Key Points

Question

Are rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and its seropositivity associated with risk of Parkinson disease (PD)?

Findings

In this cohort study of 54 680 patients with RA and 273 400 individuals without RA, those with RA had a 1.74-fold higher risk of PD than those without RA. Patients with seropositive RA had a higher risk of PD than those with seronegative RA.

Meaning

The study’s findings suggest that physicians should be aware of the elevated risk of PD in patients with RA and that prompt referral to a neurologist should be considered at onset of early motor symptoms of PD without synovitis.

This cohort study evaluates the associations of rheumatoid arthritis and its seropositivity with subsequent Parkinson disease risk in a nationally representative Korean population.

Abstract

Importance

Although it has been postulated that chronic inflammation caused by rheumatoid arthritis (RA) contributes to the development of Parkinson disease (PD), the association between these 2 conditions has yet to be determined.

Objective

To evaluate the association between RA and subsequent PD risk.

Design, Setting, and Participants

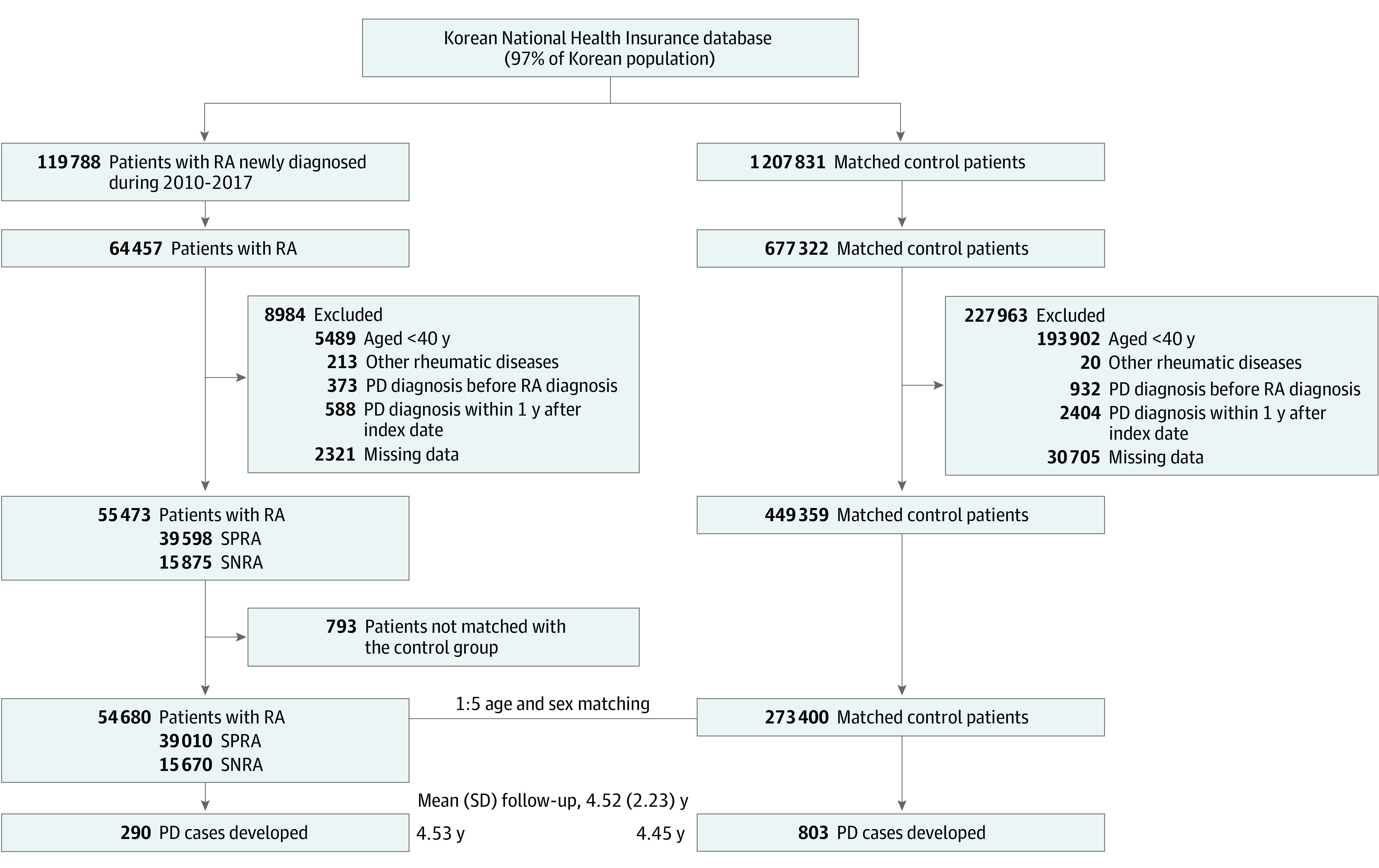

This retrospective cohort study used the Korean National Health Insurance Service database to collect population-based, nationally representative data on patients with RA enrolled from 2010 to 2017 and followed up until 2019 (median follow-up, 4.3 [IQR, 2.6-6.4] years after a 1-year lag). A total of 119 788 patients who were first diagnosed with RA (83 064 with seropositive RA [SPRA], 36 724 with seronegative RA [SNRA]) were identified during the study period and included those who underwent a national health checkup within 2 years before the RA diagnosis date (64 457 patients). After applying exclusion criteria (eg, age <40 years, other rheumatic diseases, previous PD), 54 680 patients (39 010 with SPRA, 15 670 with SNRA) were included. A 1:5 age- and sex-matched control group of patients without RA was also included for a total control population of 273 400.

