Abstract

Objective

To explore patient, clinician and decision-maker perceptions on a clinical trial evaluating the effectiveness of total hip arthroplasty (THA) compared with exercise to inform the trial protocol.

Design

This is an exploratory qualitative case study using a constructivist paradigm.

Setting and participants

Participants were enrolled into three key stakeholder groups: patients eligible for THA, clinicians, and decision makers. Focus group interviews were conducted in undisturbed conference rooms at two hospitals in Denmark, according to group status using semi-structured interview guides.

Analysis

Interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim and thematic analysed using an inductive approach.

Results

We conducted 4 focus group interviews with 14 patients, 1 focus group interview with 4 clinicians (2 orthopaedic surgeons and 2 physiotherapists) and 1 focus group interview with 4 decision-makers. Two main themes were generated. ‘Treatment expectations and beliefs impact management choices’ covered three supporting codes: Treatment without surgery is unlikely to lead to recovery; Clinician authority impacts the management narrative; The ‘surgery vs exercise’ debate. ‘Factors influencing clinical trial integrity and feasibility’ highlighted three supporting codes: Who is considered eligible for surgery?; Facilitators and barriers for surgery and exercise in a clinical trial context; Improvements in hip pain and hip function are the most important outcomes.

Conclusions

Based on key stakeholder treatment expectations and beliefs, we implemented three main strategies to improve the methodological rigorousness of our trial protocol. First, we added an observational study investigating the generalisability to address a potential low enrolment rate. Second, we developed an enrolment procedure using generic guidance and balanced narrative conveyed by an independent clinician to facilitate communication of clinical equipoise. Third, we adopted change in hip pain and function as the primary outcome. These findings highlight the value of patient and public involvement in the development of trial protocols to reduce bias in comparative clinical trials evaluating surgical and non-surgical management.

Trial registration number

NCT04070027 (pre-results).

Keywords: hip, qualitative research, musculoskeletal disorders, clinical trials

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This qualitative patient and public involvement study was used to inform the protocol of a randomised controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of total hip arthroplasty (THA) compared with exercise.

Focus group interviews were performed with patients, clinicians, and decision-makers to provide multiple perspectives and extend the scope of the findings.

An independent qualitative researcher conducted the data analysis to improve neutrality in the interpretation and development of themes and supporting codes.

Only one focus group interview was conducted for each of the groups with clinicians and decision-makers due to time limitations. This may impact the certainty of achieving data saturation in these two responder groups.

All participants in the patient group were scheduled for THA and 3 out of 14 had previously undergone this procedure, which may have influenced their perceptions.

Introduction

Hip osteoarthritis (OA) is a major cause of pain, disability and decreased quality of life.1 The overall prevalence of hip OA is 11%,2 and the disorder is the leading reason for undergoing total hip arthroplasty (THA) surgery.3 The number of THAs performed each year has increased dramatically over the past decade, with more than one million procedures annually undertaken worldwide.3 THA is considered an effective treatment to reduce pain, improve physical function and increase quality of life for severe hip OA.4 5 However, there is a risk of severe complications and up to 23% of the patients report long-term residual pain after THA surgery.3 6

Guidelines recommend exercise and patient education as first-line treatment in the management of hip OA.7 8 Specifically, progressive resistance training appears to provide moderate improvements in patient-reported outcomes and functional performance even in patients with severe hip OA.9 10 Furthermore, exercise and patient education might postpone the need for surgery and reduce patients’ willingness to undergo THA,11 12 but less than 40% of the patients are recommended or referred to first-line treatment.13 Despite the large number of THA surgeries performed annually, no clinical trial has investigated the comparative effectiveness of THA and non-surgical treatment in the management of hip OA.14 This comparison is of great importance as non-surgical treatment has been shown to be a viable alternative to surgery for many musculoskeletal disorders.15

Several clinician and patient barriers to participation in clinical trials have been identified. Main clinician barriers comprise lack of support staff and inadequate research training and difficulty with the consent procedure, while notable patient barriers include treatment preferences, worry caused by uncertainty and concerns about information and consent.16 Moreover, clinical trials comparing surgical procedures with non-surgical treatment have suffered from low enrolment rates and difficulties in retaining participants to their allocated treatments.17–21 With limited participation in these sort of clinical trials, a risk exists for research inefficiency and possibly biased findings that may drive clinical decision-making.22

Patient and public involvement strategies involve key stakeholders in the design, conduct and dissemination of research.23 24 Evidence suggests that patient and public involvement strategies have the potential to increase enrolment rates of participants and improve selection of outcome measures.23 24 However, only few clinical trials within the orthopaedic area have reported use of patient and public involvement,25 although more than 90% of the authors of surgical trials claim some incorporation of such strategies.23 Thus, based on the benefits and paucity of current evidence in this area, effective patient and public involvement strategies may help improve clinical trials comparing surgery to non-surgical treatment.

To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative patient and public involvement study preceding a clinical trial comparing surgical to non-surgical treatment, as previous trials did not report any engagement from patients and other key stakeholders.17–21 Therefore, we aimed to explore patient, clinician and decision-maker perceptions on a clinical trial evaluating the effectiveness of THA compared with exercise to inform the trial protocol.

