Abstract

The major outer membrane protein (MOMP), a putative porin and a multifunction surface protein of Campylobacter jejuni, may play an important role in the adaptation of the organism to various host environments. To begin to dissect the biological functions and antigenic features of this protein, the gene (designated cmp) encoding MOMP was identified and characterized from 22 strains of C. jejuni and one strain of C. coli. It was shown that the single-copy cmp locus encoded a protein with characteristics of bacterial outer membrane proteins. Prediction from deduced amino acid sequences suggested that each MOMP subunit consisted of 18 β-strands connected by short periplasmic turns and long irregular external loops. Alignment of the amino acid sequences of MOMP from different strains indicated that there were seven localized variable regions dispersed among highly conserved sequences. The variable regions were located in the putative external loop structures, while the predicted β-strands were formed by conserved sequences. The sequence homology of cmp appeared to reflect the phylogenetic proximity of C. jejuni strains, since strains with identical cmp sequences had indistinguishable or closely related macrorestriction fragment patterns. Using recombinant MOMP and antibodies recognizing linear or conformational epitopes of the protein, it was demonstrated that the surface-exposed epitopes of MOMP were predominantly conformational in nature. These findings are instrumental in the design of MOMP-based diagnostic tools and vaccines.

Many gram-negative bacteria have one or more predominant outer membrane proteins (OMPs). These major OMPs (MOMPs) possess unique structural features and usually function as general or specific porins regulating the permeability of the membrane to small molecules (8, 9, 18, 36). Hence, the pore-forming molecules play an important role in the communication between bacteria and the environment. Structurally, a typical porin subunit consists of 16 to 18 β-strands forming an antiparallel β-barrel, with short turns located at the bottom of the barrel facing the periplasmic space and long loops located at the top end of the barrel facing the external surface of bacterial membrane (8, 9, 36, 42, 48). Three porin subunits are assembled into a stable homotrimer, which is highly resistant to detergent and protease, a key property required for enteric organisms to survive in the intestinal tract (8, 9). Experimentally, porins can be identified by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in three different conformational forms including the folded monomer, the denatured monomer, and the native trimer. Notably, different bacterial porins are remarkably similar in their β-barrel structure, although their primary sequences have little homology (8, 12, 18, 36). As the major components of the gram-negative bacterial outer membrane, pore-forming proteins also play a role in bacterial pathogenesis, such as adherence, invasion, and serum resistance (35, 44–46). Porin-based vaccines can induce protective immunity against some bacterial infections (39, 49).

Camylobacter jejuni is the leading bacterial cause of human enteritis in many industrialized countries (20, 41). This pathogenic organism causes watery diarrhea and/or hemorrhagic colitis and is also associated with Guillain-Barré syndrome, an acute flaccid paralysis that may lead to respiratory muscle compromise and death (31, 40). The majority of human C. jejuni infections are epidemiologically linked to ingestion of contaminated food or water (20, 41). Despite the recent advances in our understanding of the pathobiology of C. jejuni, the molecular genetic mechanisms by which C. jejuni colonizes and adapts to various host or environmental conditions are still poorly understood. As with other pathogenic organisms, membrane surface molecules of C. jejuni are considered the major mediators of the pathogen-host interactions. The OMP profile of thermophilic Campylobacter species (including C. jejuni and C. coli) is characterized by the presence of a single major protein (5, 25). As estimated by denaturing SDS-PAGE, this MOMP of C. jejuni has a molecular mass of 40 to 48 kDa in different strains (5, 16). Expression of MOMP seems stable under a variety of growth, incubation, and passage conditions (5). Based on its biochemical and structural features, MOMP has been characterized as a member of the trimeric bacterial porin superfamily (7, 16). Purified MOMP from C. jejuni has pore-forming activity when reconstituted in lipid bilayers (10, 51). Similar to other gram-negative bacterial porins, MOMP exhibits heat modifiability and can be identified in three conformational forms including the folded monomer (∼35 kDa), the denatured monomer (40 to 48 kDa), and the native trimer (120 to 140 kDa) (16). The trimeric form of MOMP has been observed on the membrane surface of Campylobacter cells (1, 2) and is less stable than the porin trimers of Escherichia coli (7).

In addition to being a porin, MOMP may have functions distinct from its pore-forming activity. Purified MOMP bound to isolated membranes of the INT 407 cell membrane and partially inhibited the attachment of C. jejuni, suggesting that MOMP might be involved in the adherence of C. jejuni to host cells (30, 37). The binding was apparently dependent on the conformation of MOMP, since the activity was observed only with MOMP purified under native conditions, not with MOMP purified with SDS. In a recent study by Bacon et al.(3), a cytotoxic complex composed of MOMP and lipopolysaccharide was identified and characterized from a clinical isolate of C. jejuni. Since the cytotoxic preparation contained lipopolysaccharide, it was difficult to determine the actual component responsible for the observed cytotoxicity. MOMP was also speculated to be involved in the general resistance of C. jejuni to many hydrophilic antibiotics (33). These observations suggest that MOMP may have additional biological functions contributing to the adaptation of the pathogenic organism to various host environments.

Despite the apparent importance of MOMP as a predominant membrane protein of C. jejuni, its genetic, structural, and immunological characteristics have not been well defined. Elucidation of these features of MOMP is crucial for our understanding of the role of MOMP in C. jejuni infection and will also facilitate the design of MOMP-based diagnostics or vaccines. Toward this end, we initiated studies to characterize MOMP at the molecular genetic levels. To distinguish MOMP from other known bacterial OMPs, the gene encoding MOMP is designated cmp (for ‘Campylobacter major protein’) in this paper. In this study, we determined the sequence polymorphism of cmp from multiple strains of C. jejuni and C. coli, proposed a two-dimensional structural model for MOMP based on the sequence information, established the procedures for production and purification of recombinant MOMP, and demonstrated the conformational nature of surface-exposed MOMP epitopes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The Campylobacter strains used in this study and their sources are listed in Table 1. Bacterial cultures were grown in brucella broth or on Mueller-Hinton agar at 42°C under microaerophilic conditions.

TABLE 1.

Campylobacter strains used in this study

| Strain | Source and reference |

|---|---|

| C. jejuni | |

| 33291 | Human (ATCC)a |

| 81176 | Human (4) |

| S9801 | Humanb |

| X77136 | Humanc |

| T37597b | Humanc |

| M36292 | Humanc |

| M50813 | Humanc |

| H49024 | Humanc |

| X77852 | Humanc |

| S13530 | Humanc |

| X7199 | Humanc |

| E46972 | Humanc |

| H30769 | Humanc |

| S47648 | Humanc |

| 15046764 | Bovined |

| 1979855 | Canined |

| 19084571 | Ovined |

| 19094451 | Ovined |

| S2b | Chickene |

| S1lb | Chickene |

| Turk | Turkey (23) |

| 21190 | Chicken (23) |

| C. coli | |

| 33559 | Pig (ATCC) |

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.

A fresh clinical isolate from a patient with diarrhea in Wooster Community Hospital, Wooster, Ohio.

