Abstract

Smooth lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of Brucella abortus has been reported to be an important virulence factor, although its precise role in pathogenesis is not yet clear. While the protective properties of LPS against complement are well accepted, there is still some controversy about the capacity of rough mutants to replicate intracellularly. The B. abortus phosphoglucomutase gene (pgm) was cloned, sequenced, and disrupted. The gene has a high index of identity to Agrobacterium tumefaciens pgm but is not part of the glycogen operon. A B. abortus null mutant lacks LPS O antigen but has an LPS core with an electrophoretic profile undistinguishable from that of the wild-type core, suggesting that glucose, galactose, or a derivative of these sugars may be part of the linkage between the core and the O antigen. This mutant is unable to survive in mice but replicates in HeLa cells, indicating that the complete LPS is not essential either for invasion or for intracellular multiplication. This behavior suggests that the LPS may play a role in extracellular survival in the animal, probably protecting the cell against complement-mediated lysis, but is not involved in intracellular survival.

Brucella spp. are gram-negative, facultative intracellular bacteria that cause a chronic zoonotic disease worldwide. Six species of Brucella with different host specificies and pathogeneses have been described (11, 35). Brucella abortus is the etiological agent of bovine brucellosis, but it can also affect humans, causing undulant fever; this disease is caused also by Brucella melitensis, Brucella suis, and Brucella canis. Brucellae proliferate within host macrophages, and virulence is associated with the ability to multiply intracellularly. Once inside the cells, Brucella avoids the fusion of the phagosome with the lysosome by altering the intracellular traffic of the early phagosome vesicle. It has recently been demonstrated that brucellae replicate in a vesicle compartment containing reticuloendoplasmic markers reached after preventing the fusion between phagosomes and lysosomes (19–21).

As in many other gram-negative bacteria, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is an important component of the outer membrane. LPS has three domains: lipid A, the core oligosaccharide, and the O antigen or O side chain. The complete structure of Brucella LPS has not yet been elucidated, but it was reported that lipid A is composed of glucosamine, n-tetradecanoic acid, n-hexadecanoic acid, 3-hydroxytetradecanoic acid, and 3-hydroxyhexadecanoic acid (5). The O side chain is a linear homopolymer of α-1,2-linked 4,6-dideoxy-4-formamido-α-d-mannopyranosyl (perosamine) subunits, usually with a degree of polymerization averaging between 96 to 100 subunits (5). The complete structure of B. abortus core LPS has not yet been determined. Previous reports have shown that is formed by 2-keto-3-deoxy-d-manno-2-octulosonic acid, glucosamine, and glucose, although the exact amounts of these sugars have not been determined (17).

The absence of the O side chain from LPS determines the rough phenotype. Generally these mutants are less virulent than the wild type, with the exception of those of Brucella ovis and B. canis, which are rough but virulent (24). It is accepted that rough mutants are more sensitive to lysis mediated by complement, and probably this is the main reason why most rough variants have an avirulent phenotype in animal models. To date the question about the capacity of rough mutants to replicate intracellularly is not solved. Some authors have reported that smooth LPS is essential for intracellular survival (22, 23), for example, the vaccine strain RB51 exhibits loss of virulence and cannot replicate within macrophages (27). On the other hand, there are some reports in which genetically characterized rough mutants did not loose the capacity to replicate intracellularly despite the total absence of the O antigen (1). In a recent search for rough mutants of B. melitensis, the gene coding for the perosamine synthetase was isolated. A mutant with a mutation in this gene has a rough phenotype and is unable to survive in mice but can replicate in bovine macrophages (9).

One possible explanation for these discrepancies may be that many of the experiments carried out to understand the role of the O antigen were performed using mutants fortuitously isolated by screening for the rough phenotype. As a result of this procedure, the isolated mutants lack genetic definition, and in consequence a relation between the rough phenotype and defective intracellular replication has not been directly confirmed. It is interesting that the only two rough mutants with a genetic characterization are able to replicate in macrophages (1, 9). Increasing knowledge on the genetic loci involved in LPS biosynthesis will allow studies of the role of LPS in intracellular survival. With this information available, the idea that rough phenotypes are always associated with deficient intracellular replication may no longer be the rule. These studies must be done by altering one gene at a time and analyzing the generated phenotype.

In Agrobacterium tumefaciens, a member of the alpha subgroup of the proteobacteria closely related to Brucella spp., the gene that codes for phosphoglucomutase was extensively studied at the biochemical and molecular levels by our group (29, 31–33). We found that this gene is absolutely necessary for the biosynthesis of ADP-glucose, UDP-glucose, and UDP-galactose, the donors of glucose or galactose for the biosynthesis of molecules containing these sugars. An A. tumefaciens pgm mutant is avirulent and cannot synthesize exopolysaccharide, β(1,2) cyclic glucan, glycogen, and LPS (4, 32). In view of these results and the close relationship between agrobacteria and brucellae, we studied the effect of pgm mutation on the virulence and intracellular multiplication of B. abortus.

