Abstract

As the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic progresses to an endemic phase, a greater number of patients with a history of COVID-19 will undergo surgery. Major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACE) are the primary contributors to postoperative morbidity and mortality; however, studies assessing the relationship between a previous severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and postoperative MACE outcomes are limited. Here, we analyzed retrospective data from 457,804 patients within the N3C Data Enclave, the largest national, multi-institutional data set on COVID-19 in the United States. However, 7.4% of patients had a history of COVID-19 before surgery. When comorbidities, age, race, and risk of surgery were controlled, patients with preoperative COVID-19 had an increased risk for 30-day postoperative MACE. MACE risk was influenced by an interplay between COVID-19 disease severity and time between surgery and infection; in those with mild disease, MACE risk was not increased even among those undergoing surgery within 4 wk following infection. In those with moderate disease, risk for postoperative MACE was mitigated 8 wk after infection, whereas patients with severe disease continued to have elevated postoperative MACE risk even after waiting for 8 wk. Being fully vaccinated decreased the risk for postoperative MACE in both patients with no history of COVID-19 and in those with breakthrough COVID-19 infection. Together, our results suggest that a thorough assessment of the severity, vaccination status, and timing of SARS-CoV-2 infection must be a mandatory part of perioperative stratification.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY With an increasing proportion of patients undergoing surgery with a prior history of COVID-19, it is crucial to understand the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on postoperative cardiovascular/cerebrovascular risk. Our work assesses a large, national, multi-institutional cohort of patients to highlight that COVID-19 infection increases risk for postoperative major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACE). MACE risk is influenced by an interplay between disease severity and time between infection and surgery, and full vaccination reduces the risk for 30-day postoperative MACE. These results highlight the importance of stratifying time-to-surgery guidelines based on disease severity.

Keywords: COVID-19 severity, COVID-19 vaccination, postoperative MACE, preoperative COVID-19, time to surgery after COVID-19

INTRODUCTION

It is estimated that 15%–20% of patients with prior severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections will require surgery (1), and these patients are at elevated risk for developing postoperative complications and mortality (2–4). Most prior research has focused on postoperative pulmonary, systemic, or thrombosis/embolism-related complications; however, perioperative major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACE) are the leading contributors to postoperative mortality and morbidity in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery (5, 6).

SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with an increased risk for numerous incident cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (7, 8), and studies have reported that undergoing any surgery, including noncardiac procedures, can have short-term detrimental effects on the vascular system (9–11). Together, it is possible that in those with preoperative coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the compounded stress from infection and surgery may increase risk for postoperative MACE. There is a gap in the available literature assessing the association between a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection and postoperative cardiovascular/cerebrovascular outcomes. The few existing studies either are limited in the type of cardiovascular disease (CVD) assessed (largely arrhythmias or thromboses), have small sample sizes, or are primarily focused on composite outcomes involving other organ systems (12–14).

Prior studies have also shown the timing of COVID-19 relative to surgery influences the risk of adverse postoperative adverse events (4, 15), and the severity of COVID-19 symptomology influences postoperative outcomes (16). In addition, as the pandemic has progressed and shifted to an endemic state, more tools are now available to mitigate the risks associated with COVID-19. These include vaccination and therapeutic options that can decrease the severity of an acute infection (17). The interplay between time to surgery, disease severity, vaccination, and postoperative MACE is unclear yet is crucial to understand given implications for treatment planning, patient counseling, and postoperative risk stratification. The primary objective of this study was to assess whether preoperative SARS-CoV-2 infection influences risk for postoperative MACE. Secondary objectives included whether vaccination before surgery/infection, severity of disease, and time between infection and surgery influence risk for postoperative MACE.

METHODS

Study Cohort and Design

Patients (median age, 62 yr; Q1–Q3, 49–71 yr) who underwent elective, noncardiac inpatient surgical procedures (Supplemental Table S1; all Supplemental material is available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DFSGWU) between January 2020 and November 2022 were identified from within the United States National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C; 18) Data Enclave. Surgical procedures were selected based on prior literature examining the association between prior COVID-19 and surgical outcomes. For patients with multiple surgical procedures, only the first was included. The N3C Data Enclave is the largest multi-institutional, federally secured data set based on electronic health records that is available in the United States for studying the influence of COVID-19 on patient outcomes. The primary data sources contributing to N3C Data Enclave include OMOP, PCORnet, TriNetX, and ACT (18). All participating institutions are included in the acknowledgments. This study was approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board (PRO00042159).

Patients were characterized as being positive for COVID-19 based on positive laboratory measurement (PCR or antigen) or a positive COVID-19 diagnosis (ICD10-CM code U07.1) before undergoing surgery. Infection severity was determined based on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Clinical Progression Scale (19). Using the N3C Knowledge Store’s Critical Visits data set, mild severity was defined as those who only had outpatient visits for COVID-19 (WHO severity 1–3). Moderate severity was defined as those who required hospitalization without ventilatory support (WHO severity 4–6). Severe disease was defined as requiring hospitalization with invasive ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO; WHO severity 7–9; 20).

Full vaccination status was defined as having at least two vaccine doses of mRNA vaccine or one-dose of viral vector vaccine 14 days or more before surgery and before SARS-CoV-2 infection. Comorbid diseases and noncardiac surgical procedures were identified using standard SNOMED procedure codes from the Observational Health Data Science and Informatics' (OHDSI) ATLAS tool (Supplemental Tables S1 and S2). Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was acquired using N3C’s Logic Liaison Summary Fact Table (21). Patients who underwent percutaneous procedures, endoscopic or natural orifice procedures, minimally invasive diagnostic procedures, cardiac procedures, or transplants were excluded.

The primary outcome of this study was occurrence of MACE (composite that included: cerebrovascular complication, dysrhythmias, inflammatory heart disease, ischemic heart disease, heart failure/cardiac arrest/cardiac shock, and thrombotic complication) within 30 days of surgery (Supplemental Table S3; 7). Multivariable logistic regression models were developed to assess the risk of adverse 30-day postoperative cardiovascular outcomes (both composite and individual categories) in those with or without preoperative SARS-CoV-2 infection. There was a low frequency of missing data (Supplemental Table S4).

Additional secondary analyses included logistic regression models assessing the association between postoperative MACE and vaccination status, time from COVID-19 infection to surgery, and COVID-19 severity. Covariates included in the analysis were relative surgical risk, comorbidity index, smoking status, age, sex, and race. The potential collinearity between input features was measured using variance inflation factor (VIF) across all models. VIF was <2 for all measured covariates.

χ2 analysis was used to assess differences between groups. All statistical analyses were conducted within the N3C Data Enclave using the following R packages: tidyverse, ggplot2, gtsummary, splines, and broom. Prism GraphPad Version 9.5.0 was used for making all forest plots.

