Abstract

Emission of scent volatiles by flowers is important for successful pollination and consequently, reproduction. Petunia (Petunia hybrida) floral scent is formed mainly by volatile products of the phenylpropanoid pathway. We identified and characterized a regulator of petunia scent production: the GRAS protein PHENYLPROPANOID EMISSION-REGULATING SCARECROW-LIKE (PES). Its expression increased in petals during bud development and was highest in open flowers. Overexpression of PES increased the production of floral volatiles, while its suppression resulted in scent reduction. We showed that PES upregulates the expression of genes encoding enzymes of the phenylpropanoid and shikimate pathways in petals, and of the core regulator of volatile biosynthesis ODORANT1 by activating its promoter. PES is an ortholog of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) PHYTOCHROME A SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION 1, involved in physiological responses to far-red (FR) light. Analyses of the effect of nonphotosynthetic irradiation (low-intensity FR light) on petunia floral volatiles revealed FR light as a scent-activating factor. While PHYTOCHROME A regulated scent-related gene expression and floral scent production under FR light, the influence of PES on volatile production was not limited by FR light conditions.

Far-red light, phytochrome A, and SCARECROW-like GRAS protein PES activate production of phenylpropanoid scent compounds in petunia flowers.

Introduction

The survival of many plant species is strongly dependent on their ability to attract pollinators to their flowers. This has led to the evolution of various flower forms and color patterns, and a broad spectrum of scent volatiles (Bombarely et al. 2016). Floral scent is a dynamic trait that is typically determined by a mixture of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). These compounds are generated and emitted by flowers mainly after anthesis when the flowers are ready for reproduction. In many cases, floral scent emission is coordinated with pollinator activity and occurs in a diurnal manner, peaking at the time of day when the pollinator is active. Time is mainly sensed by plants based on their circadian clock and changes in light conditions (Hoballah et al. 2005; Bloch et al. 2017; Chapurlat et al. 2018; Fenske et al. 2018). Petunia (Petunia hybrida) plants (family: Solanaceae) are commonly used in floral scent studies. Petunia has large flowers, producing a wealth of phenylpropanoid volatiles from diverse biochemical branches. Petunia VOCs are C6–C3, C6–C2, and C6–C1 molecules, derived from the amino acid phenylalanine, which in turn is synthesized predominantly via the shikimate/arogenate pathway in plastids (Lynch and Dudareva 2020). The products of central carbon metabolism—phosphoenolpyruvate and erythrose-4-phosphate—are substrates for this pathway. 5-Enol-pyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS) and chorismate synthase (CS) catalyze the last steps of the pathway: formation of 5-enol-pyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate and its conversion to chorismate. Prephenate is generated from chorismate by chorismate mutase (CM), and in subsequent reactions is converted to phenylalanine—the precursor of phenylpropanoid/benzenoid volatiles (Maeda et al. 2010; Maeda and Dudareva 2012; Lynch and Dudareva 2020). The core enzymes of the phenylpropanoid pathway branch yielding VOCs—phenylacetaldehyde synthase (PAAS) and L-phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL)—compete for the substrate (phenylalanine) to form phenylacetaldehyde or trans-cinnamic acid, respectively (Muhlemann et al. 2014). Volatile phenylacetaldehyde is a source for the formation of phenylethyl alcohol, phenylethyl acetate, and phenylethyl benzoate. Trans-cinnamate is a precursor for the synthesis of benzenoids (benzyl alcohol, benzaldehyde, benzyl benzoate, and methyl benzoate) and phenylpropenes (eugenol and isoeugenol). Methyl benzoate and benzyl benzoate are the most abundant volatiles in petunia cv. Mitchell. Their biosynthesis requires participation of the enzymes S-adenosyl-L-methionine:benzoic acid/salicylic acid carboxyl methyltransferase (BSMT) and benzoyl-CoA:benzyl alcohol/2-phenylethanol benzoyltransferase (BPBT), respectively. Cinnamate-4-hydroxylase (C4H) converts cinnamic acid to coumaric acid. The volatiles isoeugenol and eugenol are synthesized from coumaric acid in a series of reactions with the participation of 4-coumarate:CoA ligase 1 (4CL), coniferyl alcohol acetyltransferase (CFAT), isoeugenol synthase (IGS), and eugenol synthase (EGS) (Boatright et al. 2004; Pichersky and Dudareva 2007; Klempien et al. 2012; Muhlemann et al. 2014; Skaliter et al. 2022).

The precise genetic and biochemical steps involved in the regulation of the phenylpropanoid/benzenoid biosynthetic pathway are still largely unknown. Several transcription factors have been shown to govern the metabolic flow toward VOC production in petunia flowers, among them ODORANT1 (ODO1), EMISSION OF BENZENOIDS (EOB) I, EOBII, and PhMYB4. ODO1 is a positive regulator of floral volatile biosynthesis, affecting the expression of EPSPS, CM, PAL1, and PAL2 (Verdonk et al. 2005; Boersma et al. 2022). EOBI and EOBII activate the phenylpropanoid pathway by upregulating transcriptional levels of the genes encoding the biosynthetic enzymes EPSPS, CS, CM, PAL, and CFAT (Spitzer-Rimon et al. 2010, 2012). Moreover, EOBI and EOBII directly activate the ODO1 promoter (Van Moerkercke et al. 2011; Spitzer-Rimon et al. 2012). PhMYB4 and EOBV (the latter not fully characterized) repress scent production (Spitzer-Rimon et al. 2010, 2012; Colquhoun et al. 2011). All of these regulators are MYB family transcription factors.

The negative regulator of scent production, ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR (PhERF6) interacts with EOBI, thereby preventing EOBI activation of the ODO1 promoter (Liu et al. 2017). The components of the circadian system (i.e. the internal clock), LATE ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL (LHY), and GIGANTEA (GI), are also involved in regulation of VOC levels (Fenske et al. 2015; Brandoli et al. 2020). Another circadian clock component, PhCHL, an ortholog of Arabidopsis (A. thaliana) ZEITLUPE (ZTL), was recently implicated in affecting the ratios between levels of emitted petunia volatiles (Terry et al. 2019).

Very little is known about how external signals regulate scent. Light, a crucial factor in most physiological processes throughout the plant's life cycle, has been shown to affect petunia floral scent. Emission of major scent compounds by petunia flowers (phenyl benzoate and methyl benzoate) is higher under constant white light than in constant darkness (DD) (Fenske et al. 2015). In an effort to evaluate the effect of narrow-bandwidth lighting on the emission of floral volatiles, Colquhoun et al. (2013) analyzed volatiles collected for 1 h in the evening from flowers exposed to red (R) and far-red (FR) light compared to flowers kept in the dark. They revealed an increase in the emission of some scent compounds in response to R and FR light treatments. However, how light of a certain quality regulates VOC biosynthesis and emission, and what molecular mechanism, e.g. which R/FR signal-transduction pathway genes, underlies this regulation, remain unknown. White light is comprised of a combination of quants of visible light that can be absorbed by different types of photoreceptors, leading to multiple physiological responses; the photoreceptors are phytochromes, active under R/FR light; cryptochromes, phototropins, and the group of flavin-binding F-box proteins, including ZTL, which are sensitive to blue/ultraviolet A (UV-A) light; and UVR8 (UV RESPONSE LOCUS 8), absorbing UV-B light (Paik and Huq 2019). In Arabidopsis, phytochromes are encoded by 5 different genes (PHYA–PHYE) (Bae and Choi 2008). PHYTOCHROME A (PHYA) is a well-studied photoreceptor that provides sensitivity to FR light. It is responsible for physiological reactions under continuous FR and pulses of FR light, such as de-etiolation (inhibition of hypocotyl growth and cotyledon expansion, activation of chlorophyll biosynthesis), initiation of seed germination, and root gravitropic response (Nagatani et al. 1993; Takano et al. 2001; Franklin and Quail 2010; Casal et al. 2014). The PHYA signal-transduction pathway has been well characterized, based on the Arabidopsis model (Schäfer and Bowler 2002; Bae and Choi 2008; Cheng et al. 2021). Photoactivated PHYA interacts with FAR-RED ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 1 (FHY1) and FHY1-LIKE (FHL) for its translocation to the nucleus where it regulates downstream processes. One of the PHYA signaling-related factors is PHYTOCHROME A SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION 1 (PAT1, AT5G48150), but the mechanism underlying its participation in FR signal transduction is not clear (Bolle et al. 2000; Torres-Galea et al. 2013).

In this work, we investigated the involvement of FR light and PHYA in volatile production in petunia petals. We also identified and characterized a component of the machinery regulating petunia scent production, a SCARECROW-like (SCL) GRAS domain protein which is a homolog of the Arabidopsis FR signaling-related PAT1 gene. Its involvement in the control of VOC levels in response to FR light conditions is discussed.

Results

SCL GRAS protein is involved in regulation of floral scent

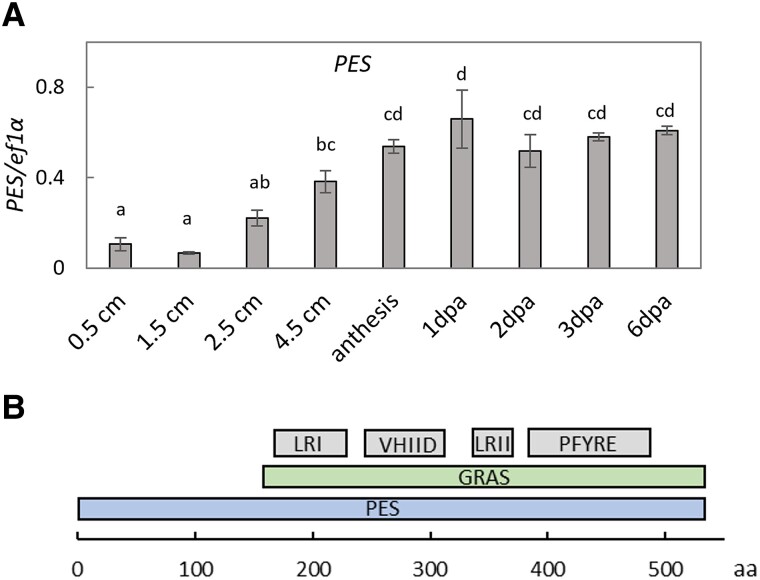

To identify regulators of scent production, we scanned the Petunia × hybrida transcriptomic database (Albo 2012) for transcripts with expression profiles corresponding to those of known scent regulators (Verdonk et al. 2005; Spitzer-Rimon et al. 2010, 2012), i.e. expression in the epidermis of mature flowers and higher expression in petals of mature flowers compared to buds. Among these sequences, we were looking for transcripts encoding proteins involved in light signaling. One of the candidates, termed PES, corresponding to Peaxi162Scf00776g00311 in the Petunia axillaris genome, was chosen for further analyses. This transcript accumulates in a flower developmental stage-dependent manner: its level is high in petals at anthesis and early post anthesis, and low in developing petals in buds (Fig. 1A). PES encodes a 533 aa protein with a C-terminal GRAS domain (Fig. 1B), which typically contains conserved motifs LRI, VHIID, LRII, and PFYRE. In the well-characterized GRAS domain of rice (Oryza sativa) SCL7 protein, the LRI subdomain contains a nuclear-localization signal; the LRII subdomain is rich in leucine repeats, making it prone to interacting with other proteins; the VHIID and PFYRE subdomains are important for maintaining the domain structure (Hofmann 2016; Li et al. 2016).

