Vaccination against COVID-19 increased immunity in the population, which reduced viral transmission and protected against severe disease. However, continuous emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants required the implementation of bivalent boosters including the wild-type (D614G) and omicron (BA.5) spike. Improved effectiveness of the bivalent booster versus monovalent booster against omicron subvariants has been reported;1 however, few differences in the immune response have been detected.2, 3

We investigated whether a bivalent COVID-19 booster vaccine that included wild-type spike and BA.5 spike induced detectable BA.5-specific antibody responses in serum. 16 serum samples collected at mean 31 days (SD 63 [range 0–260]) before and a mean 16 days (8 [6–31]) after receiving the bivalent booster were tested for antibody binding and avidity to the receptor binding domain (RBD) of wild-type and BA.5 SARS-CoV-2. Neutralisation of wild-type and BA.5 viruses was determined. Omicron-specific antibodies were measured by depletion of wild-type RBD reactive antibodies and assessment of depleted serum samples against BA.5 RBD.

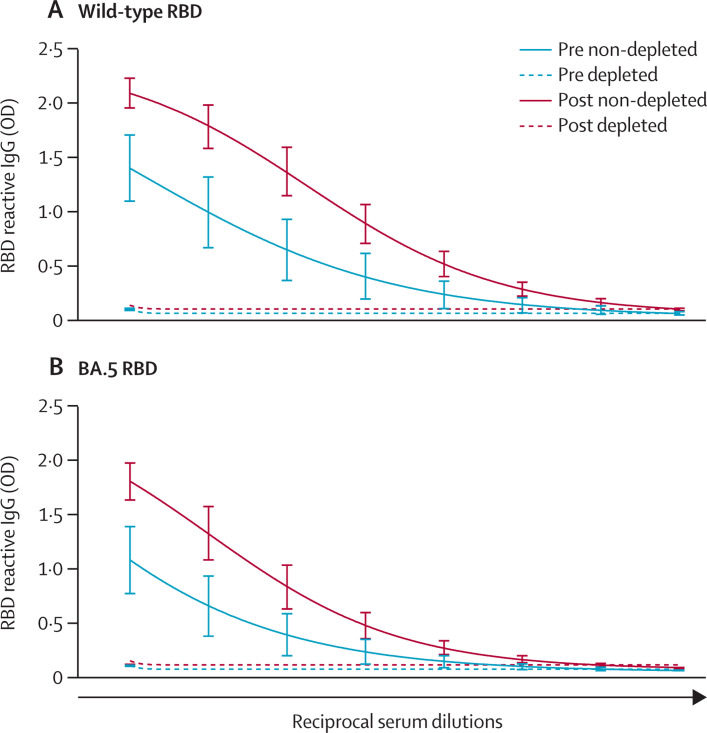

A substantial increase in antibody binding to wild-type and BA.5 RBD as well as in neutralisation of wild-type and BA.5 viruses was seen in serum samples after receiving the bivalent booster (figure , appendix p 6). There were substantial differences in binding of post-booster serum samples between wild-type and BA.5 RBDs; however, differences in neutralisation were not significant. Pre-booster and post-booster RBD antibody avidity was lower against BA.5 RBD than wild-type RBD, which prompted us to look for BA.5 specific antibodies. Wild-type RBD depleted serum samples had undetectable reactivity to wild-type RBD—as expected—and to BA.5 RBD, suggesting that a single exposure to BA.5 antigens by the administration of bivalent vaccine boosters does not elicit robust concentrations of BA.5 specific serum antibodies.

Figure.

Serum samples depleted of wild-type RBD have no reactivity to BA.5 RBD

Reactivity of pre-bivalent booster vaccination serum samples is shown in blue and reactivity of post-bivalent booster vaccination serum samples is shown in red for both (A) wild-type RBD protein and (B) BA.5 RBD protein. Samples were depleted of wild-type RBD antibodies and reactivity was measured to (A) wild-type RBD (to confirm complete depletion) and to (B) BA.5 RBD (to determine if omicron-specific antibodies were present). Samples depleted of wild-type RBD antibodies are shown as dashed lines and samples not depleted of wild-type RBD antibodies are shown as continuous lines. OD is shown on the y axis and reciprocal serum dilutions (100–12 800 with two-fold dilution series) are shown on the x axis. The sample size was 16. RBD=receptor binding domain. OD=optical density.

Reduced sensitivity of antibody tests based on wild-type viral antigens was detected in previously SARS-CoV-2 antigen naive individuals after omicron infection.4 However, most of the global population has been infected with ancestral strains or exposed to wild-type antigens through vaccination, hence our results are relevant for the current immune status of the population worldwide. Moreover, our data align with results from April, 2023, which indicate that a monovalent booster with BA.1 vaccine elicits robust spike-specific germinal centre B-cell responses but very low numbers of de-novo B cells targeting variant-specific epitopes.5 Whether further exposures to omicron antigens will boost these responses to make them detectable in serum remains to be explored. Importantly, it is probable that cross-reactive antibodies towards omicron-antigens contribute to protection.

Acknowledgments

FK and VS are named on SARS-CoV-2-related patent applications as co-inventors (US application serial numbers 17/913 783 and 17/922 777). FK has consulted for Merck and Pfizer, and is currently consulting for Pfizer, Seqirus, 3rd Rock Ventures, and Avimex. FK is a co-founder and scientific advisory board member of CastleVax. FK's laboratory is also currently collaborating with Pfizer on animal models for SARS-CoV-2.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Lin DY, Xu Y, Gu Y, et al. Effectiveness of bivalent boosters against severe omicron infection. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:764–766. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2215471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurhade C, Zou J, Xia H, et al. Low neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 omicron BA.2.75.2, BQ.1.1 and XBB.1 by parental mRNA vaccine or a BA.5 bivalent booster. Nat Med. 2023;29:344–347. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Q, Bowen A, Valdez R, et al. Antibody response to omicron BA.4-BA.5 bivalent booster. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:567–569. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2213907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rössler A, Knabl L, Raschbichler LM, et al. Reduced sensitivity of antibody tests after omicron infection. Lancet Microbe. 2023;4:e10–e11. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(22)00222-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alsoussi WB, Malladi SK, Zhou JQ, et al. SARS-CoV-2 omicron boosting induces de novo B cell response in humans. Nature. 2023 doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06025-4. published online April 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.