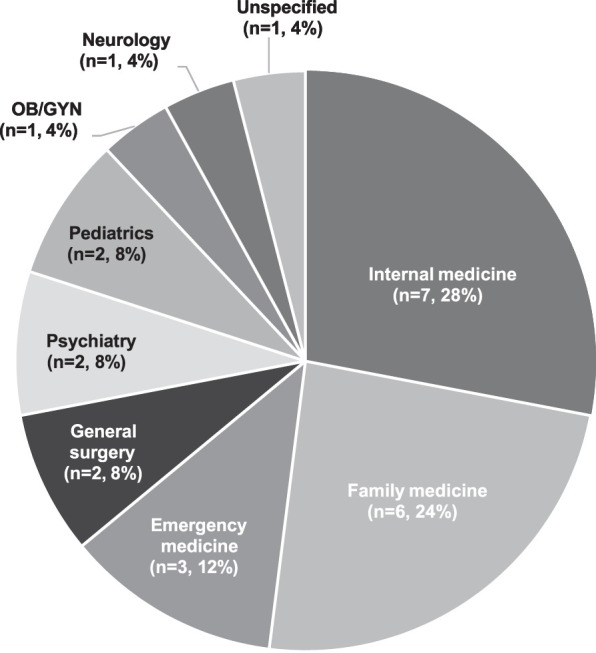

We found a total of 899 learners who participated in curricular interventions that met our inclusion criteria. Internal medicine represented the largest number of studies from a single specialty (37%, 7 of 19), followed by family medicine (32%, 6 of 19) and emergency medicine (16%, 3 of 19; Figure 2). One study did not specify the specialties of the residents involved.

Figure 2.

Specialties Reporting Measured Educational Outcomes.

Abbreviation: OB/GYN, obstetrics and gynecology.

While the majority of studies involved residents from a single program (63%, 12 of 19), several included residents from multiple programs within the same institution (32%, 6 of 19). One program studied residents in the same specialty (general surgery) from 3 different institutions. The number of total learners participating in each curriculum ranged from 10 to 181. A few studies also included learners who were not residents, such as medical students, fellows, faculty, and non-physician hospital staff.

Types of Curricular Interventions

Educational methods ranged from online modules to single workshops to multiyear longitudinal curricula. The most common educational method used was facilitated small group discussion (79%, 15 of 19). Other educational methods included formal lectures (53%, 10 of 19), simulation cases or standardized patients (21%, 4 of 19), and online self-directed modules (16%, 3 of 19). A few unique methods included a journal club, field trips or tours, and self-reflective writing. Many curricula incorporated multiple different educational methods. The majority of curricular interventions occurred as a single session (37%, 7 of 19), with the length of the session ranging from 90 minutes to 3 hours. The remainder occurred as multiple sessions over a span of several months to a year. One study described a 3-year longitudinal multi-modal curriculum.

Measured Outcomes

The majority of studies reported Kirkpatrick Level 1 or 2 outcomes (84%, 16 of 19). Level 1 outcomes were most commonly assessed using post-intervention satisfaction surveys. Two studies conducted focus groups to assess learner reaction. Learning was most commonly demonstrated through a comparison of pre- and post-intervention knowledge testing. Two studies reported Level 3 outcomes using simulation and scholarly output of learners. One study included patient satisfaction surveys, a measure of impact on patient outcomes due to the curricular intervention.

Main Findings

Overall, the studies included for analysis demonstrated feasibility of implementation, and their curricula were positively received by learners. Eleven studies were able to show an improvement in knowledge or behavior with regards to DEI in medical education and health care.

Discussion

Despite the recognized importance of education on DEI, we found a paucity of evidence describing meaningful educational outcomes for residents.

We found only 19 studies that met our inclusion criteria. Despite our search of the peer-reviewed literature accessible online any time prior to 2021, the earliest study we found was published in 2000, and the overwhelming majority were published in just the last 5 years. This is both disheartening and encouraging. Quality medical education research in this area has been sparse in the past but seems to be increasing in line with our greater sociocultural awareness of the importance of these issues and changes to the ACGME Common Program Requirements. It is possible that many more educational interventions are in their early phases of development and implementation, and thus not captured in this review, which would be consistent with the exponential growth we have observed to date.