Fresh clinical isolates derived from individual patients in 1999 and 2000 and obtained from the Microbiology Laboratory of the Ohio State University Hospital, Columbus, Ohio.

Provided by David Wilson, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Mich.

Isolated from chicken rinses by this laboratory in 1998.

PCR.

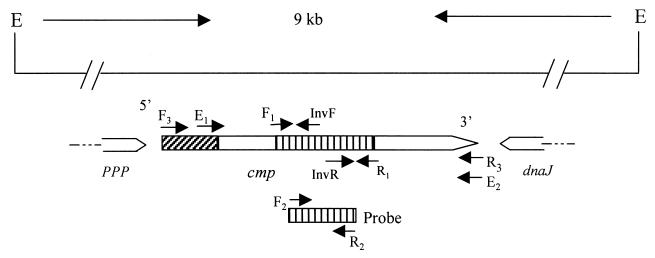

PCR was performed in a volume of 100 μl containing 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 200 nM primers, 2.5 mM MgSO4, 100 ng of Campylobacter genomic DNA, and 5 U of Taq DNA polymerase or Pfu polymerase (Promega). Cycling conditions varied according to the estimated annealing temperatures of the primers and the expected sizes of the products. The locations of the key primers used in this study are indicated in Fig. 1. PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. To amplify the long DNA template, the Expand Long Template PCR system (Boehringer Mannheim) was used as specified by the manufacturer. PCR products were purified with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) prior to sequencing. PCR products were cloned into E. coli with the pGEM-T Easy cloning vector (Promega) by following the procedure included with the cloning kit.

FIG. 1.

Genomic organization and partial features of the cmp gene in C. jejuni strain 33291. The line at the top shows the 9-kb genomic fragment flanked by EcoRV (E). The location and direction of identified ORFs are indicated by boxed arrows below the line. The shaded box at the 5′ end of cmp indicates a signal sequence, while the shaded region in the middle of cmp denotes the sequence amplified by the degenerate primers designed from known peptide sequences. The locations of the key primers used in this study are labeled with arrows along the ORF of cmp. The shaded box below cmp indicates the location of the DNA probe in relation to the cmp ORF. The sequences of ppp (phosphotyrosine protein phosphatase) and dnaJ are partially determined.

Sequence analysis and prediction of secondary structures.

PCR products and plasmids were sequenced using an automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems model 377). Alignment of MOMP sequences was performed with the Pileup program in the Genetics Computer Group (GCG) sequence analysis software package (Oxford Molecular), and the aligned sequences were shaded with BoxShade (www.ch.embnet.org/software/BOX_form.html). The frequency of mutation at each amino acid position was calculated with PsFind (29), using the aligned sequences. Hydropathy profiles and charge properties of MOMP were analyzed with the GCG package. To construct a dendrogram based on the aligned MOMP sequences, a distance matrix was created with the Distances program in GCG and a dendrogram was then plotted using the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) procedure of the Growtrees program in GCG. For predicting the secondary structures of MOMP, the Peptidestructure program in GCG was used for initial prediction. By reference to known characteristics of bacterial porins, the initial prediction was further modified and refined by considering the following assumptions (8, 9, 18, 35): transmembrane β-strands were predominantly amphipathic and were located in highly conserved regions; periplasmic turns were generally short and contained turn promoters (Asp, Asn, Glu, Gly, Pro, and Ser); and external loops were generally long and were associated with variable sequences.

DNA probe labeling and Southern hybridization.

cmp-specific primers (F2 [5′-CTTCAGTGCTGCTATAGCTG-3′] and R2 [5′-GCTCTGCAGCCATGAAGCT-3′] (Fig. 1) and the digoxiginin-11-dUTP (DIG) labeling kit (Boehringer Mannheim) were used in PCR to produce a nonradioactive DNA probe specific for cmp. The labeling procedure was described previously (50). For Southern hybridization, C. jeuni genomic DNA was completely digested with EcoRV, transferred to nylon membrane, hybridized with the DIG-labeled probe, and detected with the chemiluminescent substrate CDP-Star as specified by the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim).

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

SDS-PAGE was performed by the method of Laemmli (22) with a 10% polyacrylamide separating gel. Proteins were treated in sample buffer at 25 or 100°C for 5 min under reducing conditions prior to electrophoresis. To reveal the trimeric form of MOMP, a low concentration of SDS (0.01%) was used in the SDS-PAGE system as described by Bolla et al. (7). Proteins separated by SDS-PAGE were visualized by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250. For immunoblotting, the proteins were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Then the membrane filters were incubated with blocking buffer (2% milk in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] containing 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h at 25°C. Primary antibodies (rabbit anti-MOMP) were diluted in the blocking buffer and applied to the membrane blots. After incubation at 25°C for 2 h, the blots were washed with PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated to horseradish peroxidase [Kirkegaard & Perry]) at 25°C for 2 h. After being washed the blots were developed with the 4 CN membrane peroxidase substrate system (Kirkegaard & Perry). In some immunoblotting experiments involving recombinant MOMP (rMOMP), a zwitterionic detergent, Empigen BB (Calbiochem-Novabiochem) was added to a final concentration of 0.15% in the dilution buffer of the primary antibody to restore the reactivity of denatured rMOMP to antibodies recognizing conformational epitopes. This detergent has been widely used to restore the reactivity of blotted bacterial membrane proteins to various antibodies (17, 27, 47).

For colony immunoblotting, C. jejuni strain 33291 was grown on Mueller-Hinton agar for 48 h. Fresh colonies were transferred onto PROTRAN nitrocellulose filters (Schleicher & Schuell) by placing a filter on top of each plate. The filters were lifted from the plates and directly submerged in blocking buffer (PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin and 2% milk). After being subjected to blocking at 25°C for 1 h, the filters were sequentially incubated with primary antibodies (rabbit anti-MOMP) and secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated to horseradish peroxidase). Every incubation step was performed at 25°C for 2 h. Washing between steps was performed with PBS. Detection was performed with the 4 CN membrane peroxidase substrate system.

Production of antibodies to different conformational forms of MOMP.

OMPs of C. jejuni were extracted as described by Blaser et. al. (5). A procedure described by Harlow and Lane (15) was adapted to produce antibodies to different conformational forms of MOMP in rabbits. The OMPs of C. jejuni 33291 were treated in sample buffer at 25°C (for generating the 35-kDa folded monomer of MOMP) or 100°C (for generating the 45-kDa denatured monomer of MOMP) and separated by SDS-PAGE. Each form of MOMP was excised from the gels. The MOMP band containing approximately 100 μg of the protein was homogenized in PBS to form 1 ml of gel suspension. The gel suspension was then emulsified with 1 ml of incomplete Freund's adjuvant and injected into two New Zealand White rabbits (50 μg of protein/rabbit). Each rabbit received three subcutaneous injections at 2-week intervals. The rabbits were bled 21 days after the last injection. Pre- and postimmunization serum samples were analyzed by immunoblotting using OMPs of C. jejuni 33291. The immunized rabbits produced specific antibodies to MOMP, while the preimmune sera were negative with MOMP (data not shown). The antibody to the denatured monomer of MOMP was designated A-5, while the antibody to the folded monomer was designated A-8.

