Abstract

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) is a relatively rare form of autoimmune disease. Diabetes insipidus (DI) is characterized by diluted polyuria and thirstiness, and is clinically categorized into central and nephrogenic DI depending on damaged organs. In most previously reported cases, ANCA-related disorders have been implicated in central DI, which is attributed to impaired secretion of arginine vasopressin (AVP) from the posterior pituitary. However, no previous case of AAV-related nephrogenic DI has been reported in the English literature. Herein, we report a case of nephrogenic DI likely caused by AAV. A 76-year-old man was admitted to our hospital for acute kidney injury. He showed dehydration, polyuria, and polydipsia. Laboratory tests demonstrated elevated levels of serum urea and creatinine and a high myeloperoxidase ANCA titer. In the present case, both plasma AVP concentration and response of AVP secretion to 5% saline load test were normal. In addition, 1-desmino-8-arginine vasopressin administration could not increase urinary osmolarity. Kidney biopsy specimen revealed tubulointerstitial nephritis with findings that appeared to indicate peritubular capillaritis. Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with nephrogenic DI likely owing to ANCA-associated tubulointerstitial nephritis. Immediately after prednisolone administration, urinary volume decreased, urinary osmolarity increased, and kidney function was improved. This case demonstrates that AAV that extensively affects the tubulointerstitial area can result in nephrogenic DI.

Keywords: Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, Anti-neutrophil cytoplastic antibody-associated vasculitis, Tubulointerstitial nephritis

Introduction

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) is a relatively rare form of autoimmune disease, characterized by destruction and inflammation of small vessels in various tissues. Granuloma formation is frequently observed in some cases of AAV. Several cases of AAV-related diabetes insipidus (DI) have been reported, which is characterized by diluted polyuria and thirstiness. DI is clinically categorized into central and nephrogenic DI depending upon damaged organs. In central DI, posterior pituitary lesion leads to impaired secretion of arginine vasopressin (AVP), which has an anti-diuretic action; consequently, diluted urine excretion is induced and free water clearance increases. In previously reported cases of DI in patients with positive ANCA, most were diagnosed as having central DI [1–5]. However, no previous case of AAV-related nephrogenic DI has been reported in the English literature. Nephrogenic DI results from failure of the kidney to respond to AVP secreted from the posterior pituitary. Various pathological conditions, including lithium intoxication, hypokalemia, hypercalcemia, urinary tract obstruction, and chronic kidney disease, lead to acquired nephrogenic DI [6–8]. In addition, nephrogenic DI has been infrequently reported in patients with drug-induced interstitial nephritis [6, 9, 10], sarcoidosis [11, 12], or amyloidosis [13].

In this report, we present a case of nephrogenic DI that developed in a patient with tubulointerstitial nephritis likely owing to AAV, as proven with kidney biopsy.

Case report

A 76-year-old man was admitted with acute kidney injury (AKI). The patient had no history of abnormal urinalysis or impaired kidney function until 2 weeks before admission when he presented to his family doctor because of lower abdominal pain. Around the same time, he developed thirstiness, polydipsia, and polyuria. He had tuberculosis in his 20 s and was treated with anti-tuberculosis drugs. He took nifedipine, atorvastatin, bezafibrate, and cimetidine because of hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Laboratory examination revealed increased levels of serum creatinine and urea; following which, he was referred to our hospital. On admission, he was completely awake and alert, but seemed to be exhausted. His blood pressure was 124/70 mmHg. He was not anemic or icteric. His skin and oral mucosa were dry. His lower abdomen was mildly tender. He had no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. Other physical examination was unremarkable. Neurological examination revealed no abnormal finding. Laboratory data, including blood cell counts, blood chemistry, serological test results, urinalysis, and endocrine data, on admission are shown in Table 1. In urinalysis, proteinuria was negative, but microhematuria was 3 + and red blood cell casts appeared. Computed tomography revealed a mild reticular pattern in addition to peripheral traction bronchiectasis, which had subpleural predominance in the base of both lungs (Fig. 1); it was determined to be probable interstitial pneumonia [14]. The only other finding was mild enlargement of the bilateral kidneys with no evidence of urinary tract stenosis or obstruction, hepatosplenomegaly, or lymphadenopathy.

