Abstract

Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC) heat-stable enterotoxin 1 (EAST1) was originally discovered in EAEC but has also been associated with enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC). Multiple genomic restriction fragments from each of three ETEC strains of human origin showed homology with an EAST1 gene probe. A single hybridizing fragment was detected on the plasmid of ETEC strain 27D that also encodes heat-stable enterotoxin Ib and colonization factor antigen I. We isolated and characterized this fragment, showing that it (i) carries an allele of astA nearly identical to that originally reported from EAEC 17-2 and (ii) expressed enterotoxic activity. Sequence analysis of the toxin coding region revealed that astA is completely embedded within a 1,209-bp open reading frame (ORF1), whose coding sequence is on the same strand but in the −1 reading frame in reference to the toxin gene. In vitro expression of the predicted Mr-∼46,000 protein product of ORF1 was demonstrated. ORF1 is highly similar to transposase genes of IS285 from Yersinia pestis, IS1356 from Burkholderia cepacia, and ISRm3 from Rhizobium meliloti. It is bounded by 30-bp imperfect inverted repeat sequences and flanked by 8-bp direct repeats. Based on these structural features, pathognomonic of a regular insertion sequence, this element was designated IS1414. Preliminary experiments to show IS1414 translocation were unsuccessful. Overlapping genes of the type suggested by the IS1414 core region have heretofore not been described in bacteria. It seems to offer a most efficient mechanism for intragenomic and horizontal dissemination of EAST1.

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) strains are a major cause of secretory diarrhea in both humans and animals (4, 19). The basic pathogenic repertoire of ETEC includes species-specific surface adhesins that promote small intestinal colonization and enterotoxins that stimulate intestinal cell secretion (13, 24). These virulence determinants are often encoded on transmissible genetic elements (23, 40). Two types of enterotoxins are elaborated by ETEC, a heat-labile (LT) and a heat-stable (ST) toxin. STI is the more predominant of two different ETEC heat-stable enterotoxins (21) and causes fluid secretion by activating membrane-bound guanylyl cyclase C (38).

Enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) heat-stable enterotoxin 1 (EAST1) is a genetically distinct toxin that is structurally related to STI and also elevates intestinal cGMP levels (35, 36). Little is known about the pathogenic significance of EAST1 in diarrhea. In one case-control study, E. coli isolates that were genotypically positive for EAST1 were highly associated with diarrhea in Spanish children (43). It was notable that very few of the EAST1 E. coli isolates from this study hybridized with an aggregative adherence DNA probe. Three separate outbreaks of diarrhea linked to EAST1 E. coli have been reported. The index strain in a Minnesota outbreak was an O39:NM E. coli that expressed EAST1 and had the enteropathogenic E. coli gene locus for enterocyte effacement (17). In one Japanese report, an O nontypeable:H10 EAEC with a plasmid-borne EAST1 gene was associated with an extensive school outbreak of severe diarrhea (20). In a second Japanese outbreak, the implicated pathogen was an O166 E. coli that had no other identifiable E. coli virulence genes (31). In a small volunteer challenge study investigating the pathogenicity of EAEC, one of two EAST1-positive EAEC strains caused diarrhea (30). These reports suggest the potential importance of EAST1 and indicate that it may be found in association with different virulence factors.

The gene, astA that encodes EAST1 has been found in ETEC of both human and animal origin (37, 45, 46). The nucleotide sequence of a plasmid allele of astA in the prototype ETEC strain H10407 was found to be nearly identical to that of EAEC strain 17-2, although expression of enterotoxic activity was not reported (36, 45). That multiple genomic fragments of H10407 hybridized with an astA probe prompted speculation that the gene may be carried on a transposon (45). In this study, we isolated and characterized the EAST1 coding region from a virulence plasmid in human-derived ETEC strain 27D. We present evidence that this astA allele indeed expresses enterotoxic activity. Moreover, we show that it is located on an insertion sequence (IS) element lying entirely within a transposase-like gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The experiments reported herein were conducted according to the principles set forth in Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (6a).

Bacterial strains, plasmids and growth conditions.

The wild-type ETEC and derivative strains, host E. coli, and plasmid vectors used in this study are described in Table 1. E. coli MC4100LAC was made by conjugation of E. coli HfrH (1) with E. coli MC4100 (6), with selection for lactose fermentation, and was kindly provided by Colin Manoil. E. coli strains were routinely grown at 37°C on Luria-Bertani medium (33) except where noted otherwise. Growth medium was supplemented with ampicillin (50 to 100 μg ml−1) when appropriate for selection.

