Abstract

Each year, hundreds of millions of people are infected with arboviruses such as dengue, yellow fever, chikungunya, and Zika, which are all primarily spread by the notorious mosquito Aedes aegypti. Traditional control measures have proven insufficient, necessitating innovations. In response, here we generate a next generation CRISPR-based precision-guided sterile insect technique (pgSIT) for Aedes aegypti that disrupts genes essential for sex determination and fertility, producing predominantly sterile males that can be deployed at any life stage. Using mathematical models and empirical testing, we demonstrate that released pgSIT males can effectively compete with, suppress, and eliminate caged mosquito populations. This versatile species-specific platform has the potential for field deployment to control wild populations, safely curtailing disease transmission.

Keywords: pgSIT, Aedes aegypti, CRISPR, dengue, arboviruses, vector control, population elimination

Introduction

The mosquito Aedes aegypti is the principal vector of several deadly viruses, including dengue, yellow fever, chikungunya, and Zika. Unfortunately, its geographic spread has been exacerbated by climate change, global trade, and its preference for anthropogenic habitats, such that 3.9 billion people are presently at risk1. Traditionally, mosquito control has been achieved through insecticides, though developing resistances have rendered them less effective. Moreover, insecticides are harmful to non-target species, such as insect pollinators, and direct exposure can be dangerous for humans and pets 2–5. Alternative integrated approaches for mosquito control include preventative measures designed to reduce mosquito populations through habitat reduction or larval predation, though these can also be impractical or introduce invasive species. Notwithstanding, the continuous expansion of this invasive mosquito species demonstrates that current measures are insufficient.

Alternative genetic biological approaches have been developed to control specific species, including the sterile insect technique (SIT) and the Wolbachia-mediated incompatible insect technique (WIIT)6,7. Here, radiation-sterilized males (♂’s), or ♂’s harboring Wolbachia, are repeatedly mass released to mate with wild females (♀’s) which typically mate only once, thereby reducing mosquito populations over time. However, high capital and operational costs limit the broad application of SIT and WIIT for mosquito control, with major challenges including the efficient removal of ♀ mosquitoes and cost-effective deployment of only ♂’s8. An alternative genetic approach, ♀-specific release of insects carrying a dominant lethal gene (fsRIDL), can genetically sex-sort ♀’s, and can be released as eggs. However, fsRIDL relies on the broad-spectrum antibiotic tetracycline for mass-rearing, affecting the fitness and competitiveness of released ♂’s9. Additionally, fsRIDL ♂’s are fertile and pass fsRIDL to wildtype (WT) ♂ progeny, so the transgene will linger in the environment, which may not be ideal.

Suggested as a potent, yet controversial, possible alternative population control approach, gene drives leverage the CRISPR based precise DNA cutting and repair to spread into populations. Two types of gene drives have been engineered: the spread of suppression drives collapses a population, whereas modification drives spread cargo genes that can potentially block the chain of transmission of a targeted disease10–14. However, gene drives come with safety concerns and debilitating technical challenges that can limit their efficacy, including errors in DNA repair and the natural selection of viable repair mistakes that are resistant to the gene drive (i.e. resistant alleles). To address some of the challenges with gene drives, precision-guided SIT (pgSIT) also leverages CRISPR to instead produce sterile males that should not be affected by resistant alleles. pgSIT works by simultaneously disrupting genes essential for ♀ viability and ♂ fertility during development to genetically generate sex-sorted and viable sterilized ♂’s 15,16. Notably, pgSIT avoids many of the gene-drive safety concerns by separating the CRISPR components into binary strains—one expressing Cas9 and the other expressing multiple gRNA—that, when genetically crossed, produce pgSIT progeny ready for release. Previously, we showed that disrupting a ♀-specific flight muscle gene (fem-myo) induced a flightless ♀-specific phenotype in Ae. aegypti ♀’s17. However, this approach would still result in viable flightless transgenic ♀’s being released which may be less desirable than removing females altogether.

To further improve and build upon the system, we instead cause ♀ lethality, simplifying the process of generating pgSIT ♂’s for release. Our herein-developed next-generation pgSIT approach simultaneously disrupts three genes in Ae. aegypti— doublessex (dsx), intersex (ix), and β-Tubulin 85D (βTub)—to induce ♀ lethality, or ♀ masculinization, and near-complete ♂ sterility. We demonstrate that pgSIT ♂’s are competitive and multiple releases can suppress cage populations. Notably, mathematical modeling indicates that this technology can control insect populations effectively over a wide range of realistic performance parameters and fitness costs. Overall, this next-generation pgSIT approach provides a viable option for the release of sterile males, bringing the field significantly closer to deployable CRISPR-based vector control strategies. Additionally, we also develop a rapid diagnostic assay to detect pgSIT transgene presence that could be used alongside field tests. Taken together, we have demonstrated that pgSIT could be designed to target essential sex determination and fertility genes in Ae. aegypti to produce sterilized males that can suppress and eliminate caged populations thereby providing an alternate system for controlling this deadly vector.

Results

Disrupting sex-determination and fertility.

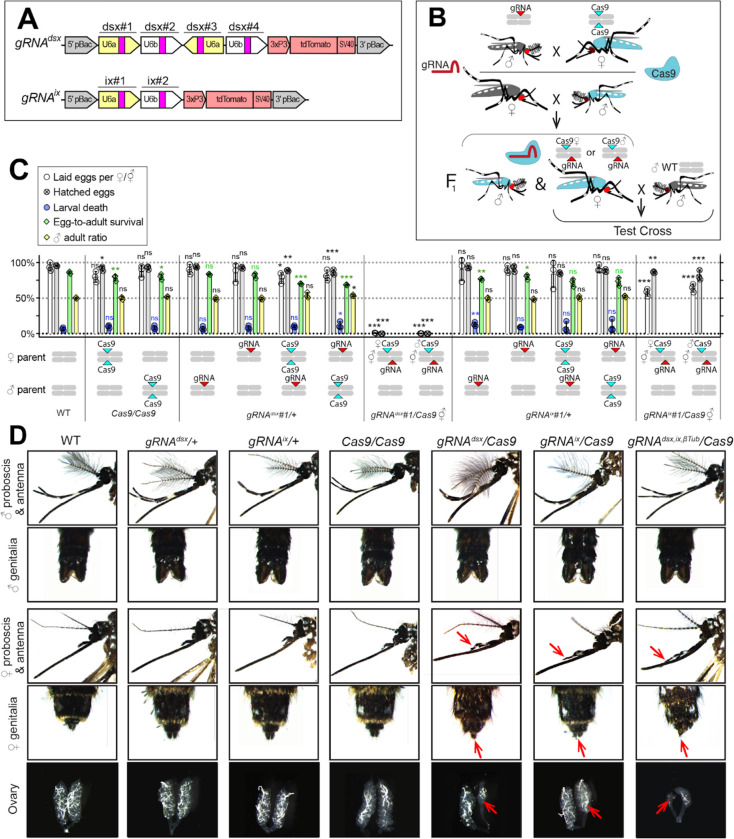

To induce ♀-specific lethality and/or masculinization in Ae. aegypti, we targeted either the dsx (AAEL009114) or ix (AAEL010217) genes, both of which are associated with sex determination and differentiation in insects 18–24. The dsx gene is located on chromosome 1R and is alternatively spliced to produce two ♀-specific (dsxF1 and dsxF2) and one ♂-specific (dsxM) isoforms18. Exon 5b is retained in both ♀-specific dsxF1 and dsxF2 transcripts and is spliced out in the ♂-specific dsxM transcript. Therefore, to disrupt both ♀-specific dsx isoforms, we selected four gRNAs that target exon 5b (Supplementary Table 1) and assembled the pBac gRNAdsx plasmid (Fig. 1A). The ix gene (AAEL010217) is located on chromosome 3L and is orthologous to the ix gene required for ♀-specific sexual differentiation in Drosophila melanogaster24. While the D. melanogaster ix does not undergo sex-specific alternative splicing and is expressed in both sexes, ix interacts with dsxF, but not dsxM, resulting in ♀-specific activity23. To disrupt ix, we engineered a gRNAix cassette harboring two gRNAs targeting ix exon 1 (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Table 1). To determine the effects of targeting these genes, multiple separate gRNAdsx and gRNAix strains were generated and assessed by crossing with Nup50-Cas9 (hereafter, Cas9)17. To explore potential effects of maternal Cas9 carryover, all genetic crosses were conducted reciprocally (Fig. 1B). Remarkably, the disruption of either dsx or ix transformed all trans-hemizygous ♀’s into intersexes (⚥’s), independent of whether Cas9 was inherited from the mother (i.e., ♀Cas9), or father (i.e., ♂Cas9). The induced phenotypes were especially strong in gRNAdsx/+; Cas9/+ ⚥’s, which exhibited multiple malformed morphological features, such as mutant maxillary palps, abnormal genitalia, and malformed ovaries (Fig. 1D, Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 2). Notably, only ~50% of gRNAdsx/+; Cas9/+ ⚥’s were able to blood feed, producing very few hatchable eggs. While a similar fraction of gRNAix/+; Cas9/+ ⚥’s were able to blood feed, the fed ⚥’s laid hatchable eggs (Fig. 1C, Supplementary Table 3). Sanger sequencing confirmed expected mutations at the dsx and ix loci (Supplementary Fig. 2). Importantly, we did not observe abnormal morphological features in either gRNAdsx/+; Cas9/+ ♂’s or gRNAix/+; Cas9/+ ♂’s, as neither their fecundity, ear anatomy, wing beat frequency (WBF), nor ♂ phonotactic behaviors were significantly affected suggesting that disrupting these genes results in ♀-specific consequences (Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 3). Taken together, these findings reveal that ♀-specific lethality and/or masculinization can be efficiently achieved by disrupting either dsx or ix genes and also validate the gRNA target sequences for ♀-specific disruption.