Methods

Study design

We used an explorative qualitative design based on a constructivist paradigm, as data was co-constructed by the researchers and participants.26 This approach was used as we aimed to gain a detailed understanding of a multifaceted phenomenon by exploring the experiences, attitudes and beliefs of the key stakeholder participants. This study was reported in agreement with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist27 and preceded the Progressive Resistance Training Versus Total Hip Arthroplasty (PROHIP) trial.28 Written informed consent was obtained from each participant in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Sampling and participants

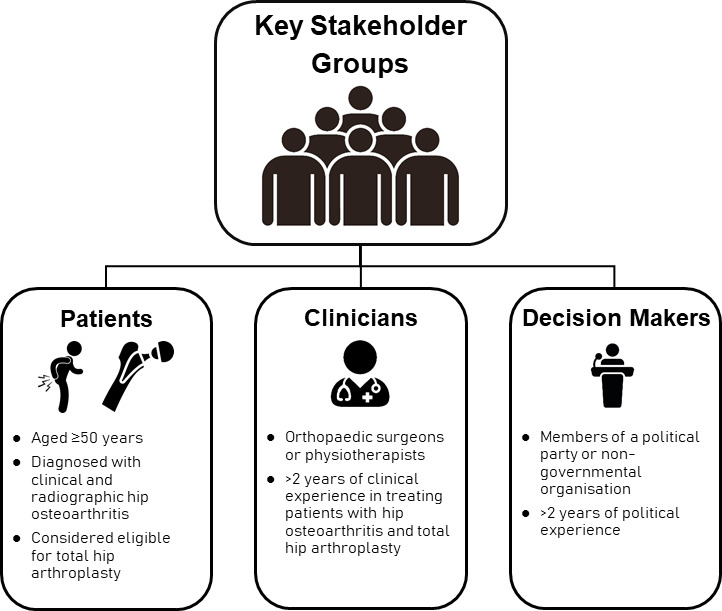

Participants were enrolled into three key stakeholder groups: patients, clinicians (orthopaedic surgeons and physiotherapists) and decision-makers (members of a political party or non-governmental organisation) (figure 1). Key stakeholders were engaged at the level of consultation to obtain input on several research decisions and implement the findings into our trial protocol.29

Figure 1.

Eligibility criteria for each key stakeholder group: patients, clinicians and decision-makers.

Patients were recruited consecutively by orthopaedic surgeons from the orthopaedic departments at Vejle Hospital and Odense University Hospital. The eligibility criteria were similar to the PROHIP trial to ensure a typical patient response. The complete list of inclusion and exclusion criteria has been published previously.28 Briefly, eligible patients were aged ≥50 years, diagnosed with clinical and radiographic hip OA and considered eligible for THA.

A convenience sample of clinicians not involved in the design of the PROHIP trial with >2 years of clinical experience in treating patients with hip OA from the orthopaedic and physiotherapy departments at the two hospitals was contacted personally face to face or by email and invited to participate in the study.

A purposive sample of decision-makers with >2 years of political experience from the spectrum of political parties and relevant non-governmental organisations from the Region of Southern Denmark was approached by email and invited to participate in the study.

Data collection

Data were collected through focus group interviews allowing the advantage of dynamic group interactions.30 Each interview included two to five key stakeholders, lasted between 90 and 120 min and was conducted from September 2018 to March 2019 by a female physiotherapist (KST), with 10 years of clinical orthopaedic experience and trained in qualitative methodologies. Prior to each focus group interview, the interviewers’ profession was disclosed to the key stakeholders. The interviewer was neither affiliated with the PROHIP trial group nor had previous interaction with key stakeholders. Group-specific open-ended semistructured interview guides (online supplemental file 1) were developed by the first author (TF) to explore topics related to the PROHIP trial.31 The number of focus group interviews were not predetermined for the patients, whereas one interview was planned for the clinicians and decision-makers due to time limitations. For the patients, the semistructured interview guide was continuously adjusted after each focus group based on field notes made during the interviews by the first author. Data saturation was considered attained, if no new themes, perspectives and knowledge developed within two consecutive interviews. All interviews were digitally audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and translated into English by an independent linguist. The transcripts and findings were not returned to the key stakeholders for comments and validation because we expected that their reflective answers would develop during the focus group interview. Quotes from the interviews are used to support claims and illustrate the generated themes and supporting codes. All data were pseudoanonymised and stored in digital format on a password-protected hospital server conforming to current data protection standards. The focus group interviews were performed face to face in undisturbed conference rooms at Vejle Hospital and Odense University Hospital, according to group status. The interviewer and the first author were present during all focus group interviews.

bmjopen-2022-070866supp001.pdf (223.8KB, pdf)

Key stakeholder characteristics were obtained using a participant-reported questionnaire. Additionally, the patient group completed the Oxford Hip Score (OHS)32 and Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS).33

Data analysis

An independent qualitative researcher (CM) not affiliated with the PROHIP trial group conducted a code book thematic analysis using an inductive approach with no predetermined themes following the six-step framework described by Braun and Clark.34 35 Initially, this process involved familiarisation with the data by reading and re-reading the transcripts. This was followed by generating initial codes, in which line-by-line inductive coding was performed on interviews to define and develop a code list. This code list was used to code subsequent interviews deductively, but according to the constant comparison method, as new codes developed these were again applied across all focus group interviews.36 As the analysis progressed, coding shifted from descriptive to explanatory, resulting in a number of axial codes. Then related axial codes were organised into preliminary main themes. Lastly, main themes and supporting codes were refined and a final thematic network was developed followed by writing of the manuscript.34 35 The analysis was performed using Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis software (Atlas Ti, V.8).

Implementation of findings into the trial protocol

After the data analysis was completed, the generated thematic network comprising main themes and supporting codes was presented to the PROHIP trial group. We assessed these findings and identified methodological implementation considerations and strategies for the trial protocol and categorised these across relevant identified domains. Disagreements were resolved by discussion until consensus.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or members of the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination of this qualitative study, but constituted the patient and public involvement strategy used in the development of the PROHIP trial.28