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains and plasmids used in this study

| Designation | Relevant property or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| H10407 | Human ETEC isolate; O78:H11, CFA/I, STIa, STIb, LT | 11 |

| H10407P | H10407 cured of 92-kb virulence plasmid | 11 |

| 27D | Human ETEC isolate; O126:NM, CFA/I, STIb | This work |

| 83/7 | Human ETEC isolate; O8:H10, LT | 37 |

| 12-1 | Human ETEC isolate; O6:H16; CFA/I, LT, STIb | This work |

| HB101 | Cloning host strain | 33 |

| DH5α | Cloning host strain | 33 |

| MC4100LAC | Chromosomal lac operon | C. Manoil |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC18 | Cloning vector, ampicillin resistant | 47 |

| pAM1 | 5.5-kb PstI fragment of 62-MDa plasmid from strain 27D cloned in pUC18 (astA) | This work |

| pAM2 | 2.4-kb SmaI-SphI fragment of pAM1 subcloned in pUC18 (astA) | This work |

| pAM13 | Derivative of pAM2 with point mutation in astA codon 16 (S16Stop) | This work |

DNA preparation and Southern blot hybridizations.

Plasmid DNA was isolated as described by Birnboim and Doly (5) or using plasmid extraction kits (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.). Total genomic DNA was isolated by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) lysis and subjected to proteinase K digestion, phenol-chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation. Restriction endonucleases and other DNA-modifying enzymes (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transformations were carried out by the procedure of Mandel and Higa (26), and electroporation was performed using a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) with electrocompetent cells prepared according to the manufacturer's protocol.

The astA DNA probe was prepared from plasmid pSS126 as previously described (37). STIa (STp)- and STIb (STh)-specific probe fragments, originally derived from plasmids pRIT10036 and pSLM004 (28), respectively, and religated into pUC13 for improved yields, were obtained from the Center for Vaccine Development, Baltimore, Md. Digestion of pCVD426 with PstI yielded a 157-bp STIa probe fragment, and digestion of pCVD427 with EcoRI yielded a 216-bp STIb fragment. The LT probe consisted of a 750-bp HindIII fragment of pEWD299 (8). A DNA probe for colonization factor antigen I (CFA/I) was amplified from H10407 plasmid DNA template by PCR with primers 313505C (5′-AGCTGATGGCAATGCTCTGCC-3′) and 259856T (5′-TCAGGATCCCAAAGTCATTACAAGAGAT-3′ (16) to produce a 387-bp fragment internal to the cfaB major structural subunit gene of CFA/I. Thirty-five cycles were performed with the following cycling conditions: 94°C for 1 min; 55°C for 1 min; and 72°C for 1 min. Probes were gel purified and labeled with [α-32P]dCTP by the random priming method.

DNA was digested with specified restriction endonucleases and separated by agarose gel electrophoresis (33). Using standard techniques, the DNA was denatured in the gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and cross-linked by UV irradiation (33). Hybridization and washing were performed in aqueous solution under high-stringency conditions (33). Blots were air dried and exposed to X-Omat AR film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.) at −70°C.

Construction of an astA mutant.

A point mutation in astA was made by altering codon 16 from TCG (serine) to TAG (amber), using a QuickChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and mutagenic primers. Plasmid pAM2 served as the template, and the mutant plasmid was designated pAM13. Presence of the mutation was confirmed by nucleotide sequence analysis of the astA gene.

Sequencing of astA coding region and analysis of deduced products.

The DNA sequence of the astA coding region was determined by the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method (34) on double-stranded pAM1 plasmid DNA template by using TaqI cycle sequencing kits (Applied Biosystems) in a thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer/Cetus). Both strands of DNA were sequenced using custom oligonucleotide primers that were synthesized on an ABI model 392 automated DNA-RNA synthesizer. Automated sequencing was performed with an ABI model 373 DNA sequencer.

The astA gene was amplified from strain 83/7 using the oligonucleotide primers sjs16 (5′-ATGCCATCAACACAGTATAT CCGAAGG-3′ and sjs17 (5′-TCAGGTCGCGAGTGACGGCTTTGT-3′) and whole-cell DNA as template with a GeneAmp PCR kit (Perkin-Elmer/Cetus). After initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 min, 25 cycles of amplification were done as follows: 94°C, 1 min; 55°C, 1 min; and 72°C, 1 min. The amplicon was precipitated and directly sequenced using the same primers.

DNA sequence data were analyzed with MacVector (version 4.1) software, and similarity searches were performed through the National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST server using BLASTP and BLASTN. Protein and DNA alignments were created using GeneWorks (version 2.4). The codon adaptation index (CAI) for E. coli, a measure of synonymous codon usage bias (39), was calculated for open reading frame 1 (ORF1) and astA, using DNA Strider (version 1.0).

IS designation.

The Plasmid Reference Center Prefix Registry (E. M. Lederberg, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, Calif.) made the IS1414 assignment.

Transposition experiments.

