Abstract

Behavioral health care has been slow to take up robust efforts to improve patient safety. This lag is especially apparent in inpatient psychiatry, where there is risk for physical and psychological harm. Recent investigative journalism has provoked public concern about instances of alleged abuse, negligence, understaffing, sexual assault, inappropriate medication use, patient self-harm, poor sanitation, and inappropriate restraint and seclusion. However, empirical evidence describing the scope of unsafe experiences is limited. While evidence-based inpatient psychiatry requires care to be trauma-informed, market failures and a lack of payment alignment with patient-centered care leave patients vulnerable to harm. Existing regulatory mechanisms attempt to provide accountability; however, these mechanisms are imperfect. Furthermore, research is sparse. Few health services researchers study inpatient psychiatry, the issue has not been a priority among research funders, and data on inpatient psychiatry is excluded from national surveys of quality. Several policy levers could begin to address these deficiencies. These include aligning incentives with patient-centered care, building trauma-informed care into accreditation and monitoring, conducting trend analyses of critical incidents, and improving research capacity.

Since the landmark Institute of Medicine (IOM) reports To Err Is Human1 and Crossing the Quality Chasm2 were published, there have been robust local and national initiatives to improve the safety and quality of health care. However, behavioral health care has been slow to take up similar efforts, despite the IOM’s publication of another report in 2006, Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions.3 This lag is especially apparent in inpatient psychiatry, where patients can face risk for physical and psychological harm.

News reports have called attention to patient harm in inpatient psychiatric settings, including issues of abuse, negligence, understaffing, sexual assault, inappropriate medication use, patient self-harm, poor sanitation, and inappropriate restraint and seclusion.4–6 Empirical evidence suggests that adverse events, including medication errors and toxicity, are frequent.7,8 A 2018 study of fourteen general hospital psychiatric units identified an adverse event in 14.5 percent of hospitalizations, and the odds of experiencing an adverse event increased with age and length-of-stay.9 Qualitative analyses indicate that patients may experience psychological harm during their stay.10,11

News reports combined with limited empirical evidence are enough to prompt a call to action. This article first defines patient safety and gives a brief overview of the organizational context of inpatient psychiatric facilities. Next, it highlights relevant features of the inpatient psychiatric care market, regulation and monitoring, and research capacity. It concludes with policy recommendations to support organizations in maintaining safe environments of care.

Quality And Patient Safety

The role of inpatient psychiatry in achieving clinical and social outcomes (for example, symptom reduction and engagement with community care) lacks consensus, which makes it hard to completely define quality.12 However, experiences of unsafe care could have cascading consequences on a person’s health and engagement with the health care system.13 At a minimum, inpatient psychiatry should not harm.

Threats to safety in this setting include treatment error (a deviation from a standard of care that is routinely practiced) but also arise from the general omission of evidence-based models of care or even commission of abuse. Types of harms include physical (for example, assaults and the use of restraint), treatment (such as overmedication and the neglect of physical health), and psychological (for example, traumatization and distrust). Indeed, psychological safety for patients is a more salient concern in this context than in other hospital settings, and it can be compromised by experiences of physical harm as well as those of depersonalization, humiliation, or feeling threatened.11

The Organizational Context

Several processes must be in place to ensure safety within inpatient psychiatric facilities. Safe environments require that staff members be proactive and intervene quickly in tense or escalating situations. Their ability to notice and mindfully intervene at these flash-point moments can result in the reduced use of containment measures (that is, chemical and physical restraint and closed-door seclusion) that in some instances can be harmful to patients.14 The adoption of trauma-informed care, a treatment framework that recognizes and addresses the effects of all types of trauma, has been associated with significant reductions in restraint and seclusion.10,15 Providing care that is psychologically safe requires that patients feel safe, have a sense of control over their lives, and have a sense of connection to staff members who are perceived to be available and who see their needs as legitimate16—a process dependent on staff engagement.17

To create such a milieu, staff members need to have a shared understanding of how patients should be treated. This shared understanding depends on the organizational culture, which sets the unit’s tone and defines critical elements of treatment. Organizational leaders delineate policies and ensure that the working conditions and environment support staff members’ efforts.18 The process of creating an organizational culture that embraces patient-centeredness, such as trauma-informed care, requires detailed attention to the role of leadership and staff involvement.19 Recognition of staff stress and attention to the quality of the work environment are critical to maintaining an environment that is supportive of both staff and patient safety.20,21

Numerous qualitative studies provide evidence of the strenuous reality of inpatient work.22 Such work places staff members in a precarious safety position that only intensifies if they perceive that they lack the necessary support to do their work. Nurses understand that engagement with patients is critical to safety but also recognize the realities of their role that pull them in many directions.17 The likelihood that organizations will appropriately support frontline staff and engage in robust efforts to prevent psychological and physical harm is dependent, in part, on systems-level factors.