Figure 1.

Transcript levels of GRAS protein-encoding PES increase during petunia flower development. A) PES expression in young buds of different lengths and in flowers at anthesis and up to 6 d post anthesis (dpa). Data are means ± SEM (n = 4–7). Data were normalized to EF1α. For statistical analysis, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey HSD test was applied (P < 0.05). B) Domain and conservative motif structure of PES protein. LRI and LRII, leucine heptad repeat motifs; VHIID and PFYRE, motifs named after the most prominent residues.

BLASTp of PES against Arabidopsis protein sequences revealed its close relatedness to GRAS domain proteins SCL and DELLA. GRAS proteins are unique to plants and usually act as transcriptional regulators (Bolle 2004; Hirsch and Oldroyd 2009). Petunia DELLAs have been shown to be involved in scent regulation in flowers (Ravid et al. 2017). SCL GRAS proteins PAT1 and SCL21 are components of the FR signaling pathway in Arabidopsis (Bolle et al. 2000; Torres-Galea et al. 2013). A phylogenetic tree (Supplemental Fig. S1) portraying the relationship between PES and other GRAS proteins of Petunia, model dicots (tomato [Solanum lycopersicum], A. thaliana), and the monocot O. sativa showed that PES can be considered a member of the AtPAT1 subfamily of SCL proteins because it clusters with AtSCLs 1, 5, 8, 13, 21 and AtPAT1 (Bolle 2004; Sun et al. 2011; Liu and Widmer 2014). Pairwise protein sequence alignment between PES and PAT1 or SCL21 revealed a higher identity to AtPAT1, with amino acid sequence identity and similarity of 65.6% and 77.6%, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S2).

Arabidopsis pat1 mutants exhibit an FR light-specific phenotype (Bolle et al. 2000). Therefore, to evaluate the effect of PES on floral scent, we focused on the FR region of the spectrum (peak at 730 nm). Petunia cv. Mitchell plants were grown in a greenhouse and flowers were placed under far-red/dark (FR/D) light conditions (16-h light/8-h dark) 1 d prior to scent analyses. We used low-intensity FR/D lighting (20 μmol m−2 s−2) to exclude the effects of photosynthetically active radiation and to leave diurnal oscillations undisturbed. Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) based on tobacco rattle virus (TRV) was used to locally transiently suppress PES expression in the petals (Spitzer et al. 2007). Petals were agroinfiltrated with pTRV2 plasmid containing a short fragment of PES (TRV-PES) and pTRV2 alone (TRV) as a control. The inoculated tissues were used to analyze emitted VOCs by localized dynamic headspace (Fig. 2, A and B) and VOCs accumulated in internal pools (Fig. 2, C and D). Figure 2 demonstrates that under FR/D conditions, both emission and accumulation of major flower volatiles, as revealed by GC-MS analyses, were lower in TRV-PES-inoculated petal tissues, indicating that PES acts as a scent activator.

Figure 2.

PES suppression negatively affects emission and accumulation of scent volatiles in petunia flowers under FR/D lighting. Petals were inoculated with TRV-PES for transient repression of PES, or with TRV as a control. Emission and internal pools, respectively, of individual compounds (A and C) and total emitted and accumulated volatiles (B and D) were analyzed by GC-MS. Data are means ± SEM (n = 3–6). The significance of differences between treatments was calculated using Student's t-test: *P ≤ 0.05.

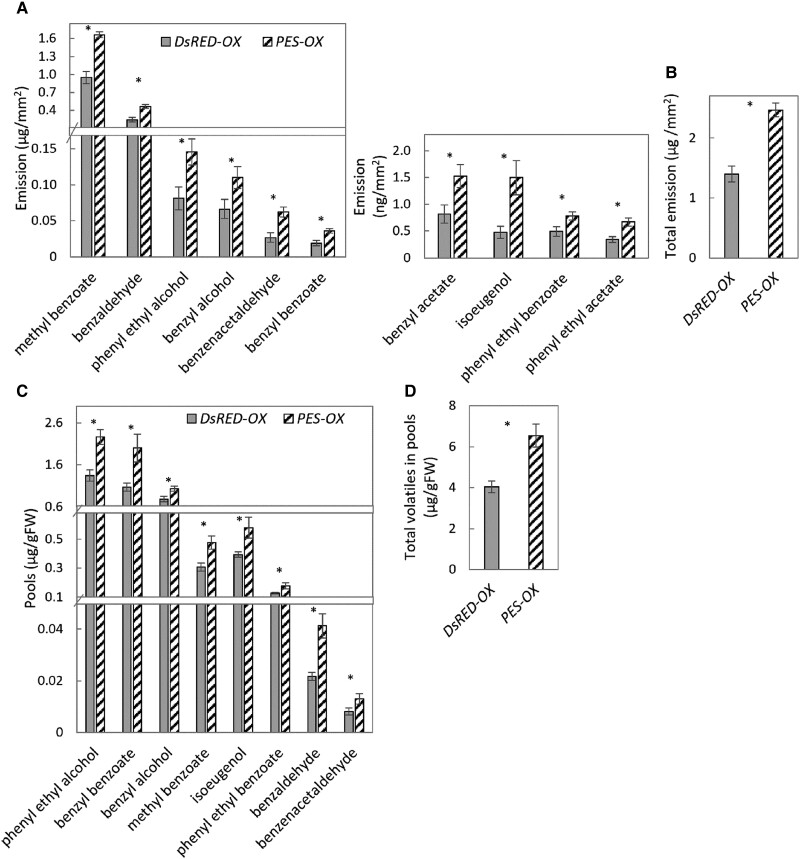

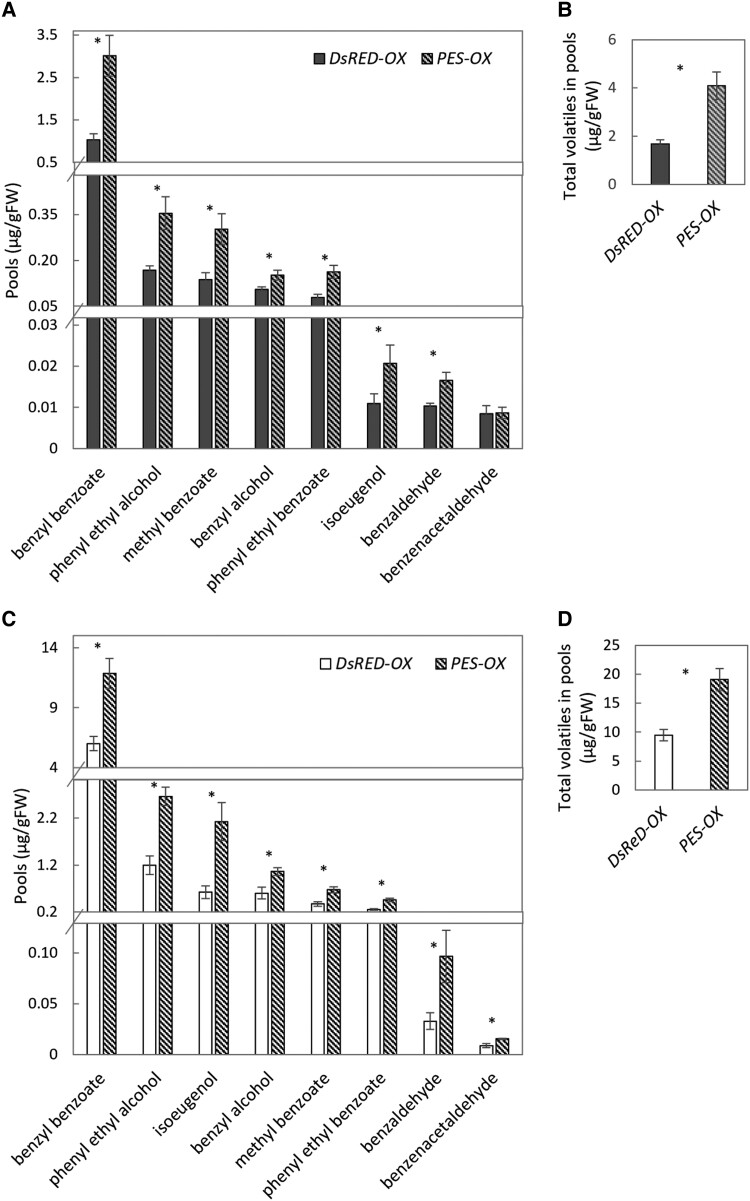

To further confirm the involvement of PES in regulation of floral scent production, it was transiently overexpressed in petals of petunia flowers. The petals were inoculated with Agrobacterium tumefaciens carrying a binary vector containing the coding DNA sequence (CDS) of PES under a 35S promoter for overexpression of PES (PES-OX), or 35S:DsRED as a control (DsRED-OX). Dynamic headspace analysis of the infiltrated regions showed that the total emission of volatiles, as well as emission of all of the main scent compounds, under FR/D light conditions, were significantly higher in PES-overexpressing tissues than in the DsRED-OX control (Fig. 3, A and B). Inoculated regions were also used for extraction of volatiles from the internal pools with subsequent measurement by GC-MS. Levels of all detected volatiles were higher in PES-OX petals (Fig. 3, C and D), further confirming the involvement of PES in the positive regulation of petunia floral VOC production.

