Abstract

Objective

To assess the experience of moral distress among intensive care unit (ICU) professionals in the UK.

Design

Mixed methods: validated quantitative measure of moral distress followed by purposive sample of respondents who underwent semistructured interviews.

Setting

Four ICUs of varying sizes and specialty facilities.

Participants

Healthcare professionals working in ICU.

Results

227 questionnaires were returned and 15 interviews performed. Moral distress occurred across all ICUs and professional demographics. It was most commonly related to providing care perceived as futile or against the patient’s wishes/interests, followed by resource constraints compromising care. Moral distress score was independently influenced by profession (p=0.02) (nurses 117.0 vs doctors 78.0). A lack of agency was central to moral distress and its negative experience could lead to withdrawal from engaging with patients/families. One-third indicated their intention to leave their current post due to moral distress and this was greater among nurses than doctors (37.0% vs 15.0%). Moral distress was independently associated with an intention to leave their current post (p<0.0001) and a previous post (p=0.001). Participants described a range of individualised coping strategies tailored to the situations faced. The most common and highly valued strategies were informal and relied on working within a supportive environment along with a close-knit team, although participants acknowledged there was a role for structured and formalised intervention.

Conclusions

Moral distress is widespread among UK ICU professionals and can have an important negative impact on patient care, professional wellbeing and staff retention, a particularly concerning finding as this study was performed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Moral distress due to resource-related issues is more severe than comparable studies in North America. Interventions to support professionals should recognise the individualistic nature of coping with moral distress. The value of close-knit teams and supportive environments has implications for how intensive care services are organised.

Keywords: INTENSIVE & CRITICAL CARE, Adult intensive & critical care, Adult intensive & critical care, ETHICS (see Medical Ethics)

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This multicentre study included UK intensive care units of different sizes and subspecialty capabilities.

The mixed-methods design increased the richness and scope of the data and enabled triangulation of findings.

There is a risk of selection bias if healthcare professionals particularly affected by moral distress were more likely to participate.

The study will not have captured the views and experiences of health professionals who have left the profession because of moral distress.

The study represents a snapshot of moral distress, which may be influenced by specific contextual issues.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the psychological challenges faced by intensive care professionals around the world, including moral distress.1–4 A survey conducted by the British Medical Association found that 78.4% of doctors experienced moral distress during the pandemic.5 The importance of staff wellbeing and combatting staff burnout was recognised prior to the pandemic and is a priority for healthcare services worldwide, including the National Health Service (NHS).6–8 A key contributor to burnout is moral distress.9–13 Moral distress is a constellation of emotional and psychological features that occur when a professional identifies an ethically correct course of action, but is prevented from following this course.14–16 It can also occur in situations where there is uncertainty or conflict regarding the ethically correct action.17–19 It can be deeply damaging to the individual and is associated with a tendency to leave the profession, with a consequent negative impact on patient care.9 20 Some authors have suggested the definition of moral distress is broadened to fully capture its experience and recognise that it may also occur in situations of moral uncertainty.19

The intensive care unit (ICU) is a place where patients with life-threatening conditions may be treated with a variety of invasive and burdensome interventions.21 Highly significant, complex and difficult decisions are made on a regular basis.22 Treatment in the ICU comprises complex interventions that require a multifaceted approach and interaction of a broad multidisciplinary team, which may include pharmacists, physiotherapists, dietitians and other allied health professionals. This environment is highly susceptible to moral distress and hence moral distress among ICU professions is of concern.14 18 23 24

Moral distress was first identified in ICU nurses in North America and has been most frequently studied in this population.14 18 23–25 Similar causes of moral distress have also been found among other ICU professionals, including physicians, respiratory therapists and healthcare students.20 26–30 Despite concerns over ICU staff wellbeing, burnout and moral distress in the NHS, moral distress remains poorly studied in the UK.19 31 32 Moral distress may be affected by specific contextual factors such as availability of resources and model of decision-making for patients lacking capacity. In the UK, the availability of intensive care provision is much less than in North America and the role of proxy decision-makers is much more significant.33–35 These, and other potential differences, may affect how moral distress is experienced by UK health professionals.

This study was performed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and its primary aim was to assess the experience of moral distress among ICU professionals in the UK. Secondary aims were to (a) identify the most common causes of moral distress; (b) determine the relationship between demographic and professional characteristics and moral distress; (c) examine the relationship between moral distress and intention to leave the profession; and (d) identify potential interventions to mitigate moral distress.

Methods

Participants were recruited from four adult ICUs. Sites A and B are large tertiary care hospitals with major trauma and complex multispecialty surgical facilities, and sites C and D are smaller district general hospitals with fewer specialist services. Sites C and D are part of the same organisational trust so some staff work across both sites. Bed capacities of sites range from 12 to 80 beds. All full-time and part-time healthcare professionals working in the ICU were eligible. All grades and clinical professions were included, but students of any profession were excluded.

An anonymous paper questionnaire using the validated Measure of Moral Distress for Healthcare Professionals (MMD-HP) (online supplemental file 1) was distributed between February 2019 and February 2020.36 The MMD-HP is a 27-item questionnaire that uses a Likert scale of 0–4 points to assess the frequency with which situations arise and the intensity of the moral distress caused.25 36 These are summed to produce overall frequency and intensity scores. Individual item frequency and intensity scores are multiplied together to produce a composite item score and these summed to generate an overall moral distress score. A free-text section allows participants to describe additional scenarios not included in the MMD-HP inventory. The MMD-HP also includes two related questions concerning intention to leave the profession now or in the past due to moral distress.36 Participant demographics were collected including profession, grade, age, gender and years of ICU working experience.

bmjopen-2022-068918supp001.pdf (259.1KB, pdf)

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise demographics and moral distress scores. Individual item scores were ranked for comparison. Moral distress scores were non-normally distributed, as found in previous studies,20 31 and hence are presented as medians with IQRs, and non-parametric statistical tests were used (Wilcoxon signed-rank, Kruskal-Wallis). A sample size requirement calculation was not performed as there were inadequate UK data using the MMD-HP. Multiple linear regression was used to investigate the relationship between age and ICU experience and moral distress scores. Multiple logistic regression models were fitted to determine the association between moral distress scores and tendency to leave the profession. Covariates were prespecified demographic and professional variables, with binary classification used for profession (nurse vs other) and hospital type (tertiary care vs district general). Discrimination of logistic regression models was assessed using area under the receiver operator curve (ROC AUC). For tendency to leave a previous position, an ordinal logistic regression was used in accordance with the ordinal dependent variable. Statistical analyses were performed using R V.3.6.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) with the code for analyses available on request.

