Abstract

Characterizing the physiological response of bacterial cells to antibiotic treatment is crucial for the design of antibacterial therapies and for understanding the mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. While the effects of antibiotics are commonly characterized by their minimum inhibitory concentrations or the minimum bactericidal concentrations, the effects of antibiotics on cell morphology and physiology are less well characterized. Recent technological advances in single-cell studies of bacterial physiology have revealed how different antibiotic drugs affect the physiological state of the cell, including growth rate, cell size and shape, and macromolecular composition. Here we review recent quantitative studies on bacterial physiology that characterize the effects of antibiotics on bacterial cell morphology and physiological parameters. In particular, we present quantitative data on how different antibiotic targets modulate cellular shape metrics including surface area, volume, surface-to-volume ratio and the aspect ratio. Using recently developed quantitative models, we relate cell shape changes to alterations in the physiological state of the cell, characterized by changes in the rates of cell growth, protein synthesis and proteome composition. Our analysis suggests that antibiotics induce distinct morphological changes depending on their cellular targets, which may have important implications for the regulation of cellular fitness under stress.

Introduction

The effects of antibiotics are commonly characterized by how well they prevent bacterial growth or how effectively they kill bacteria, using the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) or the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) as major metrics of antibiotic susceptibility [1, 2]. However, the cellular response to antibiotics is a more complex process – a bacterial cell could alter its growth rate, morphology, cellular composition, and other physiological characteristics, depending on the mechanism of action and the concentration of the antibiotic used. A more detailed understanding of the physiological response to antibiotic treatment could help us better characterize the fundamental properties of the cellular network, and provide insights into mechanisms of antibiotic tolerance and resistance.

In recent years, studying bacterial growth under sublethal dosages of antibiotics significantly advanced our knowledge of basic growth physiology [3–5]. For example, by examining the growth rate and proteome composition of Escherichia coli cells under the action of ribosome-targeting antibiotic chloramphenicol, a series of fundamental principles of cellular resource allocation have been revealed [3, 6]. The key difference in such experimental settings from measuring the MIC through growth inhibition curves is to maintain balanced growth of a bacterial culture under sublethal antibiotic dosages. The gradual, dosage-dependent changes in the steady-state cellular behaviors can thus be quantified in a highly reproducible manner, with a precision sufficient to test quantitative models with subtle differences.

Cell morphology is another important physiological trait which is intimately linked to cell growth and fitness [4, 5, 7–10]. Under the action of different antibiotics, bacterial cells undergo morphological changes, including changes in cell size, curvature, aspect ratio, and the surface-to-volume ratio [4, 5, 10–20]. Changes in cell morphology may be indicative of the antibacterial mechanism of action, such as spheroplast formation by inhibition of peptidoglycan synthesis [11, 21], or filamentation induced by inhibition of DNA synthesis [22, 23]. Morphological changes may also reveal the underlying physiological principles of the bacterial cell [4, 5]. Studying cell size changes under sublethal dosages of different antibiotics, the principles of cell size control have been discovered and explained using the theory of proteome allocation [5, 24, 25]. A similar set of antibiotic experiments were done to investigate the interplay between cell size and fatty acid synthesis [26]. Chloramphenicol growth experiments were also used to discover the response of cell curvature in C. crescentus as a mechanical feedback mechanism for antibiotic adaptation [20]. Moreover, using cell-wall targeting antibiotics, Harris and Theriot explained the regulation of surface-to-volume ratio of bacterial cells as a result of differential resource allocation to the cell envelope and the cytoplasm [4, 27].

In this mini-review, we discuss recent advances in characterizing bacterial morphological response to different types of antibiotics, focusing on cellular morphological change and its relationship with growth physiology and the underlying cellular composition. Despite decades of studies reporting various morphological changes induced by antibiotics [16] and antibiotic mechanisms of action [28–30], there is no systematic review yet connecting cell morphology to the physiological changes induced by antibiotics. Here we address how cell morphological changes are related to the inhibition of different cellular targets, and whether cell shape parameters can serve as metrics for the antibacterial mechanism of action. We also provide perspectives on how the morphological changes could contribute to antibiotic tolerance and resistance, suggesting mechanisms that could drive the molecular and genetic adaptation to drug treatments.

Morphological determinants of antibiotic action

Antibiotics are commonly classified by their mechanisms of action. Here we consider the physiological effects of four major classes of antibiotics based on their cellular targets: 1) antibiotics that target bacterial DNA, either directly (e.g. mitomycin C) or DNA gyrase (e.g. ciprofloxacin) to inhibit cell division, 2) antibiotics that target ribosomes to inhibit protein synthesis and thus cell growth, 3) antibiotics that target the cell wall by inhibiting peptidoglycan precursor synthesis and penicillin-binding proteins, and 4) antibiotics that directly bind to the cell membrane (inner and/or outer for gram-negative bacteria) to induce membrane damage or inhibit lipid synthesis. A schematic illustrating these actions is shown in Fig 1A. Within each main class, the specific physiological effects and intracellular targets may vary from drug to drug. Nevertheless, regardless of the mechanism of action, antibiotic application leads to distinct morphological changes in bacteria [4, 5, 12]. It is possible to identify different classes of antibiotic action from these morphological changes alone [12, 17]. These changes are likely a consequence of the direct physiological effects of the applied antibiotic, in combination with the cell’s adaptive response to counter the antibiotic action [31].