Table 1.

Laboratory parameters on admission

| Blood cell counts | Blood chemistry | Serological test | Endocrine data | Urinalysis | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC | 8410 | /μL | TP | 7 | g/dL | IgG | 1355 | mg/dL | TSH | 1.2 | μIU/mL | pH | 6 | |

| Neu | 76.7 | % | ALB | 3.4 | g/dL | IgG4 | 51 | mg/dL | FT3 | 1.5 | pg/mL | Protein | (−) | |

| Lym | 16.4 | % | UA | 8.5 | mg/dL | IgA | 368 | mg/dL | FT4 | 1.2 | ng/dL | Occult blood | (3 +) | |

| Mon | 5.0 | % | BUN | 31.8 | mg/dL | IgM | 151 | mg/dL | GH | 0.42 | ng/mL | Glucose | (−) | |

| Eos | 1.8 | % | Cr | 2.36 | mg/dL | C3 | 156 | mg/dL | PRL | 6.7 | ng/mL | Specific gravity | 1.009 | |

| Bas | 0.1 | % | Na | 148 | mEq/L | C4 | 41 | mg/dL | ACTH | 15.5 | pg/mL | RBC | 20–29 | /HPF |

| RBC | 467 × 104 | /μL | Cl | 109 | mEq/L | CH50 | 66 | U/mL | Cortisol | 21 | μg/dL | Deformed RBC | (−) | |

| Hb | 14.3 | g/dL | K | 4.5 | mEq/L | ANA | < 40 | LH | 6.3 | mIU/mL | WBC | 1–4 | /HPF | |

| Ht | 43.1 | % | Ca | 8.9 | mg/dL | MPO-ANCA | 341 | IU/mL | FSH | 9 | mIU/mL | Hyaline cast | 0 | /HPF |

| Plt | 27.9 × 104 | /μL | IP | 4.5 | mg/dL | PR3-ANCA | < 0.5 | IU/mL | NAG | 16.6 | U/L | |||

| HbA1c | 6.4 | % | Anti GBM antibody | < 0.5 | U/mL | β2MG | 120 | μg/L | ||||||

| AST | 11 | U/L | KL-6 | 266 | ng/mL | FENa | 0.48 | % | ||||||

| ALT | 18 | U/L | SP-D | 39 | ng/mL | Osmolality | 243 | mOsm/kg | ||||||

| T-cho | 178 | mg/dL | Osmolality | 308 | mOsm/kg | Urine volume | 3130 | mL/day | ||||||

| TG | 127 | mg/dL | 24 h Ccr | 53.1 | mL/min | |||||||||

| HDL-c | 29 | mg/dL | ||||||||||||

| CRP | 6.87 | mg/dL | ||||||||||||

WBC white blood cell, Neu neutrophil, Lym lymphocyte, Mon monocyte, Eos eosinophil, Bas basophil, RBC red blood cell, Hb hemoglobin, Ht hematocrit, Plt platelet, TP total protein, ALB albumin, UA uric acid, BUN blood urea nitrogen, Cr creatinine, Na sodium, Cl chloride, K potassium, Ca calcium, IP inorganic phosphorus, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, T-cho total cholesterol, TG triglyceride, HDL-c high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, CRP C-reactive protein, IgG immunoglobulin G, IgA immunoglobulin A, IgM immunoglobulin M, C3 complement 3, C4 complement 4, CH50 50% hemolytic complement activity, ANA anti-nuclear antibody, MPO-ANCA myeloperoxidase-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, PR3-ANCA proteinase-3-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, GBM glomerular basement membrane, KL-6 Krebs von den Lungen-6, SP-D surfactant protein D, TSH thyroid stimulating hormone, FT3 free triiodothyronine 3, FT4 free triiodothyronine 4, GH growth hormone, PRL prolactin, ACTH adrenocorticotropic hormone, LH luteinizing hormone, FSH follicle stimulating hormone, pH potential hydrogen, NAG N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase, β2MG β2-microglobulin, FENa fractional excretion of sodium, Ccr creatinine clearance

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography of the chest. Computed tomography of the chest revealed a mild reticular pattern with peripheral traction bronchiectasis, which had subpleural predominance in the base of both lungs

