Abstract

Coxiella burnetii, the agent of Q fever, enters human monocytes through αvβ3 integrin and survives inside host cells. In addition, C. burnetii stimulates the synthesis of inflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) by monocytes. We studied the role of the interaction of C. burnetii with THP-1 monocytes in TNF production. TNF transcripts and TNF release reached maximum values within 4 h. Almost all monocytes bound C. burnetii after 4 h, while the percentage of phagocytosing monocytes did not exceed 20%. Cytochalasin D, which prevented the uptake of C. burnetii without interfering with its binding, did not affect the expression of TNF mRNA. Thus, bacterial adherence, but not phagocytosis, is necessary for TNF production by monocytes. The monocyte αvβ3 integrin was involved in TNF synthesis since peptides containing RGD sequences and blocking antibodies against αvβ3 integrin inhibited TNF transcripts induced by C. burnetii. Nevertheless, the cross-linking of αvβ3 integrin by specific antibodies was not sufficient to induce TNF synthesis. The signal delivered by C. burnetii was triggered by bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Polymyxin B inhibited the TNF production stimulated by C. burnetii, and soluble LPS isolated from C. burnetii largely mimicked viable bacteria. On the other hand, avirulent variants of C. burnetii induced TNF production through an increased binding to monocytes rather than through the potency of their LPS. We suggest that the adherence of C. burnetii to monocytes via αvβ3 integrin enables surface LPS to stimulate TNF production in THP-1 monocytes.

Coxiella burnetii is the etiologic agent of Q fever, a zoonosis of worldwide distribution. The disease has an acute form and a chronic form, usually expressed as an endocarditis (23). While acute Q fever is characterized by efficient cell-mediated immunity, its chronic form is associated with impairment of protective T-cell responses (20, 21). In addition, large amounts of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) are found in plasma and monocyte supernatants from patients with Q fever endocarditis (5, 6). Such TNF overproduction is involved in the survival of C. burnetii inside patient monocytes (12).

TNF contributes to the protective host response (2), and different intracellular bacteria (3, 8, 9, 22) have developed specific strategies to prevent the production of TNF by macrophages. In contrast, C. burnetii stimulates TNF production in human and murine macrophages (12, 32). It is largely unknown whether virulence-associated features of C. burnetii account for the ability of the organism to elicit cytokine production in macrophages. Virulent C. burnetii organisms are poorly internalized but successfully survive in monocytes, in contrast to avirulent variants (7). The uptake of avirulent C. burnetii is mediated by αvβ3 integrin and CR3, whereas virulent organisms engage αvβ3 integrin but impair CR3 activity (7). The relationship between the internalization of microorganisms and cytokine synthesis by target cells is open to debate. Some reports demonstrated that bacterial adherence to host cells is sufficient to trigger cytokine production. The adhesion of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium to epithelial cells stimulates interleukin-8 (IL-8) release (24). The binding of Legionella pneumophila to murine macrophages elicited the expression of several transcripts for inflammatory cytokines including TNF (35). In contrast, other reports show that cytokines are produced only after bacterial internalization. The uptake of Staphylococcus aureus by endothelial cells is necessary for the transcription of IL-1β and IL-6 genes (36). IL-8 is secreted by epithelial cells in response to invasion by Salmonella spp. or Listeria monocytogenes (13).

The virulence of C. burnetii is mainly related to the structure of its lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Upon serial passages in culture, C. burnetii undergoes an irreversible transition from a virulent to an avirulent form, which is accompanied by dramatic changes in both LPS composition and structure. Hence, phase I bacteria express a smooth-type LPS (S-LPS) (1, 29) and are virulent, whereas phase II variants exhibit a rough-type LPS (R-LPS) (30) and are avirulent (16). The S-LPS is one of the major outer-membrane components of C. burnetii. It plays a role in bacterial immunogenicity and induces a strong antibody response (14). Although LPS is a powerful inducer of inflammatory cytokine production (18), S-LPS from C. burnetii was considered to be poorly endotoxic (33). However, its ability to induce secretion of inflammatory cytokines in murine macrophages has recently been reported (32; E. Gajdosova, M. Kubes, V. Mucha, L. Skultety, and R. Toman, Abstr. 26th Meet. Fed. Eur. Biochem. Soc., abstr. 464, p. s397, 1999).

In this report, we show that C. burnetii adherence to THP-1 monocytes via αvβ3 integrin was necessary to trigger TNF production but that the engagement of αvβ3 integrin was not sufficient to elicit such a response. An additional signal was provided by C. burnetii LPS. Hence, polymyxin B inhibited the TNF synthesis stimulated by organisms and LPS isolated from C. burnetii mimicked viable bacteria. We suggest that the binding of organisms to αvβ3 integrin enables C. burnetii LPS to activate TNF production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and bacteria.

