Keywords: C57BL6 mice, hypercapnic gas challenge, hypoxic gas challenge, hypoxic-hypercapnic gas challenge, ventilatory responses

Abstract

Interactions between hypoxic and hypercapnic signaling pathways, expressed as ventilatory changes occurring during and following a simultaneous hypoxic-hypercapnic gas challenge (HH-C) have not been determined systematically in mice. This study in unanesthetized male C57BL6 mice addressed the hypothesis that hypoxic (HX) and hypercapnic (HC) signaling events display an array of interactions indicative of coordination by peripheral and central respiratory mechanisms. We evaluated the ventilatory responses elicited by hypoxic (HX-C, 10%, O2, 90% N2), hypercapnic (HC-C, 5% CO2, 21%, O2, 90% N2), and HH-C (10% O2, 5%, CO2, 85% N2) challenges to determine whether ventilatory responses elicited by HH-C were simply additive of responses elicited by HX-C and HC-C, or whether other patterns of interactions existed. Responses elicited by HH-C were additive for tidal volume, minute ventilation and expiratory time, among others. Responses elicited by HH-C were hypoadditive of the HX-C and HC-C responses (i.e., HH-C responses were less than expected by simple addition of HX-C and HC-C responses) for frequency of breathing, inspiratory time and relaxation time, among others. In addition, end-expiratory pause increased during HX-C, but decreased during HC-C and HH-C, therefore showing that HC-C responses influenced the HX-C responses when given simultaneously. Return to room-air responses was additive for tidal volume and minute ventilation, among others, whereas they were hypoadditive for frequency of breathing, inspiratory time, peak inspiratory flow, apneic pause, inspiratory and expiratory drives, and rejection index. These data show that HX-C and HH-C signaling pathways interact with one another in additive and often hypoadditive processes.

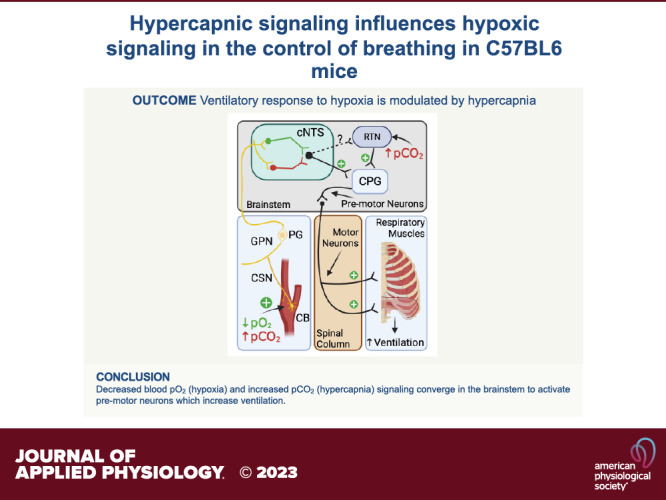

NEW & NOTEWORTHY We present data showing that the ventilatory responses elicited by a hypoxic gas challenge in male C57BL6 mice are markedly altered by coexposure to hypercapnic gas challenge with hypercapnic responses often dominating the hypoxic responses. These data suggest that hypercapnic signaling processes activated within brainstem regions, such as the retrotrapezoid nuclei, may directly modulate the signaling processes within the nuclei tractus solitarius resulting from hypoxic-induced increase in carotid body chemoreceptor input to these nuclei.

INTRODUCTION

Ventilatory responses to decreases in blood O2, and elevations in CO2 and H+ ions are mediated largely by the carotid body and nuclei in the brainstem (1–5). Carotid body glomus cells depolarize in response to decreases in blood O2, elevations in blood CO2 and from carbonic-anhydrase-catalyzed production of H+ ions from increased availability of blood-borne CO2 (6–13). Depolarization triggers glomus cells to release neurotransmitters (14–23) that excite chemoafferent nerve terminals in the carotid sinus nerve (CSN) that terminate in the commissural nuclei tractus solitarius (cNTS) (6–13). CSN chemoafferent input to the cNTS triggers cardiorespiratory responses to restore arterial blood-gas homeostasis (10, 17). Hypercapnic ventilatory signaling relies on carotid body-CSN input to the cNTS (4, 5, 10, 24–27) and on structures such as the retrotrapezoid nucleus in the brainstem (28–35). Activation of central neurons involves entry of CO2 into cerebrospinal fluid, carbonic-anhydrase-catalyzed conversion of CO2 and H2O to H2CO3, spontaneous breakdown of H2CO3 to bicarbonate and H+ ions, and H+-mediated activation of neurons via activation of acid-sensing ion channels (28, 29). Moreover, there is substantial evidence in that central and peripheral chemoreceptive systems interact with one another (36–38) and that peripheral carotid sinus chemoreceptors determine the respiratory sensitivity of central chemoreceptors to CO2 (39). The exact nature of these interactions is complicated and often species dependent (36–39). In humans, compelling evidence has been provided that peripheral and central chemoreflexes have hypoadditive (40, 41), additive (42, 43), or hyperadditive (44, 45) effects on ventilation. In addition, there is substantial debate as to whether a central respiratory oxygen sensor does (46–48) or does not (49, 50) exist in mammals. Taken together, it is apparent that the numerous factors, such as genetic traits and sex have enormous influence on ventilatory functions including chemoreflex activity (1–5).

Wild-type (WT) mice of various strains and genetically engineered mice of these strains are used to study mechanisms by which hypoxic (HX-C) and hypercapnic (HC-C) gas challenges elicit carotid body-dependent and -independent ventilatory responses (22, 23, 51–68). For example, the ventilatory responses elicited by HX-C are smaller in C57BL6 mice with CSNX (60), and initial ventilatory responses that occur in response to HC-C are diminished in freely moving C57BL6 mice with CSNX (56), whereas ventilatory responses to a hyperoxic (100% O2)-HC-C (5% CO2) gas challenge were reduced after CSNX in urethane-anesthetized adult male C57BL-6CrSlc mice (68). The increases in breathing in response to HX-C and HC-C can outlast the challenge period and these responses are referred to as short-term potentiation of ventilation (60, 61, 69–73). We reported that short-term potentiation following HX-C (60) and HC-C (67) is virtually absent in C57BL6 mice with CSNX. We used C57BL6 mice because this strain is widely used in studies pertaining to peripheral/central cardiorespiratory systems and to generate genetically engineered mice to study cardiorespiratory control processes (57, 58, 60, 74–77). C57BL6 mice are used to study sleep-apnea mechanisms because they display irregular breathing patterns, including apneas during sleep and wakefulness and disordered breathing on return to room air after HX-C or HC-C (55, 78–85). Genetic (68, 79–81, 83, 86–89) and neurochemical (68, 83, 85, 90–94) factors that drive breathing patterns of C57BL6 mice and their responses to HC-C and HX-C are well known. Additionally, the importance of key structural differences in carotid bodies of C57BL6 mice compared to other strains with regards to their breathing patterns is also known (95–97).

As mentioned above, the issue as to whether the interactions between peripheral and central chemoreflexes are hypoadditive, additive or hyperadditive is under serious debate (51–56). Mouse models amenable to alterations in gene expression with C57BL6 background offer a way to determine the roles of genetic traits and gender in the interactions between hypoxic (HX) and hypercapnic (HC) signaling events. Potential interactions between HX and HC signaling pathways in ventilatory responses during and following a HX-HC gas challenge (i.e., HH-C) have not been determined in a systematic way in C57BL6 mice. In this study we have measured an extensive array of ventilatory parameters in unrestrained adult male C57BL6 mice to provide a comprehensive set of data to address our hypothesis that HX and HC signaling events will display an array of interactions indicative of coordination by peripheral and central respiratory mechanisms. The questions addressed were 1) how do ventilatory responses elicited by HX-C (10%, O2, 90% N2) and HC-C (5% CO2, 21%, O2, 90% N2) compare to those of HH-C (10% O2, 5%, CO2, 85% N2) and 2) are the responses elicited by HH-C simply additive of HX and HC responses or do other (e.g., hypoadditive or hyperadditive) patterns of interactions exist.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Permissions

All of the studies described were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 80-23) revised in 1996. We obtained approval from the Animal Care and Use Committee of Case Western Reserve University for all protocols.

Mice

Male adult C57BL6 mice from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) delivered pathogen-free were housed in a pathogen-free room on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle and allowed unlimited access to water and standard mouse chow. Mice were randomized into three groups that would receive HX-C, HC-C, or HH-C. After the plethysmography studies were performed, the mice were euthanized via overexposure to CO2 and cervical dislocation.

Whole Body Plethysmography

Methods for performing the whole body plethysmography in unrestrained freely moving mice have been detailed previously (57–61, 67, 73). Each mouse was placed into a whole body plethysmograph (Buxco Small Animal Whole Body Plethysmography, DataSciences, Inc., St. Paul, MN) to record breathing continuously. Flow rates of room air and HX-C (10% O2, 90% N2), HC-C (5% CO2, 21% O2, 74% N2) and HH-C (10% O2, 5% CO2, 85% N2) gas mixtures were 0.5 L/min. Chamber temperature (°C) and chamber relative humidity (%) were constantly monitored via sensors in the plethysmography chambers and breathing waveforms were continuously recorded by built-in algorithms to allow FinePointe software to analyze recorded waveforms (https://www.datasci.com/products/buxco-respiratoryproducts/finepointe-whole-body-plethysmography). Air temperature in the chambers during the 15-min period immediately before exposure to the HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C was 26.8 ± 0.1, 26.7 ± 0.1 and 26.5 ± 0.1°C, respectively (P > 0.05 for all between-group comparisons). The relative percent humidity in the chambers during the 15-min period immediately before exposure to the HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C was 45.6 ± 1.8, 46.9 ± 1.9 and 46.4 ± 1.3°C, respectively (P > 0.05 for all between-group comparisons). Air temperature in the chambers housing the mice changed minimally during each stage of the protocol (∼0.2°C), whereas the relative percent humidity of the chambers fell by 5%–10% during exposure to the gas challenges. Recorded ventilatory parameters were constantly corrected for these changes in chamber parameters by built-in software. Choice of ventilatory parameters (Table 1) was based on the importance of each of parameter to understanding the interactions between HX-C and HC-C on ventilatory processes (57–61, 67, 73). The description of these parameters including frequency of breathing (fr), tidal volume (Vt), minute ventilation (V̇e), inspiratory time (Ti), expiratory time (Te), end-inspiratory pause (EIP), end-expiratory pause (EEP), peak inspiratory flow (PIF), peak expiratory flow (PEF), relaxation time, apneic pause, inspiratory drive, expiratory drive, and rejection is provided in Table 1. A full description of the methods by which the plethysmography software accepted or rejected breaths is given in Getsy et al. (61).

Table 1.

Definition of ventilatory parameters described in this study

| Parameter | Abbreviation | Units | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Directly recorded parameters | |||

| Frequency of breaths | fr | breaths/min | Rate of breathing |

| Inspiratory time | Ti | s | Duration of inspiration |

| Expiratory time | Te | s | Duration of expiration |

| End-inspiratory pause | EIP | ms | Pause between end of inspiration start of expiration |

| End-expiratory pause | EEP | ms | Pause between end of expiration and start of inspiration |

| Relaxation time | RT | s | Time taken to expire 64% of Vt |

| Tidal volume | Vt | mL | Volume of inspired air per breath |

| Peak inspiratory flow | PIF | mL/s | Maximum inspiratory flow |

| Peak expiratory flow | PEF | mL/s | Maximum expiratory flow |

| Rejection index | RI | % | % of noneupneic breaths per epoch |

| Derived parameters | |||

| Minute ventilation | V̇e = fr × Vt | mL/min | Total volume of air inspired per min |

| Apneic pause | AP = (Te/RT) − 1 | No units | Elongated expiratory pause |

| Inspiratory drive | Vt /Ti | mL/s | Central urge to inhale |

| Expiratory drive | Vt /Te | mL/s | Central drive to exhale |

Protocols for the Recording of Ventilatory Responses during and following Gas Challenges

On the particular day of study, each mouse was placed in an individual plexiglass plethysmography chamber and given at least 60 min to acclimatize. Once the mouse had settled and stable ventilatory parameters were obtained, the mouse was exposed to a 5-min episode of HX-C (10% O2–90% N2), HC-C (5% CO2, 21% O2, 74% N2), or HH-C (10% O2, 5% CO2, 85% N2) before return to room air for 15 min. The challenges were given for 5 min because data has shown that 5-min exposures are associated with pronounced changes in ventilatory parameters that reach plateau levels before introduction of room air and also because the return to room air following HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C are associated with their own distinct ventilatory patterns (61).