Questionnaire respondents willing to take part in an interview included their contact details on the returned questionnaire and from those respondents; potential interview participants were purposively sampled for hospital, profession, grade and overall moral distress score using a maximum variation approach. Written informed consent was obtained prior to interview. Semi-structured interviews with an interview guide (online supplemental file 2) were conducted face to face between July 2019 and February 2020 and explored participants’ experience of moral distress, the situations that cause it, strategies they use to cope with it and their views on possible interventions to alleviate moral distress. Interviews lasted approximately 30 min and were audio-recorded then transcribed verbatim. Interviews were conducted until no new themes emerged from the data. The Framework Method of thematic analysis was used.37 Transcripts were loaded onto NVivo and data initially organised into content areas informed by the study aims: experience of moral distress and coping with moral distress. Within each area, two main categories were explored: precipitating factors/causes of moral distress and the response to distress; coping strategies and interventions to support coping. This is described in online supplemental figure 1. Data within each content area were then reread and coded inductively, and codes compared and grouped to develop themes and subthemes. All transcripts were coded by AJB with 30% independently coded by AMS. The codes and emerging themes and subthemes were discussed at regular analysis meetings to improve the analysis validity and trustworthiness.

bmjopen-2022-068918supp002.pdf (52.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-068918supp003.pdf (132.8KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

The study received contributions from the patient and public representatives from the University Hospitals Birmingham Clinical Research Ambassador Group. The members supported the proposed study and saw the potential for the work to benefit staff wellbeing and patient care. The group contributed to the study design, development of study documentation, including the protocol and participant information sheet, and the dissemination plan.

Results

Two hundred and twenty-seven questionnaires were returned from a total of 772 questionnaires distributed across all sites, giving an overall response rate of 29.4% (site A 28.3%, site B 24.0%, sites C and D 34.6%). Participant demographics are described in table 1. Forty-one of the 227 participants completing the paper questionnaire indicated a willingness to take part in an interview, 21 were contacted with an invitation and further information about the interview study and 15 agreed to be interviewed. Interview participant demographics are summarised in online supplemental table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| Characteristic | N=227 |

| Mean age±SD (years) | 38.1±10.3 |

| Gender, no (%) | |

| Female | 165 (72.7) |

| Male | 52 (23.0) |

| Not answered | 10 (4.4) |

| Profession, no (%) | |

| Nurse | 145 (63.9) |

| Doctor | 40 (17.6) |

| Physiotherapist | 9 (4.0) |

| Advanced critical care practitioner | 8 (3.5) |

| Pharmacist | 2 (0.9) |

| Not answered | 23 (10.1) |

| Mean ICU experience±SD (years) | 10.1±9.2 |

ICU, intensive care unit.

The quantitative results from the MMD-HP are presented first, followed by the qualitative results grouped into experience of moral distress and coping with moral distress.

Moral distress items

Fourteen questionnaires were excluded due to missing responses preventing calculation of the moral distress score. Items are ranked by compositive score for nurses and doctors in online supplemental table 2. The most highly scored items by both nurses and doctors related to delivering aggressive treatment that was perceived as futile or not in the patient’s best interests. Other highly ranked items related to lack of resources, caring for more patients than is considered safe, excessive documentation, lack of administrative support and abusive patients/family members compromising care. Nurses generally rated moral distress frequency and intensity more highly than doctors. Only 4 of the 27 items had a greater composite score for doctors over nurses and there was no commonality in the root causes of these scenarios.

Moral distress score associations

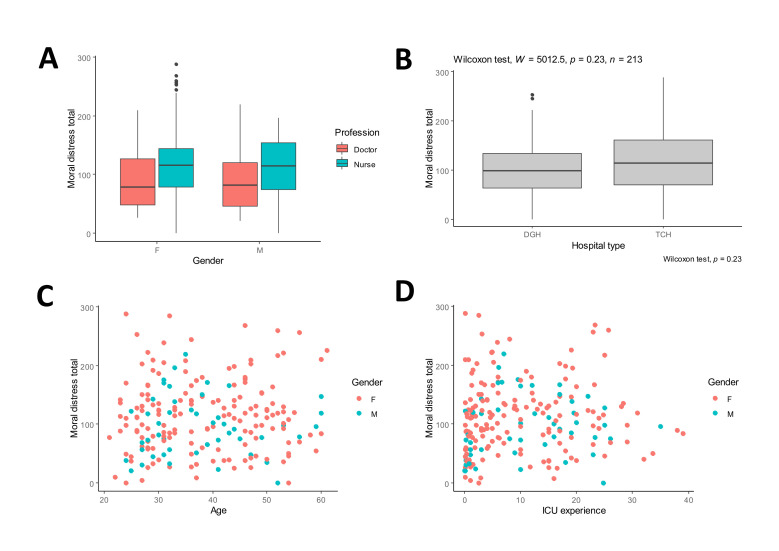

Total composite moral distress scores were positively skewed with a median score of 108 (IQR 78.2, range 0–288). The relationship between overall moral distress score and demographic characteristics is summarised in figure 1. Moral distress was greater in women than men (111.5 (IQR 75.5) vs 94.0 (IQR 69.3), W=4755.5, p=0.043) and was significantly influenced by profession (H=11.89, p=0.018) with nurses reporting greater moral distress than doctors (117.0 (IQR 65.5) vs 78.0 (IQR 73.0)). There were differences in the distribution of gender across professions (nurse: 83.7% female; doctor: 40.0% female). Differences in moral distress between nurses and doctors persisted after statistical adjustment for differences in gender across professions (p=0.020). There was no relationship between overall moral distress score and participant age and ICU experience. This was confirmed with multiple linear regression where an interaction effects model of age and ICU experience against overall moral distress could only explain less than 1% of the variation in moral distress (adjusted R2 0.0089). Median moral distress scores were higher in larger tertiary care hospitals than district general hospitals; however, this did not reach statistical significance (114.5 (IQR 91.8) vs 98.0 (IQR 69.9), W=5012.5, p=0.23).

