Abstract

Background

Despite increasing prevalence of longitudinal clinician educator tracks (CETs) within graduate medical education (GME) programs, the outcomes of these curricula and how participation in these tracks affects early career development remains incompletely understood.

Objective

To describe the experience and outcomes of participating in a CET and its effects on recent internal medicine residency graduates' perceived educator skills and early career development.

Methods

We conducted a qualitative study between July 2019 and January 2020 using in-depth semi-structured interviews of recently graduated physicians from 3 internal medicine residencies at one academic institution who had participated in a CET, the Clinician Educator Distinction (CED). Iterative interviews and data analysis was performed via an inductive, constructionist, thematic analysis approach by 3 researchers to develop a coding and thematic structure. Results were sent electronically to participants for member checking.

Results

From 21 (out of 29 eligible) participants, thematic sufficiency was reached at 17 interviews. Four themes related to the CED experience were identified: (1) motivation to go beyond the expectations of residency; (2) educator development outcomes from Distinction participation; (3) factors enabling curricular efficacy; and (4) opportunities for program improvement. A flexible curriculum with experiential learning, observed teaching with feedback, and mentored scholarship allowed participants to enhance teaching and education scholarship skills, join a medical education community, transform professional identities from teachers to educators, and support clinician educator careers.

Conclusions

This qualitative study of internal medicine graduates identified key themes surrounding participation in a CET during training, including positively perceived educator development outcomes and themes surrounding educator identity formation.

Introduction

The role of clinician educators (CEs) has become increasingly complex. With the rise of ambulatory care, competency-based education, interprofessional education, simulation, and other changes in medical education, CEs must now incorporate curriculum development, formulation of assessments, programmatic leadership, and scholarly work to prepare future generations of clinicians.1-5 Despite the important role of CEs, they have historically relied on “on-the-job” training, faculty development workshops, certificate programs, fellowships, and/or Master's degree programs to gain relevant educator competencies.6-13 The lack of formalized training and standardized career pathways, as well as institutional prioritization of clinical and research productivity, pose challenges to CE career development, satisfaction, recruitment, retention, and promotion.14-17 Academic programs require an established pipeline of educators to meet the needs of learners and systems.

While CE development in North America remains less formalized compared to Australia and Europe, the number of graduate medical education (GME) programs offering longitudinal “tracks,” “pathways,” “concentrations,” or “distinctions” in medical education during clinical training has increased in the last decade.18-20 Two recent scoping reviews found approximately 40 CETs across multiple GME specialties described in the literature. Shared components of these CETs across specialties included an average program length of 12 months, use of experiential teaching methods, incorporation of scholarly projects, and need for protected time for faculty and learners.19,20 However, evidence explaining if or why these programs are successful is limited. The scoping reviews noted heterogeneity in descriptions regarding CET structure and curricular content, as well as low-quality evidence to support such programs; those that reported outcomes were commonly limited to participant reactions to curricula, with few reporting early career tracking.19,20 Conceptual frameworks were rarely reported. The lived experience of CE skills and career development through participation in GME CETs, and factors contributing to an effective CET during medical training, remain poorly understood.

Social cognitive career theory (SCCT) has been identified as a framework guiding early individual career choices.21,22 SCCT postulates that career interests derive from individual self-efficacy beliefs, outcome expectations, and personal goals. These 3 factors are influenced by direct and vicarious experiences, as well as the context and culture to which an individual is exposed. SCCT has previously been applied to identity formation of researchers and CEs.21,23,24 Studies have also explored the effects of participating in scholarly concentration programs on career selection in undergraduate medical education and GME using this framework.23,25-27

The purpose of this study is to describe the experience and outcomes of participation in a longitudinal CET on graduates from 3 internal medicine residency programs at a single institution. A constructionist, thematic approach was used to explore the lived experience of residents, reflections on the impact of the CET, and career choices following completion of training. Results from this study are explored using the SCCT framework.

Methods

Intervention and Context

The Clinician Educator Distinction (CED) was launched within the Yale internal medicine residency programs in 2016 as 1 of 4 “Distinction” pathways. The distinctions are optional, 2-year programs aimed to provide augmented training in medical education (Clinician Educator), research (Investigation), global health (Global Health and Equity), or health care systems (Physician Leadership and Quality Improvement). All distinctions include a core curriculum, experiential activities, scholarly projects, and faculty mentorship. Residents are invited to apply to join one distinction at the beginning of their postgraduate year (PGY)-2. Those who fulfill respective completion requirements receive a certificate of distinction at graduation.

