Andrey and Duboule use a historical perspective to discuss how advances in our understanding of molecular genetics and gene regulation have shed light on the etiology of several previously unsolved congenital genetic limb disorders.

Keywords: chromatin, congenital disorder, enhancers, limb development, mutations

Abstract

Congenital genetic disorders affecting limb morphology in humans and other mammals are particularly well described, due to both their rather high frequencies of occurrence and the ease of their detection when expressed as severe forms. In most cases, their molecular and cellular etiology remained unknown long after their initial description, often for several decades, and sometimes close to a century. Over the past 20 yr, however, experimental and conceptual advances in our understanding of gene regulation, in particular over large genomic distances, have allowed these cold cases to be reopened and, eventually, for some of them to be solved. These investigations led not only to the isolation of the culprit genes and mechanisms, but also to the understanding of the often complex regulatory processes that are disturbed in such mutant genetic configurations. Here, we present several cases in which dormant regulatory mutations have been retrieved from the archives, starting from a historical perspective up to their molecular explanations. While some cases remain open, waiting for new tools and/or concepts to bring their investigations to an end, the solutions to others have contributed to our understanding of particular features often found in the regulation of developmental genes and hence can be used as benchmarks to address the impact of noncoding variants in the future.

—“‘Excellent,’ I cried. ‘Elementary,’ said he”

(Dr. J.H. Watson)

Congenital genetic disorders affecting the morphology of mammalian limbs are numerous and have been described, organized, and regularly classified for a long time (e.g., Swanson 1976; Stoll et al. 1998; Mundlos and Horn 2014; Lam et al. 2020). In humans, they are particularly easily detected upon ultrasound screening during pregnancy or at birth and can affect all kinds of aspects, including the length and number of bones, their proper patterning, or their intrinsic organization. Molecular and genomic analyses of such congenital limb anomalies have provided several illustrations of the importance of various signaling pathways and transcription factors for the harmonious embryonic development of these structures (see Mundlos and Horn 2014). Likewise, genetic screens or other approaches carried out in mice have produced a variety of mutant stocks displaying limb malformations and, there again, some of them could be associated with precise genetic alterations within particular genes.

However, a number of such congenital limb disorders either remained unexplained for several decades or were initially attributed to a wrong molecular etiology. The main reason for the existence of such genetic cold cases, as well as the difficulty to resolve them in the past, can be attributed to the way paired limbs appeared in the course of tetrapod evolution. Indeed, all the key signaling pathways and gene regulatory networks (GRNs) implemented during early limb development were co-opted from previous functions, which they usually achieved during the development of the main body axis. As a consequence, structural mutations affecting either the presence or the structure of the proteins would, in most cases, lead to severe syndromes, likely preventing development from proceeding to the end. In some instances, the highly pleiotropic nature of many such genes nonetheless allowed for such localized phenotypes to appear due to the topological individualization of tissue-specific regulatory sequences and their separation from the associated target genes, thus giving them a relative genetic independency (de Laat and Duboule 2013 and references therein). We now understand that the majority of genetic cold cases are due to more or less complex regulatory mutations, which for many years have precluded the discovery of their correct molecular origins.

Over the past 20 yr, several technological and conceptual advances have drastically changed our views of developmental gene regulation. One major advance was the discovery that enhancer sequences (Banerji et al. 1981; Schaffner 2015) can work at a respectable distance from a target promoter (Spitz et al. 2003; Lettice et al. 2003), sometimes as a global regulatory unit such as the globin locus control region LCR (Forrester et al. 1987; Grosveld et al. 1987; Higgs et al. 1990). In addition, pleiotropic regulation, a recurring feature of important developmental genes, is achieved by accumulating enhancers of different specificity over large “regulatory landscapes” (Spitz et al. 2003) that can easily span 1 Mb of DNA (Lettice et al. 2003). Interestingly, it also appeared that regulatory landscapes often match the extent of “topologically associating domains” (TADs) (Dixon et al. 2012; Nora et al. 2012; Sexton et al. 2012); i.e., chromatin subdomains defined by a higher occurrence of internal interactions. As a result, TADs are generally thought to restrict the realm of action of enhancers within a given 3D space and hence may prevent undesirable regulatory interactions from occurring; for example, with a gene located outside a given TAD (e.g., Lupiáñez et al. 2015). TADs are usually separated by series of CTCF binding sites, which act as “boundaries” (e.g., Despang et al. 2019; Anania et al. 2022) by establishing large loops after a cohesin-driven mechanism of chromatin extrusion (for review, see Mirny and Dekker 2022).

With this new knowledge in hand, several genetic cold cases could be reopened. Here, we present a series of them—some having been successfully solved, whereas others are still unclear. In addition to describing the genomic nature of the alterations involved, it is worth asking what these long-lasting and often complex investigations have taught us in terms of the underlying mechanisms and whether such mechanisms can be transferred to other developmental contexts. From an epistemological viewpoint, the cases described below show how powerful the interface is between two disciplines as distinct as basic molecular biology on the one hand and both human and mouse “classical” genetics on the other hand, when occurring at the right time and within a unified theoretical framework.

Ulnaless and mesomelic dysplasias: inverting the regulatory logic

In 1990, Davisson and Cattanach (1990) reported a fully penetrant, X-ray-induced dominant mutation in mice, which they mapped to mouse chromosome 2 by using genetic markers. Homozygous animals were not obtained, and heterozygous specimens displayed a severe phenotype in the limb skeleton—in particular in its middle part, the zeugopod (radius and ulna), with an almost absent ulna; hence, the name “Ulnaless” (Ul). Two years later, Kantaputra et al. (1992) reported the first mesomelic dysplasia (MD; a shortened and ill-formed middle part of the limb skeleton) by analyzing human patients with short limbs. A few years later, they localized this congenital syndrome to human 2q24–2q32 (Fujimoto et al. 1998). In the meantime, the murine HoxD locus, one of the four mammalian clusters of Hox genes, had been mapped to mouse chromosome 2 in a region syntenic with human 2q31 (Featherstone et al. 1988; Stubbs et al. 1990).

This Hox gene cluster (initially referred to as Hox-5) was proposed to underlie the growth and patterning of the developing limb buds (Dollé et al. 1989), a hypothesis verified soon after by gene inactivation (Dollé et al. 1993). The abnormal limb phenotypes obtained were nevertheless not very strong due to the compensatory effect of paralogous genes located on the HoxA cluster, which also turned out to be functional during limb development (Haack and Gruss 1993; Zakany and Duboule 2007 and references therein). As a consequence, the mutation of both Hoxa and Hoxd paralogous genes did elicit drastic effects, such as the almost complete agenesis of the limb extremities in Hoxd13–Hoxa13 double-mutant fetuses (Fromental-Ramain et al. 1996). Likewise, in 1995, the Capecchi laboratory (Davis et al. 1995) reported a strong mesomelic dysplasia phenotype in mice homozygous for a double knockout of Hoxd11 and Hoxa11, two genes essential for the development of the intermediate parts of the limbs, the zeugopods. Mice carrying only three null alleles of Hoxd11/Hoxa11 were much less affected than the full loss of function of both genes, indicating that a single dose of group 11 Hox genes was enough to achieve an almost normal Hox11 function in the zeugopod. This was in marked contrast to the semidominance of the Ul mutation, which produced abnormal limbs similar to those missing all Hox11 function, already in heterozygote mice. As a consequence, a potential link between these two experimentally produced mesomelia remained unnoticed.

However, to further locate the Ul mutation with respect to HoxD, a high-density genetic map of chromosome 2 was created, and no recombination event was observed between Ul and HoxD, indicating a tight association between these two loci and raising the possibility that Ul was indeed allelic to HoxD despite their drastic phenotypic discordance (Peichel et al. 1996). The analysis of Hoxd gene expression in Ul mutant embryos confirmed that the expression of these genes was abnormal in the Ul background; while some genes seemed to be down-regulated, a striking gain of expression of the terminal Hoxd genes was scored (Hérault et al. 1997; Peichel et al. 1997), in particular of Hoxd13, a gene required to build the most distal parts of our limbs, the autopods (hands and feet). In mutant Ul limb buds, Hoxd13 was ectopically expressed as a large patch located exactly within the future zeugopod, while it was down-regulated within its normal expression domain, including future digits. It was thus hypothesized that ectopic HOXD13 proteins negatively interacted with Hox group 11 function, somewhat leading to their combined inactivation (Hérault et al. 1997). However, both the underlying mechanism of this potential loss-of-function-dependent gain of function and the structural nature of the Ulnaless mutation remained unknown.

The Ulnaless mutation was eventually characterized in 2003 by working out the structure of the regulatory landscapes surrounding the HoxD cluster due to the identification of a breakpoint in the newly reported gene Lunapark (Lnp). It turned out to be a rather small inversion containing the entire HoxD cluster itself, in addition to some flanking regions (Spitz et al. 2003). In 2013, the HoxD cluster was shown to depend on a bimodal type of regulation in limbs, with autopodial enhancers on one side of the gene cluster and zeugopodial enhancers on the other side (Fig. 1A; Andrey et al. 2013). Accordingly, the Ulnaless inversion repositioned Hoxd13 close to zeugopodial enhancers, while genes normally responding to zeugopodial enhancers were repositioned toward the other side, leading to their down-regulation (Spitz et al. 2003; Bolt et al. 2021). As a consequence of the proximity between Hoxd13 and zeugopodial enhancers, the gene became transcriptionally activated in future forearm cells, a developmental field from which it is normally absent, likely causing the mesomelia phenotype (Fig. 1B, arrows in schemes at the left). At the same time, this repositioning of Hoxd13 at a distance from most autopodial enhancers led to its down-regulation in future digit cells.