Exposures

Rheumatoid arthritis as defined using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes M05 for SPRA and M06 (except M06.1 and M06.4) for SNRA; prescription of any disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; and enrollment in the Korean Rare and Intractable Diseases program.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcome was newly diagnosed PD. Data were analyzed from May 10 through August 1, 2022, using Cox proportional hazards regression analyses.

Results

From the 328 080 individuals analyzed (mean [SD] age, 58.6 [10.1] years; 74.9% female and 25.1% male), 1093 developed PD (803 controls and 290 with RA). Participants with RA had a 1.74-fold higher risk of PD vs controls (95% CI, 1.52-1.99). An increased risk of PD was found in patients with SPRA (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.95; 95% CI, 1.68-2.26) but not in patients with SNRA (aHR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.91-1.57). Compared with the SNRA group, those with SPRA had a higher risk of PD (aHR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.20-2.16). There was no significant interaction between covariates on risk of PD.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, RA was associated with an increased risk of PD, and seropositivity of RA conferred an augmented risk of PD. The findings suggest that physicians should be aware of the elevated risk of PD in patients with RA and promptly refer patients to a neurologist at onset of early motor symptoms of PD without synovitis.

Introduction

The pathogenesis of Parkinson disease (PD) has been largely elusive, except for a small fraction of cases caused by rare genetic variants.1 Multiple lines of clinical and experimental evidence have suggested that autoimmunity is involved in the activation of microglia and monocytes that play a central role in the initiation and amplification of brain inflammation.2 In addition, recent genome-wide association and pathway analyses have revealed that several genetic variants associated with PD have pleiotropic effects on the risk of various autoimmune diseases and have highlighted the potential link between autoimmune disorders and PD incidence.3

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most prevalent autoimmune disease.4 Although chronic inflammation caused by RA is hypothesized to contribute to the development of PD,5,6 the association between RA and subsequent PD incidence remains uncertain. To date, there have been only 5 studies on this topic, and the results are conflicting7,8,9,10,11 (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Case-control studies from Denmark11 and Sweden9 reported that patients with RA had a 30% reduced risk of PD compared with individuals without RA. However, a retrospective cohort study from Sweden reported no association between RA and subsequent PD diagnosis.8 One retrospective cohort study from Taiwan suggested that RA was inversely associated with a 35% reduced risk of developing PD,10 but a more recent study suggested a 14% increased risk.7

There are several limitations in previous studies. First, in most studies, smoking status was not considered when evaluating the association of RA with risk of PD,9,10,11,12,13 although 1 study indirectly adjusted for presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as a proxy of smoking status.12 Second, other potential confounding variables, such as body mass index,14 diabetes,14,15 and dyslipidemia,16 which are known to be associated with risk of PD, were not considered. Third, because RA previously was defined using only disease codes,9,10,11,12,13 information on the use of conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs) was not considered, and misclassification was possible.9,17 Fourth, the impact of RA seropositivity on the development of PD has not been evaluated.9,10,11,12,13 Fifth, a lag before PD incidence was not applied in previous analysis models.9,11 In this context, our study evaluated the association between RA and subsequent PD risk using nationally representative, population-based cohort data.

Methods

Data Source and Setting

In this cohort study, we used National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) data. The NHIS is a universal social insurance program that covers 97% of the entire Korean population. The NHIS also manages administrative processes for Medicaid beneficiaries (3% of the population with the lowest income) and reimburses medical professionals for their service. Therefore, the NHIS has information on demographic characteristics, health care use, and diagnostic codes based on the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). The present study was approved by the institutional review board of Samsung Medical Center. The requirement for written informed consent was waived because of the anonymized feature of the data set. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

In addition, the NHIS provides a national health screening program for all people 40 years or older biannually. The screening program data comprise anthropometric measurements, self-administered questionnaires on health behavior, and laboratory tests.12,15,16,17,18

Study Participants

Individuals who were first diagnosed with RA between 2010 and 2017 were eligible for the study. Among these individuals, 119 788 with RA (83 064 with seropositive RA [SPRA] and 36 724 seronegative RA [SNRA]) were identified according to the following criteria: (1) had a registered diagnostic code for RA (ICD-10 M05 for SPRA and M06 except M06.1 and M06.4 for SNRA); (2) had a prescription of any DMARD, including conventional synthetic DMARDs, bDMARDs, and target-specific DMARDs (tsDMARDs) (eTable 2 in Supplement 1), for 180 days or more; and (3) were enrolled in the Rare and Intractable Disease (RID) program for SPRA. The RID program provides a copayment reduction of up to 10% for various RIDs, including RA. To be registered in the RID program, certification of diagnosis submitted by a physician (usually a rheumatologist) is required, and the date of registration in the program for SPRA and administration of the first RA ICD-10 code for SNRA were defined as the index date.

From the RA cases identified, we included patients who underwent a national health checkup within 2 years before the RA diagnosis date so that we could obtain information on medical and health behavior from the health screening results. We then excluded participants (1) younger than 40 years (n = 5489), (2) registered in the RID program for other rheumatic diseases (eTable 3 in Supplement 1) (n = 213), (3) with a history of PD (n = 373), (4) diagnosed with PD within 1 year after the index date (lag) (n = 588), (5) with missing data (n = 2321), and (6) who were not matched by age and sex with the control group (n = 793). Finally, a total of 54 680 patients with RA (39 010 with SPRA and 15 670 with SNRA) were included in the study. Participants with codes for both SPRA and SNRA were classified as having SPRA.

For the control group, we obtained an initial control pool of 1 207 831 individuals who did not have an RA diagnosis matched by age, sex, and index year (1:10 matching). After applying identical exclusion criteria, 1:5 age and sex matching was conducted to select the final non-RA control group. Thus, 273 400 patients without RA were included in the analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Study Participants.

