Abstract

Background

In people with celiac disease (CD), many factors affect adherence to a gluten-free diet (GFD), and these may well differ among countries. In Greece, such data for the adult population are lacking. Thus, the present study aimed to explore the perceived barriers to compliance with a GFD that are faced by people with CD living in Greece, also taking into account the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

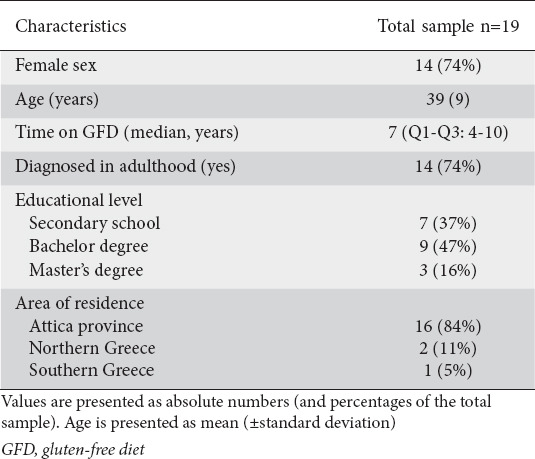

Nineteen adults (14 females) with biopsy-proven CD, mean age 39±9 years and median time on GFD 7 (Q1-Q3: 4-10) years, participated in 4 focus groups, conducted through a video conference platform during the period October 2020 to March 2021. Data analysis followed the qualitative research methodology.

Results

Eating outside the home was reported as the domain where most difficulties were faced: these were related to a lack of confidence in finding safe gluten-free food and to the lack of social awareness about CD/GFD. All participants highlighted the high cost of gluten-free products, which was mostly managed by receiving state financial support. Regarding healthcare, the vast majority of participants reported little contact with dietitians and no follow up. The COVID-19 pandemic eased the burden of eating out, as staying at home and allocating more time to cooking was experienced as a positive effect, although the shift to online food retailing impacted food variability.

Conclusion

The main impediment to GFD adherence seems to stem from low social awareness, while the involvement of dietitians in the healthcare of people with CD warrants further investigation.

Keywords: Gluten-free diet, barriers, adherence, COVID-19, focus groups

Introduction

The current available treatment for people with celiac disease (CD) is a gluten-free (GF) diet (GFD), a dietary regimen that needs to be followed long-term [1]. Adherence rates to this strict diet often vary considerably [2], because of the challenges it poses to an individual’s daily life. Many studies have explored a variety of factors affecting adherence to GFD. Adults and adolescents alike have reported challenges in everyday life related to, among other things, food availability, cost and labeling, negative emotions experienced, and the impact on their relationships [3]. Systematically reviewing the barriers and facilitators associated with GFD adherence, Abu-Janb and Jaana classified them into levels, based on a socioecological model [4]. From the micro- to the macro-environmental level, these are the individual, the interpersonal, the organizational, the community and the system level. Lack of knowledge about CD/GFD, social fear, restaurant dining and supermarket shopping, poor patient education and lack of physician–patient communication have been reported as the most important barriers [4].

While these barriers may share some common characteristics across countries and populations, they are highly country-specific, as societal background, economic status, legislation and health system structure directly or indirectly formulate the conditions that impede or facilitate adherence to a GFD. For example, availability and cost of GF products (GFP), the presence of a state system for GFP cost coverage or CD-referral centers, GFD awareness in food establishments, and a general CD-friendly culture, all may vary among countries, and their importance as potential barriers to following GFD may be perceived differently by people living with CD.

Thus, exploring these factors at a local level can still make a valuable contribution to the field. In Greece, there is a paucity of data regarding factors influencing GFD adherence. An early study in children with biopsy-confirmed CD found that more than half of them were adherent to GFD, with poor palatability, dining outside the home and poor availability of products listed among the main reasons for non-compliance [5]. However, there has been no previous study of the factors influencing GFD adherence in adults with CD in Greece. Furthermore, all the aspects of life that had previously been described as factors affecting GFD adherence were potentially influenced by the unprecedented phenomenon of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, studies have reported that the pandemic both impeded GF food availability and affected its cost [6,7].