The human myelomonocytic cell line THP-1 was cultured as previously described (11). All culture media were checked for absence of endotoxins by using Limulus amebocyte lysate (Boehringer Ingelheim, Gagny, France). C. burnetii organisms in phase I (Nine Mile strain) were injected into mice as described previously (25). Spleen cells were then added to mouse L929 fibroblasts in antibiotic-free Eagle minimal essential medium supplemented with 4% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco-BRL, Life Technologies, Eragny, France) for two passages. Phase II organisms were cultured by repeated passages of Nine Mile strain. After sonication of infected L929 cells, bacteria in phase I or in phase II were layered on a 25 to 45% linear Renograffin gradient. Purified bacteria were suspended in Hanks balanced salt solution before being stored at −80°C. The concentration of C. burnetii was determined by Gimenez staining.

Determination of C. burnetii-monocyte interaction.

THP-1 cells (3 × 104 cells) were incubated with C. burnetii at different bacterium-to-cell ratios for different periods of time. They were then fixed with 1% formaldehyde and permeabilized by 0.1 mg of lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC; Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, Mo.) or not permeabilized. Bacteria were revealed by indirect immunofluorescence using specific rabbit antibodies (Ab) and a fluorescein-conjugated secondary Ab as described previously (7). Without LPC, only monocyte-bound bacteria were detected, while bound and ingested bacteria were revealed in the presence of LPC. The association index was quantified as follows: (number of bacteria per positive cell) × (percentage of positive cells) × 100. The difference between indexes with and without LPC was a measure of the uptake of C. burnetii (phagocytosis index).

Determination of TNF production.

THP-1 cells (106 cells in a 1-ml volume in flat-bottom 24-well culture plates; Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were incubated with various concentrations of C. burnetii or LPS at 37°C in RPMI 1640 (Gibco-BRL) containing 25 mM HEPES, 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U of penicillin/ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin/ml. S-LPS and R-LPS from Nine Mile strain were isolated as described previously (29, 30) and stored at 1 mg/ml at −20°C. In some experiments, monocytes were pretreated with monoclonal Ab (MAb) directed against αvβ3 integrin (7G2, immunoglobulin G1 [IgG1]) (4), αMβ2 integrin (CD11b, IgG1; Immunotech, Marseille, France) or control IgG1, peptides containing RGD-related sequences (15), cytochalasin D, or polymyxin B (Sigma Chemicals).

Measurement of TNF transcripts.

Total RNA was extracted by Trizol reagent (Gibco-BRL). Reverse transcription was performed using Superscript reverse transcriptase (Gibco-BRL), and cDNA specimens were tested for TNF by PCR. Primer pairs for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) and TNF (5) were purchased from Eurogentec (Brussels, Belgium). The mixtures containing Taq polymerase (Gibco-BRL) and specific primers were subjected to 24 (G3PDH) or 28 (TNF) cycles of denaturation, annealing at 55 (G3PDH) or 65°C (TNF), and extension at 72°C. PCR products were electrophoresed in 2% agarose gels containing ethidium bromide. The sizes of bands were determined with DNA molecular weight marker VI (Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France). Amplification products were quantified with CytoXpress detection kits (BioSource, Nivelles, Belgium) as previously described (12).

Measurement of TNF release.

Supernatants of stimulated monocytes were collected, centrifuged at 10,000 × g to discard bacteria, and stored at −80°C before cytokine determination. Immunoreactive TNF was quantified using an enzyme immunoassay kit (Immunotech) as recommended by the manufacturer. The minimum concentration of detected TNF was estimated to be 8 pg/ml. The TNF bioactivity was evaluated by crystal violet staining of murine L929 fibroblasts, as previously described (27). Monocyte supernatants were added to L929 cell monolayers in the presence of 1 μg of actinomycin D (Sigma Chemicals)/ml for 18 h at 37°C. Crystal violet at 0.5% was added to L929 cells for 10 min at 37°C and solubilized with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate. Human recombinant TNF and TNF-neutralizing Ab (R&D Systems, Abingdon, United Kingdom) were included in each assay as controls. Absorbance was measured at 492 nm, and results are expressed as units of TNF per milliliter where 1 U is defined as the amount of TNF required to produce 50% cytotoxicity.

RESULTS

TNF production depends on C. burnetii-monocyte binding.