Figure 1. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated disruption of dsx or ix affects female mosquito morphology and fecundity.

A Schematic maps of gRNA genetic constructs. The gRNAdsx and gRNAix constructs harbor a 3xP3-tdTomato marker and multiple gRNAs guiding Cas9 to the female-specific doublesex (dsx) gene or the female-active intersex (ix) gene, respectively. B A schematic of the genetic cross between the homozygous Cas9 and hemizygous gRNAdsx/+ or gRNAix/+ mosquitoes to generate trans-hemizygous F1 females (♀’s). Reciprocal genetic crosses were established and two types of trans-hemizygous F1 ♀’s were generated: gRNA/+; ♀Cas9/+ ♀’s inherited a maternal Cas9; and gRNA/+; ♂Cas9/+ ♀’s inherited a paternal Cas9. Then, both trans-hemizygous ♀’s were crossed to wildtype (WT) males (♂’s), and their fecundity was assessed. C A comparison of the fecundity and male ratio of trans-hemizygous, hemizygous Cas9 or gRNA ♀’s to those of WT ♀’s. The bar plot shows means and one standard deviation (±SD). The data presents one transgenic strain of each construct, gRNAdsx#1 and gRNAix#1, as all strains induced similar results (all data can be found in Supplementary Table 3). D All gRNAdsx#1/+; Cas9/+ and gRNAix#1/+; Cas9/+ trans-hemizygous ♀ mosquitoes exhibited male-specific features (red arrows in D), had reduced fecundity, and were transformed into intersexes (⚥’s). Statistical significance of mean differences was estimated using a two-sided Student’s t test with equal variance (ns: p ≥ 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ****p < 0.001). Source data is provided as a Source Data File.

Multiplexed target gene disruption.

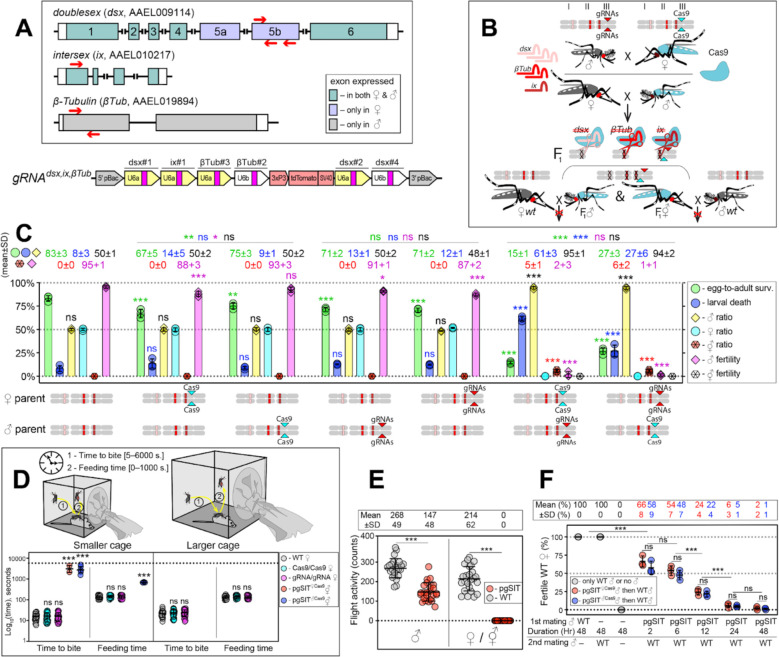

To guide CRISPR-mediated disruption of multiple genes essential for ♀-specific viability and ♂-specific fertility, we engineered the gRNAdsx,ix,βTub construct which combines the effective gRNAs described above. More specifically, this construct harbors six gRNAs: three gRNAs targeting the dsx exon 5b; one gRNA targeting the ix exon 1; and two gRNA targeting the β-Tubulin 85D (βTub, AAEL019894) exon 117 (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Table 1). The βTub gene is specifically expressed in mosquito testes 25–27 and is essential for sperm maturation, elongation, and motility 17,28. Three independent homozygous gRNAdsx,ix,βTub strains were established and reciprocally crossed to the homozygous Cas9 strain to measure survival, fitness, and fertility of generated pgSIT (i.e., trans-hemizygous) progeny (Fig. 2B–C, Supplementary Fig. 4). To determine transgene integration sites, we performed genome sequencing of gRNAdsx,ix,βTub#1/Cas9 (hereafter, gRNAdsx,ix,βTub) and found that this strain harbored a single copy of the transgene inserted on chromosome 3 (Supplementary Fig. 5). Using these sequencing data, we also validated the presence of diverse mutations at the intended target sites (Supplementary Fig. 6). Moreover, RNA sequencing revealed a significant reduction in target gene expression and mutations in the target RNA sequences (Supplementary Figs. 7–10). These findings reveal that single copies of Cas9 and gRNAdsx,ix,βTub can induce mutagenesis at six separate DNA targets simultaneously, thereby providing desired pgSIT phenotypic redundancy for increased resilience.

Figure 2. The pgSIT cross results in nearly complete female lethality and male sterility.

A Schematic maps of targeted genes (box) and gRNAdsx,ix,βTub construct. Red arrows show relative locations of gRNA target sequences (box). gRNAdsx,ix,βTub harbors a 3xP3-tdTomato marker and six gRNAs to guide the simultaneous CRISPR/Cas9-mediated disruption of dsx, ix, and βTub genes. Violet exon boxes 5a and 5b represent ♀-specific exons. B A schematic of the reciprocal genetic cross between the homozygous Cas9, marked with Opie2-CFP, and homozygous gRNAdsx,ix,βTub to generate the trans-hemizygous F1 (aka. pgSIT) progeny. Relative positions of dsx, ix, and βTub target genes (bar color corresponds to gRNA color), and transgene insertions in the Cas9 (Nup50-Cas9 strain17) and gRNAdsx,ix,βTub#1 strains are indicated in the three pairs of Ae. aegypti chromosomes. To assess the fecundity of generated pgSIT mosquitoes, both trans-hemizygous ♀’s and ♂’s were crossed to the WT ♂’s and ♀’s, respectively. C Comparison of the survival, sex ratio, and fertility of trans-hemizygous, hemizygous Cas9 or gRNAdsx,ix,βTub#1, and WT mosquitoes. The bar plot shows means ± SD over triple biological replicates (n = 3, all data in Supplementary Table 4). D Blood feeding assays using both types of trans-hemizygous intersexes (⚥’s): pgSIT♀Cas9 and pgSIT♂Cas9 ⚥’s. To assess blood feeding efficiency, individual mated ♀’s or ⚥’s were allowed to blood feed on an anesthetized mouse inside a smaller (24.5 × 24.5 × 24.5 cm) or larger cage (60 × 60 × 60 cm), and we recorded the time: (i) to initiate blood feeding (i.e., time to bite); and (ii) of blood feeding (i.e., feeding time). The plot shows duration means ± SD over 30 ♀’s or ⚥’s (n = 30) for each genetic background (Supplemental Table 5). E Flight activity of individual mosquitoes was assessed for 24 hours using vertical Drosophila activity monitoring (DAM, Supplemental Table 6). F Mating assays for fertility of offspring produced via crosses between trans-hemizygous ♂’s that inherited a maternal Cas9 (pgSIT♀Cas9) or paternal Cas9 (pgSIT♂Cas9) and WT ♀’s (Supplemental Table 8). The plot shows fertility means ± SD over three biologically independent groups of 50 WT ♀’s (n = 3) for each experimental condition. Statistical significance of mean differences was estimated using a two-sided Student’s t test with equal variance. (ns: p ≥ 0.05ns *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001). Source data is provided as a Source Data File.

pgSIT ♀’s and ⚥’s are incapacitated.