Quantitative research methodologies are usually applied to illustrate the factors affecting GFD adherence: i.e., the vast majority of the relevant studies are based on on-line surveys [4]. However, in order to capture country-specific characteristics, qualitative research provides the advantage of exploring the factors beyond the limits of a pre-defined questionnaire [8], especially since there are no previous similar data, and new areas of interest may emerge. In this respect, qualitative research precedes a quantitative study design, e.g., one aiming to correlate factors affecting GFD adherence with parameters related to CD status or dietary habits.

Taking into account the findings of a recent systematic review of the common barriers to GFD adherence [4] and the need to study them at a country-specific level, the lack of such data in the Greek adult population, as well as the fact that the current COVID-19 pandemic has greatly influenced healthcare provision for many chronic non-communicable diseases [9], the aim of the present study was to explore the barriers and difficulties adults with CD face in their everyday lives in Greece. A supplementary goal was to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on these patients. To this end, the qualitative research methodology of focus groups was chosen, which permits studying participants’ opinions, thoughts and experiences within a “least-guided” context [10].

Patients and methods

Inclusion criteria

The sample was collected in collaboration with the National Celiac Association, employing dissemination through social media. The criteria for inclusion were participants being over 18 years old, diagnosed with CD through biopsy, and having followed a GFD for at least 1 year. Participants were asked for basic socio-demographic information, a brief CD history, and written consent to voluntary participation in the study. The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Harokopio University of Athens.

Focus groups technique

Focus groups are an interview-type technique for collecting qualitative data [10]. This technique is often used to detect problems that arise from the experiences of a group of people who share a common characteristic [11], while it allows volunteers to share their views in a comfortable and permissive context, without limiting their answers to predefined questions, as for example with a questionnaire [8]. The use of this methodology in the present study was, therefore, considered the most appropriate to serve its aim: namely, to highlight the barriers that people with CD face in regard to their adherence to GFD. The structure of the focus group discussion followed relevant methodology recommendations concerning the development of the questions and the flow of the discussion [8]. After a couple of introductory short questions on the participants’ difficulties in following GFD, the questions focused on the objective of the study: i.e., the different domains of everyday life where possible barriers to dietary adherence could emerge. Although the questions asked were open, there was some guidance by the moderator to ensure that a wide range of aspects would be discussed. The core question asked in which domains of life the participants felt they encountered difficulties adhering to GFD: eating out (recreational, at workplace), relationships (family/friends, social networks, society awareness), the GFP market (availability, cost, labeling), healthcare (health professionals, dietitians, state financial support, sources of knowledge), other social activities (e.g., traveling), and lastly whether and how the COVID-19 pandemic may have impacted on these domains.

Data collection and analysis

Data collection and sample size were defined following the saturation criterion: that is, stopping data collection when answers are essentially repeated, with no additional point of view arising, so that there is no need for another focus group to be constructed [8,12]. Based on relevant recommended methodology about the group size, small groups were formed, so as to find a balance between achieving a good diversity of opinions and giving each participant the opportunity to express themselves [8]. In our study, because of the measures necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic, the focus groups were conducted remotely, via a video conferencing platform. On the plus side, this allowed volunteers to participate independently of their location. Hence, people of both sexes, diagnosed during either childhood or adulthood, and living in or outside the province of Attica, were invited to participate, with a view to obtaining a wider spectrum of opinions.

During the focus groups sessions, there was a moderator for the flow of the questions and the discussion, and an assistant who kept detailed notes to support the analysis of the discussion. The conversation was recorded and transcribed. Multiple pass readings of the transcripts allowed meaningful grouping of themes, formulating a theme when sufficient data existed to describe it, identifying connectivity between themes, revisiting this mapping, and finally organizing data into a story [13]. In addition, a critical view was adopted for the interpretation of the data, sometimes including the need to read between the lines [14].

Results

In total, 19 people with CD (14 women), all of Caucasian origin, participated in 4 focus groups of 1-h duration each, conducted between October 2020 and March 2021. The main descriptive characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the sample

During the introductory discussion, participants were asked to describe how their lives had changed because of the need to follow a GFD, as well as the difficulties they faced in this respect. They all agreed that adherence during the first years after diagnosis was more difficult, while most had otherwise adapted well to the demands of GFD. The majority of participants reported that, while many aspects of their life had been affected, they had also complied with these changes and with living with CD, especially those who counted many years since their diagnosis and those who were diagnosed during childhood.