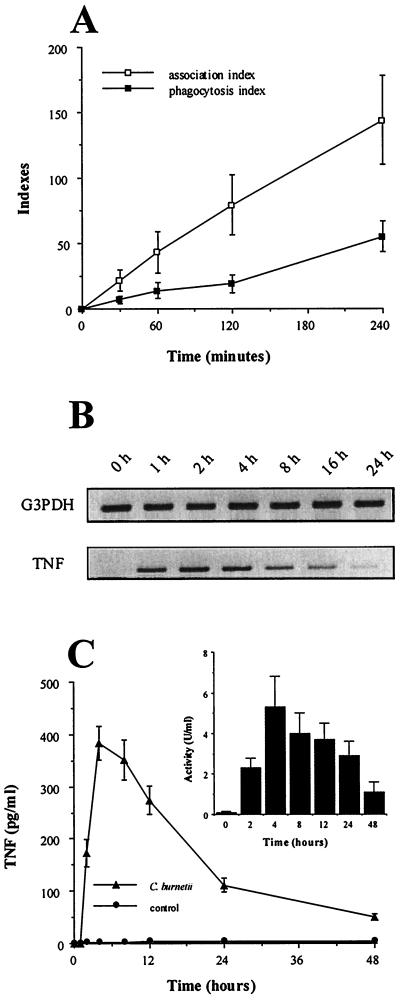

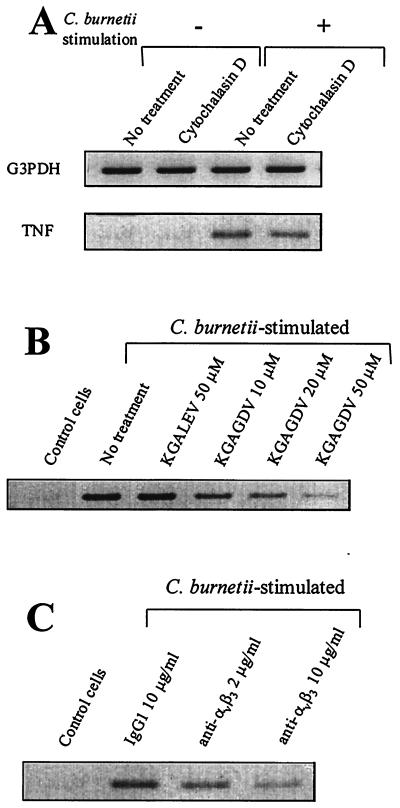

The time course of C. burnetii-monocyte interaction and TNF production was assessed. First, after 1 h of incubation with C. burnetii (bacterium-to-cell ratio of 100:1), 25% of THP-1 monocytes bound one or two bacteria but only 10% had phagocytosed one organism (Fig. 1A). After 2 to 4 h, monocytes with one or two bound bacteria represented 50 to 80% of cells, whereas the percentage of phagocytosing monocytes did not exceed 20%. Second, transcripts for TNF were detected 1 h after the addition of C. burnetii, peaked between 2 and 4 h, and steadily decreased thereafter (Fig. 1B). TNF release was detected in the supernatants of monocytes incubated with C. burnetii after 2 h using an immunoassay and bioassay (Fig. 1C). The TNF amounts then reached a peak between 4 and 8 h and steadily decreased down to a minimum value after 48 h. These results suggest that TNF synthesis precedes bacterial uptake. Therefore, THP-1 monocytes were pretreated with 1 μg of cytochalasin D/ml for 15 min and then were incubated with C. burnetii for 2 h. Cytochalasin D inhibited C. burnetii uptake but not bacterial attachment to monocytes (data not shown). It did not affect C. burnetii-stimulated expression of TNF transcripts (Fig. 2A; Table 1). Taken together, these results indicate that TNF production does not require uptake of C. burnetii by monocytes and that bacterial binding to target cells is sufficient.

FIG. 1.

C. burnetii-monocyte interaction and TNF production. (A) THP-1 monocytes were incubated with C. burnetii at a bacterium-to-cell ratio of 100:1 for different periods of time. Cells were then washed, cytocentrifuged, and permeabilized by LPC or not permeabilized. Bacteria were revealed by indirect immunofluorescence. The results are means ± standard errors (SE) of four different experiments. (B) Total RNA was extracted and transcribed in cDNA. After amplification, PCR products for TNF and G3PDH, used as an internal control, were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. The data are representative of four different experiments. (C) Monocyte supernatants were assayed for the presence of TNF by immunoassay. Results are means ± SE of five experiments. (Inset) The same supernatants were assayed for TNF bioactivity. Results are means ± SE.

FIG. 2.