Results

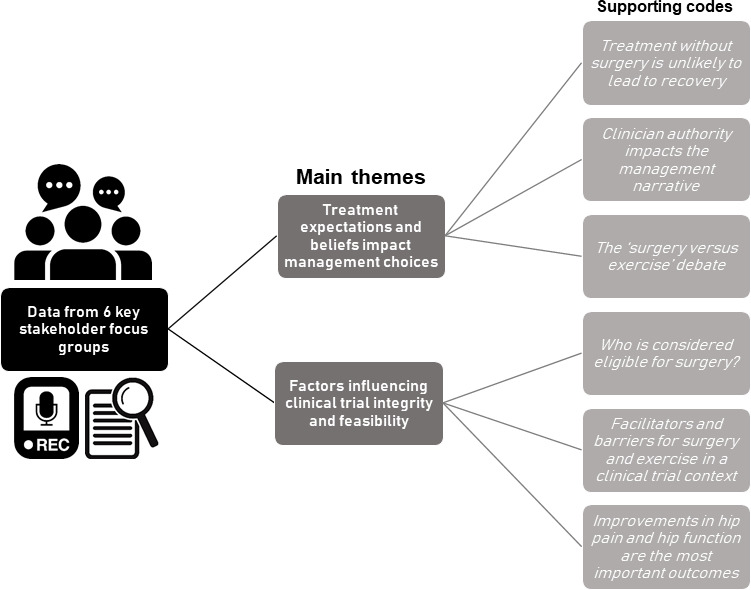

We conducted 4 focus group interviews with a total of 14 patients, 1 focus group interview with 4 clinicians (2 orthopaedic surgeons and 2 physiotherapists), and 1 focus group interview with 4 decision-makers (online supplemental file 2). Participant characteristics are presented in table 1. Two main themes were generated from the thematic framework. ‘Treatment expectations and beliefs impact management choices’ covered three supporting codes: Treatment without surgery is unlikely to lead to recovery; Clinician authority impacts the management narrative; The ‘surgery versus exercise’ debate. ‘Factors influencing clinical trial integrity and feasibility’ highlighted three supporting codes: Who is considered eligible for surgery?; Facilitators and barriers for surgery and exercise in a clinical trial context; Improvements in hip pain and hip function are the most important outcomes (figure 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the key stakeholder groups*

| Characteristic | Patients (N=14) |

Clinicians (N=4) |

Decision-makers (N=4) |

| Female sex — n (%) | 8 (57.1) | 1 (25.0) | 2 (50.0) |

| Age — years | 68.5 (51.0–80.0) | 48.0 (38.0–52.0) | 56.5 (23.0–68.0) |

| Clinical and radiographic hip osteoarthritis— n (%) | 14 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Previous total hip arthroplasty — n (%) | 3 (21.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| OHS — range 0 to 48† | 21.5 (10.0–38.0) | – | – |

| HOOS subscales — range 0 to 100‡ | |||

| Pain | 42.5 (20.0–77.5) | – | – |

| Symptoms | 32.5 (15.0–80.0) | – | – |

| Function in activities of daily living | 47.8 (20.6–86.8) | – | – |

| Hip-related quality of life | 31.3 (12.5–68.8) | – | – |

| Function in sports and recreation | 25.0 (0.0–62.5) | – | – |

| Clinical profession — n (%) | |||

| Orthopaedic surgeon | – | 2 (50.0) | – |

| Physiotherapist | – | 2 (50.0) | – |

| Clinical experience — years | – | 16.0 (3.0–18.0) | – |

| Hospital affiliation — n (%) | |||

| Vejle Hospital | – | 2 (50.0) | – |

| Odense University Hospital | – | 2 (50.0) | – |

| Political experience — years | – | – | 5.0 (3.0–5.0) |

| Political or non-governmental affiliation — n (%) | |||

| The Liberal Party of Denmark (V) | – | – | 1 (25.0) |

| The Danish People’s Party (O) | – | – | 1 (25.0) |

| The Social Democratic Party (A) | – | – | 1 (25.0) |

| The Danish Rheumatism Association | – | – | 1 (25.0) |

*Values are median (range) unless otherwise indicated.

†The Oxford Hip Score (OHS) ranges from 0 to 48, with higher scores indicating better disease status.

‡For all five subscales, the Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS) ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better disease status.

Figure 2.

Main themes and supporting codes generated from focus groups with patients with hip osteoarthritis considered eligible for total hip arthroplasty, clinicians (orthopaedic surgeons and physiotherapists) from orthopaedic and physiotherapy departments, and decision-makers (members of a political party or non-governmental organisation).

bmjopen-2022-070866supp002.pdf (88.4KB, pdf)

Treatment expectations and beliefs impact management choices

Treatment without surgery is unlikely to lead to recovery

Patients had high expectations of a complete reduction of hip pain, fast return to desired activities-of-daily-living and functional performance approximating their presymptomatic state after THA surgery.

I find it important to get rid of the pain, but also to get back to being physically active. Those two are equally important to me. I think. Because it used to be such a big part of my life (Patient 3, age 60-69 years).

Patients had uncertain and/or sceptical expectations about exercise, but believed that exercise could lead to improvements.

I have not been informed about the possibility of exercising the pain away (Patient 5, age 70-79 years).

Patients and decision-makers perceived exercise as a more appropriate treatment for mild-to-moderate stages of hip OA or as an adjunct to THA in the preoperative and/or postoperative phases to improve the outcome of THA.

But if a hip is in a better state, then there is still a possibility to improve the person’s condition without surgery. At the early stages of hip deterioration, exercise may seem like the best way forward (Decision maker 3, age 60-69).

It is important to do exercise both before and after the surgery, to make your muscles as powerful as possible (Patient 1, age 60-69 years).

Patients with severe hip pain perceived themselves as highly disabled and considered any treatment without THA surgery unlikely to lead to their recovery.

Having a defect hip is constraining both physically and mentally. Totally disabling. (Patient 6, age 60-69 years).

I don’t believe that it is possible to remove the symptoms just by means of exercising. I don’t believe that is possible (Patient 7, age 50-59 years).

Clinician authority impacts the management narrative

Patients expressed a need to be guided verbally through the trial protocol and information by a competent and trustworthy clinician. In this regard, the orthopaedic surgeons were seen as the most authoritative clinician.

When I consulted the orthopaedic surgeon, the doctor. We were told absolutely everything about it [THA surgery], and he does it very well. There was no doubt in my mind (Patient 5, age 70-79 years).

Orthopaedic surgeons tended to describe THA as a core treatment, with exercise being considered as a postsurgical adjunct treatment, and thus reinforced the perception of their status as the most authoritative clinician group by virtue of their control over the THA treatment narrative.

It is quite clearly “the surgery of the century”. If the surgery is made on the right patient, it is both a safe and effective surgery. The degree of satisfaction is generally very high, both seen from the patients and the surgeons’ perspectives (Clinician [Orthopaedic surgeon 2], age 40-49 years).