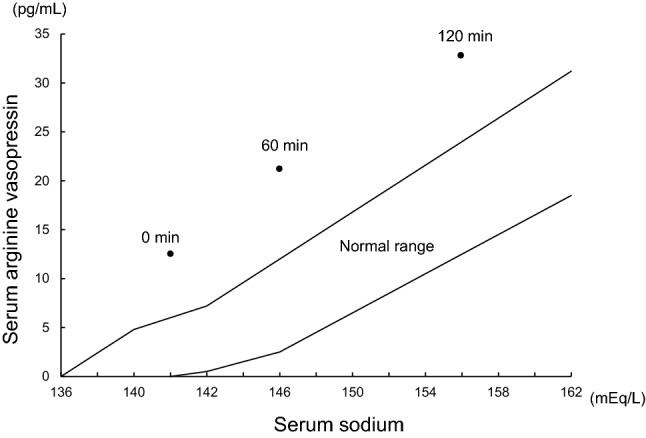

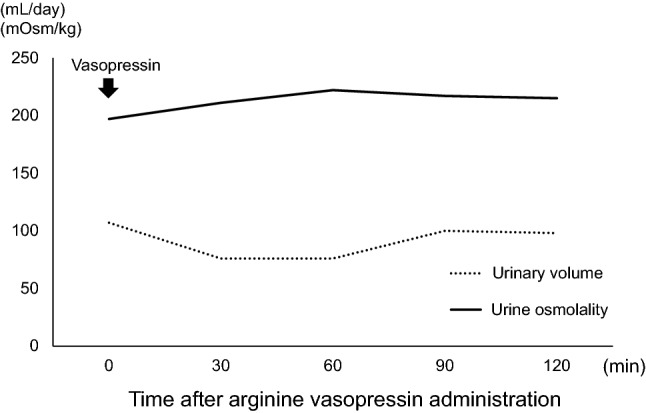

Initially, the patient was diagnosed with AKI due to dehydration. Subsequently, fluid therapy was likely to be attributed to polyuria. However, his dehydration persisted despite massive fluid replacement. Interestingly, urine output reached over 3000 mL/day and its osmolarity constantly decreased to less than 250 mOsm/kg. In addition, the patient experienced severe thirstiness and polydipsia. We performed both hypertonic saline loading test and vasopressin test to distinguish between central and nephrogenic DI. According to an increase in serum sodium concentration owing to 5% saline administration, plasma AVP concentration increased above normal range (Fig. 2). In addition, 1-desmino-8-arginine vasopressin (DDAVP) administration could not change urine output and urinary osmolarity (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Hypertonic saline test. Serum arginine vasopressin concentration increased above normal range after 5% saline administration

Fig. 3.

Vasopressin challenge test. 1-desmino-8-arginine vasopressin administration could not change urine output or urinary osmolarity