Figure 1.

Relationship between moral distress total and demographic/professional variables. N=213 as 14 questionnaires excluded due to missing responses preventing calculation of the moral distress score.

Intention to leave the profession

Seventy-one (33.3%) participants indicated their intention to leave their current post due to moral distress. Twenty-eight (13.1%) participants reported they had left a previous post due to moral distress and 101 (47.4%) reported they had considered leaving a previous post due to moral distress but did not leave. Overall, moral distress was significantly greater in those intending to leave their current post (135.5 (IQR 84.5) vs 88.9 (IQR 65.3), W=2771.5, p<0.0001) and this difference was confirmed in both univariate and multiple logistic regression analyses. Logistic regression model variable ORs are summarised in table 2. Multiple logistic regression included profession, gender, hospital type, age and ICU experience as covariates and had good discrimination (ROC AUC 0.722) and ability to predict intention to leave (online supplemental figure 2). Adjusted OR for moral distress score against intention to leave was 1.011 (95% CI 1.005 to 1.017, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Logistic regression model variables and association with intention to leave current post in univariable and multivariable analyses

| Variable | Univariable OR (95% CI) | P value | Multivariable OR (95% CI) | P value |

| Age (per year) | 0.995 (0.966 to 1.024) | 0.739 | 0.982 (0.929 to 1.036) | 0.516 |

| ICU experience (per year) | 1.005 (0.973 to 1.038) | 0.762 | 1.009 (0.929 to 1.072) | 0.781 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Female | 1.289 (0.645 to 2.679) | 0.482 | 0.668 (0.271 to 1.630) | 0.375 |

| Profession | ||||

| Other | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Nurse | 3.013 (1.442 to 6.810) | 0.00496* | 3.023 (1.243 to 8.014) | 0.0188* |

| Hospital type | ||||

| District general | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Tertiary care | 1.17 (0.648 to 2.132) | 0.605 | 0.953 (0.466 to 1.948) | 0.895 |

| Moral distress total (per unit) | 1.011 (1.006 to 1.017) | 0.0000327* | 1.011 (1.005 to 1.018) | 0.000883* |

Italics and * indicate statistically significant association.

ICU, intensive care unit.

A greater proportion of nurses were considering leaving their current post due to moral distress than doctors (37.0% vs 15.0%). Nurses had significantly greater odds of reporting an intention to leave the profession in both unadjusted (OR 3.013, 95% CI 1.442 to 6.810, p<0.01) and adjusted analyses (adjusted OR 3.023, 95% CI 1.243 to 8.014, p=0.019). There was no significant association between gender and intention to leave the profession in either unadjusted or adjusted models.

Moral distress score was significantly associated with the ordinal outcome of leaving a previous post in unadjusted and adjusted analyses (OR 1.010, 95% CI 1.006 to 1.015, p<0.0001; adjusted OR 1.009, 95% CI 1.004 to 1.014, p=0.001). Female gender and nurse profession were not significantly associated with leaving a previous post in adjusted analyses. Ordinal logistic regression model variable ORs are summarised in online supplemental table 3.

The qualitative results from interviews are reported below and are reported by content area: experience of moral distress and coping with moral distress.

Experience of moral distress

During analysis, two areas of experience were considered: precipitating factors/causes of moral distress and the response to distress. Three distinct themes emerged in relation to causes of moral distress. The dominant theme was of moral distress due to a perception that care provided was not in the patient’s best interests. Participants talked about a feeling of helplessness in the face of seemingly endless and potentially futile care, delivering care that disregarded patient wishes, and external pressure to provide care that is seen as not in the patient’s interests. The two other themes in this area were resource constraints compromising care and inability to protect more junior staff. Responses to moral distress were categorised in the following themes: negative emotional response; avoidance of patient and family; impact on future career decisions; moral distress changing over time. Experiencing moral distress led to a range of negative emotions and behaviours. Frustration and anger were the most frequently described emotions. Experiencing moral distress could also lead to avoidance of interaction with patients and their family. Some participants described this behaviour as ‘self-protection’. Experiencing and coping with moral distress had led some participants to question their future in intensive care. Junior doctors considering careers in intensive care had changed course after experiencing and struggling to cope with moral distress themselves or observing the impact on more senior colleagues, contemplating whether this was something they wanted for themselves. Some participants suggested moral distress got better with increasing ICU experience as they were better able to rationalise situations, manage emotions, and/or had improved coping strategies and resilience. Conversely, others felt that moral distress got worse over time, either because they were more aware of situations where patient care could be better, or because their increasing age made cases more personally relatable. Illustrative quotes for these themes within experience of moral distress are reported in table 3.

Table 3.

Illustrative quotes from participant experience of moral distress

| Content area | Theme | Quotation example |

| Precipitating factors/causes of moral distress | Endless care | ‘And that kind of torture of not knowing, it’s not like there is something difficult to be done and we know what it is, the fact that it just drags and drags and drags on like this with no kind of end in sight, you know, like motorway traffic and you don’t know, you know if it’s just off the next junction and then you think I can bear it but if this is going to be all the way to Manchester, it’s that sort of, it’s difficult.’ (Doctor 5) ‘But the families have lost completely that narrative that this is a child that is going to die or an adult that is going to die soon. Exactly the same way with cancer patients, you know, ultimately someone has got to tell them that their cancer is incurable. That message is lost from these adults and so then the problem is you are starting from a point where these families and individuals have had massive amounts of aggressive interventional care,…. And they have lost the narrative that this is a child ultimately with a life limiting illness.’ (Doctor 4) |

| Disregard for patient wishes | ‘…he (the registrar) went to a patient on the ward and had a long chat with the patient …and she basically said, I am done, I want to go home. And I was like okay right, this is a very senior doctor so that’s what she said, that’s her wishes, and then the next thing I know like she’s coming to ITU, getting lined and up and then she died in ITU like five days later or something.’ (Doctor 3) ‘It was very distressing actually, really distressing because his motives (the consultant) were not about care and comfort for the patient.’ (Nurse 6) |