The objective of the CED is to develop residents' skills across educator competencies to facilitate future careers as CEs. To graduate with the CED certificate, residents must meet a minimum of 85 activity credits spread across 4 domains: (1) education theory; (2) observed teaching with feedback; (3) medical education scholarship; and (4) leadership/administration (Table 1). Residents are not provided protected time but can use elective or research blocks to complete distinction requirements. Details regarding the CED curriculum, including funding and faculty support, can be found in the online supplementary data.

Table 1.

Credit Requirements to Graduate With the Yale Clinician Educator Distinction

| Didactics and Observation (35 credits) | Teaching With Direct Feedback (30 credits) | Education Scholarship (20 credits) | Leadership and Administration (Optional) |

| CED evening curriculum sessions (2) | Medical student clinical skills workshops (5) | Institution-sponsored conference presentation (10) | CED resident leader (varies) |

| Institution-sponsored education or faculty development didactics (2) | Medical student case conferences or simulation (2) | Regional/national conference presentation (10) | Curriculum committee (varies) |

| Medical education conference attendance (5) | Resident peer teaching conferences (5) | Published education manuscript (20) | Regional/national education committee (varies) |

| Structured observation of faculty or peer teaching (1) | Bedside teaching (3) | Contribution to durable curricular material (5) | |

| Journal club (3) | Scholarship reviewing for journals or conferences (5) |

Abbreviation: CED, Clinician Educator Distinction.

Note: Credit totals in the header represent the minimum number of credits required per category; (n) indicates the number of credits assigned to each completed activity. Each credit represents an expected 1 hour of investment on the part of the trainee.

Data Collection

We conducted a qualitative study of the first 2 cohorts of Yale CED participants who completed internal medicine residency training in 2018 or 2019.

Eligible participants included graduates from all 3 internal medicine residency programs at Yale: the traditional internal medicine (T), primary care (PC), and internal medicine-pediatrics (MP) residency programs. Graduates who had enrolled in the CED but did not complete certification requirements were also eligible. Invitations were sent by email and informed consent obtained prior to each interview.

Two authors (Y.Y., K.G.) conducted in-depth, semi-structured, one-on-one interviews between July 2019 and January 2020. Interviews followed an open-ended interview guide (provided as online supplementary data) that was informed by the literature, study aims, SCCT framework, and was reviewed by faculty leaders of the CED. Questions explored perceived benefits, efficacy of instructional methods, challenges to CED completion, motivations and expectations regarding CE careers, and experiences within the context of the educator community. Questions from the interview guide were iteratively adjusted with consensus between the authors as new concepts arose during data collection. Interviews were conducted in batches to allow for concurrent data analysis until no new concepts emerged. Interviews were audio recorded, professionally transcribed, and de-identified.

Additional data reported in this study regarding career paths and teaching and scholarly output were routinely collected via MedHub as part of distinction activity requirement tracking.

Data Analysis

We performed thematic analysis of de-identified transcripts using an inductive, constant comparative, constructionist approach via Dedoose. Each of the first 6 interview transcripts were coded independently by an initial team of 2 authors (Y.Y., K.G.) via open coding to generate a preliminary list of codes. Subsequent interviews were reviewed in batches by only one member of the coding team (either Y.Y. or K.G.), assigned such that the coder was not the same individual as the interviewer.

Once interviews were complete, a third author (C.S.) who had not participated in the interviewing process was included in the final coding team to ensure appropriate application of codes to transcripts and to review developing themes. The final coding team held regular meetings to iteratively modify the coding structure, reach consensus on transcript codes, and develop initial themes from coding memos. Coded texts were compared to analyze concepts and construct a final code book and thematic structure. The final coding structure was used to recode all transcripts.

The interview guide, coding structure, and resultant conceptual model were externally reviewed in consultation with expert educators trained in qualitative research in the Teaching and Learning Center at Yale School of Medicine.

Member Checking

All participants received a draft of the results by email and were invited to provide feedback regarding the identified themes. Nine participants responded to member checking, which did not lead to changes in study results.