RESULTS

A total of 457,804 patients were included in the study, and 33,861 (7.4%) had a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection before surgery (Table 1). There were notable differences between the groups; specifically, a greater proportion of patients with prior COVID-19 had preexisting cardiovascular comorbidities including heart failure (6.8% in those with prior COVID-19 vs. 3.4% in those without prior COVID-19), coronary artery disease (10% vs. 6.0%), diabetes (17% vs. 9.3%), hypertension (37% vs. 24%), and obesity (24% vs. 13%; P < 0.001, all).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and postoperative cardiovascular outcomes

| Covid-19 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | No Hx | Hx | P Value |

| Patients, n (%) | 423,943 | 33,861 | |

| Age, yr | |||

| Median (quartiles 1–3) | 62 (50, 72) | 59 (46, 69) | <0.001 |

| Ranges, n (%) | |||

| 18–29 | 18,223 (4.5) | 1,729 (5.3) | <0.001 |

| 30–49 | 73,978 (18) | 7,349 (23) | |

| 50–64 | 130,343 (32) | 11,112 (34) | |

| 65+ | 183,163 (45) | 12,330 (38) | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.023 | ||

| Female | 248,514 (59) | 19,930 (≈59)* | |

| Male | 175,093 (41) | 13,917 (≈41)* | |

| Missing or unknown | 336 (<0.1) | ≤20 | |

| Race and ethnicity, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Hispanic | 27,366 (6.5) | 3,238 (9.6) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 55,109 (13) | 4,692 (14) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 309,224 (73) | 23,053 (68) | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 9,731 (2.3) | 704 (2.1) | |

| Other or unknown | 22,513 (5.3) | 2,174 (6.4) | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Nonsmoker | 370,858 (87) | 30,350 (90) | |

| Current or former smoker | 53,085 (13) | 3,511 (10) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 92,560 (22) | 7,230 (21) | |

| 1 | 51,856 (12) | 4,271 (13) | |

| 2 | 76,983 (18) | 5,940 (18) | |

| 3 | 46,588 (11) | 3,725 (11) | |

| 4+ | 155,734 (37) | 12,695 (37) | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Chronic kidney disease | 20,536 (4.8) | 3,129 (9.2) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 14,533 (3.4) | 2,315 (6.8) | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 20,442 (4.8) | 2,644 (7.8) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 25,398 (6.0) | 3,530 (10) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 40,452 (9.5) | 5,400 (16) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 39,516 (9.3) | 5,818 (17) | <0.001 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 65,364 (15) | 8,679 (26) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 103,129 (24) | 12,654 (37) | <0.001 |

| Liver disease | 6,209 (1.5) | 910 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 54,681 (13) | 7,986 (24) | <0.001 |

| Relative risk of surgery, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Low | 184,282 (43) | 14,047 (41) | |

| Medium | 219,557 (52) | 18,181 (54) | |

| High | 20,104 (4.7) | 1,633 (4.8) | |

| Vaccine status, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Fully | 39,586 (9.3) | 4,338 (13) | |

| Not Fully | 384,357 (91) | 29,523 (87) | |

| Postoperative complications, n (%) | |||

| Mortality | 3,417 (0.8) | 584 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| Composite cardiovascular event | 24,997 (5.9) | 2,177 (6.4) | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular complications, n (%) | |||

| Acute stroke | 244 (<0.1) | ≤20 | 0.39 |

| Transient cerebral ischemia | 1,022 (0.2) | 99 (0.3) | 0.075 |

| Dysrhythmia, n (%) | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 6,563 (1.5) | 393 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| Ventricular arrhythmia | 397 (<0.1) | 44 (0.1) | 0.048 |

| Atrial flutter | 2,889 (0.7) | 226 (0.7) | 0.79 |

| Inflammatory heart disease, n (%) | |||

| Carditis | 951 (0.2) | 94 (0.3) | 0.055 |

| Ischemic heart disease | |||

| Acute ischemic heart disease | 3,206 (0.8) | 287 (0.8) | 0.068 |

| Myocardial infarction | 2,282 (0.5) | 217 (0.6) | 0.015 |

| Other cardiac disorder, n (%) | |||

| Acute heart failure | 2,808 (0.7) | 237 (0.7) | 0.43 |

| Cardiac arrest | 1,509 (0.4) | 163 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 772 (0.2) | 95 (0.3) | <0.001 |

| Thrombotic disorders, n (%) | |||

| Pulmonary embolism | 5,235 (1.2) | 517 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 5,262 (1.2) | 492 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| Superficial vein thrombosis | 1,712 (0.4) | 159 (0.5) | 0.075 |

Values are n (%), except where indicated as medians (quartiles 1–3, Q1–Q3); n, number of patients. *To comply with N3C policy, counts below 20 are displayed as <20, and additional values were skewed by up to five to render it impossible to back calculate precise counts in the “Missing or unknown” category. Hx, history of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