Expression of cmp in E. coli.

rMOMP was produced in E. coli using the pQE-30 vector in the QIAexpress expression system (Qiagen). To amplify the DNA sequence encoding the entire length of mature MOMP in strain 33291 primers E1 (5′-ATGGATCCACTCCACTTGAAGAAGCG-3′) and E2 (5′-CAGGTACCGAAGTTAGAC TTGAAAGCT-3′) (Fig. 1) were designed from the obtained sequence of cmp of strain 33291 (cmp33291). A restriction site (underlined in the primer sequences) was attached to the 5′ end of each primer to facilitate the insertion of the amplified PCR product into the pQE-30 vector. These two primers plus Pfu DNA polymerase (Promega) and genomic DNA of C. jejuni 33291 were used in PCR to amplify the sequence encoding mature MOMP33291. The amplified PCR product was digested with BamHI and KpnI and then purified by using the QIAquick PCR cleaning kit (Qiagen). The pQE-30 vector was also digested with BamHI and KpnI and then purified by gel extraction. The digested pQE-30 vector and PCR products were ligated with T4 DNA ligase. This recombinant plasmid contained the sequence encoding the mature MOMP333291 with a His6 tag at the N terminus. Transformation screening for positive recombinants, production, and purification of rMOMP were performed by following the procedures supplied with the pQE-30 vector. The plasmid in the E. coli clone expressing rMOMP33291 was fully sequenced, revealing no mutations in the coding sequence. rMOMP was purified under denaturing conditions with 8 M urea by following the procedure supplied with the pQE-30 vector. rMOMP was purified under native conditions by following the protocol supplied with the pQE-30 vector, with the addition of 3% Empigen BB to the lysis buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate [pH 8.0], 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole), 1% Empigen BB to the wash buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate [pH 8.0], 300 mM NaCl, 60 mM imidazole), and 1% Empigen BB in the elution buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate [pH 8.0], 300 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole). The purified rMOMPs were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. To remove Empigen BB or urea from rMOMP, the purified proteins were washed extensively with PBS using Centricon YM-30 (Millipore).

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis of the macrorestriction fragment patterns of C. jejuni genomic DNA was performed by a procedure published elsewhere (13, 14). Briefly, flesh cultures of C. jejuni grown in brucella broth were embedded in chromosomal grade agarose (Bio-Rad) and treated with lysis buffer (0.25 M EDTA, 0.5% n-lauroylsarcosine, 1 mg of proteinase K per ml) at 50 °C overnight. After being washed, the gel plugs were digested with SmaI, SalI, or KpnI under conditions optimal for the restriction enzymes. DNA fragments were separated in pulsed-field-certified agarose (1%) with 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer at 14°C using a CHEF Mapper system (Bio-Rad). The electrophoresis conditions were optimized by using the embedded autoalgorithm in the CHEF Mapper. After separation, the gels were stained with ethidium bromide and photographed.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The MOMP gene sequences determined in this study were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AF285122 to AF285144.

RESULTS

Identification of cmp33291.

When the study was initiated, no cmp DNA sequences were available in the GenBank databases. However, partial amino acid sequences of MOMP had been determined by Schroder and Moser (37). From the published peptide sequences of MOMP (37), degenerate primers F1 (5′-TAYGAYACNGGNAAYTTYGAYAA-3′) and R1 (5′-ARAARAANGCNACYTGRTCCCA-3′) were designed from the corresponding peptide sequences, YDTGNFDK and WDQVAFFY, respectively. This pair of degenerate primers amplified two products from the chromosomal DNA of strain 33291, of 530 and 800 bp. Both of the PCR products were cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector and subsequently sequenced. The 530-bp product was determined to be a part of the cmp gene because it contained an open reading frame (ORF) whose deduced amino acid sequences matched the known peptide sequences of MOMP (37). The other (800-bp) product contained an ORF not related to cmp, implying that it was amplified by nonspecific priming due to the degeneracy of the primers and the low annealing temperature (40°C) used for the PCR. From the MOMP-encoding 530-bp sequence, cmp-specific primers (F2 and R2 [Fig. 1]) were designed and used to produce a DIG-labeled DNA probe. Hybridization of this probe to genomic DNA of strain 33291 revealed that cmp33291 existed on a single 9-kb EcoRV fragment (Fig. 1). To identify the full cmp gene and its flanking sequences, an inverse PCR protocol was adopted to amplify the 9-kb genomic fragment. For this purpose, the genomic DNA of strain 33291 was completely digested with EcoRV and religated with T4 DNA ligase to form a circular template. Two inverse primers (InvF [5′-AGCTTCATGGCTGCAGAGC-3′] and InvR [5′-CAGCTATAGCAGCACTGAAG-3′] (Fig. 1), the circular template, and the Expand Long Template PCR kit were successfully used to amplify the 9-kb DNA fragment from strain 33291. The amplified product was purified and partially sequenced by primer walking. After the full ORF of cmp33291 was obtained, two primers flanking the gene were designed for regular PCR to amplify the whole cmp ORF from the intact genomic DNA of strain 33291. The amplified product was again sequenced and confirmed the cmp33291 sequence obtained by the inverse PCR.

Features of cmp333291 and its encoded product.

cmp33291 contained an ORF of 1,275 bp encoding 425 amino acids. The G+C content of cmp33291 was 37%, slightly higher than the overall 30% G+C content of the Campylobacter genome (34). A potential ribosome-binding site occurred 12 nucleotides upstream of the proposed ATG start codon. A putative Rho-independent terminator occurred 22 nucleotides downstream of the TAA stop codon. The deduced amino acid sequence of cmp33291 revealed a typical N-terminal signal peptide, consisting of 22 amino acids (Fig. 2). This prediction was consistent with a previous finding obtained by sequencing the N terminus of MOMP (7, 37). The predicted mature MOMP33291 protein consisted of 403 amino acids with a calculated molecular mass of 43.5 kDa, comparable to the size (45 kDa) estimated by SDS-PAGE. MOMP33291 contained a high portion of charged residues and is an overall negatively charged protein, compatible with the marked cationic selectivity of the pores formed by MOMP (10, 33). cmp33291 was found to be highly homologous (97% amino acid identity) to the recently released cmp sequences in strains NCTC 11168 (34) and 2483 (GenBank accession number U96452). Comparison of cmp33291 with the sequences in the GenBank database did not reveal significant homology to genes encoding other known proteins including porins of gram-negative bacteria. No other ORFs were present on the cmp coding strand and the opposite strand. There was an ORF encoding a putative phosphotyrosine protein phosphatase (34) upstream of cmp, while the dnaJ gene (21) was located downstream of cmp on the opposite strand (Fig. 1). The nucleotide distance between the phosphotyrosine protein phosphatase gene and cmp was 251 bp. Although these two genes were transcribed in the same direction, it appeared that they were not cotranscribed, because of the rather large separation and the presence of potential transcription terminators (stem-loop structures) between them.