Reflexivity

The research team consisted of an internal medicine fellow (Y.Y.), who was a founding member and graduate of the CED during their residency, a core faculty member of Yale Primary Care Residency Program (K.G.), and an associate program director of the Yale Traditional Residency Program (C.S.). All 3 authors were faculty co-directors of the CED. Two authors (Y.Y., K.G.) completed a scoping review on CETs in GME concurrent to the completion of this study.20

This study was deemed exempt from review by the Yale School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Results

Between 2018 and 2019, 23 residents graduated with the CED (10 in 2018, 13 in 2019). Six enrolled in but did not complete the program. Twenty-one of the 29 eligible individuals (72%) participated in interviews. Thematic sufficiency was reached after 17 interviews. Table 2 shows the demographics of study participants, their teaching and scholarly productivity during residency, and their post-residency role at the time of the interview.

Table 2.

Clinician Educator Distinction and Study Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | Total Enrolled, n (%); (n=29) | Interviewed, n (%); (n=21) |

| CED cohort year | ||

| 2016-2018 | 15 (52) | 10 (48) |

| 2017-2019 | 14 (48) | 11 (52) |

| CED completion | ||

| Completed program | 23 (79) | 19 (90) |

| Did not complete program | 6 (21) | 2 (10) |

| Training program | ||

| Traditional | 19 (66) | 12 (57) |

| Primary care | 6 (21) | 5 (24) |

| Internal medicine–pediatrics | 4 (14) | 4 (19) |

| Female gender | 17 (59) | 14 (67) |

| Participated in resident as teacher electivea | 7 (24) | 7 (33) |

| Mean teaching sessions led per participantb | ||

| Morning report | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| Bedside teaching | 1.7 | 1.6 |

| Journal club | 1.1 | 2.0 |

| Didactic conference | 1.9 | 2.1 |

| Medical student skills workshop | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Total scholarly output | ||

| Poster presentations, mean per participant | 1.5 | 1.3 |

| Oral presentations, cohort total | 2 | 2 |

| Book chapters, mean per participant | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| Peer-reviewed publications, cohort total | 8 | 7 |

| Post-residency activitiesc | ||

| Chief residency | 5 (17) | 4 (19) |

| Subspecialty fellowship | 10 (34) | 6 (29) |

| Medical education fellowship | 2 (7) | 2 (10) |

| Academic practice | 6 (21) | 3 (14) |

| Non-academic practice | 3 (10) | 2 (10) |

| Advanced research training | 3 (10) | 3 (14) |

| Mean months graduation to interview (range) | NA | 9 (3-20) |

Abbreviations: CED, Clinician Educator Distinction; NA, not applicable.

See online supplemental data for a description of the elective.

As recorded for CED completion credit requirements; may not reflect total teaching sessions outside these requirements.

At time of study (fall 2019-winter 2020).

We identified 4 thematic domains as part of our analysis: (1) motivation to go beyond the expectations of residency; (2) educator development outcomes from distinction participation; (3) factors enabling curricular efficacy; and (4) opportunities for program improvement (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinician Educator Distinction Experience—Themes, Subthemes, and Representative Quotes

| Themes, Subthemes | Representative Quotes |

| Theme 1: Motivation to Go Beyond the Expectations of Residency | |

| Intrinsic motivators | “I have always been interested in medical education. I had done a similar distinction program in medical school, even before this…So I would say [I applied] just to get more exposure to medical education in general. Both theory and also practically. The opportunity to teach and be observed.” (T12) |

| Extrinsic motivators | “We have these talents that we develop and it's difficult to convey that in something like a CV…to have a distinction in education I think it makes it obvious to anyone who's looking through your application regardless of what you're applying to, that you have some background in education.” (T3) “It seemed like doing a distinction pathway was an incredible opportunity even though I didn't know a ton about it. It just seemed like, ‘Don't pass this up'.” (T8) |

| Theme 2: Early Educator Development Outcomes From Distinction Participation | |

| Clinician educator self-efficacy | “One of the biggest things that it impacted for me was I could see a difference in my teaching between doing things on the fly versus things that were prepared. And when I say prepared, I don't just mean in terms of being like a knowledge content expert, but also trying to remember the techniques that I'd been taught. I think by recalling those techniques and trying to incorporate them best, is one of the biggest things that has changed for me. What I try to do now, if I know that I'm going to be teaching on something, I just try to review those techniques that I've learned.” (T2) “The pathway—specifically some of those evening sessions—I took away actionable skills. So, some of the ways I act when attending [are] affected by that. The projects that I did that counted towards the pathway are things that I'm still developing further and have become a big part of my academic focus and niche.” (PC2) |

