Abstract

Objective:

Test the hypothesis that a higher level of purpose in life is associated with an older age of Alzheimer’s dementia onset and later mortality.

Design:

Prospective cohort studies of aging and Alzheimer’s dementia.

Setting:

Community-based.

Participants:

2,558 older adults initially free of dementia underwent assessments of purpose in life and detailed annual clinical evaluations to document incident Alzheimer’s dementia and mortality. General accelerated failure time models examined the relation of baseline purpose in life with age at Alzheimer’s dementia diagnosis and mortality.

Exposures:

Purpose in life was assessed at baseline.

Main Outcomes:

Alzheimer’s dementia diagnosis was documented annually based on detailed clinical evaluations and mortality was documented via regular contacts and annual evaluations.

Results:

During a mean of 6.89 years of follow-up, 520 individuals were diagnosed with incident Alzheimer’s dementia at a mean age of 88 (SD = 6.7; range: 64.1 to 106.5). They had a mean baseline level of purpose in life of 3.7 (SD = 0.47; range: 1 to 5). A higher level of purpose in life was associated with a considerably later age of dementia onset (estimate = 0.044; 95% CI: 0.023, 0.065); specifically, individuals with high purpose (90th percentile) developed Alzheimer’s dementia at a mean age of about 95 compared to a mean age of about 89 for individuals with low purpose (10th percentile). Further, the estimated mean age of death was about 89 for individuals with high purpose compared to 85 for those with low purpose. Results persisted after controlling for sex and education.

Conclusions and relevance:

Purpose in life delays dementia onset and mortality by several years. Interventions to increase purpose in life among older persons may increase healthspan and offer considerable public health benefit.

Keywords: purpose in life, Alzheimer’s, cognitive aging, dementia, mortality

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s dementia poses a formidable public health challenge, with more than 5 million persons in the United States and 50 million worldwide currently affected, and these numbers will increase dramatically in the coming years1–3. The associated costs are staggering, exceeding $300 billion in the US and $1 trillion worldwide1. As disease-modifying therapies have yet to be developed, identification of modifiable risk factors for dementia and related health outcomes offers an important preventative strategy. One of the most robust modifiable risk factors for Alzheimer’s dementia is purpose in life, the sense that one’s life is meaningful and their behaviors goal directed4,5. Purpose in life is associated with a substantially reduced risk of developing Alzheimer’s dementia, as well as mortality5–8. Thus, purpose in life may delay the onset of Alzheimer’s dementia and confer additional years of life; however, no prior studies have estimated the number of dementia-free years or the specific longevity benefit associated with a high level of purpose in life.

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that purpose in life is associated with a later age of onset of Alzheimer’s dementia and mortality among community dwelling older persons from the Rush Memory and Aging Project and the Minority Aging Research Study9,10. Participants completed assessments of purpose in life and underwent detailed annual clinical evaluations to document incident Alzheimer’s dementia and mortality. General accelerated failure time models were used to examine the associations of baseline purpose with the subsequent age of dementia onset and mortality.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were from 2 longitudinal epidemiologic studies of aging run by the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, the Rush Memory and Aging Project and the Minority Aging Research Study9,10. Both studies recruit older adults without known dementia from around the greater Chicago metropolitan area and share nearly identical assessment protocols and operations (see below). At the time of these analyses (January 2021), 2,978 older persons were enrolled and had completed the baseline evaluation in these studies. Of those, 2899 individuals had a valid purpose in life measurement; the first visit with a valid purpose total score was considered the analytic baseline. We excluded individuals who had Alzheimer’s dementia at the analytic baseline (n = 126) or did not have at least one follow-up evaluation (n = 215). The analyses were performed on the remaining 2,558 older persons.

Assessment of purpose in life

Purpose in life was assessed using a 10-item rating scale derived from Ryff’s scales of Psychological Well-Being4,6,8. Participants rated their level of agreement with each item (e.g., I have a sense of direction and purpose in life, I am an active person in carrying out the goals I set for myself) on a five point scale, as previously described6,8. Item scores were averaged together to yield a total score for each participant (possible range=1–5), with higher scores indicating greater purpose in life.