To detect transposition of IS1414, plasmid pAM2 was transformed into E. coli strain MC4100LAC and grown on tetrazolium agar with ampicillin. Lactose-nonfermenting colonies, identified by red coloration, were isolated and analyzed for insertions into lacZ-lacY by PCR analysis with two pairs of overlapping primers used in separate reactions. Primers SJ7 (5′-GCGTACTGTGAGCCAGATGCCCGGC-3′) and SJ8 (5′-GGTTTCCCGACTGGAAAGCGGGC-3′) amplify a 2.25-kb region that encodes the 5′ end of lacZ. Primers SJ5 (5′-GCGCCGCATCCGACATTGATTGC-3′) and SJ6 (5′-CCTGAACTACCGCAGCCGGAGAGC-3′) amplify a 2.35-kb region encoding the 3′ region of lacZ and all of lacY. For mutants with a lac insertion in the size range of IS1414, the lacZ-lacY amplicon containing the insertion was hybridized in Southern blots with an oligonucleotide probe for IS1414, SJ10 (5′-CTGGCAATCCAGTCTGCG-3).

In vitro transcription-translation.

In vitro transcription-translation was performed with the E. coli S30 extract system as instructed by the manufacturer (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Equivalent amounts of template DNA were used in each reaction. [35S]methionine (NEN Dupont, Boston, Mass.) was used for labeling in each reaction. Proteins were analyzed on a sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% polyacrylamide gel. After drying, the gel was exposed to X-Omat AR film overnight at −70°C.

Enterotoxin assays.

The Ussing chamber enterotoxin assay was performed using rabbit ileal tissue mounted in Lucite Ussing chambers (1.12-cm2 aperture) as previously described (37). Adult New Zealand White rabbits (2 to 3 kg) were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Potential difference was measured, and short-circuit current (Isc) and tissue conductance were calculated. A rise in Isc unaccompanied by a change in tissue conductance indicates an anionic secretory effect.

The suckling mouse biological assay for STI was performed as originally described (9). A gut-to-body (G/B) ratio above 0.083 was considered a positive response (14). HB101(pUC18) was used as a negative control and gave a mean G/B ratio of 0.063 (n = 6).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The IS1414 nucleotide sequence is deposited in the GenBank DNA sequence data library under accession number AF143819.

RESULTS

Copy number of astA in ETEC strains.

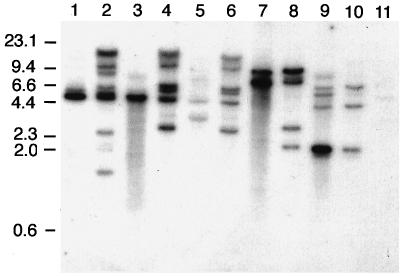

It was previously reported that prototype ETEC strain H10407 carries multiple genomic copies of astA, including one on its 92-kb virulence plasmid (29, 45). We examined three additional astA-positive ETEC strains to determine if the number of toxin gene copies varied from strain to strain. Similar to H10407, strain 27D had a single plasmid and multiple chromosomal restriction fragments that hybridized with the astA probe (Fig. 1). For the other two strains, several plasmid and chromosomal bands hybridized with the probe.

FIG. 1.

Southern analysis of plasmid DNA (odd-numbered lanes) and total cellular DNA (even-numbered lanes) of representative ETEC strains digested with PstI and hybridized with a 32P-labeled astA probe. Lanes: 1 and 2, strain 27D; 3 and 4, H10407; 5 and 6, H10407P; 7 and 8, strain 83/7; 9 and 10, strain 12-1; 11, negative control HB101 (total cellular DNA). The relative positions of DNA standards are shown in kilobases on the left.

Isolation of the astA plasmid allele from ETEC strain 27D.