|

| External pressures to encourage delivery of perceived futile care | ‘I just thought the bit that I didn’t understand was like multiple consultants were saying they didn’t think she was going to get well and that seemed to be like the collective ITU opinion but we still admitted her because it was what oncology wanted.’ (Doctor 3) ‘…her family throughout have been, what’s the word? I don't want to say unreasonable but, they have been, they have resisted all honest conversation to the point now that the conversations that we have with them are not honest because they insist that they are not. Just really falsely optimistic despite all the preamble conversations … I feel like somebody should be able to stop it but I don’t know who that might be… So then the kind of whole relationship has deteriorated to nothing between the family and the medical team.’ (Doctor 5) |

|

| Resource constraints compromising care | ‘And we only had the capacity to see one of them. And the one that we saw was the sick person but then didn’t survive until the following day and the one we didn’t see ended up being ventilated for quite some time really, and it felt like we didn’t direct our resources to the right place there.’ (Nurse 5) ‘So for example we had a lady who had a devastating intracranial haemorrhage, she was coming into the unit for neuroprognostication probably the organ donation process. We were stuck with her for hours and it was all the kind of chaos as it is in resus, [with] a grieving family… stuck by this bedside in resus which was like a zoo, there was building work going on, the whole thing was so undignified… They couldn’t get the bed [in ICU] because they couldn’t get the patients out, you know, everybody is stuck, stuck, stuck and at the end of it I was stuck with this patient in this awful environment with her grieving family, just thinking I can’t, this is just unbearable. It was just horrible.’ (Doctor 5) |

|

| Seniors unable to protect staff | ‘I would say the things that preoccupy me are not necessarily clinical things, they are more about my team and if I am concerned about the wellbeing of my team I will often worry about, you know, I don’t know what to do about this situation, I don’t know how to improve things …There isn’t anything I can physically do, I can’t magic people to come and help, and the staff appreciate that but it’s still kind of, you worry for the people that are there continuing to work and their wellbeing and their stress levels.’ (Nurse 5) | |

| Response to moral distress | Frustration, anger | ‘I do find it stressful, I do get quite angry, not in the moment but often, you know, I feel very grumpy or angry walking back to the ITU having done it all. There is just a great frustration.’ (Doctor 4) ‘And I feel like almost angry at the family for, and then that doesn’t feel right, that feels like a really unwelcome feeling to feel angry at this poor family who have had a terrible thing happen to them and just love their loved one and I kind of see that. But it just goes on and on and on and it feels like torture for her, for everybody that looks after her, and it feels like something criminal, you know, it feels worse than.’ (Doctor 5) |

| Upset | ‘So at the time I feel like there are tears like behind my eyes and I will feel that kind of like ache in your throat that you get and I feel nauseated and I just feel like just exhausted by it really, you know, you keep trying to apologise to the family, trying to look after the patient as best you can. You know, try and apologise, you know, just kind of try to soften, you try to be the buffer between the situation and the patient and the family but you suffer for that don’t you?’ (Doctor 5) ‘Yeah definitely, we all sat in one of the side rooms together and everyone had the opportunity to express their feelings, most of us had a good cry, you know, that sort of thing.’ (Nurse 2) |

|

| Deflation, dissatisfaction | ‘So when I was driving home I felt a bit deflated like I hadn’t really done, like I hadn’t really done the very best that I could have done although it was quite a messy, it was a bit of a messy situation. And of course lots of clinical situations are very messy, especially when there is more than one team involved and that sort of thing. So I just had a vague sense of feeling dissatisfaction and I should have really known that information before.’ (Nurse 2) | |

| Worry | ‘I would then go home and pick apart my decisions and ruminate and kind of sabotage myself. And then I can’t sleep and then I go to work the next day knackered and I worry that my decision making is worse then and then you spiral don’t you I think.’ (Doctor 5) | |

| Relatable case | ‘You know, you wouldn’t want if for yourself or your own family and yet it keeps going on, you know, it’s kind of difficult to witness really. And you feel a bit like a perpetrator of it I think.’ (Doctor 5) | |

| Avoidance of interaction | ‘…my sympathy for the family has deteriorated over time… They come in and I don’t like to look at them, so I don’t look at them. And that feels inhuman and I think what’s become of me, where is my humanity? But it’s not that I don’t care it’s just the situation has got beyond me, that I just think I don’t know how to respond to this anymore so I just don’t look… that’s terrible isn’t it? So it is hard, it’s really hard.’ (Doctor 5) ‘Yeah, even in handover she is kind of not mentioned really… yeah definitely emotionally like for self-protection I have kind of switched off a bit.’ (Doctor 5) |

|

| Impact on career decisions | ‘So the NHS for that I think that the amount of trauma that, or emotional trauma that we see that we absorb, that we take on, we don’t get the right amount of, in our particular role it has a shelf life of two to four years.’ (Nurse 3) ‘I have previously actually thought about dual specialising in anaesthesia and intensive care. But my most recent job in intensive care has most definitely made me decide not to. But one of the reasons being in my experience has just been, I don't think it’s one I would able to continue and a career that I would be able to continue and still actually remain vaguely sane… That’s why a lot of us don’t really want to go into it, because it’s soul destroying.’ (Doctor 2) |

|

| Changes over time | ‘The more experience you have definitely the easier it is but I have been really conscious of the burden that the job has on me and kind of being careful and protecting myself. Because if you want longevity you have to understand what it is doing to yourself and have ways of dealing with that.’ (ACCP 2) ‘I don’t know whether this is just me, but personally I feel like I am less able to cope with it now, I get far more emotional now and upset by things then I did when I first started working in critical care… I think probably because of my age, I relate to a lot of the patients now that are either in a similar age range to myself or younger patients that we have that are in a similar age bracket to my children, it really resonates.’ (Nurse 5) |

ACCP, advanced critical care practitioner; ICU, intensive care unit; ITU, intensive treatment unit; NHS, National Health Service.

