Abstract

Purpose:

To describe those who reported meeting the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (2008 Guidelines) muscle-strengthening standard of 2 or more days per week, including all seven muscle groups, and to assess the type and location of muscle-strengthening activities performed.

Method:

Data from HealthStyles 2009, a cross-sectional, consumer mail-panel survey, was used for analyses (n = 4,271). The prevalence estimates with 95% confidence intervals of those meeting the 2008 Guidelines standards were calculated. Pairwise t-tests were performed to examine differences between estimates, tests for linear trends were performed among age, education, and body mass index (BMI) groups, and differences and trends were considered statistically significant at p < .05.

Results:

Overall, 6.0% of participants reported meeting 2008 Guidelines, and there were no significant differences between sex and racial/ethnic groups. A significant linear increase was noted among education groups, with respondents who reported lower levels of educational attainment having lower levels of participation compared with respondents who reported higher levels of educational attainment. A significant linear decrease was noted among each BMI group, with those classified as underweight/normal reporting higher levels of participation, compared with those classified as obese. Free weights and calisthenics were the most common types of activities; the home was the most common location.

Conclusions:

Few adults reported meeting current muscle-strengthening standards. Future public health efforts to increase participation should use the most frequently reported type and location of muscle-strengthening activities outlined in this study to guide interventions and communication campaigns.

Keywords: guidelines, physical activity, public health, strength training

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) recently released the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (2008 Guidelines), which provide updated guidance on the amount of muscle strengthening needed to produce health benefits (DHHS, 2008a). Muscle-strengthening activities may include calisthenics, resistance bands, weight machines, or free weights, and they can be performed in a variety of locations (e.g., the home, fitness facilities, outdoors). Musclestrengthening activities provide significant musculoskeletal and functional health benefits (DHHS, 2008b), and emerging evidence suggests that additional cardiovascular and metabolic benefits are provided as well, independent of aerobic activity (Church et al., 2010; Jackson et al., 2010; Jurca et al., 2005).

Similar to previous recommendations (e.g., Healthy People 2010 [U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000]), the 2008 Guidelines recommended that adults participate in moderate- to high-intensity muscle-strengthening activities on 2 or more days per week. However, the Advisory Committee for the 2008 Guidelines, citing additional scientific evidence, extended the recommendation to include the use of all seven major muscle groups (i.e., legs, hips, back, chest, abdomen, shoulders, and arms; DHHS, 2008b). The addition of the use of all muscle groups had not been previously included in physical activity recommendations.

National surveillance systems (e.g., the National Health Interview Survey) assess the frequency of muscle-strengthening activities (i.e., number of days per week); however, no current surveillance system assesses the use of muscle groups during strengthening activities or the type and location of muscle-strengthening activities performed. Using a recent survey of U.S. adults, the objectives of this study were to describe those who reported meeting the 2008 Guidelines muscle-strengthening standard of 2 or more days per week, including all seven muscle groups, and to assess the type and location of muscle-strengthening activities performed. To our knowledge, this is the first study to fully assess the 2008 Guidelines muscle-strengthening standards (i.e., days per week and inclusion of all major muscle groups).

METHODS

Data Source

Data for these analyses were obtained from the 2009 ConsumerStyles and HealthStyles databases. The consumer mail-panel surveys have been administered annually since 1995, and Synovate, Inc. (Chicago, IL) has conducted the sampling and data collection. Potential respondents were recruited to join the mail panel through a four-page recruitment survey. In 2009, approximately 328,000 potential respondents had previously agreed to participate in periodic surveys. If selected, participants in periodic surveys were provided small monetary incentives (e.g., $10) and were entered into a monetary sweepstakes (e.g., first place prize of $1,000; second place prizes of $50). ConsumerStyles and HealthStyles surveys are conducted in English and require a minimal level of reading comprehension to complete. ConsumerStyles collects information on a wide range of consumer attitudes, behaviors, media habits, and opinions. As a follow-up to the ConsumerStyles survey, HealthStyles collects information on health attitudes, behaviors, knowledge, conditions, and the environment. ConsumerStyles and HealthStyles do not recruit a representative sample of respondents. However, studies report that prevalence estimates from these surveys generally show good agreement with estimates from population-based surveys such as the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (Pollard, 2002, 2007).

ConsumerStyles and HealthStyles surveys were conducted in two waves during 2009. Beginning in April 2009, ConsumerStyles surveys were mailed to 21,420 randomly selected potential respondents from the mail panel of approximately 328,000. The sample was stratified to meet survey objectives by age, household income, household size, census region, and population density. Respondents from low-income and minority groups were oversampled, as were households with children, to ensure adequate representation of these groups. From April to May 2009, 10,587 persons completed the ConsumerStyles survey. Respondents who completed ConsumerStyles were then randomly selected to receive the HealthStyles survey (n = 7,004). From August to September 2009, 4,556 participants completed HealthStyles surveys. Among those contacted, 49.4% completed the ConsumerStyles survey and 65.0% completed the Health-Styles survey. Respondents who did not report muscle strengthening were excluded (n = 285), and this resulted in a final analytic sample of 4,271. Data received from Synovate, Inc., were deidentified and exempt from institutional review board approval.