Figure 1.

The mouse Ulnaless allele and a human mesomelic dysplasia. (A) Wild-type genetic configuration at the HoxD locus where the distal (digits) and proximal (arm/forearm) regulatory landscapes are split into two TADs—C-DOM (magenta) and T-DOM (green), respectively—that independently operate on the HoxD cluster, located in between. (Top) The distal/autopodial (magenta) versus proximal/zeugopodial (green) specificities of enhancers are shown on the limb bud schematics. Hoxd13 (thick vertical bar) poorly interacts with the proximal regulatory landscape (T-DOM) and thus is not stably expressed in proximal limbs and hence is specific for the distal aspect (scheme at the left). A control skeletal preparation is shown at the right. (hu) Humerus, (ra) radius, (ul) ulna. (B) In the mouse Ulnaless allele, a conservative inversion (blue arrows) repositions the entire cluster in the middle of the T-DOM, leading to ectopic enhancer–promoter contacts between Hoxd13 and proximal enhancers (green) and a consequent ectopic expression of Hoxd13 in the proximal limb (arrows in the scheme at the left). (Right) Ultimately, this expression leads to the mesomelic dysplasia phenotype, with reduced and ill-formed radius and ulna. Also, the cluster is now far from C-DOM and its digit enhancers (magenta), leading to a Hoxd13 loss of function in digits (scheme at the left). The inversion of the cluster leads to an inversion of the regulations. (C) A case of human mesomelic dysplasia Fryns type, where a duplicated and inverted HoxD cluster repositions one of the two copies of Hoxd13 in the C-DOM, directly in contact with proximal enhancers, likely leading to reduced and deformed radius and ulna (left and right arms in the right X-ray pictures). T-DOM and C-DOM enhancers and arrows, as well as the mouse fetus (left), are transparent, as they show the expected situations as inferred from data obtained in mice (see Bolt et al. 2021). Pictures in A and B are from Herault et al. (1997), and pictures in C are from Le Caignec et al. (2020).

In all reported cases of human mesomelic dysplasia associated with 2q31—Kantaputra type (MDK) (Kantaputra et al. 2010) or Fryns type (MDF; affecting only the arms) (Le Caignec et al. 2020)—the same explanatory framework can be used to account for the bone dysplasia. Indeed, the chromosomal rearrangements found in these patients are systematically suggestive of an up-regulation of HOXD13 in future forearm cells, where this gene should not be expressed (see Bolt et al. 2021). This is exemplified by one MDF patient carrying a duplicated/inverted copy of the HOXD cluster, which brings HOXD13 close to the zeugopodial enhancers (Fig. 1C; Le Caignec et al. 2020), coinciding with a severe mesomelia of both arms. Therefore, the structural understanding of the Ul regulatory mutation helped explain the structural bases for human 2q31 mesomelic dysplasias. However, it did not provide a clear-cut demonstration that ectopic HOXD13 proteins were the direct cause of the phenotype or bring any information regarding the nature of the molecular mechanism involved.

These latter points could only be addressed once CRISPR/Cas9 technology allowed a hypomorph version of the Ul mutation to be reconstructed by using an engineered inversion whose size was slightly larger. As a result of extending the inverted DNA segment, more enhancers were included within the inversion, and hence the number of enhancers left in place (i.e., those that could have misregulated Hoxd13) was reduced. Accordingly, the gain of Hoxd13 was much weaker, and hence mutant mice had less severe phenotypes. As they could be raised as a homozygous stock, additional analyses were carried out (Bolt et al. 2021). First, the targeted inactivation of the Hoxd13 allele contained within the inversion entirely rescued the phenotype, demonstrating that the pathological effect was indeed solely produced by the misexpression of this gene in future zeugopod cells. Second, single-cell analyses suggested that the gain of function of Hoxd13 in zeugopodial cells induced a moderate transcriptional down-regulation of group 11 Hox genes. In addition, the ectopic HOXD13 protein was found to occupy those DNA binding sites normally used by both Hoxa11 and Hoxd11 to exert their regulatory function during the building of zeugopods, suggesting a competition with HOXD13 for these binding sites. These two aspects together may elicit a phenotype that phenocopies the combined Hoxa11/Hoxd11 loss of function in zeugopodial cells.

While human mesomelic dysplasia at 2q31 comes under a variety of complex chromosomal rearrangements (e.g., Dlugaszewska et al. 2006; Kantaputra et al. 2010; listed in Bolt et al. 2021), the mouse Ulnaless mutation is a prototypic example of a simple genetic condition in which DNA is neither gained nor lost and genes and enhancer sequences remain untouched, but modification in their relative topologies severely impacts an important morphology. In this case, only the topological relationships between these various elements are modified, each of them keeping its normal function yet in an inappropriate order, time, and space.

The Liebenberg syndrome: a regulatory endoactivation

In 1973, F. Liebenberg, a South-African orthopedist, described for the first time a local family with abnormalities of all the bony components of the elbow, as well as various misshaped carpal bones—all alterations that are transmitted as autosomal dominant traits (Liebenberg 1973). However, it was only in 2012 and 2013 that more families displaying these features were investigated and that structural variants were found in the proximity of the Pitx1 locus (Spielmann et al. 2012; Al-Qattan et al. 2013). The Pitx1 gene encodes a hindlimb-specific patterning transcription factor (Lanctôt et al. 1999), which was shown to channel hindlimb bud development into a leg identity (Szeto et al. 1999).

In 2012, Spielmann et al. (2012) gave a detailed anatomical description of this genetic condition, where they referred to the Liebenberg phenotype as an “arm-to-leg homeotic transformation.” They wrote that “the distal humerus resembled the distal head of the femur, and the proximal ulna resembled the proximal head of the tibia”; also, the “humerus showed a medial and lateral condyle separated by an intercondylar fossa resembling the femoral epicondyles of the knee” and a “… patella-like structure fused to the distal head of the humerus.” Finally, they noted that the “joint surface of the radius and ulna was flat and resembled that of the tibia and fibula.” In addition, Spielmann et al. (2012) mentioned that the organization of wrist bones looked like that of the ankle, and that soft tissues of the hand (tendons and muscles) resembled those found in the foot.

A mechanistic cause for this pathology was proposed based on the rewiring of an enhancer that would ectopically drive Pitx1 expression in the developing forelimbs. Whereas Pitx1 mRNAs are normally restricted to hindlimb bud cells, ectopic expression would then induce a leg-patterning program in forelimb buds. This was supported by forcing Pitx1 transcription in forelimb bud cells—an approach that partially transformed the arm toward a leg-like morphology (DeLaurier et al. 2006; Spielmann et al. 2012). This potential explanation derived from two distinct overlapping deletions associated with the Liebenberg syndrome, both of which remove the histone variant coding H2afy gene located 150 kb upstream of Pitx1 (Fig. 2A). These deletions would redirect the putative H2afy limb enhancer Hs1473 toward Pitx1, thus triggering its transcription in developing forelimbs. The Liebenberg syndrome was also elicited by a translocation with one breakpoint located 220 kb upstream of Pitx1, whereas the other was on chromosome 18. Similar to the deletions, this chromosomal rearrangement brought the two limb enhancers hs1464 and hs1440 close to Pitx1.

Figure 2.

Pitx1 regulation and the Liebenberg syndrome. (A) Wild-type organization of the Pitx1 locus, including the hs1473 (Pen) enhancer and the histone variant H2afy gene. A translocation breakpoint between chromosome 18 and 224 kb distal to Pitx1 is shown (arrow), as well as two similar deletions that were associated with Liebenberg syndrome patients (Spielmann et al. 2012). (B) In wild-type embryos, the Pitx1 locus adopts different configurations in forelimbs and hindlimbs. In forelimbs (red TAD structure above the locus), the locus disables the contacts between Pitx1 and the Pen enhancer (shadowed dot “Pitx1–Pen” on top), thus maintaining Pitx1 repressed. In hindlimbs (blue TAD structure below the locus), this enhancer–promoter contact is enforced (large arrow and black dot “Pitx1–Pen,” below) and, consequently, Pitx1 is transcribed (blue limb bud in the embryo at the left). These two distinct configurations of the same locus determine the different arm and leg morphogeneses (drawings at the right). (C) In those mutations causing the Liebenberg syndrome, illustrated here with a deletion (del), an ectopic contact between the Pen enhancer and Pitx1 is formed in forelimb buds (large arrow and black dot “Pitx1–Pen” on top), similar to the situation in hindlimb bud cells (below). As a result, Pitx1 is expressed ectopically in forelimb buds (scheme at the left), and the development of the arm is altered, with several features resembling morphologies normally found in the legs such as an ectopic patella, a reduced olecranon, and a bowed radius (schemes at the right). In C, the “mutant” TAD structure is represented including the deletion (white space). In this case, the mutation suppresses the repression of Pitx1, leading to its endoactivation in forelimb bud cells. Micro-CT drawings at the right are taken from Kragesteen et al. (2018).

