Abstract

Mycobacterium tuberculosis and M. avium complex (MAC) enter and multiply within monocytes and macrophages in phagosomes. In vitro growth studies using standard culture media indicate that siderophore-mediated iron (Fe) acquisition plays a critical role in the growth and metabolism of both M. tuberculosis and MAC. However, the applicability of such studies to conditions within the macrophage phagosome is unclear, due in part to the absence of experimental means to inhibit such a process. Based on the ability of gallium (Ga3+) to concentrate within mononuclear phagocytes and on evidence that Ga disrupts cellular Fe-dependent metabolic pathways by substituting for Fe3+ and failing to undergo redox cycling, we hypothesized that Ga could disrupt Fe acquisition and Fe-dependent metabolic pathways of mycobacteria. We find that Ga(NO3)3 and Ga-transferrin produce an Fe-reversible concentration-dependent growth inhibition of M. tuberculosis strains and MAC grown extracellularly and within human macrophages. Ga is bactericidal for M. tuberculosis growing extracellularly and within macrophages. Finally, we provide evidence that exogenously added Fe is acquired by intraphagosomal M. tuberculosis and that Ga inhibits this Fe acquisition. Thus, Ga(NO3)3 disruption of mycobacterial Fe metabolism may serve as an experimental means to study the mechanism of Fe acquisition by intracellular mycobacteria and the role of Fe in intracellular survival. Furthermore, given the inability of biological systems to discriminate between Ga and Fe, this approach could have broad applicability to the study of Fe metabolism of other intracellular pathogens.

Fe is critical for the metabolism and growth of most microorganisms. Limitation of Fe availability is utilized by many animal species, including humans, as a means of host defense (20, 29). Chelation of Fe to proteins such as transferrin markedly decreases its accessibility to pathogenic microbes that grow and replicate extracellularly (3). Beyond this, infection leads to a shift of extracellular Fe from serum to the reticuloendothelial system. Microbial pathogens utilize several distinct means to counteract this strategy and obtain extracellular Fe from the host. Among these is siderophore production (39, 41).

Not all pathogens grow and replicate extracellularly. Mycobacterium tuberculosis and M. avium complex (MAC) are among a number of human intracellular pathogens that enter and multiply within monocytes and macrophages. Fe is necessary for mycobacterial growth in in vitro culture media, and siderophore production is felt to be critical in this process (13, 53). M. tuberculosis and MAC generally produce two types of siderophores, exochelins (also referred to as water-soluble mycobactins) and mycobactins (1, 13, 24, 25, 49, 53). Exochelins are hydrophilic high-affinity Fe3+ chelators which are secreted (24, 25, 48, 55). Mycobactins are hydrophobic siderophores that are associated with the bacterial cell membrane (24). Mycobacterial Fe acquisition is postulated to involve the acquisition of Fe from host high-affinity Fe-binding molecules such as transferrin by exochelin, followed by transfer of this Fe to mycobactin for subsequent internalization (24, 25). Extracellular transferrin has been shown to traffic to the M. tuberculosis-containing phagosome (10, 50), but there is no conclusive evidence that M. tuberculosis acquires Fe bound to this extracellular protein during intracellular growth.

Most evidence that mycobacteria residing within human macrophages require a source of Fe has been indirect through studies with other intracellular pathogens in which the host cell Fe pool has been decreased or enhanced through the addition of Fe chelators or Fe supplementation of culture medium, respectively (5, 37). Conclusions drawn from such approaches may be problematic since they mediate their effects through modulations of host cell physiology rather than by directly altering microbial access to Fe. The ability to investigate Fe acquisition mechanism(s) of mycobacteria and other intracellular pathogens residing within macrophages, as well as the role of these processes in the pathogenesis of infection with such organisms, would be greatly facilitated by the development of new strategies to disrupt Fe acquisition by such bacteria.

Gallium (Ga), a group IIIA metal, particularly in the form of Ga nitrate [Ga(NO3)3], is preferentially taken up by phagocytes at sites of inflammation (52) and by certain neoplastic cells, for which it is cytotoxic (22, 31, 32, 42, 47, 51). The biological and therapeutic effects of Ga3+ appear to relate to its ability to substitute for Fe3+ in many biomolecular processes, thereby disrupting them (8, 27). Ga3+, like Fe3+, enters mammalian cells, including macrophages, via both transferrin-dependent and transferrin-independent Fe uptake mechanisms (9, 40). In rapidly dividing tumor cells (as opposed to terminally differentiated cells such as macrophages), Ga interferes with cellular DNA replication via its ability to substitute for Fe in ribonucleotide reductase, resulting in enzyme inactivation due to the fact that Ga, unlike Fe, is unable to undergo redox cycling (8).

Based on (i) the ability of Ga to concentrate within mononuclear phagocytes and (ii) evidence that Ga disrupts Fe-dependent metabolic pathways, we hypothesized that Ga could serve as an experimental tool to disrupt acquisition and utilization of Fe by mycobacteria residing within human macrophages. Here we demonstrate that Ga-containing compounds inhibit the growth of M. tuberculosis and MAC regardless of whether they are growing extracellularly or within human macrophages. The mechanism appears to involve disruption of mycobacterial Fe-dependent metabolism. Furthermore, we provide the first definitive evidence for the acquisition of Fe from extracellular transferrin by intraphagosomal mycobacteria and demonstrate that Ga significantly decreases this process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mycobacteria.

M. tuberculosis Erdman (American Type Culture Collection [ATCC] 35801, a virulent strain) and H37Ra (ATCC 25177, an attenuated strain) were cultivated and harvested to form predominantly single-cell suspensions (45). A multidrug-resistant (MDR) isolate of M. tuberculosis (100% resistant to isoniazid and rifampin) was obtained from the State Hygienic Laboratory (University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa). The two MAC strains used were ATCC 25291 (MAC 1) and a clinical isolate obtained from the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory of the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics (MAC 2).

Macrophage culture.

Monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) and human alveolar macrophages (HAMs) were obtained as described elsewhere (23) from healthy adult volunteers who were purified protein derivative negative and had no history of mycobacterial infection. MDM monolayers (1.0 × 105 macrophages/well) were prepared in 24-well tissue culture plates (Falcon, Franklin Lake, N.J.) from Teflon wells on day 5 and then incubated for an additional 7 days at 37°C in RPMI supplemented with 20% autologous serum in order to stabilize the monolayer for subsequent incubation with mycobacteria. HAM monolayers were formed as for MDMs and were used immediately.

Analysis of extracellular mycobacterial growth.

Mycobacteria (3 × 103) were inoculated into BACTEC 12b broth culture bottles in the BACTEC 460TB system (Becton Dickinson Diagnostic Instrument System, Sparks, Md.) in the absence (control) or presence of Ga(NO3)3 and kept incubated under a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. Growth index readings were obtained daily as a function of mycobacterial growth in the culture bottles. In certain experiments, Ga complexed to transferrin was used in place of Ga(NO3)3. Apotransferrin was mixed with Ga(NO3)3 at a transferrin/Ga ratio of 1:2 in RPMI; the pH was adjusted to 7.4 with saturated aqueous NaHCO3, and the mixture was incubated overnight at 4°C. Free Ga was separated from Ga-transferrin by centrifugation in an Amicon concentrator (Amicon, Beverly, Mass.), followed by repetitive washing of the retentate two times (54).