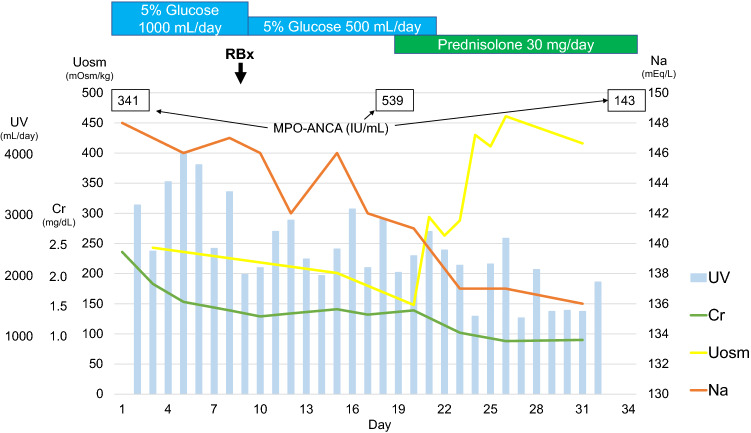

AKI in this patient was considered to be attributed to at least partial dehydration caused by nephrogenic DI. Furthermore, bladder distention due to polyuria might have led to his lower abdominal pain. Myeloperoxidase (MPO)-ANCA was positive at 341 IU/mL on admission, and ultrasound-guided kidney biopsy was performed to evaluate the renal lesion. Only one of the 23 glomeruli showed fibrous crescent; the remaining glomeruli were almost intact (Fig. 4a). The findings were classified as the focal group by Berden et al. [15]. The interstitial area was infiltrated with small numbers of neutrophilic cells, eosinophilic cells, lymphocytes, and histiocytes in a focal pattern, and inflammation was observed in 5–10% of the total specimen (Fig. 4b, c). There were also findings of tubulitis (Fig. 4d). There was no evidence of vasculitis with fibrin precipitation from the interlobular arteries to the afferent arterioles. The peritubular capillaries were dilated, the lumen was infiltrated with neutrophilic cells and histiocytes, and the vascular basement membrane was partially obscured, which was determined to be peritubular capillaritis (Fig. 4e, f). Immunofluorescence showed no significant immunoglobulin or complement deposition. Furthermore, electron microscopy showed no significant glomerular findings, and there was no evidence of disruption of the peritubular vascular basement membrane within the observed area. Additional MPO staining revealed MPO-positive cells in the peritubular capillaries of the interstitial area (Fig. 4g). Based on the above findings, as previously reported [16], the patient was most likely to have peritubular capillaritis and tubulointerstitial nephritis due to AAV. A small number of MPO-positive cells were also present in the intravascular and mesangial areas of the glomerulus (Fig. 4h), suggesting the possibility of very mild glomerular lesions. The diagnosis of microscopic polyangiitis was made based on the positive MPO-ANCA, positive C-reactive protein, interstitial pneumonia, the absence of findings suspicious for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis or granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and the tissue findings [17]. Immediately after the patient was started on oral prednisolone administration (30 mg/day), serum sodium and creatinine concentrations decreased to normal range, plasma osmolarity was reduced, and urinary osmolarity was elevated (Fig. 5). The patient showed neither dehydration nor impaired kidney function after cessation of fluid administration. Polydipsia, polyuria, and lower abdominal pain also disappeared.

Fig. 4.

Glomerular findings of renal biopsy. a The glomerulus was almost intact (PAS × 400). b Tubulointerstitial area was expanded diffusely, and inflammatory cells were observed (PAS × 100). c Inflammatory cells, consisting mainly of lymphocytes followed by neutrophilic cells and eosinophilic cells, were seen in the interstitial lesion (HE × 400). d Tubulitis (PAS × 1000). e, f Mononuclear cells (blue arrows) and neutrophils (green arrows) infiltrate the interior of the peritubular capillaries and the walls, and the basement membrane of the capillaries is obscured (red arrow) (PAM × 100). g Myeloperoxidase (MPO)-positive cells are found within peritubular capillaries (green arrows) and in the interstitial area (MPO × 400). h In the glomerulus, MPO-positive cells are seen in the mesangial region (green arrow) and in the blood vessels (red arrow) (MPO × 400)

Fig. 5.

Clinical course from admission. UV Urine volume, Cr creatinine, Na sodium, Uosm urinary osmolality, RBx renal biopsy, MPO-ANCA myeloperoxidase-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

Discussion

To our knowledge, this case report is the first, at least in the English literature, to reveal that AAV-associated tubulointerstitial nephritis induces acquired nephrogenic DI.

Nephrogenic DI comprise congenital and acquired forms. Congenital nephrogenic DI clinically develops in the neonatal period. Although various factors cause nephrogenic DI, most of the cases of acquired nephrogenic DI are attributed to drug-induced nephrogenic DI. Acquired nephrogenic DI is more common and less severe than congenital nephrogenic DI. Although the causes of nephrogenic DI include chronic kidney disease, electrolyte abnormalities (hypercalcemia, hypokalemia), drugs, pregnancy, or sick cell anemia [18], drug-induced nephrogenic DI is the most common [19, 20].

In acquired nephrogenic DI, hyporesponsiveness to AVP in the distal nephron, instead of etiology, results in impaired urinary concentration [19, 20]. In rare cases, both amyloid deposition in the interstitial area [13] and tubulointerstitial nephritis [6, 9, 10] lead to acquired nephrogenic DI. In our patient, the likely cause of acquired nephrogenic DI was AAV-associated tubulointerstitial nephritis, because nephrogenic DI improved immediately after steroid treatment. In most cases of AAV-associated central DI, granulomatous lesions were found in the posterior pituitary, subsequently leading to urinary concentration failure owing to AVP deficiency. Notably, although the present case showed normal AVP secretion in response to serum osmolarity change, urinary osmolarity remained unchanged.