| Professional identity development | “What I ended up doing for my CED scholarship thing was related to the [writing] course that [another resident] and I put together. I wouldn't have necessarily thought of that as something that could be scholarly, if I hadn't had this distinction…I think I had little understanding of the system of how people get promoted, or how people even do scholarship, or how people parse their time out, before [the CED]. I think just having a deeper understanding of academia in general, but also just what being an educator can look like, it's not just strictly medical students or strictly residents.” (MP2) “The CED definitely made me more interested in having a career in medical education. The one thing that I found that I didn't necessarily love was the sort of research project aspect of medical education. So, I think it was actually helpful for me to get some exposure to that and realize that I enjoy teaching, the teaching environment and all those things, I didn't necessarily enjoy as much the formal academic research part of medical education.” (T9) |

| Enhanced job search | “It made me sound more informed on the interview trail for fellowship…I think being able to talk intelligently about understanding that medical education, as a career, is not just ‘I love to teach,' but how do you substantively buy some of your time and have a dedicated role as a clinician-educator.” (MP3) |

| Membership in educator community | “It was just the community that existed of clinician educators to know that people so valued it and to then inspire my self-driven search for how do you become a good clinical educator. More through experience just by signing up to do physical exam rounds or actually delivering part of the POCUS curriculum. I think that those experiences taught me a lot. It was the community that the CED built for me that I took away the most from the distinction.” (T5) |

| Theme 3: Factors Enabling Curricular Efficacy | |

| Flexible requirements and experiential learning | “It actually keeps you a little more focused on accomplishing that goal by having requirements that you have to turn in. I don't know that I would have necessarily made so many of them because I think that the actual going to the meetings and the practice stuff and being observed—I think all of that was the most valuable. I thought the… [curriculum sessions] themselves were probably my favorite part of the whole thing…” (T10) |

| Increased opportunities for observed teaching with feedback | “I like the evaluation sheets. I think they standardize something that could otherwise be like, ‘But he observed me and gave me verbal feedback.' They show that somebody observed you and gave you feedback. And they give you a thing to reference in the future, which is nice.” (MP1) |

| Exposure to educator community and role models | “The exposure to faculty that were doing clinical education was helpful and just also reinforcing that being involved with teachers and learners is something that I liked. And so I think that it reinforced to me that I did want some sort of academic career. I wouldn't want to be completely removed from the clinical education component of a career.” (T9) |

| Theme 4: Opportunities for Program Improvement | |

| Accessibility of curriculum events | “[The didactics] would start at 6:00 or 6:30pm, and a lot of our sign-outs and then some of our rotations you don't get out until 7. So when I was on those I didn't really attend [the didactics], or there was no protected time for people and the track to go to these.” (T7) |

| Mentors with education research skills | “The [faculty] I worked with was phenomenal but not as well versed in medical education research. So the methodology I think we used wasn't the best.” (T6) |

| Logistics and navigation of requirements | “I think keeping track of what I had completed and not putting them in [MedHub], and not counting things the right way was really frustrating. Especially as I was graduating, I got this email from [the CED administrator] being like, ‘Oh, you're not meeting the requirements for any of the sections.' And I was like, ‘Well, I was actually smart enough to keep track of them according to what it actually should be.' And I was actually meeting every single one of them. But it's just annoying and stressful when you know that you are meeting requirements, and this other person is telling you that you're not.” (T7) |

Abbreviations: CED, Clinician-Educator Distinction; T, traditional internal medicine; PC, primary care; MP, internal medicine-pediatrics; POCUS, point-of-care ultrasonography.

Motivation to Go Beyond the Expectations of Residency

Many participants had pre-existing intentions to engage in teaching activities and would have sought opportunities similar to those offered by the CED independent of the distinction. Most described a longstanding interest in medical education and a history of seeking opportunities to participate in teaching (eg, serving as a teacher's assistant in college or medical school). Participants also joined the CED to focus on skills that might have garnered less attention earlier in their training. The extra time needed to focus on these skills through the CED was considered worthwhile and feasible (Table 3).

Additionally, participants reported that receiving credit or being observed gave them a sense of motivation to expend additional effort:

“The CED gave me sort of more [impetus] because I wanted to fulfill as many of the requirements as I could. So, I may have still done it but it definitely gave me sort of that push to be like ‘Oh, you should continue with this.'” (MP4)

Some graduates participated in the CED from a perception that they might be “missing out.” Having the opportunity to distinguish themselves as early educators was an additional external motivator for participation.