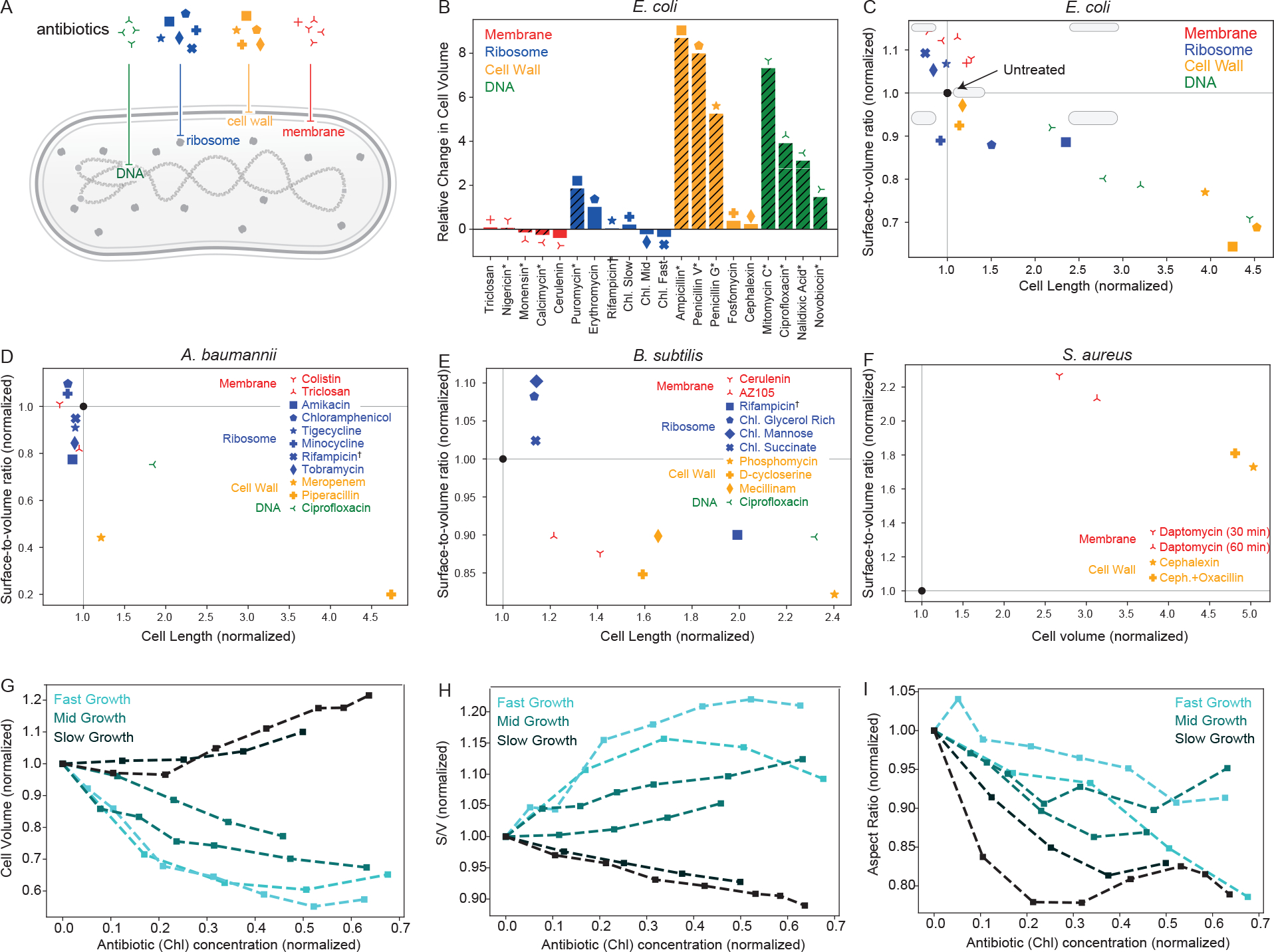

Figure 1. Effects of antibiotics on bacterial cell morphology, classified by their action.

(A) A schematic of a rodlike bacterial cell that illustrates four different cellular targets of antibiotic action: membrane, ribosomes, cell wall, DNA. We assume a spherocylindrical geometry for all cells addressed in this figure, with the exception of (F), where we consider an ellipsoidal shape. (B) Changes in E. coli cell volume after antibiotic application, normalized by the initial volume. Data presented are taken from refs [4, 5, 12] and additional data can be found in references [15, 17, 18, 32]. We indicate concentrations above MIC [12] with hashes on the bars and an asterisk next to the antibiotic name. The remaining data accounts for concentrations below MIC [5]. Here we group rifampicin with ribosome-targeting drugs since its action on RNA polymerase directly inhibits global protein synthesis (same for D and E). (C) Effects of antibiotics on Gram-negative E. coli cell shape, characterized by cell length (x-axis) and surface-to-volume ratio (y-axis). We normalize cell lengths and surface-to-volume ratios for each antibiotic by their initial values and provide simple cell shape schematics in each quadrant of the morpho-space in comparison to the shape of the untreated cell (black solid circle). Panel (B) is to be used as a legend to match markers to antibiotic names. (D-F) Effects of antibiotics on different organisms (D: Gram-negative A. baumannii [17], E: Gram-positive B. subtilis [15, 18, 33], and F: Gram-positive S. aureus [34, 35]). (G-I) Dependence of different cell morphology metrics (G: volume, H: surface-to-volume ratio, I: aspect ratio) on the concentration of the ribosome-targeting antibiotic chloramphenicol. We normalize antibiotic concentration by the half-maximal inhibitory concentration IC50, as defined in Eq. (1), along with volume, surface-to-volume ratio, and aspect ratio by their initial values. We include two representative trajectories each for fast, medium, and slow growing E. coli cells in different nutrient environments.

In Fig. 1B, we present data [5, 12] for cell volume changes in the bacterium E. coli under the action of a variety of antibiotics, with concentrations above or below MIC. The strains considered all lack O-antigen, a load bearing element in the outer membrane of the cell [36]. With the exception of membrane-targeting antibiotics, the application of most drugs leads to an increase in cell size, in part due to impediments of the cell division process. Membrane-targeting antibiotics, on the other hand, induce a reduction in cell surface area and volume due to inhibition of membrane synthesis. Changes to cell volume of a rod-shaped bacterium could arise from changes in cell length, width, or a combination of both. Cell width is is also inversely related to the surface-to-volume ratio of a cell. The ratio of cell length to cell width, or the aspect ratio, can be interpreted as a metric for cell roundedness. Cells with a higher surface-to-volume ratio tend to be more elongated, while those with a lower surface-to-volume tend to be wider. Surface-to-volume ratio is also a fitness metric that determines both the intake of nutrients and the antibiotic itself [4, 8, 24, 27, 31]. It is therefore a critical component of bacterial morphological response and adaptation.