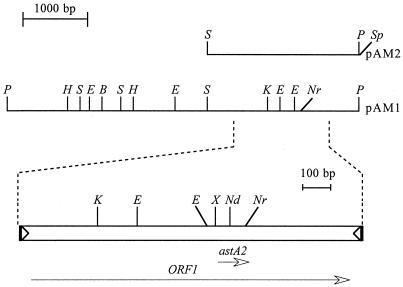

ETEC strain 27D was selected for further characterization. Similar to H10407, astA as well as the genes for STIb (estA) and CFA/I (cfaB) were localized to a 92-MDa plasmid (data not shown). The astA probe hybridized with a 5.5-kb PstI fragment of the large plasmid from both strains (Fig. 1). We purified the astA-hybridizing PstI plasmid fragment from strain 27D and ligated it into pUC18. The recombinant plasmid was designated pAM1 (Fig. 2). An STIb DNA probe did not hybridize to pAM1, indicating that we had cloned the astA allele separately from STIb. A 2.4-kb fragment of the pAM1 insert was obtained by digestion with SmaI and SphI (from the pUC18 polylinker region) which also hybridized with the astA probe (data not shown). This fragment was ligated back into pUC18 to yield plasmid pAM2 (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Restriction map of the 5.5-kb PstI insert of pAM1, below which is shown an expanded map of a 1.3-kb segment comprising IS1414. The two open triangles in the expanded area represent 30-bp imperfect inverted repeats, and the flanking direct repeats are indicated by filled vertical bars. Locations of the astA gene and a putative transposase gene (ORF1) are indicated by open-headed arrows that show their extent and direction of transcription. The astA ORF is in the +1 reading frame relative to ORF1. Extent of the pAM2 insert is shown above the restriction map of pAM1. Restriction sites are indicated by P (PstI), Nr (NruI), E (EcoRV), K (KpnI), S (SmaI), Sp (SphI), H (HindIII), B (BamHI), Nd (NdeI), and X (XmnI).

Characterization of the 1.3-kb region containing astA.

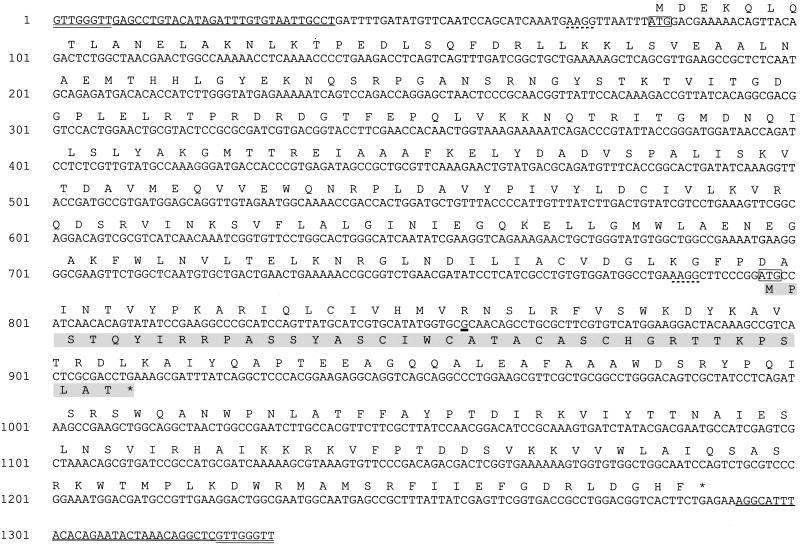

The nucleotide sequence of the 1.3-kb region including the astA-hybridizing allele was determined (Fig. 3). Analysis revealed that this region contains a 117-nucleotide (nt)-long ORF predicted to encode a polypeptide of 38 amino acids. Comparison of this sequence with that of the EAST1 structural gene of EAEC strain 17-2 (36) revealed a single nonsynonymous nucleotide sequence difference in codon 21 that resulted in a conserved amino acid substitution (threonine to alanine) (Fig. 3). The astA gene of ETEC strain 83/7 was amplified using primers that anneal to the 5′ and 3′ ends of the EAEC 17-2 astA coding sequence. Direct DNA sequence analysis of this PCR product showed that it was identical to astA of ETEC 27D (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Nucleotide sequence of IS1414 and deduced amino acid sequence of astA and ORF1 of pAM1. The deduced amino acid sequence of ORF1 (starting at bp 81) is shown above and that of EAST1 (starting at bp 796) is shown below the DNA sequence in one-letter code, with the latter sequence highlighted in gray. The ATG start codon of each gene is boxed, and the purported ribosome binding site for each is underscored by a dotted line. The single nucleotide difference between this astA allele and that of EAEC 17-2 (A→G) is marked by a thick underline. The 30-base imperfect IR sequences are underlined, and the flanking 8-base direct repeats are double underlined.

On further analysis of the 1.3-kb DNA sequence from pAM1, a second, larger 1,209-bp ORF (ORF1) was identified in the same coding region but in the −1 reading frame with reference to astA. The initiation codon is located 715 bp upstream and the termination codon is 377 bp downstream of astA start codon (Fig. 3). ORF1 encodes a predicted protein of 402 amino acids with a calculated Mr of 45,800 and a pI of 9.18. It is bounded by imperfect 30-bp inverted repeat (IR) sequences, and this entire structure is flanked by 8-bp direct repeats (Fig. 3).