Coping with moral distress

Two areas were considered: coping strategies for moral distress and interventions to support coping with moral distress. Participants described a range of strategies for coping with moral distress, tailoring their strategy to the particular situation. Strategies could be classified as internally or externally focused. Internally focused strategies included personal reflection, mental compartmentalisation and self-care techniques. Personal reflection was commonly reported as a way of making sense of the distress experienced; however, mandatory reflection was less helpful than when it occurred in an organic way. Externally focused strategies include informal discussions with colleagues, talking to their friends/family and more formal debrief sessions. The most frequently described and highly valued coping strategy involved talking with colleagues informally, such as chatting in the coffee room. The culture of the team appeared critical to allow informal talking to be effective. Participants valued a supportive environment with a close-knit, honest and actively caring team. Smaller teams where staff knew each other well were reported as more supportive compared with larger teams where there was more movement of staff. Acknowledgement from a senior team member that a case was particularly distressing was powerful and reassuring. Conversely, seniors not wanting to engage in conversations was reported as detrimental to coping with moral distress.

Participants were asked about interventions to support coping with moral distress. Generally, participants felt that a personalised approach tailored to the particular situation was needed. Formal approaches were seen as more valuable for junior staff who perhaps did not have the same developed coping strategies. In general, however, participants felt that informal support would be more authentic, accessible, faster acting and efficacious. Facilitated discussion was suggested as a way of enhancing the effectiveness of informal talking with colleagues. Multiple participants proposed identifying a nominated group of senior and/or experienced ICU staff who could provide support and advice on an ad hoc basis with allocated time to deliver this role. Participants highlighted the importance of organisations valuing the wider working environment in supporting staff to cope with distress. Ensuring avoidable stresses were removed or reduced would enable staff to have more emotional and cognitive capacity to deal with the moral challenges that they faced in their work. For example, adequate car parking and responsive services, such as information technology, payroll and human resources, were all cited as areas that would improve overall staff wellbeing.

Illustrative quotes for these themes from coping with moral distress are reported in table 4.

Table 4.

Illustrative quotes from participant coping with moral distress

| Content area | Theme | Quotation example |

| Coping strategies | Personal reflection | ‘I think I just reflect constantly anyway, I don’t know if everyone does, I imagine most of us do… I generally just do it in my head when I’m exercising I’ll tend to think about, that went well, or that didn’t go quite so well, what can I do to improve that next time. No, it’s not something I think, right I need to go and meditate because that’s upset me or whatever.’ (Other 2) ‘Yeah I think the moment you make anything mandatory I think you lose quite a lot of the value… So I think it has to be voluntary, I think it has to be something people do because they recognise it for its own value.’ (Doctor 3) |

| Mental compartmentalisation | ‘So I tend to compartmentalise work and home, because I have had periods of time before where I have been really, really distressed and it just, it’s no good for your home life, so I’ve kind of, I box things off. I don’t know if that is the right way of doing it or not but that’s what I tend to do.’ (Nurse 2) ‘I drive quite a long distance to work and back, so mine sort of goes in the car. I have a little refection and sometimes a little blurt in the car and then by time I’ve walked through the house, picked the dogs up and walk out, it’s gone.’ (ACCP 1) |

|

| Self-care | ‘And then I think it’s just trying to keep your own health kind of optimal so that you are physically healthy it makes the difference to being mentally healthy I think. If you are physically healthy it gives you a bit of robustness.’ (ACCP 2) ‘Yeah I do, I tend to go for long walks I take my dogs, go off with my dogs on lots of long walks and fresh air and open space and I don’t mind admitting copious quantities of wine over that weekend. And yeah, that’s probably how I, fresh air, exercise, wine.’ (Nurse 2) |

|

| Informal talking with colleagues | ‘I will talk to either another senior registrar so peer support, that can be very helpful or, you know, consultants that I get on with. So in those circumstances I am looking for someone who is, again it’s not kind of, it’s not an explicit thought process but I will want someone who I know is on a similar wavelength and will be understanding. Oh yes, someone who, yes someone who’s opinion I value.’ (Doctor 4) ‘And it was really useful actually to see people that you are a little bit in awe of sort of like scary Band 7s, it was quite useful to see them sort of actually sort of coming down to our level, the ground level and being distressed by things they have seen… so it was good to see, I was so surprised to see this one particular Band 7 in floods of tears and I thought oh you are human, that’s awful isn’t it?’ (Nurse 2) |

|

| Supportive environment | ‘I think what you need is a culture where that’s available as and when you need it. And so you know it’s alright to sort of say, you know, to some of my bosses or some of my colleagues, actually something shit has just happened can we go and have a cup of tea and a chat… But for me I think that’s probably a better approach, is to have the culture where that’s okay and then you can go and find what you want from who you want.’ (Doctor 4) ‘I’ve worked in small hospitals and large hospitals as a nurse and I do think generally [support is better] in a smaller hospital… you’ve got a smaller team so you know each other better and when you’ve got a smaller team, smaller teams do tend to stay put more. Whereas bigger hospitals obviously you might not know the staff that you’re on with and things like that. …how are you going to have support from somebody that’s an agency who’s only there for the day.’ (ACCP 1) ‘I think our larger critical care units are not a good idea… I think the bigger units are less personalised and it’s hard to maintain and retain a proper team, so it’s better to keep the units down to 15 or 20 beds and try and have core teams that don’t rotate.’ (ACCP 2) |

|

| Informal talking with friends and family | ‘I think because I live with my husband who has no knowledge whatsoever of what goes on in this kind of environment, I do talk about work when I get home, but I don’t tend to sort of go into that kind of nitty gritty with him because, I don’t know really, I just don’t. I think he finds it a bit boring to be honest with you, it’s not anything he particularly knows about.’ (Nurse 2) ‘(I) have peer support, good family support and my wife is an anaesthetist as well so I can talk through stuff with her easily and all the family and friends, I have got lots of friends who are various members of the medical profession.’ (ACCP 2) |