Measures

Sociodemographic and descriptive data were collected in the ConsumerStyles and HealthStyles surveys. Demographic characteristics included sex (men/women), age (18–24 years, 25–34 years, 35–44 years, 45–64, ≥ 65 years), educational attainment (less than high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate), and marital status (married/partner, divorced/widowed/separated, never married). Self-reported height and weight measures were used to calculate body mass index (BMI) and were classified as underweight/normal (BMI ≤ 24.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m2; National Heart, Lung, & Blood Institute, 1998).

Five self-reported questions in the HealthStyles survey assessed the participation and description of muscle-strengthening activities conducted. Muscle-strengthening questions were developed from previous survey instruments (e.g., the National Health Interview Survey), and they were expanded and edited by subject-matter experts to include items not normally contained in national surveys. Respondents were asked about muscle-strengthening participation (yes/no), frequency (days per week), inclusion of muscle group(s) (i.e., shoulders, arms, back, chest, abdomen, legs, and hips), and type and location of muscle-strengthening activities performed during a usual week in the past month. Respondents reporting 2 or more days per week of muscle strengthening, including all seven major muscle groups, were classified as meeting the 2008 Guidelines. Multiple types (i.e., weight machines, resistance bands, calisthenics, handheld or free weights, yoga, or Tai Chi) and locations (i.e., free, nonprofit, or for-profit community fitness center[s], worksite, home, outdoors) of muscle-strengthening activities could be reported. Self-reported aerobic physical activity was collected and classified by using 2008 Guidelines minimum standards (DHHS, 2008a). The 2008 Guidelines recommend adults participate in at least 150 min of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity, 75 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity per week. When assessing the equivalent combination criterion, vigorous-intensity minutes were given twice the credit (multiplied by 2) and were combined with reported moderate-intensity minutes (DHHS, 2008a). Respondents reporting 150 min or more per week of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity were categorized as aerobically active, and those reporting less than 150 min were categorized as aerobically inactive.

Statistical Analyses

The prevalence estimates with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) of those meeting the 2008 Guidelines standards for muscle strengthening were calculated. Pairwise t-tests were performed to examine differences in prevalence estimates by certain characteristics, and tests for linear trends were performed among age and education groups. Differences and trends were considered significant at p < .05. Estimates of location and types of muscle-strengthening activities were reported among those meeting 2008 Guidelines standards for muscle strengthening. Data were weighted to U.S. Census population projections for 2009 by sex, age, income, race/ethnicity, and household size. Statistical analyses were performed using SUDAAN Version 9.0.

RESULTS

The demographic and descriptive distributions of the unweighted sample differed slightly from that of the sample weighted to the U.S. adult population (see Table 1). Differences among the unweighted and weighted samples were seen among age groups, among racial/ethnic groups, and by marital status. Compared with the weighted sample, the unweighted sample included a smaller percentage of adults aged younger than 34 years and a larger percentage of adults aged older than 45 years. The unweighted sample included a smaller percentage of Non-Hispanic Whites and a larger percentage of Non-Hispanic Blacks and Other, Non-Hispanics. Lastly, the unweighted sample had a higher percentage of married/partners and a lower percentage of never married, compared with the weighted sample.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Descriptive Characteristics Among Adults—HealthStyles, 2009

| Characteristic | n | Unweighted % | Weighted % (95% Confidence Intervals) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Men | 2,100 | 49.2 | 48.9 (46.6–51.2) |

| Women | 2,171 | 50.8 | 51.1 (48.8–53.4) |

| Age group (years) | |||

| 18–24 | 540 | 12.6 | 30.6 (27.9–33.5) |

| 25–34 | 808 | 18.9 | 18.8 (17.4–20.3) |

| 35–44 | 1,268 | 29.7 | 19.6 (18.3–20.9) |

| 45–64 | 789 | 18.5 | 14.7 (13.6–15.9) |

| 65 + | 866 | 20.3 | 16.2 (15.0–17.5) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 2,775 | 65.0 | 68.8 (66.7–70.9) |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 562 | 13.2 | 11.4 (10.1–12.9) |

| Hispanic | 607 | 14.2 | 13.5 (11.9–15.2) |

| Other, Non-Hispanica | 327 | 7.7 | 6.3 (5.6–7.2) |

| Education level | |||

| Less than high school graduate | 270 | 6.3 | 5.7 (4.7–6.9) |

| High school graduateb | 1,069 | 25.0 | 24.5 (22.5–26.6) |

| Some college | 1,570 | 36.8 | 37.8 (35.5–40.1) |

| College graduate | 1,362 | 31.9 | 32.0 (30.0–34.1) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/partner | 2,980 | 69.9 | 59.7 (57.2–62.2) |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 756 | 17.7 | 17.3 (15.8–19.0) |