Specialties at the front line of care access, such as internal medicine and family medicine, had the highest number of studies represented in this review of the literature. Interestingly, a greater number of physicians who identify as Black, Hispanic, or Native American currently practice primary care (41.4%, 36.7%, and 41.5%, respectively) compared to physicians who identify as White (30.6%).25 The ACGME recognizes and provides accreditation for 28 specialties, and it is worth noting that only 8 of these specialties have published educational interventions with measured outcomes. Physicians of all specialties have a responsibility to provide equitable and compassionate care to patients of diverse backgrounds, and there is still much work to be done.

We found that the most frequently used educational method was small group facilitated discussion. We also observed a surprising number of methods outside of lecture-based didactics, such as field trips, tours, written self-reflection, electronic or online learning, and journal clubs. Issues such as DEI are highly nuanced and complex. The effectiveness in delivering this content to improve the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of resident physicians is profoundly affected by each learner's unique background and life experience. Interactive methods, such as small group facilitated discussion, have been demonstrated to be well-received by learners and more effective than traditional lectures for complex topics.26,27

We used the Kirkpatrick Model to characterize the studies included in our analysis, following the methodology of other scoping reviews of curricular interventions.7,28 The majority of the studies reported Kirkpatrick Level 1 or 2 outcomes. We recognize that the Kirkpatrick levels are not a definitive hierarchy of quality, and that learner satisfaction may be the primary goal depending on the objectives of the educational intervention. Only 3 studies reported a Kirkpatrick Level 3 or 4. We acknowledge the difficulty in assessing behavioral change and patient outcomes. However, these types of outcomes are important in order to inform educators of best practices for training resident physicians. Further study is needed to understand how resident education in this area can impact patient care.

We felt that a scoping review, rather than a comprehensive systematic review, was a more appropriate methodology to map the literature. It is possible that we would have identified additional studies for final inclusion had we used more than one author to screen titles and abstracts. We instead employed a defined set of screening criteria developed by 2 authors and engaged the screening author to ascertain intra-rater agreement for inclusion. Interventions may also exist in the non-peer reviewed literature or in the gray literature, including abstracts, conference proceedings, reports, or dissertations.

Many types of educational interventions that broadly prepare residents to care for patients of different backgrounds were not included in our analysis. We focused our inclusion criteria on interventions with a clearly stated and primary curricular objective focused on DEI in health care or medical education. All other studies fell outside the scope of this review, such as studies on the use of interpreters, medical management of special populations, and development of global health rotations. It is also possible that we may have missed relevant studies if our key concepts of interest were not included explicitly in the title or abstract.

Conclusions

In this scoping review of the literature, we found a small number of studies of curricular interventions for resident physicians that directly address DEI in medical education and health care. Specialties at the front line of care access had the greatest number of studies represented in this sample. Overall, these studies employed a wide array of interactive educational methods, demonstrated feasibility of implementation, and were positively received by learners.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Zakir Gulam for research support.

Funding Statement

Funding: The authors report no external funding source for this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare they have no competing interests.

This study was previously presented as a poster presentation at the virtual ACGME Annual Educational Conference, February 24-26, 2021; and Maimonides Medical Center Evening of Research, May 4, 2021, Brooklyn, NY.

References

- 1.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. What We Do: Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. 2022. Accessed on June 24. https://www.acgme.org/what-we-do/diversity-equity-and-inclusion/