Eating out emerged as the most important barrier to following a GFD. Eating occasions for recreation, at the workplace, or even at friends’ homes, presented the participants with different degrees of difficulty. The magnitude of the difficulty was related to the time since diagnosis and the area of residence: the first years following diagnosis could involve substantial abstinence from social events, while people living in the provinces consistently reported more barriers related to social life. These limitations seemed to be mainly attributed to the fear of contamination and the lack of trust in others to prepare safe GF food, with women generally expressing more fear of unvoluntary gluten consumption. Even though participants recognized that restaurant staff’s awareness of CD had increased over time, along with the availability of GF food, they expressed special concerns about the caterers’ knowledge or the conditions inside a restaurant kitchen. However, participants said they managed to cope with such situations by talking a lot with the caterers or by limiting their food choices. Participants also expressed dissatisfaction and frustration at receiving generally adverse reactions from people who were unaware of CD and its dietary restraints, and facing more barriers to accessing safe GF food compared to many destinations abroad.

Commenting on the GFP market in general, many participants stated that they tried to avoid consumption of packaged ready-to-eat GFP, given their poor nutritional value. However, more reliance on such products is evident during the first years of diagnosis or when many hours are spent away from home. Participants unanimously agreed that GFP availability has increased enormously compared to the past. Some find that they still have limited choices, especially in supermarkets, whereas in other specialty food stores, such as those with organic products, the variety is greater. They also agreed that one can trust only certified products, even though there was some disagreement as to what a certified product is. Nevertheless, they expressed a kind of mistrust regarding GFP labeling, due to the fear of contamination. Participants pointed out the high cost of GFP, commenting that even though prices are much lower than in the past, GFP still remain much more costly than their conventional counterparts. Some volunteers also highlighted the disproportionate relationship between the products’ cost and quantity. As a means to counterbalance this barrier, most of the participants make use of the state financial support provided, an allowance especially appreciated by families with more than one member living with CD. However, the bureaucratic requirements for claiming reimbursement still discourage some volunteers from applying. It was evident, though, that not using the benefit led to a restriction of the individuals’ food choices.

Discussion of contact with healthcare professionals—especially with dietitians, as being of special interest to our research team—revealed that this tended to be limited to the time of diagnosis. After referral by gastroenterologists, dietitians may offer the initial guidance as to what one should eat and information on the existence of special products in the market, which volunteers assessed as helpful and supportive. However, a lack of follow-up contact was the rule, apparently attributable mainly to the belief that no such need ultimately exists. Those who had visited a dietitian beyond the diagnosis either stated it was necessitated by bureaucratic issues (i.e., getting the prescription needed for receiving state financial support), or were rather disappointed with the experience. There were cases when the participants felt the dietitian lacked expertise on CD or could not provide any additional advice, mainly meaning tasty food alternatives. Nevertheless, some had found visiting a dietitian helpful when it came to another health issue, for example diabetes comorbidity. As healthcare professionals are a rather limited ongoing source of knowledge about GFD, this role has been taken up by the internet, and particularly Facebook. Participants admitted they tried to get organized in groups, e.g., through blogs, social media or local communities (especially in the provinces), to share knowledge and address questions and problems related to CD/GFD.

Commenting on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the above aspects, participants identified the affected domains as “eating out in restaurants”, “food provision” and “social gatherings”. In general, a rather neutral effect was evident, with many volunteers stating that nothing had really changed specifically in terms of CD and GFD. Interestingly, the burden of eating out in everyday life was nullified during the COVID-19 pandemic, which explains why many participants perceived it as having a positive effect on their ability to adhere to the GFD. This perception was essentially the result of the lockdowns, which led to more cooking and having control of food preparation. Even when restaurants reopened, some noticed a positive change in their functioning conditions due to the measures imposed against the spread of the virus: namely, less crowded places, cutlery set pack provided, and more attention generally paid to the client and his/her needs. Regarding the state reimbursement, no delays were faced in the request submission or process, though food provision was impeded, as the mode of supply during the lockdowns turned necessarily from face-to-face to e-shopping. This change in turn often led to more limited variability of the foodstuffs ordered. For those living in remote areas, getting supplies was more burdensome, as travelling to the capital for shopping was forbidden and delays in delivery were very common. Ordering food at friends’ gatherings was also recognized as a barrier during the lockdowns, given the paucity of GF choices in this respect.