COVID-19 Infection and Risk for Postoperative Cardiovascular Events

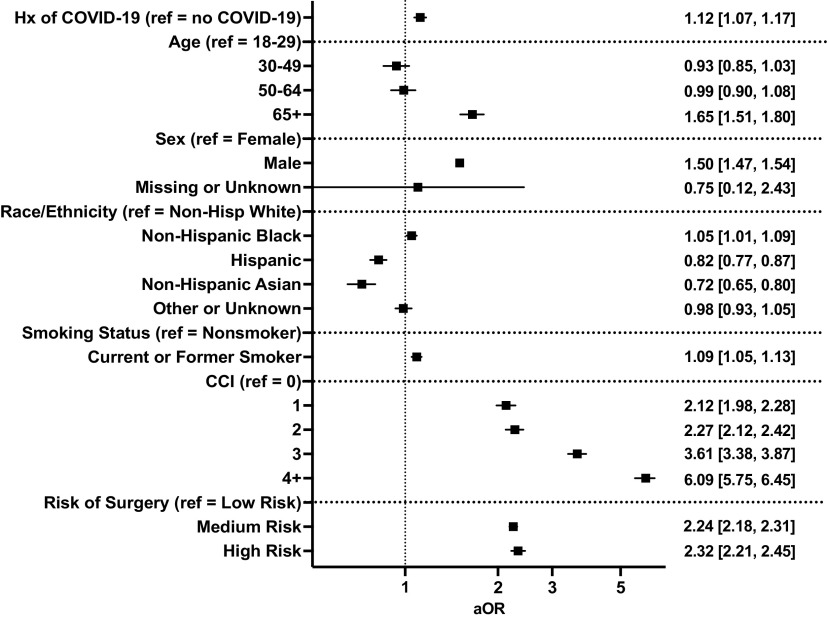

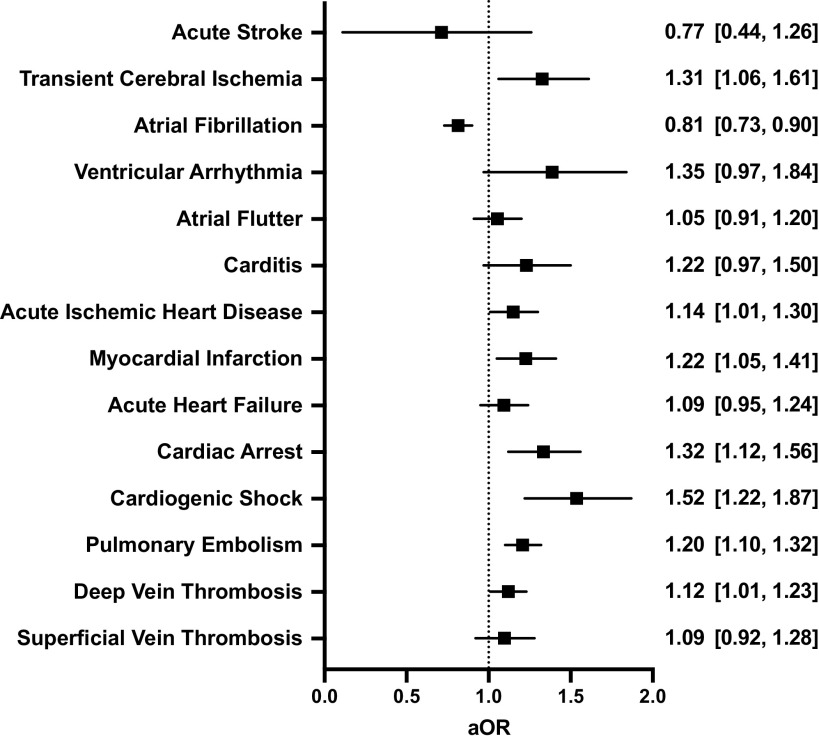

Postoperatively, incidence of composite MACE was greater among patients with COVID-19 history (6.4% vs. 5.9%, P < 0.001; Table 1). Following adjustment for patient demographics, comorbidity, and risk of surgery, preoperative COVID-19 was associated with increased odds of 30-day postoperative composite MACE [adjusted odds ratio (aOR), 95% CI: 1.12, 1.07–1.17, P < 0.001, Fig. 1]. Specifically, patients with preoperative COVID-19 were at increased risk for 30-day postoperative transient cerebral ischemia (aOR, 95% CI: 1.31, 1.06–1.61), acute ischemic heart disease (aOR, 95% CI: 1.14, 1.01–1.30), myocardial infarction (aOR, 95% CI: 1.22, 1.05–1.41), cardiac arrest (aOR, 95% CI: 1.31, 1.12–1.56), cardiogenic shock (aOR, 95% CI: 1.52, 1.22–1.87), and pulmonary embolism (aOR, 95% CI: 1.20, 1.10–1.32, Fig. 2). Patients with preoperative COVID-19 were at decreased risk for postoperative atrial fibrillation (aOR, 95% CI: 0.81, 0.73–0.90). Notably, the association between postoperative MACE and prior COVID-19 infection was not changed when adding a covariate for treating hospitals (aOR, 95% CI: 1.13, 1.07–1.19, P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Impact of preoperative coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on risk of adverse postoperative 30-day composite major adverse cardiovascular events. Graphs show adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2.

Impact of preoperative coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on the risk of specific postoperative cardiovascular events. All models were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, smoking status, comorbidity score, and relative risk of surgery. Graphs show adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals.

Disease Severity and Risk for Postoperative MACE

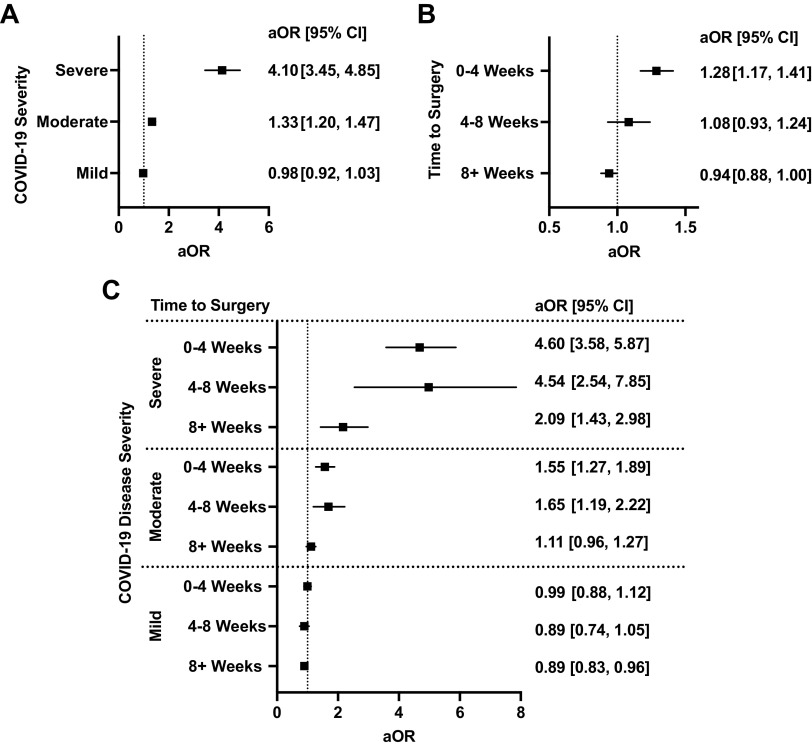

Patients were stratified based on the severity of their SARS-CoV-2 infection before surgery: 27,779 (82.0%) had mild infections, 4,737 (13.9%) had moderate infections, and 784 (2.3%) had severe infections (Supplemental Table S5). The incidence of compositive cardiovascular events was 5.3% among those with mild disease, 9.8% among those with moderate disease, and 27% among those severe disease, as compared with 5.9% among those without a history of preoperative COVID-19 (P < 0.0001). After adjustment for comorbidities, patient demographics, and risk of surgery, patients with moderate (aOR, 95% CI: 1.33, 1.20–1.47, P < 0.001) and severe disease (aOR, 95% CI: 4.10, 3.45-1.47), but not mild disease (aOR, 95% CI: 0.98, 0.92–1.03), had a significantly higher risk for postoperative MACE compared with those without a history of COVID-19 (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

A: impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection severity and surgery on odds of 30-day major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACE). B: impact of time between COVID-19 infection and surgery on odds of 30-day MACE. C: interplay between timing of surgery following COVID-19 infection and severity of infection on odds of 30-day MACE. All models were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, smoking status, comorbidity score, and relative risk of surgery. Graphs show adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals.

Timing between COVID-19 Infection and Surgery and Risk for Postoperative MACE

Patients were stratified based on the timing between SARS-CoV-2 infection and surgery: 7,018 (20.7%) of patients waited 0–4 wk, 3,499 (10.3%) waited 4–8 wk, and 22,179 (65.5%) waited 8+ wk between infection diagnosis and surgery (Supplemental Table S6). The incidence of compositive cardiovascular events was 7.5%, 6.1%, and 5.5% for each of the three subgroups compared with 5.9% in patients without preoperative COVID-19 (P < 0.001). After adjustment for comorbidities, patient demographics, and risk of surgery, only those undergoing surgery within 0–4 wk of having COVID-19 had increased risk for postoperative MACE (aOR, 95% CI: 1.28, 1.17–1.41, Fig. 3B). No significant association with postoperative MACE risk was seen in those who underwent surgery after 4 wk from the time of COVID-19 diagnosis.

Interplay between COVID-19 Severity and Timing between Infection and Surgery

The influence of time between infection and surgery on postoperative MACE among patients with mild, moderate, and severe disease was assessed. Among patients with mild disease, risk for postoperative MACE was not increased even among those undergoing surgery within 4 wk of infection (0–4 wk aOR, 95% CI: 0.99, 0.88–1.22; Fig. 3C). Among patients with moderate disease, those undergoing surgery up to 8 wk (4–8 wk aOR, 95% CI: 1.65, 1.19–2.22), but not 8+ wk (8+ wk aOR, 95% CI: 1.11, 0.96–1.27), after having COVID-19 had an increased risk for postoperative MACE. Among patients with severe disease, risk for postoperative MACE remained high even among those who underwent surgery 8+ wk following infection (8+ wk aOR, 95% CI: 2.09, 1.43–2.98).