Figure 3.

Overexpression of PES enhances emission and accumulation of volatiles in petunia petals under FR/D lighting. Petals were inoculated with Agrobacterium carrying a binary vector with 35S:PES for transient overexpression of PES (PES-OX), or with 35S:DsRED as a control (DsRED-OX). A and B) Emission levels of volatiles. A) Individual compounds. B) Total emission. C and D) Levels of internal pools. C) Individual compounds. D) Total pools. Data are means ± SEM (n = 6–9). The significance of differences between treatments was calculated using Student's t-test: *P ≤ 0.05.

PES upregulates transcript levels of the major VOC-related genes and activates promoters of ODO1, PAAS, and IGS

Analyses of the effect of PES overexpression on transcript levels of scent-related genes (Supplemental Fig. S3) revealed PES-activated expression of the biosynthetic genes from the phenylpropanoid pathway—PAAS, 4CL, BSMT, CFAT, and IGS, the shikimate pathway gene EPSPS, and the positive regulator of scent production—the transcription factor ODO1 (Fig. 4, A and B). Suppression of PES led to downregulation of these genes: the levels of EPSPS, PAAS, 4CL, BSMT, CFAT, IGS, and ODO1 were significantly lower in TRV-PES compared to the TRV control (Supplemental Fig. S4).

Figure 4.

Overexpression of PES activates expression of scent-related genes in petunia flowers. A) Transcript levels of phenylpropanoid/benzenoid-biosynthesis genes and regulators and B) PES in petal tissues transiently overexpressing PES (PES-OX), or DsRED (DsRED-OX) as a control, under FR/D lighting. Samples collected at 19.00. EF1α was used as an internal reference gene. Data are means ± SEM (n = 3–6). C) ODO1 promoter is activated by PES. Expression levels of GUS and PES in petals inoculated with ODO1pro:GUS, 35S:YFP and 35S:PES (PES-OX) or 35S:DsRED (DsRED-OX) as a control. YFP was used as a normalization factor. Data are means ± SEM (n = 5–6). D) PES activates PAAS and IGS promoters. Flowers infiltrated with Agrobacterium carrying PAASpro:DsRED or IGSpro:DsRED with or without 35S:PES (+PES and −PES, respectively) together with 35Spro:YFP, used for normalization, were imaged using DsRED and YFP filters, and DsRED/YFP ratio calculated. Data are means ± SEM (n = 15–35). The significance of the differences between treatments was calculated using Student's t-test: *P ≤ 0.05.

To evaluate the ability of PES to activate the ODO1 promoter, petunia petals were co-infiltrated with Agrobacterium, carrying the GUS reporter gene driven by the ODO1 promoter (ODO1pro:GUS; Van Moerkercke et al. 2011), 35S:YFP, and 35S:PES (PES-OX) or 35S:DsRED (DsRED-OX) as a control. Levels of GUS, which are indicative of ODO1 promoter activation, were evaluated in co-inoculated tissues by RT-qPCR. YFP levels were used for normalization (Fig. 4C). GUS transcript levels were significantly higher in petals overexpressing PES than in DsRED-OX-infiltrated petals, suggesting transcriptional activation of ODO1 by PES.

We also tested whether the promoters of the genes encoding the biosynthetic enzymes PAAS and IGS could be activated by PES. Petal tissues were agroinfiltrated with the coding sequence of DsRED fluorescent protein under PAAS (PAASpro) or IGS (IGSpro) promoters with or without 35S:PES (+PES and −PES, respectively) and 35Spro:YFP, used for normalization. The DsRED fluorescence signal was significantly higher in both PES-overexpressing tissues—PAASpro:DsRED and IGSpro:DsRED (Fig. 4D), suggesting that these genes are transcriptionally regulated by PES. Interestingly, the magnitudes of the change in their promoter activities (1.5 and 1.4 times, respectively) matched the increase in mRNA levels of PAAS and IGS in PES-overexpressing tissues (Fig. 4A).

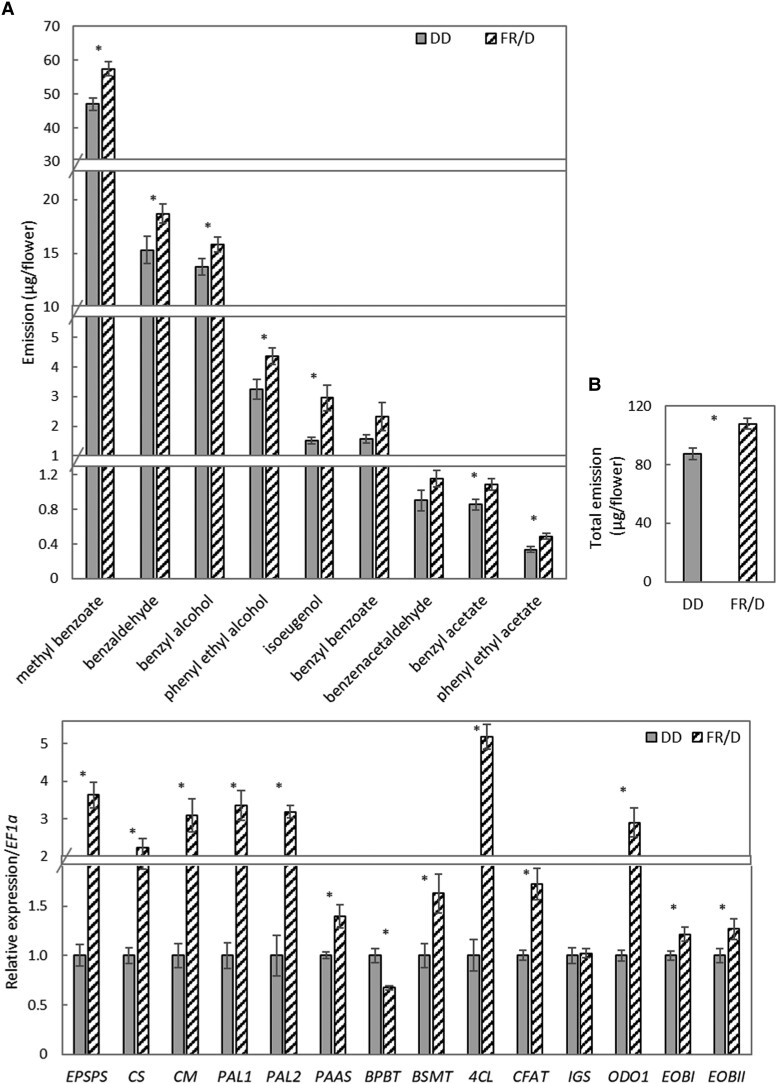

FR light positively affects scent production in Petunia flowers

The PES homolog AtPAT is involved in the FR-specific phenotype (Bolle et al. 2000; Torres-Galea et al. 2013) and PES affects VOC production under FR light; we, therefore, examined the effect of FR light on floral scent. Petunia flowers were removed from plants growing in a greenhouse under a 16-h light/8-h dark photoperiod, and placed under FR/D (the same photoperiod) or DD conditions at 1,600 h (ZT 10). Dynamic headspace collection of the emitted volatiles was initiated 1 h later. GC-MS analyses of the collected volatiles revealed that total scent emission, as well as the emission of most of the scent compounds (except for benzyl benzoate and benzeneacetaldehyde), were significantly higher under FR/D vs. DD conditions (Fig. 5, A and B). RT-qPCR analysis was performed to assess the effect of FR/D conditions on floral scent-related gene expression (Fig. 5C). Transcript levels of genes from the shikimate pathway—EPSPS, CS, and CM, and the phenylpropanoid pathway—PAAS, PAL1, PAL2, BSMT, 4CL, and CFAT were significantly higher under FR/D compared to DD conditions. Unlike all of the other tested scent-related genes, which were affected by FR light, transcript levels of IGS did not change, and BPBT was downregulated. Regulators of the phenylpropanoid pathway—ODO1, EOBI, and EOBII—were upregulated under FR/D compared to DD.

Figure 5.

FR light activates scent emission and production in petunia flowers. Volatiles were collected from flowers at anthesis and placed under DD or FR/D lighting. A and B) Emission levels of volatiles. A) Individual compounds. B) Total emission. Data are means ± SEM (n = 4–12). C) Expression of scent-related genes. Samples were collected at 1,600 h. EF1α was used as an internal reference gene. Data are means ± SEM (n = 4–6); *P ≤ 0.05 by Student's t-test.

Scent production under FR light is activated via PHYA

PHYA is known as a photoreceptor that provides physiological responses under prolonged FR irradiation (Bae and Choi 2008; Casal et al. 2014). To assay PHYA's involvement in the activation of floral scent under FR light, we first identified petunia PHYA (PhPHYA). Four transcripts similar to AtPHYA (AT1G09570) were revealed based on tBLASTx against the P. hybrida var. Mitchell transcriptome database, Sol Genomics network (https://solgenomics.net/). Their nucleotide sequences and the CDSs of major Arabidopsis phytochromes were aligned, and a phylogenetic tree was generated (Supplemental Fig. S5A). The transcript comp45201, corresponding to Peaxi162Scf00035g00513 in the P. axillaris genome, was closest to AtPHYA. Pairwise protein sequence alignment of comp45201 and AtPHYA, using the Needleman–Wunsch algorithm, showed 78.6% identity and 90% similarity (Supplemental Fig. S5B). In addition, reciprocal BLAST (tBLASTx) of the Arabidopsis PHYA against the P. axillaris genome detected Peaxi162Scf00035g00513 as the top hit (79% identity), named here PhPHYA.