Features Of The Inpatient Psychiatric Care Market

MARKET FAILURES

Inpatient psychiatric care is characterized by market failures similar to those in the restof health care, but arguably to a greater extent. First, providers hold the majority of information about the quality and safety of patient care, and constraints on family involvement compound this. For example, patients generally meet visitors outside of the treatment environment as opposed to having loved ones “at the bedside.” Therefore, families might have a hard time observing the treatment environment and advocating for patients. Second, patient choice is limited. Psychiatric patients do not always choose hospitalization (that is, some are admitted involuntarily) or where they receive care (limited by available beds). Third, health plans, state Medicaid agencies, and the legal system often act as agents on behalf of patients. These entities could have interests that are misaligned with those of the patient and might not be considering the safety of care in their decisions. Finally, patients may struggle with self-advocacy during and after hospitalization because of their mental health condition, power imbalances between the patient and provider, and stigma that can lead to patients’ voices being discredited.

The asymmetric information, lack of choice, and challenges with family and self-advocacy contribute to a market for inpatient psychiatric care that leaves patients vulnerable. Thus, the underlying mission and motivation of inpatient psychiatric providers and organizations, along with the extrinsic incentives they face, will be especially important in shaping the quality and safety of care. These incentives are captured, in part, in the form of ownership and payment differences among facilities.

OWNERSHIP

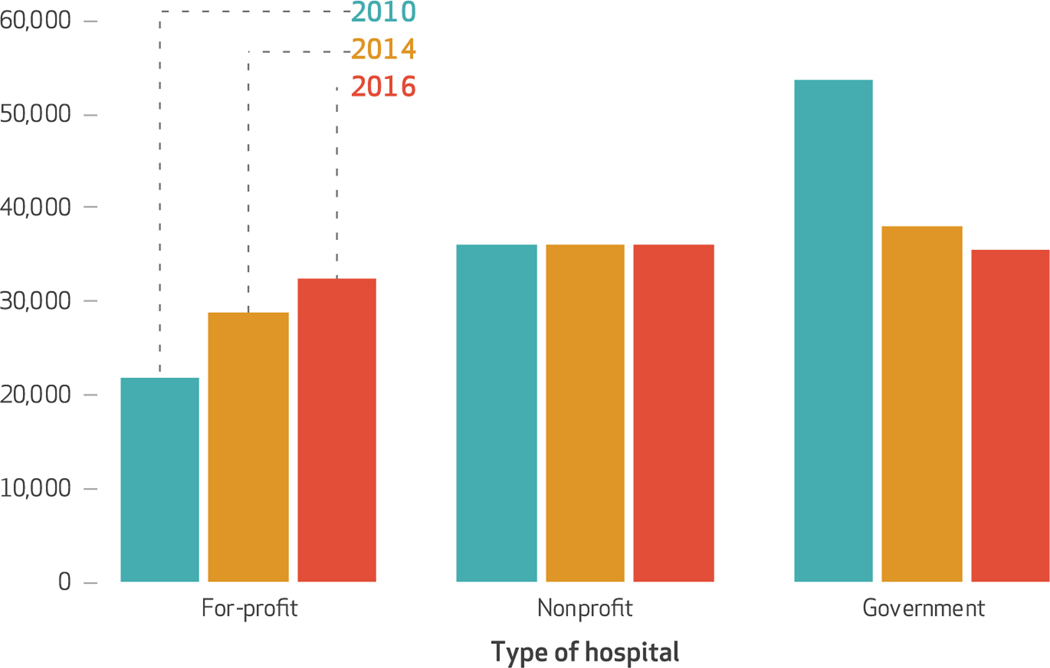

Tracking the influence of ownership in patient safety is critical because the number of for-profit beds increased by 48 percent from 2010 to 2016 (exhibit 1). This increase may be due to the Affordable Care Act’s insurance expansion and behavioral health care coverage requirements. Relatedly, a recent clarification in regulations surrounding Medicaid managed care organizations has relaxed the institution for mental disease exclusion that previously prohibited Medicaid payments for care received in a mental health facility with sixteen or more beds: Payment is now allowed for up to fifteen days a month.23 Further, states are increasingly providing care in institutions for mental disease using section 1115 waivers (which allow a state to request permission to use Medicaid funds in ways that are not otherwise allowed under federal rules). As of June 2018, twelve states had approved waivers, and thirteen had pending waivers for care at institutions for mental disease.24 The majority of these waivers focus on substance use treatment, though some states are seeking waivers for mental health care. Medicaid is the largest payer of behavioral health care, and for-profit facilities are a large share of institutions for mental disease. Therefore, for-profits stand to benefit from these policy changes and may see opportunities for continued growth.