PD indicates Parkinson disease; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SNRA, seronegative rheumatoid arthritis; SPRA, seropositive rheumatoid arthritis.

Outcome Ascertainment

The primary outcome was new onset of PD as defined using the ICD-10 code G20 and new registration in the RID program for PD (V124), which is required to meet the UK Parkinson Disease Society Brain Bank diagnostic criteria (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). In addition, submission of an official certification of PD must be issued by a neurologist. The UK criteria have been reported to have a diagnostic accuracy of 86.4% in a gold standard diagnostic evaluation by a neurologist experienced in PD diagnosis19 and of 82% in autopsy results.20 This definition has been used widely in previous epidemiologic studies on PD with reliable validity.12,17,21 The study participants were followed from 1 year after RA diagnosis or corresponding index date to the date of PD incidence, censor date, or December 31, 2019 (end date).

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics of study participants according to the presence of RA and serologic status of RA were compared using a t test for continuous variables and a χ2 test for categorical variables. Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were performed to test the association between RA and risk of PD. We sequentially adjusted for the following covariates (eMethods in Supplement 1) in the multivariate analysis: model 1 included age, sex, smoking, alcohol drinking, physical activity, low income, and BMI; model 2 included model 1 plus diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and chronic kidney disease; and model 3 included model 2 plus myocardial infarction, stroke, and depression.

Several additional analyses were performed. First, sensitivity analyses with longer lags (2, 3, and 5 years) were performed to reduce the possible bias from increased detection of PD in patients with RA. Second, stratified analyses were conducted to evaluate the interactive effects of covariates on the association of RA with risk of PD. Among women, menopausal status, age at menopause, and hormone replacement therapy (HRT) were also evaluated. Third, the association between type of DMARDs used and risk of PD was explored. The risk was estimated according to exposure to bDMARDs, tsDMARDs, or both during the follow-up period. All statistical analyses were performed from May 10 through August 1, 2022, using SAS, version 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc), and a 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants

The mean age (SD) of study participants (N = 328 080) at the index date was 58.6 (10.1) years; 74.9% were female, and 25.1% were male. The patients with RA were more likely to be current smokers (11.1% vs 10.7%), were less likely to have obesity (69.6% vs 66.4%), consumed less alcohol (23.6% vs 29.1%), and were less likely to engage in regular physical activity (18.3% vs 20.8%) than those without RA. Patients in the SPRA group were more likely to be older (30.2% vs 25.8%), female (75.5% vs 73.3%), and current smokers (11.6% vs 9.5%) and less likely to have obesity (29.4% vs 32.9%), consume alcohol (23.0% vs 24.9%), and engage in regular physical activity (17.8% vs 19.7%) than those in the SNRA group (Table 1). eTable 10 in Supplement 1 shows a comparison of baseline characteristics between participants and nonparticipants of the health checkup within 2 years from the index date.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Study Patients.

| Characteristic | Total (N = 328 080) | RA status | Serologic status of RA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 273 400) | Yes (n = 54 680) | P value | SMD | SNRA (n = 15 670) | SPRA (n = 39 010) | P value | SMD | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 58.6 (10.1) | 58.6 (10.1) | 58.6 (10.1) | >.99 | 0 | 57.8 (10.0) | 58.9 (10.1) | <.001 | .114 |

| 40-64 | 233 166 (71.1) | 194 305 (71.1) | 38 861 (71.1) | 11 629 (74.2) | 27 232 (69.8) | ||||

| ≥65 | 94 914 (28.9) | 79 095 (28.9) | 15 819 (28.9) | 4041 (25.8) | 11 778 (30.2) | ||||

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 82 404 (25.1) | 68 670 (25.1) | 13 734 (25.1) | >.99 | 0 | 4189 (26.7) | 9545 (24.5) | <.001 | .052 |

| Female | 245 676 (74.9) | 20 4730 (74.9) | 40 946 (74.9) | 11 481 (73.3) | 29 465 (75.5) | ||||

| Income | |||||||||

| <25% + Medicaid group | 76 983 (23.5) | 64 191 (23.5) | 12 792 (23.4) | .67 | .002 | 12 161 (77.6) | 29 727 (76.2) | <.001 | .033 |

| >25% | 251 097 (76.5) | 209 209 (76.5) | 41 888 (76.6) | 3509 (22.4) | 9283 (23.8) | ||||

| Smoking status | |||||||||

| Never-smoker | 260 705 (79.5) | 217 978 (79.7) | 42 727 (78.1) | <.001 | .039 | 12 198 (77.8) | 30 529 (78.3) | <.001 | .010 |

| Ex-smoker + <20 pack-y | 18 910 (5.8) | 15 676 (5.7) | 3234 (5.9) | .008 | 1161 (7.4) | 2073 (5.31) | .086 | ||

| Ex-smoker + ≥20 pack-y | 13 298 (4.1) | 10 613 (3.9) | 2685 (4.9) | .050 | 824 (5.3) | 1861 (4.8) | .022 | ||

| Current smoker + <20 pack-y | 17 404 (5.3) | 14 633 (5.4) | 2771 (5.1) | .013 | 772 (4.9) | 1999 (5.1) | .009 | ||

| Current smoker + ≥20 pack-y | 17 763 (5.4) | 14 500 (5.3) | 3263 (6.0) | .029 | 715 (4.6) | 2548 (6.5) | .086 | ||

| Alcohol consumption | |||||||||

| None | 235 686 (71.8) | 193 905 (70.9) | 41 781 (76.4) | <.001 | .125 | 11 755 (75.0) | 30 026 (77.0) | <.001 | .046 |