In addition to changes in cell volume, experimental data show that antibiotics induce a wide variety of cell shape changes, in particular changes in cell surface-to-volume ratio and aspect ratio. The scatterplot in Fig. 1C indicates how different antibiotics affect both the cell length and the surface-to-volume ratio. While DNA and cell-wall targeting antibiotics usually lead to an increase in cell length and a reduction in surface-to-volume ratio, membrane-targeting antibiotics lead to an increase in surface-to-volume ratio [12]. Ribosome-targeting antibiotics, on the other hand, induce a more complex variety of shape changes, leading to an increase or decrease in surface-to-volume ratio depending on the growth conditions [5]. In general, cells that become larger upon antibiotic treatment reduce their surface-to-volume ratio and vice versa.

While E. coli is one of the most commonly studied model organisms in laboratory experiments, morphological response of other clinically-relevant bacteria have also been examined. In Fig. 1D–F, we present similar morpho-spaces collected for gram-negative A. baumannii [17] along with Gram-positive B. subtilis [15, 18, 33] and S. aureus [34, 35]. Studied organisms not presented here include C. crescentus [4, 20] and L. monocytogenes [4]. A. baumannii and B. subtilis exhibit similar morphological responses as E. coli, with the exception of membrane-targeting antibiotics, where the surface-to-volume ratio is decreased instead of increased. In the two drugs examined for A. baumannii, we either observe a small increase or a decrease in . For B. subtilis, the decrease in is accompanied by a length increase as seen with cell-wall and DNA-targeting drugs in gram-negative bacteria. For S. aureus, we see an increase in both surface-to-volume ratio and cell volume under the action of cell-wall and membrane-targeting drugs, as cells morph towards a more ellipsoidal shape rather than remaining spherical.

Cell size and shape changes are antibiotic concentration-dependent

The effect of antibiotic is often characterized as a binary process, with concentrations above MIC sufficient to inhibit bacterial growth, or a concentration above MBC sufficient to kill cells [37]. This is often the case in practical antibiotic applications, such as in clinical settings, but an examination of sub-MIC or sub-MBC concentrations can provide greater insight into the underlying physiological processes. As a representative case, we consider the commonly used ribosome-targeting antibiotic chloramphenicol acting on E. coli at various sub-MIC concentrations (Fig. 1G–I) [5]. The morphological changes in the cell, characterized by changes in cell volume (Fig. 1G), surface-to-volume ratio (Fig. 1H), and aspect ratio (Fig. 1I), are gradual functions of antibiotic concentration until MIC is reached. Even when cells are capable of adaptation and survival, their morphology is either affected by the direct action of the antibiotic or via an adaptive physiological response to growth inhibition. These gradual morphological changes are in contrast to the drastic shape changes that occur above MIC (Fig. 1B–C).

In addition to alterations in cell morphology, the presence of sub-lethal antibiotic concentrations gradually inhibits the cell growth rate . For chloramphenicol, growth inhibition can be modeled as [38]

| (1) |

where denotes the growth rate of the untreated cell, is the antibiotic concentration, and is the half-maximal inhibitory concentration. Interestingly, the morphological effects of antibiotic application are not determined solely by the drug concentration; the growth environment plays a critical role by regulating . Examining the shape changes in Fig. 1D–F as a function of the growth rate, we observe that there are distinct morphological responses to growth inhibition in different nutrient environments. In particular, in nutrient-poor environments, cell volume increases while surface-to-volume ratio decreases as a function of drug concentration (Fig. 1G–I). By contrast, in nutrient-rich environments, cell volume decreases while surface-to-volume ratio increases with increasing drug concentration (Fig. 1G–I). Aspect ratio, on the other hand, decreases in all nutrient environments (Fig. 1I), suggesting that ribosome-targeting antibiotics promote cell rounding by reducing cell length relative to width. These nutrient-specific cell size and shape changes have been explained as a relative tradeoff between maximizing nutrient influx and reducing antibiotic influx [24]. Below we discuss how cell size and shape changes arise from physiological response of the bacterial cell to antibiotic treatments.

Cellular physiological state determines morphological response to antibiotics

To understand how antibiotic-induced physiological response drives cell shape changes, we utilize a quantitative model for bacterial cell growth and shape regulation based on recent studies (Fig. 2A) [4, 5, 10, 24, 39–41]. In this model, the volume of a bacterial cell grows exponentially at a rate [42]

| (2) |

As the cell grows, it produces division proteins at a rate proportional to cell volume [24, 40, 41, 43–45]:

| (3) |

where is the abundance of division proteins, and is the volume-specific rate of division protein synthesis. Cell divides when a threshold amount of division proteins, , is accumulated in each cell cycle. This ensures that the cell divides upon adding a constant volume in each cell cycle , which is consistent with the adder model of cell size regulation [39–41, 43, 46]. Average volume of the cell is thus given by [24], where we defined effective division rate . Both the rates and can be modulated by antibiotics, depending on the specific targets of antibiotic action (see below).