A comparison of the predicted protein sequence of ORF1 to the National Center for Biotechnology Information sequence database revealed similarities to transposases of several other insertion elements, including IS285 of Yersinia pestis (64% identity; 72% similarity), IS1356 of Burkholderia cepacia (47% identity; 68% similarity), and ISRm3 of Rhizobium meliloti (46% identity; 63% similarity) (12, 42, 44). The N-terminal portion of the ORF1 protein was also highly similar to the predicted product of ORF4 (95% identity; 97% similar over 150 amino acids), part of an apparent IS located downstream of bfpTVW, a virulence regulatory locus of enteropathogenic E. coli (41). ORF1 also showed high similarity to the IS285 (77% identical over 811 nt), ISRm3 (60% identical over 1,208 nt), and IS1356 (55% identical over 1,215 nt) transposase genes at the nucleotide level. The left-hand IR flanking ORF1 exhibited high identity to the corresponding left-hand IRs of IS285 (79% identity), IS1356 (66% identity), and ISRm3 (50% identity). It should be noted, however, that none of the related insertion elements from these other genera contain an astA-like ORF within the transposase gene. Based on the transposase-like sequence of ORF1 and the other structural features of this 1,330-bp region, which are wholly characteristic of a regular IS, this element was designated IS1414.

EAST1 phenotypic analysis.

Culture filtrates from ETEC strains 27D and HB101(pAM1) were assayed for enterotoxic activity by both the suckling mouse bioassay and the in vitro Ussing chamber assay. ETEC 27D culture filtrates induced fluid accumulation in suckling mice (mean G/B ratio of 0.133 ± 0.009 [standard error of the mean], n = 4 animals) and also increased Isc in the Ussing chamber assay (Table 2). Culture filtrates from HB101(pAM1) exhibited activity in the Ussing chamber assay (data not shown) but failed to elicit a response in the suckling mouse assay (mean G/B ratio of 0.059 ± 0.002, n = 4 animals). Culture filtrates from HB101(pAM2), a subclone of pAM1, also exhibited enterotoxin activity in the Ussing chamber assay (Table 2). Hence, the presence of astA correlated with detection of enterotoxic activity in Ussing chamber but not in the suckling mouse assay, consistent with earlier findings for the astA allele of EAEC strain 17-2 (35).

TABLE 2.

Enterotoxic activity of culture ultrafiltratesa from ETEC strain 27D and recombinant derivatives with the astA+ and astA mutated alleles

| Strain | Toxin genotype | Mean Ussing chamber activity (ΔIsc; μA/cm2) ± SEMb |

|---|---|---|

| ETEC 27D | estA astA | 113.6 ± 31.7 |

| HB101(pUC18) | 7.3 ± 15.9c | |

| HB101(pAM2) | astA | 87.0 ± 9.6 |

| HB101(pAM13) | astA (S16Stop) | 3.9 ± 19.3cd |

Culture ultrafiltrates of <10-kDa were added to the mucosal compartments of Ussing chambers.

n = 7 observations for each strain from a total of three animals.

P < 0.01 compared to ETEC 27D, paired t test.

P < 0.01 compared to HB101(pAM2), paired t test.

A point mutation was made in astA to look for ablation of toxic activity. Plasmid pAM13 was constructed by introducing a stop codon in place of serine 16 (TCG to TAG), this alteration being silent with respect to ORF1. Culture filtrates from HB101(pAM13) showed no enterotoxic activity as detected in the Ussing chamber assay (Table 2). This finding indicated that the enterotoxic activity is specifically encoded by astA and not by ORF1.

In vitro expression of the ORF1 gene product.

By in vitro transcription-translation, pAM1 and pAM2, both containing the entirety of ORF1, expressed a distinct protein of Mr ∼46,000, which corresponds closely in size to the predicted product of ORF1 (Mr 45,800) (data not shown).

Attempted demonstration of IS1414 transposition.

E. coli strain MC4100LAC was transformed with pAM2, and transformants were selected on tetrazolium agar with ampicillin. About 1.5 × 106 transformants were screened, and 7 independent lactose nonfermenting transformants were obtained. These were isolated and analyzed for insertions in lacZ-lacY by PCR. Two of the transformants had an insertion of about 1.2 kb in the 3′ lacZ-lacY region. On Southern blot analysis, the amplified lacZ-lacY region containing each of these insertions failed to hybridize with an IS1414 DNA probe, while the homologous sequence in the pAM2 positive control did hybridize with the probe. Accordingly, we concluded that neither insertion into the lac operon was IS1414. We were thus unable to demonstrate transposition of IS1414.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have extended the observations of Yamamoto and Echeverria (45) showing that human ETEC often carry multiple genomic copies of astA. We determined the nucleotide sequence of astA from two ETEC strains of human origin, 27D and 83/7, and showed that the plasmid allele from one strain, ETEC 27D, expressed toxic activity. The EAST1 coding sequences of both strains were identical to each other and to that reported previously for prototype ETEC H10407 (45) and were nearly identical to that originally reported for EAEC 17-2 (36).