Effect of C. burnetii binding on TNF synthesis. Monocytes were pretreated with 1 μg of cytochalasin D/ml (A), KGALEV or KGAGDV peptides (B), or blocking anti-αvβ3 integrin MAb or control IgG1 (C) for 15 min and then stimulated with C. burnetii for 2 h. Total RNA was extracted and transcribed in cDNA. PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. The figure is representative of three different experiments.

TABLE 1.

Quantitative determination of TNF mRNAa

| Stimulation with C. burnetii | Pretreatment | No. of TNF copies |

|---|---|---|

| − | None | 105 ± 50 |

| + | None | 2,179 ± 171 |

| + | Cytochalasin D, 1 μg/ml | 1,940 ± 254 |

| + | Polymyxin B, 10 μg/ml | 450 ± 92 |

| + | KGALEV, 50 μM | 2,440 ± 310 |

| + | KGAGDV, 10 μM | 1,596 ± 182 |

| + | KGAGDV, 50 μM | 790 ± 216 |

| + | 7G2, 2 μg/ml | 1,353 ± 150 |

| + | 7G2, 10 μg/ml | 755 ± 102 |

THP-1 monocytes were pretreated as shown or not pretreated and then stimulated with C. burnetii (+; bacterium-to-cell ratio of 100:1) for 2 h or not stimulated (−). RNA was extracted and incubated with a reverse transcriptase mixture. After incubation with specific primers, the cDNAs were amplified and the expression of TNF transcripts was quantified. Results are mean numbers of TNF copies per nanogram of RNA ± standard errors for three experiments.

αvβ3 integrin is involved in C. burnetii-stimulated production of TNF.

As C. burnetii organisms interact with monocytes through αvβ3 integrin (7), we wondered whether bacterial attachment to monocyte αvβ3 integrin is involved in TNF production. First, THP-1 monocytes were treated with two peptides containing RGD-related sequences for 15 min and then incubated with C. burnetii at a bacterium-to-cell ratio of 100:1 for 2 h. KGALEV, which is inactive on αvβ3 integrin, had no effect on the expression of TNF transcripts (Fig. 2B; Table 1). In contrast, KGAGDV, which specifically inhibits αvβ3 integrin, downmodulated TNF synthesis in a dose-dependent manner. KGAGDV was weakly efficient at 10 μM (28% ± 8% inhibition) and inhibited TNF transcripts at 50 μM (67% ± 10% inhibition) (Table 1). This peptide concentration inhibited C. burnetii-monocyte binding by 85% ± 7%. Second, monocytes were treated with 7G2 MAb directed against αvβ3 integrin for 15 min and stimulated with C. burnetii for 2 h. Control IgG1 did not modify the expression of TNF mRNA (Fig. 2C). 7G2 MAb at 2 μg/ml decreased TNF mRNA expression by 42% ± 6% and by 69% ± 5% at 10 μg/ml. The latter concentration depressed the binding of C. burnetii to monocytes by 75% ± 10%. Similar results were obtained with F(ab′)2 of 7G2 MAb (data not shown), demonstrating that the inhibition of TNF expression was not mediated by Fc receptors. These results indicate that αvβ3 integrin is involved in C. burnetii-stimulated production of TNF.

C. burnetii LPS is necessary for TNF production.

As the binding of C. burnetii to αvβ3 integrin leads to TNF synthesis, we wondered whether the ligation of αvβ3 integrin triggers TNF synthesis. To test this hypothesis, αvβ3 integrin was cross-linked by 7G2 MAb (at 10 μg/ml) for 2 h and the expression of TNF transcripts was then assessed. TNF transcripts were not expressed by THP-1 monocytes in these experimental conditions (data not shown). Thus, the engagement of αvβ3 integrin was not sufficient to stimulate TNF transcription.