The development of chromosome conformation capture (3C) approaches confirmed that the frequency of enhancer–promoter physical interactions in the nuclear space generally correlates with their activities (Dekker et al. 2002; Palstra et al. 2003). This was further substantiated genome-wide by using promoter capture technologies in various experimental conditions in vivo (Javierre et al. 2016; Andrey et al. 2017; Freire-Pritchett et al. 2017). Also, experiments involving artificial tethering between enhancers and promoters at the β-globin locus demonstrated that chromatin looping is important for the control of gene expression (Deng et al. 2014; Bartman et al. 2016). At the Pitx1 locus, several contacts were observed in developing hindlimbs between Pitx1 and potential limb enhancers over a 300-kb-long distance. Among those enhancers, the Pen sequence (or hs1473) (Fig. 2B), previously proposed to drive H2afy—rather than Pitx1—transcription, was shown to contribute up to 30% of Pitx1 expression, and its deletion in mice induces a clubfoot phenotype (Kragesteen et al. 2018; Rouco et al. 2021). This observation raised the odd possibility that, in Liebenberg syndrome patients, it is the redirection of an enhancer toward its own target gene that would induce the misexpression of the latter.

When a Pen enhancer–reporter construct was introduced at an exogenous locus, an intense staining was detected in both hindlimb and forelimb buds, rather than displaying a hindlimb-specific expression. The same result was obtained when a lacZ sensor was located near the Pen sequence, illustrating that the regulatory potential of Pen is not restricted to hindlimb cells and is also able to drive gene expression in the forelimb bud, a situation that is prevented during normal development. In the Liebenberg deletions, Pen is thus ectopically driving transcription of its own cognate Pitx1 gene in the wrong tissue, along with the appearance of enhancer–promoter contacts similar to those observed in hindlimb cells (Fig. 2C), a process referred to as gene “endoactivation.” In developing Liebenberg mutant forelimbs, the Pen enhancer is thus no longer sequestered away from the Pitx1 promoter and triggers an ectopic expression sufficient to elicit profound morphological alterations. Additional genetic modifications of the locus showed not only that the absolute distance between the Pitx1 promoter and Pen accounts for the enhancer to be sequestered away, but also that the promoter of H2afy is able to titer the impact of the Pen enhancer in forelimb buds (Kragesteen et al. 2019).

Fifty years after the initial report of the Liebenberg syndrome, the various genetic elements involved in its molecular etiology have thus been identified, and the structure/function differences observed at the Pitx1 locus between the control and mutant conditions have been characterized in some details. The exact reason(s) as to what prevents Pitx1 from responding to Pen in forelimb buds is nevertheless still to be clearly determined. While both the culprit and the murder weapon are known, a full reconstitution of how this happens is still lacking.

Acheiropodia: same culprit, distinct modi operandi

The sonic hedgehog (Shh) locus, its associated 1-Mb-long regulatory landscape, and several mutations in mice and humans have been a rich source of discoveries, in particular regarding long-range gene regulation. Shh and its importance for limb development were reported in 1993 (Riddle et al. 1993). Soon after, the human SHH gene was mapped to chromosome 7q36 (Marigo et al. 1995), close to, yet distinct from, a polysyndactyly disease locus (Heutink et al. 1994; Tsukurov et al. 1994). The murine cognate gene was mapped to a syntenic region in chromosome 5, close to Hemimelic extra-toes (Hx), a mutation known ever since 1967 (see Knudsen and Kochhar 2010). In 1996, the targeted inactivation of Shh led to mice with an acheiropodia phenotype (Chiang et al. 1996)—i.e., an absence of both cheiros (hands) and podos (foot)—a condition much more severe than the polydactylies caused by those disease loci mapped at the vicinity of Shh in both humans and mice, and hence these various conditions remained causally separated.

In 1995, however, the possibility that the Hx mutation would indirectly affect the regulation of Shh was proposed due to the observed anterior ectopic expression of Shh in Hx limb buds (Masuya et al. 1995), yet the first clear regulatory mutation directly affecting Shh and causing a limb morphological anomaly was a transgene insertion event, leading to the so-called “Sasquatch” (Ssq) condition (Sharpe et al. 1999). The investigators proposed that this mutation would affect a specific limb regulatory element controlling Shh at a distance, a hypothesis inspired by a previously reported Shh brain enhancer located 260 kb away from its target gene (Belloni et al. 1996). The precise mapping of this mouse semidominant Ssq mutation identified an insertion/duplication event within intron 5 of the Lmbr1 gene located ∼1 Mb away from Shh (Fig. 3A,B), in the same syntenic interval containing a translocation breakpoint found in a polydactylous human patient (Lettice et al. 2002). In the same study, a cis–trans genetic test using Ssq revealed that this mutation was acting in cis over the Shh gene and hence that the Lmbr1 gene itself was not involved in the various abnormal phenotypes (Lettice et al. 2002).

Figure 3.

Shh long-range limb regulation and acheiropodia. (A) Shh transcription in limb buds is controlled by a long-range interaction (green arrow) between the ZRS (green oval), which is localized within exon 5 of the Lmbr1 gene, at the boundary of the TAD (green; on top), and the Shh promoter (blue arrow) located at the other end of the TAD. Shh is transcribed in the posterior-distal part of the limb buds (scheme in the middle), leading to normal digit number and limb morphology (foreleg skeleton at the right). (sc) Scapula, (hu) humerus, (ra) radius, (ul) ulna. (B) In the mouse Sasquatch mutant, a duplication of the Lmbr1 intron containing the ZRS, together with a transgene insertion (enlargement below), induces an ectopic anterior Shh expression domain, leading to polydactyly. (C) A homozygous deletion within the Lmbr1 gene also containing the ZRS leads to acheiropodia in human patients (X-rays at the right), reproducing the phenotype obtained when the mouse ZRS is deleted. The human condition is thus likely due to a complete loss of function of Shh in limb buds (suggested in the scheme in the middle). (D) The same acheiropodia phenotype is observed in human patients where three CTCF binding sites close to the intact ZRS were included in a short indel. This deletion enables the binding reallocation of CTCF around SHH toward CTCF sites located closer, thus inducing an ectopic boundary (vertical arrow) forming a smaller TAD (green) and isolating the ZRS from the SHH promoter. This likely results in a loss of ZRS–SHH interaction in the limb buds and a full loss of SHH expression there (suggested in the scheme in the middle), accounting for the absence of distal extremities (pictures at the right). (E) The acheiropodia phenotype is also obtained in mice after a partial inversion (black arrows) of the Lmbr1 gene that relocates the ZRS in the neighboring TAD (red) by shifting the position of the boundary closer to Shh due to the presence of ectopic CTCF sites (vertical arrow). There again, the inability of the ZRS to contact Shh induces a full loss of Shh expression (scheme in the middle) and the concurrent phenotype (skeletal preparation at the right). (sc) Scapula, (hu) humerus, (vzg) fused zeugopod. In C–E, the same phenotypes are produced using totally different mechanisms. Pictures in A are from Symmons et al. (2016), and pictures in B are from Sharpe et al. (1999). Pictures in C are reprinted from Shamseldin et al. (2016) with permission from John Wiley and Sons. Pictures in D are from Ianakiev et al. (2001), © 2001, with permission from Elsevier. Pictures in E are from Symmons et al. (2016).

In 2003, the evolutionarily conserved Shh limb-specific enhancer (ZRS) located within the Lmbr intron 5 was characterized, and several human polydactylous patients were shown to carry point mutations within this ZRS sequence. Also, a single G-to-A replacement within the ZRS was eventually identified as the cause of the Hx polydactyly (Lettice et al. 2003). The definitive demonstration that the ZRS was the sole limb-specific enhancer acting on Shh was provided by its targeted deletion in mice, which induced an acheiropodia phenotype similar to that produced by the inactivation of Shh itself (Sagai et al. 2005). Accordingly, ZRS mutations leading to polydactylies were all found to induce anterior gain of Shh expression in limb buds, likely due its transcriptional derepression in these anterior cells (Lettice et al. 2003).

Acheiropodia also exists in the human population. This extremely rare congenital amputation of all limb extremities was initially reported about a century ago in a Brazilian family where four members displayed a complete agenesis of hands/feet accompanied by a reduction of muscular structures in the extremities of long bones (Peacock 1929). Subsequently, from the late 1950s until 1975, several Brazilian families with comparable phenotypes were reported. The transmission mode was determined to be autosomal recessive, and many of the families were consanguineous (Koehler et al. 1956; Freire-Maia et al. 1975). However, despite this spectacular aspect, the genetic origin of this malformation in humans remained unknown until 2016, when an acheiropodia patient unrelated to these Brazilian cases was associated with a deletion at 7q36, containing exons 1–16 of the Lmbr1 gene—i.e., including the ZRS (Shamseldin et al. 2016)—a phenotype in full agreement with the ZRS deletion in mice (Fig. 3C; Sagai et al. 2005).

