Abstract

Background:

Research on Mental Health Literacy (MHL) has been growing in different geographical and cultural contexts. However, little is known about the relationship between immigrant generations, acculturation, stigma, and MHL among immigrant populations.

Aims:

This study aims to examine differences in MHL among immigrant generations (first, 1.5, and second) from the former Soviet Union (FSU) in Israel and to assess whether differences are accounted for by immigration generation or acculturation.

Method:

MHL was assessed among 420 participants using a cross-sectional survey adapted from the Australian National Survey. Associations of immigrant generation, socio-demographic characteristics, and acculturation with MHL indices were examined using bivariate and multivariable analyses.

Results:

First generation immigrants reported poorer identification of mental disorders and higher personal stigma than both 1.5- and second-generation immigrants. Acculturation was positively associated with identification of mental disorders and negatively associated with personal stigma across all immigrants’ generations. When all variables were entered into a multivariate model predicting MHL indices, acculturation and gender were associated with personal stigma and only acculturation was associated with better identification of mental disorders.

Conclusion:

Differences in MHL among FSU immigrants in Israel are mainly explained by acculturation rather than by immigrant generation. Implications for policy makers and mental health professionals working with FSU immigrants are discussed.

Keywords: Acculturation, former Soviet Union immigrants, immigrant generations, mental disorders, mental health literacy, stigma

Introduction

Mental health literacy (MHL) is defined as ‘knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders which aid their recognition, management or prevention’ (Jorm et al., 1997, p. 182). Recently, MHL has been expanded and redefined as understanding how to achieve and maintain positive mental health, reduce the stigma associated with mental illness and improve the effectiveness of help-seeking behaviors (Kutcher et al., 2016). High MHL includes the ability to recognize specific mental disorders; knowing how to seek mental health information; knowledge of professional help available, of self-treatments strategies, and effective first aid skills to support others who develop a mental disorder or are in a state of mental distress (Jorm et al., 1997; Reavley & Jorm, 2011a).

MHL is especially pertinent in the case of immigrant populations who often experienced mental distress related to economic, cultural, and social changes during their adaptation to a new country (Bas-Sarmiento et al., 2017; Sam & Berry, 2010). Previous studies in Western counties found that first-generation immigrants (FGIs) are at higher risk of developing psychological distress, common mental health disorders (CMHDs), and severe mental illnesses than native-born individuals (see for reviews, Bhugra et al., 2014; Close et al., 2016). Higher levels of mental health problems were recorded even among children of the immigrants who left their country of origin during childhood (‘one and a half generation’ – 1.5) and those who were born in the host country (second-generation immigrants – SGIs; Bourque et al., 2011; Nakash et al., 2012). Researchers suggest that post-migration social risk factors, such as poverty, ethnic disadvantaged status, social exclusion, and discrimination experiences may explain the higher rates of mental disorders among first, 1.5, and SGIs (Anderson & Edwards, 2020; Bas-Sarmiento et al., 2017; Bourque et al., 2011).

Acculturation is an additional post-migration factor which may be associated with mental health issues among immigrants. Acculturation is a process in which the attitudes, values, and practices of people from one culture are modified as a result of contact with a different culture (Sam & Berry, 2010). Acculturation is associated with numerous health behaviors and although the associations are complex, higher acculturation (i.e. involvement in the host culture) is often positively associated with improved socio-economic status, use of preventive services, and health insurance enrollment (Lara et al., 2005). Moreover, studies in the United States of America (USA) also documented a positive association between acculturation and health literacy (HL; Li et al., 2018; Sagong & Yoon, 2021). Studies exploring the relationship between acculturation and mental health indicated less consistent results: although increased acculturation is associated with improved help-seeking behaviors (Orjiako & So, 2014), some studies reported acculturation as being a risk factor for mental distress (Fortuna et al., 2007) while others reported it as being a protective factor (Haasen et al., 2008). However, the relationship between acculturation and MHL among immigrant populations remains understudied.

The context of the current study

The current study focused on MHL among immigrants from the former Soviet Union (FSU) in Israel. Following the collapse of the Soviet regime in the early 1990s, millions of Russian-speaking citizens emigrated to Western countries. To date, about 25 million Russian-speaking immigrants live in Israel, Germany, the USA, Australia, Canada, and other Western countries (Kostareva et al., 2020).

From 1989 to 2015, more than a million FSU citizens immigrated to Israel (Al-Haj, 2019). Despite the relatively high level of education and professional experience of FSU immigrants, they faced various challenges in adapting to Israeli society, primarily due to underemployment, language barriers, limited social networks, and discrimination from the local-born population (Kushnirovich, 2018). Generally, in the first years following immigration, FSU immigrants retained more of their culture of origin, but over time, many gradually adopted the Israeli culture, language, and traditions (Al-Haj, 2019). This acculturation process is noticeable among 1.5 generation who have become more integrated into the occupational, social, and cultural spheres, but in some domains (e.g. leisure activities, family traditions, and help-seeking behaviors), they still hold more ‘Russian’ models of behavior and norms (Knaifel, 2022; Remennick & Prashizky, 2019).

Alongside the higher rates of psychological distress and psychiatric morbidity among FSU immigrants in Israel (e.g. Lubotzky-Gete et al., 2021; Mirsky, 2009), they are characterized by traditionally negative attitudes towards the realm of mental health and low uptake of mental health services, as compared with the native-born population (Levav et al., 1990; Shor, 2006). Researchers interpreted these findings by drawing on historical, social, and cultural barriers which hinder FSU immigrants from seeking help and receiving mental healthcare (Jurcik et al., 2013). These barriers include high levels of social stigma surrounding mental illness (Polyakova & Pacquiao, 2006), prolonged political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union (Lavretsky, 1998), suspicion and distrust of the Soviet and post-Soviet systems (Cavanagh et al., 2021), and limited knowledge of Western mental healthcare and treatments (Dolberg et al., 2019).

