Abstract

Patients with familial Mediterranean fever and spondylitis often fail to respond to conventional and biologic therapies. Achieving remission in these patients usually requires conventional and biologic treatment combinations. Combination of biologic agents may be a promising option for patients with familial Mediterranean fever and spondylitis who have refractory disease. Until recently, limited evidence existed regarding the efficacy and safety of this treatment strategy. To address this, our report presented a case series of 4 patients with familial Mediterranean fever and spondylitis who were resistant to standard treatments and in whom remission is achieved only with dual biologic therapy. The authors also conducted a literature search for studies that reported dual biological therapy in inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: Dual biologic therapy, FMF, spondylitis, treatment

Introduction

Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) is an autoinflammatory disease characterized by recurrent febrile attacks of serositis. Sacroiliitis, which is the hallmark of spondyloarthropathies, is reported to arise at a higher than expected frequency in both Turkish and Jewish FMF patients with musculoskeletal symptoms1 The concomitant spondylitis to FMF may put clinicians in a difficulty with treatment because of their different pathological pathways. Although anakinra is suggested to be effective in FMF patients with sacroiliitis, this strategy is usually ineffective in other patients due to possible differences in the pathogenesis of FMF-associated conditions.2,3 Biologic therapy is being increasingly utilized for patients with spondyloarthritis. The accelerated use is also accompanied by a growing number of patients who have primary nonresponse or loss of response. Drug-related adverse effects and varying treatment efficacies for extraarticular manifestations are further obstacles to effective management.

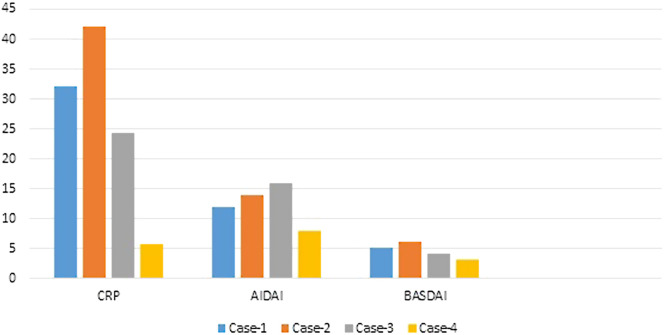

For this reason, we present 4 patients with FMF and spondyloarthritis who were treated with a combination of 2 biologic agents and followed in our tertiary referral center for effectiveness and adverse reactions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Initial C-reactive protein levels and clinical activity scores of four patients.

Case Presentation

Case 1. Our patient is a 43-year-old woman with a longstanding history of severe FMF since age 20. Her history includes numerous peritonitis and pleuritis attacks with high fever. She was also diagnosed with sacroiliitis 13 years ago. HLA-B 27 was negative, and magnetic resonance imaging findings showed bone marrow edema in both sacroiliac joints. Nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) were added to treatment. But FMF attacks had become frequent in the 15th year of disease and were refractory to 3 g/day colchicine. Anakinra, a recombinant inhibitor of the interleukin (IL)-1 receptor, has been added to treatment. The dose of colchicine was reduced to 2 g/day because of elevated liver function tests and intolerable gastrointestinal side effects.

Early in her treatment course, the patient was treated successfully with NSAIDs for sacroiliitis, but the disease flared after a year. The patient’s back pain and spinal sensitivity partially improved, while her FMF attacks cleared with anakinra 200 mg/day. Dual biologic therapy was initiated with certolizumab pegol, 200 mg every 2 weeks, and anakinra, 200 mg/day. Remission was maintained for more than a year, and because of new-onset psoriatic changes that appeared in the skin, certolizumab was eventually discontinued. Etanercept was planned, but anaphylaxis occurred after a single dose. Despite increasing dose of NSAIDs and sulphasalazine, her symptoms worsened. Secukinumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits IL-17A, was eventually added to her treatment. Remission is achieved so far with tolerable symptoms and normal C-reactive protein (CRP) levels. The patient revealed no infectious or adverse events (AEs).