Statistics

With respect to power analyses, we used the power calculation described in Ref. 98. The sample size required for a continuous variable (e.g., depth of respiratory depression) is: n = 1 + 2 C(s/d)2 where s = standard deviation of samples, d = the difference that can be detected, and C is dependent on the α (0.05) and the power (1 − β) of 80% = 7.85. Using these values in the formula to detect a difference of 5% with a standard deviation of 4%, n = 6.02 mice of each experimental (gas) challenge was determined. As such, when measuring continuous variable phenotypes with low standard error as can be typical in our data, six mice of any particular sex and genotype can be used. However, in our experience, the power analyses do not necessarily predict with accuracy the response patterns of C57BL/6 mice and so we always study blocks of 4 mice over several months to collect strong data in 12 or in this case 16 mice. The 16 mice per group gave us full statistical power to analyze the similarities/differences between the challenges (error mean square terms consistent with suitable power for all analyses). A given interaction was qualified as hypoadditive if the addition of actual HX-C and HC-C responses (designated HX + HC responses) was clearly less than what occurred during the actual HH-C challenges. A given interaction was qualified as additive if the addition of the actual HX-C responses and the actual HC-C) responses (HX + HC responses) were clearly equivalent to what occurred during the actual HH-C challenges. A given interaction was qualified as hyperadditive if the addition of the actual HX-C responses and the actual HC-C responses (HX + HC responses) were clearly much greater than what occurred during the actual HH-C challenges. A data point was recorded every 15 s (with each data point representing the average value of all breaths collected over a 15 s period), before the HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C (i.e., the 5-min period before the challenges; prevalues), during the HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C (the entire 5-min challenge) and after the challenges (15 min of room air). Total responses that occurred during the challenges and on return to room air were summed and expressed as the total cumulative %change from prevalues. The cumulative response was determined for each mouse by the formulas: 1) total gas challenge response = (sum of 20 values during gas challenge) − (mean of prevalues × 20) and 2) total room-air response = (sum of 60 values during room-air phase) − (mean of prevalues × 60). Means ± SE of group data were then calculated. There were 20 values (i.e., data points) for each mouse recorded during the gas challenge (four 15-s data points per min × 5-min recording period = 20 data points). Similarly, 60 values were collected for the post-gas challenge (room air) phase for each mouse (four 15 s data points per min × 15-min recording period = 60 data points). All summary data are presented as means ± SE. Data were analyzed by one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Student’s modified t test with Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons between means using the error mean square terms from each ANOVA (99–102). P < 0.05 denoted the initial level of significance that was modified according to the number of comparisons between means (88). The modified t statistic is t = (mean of group 1 − mean of group 2)/[s2 × (1/n1 + 1/n2)1/2], where s2 = the mean square within groups term from the ANOVA (square root of the value is taken for the modified t statistic formula) and n1 and n2 are the numbers of mice/group. Based on elementary inequality (Bonferroni’s inequality), a conservative critical value for modified t statistics taken from tables of t distribution using a significance level of P/m, where m = number of comparisons between groups. The degrees of freedom are those for the mean square for within-group variation from ANOVA tables. Critical Bonferroni values are approximated from tables of the normal curve by t* = z + (z + z3)/4n, with n = degrees of freedom and z = critical normal curve value for P/m (99–102). Wallenstein et al. (100) reported that the Bonferroni procedure is preferable for general use since it is easy to apply, has the widest range of applications, and gives critical values lower than those of other procedures if the number of comparisons can be limited. Practical application of the Bonferroni procedure was confirmed and expanded by Ludbrook (101) and McHugh (102). The use of 16 mice per group allowed for actual and derived data (e.g., deltas and sums) that was robust with standard errors consistently less than 10% of the mean. All statistical analyses were done with GraphPad (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Resting Parameters

The numbers of mice in the three groups and their ages, body weights and resting ventilatory values recorded before HX-C (Group 1), HC-C (Group 2), or HH-C (Group 3) are shown in Table 2. The ages and body weights of the groups were equal to one another (P > 0.05, for all comparisons). Most resting ventilatory values were similar in the three groups although resting fr was higher and resting EEP was lower in the HH-C group than HX-C and HC-C groups (P < 0.05, for all comparisons).

Table 2.

Rat descriptors and ventilatory values before the gas challenges

| Values before Gas Challenges |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | HX-C | HC-C | HH-C |

| Number | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Age, days | 94.3 ± 0.9 | 97.0 ± 0.9 | 93.3 ± 0.21 |

| Body weight, g | 27.8 ± 0.4 | 27.9 ± 0.4 | 27.5 ± 0.4 |

| Frequency, breaths/min | 172 ± 4 | 176 ± 4 | 197 ± 4* |

| Tidal volume, mL | 0.155 ± 0.004 | 0.155 ± 0.005 | 0.153 ± 0.007 |

| Minute volume, mL/min | 26.0 ± 0.6 | 26.2 ± 1.2 | 30.0 ± 1.6 |

| Inspiratory time, s | 0.124 ± 0.002 | 0.119 ± 0.002 | 0.111 ± 0.003† |

| Expiratory time, s | 0.243 ± 0.009 | 0.240 ± 0.007 | 0.210 ± 0.006 |

| End-inspiratory pause, ms | 2.71 ± 0.04 | 2.64 ± 0.04 | 2.63 ± 0.04 |

| End-expiratory pause, ms | 39.1 ± 6.5 | 46.0 ± 6.3 | 23.8 ± 3.2* |

| Relaxation time, s | 0.104 ± 0.003 | 0.105 ± 0.003 | 0.096 ± 0.003 |

| Apneic pauses | 1.36 ± 0.06 | 1.31 ± 0.04 | 1.19 ± 0.03† |

| Peak inspiratory flow, mL/s | 2.10 ± 0.04 | 2.14 ± 0.08 | 2.34 ± 0.10 |

| Peak expiratory flow, mL/s | 1.64 ± 0.07 | 1.72 ± 0.12 | 1.83 ± 0.15 |

| Inspiratory drive, mL/s | 1.26 ± 0.03 | 1.29 ± 0.05 | 1.42 ± 0.07 |

| Expiratory drive, mL/s | 0.65 ± 0.02 | 0.64 ± 0.03 | 0.75 ± 0.04 |

| Rejection index, % | 18.9 ± 4.5 | 14.0 ± 2.5 | 17.7 ± 3.7 |

The data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.05, significantly different from hypoxia values and hypercapnia values. †P < 0.05, significantly different from hypoxia values only. HX-C, hypoxic gas challenge; HC-C, hypercapnic gas challenge; HH-C, hypoxic-hypercapnic gas challenge.

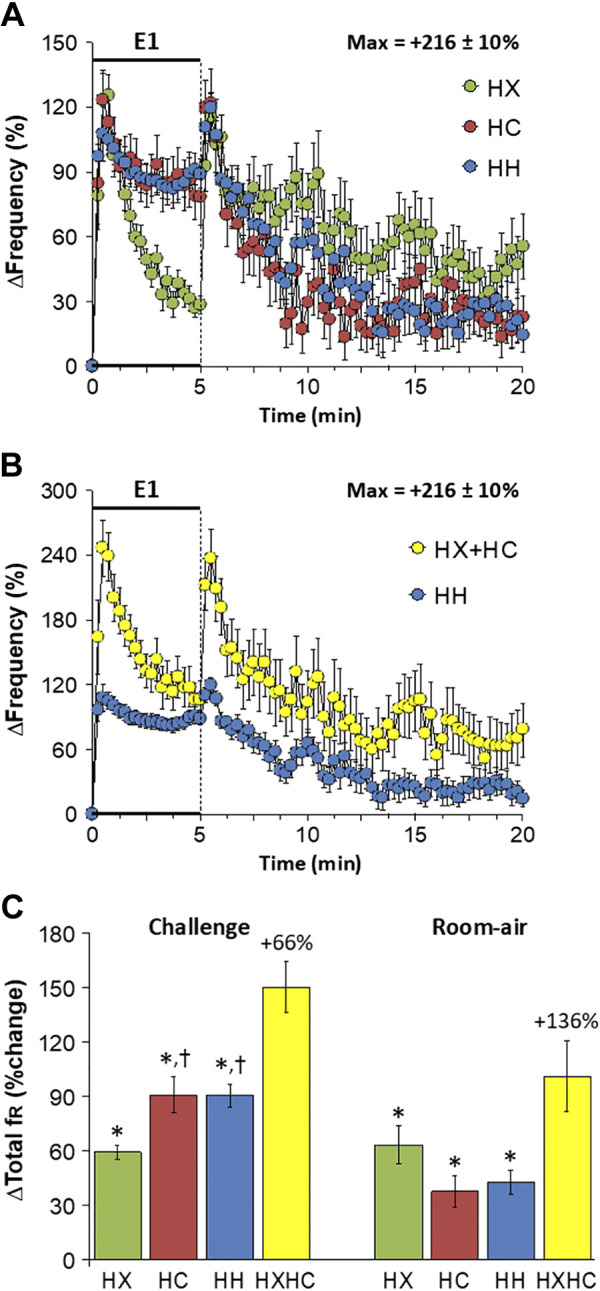

Frequency of Breathing

Changes in frequency of breathing (fr) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C are summarized in Fig. 1A. HX-C elicited an increase in fr associated with a decline toward baseline as the challenge progressed (i.e., roll-off). HC-C and HH-C elicited equivalent increases in fr that were not subject to roll-off. The maximal initial responses (expressed as %change from prevalues) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C were +125 ± 10%, +123 ± 12%, and +108 ± 12%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P > 0.05, no between-group differences) and the values at the end of the HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C (5-min time-point) were +28 ± 4%, +78 ± 13%, and +89 ± 7%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P < 0.05, HC-C and HH-C responses greater than the HX-C response). As such, HH-C responses were smaller than those arising from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 1B). On return to room air, fr rose dramatically following HX-C and remained above prechallenge levels over the 15-min recording period (Fig. 1A). Room-air responses after HC-C and HH-C were similar to one another (Fig. 1A). Accordingly, return to room-air responses following HH-C were smaller than those from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 1B). Total responses during HC-C and HH-C were similar to one another and larger than the HX-C responses; thus the total HH-C response was less than addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 1C). Total responses on return to room air following HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C were similar to one another such that the total post-HH-C response was smaller than addition of post-HX-C and post-HC-C responses (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

A: changes in frequency of breathing during a hypoxic (HX, 10% O2, 90% N2), hypercapnic (HC, 5% CO2, 21% O2, 74% N2), or hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH, 10% O2, 5% CO2, 85% N2) gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air in freely moving adult male C57BL6 mice. The maximum value ± SE recorded during acclimatization is shown. B: actual changes in frequency of breathing during the HH gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air superimposed with the simple addition of HX and HC (HX + HC) values and those on return to room air. C: total frequency of breathing (fr) responses during the HX, HC, or HH challenges with simple addition of HX and HC challenges shown for reference. The %difference between the true HH means and HX + HC means is shown. There were 16 mice in each group. The data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.5, significant response. †P < 0.5, significant response HC or HH vs. HX.