Early Educator Development Outcomes From Distinction Participation

Graduates reflected that they developed tangible skills for CE careers through CED participation, such as teaching in a variety of formats, adjusting teaching to different levels of learners, providing feedback, learning to critically appraise the teaching of others, and developing and assessing education interventions. Many also attributed increased self-efficacy in their current post-graduation jobs to the techniques and concepts developed through the CED. Participants also discovered previously unrecognized gaps in their skills and identified resources for continued development (Table 3).

The CED helped participants develop a clearer understanding of the breadth of CE careers. For example, many initially applied to the CED with hopes of becoming CEs but were focused solely on clinical teaching skills development. Through the CED, participants learned that CEs are involved in more than clinical teaching:

“I didn't really know what I didn't know, so I didn't know what to ask or what to think about. But just that idea that a huge chunk of folks [say], ‘Oh yeah, I love teaching, I love teaching.' But that alone is not going to get you a job as an educator being paid to just sit around educating.” (PC1)

Many graduates reflected on gaining a better appreciation of medical education scholarship, the role of scholarship in CE advancement, and the logistics by which CEs gain “protected time” for education. Graduates were able to calibrate this deeper understanding of CE careers with their own personal and professional interests. For some, the CED nurtured an interest in incorporating scholarship into their professional identities, while others determined that they preferred pursuing careers focused on clinical teaching without scholarship pressures.

Graduates noted that the CED enhanced their post-residency fellowship applications or job searches. Some felt more competent in documenting their skills and having informed discussions about educator career goals. Graduates also felt the CED equipped them with a better understanding of how to navigate early careers as CEs. Several chose to pursue additional medical education scholarship training.

Finally, the CED introduced participants to a broader group of peers and faculty within the medical education community. Identification with this community allowed participants to interact with like-minded peers within a safe learning climate. Networking opportunities at the undergraduate medical education and GME levels facilitated further practice and improved their teaching. Additionally, participants found role models for career development and professional identity formation:

“I might have gone this way one way or another in terms of getting an academic position, but I do think [the CED] helps because education [has] not always been the most popular route to go. But seeing other people who are attending, who are successful, and who are enjoying what they're doing as role models, is a really helpful thing to see for your own career.” (T2)

Factors Enabling Curricular Efficacy

Participants reported the CED curricular structure helped them reach their personal goals. They remarked on the numerous teaching opportunities offered to CED participants, as well as the positive impact of direct observation and feedback on skill development. Other effective features included flexible credit requirements, assigned advisors to navigate the distinction and connect with mentors, and opportunities for active learning and application of skills. Several of these factors—notably experiential workshops and direct observation and feedback on teaching—were reported as effective even by those who did not complete the distinction. Those who did complete the CED said the time commitment was reasonable (Table 3).

Opportunities for Program Improvement

A commonly identified area of improvement was the need for flexibility of distinction workshop scheduling to accommodate resident schedules. Barriers included call schedules, sign-out times, childcare responsibilities, and wellness needs. Many of the suggestions to improve access to didactic sessions centered around varying the time of day of the didactics and recording them for asynchronous learning. The need to leverage technology, like Twitter, Zoom, and mobile devices, was also mentioned (Table 3).

As noted in the supplement, residents are assigned a CED faculty advisor who assists them in finding a scholarship mentor. Graduates raised several recommendations to improve interactions with faculty, including increasing the frequency of meetings and more defined mentorship expectations, especially surrounding scholarship. Specifically, graduates felt many mentors in the CED were excellent clinical teachers but did not have the necessary skills to support their scholarly projects.

Additional areas for improvement included communicating a clearer set of pathway requirements, incorporation of a more streamlined web interface for credit tracking, reduction of “busywork” when observing others teach, and increasing structured discussion and reflection with peers.

Balancing CED requirements and competing priorities was the main reason some participants did not complete the distinction. However, these participants appreciated the opportunity to engage in CED activities even though they were not formally part of the distinction:

“I didn't know from like a time standpoint if I was going to be able to fulfill all the requirements, and so I didn't want to necessarily be a burden on the leadership...So that's why I just figured it'd be better to not formally do it, but still pick and choose a few things that I enjoy and thought would be helpful to me.” (T9)

Discussion

The findings of this qualitative study reflect the experience and outcomes of a concentrated, longitudinal CE training curriculum for internal medicine trainees. While prior studies on CETs in GME showed these programs are associated with positive outcomes in terms of participant satisfaction and gains in teaching efficacy, many studies did not describe their curricula in detail, were methodologically limited, and described low Kirkpatrick level outcomes.19,20 Our study adds to the literature by providing clarification on how curricular components of CETs can contribute to educator skills, identity formation, and early career development.