| Never married | 530 | 12.4 | 23.0 (20.5–25.7) |

| Body mass index c | |||

| Underweight/normal weight (<25.0 kg/m2) | 1,234 | 28.9 | 30.9 (28.8–33.2) |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2) | 1,464 | 34.3 | 33.5 (31.3–35.7) |

| Obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) | 1,571 | 36.8 | 35.6 (33.4–37.8) |

Note. N = 4,271. Percentages may not add up due to rounding. Missing data: marital status = 5, body mass index = 2. Data are weighted to U.S. Census population projections for 2009 by sex, age, income, race/ethnicity, and household size.

Other races included: American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Other Pacific Islander.

Includes individuals with a GED or equivalent.

Body mass index = weight (kilograms)/height (meters2).

Overall, 31.7% (95% CI = 29.4–34.1) of respondents reported participation in muscle strengthening on 2 or more days per week, and 6.0% (95% CI = 5.0–7.1) of respondents reported participation in muscle strengthening on 2 or more days per week, including all seven major muscle groups (see Table 2). Overall, 57.6% (95% CI = 55.4–59.9) of respondents met minimum 2008 Guidelines standards for aerobic physical activity and were categorized as aerobically active. Among the population, 5.5% (95% CI = 4.5–6.6) met both the aerobic physical activity standards and the muscle-strengthening standards; 0.3% (95% CI = 0.2–0.5) met the muscle-strengthening standards but not the aerobic standards.

TABLE 2.

Adults Meeting 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for American Standards for Muscle Strengthening and Aerobic Physical Activity—Healthstyles, 2009

| Two Days/Week or More Muscle Strengthening and All Seven Major Muscle Groups |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two Days/Week or More Muscle Strengthening (n = 1,238) |

Meets Both Muscle-Strengthening Standards (n = 243) |

Meets Both Muscle-Strengthening Standards and Aerobic Standardsa (n = 216) |

Meets Both Muscle-Strengthening Standards but not Aerobic Standards (n = 17) |

|||||

| Characteristic | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI |

| Total | 31.7 | 29.4–34.1 | 6.0 | 5.0–7.1 | 5.5 | 4.5–6.6 | 0.3 | 0.2–0.5 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Men | 34.0 | 30.5–37.7 | 5.7 | 4.4–7.4 | 5.3 | 4.0–6.9 | 0.2 | 0.1–0.5 |

| Women | 29.5 | 26.6–32.5 | 6.2 | 4.8–7.9 | 5.6 | 4.3–7.4 | 0.4 | 0.2–0.7 |

| Age group (years) | ||||||||

| 18–24 | 36.3 | 30.1–43.0 | 6.2 | 3.9–9.9 | 6.0 | 3.6–9.6 | 0.1 | 0.0–0.7 |

| 25–34 | 34.4 | 30.9–38.2 | 7.0 | 5.3–9.1 | 6.5 | 4.9–8.6 | 0.2 | 0.1–0.7 |

| 35–44 | 30.7 | 27.9–33.6 | 6.9 | 5.4–8.6 | 6.3 | 4.9–8.0 | 0.5 | 0.2–1.2 |

| 45–64 | 27.4 | 24.2–31.0 | 4.6 | 3.3–6.5 | 3.9 | 2.6–5.6 | 0.2 | 0.1–1.0 |

| 65 + | 24.9 | 22.0–28.1 | 4.4 | 3.2–6.1 | 3.9 | 2.7–5.5 | 0.6 | 0.2–1.5 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 31.0 | 28.3–33.8 | 6.1 | 4.9–7.4 | 5.6 | 4.5–6.9 | 0.4 | 0.2–0.7 |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 31.3 | 24.7–38.7 | 6.9 | 4.3–10.8 | 6.3 | 3.8–10.2 | 0.1 | 0.0–0.5 |

| Hispanic | 34.7 | 28.0–42.2 | 4.6 | 2.0–10.2 | 4.4 | 1.8–10.1 | 0.1 | 0.0–0.8 |

| Other, Non-Hispanicb | 33.8 | 27.9–40.1 | 6.0 | 3.7–9.7 | 4.9 | 2.7–8.6 | 0.2 | 0.0–1.2 |

| Education level c | ||||||||

| < High school graduate | 17.3 | 11.6–25.0 | 2.4 | 1.1–5.1 | 1.9 | 0.9–4.3 | 0.5 | 0.1–3.5 |