In summary, this case demonstrated that AAV is a possible cause of tubulointerstitial nephritis associated with AKI and nephrogenic DI in an elderly man, and that kidney function and DI-related symptoms, including polyuria and polydipsia, improved immediately after induction of steroid treatment.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient described in this report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Xue J, Wang H, Wu H, Jin Q. Wegener’s granulomatosis complicated by central diabetes insipidus and peripheral neutrophy with normal pituitary in a patient. Rheumatol Int. 2009;29:1213–1217. doi: 10.1007/s00296-008-0774-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tenorio Jimenez C, Montalvo Valdivieso A, Lopez Gallardo G, McGowan B. Pituitary involvement in Wegener’s granulomatosis: unusual biochemical findings and severe malnutrition. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0220113850. doi: 10.1136/bcr.02.2011.3850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miesen WM, Janssens EN, van Bommel EF. Diabetes insipidus as the presenting symptom of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:426–429. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.2.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garovic VD, Clarke BL, Chilson TS, Specks U. Diabetes insipidus and anterior pituitary insufficiency as presenting features of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:E5. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(01)90002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duzgun N, Morris Y, Gullu S, Gursoy A, Ensari A, Kumbasar OO, et al. Diabetes insipidus presentation before renal and pulmonary features in a patient with Wegener’s granulomatosis. Rheumatol Int. 2005;26:80–82. doi: 10.1007/s00296-005-0583-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choudhury D, Ahmed Z. Drug-associated renal dysfunction and injury. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2006;2:80–91. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Salvo DN, Park J, Laing FC. Lithium nephropathy: unique sonographic findings. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:637–644. doi: 10.7863/jum.2012.31.4.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gong R, Wang P, Dworkin L. What we need to know about the effect of lithium on the kidney. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2016;311:F1168–F1171. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00145.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shirali AC, Perazella MA. Tubulointerstitial injury associated with chemotherapeutic agents. Adv Chron Kidney Dis. 2014;21:56–63. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masson EA, Rhodes JM. Mesalazine associated nephrogenic diabetes insipidus presenting as weight loss. Gut. 1992;33:563–564. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.4.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panitz F, Shinaberger JH. Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus due to sarcoidosis without hypercalcemia. Ann Intern Med. 1965;62:113–120. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-62-1-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muther RS, McCarron DA, Bennett WM. Renal manifestations of sarcoidosis. Arch Intern Med. 1981;141:643–645. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1981.00340050089019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carone FA, Epstein FH. Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus caused by amyloid disease: evidence in man of the role of the collecting ducts in concentrating urine. Am J Med. 1960;29:539–544. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(60)90050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL, Richeldi L, Ryerson CJ, Lederer DJ, et al. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:e44–68. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201807-1255ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berden AE, Ferrario F, Hagen EC, Jayne DR, Jennette JC, Joh K, et al. Histopathologic classification of ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Neprhol. 2010;21:1628–1636. doi: 10.1681/asn.2010050477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakabayashi K, Sumiishi A, Sano K, Fujioka Y, Yamada A, Karube M, et al. Tubulointerstitial nephritis without glomerular lesions in three patients with myeloperoxidase-ANCA-associated vasculitis. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2009;13:605–613. doi: 10.1007/s10157-009-0200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watts R, Lane S, Hanslik T, Hauser T, Hellmich B, Koldingsnes W, et al. Development and validation of a consensus methodology for the classification of the ANCA-associated vasculitides and polyarteritis nodosa for epidemiological studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:222–227. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.054593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ren H, Wang WM, Chen XN, Zhang W, Pan XX, Wang XL, et al. Renal involvement and followup of 130 patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:278–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moeller HB, Rittig S, Fenton RA. Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: essential insights into the molecular background and potential therapies for treatment. Endocr Rev. 2013;34:278–301. doi: 10.1210/er.2012-1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sands JM, Bichet DG. Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:186–194. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-3-200602070-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]