In order to assess more accurately the role of Fe metabolism in the effect of Ga(NO3)3 on mycobacterial growth, M. tuberculosis (3 × 103 to 3 × 105) was added to 500 μl of 7H9 medium without added Fe and oleic acid, albumin, dextrose, and catalase (OADC) but supplemented with 0.2% Tween 80. The measured Fe concentration in this medium is 2 μM. The medium was supplemented with various concentrations of Fe in the presence or absence of Ga(NO3)3. Bacterial growth at defined time points (24 to 72 h) was then assessed using the BACTEC system.

To determine whether Ga is bactericidal for extracellular M. tuberculosis, Erdman strain M. tuberculosis (106 bacteria in 1 ml of 7H9 medium without added Fe) was placed in Teflon wells overnight at 37°C. Ga(NO3)3 (0 to 80 μM) was then added. Teflon wells were vortexed briefly each day; after 72 h the bacteria were resuspended by pipetting, and aliquots were removed to assess bacterial growth by counting the CFU after 2 weeks (reassessed after 5 weeks).

Analysis of the growth of mycobacteria in macrophages.

MDM or HAM monolayers were incubated with mycobacteria (bacterium/macrophage ratios from 1:1 to 5:1) for 2 h in RPMI containing 10 mM HEPES and 1 mg of human serum albumin (HSA; Calbiochem, La Jolla, Calif.) per ml, followed by washing to remove nonadherent bacteria. Monolayers were then covered with repletion medium (RPMI containing 1% autologous serum and, in the case of HAMs, supplemented with 2,000 U of penicillin per ml). Twenty-four hours later, Ga(NO3)3 at various concentrations was added. In some experiments, Ga(NO3)3 or Ga-transferrin was added either in combination with or 24 h following the addition of human recombinant gamma interferon (IFN-γ; Genzyme, Cambridge, Mass.) (10 to 10,000 U/ml). In each experiment, mycobacterium-infected macrophage monolayers devoid of inhibitors were included as controls. The supernatant from each well was removed, and cold sterile water (300 μl) was added to the monolayer. After 10 min with periodic agitation, 7H9 culture broth (660 μl) was added to the monolayer, followed by lysis with 0.25% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in phosphate-buffered saline (240 μl), and then 20% HSA (300 μl) in sterile water was added. The supernatant was treated similarly except that no water was added. Each tube (containing supernatant or cell lysate and two glass beads) was pulse vortexed five times, and its contents were removed and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min. The medium was carefully removed, and the bacterial pellets were resuspended in 7H9 broth. The cell lysate and its corresponding supernatant from each well were combined (200 μl, total) and injected into a BACTEC broth culture bottle for growth analysis.

To determine whether Ga is bactericidal for intracellular M. tuberculosis, MDM monolayers were incubated with Erdman M. tuberculosis (bacterium/MDM ratio of 1:1) exactly as described above. Ga(NO3)3 (500 μM) was added 24 h later. Bacterial growth was assessed by measuring CFU at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 days postaddition of Ga using the combined cell lysates, and supernatants were generated as described above.

Measurement of the acquisition of extracellular Fe by intracellular M. tuberculosis.

MDM monolayers, formed in four-well tissue culture plates (2.0 × 106 MDMs/well), were incubated with or without (control) H37Ra M. tuberculosis for 2 h, washed, and covered with repletion medium. After 48 h, 10 μM 59Fe (0.1 mCi/ml; Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.; 14.2 mCi/mg; NEN Life Science Products, Inc., Boston, Mass.) complexed to transferrin was added in the presence or absence of Ga(NO3)3. After 12 and/or 24 h, the monolayer was lysed in 0.1% SDS in the presence of DNase (200 μg/ml), and M. tuberculosis bacilli were released. The released bacteria were combined with the supernatant, washed in RPMI containing 0.01% SDS, resuspended, and filtered through a 0.22-μm (pore-size) Spin-X centrifuge tube filter (Corning Costar Corp., Cambridge, Mass.). The filter was placed in an O-ringed tube, and bacterium-associated 59Fe was then determined by using a gamma counter. Initial experiments revealed that approximately 86% of 59Fe was associated with the MDM monolayer lysate, 13% was associated with the floating MDM lysate, and <1% was associated with a pellet derived from the supernatant devoid of MDMs. Thus, ≥99% of 59Fe was MDM associated. In certain experiments, M. tuberculosis released from MDMs pulsed with 59Fe were subjected to autoradiography. In these experiments, the bacterial suspension released from the MDMs was diluted fivefold, and 1 ml was spotted onto a piece of nitrocellulose. The nitrocellulose was air dried in the biosafety cabinet and then wrapped in a plastic sheet. The nitrocellulose was exposed to film at −80°C.

In a control “mixing” experiment, uninfected MDM monolayers pulsed with 10 μM 59Fe for 24 h were lysed as described above and mixed with lysates of M. tuberculosis-infected MDMs that had not been pulsed with 59Fe. M. tuberculosis bacilli were then filtered through the centrifuge tube filter as described above, and the amount bacterium-associated 59Fe was determined.

To determine whether M. tuberculosis lipoarabinomannan (LAM)-coated microspheres (inert phagocytic particles) phagocytosed by MDMs and residing in phagosomes (30) acquire 59Fe added exogenously, Erdman M. tuberculosis LAM-coated 1-μm-diameter polystyrene microspheres were incubated with MDM monolayers for 2 h and then washed (46). After 48 h, 10 μM [59Fe2]transferrin was added for 24 h. The supernatant and monolayer were handled exactly as described above. The released microspheres were filtered through the centrifuge tube filter, and the amount of microsphere-associated 59Fe on the filter was then determined by using a gamma counter. The results were compared to a control microsphere “mixing” experiment performed as described above for M. tuberculosis.

Scanning EM of M. tuberculosis exposed to Ga(NO3)3.

To determine the morphology of broth-grown (extracellular) and intracellular M. tuberculosis released from MDMs in the presence or absence of Ga(NO3)3, scanning electron microscopy (EM) was performed. H37Ra M. tuberculosis in 7H9 broth was incubated in the absence or presence of Ga(NO3)3 (250 or 500 μM) for 24 h, washed, and filtered through the centrifuge tube filter as described above. Bacilli on the filter were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1% cacodylate buffer for 1 h at room temperature, postfixed in 1% buffered osmium tetroxide, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, and then critical point dried. When dry, the filters were cut free of the wells, mounted on Cambridge style pin stubs, and sputter coated with a 60/40 mixture of gold and palladium. Specimens were imaged using a Hitachi S-4000 FEGSEM.

Measurement of the acquisition of Fe and Ga from broth medium by M. tuberculosis.

M. tuberculosis (2 × 107/ml) was inoculated into 7H9 medium (without added Fe and OADC) plus 0.2% Tween 80 in Teflon wells. To this was added 500 nM 59Fe-citrate in the presence of increasing concentrations of Ga-citrate (0 to 80 μM) or 500 nM 67Ga-citrate in the presence of increasing concentrations of Fe-citrate (0 to 80 μM). At defined time points up to 8 h the mycobacteria were withdrawn (2 × 106 bacteria) into duplicate tubes and washed two times at 4°C, and bacterium-associated 59Fe or 67Ga was determined. Parallel tubes were analyzed without bacteria. Counts per minute (cpm) in these groups were subtracted from bacterium-associated counts and were <5% in all cases.