Surprisingly, however, the ZRS was found present and unmodified in the Brazilian patients displaying a comparable acheiropodia phenotype (Fig. 3D; Ushiki et al. 2021), a paradox that could only be solved using recent concepts derived from the analysis of the 3D genome. Indeed, chromosome conformation capture and DNA-FISH approaches revealed both the spatial proximity between the ZRS and the Shh gene and the presence of these two sequences at both ends of the same TAD (Amano et al. 2009; Symmons et al. 2016; Williamson et al. 2016). Moreover, the relocalization of a TAD boundary element between the Shh gene and the ZRS enhancer was sufficient to block their communication, leading to an acheiropodia-like phenotype (Fig. 3E, arrow; Symmons et al. 2016). This interaction between the ZRS and Shh appears to be largely mediated by several CTCFs present at both TAD borders. While the removal of CTCF binding sites close to the ZRS does not elicit any limb phenotype, it induces a decrease of Shh expression (Paliou et al. 2019; Williamson et al. 2019). However, the combination of such CTCF deletions with a partial ZRS loss of function produces an acheiropodia-like phenotype, suggesting the need for CTCF-mediated enhancer–promoter contacts to achieve normal Shh expression (Paliou et al. 2019).

In the Brazilian acheiropodia families, a homozygous deletion including three CTCF sites was found just downstream from the ZRS, which is left intact (Fig. 3D). Based on previous knowledge, the lack of these CTCF sites should not severely disturb the SHH–ZRS interactions. However, this loss of CTCF sites promoted the reallocation of CTCF interactions with other CTCF sites located in between SHH and the ZRS, leading to the formation of a new anchor loop involving the SHH promoter. This new loop formed an ectopic boundary, thus distracting the SHH promoter from the ZRS, leading to the acheiropodia phenotype (Fig. 3D, arrow; Ushiki et al. 2021). It is important to note that this genomic condition cannot be reproduced in mice because the three CTCF binding sites deleted at the human locus are not conserved in rodents (Ushiki et al. 2021). Indeed, at the mouse Shh locus, the distribution of CTCF sites involved in making the boundary is quite different.

This long and winding inquiry highlighted several critical conclusions related to tissue-specific gene regulation during development. First, enhancer sequences can be located very far from the target promoter, as long as the genomic 3D structure allows—or promotes—productive interactions. As a consequence, the same severe genetic conditions can be produced in different ways, either by affecting (deleting) the enhancer sequence or by preventing its interaction with the target promoter—the same effect obtained through different modi operandi. Finally, while the structure/function of the ZRS itself is well conserved in vertebrates, the mechanism by which it contacts the target promoter can slightly vary even within mammals because what counts, eventually, is that the interaction does occur, rather than how it occurs.

Genomic commensalism at the Gremlin locus

The Shh ZRS enhancer is located within the intron 5 of the Lmbr1 gene, a gene likely coding for a lipocalin transmembrane receptor, a function not directly related to that exerted by the guest enhancer. This particular situation is all but unique and several genes that are important for vertebrate development have one or several of their enhancers located within introns of genes located nearby, usually unrelated in their functions (Borsari et al. 2021). This often caused some confusion when trying to identify those genes affected by a given regulatory mutation, a situation best exemplified by the Gremlin1/Formin1 locus, an extreme case of such genomic commensalism.

In 1985, the Phil Leder laboratory (Woychik et al. 1985) reported transgenic mice with a distinctive phenotype in their limbs. The transgene insertion was mapped to chromosome 2, close to the two limb deformity mutations (ldJ and ldOr) previously reported in 1960 and 1962 (see Vogt et al. 1992), which displayed similar ill-formed limbs. A complementation test revealed that the transgene insertion was allelic, and hence the new mutation was referred to as ldHd (Woychik et al. 1985) (subsequently ldTgHd). In 1990, two companion studies from this same laboratory identified the gene present at the locus and showed that it was disrupted in the ldHd allele (Mass et al. 1990; Woychik et al. 1990). This gene was initially called limb deformity (ld) and subsequently renamed Formin (Fmn1). It was shown to contain a range of exons and to produce several protein isoforms, collectively referred to as “Formins” (Woychik et al. 1990; Wang et al. 1997).

Mice homozygous for ld alleles displayed severe limb malformations, including a synostosis of the zeugopod, along with oligosyndactyly or syndactyly of metacarpal bones (see Zeller et al. 1999). In such mutant limb buds, the distal epithelium-to-mesenchyme signaling that normally regulates limb growth and development is disrupted (Haramis et al. 1995). This signaling involves both the Fgfs and Bmps pathways, which participate in the establishment and maintenance of the SHH/FGF4 feedback loop necessary to implement the growth and patterning of the limb bud (see Zuniga and Zeller 2020). Unexpectedly, however, none of these penetrant ldTgHd phenotypes were observed when some isoforms of the Fmn1 gene were inactivated by homologous recombination (Wynshaw-Boris et al. 1997; Chao et al. 1998), thus raising doubt regarding the real function of the Fmn1 gene.

This paradox was eventually solved in 2003–2004 after several new observations were reported on the structural and functional organization of the Fmn1 locus. First, genomic sequencing revealed that Fmn1 was neighbored by the Gremlin gene (Grem1), located only 40 kb away and transcribed in the opposite direction (Fig. 4A, top; Khokha et al. 2003; Zuniga et al. 2004). Grem1 was isolated as a member of a protein family that antagonizes BMP signaling (Hsu et al. 1998) and was identified as the limb mesenchymal signal capable of relaying Shh signaling to the apical ectodermal ridge (AER), where BMPs are expressed. Also, grafting of Grem1-expressing cells into limb deformity mutant limbs did restore the otherwise interrupted SHH/FGF4 loop (Zúñiga et al. 1999). Second, the inactivation of Grem1 in mouse embryos confirmed its essential role in limb development (Khokha et al. 2003; Michos et al. 2004) with a failure to properly form a functional AER, which in turn affects the propagation of the Shh expression from the polarizing region, as was also observed in ld mutant limb buds (Michos et al. 2004). In addition, the inactivation of Grem1 also affected the morphogenesis of other organs, such as the induction of metanephric kidneys, again similar to the ld mutation.

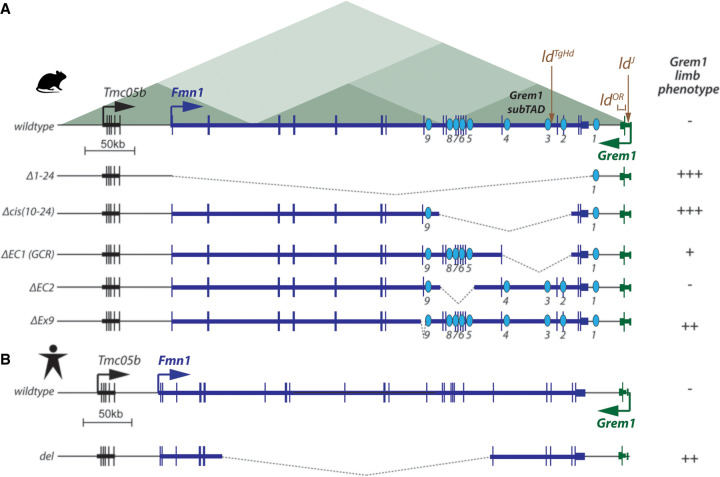

Figure 4.

Genomic commensalism at the Grem1 locus. (A) Organization of regulations at the mouse Grem1 locus, with Formin (Fmn1; blue) and Gremlin1 (Grem1; green) transcribed in opposing directions (arrows on the start sites). These two genes are present in a single TAD, but divided into several subTADs including a “Grem1 subTAD” (green triangles at the top). The limb deformity (ldTgHd) transgene integration is indicated at the top, as well as two other mutations (ldOr and ldJ) affecting the Grem1 coding sequences and splicing, respectively. Grem1 transcription is controlled by a global control region (GCR) as well as by several more distal enhancers (blue ovals), all located within the Fmn1 transcription unit. Below are depicted some deletions in mice that affect Grem1 transcription, with the severity of the phenotype suggested in the column at the right. Two deletions induce full loss of Grem1 expression [Δ1–24 and Δcis(10–24)], whereas the ΔEC1(GCR) leads to a partial Grem1 loss of function only. The ΔEC2 decreases the mRNA level but does not show any skeletal phenotype, whereas the deletion of the Fmn1 exon 9 (ΔEx9) was reported to induce a severe Ld phenotype. (B) The organization of the human locus is virtually identical to the murine counterpart. A deletion within the Fmn1 gene, which removes the equivalent of murine enhancers 5–9 acting over Grem1 (del), induces oligosyndactyly and radio–ulnar synostosis; i.e., part of the Grem1 phenotype.