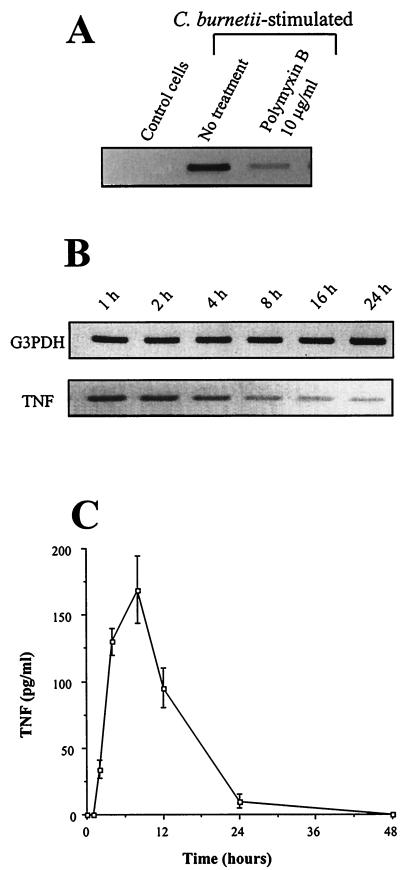

An additional trigger such as bacterial LPS is responsible for TNF synthesis. Monocytes were pretreated with polymyxin B, an antibiotic known to inhibit LPS activity, and stimulated by C. burnetii for 2 h (Fig. 3A). Polymyxin B at 10 μg/ml inhibited the expression of TNF transcripts (83% ± 4% inhibition) (Table 1). In addition, S-LPS isolated from C. burnetii stimulated TNF production. TNF transcripts were detected 1 to 2 h after the addition of S-LPS at 2 μg/ml, and their expression decreased thereafter (Fig. 3B). The time courses of TNF synthesis in response to C. burnetii and its LPS were similar (Fig. 1B and 3B). S-LPS also elicited TNF release, with a maximum value after 4 to 8 h of stimulation followed by a steady decrease down to 24 h (Fig. 3C). It is noteworthy that S-LPS was less potent than Escherichia coli LPS in stimulating TNF production. The expression of TNF mRNA in response to S-LPS was lower than the E. coli LPS-stimulated response (see Fig. 4C). In addition, the TNF release stimulated by S-LPS (Fig. 3C) was markedly decreased compared to that induced by E. coli LPS (about 1,400 ± 200 pg/ml) after 4 h of stimulation. Clearly, the kinetics of the TNF secretion induced by C. burnetii LPS was similar to that found with C. burnetii organisms.

FIG. 3.

TNF production induced by C. burnetii S-LPS. (A) Monocytes were incubated with or without polymyxin B (10 μg/ml) for 15 min and then stimulated by C. burnetii for 2 h. (B) Monocytes were incubated with 2 μg of C. burnetii S-LPS/ml for different periods of time. Total RNA was extracted and transcribed in cDNA. PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. The data are representative of three different experiments. (C) Monocytes were incubated with 2 μg of C. burnetii S-LPS/ml for different periods of time. Cell supernatants were then assayed for the presence of TNF using an enzyme immunoassay. Results are means ± standard errors representing the averages of three experiments.

FIG. 4.

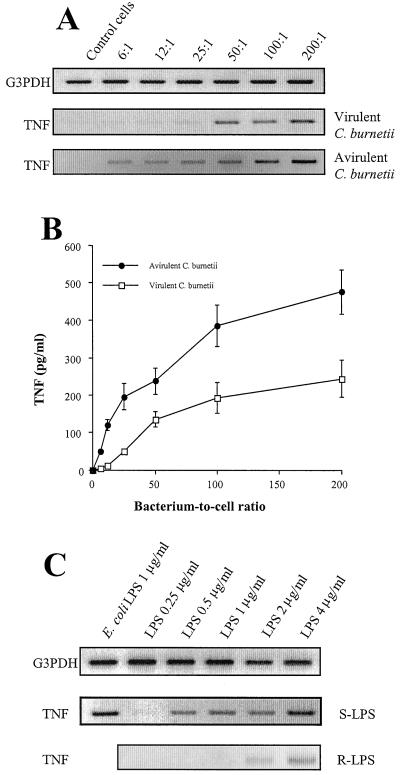

TNF production induced by avirulent C. burnetii and R-LPS. Monocytes were incubated with different concentrations of virulent or avirulent C. burnetii for 2 (A) or 8 h (B). (A) Total RNA was extracted and transcribed in cDNA. PCR products were analyzed as described for Fig. 1. The data are representative of three different experiments. (B) Monocyte supernatants were assayed for the presence of TNF by immunoassay. Results are means ± standard errors of four experiments. (C) Monocytes were incubated with different concentrations of S-LPS and R-LPS for 2 h. The expression of TNF mRNA was assessed as described for panel A. The data are representative of three different experiments.

Avirulent variants of C. burnetii and TNF production.