RESULTS

Ga inhibits the growth of mycobacteria in broth culture.

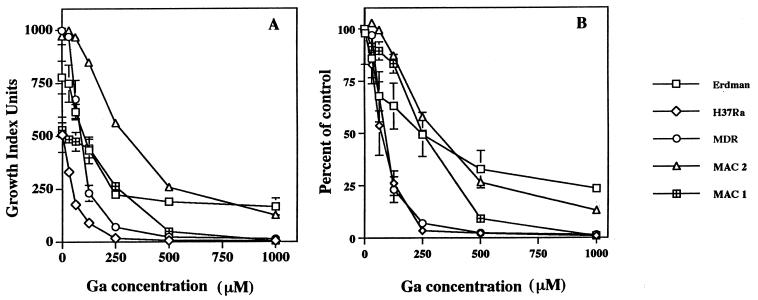

To determine the effect of Ga on the growth of M. tuberculosis and MAC, we inoculated 3.0 × 103 mycobacteria into BACTEC bottles and monitored bacterial growth over time in the absence or presence of Ga(NO3)3. A concentration-dependent growth inhibition of mycobacteria was observed in the presence of Ga(NO3)3 (Fig. 1). This growth inhibition was observed regardless of whether we used an attenuated strain of M. tuberculosis (H37Ra), the virulent Erdman strain of M. tuberculosis, MDR M. tuberculosis, or MAC.

FIG. 1.

Ga(NO3)3 inhibits the growth of M. tuberculosis and MAC in broth culture. A total of 3.0 × 103 mycobacteria (Erdman M. tuberculosis, H37Ra M. tuberculosis, an MDR M. tuberculosis clinical isolate, or two MAC isolates) were inoculated into BACTEC 12B bottles in the presence or absence (control) of the indicated concentrations of Ga(NO3)3. In panel A, growth is expressed in Growth Index Units. The results are presented as the mean ± the standard deviation (SD) for triplicate bottles for a representative experiment. In panel B, cumulative data are expressed as the percentage of control (absence of Ga). Each datum point represents the mean ± the SEM of two to seven independent experiments, each of which was done in duplicate or triplicate.

Ga and Fe compete for acquisition by mycobacteria.

Previous data with both eukaryotic and prokaryotic systems (8, 18, 22, 27, 51) led us to hypothesize that the inhibitory effect of Ga on mycobacterial growth occurs via disruption of bacterial Fe metabolism. Because of the high and variable amount of Fe we measured in commercial BACTEC medium (0.25 to 1.6 mM), we could not test this hypothesis directly in the BACTEC system.

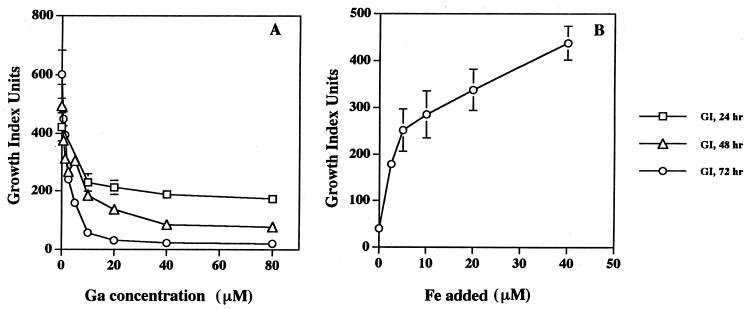

Therefore, mycobacteria were cultivated in defined 7H9 medium in which the basal Fe content was controlled. In this defined medium in which the Fe content (2 μM) is closer to that which occurs in vivo (43), much lower concentrations of Ga(NO3)3 markedly inhibited mycobacterial growth than those required using the BACTEC system, and the extent of growth inhibition increased over time (Fig. 2A). The 50% inhibitory concentration was approximately 1.25 to 2.5 μM at 72 h of Ga exposure. Importantly, the effect of Ga was prevented by the addition of exogenous Fe in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Low concentrations of Ga(NO3)3 inhibit the growth of M. tuberculosis under physiologic Fe conditions; the inhibition of growth is prevented in the presence of excess Fe. (A) Erdman M. tuberculosis (106/ml) was incubated in 7H9 medium without added OADC and Fe in the presence of the indicated concentrations of Ga(NO3)3. At defined time points aliquots of bacterial suspensions were inoculated into duplicate BACTEC 12B bottles, and the subsequent growth index was determined. The cumulative data for the indicated concentrations of Ga(NO3)3 at 24, 48, and 72 h are shown and represent the mean ± the SEM of three independent experiments. (B) Erdman M. tuberculosis (106/ml) was incubated in 7H9 medium without added ODAC and Ga, to which was added 10 μM Ga(NO3)3 and increasing concentrations of Fe-citrate. At 72 h bacterial suspensions were inoculated into BACTEC 12B bottles, and the subsequent growth index was determined. The results shown (mean ± the SD) are from a representative experiment (n = 2). Fe was also found to reverse the growth-inhibitory effect of Ga(NO3)3 on Erdman M. tuberculosis and MAC when the experiments were performed in BACTEC bottles (high-Fe-containing medium) (data not shown).

These data are consistent with the ability of Ga to inhibit Fe-dependent processes. We next assessed the ability of M. tuberculosis to acquire Ga and Fe. M. tuberculosis was suspended in 7H9 medium without added Fe or in OADC and increasing concentrations of either 67Ga or 59Fe. Cultures were incubated for defined time periods, following which the amount of bacterium-associated 67Ga or 59Fe was determined. Mycobacterial acquisition of both Ga and Fe was readily demonstrable. At all time points up to 8 h, the uptake of Fe exceeded that of Ga. At 8 h of incubation with a 16 μM concentration of each metal, 115.8 ± 28.5 fmol of Fe and 3.38 ± 0.41 fmol of Ga were associated with 106 bacteria, respectively (n = 3). Thus, the bacteria appear to have a greater capacity for Fe accumulation than for Ga accumulation.

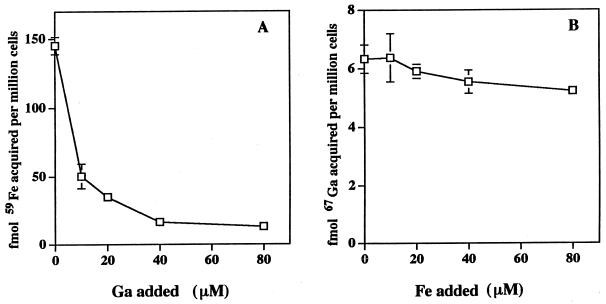

We next assessed the ability of Ga to compete for the acquisition of Fe by M. tuberculosis and vice versa. M. tuberculosis was suspended in 7H9 medium, to which was added either 67Ga or 59Fe in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of either “cold” Fe or Ga. Cultures were incubated for defined time periods following which the amount of bacterium-associated metal was determined. Whereas Ga was highly effective in competing for the acquisition of Fe by M. tuberculosis, Fe was relatively ineffective in competing for Ga acquisition (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Fe uptake by M. tuberculosis is markedly inhibited in the presence of Ga, whereas Ga uptake is inhibited to only a small degree by excess Fe. Erdman M. tuberculosis (2 × 107/ml) was incubated for 6 h in 7H9 medium (without added Fe and OADC) with 500 nM 59Fe-citrate (A) or 67Ga-citrate (B) in the absence or presence of the indicated concentrations of cold competing metal. The bacteria were then washed repeatedly, and bacterium-associated 67Ga or 59Fe levels were determined. Results are shown as the amount of metal acquired as a function of increasing concentrations of the cold competing metal. Experimental groups were performed in triplicate, and the data shown represent three independent experiments (mean ± the SEM).