We describe in this report the cloning, nucleotide sequence, and insertional mutagenesis of a gene (pgm) encoding the phosphoglucomutase of B. abortus. The characterization of the LPS, the virulence of the mutant in the mouse model, and the intracellular multiplication of the mutant were analyzed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli was grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani broth (25) or Terrific broth (28). Brucella strains were grown at 37°C in tryptic soy broth (TSB). If necessary, the medium was supplemented with appropriate antibiotics as follows: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml for E. coli and 50 μg/ml for B. abortus; gentamicin, 20 μg/ml for E. coli and 2.5 μg/ml for B. abortus; and tetracycline, 10 μg/ml for E. coli.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain and plasmid | Characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli K-12 DH5α-F′IQ | F′ φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) phoA supE44 λ− thi-1 gyrA96 relA1/F′ proAB+ lacIqZΔM15 zzf::Tn5(Kmr) | 37 |

| A. tumefaciens A5129 | pgm::Tn5 | 33 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBR262 | 20-kb fragment of genomic DNA of B. abortus 2308 in pVK102 that complements A5129 | This study |

| pBE39 | 4.3-kb EcoRI fraghment of pBR262 containing pgm of B. abortus in pBluescript KSII(+) | This study |

| pUB22 | 4.3-kb EcoRI fragment of pBR262 containing pgm of B. abortus in pUC19 | This study |

| pUB22G | pUB22, pgm::Gmr | This study |

| pBBE30 | 4.3-kb EcoRI fragment of pBR262 containing pgm of B. abortus in pBBR1MCS-4 | This study |

| pSPG1 | Nonpolar cassette accI (Gmr) in pSportI | This study |

| pBBR1MCS-4 | Broad-host-range cloning vector (Ampr) | 13 |

Cloning, DNA sequencing, and gene disruption.

To isolate the pgm gene of B. abortus, a clone, named H7 (30) (accession number AQ752933), with high homology to the pgm gene of A. tumefaciens, was used as a probe to screen a genomic library of B. abortus strain 2308 (12). The screening was carried out as described previously (25) with filters washed at high stringency. Three cosmids, pBR261, pBR262, and pBR263, with different restriction enzyme patterns were isolated. Southern blot analysis was performed with the three cosmids digested with EcoRI as described previously (25), using the H7 clone as a probe. A fragment of 4.3 kb was identified in cosmid pBR262; it was eluted from the gel and ligated into pBluescript KS II(+) (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) digested with EcoRI. This plasmid was named pBE39. Plasmid pBE39 was further digested with HindIII, and three fragments of approximately 3, 1, and 0.8 kb were generated. These fragments were subcloned in pBluescript KS II(+) digested with HindIII, and they were sequenced by the dideoxy terminator method using the T7 Sequenase version 2.0 DNA sequencing kit (Amersham Life Science).

In order to mutagenize the pgm gene of B. abortus 2308, plasmid pBE39 was digested with EcoRI, and the DNA fragment of 4.3 kb was eluted from the gel and ligated into pUC19 digested with EcoRI. The resulting plasmid was named pUB22. Since pUC19 lacks an EcoRV restriction enzyme site, a gentamicin-resistant nonpolar cassette was introduced in a unique EcoRV site of the pgm gene by digesting the cassette with SmaI and ligating it into pUB22 digested with EcoRV. The resulting plasmid was named pUB22G, and it was introduced in B. abortus by electroporation. Double recombination events (Gmr Amps) were selected and confirmed by PCR with a set of primers that amplified a 442-bp fragment from the wild-type gene and a 1,193-bp fragment from the gentamicin-interrupted gene.

For complementation experiments, the 4.3-kb fragment was ligated in pBBR1MCS-4 (13) digested with EcoRI; the resulting plasmid was named pBBE30.

Construction of a nonpolar gentamicin resistance cassette.

The gene accI, coding for gentamicin resistance, was amplified with oligonucleotides 5′-TAGGATCCTTGACATAAGCCTGTTCG-3′ and 5′-TAGGATCCTTAGGTGGCGGTACTTGG-3′ from the promoter to the stop codon. This fragment, lacking the termination stem-loop of the gene, was cloned in pBluescript KS II(+) digested with BamHI. The resulting plasmid was digested with HindIII and NotI and ligated into pSport1 (Gibco, Paisley, Scotland) digested with the same restriction enzymes. The resulting plasmid, named pSPG1, has, at both flanking sides of the accI gene, the following restriction sites: BamHI, SmaI, PstI, and EcoRI. It also has other nonsymmetrical restriction sites.

LPS purification and analysis.

LPS was isolated by the hot-phenol-water extraction procedure (36) from 100 ml of cells from overnight cultures. The concentration of LPS was measured by the 2-keto-3-deoxy-d-manno-2-octulosonic acid assay (18) and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in 14% gels containing 4 M urea. LPS was detected by silver staining as described elsewhere (15). Tricine gel analysis was performed as described previously (26).

Intracellular replication in nonprofessionalphagocytes.