| High school graduate | 25.3 | 20.5–30.9 | 4.3 | 2.8–6.3 | 3.7 | 2.4–5.8 | 0.4 | 0.1–1.0 |

| Some college | 32.3 | 28.4–36.4 | 5.0 | 3.5–7.1 | 4.4 | 3.0–6.6 | 0.3 | 0.1–0.7 |

| College graduate | 38.4* | 34.8–42.2 | 9.0* | 7.1–11.5 | 8.6* | 6.7–11.0 | 0.2 | 0.1–0.5 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married/partner | 32.0 | 29.7–34.3 | 6.6 | 5.5–7.9 | 6.0 | 4.9–7.4 | 0.3 | 0.2–0.5 |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 24.5 | 20.9–28.5 | 4.0 | 2.8–5.9 | 3.5 | 2.3–5.2 | 0.3 | 0.1–1.2 |

| Never married | 36.4 | 29.4–44.0 | 5.8 | 3.3–9.9 | 5.5 | 3.1–9.6 | 0.3 | 0.1–1.1 |

| Body mass index d | ||||||||

| Underweight/normal weight < 25.0 kg/m2) | 38.2 | 33.9–42.6 | 7.8 | 5.5–11.0 | 7.4 | 5.1–10.6 | 0.3 | 0.1–0.7 |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2) | 33.9 | 29.7–38.3 | 5.6 | 4.4–7.2 | 5.3 | 4.1–6.8 | 0.2 | 0.1–0.6 |

| Obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) | 24.0* | 21.0–27.2 | 4.7* | 3.5–6.2 | 4.0* | 2.9–5.4 | 0.4 | 0.2–0.8 |

Note. N = 4,271. Percentages may not add up due to rounding. Missing data: marital status = 5, body mass index = 2, aerobic physical activity = 109.

Meeting aerobic standards defined as at least 150 min of moderate-intensity physical activity per week, or at least 75 min of vigorous-intensity physical activity per week, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity physical activity (n = 2,264).

Other races included: American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Other Pacific Islander.

Includes individuals with a GED or equivalent.

Body mass index = weight (kilograms)/height (meters2).

p < .01.

Differences in prevalence of reported muscle-strengthening participation (both without and with the requirement of all seven major muscle groups) by demographic characteristics and BMI were assessed (see Table 2). Significant within-group findings for those reporting 2 or more days per week of muscle strengthening were seen among age groups (18–24 years vs. 45–64 years and 65 years and older; 25–34 years vs. 45–64 years and 65 years and older); education groups (less than high school graduate vs. some college and college graduate; high school graduate vs. some college and college graduate; some college vs. college graduate); and BMI groups (underweight/normal vs. obese; overweight vs. obese). Significant within-group findings for those reporting 2 or more days per week of muscle strengthening, including all seven major muscle groups, were seen among age groups (25–34 years vs. 45–64 years and 65 years and older; 35–44 years vs. 45–64 years and 65 years and older); education groups (less than high school graduate vs. some college and college graduate; high school graduate vs. college graduate; some college vs. college graduate); and BMI groups (underweight/normal vs. obese). A significant linear increase was noted among education groups, with respondents who reported lower levels of educational attainment having lower levels of participation (both without and with the requirement of all seven major muscle groups) compared with respondents who reported higher levels of educational attainment. A significant linear decrease was noted among each BMI group, with those classified as underweight/normal reporting higher levels of participation (both without and with the requirement of all seven major muscle groups), compared with those classified as obese.

Respondents were additionally categorized by using 2008 Guidelines standards for aerobic physical activity (see Table 2). The overall prevalence of meeting both the aerobic standards and the 2008 Guidelines standards for muscle strengthening was 5.5% (95% CI = 4.5–6.6). Significant within-group findings for those meeting both muscle-strengthening standards and aerobic standards were seen among age groups (25–34 years vs. 65 years and older; 35–44 years vs. 65 years and older); education groups (less than high school graduate vs. some college and college graduate; high school graduate vs. some college; some college vs. college graduate); and BMI groups (underweight/normal vs. obese). Similar to the findings already presented, a significant linear increase was noted by education groups, and a significant linear decrease was noted by each BMI group (p < .05). Less than 1% of the population met the muscle-strengthening standards but not the aerobic activity standard. The only significant finding was between White Non-Hispanic (0.4%, 95% CI = 0.2–0.7) and Black Non-Hispanic respondents (0.1%, 95% CI = 0.0–0.5).