Although many studies have focused on mental health issues among FSU immigrants in Israel and other Western countries, very few have specifically examined MHL (Kostareva et al., 2020). In one study which examined MHL in Israel, Nakash et al. (2020) found an association between high emotional distress of older immigrants from the FSU and low MHL, in comparison with the local-born population. However, information is lacking regarding MHL among FSU immigrants who immigrated to Israel as adolescents and children (1.5 generation) or who were born in Israel to immigrant parents (second generation).

The purpose of the present study is to fill this gap, examining the MHL among first, 1.5, and second generation of FSU immigrants in Israel. Specifically, the study proposed the following research questions: (1) Does MHL differ between first, 1.5, and SGIs?; (2) Is there an association between the acculturation level of FSU immigrants and MHL?; (3) Which characteristic is associated with MHL in a multi-variate analysis – acculturation or immigrant generation?; (4) Are there additional demographic characteristics of FSU immigrants which are associated with their MHL?

Method

Participants

A convenience sample of 420 adults participated in the study. Inclusion criteria were: (1) personal or parental history of migration from the FSU to Israel; (2) age of 18 years and older; and (3) reading Hebrew. The total number of respondents who clicked on the link to the survey was 470; 8 (1.7%) of which did not meet the inclusion criteria and 42 (8.9%) did not complete the entire questionnaire. Participants who completed 80% of the survey questions were included in the final sample.

The sample included participants from three sub-groups: first-generation – participants born in FSU who immigrated to Israel in their late adolescence or as adults (16+); 1.5 generation – participants born in FSU and immigrated to Israel in their childhood or early adolescence (0–15 years old); Second-generation – participants born in Israel to one or two immigrant parents from the FSU.

Design and procedure

A cross-sectional design was used for this research. Participants responded to an online survey, using Qualtrics XM software. The survey was administered from May 2021 – to September 2021. We recruited participants using various methods to increase the socio-demographic diversity of the sample. Participants were recruited online using targeted sampling of FSU immigrants from different generations using a polling firm ‘Panel4all’ (https://www.panel4all.co.il/). In addition, we used snowball sampling techniques to increase recruitment by posting on social media networks/WhatsApp groups among students, friends, immigration groups, and mental health professionals.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ruppin Academic Center (#2021-82). All respondents signed an informed consent form before their participation. Respondents’ anonymity was assured and there was no identifying information on the survey participants completed.

Measures

All measures were translated from English to Hebrew and back and tested on a small number of participants using cognitive interviewing (French et al., 2007).

Socio-demographic characteristics

Included gender, age, country of birth, country of parents’ birth, age upon immigration, years lived in Israel, level of education (primary and secondary, post-secondary and college, Bachelor’s student, Bachelor’s degree, Master’s degree, and higher), perceived income adequacy (great difficulty, some difficulty, fairly easy, and living comfortably), professional/academic background, and self-rated health status (5-point scale from very poor to excellent).

Mental health literacy

Questions about MHL were adapted from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health Literacy and Stigma (Reavley & Jorm, 2011a, 2011b), widely used in many international studies (Adu et al., 2021; Thai & Nguyen, 2018). The MHL questions are based on a vignette of a person with a mental disorder. The current study included three vignettes of diagnostically unlabeled psychiatric case stories: depression (Alina’s story), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Michael’s story), and schizophrenia (Alex’s story). The vignettes of CMHs as depression (n = 212) and PTSD (n = 210) were randomly divided between the participants and the more severe condition of schizophrenia was completed by almost all participants (n = 405; 96.4%). Following each vignette, participants were asked to identify: (1) the mental disorder; (2) potential suitable helpers; (3) helpful interventions, and (4) helpful first-aid support (see details on items and scoring in Supplemental Material).

Personal stigma

Stigmatizing attitudes were assessed with nine statements assessing the participant’s personal attitudes towards the person described in the vignettes (Reavley & Jorm, 2011b). Ratings of each statement were made on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 5 = ‘strongly agree’ to 1 = ‘strongly disagree’. The internal reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s alpha) was .74 for depression, .78 for PTSD, and .70 for schizophrenia.

Acculturation

The level of participants’ acculturation was measured by Short Acculturation Scale (SAS; Marin et al., 1987). The SAS consists of 12 items divided into three subscales: language use, media, and ethnic-social relations. The responses are measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (only ‘Russian’) to 5 (only ‘Hebrew/Israeli’). An overall score is averaged across items to obtain a summary score of acculturation ranging from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating higher levels of acculturation. Previous studies supported the construct validity of the SAS scale and were reported to have good internal consistency (Chan & So, 2019). In the current study, the SAS had Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency of .94.

Data analysis

First, sociodemographic characteristics of the sample and MHL were examined, using descriptive statistics. Second, MHL indices were compared between the first-, 1.5-, and SGIs. Identification of specific mental disorders (depression, PTSD, and schizophrenia) were compared across immigrant generations using chi-square tests. MHL indices of potential helpers, suitable interventions, and suitable first-aid support were compared between the generations of immigrants, using one-way ANOVA and post hoc t-tests. Third, the bivariate association between MHL indices and acculturation was assessed using Pearson and Spearman correlations. Lastly, multivariate regression models examined whether acculturation or immigrant generation was associated with MHL when both variables were included in the analyses. A series of hierarchical multivariate regression analyses were conducted. Immigrant generation was entered in the first step; then demographic characteristics (gender, age, education, and income adequacy) were entered in the second step, and lastly, acculturation was entered in the third step. In each analysis, it was examined whether immigrant generation was still associated with MHL in the last step. Data were analyzed using the IBM-SPSS 25.0 software (Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Corp).