The definitive demonstration that ld mutations were allelic to Grem1 was obtained by complementation tests in which Grem1 mutant mice were crossed over the ldJ, ldOR, or ldln2 alleles to test for phenotypic rescue (Khokha et al. 2003; Zuniga et al. 2004). As alleles would not complement each other, Khokha et al. (2003) wrote “…we favor the idea that the mapped ld mutations affect Gremlin expression directly and that they lie in cis-regulatory elements for Gremlin expression.” This general conclusion turned out to be correct for several ld alleles including the transgene insertions, which indeed are located within the flanking Gremlin regulatory landscape interspersed within Fmn1 introns (Fig. 4A). However, the precise ldJ allele used to reach this conclusion (Khokha et al. 2003) was not itself a regulatory mutation but instead a point mutation affecting the splicing of Gremlin RNAs, leading to a truncation of the protein (Fig. 4A; Zuniga et al. 2004). Likewise, the ldOR allele was characterized as a deletion of the Gremlin ORF, indicating that the Gremlin complementation group encompasses both the Fmn1 and the Gremlin1 genes (Zuniga et al. 2004). Mutations located either within Gremlin and affecting its structure or within the Fmn1 gene and modifying Grem1 regulation at a distance have all been collectively referred to as ld alleles.

Importantly, the Grem1 and Fmn1 genes are located within the same 450-kb-long TAD, divided into two Fmn1 and Grem1 subTADs (Fig. 4, top; Malkmus et al. 2021). The Fmn1 gene, in particular its 3′ region located within a “Grem1 subTAD,” is filled with regulatory elements, most of which map over a 180-kb region whose previous deletion severely disturbed Grem1 expression in limb buds (del10–24 in Zuniga et al. 2004, 2012; renamed delCis in Malkmus et al. 2021). As many as nine regulatory sequences are dispersed over this region, several of which show a subset of the Grem1 expression pattern when used as transgenes (Malkmus et al. 2021), indicating that the Fmn1 gene is a true enhancer reservoir for its neighboring Grem1 gene, an extreme situation of genomic regulatory commensalism. A partial redundancy between these elements was further shown by spatially distinct but progressive loss of Grem1 expression in ΔEC1 (previously referred to as GCR) and ΔEC2 mutants deleting only a fraction of its enhancer (Fig. 4A; Malkmus et al. 2021; Zuniga et al. 2004). While the function of several such Grem1 enhancers has now been deciphered, it is interesting to see, from a historical perspective, that the effect on Grem1 transcription of the ldTgHd insertional mutations that initiated all this work has not been understood thus far.

This functional description of the Fmn1–Grem1 regulation helped to shed light on the case of a human patient displaying signs of the oligosyndactyly of the four limbs, radio–ulnar synostosis, hearing loss, and unilateral renal aplasia, who had been previously diagnosed with a split hand–foot malformation (Debeer 2004; Dimitrov et al. 2010, 2011). Genomic analyses revealed an ∼250-kb-long deletion covering the 5′ part of the human Fmn1 gene on chromosome 15, and hence a regulatory mutation on Grem1 is the likely cause of this condition (Fig. 4B). However, while this deletion includes some of the Fmn1 intronic Grem1 enhancers (5–9) as described in Malkmus et al. (2021), it does not cover the region previously reported as the global control region (GCR/EC1), which participates in Grem1 transcription in murine limbs (Zuniga et al. 2004). Also, while the human deletion does elicit a strong phenotype, the deletion in mice of most of the enhancers present in the human Del did not show any obvious phenotypic alteration (Fig. 4B, ΔEC2), suggesting potential differences in dosage effects between species.

The necessity or the adaptive value of having such enhancer sequences located within introns of a neighboring gene remains an open question. While this is particularly well illustrated at the Grem1 locus, an almost identical situation exists at the α-globin locus, where several globin genes are controlled by a “superenhancer,” a series of potent enhancers lying nearby, all located within several introns of the Nprl3 gene (Hughes et al. 2005). This peculiar genome organization is also present in lampreys and hence seems to have an old evolutionary origin, predating the separation between agnathans and gnathostomes (Miyata et al. 2020).

One possible explanation is that an ongoing transcription of the host gene may enable these regulatory regions to be more readily accessible whenever functionally required (Borsari et al. 2021). Also, intragenic enhancers may act as alternative promoters, helping to produce isoforms of potential functional interest (Kowalczyk et al. 2012). This transcriptional requirement may shed light on the effect of another chromosomal rearrangement at the Fmn1/Grem1 locus, which is still at odds with our current functional understanding of Grem1 regulation. Indeed, a clear ld phenotype was elicited by a targeted deletion of the mouse Fmn1 exon 9, which was not supposed to contain any critical Grem1 enhancers (Zhou et al. 2009). Northern blot analyses revealed the absence of Fmn1 mRNAs by using probes directed against exons located upstream, indicating a deleterious effect of this deletion either on the Fmn mRNA production or on its stabilization (Zhou et al. 2009). In this perspective, a potential alteration in the transcription of the downstream part of the Fmn1 gene could lead to a weaker activity of the embedded enhancer. While plausible, this possibility would require functional tests in vivo to be verified, as similar hypotheses were assessed at other loci with conflictual outcomes (Anderson et al. 2016; Paliou et al. 2019). The topology of the Fmn1/Grem1 locus could make it an ideal platform to eventually understand this question of general interest for the regulatory genome.

Transposons and lncRNAs—novel tools to reopen cold cases?

Some of the “classical” spontaneous mutations in mice have remained cold cases for a long time, not necessarily due to a lack of appropriate technology, but mostly because of our partial knowledge in particular aspects of gene regulation. For instance, the increasing importance of both transposons and long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) as regulatory factors during development has allowed several closed files to be reopened. Regarding the importance of transposons, the Dactylaplasia (Dac) mutant mice are a good example. Dac mice were first described in 1981 as an autosomal dominant condition driven by two alleles: a mutant gene (Dac) and a modifier allele (mdac) (Chai 1981). In Dac mutant mice, a defect in the maintenance of the limb bud AER induces a loss of phalanges as well as the shortening or fusion of metacarpals and metatarsal bones (Sidow et al. 1999).

In 1999 and then in 2008, the Dac1J and Dac2J alleles were progressively mapped as integrations of MusD transposons into the Fgf8–Fbxw4 interval and in the Fbxw4 gene, respectively (Sidow et al. 1999; Friedli et al. 2008); i.e., at the proximity of Fgf8, a gene essential for the proper function of the AER (Moon and Capecchi 2000). The mdac allele, on the other hand, either enables or precludes the expression of the Dac phenotype in different strains of mice and appears to modulate the AER expression of the MusD transposon (Johnson et al. 1995; Kano et al. 2007). The mdac allele was eventually mapped into a repeated region of chromosome 13, where the permissive alleles appear to lack several KRAB-ZFP genes (Kano et al. 2007; http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/volltextserver/12753/1/diss_AktasT_2011.pdf). Although some progress was made over the past decades on both the mapping and the developmental consequences of the Dac mutation, the molecular mechanism underlying the transposon pathogenicity is still unclear. A plausible hypothesis is that the transposon would hijack the local Fgf8 regulation for its own transcription, leading to an abnormal AER as proposed by Kano and colleagues (Crackower et al. 1998; Kano et al. 2007).

Similarly, the mouse semidominant hemimelia (Dh) mutation has remained a cold case ever since it was described in 1954 (Carter 1954) and classified as part of the “luxoid” group of mutations affecting mice (Grüneberg 1963; Searle 1964). Mutant animals are affected on the preaxial sides of their hindlimbs, with a loss of their tibia and anterior digits due to a reduced width of the limb bud. It is noteworthy to observe that forelimbs are normal in this otherwise highly pleiotropic condition (Searle 1964; Lettice et al. 1999). While the Dh mutation was mapped close to the Engrailed1 (En1) locus (Martin et al. 1990), some recombination events (four out of 563; i.e., ∼500–700 kb in distance) suggested that it was not allelic to the latter gene (Higgins et al. 1992). In addition, the subsequent targeted inactivation of En1 revealed alterations in limbs that are quite divergent from those that were found in Dh mutant mice (Wurst et al. 1994; Loomis et al. 1996), eventually clearing En1 from causing the Dh phenotype.

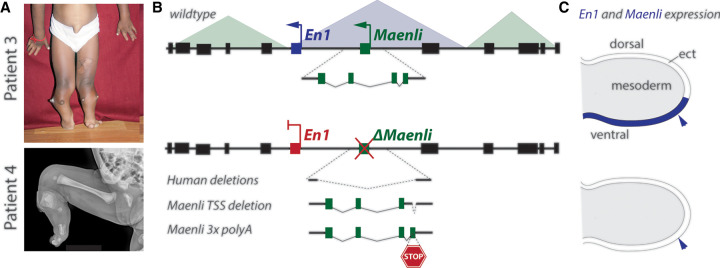

Thirty years after the case of the Dh mouse mutation was closed, three human patients were reported with hemimelia, an almost complete absence of tibia, leading to shortening of the legs, syndactyly, and the presence of nails on the palmar side of several fingers (Fig. 5A; Allou et al. 2021)—a rare phenotype likely derived from a problem in organizing the limb dorso–ventral polarity. In these individuals, small homozygous and overlapping indels 27–63 kb long were identified 300 kb upstream of the human En1 (Fig. 5B; Allou et al. 2021), an essential gene for the dorso–ventral patterning of limb buds (Loomis et al. 1996). These deletions did not involve any known coding sequence yet included a lncRNA named Maenli (Fig. 5B), which in mice is transcribed specifically in the ectoderm of developing limb buds where En1 is at work (Fig. 5C; Loomis et al. 1996). A comparable limb phenotype was found in yet another patient who displayed a loss-of-function mutation within the En1 gene, reinforcing the suspected link between the deleted lncRNA and the regulation of En1 (Fig. 5A, bottom; Allou et al. 2021).