Case 2. A 32-year-old male patient was diagnosed with FMF at the age of 3. Pleuritis and fever were predominant, and he suffered from these attacks twice a month. Because of colchicine resistance, anakinra 100 mg/day was added to treatment. Frequent attacks and increasing proteinuria were managed only with 300 mg/day dose of anakinra, but the patient has allergic local reactions to high doses. Anakinra 200 mg/day and colchicine 2 g/day treatment could only be tolerated, but clinical remission was not achieved. AA amyloidosis was proven with renal biopsy in 2015. He was diagnosed with sacroiliitis in 2015 with symptoms, laboratory, and radiologic findings. He was then put on numerous medications such as NSAIDs, colchicine, and anakinra, but patients’ symptoms gradually progressed. His 24-hour proteinuria was 6 g/day, and he had attacks twice on a month and complained of severe back pain with elevated acute phase response. Interferon (IFN) alpha 2B was planned and administrated for 6 months. During this trial-and-error phase, IFN was changed to infliximab because of inefficacy, but no clinical response is observed in 6 months. Canakinumab, IgG1 human monoclonal antibody targeting IL‐1β, is added to treatment because of accelerated FMF attacks. Proteinuria was increased to 11 g/day, and he was diagnosed with glomerulonephritis with hypertension, hyperlipidemia and was also followed by nephrology department. Clinical response was obtained with first 6 months of canakinumab treatment, but secondary loss of response occurred. Tofacitinib, janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, is added but no remission is achieved after 3 years. Patient also showed increased signs of proteinuria and Amyloid A (AA) amyloidosis. Tocilizumab, a monoclonal antibody against the IL-6 receptor, was added to treatment because of refractory amyloidosis. He is still been followed with complete clinical remission and significant improvement of laboratory values with normal CRP levels and 1-1.5 g/day proteinuria.

Case 3. Patient is a 47-year-old man with FMF diagnosed at the age of 19. He has numerous arthritis and pleuritis attacks with high fever. He had complained of inflammatory back pain and was diagnosed with sacroiliitis at the age of 33. Firstly, indomethacin and sulphasalazine are prescribed, but he was nonresponsive to different NSAID drugs. Etanercept is added, but secondary loss of response is observed in the third year of treatment. Proteinuria was slightly increased to 400 mg/day over the months. Salivary gland biopsy showed AA amyloidosis. But FMF attacks had become frequent and refractory to maximum dose of colchicine. Anakinra was added to treatment.

Early in his treatment course, FMF attacks of the patient had partial remission with anakinra 200 mg/day, but symptoms of sacroiliitis worsened. After a while, FMF attacks also occurred twice a month, bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index (BASDAI) scores of patient was higher, and he has inability to work and perform routine activities. Proteinuria was increasing and acute phase reactants remained in elevated course. Because of that biologic treatment was changed to certolizumab pegol, 200 mg every 2 weeks, and canakinumab, 150 mg/month. After 1 year remission, canakinumab has stopped because of patient’s reluctance to use canakinumab and treatment is regulated as certolizumab plus colchicine. Anakinra was only administered in prodromal phase of FMF attack. He is now in remission and being followed in our rheumatology clinic with proteinuria about 150-200 mg/day and lower BASDAI scores for 5 years with the same treatment.

Case 4. A 27-year-old patient was diagnosed with FMF at the age of 12 with recurrent arthritis, fever and peritonitis attacks, and E148Q single mutation. Lack of strong gene positivity confused physicians in previous clinics and led to inappropriate treatments. He has changed multiple medications with different diagnoses like still disease, juvenile idiopathic arthritis. After 4 year break in follow-up, he was admitted to our hospital with 3000 mg/day proteinuria, 2 times per month attacks, and elevated acute phase proteins. Kidney biopsy showed AA amyloidosis with amorphous bright pink deposits in the mesangium and capillary wall and mesangial expansion. He had peritonitis, fever, and arthritis attacks with pretibial edema on bilateral lower legs. Anakinra 100 mg and colchicine 2 g/day were prescribed, and partial remission is obtained with reduced number of attacks and normal acute phase protein levels. After 4 years, patient was diagnosed with sacroiliitis with clinical signs and positive radiologic findings (grade 3 sacroiliitis on both sacroiliac joints). Sulphasalazine was added to treatment. The frequency of attacks and proteinuria were increased after 4 months of anakinra and the dose has increased to 200 mg per day. Tocilizumab 162 mg/week was added to anakinra for resistant symptoms of AA amyloidosis. He had remission with 200-250 mg/day proteinuria, once-a-year FMF attack, and normal acute phase proteins. He was followed with tocilizumab 162 mg/week and anakinra with complete response to treatment.

All included patients have given, explained, and signed informed consent forms.

Literature Search

We performed literature search of studies investigating the use of dual biologic treatment in patients with FMF and spondylitis. MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar were searched.

We included all papers (case reports, controlled trials, case-control, cross-sectional, or cohort studies) related to dual biological treatment. Exclusion criteria were manuscripts that are not accessible in publication in non-English languages.

Discussion

Considering the complexity of the inflammatory network, co-inhibition of effective inflammatory cytokines may provide a strong synergy in achieving clinical remission. The biologic activities of IL-1 are synergistic with other cytokines and growth factors; tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha and various growth factors relate mostly to cytokine production and prostanoid synthesis.4,5 This collaboration may be explained by the ability to induce synthesis of each other.