| Mild (<30 g/d) | 81 076 (24.7) | 69 654 (25.5) | 11 422 (20.9) | .109 | 3454 (22.0) | 7968 (20.4) | .040 | ||

| Heavy (≥30 g/d) | 11 318 (3.5) | 9841 (3.6) | 1477 (2.7) | .051 | 461 (2.9) | 1016 (2.6) | .021 | ||

| Physical activity | |||||||||

| None | 261 247 (79.6) | 216 594 (79.2) | 44 653 (81.7) | <.001 | .062 | 12 588 (80.3) | 32 065 (82.2) | <.001 | .048 |

| Regular | 66 833 (20.4) | 56 806 (20.8) | 10 027 (18.3) | 3082 (19.7) | 6945 (17.8) | ||||

| Body mass indexa | |||||||||

| <18.5 | 9324 (2.8) | 7237 (2.7) | 2087 (3.8) | <.001 | .066 | 517 (3.3) | 1570 (4.0) | <.001 | NA |

| 18.5-22.9 | 127 102 (38.7) | 104 475 (38.2) | 22 627 (41.4) | .065 | 6145 (39.2) | 16 482 (42.3) | |||

| 23.0-24.9 | 83 076 (25.3) | 69 736 (25.5) | 13 340 (24.4) | .026 | 3844 (24.5) | 9496 (24.3) | |||

| 25.0-29.9 | 95 980 (29.3) | 81 260 (29.7) | 14 720 (26.9) | .062 | 4501 (28.7) | 10 219 (26.2) | |||

| ≥30.0 | 12 598 (3.8) | 10 692 (3.9) | 1906 (3.5) | .023 | 663 (4.2) | 1243 (3.2) | |||

| Diabetes | 43 809 (13.4) | 36 418 (13.3) | 7391 (13.5) | .218 | .006 | 2251 (14.4) | 5140 (13.2) | <.001 | .039 |

| Hypertension | 128 345 (39.1) | 105 349 (38.5) | 22 996 (42.1) | <.001 | .072 | 6984 (44.6) | 16 012 (41.1) | <.001 | .062 |

| Dyslipidemia | 109 338 (33.3) | 90 641 (33.2) | 18 697 (34.2) | <.001 | .022 | 5869 (37.5) | 12 828 (32.9) | <.001 | .004 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 23 184 (7.1) | 18 465 (6.9) | 4719 (8.6) | <.001 | .070 | 1501 (9.6) | 3218 (8.3) | <.001 | .057 |

| Myocardial infarction | 2101 (0.6) | 1490 (0.5) | 611 (1.1) | <.001 | .063 | 189 (1.2) | 422 (1.1) | .21 | .055 |

| Stroke | 1935 (0.6) | 1422 (0.5) | 513 (0.9) | <.001 | .049 | 162 (1.0) | 351 (0.9) | .14 | .035 |

| Depression | 23 804 (7.3) | 16 111 (5.9) | 7693 (14.1) | <.001 | .275 | 2429 (15.5) | 5264 (13.5) | <.001 | .071 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; SMD, standardized mean difference; SNRA, seronegative rheumatoid arthritis; SPRA, seropositive rheumatoid arthritis.

Measured as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Risk of PD According to the Presence of RA and RA Serologic Status