Figure 5.

Severe limb alterations associated with the lncRNA Maenli at the Engrailed1 locus. (A) Documentation of two patients with Engrailed1 (En1)-related loss-of-function phenotypes. Patients 3 and 4 display a strong hemimelia in their legs (X-ray pictures), as well as more distal defects. Patient 3 had an intact En1 gene, whereas patient 4 had a structural mutation within En1 and hence displayed the full range of En1-related phenotypes. In contrast, patients 1–3 had limb-specific phenotypes only, associated with regulatory mutations. (B) At the top is the wild-type En1 locus structure, including the Maenli lncRNA that lies within the same TAD as En1 (blue). In the middle is a scheme showing the genomic interval including the deletions found in the three human patients (including patient 3, shown in A). At the bottom are the schemes of the two targeted inactivations of Maenli—one deleting its transcription start site (TSS), while the other has an integration of three premature transcription termination signals (STOP). (C) At the top is a schematic of the ventral ectoderm-specific expression (in blue) of both En1 and Maenli in control limb buds, whereas all conditions shown in the bottom of B lead to a loss of En1 expression there. Pictures of patients are taken from Allou et al. (2021).

LncRNAs were initially defined as RNAs >200 nt, usually spliced and lacking a clear open reading frame (Kopp and Mendell 2018; but see a recent update in their definition and classification from Mattick et al. 2023). They are abundant in mammals and usually poorly conserved in sequence from one species to another (Hon et al. 2017). Although their function remains unclear in the majority of cases (see Bassett et al. 2014), some of them are involved in key biological processes including gene regulation (Engreitz et al. 2016; Mattick et al. 2023). For example, the Fendrr lncRNA was shown to play an essential and instructive role during lateral plate mesoderm and cardiac differentiation (Grote et al. 2013). In contrast, other lncRNAs seem to achieve their functions more passively by being transcribed rather than through their intrinsic functional values, as shown at the Hand2 locus, where the two lncRNAs Upperhand (Uph) and Handsdown (Hdn) are necessary for embryonic viability and for controlling Hand2 transcription during heart development (Anderson et al. 2016; Ritter et al. 2019). While Uph may activate cardiac enhancers, Hdn transcription was proposed to control 3D chromatin interactions between Hand2 and its enhancers. Likewise, the start site of the Hotdog lncRNA was thought to be involved in triggering chromatin interactions at the HoxD locus (Delpretti et al. 2013), illustrating that cis-acting lncRNAs might act in multiple ways.

The mode of action of Maenli was studied in mice after a deletion was engineered that removed a region homologous to the minimal interval deleted in the human patients. This deletion elicited a comparable phenotype affecting the limb dorso–ventral polarity even though a hindlimb hemimelia was apparently not observed. In such mice, the expression of En1 in the limb bud was almost entirely abrogated (Fig. 5C; Allou et al. 2021). The same phenotype was scored when introducing transcription termination signals right after the start site such that the transcription of Maenli was blocked without deleting any piece of the locus (Fig. 5B). Consequently, the investigators suggested that the process of transcription in itself, independently of what is being transcribed, might be necessary to license the regulatory landscape of En1 for activation. The absence of Maenli transcription would lead to an inactive landscape and concurrent absence of En1 transcription.

This example illustrates how a previously unannotated lncRNA located 300 kb away from a gene that is well known for its role in patterning limb buds can be essential for the tissue-specific expression of this gene during development, as well as for the elucidation of a severe congenital malformation in human patients. This also suggests that the huge number of noncoding RNAs distributed throughout mammalian genomes (Hon et al. 2017; Mattick et al. 2023) might allow some genetic cold cases to be reopened in the future. In the case of the mouse Dh mutation, which is also located close to En1 and displays comparable alterations (though distinct in several aspects), both its structural nature and the affected gene are still elusive, and hence the solution is yet to be found. No doubt this will be solved in the next few years either by sequencing the Dh mutant chromosome or by waiting for a new omics technology that will point to a potential mechanism. Alternatively, novel human patients may be isolated with a hemimelia mapping to this chromosome interval and involving neither Maenli nor the En1 gene directly.

Conclusion

The advent of homologous recombination in ES cells, progressively replaced 30 yr later by CRISPR/Cas9-based approaches, has allowed geneticists to produce targeted modifications of the mammalian genome in an almost unlimited manner, except perhaps for some very large and complex chromosomal rearrangements. As a consequence, however, previous technical limitations were replaced by our restrained capacities to imagine and plan the right modification to achieve in order to understand a precise biological phenomenon. In the case of developmental gene regulation, our current functional approaches (enhancer deletions/mutations, transgenesis, or inversions) follow our own logic and bias, which may not always apply to the millions-years-old evolutionary tinkering that shaped various loci to adapt their transcriptional output to various ontogenetic situations.

The study of both old-fashioned mutations either obtained through genetic screens or occurring spontaneously in animal colonies and of human patients displaying particularly salient congenital phenotypes is of invaluable interest in this context, because random events occurring independently of all experimental design often bring new insights into the various questions to be answered. In this regard, it is important to try to reopen cold genetic cases whenever possible. The fact that numerous developmental mutations in mice are as yet unsolved suggests that they do not involve structural alterations in known genes. Instead, they likely interfere with complex regulatory mechanisms, such as those illustrated in the cases described above. Many of the essential concepts used nowadays to understand long-range gene regulation derive from this approach, and every single case successfully solved will feed this corpus of knowledge under construction.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bob Hill, Lila Allou, Philip Grote, Julian Glaser, Michel Andrey, and Alexandra Preston for information, discussions, and corrections during the preparation of this manuscript, and Aimée Zuniga and Rolf Zeller for comments and corrections. We also thank François Spitz, James Sharpe, and Andrea Superti-Furga for providing original pictures, and Slim Chraiti for taking pictures. Our laboratories are funded by Swiss National Science Foundation grants (PP00P3_176802 and PP00P3_210996 to G.A., and 196868 and 189956 to D.D.), the University of Geneva, and the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Switzerland.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.350450.123.