|

| Formal debrief | ‘I have experienced both those both (formal and informal discussions) and I think for the type of a major clinical incident then I think that a formal sort of debriefing top down sort of debriefing to show that you are supported by your sort of managers is probably better for something that is really awful. But working in critical care you are going to come across something that is pretty awful every day. So I think that we as a sort of cohort of nurses just tend to talk to each other informally most of the time.’ (Nurse 2) ‘Unfortunately, the physical logistics of doing things like the debriefs are virtually impossible, they are not easy, they are really not. You know what it’s like you have a unit full of patients, you've got a million jobs to do, you’ve got five families to talk to and discuss it all with, trying to fit debriefs in around that as well, before you know it’s 5:30 and your team have gone home or are hoping to get home on time.’ (Doctor 2) |

|

| Interventions to support coping | Formal and structured support | ‘But getting somebody in to discuss things or an away day or a coffee morning and things, sometimes you don’t get the right people going to that do you?… What about the group of staff that don’t go on the away day, that drops morale because they didn’t go on it. And also they’re working with locums and agency, so they’re actually having a bad day then. So you can get animosity even just doing something like that.’ (ACCP 1) ‘Well ideally a psychotherapist or somebody who has that professional backing or professional background to be able to support that because otherwise talking can only go so far.’ (Nurse 3) |

| Group-based approach | ‘You’re potentially opening yourself up to a whole room of strangers is a bit like alcoholics anonymous, some people wouldn’t be up for that.’ (Other 1) ‘…or, you know. I think you don’t want to criticise where you work and knowing that it can come back to you and there is that feeling the more junior you are the easier it is for you to go isn’t it, I think there is still that.’ (Nurse 6) |

|

| Non-healthcare background | ‘Yes, so she came in, to kind of give us techniques but she just didn’t really relate to healthcare it was more outside. So it just didn’t relate to any of us… They can’t relate it to us or how it would actually be working in a hospital.’ (Nurse 1) ‘I think it would be good to talk to people who know the environment because you don’t have to explain all of that do you, you can just go in at a level of like mutual understanding and then you can just talk about the problem.’ (Doctor 5) |

|

| Informal approach | ‘What I would say is that where, I don’t know, I have always found that the organic process has always been the most helpful. I don’t know whether that’s because in a sense you kind of have more control over who you go and chat to or whether it just has more authenticity.’ (Doctor 4) | |

| Nominated ICU staff for support | ‘I do wonder whether a facilitated system would be useful because I think the danger can be that if you’ve got people who are distressed talking to each other about the distress they can actually spiral down further… Rather than lift themselves out so a moderated sort of peer review or peer forum I guess would be helpful.’ (Doctor 1) ‘… have an identified person, say go to Adam, if you have got a problem go to Adam or its Adam’s month to deal with all the grief or whatever. To say there is a role and you get a small bit of time for the role, the role exists in this place, it’s paid for, it’s budgeted and that’s when it happens and get the right people to do it.’ (ACCP 2) |

ACCP, advanced critical care practitioner; ICU, intensive care unit.

Lack of agency

Throughout participant descriptions of the various facets of moral distress, a key overarching theme of lack of agency emerged. This was consistent across professions and persisted through different contexts of moral distress, descriptions of scenarios, responses to moral distress, and coping strategies and interventions for moral distress. This powerlessness and sense of a lack of control appears central in the development of moral distress and how individuals respond to and cope with it.

I came away feeling a bit guilty but equally knowing that there was nothing I could have done to avoid that. (Other 2)

Yeah the more you reflect on it, maybe it’s better not to reflect too heavily on it… your hands are essentially tied aren’t they? (Advanced Critical Care Practitioner 2)

I feel like somebody should be able to stop it but I don’t know who that might be. (Doctor 5)

Discussion

This is the largest study of moral distress in UK ICUs to date and the first to use a multi-centre approach with assessment across ICU professions. Included ICUs were at both district general and teaching hospitals and were of varying sizes and subspecialty capabilities. Moral distress was widespread across included sites and across ICU professions. Moral distress scores were highest in situations related to delivering aggressive treatment that was perceived as futile or not in the patient’s best interests, closely followed by lack of resources compromising delivered care. Interview data also identified inability of senior staff to protect their juniors as a cause of moral distress. Moral distress was significantly worse in nurses and was not influenced by age or years of ICU experience. The multiple negative emotions engendered by this repeated experience can lead to withdrawal from engagement with patients and families, likely leading to poorer clinical care, and ultimately to withdrawal from intensive care as a career choice. There was a strong association between higher moral distress scores and intention to leave a current post, or leaving a previous post highlighting the impact moral distress may have on ICU staff retention. It is concerning that one-third of participants reported an intention to leave their current post due to moral distress. Interview participants described a range of individualised coping mechanisms when experiencing moral distress. In general, informal support mechanisms were preferred to more formal arrangements. This study took place before the COVID-19 pandemic and it is possible the immense pressure on UK ICU services has had a further impact on the experience of moral distress. This should be recognised when considering how this study reflects the current welfare of UK ICU professionals.

The only other quantitative study of moral distress in UK ICUs to date also found moral distress was significantly associated with an intention to leave a post, a finding consistent with international literature.16 20 31 38 It is increasingly clear that the impact of moral distress appears damaging to staff retention and should be considered by employers.10 16 Colville et al31 were unable to detect a difference in moral distress scores between nurses and doctors and highlight the confounding impact of gender differences. Our larger study found that moral distress is greater in nurses and this difference remained statistically significant after accounting for differences in gender distributions. This finding is consistent with international studies showing that nurses report greater moral distress than doctors.20 36 38 It is also notable that nurses had a significantly greater intention to leave the profession, including in adjusted analyses. Indeed, 37% of nurses included in our study indicated they were considering leaving their current post due to moral distress, compared with 15% of doctors. This is consistent with research from Canada,20 and is a concerning finding that potentially has staff retention and workplace planning implications.

Compared with similar research in the USA also using the most up to date measure of moral distress, overall moral distress scores were higher in our study, and this was consistent across all professional subgroups.36 Almost all highly ranked individual item composite scores were higher in our study than that in the USA. This was most notable for resource-related items, specifically compromised care due to lack of resources/equipment/bed capacity, where the composite moral distress score was substantially higher in our UK study. This was ranked the second highest item by moral distress score in our study for both doctors and nurses, but ranked fifth in the comparative USA study. This could reflect differences in healthcare delivery and poorer provision of critical care beds per population in the UK.33–35 This high signal of moral distress raises a worrying concern that suboptimal care may be being delivered due to resource constraints. This study is unable to determine if this is occurring, nevertheless the high levels of moral distress due to resource-related issues should be noted.