Results

Participant’s characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. Participants belonged to three FSU immigrant generations: first (N = 110), 1.5 generation (N = 171), and second (N = 138). Mean time from immigration among first generation was 27.82 years (SD = 7.33) and age of immigration was 28.10 years (SD = 10.07). Mean time from immigration among 1.5 generation was 33.93 years (SD = 10.72) and age of immigration was 7.75 years (SD = 3.94).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of all generations of FSU immigrants (n (%) or M (SD)).

| Characteristics | G1 n = 110 | G1.5 n = 172 | G2 n = 138 | Total n = 420 | Statistics (χ2 or F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | χ2 = 2.32 | ||||

| Men | 41 (37.3%) | 66 (38.4%) | 42 (30.4%) | 149 (35.5%) | p = .314 |

| Women | 69 (62.7%) | 106 (61.6%) | 96 (69.6%) | 271 (64.5%) | |

| Age | F(2,417) = | ||||

| M (SD) | 55.93(11.45) | 41.68 (10.57) | 25.39 (4.62) | 40.06 (15.05) | 324.89** |

| 18–30 | 1 (0.9%) | 9 (5.2%) | 129 (93.5%) | 139 (33.1%) | |

| 31–45 | 20 (18.2%) | 123 (71.5%) | 9 (6.5%) | 152 (36.2%) | |

| 46–65 | 60 (54.5%) | 33 (19.2%) | 0 | 93 (22.1%) | |

| 66–79 | 29 (26.4%) | 7 (4.1%) | 0 | 36 (8.6%) | |

| Years since immigration mean (SD) | 27.82 (7.33) | 33.93 (10.72) | None | None | |

| Age at immigration mean (SD) | 28.10 (10.07) | 7.75 (3.94) | None | None | |

| Education | χ2 = 105.3** | ||||

| Primary and secondary | 11 (10%) | 20 (11.6%) | 40 (29%) | 71 (17%) | |

| Post-secondary/college | 18 (16.4%) | 24 (13.9%) | 25 (18.1%) | 67 (16%) | |

| BA student | 1 (0.9%) | 8 (4.7%) | 34 (24.7%) | 43 (10.2%) | |

| BA degree | 43 (39.1%) | 65 (37.8%) | 33 (23.9%) | 141 (33.5%) | |

| MA degree and higher | 37 (33.6%) | 55 (32%) | 6 (4.3%) | 98 (23.3%) | |

| Income | χ2 = 17.49* | ||||

| Finding it very difficult | 2 (1.8%) | 2 (1.1%) | 9 (6.5%) | 13 (3.1%) | |

| Finding it difficult | 13 (11.8%) | 29 (16.9%) | 33 (23.9%) | 75 (17.9%) | |

| Coping | 61 (55.5) | 82 (47.7) | 64 (46.4%) | 207 (49.2%) | |

| Living comfortably | 34 (30.9%) | 59 (34.3%) | 32 (23.2%) | 125 (29.8%) | |

| Professional/academic background | χ2 = 38.92* | ||||

| Humanities and social sciences | 46 (41.9%) | 86 (50%) | 44 (31.9%) | 176 (41.9%) | |

| Medicine and paramedical sciences | 9 (8.2%) | 12 (7%) | 14 (10.1%) | 35 (8.3%) | |

| Engineering and natural sciences | 36 (32.7%) | 49 (28.5%) | 39 (28.3%) | 124 (29.5%) | |

| Other academic background | 11 (10%) | 11 (6.4%) | 10 (7.2%) | 32 (7.6%) | |

| Non-skilled employment | 8 (7.2%) | 14 (8.1%) | 31 (22.5%) | 53 (12.7%) | |

| Self-rated health | F(2, 417) = 19.37** | ||||

| (M, SD) | 3.33 (0.814) | 3.68 (0.836) | 3.99 (0.828) | 3.69 (0.863) | |

| Very poor | – | 4 (2.3%) | – | 4 (1.0%) | |

| Poor | 16 (14.5%) | 6 (3.5%) | 4 (2.9%) | 26 (6.2%) | |

| Average | 50 (45.5%) | 54 (31.4%) | 36 (26.1%) | 140 (33.3%) | |

| Good | 36 (32.7%) | 85 (49.4%) | 56 (40.6%) | 177 (42.1%) | |

| Excellent | 8 (7.3%) | 23 (13.4%) | 42 (30.4%) | 73 (17.4%) |

Note. First generation (G1), 1.5 generation (G1.5), second generation (G2).

p < .01. **p < .001.

In all three generational groups the total frequency of women was higher (64.5%), with no significance differences between groups. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 79 years (M = 40.06, SD = 15.05) and the first-generation sample was older (M = 55.93, SD = 11.55) than 1.5 (M = 41.68, SD = 10.57), and second generation (M = 25.39, SD = 4.6), F(2,417) = 324.89, p < .001. Additional significant differences between groups were found in education – χ2 = 105.30, p < .001 and in income – χ2 = 17.49, p < .01, so that the SGIs, who were younger, had attained less education and perceived their income as less allowing living comfortably. Significant differences were also found in self-related health, F(2,417) = 19.37, p < .001, so that older FGIs perceived their health as less good.