We next tested the simultaneous disruption of dsx, ix, and βTub, by reciprocally crossing gRNAdsx,ix,βTub with Cas9, which resulted in the death of most pgSIT ♀’s and ⚥’s, as no ♀’s and only 5–6% ⚥’s survived to adulthood (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, around 95% of pgSIT ⚥’s failed to eclose, independent of whether Cas9 was inherited from the mother or father (termed pgSIT♀Cas9 or pgSIT♂Cas9 ⚥’s, respectively, Supplementary Table 4). The pgSIT ⚥’s that did eclose had more pronounced abnormal phenotypes than ⚥’s generated from dsx or ix single-gene disruption (Fig. 1D, Supplementary Fig. 1) and were sterile (Fig. 2C, Supplementary Table 4). Moreover the vast majority of adult pgSIT ⚥’s had reduced fitness as they could not blood feed (Fig. 2D, Supplementary Table 5), did not fly as frequently (Fig. 2E, Supplementary Table 6), had smaller abdomens and wings (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 2), and had 4x-reduced longevity (Supplementary Fig. 11A, Supplementary Table 7). Taken together, these results demonstrate that Cas9 in combination with gRNAdsx,ix,βTub induces the lethality or transformation of pgSIT ♀’s into sterile unfit ⚥’s.

pgSIT ♂’s are mostly sterile with normal longevity and mating ability.

We found that ~94% of the eclosed pgSIT mosquitoes were ♂’s due to the majority of the ⚥’s not surviving to adulthood (Fig. 2C, Supplementary Table 4). Both pgSIT♀cas9 and pgSIT♂Cas9 ♂’s were also nearly completely sterile (Fig. 2C, Supplementary Table 4). Surprisingly, due to our assumption that pgSIT♀cas9♂ and pgSIT♂Cas9 ♂ would be roughly equivalent, the pgSIT♀cas9 ♂’s showed less flight activity than WT (Fig. 2E, Supplementary Table 6), and pgSIT♀cas9 ♂’s developmental times were slightly delayed (Supplementary Fig. 11D). Nevertheless, the longevity of pgSIT ♂’s was not significantly different from WT ♂’s (Supplementary Fig. 11B, Supplementary Table 7), and both pgSIT♀cas9♂ and pgSIT♂Cas9 ♂ were competitive and mated with WT ♀’s to effectively suppress the fertility and re-mating ability of WT ♀’s (Fig. 2F, Supplementary Table 8). Taken together, these findings reveal that maternal deposition of Cas9 may induce some fitness costs, however these could be avoided by using a paternal source of Cas9, and despite these observed fitness effects both pgSIT♀cas9♂ and pgSIT♂Cas9 ♂ were competitive and both types could likely be capable of inducing population suppression.

pgSIT ♂’s induce population suppression.

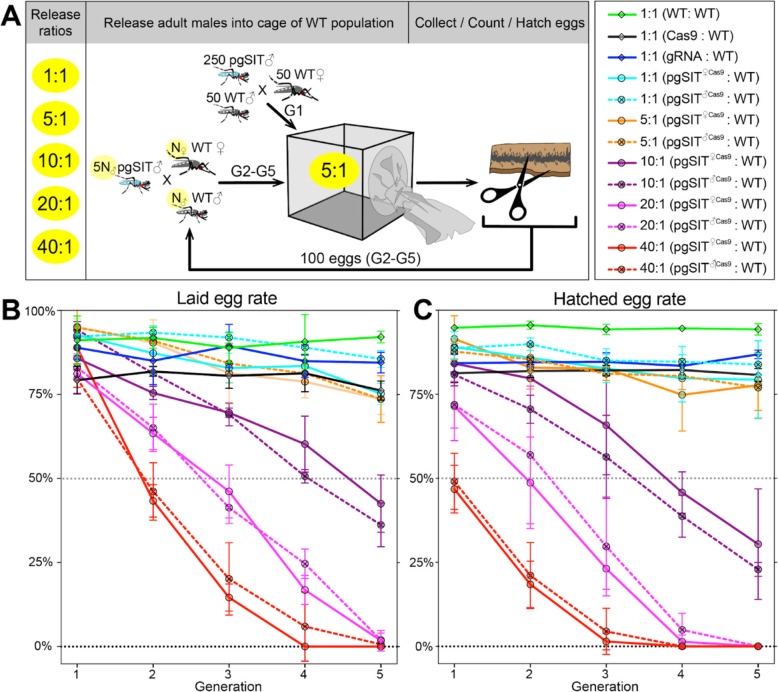

To further explore whether pgSIT ♂’s are competitive enough to mate with WT ♀’s in the presence of WT ♂’s to suppress populations, we conducted multigenerational, population cage experiments. At each generation, adult pgSIT♀cas9 or pgSIT♂Cas9 and WT ♂ mosquitos were released into cages using several introduction frequencies (pgSIT:WT—1:1, 5:1, 10:1, 20:1, and 40:1; Fig. 3A and Supplementary Table 9). Remarkably, both pgSIT♀cas9 ♂ or pgSIT♂Cas9 ♂ behaved similarly, and the high-release ratios (20:1, 40:1) eliminated all populations in five generations (Fig. 3B–C). With lower release ratios of 10:1 and 5:1, we also observed significant suppression of the rates of laid and hatched eggs in the cages. No effect was observed in control cages harboring WT mosquitoes with only Cas9 or gRNA mosquitoes (Fig. 3B–C and Supplementary Table 9). To confirm the sterility of pgSIT ♂’s, hatched larvae were screened for the presence of transgenesis markers each generation. In only 3 out of 30 experimental cages, we scored some larvae harboring transgene markers, though this was very few, indicating that the majority of pgSIT ♂ were indeed sterile (Supplementary Table 9). These findings confirmed the ability of both generated pgSIT♀cas9 and pgSIT♂Cas9 ♂’s to compete with WT ♂’s for mating with WT ♀’s to gradually suppress and eliminate targeted caged populations.

Figure 3. Population suppression in multigenerational population cage experiments.

A Multiple pgSIT:WT release ratios, such as 1:1, 5:1, 10:1, 20:1, and 40:1, were tested in triplicate. A schematic diagram depicts the cage experiments for the 5:1 ratio. To start the 1st generation (G1) of multigenerational population cages, 250 mature pgSIT adult ♂’s were released with 50 similarly aged wildtype (WT) adult ♂’s into a cage, and in one hour 50 virgin ♀’s were added. The mosquitoes were allowed to mate for 2 days before all ♂’s were removed, and ♂’s were blood fed and eggs were collected. All eggs were counted, and 100 eggs were selected randomly to seed the next generation (G2). The sex-sorted adult ♂’s that emerged from 100 eggs (N♂) were released with five times more (5N♂) pgSIT adult ♂’s into a cage, and N♀ ♀’s were added later. The remaining eggs were hatched to measure hatching rates and score transgene markers. This procedure was repeated for five generations for each cage population (Supplemental Table 9). Two types of pgSIT ♂’s were assessed: those that inherited a maternal Cas9 (pgSIT♀Cas9), and those that inherited a paternal Cas9 (pgSIT♂Cas9). B-C Multigeneration population cage data for each release ratio plotting the normalized percentage of laid eggs (B) and hatched eggs (C). Points show means ± SD for each triplicate sample. Source data is provided as a Source Data File.

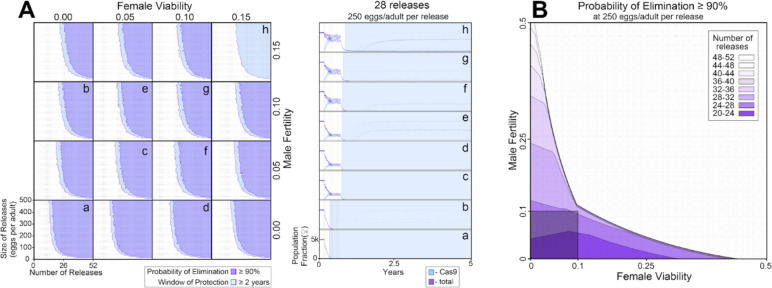

Theoretical performance of pgSIT in a wild population.