Patient respondents highlighted that both orthopaedic surgeons and physiotherapists tended to use a management narrative suited to their preferred treatment and at times these narratives were juxtaposed.

The orthopaedic surgeon said: You can get a new hip, but I suggest you try to exercise for a period and then you can return to me when the pain gets too severe. The physiotherapists, they are very eager avoid surgery. At least the ones I have met, they have told me that I can exercise the pain away (Patient 2, age 50-59 years).

Clinicians were aware of the potential impact of their authority on patient perceptions of treatment effectiveness. This practice was viewed with concern as the PROHIP trial relies on trial participants perceiving THA and exercise as equal treatments.

It is possible to talk about the different possibilities in a fairly objective way through a standardized text. And then it is important not to laugh… when the patient asks us, what would you choose? (Clinician [Orthopaedic surgeon 2], age 40-49 years).

The ‘surgery versus exercise’ debate

Clinicians were aware of an ongoing discourse, pitching other surgical procedures and exercise against one another. Both the orthopaedic surgeons and physiotherapists agreed that fuelling a debate of choosing one approach over another was not a desirable in the context of the PROHIP trial.

This became quickly exercise against surgery, very much head-to-head and completely out of context of reality. We did not recognize, nor in the media the picture they created with the interpretation that you should rather exercise or carelessly get surgery (Clinician [Physiotherapist 2], age 30-39 years).

Rather than pitching the two treatments against one another, an orthopaedic surgeon highlighted that it was important to develop a narrative emphasising surgery and exercise as fundamentally different, yet complementary.

But the question is whether surgery and exercise can be considered equal. Because surgery is dangerous, exercise is not very dangerous. Surgery is invasive, irreversible. Exercise is something you try out, and if it does not work, then you can have surgery (Clinician [Orthopaedic surgeon 2], age 40-49 years)

Factors influencing clinical trial integrity and feasibility

Who is considered eligible for surgery?

Patients highlighted variations in the nature of hip OA, and perceived that radiographic findings were the primary indication criteria for determining treatment selection.

If a person is in pain and has a lot of cartilage left, then this person should be offered exercise and surgery should be postponed. (Patient 1, age 60-69 years).

Physiotherapists questioned the indication criteria for THA used in the clinical assessment, since they had observed a substantial variation in hip pain and functional performance among patients prior to surgery.

At the information meetings, we see people who walk normally, and we then wonder why these people need new hips, because this person does not seem to be in pain, nor to be functionally impaired (Clinician [Physiotherapist 1], age 50-59 years).

For orthopaedic surgeons, improvements from exercise were associated with an incorrect diagnosis or considered as secondary to hip OA.

You need to be absolutely certain that the patient suffers from osteoarthritis. I believe that the patients who experience improvements by exercise, they suffer from a problem with the soft tissue. Something they have had in any circumstances or is secondary to the osteoarthritis (Clinician [Orthopaedic surgeon 1], age 50-59 years).

Facilitators and barriers for surgery and exercise in a clinical trial context

Based on responses, it seemed that younger patients were less likely to select surgery as first-line management. This appeared to be driven by health beliefs and concerns for the durability of THA. Patients perceived both THA and exercise as treatments to provide pain management without usage of analgesics. However, THA was clearly seen as a means to abolish severe pain, whereas less clarity was observed for exercise as residual hip pain was viewed as both a driver and barrier for continued adherence. Exercise was considered as a low-risk treatment, while THA was perceived as a last resort treatment with a risk of serious adverse events. Patients indicated that improvements derived from exercise would encourage to continued adherence, whereas a failure of exercise to provide sufficient improvements in hip pain and activities of daily living was a driver for THA. Patients were more likely to undergo THA once presented with radiographic findings visualising degenerative changes and/or progression of OA. Finally, patients considered establishing and maintaining exercise habits as important, and emphasised the importance of supervision to provide clinical expertise and motivation during exercise sessions. Potential facilitators and barriers for THA surgery and exercise in the PROHIP trial are summarised in table 2.

Table 2.

Facilitators and barriers for surgery and exercise in the Progressive Resistance Training Versus Total Hip Arthroplasty (PROHIP) trial

| Surgery | Illustrative quote(s) | Exercise | Illustrative quote(s) | |

| Facilitators | Severe hip pain | I am currently in a lot of pain, and I am looking forward to being released from that pain (Patient 1, age 60–69 years). | Patient age | …people who feel too young to have hip surgery… because they see themselves as being physically active and capable of exercising the pain away (Clinician (Orthopaedic surgeon 2), age 40–49 years). |

| Low quality of life | I cannot walk more than 100 meters, even with a cane (Patient 6, age 60–69 years). | Pain management without analgesics | Those four exercises are very valuable to me… I almost never take pills (Patient 2, age 50–59 years). | |

| Ineffective first-line management | I have not been able to reduce my pain by means of exercise or physical activity, I need to have surgery to be able to live a tolerable life (Patient 6, age 60–69 years). | Low risk of adverse events | It [exercise] will not harm them, and if they see improvements that is great. (Clinician (Orthopaedic surgeon 2), age 40–49 years). | |

| Analgesics dependency | I ate so many pills, we agreed that something had to be done’ (Patient 2, age 50–59 years). ‘They foresee that they will not be forced to take pills and at the same time, they will get well. Therefore, they choose surgery (Clinician (Orthopaedic surgeon 2), age 40–49 years). |