MHL among immigrant generations

Identification of mental disorders

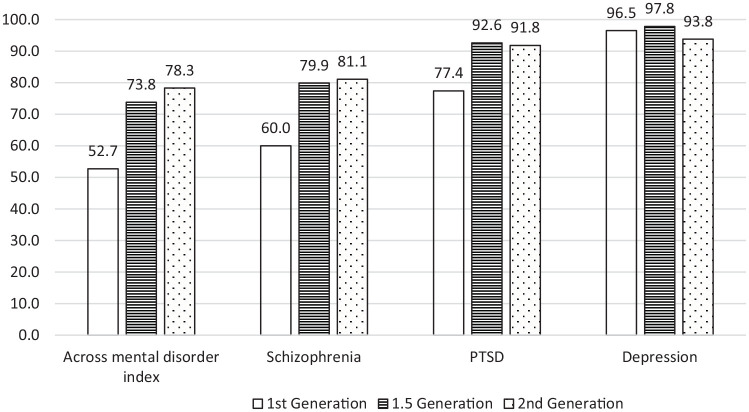

As shown in Figure 1, there was no significant difference between the generation groups in identification of depression disorder (χ2 = 1.66, p = .437) as all groups presented high correct labels (96.5%, 97.8%, and 93.8%). Significant differences were found between the generations in correct identification of PTSD vignette (χ2 = 8.51; p < .014) such that lower identification was recorded among the FGIs (77.4%) comparing with 1.5 (92.6%) and SGIs (91.8%). Significant differences were also found between the generations in the schizophrenia vignette (χ2 = 19.72; p < .001), such that lower identification was recorded among the FGIs (60%) comparing with 1.5 (79.9%) and SGIs (81.8%).

Figure 1.

Identification of mental disorders by immigrant generation.

An index of correct identifications across mental disorders was constructed on a scale (0–2). As each participant responded to two vignettes (schizophrenia vignette and either to the depression or the PTSD vignettes), they could correctly identify none, one or two cases of diagnoses (0 = incorrect in two cases, 1 = correct in one case, and 2 = correct in two cases). A significant difference between the generations was found in the number of correct identifications across mental disorders index (χ2 = 22.87, p < .001), so that FGIs reported a lower correct identification of two mental disorders (52.70%) than both 1.5 (73.80%) and SGIs (78.30%).

Other MHL indices

Table 2 presents the MHL indices of potential helpers, suitable interventions, first aid support as well as personal stigma and acculturation. No significant difference was found between immigrant generations in indices of potential helpers, suitable interventions and first aid support. However, there was a statistically significant difference between immigrant generation in the personal stigma indices. FGIs reported a higher overall stigma (M = 2.57, SD = 0.51) than both 1.5 (M = 2.33, SD = 0.50) and SGIs (M = 2.30, SD = 0.49), F(2,417) = 9.75, p < .001, partial η2 = .045). No significant differences were found between 1.5- and SGIs on stigma, t(417) = 0.58, p = .562, d = 0.06). Lastly, there was a statistically significant difference in acculturation between immigrant generations. FGIs reported significantly lower acculturation (M = 2.59, SD = 0.71) than both 1.5 (M = 3.66, SD = 0.71) and SGIs (M = 3.98, SD = 0.55), F(2, 402) = 137.59, p < .001, partial η2 = .41). Moreover, a significant difference in acculturation was also found between 1.5 and SGIs, so that second generation reported higher acculturation than 1.5 generation, t(402) = −4.10, p < .001, d = −0.503).

Table 2.

Means and SD of MHL indices and acculturation among first, 1.5, and second-generation of FSU immigrants.

| N | M (SD) | Range CI – 95% | Statistics (F) and p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index potential helpers | F(2, 417) = 0.43 | |||

| G1* | 110 | 10.30 (3.18) | 9.70–10.91 | p = .648 |

| G1.5 | 172 | 10.65 (3.04) | 10.19–11.11 | |

| G2 | 138 | 10.54 (2.83) | 10.06–11.02 | |

| Total | 420 | 10.52 (3.01) | 10.23–10.81 | |

| Index suitable interventions | F(2, 417) = 0.72 | |||

| G1 | 110 | 11.07 (3.54) | 10.40–11.74 | p = .485 |

| G1.5 | 172 | 11.50 (3.30) | 11.00–12.00 | |

| G2 | 138 | 11.51 (2.99) | 11.01–12.01 | |

| Total | 420 | 11.39 (3.26) | 11.08–11.70 | |

| Index first aid support | F(2, 417) = 0.42 | |||

| G1 | 110 | 15.10 (2.72) | 14.59–15.62 | p = .658 |

| G1.5 | 172 | 15.19 (2.74) | 14.77–15.60 | |

| G2 | 138 | 15.39 (2.10) | 15.03–15.74 | |

| Total | 420 | 15.23 (2.54) | 14.99–15.47 | |

| Index personal stigma | F(2, 417) = 9.75 | |||

| G1 | 110 | 2.57 a (0.51) | 2.47–2.66 | p < .001 |

| G1.5 | 172 | 2.33 (0.50) | 2.26–2.41 | |

| G2 | 138 | 2.30 (0.49) | 2.22–2.38 | |

| Total | 420 | 2.38 (0.51) | 2.33–2.43 | |

| Acculturation | F(2, 402) = 137.5 | |||

| G1 | 105 | 2.59 a (0.71) | 2.45–2.73 | p < .001 |

| G1.5 | 164 | 3.66 b (0.71) | 3.55–3.77 | |

| G2 | 136 | 3.98 (0.55) | 3.88–4.07 | |

| Total | 405 | 3.49 (0.86) | 3.41–3.57 |

First generation (G1), 1.5 generation (G1.5), and second generation (G2).

First generation is significantly different than 1.5 and second generations

1.5 generation is significantly different than second generation.

Note. Bold values are statistically significant.