To explore the effectiveness of non-optimal pgSIT gene disruption on population suppression outcomes, we simulated releases of pgSIT eggs into a population of 10,000 Ae. aegypti adults (Fig. 4). Weekly releases of up to 500 pgSIT eggs (♀ and ♂) per wild-type adult (♀ and ♂) were simulated over 1–52 weeks. The scale of releases was chosen considering adult release ratios of 10:1 are common for sterile ♂ mosquito interventions29 and ♀ Ae. aegypti produce >30 eggs per day in temperate climates30. A preliminary sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine which parameters population suppression outcomes are most sensitive to (Supplementary Fig. 12). The analysis considered probability of elimination (the percentage of 60 stochastic simulations that result in Ae. aegypti elimination) and window of protection (the time duration for which ≥50% of 60 stochastic simulations result in ≥90% suppression of the Ae. aegypti population) as outcomes, and explored how these vary with number of releases, size of releases, release interval, gRNA cutting rate, Cas9 maternal deposition rate, pgSIT ♂ fertility and mating competitiveness, and pgSIT ♀ viability. Suppression outcomes were found to be most sensitive to release schedule parameters (number, size and interval of releases), ♂ fertility and ♀ viability. Model-predicted efficacy of pgSIT-induced population suppression was then explored in more detail as a function of these parameters through a series of simulations depicted in Fig. 4. Results from these simulations reveal that a window of protection exceeding two years (a common benchmark for interruption of disease transmission) is generally achieved for pgSIT ♀ viability between 0 (complete inviability) and 0.15, and pgSIT ♂ fertility between 0 (complete sterility) and 0.15, provided the release scheme exceeds ~23 releases of ≥100 pgSIT eggs per wild adult (Fig. 4A). Achieving a ≥90% probability of elimination places slightly tighter restrictions on ♀ viability and ♂ fertility - a safe ballpark being ♀ viability and ♂ fertility both in the range 0–0.10, given a release scheme of ~26 releases of 250 pgSIT eggs per wild adult (Fig. 4B). These results suggest a target product profile for pgSIT to be ♀ viability and ♂ fertility both in the range 0–0.10.

Figure 4. Model-predicted efficacy of pgSIT egg releases on Ae. aegypti population suppression as a function of release scheme, male sterility and female viability.

Weekly releases were simulated in a randomly-mixing population of 10,000 adult mosquitoes using the MGDrivE simulation framework55 and parameters described in Table S10. Population suppression outcomes were identified as being most sensitive to model parameters describing the release scheme, male fertility and female viability (Supplementary Fig. 12). A These parameters were varied in factorial experiments assessing suppression outcomes including probability of elimination (the percentage of 60 stochastic simulations that result in Ae. aegypti elimination), and window of protection (the time duration for which ≥50% of 60 stochastic simulations result in ≥90% suppression of the Ae. aegypti population). Female viability was varied between 0 (complete inviability) and 0.15, male fertility was varied between 0 (complete sterility) and 0.15, release size was varied between 0 and 500 eggs released per wild adult, and the number of weekly releases was varied between 0 and 52. Regions of parameter space for which the probability of elimination exceeds 90% are depicted in purple, and in which the window of protection exceeds two years in light blue. Time-series of population dynamics for select parameter sets are depicted in a-h. Here, the total female population is denoted in purple, and the Cas9-carrying female population is denoted in light blue. The light blue shaded region represents the window of protection. Imperfect female inviability and male sterility result in lower probabilities of elimination; however the window of protection lasts for several years for male fertility and female viability in the range 0–0.15 for simulated release schemes. B Regions of parameter space for which the probability of elimination exceeds 90% are depicted as a function of male fertility (x-axis), female viability (y-axis), and the minimum number of weekly releases required to achieve this (shadings, see key). Release size is set to 250 eggs per wild adult. The shaded square depicts the region of parameter space in which male fertility is between 0–10% and female viability is between 0–10%. A ≥90% elimination probability is achieved with ~20–32 weekly releases for pgSIT systems having these parameters.

Mitigation tools for rapid transgene detection.

Being able to rapidly identify transgenes in the environment in mixtures of captured mosquitoes will be important for field applications of genetic biocontrol tools. While PCR based tests do exist, these may be difficult to implement in the field. Therefore, developing an assay with a simple readout would be desired. To generate a rapid assay for transgene detection that could be used alongside future pgSIT field trials, we adapted the sensitive enzymatic nucleic acid sequence reporter (SENSR)31 to rapidly detect pgSIT DNA fragments in Cas9 and gRNAdsx,ix,βTub constructs in mosquitoes. In SENSR, the presence of transgenic sequences triggers the activation of the Ruminococcus flavefaciens CasRx/gRNA collateral activity that cleaves a quenched probe, resulting in a rapid fluorescent readout32,33,31. Multiple ratios of trans-hemizygous pgSIT to WT mosquitoes—0:1; 1:1; 1:5; 1:10; 1:25; 1:50—and a no template control (NTC) were used to challenge SENSR. We found that SENSR effectively detected transgenic sequences from both Cas9 and gRNAdsx,ix,βTub constructs even at the lowest dilution, and no signal was observed in the WT-only and NTC controls (Supplementary Fig. 13). Notably, in every tested ratio, SENSR rapidly detected the transgenic sequence, reaching the half maximum fluorescence (HMF) in less than 20 min (Supplementary Fig. 13B). Taken together, these results validated SENSR as a rapid and sensitive assay for detection of transgenic sequences in pools of mosquitoes which may be an instrumental tool for future field trials.

Discussion

To develop a robust and stable population control technology for addressing insect disease vectors, we engineered a next-generation pgSIT system that induced near complete ♀-specific lethality and ♂ sterility by simultaneously targeting the dsx, ix, and βTub genes. Our cage experiments indicate that releases of pgSIT ♂’s can induce robust population suppression and elimination, and mathematical models reinforce this finding. To support future field trials of this and other trangene-based technologies, we also developed a rapid and sensitive method, SENSR, for identifying pgSIT transgenes.

There were several interesting and unexpected findings in our pgSIT mosquitoes, the main one being that induced ⚥’s did not blood feed normally. In fact, we noticed that ⚥’s had difficulty in penetrating the skin of the mouse, as the proboscis would often bend while probing. Moreover, in rare instances where they could initiate blood feeding, the pgSIT ⚥’s took longer to feed, suggesting that perhaps the disruption of sex determination genes also altered the mechanics of blood feeding. Furthermore, it also appears that the ⚥’s had difficulty in finding hosts, indicting that our induced disruptions may also affect the behavior of host-seeking, but this remains to be explored. This reduction in host-seeking behavior may also be attributed to the mutant maxillary palps, since maxillary palps are known to play a major role in host detection 34–39. Taken together, these observations indicate a potentially more widespread affect of sex determination genes than previously expected, though regardless, the surviving pgSIT ⚥’s are compromised in many ways and will be unlikely to survive in the wild.

Overall, the released pgSIT males were competitive in our cage populations, as repeated releases resulted in population elimination at several introduction frequencies. That said, we did observe some limitations. Firstly, we determined that pgSIT males were not 100% sterile, with an estimated ~1% still producing some progeny. This may stem from using fewer gRNAs to target βTub, as our previous system that saw complete sterility used four gRNAs while here we used only two17. That said, it would not be difficult to build new strains that harbor additional gRNAs targeting βTub or other genes important for male fertility to ensure sterility is achieved. Secondly, we also noticed some reduced fitness parameters when Cas9 was inherited maternally, which may result from an overabundance of Cas9 present in the egg 40. That said, these maternal fitness effects can be avoided by ensuring Cas9 is inherited paternally as pgSIT phenotypes can be achieved when Cas9 is inherited from either the father or mother. Moreover, the longevity was not significantly altered, and released pgSIT males still performed well in the population cages, which indicates that these fitness costs and lack of complete male sterility could be tolerated for population suppression.

Even in the presence of pgSIT construct imperfections, our mathematical modeling showed that population suppression is very promising, both in terms of the potential to eliminate a mosquito population, or to suppress it to an extent that would largely interrupt disease transmission. Our models determined that having ♀ viability and ♂ fertility both in the range 0–10% provides a reasonable target product profile for pgSIT - criteria that the construct described in this study easily satisfies. Previously published analyses17 have also shown fitness costs associated with pgSIT constructs are well-tolerated in the range 0–25%. Overall, our results indicate that perfection is not required for an effective pgSIT system, though improvements to the presented and other systems could allow for reduced introduction ratios.

Before a possible field deployment, there are still several considerations that must be addressed for this pgSIT system41. Firstly, our herein-presented system requires a genetic cross to produce the releasable insects, similarly to previous pgSIT systems15–17 that will require a scalable genetic sexing system. While sophisticated mechanical systems that exploit sex-specific morphological differences have been generated in previous work8 and are available at www.senecio-robotics.com, these approaches may be cost prohibitive. Therefore, there exists a need to develop inexpensive and scalable genetic sexing systems that could be combined with pgSIT to eliminate its reliance on mechanical adult sexing approaches. Alternatively, if a temperature inducible Cas9 strain was generated in Ae. aegypti then it may be possible to generate a temperature inducible pgSIT (TI-pgSIT) system as was done previously 42 and this would alleviate the need for an integrated genetic sexing approach. Secondly, although pgSIT is self-limiting and inherently safe, it does require genetic modification, so regulatory authorizations will be necessary prior to implementation. Despite this, we anticipate that obtaining such authorizations will not be insurmountable. We would expect pgSIT to be regulated similarly to Oxitec’s RIDL technology9, which has already been successfully deployed in numerous locations, including the United States.