Discussion

The present study explored the perceived barriers to following GFD for adults with CD living in Greece, and further evaluated the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The most important factors experienced as barriers by the participants in daily life were related to social life, the GFP market, and the healthcare system. It appears that low social awareness is the main source of difficulties that people with CD face when dining out. Confusion with GFP labeling and bureaucratic burdens to claiming reimbursement were also reported, while a low degree of involvement of dietitians in the healthcare of people with CD was also evident. Conditions experienced during the recent pandemic did not seem to substantially alter perceived barriers.

Social activities involving eating were identified as the domain that poses the most difficulties for adhering to GFD. Availability of safe GF food in restaurants is seen as challenging, and participants are reluctant when they encounter an eating occasion outside home. In accordance with our findings, Lee et al found that social activities and dining out were the most frequently reported areas of life to be negatively affected [15]. In fact, dining out remained the most impacted domain, regardless of the time since diagnosis, though to a diminishing degree with increasing years after diagnosis. Other studies have also identified social and leisure activities, including eating out, as a barrier to GFD adherence [16,17] and a factor impacting quality of life [18]. Viewed on a larger scale, this feeling of doubt and anxiety essentially reflects low societal awareness. Ultimately, social awareness translates not only to more knowledgeable restaurant services and easier access to GFP, but also to a more friendly environment for communicating one’s dietary restrictions [4].

Surprisingly for a treatment that exclusively relies on dietary management, we found that contact with dietitians is rare. Guidelines recognize regular follow-up in a specialist celiac clinic, by both a gastroenterologist and a dietitian, as important for improving dietary adherence [1], and experts suggest that education about GFD should fall within the domain of a dietitian, who may address the difficulties in engaging in GF living, as opposed to the work for which medical doctors are responsible [19], while the role of the dietitian in CD treatment extends beyond gluten issues per se, to address the overall diet quality relative to the comorbidities that may arise [20]. Indeed, regular dietetic follow up has been proven effective in enhancing not only perceived [21], but also objectively measured [22] GFD adherence. Even though there are findings showing a high percentage of contact with dietitians [17,21,23], an inadequate dietetic follow up or dissatisfaction with the information provided has commonly been recorded [24-27], including in the pediatric CD population in Greece [5]. Participants in our sample reported having received much support from health professionals in the peri-diagnosis period, yet their follow-up meetings mainly serve bureaucratic issues. The reason for not being followed-up appears to be the belief that there is no such need, as patients manage on their own, obtaining the needed information via the internet or within patients’ networks. According to our findings, self-management and a feeling that the provider was not knowledgeable, or that previous visits were not helpful, were the most frequent reasons for not seeing a healthcare provider at follow-up [28]. An unfortunate lack of communication post-diagnosis was also the conclusion of Abu-Janb and Janna [4]. In Greece, the lack of CD referral centers and the lack of national GFP catalogues constitute an important pitfall in healthcare provision for people with CD, who often resort to untrustworthy sources of information about GFD.

The COVID-19 pandemic affected everyday life in multiple ways, imposing limitations of varying degree on commuting, running of restaurants, retail services, private sector and civil services, most strictly during the lockdowns (in Greece, twice: March-May 2020, and November 2020 to May 2021). Interestingly, in our sample, the majority of the participants reported a rather neutral effect of the COVID-19 measures as far as following GFD was concerned, while some even indicated positive changes. The latter actually stemmed from staying at home, thus engaging more in cooking and eating more healthily with naturally GF food, while at the same time avoiding risky meals at restaurants. Our findings seem to agree with those of an Italian study, where 70% of people with CD surveyed reported unchanged dietary habits, and one third of them an improvement, attributed mainly to not eating away from home (75%) and having more time to prepare food (40%) [29]. In fact, experts on CD had suggested that the condition of staying at home during the COVID-19 era could be seen as a chance to eat more healthily, trying to follow a Mediterranean-based GFD involving more cooking with naturally GF ingredients [30]. However, it remains a challenge whether these positive aspects that emerged from the pandemic could be maintained. Participants in the present study also stated they did not face any difficulties regarding food availability, affordability or cost, with the exception of food provision. Restrictions in commuting in conjunction with online orders resulted in difficulties getting food supplies and a limitation in food variety, especially for those living in the provinces. Contrary to our results, food availability was hampered in some parts of the world [7,31].