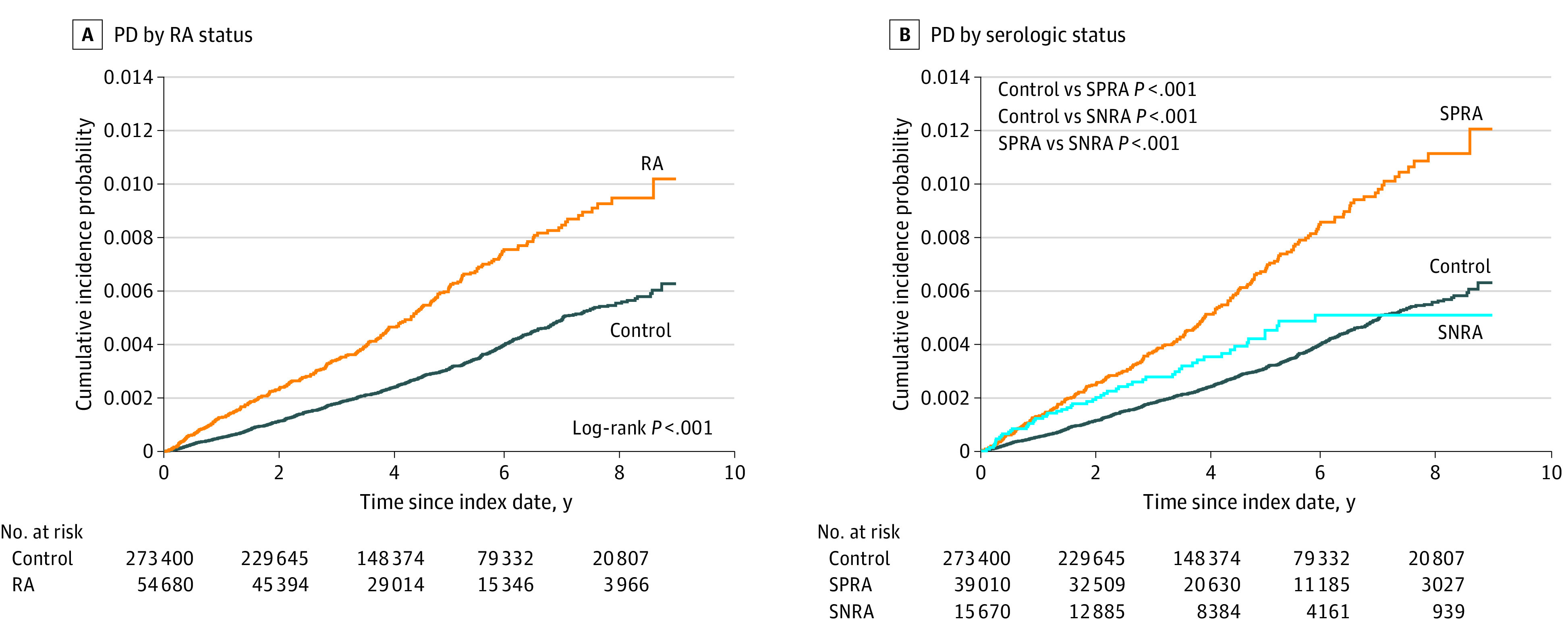

A total of 1093 patients developed PD (803 in the control group and 290 in the RA group) during the follow-up period of 1 481 363.6 person-years, corresponding to a median of 4.3 years (IQR, 2.6-6.4 years) and maximum of 9 years after a 1-year lag (Figure 2). Patients with RA showed a 1.84-fold higher risk for PD than the control patients in the crude model (95% CI, 1.61-2.10), and this association was consistent across models 1 to 3 (model 1: adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.89 [95% CI, 1.65-2.16]; model 2: aHR, 1.87 [95% CI, 1.63-2.14]; model 3: aHR, 1.74 [95% CI, 1.52-1.99]). Patients with SPRA had an increased risk for PD compared with the control patients (model 3: aHR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.68-2.26). Although the SNRA group showed a higher risk of PD compared with control patients in model 2 (aHR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.00-1.71), the strength of the association was attenuated in model 3 (aHR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.91-1.57). Compared with the SNRA group, the SPRA group had a higher risk of PD (model 3: aHR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.20-2.16) (Table 2). A sensitivity analysis applying longer lags did not alter the observed associations (eTable 5 in Supplement 1).

Figure 2. Cumulative Incidence of Parkinson Disease (PD) According to Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) Status and Serologic Status of RA.

SNRA indicates seronegative rheumatoid arthritis; SPRA, seropositive rheumatoid arthritis.

Table 2. Risk of Parkinson Disease According to Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) Status and Serologic Status of RA.

| No. | Event, No. | Duration, person-y | Incidence rate (per 1000 person-y) | HR (95% CI)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

| By RA status | ||||||||

| Control | 273 400 | 803 | 1237 781.0 | 0.65 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| RA | 54 680 | 290 | 243 582.6 | 1.19 | 1.84 (1.61-2.10) | 1.89 (1.65-2.16) | 1.87 (1.63-2.14) | 1.74 (1.52-1.99) |

| By RA status and seropositivity | ||||||||

| Control | 273 400 | 803 | 1 237 781.0 | 0.65 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| SNRA | 15 670 | 56 | 68 804.0 | 0.81 | 1.26 (0.96-1.65) | 1.34 (1.02-1.75) | 1.31 (1.00-1.71) | 1.20 (0.91-1.57) |

| SPRA | 39 010 | 234 | 174 778.6 | 1.34 | 2.07 (1.79-2.39) | 2.10 (1.81-2.43) | 2.09 (1.80-2.41) | 1.95 (1.68-2.26) |

| By seropositivity | ||||||||

| SNRA | 15 670 | 56 | 68 804.0 | 0.81 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| SPRA | 39 010 | 234 | 174 778.6 | 1.34 | 1.65 (1.23-2.21) | 1.56 (1.16-2.09) | 1.59 (1.19-2.14) | 1.61 (1.20-2.16) |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; SNRA, seronegative rheumatoid arthritis; SPRA, seropositive rheumatoid arthritis.

Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, smoking, alcohol drinking, physical activity, low income, and body mass index; model 2 was adjusted additionally for diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and chronic kidney disease; and model 3 was adjusted additionally for myocardial infarction, stroke, and depression.

Stratified Analyses

There was no significant interaction between RA and socioeconomic characteristics, health behavior, and comorbid conditions on the risk of PD (eTable 6 in Supplement 1). There was also no significant interaction with RA serologic status (eTable 7 in Supplement 1). The RA-PD association was stronger in premenopausal women (aHR, 4.43; 95% CI, 2.05-9.59) than in postmenopausal women (aHR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.46-2.10; P for interaction = .02). Among postmenopausal women, the age at menopause onset or HRT did not have a significant interaction with RA in the development of PD (eTable 8 in Supplement 1).

Exploratory Analyses of DMARDs

Only a small number of patients with PD (n = 15) used bDMARDs or tsDMARDs. Patients with RA who did not use bDMARDs had a higher risk of PD than the control group (aHR, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.54-2.04), whereas patients with RA who used bDMARDs did not show a higher risk compared with the control group (aHR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.65-1.05) (eTable 9 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

In this cohort study, we found that participants with RA had a 1.74-fold higher risk of PD compared with those without RA, and SPRA was associated with a markedly increased occurrence of PD. Although the SNRA group also showed a higher risk of PD, it was attenuated in the fully adjusted model. Compared with SNRA, SPRA was associated with an elevated risk of PD.