Altogether, we demonstrate that removing females by disrupting sex determinate genes is possible with pgSIT, which can inform the development of future such systems in related species. The self-limiting nature of pgSIT offers a controllable alternative to technologies such as gene drives that will persist and uncontrollably spread in the environment. Moving forward, pgSIT could offer an efficient, scalable, and environmentally friendly next-generation technology for controlling wild mosquito populations, leading to widespread prevention of human disease transmission.

Methods

Mosquito rearing and maintenance.

Ae. aegypti mosquitoes used in all experiments were derived from the Ae. aegypti Liverpool strain, which was the source strain for the reference genome sequence 43. Mosquito rearing and maintenance were performed following previously established procedures 17.

Guide RNA design and assessment.

To induce ♀-specific lethality, doublesex (dsx, AAEL009114) and Intersex (ix, AAEL010217) genes were targeted for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated disruption. For each target gene, the DNA sequences were initially identified using reference genome assembly, and then genomic target sites were validated using PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing (see Supplementary Table 1 for primer sequences). CHOPCHOP V3.0.0 (https://chopchop.cbu.uib.no) was used to select the gRNA target sites. In total, we selected 4 dsx gRNAs and 2 ix gRNAs, and assembled the gRNAdsx and gRNAix constructs harboring the corresponding gRNAs. To confirm the activity of the gRNAs in vivo, we generated the transgenic strains harboring either the gRNAdsx or gRNAix constructs, and crossed each gRNA strain to the Cas9 strain17. We sequenced DNA regions targeted by each selected gRNA in F1 trans-hemizygous (aka. gRNA/+; Cas9/+) mosquitoes to assess gRNA/Cas9-induced mutagenesis.

Genetic construct design and plasmid assembly.

All plasmids were cloned using Gibson enzymatic assembly44. DNA fragments were either amplified from available plasmids or synthesized gBlocks™ (Integrated DNA Technologies) using Q5 Hotstart Start High-Fidelity 2X Master Mix (New England Biolabs, Cat. #M0494S). The generated plasmids were transformed into Zymo JM109 chemically competent E. coli (Zymo Research, Cat # T3005), amplified, isolated (Zymo Research, Zyppy plasmid miniprep kit, Cat. #D4036), and Sanger sequenced. Final selected plasmids were maxi-prepped (Zymo Research, ZymoPURE II Plasmid Maxiprep kit, Cat. #D4202) and sequenced thoroughly using Oxford Nanopore Sequencing at Primordium Labs (https://www.primordiumlabs.com). All plasmids and annotated DNA sequence maps are available at www.addgene.com under accession numbers: 200252 (gRNAdsx, 1067B) 200251 (gRNAix, 1055J), 200253 (gRNAdsx,ix,βTub, 1067L) and 164846 (Nup50-Cas9 or Cas9, 874PA).

Engineering transgenic strains.

Transgenic strains were generated by microinjecting preblastoderm stage embryos (0.5–1 hr old) with a mixture of the piggyBac plasmid (100 ng/ul) and a transposase helper plasmid (pHsp-piggyBac, 100 ng/ul). Embryonic collection, microinjections, transgenic lines generation and rearing were performed following previously established procedures 17,45,46.

Genetic assessment of gRNA strains.

To evaluate the activity of gRNAdsx and gRNAix strains, we reciprocally crossed hemizygous mosquitoes of each generated strains to the homozygous Nup-Cas9 strain17, and thoroughly examined F1 trans-hemizygous ♀ progeny (Supplementary Tables 2–3). Each of three established gRNAdsx,ix,βTub strains was subjected to single-pair sibling matings over 5–7 generations to generate the homozygous stocks. Zygosity was confirmed genetically by repeated test crosses to WT. To generate trans-hemizygous progeny with a maternal Cas9 (pgSIT♀Cas9) and paternal Cas9 (pgSIT♂Cas9), homozygous gRNAdsx,ix,βTub ♂’s and ♀’s were mated to homozygous Cas9 ♀’s and ♂’s, respectively. Then, the generated trans-hemizygous mosquitoes were mated to WT mosquitoes of the opposite sex, and numbers of laid and hatched eggs were scored to measure the fecundity. Multiple genetic control crosses were also performed for comparisons: WT ♂ X WT ♀; WT ♂ X Cas9 ♀; Cas9 ♂ X WT ♀; gRNA ♂ X Cas9 ♀; gRNA ♀ X Cas9 ♂; gRNA ♀ X WT ♂; and gRNA ♂ X WT ♀. For the genetic cross, adult mosquitoes were allowed to mate in a cage for 4–5 days, then blood meals were provided, and eggs were collected and hatched. To calculate the normalized percentage of laid eggs per ♀ (e.i. fecundity), the number of laid eggs per ♀ for each genotype replicate was divided by the maximum number of laid eggs per ♀ (Supplementary Table 4). The percentage of egg hatching (i.e. fertility) was estimated by dividing the number of laid eggs by the number of hatched eggs. Egg-to-adult survival ratios were the number of laid eggs divided by the total number of eclosed adults. Larvae-to-adult survival rates were calculated by dividing the number of eclosed adults by the number of larvae. Pupae-adult survival rates were calculated by dividing the number of pupae by the number of eclosed adults. Blood feeding rates were calculated by dividing the number of blood-fed ♀’s or ⚥’s by the total number of ♀ or ⚥’s. Trans-hemizygous ⚥’s had many morphological features visibly different from those of WT ♀’s. To assess differences in external and internal anatomical structures, we dissected twenty trans-hemizygous and control mosquitoes for each genotype and sex (♂, ♀ and ⚥) in 1% PBS buffer and imaged structures on the Leica M165FC fluorescent stereomicroscope equipped with a Leica DMC4500 color camera. The measurements were performed using Leica Application Suite X (LAS X by Leica Microsystems) on the acquired images (Supplementary Table 2).

Validation of induced mutations.

To confirm that the ♀ lethality or transformation correlated with specific mutations at the target loci, dsx and ix gRNA targets were PCR amplified from the genomic DNA extracted from trans-hemizygous and control mosquitoes. PCR amplicons were purified directly or gel purified using Zymoclean Gel DNA Recovery Kit (Zymo Research Cat. #D4007) and then Sanger sequenced. Presence of induced mutations were inferred as precipitous drops in sequence read quality by analyzing base peak chromatograms (Supplementary Fig. 2). The primers used for PCR and sequencing, including gRNA target sequences, are listed in Supplementary Table 1. In addition, induced mutations and their precise localization to six target sites in ix, dsx, and βTub genes were confirmed by sequencing genomes of gRNAdsx,ix,βTub#1/Cas9 ♂’s and ⚥’s using Oxford Nanopore (see below) and aligning them to the AaegL5 genome (GCF_002204515.2). Mutations in the DNA using Nanopore data and mutations in the RNA using RNAseq data were visualized using an integrated genome browser (Supplementary Figs. 7–10).

Ear Johnston’s Organ microanatomy and Immunohistochemistry (IHC).

The heads of two-day old mosquitoes were removed, fixed in 4% PFA and 0.25% Triton X-100 PBS, and sectioned using a Leica VT1200S vibratome. The anti-SYNORF1 3C11 primary monoclonal antibody (AB_528479, 1:30, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB), University of Iowa) and two secondary antibodies, Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (#A-11029, 1:300, ThermoFisher) and anti-horseradish peroxidase 555 (anti-HRP, AB_2338959, 1:100, Jackson ImmunoResearch), were used for IHC. All imaging was conducted using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (FV3000, Olympus). Images were taken with a silicone-oil immersion 60× Plan-Apochromat objective lens (UPlanSApo, NA = 1.3) as previously described 47.

Wing Beat Frequency (WBF) measurements.

Groups of 30 mosquitoes were transferred to 15cm3 cages containing a microphone array (Knowles NR-23158-000) and provided with a source of 10% glucose water. After two days of LD entrainment, audio recordings of mosquito flight behavior were made using a Picoscope recording device (Picoscope 2408B, Pico Technology) at a sampling rate of 50 kHz. These recordings lasted 30 minutes during periods of peak activity during dusk (ZT12.5-13). Audio recordings were then processed and analyzed using the simbaR package in R 48,49. Four separate cages of mosquitoes were tested for each genotype. Statistical comparisons were made using ANOVA on Ranks tests, followed by pairwise Wilcoxon tests with a Bonferroni correction applied for multiple comparisons.