Ga compounds inhibit the growth of mycobacteria in macrophages.

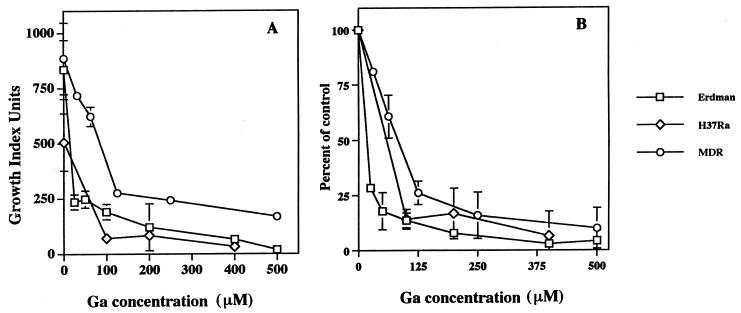

The critical site of growth of mycobacteria in vivo is within host macrophages. Analogous to the results with the broth culture experiments described above, Ga(NO3)3 inhibited mycobacteria growing within both human MDMs and HAMs in a concentration-dependent (Fig. 4) and time-dependent manner. Although mycobacterial growth was inhibited at 24 h (34 ± 5%, n = 8, for the Erdman strain; 50 ± 18%, n = 3, for the H37Ra strain), more-striking inhibition was observed 48 h (77 ± 4% for Erdman and 77 ± 1% for H37Ra) and 72 h (92 ± 3% for Erdman and 83 ± 12% for H37Ra) after the addition of Ga. NaNO3 [1.5 mM, equal to that present in 500 μM Ga(NO3)3] had no effect on mycobacterial growth in macrophages (data not shown), indicating that the Ga3+ and not the NO3− was responsible for the growth inhibitory activity of Ga(NO3)3. M. tuberculosis-infected monolayers were lysed over time in culture due to bacterial multiplication. In contrast, Ga(NO3)3-treated macrophage monolayers harboring M. tuberculosis remained more intact over the same time period (Fig. 5). In the absence of mycobacteria, Ga(NO3)3 at concentrations of up to 2 mM did not influence the density of the macrophage monolayer for up to 37 days as viewed by inverted phase microscopy.

FIG. 4.

Ga(NO3)3 inhibits the growth of M. tuberculosis within human macrophages in a concentration-dependent manner. Mycobacteria (Erdman, H37Ra, and MDR M. tuberculosis) were added to MDM or HAM monolayers at multiplicities (bacterium/macrophage) ranging from 1:1 to 5:1 (the results were the same). After 2 h, the monolayers were washed, and repletion medium was added. The indicated concentrations of Ga(NO3)3 were added 24 h later. Control monolayers were devoid of Ga(NO3)3. Growth index readings of combined supernatants and cell lysates from duplicate or triplicate wells were recorded on day 3 with the indicated concentrations of Ga(NO3)3. Shown in panel A is a representative experiment using MDMs (mean ± the SD). In panel B, cumulative data are expressed as the percentage of the control (mean ± the SEM, n = 2 to 5). Results using HAMs (n = 2) were the same as those using MDMs.

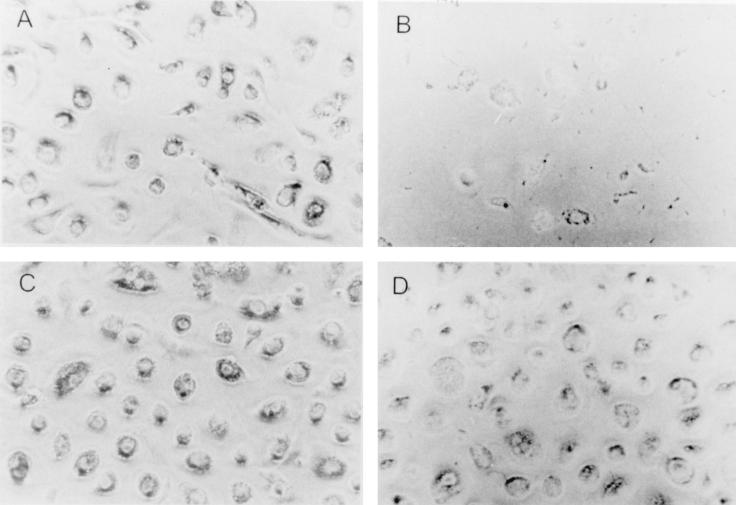

FIG. 5.

Growth of M. tuberculosis within MDMs over time results in loss of the monolayers whereas in the presence of Ga(NO3)3 the monolayer is preserved. MDM monolayers were incubated with Erdman M. tuberculosis. After 24 h Ga(NO3)3 (500 μM) was added. Control monolayers were devoid of Ga(NO3)3. The monolayers were assessed by inverted phase microscopy daily. The appearance of each monolayer on the day in which Ga was added is shown in panels A and C (control and Ga-treated, respectively). The appearance of the same monolayers after 7 days in culture is shown in panels B and D (control and Ga-treated monolayers, respectively). The micrographs shown are representative of all experiments performed (>20). Magnification, ×125.

Recent findings provide evidence that exogenous transferrin is transported to the M. tuberculosis-containing phagosome by phagosome–early-endosome fusion (10, 50). Since transferrin is capable of chelating Ga analogous to Fe and is the major physiologic chelate, we assessed the ability of Ga-transferrin to inhibit mycobacterial growth within human macrophages. The Ga-transferrin complex proved to be as effective as Ga(NO3)3 in inhibiting mycobacterial growth in both liquid media and within human macrophages. In macrophages, 72 h of exposure to Ga-transferrin (62.5 μM) inhibited M. tuberculosis growth by 50.7 ± 17.3% (mean ± the standard error of the mean [SEM], n = 5), MAC by 32.5 ± 0.2% (mean ± SEM, n = 2), and MDR M. tuberculosis by 73.0 ± 9.6% (mean ± SEM, n = 2).

Secretion of IFN-γ is important in regulating the immune response during tuberculosis (12, 21, 28, 38). IFN-γ downregulates macrophage ferritin levels and expression of the transferrin receptor (4). Thus, we reasoned that IFN-γ might reduce the ability of Ga to inhibit the growth of M. tuberculosis in macrophages. In agreement with published literature (14), IFN-γ alone did not inhibit growth of M. tuberculosis in human macrophages. M. tuberculosis growth in IFN-γ-treated MDMs was 90.6 ± 4.7% of control (mean ± SEM, n = 4) at 72 h. Preincubation of macrophages with IFN-γ did not influence the ability of Ga(NO3)3 or Ga-transferrin to inhibit growth of M. tuberculosis in these cells. The growth of M. tuberculosis in Ga-treated (100 μM) MDMs was reduced to 8.3 ± 3.1% and 13.8 ± 9.1% (mean ± SEM, n = 4) of the non-Ga-treated control cells when the MDMs were or were not exposed to IFN-γ over a range of concentrations (10 to 1,000 U/ml), respectively. Thus, the effects of Ga in the form of Ga(NO3)3 or Ga-transferrin on M. tuberculosis growth were not influenced by treatment of MDMs with IFN-γ.