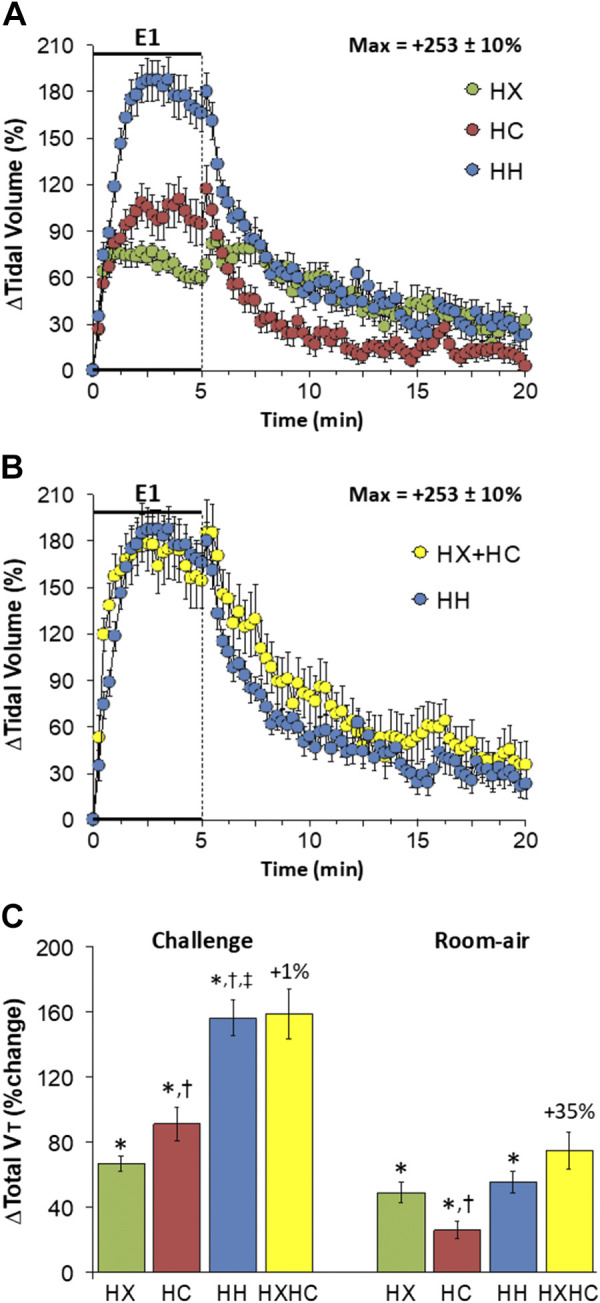

Tidal Volume

Changes in tidal volume (Vt) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C are summarized in Fig. 2A. HX-C and HC-C elicited similar sustained increases that were substantially smaller than the sustained increase in Vt elicited by HH-C. The maximal initial responses (%change from prevalues) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C were +76 ± 7%, +108 ± 12%, and +188 ± 15%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P < 0.05, HC-C and HH-C greater than HXC, HH-C greater than HC-C) and the values at the end of the HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C (5-min time-point) were +60 ± 4%, +95 ± 14%, and +166 ± 12%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P < 0.05, HC-C and HH-C responses greater than the HX-C response, HH-C response greater than the HC-C response). As such, HH-C responses were equal to those arising from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 2B). On return to room air, Vt subsided toward baseline in all three groups (Fig. 2A) such that the HH-C responses were similar to adding the HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 2C). Total response during HH-C was greater than that during HC-C, which in turn was greater than that during HX-C; thus the total HH-C response was equal to addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 2C). Total post-HC-C responses were smaller than those post-HX-C such that the total HH-C response was partially smaller than addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

A: changes in tidal volume during a hypoxic (HX, 10% O2, 90% N2), hypercapnic (HC, 5% CO2, 21% O2, 74% N2), or hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH, 10% O2, 5% CO2, 85% N2) gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air in freely moving adult male C57BL6 mice. The maximum value ± SE recorded during acclimatization is shown. B: actual changes in tidal volume during the HH gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air superimposed with the simple addition of the HX and HC (HX+HC) values and those on return to room air. C: total tidal volume (Vt) responses during HX, HC, or HH challenges with the simple addition of HX and HC challenges shown for reference. The %difference between true HH means and HX+HC means are shown. There were 16 mice in each group. The data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.5, significant response. †P < 0.5, significant response HC or HH vs. HX. ‡P < 0.5, significant response HH vs. HC.

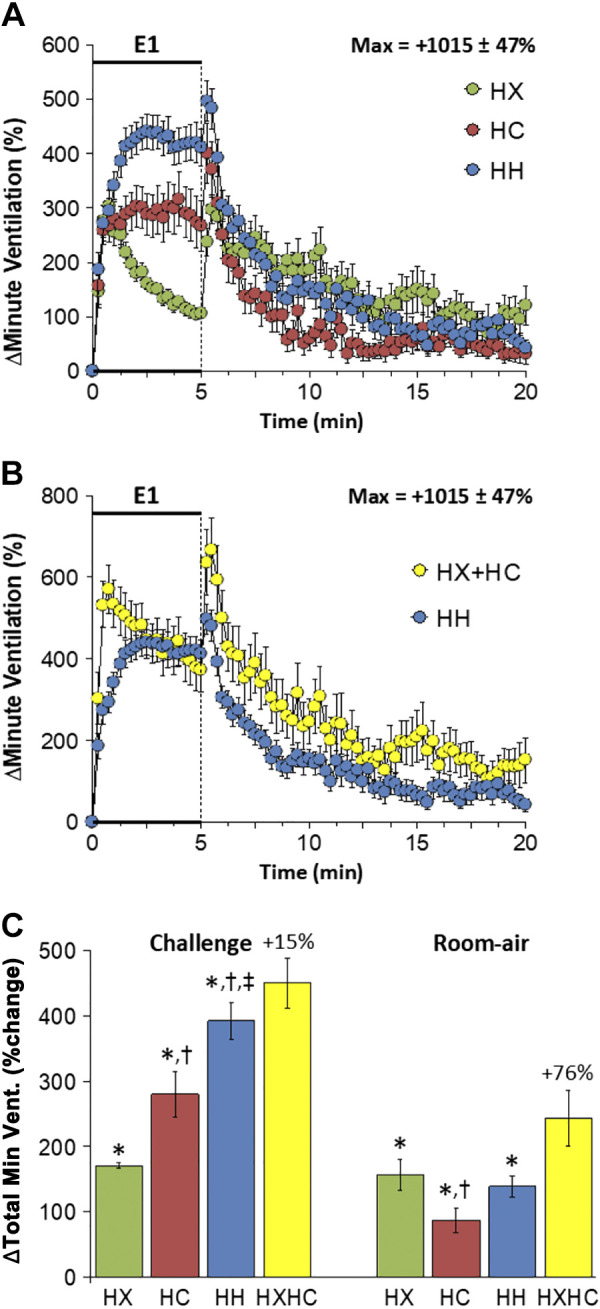

Minute Ventilation

Changes in minute ventilation (V̇e) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C are summarized in Fig. 3A. HX-C elicited an increase in V̇e associated with pronounced roll-off. HC-C and HH-C elicited increases in V̇e that were not subject to roll-off, with the HC-C response smaller than the HH-C response. The maximal initial responses (%change from prevalues) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C were +303 ± 29%, +316 ± 30%, and +440 ± 32%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P < 0.05, HH-C greater than HX-C and HC-C) and the values at the end of the HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C (5-min time-point) were +106 ± 7%, +267 ± 36%, and +410 ± 35%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P > 0.05, HC-C and HH-C responses greater than the HX-C response, HH-C response greater than the HC-C response). Accordingly, the HH-C responses were smaller initially than those from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses but were similar to the addition of HX-C and HC-C at the end of the 5-min time-point. (Fig. 3B). On return to room air, V̇e rose markedly following HX-C and remained above prechallenge levels at least 15 min (Fig. 3A). The room-air responses following HC-C and HH-C were similar to one another and returned close to baseline values after 15 min (Fig. 3A). As such, the return to room-air responses following HH-C were less than on adding the HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 3B). Total responses during HC-C and HH-C were larger than HX-C responses so that the total HH-C response was smaller than addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 3C). Total responses on return to room air after HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C were similar so that the total post-HH-C response was less than addition of post-HX-C and post-HC-C responses (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

A: changes in minute ventilation during a hypoxic (HX, 10% O2, 90% N2), hypercapnic (HC, 5% CO2, 21% O2, 74% N2) or hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH, 10% O2, 5% CO2, 85% N2) gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air in freely moving adult male C57BL6 mice. The maximum value ± SE recorded during acclimatization is shown. B: actual changes in minute ventilation during HH gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air superimposed with the simple addition of the HX and HC (HX+HC) values and those on return to room air. C: total minute ventilation (Min Vent) responses during HX, HC, or HH challenges with simple addition of HX and HC challenges shown for reference. The %difference between true HH means and HX+HC means are shown. There were 16 mice in each group. The data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.5, significant response. †P < 0.5, significant response HC or HH vs. HX. ‡P < 0.5, significant response HH vs. HC.

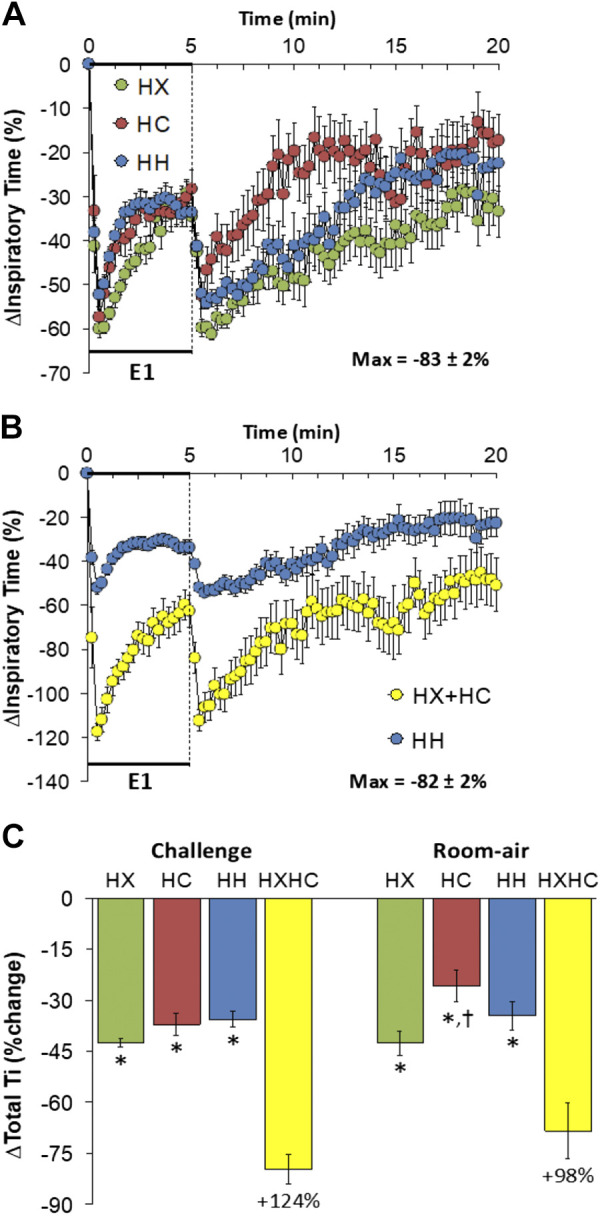

Inspiratory Time

Changes in inspiratory time (Ti) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C are shown in Fig. 4A. HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C elicited decrease in Ti associated with a pronounced but incomplete recovery toward baseline as the challenges progressed (i.e., roll-off). The maximal initial responses (%change from prevalues) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C were −60 ± 2%, −57 ± 2%, and −52 ± 3%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P > 0.05, no between-group differences) and the values at the end of the HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C (5-min time-point) were −35 ± 3%, −28 ± 4%, and −34 ± 3%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P > 0.05, no between-group differences). As such, HH-C responses were much smaller than addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 4B). On return to room air, Ti fell after HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C before returning toward prechallenge levels over the 15-min recording period (Fig. 4A). Return to room-air responses following HC-C and HH-C were similar to one another and approached closer to baseline values compared to HX-C approximately 5 min before the end of the 15-min return to room-air exposure. (Fig. 4A). Accordingly, the return to room-air responses following HH-C were consistently smaller than addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 4B). Total responses during HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C were similar to one another; thus the total HH-C response was less than addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 4C). Total responses on return to room air following HC-C were smaller than following HX-C or HH-C (Fig. 4C); therefore the total post-HH-C response was smaller than addition of post-HX-C and post-HC-C responses (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

A: changes in inspiratory time during a hypoxic (HX, 10% O2, 90% N2), hypercapnic (HC, 5% CO2, 21% O2, 74% N2) or hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH, 10% O2, 5% CO2, 85% N2) gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air in freely moving adult male C57BL6 mice. The maximum value ± SE recorded during acclimatization is shown. B: actual changes in inspiratory time during HH gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air superimposed with the simple addition of the HX and HC (HX+HC) values and those on return to room air. C: total inspiratory time (Ti) responses during HX, HC, or HH challenges with simple addition of HX and HC challenges shown for reference. The %difference between the true HH means and HX+HC means are shown. There were 16 mice in each group. The data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.5, significant response. †P < 0.5, significant response HC or HH vs. HX.