Clinical classification of dementia and AD

Participants underwent annual uniform structured clinical evaluations that included a medical history, neurological examination, and administration of a battery of 19 cognitive tests9,10,11. Based on the clinical evaluation, an experienced clinician diagnosed Alzheimer’s dementia using the guidelines of the joint working group of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s and Related Disorders Association12. Alzheimer’s dementia requires a history of cognitive decline and impairment in memory and at least 1 other domain.

Determination of vital status

The Memory and Aging Project is a clinical-pathologic study and the autopsy rate exceeds 80%; thus, for most participants from the Memory and Aging Project, the exact date of death is known by being the day an autopsy was performed. In addition, participants from both studies are contacted quarterly to determine vital status and changes in health, and death can be learned of during quarterly contacts or annual visits. Finally, research assistants for both studies regularly search the Social Security Death Index via the internet for the small number of persons we are unable to contact. At the time of these analyses, vital status was known for all participants within the last 3 months.

Other covariates

First, because it is possible that depressive symptoms and medical conditions may confound the association of purpose with adverse health outcomes, we adjusted for these variables in supporting analyses. Depressive symptoms were assessed using a modified 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, and chronic medical conditions were assessed based on self-report of 8 common chronic conditions9. Second, because socioeconomic status also may be important, we further adjusted for income based on self-reported income using the show-card methodogy9.

Statistical Analysis

To examine bivariate associations of demographic variables with purpose in life, Alzheimer’s dementia diagnosis and death, we used Spearman correlation coefficient, t-tests, and Chi-square tests as appropriate. Then, to examine the effects of purpose in life on the onset age of incident Alzheimer’s dementia and death, we used general accelerated failure time (AFT) models13. The general AFT model assumes the survival time , defined as the onset age of each adverse event, given a covariate (i.e. purpose-in-life) for individual i, can be specified as

where is the baseline survival time, is the baseline mean parameter, is the coefficient of on the mean parameter, is the baseline scale parameter and is the coefficient of on the scale parameter. The coefficient charaterizes the main effect of purpose-in-life on the mean of age at each adverse event; and γ characterizes its effect on the variability of the age at event. The distribution of was modelled by the general gamma distribution for its flexibility, which included the commonly used Weibull, log-normal and gamma distributions as special cases14.

From this model, we can numerically derive the mean age at event given a particular value of purpose in life, and thus quantify the effects of purpose by years of age postponed for the adverse events15. We adjusted for left-truncation in all analyses. Finally, in supporting analyses, we further adjusted for education, sex, and potential confounders.

The general AFT models were fitted by R programs version 3.6.0 (R Core Team) using package flexsurv13. Data preprocessing and descriptive analysis were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 for Linux (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was determined at a level of 0.05.

Data availability

The data used in these analyses and a description of the studies can be accessed at the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center Research Resource Sharing Hub at https://www.radc.rush.edu. Qualified users can request de-identified data and obtain a Data Use Agreement.

RESULTS

Characteristics of study participants

Participants (n = 2,558) in these analyses had a mean age at baseline of 78.0 years (SD = 7.8 years, range: 53.4– 100.5) and a mean of 14.98 years of education (SD = 3.32, range: 0 – 30); 622 (24.3%) were men, 1,635 were white and non-Latinx (63.9%), and 817 were Black (31.9%). The mean purpose in life score at baseline was 3.74 (SD = 0.46), with higher scores indicating a higher level of purpose. Younger age (correlation = −0.271, p<0.001), higher education (correlation = 0.286, p<0.001) and male sex (mean difference = 0.06, t-statistic = 3.08, df = 1103.5, p = 0.002) were associated with a higher level of purpose.