Intracellular replication was evaluated in HeLa cells as described elsewhere (19). Briefly, Brucella strains and mutants were grown in liquid medium for 24 h and resuspended in minimal essential medium (Gibco) complemented with 5% fetal calf serum and 2 mM glutamine without antibiotics (complete culture medium) at 107 CFU per ml. This suspension was added to HeLa cells at a multiplicity of infection of 500:1 and centrifuged at 180 × g for 10 min. After 1 h of incubation at 37°C, fresh complete culture medium with 100 μg of gentamicin per ml and 50 μg of streptomycin per ml was added to the monolayers. At 4, 24, and 48 h, the monolayers were washed five times with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) and lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100. The Triton lysates were then diluted serially and plated on TSB agar with the appropriate antibiotics to determine the number of CFU recovered per milliliter.

Virulence in mice.

Virulence was determined by quantitating the survival of the strains in the spleen after 2 weeks. Nine-week-old female BALB/c mice were injected intraperitoneally with approximately 105 CFU of brucellae in 0.1 ml of 150 mM NaCl. Groups of five mice were injected with either B. abortus 2308, B. abortus B2211, or B. abortus B2211 complemented with plasmid pBBE30.

At 15 days postinfection animals were sacrificed by decapitation, and spleens were removed, weighed, and homogenized in 150 mM NaCl. Tissue homogenates were serially diluted with phosphate-buffered saline and plated on TSB agar with the appropriate antibiotics to determine the number of CFU per spleen.

PmB assays.

The bactericidal effect of polymyxin B (PmB) was tested as described elsewhere (1). Overnight cultures of both strains were centrifuged and resuspended with HEPES (1 mM, pH 8). Approximately 103 CFU was incubated at 37°C for 1 h over a range of PmB concentrations. Following the 1-h incubation period, 10-μl portions of the cell suspensions were spotted quadruplicated on TSB agar plates. This assay was performed in duplicate. The percentage of surviving bacteria was calculated according to the CFU recovered.

Inhibition of growth was calculated by plating a known number of CFU on TSB agar plates with increasing concentrations of PmB.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of the pgm gene of B. abortus has been assigned GenBank accession number AF232056.

RESULTS

Identification, cloning, and nucleotide sequence of a gene encoding the phosphoglucomutase of B. abortus.