EXHIBIT 1. Numbers of inpatient psychiatric beds, by type of hospital, 2010, 2014, and 2016.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the National Mental Health Services Survey of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. NOTES Bed counts are exact for 2010 but estimated for 2014 and 2016. The survey’s categorical bed count ranges for 2014 and 2016. We totaled the bed counts for both the low and high ends of the categorical ranges and used their average for the estimates here.

The expansion in for-profit facilities is concerning because for-profits are hypothesized to exploit market failures to maximize profits.25 Evidence-based care may be less of a priority among for-profit facilities, especially if providing it would absorb profit and resources and there is no considerable risk if they fail to provide it (for example, no loss in patients or reimbursement rates). Organizations engaged in trying to reduce costs might employ fewer or less qualified staff members, be less accommodating of diverse patient needs (for example, use shared rooms despite individual patients’ needs), or not invest in modern information technology and a therapeutic milieu. If organizations systematically limit spending without regard to patients’ needs, patient safety may be at risk.

Indeed, the largest supplier of psychiatric beds in the country, Universal Health Services, has seen numerous facilities come under local and federal investigation for issues related to abuse, neglect, and fraud while maintaining a profit margin of over 20 percent for psychiatric services.26

Of course, nonprofits could engage in similar behaviors. While there is evidence of nonprofits behaving this way in the general health care literature, research on inpatient psychiatry suggests that quality is poorer at for-profit psychiatric facilities relative to nonprofits—for example, for-profits have more safety violations.27,28 However, research into this disparity for inpatient psychiatric care is more limited than research in other settings. For example, research on nursing homes (which share characteristics with inpatient psychiatric facilities) has consistently demonstrated that for-profits allocate fewer resources toward patient safety, relative to non-profits.29–31 It is possible, however, that nursing homes are more likely than inpatient psychiatric facilities to have a smaller disparity between for-profits and nonprofits because the nursing home market has more accountability mechanisms. Quality information is available through platforms such as Nursing Home Compare. Also, there are more opportunities for nursing home residents to choose facilities, transfer away from poor-quality facilities, and use family members for monitoring and advocacy.30

PAYMENT

In addition to ownership type, low reimbursement and misaligned payment models could hinder organizations’ ability to deliver safe care.

Inpatient psychiatric care is commonly considered to be underpaid, though profit margins likely depend on facility type, market concentration, and payer mix. Private freestanding psychiatric facilities without an emergency department may be able to maximize revenue by selecting patients they anticipate will have more generous insurance coverage and lower resource use. Some freestanding for-profit facilities maintain profit margins of over 20 percent, and the extent to which these profits arise from selection, minimum outlays, or higher reimbursement rates is unclear. Research to describe such variation is underdeveloped, likely due to an absence of adequate data.

Medicaid and private insurance vary in their reimbursement rates and structures and often look to Medicare as an anchor for setting rates. Medicare, which covers approximately one-fourth of psychiatric admissions, uses the inpatient psychiatric facility prospective payment system (IPF PPS) to reimburse for inpatient psychiatric care. Under this system, care is paid for on a per diem basis. The first day of care generates the highest payment and includes an additional payment for treatment in the hospital’s emergency department, with adjustments for patient and facility characteristics. Similar to other prospective payment systems, the IPF PPS incentivizes facilities to constrain resources, which may threaten patient safety—especially if appropriate incentives around quality performance are not used.

In 2014 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) implemented the Inpatient Psychiatric Facility Quality Reporting Program, a pay-for-reporting program designed to address information asymmetry. Under the program, facilities participating in the IPF PPS are incentivized to publicly report on a suite of measures for the entire patient population (both Medicare and other payers) or face a 2 percent reduction in Medicare reimbursements.

While the goal of public reporting is sound, there are several limitations of the reporting program, including the fact that Medicare does not audit facilities, the lack of patient-level data and characteristics, the failure to integrate information into Hospital Compare, and the information’s unclear meaning or utility to consumers. Additionally, most of the measures (for example, screening for substance use) are only marginally related to patient safety and may be susceptible to gaming. Therefore, the reporting program could have unintended consequences. Patient safety could suffer as a result of facilities’ shifting effort toward performing and reporting on measures—an issue observed among nursing homes.32,33 Also, publicly reported performance could provide a false sense of assurance if facilities demonstrate high performance on what is being formally measured but deliver unsafe care.25,34 Indeed, preliminary work looking at this phenomenon revealed that in Massachusetts, where there were disparities on the CMS screening measures by ownership, for-profits generally performed better than nonprofits; however, for-profits had higher rates of complaints and substantiated complaints.35 Nevertheless, the reporting program takes a meaningful first step toward aligning incentives.