Our study is the only relevant one in Greece to explore factors affecting GFD adherence in adults. Given that these factors are highly country-specific, referring to organizational, governmental, financial, social and cultural domains, it is important to portray the particular status of a country, in order to focus on the development of specific action measures. Moreover, the present study is among the few in the current literature to address the COVID-19 period as a potential barrier to GFD adherence.

The methodology of focus groups chosen for this study was considered a proper tool to serve our objectives. However, there were some limitations. First of all, the true adherence to GFD was not measured. This would permit investigating correlations and finding out whether the perceived difficulties had indeed impacted dietary compliance, but our intention was to perform a qualitative study to record the amplitude of factors participants would name, with minimum involvement by the researchers. Nevertheless, our findings may not be generalizable for the population with CD in Greece, as our participants were of a rather high educational level and probably highly motivated, based on the researchers’ critical view during the contacts.

In conclusion, in the present study we investigated the barriers to GFD adherence faced by adults with CD living in Greece. Our overall findings are in accordance with those in the relevant literature from other countries. However, the general lack of follow-up and low reliance on dietitians for receiving guidance about GFD should alert the healthcare community. Actions that could be taken in this regard may aim, on the one hand, at fostering dietetic practice, for example through seminars on GFD, urging dietitians to adopt more merit in patients care, and enforcing collaboration between gastroenterologists and dietitians, and on the other hand, at raising patients’ awareness, for example through campaigns about the importance of active follow-up. Ultimately, a discussion about revising some aspects of healthcare provision to people with CD could be initiated at a national level.

Summary Box

What is already known:

For people with celiac disease (CD), many barriers to adhering to a gluten-free diet (GFD) have been recognized, ranging from the individual to the systemic

These barriers depend on cultural and economic backgrounds; thus, studying them in different countries and populations is still of interest

Literature on the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on GFD adherence and perceived barriers is scarce

What the new findings are:

In Greece, the main burden to GFD adherence for adults living with CD seems to stem from low social awareness

A general lack of dietitians’ involvement in healthcare provision to people with CD was evident

Practical implications of the present study include fostering dietetic practice and patients’ awareness

The COVID-19 pandemic seems to have impacted rather neutrally on GFD adherence perception

Acknowledgment

We would like to cordially thank Mr. Konstantinos Petsis, Dietitian-Nutritionist, for his kind contribution to the study implementation.