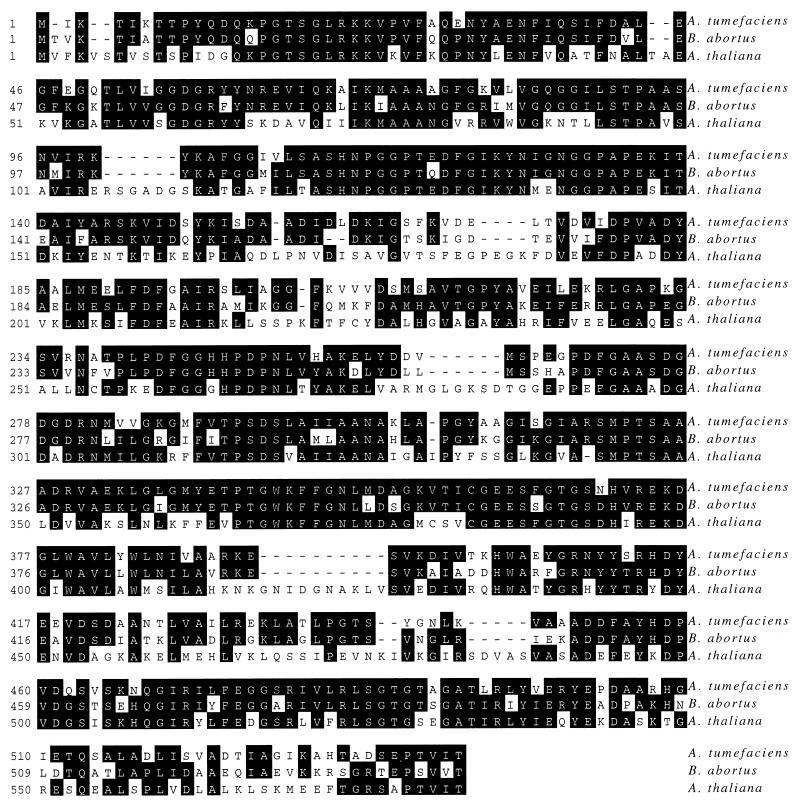

As a result of a B. abortus genome project (30), a clone named H7 (accession number AQ752933) with high homology to the phosphoglucomutase of A. tumefaciens was identified (33). Using this clone as a probe, a library of cosmids of B. abortus 2308 was screened and three cosmids with different restriction enzyme patterns were isolated. In order to verify the presence of pgm in the cosmid inserts, they were introduced by electroporation into the dark-phenotype A. tumefaciens pgm mutant A5129 (33) (Table 1). The resulting transformants were plated on Luria-Bertani agar with 0.02% Calcofluor (Sigma Chemical Co.) and observed under UV light. The three cosmids complemented the dark phenotype, thus indicating that the pgm gene was present in the cosmids and correctly expressed in the Agrobacterium background. The cosmids were digested with the EcoRI restriction enzyme, and a Southern blot analysis was performed using clone H7 as a probe. A DNA fragment of approximately 4,300 bp was identified in one of the cosmids, and this fragment was cloned in pBluescript KS II(+). Both strands of the DNA insert of the resulting plasmid, named pBE39, were sequenced. Analysis of the sequence revealed that the 4.3-kb DNA fragment contained an open reading frame of 1,635 bp coding for a protein of 544 amino acids which is 74.7% identical to the phosphoglucomutase of A. tumefaciens (33) and 50% identical to the protein of Arabidopsis thaliana (accession number AAC00601) (Fig. 1). Sequence analysis of the regions upstream and downstream of pgm revealed no significant homology to any gene in the database, which was surprising since in A. tumefaciens and Rhizobium loti, pgm is part of the glycogen operon (29). This result indicates that in B. abortus, pgm is not part of the glycogen operon.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the B. abortus phosphoglucomutase protein with the A. tumefaciens and A. thaliana proteins. Conserved amino acids are indicated by black boxes. The alignment was performed with the MegAlign program.

A pgm mutant strain lacks the O antigen but has a complete core.

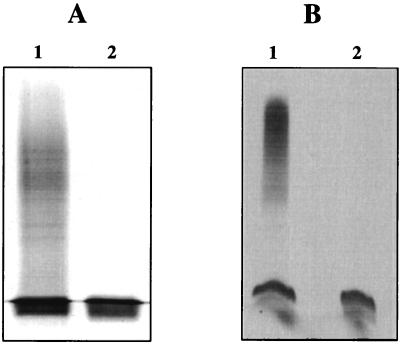

Insertional mutagenesis of pgm was carried out, introducing a gentamicin-resistant nonpolar cassette in a unique EcoRV site of the B. abortus pgm gene (see Materials and Methods); the resulting mutant strain, named B. abortus B2211, was used for further studies. As can be seen in Fig. 2A, the electrophoretic profile of the LPS extracted from mutant B2211 indicates that it lacks the O antigen. However, the core region of the mutant LPS migrated in Tricine-PAGE electrophoresis in a position that was indistinguishable from that of the wild type core (Fig. 2B), thus indicating that there were minor differences between them. These results suggest that the B. abortus core LPS contains glucose or a derivative of glucose synthesized through a sugar nucleotide intermediate, and it can be speculated that the amount of glucose or derivatives present in the core is minimal in relation to the total amount of sugars (one or two units). When an immunoblot analysis was performed, anti-LPS antibodies reacted with both preparations, indicating that the compounds detected by silver staining corresponded to LPS core and retained antigenic determinants (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

PAGE of B. abortus LPS. (A) PAGE with 12% acrylamide. Lane 1, wild-type LPS; lane 2, B. abortus B2211 pgm mutant LPS. (B) Tricine-PAGE. Lane 1, wild-type LPS; lane 2, B. abortus B2211 pgm mutant LPS. Gels were silver stained.

To corroborate the rough phenotype of strain B2211, the phage Tbilisi, which infects smooth strains, was used to infect the B. abortus 2308 wild-type strain, the B. abortus B2211 pgm mutant, and the B. abortus B2211 pgm mutant complemented with plasmid pBBE30. It was observed that the wild-type strain and the complemented pgm strain were susceptible but the mutant strain B2211 was resistant, again indicating that the mutant completely lacks the LPS O antigen.

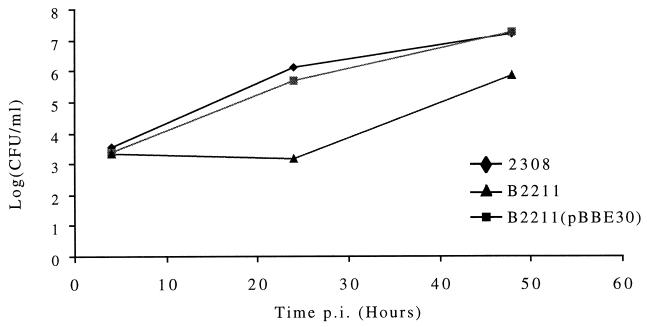

Mutant strain B2211 is able to multiple within HeLa cells.

To evaluate the importance of B. abortus smooth LPS in intracellular survival, the multiplication of the B. abortus wild-type strain 2308, the B. abortus B2211 pgm mutant, and the B. abortus B2211 pgm mutant complemented with plasmid pBBE30 was studied in HeLa cells. The number of viable bacteria was estimated at 4, 24, and 48 h after infection. At 4 h after infection, the numbers of intracellular bacteria of the three strains showed no significant differences, indicating that the rough mutant strain was internalized at the same rate as the parental strain (Fig. 3). As it can be seen in Fig. 3, at 24 and 48 h postinfection the numbers of bacteria recovered from HeLa cells infected with the B. abortus 2308 wild-type strain or with the B. abortus B2211 mutant strain complemented with plasmid pBBE30 were the same. However, the number of bacteria recovered at 48 h from cells infected with the B. abortus B2211 pgm mutant strain was approximately 1 log10 unit lower. Although the exponential intracellular replication of the pgm mutant was delayed by approximately 20 h with respect to that of the wild type, the high number of recoverable bacteria at 48 h postinfection indicates that mutant strain B2211 replicates inside HeLa host cells.