We isolated and further characterized the astA allele from the CFA/I-, STIb-bearing plasmid of one strain, ETEC 27D. Recombinant plasmids containing astA on a 5.5-kb insertion fragment and a 2.4-kb derivative fragment both expressed enterotoxic activity, as evidenced by electrogenic stimulation of rabbit ileal tissue mounted in Ussing chambers. Mutation of the toxin allele, whereby serine 16 was replaced with an amber codon, resulted in a loss of enterotoxin expression. This mutation was silent with respect to ORF1, an overlapping gene on the same strand but in an alternate reading frame to astA. This provides incontrovertible evidence that enterotoxicity is attributable to EAST1 and not to the product of ORF1.

These findings add to the evidence that some ETEC strains have the potential to express EAST1, a factor distinct from other members of its more firmly established arsenal of enterotoxins. With regard to secretogenic capacity, ETEC strains apparently approach the host-pathogen interface with a considerable degree of redundancy. Whether the ability to produce multiple enterotoxins confers pathogenic advantage to ETEC is not entirely clear. Some epidemiological data suggest that strains producing both LT and STI are more likely to cause disease or more severe disease than strains producing only one of these toxins (15, 25). In light of the findings present herein and elsewhere (37, 45, 46), assessment of the incremental effects of ETEC enterotoxins on virulence deserves renewed attention. The independent and additive role of EAST1 in the virulence of ETEC or other diarrheogenic E. coli, if any, may best be addressed by carefully designed epidemiological studies supplemented by studies in the human challenge model with well-defined wild-type strains and EAST1 isogenic derivatives.

The ETEC 27D plasmid allele of astA is part of IS1414, an element with features highly characteristic of an insertion sequence. IS1414 is 1,330 bp long, having one ORF (ORF1) that spans its core region with 30-bp imperfect IR sequences at its ends. It is flanked by 8-bp direct repeat sequences that typically arise from duplication of target DNA upon IS insertion. ORF1 encodes a protein that is highly similar to the predicted transposase proteins of IS285 of Y. pestis, IS1356 of B. cepacia, and ISRm3 of R. meliloti. A protein of the same size as that predicted for the product of ORF1 was expressed in vitro from IS1414 DNA template. We were, however, unable to demonstrate transposition of IS1414. Our lack of success may be explained by a relatively low frequency of transposition into the selected target DNA, the requirement for additional structural elements not present on pAM2, or the presence of mutations within IS1414 which render it nonfunctional.

In the core region of IS1414, the entirety of the astA gene is embedded in the coding region of ORF1, but in the +1 frame relative to the larger gene. This configuration suggests a remarkably economic arrangement for the storage and dissemination of genetic information of importance to bacterial virulence or survival. It represents the rarest type of overlapping gene and one that, to our knowledge, has not been found in a bacterial system. Pairs of completely overlapping genes have been described for several viruses (2, 10, 48). One pertinent example of this arrangement is found in the highly compact hepatitis B virus genome, where the gene encoding hepatitis B surface antigen is contained completely within the DNA polymerase gene (27). A different overlapping gene arrangement has recently been reported for EAEC. Two tandem genes identical to those encoding Shigella enterotoxin 1 were found within and on the complementary noncoding strand of a gene encoding a protein involved in intestinal colonization (Pic) (18). Other arrangements, including partially overlapping genes and intron-containing genes, have been more frequently observed (3, 32).

It is interesting to speculate how IS1414 came to acquire these two overlapping genes. The existence of related IS elements that do not contain the astA sequence implies that acquisition of the toxin gene occurred some time after divergence of the ancestrally related transposases. It is possible that EAST1 then arose by overprinting, de novo translation of the ORF1 transposase sequence in a different frame (22). Origination of new coding sequences by overprinting predicts unusual codon usage for the new gene. Consistent with this prediction, astA has an atypically low CAI (0.132), indicative of a deviation away from preferred E. coli codon usage, while ORF1 shows a greater degree of synonymous codon bias toward E. coli (CAI, 0.362). Bestowal of some advantage to these progeny would favor maintenance and dissemination of the toxin gene, in this case facilitated by IS1414 transposition.

The presence of two overlapping genes poses constraints on evolution, such that a tendency of the individual genes to separate after duplication may be expected (22). Bearing this in mind, we compared the nucleotide sequence of IS1414 ORF1 to the corresponding sequence in the region of astA on the virulence plasmid of EAEC strain 17-2 (36) (S. J. Savarino, unpublished data). In the region of ORF1 5′ to nucleotide 667, there is no similarity between the two sequences. In the 3′ end of ORF1 (nt 668 to 1209), the span in which the EAST1 coding sequence is also found, the two sequences share 99.2% nucleotide identity. It seems likely that a recombination event in EAEC strain 17-2 at this transition point led to disruption of ORF1 and loss of integrity of IS1414, without affecting the EAST1 coding sequence.