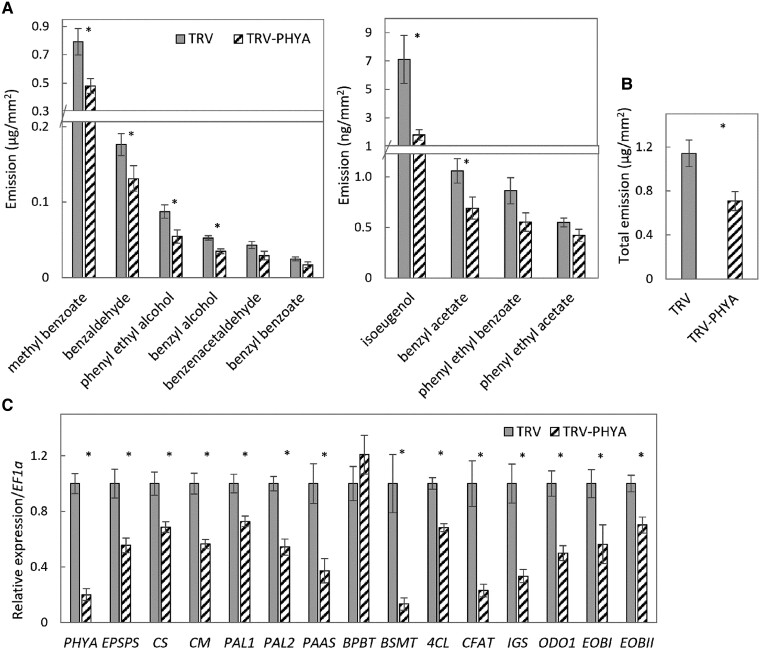

To assay the effect of PhPHYA on the emission of volatiles, we transiently suppressed its expression in petunia petals using TRV. The pTRV2 plasmid, with or without a fragment of the PhPHYA gene (TRV-PHYA or TRV, respectively), was delivered into petal tissue by agroinfiltration. Localized dynamic headspace in the inoculated regions with subsequent GC-MS analysis of the volatiles were performed under FR/D lighting (Fig. 6, A and B). Inoculation of petals with TRV-PHYA, as compared to control TRV, resulted in decreased levels of volatile scent compounds, leading to a significant decrease in total VOC emission and indicating involvement of PhPHYA in the production of scent volatiles in petunia petals. Infiltration with TRV-PHYA led to a decrease in the expression of PHYA, as expected, and of the genes encoding major enzymes participating in the biosynthesis of VOCs and their precursors—EPSPS, CS, CM, PAAS, PAL1, PAL2, BSMT, 4CL, CFAT, and IGS. BPBT did not reveal any sensitivity to PhPHYA suppression under FR light. Regulators of volatile biosynthesis, ODO1, EOBI, and EOBII, were also downregulated in TRV-PHYA (Fig. 6C). Thus, PhPHYA positively affects VOCs under FR light, supporting the idea that FR light activates scent via PHYA.

Figure 6.

PhPHYA suppression decreases scent emission from petunia petals under FR/D light conditions. Flowers at anthesis were inoculated with TRV-PHYA for transient suppression of PhPHYA, or with TRV as a control. A) Emission of separate scent compounds. B) Total volatile emission. Data are means ± SEM (n = 5–7). C) Expression levels of PhPHYA and scent-related genes. Samples were collected at 1,600 h. EF1α was used as an internal reference gene. Data are means ± SEM (n = 4–6); *P ≤ 0.05 by Student's t-test.

Activation of floral scent by PES is not restricted to FR light

The Arabidopsis homolog of PES, AtPAT1, has been shown to regulate physiological responses only under FR light, and not in the dark or under white light (Bolle et al. 2000). We checked whether the effect of PES overexpression, detected under FR light, is responsive only to FR light or is more general. Flowers transiently overexpressing PES (PES-OX) or DsRED (DsRED-OX) as a control were placed in DD or under white light/dark (WL/D) conditions, and volatiles accumulated in the internal pools were measured. Volatiles accumulated to 5 times higher levels under WL/D vs. DD, in both PES-OX and DsRED-OX control petals. PES overexpression caused a two-fold increase in the levels of scent compounds in the pools under both DD and WL/D conditions (Fig. 7). Similarly, levels of emitted compounds were significantly higher in PES-OX vs. DsRED-OX control petals under DD and WL/D conditions (Fig. 8). The fold increase in the levels of emitted and accumulated volatiles following PES overexpression under WL and DD conditions was not significantly different from that under FR/D conditions (Supplemental Fig. S6). Taken together, these data suggest that PES acts as a scent activator and that its effect is not limited to FR light conditions. Furthermore, no effect of light condition (DD vs. FR/D) on the PES mRNA level was detected (Supplemental Fig. S7A); while there was also no effect of PHYA suppression on PES (Supplemental Fig. S7B), this does not exclude the possibility of FR light regulation of PES post transcriptional levels.

Figure 7.

Activating effect of PES overexpression on accumulation of volatiles in internal pools under DD and WL/D conditions. Scent volatiles were analyzed in petals transiently overexpressing PES (PES-OX) or DsRED (DsRED-OX) as a control. Agroinfiltrated flowers were placed under DD (A and B) or under WL/D conditions (C and D), and samples were collected 24 h later. A and C) Individual scent compounds accumulated in internal pools. B and D) Total volatiles in internal pools. Data are means ± SEM (n = 5–8); *P ≤ 0.05 by Student's t-test.

Figure 8.

PES overexpression increases emission of floral volatiles under DD and WL/D conditions. VOCs, emitted from petals transiently overexpressing PES (PES-OX) or DsRED (DsRED-OX) as a control, were analyzed. A and B) Agroinfiltrated flowers were placed under DD or C and D, under WL/D conditions, and localized headspace was initiated 24 h later. A and C) Individual emitted scent compounds. B and D) Total emitted volatiles. Data are means ± SEM (n = 7–8); *P ≤ 0.05 by Student's t-test.

Discussion

Biosynthesis of scent volatiles is a multistep and energetically expensive enzymatic process, which requires the flow of carbohydrates and amino acids from primary to specialized metabolism, and is therefore tightly regulated in plants (Colquhoun and Clark 2011; Oyama-Okubo et al. 2013). The biochemical steps leading to the production of petunia scent compounds are well characterized: intermediate products and genes encoding enzymes catalyzing the main points of the shikimate and phenylpropanoid pathways have been revealed (Pichersky and Dudareva 2007; Muhlemann et al. 2014). Coordinated regulation of different branches and metabolic fluxes within the pathways results in synchronized emission patterns of various volatiles following day/night cycles, throughout flower development, in different environmental settings (Dudareva and Pichersky 2006; Colquhoun and Clark 2011; Cna’ani et al. 2015; Fenske et al. 2015; Ravid et al. 2017).

In contrast, the regulatory effects of external factors, with light being one of the most important signals for the plant, on the biosynthesis of petunia floral volatiles have not been studied in depth. The primary metabolism providing substrates for VOC production is determined by light conditions (Florez-Sarasa et al. 2012; Skirycz et al. 2022). Specialized metabolism—synthesis and accumulation of anthocyanins, carotenoids and flavonols—is also sensitive to light quality, light quantity, and photoperiodism (Thoma et al. 2020). White light positively affects the biosynthesis of the major VOCs in petunia petals compared to dark conditions (Fenske et al. 2015), as also confirmed in the current study (Figs. 7 and 8). The hypothesis that light of different wavelengths can affect the quality and quantity of volatiles has been previously tested in different plant species. Light treatments at specific wavelengths were found to affect the emission of terpenoid volatiles from the leaves of sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum) (Carvalho et al. 2016). Terpenoid VOCs were also affected in Arabidopsis and young barley (Hordeum vulgare) plants under shading, sensed by the plant as a decrease in the R-to-FR light ratio (Kegge et al. 2013, 2015). A study of light quality effects on VOC emission from petunia flowers was initiated by Colquhoun et al. (2013). In those short-term headspace experiments, where the scent compounds were collected for 1 h, FR light induced an increase in the emission of phenylethyl alcohol, benzyl alcohol, benzenacetaldehyde, methyl benzoate, and benzyl benzoate. It seems, therefore, that in addition to light being an important factor in plant growth and development, the FR spectral range can also play a role in the regulation of volatile emissions in different organs, including volatile production in petunia petals. In this study, we detailed the effect of FR light on petunia floral scent emission and production. Flowers placed under FR light showed a marked increase in the levels of most analyzed volatiles, as compared to flowers kept in the dark. This positive effect could be attributed to increased expression of the genes encoding the key enzymes of the shikimate and phenylpropanoid pathways, involved in the biosynthesis of the petunia floral volatiles EPSPS, CS, CM, PAAS, PAL, BSMT, 4CL, and CFAT (Fig. 5). While the level of BPBT transcript was lower under FR vs. DD conditions, emission of benzyl benzoate, synthesized in a BPBT-driven reaction, was not reduced; this can probably be attributed to the higher availability of substrates for the reaction. It can be further suggested that the link between the external light-signal cue and upregulation of the pathways is mediated by the elevated expression of transcriptional activators of VOC biosynthesis—ODO1, EOBI, and EOBII (Fig. 5). An almost 3-fold increase in ODO1 mRNA level in response to FR light conditions corresponds to the 3-fold increase in EPSPS, CM, PAL1, and PAL2, which are known to be activated by ODO1 (Verdonk et al. 2005; Boersma et al. 2022). The increase of EOBI and EOBII transcript levels was less prominent (20%–30%), highlighting complex relationships between the regulators.

Seed plants sense R/FR light signals via the phytochrome photoreceptors, which form 3 clades—PHYA, PHYB/E, and PHYC (Mathews 2010; Li et al. 2015). PHYA acts primarily as an FR light sensor (Sheerin and Hiltbrunner 2017). In this work, we revealed that PhPHYA positively affects the production of floral scent compounds under FR light. Silencing of PhPHYA led to a significant decrease in most volatiles in petunia flowers, as well as a decrease in the expression of genes encoding the key phenylpropanoid/benzenoid-biosynthesis enzymes and regulators of the pathway (Fig. 6). The level of IGS decreased and that of BPBT did not change in response to PhPHYA suppression. The observation that FR light did not affect IGS and led to a reduction in BPBT suggests that other factors affected by FR light fine-tune the steady-state levels of these transcripts.

Our results thus revealed the involvement of PHYA in VOC production/emission, supporting previous findings where the FR light photoreceptor was an activator of another branch of the phenylpropanoid pathway that yields anthocyanins. There, a regulatory role for FR light and PHYA on anthocyanins in different tissues of young plants was shown in several species. Hypocotyls of tomato phyA mutants exhibited decreased anthocyanin accumulation under prolonged FR irradiation (Kerckhoffs et al. 1997). Constant far-red (cFR) light caused accumulation of anthocyanins in maize (Zea mays) coleoptiles, compared to dark conditions. Moreover, overexpression of PHYA in rice resulted in higher anthocyanin content than in the wild type under cFR (Casal et al. 1996). In Arabidopsis mutants, PHYA was shown to be the crucial photoreceptor for the induction of anthocyanin accumulation in seedlings grown under FR light (Neff and Chory 1998; Warnasooriya et al. 2011).