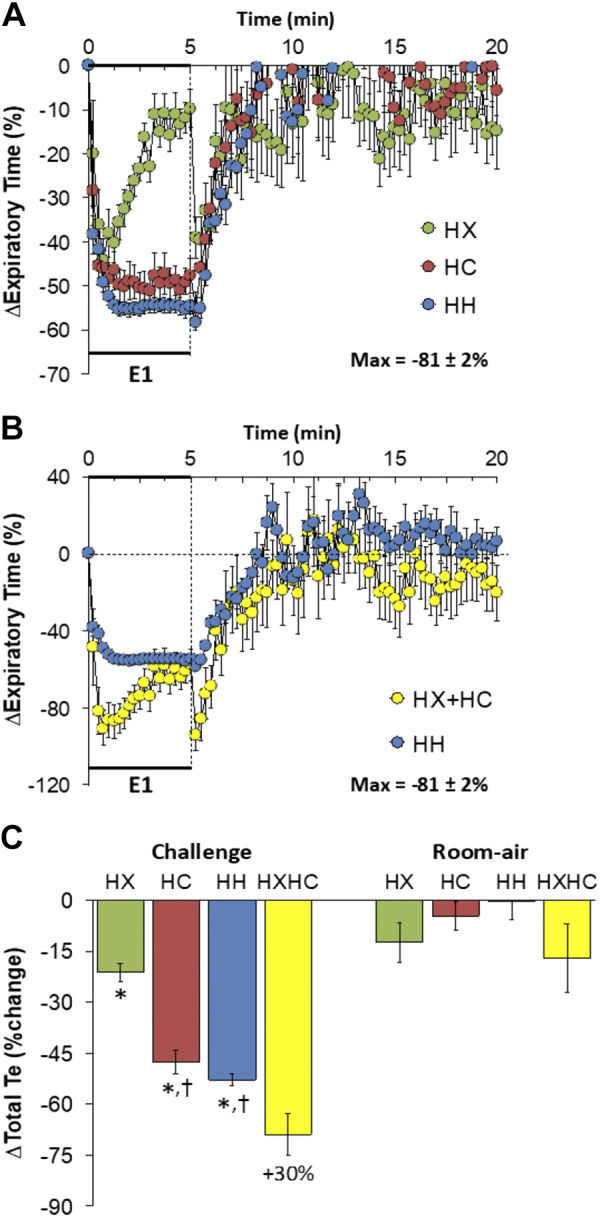

Expiratory Time

Changes in expiratory time (Te) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C are shown in Fig. 5A. HX-C elicited a fall in Te associated with a pronounced and almost complete recovery to baseline. In contrast, HC-C and HH-C were associated with equal falls in Te that were sustained over the 5-min period. The maximal initial responses (%change from prevalues) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C were −44 ± 5%, −51 ± 4%, and −55 ± 2%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P > 0.05, no between-group differences) and the values at the end of the HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C (5-min time-point) were −10 ± 3%, −48 ± 4%, and −55 ± 2%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P < 0.05, HC-C and HH-C responses greater than the HX-C response). As such, HH-C responses were smaller than from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 5B). On return to room air, Te returned rapidly toward baseline following HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C (Fig. 5A). Except for the initial moments, the return to room-air responses after HH-C were similar to those from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 5B). Total responses during HC-C and HH-C were similar to each other and greater than HX-C responses so that the total HH-C response was not greater than addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 5C). Total decreases in Te on return to room air were relatively minor and similar in all groups (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

A: changes in expiratory time during a hypoxic (HX, 10% O2, 90% N2), hypercapnic (HC, 5% CO2, 21% O2, 74% N2) or hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH, 10% O2, 5% CO2, 85% N2) gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air in freely moving adult male C57BL6 mice. The maximum value ± SE recorded during acclimatization is shown. B: actual changes in expiratory time during HH gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air superimposed with the simple addition of the HX and HC (HX+HC) values and those on return to room air. C: total expiratory time (Te) responses during HX, HC, or HH challenges with the simple addition of HX and HC challenges shown for reference. The %difference between the true HH means and HX+HC means are shown. There were 16 mice in each group. The data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.5, significant response. †P < 0.5, significant response HC or HH vs. HX.

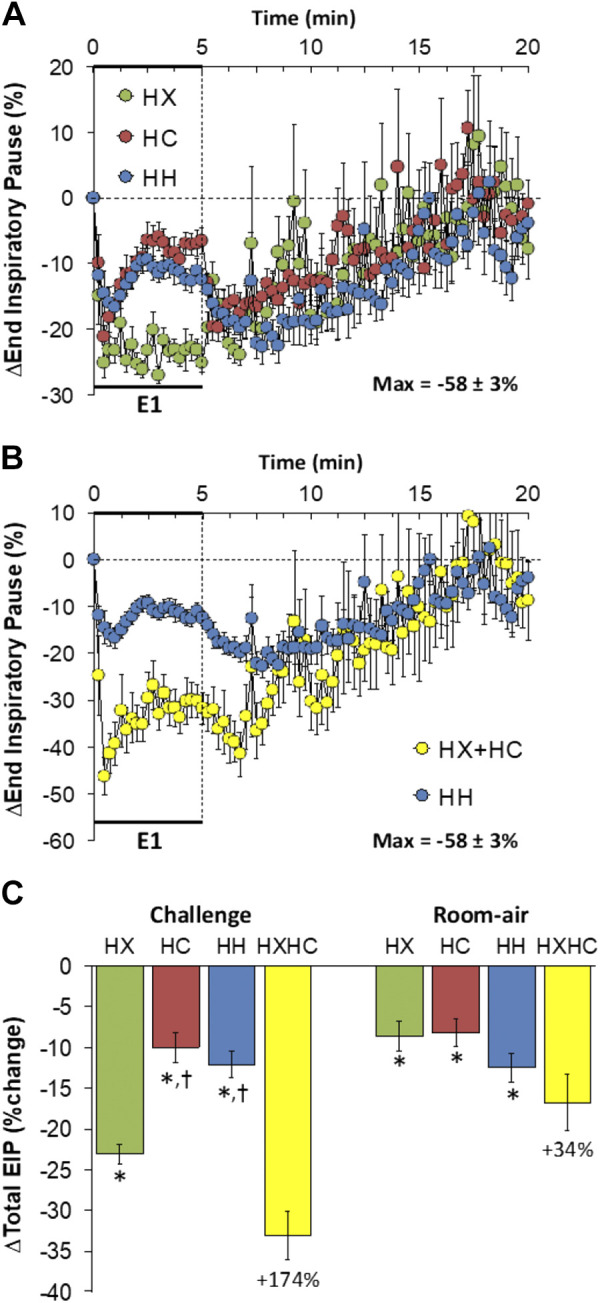

End-Inspiratory Pause

Changes in end-inspiratory pause (EIP) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C are shown in Fig. 6A. HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C elicited decreases in EIP that failed to recover to baseline during the challenges. The maximal initial responses (%change from prevalues) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C were −25 ± 2%, −21 ± 2%, and −17 ± 2%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P < 0.05, HH-C less than HX-C) and the values at the end of the HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C (5-min time-point) were −25 ± 2%, −7 ± 2%, and −13 ± 2%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P < 0.05, HX-C response greater than the HC-C or HH-C responses). Accordingly, HH-C responses were smaller than addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 6B). On return to room air, EIP fell following HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C before returning toward prechallenge levels (Fig. 6A). Responses on return to room air following HX-C and HC-C were similar to one another and the responses on return to room air were a little larger for the HH-C compared to HX-C and HC-C (Fig. 6A), and responses following HH-C were smaller than those from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 6B). Total responses during HC-C and HH-C were similar to one another; thus the total HH-C response was less than addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 6C). Total responses on return to room air following HC-C was smaller than after HX-C or HH-C and the total post-HH-C response was smaller than addition of post-HX-C and post-HC-C responses (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

A: changes in end-inspiratory pause during a hypoxic (HX, 10% O2, 90% N2), hypercapnic (HC, 5% CO2, 21% O2, 74% N2) or hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH, 10% O2, 5% CO2, 85% N2) gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air in freely moving adult male C57BL6 mice. The maximum value ± SE recorded during acclimatization is shown. B: actual changes in end-inspiratory pause during HH gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air superimposed with the simple addition of HX and HC (HX+HC) values and those on return to room air. C: total end-inspiratory pause (EIP) responses during the HX, HC, or HH challenges with simple addition of HX and HC challenges shown for reference. The %difference between the true HH means and HX+HC means are shown. There were 16 mice in each group. Data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.5, significant response. †P < 0.5, significant response HC or HH vs. HX.

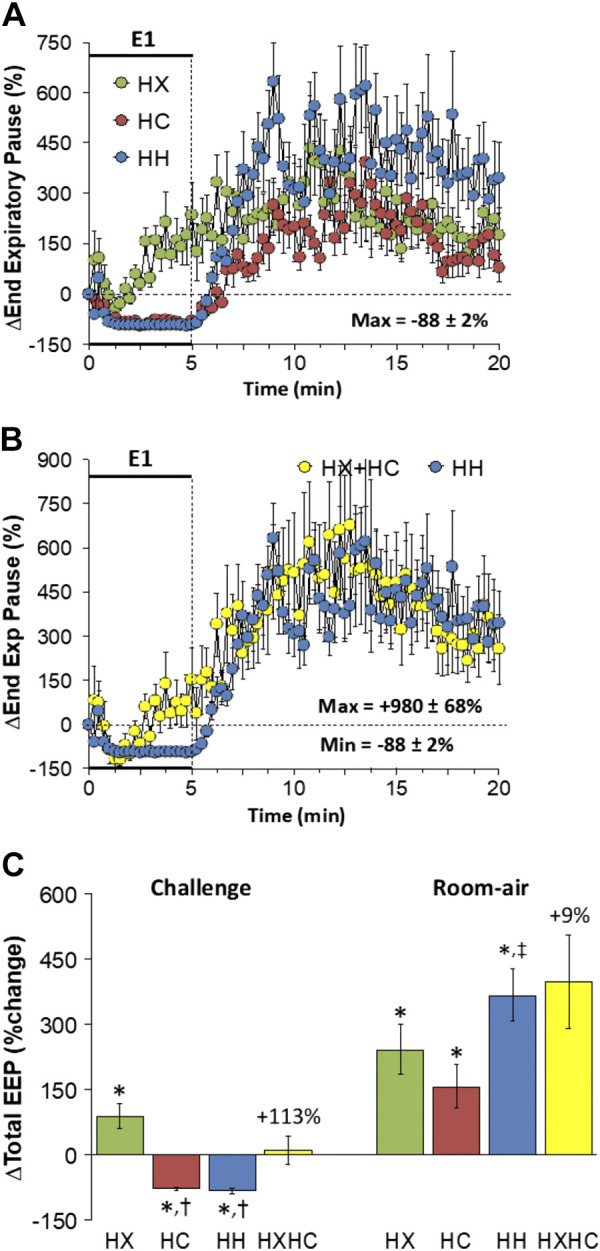

End-Expiratory Pause

Changes in end-expiratory pause (EEP) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C are shown in Fig. 7A. HX-C caused a gradual and sustained rise in EEP, whereas HC-C and HH-C elicited sustained decreases in EEP. The maximal initial responses (%change from prevalues) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C were +108 ± 38%, −33 ± 13%, and −59 ± 15%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P < 0.05, HC-C and HH-C different from HX-C) and the values at the end of the HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C (5-min time-point) were +234 ± 67%, −83 ± 13%, and −94 ± 2%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P < 0.05, HC-C and HH-C responses different from the HX-C response). As such, HH-C responses were smaller than those on addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 7B). On return to room air, EEP values were consistently above baseline after HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C (Fig. 7A). Responses after HH-C were similar to those from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 7B). Total responses during HX-C were increased over baseline, whereas those after HC-C and HH-C were decreased below baseline so that the total response arising from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses was minimal (Fig. 7C). Return to room-air responses in EEP were such that the HH-C responses were similar to summation of the HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7.

A: changes in end-expiratory pause (End Exp Pause) during a hypoxic (HX, 10% O2, 90% N2), hypercapnic (HC, 5% CO2, 21% O2, 74% N2) or hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH, 10% O2, 5% CO2, 85% N2) gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air in freely moving adult male C57BL6 mice. The maximum value ± SE recorded during acclimatization is shown. B: actual changes in End Exp Pause during HH gas challenge (E1) and on return room-air superimposed with the simple addition of HX and HC (HX+HC) values and those on return to room air. C: total end-expiratory pause (EEP) responses during HX, HC, or HH challenges with simple addition of HX and HC challenges shown for reference. The %difference between the true HH means and HX+HC means are shown. There were 16 mice in each group. The data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.5, significant response. †P < 0.5, significant response HC or HH vs. HX.