Overall, these data provide evidence that Ga effectively inhibits the growth of two mycobacterial species in both simple and complex broth culture media and in two different types of human macrophages (MDMs and HAMs).

Ga is bactericidal for mycobacteria growing within macrophages.

Lack of growth in the BACTEC system may occur as a result of either bacterial survival without multiplication or bacterial death. To distinguish between these possibilities, we evaluated the influence of Ga(NO3)3 on the viability of M. tuberculosis in macrophages using a CFU assay. As shown in Table 1, there was a progressive decline in the number of CFUs with Ga treatment over 10 days. The number of CFU in control wells (without Ga) continued to increase over this time period. Even by day 2, the CFU in Ga-containing wells fell below the initial amount of bacteria (4.3 × 104 in the experiment shown in Table 1) in the macrophages, a finding consistent with bacterial killing. By day 10, the CFU count decreased by nearly 2 logs compared to the initial CFU count. Thus, Ga exposure exerts bactericidal activity against mycobacteria growing within macrophages. CFU studies also revealed that Ga was bactericidal in broth culture. In the presence of 80 μM Ga(NO3)3 for 72 h, CFU numbers for Erdman M. tuberculosis decreased from (4.5 ± 0.8) × 106 to (1.7 ± 0.1) × 106 (n = 2).

TABLE 1.

Ga(NO3)3 kills M. tuberculosis growing within human macrophagesa

| Test group | Mean CFU ± SD at (days post-Ga):

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | |

| Control | (4.3 ± 0.4) × 104 | (8.0 ± 1.7) × 104 | (2.2 ± 0.3) × 105 | (3.6 ± 0.6) × 105 | (6.4 ± 0.3) × 105 | (1.2 ± 0.0) × 106 |

| Ga(NO3)3 | (1.2 ± 0.2) × 104 | (7.3 ± 1.8) × 103 | (6.0 ± 0.1) × 103 | (3.0 ± 0.0) × 103 | (6.3 ± 1.8) × 102 | |

Data represent the mean ± the SD of duplicate samples from a representative experiment (n = 3). Harvested combined supernatants and cell lysates from wells were plated on 7H11 agar in serial dilutions, and CFU were counted after 2 weeks.

Ga disrupts Fe acquisition of intracellular M. tuberculosis.

There is transport of exogenously added transferrin to the M. tuberculosis-containing phagosome of human macrophages, suggesting that this may be an important source of Fe for the organism growing intracellularly (10, 50). We hypothesized that Ga would compete with Fe and therefore inhibit Fe uptake by mycobacteria dividing within the phagosome.

In order to test this hypothesis, we developed a method to quantitate the acquisition of extracellular Fe bound to transferrin by M. tuberculosis located within the macrophage phagosome. [59Fe2]transferrin was added to MDM monolayers in the presence or absence of Ga-transferrin 2 days following the addition of H37Ra M. tuberculosis. After an additional 12 and 24 h, the monolayers were lysed and M. tuberculosis bacilli were released from the phagosome by detergent treatment, washed, and trapped during filtration on a 0.22-μm (pore-size) filter. 59Fe was detected on the filter from M. tuberculosis-infected monolayers but not from uninfected monolayers; the filter from uninfected MDMs contained 113 ± 40 cpm, the filtrate from uninfected MDMs contained 13 ± 7 cpm, the filter from M. tuberculosis- infected MDMs contained 2,940 ± 839 cpm, and the filtrate from M. tuberculosis-infected MDMs contained 90 ± 64 cpm (mean ± SEM, n = 5). Bacterium-associated Fe levels were greater 24 h after the addition of [59Fe2]transferrin than at 12 h after addition (data not shown). Lysed M. tuberculosis-infected MDMs prior to filtration contained slightly less 59Fe than control lysed monolayers (206 ± 33 pmol for control MDMs and 160 ± 13 pmol for MDMs containing M. tuberculosis; mean ± SEM, n = 2).

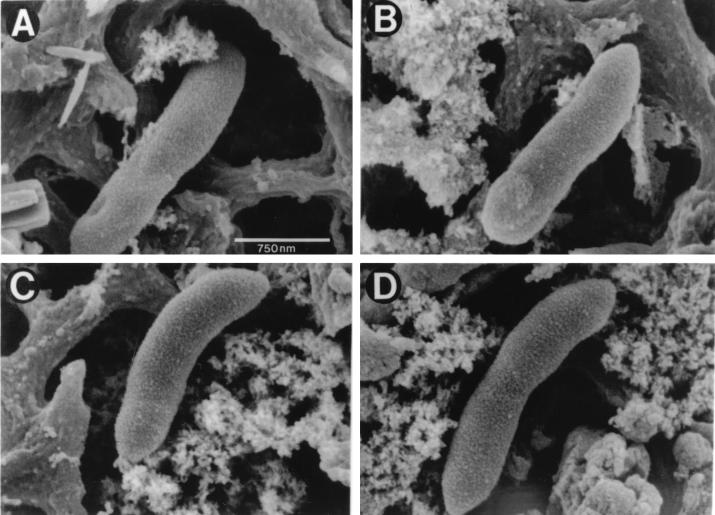

Several types of control experiments were undertaken to verify that the 59Fe detected on the filter was specifically associated with the bacteria. A control “mixing” experiment was performed to examine whether 59Fe complexed to host cell proteins bound nonspecifically to bacteria during the lysis process. Bacteria recovered from MDMs which had not been incubated with 59Fe transferrin or Ga were mixed on the day of harvesting with lysates from uninfected MDMs which had been incubated for 24 h with [59Fe2]transferrin. Under this condition, the counts detected from isolated bacteria on the filter (89 ± 43 cpm [mean ± SEM], n = 2) did not differ significantly from the counts on the filter from uninfected MDMs (208 ± 94 cpm [mean ± SEM], n = 7). Scanning EM of filters containing embedded bacilli revealed intact organisms with no evidence of associated cellular organelles or debris which could contain macrophage-derived Fe-containing molecules (Fig. 6). M. tuberculosis released from MDMs that had been pulsed with 59Fe were visualized by autoradiography as discrete uniformly black bacilli (data not shown). Together, these data provide further evidence that the 59Fe associated with the filter from lysed M. tuberculosis-infected macrophages was from the bacteria and not from host cell proteins or organelles which had become adherent to the bacteria during the lysis-centrifugation process.

FIG. 6.

Scanning EM of M. tuberculosis bacilli grown extracellularly or within macrophages. H37Ra M. tuberculosis grown in 7H9 broth (A), 7H9 broth in the presence of 500 μM Ga(NO3)3 for 24 h (B), and MDMs for 72 h (C) were harvested and trapped during filtration on a 0.22-μm (pore-size) filter. Fixed bacteria on the filter were then visualized by scanning EM. (D) Bacteria and macrophage lysates were mixed, and washed bacteria were fixed on the filter and then visualized as described above. Magnification, ×40,000.