Biography

Harokopio University of Athens, Greece

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

References

- 1.Al-Toma A, Volta U, Auricchio R, et al. European Society for the Study of Coeliac Disease (ESsCD) guideline for coeliac disease and other gluten-related disorders. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:583–613. doi: 10.1177/2050640619844125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall NJ, Rubin G, Charnock A. Systematic review:adherence to a gluten-free diet in adult patients with coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:315–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White LE, Bannerman E, Gillett PM. Coeliac disease and the gluten-free diet:a review of the burdens;factors associated with adherence and impact on health-related quality of life, with specific focus on adolescence. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2016;29:593–606. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abu-Janb N, Jaana M. Facilitators and barriers to adherence to gluten-free diet among adults with celiac disease:a systematic review. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2020;33:786–810. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roma E, Roubani A, Kolia E, Panayiotou J, Zellos A, Syriopoulou VP. Dietary compliance and life style of children with coeliac disease. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2010;23:176–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2009.01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du N, Mehrotra I, Weisbrod V, Regis S, Silvester JA. Survey-based study on food insecurity during COVID-19 for households with children on a prescribed gluten-free diet. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:931–934. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehtab W, Chauhan A, Agarwal A, et al. Impact of corona virus disease 2019 pandemic on adherence to gluten-free diet in Indian patients with celiac disease. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2021;40:613–620. doi: 10.1007/s12664-021-01213-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups:A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 5th ed. USA: Sage; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang AY, Cullen MR, Harrington RA, Barry M. The impact of novel coronavirus COVID-19 on noncommunicable disease patients and health systems:a review. J Intern Med. 2021;289:450–462. doi: 10.1111/joim.13184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Draper A, Swift JA. Qualitative research in nutrition and dietetics:data collection issues. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24:3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2010.01117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Traynor M. Focus group research. Nurs Stand. 2015;29:44–48. doi: 10.7748/ns.29.37.44.e8822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finset A. Qualitative methods in communication and patient education research. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell K, Orr E, Durepos P, et al. Reflexive thematic analysis for applied qualitative health research. Qual Rep. 2021;26:2011–2028. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salmon P, Young B. Qualitative methods can test and challenge what we think we know about clinical communication - if they are not too constrained by methodological 'brands'. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101:1515–1517. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee AR, Ng DL, Diamond B, Ciaccio EJ, Green PH. Living with coeliac disease:survey results from the U. S. A. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2012;25:233–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2012.01236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith MM, Goodfellow L. The relationship between quality of life and coping strategies of adults with celiac disease adhering to a gluten-free diet. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2011;34:460–468. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0b013e318237d201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zarkadas M, Cranney A, Case S, et al. The impact of a gluten-free diet on adults with coeliac disease:results of a national survey. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2006;19:41–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2006.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Black JL, Orfila C. Impact of coeliac disease on dietary habits and quality of life. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24:582–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2011.01170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barratt SM, Leeds JS, Sanders DS. Quality of life in coeliac disease is determined by perceived degree of difficulty adhering to a gluten-free diet, not the level of dietary adherence ultimately achieved. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2011;20:241–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dennis M, Lee AR, McCarthy T. Nutritional considerations of the gluten-free diet. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2019;48:53–72. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butterworth JR, Banfield LM, Iqbal TH, Cooper BT. Factors relating to compliance with a gluten-free diet in patients with coeliac disease:comparison of white Caucasian and South Asian patients. Clin Nutr. 2004;23:1127–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rajpoot P, Sharma A, Harikrishnan S, Baruah BJ, Ahuja V, Makharia GK. Adherence to gluten-free diet and barriers to adherence in patients with celiac disease. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2015;34:380–386. doi: 10.1007/s12664-015-0607-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silvester JA, Weiten D, Graff LA, Walker JR, Duerksen DR. Is it gluten-free?Relationship between self-reported gluten-free diet adherence and knowledge of gluten content of foods. Nutrition. 2016;32:777–783. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferster M, Obuchowicz A, Jarecka B, Pietrzak J, Karczewska K. Difficulties related to compliance with gluten-free diet by patients with coeliac disease living in Upper Silesia. Pediatr Med Rodz. 2015;11:410–418. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall NJ, Rubin GP, Charnock A. Intentional and inadvertent non-adherence in adult coeliac disease. A cross-sectional survey. Appetite. 2013;68:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herman ML, Rubio-Tapia A, Lahr BD, Larson JJ, Van Dyke CT, Murray JA. Patients with celiac disease are not followed up adequately. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:893–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zarkadas M, Dubois S, MacIsaac K, et al. Living with coeliac disease and a gluten-free diet:a Canadian perspective. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2013;26:10–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2012.01288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hughey JJ, Ray BK, Lee AR, Voorhees KN, Kelly CP, Schuppan D. Self-reported dietary adherence, disease-specific symptoms, and quality of life are associated with healthcare provider follow-up in celiac disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:156. doi: 10.1186/s12876-017-0713-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monzani A, Lionetti E, Felici E, et al. Adherence to the gluten-free diet during the lockdown for COVID-19 pandemic:a web-based survey of Italian subjects with celiac disease. Nutrients. 2020;12:3467. doi: 10.3390/nu12113467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elli L, Barisani D, Vaira V, et al. How to manage celiac disease and gluten-free diet during the COVID-19 era:proposals from a tertiary referral center in a high-incidence scenario. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:387. doi: 10.1186/s12876-020-01524-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bascuñán KA, Rodríguez JM, Osben C, Fernández A, Sepúlveda C, Araya M. Pandemic effects and gluten-free diet:an adherence and mental health problem. Nutrients. 2021;13:1822. doi: 10.3390/nu13061822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]