Lack of data is a barrier to rigorous systems-level research on patient safety within inpatient psychiatry.

Regulation And Monitoring

ACCREDITATION

The Joint Commission accredits the majority of inpatient psychiatric facilities (83.1 percent, according to 2016 data from the National Mental Health Services Survey data). The Joint Commission’s patient-safety standards for inpatient psychiatry focus on restraint and seclusion processes, suicide screening, access to ligature points, and translation services. As is the case with other hospital care, its Sentinel Event Policy requires facilities to have processes in place to internally investigate adverse events and encourages voluntary reporting of events. Beyond the Joint Commission’s efforts regarding suicide screening, the built environment, and restraint or seclusion, we did not find language in its standards about the provision of trauma-informed care or safety culture. The Joint Commission’s quality monitoring program generally does not go beyond CMS’s quality metrics and does not employ expectations for achieving benchmarks of performance.36

Similarly, the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), which accredits health plans, does not have robust patient-safety standards regarding inpatient psychiatry. Furthermore, NCQA measures do not focus on inpatient psychiatric care but rather on transitions to community treatment or general health care for people with serious mental illness.

STATE LICENSING

Facilities must comply with state-specific licensing rules. Exhibit 2 demonstrates variation in regulatory language across a sample of six geographically disparate states chosen to show variation in policies but not considered representative of the US. Some states do not extend regulations beyond the standards of the Joint Commission and CMS and patients’ federal rights (for example, the right to have visitors). States typically require the reporting of complaints related to critical incidents (such as abuse, neglect, and unexpected death). However, among the six sampled states, we found limited information describing states’ trend analyses of critical incidents, which suggests that states do not systematically track and publicly report aggregated rates of complaints. States varied in their policies regarding reporting processes and the elements required in reporting (for example, patient demographics) that could influence the utility of such analyses. Furthermore, states differ in their transparency with critical incidents and regulatory violations. For example, Colorado posts inspection reports and critical incidents that come through its mandated reporting system to an online portal, while Massachusetts requires the public to fill out public records requests that can be expensive, time-consuming to procure, and sometimes delivered in voluminous redacted pages rather than an accessible database (Misael Garcia, paralegal, Massachusetts Department of Mental Health, personal communication, July 5, 2017, August 16, 2018, and September 18, 2018). Moreover, the extent to which reported and substantiated incidents accurately reflect true events depends on the ease of reporting and state entities’ capacity to comprehensively investigate and substantiate complaints.

EXHIBIT 2.

Differences in regulatory language regarding inpatient psychiatry across a sample of six states

| Regulatory language refers to: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| State | Staff-patient ratios | Trauma-informed care | Internal trending of adverse events | Involvement of peers | Access to outdoors |

| CA | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| CO | No | No | No | No | No |

| FL | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| MA | Yesa | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| MS | No | No | No | No | No |

| NV | No | No | No | No | No |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of information from public documents related to state licensing requirements for inpatient psychiatric facilities.

Currently there are no explicit staff-patient ratios in Massachusetts, but the regulations state that facilities must apply appropriate staff-patient ratios; the definition of appropriate is not provided in the regulations.