To provide further evidence for the specific uptake (internalization) of 59Fe by bacteria, polystyrene microspheres coated with the M. tuberculosis cell wall lipoglycan, LAM, were used as inert phagocytic particles in the assay. These particles are phagocytosed by the macrophage mannose receptor and reside in phagosomes (30). MDMs containing LAM microspheres for 48 h were pulsed with [59Fe2]transferrin for 24 h, followed by bead isolation in detergent. No specific 59Fe activity was detected on the filters containing washed beads. A mixing experiment performed as described above with bacteria also failed to reveal specific 59Fe activity associated with the filter (data not shown).

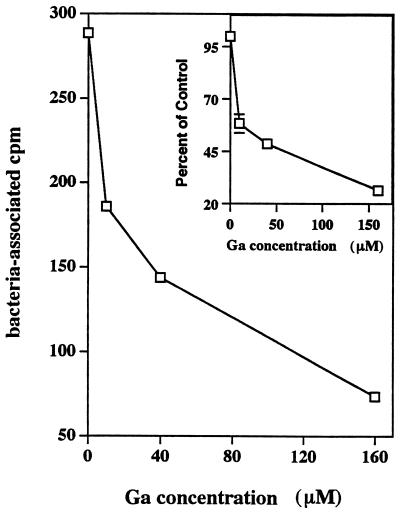

Having determined that Fe is acquired from exogenous Fe-transferrin by M. tuberculosis residing within the macrophage phagosome, we next assessed the effect of Ga on this process. As shown in Fig. 7, the presence of ≥10 μM Ga(NO3)3 markedly decreased the acquisition of 59Fe by intraphagosomal M. tuberculosis in a concentration-dependent manner. These data provide strong support for the hypothesis that Ga can disrupt Fe acquisition by intraphagosomal M. tuberculosis.

FIG. 7.

Ga-transferrin inhibits Fe acquisition by M. tuberculosis within macrophage phagosomes in a concentration-dependent manner. [59Fe]transferrin (10 μM) was added to M. tuberculosis-containing MDMs in the absence (control) or the presence of the indicated concentrations of Ga-transferrin for 24 h. MDMs were lysed, and lysates were filtered through a 0.22-μm (pore-size) filter. M. tuberculosis-associated radioactivity (expressed in cpm) on the filter was determined. Shown are the cpm values as a function of the Ga concentration added from a representative experiment. The inset shows the mean ± the SEM results of three separate experiments plotted as the percentage of control 59Fe acquisition.

DISCUSSION

Although it has been proposed that Fe metabolism is important in the pathogenesis of infection with intracellular pathogens such as M. tuberculosis and MAC, the evidence for this has been for the most part indirect. Cultivation of intracellular pathogens such as mycobacteria in microbiologic media clearly requires the presence of exogenous Fe. Under these conditions, the mycobacteria are felt to acquire Fe through the use of siderophore-based system (1, 24, 25, 49, 53). However, the potential sources of Fe to which mycobacteria have access when residing within a macrophage phagosome are likely to be quite different from those available when they grow extracellularly. Also, whether bacilli acquire Fe while residing in a macrophage phagosome or depend on Fe stores accumulated during their extracellular phase to meet their metabolic needs is unknown. Transferrin has been found to traffic from the extracellular space to the phagosome (10, 50), but it is not known whether Fe initially complexed to the protein also makes the journey or, if it does, whether the organism has the capacity to acquire it.

In order to address such issues, experimental means to modulate intraphagosomal mycobacterial Fe metabolism are needed. Approaches used in studies of extracellular pathogens, such as the use of Fe-depleted growth media or the addition of Fe chelating agents, are suboptimal for the study of intracellular pathogens. Fe-limited culture media may not significantly alter intracellular Fe stores in macrophages. Many Fe chelating agents (e.g., deferoxamine) penetrate cells poorly (6) and thus have variable access to intracellular mycobacteria.

Because of its ability to be readily taken up by macrophages and its known ability to compete with Fe in biologic systems, we examined the potential for Ga to be used as a means to modulate the Fe metabolism of mycobacteria (both M. tuberculosis and MAC). The incorporation of Ga into specific Fe-dependent enzymes leads to the inactivation of these enzymes because Ga3+, in contrast to Fe3+, is not able to undergo redox cycling (2). The cumulative data reported here demonstrate that Ga inhibits the growth of two mycobacterial species, M. tuberculosis and MAC, in media as well as when cultivated within two types of human macrophages in monolayer culture. Both Ga(NO3)3 and Ga-transferrin exhibit this effect. The inhibitory growth effect of Ga is prevented in a concentration-dependent fashion by excess Fe, implying that Ga acts primarily by interfering with bacterial Fe metabolism. Finally, our data provide evidence for a bactericidal effect of Ga(NO3)3 on M. tuberculosis both grown extracellularly and in macrophages.

To our knowledge, our work provides the first direct evidence for exogenous Fe acquisition by intraphagosomal M. tuberculosis. Clemens et al. and Sturgill-Koszycki et al. have demonstrated that extracellular transferrin traffics to the M. tuberculosis-containing phagosome (10, 50). Our data are consistent with the hypothesis that Fe bound to transferrin moves there as well and is subsequently acquired by the organism. Our data do not rule out two additional possibilities. First, that the 59Fe we find associated with intraphagosomal M. tuberculosis is transported to the macrophage cytoplasm, where it is subsequently acquired by the organism. Such a process would appear to required the movement of mycobacterial siderophore(s) into the macrophage cytoplasm to capture this Fe. There is recent evidence for the movement of Fe from intracellular Fe pools to the phagosomal membrane around MAC (56). Second, that extracellular Fe is taken up by the macrophage via a transferrin-independent pathway (40) and reaches intraphagosomal mycobacteria via another route.

Our results show that Ga competes with Fe for acquisition by M. tuberculosis grown in broth culture as well as within phagosomes in macrophages. Ga is known to be released from transferrin at a higher pH (ca. 6.5) than that necessary for the release of Fe from transferrin (pH 5.5) (34). Since the pH of the mycobacterial phagosome is ≥6.0, Ga may be particularly effective for competing with Fe in this environment. How Ga interferes with mycobacterial Fe acquisition is only partially addressed by our work. The most straightforward mechanism would involve direct competition with Fe for binding by the mycobacterial siderophores exochelin and/or mycobactin. In this regard, Ga binds to the siderophores of other bacteria (18, 27, 35). Alternatively, Ga that is internalized by the mycobacteria may also disrupt subsequent Fe acquisition through effects on transcriptional regulators involved in the Fe acquisition apparatus. Preliminary data indicate that Ga does not bind to IdeR (I. Smith, O. Olakanmi, B. Britigan, and L. Schlesinger, unpublished observation), which plays a key role in regulating mycobacterial siderophore production (16).

Our data provide evidence that M. tuberculosis can take up greater amounts of Fe than Ga. Ga is highly effective in competing for Fe acquisition by the bacterium; whereas Fe is relatively ineffective in competing for Ga acquisition. The uptake and competition experiments were performed at a time of exposure to Ga (1 to 6 h) and at a concentration below that which inhibits growth. Thus, the effect of Ga cannot be attributed to a general toxic effect on the organism.