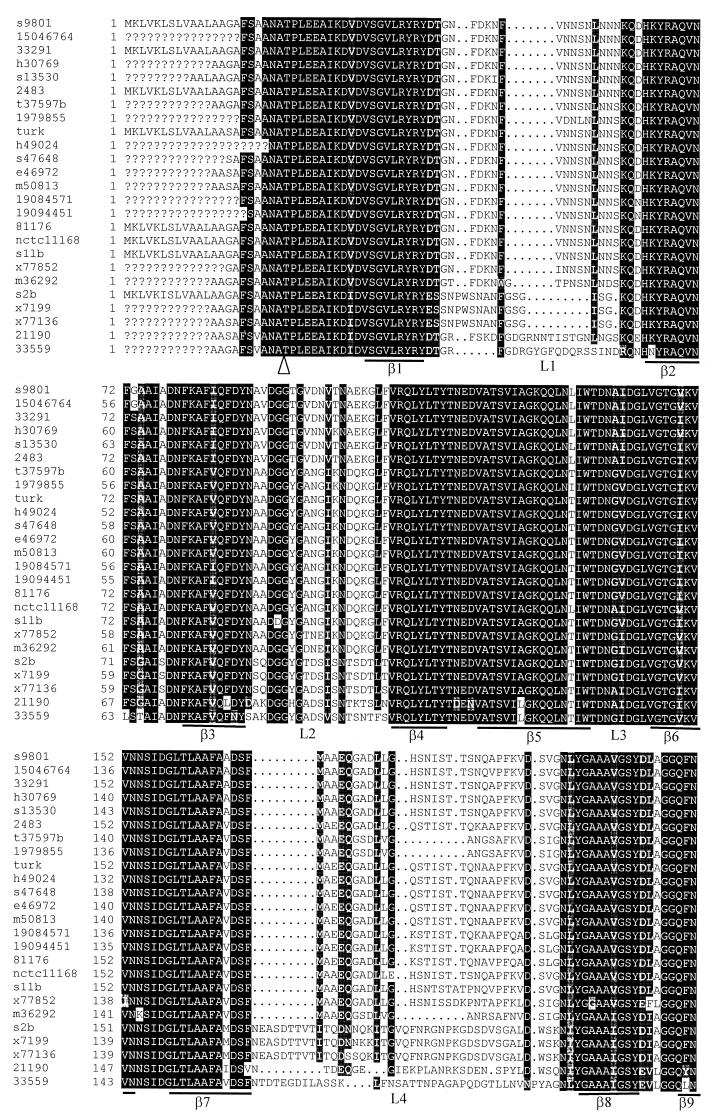

FIG. 2.

Multiple alignments of deduced MOMP sequences and predicted secondary structures of MOMP. Question marks indicate undetermined sequences. Dots represent gaps in the alignments. The regions predicted to form β-strands are underlined and labeled β1 to β18. The putative external loops are marked L1 to L9. The arrowhead indicates the cleavage site for mature MOMP. The names of the strains are labeled on the left of the figure. The numbers indicate the amino acid numbers of MOMP in each strain. The MOMP sequences of strains NCTC 11168 and 2483 were obtained from the GenBank database (accession AL111168 and U96452, respectively).

Sequence divergence and predicted secondary structures of MOMP.

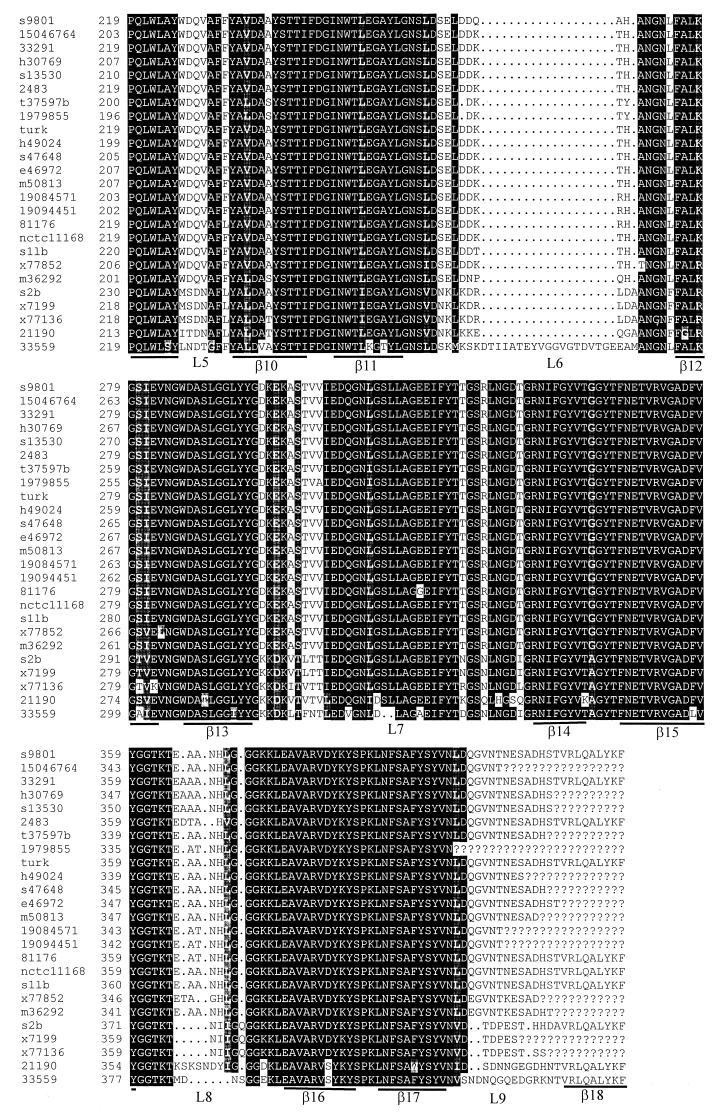

It is known that the size (ranging from 40 to 48 kDa as estimated by denaturing SDS-PAGE) and antigenicity of MOMP may vary in different strains of C. jejuni (5, 6, 19). However, the genetic basis for MOMP heterogeneity has not been determined. To assess if sequence polymorphism exists in cmp, the cmp loci in 22 strains of C. jejuni and one strain of C. coli isolated from various animal species (Table 1) were amplified by PCR and sequenced. Several pairs of primers designed from the coding sequence and flanking regions of cmp33291 were initially used for PCR amplifications. Most primer sets gave products from only some of the tested strains. However, the primer set F3 (5′-ATGAAACTAGTTAAACTTAGTTTA-3′) and R3 (5′-GAATTTGTAAAGAGCTTGAAG), which correspond to the 5′ and 3′ ends of cmp33291 (Fig. 1), consistently yielded the expected product from every strain of C. jejuni and the one strain of C. coli examined in the study, indicating that the DNA sequences at the 5′ and 3′ ends of cmp are highly conserved in the two Campylobacter species. The identified cmp alleles from other strains showed overall features similar to those of cmp33291. No cysteine residue was found in the deduced MOMP sequences obtained in this study, indicating that disulfide cross-linking is unlikely to occur in this protein. This finding was in contrast to a previous observation made by direct determination of the amino acid content of MOMP (7). Sequence alignment of the deduced amino acids of cmp alleles demonstrated that there were five hypervariable (HV1 to HV5) and two semivariable regions dispersed between highly conserved sequences (Fig. 2 and 3). The amino acid differences in MOMP range from 0 to 36% among different strains of C. jejuni. The C. coli MOMP showed less than 70% amino acid homology to any one of the C. jejuni MOMPs and was distinctly distant from all MOMPs of C. jejuni examined in this study (Fig. 2; also see 4). Based on the sequence alignment and other predicted features of the MOMP sequences, the regions forming putative β-strands and external loop structures were identified (Fig. 2). According to this predicted model, a MOMP subunit consisted of 18 β-strands with long loops (L1 to L9) on the external side of the membrane and short turns facing the periplasmic space. The highly conserved regions were predicted to form the β-strands, while the variable regions were located in the putative loop structures (Fig. 2 and 3).