Purpose in life and age of Alzheimer’s dementia onset

During a mean of 6.89 years of annual follow-up evaluations (SD = 4.52; range: 0.44 to 18.83), 520 individuals (20.3% of the 2,558) developed incident Alzheimer’s dementia with an average age at diagnosis of 88.0 years (SD = 6.71 years). Those who developed AD were older at baseline (mean difference = 5.19, t-statistic = 15.45, df = 918.6, p < 0.001) and less educated (mean difference = −0.42, t-statistic = −2.60, df = 822.7, p = 0.009) than those who remained free of dementia; the proportion of participants who developed Alzheimer’s dementia were not significantly different for men (n = 134; 21.5%) and women (n = 386, 19.9%; Chi-square = 0.739, df = 1, p = 0.390).

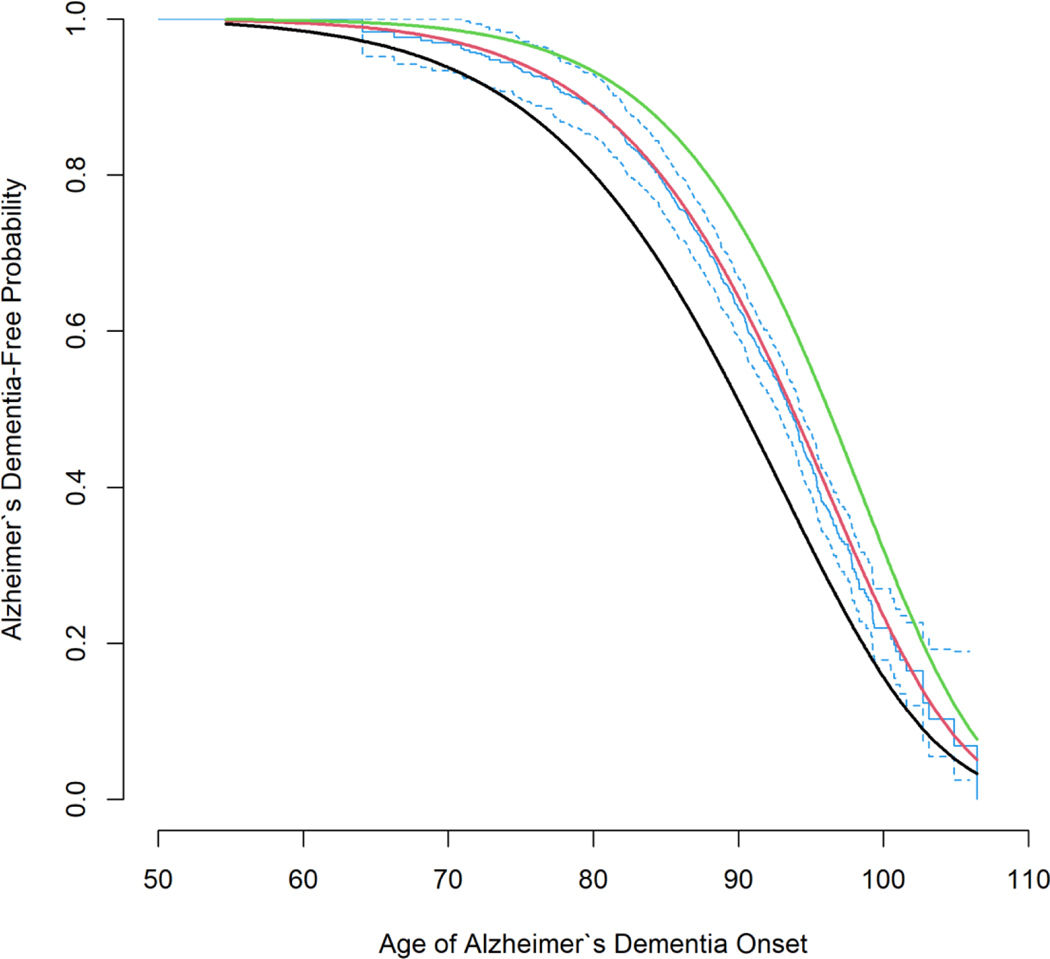

To estimate the association of the starting level of purpose in life with age of incident Alzheimer’s dementia diagnosis, we constructed a general accelerated failure time model. In this analysis, a higher level of purpose was associated with an older mean age at diagnosis (estimated mean parameter = 0.044; 95% CI: 0.023, 0.065). Specifically, a 1-unit increase in purpose in life prolonged the average age of Alzheimer’s dementia diagnosis by exp() − 1 = 4.4%, which translates to about 4 years. Figure 1, which is based on this analysis, shows the dementia-free survival probabilities associated with different starting levels of purpose (10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles, scores = 3.1, 3.8, and 4.3, respectively). We estimated that persons with a high level of purpose in life (score = 4.3, 90th percentile) developed Alzheimer’s at a mean age of 95.0 years compared to a mean age of 92.5 for those with a moderate level of purpose (score = 3.8, 50th percentile) and a mean age of 89.0 for persons with a low level of purpose (score = 3.1, 90th percentile).