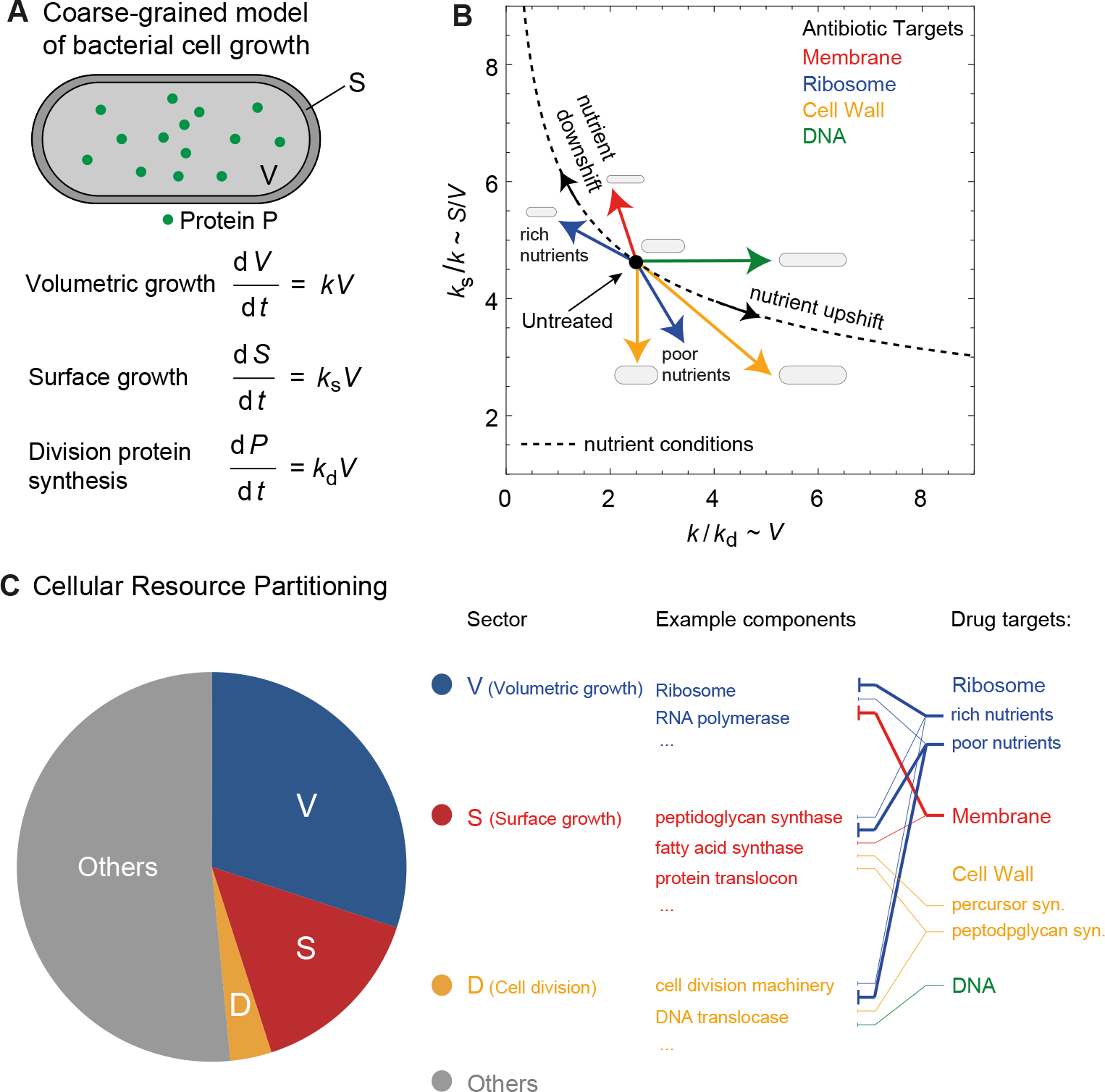

Figure 2. Antibiotics control cell morphology by modulating physiological parameters for cell growth, surface synthesis and protein production.

(A) A coarse-grained model of bacterial cell physiology describing exponential volume growth (at rate ), surface area synthesis (at rate ) and division protein synthesis (at rate ). (B) Effect of antibiotics on the physiological rate constants and that regulate cell shape and growth. The plot shows the dependence of (∝ surface-to-volume ratio) on (∝ cell volume) with or without antibiotic treatment. In the absence of antibiotics, the rate constants are related by the equation of state: (solid line). Antibiotics modulate one or more of these rate constants depending on its cellular target (colored arrows), resulting in cell shape changes and deviations from the equation of state. The yellow arrow pointing downward represents antibiotics that cause cell rounding, e.g., fosfomycin, while the one pointing toward bottom right represents antibiotics that cause both cell rounding and filamentation, e.g., ampillicin (also see Table I). (C) Cellular resource partitioning under antibiotic stress. The schematic shows the proteome mass of a bacterial divided into four coarse-grained sectors based on proteomics abundance data [47] partitioning by functional groups [48]: 1) Sector V containing proteins that regulate (21%–41% of the total proteome mass), 2) Sector S containing proteins that control (12%–14%), 3) Sector D containing division proteins that regulate (<0.5%), and 4) Sector ‘Others’ containing all other proteins. Note that proteins in the sectors V, S and D have little overlap with each other. Thicker solid lines connecting drug targets and sectors represent stronger inhibitory effect, and thinner solid lines represent weaker inhibitory effect.

To describe the control of cell shape, we use a recent model proposed by Harris and Theriot [4] that describes the growth of surface area of the cell at a rate proportional to cell volume

| (4) |

Here, is the volume-specific rate of surface area synthesis. Eq. (2) and (4) leads to the relation that at steady-state. Furthermore, surface area and volume of rod-shaped bacteria are related by the scaling relation: , where the parameters and are organism-specific [10, 49]. For instance, E. coli cells obey the shape law , which is a consequence of maintaining a homeostatic aspect ratio in different nutrient environments [9, 10]. As a result, we have the following equation of state connecting the state variables and [25] (Fig. 2B):

| (5) |

While the above relation holds at steady-state or under nutrient perturbations, the physiological state of the cell deviates from Eq. (5) under antibiotic stress (Fig. 2B). Depending on the cellular target, antibiotics can inhibit one or more of the rate parameters and , leading to changes in cell size and shape, as discussed below and summarized in Table I thereafter for ease of reference.

Table I.