The risk of PD in the RA group was significantly higher than in the non-RA group, and this finding was consistent with a recent nationwide cohort study from Taiwan (aHR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.03-1.28).7 However, other studies have reported that RA had no association8 or an inverse association with risk of PD.9,10,11 Although the reason for the discrepancies in the association between RA and PD is unclear, the strength of the current study’s methodology compared with previous work could be recognized in the following aspects. First, tobacco smoking, which has an inverse association with incident PD22 and is associated with an increased risk of RA,23 was not considered in most studies.9,10,11 In contrast, our study adjusted for smoking status with pack-year data to address potential confounding. Second, the definition of RA in most previous studies was based solely on disease codes,8,9,11 so misclassification was possible. If patients with arthralgia who did not meet RA diagnosis criteria were classified as having RA, this could have led to a null association. One Taiwanese study used a combination of disease codes and a critical disease registration program to determine RA cases, but almost one-half of the patients with RA did not take DMARDs, suggesting a possible false-positive diagnosis.10 However, our study defined RA based on disease code, RID program enrollment, and prescription data for DMARDs to minimize misclassification issues related to the definition of RA.15 Third, patients with RA included in previous studies were diagnosed in the 1980s to 2000s, when diagnostic accuracy and treatment practice were different from those of our study, which included patients with RA diagnosed from 2010 through 2017. In addition, competing mortality from cardiovascular disease or cancer could also be higher than that of our study, which would decrease the risk of PD.24

Although the underlying mechanisms of the potential link between RA and incident PD remain elusive, microglia-mediated neuroinflammation has been suggested as a plausible explanation.2 A substantial increase in systemic inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) in RA, could be involved in the development of PD.5,6 Elevated serum TNF-α and IL-6 levels could induce the activation of microglia, which was observed in the substantia nigra.25,26 In addition, the activated microglia are involved in upregulation of several proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and interferon-γ, which are associated with dysfunction and degeneration of nigral dopaminergic neurons.27,28 In the process of neuronal degeneration, neurotoxic molecules, including α-synuclein and metalloproteinase-3, are released from dopaminergic neurons, and these molecules amplify the progress of PD by activating additional microglia and accelerating the production of inflammatory cytokines.29,30 A previous study showed that patients with a high level of plasma IL-6 had an elevated risk of developing PD, supporting the role of peripheral inflammatory cytokines in the development of PD.31

Seropositivity conferred an augmented risk of PD among participants with RA. Patients with SPRA had a higher risk of PD (aHR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.68-2.26) than the control group, whereas an elevated aHR for PD in the SNRA group (aHR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.91-1.57) was not significant. Despite controversies on disease course and prognosis, SNRA has been considered a mild form of RA, with less joint erosion and fewer extra-articular manifestations compared with SPRA.32,33,34 In parallel with distinctive disease trajectories and prognosis of SPRA from SNRA, the risk of PD in SPRA was more evident (aHR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.20-2.16), and this finding was, at least partially, in line with a recent study from the US reporting that SPRA was associated with a 2.9-fold higher risk of dementia compared with SNRA.35 To date, the association of seropositivity with the risk of PD is unknown because of the difficulty in obtaining large populations to study this association with sufficient power and misclassification of SNRA based on definitions used in administrative data.

With respect to the pathologic explanation of the link between SPRA and PD, impairment in autophagic pathways, which normally remove damaged or abnormally modified proteins, might be a shared pathologic process of the 2 conditions. The role of autophagy in the generation of citrullinated proteins, which are subsequently processed to SPRA-associated citrullinated antigens and consequently become a target of anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, has been reported in previous studies.36,37 Disruption of this process is a well-demonstrated pathogenesis in the development of PD and other neurodegenerative diseases.38 Increased expression of autophagy-related protein light chain 3-II in synovial fibroblasts of RA37 and the substantia nigra of PD39,40 also provides supportive evidence of this plausible pathologic link between SPRA and PD.

The RA-PD association was stronger in premenopausal women than in postmenopausal women. Premenopausal women may not have other risk factors for PD, including age and estrogen deficiency41; therefore, the influence of RA could be more prominent than in postmenopausal women. However, there was no significant interaction with sex, age at menopause, and HRT. Potential sex differences and the influence of reproductive factors in relation to RA on PD risk need further investigation.41,42

In our exploratory analyses, bDMARD users did not have an elevated risk of PD, while nonusers had an increased risk. This finding may imply that bDMARDs may offset the increased risk of PD. Similarly, another study43 observed a higher incidence of PD in patients with inflammatory bowel disease than in individuals without, but exposure to anti-TNF therapy was associated with substantially reduced PD incidence, which supports the role of systemic inflammation in the pathogenesis of both diseases. Our study was limited by the use of bDMARDs or tsDMARDs in only 8% of patients with RA, and the number of PD cases was too small to draw any firm conclusion. Further studies are needed to explore the potential benefit of newer DMARDs.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, although we evaluated the risk of PD according to serologic status, RA disease activity was not accessible, resulting in a limited evaluation of the severity of RA and the risk of PD. Second, our study was retrospective and might be subject to surveillance bias. It is possible that patients with RA might have received more frequent health care services and were more likely to obtain a PD diagnosis. On the other hand, patients with prodromal, early, or undiagnosed PD may have undergone evaluations for nondescript motor and nonmotor symptoms and decline in mobility or function, which might result in identification of coexistent RA. However, our sensitivity analyses with a longer lag period did not attenuate the strength of the association, suggesting a true association between RA and PD. Third, information on potential confounders, such as genetic information,1 family history,44 and exposure to environmental toxicants,45 was not available, so residual confounding may exist. Fourth, because we included participants with a health checkup, issues of generalizability might be raised. Patients with health checkups were older, had a higher income, and were more likely to be on prescribed hypertension and dyslipidemia medications compared with participants without health checkups; they also had a lower prevalence of chronic kidney disease, myocardial infarction, and stroke, indicating better health status and better health behavior46 (eTable 10 in Supplement 1). However, as individuals in both the RA and non-RA groups underwent health screening, it is unlikely that selection bias affected the associations found in our study.