FIG. 3.

Quantitative measurement of sequence variation in each aa position in MOMP. The percent diversity is calculated using the PsFind program(29) from the aligned sequences in Fig. 2. The N-terminal 22 amino acids and the C-terminal 24 amino acids in the alignment are omitted from the calculation because of the unavailability of the terminal sequences in some strains. The arbitrarily designated hypervariable (HV) and semivariable (SV) regions are marked by lines. The variable regions correspond to the predicted external loops L1, L2, L4, L5, L6, L7, and L8, respectively.

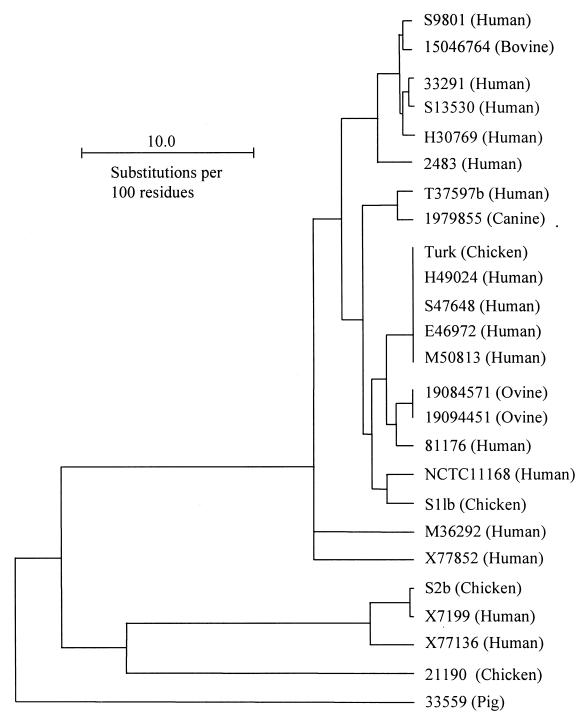

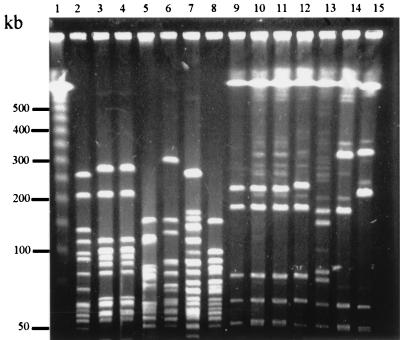

Based on the amino acid sequence homology of MOMP, a dendrogram was constructed to determine the clustering patterns of the Campylobacter strains (Fig. 4). According to this dendrogram, clustering of strains was not associated with the animal species from which the strains were isolated. This observation was consistent with the notion that cross-species transmission of C. jejuni occurs (32, 40, 41). Notably, some strains of C. jejuni possessed an identical (100% homologous) cmp gene (Fig. 2 and 4). To determine if the MOMP-based dendrogram reflected the phylogenetic relationship of the strains, representative strains were further analyzed by PFGE using three restriction enzymes (SalI, SmaI, and KpnI). The macrorestriction profiling demonstrated that strains with identical cmp sequences also had identical or closely related PFGE patterns (partially shown in Fig. 5). For example, the two ovine strains 19084571 and 19094451 had identical SmaI, SalI, and KpnI profiles (data not shown). Similarly, the human isolates H49024, S47648, E46972, and M50813, which had an identical cmp gene (Fig. 4), were indistinguishable by the three restriction enzymes (partially shown in Fig. 5). The poultry isolate Turk had an identical SmaI pattern and different but similar KpnI and SalI profiles with respect to the four human strains with which it clustered (partially shown in Fig. 5). However, strains that have nonidentical cmp sequences showed divergent PFGE patterns (Fig. 4 and 5). These results suggested that cmp sequence homology might reflect the phylogenetic proximity of the strains.

FIG. 4.

MOMP-based dendrogram constructed by the UPMGA method of Growtrees in GCG. The MOMP sequences listed in Fig. 2 were used to create a distance matrix. The names of the Campylobacter strains are shown on the right of the figure, and the sources of isolation for each strain are given in parentheses. The MOMP sequences of strains NCTC11168 and 2483 were obtained from the GenBank database (accession no. AL111168 and U96452, respectively).

FIG. 5.

PFGE analysis of C. jejuni using restriction enzymes KpnI (lanes 2 to 8) and SalI (lanes 9 to 15). Lane 1 contains DNA size markers (λ ladder [Promega]). The strains included in this figure are Turk (lanes 2 and 9), H49024 (lanes 3 and 10), M50813 (lanes 4 and 11), S9801 (lanes 5 and 12), 15046764 (lanes 6 and 13), 33291 (lanes 7 and 14), and S13530 (Lanes 8 and 15). The relationship of these strains as determined by cmp sequence homology is shown in Fig. 4.

Antigenicity of rMOMP33291.

