Abstract

Endoscopic (END-DCR) and external dacryocystorhinostomies (EXT-DCR) are nowadays considered the gold standard techniques for non-oncologic distal acquired lacrimal disorders (DALO). However, no unanimous consensus has been achieved on which of these surgeries is the most suitable to the individual patient. Herein, we review the available literature of the last 30 years with the aim of defining a simple and reproduceable treatment algorithm to treat DALO. A search of PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus and Cochrane databases was last performed in December 2021 to examine evidence regarding the role of END-DCR and EXT-DCR in primary and revision surgeries. If considered primary surgeries, END-DCR should be preferred in case of intranasal comorbidities, given the possibility to directly visualize and treat potential intranasal pathologies. Conversely, EXT-DCR should be chosen in case of need/preference for local anesthesia, given the major historical experience and wider surgical field that helps to resolve intra-operatory complications (e.g., bleeding) in an uncollaborative patient. In the absence of the abovementioned conditions, the decision of one or other approach should be discussed with the patient. In recurrent cases, END-DCR should be considered the treatment of choice given the major likelihood to visualize the causes of primary failure and directly resolve it. In conclusion, END-DCR should be considered the treatment of choice in revision cases or in primary ones associated with intranasal pathologies, whereas EXT-DCR should be chosen if local anesthesia is needed. In the absence of these scenarios, it is still open to debate which of these two approaches should be used.

Keywords: Lacrimal disease obstructions, lacrimal disease obstructions: lower system disease, lacrimal disease obstructions: upper system disease, lacrimal disease obstructions: diagnostic tests, lacrimal disease obstructions: lacrimal system trauma

Introduction

Distal acquired lacrimal obstruction (DALO), defined as an obstruction that occurs distal to the valve of Rosenmuller, is an adulthood pathology that mainly affects middle-aged females. 1 Clinically, it appears as monolateral epiphora that can be associated with an acute/chronic supra-infection, commonly known as dacryocystitis.

Excluding lacrimal malignancies, which require specific management related to the histology,2,3 external dacryocystorhinostomy (EXT-DCR) was historically considered the treatment of choice. However, over the past 40 years, increasing evidence has shown that endoscopic endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy (END-DCR) yields comparable results and is associated with several advantages such as the absence of external scar and less surgical time, with the result that the endoscopic approach has gained popularity even if an external approach is still preferred.4–6 Recently, a systematic review has demonstrated that primary or secondary (non-oncologic) lacrimal obstructions can be equally treated with EXT-DCR or END-DCR, given the comparable success rates of nearly 90–95% of cases, with no superiority of one over the other.7,8 In particular, among all surgical and non-surgical approaches to DALO, these two surgeries have demonstrated superiority compared to others like a trans-canalicular approach, balloon dacryoplasty, and stenting/probing of the lacrimal pathway. 7 As a result, END-DCR and EXT-DCR should be considered the gold standard techniques for DALO without, however, a clear standardization of the surgical indications for one procedure over the other. In addition, several factors have been hypothesized to influence the therapeutic decision between these two approaches, although no unanimous consensus has been achieved. 5

The aim of this article is to critically review the literature regarding the management of DALO in order to propose a clear, standardized, and reproduceable therapeutic flow-chart to help clinicians decide whether EXT-DCR or END-DCR is more appropriate for each patient.

Methods

The ophthalmology and ENT departments of our Hospital have developed a close collaboration for the management of DALO.4,9 As an attempt to methodically compare the possible therapeutical strategies for DALO, systematic reviews on PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library were performed. Different surgical options and post-surgical therapies for DCR were compared, as previously published by our group in the last years.8,10 These papers are of utmost importance in the evaluation of the efficacy of each therapeutic strategy, but may not be sufficient to support one technique over the other in specific individual conditions.

In particular, these meta-analyses have demonstrated the superiority of endoscopic and external DCR over other surgical options but, in the choice between the two, a complex interaction of anatomical conditions, comorbidities and patient preference should be considered. Therefore, as an attempt to identify the most suitable approach for the single patient in the era of individualized medicine, a literature review was performed in December 2021 through a structured search in PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus and Cochrane Databases. This review was intended to summarize and update the evidence of the previous research with a focus on specific conditions, and END-DCR and EXT-DCR were examined for both primary and revision cases, addressing potential factors that could influence the final decision of the surgical approach: among these, possible systemic/nasal comorbidities, age of the patient and the choice of anesthesia were taken into account. The search string included “dacryocystorhinostomy” in combination with each of the potential factors previously described. All papers included had to be written in English and describe a clear functional success rate, defined as symptom resolution or less than MUNK 2 scale. 11 Exclusion criteria were mixed cohort study of acquired and congenital obstruction and articles analyzing the management of oncologic obstruction of the lacrimal pathway.