Our finding that moral distress occurs frequently in situations related to delivery of aggressive treatment perceived as futile or not in the patient’s best interests is consistent with international research using the previous versions of the quantitative moral distress scale.14 25 31 It is also supported by other qualitative studies.18 19 26

It is increasingly clear that moral distress is widespread and detrimental within intensive care.39–41 A key question is therefore how to prevent and mitigate it. Given our finding of lack of agency as a driver of moral distress, one preventive strategy would be to improve agency and empower clinical staff to speak out. Hamric and Epstein report how a moral distress consultation service was successful in empowering staff in situations where they had felt unheard or powerless.42

Our qualitative findings suggest that interventions aimed at combating moral distress require a tailored approach that recognises the individualistic nature of coping with moral distress. Individualised informal support appears the most common coping strategy and is often effective if it takes place in an organisational culture that provides a supportive environment. Our participants frequently reported that smaller ICUs were more supportive and more able to permit informal coping compared with larger ICUs. This is noteworthy as UK intensive care services move towards regionalisation with larger ICUs on a ‘hub and spoke’ model to meet increasing care demands.43 It may be possible to replicate the benefits of smaller units at larger ICUs by working in smaller, close-knit teams caring for ‘pods’ of beds within the larger ICU. Embedding senior professionals who are nominated to facilitate discussion to cope with moral distress within these teams could be beneficial. Supporting effective coping could produce a positive feedback loop that encourages staff retention, therefore promoting a close-knit team and allowing formation of the staff relationships which appear so important in facilitating informal coping. Conversely, failure to control moral distress could produce a negative spiral due to its deleterious effects on career decisions.14 16 20

Our study has several limitations. First, the study is at risk of selection bias. Those experiencing high levels of moral distress may be unwilling to participate and relive their experiences, or alternatively those with low levels of moral distress may not appreciate its value and not take part. This may be reflected in the response rate. We only included those currently working in ICU and so cannot capture those that may have left ICU due to high levels of moral distress. We attempted to improve external validity by including multiple ICUs which had different operational characteristics. Purposive sampling ensured the interview sample reflected the total questionnaire sample and included representation of all hospitals, a range of professions, seniority, age and gender. Second, our study includes more nurses than other professions, however this reflects the distribution of ICU professions.21 Third, this study is a snapshot and may be influenced by how the participant is feeling at that time, or what clinical cases are present on their unit. Moral distress may be a reactive process and be influenced by experiences at that point in time.44 It is possible that moral distress may fluctuate and change as the clinical case-mix within an ICU changes. It remains unknown how moral distress changes over time and further study is warranted.

This study highlights the widespread nature of moral distress in UK ICUs and across ICU professions. Moral distress is worst in situations related to delivery of aggressive treatment perceived as futile or not in the patient’s best interests, and this finding is consistent with previous international research. Moral distress in UK ICUs appears to be more frequently experienced than in North America, in particular moral distress related to resource constraints. Moral distress is greatest in nurses and is independently associated with an intention to leave the profession, both at present and in the past. This study took place before the COVID-19 pandemic and even at that time, one-third of participants were considering leaving their current position. Moral distress is therefore a pressing problem for NHS trusts and policymakers seeking to retain and support an effective ICU workforce. In order to provide a healthy and sustainable intensive care workforce for the future, it will be important to acknowledge moral distress and provide environments that are supportive to staff and facilitate coping strategies. Policy decisions on the provision of intensive care services should take into account the importance of supportive environments and close-knit teams in facilitating coping with the almost inevitable moral distress and psychological pressures associated with working in intensive care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the expert statistical support provided by Dr Georgios Bouliotis. We sincerely thank the healthcare professionals for voluntarily participating in this research and giving their time for interviews. The National Institute of Academic Anaesthesia kindly supported this study with an Association of Anaesthetists/Anaesthesia research grant awarded to AJB. The NIHR Clinical Research Network adopted this study onto their portfolio, and the support of the research teams at all sites is greatly appreciated. We are very grateful for the PPI input and contributions made by the University Hospitals Birmingham Clinical Research Ambassador Group.

Footnotes

Twitter: @AdamBoulton17

Contributors: Study design—AJB, JY, A-MS and CB. Study conduct—AJB, JY, A-MS and CB. Data analysis—AJB and A-MS. Drafting of the manuscript—AJB and A-MS. Review of the manuscript—AJB, JY, A-MS and CB. Guarantor—AJB.

Funding: This work was supported by an Association of Anaesthetists/Anaesthesia research grant administered by the National Institute of Academic Anaesthesia (grant number NIAA19R102).

Competing interests: AJB is supported by an NIHR-funded Academic Clinical Fellowship.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants but an Ethics Committee(s) or Institutional Board(s) exempted this study. Approvals were gained from the NHS Health Research Authority (IRAS: 238379). University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust acted as study sponsor. Local approvals from each study site's research and development department were sought. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Dzau VJ, Kirch D, Nasca T. Preventing a parallel pandemic-a national strategy to protect clinicians' ’ell-being. N Engl J Med 2020;383:513–5. 10.1056/NEJMp2011027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenberg N, Docherty M, Gnanapragasam S, et al. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ 2020;368:m1211. 10.1136/bmj.m1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shapiro J, McDonald TB. Supporting clinicians during covid-19 and beyond-learning from past failures and envisioning new strategies. N Engl J Med 2020;383:27.:e142. 10.1056/NEJMp2024834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheather J, Fidler H. Covid-19 has amplified moral distress in medicine. BMJ 2021;372:28. 10.1136/bmj.n28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.British Medical Association . Moral distress and moral injury: recognising and tackling it for UK doctors. 2021.

- 6.NHS Health Education England . NHS staff and learners’ mental wellbeing commission report. 2019.