Vaccination Status and Risk for Postoperative MACE

Preoperatively, 13% of those with a history of COVID-19 and 9.3% of those with no history of COVID-19 were fully vaccinated (P < 0.001, Table 1). Among patients with no history of COVID-19, 5.7% of vaccinated patients and 5.9% of nonfully vaccinated patients had postoperative MACE (P = 0.034, Table 2). A lower proportion of vaccinated patients had postoperative atrial fibrillation (1.3% vs. 1.6% in nonfully vaccinated, P < 0.001), myocardial infarction (0.4% vs. 0.6%. P = 0.001), cardiac arrest (0.3% vs. 0.4%, P = 0.012), deep vein thrombosis (1.1% vs. 1.3%, P = 0.041), and superficial vein thrombosis (0.3% vs. 0.4%, P = 0.009).

Table 2.

Adverse 30-day postoperative composite MACE in patients with and without COVID-19 based on vaccination status before COVID-19 (if applicable) or surgery

| Vaccinated, n (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Postoperative Complications | Not Fully | Fully | P Value |

| No Hx of COVID-19 | |||

| n | 384,357 | 39,586 | |

| Mortality | 3,059 (0.8) | 358 (0.9) | 0.023 |

| Composite cardiovascular event | 22,758 (5.9) | 2,239 (5.7) | 0.034 |

| Cerebrovascular complications | |||

| Acute stroke | 227 (<0.1) | ≤20 | 0.24 |

| Transient cerebral ischemia | 910 (0.2) | 112 (0.3) | 0.084 |

| Dysrhythmia | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 6,065 (1.6) | 498 (1.3) | <0.001 |

| Ventricular arrhythmia | 370 (<0.1) | 27 (<0.1) | 0.10 |

| Atrial flutter | 2,566 (0.7) | 323 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Inflammatory heart disease | |||

| Carditis | 880 (0.2) | 71 (0.2) | 0.054 |

| Ischemic heart disease | |||

| Acute ischemic heart disease | 2,949 (0.8) | 257 (0.6) | 0.011 |

| Myocardial infarction | 2,115 (0.6) | 167 (0.4) | 0.001 |

| Other cardiac disorder | |||

| Acute heart failure | 2,541 (0.7) | 267 (0.7) | 0.78 |

| Cardiac arrest | 1,397 (0.4) | 112 (0.3) | 0.012 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 714 (0.2) | 58 (0.1) | 0.093 |

| Thrombotic disorders | |||

| Pulmonary embolism | 4,713 (1.2) | 522 (1.3) | 0.12 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 4,814 (1.3) | 448 (1.1) | 0.041 |

| Superficial vein thrombosis | 1,584 (0.4) | 128 (0.3) | 0.009 |

| Hx of COVID-19 | |||

| n | 29,523 | 4,338 | |

| Mortality | 532 (1.8) | 52 (1.2) | 0.005 |

| Composite cardiovascular event | 1,907 (6.5) | 270 (6.2) | 0.58 |

| Cerebrovascular complications | |||

| Acute stroke | ≤20 | ≤20 | 0.71 |

| Transient cerebral ischemia | 80 (0.3) | ≤20 | 0.080 |

| Dysrhythmia | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 340 (1.2) | 53 (1.2) | 0.74 |

| Ventricular arrhythmia | 38 (0.1) | ≤20 | >0.99 |

| Atrial flutter | 193 (0.7) | 33 (0.8) | 0.48 |

| Inflammatory heart disease | |||

| Carditis | 85 (0.3) | ≤20 | 0.43 |

| Ischemic heart disease | |||

| Acute ischemic heart disease | 255 (0.9) | 32 (0.7) | 0.45 |

| Myocardial infarction | 192 (0.7) | 25 (0.6) | 0.64 |

| Other cardiac disorder | |||

| Acute heart failure | 197 (0.7) | 40 (0.9) | 0.075 |

| Cardiac arrest | 148 (0.5) | ≤20 | 0.21 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 82 (0.3) | ≤20 | 0.92 |

| Thrombotic disorders | |||

| Pulmonary embolism | 449 (1.5) | 68 (1.6) | 0.87 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 444 (1.5) | 48 (1.1) | 0.048 |

| Superficial vein thrombosis | 147 (0.5) | ≤20 | 0.061 |

Values are n (%); n, number of patients. MACE, major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Among patients with a history of COVID-19, 6.2% of vaccinated patients and 6.5% of nonfully vaccinated patients had postoperative MACE (P = 0.58, Table 2). A lower proportion of vaccinated patients had postoperative deep-vein thrombosis (1.1% vs. 1.5%, P = 0.048), and incidence of other postoperative cardiovascular outcomes did not significantly vary between groups.

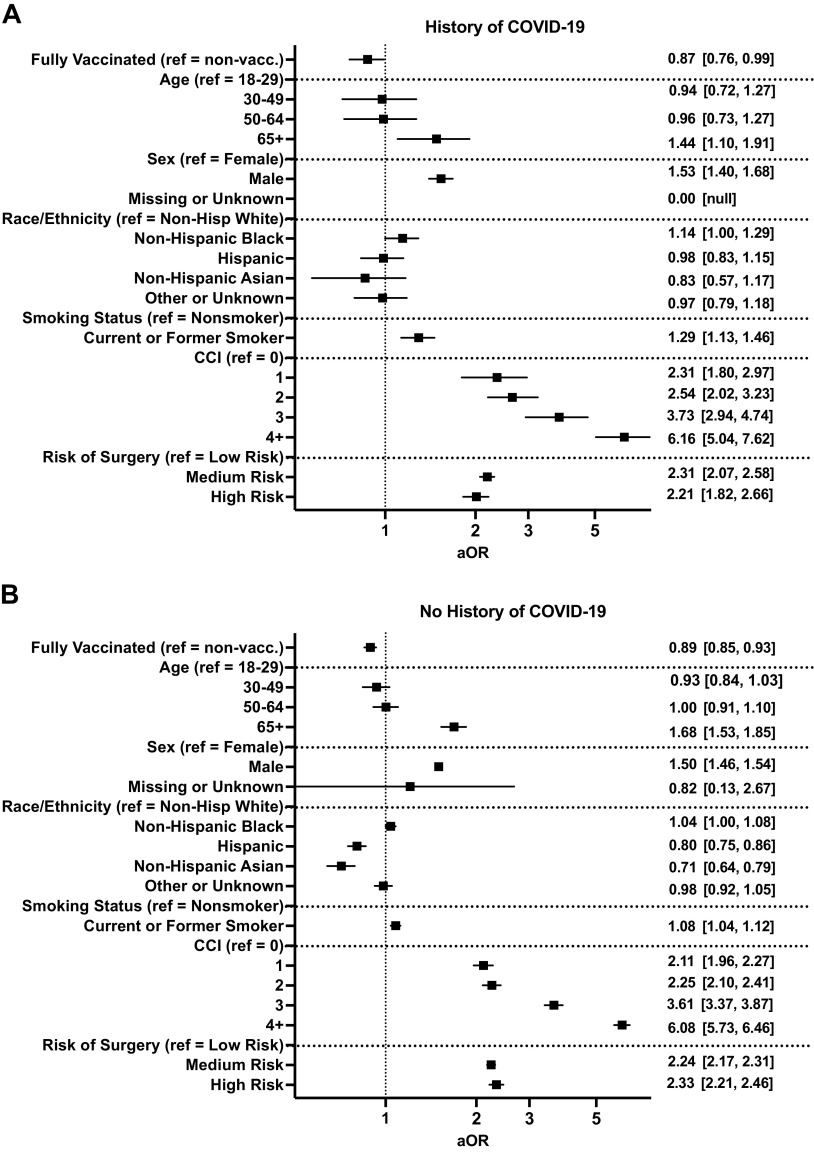

On multivariate regression, vaccination for COVID-19 was associated with a decreased risk for postoperative MACE in both patients who had a history of COVID-19 (aOR, 95% CI: 0.87, 0.76–0.99, P = 0.043, Fig. 4A) and did not have a history of COVID-19 (aOR, 95% CI: 0.89, 0.85–0.93, P < 0.001, Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Impact of full vaccination in patients with (A) and without (B) a history of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on the risk of adverse postoperative 30-day composite major adverse cardiovascular events. Graphs show adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals.