Perception of improvement | If I was able to feel a signification improvement after the 12-weeks exercise program, then I would be motivated to continue (Patient 5, age 70–79 years). | |

| Diagnostic imaging | When I got here the second time and saw the x-rays, I saw how much cartilage had disappeared since last time – in that short period of time - I said to myself that the actual bone may be next in line. I said to myself that there was no point in waiting any longer (Patient 2, age 50–59 years). | Habitualised exercise | Well, naturally I have spoken to other people about exercise, and I have asked them why they do not exercise, and they have a hard time getting started with it. Then I suggest that we go together, because the social aspect of it is very important, for some people at least (Patient 11, age 70–70 years). | |

| Loss of livelihood | I may be rejected from the labour market because of my age, and I am not entitled to pension. So, I cannot afford not having surgery now (Patient 6, age 60–69 years). | Supervision | It is also beneficial to have the presence of a professional person who can inform us about how the specific exercises help you, …where we are supposed to feel the pain if we do them correctly, which muscle is used and how to recognize this muscle (Patient 4, age 70–79 years). | |

| Context of exercise | I would appreciate to be in a place together with a group of people, where one person would instruct the others. And if you meet with a group of people several times, then you feel like being part of a community, and you can talk about the same things… That motives me (Patient 2, age 50–59 years). | |||

| Tracking and gamification | It matters a lot, I think. Just like when you use a pedometer or a health app, I like that. I like to be able to see the result of my efforts… like Endomondo – get notified about having completed something (Patient 3, age 60–69 years). | |||

| Barriers | Patient age | …the uncertainty about whether the hip will last 10, 15, 20 years, and whether I will be able to get a new replacement at that time (Patient 2, age 50–59 years). I am also concerned about the durability of the total hip arthroplasty, because wearing out an artificial hip would result in a second surgery (Clinician (Physiotherapist 1), age 50–59 years). |

Too much or too little hip pain | I have to say that when you are in pain, it is easy to exercise. But then when you don’t feel pain, then you tend to forget to do your exercises one day, and then next day and so on. So, when everything is fine, then I have a hard time getting motivated to do exercises (Patient 1, age 60–69 years). Some people benefit a lot from exercise, but other people come back to me and explain that exercise only worsened the pain (Clinician (Orthopaedic surgeon 2), age 40–49 years). |

| Risk of adverse events | A small risk of the surgery not being successful. That the pain ends up being much worse than before. I think that we all fear that… It would be so devastating if that should happen to us (Patient 2, age 50–59 years). Well, if the result is a foot drop, then I will not consider the surgery a success (Patient 7, age 50–59 years). |

Low motivation | What is bad for me is that I always come up with a good excuse for not going… working out at home does not work for me, it is better if I go to a fitness centre with other people around (Patient 3, age 60–69 years). | |

| Continuity interruptions | …doing exercises in the fitness centre. But, I have also… Maybe I have taken some breaks, I could have put more efforts into it (Patient 3, age 60–69 years). |

Improvements in hip pain and hip function are the most important outcomes

Patients and clinicians indicated change in hip pain and hip function as the most important outcomes to evaluate the treatment effect of surgery or exercise.

My biggest problem is that I feel pain in all the different kinds of movements I do. No matter what kind of movement I do, I feel the pain (Patient 12, age 50-59 years).

Patients and clinicians also highlighted quality of life, functional performance (ie, gait function), patient acceptable symptom state, muscle strength, treatment crossover (ie, number of THA surgeries in the exercise group), return to work and leg-length discrepancy as other meaningful outcomes to assess in the PROHIP trial.

Methodological implementation strategies for the trial protocol

Based on our data, we identified four domains for methodological implementation strategies to optimise the PROHIP trial protocol, and these were: patient ‘buy in’, enrolment strategies, patient information materials and important clinical outcomes. The domains, their thematic association and supporting coding are illustrated in table 3.

Table 3.

Methodological implications derived from the listed domains, main themes and supporting codes used to inform the Progressive Resistance Training Versus Total Hip Arthroplasty (PROHIP) trial protocol

| Domain | Main theme(s) | Supporting code(s) | Methodological implications for the PROHIP trial protocol |

| Patient ‘buy in’ |

Treatment expectations and beliefs impact management choices Factors influencing clinical trial integrity and feasibility |

Treatment without surgery is unlikely to lead to recovery Clinician authority impacts the management narrative The ‘surgery versus exercise’ debate Who is considered eligible for surgery? Facilitators and barriers for surgery and exercise in a clinical trial context |

Guided implementation of a parallel observational study investigating the generalisability of the clinical trial, since many patients probably may decline participation in the trial. Guided development of retention procedures (ie, instructions of study personnel to encourage patient completion), statistical analysis plan (ie, handling of missing data, sensitivity and exploratory analyses, and subgroup and causal mediation analysis), and exercise protocol (ie, effective supervision and habitualised exercise protocol). |

| Enrolment strategies | Treatment expectations and beliefs impact management choices Factors influencing clinical trial integrity and feasibility |

Clinician authority impacts the management narrative The ‘surgery versus exercise’ debate Who is considered eligible for surgery? |

Guided development of instruction and training strategy in the enrolment procedures. Guided implementation of generic guidance and neutral narrative during enrolment procedures to provide verbal information about the trial. Guided clinician roles in enrolment procedures (ie, eligibility assessment, provider of trial information to the patients) and selection of an independent clinician group to provide detailed verbal information about the trial to facilitate communication of clinical equipoise. |

| Patient information materials | Treatment expectations and beliefs impact management choices Factors influencing clinical trial integrity and feasibility |

Treatment without surgery is unlikely to lead to recovery Clinician authority impacts the management narrative The ‘surgery versus exercise’ debate Facilitators and barriers for surgery and exercise in a clinical trial context |

Guided and informed content for the written patient materials and this included information on current evidence of treatment effects for surgery and exercise, trial objective and procedures, randomisation process, content of baseline and follow-up sessions, risks and harms, treatment crossover and withdrawal procedures, clinical implications and funding. Guided development of the neutral narrative used in the written patient materials to facilitate communication of clinical equipoise. |

| Important clinical outcomes | Treatment expectations and beliefs impact management choices Factors influencing clinical trial integrity and feasibility |

Treatment without surgery is unlikely to lead to recovery Improvements in hip pain and hip function are the most important outcomes |

Guided selection of hip pain and function as primary outcome. Guided selection of hip-related quality of life and functional performance (ie, gait function) as key secondary outcomes Guided selection of patient acceptable symptom state and muscle strength as exploratory outcomes. |

Patient ‘buy in’

We identified sampling bias as a potential external validity threat in the clinical trial. In response, a parallel observational study was conceptualised to investigate the generalisability of the clinical trial, since many patients probably may decline participation in the trial. Additionally, we addressed facilitators and barriers for surgery and exercise among patients that could systematically affect retention rates and lead to treatment crossover in the clinical trial. Consequently, in an effort to optimise retention and reduce treatment crossovers, we developed a more focused retention procedure (ie, instructions of study personnel to encourage patient completion) and tailored exercise protocol with a greater focus on effective supervision during exercise sessions and implementation of a habitualised exercise protocol. Furthermore, a nuanced statistical analysis plan was prioritised in regard to handling of missing data, sensitivity and exploratory analyses, subgroup and causal mediation analysis.