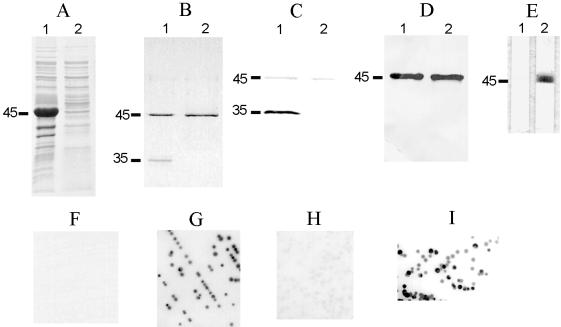

To facilitate the characterization of MOMP, rMOMP33291 was produced in E. coli by using the pQE-30 vector. To minimize the toxic effect on the E. coli host, the signal peptide sequence of MOMP33291 was excluded from the rMOMP. Overexpression of the cmp gene without the signal sequence in E. coli did not impair host cell viability. As determined by SDS-PAGE, the rMOMP was predominantly associated with the cytoplasmic inclusion bodies (Fig. 6A) and there was no apparent size difference between rMOMP33291 produced in E. coli and the authentic MOMP expressed in C. jejuni. rMOMP33291 purified under denaturing conditions (with 8 M urea) migrated as a single band (45 kDa), regardless of the temperatures (25 or 100°C) used to treat the protein sample prior to SDS-PAGE (Fig. 6B). However, rMOMP33291 purified under native conditions (with Empigen BB) migrated as two bands, of −45 and 35 KDa (Fig. 6B). These two bands corresponded to the positions of the denatured monomer and the folded monomer of the authentic C. jejuni MOMP and were the putative denatured monomer and folded monomer of rMOMP33291. Despite the extensive effort to modify the conditions of SDS-PAGE, no bands corresponding to the trimeric forms of MOMP33291 were detected in rMOMP by SDS-PAGE (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Antigenic features of rMOMP33291 and demonstration of surface-exposed conformational epitopes of MOMP. (A) Inclusion bodies (lane 1) and supernatant (lane 2) of sonicated E. coli expressing rMOMP were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue R-250. (B) rMOMP purified with Empigen BB (lane 1) or urea (lane 2) was treated in sample buffer at 25°C and then subjected to SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained with Coomassie blue R-250. (C and D) Replica samples in panel B were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and blotted with antibodies A-8 (C) or A-5 (D). (E) rMOMP33291 purified with urea was immunostained with A-8 in the absence (lane 1) or presence (lane 2) of Empigen BB. The positions of the denatured monomer (45 kDa) and the folded monomer (35 kDa) are indicated on the left of panels A to E. (F to I) Colonies of C. jejuni strain 33291 were immunoblotted with A-5 (F), A-8 (G), A-8 absorbed with rMOMP33291 purified with Empigen (H), or A-8 absorbed with rMOMP33291 purified with urea (I).

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies induced by the denatured monomer of MOMP33291 (A-5) or the folded monomer of MOMP33291 (A-8) were used to analyze the antigenicity of rMOMP33291. As shown in Fig. 6C, A-8 reacted well with the folded form of rMOMP33291 (35 kDa) and weakly with the denatured form of rMOMP33291 (45 kDa). In contrast, A-5 strongly recognized the 45-kDa band but did not react with the 35-kDa band (Fig. 6D). Inclusion in the antibody dilution buffer of the detergent Empigen BB (0.15%), which was used in other studies to restore the native conformation of bacterial membrane proteins (17, 27, 47), substantially increased the reactivity of denatured rMOMP33291 to A-8 (Fig. 6E). The preimmune rabbit sera did not have any reactivity to rMOMP33291. These results confirmed the presence of native rMOMP33291 in Empigen BB-purified preparations and also indicated that immunization of rabbits with two different conformational forms of MOMP33291 yielded antibodies against distinct epitopes (linear or conformational) on the same protein.

Identification of surface-exposed conformational epitopes.

To determine the nature (linear or conformational) of surface-exposed MOMP epitopes, immunoblotting of bacterial colonies with antibodies A-5 and A-8 was performed (Fig. 6F to I). Despite the strong reactivity of A-5 with C. jejuni MOMP33291 on immunoblots (data not shown), this antibody did not react with intact bacterial colonies (Fig. 6F). In contrast, A-8 reacted strongly with colonies of strain 33291 (Fig. 6G). Absorption of A-8 with rMOMP33291 purified under native conditions greatly reduced the reactivity of the antibody with bacterial colonies (Fig. 6H), while absorption with rMOMP33291 purified under denaturing conditions had little effect on the reactivity of the antibody with intact bacterial cells (Fig. 6I). Together, these results indicated that the surface-exposed epitopes of MOMP are predominantly conformational in nature.

DISCUSSION

The identified cmp sequences in this study predicted several features of MOMP that are similar to the known characteristics of gram-negative bacterial porins. These features of MOMP include a typical signal peptide sequence which is cleaved from the mature protein, an abundance of polar residues and amphipathic antiparallel β-strands, the presence of variable sequences corresponding to surface-exposed loops, and the presence of a phenylalanine residue at the C terminus. The C-terminal Phe is highly conserved in bacterial OMPs and plays an important role in the appropriate assembly of membrane proteins (43). The last 9 amino acids (V-R-L-Q-A-L-Y-K-F) at the C termini of MOMPs appeared to be conserved among the strains of Campylobacter, and this conserved sequence is compatible with the consensus sequence identified for bacterial OMPs, with Phe at position 1 and hydrophobic residues at positions 3, 5, 7, and 9 from the C terminus (43). The highly conserved terminal sequences in cmp greatly facilitate the design of PCR primers to amplify the entire ORF of the gene from different strains or even different species.

The predicted secondary structures of MOMP are in agreement with the known characteristic of structurally defined bacterial porins (8, 9, 42). Due to the lack of homology between MOMP and other bacterial porins, it was not feasible to use a template porin sequence with defined structures to develop a homology-based model for MOMP. Despite the difficulty, the alignment of multiple MOMP sequences, the use of multiple prediction methods, and inference from known topological features of porins (see Materials and Methods) should have improved the overall prediction accuracy. This prediction provides a preliminary structural model for further dissecting the structure-function relationship of this important surface protein. Since it is difficult to predict the precise regions forming β-strands from the primary sequence alone, the proposed secondary structures of MOMP should be considered a preliminary model and needs to be confirmed by other experimental means, such as X-ray crystallography.

Seven variable regions dispersed among highly conserved sequences were identified in cmp alleles. It was predicted that the variable regions were located in surface-exposed loops, while the conserved regions encoded β-strands, which are essential for maintaining the β-barrel structure of porin molecules. The sequence divergence of MOMP may have functional consequences. As observed with other bacterial MOMPs (24), the sequence divergence of MOMP may result in antigenic variation of surface-exposed epitopes. Examination of this possibility is important for our understanding of the role of MOMP in the adaptation of C. jejuni to host environments and will require a comprehensive approach involving monoclonal antibodies, rMOMP, and site-directed mutagenesis techniques. It is known that the external loops of porins function as the gate for the pores and control the molecules that pass through the pores (48). Extrapolating from this known feature of bacterial porins, it can be speculated that sequence divergence in the loop structures of MOMPs may also affect the size and charge properties of the pore and consequently modulate the permeability to different molecules. Thus, sequence variation of MOMP may have multiple effects on C. jejuni and may provide flexibility for C. jejuni to adapt in various environments. The high degree of variability in the external loops of MOMP suggests that the loop regions lack structural constraints and are free to vary under selective pressures exerted by host immune systems or other environmental conditions.

It was observed in this study that the strains possessing an identical cmp gene also had indistinguishable or similar PFGE patterns while strains with nonidentical cmp sequences had different PFGE patterns (Fig. 4 and 5). This finding suggests that sequence variation of cmp may be exploited for molecular typing or phylogenetic analysis of C. jejuni. The turkey strain (Turk), which was isolated in California in the early 1990s (23), had an identical cmp gene to that of four human isolates isolated in Ohio (Fig. 4). The four human strains were isolated from individual patients at different times (spanning 5 months) in 1999 and 2000 and were indistinguishable in PFGE analyses with three restriction enzymes. Turk had similar PFGE patterns to the four human strains. These observations suggest that the turkey strain and the four human strains might have originated from the same ancestral clone. Since only a limited number of C. jejuni strains were analyzed in this study, more strains must be sequenced and compared with other existing typing methods to determine the feasibility and reliability of the cmp-based typing tool. The serotypes of the majority of Campylobacter strains examined in this study were not determined. It is not known if cmp sequences cluster within certain serotypes.