Loss of response often causes treatment difficulties and can lead to refractory disease. This may be even more difficult in long-term patients who have been exposed to multiple medications. Patients who have failed conventional treatment and one biologic drug might benefit from a strategy that blocks several pathways. Dual biologic therapy could be considered as an efficacious and well-tolerated option for patients with limited treatment options with severe complicated or refractory disease.

Physicians are usually unwilling to prescribe 2 biological drugs because of disconcerting serious AEs. Very little data exist regarding dual biologic medications for Crohn’s disease, psoriatic arthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis (RA).6-8 Additionally, the possibility of a major adverse cardiovascular event related to combined biologic therapy has been reported.9 Some previous reports suggest a higher rate of infectious complications in patients receiving dual biologic therapy.10,11 Abatacept combination with etanercept in patients with active RA documented higher frequencies of AEs and drug discontinuation was reported due to these events in 1-year double-blind randomized trial.12 Also, etanercept plus anakinra treatment suggested higher number of serious AEs and a higher number of injection site reactions.13 Using a combination of CD4 monoclonal antibody with a bivalent TNF antagonist documented no increased risk for infections, but serious infusion site reactions were reported.14 Two case series showed the efficacy of rituximab (RTX) addition to etanercept, with only a single described infectious event.15

Patients reported in this paper had no infections or any other serious AEs compatible with some previous reports.10,16 Ahmed et al17 performed a metaanalysis which identified 39 reports of 30 studies that included 279 patients on dual biologic or small molecule therapies. This pooled data demonstrated a similar risk for injections between DBT and biologic drug monotherapy. Two reports of patients with Crohn’s diseases showed similar results.18,19 Also, in a retrospective analysis of RTX plus etanercept, significant clinical improvement and safety about serious AEs were noted. Only one herpes simplex infection was reported on combination therapy.20 SUNDIAL II trial was designed as biological therapy plus RTX in patients with active RA and unable to reach clinical improvement. Approximately 85% of the patients were receiving an anti-TNF agent with 52.8% receiving a DMARD such as methotrexate (MTX) or leflunomide. Serious AE rate was reported as 24.3 per 100 patient-years (6 reported events with adalimumab, 4 with etanercept alone, and 4 with infliximab and MTX).21,22 TAME study was also evaluated with anti-TNF plus RTX treatment, and the number of infections was higher in the placebo group than in the combination group23 ASSURE trial reported abatacept plus anakinra treatment in selective patients with refractory systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. All experienced marked clinical improvement and were able to reduce the dose of anakinra and steroids. During follow-up, no infusion reactions and significant infections were noted.24 Treatment in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) aims disease remission, damage prevention, and improved health-related quality of life. Conventional treatments for SLE, such as corticosteroids and immunosuppressants, have long-term toxicity and inadequent efficacy for achieving remission in most of the patients.25 Rituximab may cause advanced BLyS production, and RTX treatment may contribute to survival of autoreactive B cells. Only interaction may lead to increased disease flares26 Combining belimumab with RTX therefore may be logic, as the drugs operate through complementary mechanisms. Combination treatment with Rituximab and belimumab provide an immunologic response by effectively reducing antinuclear antibody levels (ANA) and excessive neutrophil excessive extracellular traps formation in patients with SLE.27,28 Double-blind, placebo-controlled study, named as BEAT-LUPUS phase 2 and BLISS-BELIEVE phase 3 trials, randomized patients to 3 arms as belimumab and placebo, only belimumab, and belimumab plus RTX treatment groups.24,29 Inflammatory bowel disease patients who have failed conventional medication and have a high risk for bowel surgery are usually exposed to biological therapy. Ribaldone et al30 included 7 studies with a total of 18 patients. Fifteen patients were treated with a combination of an anti-TNF and vedolizumab, 3 patients were treated with vedolizumab and ustekinumab. A clinical improvement was obtained in 100% of patients, and an endoscopic improvement was obtained in 93% of patients. No serious AEs were reported.