- 7.Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, et al. Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: A systematic review. PLoS One 2016;11:e0159015. 10.1371/journal.pone.0159015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McClelland L, Plunkett E, McCrossan R, et al. A national survey of out-of-hours working and fatigue in consultants in anaesthesia and paediatric intensive care in the UK and ireland. Anaesthesia 2019;74:1509–23. 10.1111/anae.14819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lamiani G, Borghi L, Argentero P. When healthcare professionals cannot do the right thing: A systematic review of moral distress and its correlates. J Health Psychol 2017;22:51–67. 10.1177/1359105315595120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fumis RRL, Junqueira Amarante GA, de Fátima Nascimento A, et al. Moral distress and its contribution to the development of burnout syndrome among critical care providers. Ann Intensive Care 2017;7:71. 10.1186/s13613-017-0293-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dzeng E, Curtis JR. Understanding ethical climate, moral distress, and burnout: a novel tool and a conceptual framework. BMJ Qual Saf 2018;27:766–70. 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-007905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Royal College of Anaesthetists . A report on the welfare, morale and experiences of anaesthetists in training: the need to listen. 2017.

- 13.Dodek PM, Cheung EO, Burns KE, et al. Moral distress and other wellness measures in canadian critical care physicians. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2020;24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elpern EH, Covert B, Kleinpell R. Moral distress of staff nurses in a medical intensive care unit. American Journal of Critical Care 2005;14:523–30. 10.4037/ajcc2005.14.6.523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jameton A. Nursing practice: the ethical issues. New Jersey: Prentice Hall Inc, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamric AB. Empirical research on moral distress: issues, challenges, and opportunities. HEC Forum 2012;24:39–49. 10.1007/s10730-012-9177-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morley G, Ives J, Bradbury-Jones C, et al. What is “moral distress”? A narrative synthesis of the literature. Nurs Ethics 2019;26:646–62. 10.1177/0969733017724354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choe K, Kang Y, Park Y. Moral distress in critical care nurses: a phenomenological study. J Adv Nurs 2015;71:1684–93. 10.1111/jan.12638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morley G, Bradbury-Jones C, Ives J. What is "moral distress'' in nursing? A feminist empirical bioethics study. Nurs Ethics 2020;27:1297–314. 10.1177/0969733019874492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dodek PM, Wong H, Norena M, et al. Moral distress in intensive care unit professionals is associated with profession, age, and years of experience. Journal of Critical Care 2016;31:178–82. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine, Intensive Care Society . Guidelines for the provision of intensive care services. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sprung CL, Cohen SL, Sjokvist P, et al. End-Of-Life practices in European intensive care units: the ethicus study. JAMA 2003;290:790–7. 10.1001/jama.290.6.790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corley MC. Moral distress of critical care nurses. american journal of critical care: an official publication. American Association of Critical-Care Nurses 1995;4:280–5. 10.4037/ajcc1995.4.4.280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodney P. Moral distress in critical care nursing. Can Crit Care Nurs J 1988;5:9–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamric AB, Borchers CT, Epstein EG. Development and testing of an instrument to measure moral distress in healthcare professionals. AJOB Primary Research 2012;3:1–9. 10.1080/21507716.2011.65233726137345 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henrich NJ, Dodek PM, Alden L, et al. Causes of moral distress in the intensive care unit: a qualitative study. J Crit Care 2016;35:57–62.:. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwenzer KJ, Wang L. Assessing moral distress in respiratory care practitioners. Crit Care Med 2006;34:2967–73. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000248879.19054.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monrouxe LV, Rees CE, Dennis I, et al. Professionalism dilemmas, moral distress and the healthcare student: insights from two online UK-wide questionnaire studies. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007518. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quek CWN, Ong RRS, Wong RSM, et al. Systematic scoping review on moral distress among physicians. BMJ Open 2022;12:e064029. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-064029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pathman DE, Sonis J, Rauner TE, et al. Moral distress among clinicians working in US safety net practices during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed methods study. BMJ Open 2022;12:e061369. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-061369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colville GA, Dawson D, Rabinthiran S, et al. A survey of moral distress in staff working in intensive care in the UK. J Intensive Care Soc 2019;20:196–203. 10.1177/1751143718787753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.St Ledger U, Begley A, Reid J, et al. Moral distress in end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. J Adv Nurs 2013;69:1869–80. 10.1111/jan.12053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Böhm K, Schmid A, Götze R, et al. Five types of oecd healthcare systems: empirical results of a deductive classification. Health Policy 2013;113:258–69. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wallace DJ, Angus DC, Seymour CW, et al. Critical care bed growth in the United States. A comparison of regional and national trends. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191:410–6. 10.1164/rccm.201409-1746OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong DJN, Popham S, Wilson AM, et al. Postoperative critical care and high-acuity care provision in the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand. Br J Anaesth 2019;122:460–9. 10.1016/j.bja.2018.12.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Epstein EG, Whitehead PB, Prompahakul C, et al. Enhancing understanding of moral distress: the measure of moral distress for health care professionals. AJOB Empir Bioeth 2019;10:113–24. 10.1080/23294515.2019.1586008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whitehead PB, Herbertson RK, Hamric AB, et al. Moral distress among healthcare professionals: report of an institution-wide survey. J Nurs Scholarsh 2015;47:117–25. 10.1111/jnu.12115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oh Y, Gastmans C. Moral distress experienced by nurses: A quantitative literature review. Nurs Ethics 2015;22:15–31. 10.1177/0969733013502803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morley G, Ives J, Bradbury-Jones C, et al. What is'‘oral distress'’ A narrative synthesis of the literature. Nurs Ethics 2019;26:646–62. 10.1177/0969733017724354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tigard DW. Rethinking moral distress: conceptual demands for a troubling phenomenon affecting health care professionals. Med Health Care Philos 2018;21:479–88. 10.1007/s11019-017-9819-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hamric AB, Epstein EG. A health system-wide moral distress consultation service: development and evaluation. HEC Forum 2017;29:127–43. 10.1007/s10730-016-9315-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suntharalingam G, Handy J, Walsh A. Regionalisation of critical care: can we sustain an intensive care unit in every hospital? Anaesthesia 2014;69:1069–73. 10.1111/anae.12810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jameton A. Dilemmas of moral distress: moral responsibility and nursing practice. AWHONNS Clin Issues Perinat Womens Health Nurs 1993;4:542–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-068918supp001.pdf (259.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-068918supp002.pdf (52.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-068918supp003.pdf (132.8KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.