Enrolment strategies

We identified preconceived beliefs and perceptions among clinicians as a potential threat to sampling in the trial. In response, we implemented an instruction and training strategy for orthopaedic surgeons and project coordinators in standardised verbal information about the trial to facilitate communication of equipoise during enrolment procedures. Focus was placed on the creation of a neutral narrative to be used when verbal information was provided during enrolment. To encourage clinical equipoise, we provided guidance to clinicians with respect to their roles during the enrolment process and an independent clinician group was involved to provide detailed verbal information about the trial.

Patient information materials

We identified preconceived beliefs and perceptions among patients that needed to be addressed in the written patient materials, which covered current evidence of treatment effects for surgery and exercise, trial objective and procedures, randomisation process, content of baseline and follow-up sessions, risks and harms, treatment crossover and withdrawal procedures, clinical implications using a balanced a neutral narrative.

Important clinical outcomes

Patient and clinician responses led to three distinct adaptations to the outcomes in the trial protocol. We adopted hip pain and function as primary outcome and implemented hip-related quality of life and functional performance (ie, gait function) as key secondary outcomes. We also included patient acceptable symptom state and muscle strength as exploratory outcomes.

Discussion

Main findings

This novel qualitative patient and public involvement study explored patient, clinician and decision-maker perceptions of a clinical trial evaluating the effectiveness of THA compared with exercise to inform protocol development. Our findings showed that patients with severe hip pain perceived themselves as highly disabled and considered treatment without THA unlikely. Patients expected a fast recovery with complete reduction of hip pain, restored functional performance and return to activities of daily living after THA, while more uncertainty and scepticism about the effects of exercise was expressed. All key stakeholders, except the physiotherapists, deemed exercise as most appropriate for mild-to-moderate stages of hip OA or as an adjunct treatment to THA. We found that clinicians tended to use a management narrative suited to their preferred views on diagnostic eligibility, treatment selection and relative treatment effectiveness. We also identified several facilitators and barriers for surgery and exercise, which mainly included patient age, pain management without analgesics, risk of adverse events, perception of improvement, diagnostic imaging, supervision and habitualised exercise. Patients and clinicians indicated improvements in hip pain and hip function as the most important outcomes to evaluate the effectiveness of surgery or exercise. Based on these findings, we included a parallel observational study investigating the generalisability, developed an enrolment procedure using generic guidance and balanced narrative conveyed by an independent clinician to facilitate communication of clinical equipoise, and adopted change in hip pain and function as the primary outcome in the PROHIP trial protocol.28

Comparison with previous studies and interpretation of findings

In line with our findings, a recent qualitative study also found clear and high expectations for surgery among Swedish patients with knee or hip OA.37 However, several patients reconsidered their treatment options and changed attitudes towards either accepting or declining surgery after participation in a digital non-surgical programme, emphasising the importance of providing sufficient information about management options to facilitate shared-decision-making.37 Our findings also indicated that patients displayed uncertainties about the potential benefits of exercise. This could be driven by uncertainties and lack of knowledge about the effectiveness of exercise among clinicians,38 and due to less than 40% of the patients are recommended or referred to first-line management.13 Based on previous qualitative studies,39 40 recovery expectations among patients in this study were related to the criterion of resolution for surgery and redefinition for exercise, which could indicate that patients accepting participation may differ from those declining participation in our clinical trial in terms of recovery expectations, hip pain and functional status potentially reducing the generalisability of the PROHIP trial.

Our findings showed that clinicians tended to use a management narrative suited to their preferred treatment. This strategy is in contrast to the information needs desired by patients with hip OA during clinical encounters,41 and since clinicians have a considerable influence on the attitudes and beliefs of patients, this may result in misconceptions and uninformed decisions.41 42 This suggests that both orthopaedic surgeons and physiotherapists could sway patient opinions about THA surgery and exercise in either direction during enrolment procedures in the PROHIP trial by highlighting the benefits of their preferred treatment option, while simultaneously accentuating the limitations of the other treatment possibly leading to sampling bias.

In consistency with previous studies,43–45 clinicians in this study displayed conflicting views on the indication criteria for THA. More interestingly, patients in this study perceived findings or progression of hip OA on radiographic imaging to be the primary determinant for THA, although there is a low agreement between hip pain and radiographic hip OA.46 This may suggest that the patients still have an outdated ‘wear-and-tear’ conception of hip OA that contradicts up-to-date insights on pathogenesis, considering OA as a whole-joint disease.47 This misconception of OA has previously been shown to be facilitated by clinicians’ language and explanations,48 which emphasise the need of neutral and evidence-based information during enrolment procedures in the PROHIP trial.

In line with the Osteoarthritis Research Society International recommendations,49 our findings highlighted change in hip pain and function as the most important outcome. Several patient-reported outcome measures (eg, OHS and HOOS) are available to evaluate pain and functional status in patients with hip OA.49 50 However, the OHS appears to have the best validated clinometric properties,50 indicating this as an appropriate primary outcome measure.