Phonotaxis assays.

Individual ♂’s were provided with a 475 Hz pure tone stimulus calibrated to 80 dB SPL (V ≈ 5 × 10–4 ms−1) provided for 30 seconds by a speaker. Prior to tone playback, a gentle puff of air was provided to each ♂ to stimulate flight initiation. Mosquitoes were considered to demonstrate phonotaxis behaviors if they orientated to the speaker and then demonstrated abdominal bending behaviors. A video camera (GoPro) was used to record all responses to stimulation, with responses being scored as either 0 (no approach/no bending) or 1 (approach and bending). Mosquitoes were tested on two consecutive days, with mosquitoes showing behavior considered as a phonotactic response to stimuli on at least one test day being regarded as responders. Three repeats were conducted for each genotype (across 3 generations), with at least 10 ♂’s tested per repeat. Statistical comparisons were made using Chi-squared tests.

Transgene copy number and genomic integration site.

To infer the transgene copy number(s) and insertion site(s), we performed Oxford Nanopore sequencing of the trans-hemizygous gRNAdsx,ixβTub#1/Cas9 mosquitoes. Genomic DNA was extracted from 10 ♂’s and ♀’s using Blood & Cell Culture DNA Midi Kit (Qiagen, Cat# 13343) and the sequencing library was prepared using the Oxford Nanopore SQK-LSK110 genomic DNA by ligation kit. The library was sequenced for 72 hrs on MinION flowcell (R9.4.1) followed by base calling with Guppy v6.3.2 and produced 16.18 Gb of filtered data with Q score cutoff of 10. To determine transgene copy number(s), reads were mapped to the AaegL5 genome supplemented with transgene sequences gRNAdsx,ix,βTub (1067L plasmid) and Cas9 (874PA plasmid) using minimap2 and sequencing depth was calculated using samtools. To identify transgene integration sites, nanopore reads were mapped to the gRNAdsx,ix,βTub and Cas9 plasmids and the sequences that aligned to the expected regions between the piggyBac sites were parsed. These validated reads were then mapped to the AaegL5 genome (GCF_002204515.2) and sites of insertions were identified by examining the alignments in the Interactive Genomics Viewer (IGV) browser. The gRNAdsx,ix,βTub#1 strain harbors a single copy of gRNAdsx,ix,βTub inserted on chromosome 3 ( +/+ orientation) between 2993 and 16524 at NC_035109.1:362,233,930 TTAA site (Supplementary Fig. 5). We also confirmed the previously identified insertion site of Cas9 17: chromosome 3 (+/+ orientation) between 2933 and 14573 at NC_035109.1:33,210,107 TTAA.

Transcriptional profiling and expression analysis.

To quantify target gene reduction and expression from transgenes as well as to assess global expression patterns, we performed Illumina RNA sequencing. We extracted total RNA using miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Cat# 217004) from 20 sexed pupae: WT ♀’s, WT ♂’s, trans-hemizygous pgSIT♀Cas9 ♂’s, and pgSIT♀Cas9 ⚥’s in biological triplicate (12 samples total), following the manufacturer’s protocol. DNase treatment was conducted using DNase I, RNase-free (ThermoFisher Scientific, Cat# EN0521), following total RNA extraction. RNA integrity was assessed using the RNA 6000 Pico Kit for Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies #5067-1513), and mRNA was isolated from ~1 μg of total RNA using NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (NEB #E7490). RNA-seq libraries were constructed using the NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB #E7770) following the manufacturer’s protocols. Libraries were quantified using a Qubit dsDNA HS Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific #Q32854), and the size distribution was confirmed using a High Sensitivity DNA Kit for Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies #5067– 4626). Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq2000 in paired end mode with the read length of 50 nt and sequencing depth of 20 million reads per library. Base calling and FASTQ conversion were performed with DRAGEN 3.8.4. The reads were mapped to the AaegL5.0 (GCF_002204515.2) genome supplemented with the Cas9 and gRNAdsx,ix,βTub plasmid sequences using STAR aligner. On average, ~97.8% of the reads were mapped. Gene expression was then quantified using featureCounts against the annotation release 101 GTF downloaded from NCBI (GCF_002204515.2_AaegL5.0_genomic.gtf). TPM values were calculated from counts produced by featureCounts. PCA and hierarchical clustering were performed in R and plotted using the ggplot2 package. Differential expression analyses between pgSIT vs WT samples within each sex were performed with DESeq2. Gene Ontology overrepresentation analyses were done with the topGO package.

Blood feeding assays.

Ten mature WT ♀’s or pgSIT ⚥’s (i.e gRNAdsx+ix+βTub#1/Cas9) generated with Cas9 inherited from either the mother (pgSIT♀Cas9) or father (pgSIT♂Cas9) were caged with 100 mature WT ♂’s for two days to insure that every WT ♀ was mated before WT ♂’s were removed from all cages. Then, one anesthetized mouse (similar size and weight) was put into each cage for 20 minutes (from 9:00 am to 9:20 am) daily for five days, and two times were recorded for each mosquito ♀ or ⚥. First, the ‘time to bite’ is the time interval between a mouse placed in a cage and ♀/⚥ landing on the mouse. Second, the ‘feeding time’ is the duration of blood feeding (Supplementary Table 5). When individual ♀/⚥’s finished blood feeding they were removed from the cage, while unfed ♀/⚥’s were kept in the cage and the blood feeding was repeated the next day. In total, each ♀/⚥ had 6000 seconds to initiate bite and feed during 5 days. To assess whether distance affects blood feeding of pgSIT ⚥’s, we conducted the experiment in two sizes of cages: small (24.5 × 24.5 × 24.5 cm) and large (60 × 60 × 60 cm). All experiments were repeated 3 times independently.

Flight activity assays.

We followed the protocol in our previous study17 to assess the flight activity of trans-hemizygous pgSIT♀Cas9 (i.e., gRNAdsx+ix+βTub#1/Cas9) mosquitoes (Supplementary Table 6).

Mating assays.

We followed a previously described protocol17, to assess the mating ability of both types of pgSIT males, pgSIT♀Cas9 and Cas9 pgSIT♂Cas9, and confirm that prior matings with pgSIT ♂’s suppressed WT ♀ fertility (Supplementary Table 8).

Fitness parameters and longevity.

To assess fitness of pgSIT mosquitoes, we measured developmental times, fertility, and longevity of WT, homozygous gRNAdsx+ix+βTub#1, homozygous Cas9, and pgSIT♀Cas9 and pgSIT♂Cas9 mosquitoes. The previously published protocol was used to assess fitness parameters and longevity17. Briefly, all fitness parameters and longevity were assessed in three groups (3 replicates) of twenty individual mosquitoes (Supplementary Table 7).

Multigenerational population cage trials.

To assess the competitiveness of pgSIT ♂’s, we performed discrete non-overlapping multigenerational population cage trials as described in our previous study 17. Briefly, 3/4-day-old mature WT adult ♂’s were released along with mature (3/4 days old) pgSIT adult ♂’s at release ratios (pgSIT: WT): 1:1 (50:50), 5:1 (250:50), 10:1 (500:50), 20:1 (1000:50), and 40:1 (2000:50), with three biological replicates for each release ratio (15 cages total). One hour later, 50 mature (3/4 days old) WT adult ♀’s were released into each cage. All adults were allowed to mate for 2 days. ♀’s were then blood fed and eggs were collected. Eggs were counted and stored for four days to allow full embryonic development. Then, 100 eggs were randomly selected, hatched, and reared to the pupal stage, and the pupae were separated into ♂ and ♀ groups and transferred to separate cages. Three days post eclosion, ratios (pgSIT: WT) of 50 (1:1), 250 (5:1), 500 (10:1), 1000 (20:1), and 2000 (40:1) age-matched pgSIT mature ♂ adults were caged with these mature ♂’s from 100 selected eggs. One hour later, mature ♀’s from 100 selected eggs were transferred into each cage. All adults were allowed to mate for 2 days. ♀’s were blood fed, and eggs were collected. Eggs were counted and stored for 4 days to allow full embryonic development. The remaining eggs were hatched to measure hatching rates and to screen for the possible presence of transformation markers. The hatching rate was estimated by dividing the number of hatched eggs by the total number of eggs. This procedure continued for all subsequent generations.

Mathematical modeling.