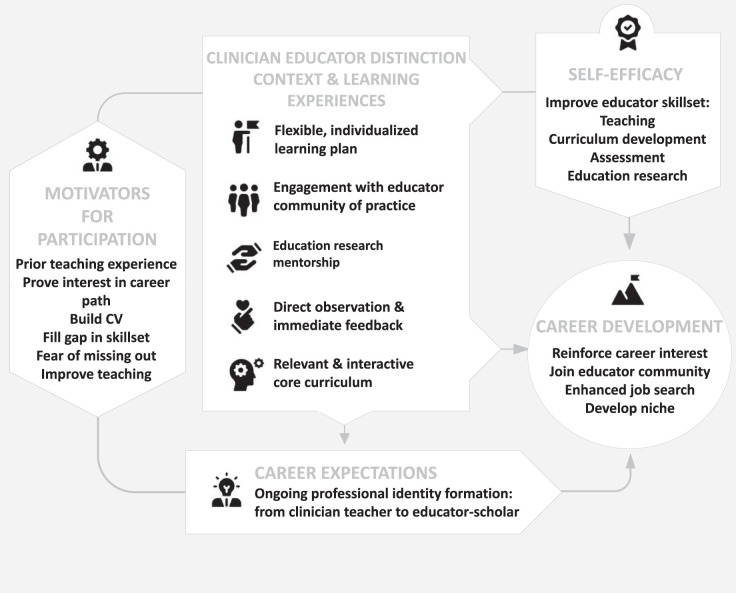

The Figure shows a conceptual model of the relationship between identified themes. Residents entered the CED with both intrinsic and extrinsic motivators for participation. They identified several factors that allowed them to build educator skillsets and further hone career aspirations, including experiential and interactive learning activities with direct observation and feedback on teaching, participation in mentored scholarship, integration into an educator community with exposure to role models, and flexible curricular requirements. Additionally, through these curricular components, participants were able to develop granular expectations of how medical education would factor into their future careers, allowing them a nuanced ability to “talk the talk” and articulate these goals to potential employers or fellowship programs.

Figure.

Thematic Diagram of Effect of Clinician Educator Distinction Participation on Graduates' Career Development

Utilizing a SCCT framework provides clarification on these findings. By participating in the CED, graduates' educator self-efficacy beliefs are supported by lived accomplishments (teaching a morning report), vicarious experiences (observing other educators as role models), and the social and emotional state one is in at the time of such experiences (triumph from “going beyond the expectations of residency”). CED participation also affected outcome expectations (the belief that engaging in a CET would provide a “leg up” and ongoing educator identity formation). Goals to pursue CE careers are specifically tied to exposure to an educator community and shifts in self-efficacy and outcome expectations as a result of CED participation.21 While our study was not designed to determine whether the CED provided experiences not otherwise available in their training, graduates indicated that they felt CED participation “set them apart” from their peers.

This study has several pivotal implications. In a scoping review of CETs in GME, more than 90% of 36 CETs had instructional methods and content aimed to improve clinical teaching; however, 60% or fewer CETs included requirements surrounding independent scholarly projects, assessment, curriculum development, leadership, and career development.20 It is interesting to note that many participants in our study initially joined the CED identifying teaching as the main—if not sole—competency of a CE. Their appreciation of the diverse roles and skillsets of CEs broadened through experiential activities across several educator competencies, mandatory scholarship, and exposure to the larger educator community. With the recent publication of the Clinician Educator Milestones,28 our study supports that CETs should incorporate educator competencies across domains in order to encourage robust educator identity formation and skills development.

This study also illuminates the difference between CEs who identify as “medical educators” versus those who are “medical education researchers.” Often, these roles do not completely overlap. In fact, there is a growing movement within academic institutions to further separate CEs into “clinician teachers” and “clinician educator scholars,” with differing criteria for advancement and promotion.29 Our results suggest this difference is important for CETs to highlight so that (1) trainees can appropriately select and prepare for a suitable career path, and (2) programs can identify faculty with relevant expertise to serve as mentors.