The selected papers were then ranked according to their level of evidence and, according to the methodology described by O’Brien et al., 12 were qualitatively reviewed with the aim of establishing a reproduceable “decision making” algorithm in the management of DALO.

Results

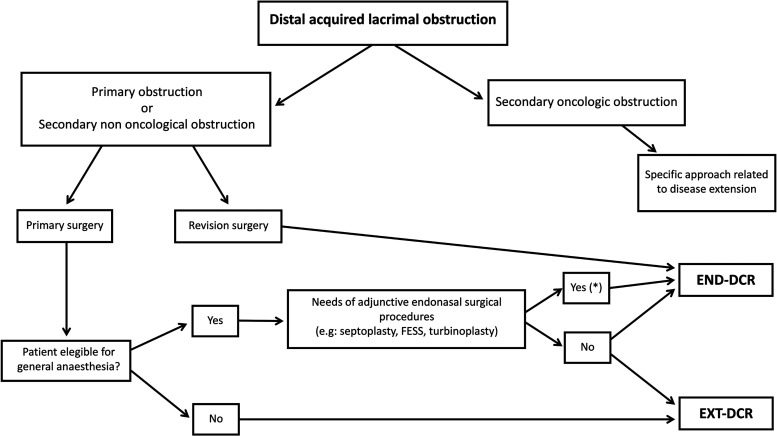

When initiating management of a patient suspected to have a distal lacrimal obstruction, a multidisciplinary approach between an ophthalmic surgeon and otolaryngologist is highly recommended due to the need to evaluate the correct lacrimal diagnosis and to identify possible intranasal comorbidities. 13 If necessary, radiological imaging is feasible (e.g., maxilla-facial CT), which, for some authors, is particularly indicated in cases of recurrence, while for others is used to achieve a correct diagnosis. 14 When a DALO is identified, EXT-DCR and END-DCR can be equally considered the treatments of choice given the similar functional success rate of these procedures, 7 although no unanimous consensus has been achieved on the selection criteria for one or the other option. The majority of surgical indications are in fact mainly influenced by the medical background of the clinician to whom the patient is referred. 5 Nevertheless, in a scenario of personalized medicine, the decision between an external and endoscopic approach should be tailored to the patient and some considerations should be taken into account. Among all aspects that should be considered to treat a DALO, the most relevant identified in the literature are: (1) primary vs secondary etiology; (2) primary vs revision surgery; (3) general comorbidities that could influence the decision of general vs local anesthesia; (4) presence of concomitant sino-nasal pathologies; (5) age of the patient (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Therapeutic flow-chart for management of non-oncologic distal acquired lacrimal obstruction. *Antero-superior deviation of the nasal septum are excluded because it causes difficult visualization of the surgical field so that an EXT-DCR may be advisable. END-DCR: endoscopic endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy; EXT-DCR: external dacryocystorhinostomy.

Primary vs secondary etiology

The etiology of lacrimal obstruction is a critical factor that should be taken into account in the diagnostic work-up. In the majority of patients, the distal obstruction is believed to be idiopathic, also known as primary, while secondary etiologies represent a minority of the causes of obstruction.15,16 However, their distinction is critically important as, in the latter group, specific therapeutical options should be considered; furthermore, several authors have pointed out the importance of dividing secondary cases into oncologic and non-oncologic etiology.3,17 In fact, considering that the non-oncologic obstructions mainly affect the naso-lacrimal duct, so that the surgical options remain almost identical to the primary etiology (EXT-DCR and END-DCR), the oncologic nature of the DALO may involve any level of the lacrimal pathway and present a treatment algorithm that is highly influenced by the histology and infiltration of the surrounding structures of the malignancy. 18 Considering this, a complete assessment of all possible treatments for malignancies of the lacrimal pathway is beyond the scope of this manuscript that mainly analyzes the treatment algorithm for primary and secondary non-oncologic etiologies.