FIG. 3.

Intracellular multiplication of the B. abortus wild-type strain and the B. abortus B2211 pgm mutant in HeLa cells. Cells were infected, and at the indicated times postinfection (p.i.) the number of intracellular bacteria was determined as described in Materials and Methods.

These results indicate that smooth LPS is not essential, either for invasion of the host cell or for intracellular replication. The fact that the mutant replicates at a lower rate is not necessarily a consequence of the rough phenotype, since the absence of pgm affects many other components of the cell wall, such as, for example, the synthesis of β(1,2) cyclic glucan. It recently has been demonstrated that a B. abortus cgs (cyclic glucan synthetase) mutant has a phenotype in HeLa cells similar to that of mutant B2211 (C. G. Briones, unpublished results).

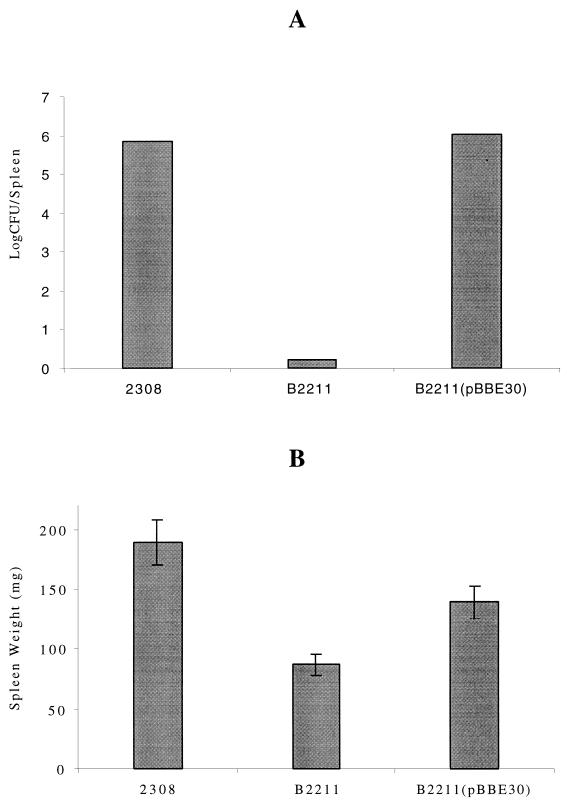

Survival of the B. abortus B2211 pgm mutant in the mouse model.

Groups of five mice were injected intraperitoneally with 105 CFU of the B. abortus B2211 pgm mutant strain, the B. abortus 2308 wild-type strain, or the B. abortus B2211 pgm mutant strain complemented with pBBE30. At 2 weeks postinoculation mice were sacrificed, and spleens were weighed and examined for Brucella proliferation. As shown in Fig. 4A, the numbers of viable bacteria recovered from spleens of mice injected with the B. abortus 2308 wild-type strain and the B. abortus B2211 pgm mutant complemented with plasmid pBBE30 were 7 × 105 and 1 × 106 CFU/ml, respectively. On the other hand, no viable bacteria were recovered from mice injected with the B. abortus B2211 pgm mutant strain, within the detection limits of the method. In Fig. 4B it can also be seen that the weights of the spleens of mice injected with the B. abortus B2211 pgm mutant strain were significantly lower than those of mice injected with the wild-type strain or with the pgm mutant complemented with plasmid pBBE30. This indicates that the inflammatory response generated by the pgm mutant was also lower than the one generated by the parental wild-type strain.

FIG. 4.

Virulence in mice. Mice were infected as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Recovery of viable bacteria from spleens at 15 days postinfection. (B) Weights of spleens of infected mice at 15 days postinfection. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