Bivariate associations between acculturation and MHL across generations

Bivariate correlations between acculturation and MHL indices across generations are presented in Table 3. A positive correlation was found between acculturation and identification of mental disorder (rs = .25, p < .001). A significant weak positive correlation was also observed between acculturation and the index of suitable interventions (r = .10, p < .037) and conversely a significant negative correlation was found between acculturation and personal stigma index (r = −.25, p < .001), evident in depression stigma (r = −.28, p < .001), PTSD (r = −.24, p = .001), and schizophrenia (r = −.18, p < .001).

Table 3.

Correlation between acculturation and MHL across generations.

| Acculturation | ||

|---|---|---|

| r | p-Value | |

| Index identification of mental disorders | .25 a | <.001 |

| Index potential helpers | .08 | .092 |

| Index suitable interventions | .10 | .037 |

| Index first aid support | .00 | .871 |

| Index personal stigma | −.25 | <.001 |

Spearman’s.

Note. Bold values are statistically significant.

Association between immigrant generations, acculturation, demographic characteristics, and MHL indices: A multi-variate analysis

A multi-variate analysis was conducted on the dependent variables (personal stigma and identification of mental disorders) in which a significant difference between generations was found. Hierarchical linear regression analysis on the stigma index as outcome measure, and generations (first step), gender, age, education, and income (second step), and acculturation (third step) as associated variables was conducted. As can be seen in Table 4, gender was associated with higher stigma scores (β = −.21, p < .001), so that women held lower stigma compared with men. Age, education, and income were not significantly associated with stigma towards persons with mental health issues. Acculturation was negatively associated with general stigma (β = −.16, p = .01), with participants higher in acculturation reporting lower personal stigma. Note that the generation variable was significantly associated with stigma in the first and the second steps of analysis, but became nonsignificant in the third step, once acculturation was included.

Table 4.

Hierarchical linear regression examining predictors of general stigma among FSU immigrants across generations (n = 405).

| Variables | B | SE (B) | β | t | p-Value | Partial r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | ||||||

| (Constant) | 2.57 | 0.05 | 52.28 | <.001 | ||

| Dummy G1.5 | −0.23 | 0.06 | −.22 | −3.58 | <.001 | −.18 |

| Dummy G2 | −0.27 | 0.07 | −.25 | −4.09 | <.001 | −.20 |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| (Constant) | 2.87 | 0.2 | 14.18 | <.001 | ||

| Dummy G1.5 | −0.10 | 0.07 | −.19 | −2.71 | .007 | −.14 |

| Dummy G2 | −0.20 | 0.10 | −.18 | −1.92 | .055 | −.10 |

| Gender | −0.25 | 0.05 | −.23 | −4.76 | <.001 | −.23 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | .06 | .74 | .46 | .04 |

| Education | −0.00 | 0.02 | −.02 | −.36 | .718 | −.02 |

| Income | 0.01 | 0.03 | .02 | .38 | .707 | .02 |

| Step 3 | ||||||

| (Constant) | 3.08 | 0.22 | 14.22 | <.001 | ||

| Dummy G1.5 | −0.09 | 0.08 | −.09 | −1.07 | .28 | −.05 |

| Dummy G2 | −0.06 | 0.12 | −.05 | −.49 | .626 | −.02 |

| Gender | −0.22 | 0.05 | −.21 | −4.32 | <.001 | −.21 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | .07 | .85 | .395 | .04 |

| Education | −0.01 | 0.02 | −.02 | −.36 | .718 | −.02 |

| Income | 0.01 | 0.03 | .01 | .18 | .856 | .01 |

| Acculturation | −0.01 | 0.04 | −.16 | −2.59 | .010 | −.13 |

First generation (G1), 1.5 generation (G1.5), and second generation (G2).

Note. Bold values are statistically significant.

Lastly, ordinal regression analyses were conducted to examine the association between immigrant generation, demographic variables, and acculturation with correct identification across mental disorders. In this analysis only acculturation was significantly associated with correct identification of mental disorders: Estimate = 0.43, SE = 0.17, Wald = 6.05, 95% CI [0.09, 0.76], p < .014, such that people high in acculturation recognized mental disorders more often.

Discussion

The current study examined the relationship between immigrant generation, acculturation, and MHL among FSU immigrants in Israel. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine this constellation of variables among immigrant populations in general and among FSU immigrants specifically.

The current study found a difference between immigrant generations in specific indices of MHL. The main differences between generations were found in the identification of mental disorders and in stigma towards people with mental conditions. Specifically, no differences were found between immigrant generations in the identification of depression, but in the case of PTSD, schizophrenia, and across mental disorders, the 1.5- and SGIs had better identification rates than FGIs. Lack of difference in identification rates in depression could stem from the fact that identification was highest in this condition and exhibited a ceiling effect; depression is more common in most populations than PTSD and schizophrenia (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013) so most possibly the latter diagnoses are less familiar, including among FSU immigrants. The low rates of PTSD and schizophrenia identification among the FGIs, born and educated in the FSU, is noteworthy. Despite the Soviet Union’s anguished history, the concept of trauma and PTSD diagnosis is still largely overlooked by the Russian population (Merridale, 2000), while a schizophrenia diagnosis was stigmatically associated with a more chronic and severe mental health condition (Lavretsky, 1998). Conversely, 1.5- and SGIs, who were educated and socialized in Israel and are more acculturated to the host country, are probably more familiar with these disorders: PTSD is well known and media-covered in Israeli society, due to the holocaust collective trauma, military conflicts, and terror (Friedman-Peleg, 2017). In addition, recovery-oriented community rehabilitation services for people with schizophrenia and other severe mental conditions are established within the Rehabilitation Law in Israel (Aviram, 2017).