In plants, FR light serves as an indicator of time, e.g. dusk, when the R/FR ratio decreases compared to midday (Neff et al. 2000). Seaton et al. (2018) considered PHYA to be a dawn-sensing photoreceptor, based on meta-analysis of functional genomic datasets and mathematical modeling. It is possible that PHYA is involved in sensing both dawn and dusk, depending on the quality and quantity of the light and on the concurrent state of the light-dependent molecular environment; this might cause different downstream effects at the beginning of the day when darkness is replaced by light, and at the end of the day, when FR-enriched light is replaced by darkness, to switch daily changing processes on and off. Petunia var. Mitchell emits scent in the late evening and during the night (Spitzer-Rimon et al. 2010; Fenske et al. 2015), in accordance with the activity of its pollinator, the nocturnal Manduca spp. moth (Fenske et al. 2018). Activation of scent production by FR light via PHYA might be part of the mechanism activating VOC production in the evening. Thus, integration of light as an external time signal with the internal timekeeper (circadian clock) (Fenske et al. 2015) may lead to tight control of volatile production while the pollinators are active.

The core molecular mechanism providing regulation of VOC production at the transcriptional level consists of MYB family transcription factors ODO1, EOBI, and EOBII, which coordinate the expression of biosynthetic genes and of each other (Verdonk et al. 2005; Spitzer-Rimon et al. 2010, 2012). They activate the expression of genes in both the phenylpropanoid and shikimate pathways. Other regulators identified to date with known mechanisms of action, LHY and PhERF6, work through ODO1. The exception is PhMYB4, which affects the coumaric acid branch of the pathway via C4H (Colquhoun et al. 2011; Fenske et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2017). In this work, we identified and investigated an additional factor involved in the regulation of floral scent, which we termed PES. This factor was shown to positively affect scent via upregulation of the genes encoding shikimate- and phenylpropanoid-biosynthesis enzymes, acting at least in part through activation of ODO1 (Fig. 4). Overexpression of PES led to a ca. 40% increase in ODO1 and a similar increase in EPSPS mRNA levels, in accordance with the previously demonstrated ability of ODO1 to directly activate the EPSPS promoter (Verdonk et al. 2005). Upregulation of ODO1, as well as of PAAS and IGS, was shown to be at the transcriptional level. While the IGS promoter was previously shown to be activated by EOBI and II (Spitzer-Rimon et al. 2010, 2012), no transcriptional regulator of PAAS had been identified. In addition, activation of IGS is probably not through EOBs as their levels were not significantly affected by PES overexpression. We did not observe any increase in the levels of PAL or CM transcripts following overexpression of PES, as might be expected based on the results revealed in ODO1-RNAi-suppressed plants (Verdonk et al. 2005; Boersma et al. 2022). The effect of increased ODO1 levels might differ from those predicted based on RNAi-suppressed lines; e.g. there might be other factors interfering with the accumulation of PAL and CM transcripts in the PES-overexpressing petals.

PES is a SCL GRAS domain protein and like other SCLs, has leucine-rich motifs (Pysh et al. 1999). These sequences are well-documented for their involvement in protein–protein interactions including homo- and heterodimerization, and interaction with transcription factors. Since the DNA-binding ability of GRAS proteins is still under debate (Hakoshima 2018), it is possible that PES is also part of a protein complex that activates target genes.

A regulatory role for GRAS proteins in scent production has been shown for DELLA, which negatively controls gibberellin (GA) signal transduction (Ravid et al. 2017). GA generated by stamens, as well as treatment with exogenous GA, significantly reduced VOC production in petals. Accordingly, suppression of PhDELLA1,2 led to decreased mRNA levels of scent-related genes and reduced VOC levels. PES homolog in Arabidopsis, PAT1, was shown to be involved in the response to FR light such as inhibition of hypocotyl elongation (Bolle et al. 2000; Torres-Galea et al. 2013). This led us to propose that its involvement in scent production is also FR-light-dependent. However, PES activation of VOC production was not restricted to FR light conditions, as it was also observed in petals overexpressing PES under WL/D conditions and in DD (Figs. 7 and 8). At this stage, we cannot exclude the possibility that the effect of PES on scent production is light-related when expressed at native levels, as opposed to the ectopic overexpression tested here. We also cannot exclude the possibility of PES's involvement in the mediation of FR light signals during de-etiolation, as has been demonstrated for Arabidopsis PAT1. The effect of the pat1 mutation on specialized metabolism that may be flower-specific was not tested in Arabidopsis. It is possible that, together with the described classical phenotypes for plants with FR-signaling deficiency (Bolle et al. 2000; Torres-Galea et al. 2013), Arabidopsis mutants will also reveal light-independent effects on phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Indeed, there is evidence of AtPAT1 involvement in the regulatory network of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Large-scale protein–DNA interaction screening by Y1H assay, performed to identify transcription factors that might interfere with cell wall formation, detected AtPAT1 as a putative regulator of flavonoids and lignin formation (Taylor-Teeples et al. 2015). Moreover, cross-species analysis of GRAS transcription factors, based on public transcriptome datasets, revealed involvement of GRASs in flavonoid biosynthesis (Liu et al. 2021). Analysis of the transcriptome of transgenic grapevine (Vitis amurensis) callus revealed that the expression of several genes involved in phenylpropanoid and lignin biosynthesis is affected by overexpression of the grapevine VaPAT1(Wang et al. 2021).

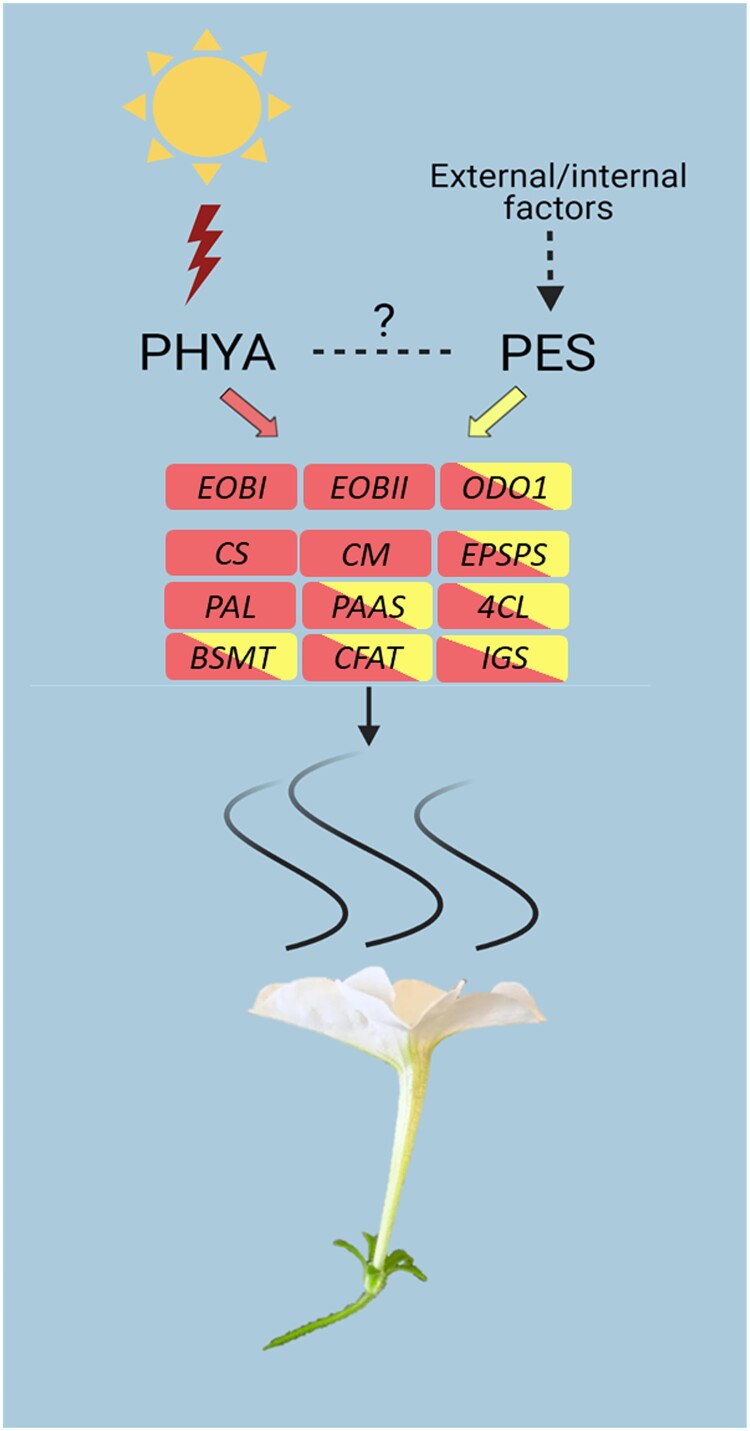

The scheme in Fig. 9 illustrates the findings revealing involvement of FR light in petunia flower scent production, including upregulation of major scent-related genes through the photoreceptor PHYA. PES—a regulator of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis in petunia petals—activates the production of scent volatiles by influencing transcription of the core pathway regulator ODO1 and biosynthesis genes. We hypothesize that it can act as a transmitter of environmental or internal signals to the VOC-biosynthesis machinery. The homology of PES to the Arabidopsis protein, which is known to be involved in FR-light signaling, inclines us to expect some interaction between PHYA and PES, but whether and how FR light or PHYA, or both, affect PES remain unclear.

Figure 9.

A proposed model showing involvement of FR light and PES protein in regulation of petunia floral scent. PES and PHYA act as positive transcriptional regulators of scent production in petunia flowers. Scent-related genes activated by PHYA are shown in red, and those activated by both PHYA and PES in red/yellow. Dashed arrows represent hypothetical interactions. PES, PHENYLPROPANOID EMISSION-REGULATING SCARECROW-LIKE; PHYA, PHYTOCHROME A; EOBI and II, EMISSION OF BENZENOIDS I and II; ODO1, ODORANT1; CS, CHORISMATE SYNTHASE; CM, CHORISMATE MUTASE; EPSPS, 5-ENOL-PYRUVYLSHIKIMATE-3-PHOSPHATE SYNTHASE; PAL, L-PHENYLALANINE AMMONIA LYASE; PAAS, PHENYLACETALDEHYDE SYNTHASE; BSMT, S-ADENOSYL-L-METHIONINE:BENZOIC ACID/SALICYLIC ACID CARBOXYL METHYLTRANSFERASE; 4CL, 4-COUMARATE:CoA LIGASE; CFAT, CONIFERYL ALCOHOL ACETYLTRANSFERASE; IGS, ISOEUGENOL SYNTHASE.