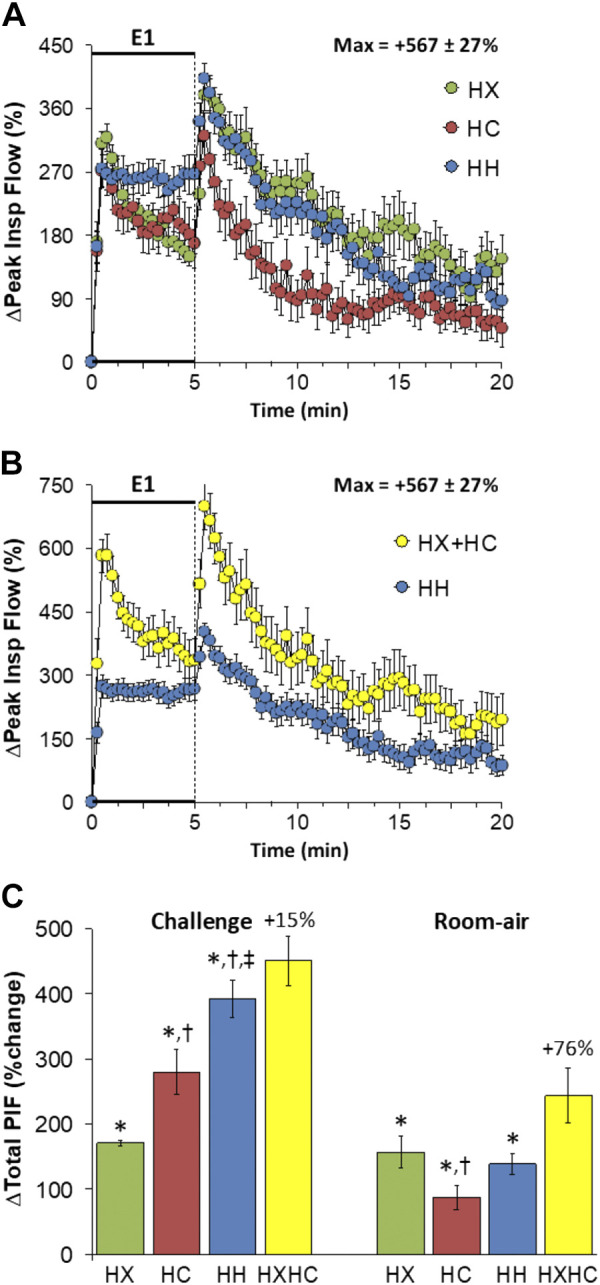

Peak Inspiratory Flow

Changes in peak inspiratory flow (PIF) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C are shown in Fig. 8A. HX-C and HC-C elicited a rise in PIF that was subject to roll-off. HH-C elicited sustained increases in PIF of similar initial magnitude to HX-C and HC-C, but which did not show roll-off. The maximal initial responses (%change from prevalues) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C were +318 ± 19%, +272 ± 23%, and +274 ± 28%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P > 0.05, no between-group differences) and the values at the end of the HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C (5-min time-point) were +169 ± 14%, +168 ± 24%, and +267 ± 28%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P < 0.05, HH-C response greater than HX-C or HC-C responses). As such, HH-C responses were less than those arising from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 8B). PIF rose initially on return to room air after HX-C, HC-C and HH-C and rapidly returned to prevalues (Fig. 8A) such that responses after HH-C were smaller than adding HX-C and HC-C responses initially, but then converged towards the end of the 15-min recovery to room air (Fig. 8B). Total responses during HH-C were greater than during HC-C, which in turn were greater than during HX-C such that the total responses during HH-C were similar to summation of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 8C). Total return to room-air responses following HC-C were smaller than during HX-C or HH-C such that increases during HH-C were smaller than addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 8C).

Figure 8.

A: changes in peak inspiratory flow (Peak Insp Flow) during a hypoxic (HX, 10% O2, 90% N2), hypercapnic (HC, 5% CO2, 21% O2, 74% N2) or hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH, 10% O2, 5% CO2, 85% N2) gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air in freely moving adult male C57BL6 mice. The maximum value ± SE recorded during acclimatization is shown. B: actual changes in peak inspiratory flow during HH gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air superimposed with the simple addition of HX and HC (HX+HC) values and those on return to room-air. C: total peak inspiratory flow (PIF) responses during the HX, HC, or HH challenges with simple addition of HX and HC challenges shown for reference. The %difference between the true HH means and HX+HC means are shown. There were 16 mice in each group. Data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.5, significant response. †P < 0.5, significant response HC or HH vs. HX. ‡P < 0.5, significant response HH vs. HC.

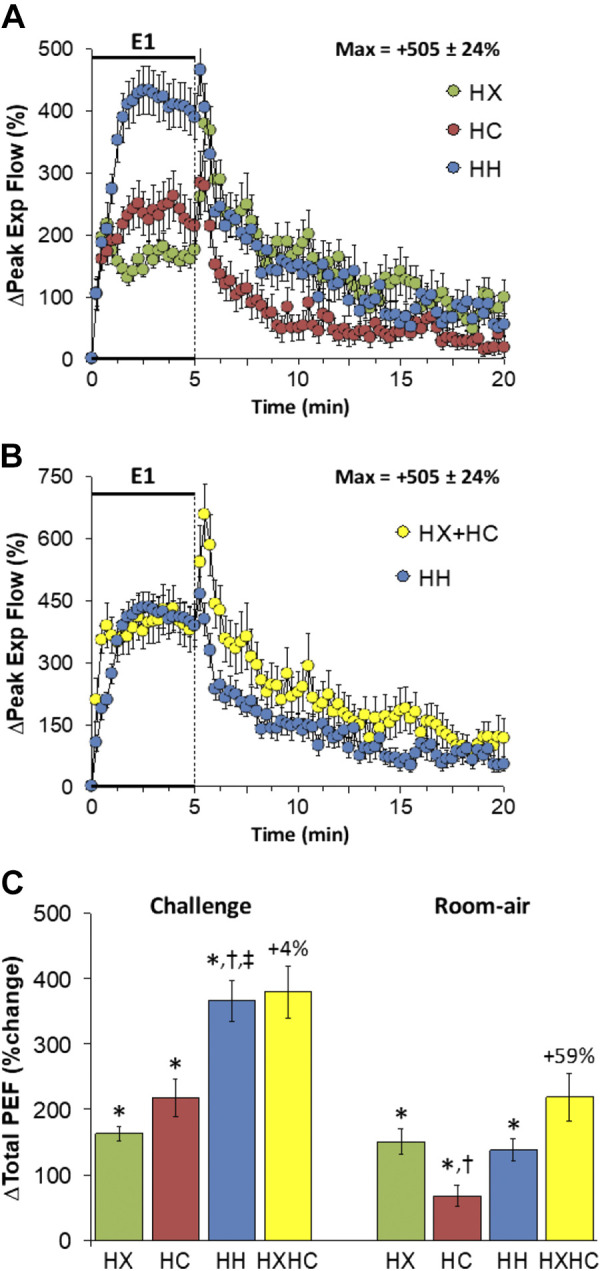

Peak Expiratory Flow

Changes in peak expiratory flow (PEF) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C are shown in Fig. 9A. HX-C and HC-C elicited sustained rises in PEF that were smaller than the sustained rises in PEF during HH-C. The maximal initial responses (%change from prevalues) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C were +217 ± 24%, +250 ± 28%, and +433 ± 39%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P < 0.05, HH-C greater than HX-C and HC-C) and the values at the end of the HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C (5-min time-point) were +175 ± 14%, +214 ± 28%, and +390 ± 37%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P < 0.05, HH-C response greater than HX-C or HC-C responses). As such, HH-C responses were similar to those arising from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 9B). PEF rose initially on return to room air after HX-C, HC-C or HH-C and then rapidly returned to prevalues (Fig. 9A) such that the responses after HH-C were similar to those arising from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 9B). Total responses during HH-C were greater than during HC-C or HX-C such that the total responses during HH-C were similar to simple addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 9C). Total return to room-air responses after HC-C were smaller than during HX-C or HH-C such that the HH-C increases were smaller than expected from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 9C).

Figure 9.

A: changes in peak expiratory flow (Peak Exp Flow) during a hypoxic (HX, 10% O2, 90% N2), hypercapnic (HC, 5% CO2, 21% O2, 74% N2) or hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH, 10% O2, 5% CO2, 85% N2) gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air in freely moving adult male C57BL6 mice. The maximum value ± SE recorded during acclimatization is shown. B: actual changes in peak expiratory flow during HH gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air superimposed with the simple addition of HX and HC (HX+HC) values and those on return to room air. C: total peak expiratory flow (PEF) responses during HX, HC, or HH challenges with simple addition of HX and HC challenges shown for reference. The %difference between the true HH means and HX+HC means are shown. There were 16 mice in each group. The data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.5, significant response. †P < 0.5, significant response HC or HH vs. HX. ‡P < 0.5, significant response HH vs. HC.

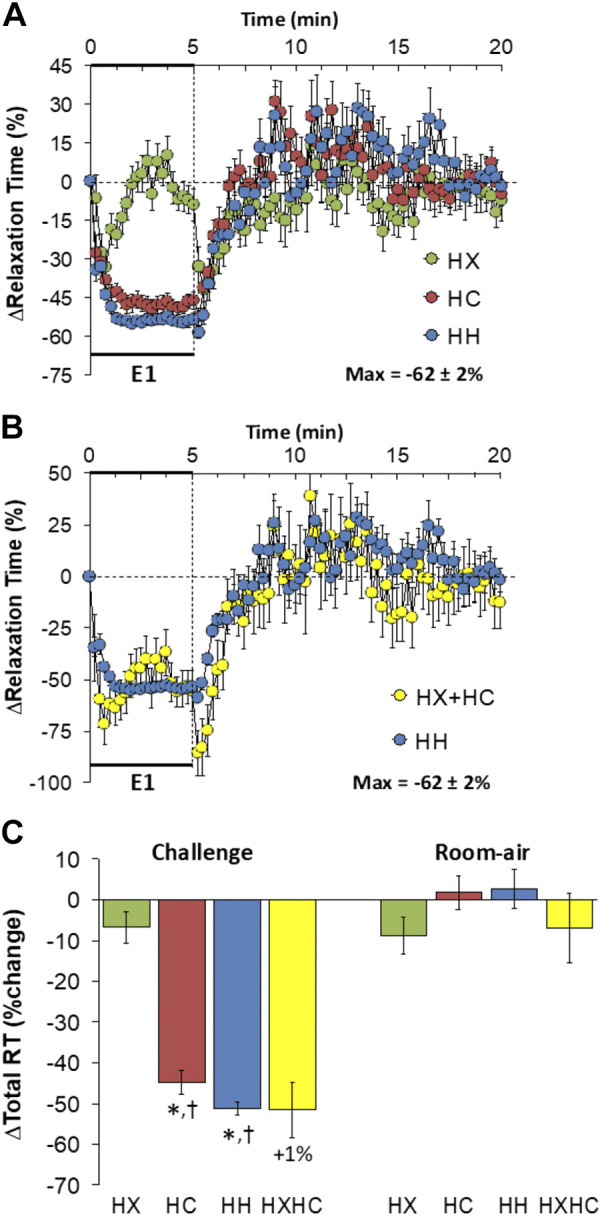

Relaxation Time

Changes in relaxation time (RT) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C are shown in Fig. 10A. HX-C elicited a transient decrease that returned to near baseline values, whereas HC-C and HH-C elicited sustained and similar falls in RT. The maximal initial responses (%change from prevalues) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C were −33 ± 6%, −38 ± 4%, and −44 ± 2%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P > 0.05, no between-group differences) and the values at the end of the HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C (5-min time-point) were −9 ± 6%, −46 ± 3%, and −54 ± 2%, respectively (P < 0.05, HC-C and HH-C responses significant; P < 0.05, HC-C and HH-C responses greater than the HX-C response). As such, HH-C responses were similar to those that arose from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 10B). RT fell markedly on return to room air after HX-C and rapidly returned to baseline in a time-course similar to the post-HC-C and post-HH-C responses (Fig. 10A) such that these responses after HH-C were similar to those arising from addition of the HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 10B). Total decreases in RT during HH-C were greater than during HX-C such that total responses during HH-C were similar to addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 10C). Total return to room-air responses following all challenges were minimal (Fig. 10C).

Figure 10.

A: changes in relaxation time during a hypoxic (HX, 10% O2, 90% N2), hypercapnic (HC, 5% CO2, 21% O2, 74% N2) or hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH, 10% O2, 5% CO2, 85% N2) gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air in freely moving adult male C57BL6 mice. The maximum value ± SE recorded during acclimatization is shown. B: actual changes in relaxation time during HH gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air superimposed with the simple addition of HX and HC (HX+HC) values and those on return to room air. C: total relaxation time (RT) responses during the HX, HC, or HH challenges with simple addition of the HX and HC challenges shown for reference. The %difference between true HH means and HX+HC means are shown. There were 16 mice in each group. The data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.5, significant response. †P < 0.5, significant response HC or HH vs. HX.