Primary vs revision surgery

END-DCR and EXT-DCR present a high success rate of nearly 90%, although there is a possibility to have recurrences that need revision surgeries. Among all causes for failure of DCRs, the most common are reduced neo-rhinostomy dimension, cicatricial closure, fibrosis, intra-nasal synechia, and concomitant sino-nasal pathologies (e.g., nasal septal deviation or middle concha bullosa) that were not treated during the primary approach. 19 For these reasons, the approach to a failed DCR can be challenging and either an external or endoscopic approach can be used. Nevertheless, given the prevalence of intra-nasal etiologies of DCR failure and the avoidance of another cutaneous incision, the consensus that an endoscopic approach should be preferred in cases of recurrence is increasing: in fact, the use of endonasal optic instrumentation allows direct visualization of the cause of failure and the concomitant possibility to treat it selectively.20,21 Moreover, several mini-invasive endoscopic approaches have been recently described with encouraging results and reduced intra-operative surgical insult, which possibly allows their application, in selected patients, in local anesthesia.22–24 As a result, in absence of prospective comparative data between EXT-DCR and END-DCR in revision surgeries, the application of an endoscopic approach seems to be, according to the literature, the decision of choice.

In cases of primary surgery, additional factors should be considered before deciding whether an endoscopic or external DCR should be performed.

General vs local anesthesia

When the type of etiology and surgery has been defined, it is essential to evaluate the general status of the patient with DALO and eligibility for general anesthesia. Indeed, if it is true that a surgical approach with an unconscious patient is easier to perform, local anesthesia can be considered in selective patients. 7 In particular, pharmacological innovations have now rendered general anesthesia (GA) the approach of choice thanks to several advantages such as optimal surgical condition and alleviation of the patient's anxiety and pain, especially during periosteal elevation and osteotomies.25,26 Nevertheless, in several cases, the presence of significant systemic comorbidities might jeopardize the possibility of GA, thus justifying the use of local anesthesia: in this case, several advantages can be noted such as reduction of surgical time, nausea, and vomiting as well as reduced intra-operative bleeding and hospitalization, with significant decreases in procedural costs with almost no influence on the final procedural outcome.27,28 In this regard, a recent meta-analysis that compared END-DCR performed with general and local anesthesia demonstrated that even in cases where powered instruments were used the procedure in local anesthesia provided good functional success rates, that seems to be slightly different to GA (p = 0.048): however, due to the low number of available publications, no conclusive statements were made. 29

On the other hand, local anesthesia, particularly during an endoscopic approach, can cause several adverse events such as perforation of the eyeball, retro-orbital bleeding, damage to the optical nerve, burning of nasal fossa due to peri-procedural application of diathermy during oxygen supply, and discomfort of trickling blood into the throat, which can be occasionally dangerous in patients with altered sensorium secondary to sedation. 29 In addition, in uncollaborative patients operated with END-DCR in local anesthesia, there is the risk of difficult visualization of the surgical field through the endoscopic instrumentations, thus undermining the final outcome.25,26,30

For all the above-mentioned reasons, given the wider surgical field through an external approach, which is helpful in uncollaborative subjects, greater historical experience, and no influence on the final success rate, EXT-DCR should be considered the surgical approach of choice in the treatment of DALO in local anesthesia, even if no definitive data has been provided.

Presence of concomitant sino-nasal pathologies

As mentioned, the study of nasal fossae and sinuses is an essential part of pre-operative work-up since the presence of sino-nasal abnormalities is not always associated with nasal symptoms (e.g., concha bullosa of the middle turbinate) and could compromise the final success rate of the DCR. In particular, pre-operative nasal endoscopy eventually associated with radiological examination (e.g., CT maxilla-facial) is the mainstay of ENT pre-operative work-up since it allows direct and precise visualization of sino-nasal pathologies.14,20 Several studies have pointed out that the presence of nasal comorbidities has a more negative influence on EXT-DCR than END-DCR, since in the latter approach it is possible to directly visualize local abnormalities through endoscopic instrumentation, which is not feasible through an external approach. 31 In addition, as already pointed out, the endoscopic approach allows potential concomitant treatment of nasal pathologies during DCR so that a common consensus favors END-DCR compared to an external approach in these cases.20,31 Nevertheless, particular conditions, e.g., antero-superior deviation of the nasal septum, which commonly do not cause nasal obstruction, may justify the choice of EXT-DCR. In fact, even if its concomitant surgical treatment is feasible through an endoscopic approach, in the case of a non-skilled endoscopist ENT-surgeon, the risk of peri-operative complications and increase in surgical time is considerable, so that EXT-DCR should be preferred in this particular situation. 32