Table 3 reports the type and location of musclestrengthening activities by the reported number of days per week. Overall, 31.7% (95% CI = 29.4–34.1) of participants reported muscle-strengthening participation at least 2 days per week (n = 1,238). Among those reporting 2 or more days, 51.1% (95% CI = 46.4–55.8) reported participation 2 to 3 days per week, 36.7% (95% CI = 32.0–41.6) reported 4 to 5 days per week, and 12.2% (95% CI = 9.1–16.2) reported 6 to 7 days per week. Calisthenics (54.6%, 95% CI = 50.0–59.1) and handheld weights (58.3%, 95% CI = 53.7–62.8) were the most commonly reported types of muscle-strengthening activity, regardless of the number of reported days per week of muscle strengthening. The most common locations for muscle strengthening were at home (69.0%, 95% CI = 64.4–73.3) and at for-profit fitness centers (23.1%, 95% CI = 18.8–28.0). The home and for-profit fitness centers continued to be the most common locations for muscle strengthening among those reporting 2 to 3 days and 4 to 5 days per week; however, the home (81.3%, 95% CI = 65.4–90.9) and the outdoors (21.0%, 95% CI = 13.5–31.0) were the most common locations among those reporting 6 to 7 days per week of muscle-strengthening participation.

TABLE 3.

Type and Location of Muscle-Strengthening Activities Among Respondents Reporting More than 2 Days per Week of Muscle-Strengthening Participation—Healthstyles, 2009

| Days per Week of Muscle-Strengthening Participation |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two or More Days (n = 1,238) |

Two to Three Days (n = 665) |

Four to Five Days (n = 426) |

Six to Seven Days (n = 147) |

|||||

| Characteristic | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI |

| Type | ||||||||

| Weight machines | 40.1 | 35.5–44.9 | 40.8 | 35.5–46.3 | 41.5 | 32.6–50.9 | 33.1 | 22.2–46.3 |

| Resistance bands | 24.2 | 20.1–28.7 | 21.9 | 17.5–27.1 | 26.3 | 18.8–35.4 | 27.1 | 15.8–42.4 |

| Calisthenics | 54.6 | 50.0–59.1 | 50.9 | 45.5–56.3 | 61.6 | 53.0–69.5 | 49.0 | 34.2–63.9 |

| Handheld or free weights | 58.3 | 53.7–62.8 | 56.4 | 50.9–61.8 | 65.5 | 58.0–72.3 | 44.8 | 31.2–59.2 |

| Yoga or Tai Chi | 16.1 | 12.3–20.7 | 14.4 | 11.1–18.5 | 14.5 | 8.9–22.9 | 27.6 | 12.3–50.9 |

| Location | ||||||||

| Free community center | 5.6 | 3.7–8.4 | 3.6 | 2.3–5.6 | 5.7 | 2.8–11.0 | 13.7 | 5.3–31.2 |

| Nonprofit community center | 6.7 | 5.0–9.1 | 6.6 | 4.9–9.0 | 5.1 | 3.3–7.8 | 12.1 | 4.1–30.4 |

| For-profit community center | 23.1 | 18.8–28.0 | 24.3 | 19.7–29.6 | 23.2 | 15.0–34.1 | 17.8 | 8.3–33.9 |

| Worksite | 13.8 | 10.7–17.5 | 11.7 | 8.8–15.3 | 16.1 | 10.4–24.2 | 15.4 | 6.5–32.2 |

| Home | 69.0 | 64.4–73.3 | 64.0 | 58.5–69.1 | 71.9 | 62.7–79.6 | 81.3 | 65.4–90.9 |

| Outdoors | 14.7 | 12.0–18.0 | 11.3 | 8.7–14.7 | 17.3 | 11.8–24.7 | 21.0 | 13.5–31.0 |

Note. N = 1,238. The measures were not mutually exclusive, and more than one response could have been provided for type and location of muscle strengthening. CI = confidence interval.