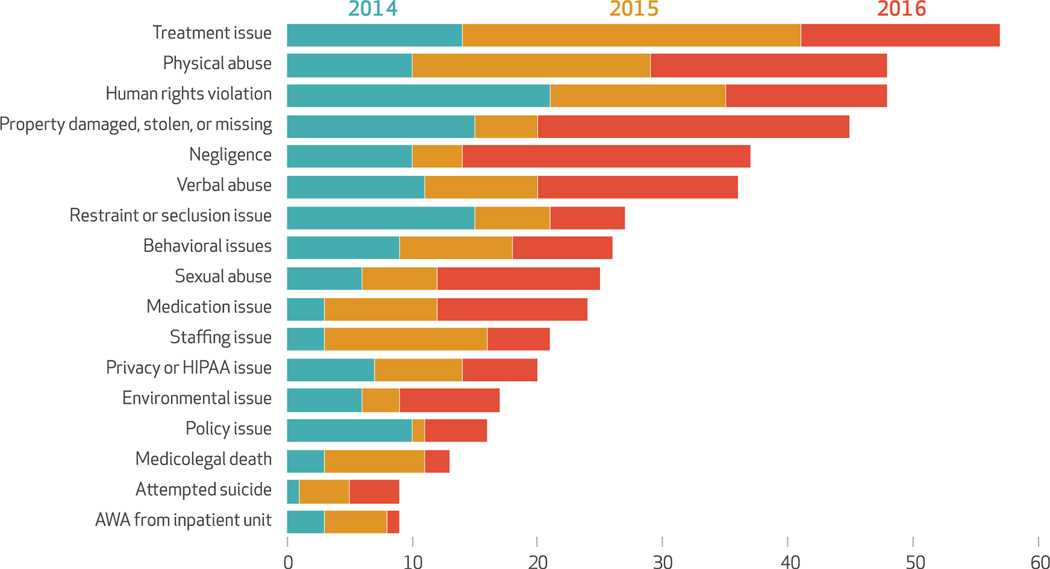

Even within a state, there could be variation in the propensity to externally report critical incidents by providers, patients, and families regardless of mandated reporting requirements. Any analysis of state-level critical-incident data should therefore be interpreted with caution, but such analyses can nevertheless play a role in early-detection systems and comparative research. For examples of partly and fully substantiated complaints in Massachusetts, see exhibit 3.

EXHIBIT 3. Number of different types of complaints that were partly or fully substantiated from state-operated and -licensed inpatient psychiatric facilities in Massachusetts.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the Massachusetts Department of Mental health in a file received through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request in July 2017. NOTES This exhibit includes only incidents that were substantiated at the time of the FOIA request. The types are not mutually exclusive, as some complaints had multiple types and incidents. Complaints of human rights violations include any complaint related to violations of the Patient’s Bill of Rights. Mental Health Legal Advisors Committee, Basic rights at inpatient mental health facilities in Massachusetts [Internet]. Boston (MA): The Committee; 2015 Mar [cited 2018 Oct 11]. Available from: http://www.mhlac.org/Docs/basic_rights_at_inpatient_mental_health_facilities.pdf. The rights include both federal and state rights. HIPAA is Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. AWA is absent without authorization.

FEDERAL PROGRAM

The Protection and Advocacy for Individuals with Mental Illness Program, administered by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAHMSA), is a federally funded entity charged with advocating for people with mental illness and redressing any violation of their rights, with a historical focus on institutional settings. Congress created the program in 1986 in recognition of the fact that patients within psychiatric facilities are vulnerable to abuse and that states vary in their critical-incident monitoring system capacity (see online appendix exhibit 1 for congressional findings).37

Because of its federal funding, the program is independent from states and has the flexibility to investigate and provide support in the interest of patients. It has the authority to access facilities and patients’ records and therefore has substantial utility in ensuring patient safety. In fiscal year 2014 the program served 13,936 clients, addressing issues such as inappropriate restraint and seclusion, excessive medication, sexual assault, and lack of discharge planning, and it investigated 993 deaths.38 A 2018 Government Accountability Office evaluation of the program among a sample of eight states revealed that 74 percent of reported cases of abuse, neglect, and rights violations in fiscal year 2016 were decided in the client’s favor.39 However, the program’s ability to fulfill its mandate is limited by funding amounts.40

Research Capacity

Health services research related to inpatient psychiatry in general and safety in particular is sparse. The lack of research could be due to a lack of interest in the topic among health services researchers or the limited systematic data available and the low priority given to the topic by major research funders.41

For illustrative purposes, in early 2018 we searched the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s patient-safety portal (for all years) and Google Scholar (for 2013–18) for articles related to safety within inpatient psychiatry. In the portal, twenty-one peer-reviewed journal articles and six case reports were identified. This is compared to, for example, 1,467 journal articles and 423 case reports related to safety in nursing homes. The nonsystematic Google Scholar search suggested that of the limited research available, most is published in nursing and psychiatry journals by authors outside of the United States and focuses primarily on issues of physical safety. The results of this search corroborate other descriptions of the literature.41

FUNDING

A similar search of the National Institutes of Health’s Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (RePORTER) database of funded research (for 2005–17) identified eleven projects tangentially related to patient safety within inpatient psychiatry. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute funded two projects, one of which was for the development of staff and patient experience measures;42 and the other of which was on postdischarge transitions.