Figure 1.

Alzheimer’s dementia-free probability curves estimated by the general AFT model: purpose in life = 3.1 (10% quantile; Black), 3.8 (50% quantile; Red), and 4.3 (90% quantile; Green). The solid blue curve is the Kaplan-Meier curve with 95% confidence intervals (dashed blue curve).

Because in prior work both education and sex have been associated with purpose and Alzheimer’s dementia, we constructed an additional general accelerated failure time model that included terms for education and sex. In this analysis, the association of purpose with the mean age of Alzheimer’s dementia onset persisted ( = 0.045; 95% CI: 0.024, 0.067), and neither education ( = 0.000007; 95% CI: −0.003, 0.003) nor sex ( = −0.017; 95% CI: −0.034, 0.002) were related to age of onset. Further, because depressive symptoms and medical conditions may confound the association of purpose in life and dementia, we added terms to control for them and the association of purpose with dementia remained essentially the same ( = 0.040, p < 0.001, 95%CI = 0.018 to 0.061). Finally, we also adjusted for income and again the finding persisted ( = 0.030, 95% CI: 0.008 to 0.051).

Purpose in life and mortality

During follow-up, 1089 (42.6% of the total 2,558) persons died; the average age at death was 89.2. Those who died were older at baseline (mean difference = 6.19, t-statistic = 21.9, df = 2437.6, p < 0.001) and less educated (mean difference = −0.60, t-statistic = −4.62, df = 2475.0, p < 0.001) than those who did not die; the rate of death was significantly higher for men (n = 310; 49.8%) than women (n = 779, 40.2%; Chi-square = 17.75, df = 1, p < 0.001).