DISCUSSION

With an increasing proportion of patients undergoing surgery with a prior history of COVID-19, it is crucial to understand the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on postoperative cardiovascular risk. The major findings of our study are fourfold: 1) preoperative COVID-19 is associated with an increased risk for composite postoperative MACE; 2) this is influenced by an interplay between severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the timing between infection and surgery; 3) preoperative COVID-19 specifically increases risk for early postoperative cerebral ischemia, acute ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest, cardiogenic shock, and pulmonary embolism but decreases risk for atrial fibrillation; and 4) vaccination decreases risk for postoperative MACE in both patients with no history of COVID-19 and in those with breakthrough COVID-19 infection.

Past studies have reported perioperative MACE in 3%–6% of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery, in line with the 5.9% of our cohort of patients without a history of COVID-19 (5, 22–25). The severity of COVID-19 can vary from mild (including asymptomatic infections) to severe systemic disease that requires hospitalization with respiratory and hemodynamic support. The interplay between severity of infection and surgical outcomes has not been well studied, to date. Our data demonstrate a clear relationship between the severity of COVID-19 and postoperative MACE, as 9.8% and 27% of patients with moderate and severe disease had perioperative MACE compared with 5.3% of those with mild disease. When we controlled for comorbidities, age, race, and risk of surgery, increased risk for postoperative MACE was only seen among those with moderate or severe disease, but not mild disease. These data are in line with Van der Sluijs’ recent study reporting no increase in cardiovascular disease risk 6 mo following mild COVID-19 infection (26). Together, during perioperative risk stratification, a thorough assessment of the degree of COVID-19 infection severity must be elicited and considered.

Currently, consensus guidelines recommend waiting times of 7–8 wk following COVID-19 diagnosis before proceeding with elective surgery (4, 15). In line with these guidelines, our work shows that 7.5% and 6.1% of patients who underwent surgery 0–4 and 4–8 wk after infection had a composite 30-day MACE, respectively. Levels returned to 5.5% for those who underwent surgery after 8+ wk. However, the association between time from infection to surgery and risk for MACE varied greatly based on disease severity. In those with mild disease, MACE risk was not increased even among those undergoing surgery within 4 wk following infection. In those with moderate disease risk for postoperative MACE was mitigated 8 wk after infection, whereas patient with severe disease continued to have elevated postoperative MACE risk even after waiting 8 wk. These results highlight that time to surgery guidelines need to be stratified based on COVID-19 disease severity. Given that 82% of patients presented with mild disease, COVID-19 based surgical delays could be avoided in a large cohort of patients with a prior history of SARS-CoV-2 infection; rather, other factors such as age and comorbidities can be prioritized for perioperative risk stratification among these patients. Further work is necessary to understand the time needed to mitigate postoperative MACE risk in those with severe disease, as well as whether COVID-specific treatments can reduce delays to surgery.

Vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 is well known to lesson infection severity (17) and hospitalization rate, need for mechanical ventilation, and mortality (27). Recent work led by the COVIDSurg Collaborative and GlobalSurg Collaborative reported that nearly 60,000 deaths on average could be prevented per year among patients needing elective surgery through preoperative vaccination (28). Our results are similar and highlight that patients who are fully vaccinated are at significantly reduced risk for postoperative MACE. These results add to a growing body of evidence supporting the prioritization of preoperative vaccination among patients undergoing surgery (28–30).

Given recent concerns regarding the safety of vaccination and potential cardiovascular side effects, we evaluated the risk for postoperative MACE among patients with no history of COVID-19 who were fully vaccinated. Our results show that vaccination decreased postoperative MACE risk in those with no history of preoperative COVID-19 and are in-line with recent work by Prasad et al. (30) using a cohort of 1,255 patients from the Veterans Affairs group nationwide. Their results showed that patients who were vaccinated with at least two doses, but had no preoperative COVID-19, had reduced incidence of postoperative pulmonary complications and hospital length of stay (30). Our prior work also showed that among patients with no history of preoperative COVID-19, preoperative vaccination decreased risk for developing postoperative COVID-19; among the vaccinated patients who had breakthrough postoperative infections, their risk for pulmonary complications, 30-day readmission, and nonfatal adverse events was lower than the notfully vaccinated group (13). Together, preoperative vaccination is not only beneficial for those who develop postoperative COVID-19 but, importantly, does not increase the risk of MACE in those with no history of SARS-CoV-2 infection. It should be noted that this finding could have a component of self-selection bias as vaccinated patients might be different than those who did not get vaccinated, even after adjusting for the covariates included in our analyses.

The mechanism contributing to increased postoperative MACE in patients with preoperative COVID-19 remains a key knowledge gap and has important implications in identifying therapeutic strategies for reducing postoperative MACE. One of the primary mechanisms contributing to CVD following SARS-CoV-2 infection is endothelial dysfunction and vascular inflammation (31, 32), and the stress of surgery is reported to have detrimental effects on the endothelium even among patients undergoing noncardiac surgeries (9–11). In fact, preoperative endothelial dysfunction is associated with an increased risk for postoperative myocardial injury in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery (33). Together, we speculate whether the stress of surgery worsens endothelial function in patients with previous COVID-19 infection. If so, a key question that remains is whether therapeutics that protect endothelial function could be efficacious in lowering postoperative risk for MACE.

There are several limitations to this study. The N3C Data Enclave relies on electronic health record data collected mostly from large academic centers and thus does not capture patients who may not have reliable access to healthcare or choose to seek care in smaller community centers. In addition, the data regarding comorbidities may be incomplete or misclassified within the health records, and certain comorbidities are associated with disease severity, whereas others influence risk for contracting COVID-19. To account for these factors, we used the CCI within regression models. Given the use of multi-institutional data, it is likely that there is great heterogeneity in the care protocols instituted. The retrospective nature of this study also prevents standardization of protocols. Patients who presented with preoperative cardiovascular events that developed from their COVID-19 infection (e.g., atrial fibrillation) are classified as having the condition at the time of surgery and therefore not counted as a new postoperative outcome. We suspect this contributed to our results showing a decreased risk for postoperative atrial fibrillation seen among those with COVID-19. There is also likely selection bias for surgery among patients with a history of COVID-19; for example, among those with moderate/severe disease, it is possible that patients who underwent surgery early after infection either needed urgent intervention or had a quicker recovery from COVID-19. As such, risk estimates likely are influenced by residual bias and are not representative of patients who were not selected for surgery. Nonetheless, this study assesses a large, national, multi-institutional cohort of patients to understand the influence of COVID-19 on postoperative MACE. Our results highlight that waiting up to 4 wk following infection before surgery and preoperative full vaccination can decrease risk for postoperative MACE. Consideration of COVID-19 disease severity is also crucial for perioperative risk stratification.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental Tables S1–S6: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DFSGWU.