Effects of antibiotics on cell physiological parameters

| Antibiotic Target | Growth rate | Surface synthesis rate | Division rate |

| Membrane | decreases (more) | decreases (less) | unchanged |

| DNA | unchanged | unchanged | decreases |

| Cell wall (PBP1, PBP2) | unchanged | decreases | unchanged |

| Cell wall (PBP3, MurA) | unchanged | decreases | decreases |

| Ribosomes (rich nutrients) | decreases (more) | decreases (less) | decreases (less) |

| Ribosomes (poor nutrients) | decreases (less) | decreases (more) | decreases (more) |

Connections between mechanisms of antibiotic action and cell morphological changes

Morphological changes induced by antibiotics are often dependent on the antibiotic mechanisms of action that target specific physiological properties of the cell. When cells are treated with DNA-targeting antibiotics, SOS response is often triggered [50]. This leads to inhibition of cell division, resulting in filamentous cells [12, 30]. Within the framework of the mathematical model for bacterial growth physiology (Fig. 2B), this morphological response can be captured via a reduction in , while and remain unchanged (Fig. 2B). As a result, cell length increases while cell width remains constant. Considering a spherocylindrical geometry for a rod-shaped bacterial cell, an increase in cell length at constant width will lead to a lower surface-to-volume ratio [4], consistent with experimental data (Fig. 1C).

Membrane-targeting antibiotics induce membrane damage or inhibit membrane synthesis [51, 52], depending on the mechanism of action. Inhibition of membrane synthesis will not only affect surface synthesis rate , but will also lower the overall growth rate of the bacterial cell [26]. Given that membrane-targeting antibiotics ubiquitously increase cell surface-to-volume ratio in E. coli cells (Fig. 1C), and , this implies that is reduced to a lesser extent than (Fig. 2B). This is consistent with the known action of membrane-targeting drugs such as cerulenin, calcimycin and monensin that reduce the rate of bacterial growth [26, 53–55]. In contrast to E. coli, B. subtilis cells lower surface-to-volume ratio in response to membrane-targeting antibiotics (Fig. 1E), which can be interpreted as decreasing to a larger extent than growth rate .

Cell-wall targeting antibiotics can be grouped based on their mechanism of peptidoglycan synthesis inhibition [28]. In E. coli, -lactam antibiotics that inhibit penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) 1A and 1B (e.g. penicillin, cefsulodin), lead to spheroplast formation characterized by large spherical cells [21, 56]. Within the -lactam class, antibiotics that target PBP2 (e.g. mecillinam) or PBP3 (e.g. cephalexin) inhibit cell wall synthesis; in particular, septal cell wall synthesis which is an essential process in cell division [57]. PBP2 inhibition results in cell rounding [56, 58] while PBP3 inhibition leads to long filamentous cells [11]. The latter can result from a reduction in while cell rounding can be caused by a lower . Cell rounding is also observed in rod-shaped bacteria upon MreB depletion [59] or treatment with the MreB inhibitor A22 [60]. However, MreB mutant cells conserved their surface-to-volume ratio [61], suggesting that both the surface area synthesis rate and the growth rate are reduced by similar amounts. Outside the -lactam class, Fosfomycin inhibits peptidoglycan synthesis by inhibiting the peptidoglycan precursor enzyme MurA, leading to longer and wider cells with a lower surface-to-volume ratio (Fig. 1C) [4]. Since fosfomycin treatment does not affect bacterial growth rate [4], increase in cell width can be understood as resulting from a decrease in surface synthesis rate , which depends on the availability of peptidoglycan precursors that fosfomycin inhibits. On the other hand, increase in cell length results from delayed division, indicating that is lowered. Ampicillin, which broadly targets all PBPs, result in filamentous cells with a lower surface-to-volume ratio (Fig. 1C). Ampicillin treated cells thus reduce both and .

For ribosome-targeting antibiotics, experimental data show that cell length and the surface-to-volume ratio increases or decreases depending on the nutrient environment [5]. In particular, decreases ( increases) for chloramphenicol treated cells in nutrient-poor medium, whereas increases ( decreases) in nutrient-rich medium (Fig. 1C–E). Serbanescu et al [25] explained these results using the framework of proteome allocation theory. Upon treatment with chloramphenicol cells up-regulate ribosome synthesis to compensate for ribosome inhibition by chloramphenicol [3]. The excess ribosomes are allocated to growth, division or surface synthesizing proteins depending on nutrient availability. In nutrient-rich medium, cells allocate more ribosomes to division and surface synthesizing proteins than growth, resulting in smaller cells and higher . By contrast, in nutrient-poor medium, cells tend to allocate more ribosomes to growth than division and surface synthesizing proteins, resulting in larger cells and smaller . Thus, in nutrient-rich medium decreases more than and , whereas in nutrient-poor medium and decreases more compared to reduction in (Table I).

Cellular resource allocation strategies for shape changes under antibiotic stress

The growth rate and cell morphology are tightly linked to the macromolecular composition of a cell, and their changes are a consequence of the reallocation of cellular resources in different conditions. Knowing how the macromolecular composition of a cell is remodeled under antibiotic treatment could help us better characterize the landscape of the physiological adaption to drugs. Recent progresses in quantitative proteomics [47, 48] and bioinformatics of protein function and localization [62–64] allowed us to map cellular components as antibiotic targets onto different proteome sectors based on their cellular functions (Fig. 2C). The total proteome mass from [47] can be partitioned into four coarse-grained sectors based on different biosynthetic processes [48], each of which contains proteins that are responsible for volumetric growth (thus controlling ), surface synthesis (thus controlling ), cell division (thus controlling ), and other cellular functions, respectively (pie chart in Fig. 2C). Specifically, in the sector V for the volumetric growth, most proteins are part of the biosynthetic machinery such as the ribosomes and RNA polymerases. In the sector S for cell surface synthesis, many proteins that are part of peptidoglycan synthase, fatty acid synthase, and protein translocation and secretion machinery. Proteins in sector D comprise the cell division machinery and coordinate chromosome segregation and cell division.

Antibiotics altering one or multiple of the state variables , and can thus be reexamined based on how they could resize or inactivate each of the proteome sectors (Fig. 2C). For example, ribosome-targeting antibiotics inhibit translation by blocking actively translating ribosomes, thereby disrupting the V sector. As an adaptive response, cells make more ribosomes thereby increasing the ribosomal protein sector [3]. Since ribosome-targeting antibiotics globally inhibit translation, proteins in the D and S sectors are also affected, resulting in reduced rate of surface synthesis and division protein production. As a different example, the membrane-targeting antibiotic cerulenin mainly increases the surface-to-volume ratio (Fig. 1C), which can be attributed to its role in inhibiting fatty acid synthesis (targeting b-ketoacyl-ACP synthase I FabB in E. coli), thus disrupting the S sector and reducing . In addition, cerulenin treatment could lead to a stronger inhibition of protein synthesis via the stringent response pathway, which in turn affects the V sector and reduces to a larger extent than [26]. To better reconstruct the whole map between antibiotics treatment and cellular composition, we are looking forward to more systematic quantifications of the bacterial proteome under antibiotic stress, e.g., mass spectrometry of cells under steady-state growth with sub-lethal dosages of antibiotics.