DATA

Lack of data is also a barrier to rigorous systems-level research on patient safety within inpatient psychiatry. The Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems database (commonly used to examine patients’ experiences of care) excludes psychiatric patients. While the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project database (commonly used to examine hospital utilization) includes information related to psychiatric patients within general hospitals, it excludes freestanding psychiatric facilities. SAMHSA’s National Mental Health Services Survey does not provide precise estimates of bed counts or identify provider organizations, so these data cannot be linked year to year, to quality measures of CMS or the Joint Commission, or to critical incidents. Further, there is no clearinghouse responsible for systematically collecting critical incidents across facilities, states, and accountability entities. Moreover, even smaller-scale studies are challenging given the limited uptake of electronic health records (EHRs) among psychiatric facilities. Freestanding psychiatric facilities were excluded from CMS’s EHR incentive program,43 and in 2015 only 15 percent of such facilities used a basic EHR system.44

Inpatient psychiatric care has been left on the sidelines of efforts to measure and improve patient safety, despite glaring need.

Given the current research infrastructure, it is impossible to rigorously quantify and fully describe iatrogenic outcomes across psychiatric facilities, let alone test the impact of systems-level changes or facility characteristics on the safety of the care provided.

Policy Recommendations

Considering the features of the market, vulnerability of patients, rise of for-profit ownership, status of payment, regulatory policy, and research infrastructure surrounding inpatient psychiatry, we suggest ways to systematically support organizations in delivering safe care.

ALIGN PAYMENT INCENTIVES WITH PATIENT-CENTERED CARE

Measurement of the patient experience could be a robust method for capturing more nuanced aspects of patient safety, including psychological safety. Incentivizing performance on measures of patient experience could help motivate an organizational transformation that would support staff-patient relationships and the therapeutic milieu, leading to care that is holistically safer. There is a considerable body of evidence attesting to inpatient psychiatric patients’ ability to evaluate their experiences of care,42 and the Veterans Health Administration has collected patient experience and satisfaction data for over twenty years.

The National Quality Forum has endorsed the Inpatient Consumer Survey as a patient-reported-outcome performance instrument,45 and it could be used in contractual agreements between payers and providers as well as by accrediting bodies. CMS’s reporting program would be an ideal vehicle to compel systematic measurement and reporting. Careful consideration would need to be given to the timing of measurement, appropriateness for risk adjustment, and the methods for doing so (including factors such as perceived coercion, engagement, and expectations), and incentive design.

Critically, once payment incentives were aligned, reimbursement rates would have to be sufficient to support providers’ ability to deliver safe care.

CONDUCT TREND ANALYSES OF CRITICAL INCIDENTS

Facilities should conduct internal monitoring of critical incidents to inform continuous improvement. States should track and report trends in critical-incident and inspection reports to support systems-level root cause analysis and prevention of harm and to help regulators identify provider organizations in need of consultation and intervention.

National-level monitoring is also needed. State agencies, the Protection and Advocacy for Individuals with Mental Illness Program, the Joint Commission, and CMS are all entities that could receive information on critical incidents. The Joint Commission and CMS should require standardized reporting, with SAMHSA serving as a clearinghouse charged with collating and organizing these data. Academic researchers can be incentivized to conduct analyses with the data, although federal involvement through oversight, auditing, and translation of insights is needed. Data on relevant characteristics related to the provider (for example, ownership type and staff-patient ratios) and patient (such as race/ethnicity and gender identity) should be collected within reporting systems and included in analyses.

BUILD TRAUMA-INFORMED CARE INTO ACCREDITATION AND MONITORING

The Joint Commission and the NCQA should broaden their standards for providers and health plans to include standards for trauma-informed care and safety culture. These entities can also strengthen their quality-measurement and reporting programs. Accreditors and the federal government could support transformation efforts by facilitating learning collaboratives, in which facility directors, patients, and families could share challenges and strategies for implementing evidence-based models of care.

IMPROVE RESEARCH CAPACITY

Standardized data collection and reporting are needed at all levels, and the data should include information on quality, safety, utilization, payment, and costs. National surveys of hospital quality and utilization should include inpatient psychiatry. Incentivizing use of EHRs would assist research applications as well as organizational quality improvement, such as tracking care plans and medication use.

Massachusetts is beginning to require freestanding psychiatric facilities to report case-mix data to the state’s all-payer claims database. These data are expected to be released for the first time in 2019 and will be particularly useful in examining the relationships among facility type, payment, and safety. If other states follow this trend, research capacity for learning would improve.

Once the data exist, researchers need viable funding to support the work. Major research funders should make this a priority and encourage the submission of high-quality proposals.