GRANTS

A. N. Kothari was supported by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Grants 3U24TR002306-04S2, U24 TR002306, UL1 TR001436, and 3UL1TR001436-08S3 and National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) IDeA.

DISCLAIMERS

The N3C Publication committee confirmed that this manuscript (MSID: 968.54) is in accordance with N3C data use and attribution policies; however, the content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Authorship was determined using International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) recommendations.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

G.S., N.B.V., and A.N.K. conceived and designed research; N.B.V. performed experiments; G.S. and N.B.V. analyzed data; G.S., S.A.S., X.Y., C.E.F.C., A.S., B.W.T., N.W., K.L., J.C.G., and A.N.K. interpreted results of experiments; G.S. and N.B.V. prepared figures; G.S., N.B.V., and A.N.K. drafted manuscript; G.S., N.B.V., S.A.S., X.Y., C.E.F.C., A.S., B.W.T., N.W., K.L., J.C.G., and A.N.K. edited and revised manuscript; G.S., N.B.V., S.A.S., X.Y., C.E.F.C., A.S., B.W.T., N.W., K.L., J.C.G., and A.N.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The analyses described in this publication were conducted under the DUR RP-A39709 and IRB No. PRO00042159 with data or tools accessed through the NCATS N3C Data Enclave covid.cd2h.org/enclave.

The NCATS N3C Data Enclave was supported by CD2H—The National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) IDeA CTR Collaboration 3U24TR002306-04S2 NCATS U24 TR002306. The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Award No. UL1 TR001436 and 3UL1TR001436-08S3. Additional funding support provided by Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin Endowment. This research was possible because of the patients whose information is included within the data from participating organizations (covid.cd2h.org/dtas) and the organizations and scientists (covid.cd2h.org/duas) who have contributed to the on-going development of this community resource (18).

We gratefully acknowledge the following core contributors to N3C:

Adam B. Wilcox, Adam M. Lee, Alexis Graves, Alfred (Jerrod) Anzalone, Amin Manna, Amit Saha, Amy Olex, Andrea Zhou, Andrew E. Williams, Andrew Southerland, Andrew T. Girvin, Anita Walden, Anjali A. Sharathkumar, Benjamin Amor, Benjamin Bates, Brian Hendricks, Brijesh Patel, Caleb Alexander, Carolyn Bramante, Cavin Ward-Caviness, Charisse Madlock-Brown, Christine Suver, Christopher Chute, Christopher Dillon, Chunlei Wu, Clare Schmitt, Cliff Takemoto, Dan Housman, Davera Gabriel, David A. Eichmann, Diego Mazzotti, Don Brown, Eilis Boudreau, Elaine Hill, Elizabeth Zampino, Emily Carlson Marti, Emily R. Pfaff, Evan French, Farrukh M Koraishy, Federico Mariona, Fred Prior, George Sokos, Greg Martin, Harold Lehmann, Heidi Spratt, Hemalkumar Mehta, Hongfang Liu, Hythem Sidky, J.W. Awori Hayanga, Jami Pincavitch, Jaylyn Clark, Jeremy Richard Harper, Jessica Islam, Jin Ge, Joel Gagnier, Joel H. Saltz, Joel Saltz, Johanna Loomba, John Buse, Jomol Mathew, Joni L. Rutter, Julie A. McMurry, Justin Guinney, Justin Starren, Karen Crowley, Katie Rebecca Bradwell, Kellie M. Walters, Ken Wilkins, Kenneth R. Gersing, Kenrick Dwain Cato, Kimberly Murray, Kristin Kostka, Lavance Northington, Lee Allan Pyles, Leonie Misquitta, Lesley Cottrell, Lili Portilla, Mariam Deacy, Mark M. Bissell, Marshall Clark, Mary Emmett, Mary Morrison Saltz, Matvey B. Palchuk, Melissa A. Haendel, Meredith Adams, Meredith Temple-O'Connor, Michael G. Kurilla, Michele Morris, Nabeel Qureshi, Nasia Safdar, Nicole Garbarini, Noha Sharafeldin, Ofer Sadan, Patricia A. Francis, Penny Wung Burgoon, Peter Robinson, Philip R.O. Payne, Rafael Fuentes, Randeep Jawa, Rebecca Erwin-Cohen, Rena Patel, Richard A. Moffitt, Richard L. Zhu, Rishi Kamaleswaran, Robert Hurley, Robert T. Miller, Saiju Pyarajan, Sam G. Michael, Samuel Bozzette, Sandeep Mallipattu, Satyanarayana Vedula, Scott Chapman, Shawn T. O'Neil, Soko Setoguchi, Stephanie S. Hong, Steve Johnson, Tellen D. Bennett, Tiffany Callahan, Umit Topaloglu, Usman Sheikh, Valery Gordon, Vignesh Subbian, Warren A. Kibbe, Wenndy Hernandez, Will Beasley, Will Cooper, William Hillegass, Xiaohan Tanner Zhang. Details of contributions available at covid.cd2h.org/core-contributors

The following are institutions whose data is released or pending:

Available: Advocate Health Care Network—UL1TR002389: The Institute for Translational Medicine (ITM) • Boston University Medical Campus—UL1TR001430: Boston University Clinical and Translational Science Institute • Brown University—U54GM115677: Advance Clinical Translational Research (Advance-CTR) • Carilion Clinic—UL1TR003015: iTHRIV Integrated Translational health Research Institute of Virginia • Charleston Area Medical Center—U54GM104942: West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute (WVCTSI) • Children’s Hospital Colorado—UL1TR002535: Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute • Columbia University Irving Medical Center—UL1TR001873: Irving Institute for Clinical and Translational Research • Duke University—UL1TR002553: Duke Clinical and Translational Science Institute • George Washington Children’s Research Institute—UL1TR001876: Clinical and Translational Science Institute at Children’s National (CTSA-CN) • George Washington University—UL1TR001876: Clinical and Translational Science Institute at Children’s National (CTSA-CN) • Indiana University School of Medicine—UL1TR002529: Indiana Clinical and Translational Science Institute • Johns Hopkins University—UL1TR003098: Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research • Loyola Medicine—Loyola University Medical Center • Loyola University Medical Center—UL1TR002389: The Institute for Translational Medicine (ITM) • Maine Medical Center—U54GM115516: Northern New England Clinical & Translational Research (NNE-CTR) Network • Massachusetts General Brigham—UL1TR002541: Harvard Catalyst • Mayo Clinic Rochester—UL1TR002377: Mayo Clinic Center for Clinical and Translational Science (CCaTS) • Medical University of South Carolina—UL1TR001450: South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research Institute (SCTR) • Montefiore Medical Center—UL1TR002556: Institute for Clinical and Translational Research at Einstein and Montefiore • Nemours—U54GM104941: Delaware CTR ACCEL Program • NorthShore University HealthSystem—UL1TR002389: The Institute for Translational Medicine (ITM) • Northwestern University at Chicago—UL1TR001422: Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Science Institute (NUCATS) • OCHIN—INV-018455: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation grant to Sage Bionetworks • Oregon Health & Science University—UL1TR002369: Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute • Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center—UL1TR002014: Penn State Clinical and Translational Science Institute • Rush University Medical Center—UL1TR002389: The Institute for Translational Medicine (ITM) • Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey—UL1TR003017: New Jersey Alliance for Clinical and Translational Science • Stony Brook University—U24TR002306 • The Ohio State University—UL1TR002733: Center for Clinical and Translational Science • The State University of New York at Buffalo—UL1TR001412: Clinical and Translational Science Institute • The University of Chicago—UL1TR002389: The Institute for Translational Medicine (ITM) • The University of Iowa—UL1TR002537: Institute for Clinical and Translational Science • The University of Miami Leonard M. Miller School of Medicine—UL1TR002736: University of Miami Clinical and Translational Science Institute • The University of Michigan at Ann Arbor—UL1TR002240: Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research • The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston—UL1TR003167: Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences (CCTS) • The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston—UL1TR001439: The Institute for Translational Sciences • The University of Utah—UL1TR002538: Uhealth Center for Clinical and Translational Science • Tufts Medical Center—UL1TR002544: Tufts Clinical and Translational Science Institute • Tulane University—UL1TR003096: Center for Clinical and Translational Science • University Medical Center New Orleans—U54GM104940: Louisiana Clinical and Translational Science (LA CaTS) Center • University of Alabama at Birmingham—UL1TR003096: Center for Clinical and Translational Science • University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences—UL1TR003107: UAMS Translational Research Institute • University of Cincinnati—UL1TR001425: Center for Clinical and Translational Science and Training • University of Colorado Denver, Anschutz Medical Campus—UL1TR002535: Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute • University of Illinois at Chicago—UL1TR002003: UIC Center for Clinical and Translational Science • University of Kansas Medical Center—UL1TR002366: Frontiers: University of Kansas Clinical and Translational Science Institute • University of Kentucky—UL1TR001998: UK Center for Clinical and Translational Science • University of Massachusetts Medical School Worcester—UL1TR001453: The UMass Center for Clinical and Translational Science (UMCCTS) • University of Minnesota—UL1TR002494: Clinical and Translational Science Institute • University of Mississippi Medical Center—U54GM115428: Mississippi Center for Clinical and Translational Research (CCTR) • University of Nebraska Medical Center—U54GM115458: Great Plains IDeA-Clinical & Translational Research • University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill—UL1TR002489: North Carolina Translational and Clinical Science Institute • University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center—U54GM104938: Oklahoma Clinical and Translational Science Institute (OCTSI) • University of Rochester—UL1TR002001: UR Clinical & Translational Science Institute • University of Southern California—UL1TR001855: The Southern California Clinical and Translational Science Institute (SC CTSI) • University of Vermont—U54GM115516: Northern New England Clinical & Translational Research (NNE-CTR) Network • University of Virginia—UL1TR003015: iTHRIV Integrated Translational health Research Institute of Virginia • University of Washington—UL1TR002319: Institute of Translational Health Sciences • University of Wisconsin-Madison—UL1TR002373: UW Institute for Clinical and Translational Research • Vanderbilt University Medical Center—UL1TR002243: Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research • Virginia Commonwealth University—UL1TR002649: C. Kenneth and Dianne Wright Center for Clinical and Translational Research • Wake Forest University Health Sciences—UL1TR001420: Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute • Washington University in St. Louis—UL1TR002345: Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences • Weill Medical College of Cornell University—UL1TR002384: Weill Cornell Medicine Clinical and Translational Science Center • West Virginia University—U54GM104942: West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute (WVCTSI)

Submitted: Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai—UL1TR001433: ConduITS Institute for Translational Sciences • The University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler—UL1TR003167: Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences (CCTS) • University of California, Davis—UL1TR001860: UCDavis Health Clinical and Translational Science Center • University of California, Irvine—UL1TR001414: The UC Irvine Institute for Clinical and Translational Science (ICTS) • University of California, Los Angeles—UL1TR001881: UCLA Clinical Translational Science Institute • University of California, San Diego—UL1TR001442: Altman Clinical and Translational Research Institute • University of California, San Francisco—UL1TR001872: UCSF Clinical and Translational Science Institute

Pending: Arkansas Children’s Hospital—UL1TR003107: UAMS Translational Research Institute • Baylor College of Medicine—None (Voluntary) • Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia—UL1TR001878: Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics • Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center—UL1TR001425: Center for Clinical and Translational Science and Training • Emory University—UL1TR002378: Georgia Clinical and Translational Science Alliance • HonorHealth—None (Voluntary) • Loyola University Chicago—UL1TR002389: The Institute for Translational Medicine (ITM) • Medical College of Wisconsin—UL1TR001436: Clinical and Translational Science Institute of Southeast Wisconsin • MedStar Health Research Institute—UL1TR001409: The Georgetown-Howard Universities Center for Clinical and Translational Science (GHUCCTS) • MetroHealth—None (Voluntary) • Montana State University—U54GM115371: American Indian/Alaska Native CTR • NYU Langone Medical Center—UL1TR001445: Langone Health’s Clinical and Translational Science Institute • Ochsner Medical Center—U54GM104940: Louisiana Clinical and Translational Science (LA CaTS) Center • Regenstrief Institute—UL1TR002529: Indiana Clinical and Translational Science Institute • Sanford Research—None (Voluntary) • Stanford University—UL1TR003142: Spectrum: The Stanford Center for Clinical and Translational Research and Education • The Rockefeller University—UL1TR001866: Center for Clinical and Translational Science • The Scripps Research Institute—UL1TR002550: Scripps Research Translational Institute • University of Florida—UL1TR001427: UF Clinical and Translational Science Institute • University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center—UL1TR001449: University of New Mexico Clinical and Translational Science Center • University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio—UL1TR002645: Institute for Integration of Medicine and Science • Yale New Haven Hospital—UL1TR001863: Yale Center for Clinical Investigation.