Similar to other CETs described in the literature, the CED struggled with evening session attendance due to trainees' competing responsibilities. Interestingly, during the COVID-19 pandemic, attendance of virtual sessions improved without negatively affecting engagement. Virtual sessions may be an option for programs facing challenges in delivering content to all CET participants at the same time and location.

Our study has several limitations. All members of the research team were CED faculty at the time of the study. We attempted to reduce the effect of reflexivity and social desirability bias in several ways. Only 2 authors (Y.Y., C.S.) were actively involved in program development during the 3 years when study participants were residents in the CED pathway. Further, we enrolled graduated rather than current residents and believe this allowed us to capture candid and critical comments without participants fearing negative effects on standing within their training programs. We ensured that interviewers (Y.Y., K.G.) did not interview prior mentees. The lead faculty director (C.S.) did not recruit or interview participants but did participate in coding of anonymized transcripts. Finally, we incorporated external expert review of our coding structure and conceptual model and provided participants an opportunity to confirm our results through member checking.

Another limitation is that the CED evolved during the study period. As an earlier cohort, the 2018 CED graduates had fewer didactics and mentorship opportunities, as well as less stringent thresholds to obtain the distinction compared to the 2019 CED cohort. Our study also describes a single program within internal medicine. However, many aspects of the CED that participants found helpful are easily translatable to other specialties outside of internal medicine, and overlap with characteristics identified in the recent scoping reviews on CETs across GME.19,20 Finally, our study represents a relatively short follow-up period; interview and CV data from a longer follow-up interval would be informative to more directly assess career outcomes.

Conclusions

This qualitative study of internal medicine residency graduates identified key themes surrounding participation in a GME CET during training, including positively perceived educator development outcomes and themes surrounding educator identity formation.

Objectives

To describe the experience and effects on educator skills and career development of participation in a clinician educator track (CET) during residency.

Findings

Both internal and external factors motivate residents to participate in longitudinal CETs during residency. They experience skills development and educator identity formation through flexible curricula, experiential learning including opportunities to teach with feedback and mentored scholarship projects, as well as exposure to role models. Curricula designers should be aware of the growing difference in roles of clinician teachers and clinician educator scholars and how to prepare trainees interested in either career role.

Limitations

Data from this single institution study may not generalize to all other settings, and study authors were all faculty members of the CET.

Bottom Line

This study identifies and provides clarification on components of longitudinal CET curricula that help to prepare future clinician educators.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Clinician Educator Distinction co-directors, Drs. Geoffrey Connors, Dana Dunne, Steven Holt, Thilan Wijesekera, and David Vermette, for their collaboration and joint leadership in developing and maintaining the Distinction; the Department of Medicine and GME leadership, Drs. Gary Desir, Vincent Quagliarrelo, Steven Huot, Mark Siegel, John Moriarty, and Benjamin Doolittle for supporting the CED and Distinctions pathways; and the Yale Teaching and Learning Center for their support of medical educators and education scholarship within the Yale School of Medicine.

Funding Statement

Funding: The authors report no external funding source for this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare they have no competing interests.

This work was previously presented at the virtual Yale School of Medicine Medical Education Day, June 4, 2020.