Conclusion

Inpatient psychiatric care has been left on the sidelines of efforts to measure and improve patient safety, despite glaring need. Features of the system and external levers could influence facilities’ capacity and willingness to meaningfully address patient safety across physical and psychological dimensions. It is imperative that payers align their incentives in favor of patient-centered and trauma-informed care; regulators more robustly monitor critical incidents and broaden their standards to include trauma-informed care and safety culture; and data be systematically collected, analyzed, and reported. Patient safety within inpatient psychiatry needs considerable attention and should be the next frontier for health policy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Morgan Shields was supported by a T32 predoctoral training grant (T32AA007567) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The authors thank Deborah Garnick, Dominic Hodgkin, and Sharon Reif of Brandeis University and Meredith Rosenthal of Harvard University for their helpful feedback and review of earlier drafts. The authors also thank Sara Scully of Brandeis University for her assistance in verifying state regulatory language, as well as Margaret Binzer of the Alliance for Quality and Patient Safety and Jeffrey Brady of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality for their helpful feedback at the Health Affairs review session. An earlier version of the manuscript was presented at a working paper review session in Washington, D.C., April 10, 2018, organized by Health Affairs and supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

Contributor Information

Morgan C. Shields, Institute for Behavioral Health, Heller School for Social Policy and Management, Brandeis University, in Waltham, Massachusetts..

Maureen T. Stewart, Institute for Behavioral Health, Heller School for Social Policy and Management, Brandeis University..

Kathleen R. Delaney, Department of Community, Systems, and Mental Health Nursing, College of Nursing, Rush University, in Chicago, Illinois..