The current study also identified a difference between immigrant generations in the stigma indices, as FGIs exhibit higher stigma than 1.5- and SGIs. In the Soviet and post-Soviet Union, people with psychiatric conditions were institutionally discriminated against and marginalized by the government and society (Gaines, 2004). Apparently, stigmatic attitudes of mental vulnerability, internalized by Soviet-Russian people (Nersessova et al., 2019), persisted even after they emigrated to Western countries. For example, quantitative studies in Israel and UK found that FSU immigrants were less tolerant and more judgmental towards people with mental conditions, as compared to the local-born populations (Levav et al., 1990; Shulman & Adams, 2002). Several qualitative studies in Israel and USA also reported that higher mental health stigma is characteristic of elderly and less acculturated FSU immigrants (Dolberg et al., 2019; Polyakova & Pacquiao, 2006).

The main finding of the current study is that the level of acculturation among immigrants – across immigrant generations – is associated with identification of mental conditions and stigma. Indeed, the results show that more acculturated FSU immigrants in Israeli society have better recognition of mental health problems and less stigmatic attitudes toward people with mental health conditions than FGIs, who tend to preserve more of the Russian culture. The current study highlights the crucial role of origin culture in shaping mental health stigma and the role of greater acculturation toward Western host culture as a protective factor in the case of FSU immigrants, even exceeding the impact of age, education, income, and immigrant generation.

Previous investigations of the socio-demographic factors related to MHL have found that female gender, higher education, younger age, and higher income are associated with higher MHL (Cotton et al., 2006; Yu et al., 2015). These findings were mostly not replicated in the current study; for example, although the first generation has higher education and higher income, they had poorer MHL than the SGIs, which highlights the importance of acculturation in MHL among immigrants. Concomitantly, our findings are congruent with other studies which have found that female gender and younger age are associated with higher MHL (Yu et al., 2015).

In general, our findings indicate that MHL among FSU immigrants across all generations is high in the knowledge dimensions and this finding can probably be attributed to socio-demographic and contextual factors. First, highly educated people, such as FSU immigrants in our sample, are likely to seek knowledge by reading a wide range of materials from various sources, resulting in the acquisition of more general information, as well as knowledge about mental health issues. This is exhibited in the high identification rates of mental disorders and relatively high level of knowledge of potential helpers, interventions, and first-aid support across all FSU generations. Secondly, their immigrant status and higher prevalence of mental distress (Jurcik et al., 2013; Mirsky, 2009) may have made them more familiar with mental health concerns. Thus, it is possible that immigration-related experiences of mental distress can account for the relatively high MHL.

Limitations and strengths

The present study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design of the study precludes evaluation of temporal sequence of acculturation and MHL outcomes, hence causal relationships cannot be determined. Secondly, data collection was conducted online and thus participation was preliminarily availed only to Internet users. This strategy might be a potential source of selection bias and could limit generalization of the results. This limitation is of less concern among the young and middle-aged adults (1.5 and SGIs), due to the almost full Internet penetration in these age groups, but may have produced a selection bias amongst the older FGIs (Nakash et al., 2020). Thirdly, the survey was conducted in Hebrew, and thus may have excluded older participants or participants with low Hebrew language skills. Concomitantly, this limitation also strengthens the study’s findings: even though the more acculturated FGIs (with fluent Hebrew) participated in this study, there were still significant differences between generations. Fourthly, the current study focused on a specific cultural context, and therefore the generalizability of the current findings to FSU immigrants outside Israel and to others immigrant communities is somewhat limited. Lastly, the current study focused on a limited set of demographic variables—immigrant generation, age, gender, income, and education—but not on other demographics such as marital status and personal or familial experiences of mental illness, which might also be associated with MHL.

A strength of the present study is that it focused on three immigrant generations and three different mental disorders with a high prevalence in the immigrant population (Close et al., 2016). In addition, we examined various indicators of MHL using validated measures. Beyond that, we focused on an unexplored domain – the relationship between a more structural and objective attribute as an immigrant generation, a more flexible and subjective attribute as acculturation, and their distinct association with MHL. Lastly, the population of FSU immigrants is under-represented in HL research, despite being one of the largest immigrant populations in the world and in Israel (Kostareva et al., 2020).

Implications and future directions

This study had some important implications for policymakers and mental health professionals working with the immigrant population in general and FSU immigrants, specifically. On the services and policy levels, the implementation of culturally adapted psychoeducation programs in mental healthcare and social campaigns to reduce mental health stigma in the Russian language are needed to strengthen the MHL among FSU immigrants whose level of acculturation is low. These culturally adapted programs are especially important for highlighting the recognition of PTSD and schizophrenia spectrum disorders, which are less well recognized among the Russian-speaking community. This is crucial, because post-migration social risk factors rendered FGIs more vulnerable to these specific mental disorders (Close et al., 2016). Therefore, early identification of symptoms of these disorders could improve their help-seeking behaviors and prevent more severe and persistent mental health conditions.

Our findings also suggest that attitudes and awareness of mental health conditions among FGIs are less likely to be transmitted to the younger and more acculturated generations. The current findings reveal that mental health attitudes, as exhibited in the stigma of 1.5 generation, are more similar to the second generation than to the attitudes of the first generation. It seems that 1.5 and SGIs have disassociated ‘Russian’ models and norms of behaviors in mental healthcare and exchanged them for more tolerant Western norms.