Patient age

In past years, an age ≥65 years was considered a criterion of choice for EXT-DCR due to supposedly better outcomes in this category of patients. However, the age of the patient is not always indicative of severe general comorbidities, and a recent study has demonstrated the reliability of END-DCR with general anesthesia in the elderly. Specifically, in a group of patients aged between 65 and 80 years and older than 80 years, the END-DCR success rate was comparable to patients younger than 65 years, such that the endoscopic procedure should be considered equally efficacious to EXT-DCR in this particular category of patients. 33

END-DCR is commonly described to have advantages, compared to EXT-DCR, such as the absence of external scar, less surgical time, earlier recovery, and fewer post-operative complications. 7 On the other hand, the cost of endoscopic instrumentation, marked learning curve, necessity of two specialists (one otolaryngologist and one ophthalmologist) or one highly trained, and the impossibility of concomitant treatment of proximal lacrimal pathologies, have limited use of an endoscopic approach in past decades. 9

Concerning the external scar, which for many is the most critical aspect of an external approach, a case-series analysis of our group of 245 single-surgeon EXT-DCR, 9 demonstrated that patient satisfaction concerning the visibility of the surgical scar is 91.8%, with no unesthetic scars described. These results are an exception in the literature because, in most reports, scar visibility varies from 2.6 to 10.5% of cosmetically important scars and from 4 to 47% of slightly visible scars.34–36 Nevertheless, some authors have shown that scar satisfaction may not necessarily associate with an objective outcome and no established method for self-evaluation of the external scar is available, making the assessment of this issue challenging. 9 In addition, several authors have pointed out that modification of face cosmesis is particularly critical in the case of a flat nasal bridge or in a young patient with dark skin.37,38 As a consequence of our results and the literature, the presence of an external scar should not be taken as the only guiding principle when deciding the surgical approach for the individual patient. This can be considered especially true for the elderly, whereas, for younger or highly pigmented patients with a tendency to keloid formation, a primary END-DCR may be preferred.4,9

Regardless of the abovementioned considerations, the final choice of the surgical approach should be left to the patient.

Whether an endoscopic or external approach is chosen, in both primary and revision cases, several studies found no significant benefit on the final outcome of DCR when using bicanalicular stenting or application of local mitomycin C.39–42 Lacrimal stenting, in particular, is controversial: some authors suggested its benefit in the maintenace of the patency of neo-rhinostomy, while others reported an increase in granulations and infections.10,43–45 Moreover, recent meta-analyses have pointed out that no post-surgical medical therapies, i.e., anti-inflammatory agents or antibiotics, influence the final results of DCR, and their administration should be based on intra-operatory findings of inflammation and infection.10,46

Finally, controversy is still present regarding the correct follow-up needed for DCR for a non-oncologic DALO. It seems reasonable that this should be a minimum of 6 months for primary surgery and up to 18 months for revision surgery. 47

Discussion

The present review summarizes the evidence available regarding the choice of proper surgical technique of DCR in DALO patients with specific conditions. To the authors’ knowledge, this investigation is the first attempt to create a reliable, simple, and reproduceable treatment algorithm for non-oncologic DALO.

The present work advises that, even if END-DCR and EXT-DCR are the mainstay of management for DALO, several factors should be taken into account.7,8,10 In particular, even if general anesthesia should be preferred, important comorbidities may suggest use of local anesthesia. 25 In this case, EXT-DCR should be preferred for its higher safety and experience in non-intubated patients. The endoscopic approach, instead, should be preferred when other sinonasal pathologies worthy of surgical treatment are identified. In this regard, it must be highlighted that the most common cause of failure for DCR is sinonasal abnormalities 19 ; for this reason, and for the possibility to directly visualize the closed neorhinostomy and identify treatment for the specific cause of failure, END-DCR should be preferred for revision surgeries.