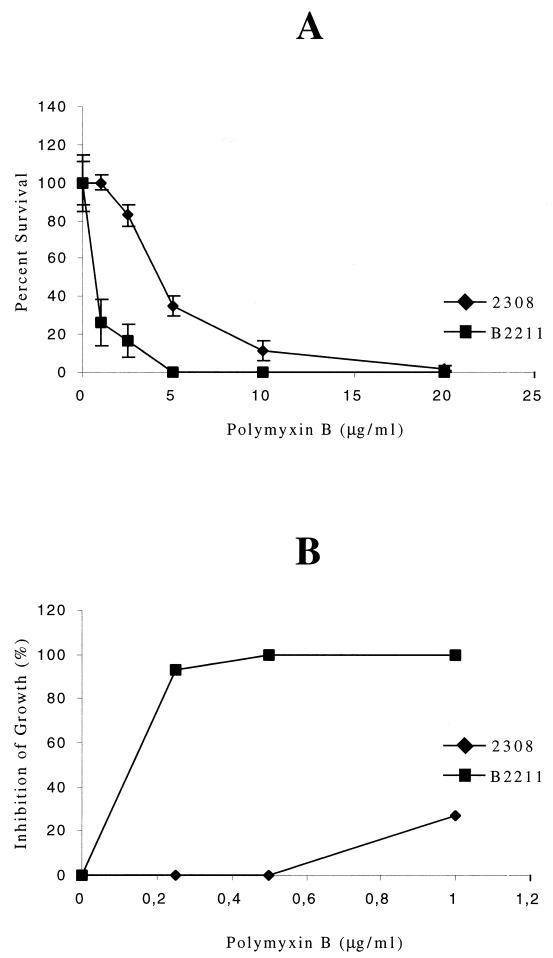

Sensitivity to PmB.

Defensins are cationic, amphipathic, low-molecular-weight peptides thought to permeabilize membranes of gram-negative organisms inside phagocytic cells (34). PmB, an amphipathic peptide that forms ionic interactions with saccharide components of LPS, including 2-keto-3-deoxyoctulonic acid and phosphate, has the greatest bactericidal effect on B. abortus (16). PmB was used as a model defensin to study the survival of the B. abortus B2211 pgm mutant. Figure 5 shows the effect of PmB on strains 2308 and B2211 tested by two different assays, as described in Materials and Methods. It can be observed that in the concentration range of 0 to 10 μg/ml, PmB has a higher bactericidal effect on strain B2211 than on the wild-type parental strain (Fig. 5A). These results indicated that, as was observed with other Brucella rough mutants, the lack of LPS O antigen increases the bactericidal effect of cationic peptides. The inhibition of growth by PmB on both strains is shown in Fig. 5B. It can be seen that PmB inhibited the growth of strain B2211 at concentration as low as 0.25 μg/ml. On the other hand, the wild-type parental strain 2308 grew at concentrations as high as 1 μg/ml. These results indicate that the concentration of PmB required for inhibition of growth is approximately 1 order of magnitude lower than the concentration required for a bactericidal effect. However, both assays clearly showed a significant difference between the B. abortus pgm mutant and the wild-type parental strain.

FIG. 5.

Effect of PmB on B. abortus strains B2211 (pgm mutant) and 2308. (A) Bactericidal effect. PmB-mediated killing was performed as described in Materials and Methods, and results are expressed as percentages of survival. (B) Inhibition of growth. The assay was carried out as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as percentages of CFU recovered at the indicated concentrations of PmB. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

In this study we have identified, sequenced, and disrupted the pgm gene of B. abortus. The predicted protein is 74.7% identical to its homologue in A. tumefaciens but is not part of the glycogen operon as it is in Agrobacterium (29, 33). This type of Pgm is specific for the synthesis of glucose sugar nucleotide derivatives like UDP-glucose or ADP-glucose, and it has no phosphomannomutase (Pmm) activity. In Agrobacterium and Brucella, Pmm is a separate protein (1, 8, 31). B. abortus LPS O antigen is a homopolymer of perosamine, a derivative of mannose that is synthesized through GDP-mannose, thus, a pgm mutant of this species would not be impaired in the synthesis of GDP-perosamine, the sugar donor of O-antigen subunits. The lack of O antigen in a B. abortus pgm mutant must be the result of incomplete synthesis of the LPS core, which was described to contain glucose. As deduced from the electrophoretic profile of LPS in SDS-PAGE and Tricine gels, the mutant has an almost complete core, which indicates that it is not formed primarily by glucose as has been previously reported (17). One possible explanation for these differences is that the preparations used to characterize the O antigen and the core were contaminated with β(1,2) cyclic glucan, since it has been reported that this polysaccharide strongly interacts with B. abortus LPS (3, 6, 14).

In mice the mutant was completely cleared from the spleens at 15 days postinoculation, thus indicating that it had lost virulence. However, the ability to multiply intracellularly in HeLa cells, although delayed compared to that of the wild type, was not abolished, indicating that intracellular multiplication is necessary but not sufficient for virulence. The impairment of the mutant in the synthesis of UDP-glucose results in the inability to produce other polymers containing glucose, including β(1,2) cyclic glucan. In our laboratory we have recently observed that a B. abortus β(1,2) cyclic glucan synthetase (cgs) mutant also showed a delay in exponential intracellular replication (C. G. Briones, unpublished results). Thus, it is possible that this phenotype might be the result of the absence of β(1,2) cyclic glucan rather than of the lack of O antigen. Despite this delay, the B. abortus pgm mutant replicated in HeLa cells, reaching 7 × 105 bacteria/ml, which indicates that the O antigen is not essential either for invasion or for intracellular multiplication.