Concomitantly, our findings suggest that acculturation plays a central role in the recognition of mental disorders and personal stigma, even three decades after immigration to a new country. Therefore, it is important to assess the acculturation level in future studies which will focus on MHL among other immigrant populations. Future studies may examine more expanded set of socio-demographic and clinical variables which might also be associated with MHL as well as the generalizability of the current results in different cultural and geographical contexts. In international studies, it is advisable to compare the current results on MHL with those of Russian-speaking immigrants in other Western countries.

Conclusions

The current study was conducted to document MHL in three generations of FSU immigrants in Israel. This study uncovered associations between acculturation and MHL, exceeding impact of immigrant generation and other socio-demographic factors. The association between acculturation and MHL was evident in mental disorder identification and personal stigma, which may be one of the reasons for a treatment gap (Jorm et al., 2017) among more vulnerable FSU immigrants. Accordingly, implementation for culturally adapted psychoeducation programs and social campaign targeting FSU immigrants to use mental health services when needed are proposed to alleviate these acculturation differences.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-isp-10.1177_00207640221134236 for Immigrant generation, acculturation, and mental health literacy among former Soviet Union immigrants in Israel by Evgeny Knaifel, Rafael Youngmann and Efrat Neter in International Journal of Social Psychiatry

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David Piterman for his assistance with the statistical analyses of this research project.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by a grant awarded to the first author from the Institute for Immigration and Social Integration, Ruppin Academic Center, Emek Hefer, Israel. The funders had no role in the study.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ruppin Academic Center (#2021-82).

Informed consent: All respondents signed an informed consent form before their participation.

ORCID iD: Evgeny Knaifel  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7019-4272

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7019-4272

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Adu P., Jurcik T., Grigoryev D. (2021). Mental health literacy in Ghana: Implications for religiosity, education, and stigmatization. Transcultural Psychiatry, 58(4), 516–531. 10.1177/13634615211022177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Haj M. I. (2019). The russians in Israel: A new ethnic group in a tribal society. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-V) (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishingr. https://doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K. K., Edwards J. (2020). Age at migration and the risk of psychotic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 141(5), 410–420. 10.1111/acps.13147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviram U. (2017) The reform of rehabilitation in the community of persons with psychiatric disabilities: Lessons from the Israeli experience. Community Mental Health Journal, 53(5), 550–559. 10.1007/s10597-016-0058-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bas-Sarmiento P., Saucedo-Moreno M. J., Fernández-Gutiérrez M., Poza-Méndez M. (2017). Mental health in immigrants versus native population: A systematic review of the literature. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 31(1), 111–121. 10.1016/j.apnu.2016.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhugra D., Gupta S., Schouler-Ocak M., Graeff-Calliess I., Deakin N. A., Qureshi A., Dales J., Moussaoui D., Kastrup M., Tarricone I., Carta M. (2014). EPA guidance mental health care of migrants. European Psychiatry, 29(2), 107–115. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourque F., Van der Ven E., Malla A. (2011). A meta-analysis of the risk for psychotic disorders among first-and second-generation immigrants. Psychological Medicine, 41(05), 897–910. 10.1017/S0033291710001406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh D., Jurcik T., Charkhabi M. (2021). How does trust affect help-seeking for depression in Russia and Australia? International Journal of Social Psychiatry. Advance online publication. 10.1177/00207640211039253 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chan D. N., So W. K. (2019). Measuring acculturation of Pakistani women: A psychometric evaluation of urdu version of the short acculturation scale. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing, 6(4), 349–355. 10.4103/apjon.apjon_28_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Close C., Kouvonen A., Bosqui T., Patel K., O’Reilly D., Donnelly M. (2016). The mental health and wellbeing of first-generation migrants: A systematic-narrative review of reviews. Globalization and Health, 12(47), 1–13. 10.1186/s12992-016-0187-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton S. M., Wright A., Harris M. G., Jorm A. F., McGorry P. D. (2006). Influence of gender on mental health literacy in young Australians. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40(9), 790–796. 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01885.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolberg P., Goldfracht M., Karkabi K., Bleichman I., Fleischmann S., Ayalon L. (2019). Knowledge and attitudes about mental health among older immigrants from the former Soviet Union to Israel and their primary care physicians. Transcultural Psychiatry, 56(1), 123–145. 10.1177/1363461518794233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortuna L. R., Perez D. J., Canino G., Sribney W., Alegria M. (2007). Prevalence and correlates of lifetime suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among Latino subgroups in the United States. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 68(4), 572–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French D. P., Cooke R., Mclean N., Williams M., Sutton S. (2007). What do people think about when they answer theory of planned behaviour questionnaires? A “think aloud” study. Journal of Health Psychology, 12, 672–687. 10.1177/1359105307078174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman-Peleg K. (2017). PTSD and the politics of trauma in Israel: A nation on the couch. University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gaines D. (2004). Geographical perspectives on disability: A socio-spatial analysis of the mentally disabled population in Russia. Middle States Geographer, 37(1), 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Haasen C., Demiralay C., Reimer J. (2008). Acculturation and mental distress among Russian and Iranian migrants in Germany. European Psychiatry, 23(S1), S10–S13. 10.1016/S0924-9338(08)70056-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm A. F., Korten A. E., Jacomb P. A., Christensen H., Rodgers B., Pollitt P. (1997). “Mental health literacy”: A survey of the public’s ability to recognize mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Medical Journal of Australia, 166(4), 182–186. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb140071.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm A. F., Patten S. B., Brugha T. S., Mojtabai R. (2017). Has increased provision of treatment reduced the prevalence of common mental disorders? Review of the evidence from four countries. World Psychiatry, 16(1), 90–99. 10.1002/wps.20388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurcik T., Chentsova-Dutton Y. E., Solopieieva-Jurcikova I., Ryder A. G. (2013). Russians in treatment: The evidence base supporting cultural adaptations. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69)7), 774–791. 10.1002/jclp.21971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaifel E. (2022). Acculturation as a two-way process: Immigrants from the Former Soviet Union in Israel. In Ben-Porat G., Filc D., Kabalo P., Feniger Y., Mirsky J. (Eds.), Routledge handbook of contemporary Israel (pp. 323–336). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kostareva U., Albright C. L., Berens E. M., Levin-Zamir D., Aringazina A., Lopatina M., Ivanov L. L., Sentell T. L. (2020). International perspective on Health Literacy and health equity: Factors that influence the Former Soviet Union immigrants. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6), 2155. 10.3390/ijerph17062155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushnirovich N. (2018). Wage gap paradox: The case of immigrants from the FSU in Israel. International Migration, 56(5), 243–259. 10.1111/imig.12490 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kutcher S., Wei Y., Coniglio C. (2016). Mental health literacy: Past, present, and future. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 61(3), 154–158. 10.1177/0706743715616609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara M., Gamboa C., Kahramanian M. I., Morales L. S., Hayes Bautista D. E. (2005). Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: A review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annual Review of Public Health, 26, 367–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavretsky H. (1998). The Russian concept of schizophrenia: A review of the literature. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 24(4), 537–557. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levav I., Kohn R., Flaherty J. A., Lerner Y., Aisenberg E. (1990). Mental health attitudes and practices of Soviet immigrants. The Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, 27(3), 131–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C. C., Matthews A. K., Dong X. (2018). The influence of health literacy and acculturation on cancer screening behaviors among older Chinese Americans. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, 5(4), 472–481. 10.1177/2333721418778193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubotzky-Gete S., Gete M., Levy R., Kurzweil Y., Calderon-Margalit R. (2021). Comparing the different manifestations of postpartum mental disorders by origin, among immigrants and native-born in Israel according to different mental scales. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11513. 10.3390/ijerph182111513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G., Sabogal F., Marin B. V., Otero-Sabogal R., Perez-Stable E. J. (1987). Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 9(2), 183–205. 10.1177/07399863870092005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merridale C. (2000). The collective mind: Trauma and shell-shock in twentieth-century Russia. Journal of Contemporary History, 35(1), 39–55. 10.1177/002200940003500105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirsky J. (2009). Mental health implications of migration: A review of mental health community studies on Russian-speaking immigrants in Israel. Journal of Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 44(3), 179–187. 10.1007/s00127-008-0430-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakash O., Hayat T., Abu Kaf S., Cohen M. (2020). Association between knowledge about how to search for mental health information and emotional distress among older adults: The moderating role of immigration status. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 63(1–2), 78–91. 10.1080/01634372.2019.1709247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakash O., Nagar M., Shoshani A., Zubida H., Harper R. A. (2012). The effect of acculturation and discrimination on mental health symptoms and risk behaviors among adolescent migrants in Israel. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18(3), 228–238. 10.1037/a0027659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nersessova K. S., Jurcik T., Hulsey T. L. (2019). Differences in beliefs and attitudes toward Depression and Schizophrenia in Russia and the United States. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 65(5), 388–398. 10.1177/0020764019850220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orjiako O. E. Y., So D. (2014). The role of acculturative stress factors on mental health and help-seeking behavior of sub-Saharan African immigrants. International Journal of Culture and Mental Health, 7(3), 315–325. [Google Scholar]