References

- 1.Geraci SA, Babbott SF, Hollander H, et al. AAIM report on master teachers and clinician educators part 1: needs and skills. Am J Med . 2010;123(8):769–773. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heflin MT, Pinheiro S, Kaminetzky CP, McNeill D. ‘So you want to be a clinician-educator...': designing a clinician-educator curriculum for internal medicine residents. Med Teach . 2009;31(6):e233–e240. doi: 10.1080/01421590802516772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ibrahim H, Stadler DJ, Archuleta S, et al. Clinician-educators in emerging graduate medical education systems: description, roles and perceptions. Postgrad Med J . 2016;92(1083):14–20. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherbino J, Frank JR, Snell L. Defining the key roles and competencies of the clinician-educator of the 21st century: a national mixed-methods study. Acad Med . 2014;89(5):783–789. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srinivasan M, Li ST, Meyers FJ, et al. Teaching as a competency: competencies for medical educators. Acad Med . 2011;86(10):1211–1220. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822c5b9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams SE, Dewey CM. Identification of training opportunities in medical education for academic faculty. Med Teach . 2019;41(8):912–916. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2019.1592138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santhosh L, Abdoler E, Babik JM. Strategies to build a clinician-educator career. Clin Teach . 2020;17(2):126–130. doi: 10.1111/tct.13013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geraci SA, Kovach RA, Babbott SF, et al. AAIM report on master teachers and clinician educators part 2: faculty development and training. Am J Med . 2010;123(9):869–872e6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinert Y, Mann K, Anderson B, et al. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to enhance teaching effectiveness: a 10-year update: BEME guide no. 40. Med Teach . 2016;38(8):769–786. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2016.1181851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tekian A. Doctoral programs in health professions education. Med Teach . 2014;36(1):73–81. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.847913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tekian A, Harris I. Preparing health professions education leaders worldwide: a description of masters-level programs. Med Teach . 2012;34(1):52–58. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.599895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexandraki I, Rosasco RE, Mooradian AD. An evaluation of faculty development programs for clinician-educators: a scoping review. Acad Med . 2021;96(4):599–606. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000003813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Artino AR, Jr, Cervero RM, DeZee KJ, Holmboe E, Durning SJ. Graduate programs in health professions education: preparing academic leaders for future challenges. J Grad Med Educ . 2018;10(2):119–122. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-18-00082.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fleming VM, Schindler N, Martin GJ, DaRosa DA. Separate and equitable promotion tracks for clinician-educators. JAMA . 2005;294(9):1101–1104. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.9.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu WC, McColl GJ, Thistlethwaite JE, Schuwirth LW, Wilkinson T. Where is the next generation of medical educators. Med J Aust . 2013;198(1):8–9. doi: 10.5694/mja12.11654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levinson W, Rubenstein A. Integrating clinician-educators into academic medical centers: challenges and potential solutions. Acad Med . 2000;75(9):906–912. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200009000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atasoylu AA, Wright SM, Beasley BW, et al. Promotion criteria for clinician-educators. J Gen Intern Med . 2003;18(9):711–716. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.10425.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daaboul Y, Lin A, Vitale K, Snydman LK. Current status of clinician-educator tracks in internal medicine residency programmes. Postgrad Med J . 2021;97(1143):29–33. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2019-137188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedman K, Lester J, Young JQ. Clinician-educator tracks for trainees in graduate medical education: a scoping review. Acad Med . 2019;94(10):1599–1609. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Y, Gielissen K, Brown B, Spak JM, Windish DM. Structure and impact of longitudinal graduate medical education curricula designed to prepare future clinician-educators: a systematic scoping review: BEME guide no. 74. Med Teach . 2022;44(9):947–961. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2022.2039381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lent RW, Brown SD. Social cognitive model of career self-management: toward a unifying view of adaptive career behavior across the life span. J Couns Psychol . 2013;60(4):557–568. doi: 10.1037/a0033446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action A Social Cognitive Theory PrenticeHall Inc; 1986.

- 23.O'Sullivan PS, Niehaus B, Lockspeiser TM, Irby DM. Becoming an academic doctor: perceptions of scholarly careers. Med Educ . 2009;43(4):335–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bakken LL, Byars-Winston A, Wang MF. Viewing clinical research career development through the lens of social cognitive career theory. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract . 2006;11(1):91–110. doi: 10.1007/s10459-005-3138-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolfson RK, Alberson K, McGinty M, Schwanz K, Dickins K, Arora VM. The impact of a scholarly concentration program on student interest in career-long research: a longitudinal study. Acad Med . 2017;92(8):1196–1203. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young JQ, Sugarman R, Schwartz J, Thakker K, O'Sullivan PS. Exploring residents' experience of career development scholarship tracks: a qualitative case study using social cognitive career theory. Teach Learn Med . 2020;32(5):522–530. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2020.1751637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Young JQ, Schwartz J, Thakker K, O'Sullivan PS, Sugarman R. Where passion meets need: a longitudinal, self-directed program to help residents discover meaning and develop as scholars. Acad Psychiatry . 2020;44(4):455–460. doi: 10.1007/s40596-020-01224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Clinician Educator Milestones. Accessed Jan 1, 2023. https://www.acgme.org/what-we-do/accreditation/milestones/resources/clinician-educator-milestones/

- 29.Chang A, Schwartz BS, Harleman E, Johnson M, Walter LC, Fernandez A. Guiding academic clinician educators at research-intensive institutions: a framework for chairs, chiefs, and mentors. J Gen Intern Med . 2021;36(10):3113–3121. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06713-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.