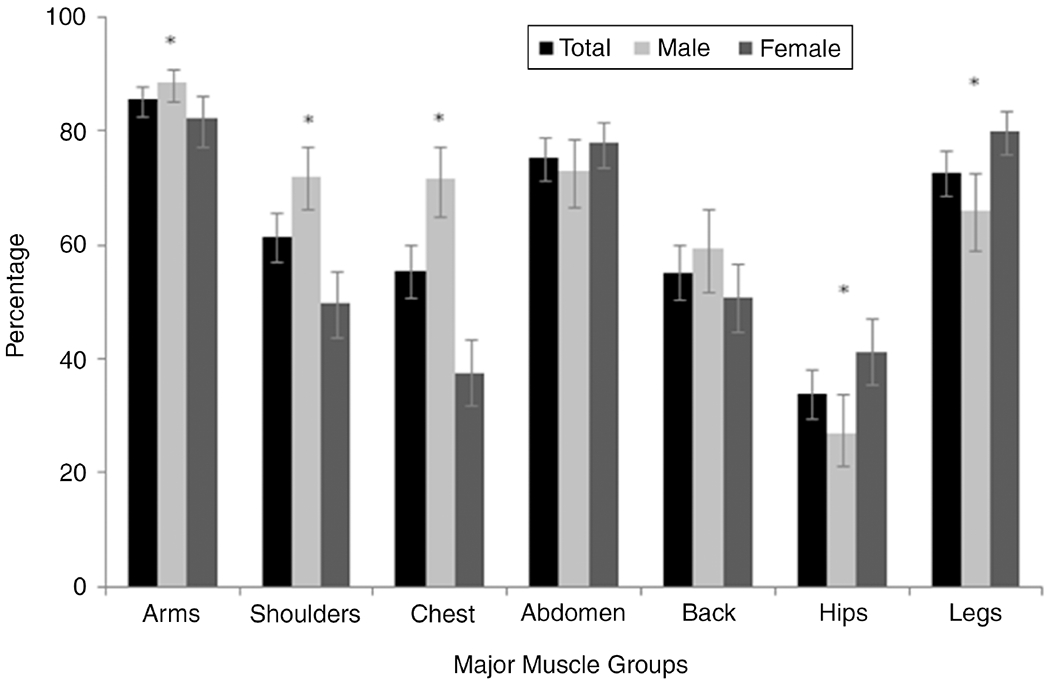

Figure 1 depicts the reported use of the seven major muscle groups during muscle-strengthening activities dining a usual week. Among those reporting 2 or more days per week of muscle strengthening (n = 1,238), the most frequently used muscle groups were the arms (85.4%, 95% CI = 82.5–87.9), abdomen (75.3%, 95% CI = 71.4–78.8), and legs (72.7%, 95% CI = 68.5–76.6). Significant differences (p < .05) between men and women, respectively, were noted among most reported muscle groups, including arms (88.4% [95% CI = 85.2–90.9] vs. 82.2% [95% CI = 77.1–86.3]), shoulders (72.1% [95% CI = 66.2–77.3] vs. 49.6% [95% CI = 43.7–55.5]), chest (71.5% [95% CI = 60.5–77.2] vs. 37.5% [95% CI = 31.9–43.3]), hips (27.0% [95% CI = 21.2–33.8] vs. 41.2% [95% CI = 35.6–47.0]), and legs (66.1% [95% CI = 59.1–72.5] vs. 80.0% [95% CI = 76.0–83.5]).

FIGURE 1.

Percent of adults reporting 2 or more days per week of muscle-strengthening activities by major muscle groups—HealthStyles, 2009. Note. N 1,238 (men, n = 638; women, n = 600); *significant difference between men and women (p < .05).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this was the first publication to fully assess the 2008 Guidelines muscle-strengthening standards, which recommend activities on 2 or more days per week, including all seven major muscle groups. Whereas 31.7% reported muscle strengthening on 2 or more days per week, only 6.0% included all seven major muscle groups during a usual week. Similar patterns were found with demographic characteristics among those meeting previous muscle-strengthening standards and those meeting the 2008 Guidelines standards.

Age- and education-group patterns seen in this study are generally similar to previous reports. In general, increasing age and lower levels of education have been associated with lower levels of muscle-strengthening participation (Carlson, Fulton, Schoenborn, & Loustalot, 2010; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2006; Chevan, 2008). Historically, men have reported higher levels of muscle-strengthening participation (CDC, 2006); however, significant differences were not found in this study. Racial and ethnic-group differences have been reported in previous literature. Carlson and colleagues (2010), using a nationally representative sample, reported those of Hispanic ethnicity had the lowest reported muscle-strengthening participation among racial and ethnic groups. However, no significant differences were found in this study, possibly because of the small number of participants meeting guidelines or the questions used to assess muscle-strengthening participation. Those in higher BMI categories reported significantly less muscle-strengthening participation, which is similar to previous assessments (Galuska, Earle, & Fulton, 2002; Kruger, Ham, & Prohaska, 2009). Most respondents meeting the overall 2008 Guidelines for muscle strengthening were categorized as aerobically active. Chevan reported the strongest determinant of muscle strengthening was concurrent participation in aerobic physical activity. This pattern was seen in this study and was evidenced by the small number of respondents being categorized as not aerobically active yet meeting 2008 Guidelines standards for muscle strengthening.

The type and location of muscle-strengthening activities are infrequently reported in the literature. Knowledge about the most common types and locations of muscle-strengthening participation can guide evidenced-based recommendations and public health interventions (Dunton, Berrigan, Ballard-Barbash, Graubard, & Atienza, 2008; King et al., 1992). In this study, the most common types of muscle-strengthening activities by reported days per week were handheld or free weights, calisthenics, and weight machines. Well more than half of those participating in muscle strengthening reported the home as the primary location, and they reported for-profit community fitness centers, the worksite, and the outdoors less frequently. Dunton and colleagues, using a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults, reported the home, outdoors, and gym or health clubs as commonly reported locations for sports and exercise bouts, similar to findings in this study. In addition to type and location of muscle strengthening, participants reported the muscle groups they used during muscle-strengthening activities. The most frequently reported muscle groups were the arms, abdomen, and legs. Significant sex-group differences were found, with men reporting more frequent inclusion of the upper-body muscle groups (i.e., arms, shoulders, chest) and women reporting more frequent inclusion of the lower-body muscle groups (i.e., hips, legs).