Materials and methods

Plant material

Petunia (P. hybrida) line Mitchell diploid (W115) was grown in a glasshouse under 25 °C d/20 °C night temperatures with a 16-h light/8-h dark photoperiod. For emitted volatile measurements, and sampling for internal pools and RNA extraction, flowers at anthesis or 1-d post anthesis (dpa; for transient repression and overexpression) were detached from the plants and placed into a growth chamber (Percival, USA), 22 °C, under the specified light conditions: DD, FR/D (FR 20 μmol m−2 s−2) or WL/D (WL 170 μmol m−2 s−2), under a 16-h light/8-h dark photoperiod. Light for all experiments was provided by light-emitting diodes (LED30-HL1). The wavelengths used were FR (730 ± 10 nm bandwidth) and WL (400–680 nm). The experiments were performed 3–4 times with similar results.

Transient repression of PES and PhPHYA using TRV vectors

Local transient VIGS was performed using TRV. To generate pTRV2-PES, 296 bp of the petunia PES 3′UTR was amplified from cDNA using 5′-ATGGATCCGAATGCTACAATC-3′, 5′-ATGAATTCTCTTTGATTGATCA-3′ primers and inserted into pTRV2 between BamhI and EcoRI restriction sites. To generate pTRV2-PHYA, 278 bp of the 3′ region of the PhPHYA CDS was amplified using 5′-AAGAGCTCGCTAGCAGGGATGTTCGAGA-3′ and 5′-AATCTAGACAAGCTGTCTGTGTCCCAAA-3′ primers was cloned into pTRV2 between SacI and XbaI restriction sites. A. tumefaciens strain AGLO was transformed with the obtained vectors and inoculated into petals of flowers at anthesis. The Agrobacterium culture was grown overnight at 28 °C in Luria-Bertani medium with 50 mg l−1 kanamycin and 200 μM acetosyringone. Cells were harvested and resuspended in inoculation buffer containing 10 mM MES, pH 5.5, 200 μM acetosyringone, and 10 mM MgCl2. Bacteria containing pTRV1 were mixed with those containing pTRV2 and its derivatives in a 1:1 ratio and used for injection into petunia petals. Inoculated regions were used for localized headspace sampling, volatile extraction from pools, and RNA extraction.

Transient overexpression of PES

For overexpression of PES, the CDS was amplified from petunia cDNA and cloned into a binary vector under a 35S promoter using the GoldenBraid cloning system (Sarrion-Perdigones et al. 2013). Agrobacterium AGLO carrying pDGB3α1::35Spro:PES or pDGB3α2:35Spro:DsRED (control) was inoculated into petals at anthesis. Agroinfiltrated regions were used for the experiments.

Collection of emitted and accumulated volatiles and GC-MS analysis

For dynamic headspace analyses of emitted scent compounds, petunia flowers at 1 dpa were placed under the specified light conditions, and volatile compound collection was initiated 24 h later (at 2 dpa) unless otherwise stated. As petunia var. Mitchell, which is pollinated by a nocturnal moth, emits scent at night (Spitzer-Rimon et al. 2010; Fenske et al. 2015), emitted scent volatiles were collected overnight—from the evening (1,700 h) till the morning of the next day (1,000 h). Emitted volatiles were collected from 2 flowers, placed into jars (for analyses of FR light's effect on the emission of volatiles) or from the petal regions inoculated with Agrobacterium suspension by “localized headspace” (Skaliter et al. 2021). Glass tubes containing 100 mg Porapak Type Q polymer held in place with a plug of silanized glass wool were used as columns. Volatiles were eluted from the columns using 1.35 ml hexane + 0.45 ml acetone, and 2 μg isobutylbenzene was added to each sample as an internal standard, followed by GC-MS analysis.

To determine the sizes of the VOC pools, samples were collected from agroinfiltrated petal regions. Flowers, agroinfiltrated at anthesis, were placed under the specified light conditions of 1 dpa. Samples of 2 dpa flowers were collected for extraction of volatiles from internal pools at 1,900–1,930 h (ZT 13–13.5), 3 h before onset of the dark phase, when a certain level of VOCs has already been synthesized, but before the time of highest emission (Cna’ani et al. 2017). Frozen tissue was ground in liquid nitrogen and extracted in 400 μl hexane containing 0.064 μg of isobutylbenzene as the internal standard. Following 2 h of incubation with gentle shaking at 25 °C, extracts were centrifuged at 10,500 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was used for GC-MS analysis.

GC-MS analysis (of a 1-μl sample) was performed using a device consisting of a PAL autosampler (CTC Analytics), a TRACE GC 2000 gas chromatograph (ThermoFisher Scientific), equipped with an Rtx-5SIL mass spectrometer fused-silica capillary column (inner diameter 0.25 μm, 30 m × 0.25 mm; Restek), and a TRACE DSQ quadruple mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1. The injector temperature was set to 220 °C (splitless mode) and the interface to 240 °C, and the ion source was adjusted to 200 °C. The analysis was performed under the following temperature program: 2 min of isothermal heating at 40 °C followed by a 7 °C min−1 oven temperature ramp to 250 °C then 2 min of isothermal heating. The system was equilibrated for 1 min at 70 °C before injecting the next sample. Mass spectra were recorded at 3.15 scans s−1 with a scanning range of 40–350 mass-to-charge ratio and electron energy of 70 eV. Compounds were tentatively identified (>95% match) based on NIST/EPA/NIH Mass Spectral Library data version NIST 05 (with software version 2.0d) using Xcalibur 1.3 (ThermoFisher Scientific). Further identification of major compounds was based on a comparison of mass spectra and retention times with those of authentic standards (Sigma-Aldrich) analyzed under similar conditions.

Gene expression analysis

For the gene expression analysis, 1 dpa flowers were placed under the specified light conditions 24 h prior to sampling. Petal tissues were collected for RNA extraction 2 dpa at 1,600 h (ZT 10) for FR/PHYA experiments. For experiments with PES, samples were collected at 1,900 h (ZT 13) when the effect of PES overexpression and suppression on scent-related genes was stronger. For analysis of EOBI and EOBII, samples were collected at 1,100–1,130 h (ZT 5–5.5) because expression of these regulators is low in the evening (Spitzer-Rimon et al. 2010, 2012; Fenske et al. 2015). Total RNA was extracted from 30 mg of ground (with liquid nitrogen) petal tissue using the Tri-Reagent kit (Sigma-Aldrich) and treated with Rnase-free DNase I (ThermoFisher Scientific). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using 1 μg of total RNA, oligo(dT) primer, and reverse transcriptase ImProm-II (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed for 35 cycles (95 °C for 5 min and then 2 steps of cycling at 95 °C for 5 s, 60 °C for 35 s) in the presence of 2X qPCRBIO SyGreen Blue Mix Hi-ROX (PCR Biosystems) on a Rotor-Gene Q cycler (Qiagen). EF1α was used for normalization. Quantification calculations were carried out using the 2−ΔΔCT formula as described previously (Nozue et al. 2007). The primers are shown in Supplemental Table S1.

Promoter activation assays

To test activation of the ODO1 promoter by PES, Agrobacterium carrying GUS driven by the ODO1 1880-bp promoter fragment (ODO1pro:GUS) (Van Moerkercke et al. 2011) was co-inoculated into petunia petals at anthesis together with Agrobacterium carrying pART27::35Spro:YFP and pDGB3α1::35Spro:PES (PES-OX) or pDGB3α2::35Spro:DsRED (DsRED-OX). RNA was extracted from the infiltrated regions 72 h after inoculation, and GUS expression was evaluated by RT-qPCR. YFP was used as a control for normalization of RT-qPCR results. Activation of IGS and PAAS promoters by PES was tested by evaluating DsRED fluorescence levels in petals inoculated with Agrobacterium carrying pCGN1559-IGSpro:DsRED or pCGN1559-PAASpro:DsRED, together with pART27::35Spro:YFP and with or without pDGB3α1::35Spro:PES. PAASpro is a 560-bp region of Peaxi162Scf00561g00021, IGSpro is a 774-bp region of Peaxi162Scf00889g00229 (Supplemental Fig. S8); 72 h after infiltration, the inoculated regions were imaged using a fluorescent binocular microscope (FLOUIII; Leica) under UV light with DsRED and YFP filters, using the same exposure time for both filters. The levels of YFP and DsRED signals were measured by ImageJ software (Mean Gray Value), and used to evaluate relative DsRED fluorescence as DsRED/YFP ratio.

Bioinformatics analysis and tools

Phylogenetic trees, based on multiple sequence alignment, were constructed using MEGA11 (https://www.megasoftware.net/) (Tamura et al. 2021). The lists of A. thaliana, S. lycopersicum, and O. sativa GRAS proteins were obtained from Liu and Widmer (2014), and the sequences were downloaded from TAIR (https://www.arabidopsis.org/), Sol Genomics Network (https://solgenomics.net/), and Rice Genome Annotation Project (http://rice.uga.edu), respectively. Petunia GRAS proteins (Supplemental Table S2) were identified by TBLASTN of the petunia GRAS domain sequence against the CDS predicted from the P. axillaris genome (https://solgenomics.net/). Protein domains and motifs were identified by Saprolite tool https://prosite.expasy.org (de Castro et al. 2006). For pairwise protein sequence alignment, the Needleman–Wunsch algorithm was applied using the EMBOSS Needle package (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/psa/emboss_needle) and similarity was evaluated by BLOSUM62 matrix (Needleman and Wunsch 1970). To visualize the alignment results, the R package MSA was used (Bodenhofer et al. 2015).

Statistical analyses

For statistical analysis, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey HSD test and Student's t-test were applied.

Accession numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in Sol Genomics network (https://solgenomics.net/) under accession numbers Peaxi162Scf00776g00311 (PES) and Peaxi162Scf00035g00513(PhPHYA).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

A.V. is an incumbent of the Wolfson Chair in Floriculture. We thank Elena Shklarman and Orit Edelbaum for assistance with growing and propagation of plants.