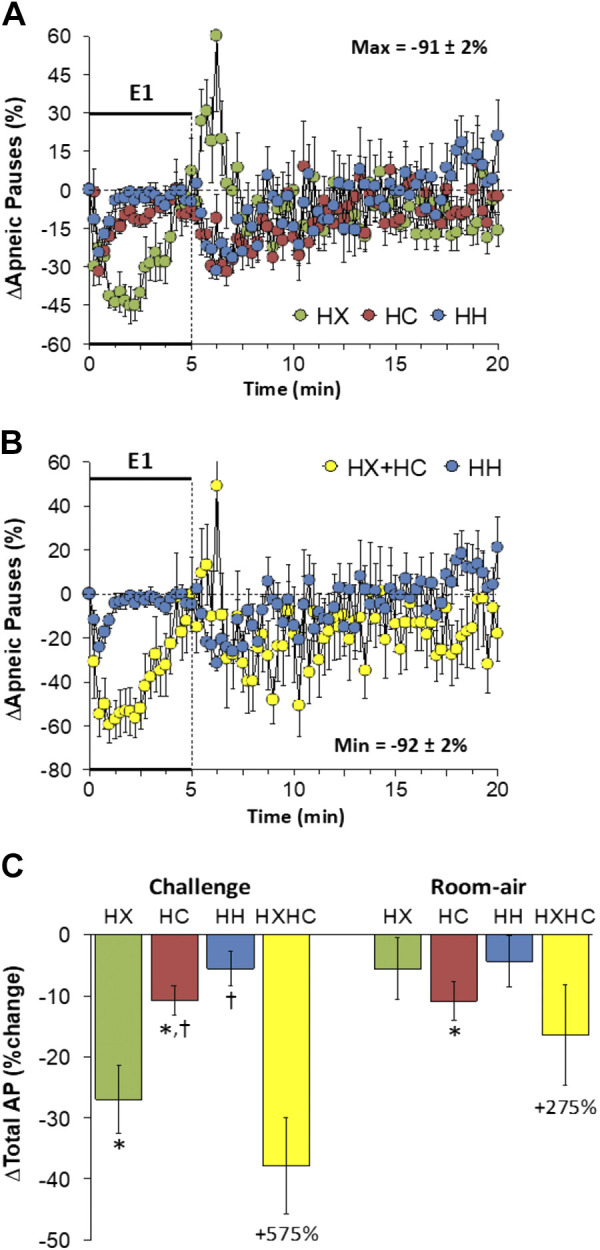

Apneic Pause

Changes in apneic pause elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C are shown in Fig. 11A. HX-C elicited a decrease in apneic pause that displayed roll-off, whereas HC-C and HH-C elicited transient decreases that quickly returned to baseline. The maximal initial responses (%change from prevalues) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C were −29 ± 7%, −31 ± 5%, and −24 ± 5%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P > 0.05, no between-group differences) and the values at the end of the HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C (5-min time-point) were +7 ± 13%, −8 ± 4%, and −5 ± 3%, respectively (P > 0.05, no significant responses; P > 0.05, no between-group differences). As such, the HH-C responses were smaller than those arising from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 11B). Apneic pause rose initially upon return to room air after HX-C but showed minimal changes post-HC-C or post-HH-C (Fig. 11A) such that the relatively minor responses after HH-C were similar to those arising from adding the HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 11B). Total decreases in apneic pause during HX-C were greater than during HC-C or HH-C such that the total responses during HH-C were smaller than those on addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 11C). Total return to room-air responses following all of the challenges were minimal (Fig. 11C).

Figure 11.

A: changes in apneic pauses during a hypoxic (HX, 10% O2, 90% N2), hypercapnic (HC, 5% CO2, 21% O2, 74% N2) or hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH, 10% O2, 5% CO2, 85% N2) gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air in freely moving adult male C57BL6 mice. The maximum value ± SE recorded during acclimatization is shown. B: actual changes in apneic pauses during HH gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air superimposed with the simple addition of HX and HC (HX+HC) values and those on return to room air. C: total apneic pause (AP) responses during HX, HC, or HH challenges with simple addition of HX and HC challenges shown for reference. The %difference between the true HH means and HX+HC means are shown. There were 16 mice in each group. The data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.5, significant response. †P < 0.5, significant response HC or HH vs. HX.

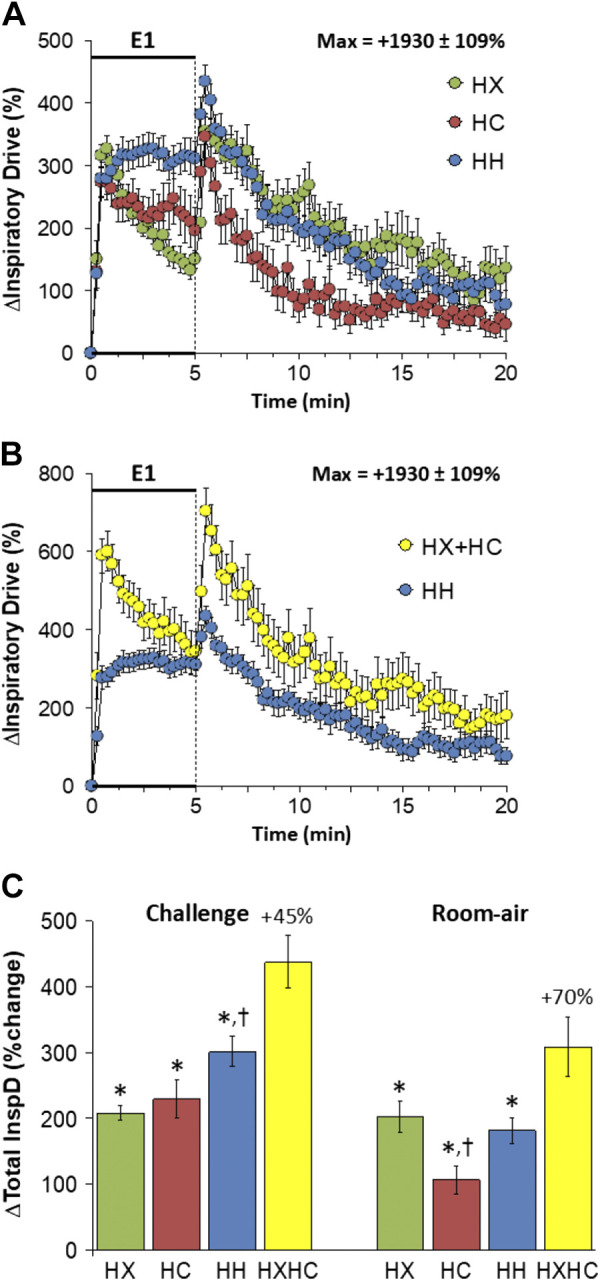

Inspiratory Drive

Changes in inspiratory drive elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C are shown in Fig. 12A. HX-C and HC-C elicited an immediate rise in inspiratory drive that was subject to roll-off. HH-C elicited sustained increases in inspiratory drive that were overall greater than during HX-C or HC-C. The maximal initial responses (%change from prevalues) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C were +325 ± 21%, +273 ± 24%, and +318 ± 28%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P > 0.05, no between-group differences) and the values at the end of the HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C (5-min time-point) were +150 ± 14%, +196 ± 36%, and +311 ± 29%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P < 0.05, HH-C response greater than HX-C or HC-C responses). As such, the HH-C responses were less than those arising from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 12B). Inspiratory drive rose on return to room air after HX-C, HC-C or HH-C and rapidly returned toward prechallenge values (Fig. 12A) such that the responses following HH-C were smaller than addition of the HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 12B). Total responses during HH-C were greater than during HX-C, but not HC-C, such that the total responses during HH-C were smaller than expected from summation of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 12C). Total return to room-air responses after HC-C were smaller than during HX-C or HH-C such that the increases during HH-C were smaller compared to addition of HX-C and HH-C responses (Fig. 12C).

Figure 12.

A: changes in inspiratory drive during a hypoxic (HX, 10% O2, 90% N2), hypercapnic (HC, 5% CO2, 21% O2, 74% N2) or hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH, 10% O2, 5% CO2, 85% N2) gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air in freely moving adult male C57BL6 mice. The maximum value ± SE recorded during acclimatization is shown. B: actual changes in inspiratory drive during HH gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air superimposed with the simple addition of the HX and HC (HX+HC) values and those on return to room air. C: total inspiratory drive (InspD) responses during the HX, HC, or HH challenges with simple addition of HX and HC challenges shown for reference. The %difference between the true HH means and HX+HC means are shown. There were 16 mice in each group. The data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.5, significant response. †P < 0.5, significant response HC or HH vs. HX.

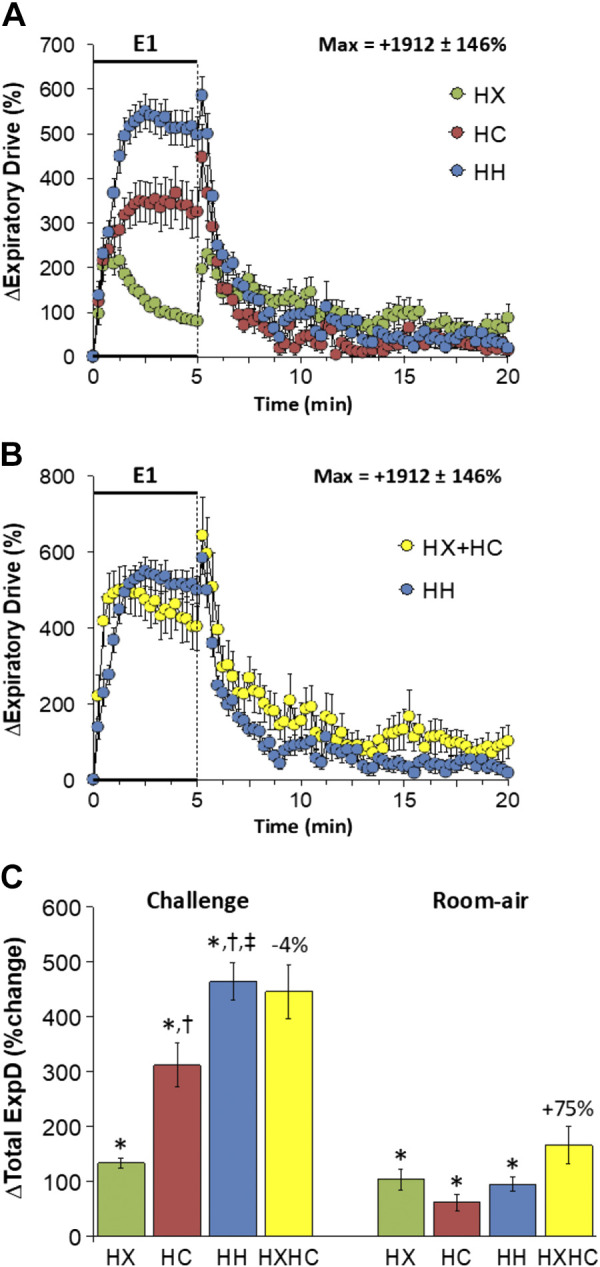

Expiratory Drive

Changes in expiratory drive elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C are shown in Fig. 13A. We are confident that inspiration and therefore inspiratory drive in C57BL6 mice are active processes at rest and during HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C; we are less sure whether expiration and therefore expiratory drive are active or passive processes at rest in these mice. Nonetheless, we are confident that both processes are active during HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C. HX-C elicited an immediate rise in expiratory drive that was subject to roll-off. HC-C and HH-C elicited sustained increases in expiratory drive with the responses being greater during HH-C than HC-C. The maximal initial responses (%change from prevalues) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C were +239 ± 33%, +282 ± 38%, and +493 ± 41%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P < 0.05, HH-C response greater than HX-C or HC-C responses) and the values at the end of the HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C (5-min time-point) were +79 ± 6%, +324 ± 55%, and +497 ± 40%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P < 0.05, HC-C response greater than HX-C response, HH-C response greater than HX-C or HC-C responses). As such, the HH-C responses were similar to addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 13B). Expiratory drive rose initially on return to room air after the challenges and rapidly returned to prevalues (Fig. 13A) such that the responses following HH-C were similar to those that arose from addition of the HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 13B). Total responses during HH-C were greater than during HC-C, which in turn were greater than those during HX-C such that the total HH-C responses were similar to summation of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 13C). Total return to room-air responses were minor in all groups with the increase during HH-C being somewhat smaller than addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 13C).

Figure 13.

A: changes in expiratory drive during a hypoxic (HX, 10% O2, 90% N2), hypercapnic (HC, 5% CO2, 21% O2, 74% N2) or hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH, 10% O2, 5% CO2, 85% N2) gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air in freely moving adult male C57BL6 mice. The maximum value ± SE recorded during acclimatization is shown. B: actual changes in expiratory drive during HH gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air superimposed with the simple addition HX and HC (HX+HC) values and those on return to room air. C: total expiratory drive (ExpD) responses during the HX, HC, or HH challenges with simple addition of HX and HC challenges shown for reference. The %difference between the true HH means and HX+HC means are shown. There were 16 mice in each group. The data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.5, significant response. †P < 0.5, significant response HC or HH vs. HX. ‡P < 0.5, significant response HH vs. HC.