If astA expression confers a particular advantage on survival of E. coli expressing additional virulence factors, such as may be the case with EAEC, degradation of IS1414 function by deletion within the transposase gene might ensure the continued association of astA with other factors encoded by the EAEC virulence plasmid (7). If, on the other hand, astA expression is neutral in a particular background, such as may be the case in ETEC where EAST1 activity may be redundant to other enterotoxins, maintenance of IS1414 function might ensure a reservoir for continued dissemination of the gene into new host strains. Additional studies of IS1414 stability, function, and association with astA in diverse E. coli isolates are necessary to further our understanding of this novel mechanism of evolution of bacterial virulence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Naval Medical Research and Development Command Work Unit 611020B998.AKS13.I.I.1395.

We acknowledge John Watson for experimental contributions early in the course of this work and Peter Echeverria for performance of suckling mouse assays. We thank Patricia Guerry for critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bachman B J. Derivations and genotypes of some mutant derivatives of Escherichia coli K-12. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 2460–2488. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrell B G, Air G M, Hutchinson C A. Overlapping genes in bacteriophage φX174. Nature. 1976;264:34–40. doi: 10.1038/264034a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bechhofer D H, Hue K K, Shub D A. An intron in the thymidylate synthase gene of Bacillus bacteriophage β22: evidence for independent evolution of a gene, its group I intron, and the intron open reading frame. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11669–11673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bern C, Martines J, de Zoysa I, Glass R I. The magnitude of the global problem of diarrhoeal diseases: a ten-year update. Bull WHO. 1992;70:705–714. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birnboim H C, Doly J. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:1513–1523. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casadaban M J. Transposition and fusion of the lac genes to selected promoters in Escherichia coli using bacteriophage lambda and Mu. J Mol Biol. 1976;104:541–555. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6a.Committee on Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Washington, D.C.: Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Czeczulin J R, Whittam T S, Henderson I R, Navarro-Garcia F, Nataro J R. Phylogenetic analysis of enteroaggregative and diffusely adherent Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2692–2699. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2692-2699.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dallas W S, Gill D M, Falkow S. Cistrons encoding Escherichia coli heat-labile toxin. J Bacteriol. 1979;139:850–858. doi: 10.1128/jb.139.3.850-858.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dean A G, Ching Y C, Williams R G, Harden L B. Test for Escherichia coli enterotoxin using infant mice: application in a study of diarrhea in children in Honolulu. J Infect Dis. 1972;125:407–411. doi: 10.1093/infdis/125.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ernst H, Shatkin A J. Reovirus hemagglutinin mRNA codes for two polypeptides in overlapping reading frames. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:48–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans D J, Jr, Evans D G. Three characteristics associated with enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated from man. Infect Immun. 1973;8:322–328. doi: 10.1128/iai.8.3.322-328.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filippov A A, Oleinikov P N, Motin V L, et al. Sequencing of two Yersinia pestis IS elements, IS285 and IS100. Contrib Microbiol Immunol. 1995;13:306–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaastra W, de Graaf F K. Host-specific fimbrial adhesins of noninvasive enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli strains. Microbiol Rev. 1982;46:129–261. doi: 10.1128/mr.46.2.129-161.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giannella R A. Suckling mouse model for detection of heat-stable Escherichia coli enterotoxin: characteristics of the model. Infect Immun. 1976;14:95–99. doi: 10.1128/iai.14.1.95-99.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gothefors L, Ahren C, Stoll B, et al. Presence of colonization factor antigens on fresh isolates of fecal Escherichia coli: a prospective study. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:1128–1133. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.6.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamers A M, Pel H J, Willshaw G A, et al. The nucleotide sequence of the first two genes of the CFA/I fimbrial operon of human enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Microb Pathog. 1989;6:297–309. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(89)90103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hedberg C W, Savarino S J, Besser J M, et al. An outbreak of foodborne illness caused by Escherichia coli O39:NM, an agent not fitting into the existing scheme for classifying diarrheogenic E. coli. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1625–1628. doi: 10.1086/517342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henderson I R, Czeczulin J, Eslava C, Noriega F, Nataro J P. Characterization of Pic, a secreted protease of Shigella flexneri and enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5587–5596. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5587-5596.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holland R E. Some infectious causes of diarrhea in young farm animals. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:345–375. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.4.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Itoh Y, Nagano I, Kunishima M, Ezaki T. Laboratory investigation of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli O untypeable:H10 associated with a massive outbreak of gastrointestinal illness. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2546–2550. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2546-2550.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kapitany R A, Scoot A, Forsyth G W, McKenzie A L, Worthington R W. Evidence for two heat-stable enterotoxins produced by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1979;24:965–966. doi: 10.1128/iai.24.3.965-966.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keese P K, Gibbs A. Origins of genes: “big bang” or continuous creation? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9489–9493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee C-H, Hu S-T, Swiatek P J, Moseley S L, Allen S D, So M. Isolation of a novel transposon which carries the Escherichia coli enterotoxin STII gene. J Bacteriol. 1985;162:615–620. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.2.615-620.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levine M M. Escherichia coli that cause diarrhoea: enterotoxigenic, enteropathogenic, enteroinvasive, enterohemorrhagic, and enteroadherent. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:377–389. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez-Vidal Y, Calva J J, Trujillo A, et al. Enterotoxins and adhesins of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli: are they risk factors for acute diarrhea in the community? J Infect Dis. 1990;162:442–447. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.2.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mandel M, Higa A. Calcium dependent bacteriophage DNA infection. J Mol Biol. 1970;53:159–162. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mizokami M, Orito E, Ohba K, et al. Constrained evolution with respect to gene overlap of hepatitis B virus. J Mol Evol. 1997;44:S83–S89. doi: 10.1007/pl00000061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moseley S L, Echeverria P, Seriwatana J, et al. Identification of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli by colony hybridization using three enterotoxin gene probes. J Infect Dis. 1982;145:863–869. doi: 10.1093/infdis/145.6.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moseley S L, Samadpour-Motalebi M, Falkow S. Plasmid association and nucleotide sequence relationships of two genes encoding heat-stable enterotoxin production in Escherichia coli H-10407. J Bacteriol. 1983;156:441–443. doi: 10.1128/jb.156.1.441-443.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nataro J P, Yikang D, Cookson S, et al. Heterogeneity of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli virulence demonstrated in volunteers. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:465–468. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.2.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishikawa Y, Ogasawara J, Helander A, Haruki K. An outbreak of gastroenteritis in Japan due to Escherichia coli O166. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:300. doi: 10.3201/eid0502.990220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pelet T, Curran J, Kolakofsky D. The P gene of bovine parainfluenza virus 3 expresses all three reading frames from a single mRNA editing site. EMBO J. 1991;10:443–448. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07966.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savarino S J, Fasano A, Robertson D C, Levine M M. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli elaborate a heat-stable enterotoxin demonstrable in an in vitro rabbit intestinal model. J Clin Investig. 1991;87:1450–1455. doi: 10.1172/JCI115151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Savarino S J, Fasano A, Watson J, et al. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin 1 represents another subfamily of E. coli heat-stable toxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3093–3097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.3093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Savarino S J, McVeigh A M, Watson J, et al. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin is not restricted to enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1019–1022. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.4.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schulz S, Lopez M J, Kuhn M, Garbers D L. Disruption of the guanylyl cyclase-C gene leads to a paradoxical phenotype of viable but heat-stable enterotoxin-resistant mice. J Clin Investig. 1997;100:1590–1595. doi: 10.1172/JCI119683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharp P M, Li W H. The codon adaptation index—a measure of directional synonymous codon usage bias, and its potential applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:1281–1294. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.3.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.So M, Heffron F, McCarthy B J. The E. coli gene encoding heat stable toxin is a bacterial transposon flanked by inverted repeats of IS1. Nature. 1979;277:453–456. doi: 10.1038/277453a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tobe T, Schoolnik G K, Sohel I, et al. Cloning and characterization of bfpTVW, genes required for the transcriptional activation of bfpA in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:963–975. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.531415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tyler S D, Rozee D R, Johnson W M. Identification of IS1356, a new insertion sequence, and its association with IS402 in epidemic strains of Burkholderia cepacia infecting cystic fibrosis patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1610–1616. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1610-1616.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vila J, Gene A, Vargas M, et al. A case-control study of diarrhoea in children caused by Escherichia coli producing heat-stable enterotoxin (EAST-1) J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:889–891. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-10-889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wheatcroft R, Laberge S. Identification and nucleotide sequence of Rhizobium meliloti insertion sequence ISRm3: similarity between the putative transposase encoded by ISRm3 and those encoded by Staphylococcus aureus IS256 and Thiobacillus ferrooxidans IST2. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2530–2537. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.8.2530-2538.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamamoto T, Echeverria P. Detection of the enteroaggregative Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin 1 gene sequences in enterotoxigenic E. coli strains pathogenic for humans. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1441–1445. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1441-1445.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamamoto T, Nakazawa M. Detection and sequences of the enteroaggregative Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin 1 gene in enterotoxigenic E. coli strains isolated from piglets and calves with diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:223–227. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.223-227.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zajanckauskaite A, Malys N, Nivinskas R. A rare type of overlapping genes in bacteriophage T4: gene 30.3′ is completely embedded within gene 30.3 by on position. Gene. 1997;194:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00127-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]