- Polyakova S. A., Pacquiao D. F., (2006). Psychological and mental illness among elder immigrants from the former Soviet Union. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 17(1), 40–49. 10.1177/1043659605281975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reavley N. J., Jorm A. F. (2011. a). Recognition of mental disorders and beliefs about treatment and outcome: Findings from an Australian national survey of mental health literacy and stigma. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 45(11), 947–956. 10.3109/00048674.2011.621060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reavley N. J., Jorm A. F. (2011. b). Stigmatizing attitudes towards people with mental disorders: Findings from an Australian national survey of mental health literacy and stigma. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 45(12), 1086–1093. 10.3109/00048674.2011.621061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remennick L., Prashizky A. (2019). Generation 1.5 of Russian Israelis: Integrated but distinct. Journal of Modern Jewish Studies, 18(3), 263–281. 10.1080/14725886.2018.1537212 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sagong H., Yoon J. Y. (2021). Pathways among frailty, health literacy, acculturation, and social support of middle-aged and older Korean immigrants in the USA. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 1245. 10.3390/ijerph18031245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sam D. L., Berry J. W. (2010) Acculturation: When individuals and groups of different cultural backgrounds meet. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(4), 472–481. 10.1177/1745691610373075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shor R. (2006) When children have problems: Comparing help-seeking approaches of Israeli-born parents and immigrants from the former Soviet Union. International Social Work, 49(6), 745–756. 10.1177/0020872806070971 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman N., Adams B. (2002) A comparison of Russian and British attitudes towards mental health problems in the community. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 48(4), 266–278. 10.1177/002076402128783307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thai Q. C. N., Nguyen T. H. (2018) Mental health literacy: Knowledge of depression among undergraduate students in Hanoi, Vietnam. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 12(1), 1–8. 10.1186/s13033-018-0195-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y., Liu Z. W., Hu M., Liu X. G., Liu H. M., Yang J. P., Zhou L., Xiao S. Y. (2015). Assessment of mental health literacy using a multifaceted measure among a Chinese rural population. BMJ Open, 5(10), e009054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-isp-10.1177_00207640221134236 for Immigrant generation, acculturation, and mental health literacy among former Soviet Union immigrants in Israel by Evgeny Knaifel, Rafael Youngmann and Efrat Neter in International Journal of Social Psychiatry