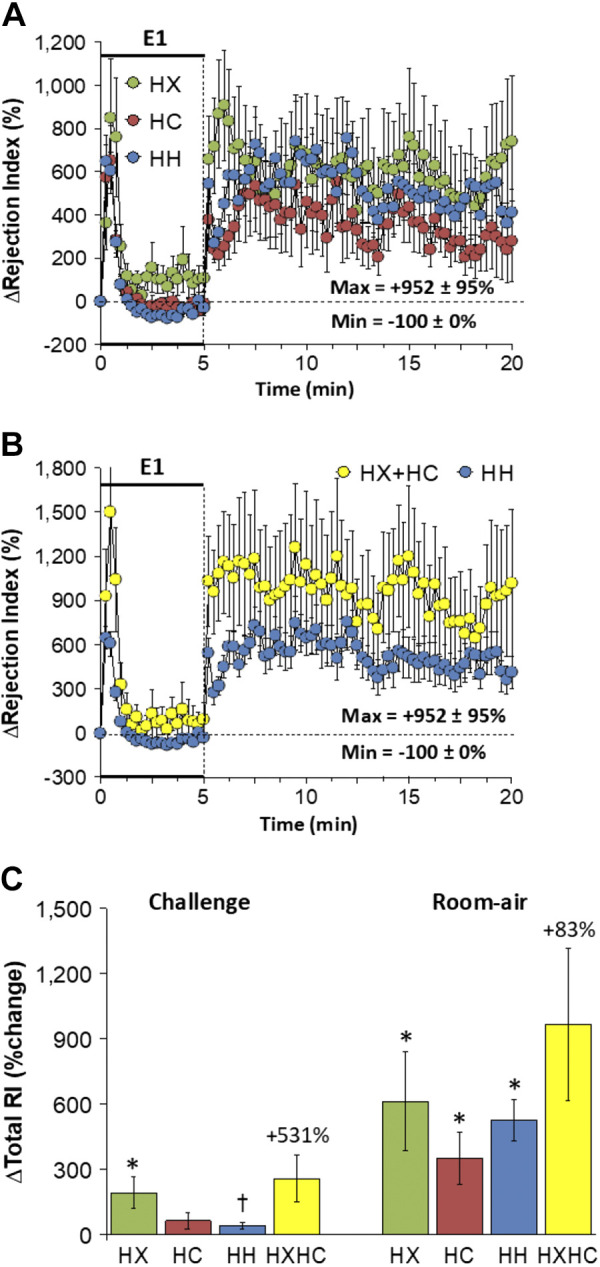

Rejection Index

Changes in rejection index elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C are shown in Fig. 14A. The HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C caused transient and similar increases rejection index that returned to baseline values within 90 s. The maximal initial responses (%change from prevalues) elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C were +847 ± 176%, +653 ± 158%, and +646 ± 76%, respectively (P < 0.05, all responses significant; P > 0.05, no between-group differences) and the values at the end of the HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C (5-min time-point) were +107 ± 38%, −14 ± 34%, and −31 ± 26%, respectively (P < 0.05, HX-C response only significant from prevalues; P < 0.05, HX-C response different from the HX-C or HC-C responses). As such, HH-C responses were smaller and more transient than those from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 14B). Rejection index values rose on return to room air after HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C (Fig. 14A). The overall increases in rejection index were similar in HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C groups with HH-C responses being smaller than summation of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 14C). The total return to room-air responses were similar in HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C groups with the total responses in the HH-C group being somewhat smaller than summation of the HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 14C).

Figure 14.

A: changes in rejection index during a hypoxic (HX, 10% O2, 90% N2), hypercapnic (HC, 5% CO2, 21% O2, 74% N2) or hypoxic-hypercapnic (HH, 10% O2, 5% CO2, 85% N2) gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air in freely moving adult male C57BL6 mice. The maximum value ± SE recorded during acclimatization is shown. B: actual changes in rejection index during HH gas challenge (E1) and on return to room air superimposed with the simple addition of HX and HC (HX+HC) values and those on return to room air. C: total rejection index (RI) responses during HX, HC, or HH challenges with simple addition of HX and HC challenges shown for reference. The %difference between true HH means and HX+HC means are shown. There were 16 mice in each group. The data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.5, significant response. †P < 0.5, significant response HC or HH vs. HX.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates complex interactions between signaling pathways that elicit ventilatory responses to HX-C and HC-C in C57BL6 mice. We have reported that exposure to HX, HC, or HH challenges and return to room air following these challenges are associated with only minor behavioral responses in naïve C57BL6 mice (61). As such, it is likely that the differences in ventilatory responses seen during HX, HC, and HH challenges and return to room air in the present study reflects true interactions between central and peripheral ventilatory signaling processes. Moreover, with respect to the potential influence of changes in body temperature during the gas challenges, we have reported that the relatively short (5 min) HX and HC challenges elicit only minor changes (maximum changes of −0.4°C and less than ± 0.10°C) in body temperature in C57BL6 mice (103, 104) and have preliminary data that the maximal change in body temperature of C57BL6 mice (n = 16) during a HH-C challenge is also negligible (−0.08 ± 0.05°C, P > 0.05). Hypoadditive and additive, but not hyperadditive, interactions were seen in the present study. These interactions were obvious during plateau response phases rather than initial phases (first 60 s). HX-C elicited an increase in fr subject to pronounced roll-off (57–61, 73) and HC-C elicited a pronounced increase in fr that was sustained (61, 67). A key finding was that HC-C elicited similar increases in fr to those of HH-C showing that exposure to hypercapnia prevents roll-off to HX-C when given simultaneously. The initial responses to HX-C involve activation of carotid body chemoreceptor afferent input to the NTS (1–7) that enhances glutamate release and activation of glutamate N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors (105–107), which recruit neuronal nitric oxide synthase (NOS), protein kinase C, tyrosine kinases and kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase 2 (108–114). Mechanisms underlying ventilatory roll-off during HX-C involve GABA, adenosine, dopamine, platelet-derived growth factor, S-nitrosoglutathione reductase and site-selective intracellular acidification due to lactate-induced down-regulation of NMDA receptors (58, 115–121). HC-C activation of signaling pathways in the retrotrapezoid nuclei (30–34) may interfere with signaling events that cause roll-off. A key finding was that the maximal (plateau) increase in fr elicited by HH-C was equal to the HC-C response and far less than from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 1). As such, the second conclusion is that there is hypoadditive cooperativity between HX-C and HC-C signaling pathways controlling fr. Since neurotransmitter release from carotid sinus chemoafferents to brainstem neurons would be activated by HX-C or HC-C this negative cooperativity would reside within central pathways. We have not performed the present studies in C57BL6 mice with bilateral CSNX, but have in juvenile (P25) Sprague–Dawley rats (122). In sham-operated rats, HH-C responses were equal to those from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses and although HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C responses were smaller in CSNX rats, the HH-C response was additive of HX-C and HC-C responses. Clearly, the mechanisms by which HX-C and HC-C signaling mechanisms interact are different in adult C57BL6 mice than in juvenile rats.

In contrast to fr, the robust increases in Vt elicited by HX-C and HC-C were not subject to roll-off and the greatly enhanced HH-C increases in Vt were similar to those by arithmetic addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 2). This suggests that the carotid body-chemoafferent-brainstem systems that respond to HX-C and HC-C to modulate Vt do not interact or influence one another. This additive relationship between HX-C and HC-C signaling pathways for Vt was seen in sham-operated juvenile (P25) Sprague–Dawley rats (109). The HH-C Vt response in juvenile CSNX rats was much less than expected from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (122). These latter findings support evidence that central and peripheral chemoreceptive systems interact with one another (36–38) and that input of peripheral carotid sinus chemoreceptors determine the respiratory sensitivity of central chemoreceptors to CO2 (39). Whether the additive nature of Vt responses to HX-C and HC-C are modified in C57BL6 CSNX mice is an open question. Differences between the responses elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C were most clearly defined by the increases in V̇e in which the HX-C response consisted of an initial rise subject to roll-off, the HC-C response consisted of a sustained rise that did not show roll-off, and the HH-C response was greater in magnitude than both the HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 3). As such, the HH-C responses were almost identical to that of simple addition of the HX-C and HC-C responses minus the initial 90 s where roll-off was present in the HX-C. Again, this additive relationship was observed in sham-operated juvenile rats and although the responses to HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C were reduced in juvenile CSNX rats, the additive relationship persisted (109). It remains to be established why interactions between HX-C and HC-C signaling events in C57BL6 mice differ so markedly, and it is imperative to establish what these relationships are like in other mouse strains (79, 82, 85–91) to gain understanding of the genetics underlying these relationships.

The decreases in Ti and Te associated with the HX-C-induced increases in breathing showed remarkable differences (Figs. 4 and 5). The decreases in Ti elicited by HX-C, HC-C and HH-C were similar to one another and showed similar roll-off so that the decreases in Ti elicited by HH-C were markedly less than what expected from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses. It is evident that HX-C and HC-C pathways regulating Ti negatively interact with one another. In contrast, decreases in Te during HX-C showed early and substantial roll-off, whereas the robust decreases in Te elicited by HC-C and HH-C were very similar to one another and were not subject to roll-off. As such, the early phase of the Te response to HH-C was less than from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses. The finding that roll-off in Te occurred during HX-C, but not HC-C or HH-C, clearly suggests that HC-C signaling pathways influence HX-C pathways that control Te. Obviously, the negative interaction between HX-C and HC-C pathways controlling Ti, and dominance of HC-C signaling over HX-C signaling pathways regulating Te suggests involvement of different neural and neurochemical systems in these control pathways. The above conclusions related to control of inspiratory and expiratory processes are extended by our findings with EIP and EEP (Figs. 6 and 7). HX-C elicited pronounced and sustained decreases in EIP, whereas HC-C and HH-C elicited much smaller decreases that were similar to one another and subject to roll-off so that the decreases in EIP elicited by HH-C were markedly less than expected from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses. It is clear that HC-C signaling processes influence HX-C pathways controlling EIP. It appears that interactions between HX-C and HC-C signaling events that control EIP (i.e., the pause before starting expiration) and those controlling Te are similar to one another. EEP gradually rose during HX-C, whereas EEP fell below baseline HC-C and HH-C such that the decreases in EEP were greater than expected from adding the HX-C and HC-C responses. The finding that HC-C signaling processes influence HX-C pathways controlling EIP and EEP suggest that unlike differential control of Ti, these pathways share common neural/neurochemical systems.

HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C produced robust increases in PIF (Fig. 8). The pronounced roll-off during HX-C and HC-C did not occur during HH-C, such that HH-C responses were much smaller than the addition of HX-C and HC-C responses. The hypoxic and hypercapnic signaling pathways activated during HH-C combined to prevent the roll-off that occurs under HX-C or HC-C alone, which represents a rare case where the similar temporal nature of responses elicited by HX-C and HC-C are markedly different when concomitantly applied. Despite the interactions, HX-C and HC-C signaling pathways dampened the overall response such that the HH-C response was smaller than expected. The increases in PEF elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C were not subject to roll-off and responses elicited during HH-C were similar to those from addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 9). It appears that neural/neurochemical mechanisms underlying interactions between HX-C and HC-C pathways controlling PIF are more complicated than those controlling PEF. Changes in relaxation time exemplify how HC-C signaling pathways exert greater responses than HX-C signaling pathways (Fig. 10). Although HX-C elicited a transient decrease in relaxation time, HC-C and HH-C elicited robust and sustained decreases such that HH-C responses were similar to addition of HX-C and HC-C responses. Decreases in apneic pause are also an example in which HX-C decreased apneic pause, whereas HC-C and HH-C elicited transient decreases such that the decrease in apneic pause during HH-C was less than addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 11). The increases in inspiratory drive following HX-C and HC-C displayed roll-off, whereas those during HH-C did not, and the similar amplitude of the responses resulted in HH-C responses that were less than addition of HX-C and HC-C responses (Fig. 12). Negative cooperativity was not seen with expiratory drive (Fig. 13). HX-C-induced increases in expiratory drive displayed roll-off, whereas the HC-C increases were larger and not subject to roll-off. The increases in expiratory drive elicited by HH-C were greater than of HX-C or HC-C such that HH-C responses were similar to addition of HX-C and HC-C responses. Negative cooperativity between HX-C and HC-C signaling pathways controlling inspiratory but not expiratory drive points to differential interactions between ventilatory control pathways.