Contributor Information

Ekaterina Shor, The Robert H. Smith Institute of Plant Sciences and Genetics in Agriculture, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Rehovot 76100, Israel.

Jasmin Ravid, The Robert H. Smith Institute of Plant Sciences and Genetics in Agriculture, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Rehovot 76100, Israel.

Elad Sharon, The Robert H. Smith Institute of Plant Sciences and Genetics in Agriculture, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Rehovot 76100, Israel.

Oded Skaliter, The Robert H. Smith Institute of Plant Sciences and Genetics in Agriculture, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Rehovot 76100, Israel.

Tania Masci, The Robert H. Smith Institute of Plant Sciences and Genetics in Agriculture, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Rehovot 76100, Israel.

Alexander Vainstein, The Robert H. Smith Institute of Plant Sciences and Genetics in Agriculture, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Rehovot 76100, Israel.

Author contributions

E.S. designed and performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the article. J.R., E.S., O.S., and T.M. performed the experiments. A.V. planned and designed the research and wrote the article.

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1 . Maximum likelihood tree based on degree of sequence similarity between P. axillaris (Peaxi), S. lycopersicum (Solyc), A. thaliana (At) and O. sativa (LOC_Os) GRAS proteins.

Supplemental Figure S2 . Protein sequence alignment of Petunia PES and its Arabidopsis ortholog PAT1.

Supplemental Figure S3 . A simplified scheme of the pathway and the major enzymes, leading to biosynthesis of phenylpropanoid-related VOCs.

Supplemental Figure S4 . Suppression of PES decreases transcript levels of the phenylpropanoid-biosynthesis enzymes.

Supplemental Figure S5 . Petunia putative orthologs of Arabidopsis phytochromes.

Supplemental Figure S6 . The increase in volatiles production in PES-OX vs. DsRED-OX infiltrated petals under DD, FR, and while/dark (WL) lightening conditions.

Supplemental Figure S7 . Expression of PES is not affected by DD vs. FR/D light conditions or by suppression of PHYA.

Supplemental Figure S8 . Nucleotide sequences of PAAS and IGS promoters, used for promoter activation assays.

Supplemental Table S1 . Primers used for qRT-PCR.

Supplemental Table S2 . P. axillaris GRAS proteins.

Funding

This work was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (grant no. 2511/16). ES was supported by the Lady Davis Fellowship Trust. Work in AV's laboratory is supported by the Chief Scientist of the Israel Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (no. 20-01-0209) as part of the National Center for Genome Editing in Agriculture.

References

- Albo B. Transcription factor EOB1: a key component in a network regulating production of phenylpropanoid scent compounds in petunia flowers [thesis]. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Rehovot, Israel. 2012.