NOTES

- 1.Corrigan JM, Kohn LT, Donaldson MS, editors. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance-use conditions. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shields MC, Reneau H, Albert SM, Siegel L, Trinh N-H. Harms to consumers of inpatient psychiatric facilities in the United States: an analysis of news articles. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2018. May 30. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swenson K Teens tied down and shot up with drugs at Pembroke Pines Facility. Broward Palm Beach New Times [serial on the Internet]. 2014. Feb 20 [cited 2018 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.browardpalmbeach.com/news/teens-tied-down-and-shot-up-with-drugs-at-pembroke-pines-facility-6353447 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kowalczyk L Families trusted this hospital chain to care for their relatives. It systematically failed them. Boston Globe. 2017. Jun 10. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alshehri GH, Keers RN, Ashcroft DM. Frequency and nature of medication errors and adverse drug events in mental health hospitals: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2017; 40(10):871–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grasso BC, Genest R, Jordan CW, Bates DW. Use of chart and record reviews to detect medication errors in a state psychiatric hospital. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(5):677–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vermeulen JM, Doedens P, Cullen SW, van Tricht MJ, Hermann R, Frankel M, et al. Predictors of adverse events and medical errors among adult inpatients of psychiatric units of acute care general hospitals. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(10):1087–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muskett C Trauma-informed care in inpatient mental health settings: a review of the literature. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2014;23(1):51–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frueh BC, Knapp RG, Cusack KJ, Grubaugh AL, Sauvageot JA, Cousins VC, et al. Patients’ reports of traumatic or harmful experiences within the psychiatric setting. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(9):1123–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iezzoni LI, editor. Risk adjustment for measuring health care outcomes. 4th ed. Chicago (IL): Health Administration Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith CP. First, do no harm: institutional betrayal and trust in health care organizations. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017;10:133–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowers L, Alexander J, Bilgin H, Botha M, Dack C, James K, et al. Safewards: the empirical basis of the model and a critical appraisal. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2014; 21(4):354–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beckett P, Holmes D, Phipps M, Patton D, Molloy L. Trauma-informed care and practice: practice improvement strategies in an inpatient mental health ward. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2017; 55(10):34–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berg SH, Rørtveit K, Aase K. Suicidal patients’ experiences regarding their safety during psychiatric in-patient care: a systematic review of qualitative studies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Polacek MJ, Allen DE, Damin-Moss RS, Schwartz AJA, Sharp D, Shattell M, et al. Engagement as an element of safe inpatient psychiatric environments. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2015;21(3):181–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanerva A, Lammintakanen J, Kivinen T. Patient safety in psychiatric inpatient care: a literature review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2013;20(6):541–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bryson SA, Gauvin E, Jamieson A, Rathgeber M, Faulkner-Gibson L, Bell S, et al. What are effective strategies for implementing trauma-informed care in youth inpatient psychiatric and residential treatment settings? A realist systematic review. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2017;11(1):36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kristensen S, Christensen KB, Jaquet A, Møller Beck C, Sabroe S, Bartels P, et al. Strengthening leadership as a catalyst for enhanced patient safety culture: a repeated cross-sectional experimental study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(5):e010180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, Tsipa A, O’Connor DB. Healthcare staff well-being, burnout, and patient safety: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016; 11(7):e0159015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delaney KR, Shattell M, Johnson ME. Capturing the interpersonal process of psychiatric nurses: a model for engagement. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2017;31(6):634–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paradise J, Musumeci M. CMS’s final rule on Medicaid managed care: a summary of major provisions [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; [updated 2016 Jun 9; cited 2018 Oct 15]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/cmss-final-rule-on-medicaid-managed-care-a-summary-of-major-provisions/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.Musumeci M Key questions about Medicaid payment for services in “institutions for mental disease” [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; [updated 2018. Jun 18; cited 2018 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/key-questions-about-medicaid-payment-for-services-in-institutions-for-mental-disease/ [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansmann HB. The role of nonprofit enterprise. Yale Law J. 1980;89(5): 835–901. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Universal Health Services. 2016 annual report [Internet]. King of Prussia (PA): UHS; [cited 2018 Oct 12]. Available from: https://uhsinc.gcs-web.com/static-files/8733fb1d-8812-4a45-815a-d6bfed5a8fd7 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenau PV, Linder SH. A comparison of the performance of for-profit and nonprofit U.S. psychiatric inpatient care providers since 1980. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(2):183–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mark TL. Psychiatric hospital ownership and performance: do nonprofit organizations offer advantages in markets characterized by asymmetric information? J Hum Resour. 1996;31(3):631–49. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amirkhanyan AA, Kim HJ, Lambright KT. Does the public sector outperform the nonprofit and for-profit sectors? Evidence from a national panel study on nursing home quality and access. J Policy Anal Manage. 2008;27(2):326–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chou SY. Asymmetric information, ownership, and quality of care: an empirical analysis of nursing homes. J Health Econ. 2002;21(2):293–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Comondore VR, Devereaux PJ, Zhou Q, Stone SB, Busse JW, Ravindran NC, et al. Quality of care in for-profit and not-for-profit nursing homes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu SF. Multitasking, information disclosure, and product quality: evidence from nursing homes. J Econ Manage Strategy. 2012;21(3):673–705. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Konetzka RT, Brauner DJ, Shega J, Werner RM. The effects of public reporting on physical restraints and antipsychotic use in nursing home residents with severe cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014; 62(3):454–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holmstrom B, Milgrom P. Multitask principal-agent analyses: incentive contracts, asset ownership, and job design. J Law Econ Organ. 1991; 7(special issue):24–52. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shields M Quality of inpatient psychiatric care: the relationship among CMS’ quality measures, complaints, and ownership. Poster presentation at: Academy Health Annual Research Meeting; 2018 Jun 24; Seattle, WA. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shields MC, Rosenthal MB. Quality of inpatient psychiatric care at VA, other government, nonprofit, and for-profit hospitals: a comparison. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(3):225–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 38.National Disability Rights Network. Protection and Advocacy for Individuals with Mental Illness Program (PAIMI) [Internet]. Washington (DC); NDRN; 2015. Feb [cited 2018 Oct 12]. Available from: http://www.ndrn.org/images/PAIMI/Information_on_PAIMI_February_2015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 39.Government Accountability Office. Mental health: federal procedures to oversee protection and advocacy programs could be further improved [Internet]. Washington (DC): GAO; 2018. May [cited 2018 Oct 12]. (Report No. GAO-18–450). Available from: https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/692003.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 40.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Evaluation of the Protection and Advocacy for Individuals with Mental Illness (PAIMI) Program, phase III: final report [Internet]. Rockville (MD):SAMHSA; 2011. [cited 2018 Oct 12]. (Report No. PEP12-EVALPAIMI). Available from: https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/PEP12-EVALPAIMI/PEP12-EVALPAIMI.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 41.D’Lima D, Crawford MJ, Darzi A, Archer S. Patient safety and quality of care in mental health: a world of its own? BJPsych Bull. 2017;41(5): 241–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Delaney KR, Johnson ME, Fogg L. Development and testing of the combined assessment of psychiatric environments: a patient-centered quality measure for inpatient psychiatric treatment. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2015;21(2):134–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolf L, Harvell J, Jha AK. Hospitals ineligible for federal meaningful-use incentives have dismally low rates of adoption of electronic health rec- ords. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012; 31(3):505–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Busch AB, Bates DW, Rauch SL. Improving adoption of EHRs in psychiatric care. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(18):1665–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ortiz G, Schacht L. Psychometric e valuation of an inpatient consumer survey measuring satisfaction with psychiatric care. Patient. 2012;5(3): 163–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.