To model the expected performance of pgSIT at suppressing and eliminating local Ae. aegypti populations, we used the MGDrivE simulation framework50. This framework models the egg, larval, pupal, and adult mosquito life stages with overlapping generations, larval mortality increasing with larval density, and a mating structure in which ♀’s retain the genetic material of the adult ♂ with whom they mate for the duration of their adult lifespan. The inheritance pattern of the pgSIT system was modeled within the inheritance module of MGDrivE. This module includes parameters for ♀ pupatory success (as a proxy for viability), and ♂ fertility and mating competitiveness. We simulated a randomly-mixing Ae. aegypti population of 10,000 adults and implemented the stochastic version of MGDrivE to capture chance effects that are relevant to suppression and elimination scenarios. Density-independent mortality rates for juvenile life stages were calculated for consistency with the population growth rate in the absence of density-dependent mortality, and density-dependent mortality was applied to the larval stage following Deredec et al.51. Sensitivity analyses were conducted with “window of protection” (mean duration for which the Ae. aegypti population is suppressed by at least 90%), probability of Ae. aegypti elimination, and reduction in cumulative potential for transmission as the outcomes, and model parameters sampled describing the construct (gRNA cutting rate and maternal deposition frequency), release scheme (number, size and frequency of releases), ♀ viability, and ♂ fertility and mating competitiveness. Model parameters were sampled according to a latin-hypercube scheme with 216 parameter sets and 20 repetitions per parameter set. Regression models were fitted to the sensitivity analysis data using multi-layered perceptrons as emulators of the main simulation in predicting the window of protection outcome. Subsequent simulations focused on the most sensitive parameters from the sensitivity analysis (those describing the release scheme, ♀ viability, and ♂ fertility) and were explored via factorial simulation design. Complete model and intervention parameters are listed in Supplementary Table 10–11.

Transgene detection method in mosquitoes.

SENSR assays were performed as described previously52 using a two-step nucleic acid detection protocol. Target sequences were first amplified in a 30 min isothermal preamplification reaction using recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA). RPA primers were designed to amplify 30 bp gRNA spacer complement regions flanked by 30 bp priming regions from the transgenic elements (Cas9 coding sequence or gRNA scaffold for Cas9 or gRNAdsx,ix,βTub construct, respectively) while simultaneously incorporating a T7 promoter sequence and “GGG’’ into the 5′ end of the dsDNA gene fragment to increase transcription efficiency53. The RPA primer sequences and synthetic target sequences can be found in Supplementary Table 12. The RPA reaction was performed at 42°C for 30 min by using TwistAmp Basic (TwistDx #TABAS03KIT). The final conditions for the optimized (28.5% sample input) RPA protocol in a 10-μL reaction are as follows: 5.9 μL rehydration buffer (TwistDx), 0.35 μL primer mix (10 μM each), 0.5 μL MgOAc (280 mM), and 50 ng of genomic DNA. The RPA reaction was then transferred to a second reaction, termed the Cas Cleavage Reaction (CCR), which contained a T7 polymerase and the CasRx ribonucleoprotein. In the second reaction, in vitro transcription was coupled with the cleavage assay and a fluorescence readout using 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM). A 6-nt poly-U probe (FRU) conjugated to a 5′ 6-FAM and a 3′ IABlkFQ (Iowa Black Fluorescence Quencher) was designed and custom-ordered from IDT54. Detection experiments were performed in 20-μL reactions by adding the following reagents to the 10 μL RPA preamplification reaction: 2.82 μL water, 0.4 μL HEPES pH 7.2 (1 M), 0.18 μL MgCl2 (1 M), 1 μL rNTPs (25 mM each), 2 μL CasRx (55.4 ng/μL), 1 μL RNase inhibitor (40 U/μL), 0.6 μL T7 Polymerase (50 U/μL), 1 μL gRNA (10 ng/μL), and 1 μL FRU probe (2 μM). Experiments were immediately run on a LightCycler 96 (Roche #05815916001) at 37°C for 60 min with the following acquisition protocol: 5 sec acquisition followed by 5 sec incubation for the first 15 min, followed by 5 sec acquisition and 55 sec incubation for up to 45 min. Fluorescence readouts were analyzed by calculating the background-subtracted fluorescence of each timepoint and by subtracting the initial fluorescence value from the final value. Statistical significance was calculated using a one-way ANOVA followed by specified multiple comparison tests (n = 4). The detection speed of each gRNA was calculated from the Half-Maximum Fluorescence (HMF) 54. Raw SENSR assays data can be found in Supplementary Table 13.

We generated 12 gRNAs, six target regions within Cas9 or gRNA transgenes, to assess the detection capabilities in a SENSR reaction for each selected gRNA using Cas9 and gRNAdsx,ix,βTub plasmids for detection of Cas9 and gRNAdsx,ix,βTub transgenic sequences, respectively. After identifying the best gRNA for detection of Cas9 and gRNA sequences, we run SENSR of DNA preps made from Ae. aegypti pgSIT♀Cas9 and WT mosquitoes harboring both Cas9 and gRNAdsx,ix,βTub constructs at different ratios of pgSIT♀Cas9 to WT mosquitoes: 1:0; 1:1; 1:5; 1:10; 1:25; 1:50; 0:1; and No Template Control (NTC). We challenged the best gRNA (A4 and B3) in a SENSR assay and found that both gRNA detected transgenic DNA even at the lowest dilution and no signal was observed in both controls, only WT mosquitoes and NTC.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed in JMP8.0.2 by SAS Institute Inc and Prism9 for macOS by GraphPad Software, LLC. We used at least three biological replicates to generate statistical means for comparisons. P values were calculated using a two-sided Student’s t test with equal variance. The departure significance for survival curves was assessed with the Log-rank (Mantel–Cox) texts. Statistical comparisons of WBF for each sex were made using ANOVA on Ranks tests, followed by pairwise Wilcoxon tests with a Bonferroni correction applied for multiple comparisons. Chi-squared test was used to assess significance of departure in phonotaxis assay. All plots were constructed using Prism 9.1 for macOS by GraphPad Software and then organized for the final presentation using Adobe Illustrator.

Ethical conduct of research.

All animals were handled in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as recommended by the National Institutes of Health and approved by the UCSD Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC, Animal Use Protocol #S17187) and UCSD Biological Use Authorization (BUA #R2401).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Judy Ishikawa for helping with mosquito husbandry and Shi-Che Weng for assistance with DNA/RNA extractions. This work was supported in part by funding from NIH (R01AI151004, DP2AI152071, R01GM132825), EPA (Award #RD84020401), and Open Philanthropy (309937-0001) awards to OSA; and the U.S. Army Research Office for the Institute for Collaborative Biotechnologies (W911NF-19-2-0026) and NIH (R01-AI165575) awards to CM; and a NIH (1R01AI143698-01A1) award to JMM. The views, opinions, and/or findings expressed are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official views or policies of the U.S. government.

Footnotes

Competing interests

O.S.A. is a founder of Agragene, Inc. with equity interest. O.S.A., M.L., and N.P.K are founders of Synvect with equity interest. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by the University of California, San Diego in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. All remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Reporting summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Additional information

The online version contains supplementary material available at XX.

Data availability.

Complete sequence maps assembled in the study are deposited at www.addgene.org under ID# 200252 (gRNAdsx, 1067B), 200251 (gRNAix, 1055J) and 200253 (gRNAdsx,ix,βTub, 1067L)). Illumina and Nanopore sequencing data have been deposited to the NCBI-SRA under BioProject ID PRJNA942966, SAMN33705824-SAMN33705835; PRJNA942966, SAMN33705934. Data used to generate figures are provided in the Supplementary Materials/Source Data files (Supplementary Tables 1–11). Aedes transgenic lines are available upon request. Source data is provided with this paper.

References

- 1.Brady O. J. et al. Refining the global spatial limits of dengue virus transmission by evidence-based consensus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6, e1760 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hemingway J., Field L. & Vontas J. An overview of insecticide resistance. Science 298, 96–97 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trdan S. Insecticides Resistance. (BoD – Books on Demand, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu C., Hung Y.-T. & Cheng Q. A Review of Sub-lethal Neonicotinoid Insecticides Exposure and Effects on Pollinators. Current Pollution Reports 6, 137–151 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sánchez-Bayo F. Indirect Effect of Pesticides on Insects and Other Arthropods. Toxics 9, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knipling E. F. Possibilities of Insect Control or Eradication Through the Use of Sexually Sterile Males. J. Econ. Entomol. 48, 459–462 (1955). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laven H. Eradication of Culex pipiens fatigans through Cytoplasmic Incompatibility. Nature vol. 216 383–384 Preprint at 10.1038/216383a0 (1967). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crawford J. E. et al. Efficient production of male Wolbachia-infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes enables large-scale suppression of wild populations. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 482–492 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spinner S. A. M. et al. New self-sexing Aedes aegypti strain eliminates barriers to scalable and sustainable vector control for governments and communities in dengue-prone environments. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology vol. 10 Preprint at 10.3389/fbioe.2022.975786 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Champer J., Buchman A. & Akbari O. S. Cheating evolution: engineering gene drives to manipulate the fate of wild populations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 146–159 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marshall J. M. et al. Winning the Tug-of-War Between Effector Gene Design and Pathogen Evolution in Vector Population Replacement Strategies. Front. Genet. 10, 1072 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang G.-H. et al. Combating mosquito-borne diseases using genetic control technologies. Nat. Commun. 12, 4388 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Website. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26949111.