The return to room-air responses following HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C were subject to some hypoadditive interactions. Changes in fR (Fig. 1), Ti (Fig. 4), EIP (Fig. 6), PIF (Fig. 8), PEF (initial moments, Fig. 9), Relaxation time (initial moments, Fig. 10) and inspiratory drive (Fig. 12) on return to room air were substantially less than expected from addition of the return to room-air responses following HX-C and HC-C. In contrast, changes in Vt (Fig. 2), V̇e (Fig. 3), EEP (Fig. 7), apneic pause (Fig. 11), expiratory drive (Fig. 13) and rejection index (Fig. 14) on return to room air following HH-C were equivalent to those expected from addition of return to room-air responses following HX-C and HC-C. The return to room-air responses may result from interaction of room air (O2) with signaling cascades elicited by HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C (60, 61, 69–73). Ventilatory responses following HX-C (60) and HC-C (67) are virtually absent in male CSNX mice. In addition, the return to room-air responses following HX-C were markedly altered in C57BL6 mice with bilateral transection of the cervical sympathetic chain (73) or bilateral removal of the superior cervical ganglia (123) suggesting that reduced sympathetic input to the carotid bodies plays a role in post-HX-C responses (73, 123). Previously, we reported that the short-term facilitation of breathing on cessation of HX-C (103) or HC-C (104) is impaired in male but not in female endothelial NOS knockout mice. The above hypoadditive interactions may have resulted from altered signaling/neurochemical mechanisms in the carotid bodies and these altered mechanisms may involve changes in sympathetic input and NOS activity. In summary, our data demonstrates that HX-C and HC-C signaling pathways in C57BL6 male mice interact with one another in both additive and often hypoadditive processes, whereas hyperadditive events were not observed. These findings compliment data in other species of experimental animals in which all three interactive processes have been uncovered (36–39) and also in numerous human studies in which peripheral and central chemoreflexes have been reported to display hypoadditive (40, 41), additive (42, 43), or hyperadditive (44, 45) effects on ventilation. Our studies in mice therefore add some degree of support to the findings in humans and other experimental animals, and future studies will allow for analyses of the responses in female C57BL6 mice, whose ventilatory responses to HX challenges are substantially different to those of male C57BL6 mice (56–59). Moreover, future studies in C57BL6 mice in which genetic encoding for key functional proteins, such as nitric oxide synthase (54–56, 103, 104), have been eliminated, will help to determine the potential signaling mechanisms that participate in the interactions between HX and HC signaling. There are several important limitations of the present study. More specifically, only male C57BL6 mice were used and follow-up studies in female C57BL6 mice, and male and female mice of other strains are needed to build on our understanding of the interactions between HX and HC signaling pathways, as are measurements of body temperature/metabolism and arterial blood-gas chemistry. Future studies will address the responses of individual C57BL6 mice to randomized HX, HC, and HH challenges in exposure paradigms where the spacing of the challenges does not have lingering effects on one another. Such studies may provide evidence to support the present findings regarding the interactions between HX and HC signaling processes in C57BL6 mice.

In conclusion, this study provides evidence that HX-C and HC-C in C57BL6 mice activate neural/neurochemical systems that interact in an additive (i.e., Vt, V̇e, expiratory drive, PEF, and rejection index) and hypoadditive (i.e., fr, Ti, Te, EIP, PIF, and inspiratory drive) fashion, and that HC-C signaling influences HX-C signaling systems for EEP, relaxation time and apneic pause (Table 3). The increase in ventilation during the HX-C (10% O2, 90% N2) would be expected to lower blood pCO2 concentrations, which would thereby act as a break on the hypoxic ventilatory response (81). Our data are even more perplexing in this context since adding the HX-C responses (which would lower arterial blood CO2 concentrations and act as a break on the ventilatory responses to HX challenge) to the HC-C responses would be expected to be superadditive, but they were not for any parameter. We are preparing to repeat these experiments using isocapnic HX gas challenges (e.g., 10% O2, 3.5% CO2, 86.5% N2), which have been shown to prevent hypoxic gas-induced decreases in blood pCO2 (124). In parallel studies, we have addressed the ventilatory responses elicited by opioids, such as fentanyl (125–128) and morphine (129–135), in rats and how morphine affects ventilatory responses to HX-C and HH-C (130, 131). We performed the present studies in C57BL6 mice to provide data needed to better understand findings from ongoing studies determining how fentanyl and morphine affect ventilatory responses to HX-C, HC-C, and HH-C in C57BL6 mice and whether opioids affect the interactions between hypoxic and hypercapnic signaling pathways.

Table 3.

Changes during HX-C, HC-C, HH-C, and theoretical HX+HC gas challenges

| Parameter | HX-C | HC-C vs. HX-C | HH-C vs. HX-C | HH-C vs. HC-C | HX+HC vs. HH-C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | ↑ | greater ↑ | greater ↑ | equal ↑ | greater ↑ |

| Tidal volume | ↑ | greater ↑ | greater ↑ | greater ↑ | equal ↑ |

| Minute volume | ↑ | greater ↑ | greater ↑ | greater ↑ | equal ↑ |

| Inspiratory time | ↓ | equal ↓ | equal ↓ | equal ↓ | greater ↓ |

| Expiratory time | ↓ | greater ↓ | greater ↓ | equal ↓ | equal ↓ |

| End-inspiratory pause | ↓ | lesser ↓ | lesser ↓ | equal ↓ | greater ↓ |

| End-expiratory pause | ↑ | changed to ↓ | changed to ↓ | equal ↓ | no ↑ |

| Relaxation time | ↓ns | greater ↓ | greater ↓ | equal ↓ | equal ↓ |

| Peak inspiratory flow | ↑ | greater ↑ | greater ↑ | greater ↑ | equal ↑ |

| Peak expiratory flow | ↑ | equal ↑ | greater ↑ | greater ↑ | equal ↑ |

| Inspiratory drive | ↑ | equal ↑ | greater ↑ | equal ↑ | greater ↑ |

| Expiratory drive | ↑ | greater ↑ | greater ↑ | greater ↑ | equal ↑ |

| Rejection index | ↑ | lesser ↑ | lesser ↑ | equal ↑ | greater ↑ |

| Apnea index | ↓ | lesser ↓ | lesser ↓ | equal ↓ | greater ↓ |

The arrows denote the direction of change elicited by the challenges (arrows imply a significant response). The word associated with each arrow denotes whether the responses elicited by a challenge are greater, lesser or equal to another. HX-C, hypoxic gas challenge. HC-C, hypercapnic gas challenge; HH-C, hypoxic-hypercapnic gas challenge; HX + HC, addition of HX-C and HC-C gas challenges; ns, not significant.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Case Western Reserve University reviewed and provided official approval for the studies presented in this manuscript.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support this study are available on e-mail request to Paulina M. Getsy (pxg55@case.edu) or Stephen J. Lewis (sjl78@case.edu).

GRANTS

This was funded in part by National Institutes of Health-Stimulating Peripheral Activity to Relieve Conditions (SPARC) Award 10T2OD023860 (Functional Mapping of the Afferent and Efferent Projections of the Superior Cervical Ganglion Interactome) to S.J.L.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

P.M.G. and S.J.L. conceived and designed research; J.D. and G.A.C. performed experiments; P.M.G., T.H.J.L., and S.J.L. analyzed data; P.M.G., T.H.J.L., and S.J.L. interpreted results of experiments; P.M.G., T.H.J.L., and S.J.L. prepared figures; P.M.G. and S.J.L. drafted manuscript; P.M.G. and S.J.L. edited and revised manuscript; P.M.G. and S.J.L. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Peter MacFarlane (Department of Pediatrics, Case Western Reserve University) and Dr. James N. Bates (Department of Anesthesia, University of Iowa) for assistance with the clinical perspectives associated with the findings and constructive comments about the original and revised versions of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. O'Regan RG, Majcherczyk S. Role of peripheral chemoreceptors and central chemosensitivity in the regulation of respiration and circulation. J Exp Biol 100: 23–40, 1982. doi: 10.1242/jeb.100.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lahiri S, Forster RE 2nd.. CO2/H+ sensing: peripheral and central chemoreception. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 35: 1413–1435, 2003. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(03)00050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lahiri S, Roy A, Baby SM, Hoshi T, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Oxygen sensing in the body. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 91: 249–286, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Forster HV, Smith CA. Contributions of central and peripheral chemoreceptors to the ventilatory response to CO2/H+. J Appl Physiol (1985) 108: 989–994, 2010. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01059.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wilson RJ, Teppema J. Integration of central and peripheral respiratory chemoreflexes. Compr Physiol 6: 1005–1041, 2016. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gonzalez C, Almaraz L, Obeso A, Rigual R. Carotid body chemoreceptors: from natural stimuli to sensory discharges. Physiol Rev 74: 829–898, 1994. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.4.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eyzaguirre C, Zapata P. Perspectives in carotid body research. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 57: 931–957, 1984. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.57.4.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kikuta S, Iwanaga J, Kusukawa J, Tubbs RS. Carotid sinus nerve: a comprehensive review of its anatomy, variations, pathology, and clinical applications. World Neurosurg 127: 370–374, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peers C, Buckler KJ. Transduction of chemostimuli by the type I carotid body cell. J Membr Biol 144: 1–9, 1995. doi: 10.1007/bf00238411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Prabhakar NR. Oxygen sensing by the carotid body chemoreceptors. J Appl Physiol (1985) 88: 2287–2295, 2000. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.6.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Teppema LJ, Dahan A. The ventilatory response to hypoxia in mammals: mechanisms, measurement, and analysis. Physiol Rev 90: 675–754, 2010. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kumar P, Prabhakar NR. Peripheral chemoreceptors: function and plasticity of the carotid body. Compr Physiol 2: 141–219, 2012. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tse A, Yan L, Lee AK, Tse FW. Autocrine and paracrine actions of ATP in rat carotid body. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 90: 705–711, 2012. doi: 10.1139/y2012-054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Iturriaga R, Alcayaga J. Neurotransmission in the carotid body: transmitters and modulators between glomus cells and petrosal ganglion nerve terminals. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 47: 46–53, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bairam A, Carroll JL. Neurotransmitters in carotid body development. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 149: 217–232, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eyzaguirre C. Chemical and electric transmission in the carotid body chemoreceptor complex. Biol Res 38: 341–345, 2005. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602005000400005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nurse CA. Neurotransmission and neuromodulation in the chemosensory carotid body. Auton Neurosci 120: 1–9, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Prabhakar NR. O2 sensing at the mammalian carotid body: why multiple O2 sensors and multiple transmitters? Exp Physiol 91: 17–23, 2006. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.031922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nurse CA, Piskuric NA. Signal processing at mammalian carotid body chemoreceptors. Semin Cell Dev Biol 24: 22–30, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Conde SV, Monteiro EC, Sacramento JF. Purines and carotid body: new roles in pathological conditions. Front Pharmacol 8: 913, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leonard EM, Salman S, Nurse CA. Sensory processing and integration at the carotid body tripartite synapse: neurotransmitter functions and effects of chronic hypoxia. Front Physiol 9: 225, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Prabhakar NR, Peng YJ, Nanduri J. Recent advances in understanding the physiology of hypoxic sensing by the carotid body. F1000Res 7: F1000 Faculty Rev-1900, 2018. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.16247.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Prabhakar NR, Peng YJ, Yuan G, Nanduri J. Reactive oxygen radicals and gaseous transmitters in carotid body activation by intermittent hypoxia. Cell Tissue Res 372: 427–431, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s00441-018-2807-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Forster RE 2nd. Carbonic anhydrase and the carotid body. Adv Exp Med Biol 337: 137–147, 1993. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2966-8_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Iturriaga R. Carotid body chemoreception: the importance of CO2-HCO3− and carbonic anhydrase. Biol Res 26: 319–329, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Blain GM, Smith CA, Henderson KS, Dempsey JA. Peripheral chemoreceptors determine the respiratory sensitivity of central chemoreceptors to CO2. J Physiol 588: 2455–2471, 2010. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.187211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nurse CA. Neurotransmitter and neuromodulatory mechanisms at peripheral arterial chemoreceptors. Exp Physiol 95: 657–667, 2010. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2009.049312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nattie E. CO2, brainstem chemoreceptors and breathing. Prog Neurobiol 59: 299–331, 1999. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Putnam RW, Filosa JA, Ritucci NA. Cellular mechanisms involved in CO2 and acid signaling in chemosensitive neurons. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 287: C1493–C1526, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00282.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guyenet PG. The 2008 Carl Ludwig Lecture: retrotrapezoid nucleus, CO2 homeostasis, and breathing automaticity. J Appl Physiol (1985) 105: 404–416, 2008. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90452.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guyenet PG, Stornetta RL, Bayliss DA. Retrotrapezoid nucleus and central chemoreception. J Physiol 586: 2043–2048, 2008. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.150870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Guyenet PG, Stornetta RL, Bayliss DA. Central respiratory chemoreception. J Comp Neurol 518: 3883–3906, 2010. doi: 10.1002/cne.22435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Guyenet PG, Stornetta RL, Abbott SB, Depuy SD, Kanbar R. The retrotrapezoid nucleus and breathing. Adv Exp Med Biol 758: 115–122, 2012. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-4584-1_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Guyenet PG, Bayliss DA. Neural control of breathing and CO2 homeostasis. Neuron 87: 946–961, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cummins EP, Strowitzki MJ, Taylor CT. Mechanisms and consequences of oxygen and carbon dioxide sensing in mammals. Physiol Rev 100: 463–488, 2020. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]