Knowledge of variations among demographic characteristics, in addition to the identification of location and type of muscle-strengthening activities, can be used by state and local partners in adapting physical activity campaigns or interventions within communities. For example, the Guide to Community Preventive Services recommends informational approaches, behavioral and social approaches, and environmental and policy approaches to increasing physical activity (CDC, 2001; Heath et al., 2006). When communities are individualizing these approaches to their members, there are opportunities to encourage increased muscle-strengthening participation (e.g., home-based muscle-strengthening programs with social support networks promoted through heath centers).

The measures used to assess muscle-strengthening participation in this study were based on national surveillance system questions and expert opinion. The muscle-strengthening questions assessed frequency and number of muscle groups, as recommended in the 2008 Guidelines; however, the questions did not assess the intensity level of muscle strengthening and were self-reported. The 2008 Guidelines recommend participation in muscle strengthening of moderate to high intensity, and the lack of specificity regarding intensity level in the HealthStyles questions feasibly resulted in the inclusion of low-intensity activities and potential overestimations.

In addition, physical activity was assessed by self-report. Estimates of muscle-strengthening participation (2 or more days per week) were higher in this study (31.7%, 95% CI = 29.4–34.1) compared with other national estimates (21.9%, 95% CI = 21.2–22.7; Carlson et al., 2010), and aerobic physical activity estimates (57.6%, 95% CI = 55.4–59.9) were comparable to recent national estimates (64.5%, 95% CI = 64.2–64.9; CDC, 2008). Variations in estimates may be due to differences in questionnaires or survey methodology (Carlson, Densmore, Fulton, Yore, & Kohl, 2009). Assessing aerobic physical activity through self-report may be influenced by reporting bias (Sallis & Saelens, 2000), and self-reported estimates are generally higher compared with estimates using objectively measured aerobic activity (Troiano et al., 2008). However, current 2008 Guidelines standards are largely based on research studies assessing self-reported physical activity and health outcomes (DHHS, 2008b), and comparing objective physical activity findings to current standards may result in an underestimation of physical activity. The majority of previous research has focused on aerobic physical activity; however, similar observations are possible with self-reported versus objective assessment of muscle-strengthening participation. Future studies are needed to determine the degree of correlation between self-reported and objective measures.

Limitations were identified in our study. First, data from consumer mail-panel surveys has the potential for sample-selection bias. However, previous research that has compared results between random-digit dial and panel approaches has found a general equivalence between results, suggesting that findings from panel studies are as acceptable as those using respondents selected randomly for telephone surveys (Pollard, 2002). Second, participation among those contacted was 49.4% for the ConsumerStyles survey and 65.0% for the HealthStyles survey, and lower levels of participation may affect survey data quality (Fahimi, Link, Schwartz, & Mokdad, 2008; Galea & Tracy, 2007). Differences were noted among the unweighted and weighted sample. Weighting the data to the U.S. census population projections for 2009 attempted to make the estimates more representative of the demographic distribution of the U.S. population. Lastly, the surveys were conducted in English and require adequate reading comprehension. Lower levels of participation in physical activity have been noted among minority populations, although not specifically non-English-speaking, and those of lower socioeconomic status (Carlson et al., 2010). This has potentially resulted in an overestimation of physical activity participation among these groups.

CONCLUSIONS

The data suggest that about one third of U.S. adults reported participation in muscle-strengthening activities on 2 or more days per week, and only about 1 out of 20 U.S. adults participate in activities to meet the full 2008 Guidelines standards for muscle strengthening. Yet there is great diversity in how muscle-strengthening activities are performed, in terms of days per week, type of exercise, location, and muscle groups. The most consistent finding is that people prefer to perform the activities at home versus having to travel to the worksite or fitness center. This situation is analogous to the preference for home or outdoor aerobic activity, compared with physical activity in a fitness center (Ashworth, Chad, Harrison, Reeder, & Marshall, 2005; Dunton et al., 2008). The promotion of muscle-strengthening activities should not be limited to a specific domain (i.e., fitness centers), but should be promoted in every available setting, as aerobic physical activity has been. To guide public health interventions and communication campaigns, future public health efforts to increase muscle-strengthening participation should use the variations among demographic characteristics and the most frequently reported type and location of muscle-strengthening activities outlined in this study.

WHAT DOES THIS ARTICLE ADD?