- 14.Raban R. & Akbari O. S. Gene drives may be the next step towards sustainable control of malaria. Pathogens and global health vol. 111 399–400 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kandul N. P. et al. Transforming insect population control with precision guided sterile males with demonstration in flies. Nat. Commun. 10, 84 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kandul N. P. et al. Precision Guided Sterile Males Suppress Populations of an Invasive Crop Pest. GEN Biotechnology vol. 1 372–385 Preprint at 10.1089/genbio.2022.0019 (2022). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li M. et al. Suppressing mosquito populations with precision guided sterile males. Nature Communications vol. 12 Preprint at 10.1038/s41467-021-25421-w (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salvemini M. et al. Genomic organization and splicing evolution of the doublesex gene, a Drosophila regulator of sexual differentiation, in the dengue and yellow fever mosquito Aedes aegypti. BMC Evol. Biol. 11, 41 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mysore K. et al. siRNA-Mediated Silencing of doublesex during Female Development of the Dengue Vector Mosquito Aedes aegypti. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9, e0004213 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trujillo-Rodríguez G. J. et al. Silencing of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) Doublesex Gene (Dsx) Using iRNAs by Oral Delivery. swen 46, 929–936 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kyrou K. et al. A CRISPR–Cas9 gene drive targeting doublesex causes complete population suppression in caged Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 1062–1066 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scali C., Catteruccia F., Li Q. & Crisanti A. Identification of sex-specific transcripts of the Anopheles gambiae doublesex gene. J. Exp. Biol. 208, 3701 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garrett-Engele C. M. et al. intersex, a gene required for female sexual development in Drosophila, is expressed in both sexes and functions together with doublesex to regulate terminal differentiation. Development 129, 4661–4675 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chase B. A. & Baker B. S. A genetic analysis of intersex, a gene regulating sexual differentiation in Drosophila melanogaster females. Genetics 139, 1649–1661 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akbari O. S. et al. The developmental transcriptome of the mosquito Aedes aegypti, an invasive species and major arbovirus vector. G3 3, 1493–1509 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gamez S., Antoshechkin I., Mendez-Sanchez S. C. & Akbari O. S. The Developmental Transcriptome of Aedes albopictus, a Major Worldwide Human Disease Vector. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics vol. 10 1051–1062 Preprint at 10.1534/g3.119.401006 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Degner E. C. et al. Proteins, Transcripts, and Genetic Architecture of Seminal Fluid and Sperm in the Mosquito Aedes aegypti. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 18, S6–S22 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen J. et al. Suppression of female fertility in Aedes aegypti with a CRISPR-targeted male-sterile mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 118, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carvalho D. O. et al. Suppression of a Field Population of Aedes aegypti in Brazil by Sustained Release of Transgenic Male Mosquitoes. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9, e0003864 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mordecai E. A. et al. Thermal biology of mosquito-borne disease. Ecol. Lett. 22, 1690–1708 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brogan D. J. et al. Development of a Rapid and Sensitive CasRx-Based Diagnostic Assay for SARS-CoV-2. ACS Sens 6, 3957–3966 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brogan D. J. et al. Development of a Rapid and Sensitive CasRx-Based Diagnostic Assay for SARS-CoV-2. ACS Sens 6, 3957–3966 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dalla Benetta E. et al. Engineered Antiviral Sensor Targets Infected Mosquitoes. bioRxiv (2023) doi: 10.1101/2023.01.27.525922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu T. et al. Odor coding in the maxillary palp of the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Curr. Biol. 17, 1533–1544 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Omondi B. A., Majeed S. & Ignell R. Functional development of carbon dioxide detection in the maxillary palp of Anopheles gambiae. J. Exp. Biol. 218, 2482–2488 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Syed Z. & Leal W. S. Maxillary palps are broad spectrum odorant detectors in Culex quinquefasciatus. Chem. Senses 32, 727–738 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bohbot J. D., Sparks J. T. & Dickens J. C. The maxillary palp of Aedes aegypti, a model of multisensory integration. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 48, 29–39 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hill S. R., Ghaninia M. & Ignell R. Blood Meal Induced Regulation of Gene Expression in the Maxillary Palps, a Chemosensory Organ of the Mosquito Aedes aegypti. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution vol. 7 Preprint at 10.3389/fevo.2019.00336 (2019). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Majeed S., Hill S. R., Dekker T. & Ignell R. Detection and perception of generic host volatiles by mosquitoes: responses to CO2constrains host-seeking behaviour. Royal Society Open Science vol. 4 170189 Preprint at 10.1098/rsos.170189 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kandul N. P. et al. Assessment of a Split Homing Based Gene Drive for Efficient Knockout of Multiple Genes. G3 10, 827–837 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kandul N. P. et al. Reply to ‘Concerns about the feasibility of using “precision guided sterile males” to control insects’. Nature communications vol. 10 3955 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kandul N. P., Liu J. & Akbari O. S. Temperature-Inducible Precision-Guided Sterile Insect Technique. CRISPR J 4, 822–835 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matthews B. J. et al. Improved reference genome of Aedes aegypti informs arbovirus vector control. Nature 563, 501–507 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gibson D. G. et al. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat. Methods 6, 343–345 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bui M., Li M., Raban R. R., Liu N. & Akbari O. S. Embryo Microinjection Techniques for Efficient Site-Specific Mutagenesis in Culex quinquefasciatus. J. Vis. Exp. (2020) doi: 10.3791/61375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li M. et al. Development of a confinable gene drive system in the human disease vector Aedes aegypti. Elife 9, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Su M. P., Andrés M., Boyd-Gibbins N., Somers J. & Albert J. T. Sex and species specific hearing mechanisms in mosquito flagellar ears. Nat. Commun. 9, 3911 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Somers J. et al. Hitting the right note at the right time: Circadian control of audibility in mosquito mating swarms is mediated by flight tones. Sci Adv 8, eabl4844 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Su M. P. et al. Assessing the acoustic behaviour of Anopheles gambiae (s.l.) dsxF mutants: implications for vector control. Parasit. Vectors 13, 507 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sánchez H. M. C., Wu S. L., Bennett J. B. & Marshall J. M. MGDrivE: A modular simulation framework for the spread of gene drives through spatially explicit mosquito populations. Methods Ecol. Evol. 229–239 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deredec A., Godfray H. C. J. & Burt A. Requirements for effective malaria control with homing endonuclease genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, E874–80 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brogan D. J. et al. Development of a Rapid and Sensitive CasRx-Based Diagnostic Assay for SARS-CoV-2. ACS Sens 6, 3957–3966 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brieba L. G., Padilla R. & Sousa R. Role of T7 RNA polymerase His784 in start site selection and initial transcription. Biochemistry 41, 5144–5149 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brogan D. J. et al. Development of a Rapid and Sensitive CasRx-Based Diagnostic Assay for SARS-CoV-2. ACS Sens 6, 3957–3966 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Héctor M., Sánchez C., Sean L. Wu, Bennett Jared B., Marshall John M.. MGDrivE: A modular simulation framework for the spread of gene drives through spatially explicit mosquito populations. Methods in Ecology and Evolution (2019) doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.13318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Molnar C. Interpretable Machine Learning. (Lulu.com, 2020).

- 57.A new uncertainty importance measure. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 92, 771–784 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cukier R. I., Fortuin C. M., Shuler K. E., Petschek A. G. & Schaibly J. H. Study of the sensitivity of coupled reaction systems to uncertainties in rate coefficients. I Theory. J. Chem. Phys. 59, 3873 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saltelli A., Tarantola S. & Chan K. P.-S. A quantitative model-independent method for global sensitivity analysis of model output. Technometrics 41, 39–56 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Breiman L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lundberg and Su-In Lee S. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2017/file/8a20a8621978632d76c43dfd28b67767-Paper.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Complete sequence maps assembled in the study are deposited at www.addgene.org under ID# 200252 (gRNAdsx, 1067B), 200251 (gRNAix, 1055J) and 200253 (gRNAdsx,ix,βTub, 1067L)). Illumina and Nanopore sequencing data have been deposited to the NCBI-SRA under BioProject ID PRJNA942966, SAMN33705824-SAMN33705835; PRJNA942966, SAMN33705934. Data used to generate figures are provided in the Supplementary Materials/Source Data files (Supplementary Tables 1–11). Aedes transgenic lines are available upon request. Source data is provided with this paper.