The isolation of pure MOMP from C. jejuni represents a difficult challenge, since the MOMP and other bacterial porins are usually associated with lipopolysaccharide and other polypeptidoglycan molecules (3, 11), which results in uncertainty in the immunological and functional characterization of porins. Consequently, the production of rMOMP in E. coli and its subsequent purification would greatly facilitate the characterization of MOMP in the absence of interference from other contaminant molecules. Since the native conformation of MOMP may be essential for its functions, it would be ideal if rMOMP could be expressed in E. coli in its native state. However, cloning of the full cmp ORF including the 5′ signal sequence required for membrane insertion was not successful (data not shown), possibly because targeting of rMOMP into the membrane of E. coli resulted in cytotoxic effects on the host. A similar phenomenon was reported with other bacterial porins expressed in a foreign host (28, 38). However, exclusion of the signal peptide from rMOMP led to the production of large amounts of rMOMPs in inclusion bodies without affecting host viability. Purification and refolding of MOMP was achieved using Empigen BB, which is a mild zwitterionic detergent and is known for its ability to preserve the antigenicity and functional activity of isolated proteins (17, 26, 47). Since the charge distribution of this zwitterion is similar to that of membrane phopholipids (26), it was expected to facilitate the refolding of rMOMPs. Indeed, folded monomers were observed with Empigen-purified rMOMP33291(Fig. 6), which substantially reduced the reactivity of rabbit antibodies with surface-exposed conformational epitopes, suggesting that Empigen BB at least partially restored the native conformation of rMOMP. There are several possible explanations for the lack of trimeric rMOMP33291 on SDS-PAGE. It is possible that in the absence of other C. jejuni molecules, the trimeric rMOMP is unstable and sensitive to denaturation even with low concentration of SDS, resulting in a lack of detection of the trimer by SDS-PAGE. It is also conceivable that the trimeric assembly of MOMP in C. jejuni may require the interaction of the MOMP with other molecules in the organism. Consequently, rMOMP may not be assembled into trimers when expressed in a foreign host. It is known that trimer formation of the E. coli PhoE porin produced by in vitro translation requires the help of E. coli outer membrane vesicles, although the identity of the ‘helper’ molecule(s) was not defined (11). Nevertheless, even the folded monomer alone can be used for functional characterization of MOMP, since the folded monomer of MOMP displays the same topological features and porin activity as the native trimer (10).

The conclusion that the surface-exposed MOMP epitopes are conformational in nature was based on several pieces of evidence. First, antibody A-5 induced by denatured MOMP (whole molecule) strongly recognized the protein on Western blots but did not react with intact whole C. jejuni cells as determined by colony blotting (Fig. 6). Second, antibody A-8 induced by folded monomers of MOMP mainly recognized the folded monomer of rMOMP and reacted strongly with intact Campylobacter cells. Third, the reactivity of antibody A-8 with the cells was substantially reduced by native rMOMP but not by denatured rMOMP. This feature of MOMP is similar to that of other bacterial porins, for which surface-exposed epitopes are predominantly conformational (8, 36, 42).

As the major surface protein present in different strains of C. jejuni (5, 25), MOMP appears to be an attractive candidate for inclusion in vaccines. cmp is also a potential target for the design of DNA-based diagnostic or typing tools, such as PCR. However, sequence polymorphism and the conformational nature of surface-exposed MOMP epitopes must be taken into consideration when designing MOMP-based diagnostic tools or vaccines. Since the sequence polymorphism and predicted secondary structures of MOMP are known and the procedures for producing rMOMPs are established, the role of MOMP in C. jejuni infection and its possible use for the development of detection and prevention measures can now be explored.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Martin J. Blaser and David Wilson for providing some of the Campylobacter strains used in this study.

This work is supported in part by USDA NRICGP competitive grant 99-35212-8517 and a seed grant from the Research Enhancement Competitive Grants Program of OARDC at the Ohio State University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amako K, Baba N, Suzuki N, Wai S N, Umeda A. A structural analysis of the regularly arranged porin on the outer membrane of Campylobacter jejuni based on correlation averaging. Microbiol Immunol. 1997;41:855–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1997.tb01940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amako K, Wai S N, Umeda A, Shigematsu M, Takade A. Electron microscopy of the major outer membrane protein of Campylobacter jejuni. Microbiol Immunol. 1996;40:749–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1996.tb01136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bacon D J, Johnson W M, Rodgers F G. Identification and characterisation of a cytotoxic porin-lipopolysaccharide complex from Campylobacter jejuni. J Med Microbiol. 1999;48:139–148. doi: 10.1099/00222615-48-2-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black R E, Levine M M, Clements M L, Hughes T P, Blaser M J. Experimental Campylobacter jejuni infection in humans. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:472–479. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blaser M J, Hopkins J A, Berka R M, Vasil M L, Wang W L. Identification and characterization of Campylobacter jejuni outer membrane proteins. Infect Immun. 1983;42:276–284. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.1.276-284.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blaser M J, Hopkins J A, Vasil M L. Campylobacter jejuni outer membrane proteins are antigenic for humans. Infect Immun. 1984;43:986–993. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.3.986-993.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolla J M, Loret E, Zalewski M, Pages J M. Conformational analysis of the Campylobacter jejuni porin. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4266–4271. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.15.4266-4271.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchanan S K. Beta-barrel proteins from bacterial outer membranes: structure, function and refolding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1999;9:455–461. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(99)80064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cowan S W, Schirmer T, Rummel G, Steiert M, Ghosh R, Pauptit R A, Jansonius J N, Rosenbusch J P. Crystal structures explain functional properties of two E. coli porins. Nature. 1992;358:727–733. doi: 10.1038/358727a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De E, Jullien M, Labesse G, Pages J M, Molle G, Bolla J M. MOMP (major outer membrane protein) of campylobacter jejuni; a versatile pore-forming protein. FEBS Lett. 2000;469:93–97. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Cock H, Hendriks R, de Vrije T, Tommassen J. Assembly of an in vitro synthesized Escherichia coli outer membrane porin into its stable trimeric configuration. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:4646–4651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Derrick J P, Urwin R, Suker J, Feavers I M, Maiden M C. Structural and evolutionary inference from molecular variation in Neisseria porins. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2406–2413. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2406-2413.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibson J, Lorenz E, Owen R J. Lineages within Campylobacter jejuni defined by numerical analysis of pulsed-field gel electrophoretic DNA profiles. J Med Microbiol. 1997;46:157–163. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-2-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibson J R, Fitzgerald C, Owen R J. Comparison of PFGE, ribotyping and phage-typing in the epidemiological analysis of Campylobacter jejuni serotype HS2 infections. Epidemiol Infect. 1995;115:215–225. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800058349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huyer M, Parr T R, Hancock R E W, Page W J. Outer membrane porin protein of Campylobacter jejuni. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1986;37:247–250. [Google Scholar]