Drug-related AEs and varying treatment efficacies for diseases are further obstacles to effective management. Medically refractory disease leads to increased mortality. In addition to consideration of outcomes, economic cost will likely play an increasing role in the real-world application of this therapeutic strategy. Although dual biological agents are more expensive than conventional treatment options, increased quality of life, prevention of workday loss, and decreased hospitality may provide more economic utility.30, 31 Only a small number of patients were treated with a dual biological therapy: this is the major limitation of our presentation. Future research should also examine the potential role of bispecific monoclonal antibodies in the treatment of FMF and spondylitis. All treatment changes, durations, effects, and side effects are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demonstration of combination, duration, and responses of treatment for patients

| Case number | Combination of Drugs | Length of Treatment | Outcome |

| 1 | Colchicine + NSAID | 2 years | Ineffectivity |

| Colchicine + NSAID + anakinra | 1 year | Flare of sacroiliitis | |

| Certolizumab + anakinra + colchicine | 1 year | Psoriatic skin lesions related to anti-TNF drug | |

| Etanercept + anakinra + colchicine | 1 week | First dose anaphylaxis related to etanercept | |

| Secukinumab + anakinra + colchicine | 5 years | No adverse effects and complete remission | |

| 2 | Colchicine + anakinra | 2 years | Resistant amyloidosis and ineffectivity to sacroiliitis |

| Colchicine + NSAID + anakinra | 5 months | Progression of both diseases | |

| Interferon alpha 2B [IFN] + colchicine + NSAID | 6 months | Ineffectivity | |

| Infliximab + colchicine + NSAID | 6 months | Progression of both diseases | |

| Canakimumab + colchicine + NSAID | 6 months | Secondary loss of response and progression of amyloidosis | |

| Canakimumab + tofacitinib + colchicine + NSAID | 3 years | Secondary loss of response | |

| Tocilizumab + canakimumab + NSAID + colchicine | 6 years | Complete remission | |

| 3 | Colchicine + NSAID | 1 year | Ineffectivity |

| Colchicine + NSAID + sulphasalazine | 1 year | Ineffectivity | |

| Etanercept + colchicine + NSAID | 3 years | Secondary loss of response and progression of amyloidosis | |

| Anakinra + etanercept + colchicine + NSAID | 2 years | Secondary loss of response and progression of amyloidosis | |

| Canakimumab + certolizumab + colchicine | 1 year | Patient’s rejection of treatment | |

| Certolizumab + colchicine + on-demand anakinra | 5 years | Complete remission | |

| 4 | Anakinra + colchicine | 4 years | Secondary loss of response |

| Anakinra + colchicine + sulphasalazine | 1 year | Progression of amyloidosis | |

| Anakinra + colchicine + sulphasalazine + tocilizumab | 6 years | Complete remission |

IFN, interferon; NSAID, Nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drug; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Footnotes

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all included patients.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - R.C.K.; Design - R.C.K.; Supervision - İ.V., A.T.; Fundings - B.Ö., İ.V.; Materials - B.Ö.; Data Collection and/or Processing - D.Y.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - D.Y.; Literature Review - H.K., A.T.; Writing - D.Y., H.K., M.A.Ö.; Critical Review - M.A.Ö., A.T.