Conclusions

In this cohort study, we found that RA was associated with an increased risk of PD and that SPRA conferred an augmented risk of PD. Further studies are necessary to determine a mechanistic link between RA and PD. The study findings suggest that physicians who care for patients with RA should be aware of the elevated risk of PD and prompt referral to a neurologist should be considered at onset of early motor symptoms of PD in patients with RA without synovitis.

eMethods. Covariates

eReferences.

eTable 1. Previous Studies on the Association Between Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) and Incident Parkinson Disease

eTable 2. Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs Used in the Definition of These Diseases

eTable 3. List of Diseases in the Rare and Intractable Disease (RID) Program Excluded From the Study

eTable 4. Registration criteria for Parkinson Disease in the Rare and Intractable Disease (RID) Program of Korea

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analysis Evaluating the Risk of Parkinson Disease According to RA Status and Serologic Status of RA With 2-, 3-, and 5-Year Lags

eTable 6. Stratified Analyses of the Association Between Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) Status and Parkinson Disease (PD) Risk by Socioeconomic Characteristics, Health Behaviors, and Comorbidities

eTable 7. Stratified Analyses of the Association Between Serologic Status of Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) and Parkinson Disease Risk by Socioeconomic Characteristics, Health Behaviors, and Comorbidities

eTable 8. The Association of Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) and Its Seropositivity With the Risk of Parkinson Disease According to Female Reproductive Factors

eTable 9. Exploratory Analysis Evaluating the Risk of Parkinson Disease According to Exposure to Conventional Synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs), Biological DMARDs (bDMARDs), and Target-Specific DMARDs (tsDMARDs)

eTable 10. Comparison of Baseline Characteristics Between Participants and Nonparticipants of the Health Checkup Within 2 Years From the Index Date