- 17.James L T, Heckels J E. An improved method for the isolation of the major protein of the gonococcal outer membrane in an antigenically reactive form. J Immunol Methods. 1981;42:223–228. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(81)90152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeanteur D, Lakey J H, Pattus F. The bacterial porin superfamily: sequence alignment and structure prediction. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2153–2164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kervella M, Fauchere J L, Fourel D, Pages J M. Immunological cross-reactivity between outer membrane pore proteins of Campylobacter jejuni and Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;78:281–285. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90041-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ketley J M. The 16th C. L. Oakley Lecture. Virulence of Campylobacter species: a molecular genetic approach. J Med Microbiol. 1995;42:312–327. doi: 10.1099/00222615-42-5-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konkel M E, Kim B J, Klena J D, Young C R, Ziprin R. Characterization of the thermal stress response of Campylobacter jejuni. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3666–3672. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3666-3672.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lam K M, DaMassa A J, Morishita T Y, Shivaprasad H L, Bickford A A. Pathogenicity of Campylobacter jejuni for turkeys and chickens. Avian Dis. 1992;36:359–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lampe M F, Wong K G, Kuehl L M, Stamm W E. Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein variants escape neutralization by both monoclonal antibodies and human immune sera. Infect Immun. 1997;65:317–319. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.317-319.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Logan S M, Trust T J. Outer membrane characteristics of Campylobacter jejuni. Infect Immun. 1982;38:898–906. doi: 10.1128/iai.38.3.898-906.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowthert L A, Ku N O, Liao J, Coulombe P A, Omary M B. Empigen BB: a useful detergent for solubilization and biochemical analysis of keratins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;206:370–379. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lukacova M, Gajdosova E, Skultety L, Kovacova E, Kazar J. Characterization and protective effect of a 29 kDa protein isolated from Coxiella burnetii by detergent Empigen BB. Eur J Epidemiol. 1994;10:227–230. doi: 10.1007/BF01730376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luo Y, Glisson J R, Jackwood M W, Hancock R E, Bains M, Cheng I H, Wang C. Cloning and characterization of the major outer membrane protein gene (ompH) of Pasteurella multocida X-73. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7856–7864. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.24.7856-7864.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malorny B, Morelli G, Kusecek B, Kolberg J, Achtman M. Sequence diversity, predicted two-dimensional protein structure, and epitope mapping of neisserial Opa proteins. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1323–1330. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1323-1330.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moser I, Schroeder W, Salnikow J. Campylobacter jejuni major outer membrane protein and a 59-kDa protein are involved in binding to fibronectin and INT 407 cell membranes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;157:233–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nachamkin I, Allos B M, Ho T. Campylobacter species and Guillain-Barré syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:555–567. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.3.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.On S L, Nielsen E M, Engberg J, Madsen M. Validity of SmaI-defined genotypes of Campylobacter jejuni examined by SalI, KpnI, and BamHI polymorphisms: evidence of identical clones infecting humans, poultry, and cattle. Epidemiol Infect. 1998;120:231–237. doi: 10.1017/s0950268898008668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Page W J, Huyer G, Huyer M, Worobec E A. Characterization of the porins of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli and implications for antibiotic susceptibility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:297–303. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.3.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parkhill J, Wren B W, Mungall K, Ketley J M, Churcher C, Basham D, Chillingworth T, Davies R M, Feltwell T, Holroyd S, Jagels K, Karlyshev A V, Moule S, Pallen M J, Penn C W, Quail M A, Rajandream M A, Rutherford K M, van Vliet A H, Whitehead S, Barrell B G. The genome sequence of the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals hypervariable sequences. Nature. 2000;403:665–668. doi: 10.1038/35001088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ram S, McQuillen D P, Gulati S, Elkins C, Pangburn M K, Rice P A. Binding of complement factor H to loop 5 of porin protein 1A: a molecular mechanism of serum resistance of nonsialylated Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Exp Med. 1998;188:671–680. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.4.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schirmer T. General and specific porins from bacterial outer membranes. J Struct Biol. 1998;121:101–109. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1997.3946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schroder W, Moser I. Primary structure analysis and adhesion studies on the major outer membrane protein of Campylobacter jejuni. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;150:141–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Senaratne R H, Mobasheri H, Papavinasasundaram K G, Jenner P, Lea E J, Draper P. Expression of a gene for a porin-like protein of the OmpA family from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3541–3547. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.14.3541-3547.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh M, Vohra H, Kumar L, Ganguly N K. Induction of systemic and mucosal immune response in mice immunised with porins of Salmonella typhi. J Med Microbiol. 1999;48:79–88. doi: 10.1099/00222615-48-1-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skirrow M B, Blaser M J. Clinical aspects of Campylobacter infection. In: Nachamkin I, Blaser M J, editors. Campylobacter. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 2000. pp. 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slutsker L, Altekruse S F, Swerdlow D L. Foodborne diseases. Emerging pathogens and trends. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1998;12:199–216. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stathopoulos C. Bacterial outer membrane proteins: topological analyses and biotechnological perspectives. Membr Cell Biol. 1999;13:3–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Struyve M, Moons M, Tommassen J. Carboxy-terminal phenylalanine is essential for the correct assembly of a bacterial outer membrane protein. J Mol Biol. 1991;218:141–148. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90880-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Su H, Raymond L, Rockey D D, Fischer E, Hackstadt T, Caldwell H D. A recombinant Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein binds to heparan sulfate receptors on epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11143–11148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Su H, Watkins N G, Zhang Y X, Caldwell H D. Chlamydia trachomatis-host cell interactions: role of the chlamydial major outer membrane protein as an adhesin. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1017–1025. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.1017-1025.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Putten J P, Duensing T D, Carlson J. Gonococcal invasion of epithelial cells driven by P.IA, a bacterial ion channel with GTP binding properties. J Exp Med. 1998;188:941–952. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.5.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wedege E, Bryn K, Froholm L O. Restoration of antibody binding to blotted meningococcal outer membrane proteins using various detergents. J Immunol Methods. 1988;113:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(88)90381-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weiss M S, Abele U, Weckesser J, Welte W, Schiltz E, Schulz G E. Molecular architecture and electrostatic properties of a bacterial porin. Science. 1991;254:1627–1630. doi: 10.1126/science.1721242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang D, Yang X, Berry J, Shen C, McClarty G, Brunham R C. DNA vaccination with the major outer-membrane protein gene induces acquired immunity to Chlamydia trachomatis (mouse pneumonitis) infection. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1035–1040. doi: 10.1086/516545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Q, Wise K S. Molecular basis of size and antigenic variation of a Mycoplasma hominis adhesin encoded by divergent vaa genes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2737–2744. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2737-2744.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhuang J, Engel A, Pages J M, Bolla J M. The Campylobacter jejuni porin trimers pack into different lattice types when reconstituted in the presence of lipid. Eur J Biochem. 1997;244:575–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]