- Bae G, Choi G. Decoding of light signals by plant phytochromes and their interacting proteins. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008:59(1):281–311. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch G, Bar-Shai N, Cytter Y, Green R. Time is honey: circadian clocks of bees and flowers and how their interactions may influence ecological communities. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2017:372(1734):20160256. 10.1098/rstb.2016.0256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boatright J, Negre F, Chen X, Kish CM, Wood B, Peel G, Orlova I, Gang D, Rhodes D, Dudareva N. Understanding in vivo benzenoid metabolism in petunia petal tissue. Plant Physiol. 2004:135(4):1993–2011. 10.1104/pp.104.045468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenhofer U, Bonatesta E, Horejš-Kainrath C, Hochreiter S. msa: an R package for multiple sequence alignment. Bioinformatics. 2015:31(24): 3997–3999. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boersma MR, Patrick RM, Jillings SL, Shaipulah NFM, Sun P, Haring MA, Dudareva N, Li Y, Schuurink RC. ODORANT1 targets multiple metabolic networks in petunia flowers. Plant J. 2022:109(5):1134–1151. 10.1111/tpj.15618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolle C. The role of GRAS proteins in plant signal transduction and development. Planta. 2004:218(5):683–692. 10.1007/s00425-004-1203-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolle C, Koncz C, Chua NH. PAT1, a new member of the GRAS family, is involved in phytochrome A signal transduction. Genes Dev. 2000:14(10):1269–1278. 10.1101/gad.14.10.1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombarely A, Moser M, Amrad A, Bao M, Bapaume L, Barry C S, Bliek M, Boersma M R, Borghi L, Bruggmann R.. Insight into the evolution of the Solanaceae from the parental genomes of Petunia hybrida. Nat Plants 2016:2:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandoli C, Petri C, Egea-Cortines M, Weiss J. The clock gene Gigantea 1 from Petunia hybrida coordinates vegetative growth and inflorescence architecture. Sci Rep. 2020:10(1):1–17. 10.1038/s41598-019-57145-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho SD, Schwieterman ML, Abrahan CE, Colquhoun TA, Folta KM. Light quality dependent changes in morphology, antioxidant capacity, and volatile production in sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum). Front Plant Sci. 2016:7(9):1328. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casal JJ, Candia AN, Sellaro R. Light perception and signalling by phytochrome A. J Exp Bot. 2014:65(11):2835–2845. 10.1093/jxb/ert379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casal JJ, Clough RC, Vierstra RD. High-irradiance responses induced by far-red light in grass seedlings of the wild type or overexpressing phytochrome A. Planta. 1996:200(1):132–137. 10.1007/BF00196660 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chapurlat E, Anderson J, Ågren J, Friberg M, Sletvold N. Diel pattern of floral scent emission matches the relative importance of diurnal and nocturnal pollinators in populations of Gymnadenia conopsea. Ann Bot. 2018:121(4):711–721. 10.1093/aob/mcx203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng MC, Kathare PK, Paik I, Huq E. Phytochrome signaling networks. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2021:72(1):217–244. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-080620-024221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cna’ani A, Mühlemann JK, Ravid J, Masci T, Klempien A, Nguyen TTH, Dudareva N, Pichersky E, Vainstein A. Petunia × hybrida floral scent production is negatively affected by high-temperature growth conditions. Plant Cell Environ. 2015:38(7):1333–1346. 10.1111/pce.12486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cna’ani A, Shavit R, Ravid J, Aravena-Calvo J, Skaliter O, Masci T, Vainstein A. Phenylpropanoid scent compounds in Petunia × hybrida are glycosylated and accumulate in vacuoles. Front Plant Sci. 2017:8(10): 1–14. 10.3389/fpls.2017.01898 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun TA, Clark DG. Unraveling the regulation of floral fragrance biosynthesis. Plant Signal Behav. 2011:6(3):378–381. 10.4161/psb.6.3.14339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun TA, Kim JY, Wedde AE, Levin LA, Schmitt KC, Schuurink RC, Clark DG. PhMYB4 fine-tunes the floral volatile signature of Petunia × hybrida through PhC4H. J Exp Bot. 2011:62(3):1133–1143. 10.1093/jxb/erq342 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun TA, Schwieterman ML, Gilbert JL, Jaworski EA, Langer KM, Jones CR, Rushing GV, Hunter TM, Olmstead J, Clark DG, et al. Light modulation of volatile organic compounds from petunia flowers and select fruits. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2013:86:37–44. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2013.06.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro E, Sigrist CJA, Gattiker A, Bulliard V, Langendijk-Genevaux PS, Gasteiger E, Bairoch A, Hulo N. Scanprosite: detection of PROSITE signature matches and ProRule-associated functional and structural residues in proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006:34(Web Server):W362–W365. 10.1093/nar/gkl124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudareva N, Pichersky E. Floral scent metabolic pathways: their regulation and evolution. In: Biology of Floral Scent, Vol. 1. 2006; CRC Press, pp. 55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Fenske MP, Hewett Hazelton KD, Hempton AK, Shim JS, Yamamoto BM, Riffell JA, Imaizumi T. Circadian clock gene LATE ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL directly regulates the timing of floral scent emission in petunia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015:112(31):9775–9780. 10.1073/pnas.1422875112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenske MP, Nguyen LP, Horn EK, Riffell JA, Imaizumi T. Circadian clocks of both plants and pollinators influence flower seeking behavior of the pollinator hawkmoth Manduca sexta. Sci Rep. 2018:8(1):2842. 10.1038/s41598-018-21251-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florez-Sarasa I, Araújo WL, Wallström S V, Rasmusson AG, Fernie AR, Ribas-Carbo M. Light-responsive metabolite and transcript levels are maintained following a dark-adaptation period in leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2012:195(1):136–148. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04153.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KA, Quail PH. Phytochrome functions in Arabidopsis development. J Exp Bot. 2010:61(1):11–24. 10.1093/jxb/erp304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakoshima T. Structural basis of the specific interactions of GRAS family proteins. FEBS Lett. 2018:592(4):489–501. 10.1002/1873-3468.12987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch S, Oldroyd GED. GRAS-domain transcription factors that regulate plant development. Plant Signal Behav. 2009:4(8):698–700. 10.4161/psb.4.8.9176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoballah ME, Stuurman J, Turlings TCJ, Guerin PM, Connétable S, Kuhlemeier C. The composition and timing of flower odour emission by wild Petunia axillaris coincide with the antennal perception and nocturnal activity of the pollinator Manduca sexta. Planta. 2005:222(1):141–150. 10.1007/s00425-005-1506-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann NR. A structure for plant-specific transcription factors: the gras domain revealed. Plant Cell. 2016:28(5):993–994. 10.1105/tpc.16.00309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegge W, Ninkovic V, Glinwood R, Welschen RAM, Voesenek LACJ, Pierik R. Red:far-red light conditions affect the emission of volatile organic compounds from barley (Hordeum vulgare), leading to altered biomass allocation in neighbouring plants. Ann Bot. 2015:115(6):961–970. 10.1093/aob/mcv036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegge W, Weldegergis BT, Soler R, Eijk MV-V, Dicke M, Voesenek LACJ, Pierik R. Canopy light cues affect emission of constitutive and methyl jasmonate-induced volatile organic compounds in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2013:200(3):861–874. 10.1111/nph.12407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerckhoffs LHJ, Schreuder MEL, Van Tuinen A, Koornneef M, Kendrick RE. Phytochrome control of anthocyanin biosynthesis in tomato seedlings: analysis using photomorphogenic mutants. Photochem Photobiol. 1997:65(2):374–381. 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1997.tb08573.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klempien A, Kaminaga Y, Qualley A, Nagegowda DA, Widhalm JR, Orlova I, Shasany AK, Taguchi G, Kish CM, Cooper BR, et al. Contribution of CoA ligases to benzenoid biosynthesis in petunia flowers. Plant Cell. 2012:24(5):2015–2030. 10.1105/tpc.112.097519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li FW, Melkonian M, Rothfels CJ, Villarreal JC, Stevenson DW, Graham SW, Wong GKS, Pryer KM, Mathews S. Phytochrome diversity in green plants and the origin of canonical plant phytochromes. Nat Commun. 2015:6(7):7852. 10.1038/ncomms8852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Zhao Y, Zhao Z, Wu X, Sun L, Liu Q, Wu Y. Crystal structure of the GRAS domain of SCARECROW-LIKE7 in Oryza sativa. Plant Cell. 2016:28(5):1025–1034. 10.1105/tpc.16.00018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Sun W, Li C, Yu G, Li J, Wang Y, Wang X. A multilayered cross-species analysis of GRAS transcription factors uncovered their functional networks in plant adaptation to the environment. J Adv Res. 2021:29:191–205. 10.1016/j.jare.2020.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Widmer A. Genome-wide comparative analysis of the GRAS gene family in populus, arabidopsis and rice. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2014:32(6):1129–1145. 10.1007/s11105-014-0721-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Xiao Z, Yang L, Chen Q, Shao L, Liu J, Yu Y. PhERF6, interacting with EOBI, negatively regulates fragrance biosynthesis in petunia flowers. New Phytol. 2017:215(4):1490–1502. 10.1111/nph.14675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JH, Dudareva N. Aromatic amino acids: a complex network ripe for future exploration. Trends Plant Sci. 2020:25(7):670–681. 10.1016/j.tplants.2020.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda H, Dudareva N. The shikimate pathway and aromatic amino acid biosynthesis in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2012:63(1):73–105. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda H, Shasany AK, Schnepp J, Orlova I, Taguchi G, Cooper BR, Rhodes D, Pichersky E, Dudareva N. RNAi suppression of Arogenate Dehydratase1 reveals that phenylalanine is synthesized predominantly via the arogenate pathway in petunia petals. Plant Cell. 2010:22(3):832–849. 10.1105/tpc.109.073247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews S. Evolutionary studies illuminate the structural-functional model of plant phytochromes. Plant Cell. 2010:22(1):4–16. 10.1105/tpc.109.072280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlemann JK, Klempien A, Dudareva N. Floral volatiles: from biosynthesis to function. Plant Cell Environ. 2014:37(8):1936–1949. 10.1111/pce.12314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagatani A, Reed JW, Chory J. Isolation and initial characterization of Arabidopsis mutants that are deficient in phytochrome A. Plant Physiol. 1993:102(1):269–277. 10.1104/pp.102.1.269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needleman SB, Wunsch CD. A general method applicable to the search for similarities in the amino acid sequence of two proteins. J Mol Biol. 1970:48(3):443–453. 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90057-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff MM, Chory J. Genetic interactions between phytochrome A, phytochrome B, and cryptochrome 1 during arabidopsis development. Plant Physiol. 1998:118(1):27–35. 10.1104/pp.118.1.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff MM, Fankhauser C, Chory J. Light: an indicator of time and place. Genes Dev. 2000:14(3):257–271. 10.1101/gad.14.3.257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozue K, Covington MF, Duek PD, Lorrain S, Fankhauser C, Harmer SL, Maloof JN. Rhythmic growth explained by coincidence between internal and external cues. Nature. 2007:448(7151):358–361. 10.1038/nature05946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyama-Okubo N, Sakai T, Ando T, Nakayama M, Soga T. Metabolome profiling of floral scent production in Petunia axillaris. Phytochemistry. 2013:90(6):37–42. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paik I, Huq E. Plant photoreceptors: multi-functional sensory proteins and their signaling networks. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2019:92(3): 114–121. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2019.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichersky E, Dudareva N. Scent engineering: toward the goal of controlling how flowers smell. Trends Biotechnol. 2007:25(3):105–110. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pysh LD, Wysocka-Diller JW, Camilleri C, Bouchez D, Benfey PN. The GRAS gene family in Arabidopsis: sequence characterization and basic expression analysis of the SCARECROW-LIKE genes. Plant J. 1999:18(1):111–119. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00431.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravid J, Spitzer-Rimon B, Takebayashi Y, Seo M, Cna’ani A, Aravena-Calvo J, Masci T, Farhi M, Vainstein A. GA as a regulatory link between the showy floral traits color and scent. New Phytol. 2017:215(1):411–422. 10.1111/nph.14504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrion-Perdigones A, Vazquez-Vilar M, Palací J, Castelijns B, Forment J, Ziarsolo P, Blanca J, Granell A, Orzaez D. Goldenbraid 2.0: a comprehensive DNA assembly framework for plant synthetic biology. Plant Physiol. 2013:162(3):1618–1631. 10.1104/pp.113.217661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer E, Bowler C. Phytochrome-mediated photoperception and signal transduction in higher plants. EMBO Rep. 2002:3(11):1042–1048. 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton DD, Toledo-Ortiz G, Ganpudi A, Kubota A, Imaizumi T, Halliday KJ. Dawn and photoperiod sensing by phytochrome A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018:115(41):10523–10528. 10.1073/pnas.1803398115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheerin DJ, Hiltbrunner A. Molecular mechanisms and ecological function of far-red light signalling. Plant Cell Environ. 2017:40(11):2509–2529. 10.1111/pce.12915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaliter O, Kitsberg Y, Sharon E, Shklarman E, Shor E, Masci T, Yue Y, Arien Y, Tabach Y, Shafir S, et al. Spatial patterning of scent in petunia corolla is discriminated by bees and involves the ABCG1 transporter. Plant J. 2021:106(6):1746–1758. 10.1111/tpj.15269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaliter O, Livneh Y, Agron S, Shafir S, Vainstein A. A whiff of the future: functions of phenylalanine-derived aroma compounds and advances in their industrial production. Plant Biotechnol J. 2022:20(9):1651–1669. 10.1111/pbi.13863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skirycz A, Caldana C, Fernie AR. Regulation of plant primary metabolism—how results from novel technologies are extending our understanding from classical targeted approaches. CRC Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2022:41(1):32–51. 10.1080/07352689.2022.2041948 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer-Rimon B, Farhi M, Albo B, Cna’ani A, Ben Zvi MM, Masci T, Edelbaum O, Yu Y, Shklarman E, Ovadis M, et al. The R2R3-MYB-like regulatory factor EOBI, acting downstream of EOBII, regulates scent production by activating ODO1 and structural scent-related genes in petunia. Plant Cell. 2012:24(12):5089–5105. 10.1105/tpc.112.105247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer-Rimon B, Marhevka E, Barkai O, Marton I, Edelbaum O, Masci T, Prathapani N-K, Shklarman E, Ovadis M, Vainstein A. EOBII, a gene encoding a flower-specific regulator of phenylpropanoid volatiles’ biosynthesis in petunia. Plant Cell. 2010:22(6):1961–1976. 10.1105/tpc.109.067280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer B, Zvi MMB, Ovadis M, Marhevka E, Barkai O, Edelbaum O, Marton I, Masci T, Alon M, Morin S, et al. Reverse genetics of floral scent: application of tobacco rattle virus-based gene silencing in petunia. Plant Physiol. 2007:145(4):1241–1250. 10.1104/pp.107.105916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Xue B, Jones WT, Rikkerink E, Dunker AK, Uversky VN. A functionally required unfoldome from the plant kingdom: intrinsically disordered N-terminal domains of GRAS proteins are involved in molecular recognition during plant development. Plant Mol Biol. 2011:77(3):205–223. 10.1007/s11103-011-9803-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano M, Kanegae H, Shinomura T, Miyao A, Hirochika H, Furuya M. Isolation and characterization of rice phytochrome A mutants. Plant Cell. 2001:13(3):521–534. 10.1105/tpc.13.3.521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol Biol Evol. 2021:38(7):3022–3027. 10.1093/molbev/msab120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Teeples M, Lin L, De Lucas M, Turco G, Toal TW, Gaudinier A, Young NF, Trabucco GM, Veling MT, Lamothe R, et al. An Arabidopsis gene regulatory network for secondary cell wall synthesis. Nature. 2015:517(7536):571–575. 10.1038/nature14099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry MI, Pérez-Sanz F, Díaz-Galián MV, de los Cobos FP, Navarro PJ, Egea-Cortines M, Weiss J. The petunia CHANEL gene is a ZEITLUPE ortholog coordinating growth and scent profiles. Cells. 2019:8(4):1–18. 10.3390/cells8040343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoma F, Somborn-Schulz A, Schlehuber D, Keuter V, Deerberg G. Effects of light on secondary metabolites in selected leafy greens: a review. Front Plant Sci. 2020:11(3):497. 10.3389/fpls.2020.00497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Galea P, Hirtreiter B, Bolle C. Two GRAS proteins, SCARECROW-LIKE21 and PHYTOCHROME A SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION1, function cooperatively in phytochrome A signal transduction. Plant Physiol. 2013:161(1):291–304. 10.1104/pp.112.206607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Moerkercke A, Haring MA, Schuurink RC. The transcription factor EMISSION of BENZENOIDS II activates the MYB ODORANT1 promoter at a MYB binding site specific for fragrant petunias. Plant J. 2011:67(5):917–928. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04644.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdonk JC, Haring MA, van Tunen AJ, Schuurink RC. ODORANT1 regulates fragrance biosynthesis in petunia flowers. Plant Cell. 2005:17(5):1612–1624. 10.1105/tpc.104.028837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Wong DCJ, Wang Y, Xu G, Ren C, Liu Y, Kuang Y, Fan P, Li S, Xin H, et al. GRAS-domain transcription factor PAT1 regulates jasmonic acid biosynthesis in grape cold stress response. Plant Physiol. 2021:186(3):1660–1678. 10.1093/plphys/kiab142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnasooriya SN, Porter KJ, Montgomery BL. Tissue- and isoform-specific phytochrome regulation of light-dependent anthocyanin accumulation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Signal Behav. 2011:6(5):624–631. 10.4161/psb.6.5.15084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.