The attachment of avirulent variants of C. burnetii to monocytes is higher than that of virulent bacteria (7). Therefore, we wondered whether TNF production is related to the efficiency of the bacterium-monocyte interaction. Avirulent organisms were more potent than virulent bacteria at stimulating the expression of TNF mRNA (Fig. 4A). While TNF transcripts were detected in response to virulent C. burnetii at bacterium-to-cell ratios higher than 25:1, avirulent organisms elicited the expression of TNF transcripts with a bacterium-to-cell ratio as low as 6:1. Their expression became maximum at a bacterium-to-cell ratio of 50:1. Similarly, the release of TNF stimulated by avirulent C. burnetii was detected at a bacterium-to-cell ratio of 6:1, which was fivefold lower than that observed with virulent bacteria (Fig. 4B). The increased ability of avirulent C. burnetii organisms to stimulate the production of TNF may depend on their LPS. Polymyxin B inhibited the expression of TNF mRNA by 85%, a result reflecting the response to virulent organisms. However, LPS isolated from avirulent C. burnetii was less potent than S-LPS at inducing the expression of the TNF gene and TNF release (Fig. 4C). While 0.5 μg of S-LPS/ml induced TNF mRNA, R-LPS required fourfold-higher concentrations to stimulate TNF synthesis. R-LPS elicited TNF release with a time course similar to that of S-LPS, but the magnitude of the release remained lower (for R-LPS and S-LPS at 4 μg/ml, releases were 59 ± 5 and 250 ± 20 pg/ml, respectively, after 4 h). Thus, the ability of avirulent organisms to stimulate TNF production depends on the efficiency of their interaction with THP-1 monocytes rather than on the potency of their LPS.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show that C. burnetii-stimulated production of TNF by THP-1 monocytes requires the binding of bacteria to monocytes via αvβ3 integrin and bacterial LPS. The ability of C. burnetii to elicit TNF production deserves three comments. First, the TNF production was early and transient and it remained lower than that induced by other gram-negative bacteria (data not shown). This result is consistent with previous findings for murine macrophages (32) and human monocytes (12). Second, the TNF production was stimulated by different strains of C. burnetii such as the Priscilla strain obtained from an aborted goat fetus and human isolates (data not shown). Third, the ability of C. burnetii to induce the production of inflammatory cytokines was not restricted to TNF since IL-1β and chemokines such as IL-8 were found in supernatants from stimulated cells (data not shown), thus emphasizing results reported elsewhere (32).

TNF production results from bacterial adherence to host cells rather than from bacterial uptake. First, TNF transcripts were detected when C. burnetii organisms were bound to monocytes but still not internalized. In contrast, TNF synthesis started to decrease when C. burnetii phagocytosis increased, demonstrating that both events are uncoupled. It is noteworthy that the activation of NF-κB by L. monocytogenes also occurs in a biphasic mode: a transient phase mediated by the binding of bacteria to macrophages and a persistent phase induced when the bacteria enter the cytoplasm of host cells (17). Second, cytochalasin D did not affect the expression of TNF transcripts whereas it inhibited C. burnetii uptake without interfering with bacterial adherence to monocytes. This finding is reminiscent of the study by Yamamoto et al. (35) in which cytochalasin D had no effect on L. pneumophila-stimulated expression of TNF mRNA in macrophages. In addition, the early production of TNF by Salmonella species does not require bacterial internalization by monocytic cells (10).

As the interaction of virulent C. burnetii with monocytes depends on αvβ3 integrin (7), production of TNF should involve this integrin. Ab directed against αvβ3 integrin inhibited both C. burnetii association with monocytes and expression of TNF mRNA. However, the engagement of αvβ3 integrin was not sufficient to elicit TNF production since the cross-linking of αvβ3 integrin by specific MAb did not elicit TNF transcripts. Our results are consistent with previous reports. The ligation of β3 integrin by specific Ab does not trigger the production of inflammatory cytokines in monocytes (28), while the engagement of β1 integrins via fibronectin or other extracellular matrix proteins stimulates cytokine production (26). However, it was recently demonstrated that monocyte αvβ3 integrin is able to mediate TNF synthesis in response to soluble CD23 (19).

LPS triggered the production of TNF induced by C. burnetii. First, polymyxin B, known to impair LPS-dependent cell responses, abolished TNF synthesis, indicating that the S-LPS present at the surface of C. burnetii is responsible for the cytokine induction. Second, the purified S-LPS induced TNF production with a time course and a magnitude similar to those observed in response to viable C. burnetii. It is noteworthy that the magnitude of S-LPS-stimulated TNF production was fivefold lower than that of TNF production induced by LPS from enterobacteria such as E. coli. Differences in the compositions of both the lipid A moiety and O-specific chain between S-LPS and endotoxic LPS could account for the limited production of TNF (1).