- 2.Kirkpatrick DL, Kirkpatrick JD. Evaluating Training Programs The Four Levels 3rd ed. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook DA, West CP. Conducting systematic reviews in medical education: a stepwise approach. Med Educ . 2012;46(10):943–952. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med . 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung AS, Mott S, Rebillot K, et al. Wellness interventions in emergency medicine residency programs: review of the literature since 2017. West J Emerg Med . 2020;22(1):7–14. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.11.48884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogunyemi D. Defeating unconscious bias: the role of a structured, reflective, and interactive workshop. J Grad Med Educ . 2021;13(2):189–194. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-20-00722.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramadurai D, Sarcone EE, Kearns MT, Neumeier A. A case-based critical care curriculum for internal medicine residents addressing social determinants of health. MedEdPORTAL . 2021;17:11128. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fune J, Chinchilla JP, Hoppe A, et al. Lost in translation: an OSCE-based workshop for helping learners navigate a limited English proficiency patient encounter. MedEdPORTAL . 2021;17:11118. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chary AN, Molina MF, Dadabhoy FZ, Manchanda EC. Addressing racism in medicine through a resident-led health equity retreat. West J Emerg Med . 2021;22(1):41–44. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.10.48697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ufomata E, Eckstrand KL, Spagnoletti C, et al. Comprehensive curriculum for internal medicine residents on primary care of patients identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender. MedEdPORTAL . 2020;16:10875. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeidan A, Tiballi A, Woodward M, Di Bartolo IM. Targeting implicit bias in medicine: lessons from art and archaeology. West J Emerg Med . 2019;21(1):1–3. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2019.9.44041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs C, Seehaver A, Skoid-Hanlin S. A longitudinal underserved community curriculum for family medicine residents. Fam Med . 2019;51(1):48–54. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2019.320104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dennis SN, Gold RS, Wen FK. Learner reactions to activities exploring racism as a social determinant of health. Fam Med . 2019;51(1):41–47. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2019.704337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Udyavar R, Smink DS, Mullen JT, et al. Qualitative analysis of a cultural dexterity program for surgeons: feasible, impactful, and necessary. J Surg Educ . 2018;75(5):1159–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosendale N, Josephson SA. Residency training: the need for an integrated diversity curriculum for neurology residency. Neurology . 2017;89(24):e284–e287. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maguire M, Kottenhahn R, Consiglio-Ward L, Smalls A, Dressler R. Using poverty simulation in graduate medical education as a mechanism to introduce social determinants of health and cultural competency. J Grad Med Educ . 2017;9(3):386–387. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00776.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horky S, Andreola J, Black E, Lossius M. Evaluation of a cross cultural curriculum: changing knowledge, attitudes, and skills in pediatric residents. Matern Child Health J . 2017;21(7):1537–1543. doi: 10.1007/s10995-017-2282-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basu G, Pels RJ, Stark RL, Jain P, Bor DH, McCormick D. Training internal medicine residents in social medicine and research-based health advocacy: a novel, in-depth curriculum. Acad Med . 2017;92(4):515–520. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neff J, Knight KR, Satterwhite S, Nelson N, Matthews J, Holmes SM. Teaching structure: a qualitative evaluation of a structural competency training for resident physicians. J Gen Intern Med . 2017;32(4):430–433. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3924-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chun MBJ, Deptula P, Morihara S, Jackson DS. The refinement of a cultural standardized patient examination for a general surgery residency program. J Surg Educ . 2014;71(3):398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staton LJ, Estrada C, Panda M, Ortiz D, Roddy D. A multimethod approach for cross-cultural training in an internal medicine residency program. Med Educ Online . 2013;18:20352. doi: 10.3402/meo.v18i0.20352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris TL, McQuery J, Raab B, Elmore S. Multicultural psychiatric education: using the DSM-IV-TR outline for cultural formulation to improve resident cultural competence. Acad Psych . 2008;32(4):306–312. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.32.4.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hershberger PJ, Righter EL, Zryd TW, Little DR, Whitecar PS. Implementation of a process-oriented cultural proficiency curriculum. J Health Care Poor Underserved . 2008;19(2):478–483. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGarry K, Clarke J, Cyr M. Enhancing residents' cultural competence through a lesbian and gay health curriculum. Acad Med . 2000;75(5):515. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200005000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019, Executive Summary. Accessed on June 24, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/media/38266/download?attachment .

- 26.Lerchenfeldt S, Attardi SM, Pratt RL, Sawarynski KE, Taylor TA. Twelve tips for interfacing with the new generation of medical students: iGen. Med Teach . 2021;43(11):1249–1254. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1845305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pluta WJ, Richards BF, Mutnick A. PBL and beyond: trends in collaborative learning. Teach Learn Med . 2013;25(suppl 1):9–16. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2013.842917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walpola RL, McLachlan AJ, Chen TF. A scoping review of peer-led education in patient safety. Am J Pharm Educ . 2018;82(2):6110. doi: 10.5688/ajpe6110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]