The mechanisms involved in the uptake and transport of Fe-containing siderophores across the mycobacterial membrane are not understood and are likely complex. They are thought to involve specific receptors and transport molecules (7, 13, 15, 26). The efficient internalization of Fe3+ is thought possibly to be linked to its reduction to the ferrous form either enzymatically via a reductase or nonenzymatically (13). It is thus plausible that the lower capacity for Ga uptake by M. tuberculosis (compared to Fe uptake) is related to its inability to be reduced to the divalent state. This would not preclude the possibility that Ga bound to a receptor would effectively inhibit Fe binding and/or uptake. Our results demonstrating the relative inability of Fe to compete for Ga acquisition raises the possibility for a unique binding site for Ga distinct from that utilized by the Fe uptake pathway. The effect(s) of Ga on microbial physiology in general has received minimal attention (19, 27, 35).

Current studies are aimed at determining the intracellular target(s) for Ga in mycobacteria. Ribonucleotide reductase (RR) is a cell cycle regulated, two-subunit, allosteric enzyme that catalyzes the reduction of nucleoside diphosphates to deoxynucleoside diphosphates (44). RR appears to be an important target for Ga, resulting in the inhibition of growth of rapidly dividing eukaryotic cells (8). Terminally differentiated cells such as macrophages have negligible RR activity (33). RR is also critical for DNA synthesis in bacteria (44). Its affinity for Fe differs from that of mammalian cells (17). Preliminary studies demonstrate that Ga is a potent inhibitor of purified M. tuberculosis RR activity (H. Rubin, O. Olakanmi, B. Britigan, and L. Schlesinger, unpublished observation). Additional studies are under way to define the extent to which RR and other Fe-dependent mycobacterial enzymes (such as Fe-containing antioxidant enzymes) are modulated during mycobacterial exposure to Ga. In this regard, it is possible that the bactericidal effect of Ga on mycobacteria relates in part to the inactivation of bacterial Fe-centered antioxidant enzymes, leading to greater amounts of reactive oxygen or nitrogen products rather than simply Fe limitation, which typically results in bacteriostasis.

Together these studies demonstrate that intraphagosomal mycobacteria are capable of acquiring Fe bound to extracellular transferrin and that this process is disrupted by extracellular Ga. These data provide further evidence that Fe acquisition and Fe-dependent metabolism are critical to the survival of intracellular mycobacteria. Ga may serve as a novel experimental method to limit mycobacterial Fe acquisition and thereby investigate the mechanism and role of this process in mycobacterial survival and pathogenesis. Given that most biologic systems are unable to distinguish Ga from Fe, this approach may prove to be useful for disrupting the Fe acquisition mechanisms of other intracellular pathogens. Finally, our data also suggest a potential role for Ga in the therapy of mycobacterial infections in humans, where the problem of increasing resistance to antimicrobial agents is occurring (11, 36). Ga(NO3)3 is a drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of hypercalcemia of malignancy. The concentrations of Ga(NO3)3 which demonstrate antimicrobial activity in our in vitro systems are in the range of those achievable in vivo and found to be safe for human use (2, 51).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by VA Merit Review Grants (B.E.B. and L.S.S.), an AHA Established Investigator Award (B.E.B.), and NIH grants (AI24954 [B.E.B.] and HL51990, AI33004, and AI43870 [L.S.S.]).