TNF production did not directly reflect the virulence of C. burnetii since avirulent organisms induced TNF production. Avirulent bacteria were even more potent than virulent organisms at stimulating TNF production. This result is partly in agreement with the study by Tujulin et al. in which virulent and avirulent C. burnetii organisms induced TNF release in P388D1 macrophages to the same degree (32). The overproduction of TNF stimulated by avirulent C. burnetii may depend on R-LPS. Indeed, polymyxin B inhibited the TNF production induced by avirulent bacteria. However, soluble R-LPS did not mimic the production of TNF induced by avirulent organisms since it poorly induced TNF production. It is likely that differences (34) in the fatty acid compositions of the lipid A moieties of both the LPSs and the lack (30) of several sugars present in S-LPS (1, 29) contribute to the low potency of R-LPS. We hypothesize that the overproduction of TNF stimulated by avirulent C. burnetii is related to the increase in bacterial binding to monocytes since the interaction of avirulent variants with monocytes was dramatically more efficient than that of virulent organisms (7).

We suggest that C. burnetii-stimulated production of TNF involves a two-step mechanism. The interaction of C. burnetii with monocyte αvβ3 integrin is not sufficient to stimulate the production of TNF, but it enables the C. burnetii LPS to interact with monocytes and to trigger TNF production. Avirulent organisms, which efficiently bind to monocytes, would present more LPS molecules to target cells than do virulent bacteria, which poorly bind to monocytes. In this model, cell response to LPS requires the engagement of integrins. Such engagement has already been described for neutrophils since the interaction of free LPS is mediated by CD14, whereas the binding of erythrocytes coated with LPS is mediated by both CD14 and CR3, a β2 integrin (31). Hence, the way in which LPS is presented to THP-1 monocytes would determine TNF production.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank F. P. Lindberg for providing peptides containing RGD-related sequences and antibodies specific to αvβ3 integrin. We also thank G. Grau for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amano K L, Williams J C, Missler V, Reinhold N. Structure and biological relationship of C. burnetii lipopolysaccharides. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:4740–4747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bermudez L E, Kaplan G. Recombinant cytokines for controlling mycobacterial infections. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:22–27. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88864-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beuscher H V, Rodel F, Forsberg A, Rollinghoff M. Bacterial evasion of host immune defense: Yersinia enterocolitica encodes a suppressor for tumor necrosis factor alpha expression. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4804–4810. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1270-1277.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown E, Hooper L, Ho T, Gresham H. Integrin-associated protein: a 50 kD plasma membrane antigen physically and functionally associated with integrins. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:2785–2794. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Capo C, Zugun F, Stein A, Tardei G, Lepidi H, Raoult D, Mege J L. Upregulation of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1β in Q fever endocarditis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1638–1642. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1638-1642.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capo C, Amirayan N, Ghigo E, Raoult D, Mege J L. Circulating cytokine balance and activation markers of leucocytes in Q fever. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;115:120–123. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00786.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capo C, Lindberg F P, Meconi S, Zaffran Y, Tardei G, Brown E J, Raoult D, Mege J L. Subversion of monocyte functions by Coxiella burnetii: impairment of the cross-talk between αvβ3 integrin and CR3. J Immunol. 1999;163:6078–6085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caron E, Gross A, Liautard J P, Dornand J. Brucella species release a specific, protease-sensitive, inhibitor of TNF-α expression, active on human macrophage-like cells. J Immunol. 1996;156:2885–2893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatterjee D, Roberts A D, Lowell K, Brennan P J, Orme I M. Structural basis of capacity of lipoarabinomannan to induce secretion of tumor necrosis factor. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1249–1253. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.1249-1253.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ciacci-Woolwine F, Kucera L S, Richardson S H, Iyer N P, Mizel S B. Salmonellae activate tumor necrosis factor alpha production in a human promonocytic cell line via a released polypeptide. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4624–4633. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4624-4633.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dellacasagrande J, Capo C, Raoult D, Mege J L. IFN-gamma-mediated control of Coxiella burnetii survival in monocytes. The role of apoptosis and TNF. J Immunol. 1999;162:2259–2265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dellacasagrande J, Ghigo E, Capo C, Raoult D, Mege J L. Coxiella burnetii survives in monocytes from patients with Q fever endocarditis: involvement of tumor necrosis factor. Infect Immun. 2000;68:160–164. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.160-164.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eckmann L, Kagnoff M F, Fierer J. Epithelial cells secrete the chemokine interleukin-8 in response to bacterial entry. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4569–4574. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4569-4574.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gajdosova E, Kovacova E, Toman R, Skultety L, Lukacova M, Kazar J. Immunogenicity of Coxiella burnetii whole cells and their outer membrane components. Acta Virol. 1994;38:339–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gresham H D, Adams S P, Brown E J. Ligand binding specificity of the leukocyte response integrin expressed by human neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:13895–13902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hackstadt T, Peacock M G, Hitchcock P J, Cole R L. Lipopolysaccharide variation in Coxiella burnetii: intrastrain heterogeneity in structure and antigenicity. Infect Immun. 