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Dächsel JC, Farrer MJ. LRRK2 and Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(5):542-547. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan EK, Chao YX, West A, Chan LL, Poewe W, Jankovic J. Parkinson disease and the immune system—associations, mechanisms and therapeutics. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16(6):303-318. doi: 10.1038/s41582-020-0344-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Witoelar A, Jansen IE, Wang Y, et al. ; International Parkinson’s Disease Genomics Consortium (IPDGC), North American Brain Expression Consortium (NABEC), and United Kingdom Brain Expression Consortium (UKBEC) Investigators . Genome-wide pleiotropy between Parkinson disease and autoimmune diseases. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(7):780-792. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.0469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McInnes IB, Schett G. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(23):2205-2219. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1004965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldmann M, Brennan FM, Maini RN. Role of cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14(1):397-440. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dobbs RJ, Charlett A, Purkiss AG, Dobbs SM, Weller C, Peterson DW. Association of circulating TNF-α and IL-6 with ageing and parkinsonism. Acta Neurol Scand. 1999;100(1):34-41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1999.tb00721.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang CC, Lin TM, Chang YS, et al. Autoimmune rheumatic diseases and the risk of Parkinson disease: a nationwide population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Ann Med. 2018;50(1):83-90. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2017.1412088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Subsequent risks of Parkinson disease in patients with autoimmune and related disorders: a nationwide epidemiological study from Sweden. Neurodegener Dis. 2012;10(1-4):277-284. doi: 10.1159/000333222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bacelis J, Compagno M, George S, et al. Decreased risk of Parkinson’s disease after rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis: a nested case-control study with matched cases and controls. J Parkinsons Dis. 2021;11(2):821-832. doi: 10.3233/JPD-202418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sung YF, Liu FC, Lin CC, et al. Reduced risk of Parkinson disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a nationwide population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(10):1346-1353. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rugbjerg K, Friis S, Ritz B, Schernhammer ES, Korbo L, Olsen JH. Autoimmune disease and risk for Parkinson disease: a population-based case-control study. Neurology. 2009;73(18):1462-1468. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c06635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeong SM, Han K, Kim D, Rhee SY, Jang W, Shin DW. Body mass index, diabetes, and the risk of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2020;35(2):236-244. doi: 10.1002/mds.27922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhee SY, Han K-D, Kwon H, et al. Association between glycemic status and the risk of Parkinson disease: a nationwide population-based study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(9):2169-2175. doi: 10.2337/dc19-0760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeong SM, Jang W, Shin DW. Association of statin use with Parkinson’s disease: dose-response relationship. Mov Disord. 2019;34(7):1014-1021. doi: 10.1002/mds.27681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho SK, Sung YK, Choi CB, Kwon JM, Lee EK, Bae SC. Development of an algorithm for identifying rheumatoid arthritis in the Korean National Health Insurance claims database. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(12):2985-2992. doi: 10.1007/s00296-013-2833-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheol Seong S, Kim Y-Y, Khang Y-H, et al. Data resource profile: the national health information database of the National Health Insurance Service in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(3):799-800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nam GE, Kim NH, Han K, et al. Chronic renal dysfunction, proteinuria, and risk of Parkinson’s disease in the elderly. Mov Disord. 2019;34(8):1184-1191. doi: 10.1002/mds.27704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shin DW, Cho J, Park JH, Cho B. National General Health Screening Program in Korea: history, current status, and future direction. Precision and Future Medicine. 2022;6(1):9-31. doi: 10.23838/pfm.2021.00135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Postuma RB, Poewe W, Litvan I, et al. Validation of the MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2018;33(10):1601-1608. doi: 10.1002/mds.27362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, Lees AJ. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55(3):181-184. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.3.181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park J-H, Kim D-H, Kwon D-Y, et al. Trends in the incidence and prevalence of Parkinson’s disease in Korea: a nationwide, population-based study. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):320. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1332-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernán MA, Takkouche B, Caamaño-Isorna F, Gestal-Otero JJ. A meta-analysis of coffee drinking, cigarette smoking, and the risk of Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2002;52(3):276-284. doi: 10.1002/ana.10277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugiyama D, Nishimura K, Tamaki K, et al. Impact of smoking as a risk factor for developing rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(1):70-81. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.096487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sidney S, Quesenberry CP Jr, Jaffe MG, et al. Recent trends in cardiovascular mortality in the United States and public health goals. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(5):594-599. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leal MC, Casabona JC, Puntel M, Pitossi FJ. Interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α: reliable targets for protective therapies in Parkinson’s disease? Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:53. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tansey MG, McCoy MK, Frank-Cannon TC. Neuroinflammatory mechanisms in Parkinson’s disease: potential environmental triggers, pathways, and targets for early therapeutic intervention. Exp Neurol. 2007;208(1):1-25. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrari CC, Pott Godoy MC, Tarelli R, Chertoff M, Depino AM, Pitossi FJ. Progressive neurodegeneration and motor disabilities induced by chronic expression of IL-1β in the substantia nigra. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;24(1):183-193. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCoy MK, Martinez TN, Ruhn KA, et al. Blocking soluble tumor necrosis factor signaling with dominant-negative tumor necrosis factor inhibitor attenuates loss of dopaminergic neurons in models of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci. 2006;26(37):9365-9375. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1504-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saijo K, Winner B, Carson CT, et al. A Nurr1/CoREST pathway in microglia and astrocytes protects dopaminergic neurons from inflammation-induced death. Cell. 2009;137(1):47-59. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Q-S, Heng Y, Yuan Y-H, Chen N-H. Pathological α-synuclein exacerbates the progression of Parkinson’s disease through microglial activation. Toxicol Lett. 2017;265:30-37. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen H, O’Reilly EJ, Schwarzschild MA, Ascherio A. Peripheral inflammatory biomarkers and risk of Parkinson’s disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(1):90-95. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barra L, Pope JE, Orav JE, et al. ; CATCH Investigators . Prognosis of seronegative patients in a large prospective cohort of patients with early inflammatory arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(12):2361-2369. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.140082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farragher TM, Lunt M, Plant D, Bunn DK, Barton A, Symmons DP. Benefit of early treatment in inflammatory polyarthritis patients with anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies versus those without antibodies. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62(5):664-675. doi: 10.1002/acr.20207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sahatçiu-Meka V, Rexhepi S, Manxhuka-Kërliu S, Rexhepi M. Extra-articular manifestations of seronegative and seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2010;10(1):26-31. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2010.2729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kronzer V, Gunderson T, Crowson C, et al. POS0309 seropositivity increases risk of incident dementia in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(suppl 1):380-381. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ireland JM, Unanue ER. Autophagy in antigen-presenting cells results in presentation of citrullinated peptides to CD4 T cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208(13):2625-2632. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sorice M, Iannuccelli C, Manganelli V, et al. Autophagy generates citrullinated peptides in human synoviocytes: a possible trigger for anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55(8):1374-1385. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nixon RA. The role of autophagy in neurodegenerative disease. Nat Med. 2013;19(8):983-997. doi: 10.1038/nm.3232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dehay B, Bové J, Rodríguez-Muela N, et al. Pathogenic lysosomal depletion in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci. 2010;30(37):12535-12544. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1920-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alvarez-Erviti L, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Cooper JM, et al. Chaperone-mediated autophagy markers in Parkinson disease brains. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(12):1464-1472. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoo JE, Shin DW, Jang W, et al. Female reproductive factors and the risk of Parkinson’s disease: a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(9):871-878. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00672-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jeong SM, Lee HR, Jang W, et al. Sex differences in the association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2021;93:19-26. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2021.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peter I, Dubinsky M, Bressman S, et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy and incidence of Parkinson disease among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(8):939-946. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao X, Simon KC, Han J, Schwarzschild MA, Ascherio A. Family history of melanoma and Parkinson disease risk. Neurology. 2009;73(16):1286-1291. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bd13a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goldman SM. Environmental toxins and Parkinson’s disease. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;54:141-164. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011613-135937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee H, Cho J, Shin DW, et al. Association of cardiovascular health screening with mortality, clinical outcomes, and health care cost: a nationwide cohort study. Prev Med. 2015;70:19-25. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Covariates

eReferences.

eTable 1. Previous Studies on the Association Between Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) and Incident Parkinson Disease

eTable 2. Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs Used in the Definition of These Diseases

eTable 3. List of Diseases in the Rare and Intractable Disease (RID) Program Excluded From the Study

eTable 4. Registration criteria for Parkinson Disease in the Rare and Intractable Disease (RID) Program of Korea

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analysis Evaluating the Risk of Parkinson Disease According to RA Status and Serologic Status of RA With 2-, 3-, and 5-Year Lags

eTable 6. Stratified Analyses of the Association Between Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) Status and Parkinson Disease (PD) Risk by Socioeconomic Characteristics, Health Behaviors, and Comorbidities

eTable 7. Stratified Analyses of the Association Between Serologic Status of Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) and Parkinson Disease Risk by Socioeconomic Characteristics, Health Behaviors, and Comorbidities

eTable 8. The Association of Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) and Its Seropositivity With the Risk of Parkinson Disease According to Female Reproductive Factors

eTable 9. Exploratory Analysis Evaluating the Risk of Parkinson Disease According to Exposure to Conventional Synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs), Biological DMARDs (bDMARDs), and Target-Specific DMARDs (tsDMARDs)

eTable 10. Comparison of Baseline Characteristics Between Participants and Nonparticipants of the Health Checkup Within 2 Years From the Index Date

Data Sharing Statement