Limitations and strengths

Our study has limitations and strengths. A major limitation is that we conducted only one focus group interview for each of the groups with clinicians and decision-makers due to time limitations. This may impact the certainty of achieving data saturation, and thus we may have missed important perspectives in these key stakeholder groups. Another limitation is that 3 out of 14 patients had previously undergone THA surgery, which may have influenced their perceptions, as previous surgery has been suggested to affect patient expectations.37 Furthermore, all patients were scheduled for THA surgery prior to their participation in this study, which further could have primed them to be in favour of surgery. Strengths of our study comprise the variety in the sample of patients interviewed, including females and males of varying ages and different levels of hip pain and disability recruited from both a regional hospital and a university hospital. Additionally, we interviewed three key stakeholder groups involved in receiving and delivering treatment and making decisions about the management of hip OA to provide multiple perspectives and extend the scope of the findings. Lastly, an independent researcher conducted the data analysis to improve neutrality in the interpretation and development of themes and supporting codes due to clinical interests of conflict among the rest of the authors.

Conclusion

Key stakeholders had treatment expectations and beliefs that could possibly affect enrolment procedures resulting in sampling bias and reduced generalisability of our clinical trial. Moreover, facilitators and barriers for surgery and exercise could influence retention rates and treatment crossovers in the trial. Therefore, we implemented three main strategies to improve the methodological rigorousness of our trial protocol. First, we added an observational study investigating the generalisability to address a potential low enrolment rate. Second, we developed an enrolment procedure using generic guidance and balanced narrative conveyed by an independent clinician to facilitate communication of clinical equipoise. Third, we adopted change in hip pain and function as the primary outcome. These findings highlight the value of patient and public involvement in the development of trial protocols to reduce bias in comparative clinical trials evaluating surgical and non-surgical management.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the participating patients, orthopaedic surgeons, physiotherapists and decision-makers. Furthermore, we would like to acknowledge the orthopaedic surgeons from the department of orthopaedic surgery, University Hospital of Southern Denmark, Vejle Hospital and the department of orthopaedic surgery and traumatology, Odense University Hospital for their involvement in the recruitment of patients.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conception and design: TF, IM, LRM, SO, KGI and CM. Analysis and interpretation of the data: TF, KST and CM. Drafting of the article: TF, KGI and CM. Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: TF, KST, SO, IM, LRM, KGI and CM. Final approval of the article: TF, KST, SO, IM, LRM, KGI and CM. Obtaining of funding: TF and KGI. Collection and assembly of data: TF and KST. Development of interview guides: TF. Guarantor: TF

Funding: This work was supported by The Danish Rheumatism Association (R166-5553). The funders were not involved in designing the study, data collection, data management, data analysis, interpretation of the results, writing the article or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this qualitative study, as it was the patient and public involvement strategy for a randomised controlled trial.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Data are available upon reasonable request. Data comprise digital voice recordings of each focus group interview, verbatim transcriptions in Word files and participant-reported questionnaire responses in PDF files. These data are stored in a password-protected hospital server, only accessible to the researchers. Digital audio recordings and individual participant-reported questionnaire responses contain identifiable data and will not be made available on request to maintain participant anonymity. Transcriptions of each focus group interview and the participant characteristics dataset with deidentified participant data may be made available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involved human participants. The Progressive Resistance Training Versus Total Hip Arthroplasty trial was approved by The Regional Committees on Health Research Ethics for Southern Denmark (Project-ID: S-20180158) and registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04070027). This study was approved by The Danish Data Protection Agency (Journal No 18/23994), while no ethical approval was required according to the Danish Act on Research Ethics. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

References

- 1. Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1323–30. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pereira D, Peleteiro B, Araújo J, et al. The effect of osteoarthritis definition on prevalence and incidence estimates: a systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011;19:1270–85. 10.1016/j.joca.2011.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ferguson RJ, Palmer AJ, Taylor A, et al. Hip replacement. Lancet 2018;392:1662–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31777-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rosenlund S, Broeng L, Holsgaard-Larsen A, et al. Patient-Reported outcome after total hip arthroplasty: comparison between lateral and posterior approach. Acta Orthop 2017;88:239–47. 10.1080/17453674.2017.1291100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shan L, Shan B, Graham D, et al. Total hip replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis on mid-term quality of life. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014;22:389–406. 10.1016/j.joca.2013.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beswick AD, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, et al. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000435. 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2019;27:1578–89. 10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Doormaal MCM, Meerhoff GA, Vliet Vlieland TPM, et al. A clinical practice guideline for physical therapy in patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Musculoskeletal Care 2020;18:575–95. 10.1002/msc.1492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goh S-L, Persson MSM, Stocks J, et al. Relative efficacy of different exercises for pain, function, performance and quality of life in knee and hip osteoarthritis: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Sports Med 2019;49:743–61. 10.1007/s40279-019-01082-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hansen S, Mikkelsen LR, Overgaard S, et al. Effectiveness of supervised resistance training for patients with hip osteoarthritis-a systematic review. Dan Med J 2020;67:A08190424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dell’Isola A, Jönsson T, Rolfson O, et al. Willingness to undergo joint surgery following a first-line intervention for osteoarthritis: data from the better management of people with osteoarthritis register. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2021;73:818–27. 10.1002/acr.24486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Svege I, Nordsletten L, Fernandes L, et al. Exercise therapy may Postpone total hip replacement surgery in patients with hip osteoarthritis: a long-term follow-up of a randomised trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:164–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hagen KB, Smedslund G, Østerås N, et al. Quality of community-based osteoarthritis care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016;68:1443–52. 10.1002/acr.22891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008;16:137–62. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Skou ST, Poulsen E, Bricca A, et al. Benefits and harms of interventions with surgery compared to interventions without surgery for musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2022;52:312–44. 10.2519/jospt.2022.11075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ross S, Grant A, Counsell C, et al. Barriers to participation in randomised controlled trials: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 1999;52:1143–56. 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00141-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Frobell RB, Roos EM, Roos HP, et al. A randomized trial of treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tears. N Engl J Med 2010;363:331–42. 10.1056/NEJMoa0907797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Skou ST, Roos EM, Laursen MB, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of total knee replacement. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1597–606. 10.1056/NEJMoa1505467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van de Graaf VA, Noorduyn JCA, Willigenburg NW, et al. Effect of early surgery vs physical therapy on knee function among patients with nonobstructive meniscal tears: the escape randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018;320:1328–37. 10.1001/jama.2018.13308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, et al. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the spine patient outcomes research trial (sport): a randomized trial. JAMA 2006;296:2441–50. 10.1001/jama.296.20.2441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Skou ST, Hölmich P, Lind M, et al. Early surgery or exercise and education for meniscal tears in young adults. NEJM Evidence 2022;1. 10.1056/EVIDoa2100038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Al-Shahi Salman R, Beller E, Kagan J, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste in biomedical research regulation and management. Lancet 2014;383:176–85. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62297-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Crocker JC, Pratt-Boyden K, Hislop J, et al. Patient and public involvement (PPi) in UK surgical trials: a survey and focus groups with stakeholders to identify practices, views, and experiences. Trials 2019;20:119. 10.1186/s13063-019-3183-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crocker JC, Ricci-Cabello I, Parker A, et al. Impact of patient and public involvement on enrolment and retention in clinical trials: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2018;363:k4738. 10.1136/bmj.k4738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Owyang D, Bakhsh A, Brewer D, et al. Patient and public involvement within orthopaedic research: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2021;103:13.:e51. 10.2106/JBJS.20.01573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Adom D, Yeboah A, Ankrah A. Constructivism philosophical paradigm: implication for research, teaching and learning. GJAHSS 2016;4:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Frydendal T, Christensen R, Mechlenburg I, et al. Total hip arthroplasty versus progressive resistance training in patients with severe hip osteoarthritis: protocol for a multicentre, parallel-group, randomised controlled superiority trial. BMJ Open 2021;11:e051392. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shimmin C. Methods of patient and public engagement: A guide: george and faye yee-center of healthcare innovation. 2020. Available: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e57d5337fe0d104c77cca10/t/5ed808e613338b69dcb8f6df/1591216360358/20.05.20+PE+methods+of+Engagement+web.pdf [Accessed Jul 2020].