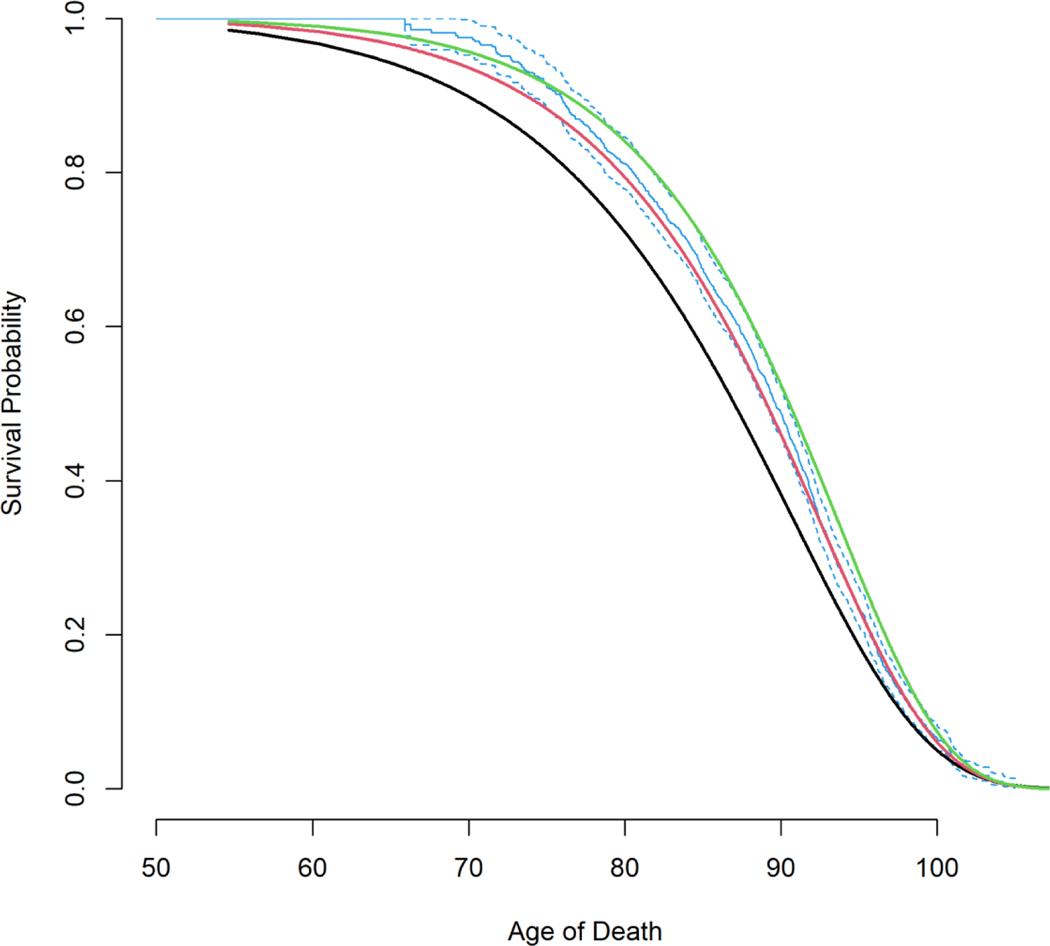

In a general accelerated failure time model, a higher level of purpose was associated with an older mean age at death (estimated mean parameter = 0.024; 95% CI: 0.010, 0.038). Figure 2 shows the survival probabilities associated with different baseline levels of purpose in life (10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles). The estimated mean age at death for individuals with a high level of purpose in life (score = 4.3, 90th percentile) was 88.9 compared to a mean age of 87.3 for those with a moderate level of purpose (score=3.8, 50th percentile) and 85.1 for those with a low level of purpose (score = 3.1, 10th percentile).

Figure 2.

Survival curves estimated by the general AFT model: purpose in life = 3.1 (10% quantile; Black), 3.8 (50% quantile; Red), and 4.3 (90% quantile; Green). The solid blue curve is the Kaplan-Meier curve with 95% confidence intervals (dashed blue curve).

Finally, we repeated the above analysis controlling for education and sex. In this analysis, the association of purpose with the mean age at death persisted ( = 0.021; 95% CI: 0.007, 0.036); education ( = 0.002; 95% CI: 0.0002, 0.004) and male sex ( = −0.036; 95% CI: −0.052, −0.021) were also related to age of death. Finally, the association of purpose with mortality persisted after adjustment for depressive symptoms, medical conditions, and income (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In a group of more than 2,500 older persons initially free of dementia who underwent annual clinical evaluations for up to 19 years, we found that those with a high level of purpose in life developed incident Alzheimer’s dementia about 6 years later than those with a low level of purpose and about 3 years later than those with a moderate level of purpose. Further, in a separate analysis, those with a high level of purpose in life died about 4 years later than those with a low level of purpose. These findings suggest that having a high level of purpose in life delays the onset of adverse health outcomes in old age by several years, thus conferring considerable public health benefit.

The present findings are highly novel and build on the prior literature in several ways. First, they provide an estimate of the number of years by which purpose in life delays the onset of Alzheimer’s dementia in old age. We and others previously reported that purpose in life is associated with a reduced risk of adverse health outcomes including dementia, disability, and death6–8,17,17. Moreover, in prior work, we reported that purpose in life is not directly related to the pathology of AD but reduces its deleterious impact on cognitive decline18. Those findings suggest that purpose in life does not prevent the accumulation of AD pathology but rather provides a buffer in the face of it. We conceptualize purpose in life as a psychological factor that provides resilience, likely via complex mechanisms. Finding purpose and developing meaning and intentionality requires self-reflection, synthesis of diverse experiences, consideration of one’s potential within the broader social context, and goal setting. The active development and pursuit of goals likely enhances the strength and efficiency of neural systems and may promote compensatory mechanisms that can help stave off dementia. Prior studies did not, however, examine whether purpose may delay the age of dementia onset (i.e., the delaying hypothesis). The present results provide strong support for the delaying hypothesis by showing that, among persons with a high level of purpose in life, dementia-free life is prolonged by 6 years.