Freely available online through the Genes & Development Open Access option.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Allou L, Balzano S, Magg A, Quinodoz M, Royer-Bertrand B, Schöpflin R, Chan W-L, Speck-Martins CE, Carvalho DR, Farage L, et al. 2021. Non-coding deletions identify Maenli lncRNA as a limb-specific En1 regulator. Nature 592: 93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qattan MM, Al-Thunayan A, AlAbdulkareem I, Al Balwi M. 2013. Liebenberg syndrome is caused by a deletion upstream to the PITX1 gene resulting in transformation of the upper limbs to reflect lower limb characteristics. Gene 524: 65–71. 10.1016/j.gene.2013.03.120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano T, Sagai T, Tanabe H, Mizushina Y, Nakazawa H, Shiroishi T. 2009. Chromosomal dynamics at the Shh locus: limb bud-specific differential regulation of competence and active transcription. Dev Cell 16: 47–57. 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anania C, Acemel RD, Jedamzick J, Bolondi A, Cova G, Brieske N, Kühn R, Wittler L, Real FM, Lupiáñez DG. 2022. In vivo dissection of a clustered–CTCF domain boundary reveals developmental principles of regulatory insulation. Nat Genet 54: 1026–1036. 10.1038/s41588-022-01117-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KM, Anderson DM, McAnally JR, Shelton JM, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. 2016. Transcription of the non-coding RNA upperhand controls Hand2 expression and heart development. Nature 539: 433–436. 10.1038/nature20128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrey G, Montavon T, Mascrez B, Gonzalez F, Noordermeer D, Leleu M, Trono D, Spitz F, Duboule D. 2013. A switch between topological domains underlies HoxD genes collinearity in mouse limbs. Science 340: 1234167. 10.1126/science.1234167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrey G, Schöpflin R, Jerković I, Heinrich V, Ibrahim DM, Paliou C, Hochradel M, Timmermann B, Haas S, Vingron M, et al. 2017. Characterization of hundreds of regulatory landscapes in developing limbs reveals two regimes of chromatin folding. Genome Res 27: 223–233. 10.1101/gr.213066.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerji J, Rusconi S, Schaffner W. 1981. Expression of a β-globin gene is enhanced by remote SV40 DNA sequences. Cell 27: 299–308. 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90413-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartman CR, Hsu SC, Hsiung CC-S, Raj A, Blobel GA. 2016. Enhancer regulation of transcriptional bursting parameters revealed by forced chromatin looping. Mol Cell 62: 237–247. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett AR, Akhtar A, Barlow DP, Bird AP, Brockdorff N, Duboule D, Ephrussi A, Ferguson-Smith AC, Gingeras TR, Haerty W, et al. 2014. Considerations when investigating lncRNA function in vivo. Elife 3: e03058. 10.7554/eLife.03058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belloni E, Muenke M, Roessler E, Traverse G, Siegel-Bartelt J, Frumkin A, Mitchell HF, Donis-Keller H, Helms C, Hing AV, et al. 1996. Identification of Sonic hedgehog as a candidate gene responsible for holoprosencephaly. Nat Genet 14: 353–356. 10.1038/ng1196-353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolt CC, Lopez-Delisle L, Mascrez B, Duboule D. 2021. Mesomelic dysplasias associated with the HOXD locus are caused by regulatory reallocations. Nat Commun 12: 5013. 10.1038/s41467-021-25330-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Villegas-Mirón P, Pérez-Lluch S, Turpin I, Laayouni H, Segarra-Casas A, Bertranpetit J, Guigó R, Acosta S. 2021. Enhancers with tissue-specific activity are enriched in intronic regions. Genome Res 31: 1325–1336. 10.1101/gr.270371.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter TC. 1954. The genetics of luxate mice. 4. Embryology. J Genet 52: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Chai CK. 1981. Dactylaplasia in mice a two-locus model for development anomalies. J Hered 72: 234–237. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a109486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao CW, Chan DC, Kuo A, Leder P. 1998. The mouse formin (Fmn) gene: abundant circular RNA transcripts and gene-targeted deletion analysis. Mol Med 4: 614–628. 10.1007/BF03401761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang C, Litingtung Y, Lee E, Young KE, Corden JL, Westphal H, Beachy PA. 1996. Cyclopia and defective axial patterning in mice lacking sonic hedgehog gene function. Nature 383: 407–413. 10.1038/383407a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crackower MA, Motoyama J, Tsui L-C. 1998. Defect in the maintenance of the apical ectodermal ridge in the Dactylaplasia mouse. Dev Biol 201: 78–89. 10.1006/dbio.1998.8938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AP, Witte DP, Hsieh-Li HM, Potter SS, Capecchi MR. 1995. Absence of radius and ulna in mice lacking hoxa-11 and hoxd-11. Nature 375: 791–795. 10.1038/375791a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davisson MT, Cattanach BM. 1990. The mouse mutation ulnaless on chromosome 2. J Hered 81: 151–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debeer P. 2004. Bilateral complete radioulnar synostosis associated with ectrodactyly and sensorineural hearing loss: a variant of SHFM1. Clin Genet 65: 153–155. 10.1111/j.0009-9163.2004.00202.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker J, Rippe K, Dekker M, Kleckner N. 2002. Capturing chromosome conformation. Science 295: 1306–1311. 10.1126/science.1067799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Laat W, Duboule D. 2013. Topology of mammalian developmental enhancers and their regulatory landscapes. Nature 502: 499–506. 10.1038/nature12753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLaurier A, Schweitzer R, Logan M. 2006. Pitx1 determines the morphology of muscle, tendon, and bones of the hindlimb. Dev Biol 299: 22–34. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpretti S, Montavon T, Leleu M, Joye E, Tzika A, Milinkovitch M, Duboule D. 2013. Multiple enhancers regulate Hoxd genes and the Hotdog lncRNA during cecum budding. Cell Rep 5: 137–150. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W, Rupon JW, Krivega I, Breda L, Motta I, Jahn KS, Reik A, Gregory PD, Rivella S, Dean A, et al. 2014. Reactivation of developmentally silenced globin genes by forced chromatin looping. Cell 158: 849–860. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Despang A, Schöpflin R, Franke M, Ali S, Jerković I, Paliou C, Chan W-L, Timmermann B, Wittler L, Vingron M, et al. 2019. Functional dissection of the Sox9–Kcnj2 locus identifies nonessential and instructive roles of TAD architecture. Nat Genet 51: 1263–1271. 10.1038/s41588-019-0466-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov BI, Voet T, De Smet L, Vermeesch JR, Devriendt K, Fryns J-P, Debeer P. 2010. Genomic rearrangements of the GREM1-FMN1 locus cause oligosyndactyly, radio–ulnar synostosis, hearing loss, renal defects syndrome and Cenani—Lenz-like non-syndromic oligosyndactyly. J Med Genet 47: 569–574. 10.1136/jmg.2009.073833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov B, Balikova I, de Ravel T, Van Esch H, De Smedt M, Baten E, Vermeesch JR, Bradinova I, Simeonov E, Devriendt K, et al. 2011. 2q31.1 microdeletion syndrome: redefining the associated clinical phenotype. J Med Genet 48: 98–104. 10.1136/jmg.2010.079491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon JR, Selvaraj S, Yue F, Kim A, Li Y, Shen Y, Hu M, Liu JS, Ren B. 2012. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature 485: 376–380. 10.1038/nature11082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlugaszewska B, Silahtaroglu A, Menzel C, Kubart S, Cohen M, Mundlos S, Tumer Z, Kjaer K, Friedrich U, Ropers HH, et al. 2006. Breakpoints around the HOXD cluster result in various limb malformations. J Med Genet 43: 111–118. 10.1136/jmg.2005.033555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollé P, Izpisúa-Belmonte JC, Falkenstein H, Renucci A, Duboule D. 1989. Coordinate expression of the murine Hox-5 complex homoeobox-containing genes during limb pattern formation. Nature 342: 767–772. 10.1038/342767a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollé P, Dierich A, LeMeur M, Schimmang T, Schuhbaur B, Chambon P, Duboule D. 1993. Disruption of the Hoxd-13 gene induces localized heterochrony leading to mice with neotenic limbs. Cell 75: 431–441. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90378-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engreitz JM, Haines JE, Perez EM, Munson G, Chen J, Kane M, McDonel PE, Guttman M, Lander ES. 2016. Local regulation of gene expression by lncRNA promoters, transcription and splicing. Nature 539: 452–455. 10.1038/nature20149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone MS, Baron A, Gaunt SJ, Mattei MG, Duboule D. 1988. Hox-5.1 defines a homeobox-containing gene locus on mouse chromosome 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci 85: 4760–4764. 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester WC, Takegawa S, Papayannopoulou T, Stamatoyannopoulos G, Groudine M. 1987. Evidence for a locus activation region: the formation of developmentally stable hypersensitive sites in globin-expressing hybrids. Nucleic Acids Res 15: 10159–10177. 10.1093/nar/15.24.10159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire-Maia A, Freire-Maia N, Morton NE, Azevedo ES, Quelce-Salgado A. 1975. Genetics of acheiropodia (the handless and footless families of Brazil). VI. Formal genetic analysis. Am J Hum Genet 27: 521–527. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire-Pritchett P, Schoenfelder S, Várnai C, Wingett SW, Cairns J, Collier AJ, García-Vílchez R, Furlan-Magaril M, Osborne CS, Fraser P, et al. 2017. Global reorganisation of cis-regulatory units upon lineage commitment of human embryonic stem cells. Elife 6: e21926. 10.7554/eLife.21926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedli M, Nikolaev S, Lyle R, Arcangeli M, Duboule D, Spitz F, Antonarakis SE. 2008. Characterization of mouse dactylaplasia mutations: a model for human ectrodactyly SHFM3. Mamm Genome 19: 272–278. 10.1007/s00335-008-9106-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromental-Ramain C, Warot X, Messadecq N, LeMeur M, Dolle P, Chambon P. 1996. Hoxa-13 and Hoxd-13 play a crucial role in the patterning of the limb autopod. Development 122: 2997–3011. 10.1242/dev.122.10.2997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto M, Kantaputra PN, Ikegawa S, Fukushima Y, Sonta S, Matsuo M, Ishida T, Matsumoto T, Kondo S, Tomita H, et al. 1998. The gene for mesomelic dysplasia Kantaputra type is mapped to chromosome 2q24-q32. J Hum Genet 43: 32–36. 10.1007/s100380050033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosveld F, van Assendelft GB, Greaves DR, Kollias G. 1987. Position-independent, high-level expression of the human β-globin gene in transgenic mice. Cell 51: 975–985. 