1985;48:359–365. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.2.359-365.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hauf N, Goebel W, Friedler F, Sokolovic Z, Kuhn M. Listeria monocytogenes infection of P388D1 macrophages results in a biphasic NF-κB (RelA/p50) activation induced by lipoteichoic acid and bacterial phospholipases and mediated by IκBα and IκBβ degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9394–9399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henderson B, Poole S, Wilson M. Bacterial modulins: a novel class of virulence factors which cause host tissue pathology by inducing cytokine synthesis. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:316–341. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.2.316-341.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hermann P, Armant M, Brown E, Rubio M, Ishihara H, Ulrich D, Caspary R G, Lindberg F P, Armitage R, Maliszewski C, Delespesse G, Sarfati M. The vitronectin receptor and its associated CD47 molecule mediates proinflammatory cytokine synthesis in human monocytes by interaction with soluble CD23. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:767–775. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.4.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Izzo A A, Marmion B P. Variation in interferon-gamma responses to Coxiella burnetii antigens with lymphocytes from vaccinated or naturally infected subjects. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;94:507–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb08226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koster F T, Williams J C, Goodwin J S. Cellular immunity in Q fever: specific lymphocyte unresponsiveness in Q fever endocarditis. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:1283–1289. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.6.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee E H, Rikihisa Y. Absence of tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-6 (IL-6), and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor expression but presence of IL-1β, IL-8, and IL-10 expression in human monocytes exposed to viable or killed Ehrlichia chaffeensis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4211–4219. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.10.4211-4219.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maurin M, Raoult D. Q fever. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:518–553. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.4.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCormick B A, Colgan S P, Delp-Archer C, Miller S I, Madara J L. Salmonella typhimurium attachment to human intestinal epithelial monolayers: transcellular signalling to subepithelial neutrophils. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:895–907. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.4.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meconi S, Jacomo V, Boquet P, Raoult D, Mege J L, Capo C. Coxiella burnetii induces reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton in human monocytes. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5527–5533. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5527-5533.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pacifici R, Basilico C, Roman J, Zutter M M, Samoro S A, McCracken R. Collagen-induced release of interleukin 1 from human blood mononuclear cells: potentiation by fibronectin binding to the α5β1 integrin. J Clin Investig. 1992;89:61–67. doi: 10.1172/JCI115586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanguedolce M V, Capo C, Bongrand P, Mege J L. Zymosan-stimulated tumor necrosis factor-α production by human monocytes. Down-modulation by phorbol ester. J Immunol. 1992;148:2229–2236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwartz M A, Schaller M D, Ginsberg M H. Integrins: emerging paradigms of signal transduction. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:549–589. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skultety L, Toman R, Patoprsty V. A comparative study of lipopolysaccharides from two Coxiella burnetii strains considered to be associated with acute and chronic Q fever. Carbohydr Polymers. 1998;35:189–194. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toman R, Skultety L. Structural study on a lipopolysaccharide from Coxiella burnetii strain Nine Mile in avirulent phase II. Carbohydr Res. 1996;283:175–185. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(96)87610-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Troelstra A, de Graaf-Miltenburg L A M, van Bommel T, Verhoef J, van Kessel K P M, van Strijp J A G. Lipopolysaccharide-coated erythrocytes activate human neutrophils via CD14 while subsequent binding is through CD11b/CD18. J Immunol. 1999;162:4220–4225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tujulin E, Lilliehöök B, Macellaro A, Sjöstedt A, Norlander L. Early cytokine induction in mouse P388D1 macrophages infected by Coxiella burnetii. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1999;68:159–168. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(99)00023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams J C, Waag D M. Antigens, virulence factors, and biological response modifiers of Coxiella burnetii: strategies for vaccine development. In: Williams J C, Thompson H A, editors. Q fever: the biology of Coxiella burnetii. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 175–222. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wollenweber H W, Schramek S, Moll H, Rietschel E T. Nature and linkage type of fatty acids present in lipopolysaccharides of phase I and II Coxiella burnetii. Arch Microbiol. 1985;142:6–11. doi: 10.1007/BF00409228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamamoto Y, Okubo S, Klein T W, Onozaki K, Saito T, Friedman H. Binding of Legionella pneumophila to macrophages increases cellular cytokine mRNA. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3947–3956. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3947-3956.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yao L, Bengualid V, Lowy F D, Gibbons J J, Hatcher V B, Berman J W. Internalization of Staphylococcus aureus by endothelial cells induces cytokine gene expression. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1835–1839. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1835-1839.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]