Conclusion

Morphological changes induced by antibiotics may serve as indicators of the antibacterial mechanism of action. Antibiotics that inhibit cell division by targeting DNA or septal cell-wall synthesis induce filamentation, characterized by an increase in cell length and volume. Filamentation is thus uniquely indicative of impaired cell division. Cell-wall targeting antibiotics that inhibit PBP1-driven peptidoglycan synthesis, induce spheroplast formation, characterized by larger spherical shapes due to the loss of peptidoglycan layer. Membrane-targeting antibiotics, on the other hand, induce species-dependant effects, e.g. the increase the surface-to-volume ratio of E. coli and S. aureus contrasted with the decrease in the surface-to-volume ratio of A. baumannii and B. subtilis. Ribosome-targeting antibiotics induce a wide variety of shape changes depending on the nutrient environment. Shape changes thus do not uniquely reflect the effect of translation inhibition. Since ribosome-targeting antibiotics directly reduce growth rate by inhibiting the translation rate thus biomass accumulation, impaired growth rate is the primary physiological marker for the action of ribosome-targeting antibiotics below MIC.

Cell size and shapes are determined by cellular physiological state that can be characterized by the rate of cell growth, surface area synthesis and the rate of division protein synthesis. While the effect of antibiotic on cell shape can be understood based on modulations of cellular physiological parameters, the resultant shape changes are not always a direct consequence of antibiotic action and may reflect adaptive response. For instance, an increase in surface-to-volume ratio in nutrient-rich medium provides an adaptive benefit by importing more nutrients to counter growth inhibition by the ribosome-targeting antibiotic. By contrast, a reduction in surface-to-volume ratio reduces antibiotic influx, which is more beneficial for cell survival if the nutrient availability is low [65]. Therefore, changes in cell shape, mediated by changes in surface-to-volume ratio, may confer drug tolerance by diluting the concentration of antibiotics or by increasing nutrient intake. Shape-induced drug tolerance could act in synergy with other mechanisms of antibiotic resistance [66], thereby weakening the action of the drug. Cell shape regulators may thus serve as potent targets for preventing antibiotic tolerance and resistance.

Perspectives.

Antibiotics induce distinct cell shape changes in bacteria depending on the cellular target. These shape changes serve as indicators of the mechanisms of antibiotic action.

Cell morphological changes reflect alterations in cellular physiological state which are tightly linked to cellular proteome composit41ion. Changes in proteome composition indicate how the cellular resources are reallocated in different conditions.

Shape changes also reflect adaptive response of the cell to resist antibiotic stress. For example, a lower surface-to-volume would reduce antibiotic influx. Cell shape regulators may thus serve as therapeutic targets to prevent antibiotic tolerance and resistance.

Acknowledgements

We thank Nikola Ojkic for useful discussions.

Funding

SB acknowledges funding from the NIH (R35 GM143042) and the Curci Foundation.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