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90584-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote P, Wittler L, Hendrix D, Koch F, Währisch S, Beisaw A, Macura K, Bläss G, Kellis M, Werber M, et al. 2013. The tissue-specific lncRNA Fendrr is an essential regulator of heart and body wall development in the mouse. Dev Cell 24: 206–214. 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grüneberg H. 1963. The pathology of development: a study of inherited skeletal disorders in animals. Blackwell, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Haack H, Gruss P. 1993. The establishment of murine Hox-1 expression domains during patterning of the limb. Dev Biol 157: 410–422. 10.1006/dbio.1993.1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haramis AG, Brown JM, Zeller R. 1995. The limb deformity mutation disrupts the SHH/FGF-4 feedback loop and regulation of 5′ HoxD genes during limb pattern formation. Development 121: 4237–4245. 10.1242/dev.121.12.4237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hérault Y, Fraudeau N, Zákány J, Duboule D. 1997. ulnaless (Ul), a regulatory mutation inducing both loss-of-function and gain-of-function of posterior Hoxd genes. Development 124: 3493–3500. 10.1242/dev.124.18.3493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heutink P, Zguricas J, van Oosterhout L, Breedveld GJ, Testers L, Sandkuijl LA, Snijders PJLM, Weissenbach J, Lindhout D, Hovius SER, et al. 1994. The gene for triphalangeal thumb maps to the subtelomeric region of chromosome 7q. Nat Genet 6: 287–292. 10.1038/ng0394-287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins M, Hill RE, West JD. 1992. Dominant hemimelia and En-1 on mouse chromosome 1 are not allelic. Genet Res 60: 53–60. 10.1017/S0016672300030664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgs DR, Wood WG, Jarman AP, Sharpe J, Lida J, Pretorius IM, Ayyub H. 1990. A major positive regulatory region located far upstream of the human α-globin gene locus. Genes Dev 4: 1588–1601. 10.1101/gad.4.9.1588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hon C-C, Ramilowski JA, Harshbarger J, Bertin N, Rackham OJL, Gough J, Denisenko E, Schmeier S, Poulsen TM, Severin J, et al. 2017. An atlas of human long non-coding RNAs with accurate 5′ ends. Nature 543: 199–204. 10.1038/nature21374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu DR, Economides AN, Wang X, Eimon PM, Harland RM. 1998. The Xenopus dorsalizing factor gremlin identifies a novel family of secreted proteins that antagonize BMP activities. Mol Cell 1: 673–683. 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80067-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Cheng J-F, Ventress N, Prabhakar S, Clark K, Anguita E, De Gobbi M, de Jong P, Rubin E, Higgs DR. 2005. Annotation of cis-regulatory elements by identification, subclassification, and functional assessment of multispecies conserved sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 9830–9835. 10.1073/pnas.0503401102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ianakiev P, van Baren MJ, Daly MJ, Toledo SP, Cavalcanti MG, Neto JC, Silveira EL, Freire-Maia A, Heutink P, Kilpatrick MW, et al. 2001. Acheiropodia is caused by a genomic deletion in C7orf2, the human orthologue of the Lmbr1 gene.Am J Hum Genet 68: 38–45. 10.1086/316955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javierre BM, Burren OS, Wilder SP, Kreuzhuber R, Hill SM, Sewitz S, Cairns J, Wingett SW, Várnai C, Thiecke MJ, et al. 2016. Lineage-specific genome architecture links enhancers and non-coding disease variants to target gene promoters. Cell 167: 1369–1384.e19. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KR, Lane PW, Ward-Bailey P, Davisson MT. 1995. Mapping the mouse dactylaplasia mutation, Dac, and a gene that controls its expression, mdac. Genomics 29: 457–464. 10.1006/geno.1995.9981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano H, Kurahashi H, Toda T. 2007. Genetically regulated epigenetic transcriptional activation of retrotransposon insertion confers mouse dactylaplasia phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 19034–19039. 10.1073/pnas.0705483104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantaputra PN, Gorlin RJ, Langer LO. 1992. Dominant mesomelic dysplasia, ankle, carpal, and tarsal synostosis type: a new autosomal dominant bone disorder. Am J Med Genet 44: 730–737. 10.1002/ajmg.1320440606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantaputra PN, Klopocki E, Hennig BP, Praphanphoj V, Le Caignec C, Isidor B, Kwee ML, Shears DJ, Mundlos S. 2010. Mesomelic dysplasia Kantaputra type is associated with duplications of the HOXD locus on chromosome 2q. Eur J Hum Genet 18: 1310–1314. 10.1038/ejhg.2010.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokha MK, Hsu D, Brunet LJ, Dionne MS, Harland RM. 2003. Gremlin is the BMP antagonist required for maintenance of Shh and Fgf signals during limb patterning. Nat Genet 34: 303–307. 10.1038/ng1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen TB, Kochhar DM. 2010. The hemimelic extra toes mouse mutant: historical perspective on unraveling mechanisms of dysmorphogenesis. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today 90: 155–162. 10.1002/bdrc.20181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler RA, Freire-Maia N, Quelce-Salgado A. 1956. Sôbre dois casos de amputações hereditárias. III Semana de Genética 1956: 29. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp F, Mendell JT. 2018. Functional classification and experimental dissection of long noncoding RNAs. Cell 172: 393–407. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk MS, Hughes JR, Garrick D, Lynch MD, Sharpe JA, Sloane-Stanley JA, McGowan SJ, De Gobbi M, Hosseini M, Vernimmen D, et al. 2012. Intragenic enhancers act as alternative promoters. Mol Cell 45: 447–458. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kragesteen BK, Spielmann M, Paliou C, Heinrich V, Schöpflin R, Esposito A, Annunziatella C, Bianco S, Chiariello AM, Jerković I, et al. 2018. Dynamic 3D chromatin architecture contributes to enhancer specificity and limb morphogenesis. Nat Genet 50: 1463–1473. 10.1038/s41588-018-0221-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kragesteen BK, Brancati F, Digilio MC, Mundlos S, Spielmann M. 2019. H2AFY promoter deletion causes PITX1 endoactivation and Liebenberg syndrome. J Med Genet 56: 246–251. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2018-105793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam WL, Oberg KC, Goldfarb CA. 2020. The 2020 Oberg–Manske–Tonkin classification of congenital upper limb differences: updates and challenges. J Hand Surg Eur 45: 1117–1119. 10.1177/1753193420964335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanctôt C, Moreau A, Chamberland M, Tremblay ML, Drouin J. 1999. Hindlimb patterning and mandible development require the Ptx1 gene. Development 126: 1805–1810. 10.1242/dev.126.9.1805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Caignec C, Pichon O, Briand A, de Courtivron B, Bonnard C, Lindenbaum P, Redon R, Schluth-Bolard C, Diguet F, Rollat-Farnier P-A, et al. 2020. Fryns type mesomelic dysplasia of the upper limbs caused by inverted duplications of the HOXD gene cluster. Eur J Hum Genet 28: 324–332. 10.1038/s41431-019-0522-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lettice L, Hecksher-Sørensen J, Hill RE. 1999. The dominant hemimelia mutation uncouples epithelial–mesenchymal interactions and disrupts anterior mesenchyme formation in mouse hindlimbs. Development 126: 4729–4736. 10.1242/dev.126.21.4729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lettice LA, Horikoshi T, Heaney SJH, van Baren MJ, van der Linde HC, Breedveld GJ, Joosse M, Akarsu N, Oostra BA, Endo N, et al. 2002. Disruption of a long-range cis-acting regulator for Shh causes preaxial polydactyly. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 7548–7553. 10.1073/pnas.112212199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lettice LA, Heaney SJ, Purdie LA, Li L, de Beer P, Oostra BA, Goode D, Elgar G, Hill RE, de Graaff E. 2003. A long-range Shh enhancer regulates expression in the developing limb and fin and is associated with preaxial polydactyly. Hum Mol Genet 12: 1725–1735. 10.1093/hmg/ddg180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebenberg F. 1973. A pedigree with unusual anomalies of the elbows, wrists and hands in five generations. S Afr Med J 47: 745–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomis CA, Harris E, Michaud J, Wurst W, Hanks M, Joyner AL. 1996. The mouse Engrailed-1 gene and ventral limb patterning. Nature 382: 360–363. 10.1038/382360a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupiáñez DG, Kraft K, Heinrich V, Krawitz P, Brancati F, Klopocki E, Horn D, Kayserili H, Opitz JM, Laxova R, et al. 2015. Disruptions of topological chromatin domains cause pathogenic rewiring of gene-enhancer interactions. Cell 161: 1012–1025. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkmus J, Ramos Martins L, Jhanwar S, Kircher B, Palacio V, Sheth R, Leal F, Duchesne A, Lopez-Rios J, Peterson KA, et al. 2021. Spatial regulation by multiple Gremlin1 enhancers provides digit development with cis-regulatory robustness and evolutionary plasticity. Nat Commun 12: 5557. 10.1038/s41467-021-25810-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marigo V, Roberts DJ, Lee SMK, Tsukurov O, Levi T, Gastier JM, Epstein DJ, Gilbert DJ, Copeland NG, Seidman CE, et al. 1995. Cloning, expression, and chromosomal location of SHH and IHH: two human homologues of the drosophila segment polarity gene hedgehog. Genomics 28: 44–51. 10.1006/geno.1995.1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GR, Richman M, Reinsch S, Nadeau JH, Joyner A. 1990. Mapping of the two mouse engrailed-like genes: close linkage of En-1 to dominant hemimelia (Dh) on chromosome 1 and of En-2 to hemimelic extra-toes (Hx) on chromosome 5. Genomics 6: 302–308. 10.1016/0888-7543(90)90570-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mass RL, Zeller R, Woychik RP, Vogt TF, Leder P. 1990. Disruption of formin-encoding transcripts in two mutant limb deformity alleles. Nature 346: 853–855. 10.1038/346853a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuya H, Sagai T, Wakana S, Moriwaki K, Shiroishi T. 1995. A duplicated zone of polarizing activity in polydactylous mouse mutants. Genes Dev 9: 1645–1653. 10.1101/gad.9.13.1645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick JS, Amaral PP, Carninci P, Carpenter S, Chang HY, Chen L-L, Chen R, Dean C, Dinger ME, Fitzgerald KA, et al. 2023. Long non-coding RNAs: definitions, functions, challenges and recommendations. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10.1038/s41580-022-00566-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michos O, Panman L, Vintersten K, Beier K, Zeller R, Zuniga A. 2004. Gremlin-mediated BMP antagonism induces the epithelial-mesenchymal feedback signaling controlling metanephric kidney and limb organogenesis. Development 131: 3401–3410. 10.1242/dev.01251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]