Many reports have analyzed the phenotypes of rough mutants that were fortuitously isolated. Two important features often analyzed in rough mutants are survival in mice and intracellular replication in professional or nonprofessional phagocytes. It has been proposed that rough mutants are less virulent due to two causes: high sensitivity to lysis mediated by complement and inability to replicate intracellularly. It has been demonstrated that the lack of O antigen in Brucella increases bacterial sensitivity to the killing activities of complement (7). On the other hand the inability of rough strains to replicate inside the cell is not a solved issue. Some rough mutants have been reported to be unable to replicate inside professional phagocytes (22, 23, 27), but there are some reports that have demonstrated that rough mutants with well-characterized genetic backgrounds and parental strains have no significant differences in their ability to replicate in macrophages (1, 9).

The fact that a mutant lacking the O antigen did not loose the ability to replicate inside the cells indicates that a complete LPS is not essential for either invasion or protection of Brucella against the cellular defenses of the host. One possible explanation for the discrepancies among different reports is that many of the rough mutants used to study this phenotype were fortuitously isolated and are not genetically characterized, thus possibly leading to incorrect conclusions.

Historically the search for rough mutants was done in two ways: by a spontaneous phenomenon known as phase variation, in which rough variants appear in culture by a mechanism not well understood (2, 10), or by successive passages in different culture media with searching for spontaneously rough phenotypes. These procedures gave a high number of rough mutants. All of them are avirulent in animal models, but in most cases the parental strain is not available. When the capacity of these mutants to replicate in professional or nonprofessional cells is analyzed, the results must be interpreted very carefully. We conclude that the incapacity to multiply inside the cell is not a consequence of the rough phenotype but rather is determined by a complex interaction between the bacteria and the cells.

The main drawback a of live B. abortus S19 vaccine is the induction of antibodies against the O antigen, which causes difficulties in diagnosis in eradication campaigns carried out with vaccination. The intracellular multiplication of this mutant, associated with the inability to survive in mice and the lack of O-antigen determinants, might be important in consideration of this mutant as a potential live vaccine for cattle. Protection induced by this mutant strain is under study in our laboratory.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Técnica, SECyT, Argentina, (PICT98 no. 01-04180 and PICT97 no. 01-00080-01767). J.E.U. and C.C. are fellows of the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, CONICET, Argentina. M.F.F. is a fellow of the Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica. R.A.U. is a member of the research carrier of the CONICET, Argentina.