Declaration of Interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1. Atas N, Armagan B, Bodakci E.et al. Familial Mediterranean fever is associated with a wide spectrum of inflammatory disorders: results from a large cohort study. Rheumatol Int. 2020;40(1):41 48. 10.1007/s00296-019-04412-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Varan O, Kucuk H, Tufan A. Anakinra for the treatment of familial Mediterranean fever associated spondyloarthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2016;45(3):252 253. 10.3109/03009742.2015.1127413) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yazici A, Ozdemir Isik O, Temiz Karadag D, Cefle A. Are there any clinical differences between ankylosing spondylitis patients and familial Mediterranean fever patients with ankylosing spondylitis? Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(1):e13645. 10.1111/ijcp.13645) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Papamichael K, Vogelzang EH, Lambert J, Wolbink G, Cheifetz AS. Therapeutic drug monitoring with biologic agents in immune mediated inflammatory diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2019;15(8):837 848. 10.1080/1744666X.2019.1630273) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nisticò S, Paolillo N, Minella D.et al. Effects of TNF-α and IL-1 β on the activation of genes related to inflammatory, immune responses and cell death in immortalized human HaCat keratinocytes. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2010;23(4):1057 1072. 10.1177/039463201002300410) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Howard G, Weiner D, Bar-Or I, Levine A. Dual biologic therapy with vedolizumab and ustekinumab for refractory Crohn’s disease in children. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;34(4):372 374. 10.1097/MEG.0000000000002203) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cuchacovich R, Garcia-Valladares I, Espinoza LR. Combination biologic treatment of refractory psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(1):187 193. 10.3899/jrheum.110295) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heinecke GM, Luber AJ, Levitt JO, Lebwohl MG. Combination use of ustekinumab with other systemic therapies: a retrospective study in a tertiary referral center. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12(10):1098 1102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Babalola O, Lakdawala N, Strober BE. Combined biologic therapy for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a case report. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1(1):3 4. 10.1016/j.jdcr.2014.09.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gniadecki R, Bang B, Sand C. Combination of antitumour necrosis factor-alpha and antiinterleukin-12/23 antibodies in refractory psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a long-term case series observational study. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174(5):1145 1146. 10.1111/bjd.14270) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Torre KM, Payette MJ. Combination biologic therapy for the treatment of severe palmoplantar pustulosis. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3(3):240 242. 10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.03.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weinblatt M, Schiff M, Goldman A.et al. Selective costimulation modulation using abatacept in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis while receiving etanercept: a randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(2):228 234. 10.1136/ard.2006.055111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Genovese MC, Cohen S, Moreland L.et al. Combination therapy with etanercept and anakinra in the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis who have been treated unsuccessfully with methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(5):1412 1419. 10.1002/art.20221) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Morgan AW, Hale G, Rebello PR.et al. A pilot study of combination anti-cytokine and anti-lymphocyte biological therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Qjm. 2008;101(4):299 306. 10.1093/qjmed/hcn006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Feuchtenberger M, Kneitz C, Roll P, Kleinert S, Tony HP. Sustained remission after combination therapy with rituximab and etanercept in two patients with rheumatoid arthritis after TNF failure: case report. Open Rheumatol J. 2009;3:9 13. 10.2174/1874312900903010009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Olbjørn C, Rove JB, Jahnsen J. Combination of biological agents in moderate to severe pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: A case series and review of the literature. Paediatr Drugs. 2020;22(4):409 416. 10.1007/s40272-020-00396-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ahmed W, Galati J, Kumar A.et al. Dual biologic or small molecule therapy for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021:S1542 S356500344-X. 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.03.034) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sands BE, Kozarek R, Spainhour J.et al. Safety and tolerability of concurrent natalizumab treatment for patients with Crohn’s disease not in remission while receiving infliximab. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13(1):2 11. 10.1002/ibd.20014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD.et al. Infliximab for Crohn’s disease: more than 13 years of real-world experience. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(3):490 501. 10.1093/ibd/izx072) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blank N, Max R, Schiller M, Briem S, Lorenz HM. Safety of combination therapy with rituximab and etanercept for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol (Oxf Engl). 2009;48(4):440 441. 10.1093/rheumatology/ken491) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cohen SB, Emery P, Greenwald MW.et al. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating primary efficacy and safety at twenty-four weeks. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(9):2793 2806. 10.1002/art.22025) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rigby WF, Mease PJ, Olech E, Ashby M, Tole S. Safety of rituximab in combination with other biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis: an open-label study. J Rheumatol. 2013;40(5):599 604. 10.3899/jrheum.120924) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Greenwald MW, Shergy WJ, Kaine JL, Sweetser MT, Gilder K, Linnik MD. Evaluation of the safety of rituximab in combination with a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor and methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results from a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(3):622 632. 10.1002/art.30194) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Teng YKO, Bruce IN, Diamond B.et al. Phase III, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 104-week study of subcutaneous Belimumab administered in combination with rituximab in adults with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): BLISS-BELIEVE study protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):e025687. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025687) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Record JL, Beukelman T, Cron RQ. Combination therapy of abatacept and anakinra in children with refractory systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a retrospective case series. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(1):180 181. 10.3899/jrheum.100726) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Oglesby A, Shaul AJ, Pokora T.et al. Adverse event burden, resource use, and costs associated with immunosuppressant medications for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic literature review. Int J Rheumatol. 2013;2013:347520. 10.1155/2013/347520) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ehrenstein MR, Wing C. The BAFFling effects of rituximab in lupus: danger ahead? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(6):367 372. 10.1038/nrrheum.2016.18) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kraaij T, Kamerling SWA, de Rooij ENM.et al. The NET-effect of combining rituximab with Belimumab in severe systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2018;91:45 54. 10.1016/j.jaut.2018.03.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jones A, Muller P, Dore CJ.et al. Belimumab after B cell depletion therapy in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (BEAT lupus) protocol: a prospective multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, 52-week phase II clinical trial. BMJ Open. 2019;9(12):e032569. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032569) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ribaldone DG, Pellicano R, Vernero M.et al. Dual biological therapy with anti-TNF, vedolizumab or ustekinumab in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review with pool analysis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(4):407 413. 10.1080/00365521.2019.1597159) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Høivik ML, Moum B, Solberg IC.et al. Work disability in inflammatory bowel disease patients 10 years after disease onset: results from the IBSEN study. Gut. 2013;62(3):368 375. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302311) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Content of this journal is licensed under a

Content of this journal is licensed under a