Second, these findings provide evidence that purpose in life confers several additional years of life. Again, we and others previously reported that purpose was associated with a reduced risk of mortality, but those findings did not inform on the specific longevity benefit5–7. The analytic approach used here directly informs on this benefit and suggests that, remarkably, a strong sense of purpose in life promotes longevity. Importantly, this longevity benefit not only means for more time with family and friends but also more time for older adults to remain active and productive members of society. For example, older adults are increasingly engaging in “encore careers” (i.e., second careers initiated later in life). Encore careers allow use of knowledge and experience developed over a lifetime and promote social and mental engagement, all of which are critical for maintaining purpose and for successful aging more generally26–28. In addition to the impact of encore careers on individuals’ sense of purpose and utility, the potential economic impact is huge, as are the societal benefits that result from increased participation by experienced workers.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, these findings greatly extend our understanding of the potential public health impact of increasing purpose in life among the older adult population. A recent estimate suggests that an intervention that delays dementia onset by five years could reduce the number of affected individuals in the US by 30–50% (about 2.5 million fewer cases) in just over 5 years19. A similar delay in dementia onset could reduce costs associated with caring for dementia by more than 30%19,20. Further, even considerably smaller delays (for example, a 1 year delay) would significantly reduce both the number of persons affected with dementia and the associated costs19,20. Here, we estimated that persons with a high level of purpose have 6 additional dementia-free years compared to those with low purpose and 3 additional years compared to those with moderate purpose. Thus, increasing purpose in life among older adults will likely yield substantial public health and economic benefit.

Fourth, the present study adds to the growing body of evidence suggesting that purpose in life may be a unique and particularly promising target for intervention studies. Notably, in this and our prior work, the associations of purpose with adverse health outcomes were independent of psychological factors such as depressive symptoms, as well as other experiential factors and medical conditions8,16,18. This suggests that purpose is relatively distinct from depressive symptoms and should be considered an independent treatment target. Further, emerging research suggests that purpose in life is modifiable and amenable to improvement via a variety of approaches including mindfulness and cognitive-behavioral training21–24. Intervention studies have shown that purpose is protective against psychological and physical morbidity in the settings of cancer, chronic pain and other health conditions23–25. Here, we extend the potential impact of purpose-focused interventions to include dementia and longevity. Purpose in life therefore holds promise for improved outcomes across a variety of health conditions and should be prioritized as a treatment target that may have wide reaching mental and physical health benefits. Purpose may be an essential and important determinant of healthspan, the amount of time in life an individual remains healthy, engaged and autonomous.

This study has strengths and limitations. First, the availability of data on a large group of older persons who underwent detailed annual clinical evaluations for up to 19 years and a very high rate of annual follow-up allowed us to accurately identify incident dementia and carefully document vital status. It also minimized bias due to attrition. Second, using incident rather than prevalent dementia in analyses allowed us to estimate age of Alzheimer’s dementia onset from prospective observation rather than from retrospective informant report; this reduces a major source of bias. A limitation is that analyses were based on a selected group of relatively healthy older-old adults. Another is that other potentially important factors such as occupational attainment were not examined, although the findings persisted after controlling for related factors (i.e., income). Finally, although this study shows associations between purpose and adverse outcomes, causality cannot be established via this observational study. Future research is needed to determine the generalizability of the findings, but this study provides compelling evidence that a focus on purpose in life is warranted and that purpose should be immediately prioritized in intervention research.

Highlights.

This study addresses the question: does purpose in life delay the onset of dementia and mortality?

The main finding is that purpose in life delays the onset of these adverse outcomes by several years.