References

- [1].Silver Lynn L and Bostian KA. Discovery and development of new antibiotics: the problem of antibiotic resistance. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 37(3):377–383, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Andrews Jennifer M. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 48(suppl_1):5–16, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Scott Matthew, Gunderson Carl W, Mateescu Eduard M, Zhang Zhongge, and Hwa Terence. Interdependence of cell growth and gene expression: origins and consequences. Science, 330(6007):1099–1102, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Harris Leigh K and Theriot Julie A. Relative rates of surface and volume synthesis set bacterial cell size. Cell, 165(6):1479–1492, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Si Fangwei, Li Dongyang, Cox Sarah E, Sauls John T, Azizi Omid, Sou Cindy, Schwartz Amy B, Erickstad Michael J, Jun Yonggun, Li Xintian, et al. Invariance of initiation mass and predictability of cell size in escherichia coli. Current Biology, 27(9):1278–1287, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Scott Matthew, Klumpp Stefan, Eduard M Mateescu, and Terence Hwa. Emergence of robust growth laws from optimal regulation of ribosome synthesis. Molecular Systems Biology, 10(8):747, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Schaechter Moselio, Maaløe Ole, and Kjeldgaard Niels O. Dependency on medium and temperature of cell size and chemical composition during balanced growth of salmonella typhimurium. Microbiology, 19(3):592–606, 1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Young Kevin D. The selective value of bacterial shape. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 70(3):660–703, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zaritsky A and Pritchard RH. Changes in cell size and shape associated with changes in the replication time of the chromosome of escherichia coli. Journal of Bacteriology, 114(2):824–837, 1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ojkic Nikola, Serbanescu Diana, and Banerjee Shiladitya. Surface-to-volume scaling and aspect ratio preservation in rod-shaped bacteria. Elife, 8:e47033, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Yao Zhizhong, Kahne Daniel, and Kishony Roy. Distinct single-cell morphological dynamics under beta-lactam antibiotics. Molecular Cell, 48(5):705–712, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nonejuie Poochit, Burkart Michael, Pogliano Kit, and Pogliano Joe. Bacterial cytological profiling rapidly identifies the cellular pathways targeted by antibacterial molecules. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110:201311066, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Billings Gabriel, Ouzounov Nikolay, Ursell Tristan, Desmarais Samantha M, Shaevitz Joshua, Gitai Zemer, and Huang Kerwyn Casey. De novo morphogenesis in l-forms via geometric control of cell growth. Molecular Microbiology, 93(5):883–896, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Monahan Leigh G, Turnbull Lynne, Osvath Sarah R, Birch Debra, Charles Ian G, and Whitchurch Cynthia B. Rapid conversion of pseudomonas aeruginosa to a spherical cell morphotype facilitates tolerance to carbapenems and penicillins but increases susceptibility to antimicrobial peptides. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 58(4):1956–1962, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Vadia Stephen and Levin Petra Anne. Growth rate and cell size: a re-examination of the growth law. Current opinion in microbiology, 24:96–103, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cushnie TP, O’Driscoll Noëlle H, and Lamb Andrew J. Morphological and ultrastructural changes in bacterial cells as an indicator of antibacterial mechanism of action. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 73(23):4471–4492, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Htoo Htut Htut, Brumage Lauren, Chaikeeratisak Vorrapon, Tsunemoto Hannah, Sugie Joseph, Tribuddharat Chanwit, Pogliano Joe, and Nonejuie Poochit. Bacterial cytological profiling as a tool to study mechanisms of action of antibiotics that are active against acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 63(4), 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sauls John T, Cox Sarah E, Do Quynh, Castillo Victoria, Ghulam-Jelani Zulfar, and Jun Suckjoon. Control of bacillus subtilis replication initiation during physiological transitions and perturbations. Mbio, 10(6), 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Mickiewicz Katarzyna M, Kawai Yoshikazu, Drage Lauren, Gomes Margarida C, Davison Frances, Pickard Robert, Hall Judith, Mostowy Serge, Aldridge Phillip D, and Errington Jeff. Possible role of l-form switching in recurrent urinary tract infection. Nature communications, 10(1):1–9, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Banerjee Shiladitya, Lo Klevin, Ojkic Nikola, Stephens Roisin, Norbert F Scherer, and Aaron R Dinner. Mechanical feedback promotes bacterial adaptation to antibiotics. Nature Physics, 17(3):403–409, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Klainer AS and Russell RRB. Effect of the inhibition of protein synthesis on the escherichia coli cell envelope. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 6(2):216–224, 1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Diver JM and Wise R. Morphological and biochemical changes in escherichia coli after exposure to ciprofloxacin. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 18(Supplement_D):31–41, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Elliott TSJ, Shelton A, and Greenwood D. The response of escherichia coli to ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin. Journal of Medical Microbiology, 23(1):83–88, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Serbanescu Diana, Ojkic Nikola, and Banerjee Shiladitya. Nutrient-dependent trade-offs between ribosomes and division protein synthesis control bacterial cell size and growth. Cell Reports, 32(12):108183, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Serbanescu Diana, Ojkic Nikola, and Banerjee Shiladitya. Cellular resource allocation strategies for cell size and shape control in bacteria. The FEBS Journal, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Vadia Stephen, Jessica L Tse, Lucena Rafael, Yang Zhizhou, Kellogg Douglas R, Wang Jue D, and Levin Petra Anne. Fatty acid availability sets cell envelope capacity and dictates microbial cell size. Current Biology, 27(12):1757–1767, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Harris Leigh K and Theriot Julie A. Surface area to volume ratio: A natural variable for bacterial morphogenesis. Trends in Microbiology, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Spratt Brian G. Distinct penicillin binding proteins involved in the division, elongation, and shape of escherichia coli k12. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 72(8):2999–3003, 1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Poehlsgaard Jacob and Douthwaite Stephen. The bacterial ribosome as a target for antibiotics. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 3(11):870–881, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ojkic Nikola, Lilja Elin, Direito Susana, Dawson Angela, Allen Rosalind J, and Waclaw Bartlomiej. A roadblock-and-kill mechanism of action model for the dna-targeting antibiotic ciprofloxacin. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 64(9):e02487–19, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ojkic Nikola, Serbanescu Diana, and Banerjee Shiladitya. Antibiotic resistance via bacterial cell shape-shifting. mBio, 13:e00659–22, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Basan Markus, Zhu Manlu, Dai Xiongfeng, Warren Mya, Daniel Sévin Yi-Ping Wang, and Hwa Terence. Inflating bacterial cells by increased protein synthesis. Molecular Systems Biology, 11(10):836, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lamsa Anne, Lopez-Garrido Javier, Quach Diana, Riley Eammon P Joe Pogliano, and Pogliano Kit. Rapid inhibition profiling in bacillus subtilis to identify the mechanism of action of new antimicrobials. ACS chemical biology, 11(8):2222–2231, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Halladin DK R Rojas E.. F Koslover E.. K Lee T.. C Huang K.. Zhou X. and Theriot JA Mechanical crack propagation drives millisecond daughter cell separation in Staphylococcus aureus. Science, 348(6234):574–578, 2015. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Quach DT, Sakoulas G, Nizet V, Pogliano J, and Pogliano K. Bacterial cytological profiling (bcp) as a rapid and accurate antimicrobial susceptibility testing method for staphylococcus aureus. EBioMedicine, 4:95–103, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Enrique R Rojas Gabriel Billings, Pascal D Odermatt, George K Auer, Lillian Zhu, Amanda Miguel, Fred Chang, Douglas B Weibel, Julie A Theriot, and Kerwyn Casey Huang. The outer membrane is an essential load-bearing element in gram-negative bacteria. Nature, 559(7715):617–621, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Wallace MacFarlane T and Samaranayake Lakshman P.. Chapter 13 - use of the microbiology laboratory. In Wallace MacFarlane T and Samaranayake Lakshman P., editors, Clinical Oral Microbiology, pages 187–203. Butterworth-Heinemann, 1989. ISBN 978–0-7236–0934-6. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-7236-0934-6.50018-5. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780723609346500185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Greulich Philip, Scott Matthew, Evans Martin R, and Allen Rosalind J. Growth-dependent bacterial susceptibility to ribosome-targeting antibiotics. Molecular systems biology, 11(3):796, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Taheri-Araghi Sattar, Bradde Serena, Sauls John T, Hill Norbert S, Levin Petra Anne, Paulsson Johan, Vergassola Massimo, and Jun Suckjoon. Cell-size control and homeostasis in bacteria. Current Biology, 25(3):385–391, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ghusinga Khem Raj, Vargas-Garcia Cesar A, and Singh Abhyudai. A mechanistic stochastic framework for regulating bacterial cell division. Scientific Reports, 6:30229, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Si Fangwei, Treut Guillaume Le, Sauls John T, Vadia Stephen, Levin Petra Anne, and Jun Suckjoon. Mechanistic origin of cell-size control and homeostasis in bacteria. Current Biology, 29(11):1760–1770, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Wang Ping, Robert Lydia, Pelletier James, Dang Wei Lien, Taddei Francois, Wright Andrew, and Jun Suckjoon. Robust growth of escherichia coli. Current Biology, 20(12):1099–1103, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Deforet Maxime, van Ditmarsch Dave, and Xavier Joao B. Cell-size homeostasis and the incremental rule in a bacterial pathogen. Biophysical Journal, 109(3):521–528, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bertaux François, Von Kügelgen Julius, Marguerat Samuel, and Shahrezaei Vahid. A bacterial size law revealed by a coarse-grained model of cell physiology. PLoS Computational Biology, 16(9):e1008245, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Panlilio Mia, Grilli Jacopo, Tallarico Giorgio, Iuliani Ilaria, Sclavi Bianca, Cicuta Pietro, and Marco Cosentino Lagomarsino. Threshold accumulation of a constitutive protein explains e. coli cell-division behavior in nutrient upshifts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(18), 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Amir Ariel. Cell size regulation in bacteria. Physical Review Letters, 112(20):208102, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Li Gene-Wei, Burkhardt David, Gross Carol, and Weissman Jonathan S.. Quantifying Absolute Protein Synthesis Rates Reveals Principles Underlying Allocation of Cellular Resources. Cell, 157(3):624–635, 2014. ISSN 0092–8674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Schmidt Alexander, Kochanowski Karl, Vedelaar Silke, Erik Ahrné Benjamin Volkmer, Callipo Luciano, Knoops Kèvin, Bauer Manuel, Aebersold Ruedi, and Heinemann Matthias. The quantitative and condition-dependent Escherichia coli proteome. Nature Biotechnology, 34(1):104–110, 2016. ISSN 1087–0156. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Ojkic Nikola and Banerjee Shiladitya. Bacterial cell shape control by nutrient-dependent synthesis of cell division inhibitors. Biophysical Journal, 120(11):2079–2084, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Beaber John W, Hochhut Bianca, and Waldor Matthew K. Sos response promotes horizontal dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes. Nature, 427(6969):72–74, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Hurdle Julian G, O’neill Alex J, Chopra Ian, and Lee Richard E. Targeting bacterial membrane function: an underexploited mechanism for treating persistent infections. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 9(1):62–75, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Epand Richard M, Walker Chelsea, Epand Raquel F, and Magarvey Nathan A. Molecular mechanisms of membrane targeting antibiotics. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes, 1858(5):980–987, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Omura Satoshi. The antibiotic cerulenin, a novel tool for biochemistry as an inhibitor of fatty acid synthesis. Bacteriological Reviews, 40(3):681–697, 1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Russell James B. A proposed mechanism of monensin action in inhibiting ruminant bacterial growth: Effects on ion flux and protonmotive force. Journal of Animal Science, 64(5):1519–1525, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Raatschen Nadja, Wenzel Michaela, Leichert Lars Ingo Ole, Düchting Petra, Krämer Ute, and Bandow Julia Elisabeth. Extracting iron and manganese from bacteria with ionophores—a mechanism against competitors characterized by increased potency in environments low in micronutrients. Proteomics, 13(8):1358–1370, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Spratt Brian G and Pardee Arthur B. Penicillin-binding proteins and cell shape in e. coli. Nature, 254(5500):516–517, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Chung Hak Suk, Yao Zhizhong, Goehring Nathan W, Kishony Roy, Beckwith Jon, and Kahne Daniel. Rapid -lactam-induced lysis requires successful assembly of the cell division machinery. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(51):21872–21877, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Jackson Jesse J and Kropp Helmut. Differences in mode of action of (-lactam antibiotics influence morphology, lps release and in vivo antibiotic efficacy. Journal of Endotoxin Research, 3(3):201–218, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Kruse Thomas, Jette Bork-Jensen, and Kenn Gerdes. The morphogenetic mrebcd proteins of escherichia coli form an essential membrane-bound complex. Molecular Microbiology, 55(1):78–89, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Gitai Zemer, Dye Natalie Anne, Reisenauer Ann, Wachi Masaaki, and Shapiro Lucy. Mreb actin-mediated segregation of a specific region of a bacterial chromosome. Cell, 120(3):329–341, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Harris Leigh K, Dye Natalie A, and Theriot Julie A. Ac aulobacter mreb mutant with irregular cell shape exhibits compensatory widening to maintain a preferred surface area to volume ratio. Molecular Microbiology, 94(5):988–1005, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Galperin Michael Y., Makarova Kira S., Wolf Yuri I., and Koonin Eugene V.. Expanded microbial genome coverage and improved protein family annotation in the COG database. Nucleic Acids Research, 43(Database issue):D261–D269, 2015. ISSN 0305–1048. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Orfanoudaki Georgia and Economou Anastassios. Proteome-wide subcellular topologies of E. coli polypeptides database (STEPdb). Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP, 13(12):3674–87, 2014. ISSN 1535–9476. doi: 10.1074/mcp.o114.041137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Loos Maria S, Ramakrishnan Reshmi, Vranken Wim, Tsirigotaki Alexandra, Tsare Evrydiki-Pandora, Zorzini Valentina, De Geyter Jozefien, Yuan Biao, Tsamardinos Ioannis, Klappa Maria, Schymkowitz Joost, Rousseau Frederic, Karamanou Spyridoula, and Economou Anastassios. Structural Basis of the Subcellular Topology Landscape of Escherichia coli. Frontiers in Microbiology, 10:1670, 2019. ISSN 1664–302X. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Serbanescu Diana Ojkic Nikola and Banerjee Shiladitya. Antibiotic resistance via bacterial cell shape-shifting. mBio, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Blair Jessica, Webber Mark A, Baylay Alison J, Ogbolu David O, and Piddock Laura JV. Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 13(1):42–51, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]