Moreover, older age should not determine, by itself, the indication to EXT-DCR, unless the patient's comorbidities are such as to suggest local anesthesia. 33 The fear of a visible facial scar, however, should be less emphasized in the elderly and patients with non-pigmented skin, since the percentage of unesthetic scars in this group is extremely low. 9

Concerning the limits of the present review, the main ones are ascribable to the nature of the studies found in the literature, which are primarily unblinded and non-randomized, and sub-analyses for specific individual conditions (i.e., nasal anatomical abnormalities) have not been performed; in addition, the heterogeneity in pre- and post-surgical management, the device used, and the therapy prescribed may limit the generalizability of the results.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions: A. Vinciguerra, A. Giordano Resti and A. Rampi made substantial contributions to conception, design and acquisition of data, drafted the article and revised it critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved; M. Trimarchi, F. Bandello and M. Bussi made substantial contributions to conception of the data, revised it critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Andrea Rampi https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4952-5348

Francesco Bandello https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3238-9682

Matteo Trimarchi https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6472-3484

References

- 1.Athanasiov PA, Prabhakaran VC, Mannor G, et al. Transcanalicular approach to adult lacrimal duct obstruction: a review of instruments and methods. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina 2009; 40: 149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramberg I, Toft PB, Heegaard S. Carcinomas of the lacrimal drainage system. Surv Ophthalmol 2020; 65: 691–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vinciguerra A, Rampi A, Giordano Resti A, et al. Melanoma of the lacrimal drainage system: a systematic review. Head Neck 2021; 43: 2240–2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trimarchi M, Giordano Resti A, Vinciguerra A, et al. Dacryocystorhinostomy: evolution of endoscopic techniques after 498 cases. Eur J Ophthalmol 2020; 30: 998–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sobel RK, Aakalu VK, Wladis EJ, et al. A comparison of endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy and external dacryocystorhinostomy a report by the American academy of ophthalmology. Ophthalmology 2019; 126: 1580–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang J, Malek J, Chin D, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis on outcomes for endoscopic versus external dacryocystorhinostomy. Orbit 2014; 33: 81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vinciguerra A, Nonis A, Giordano Resti A, et al. Best treatments available for distal acquired lacrimal obstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Otolaryngol 2020; 45: 545–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vinciguerra A, Nonis A, Resti AG, et al. Influence of surgical techniques on endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol–Head Neck Surg 2021; 165: 14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giordano Resti A, Vinciguerra A, Bordato A, et al. The importance of clinical presentation on long-term outcomes of external dacryocystorhinostomies: our experience on 245 cases. Eur J Ophthalmol. Epub ahead of print 2021. DOI:112067212110597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vinciguerra A, Nonis A, Resti AG, et al. Impact of post-surgical therapies on endoscopic and external dacryocystorhinostomy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2020; 34: 846–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munk PL, Lin DT, Morris DC. Epiphora: treatment by means of dacryocystoplasty with balloon dilation of the nasolacrimal drainage apparatus. Radiology 1990; 177: 687–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 2014; 89: 1245–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trimarchi M, Vinciguerra A, Resti AG, et al. Multidisciplinary approach to lacrimal system diseases | Approccio multidisciplinare alle patologie del sistema lacrimale. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2021; 41: 102–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lefebvre DR, Freitag SK. Update on imaging of the lacrimal drainage system. Semin Ophthalmol 2012; 27: 175–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woog JJ. The incidence of symptomatic acquired lacrimal outflow obstruction among residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976–2000 (an American Ophthalmological Society thesis). Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 2007; 105: 649–666. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ali MJ, Paulsen F. Etiopathogenesis of primary acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction: what we know and what we need to know. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2019; 35: 426–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krishna Y, Coupland SE. Lacrimal sac tumors--a review. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2017; 6: 173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanweer F, Mahkamova K, Harkness P. Nasolacrimal duct tumours in the era of endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy: literature review. J Laryngol Otol 2013; 127: 670–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yarmohammadi ME, Ghasemi H, Jafari F, et al. Teamwork endoscopic endonasal surgery in failed external dacryocystorhinostomy. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2016; 11: 282–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gopinathan Nair A, Singh S, Kamal S, et al. The importance of endoscopy in lacrimal surgery. Expert Rev Ophthalmol 2018; 13: 257–265. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altin Ekin M, Karadeniz Ugurlu S, Aytogan H, et al. Failure in revision dacryocystorhinostomy: a study of surgical technique and etiology. J Craniofac Surg 2020; 31: 193–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vinciguerra A, Indelicato P, Giordano Resti A, et al. Long-term results of a balloon-assisted endoscopic approach in failed dacryocystorhinostomies. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. Epub ahead of print 2021. DOI: 10.1007/s00405-021-06975-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park J, Kim H. Office-based endoscopic revision using a microdebrider for failed endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2016; 273: 4329–4334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Indelicato P, Vinciguerra A, Giordano Resti A, et al. Endoscopic endonasal balloon-dacryoplasty in failed dacryocystorhinostomy. Eur J Ophthalmol 2020; 31: 112067212094269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riad W, Chaudhry IA. Anaesthesia for dacryocystorhinostomy. Current Anaesthesia & Critical Care 2010; 21: 180–183. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harissi-Dagher M, Boulos P, Hardy I, et al. Comparison of anesthetic and surgical outcomes of dacryocystorhinostomy using loco-regional versus general anesthesia. Digit J Ophthalmol 2008; 14: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howden J, McCluskey P, O’Sullivan G, et al. Assisted local anaesthesia for endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2007; 35: 256–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McElnea EM, Smyth A, Dutton AE, et al. Assisted local anaesthesia for endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2020; 48: 841–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vinciguerra A, Nonis A, Giordano Resti A, et al. Role of anaesthesia in endoscopic and external dacryocystorhinostomy: a meta-analysis of 3282 cases. Eur J Ophthalmol. Epub ahead of print 2021. DOI: 10.1177/11206721211035616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McNab AA, Simmie RJ. Effectiveness of local anaesthesia for external dacryocystorhinostomy. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2002; 30: 270–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin GC, Brook CD, Hatton MP, et al. Causes of dacryocystorhinostomy failure: external versus endoscopic approach. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2017; 31: 181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim S-W, Yeo SC, Joo Y-H, et al. Limited endoscopic high septoplasty prior to endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy: our experience of nine cases. Clin Otolaryngol 2017; 42: 1363–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tessler I, Warman M, Amos I, et al. Endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy among the old and oldest-old populations – a case control study. Auris Nasus Larynx 2021; 48: 898–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma V, Martin PA, Benger R, et al. Evaluation of the cosmetic significance of external dacryocystorhinostomy scars. Am J Ophthalmol 2005; 140: 359.e1–359.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Devoto MH, Zaffaroni MC, Bernardini FP, et al. Postoperative evaluation of skin incision in external dacryocystorhinostomy. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2004; 20: 358–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tarbet KJ, Custer PL. External dacryocystorhinostomy. Surgical success, patient satisfaction, and economic cost. Ophthalmology 1995; 102: 1065–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duffy MT. Advances in lacrimal surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2000; 11: 352–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ali M, Naik M, Honavar S. External dacryocystorhinostomy: tips and tricks. Oman J Ophthalmol 2012; 5: 191–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kang MG, Shim WS, Shin DK, et al. A systematic review of benefit of silicone intubation in endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol 2018; 11: 81–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ing EB, Bedi H, Hussain A, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in dacryocystorhinostomy with and without silicone intubation. Can J Ophthalmol 2018; 53: 466–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phelps PO, Abariga SA, Cowling BJ, et al. Antimetabolites as an adjunct to dacryocystorhinostomy for nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4. Epub ahead of print April 7, 2020. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD012309.PUB2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sousa TTS, Schellini SA, Meneghim RLFS, et al. Intra-operative mitomycin-C as adjuvant therapy in external and endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmol Ther 2020; 9: 305–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meduri A, Inferrera L, Tumminello G, et al. Surgical treatment of dacryocystitis by using a venous catheter. J Craniofac Surg 2020; 31: 1120–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meduri A, Inferrera L, Tumminello G, et al. The application of a venous catheter for the surgical treatment of punctal occlusion. J Craniofac Surg 2020; 31: 1829–1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meduri A, Tumminello G, Oliverio GW, et al. Use of lacrimal symptoms questionnaire after punctoplasty surgery: retrospective data of technical strategy. J Craniofac Surg 2021; 32: 2848–2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yim M, Wormald PJ, Doucet M, et al. Adjunctive techniques to dacryocystorhinostomy: an evidence-based review with recommendations. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2021; 11: 885–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Allon R, Cohen O, Bavnik Y, et al. Long-term outcomes for revision endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy-the effect of the primary approach. Laryngoscope 2021; 131: E682–E688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]