We thank Thomas Kaufman for his expert technical assistance (particularly in the development of the bacterial growth assays in macrophages), Lucy DesJardin for advice, and J. Scott Ferguson and Stephen McGowan for assistance with the bronchoalveolar lavage for HAMs. We thank members of the Central Microscopy Research Facility at the University of Iowa and members of the Clinical Microbiology laboratory at the VAMC. Finally, we thank the National Cancer Institute for kindly providing human-injectable Ga(NO3)3.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barclay R, Ratledge C. Participation of iron in the growth inhibition of pathogenic strains of Mycobacterium avium and M. paratuberculosis in serum. Zentbl Bakteriol Hyg A. 1986;262:189–194. doi: 10.1016/s0176-6724(86)80019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein L R. Mechanisms of therapeutic activity for gallium. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:665–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bullen J J, Rogers H J, Griffiths E. Role of iron in bacterial infection. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1978;80:1–35. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-66956-9_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byrd T F, Horwitz M A. Interferon gamma-activated human monocytes downregulate transferrin receptors and inhibit the intracellular multiplication of Legionella pneumophila by limiting the availability of iron. J Clin Investig. 1989;83:1457–1465. doi: 10.1172/JCI114038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrd T F, Horwitz M A. Lactoferrin inhibits or promotes Legionella pneumophila intracellular multiplication in nonactivated and interferon gamma-activated human monocytes depending upon its degree of iron saturation. Iron-lactoferrin and nonphysiologic iron chelates reverse monocyte activation against Legionella pneumophila. J Clin Investig. 1991;88:1103–1112. doi: 10.1172/JCI115409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cabantchik Z I, Glickstein H, Golenser J, Loyevsky M, Tsafack A. Iron chelators: mode of action as antimalarials. Acta Haematol. 1996;95:70–77. doi: 10.1159/000203952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calder K M, Horwitz M A. Identification of iron-regulated proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and cloning of tandem genes encoding a low iron-induced protein and a metal transporting ATPase with similarities to two-component metal transport systems. Microb Pathog. 1998;24:133–143. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1997.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chitambar C R, Matthaeus W G, Antholine W E, Graff K, O'Brien W J. Inhibition of leukemic HL60 cell growth by transferrin-gallium: effects on ribonucleotide reductase and demonstration of drug synergy with hydroxyurea. Blood. 1988;72:1930–1936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chitambar C R, Zivkovic Z. Uptake of gallium-67 by human leukemic cells: demonstration of transferrin receptor-dependent and transferrin-independent mechanisms. Cancer Res. 1987;47:3929–3934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clemens D L, Horwitz M A. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome interacts with early endosomes and is accessible to exogenously administered transferrin. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1349–1355. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohn D L, Bustreo F, Raviglione M C. Drug-resistant tuberculosis: review of the worldwide situation and the WHO/IUATLD global surveillance project. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:S121–S130. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.supplement_1.s121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper A M, Dalton D K, Stewart T A, Griffin J P, Russell D G, Orme I M. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon-gamma gene-disrupted mice. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2243–2247. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Voss J J, Rutter K, Schroeder B G, Barry C E., III Iron acquisition and metabolism by mycobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4443–4451. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.15.4443-4451.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Douvas G S, Looker D L, Vatter A E, Crowle A J. Gamma interferon activates human macrophages to become tumoricidal and leishmanicidal but enhances replication of macrophage-associated mycobacteria. Infect Immun. 1985;50:1–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.1.1-8.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dover L G, Ratledge C. Identification of a 29 kDa protein in the envelope of Mycobacterium smegmatis as a putative ferri-exochelin receptor. Microbiology. 1996;142:1521–1530. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-6-1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dussurget O, Rodriguez M, Smith I. An ideR mutant of Mycobacterium smegmatis has derepressed siderophore production and an altered oxidative-stress response. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:535–544. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.1461511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elleingand E, Gerez C, Un S, Knüpling M, Lu G, Salem J, Rubin H, Sauge-Merle S, Laulhère J P, Fontecave M. Reactivity studies of the tyrosyl radical in ribonucleotide reductase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Arabidopsis thaliana: comparison with Escherichia coli and mouse. Eur J Biochem. 1998;258:485–490. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2580485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emery T. Exchange of iron by gallium in siderophores. Biochemistry. 1986;25:4629–4633. doi: 10.1021/bi00364a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emery T, Hoffer P B. Siderophore-mediated gallium uptake demonstrated in the microorganism Ustilago sphaerogenea. J Nucl Med. 1980;21:935–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finkelstein R A, Sciortino C V, McIntosh M A. Role of iron in microbe-host interactions. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5:5759–5777. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.supplement_4.s759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flynn J L, Chan J, Triebold K J, Dalton D K, Stewart T A, Bloom B R. An essential role for interferon-gamma in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2249–2254. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foster B J, Clagett-Carr K, Hoth D, Leyland-Jones B. Gallium nitrate: the second metal with clinical activity. Cancer Treatment Rep. 1986;70:1311–1319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaynor C D, McCormack F X, Voelker D R, McGowan S E, Schlesinger L S. Pulmonary surfactant protein A mediates enhanced phagocytosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by a direct interaction with human macrophages. J Immunol. 1995;155:5343–5351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gobin J, Horwitz M A. Exochelins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis remove iron from human iron-binding proteins and donate iron to mycobactins in the M. tuberculosis cell wall. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1527–1532. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gobin J, Moore C H, Reeve J R, Jr, Wong D K, Gibson B W, Horwitz M A. Iron acquisition by Mycobacterium tuberculosis: isolation and characterization of a family of iron-binding exochelins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5189–5193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.5189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall R M, Sritharan M, Messenger A J M, Ratledge C. Iron transport in Mycobacteria smegmatis: occurrence of iron-regulated envelope proteins as potential receptors for iron uptake. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:2107–2114. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-8-2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hubbard J A M, Lewandowska K B, Hughes M N, Poole R K. Effects of iron-limitation of Escherichia coli on growth, the respiratory chains and gallium uptake. Arch Microbiol. 1986;146:80–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00690163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jouanguy E, Altare F, Lamhamedi S, Revy P, Emile J F, Newport M, Levin M, Blanche S, Seboun E, Fischer A, Casanova J L. Interferon-gamma-receptor deficiency in an infant with fatal bacille Calmette-Guerin infection. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1956–1961. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612263352604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jurado R L. Iron, infections, and anemia of inflammation. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:888–895. doi: 10.1086/515549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang B K, Schlesinger L S. Characterization of mannose receptor-dependent phagocytosis mediated by Mycobacterium tuberculosis lipoarabinomannan. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2769–2777. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2769-2777.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelsen D P, Alcock N, Yeh S, Brown J, Young C. Pharmacokinetics of gallium nitrate in man. Cancer. 1980;46:2009–2013. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19801101)46:9<2009::aid-cncr2820460919>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krakoff I H, Newman R A, Goldberg R S. Clinical toxicologic and pharmacologic studies of gallium nitrate. Cancer. 1979;44:1722–1727. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197911)44:5<1722::aid-cncr2820440528>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mann G J, Musgrove E A, Fox R M, Thelander L. Ribonucleotide reductase M1 subunit in cellular proliferation, quiescence, and differentiation. Cancer Res. 1988;48:5151–5156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGregor S J, Brock J H. Effect of pH and citrate on binding of iron and gallium by transferrin in serum. Clin Chem. 1992;38:1883–1885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Menon S, Wagner H N, Jr, Tsan M-F. Studies on gallium accumulation in inflammatory lesions: II uptake by staphylococcus aureus: concise communication. J Nucl Med. 1978;19:44–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Musser J M. Antimicrobial agent resistance in mycobacteria: molecular genetic insights. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:496–514. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newman S L, Gootee L, Stroobant V, van der Goot H, Boelaert J R. Inhibition of growth of Histoplasma capsulatum yeast cells in human macrophages by the iron chelator VUF 8514 and comparison of VUF 8514 with deferoxamine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1824–1829. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.8.1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newport M J, Huxley C M, Huston S, Hawrylowicz C M, Oostra B A, Williamson R, Levin M. A mutation in the interferon-gamma-receptor gene and susceptibility to mycobacterial infection. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1941–1949. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612263352602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nielands J B. Microbial iron compounds. Annu Rev Biochem. 1981;50:715–731. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.003435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olakanmi O, Stokes J B, Britigan B E. Acquisition of iron bound to low molecular weight chelates by human monocyte-derived macrophages. J Immunol. 1994;153:2691–2703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Otto B R, Verweij-van Vught A M J J, MacLaren D M. Transferrins and heme-compounds as iron sources for pathogenic bacteria. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1992;18:217–233. doi: 10.3109/10408419209114559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oyen W J G, Boerman O C, Vander Laken C J, Claessens R A M J, Van der Meer J W M, Corstens F H M. The uptake mechanisms of inflammation- and infection-localizing agents. Eur J Nucl Med. 1996;23:459–465. doi: 10.1007/BF01247377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ponka P. Cellular iron metabolism. Kidney Int. 1999;55:S2–S11. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.055suppl.69002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reichard P. From RNA to DNA, why so many ribonucleotide reductases? Science. 1993;260:1773–1777. doi: 10.1126/science.8511586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schlesinger L S, Bellinger-Kawahara C G, Payne N R, Horwitz M A. Phagocytosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is mediated by human monocyte complement receptors and complement component C3. J Immunol. 1990;144:2771–2780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schlesinger L S, Hull S R, Kaufman T M. Binding of ther terminal mannosyl units of lipoarabinomannan from a virulent strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to human macrophages. J Immunol. 1994;152:4070–4079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seligman P A, Moran P L, Schleicher R B, Crawford E D. Treatment with gallium nitrate: evidence for interference with iron metabolism in vivo. Am J Hematol. 1992;41:232–240. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830410403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharman G J, Williams D H, Ewing D F, Ratledge C. Isolation, purification and structure of exochelin MS, the extracellular siderophore from Mycobacterium smegmatis. Biochem J. 1995;305:187–196. doi: 10.1042/bj3050187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Snow G A. Metal complexes of mycobactin P and of desferrisideramines. Biochem J. 1969;115:199–205. doi: 10.1042/bj1150199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sturgill-Koszycki S, Schaible U E, Russell D G. Mycobacterium-containing phagosomes are accessible to early endosomes and reflect a transitional state in normal phagosome biogenesis. EMBO J. 1996;15:6960–6968. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Todd P A, Fitton A. Gallium nitrate: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic potential in cancer-related hypercalcaemia. Drugs. 1991;42:261–273. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199142020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsan M-F. Mechanism of gallium-67 accumulation in inflammatory lesions. J Nucl Med. 1986;26:88–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wheeler P R, Ratledge C. Metabolism of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In: Bloom B R, editor. Tuberculosis: pathogenesis, protection, and control. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1994. pp. 353–388. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilson M E, Vorhies R W, Andersen K A, Britigan B E. Acquisition of iron from transferrin and lactoferrin by the protozoan Leishmania chagasi. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3262–3269. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3262-3269.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wong D K, Gobin J, Horwitz M A, Gibons B W. Characterization of exochelins of Mycobacterium avium: evidence for saturated and unsaturated and for acid and ester forms. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6394–6398. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6394-6398.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zwilling B S, Kuhn D E, Wikoff L, Brown D, Lafuse W. Role of iron in Nramp1-mediated inhibition of mycobacterial growth. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1386–1392. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1386-1392.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]