REFERENCES

- 1. El-Boghdadly K, Cook TM, Goodacre T, Kua J, Blake L, Denmark S, McNally S, Mercer N, Moonesinghe SR, Summerton DJ. SARS-CoV-2 infection, COVID-19 and timing of elective surgery: a multidisciplinary consensus statement on behalf of the Association of Anaesthetists, the Centre for Peri-operative Care, the Federation of Surgical Specialty Associations, the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Royal College of Surgeons of England. Anaesthesia 76: 940–946, 2021. doi: 10.1111/anae.15464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.COVIDSurg Collaborative. Outcomes and their state-level variation in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection in the USA: a prospective multicenter study. Ann Surg 275: 247–251, 2022. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.COVIDSurg Collaborative. Mortality and pulmonary complications in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international cohort study. Lancet 396: 27–38, 2020. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31182-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Deng JZ, Chan JS, Potter AL, Chen Y-W, Sandhu HS, Panda N, Chang DC, Yang C-FJ. The risk of postoperative complications after major elective surgery in active or resolved COVID-19 in the United States. Ann Surg 275: 242–246, 2022. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smilowitz NR, Gupta N, Ramakrishna H, Guo Y, Berger JS, Bangalore S. Perioperative major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events associated with noncardiac surgery. JAMA Cardiol 2: 181–187, 2017. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.4792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Devereaux PJ, Sessler DI. Cardiac complications in patients undergoing major noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 373: 2258–2269, 2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1502824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Xie Y, Xu E, Bowe B, Al-Aly Z. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat Med 28: 583–590, 2022. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01689-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hernandez-Hernandez ME, Zee RYL, Pulido-Perez P, Torres-Rasgado E, Romero JR. The effects of biological sex and cardiovascular disease on COVID-19 mortality. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 323: H397–H402, 2022. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00295.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ohno S, Kohjitani A, Miyata M, Tohya A, Yamashita K, Hashiguchi T, Ohishi M, Sugimura M. Recovery of endothelial function after minor-to-moderate surgery is impaired by diabetes mellitus, obesity, hyperuricemia and sevoflurane-based anesthesia. Int Heart J 59: 559–565, 2018. doi: 10.1536/ihj.17-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ekeloef S, Larsen MH, Schou-Pedersen AM, Lykkesfeldt J, Rosenberg J, Gögenür I. Endothelial dysfunction in the early postoperative period after major colon cancer surgery. Br J Anaesth 118: 200–206, 2017. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ekeloef S, Oreskov JO, Falkenberg A, Burcharth J, Schou-Pedersen AMV, Lykkesfeldt J, Gögenur I. Endothelial dysfunction and myocardial injury after major emergency abdominal surgery: a prospective cohort study. BMC Anesthesiol 20: 67, 2020. doi: 10.1186/s12871-020-00977-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vinson AJ, Dai R, Agarwal G, Anzalone AJ, Lee SB, French E, Olex AL, Madhira V, Mannon RB; National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) Consortium. Sex and organ-specific risk of major adverse renal or cardiac events in solid organ transplant recipients with COVID-19. Am J Transplant 22: 245–259, 2022. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Verhagen NB, Koerber NK, Szabo A, Taylor B, Wainaina JN, Evans DB, Kothari AN; N3C Consortium. Vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 decreases risk of adverse events in patients who develop COVID-19 following cancer surgery. Ann Surg Oncol 30: 1305–1308, 2022. doi: 10.1245/s10434-022-12916-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bryant JM, Boncyk CS, Rengel KF, Doan V, Snarskis C, McEvoy MD, McCarthy KY, Li G, Sandberg WS, Freundlich RE. Association of time to surgery after COVID-19 infection with risk of postoperative cardiovascular morbidity. JAMA Netw Open 5: e2246922, 2022. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.46922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.COVIDSurg Collaborative; GlobalSurg Collaborative. Timing of surgery following SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international prospective cohort study. Anaesthesia 76: 748–758, 2021. doi: 10.1111/anae.15458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Al Ani A, Tahtamoni R, Mohammad Y, Al-Ayoubi F, Haider N, Al-Mashhadi A. Impacts of severity of Covid-19 infection on the morbidity and mortality of surgical patients. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 79: 103910, 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ng OT, Marimuthu K, Lim N, Lim ZQ, Thevasagayam NM, Koh V, Chiew CJ, Ma S, Koh M, Low PY, Tan SB, Ho J, Maurer-Stroh S, Lee VJM, Leo Y-S, Tan KB, Cook AR, Tan CC. Analysis of COVID-19 incidence and severity among adults vaccinated with 2-dose mRNA COVID-19 or inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccines with and without Boosters in Singapore. JAMA Netw Open 5: e2228900, 2022. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.28900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Haendel MA, Chute CG, Bennett TD, Eichmann DA, Guinney J, Kibbe WA, et al. The National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C): Rationale, design, infrastructure, and deployment. J Am Med Inform Assoc 28: 427–443, 2021. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO Working Group on the Clinical Characterisation and Management of COVID-19 infection. A minimal common outcome measure set for COVID-19 clinical research. Lancet Infect Dis 20: e192–e197, 2020. [Erratum in Lancet Infect Dis 20: e250, 2020]. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30483-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bennett TD, Moffitt RA, Hajagos JG, Amor B, Anand A, Bissell MM, et al. Clinical characterization and prediction of clinical severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection among us adults using data from the US National COVID cohort collaborative. JAMA Netw Open 4: e2116901, 2021. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.16901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40: 373–383, 1987. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chander R, Kapoor NK, Dhawan BN. Hepatoprotective activity of silymarin against hepatic damage in Mastomys natalensis infected with Plasmodium berghei. Indian J Med Res 90: 472–477, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vascular Events In Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation (VISION) Study Investigators; Devereaux PJ, Chan MT, Alonso-Coello P, Walsh M, Berwanger O, et al. Association between postoperative troponin levels and 30-day mortality among patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA 307: 2295–2304, 2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Devereaux PJ, Mrkobrada M, Sessler DI, Leslie K, Alonso-Coello P, Kurz A, et al. Aspirin in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 370: 1494–1503, 2014. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.POISE Study Group; Devereaux PJ, Yang H, Yusuf S, Guyatt G, Leslie K, Villar JC, Xavier D, Chrolavicius S, Greenspan L, Pogue J, Pais P, Liu L, Xu S, Málaga G, Avezum A, Chan M, Montori VM, Jacka M, Choi P. Effects of extended-release metoprolol succinate in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery (POISE trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 371: 1839–1847, 2008. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60601-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van der Sluijs KM, Bakker EA, Schuijt TJ, Joseph J, Kavousi M, Geersing G-J, Rutten FH, Hartman YAW, Thijssen DHJ, Eijsvogels TMH. Long-term cardiovascular health status and physical functioning of nonhospitalized patients with COVID-19 compared with non-COVID-19 controls. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 324: H47–H56, 2023. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00335.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tenforde MW, Self WH, Adams K, Gaglani M, Ginde AA, McNeal T, et al. Association between mRNA vaccination and COVID-19 hospitalization and disease severity. JAMA 326: 2043–2054, 2021. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.19499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.COVIDSurg Collaborative, GlobalSurg Collaborative. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination modelling for safe surgery to save lives: data from an international prospective cohort study. Br J Surg 108: 1056–1063, 2021. doi: 10.1093/bjs/znab101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Taghioff SM, Slavin BR, Narasimman M, Samaha G, Samaha M, Holton T, Singh D. The influence of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination on post-operative outcomes in microsurgery patients. Microsurgery 42: 685–695, 2022. doi: 10.1002/micr.30940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Prasad NK, Lake R, Englum BR, Turner DJ, Siddiqui T, Mayorga-Carlin M, Sorkin JD, Lal BK. COVID-19 vaccination associated with reduced postoperative SARS-CoV-2 infection and morbidity. Ann Surg 275: 31–36, 2022. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Xu SW, Ilyas I, Weng JP. Endothelial dysfunction in COVID-19: an overview of evidence, biomarkers, mechanisms and potential therapies. Acta Pharmacol Sin 44: 695–709, 2022. doi: 10.1038/s41401-022-00998-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sabioni L, De Lorenzo A, Castro-Faria-Neto HC, Estato V, Tibirica E. Long-term assessment of systemic microcirculatory function and plasma cytokines after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Braz J Infect Dis 27: 102719, 2023. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2022.102719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McIlroy DR, Chan MTV, Wallace SK, Symons JA, Koo EGY, Chu LCY, Myles PS. Automated preoperative assessment of endothelial dysfunction and risk stratification for perioperative myocardial injury in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth 112: 47–56, 2014. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Tables S1–S6: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DFSGWU.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.