Participation in muscle-strengthening activities provides significant health benefits, independent of aerobic physical activity, yet few U.S. adults participate in muscle-strengthening activities. Muscle strengthening may include calisthenics, resistance bands, weight machines, or free weights, and it can be performed in a variety of locations (e.g., the home, fitness facilities, outdoors). The 2008 Guidelines recommended that adults participate in moderate- to high-intensity muscle-strengthening activities on 2 or more days per week and that these activities include the use of all seven major muscle groups (i.e., legs, hips, back, chest, abdomen, shoulders, and arms). Findings from this study indicate that only 6% of those surveyed participated in muscle-strengthening activities, as defined by the 2008 Guidelines. Among those reporting participation, the home was the most common location (69%). The promotion of muscle-strengthening activities should not be limited to a specific domain (i.e., fitness centers), but should be promoted in every available setting, as aerobic physical activity has been. To guide public health interventions and communication campaigns, future public health efforts to increase muscle-strengthening participation should use the variations among demographic characteristics and the most frequently reported type and location of muscle-strengthening activities outlined in this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Contributor Information

Fleetwood Loustalot, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Susan A. Carlson, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Judy Kruger, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

David M. Buchner, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Janet E. Fulton, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

REFERENCES

- Ashworth NL, Chad KE, Harrison EL, Reeder BA, & Marshall SC (2005). Home versus center based physical activity programs in older adults. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews, 1, CD004017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SA, Densmore D, Fulton JE, Yore MM, & Kohl HW (2009). Differences in physical activity prevalence and trends from 3 U.S. surveillance systems: NHIS, NHANES, BRFSS. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 3(Suppl. 1), S18–S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Schoenborn CA, & Loustalot F (2010). Trend and prevalence estimates based on the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 39, 305–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2001). Increasing physical activity: A report on recommendations of the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 50(RR–18), 1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2006). Trends in strength training—United States, 1998–2004. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 55, 769–772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2008). Prevalence of self-reported physically active adults—United States, 2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 57, 1297–1300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevan J (2008). Demographic determinants of participation in strength training activities among US adults. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 22, 553–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church TS, Blair SN, Cocreham S, Johannsen N, Johnson W, Kramer K, & … Earnest CP (2010). Effects of aerobic and resistance training on hemoglobin A(1c) levels in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 304, 2253–2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunton GF, Berrigan D, Ballard-Barbash R, Graubard BI, & Atienza AA (2008). Social and physical environments of sports and exercise reported among adults in the American Time Use Survey. Preventive Medicine, 47, 519–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahimi M, Link M, Schwartz D, & Mokdad A (2008). Tracking chronic disease and risk behavior prevalence as survey participation declines: Statistics from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System and other national surveys. Preventing Chronic Disease, 5(3), Retrieved January 15, 2011, from http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2008/jul/07_0097.htm [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, & Tracy M (2007). Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Annals of Epidemiology, 17, 643–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galuska DA, Earle D, & Fulton JE (2002). The epidemiology of US adults who regularly engage in resistance training. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 73, 330–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath GW, Brownson RC, Kruger J, Miles R, Powell KE, & Ramsey LT (2006). The effectiveness of urban design and land use and transport policies and practices to increase physical activity: A systematic review. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 3(Suppl. 1), S55–S76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AW, Lee DC, Sui XM, Morrow JR, Church TS, Maslow AL, & Blair SN (2010). Muscular strength is inversely related to prevalence and incidence of obesity in adult men. Obesity, 18, 1988–1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurca R, Lamonte MJ, Barlow CE, Lampert JB, Church TS, & Blair SN (2005). Association of muscular strength with incidence of metabolic syndrome in men. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 37, 1849–1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Blair SN, Bild DE, Dishman RK, Dubbert PM, Marcus BH, & … Yeager KK (1992). Determinants of physical activity and interventions in adults. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 24, S221–S236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger J, Ham SA, & Prohaska TR (2009). Behavioral risk factors associated with overweight and obesity among older adults: The 2005 National Health Interview Survey. Preventing Chronic Disease, 6 (1). Retrieved January 15, 2011, from http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2009/jan/07_0183.htm [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1998). Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: The evidence report. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard WE (2002). Use of consumer panel survey data for public health communication planning: An evaluation of survey results. 2002 American Statistical Association Proceedings, 2720–2724. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard WE (2007). Evaluation of consumer panel survey data for public health communication planning: An analysis of annual survey data from 1995–2006. 2007 American Statistical Association Proceedings, 1528–1533. [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, & Saelens BE (2000). Assessment of physical activity by self-report: Status, limitations, and future directions. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 71(Suppl. 2), S1–S14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUDAAN (Version 9.0) [Computer software]. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International. [Google Scholar]

- Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, & McDowell M (2008). Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 40, 181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2000). Objectives 22-2 and 22-3. In Healthy People 2010 (pp. 22-9–22-13). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2008a). 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Hyattsville, MD: Author. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2008b). Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee report, 2008. Hyattsville, MD: Author. [Google Scholar]