We acknowledge Diego Comerci and Rodrigo Sieira, University of General San Martín, for useful suggestions; Fabio Fraga, University of General San Martín, for technical assistance; Patricia Silvapaulo for kindly providing PmB; and J. J. Cazzulo, University of General San Martín, for critical reading of the manuscript and useful suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen C A, Adams L G, Ficht T A. Transposon-derived Brucella abortus rough mutants are attenuated and exhibit reduced intracellular survival. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1008–1016. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1008-1016.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brawn W. Bacterial dissociation. Bacteriol Rev. 1947;11:75–114. doi: 10.1128/br.11.2.75-114.1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bundle D R, Cherwonogrodzky J W, Perry M B. Characterization of Brucella polysaccharide B. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1101–1106. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.5.1101-1106.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cangelosi G A, Hung L, Puvanesarajah V, Stacey G, Ozga D A, Leigh J A, Nester E W. Common loci for Agrobacterium tumefaciens and Rhizobium meliloti exopolysaccharide synthesis and their roles in plant interactions. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2086–2091. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.5.2086-2091.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caroff M, Bundle D R, Perry M B, Cherwonogrodzky J W, Duncan J R. Antigenic S-type lipopolysaccharide of Brucella abortus 1119-3. Infect Immun. 1984;46:384–3828. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.2.384-388.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherwonogrodzky J W, Nielsen K H. Brucella abortus 1119-3 O-chain polysaccharide to differentiate sera from B. abortus S-19-vaccinated and field-strain-infected cattle by agar gel immunodiffusion. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1120–1123. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.6.1120-1123.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corbeil L B, Blau K, Inzana T J, Nielsen K H, Jacobson R H, Corbeil R R, Winter A J. Killing of Brucella abortus by bovine serum. Infect Immun. 1988;56:3251–3261. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.12.3251-3261.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foulongne V, Bourg G, Cazevieille C, Michaux-Charachon S, O'Callaghan D. Identification of Brucella suis genes affecting intracellular survival in an in vitro human macrophage infection model by signature-tagged transposon mutagenesis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1297–1303. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1297-1303.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Godfroid F, Taminiau B, Danese I, Denoel P, Tibor A, Weynants V, Cloeckaert A, Godfroid J, Letesson J J. Identification of the perosamine synthetase gene of Brucella melitensis 16M and involvement of lipopolysaccharide O side chain in Brucella survival in mice and in macrophages. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5485–5493. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5485-5493.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henry B S. Dissociation in the genus Brucella. J Infect Dis. 1933;52:374–402. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoyer B H, McCullough N B. Homologies of deoxyribonucleic acids from Brucella ovis, canine abortion organisms, and other Brucella species. J Bacteriol. 1968;96:1783–1790. doi: 10.1128/jb.96.5.1783-1790.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inon de Iannino N, Briones G, Tolmasky M, Ugalde R A. Molecular cloning and characterization of cgs, the Brucella abortus cyclic beta(1-2) glucan synthetase gene: genetic complementation of Rhizobium meliloti ndvB and Agrobacterium tumefaciens chvB mutants. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4392–4400. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4392-4400.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kovach M E, Elzer P H, Hill D S, Robertson G T, Farris M A, Roop R M, 2nd, Peterson K M. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene. 1995;166:175–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.L'vov V I, Pluzhnikova G N, Lapina E B, Shashkov A S, Askerova S A, Malikov V E, Dranovskaya E A, Dmitriev B A. Molecular nature of the polysaccharide B antigen from Brucella (poly-B) Bioorgan Khim. 1987;13:4070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marolda C L, Welsh J, Dafoe L, Valvano M A. Genetic analysis of the O7-polysaccharide biosynthesis region from the Escherichia coli O7:K1 strain VW187. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3590–3599. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3590-3599.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinez de Tejada G, Pizarro-Cerda J, Moreno E, Moriyon I. The outer membranes of Brucella spp. are resistant to bactericidal cationic peptides. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3054–3061. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3054-3061.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreno E, Speth S L, Jones L M, Berman D T. Immunochemical characterization of Brucella lipopolysaccharides and polysaccharides. Infect Immun. 1981;31:214–222. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.1.214-222.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osborn M J. Studies in the Gram-negative cell wall. I. Evidence for the role of 2-keto-3-deoxyoctonoate in the lipopolysaccharide of Salmonella typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1963;50:499–506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.50.3.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pizarro-Cerda J, Meresse S, Parton R G, van der Goot G, Sola-Landa A, Lopez-Goni I, Moreno E, Gorvel J P. Brucella abortus transits through the autophagic pathway and replicates in the endoplasmic reticulum of nonprofessional phagocytes. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5711–5724. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5711-5724.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pizarro-Cerda J, Moreno E, Sanguedolce V, Mege J L, Gorvel J P. Virulent Brucella abortus prevents lysosome fusion and is distributed within autophagosome-like compartments. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2387–2392. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2387-2392.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pizarro-Cerda J, Moreno E, Gorvel J P. Advances in cell and molecular biology of membranes and organelles. Vol. 6. New York, N.Y: JAI Press Inc.; 1999. Brucella abortus invasion and survival within professional and non-professional phagocytes; pp. 201–232. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riley L K, Robertson D C. Brucellacidal activity of human and bovine polymorphonuclear leukocyte granule extracts against smooth and rough strains of Brucella abortus. Infect Immun. 1984;46:231–236. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.1.231-236.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riley L K, Robertson D C. Ingestion and intracellular survival of Brucella abortus in human and bovine polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Infect Immun. 1984;46:224–230. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.1.224-230.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roantree R J. The relationship of lipopolysaccharide to bacterial virulence. In: Weinbaum G, Kadis S, Ajl S J, editors. Microbial toxins: a comprehensive treatise. Vol. 5. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1971. pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schagger H, von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schurig G G, Roop R M d, Bagchi T, Boyle S, Buhrman D, Sriranganathan N. Biological properties of RB51; a stable rough strain of Brucella abortus. Vet Microbiol. 1991;28:171–188. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(91)90091-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tarof C W, Hobbs C A. Improved media for growing plasmid and cosmid clones. Focus. 1987;9:12. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ugalde J E, Lepek V, Uttaro A, Estrella J, Iglesias A, Ugalde R A. Gene organization and transcription analysis of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens glycogen (glg) operon: two transcripts for the single phosphoglucomutase gene. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6557–6564. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6557-6564.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ugalde R A. Intracellular lifestyle of Brucella spp.: common genes with other animal pathogens, plant pathogens, and endosymbionts. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:1211–1219. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)00240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uttaro A, Ielpi L, Ugalde R A. Galactose metabolism in Rhizobiaceae. Characterization of exoB mutants. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:1055–1062. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uttaro A D, Cangelosi G A, Geremia R A, Nester E W, Ugalde R A. Biochemical characterization of avirulent exoC mutants of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1640–1646. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.3.1640-1646.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uttaro A D, Ugalde R A. A chromosomal cluster of genes encoding ADP-glucose synthetase, glycogen synthase and phosphoglucomutase in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Gene. 1994;150:117–122. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90869-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vaara M. Agents that increase the permeability of the outer membrane. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:395–411. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.3.395-411.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verger J M, Grimont F, Grimont P A D, Grayon M. Brucella, a monospecific genus as shown by deoxyribonucleic acid hybridization. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1985;35:292–295. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Westphal O, Jann K. Bacterial lipopolysaccharides. Methods Carbohydr Chem. 1965;5:83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woodcock D M, Crowther P J, Doherty J, Jefferson S, DeCruz E, Noyer-Weidner M, Smith S S, Michael M Z, Graham M W. Quantitative evaluation of Escherichia coli host strains for tolerance to cytosine methylation in plasmid and phage recombinants. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:3469–3478. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.9.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]