Purpose in life increases dementia-free years and longevity, suggesting that interventions to improve purpose in life may increase healthspan and offer considerable public health and economic benefit.

Footnotes

Disclosure/conflict of interest: None to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association, Facts and Figures Report, 2020: https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf

- 2.Brookmeyer R, Abdalia N, Kawas CH, Corrada MM. Forecasting the prevalence of pre-clinical Alzheimer’s disease in the United States. Alzheimer’s Dement 2018;14:121–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brookmeyer R, Johnson E, Ziegler-Graham A, Arrighi HM. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2007;3:186–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryff CD, Keyes CL. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:719–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krause N.Meaning in Life and Mortality. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64B:517–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyle PA, Barnes LL, Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Purpose in life is associated with mortality among community-dwelling older persons. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71:574–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alimujiang A, Wiensch A, Boss J, et al. Association Between Life Purpose and Mortality Among US Adults Older Than 50 Years. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e194270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Purpose in life is associated with a reduced risk of incident Alzheimer’s disease among community-dwelling older persons. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:304–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Boyle PA, Wilson RS. Overview and findings from the Rush Memory and Aging Project. Cur Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:648–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnes LL, Shah RC, Aggarwal NT, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. The Minority Aging Research Study: ongoing efforts to obtain brain donation in African Americans without dementia. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9(6):734–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Aggarwal NT, et al. Decision rules guiding the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in two community-based cohort studies compared to standard practice in a clinic-based cohort study. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;27:169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman M, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson CH. flexsurv: a platform for parametric survey modeling in R. Journal of Statistical Software. 2016; 70(8). DOI: 10.18637/iss.v070.i08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox C, Chu H, Schneider MF, Munoz A. Parametric survival analysis and taxonomy of hazard functions for the generalized gamma distribution. Stat Med. 2007;26:4352–4374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamarca R, Alonso J, Gomez G, Munoz A. Left-truncated data with age as time scale: an alternative for survival analysis in the elderly population. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998;53:M337–M343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Purpose in life is associated with a reduced risk of incident disability among community-dwelling older persons. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2010;58:1925–1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gale CR, Cooper C, Deary IJ, Aihie Sayer A. Psychological well-being and incident frailty in men and women: the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Psychological medicine. 2014;44:697–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Wilson RS, Yu L, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Effect of purpose in life on the relation between Alzheimer disease pathologic changes on cognitive function in advanced age. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69:499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zissimopoulos J, Crimmins E, St. Clair P.The value of delaying Alzheimer’s disease onset. Forum Health Econ Policy. 2014;18:25–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alzheimer’s Association, Changing the Trajectory of Alzheimer’s Disease: How a Treatment by 2025 Saves Lives and Dollars. 2015; https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/changing-the-trajectory-r.pdf

- 21.Tan EJ, Xue Q-L, Li T, Carlson MC, Fried LP. Volunteering: a physical activity intervention for older adults—the Experience Corps program in Baltimore. J Urban Health. 2006;83(5):954–969. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9060-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruini C, Fava GA. Well-being therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(5):510–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carlson LE, Doll R, Stephen J, et al. . Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based cancer recovery versus supportive expressive group therapy for distressed survivors of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(25):3119–3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lengacher CA, Johnson-Mallard V, Post-White J, et al. . Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) for survivors of breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(12):1261–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park CL, Pustejovsky JE, Trevino K, Sherman AC, Esposito C, Berendsen M, Salsman JM. Effects of psychosocial interventions on meaning and purpose in adults with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer. 2019;125(14):2383–2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wijeratne C, Earl J. A guide for medical practitioners transitioning to an encore career or retirement. Med J Aust. 2021; 214(1):12–14.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lam J, Aftab A, Lee E, Jeste D. Positive psychiatry interventions in geriatric mental health. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry 2020;7(4):471–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeste D.Successful aging of physicians. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2018; 26: 209–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in these analyses and a description of the studies can be accessed at the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center Research Resource Sharing Hub at https://www.radc.rush.edu. Qualified users can request de-identified data and obtain a Data Use Agreement.