- 30. Lambert SD, Loiselle CG. Combining individual interviews and focus groups to enhance data richness. J Adv Nurs 2008;62:228–37. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04559.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Krueger RA, Casey MA. Designing and conducting focus group interviews. St Paul, Minnesota, USA; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Paulsen A, Odgaard A, Overgaard S. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Danish version of the Oxford hip score: assessed against generic and disease-specific questionnaires. Bone Joint Res 2012;1:225–33. 10.1302/2046-3758.19.2000076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nilsdotter AK, Lohmander LS, Klässbo M, et al. Hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score (HOOS) -- validity and responsiveness in total hip replacement. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2003;4:10. 10.1186/1471-2474-4-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maggino F. Thematic analysis: a practical guide. Cham: SAGE, 2020. 10.1007/978-3-319-69909-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Attride-Stirling J. Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research 2001;1:385–405. 10.1177/146879410100100307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing research: principles and methods. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cronström A, Dahlberg LE, Nero H, et al. “I was considering surgery because I believed that was how it was treated”: a qualitative study on willingness for joint surgery after completion of a digital management program for osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2019;27:1026–32. 10.1016/j.joca.2019.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nissen N, Holm PM, Bricca A, et al. Clinicians’ beliefs and attitudes to physical activity and exercise therapy as treatment for knee and/or hip osteoarthritis: a scoping review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2022;30:260–9. 10.1016/j.joca.2021.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Beaton DE, Tarasuk V, Katz JN, et al. “Are you better?” a qualitative study of the meaning of recovery. Arthritis Rheum 2001;45:270–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Myburgh C, Boyle E, Lauridsen HH, et al. What influences retrospective self-appraised recovery status among danes with low-back problems? A comparative qualitative investigation. J Rehabil Med 2015;47:741–7. 10.2340/16501977-1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brembo EA, Kapstad H, Eide T, et al. Patient information and emotional needs across the hip osteoarthritis continuum: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:88.:88. 10.1186/s12913-016-1342-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Darlow B, Dowell A, Baxter GD, et al. The enduring impact of what clinicians say to people with low back pain. Ann Fam Med 2013;11:527–34. 10.1370/afm.1518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ackerman IN, Dieppe PA, March LM, et al. Variation in age and physical status prior to total knee and hip replacement surgery: a comparison of centers in Australia and Europe. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:166–73. 10.1002/art.24215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cobos R, Latorre A, Aizpuru F, et al. Variability of indication criteria in knee and hip replacement: an observational study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010;11:249. 10.1186/1471-2474-11-249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dreinhöfer KE, Dieppe P, Stürmer T, et al. Indications for total hip replacement: comparison of assessments of orthopaedic surgeons and referring physicians. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:1346–50. 10.1136/ard.2005.047811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kim C, Nevitt MC, Niu J, et al. Association of hip pain with radiographic evidence of hip osteoarthritis: diagnostic test study. BMJ 2015;351:h5983. 10.1136/bmj.h5983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hunter DJ, Bierma-Zeinstra S. Osteoarthritis. The Lancet 2019;393:1745–59. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30417-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Darlow B, Brown M, Thompson B, et al. Living with osteoarthritis is a balancing act: an exploration of patients’ beliefs about knee pain. BMC Rheumatol 2018;2:15. 10.1186/s41927-018-0023-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lane NE, Hochberg MC, Nevitt MC, et al. OARSI clinical trials recommendations: design and conduct of clinical trials for hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2015;23:761–71. 10.1016/j.joca.2015.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Harris K, Dawson J, Gibbons E, et al. Systematic review of measurement properties of patient-reported outcome measures used in patients undergoing hip and knee arthroplasty. Patient Relat Outcome Meas 2016;7:101–8. 10.2147/PROM.S97774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-070866supp001.pdf (223.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-070866supp002.pdf (88.4KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Data are available upon reasonable request. Data comprise digital voice recordings of each focus group interview, verbatim transcriptions in Word files and participant-reported questionnaire responses in PDF files. These data are stored in a password-protected hospital server, only accessible to the researchers. Digital audio recordings and individual participant-reported questionnaire responses contain identifiable data and will not be made available on request to maintain participant anonymity. Transcriptions of each focus group interview and the participant characteristics dataset with deidentified participant data may be made available upon reasonable request.