Abstract

Background:

Food insecurity affects 13.7 million U.S. households and is linked to poor mental health. Families shield children from food insecurity by sacrificing their nutritional needs, suggesting parents and children experience food insecurity differentially.

Objective:

To identify the associations of food insecurity and mental health outcomes in parents and children

Data Sources:

PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and PsycInfo

Study Eligibility Criteria:

We included original research published in English from January 1990 – June 2020 that examined associations between food insecurity and mental health in children or parents/guardians in the U.S.

Study Appraisal and Synthesis Methods:

Two reviewers screened studies for inclusion. Data extraction was completed by one reviewer and checked by a second. Bias and confounding were assessed using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality RTI Item Bank. Studies were synthesized qualitatively, grouped by mental health outcome, and patterns were assessed. Meta-analyses were not performed due to high variability between studies.

Results:

We included 108 studies, assessing 250,553 parents and 203,822 children in total. Most studies showed a significant association between food insecurity and parental depression, anxiety, and stress, and between food insecurity and child depression, externalizing/internalizing behaviors, and hyperactivity.

Limitations:

Most studies were cross-sectional and many were medium- or high-risk for bias or confounding.

Conclusions and Implications of Key Findings:

Food insecurity is significantly associated with various mental health outcomes in both parents and children. The rising prevalence of food insecurity and mental health problems make it imperative that effective public health and policy interventions address both problems.

Keywords: Food insecurity, mental health, depression, anxiety, parents

INTRODUCTION

Food insecurity, defined as disrupted eating patterns or reduced quality of diet due to an inability to obtain adequate, nutritious food, is a major public health problem in the United States (U.S.).1 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) estimates that 13.7 million U.S. households had food insecurity in 2019, and over half of these households include children.2 Food insecurity is associated with numerous poor health outcomes,3–7 and a growing body of evidence links food insecurity to poor mental health outcomes.8–11 It is hypothesized that this connection is related to increased psychosocial stress and decreased intake of macronutrients important to emotional regulation.12,13

Research emphasizes the importance of mental health in overall well-being.14,15 While adults commonly suffer from depression and anxiety, children incur an additional risk of developing hyperactivity and externalizing/internalizing problems.16 Developing these disorders in childhood is a risk factor for experiencing mental health disorders as an adult. Similarly, parental depression predicts the development of mental health disorders in children.17–19

Children are often protected from substantially reduced quality and quantity of food by federal food supplement initiatives or parents/guardians who sacrifice their nutrition for the child’s.20–23 Therefore, parents and children may differentially experience food insecurity and subsequent mental health outcomes. Additionally, there is little research analyzing how the severity or duration of food insecurity impacts mental health outcomes, making it difficult to create an overall understanding of these variables.

To fill this gap in literature, this systematic review aims to evaluate the associations between food insecurity and mental health outcomes in parents and children. The objectives are to identify the direction and magnitude of the association between food insecurity and mental health in parents and in children, to understand if children’s mental health is spared in exchange for worse parental mental health, and to identify the role of severity and duration of food insecurity in mental health outcomes.

METHODS

This systematic review was conducted and reported per PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews) guidelines. The protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020196178), the international prospective registry for systematic reviews.24

Search Strategy

We searched four electronic databases (PubMed, PsycInfo, Embase, and Web of Science) for the terms food insecurity, food insufficiency, food supply, food poverty, food hardship, or hunger. These terms were cross-searched with terms for various mental health outcomes identified through the Medical Subject Heading database (Table 1). We included studies conducted in the U.S. that were published in English from January 1, 1990 through June 2020. The full search strategy is available in Supplemental 1.

Table 1:

Search strategy for PubMed database

| Number | Searches |

|---|---|

| 1a | “Food supply” or “food insecurity” or “food security” or “food insufficiency” or “food sufficiency” or “food hardship” or “food poverty” or “hunger” |

| 2b | “Anxiety Disorders” [MeSH] or “Mood Disorders” [MeSH] or “Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder” [MeSH] or “Phobic Disorders” [MeSH] or “Bipolar and Related Disorders” [MeSH] or “Neurodevelopmental Disorders” [MeSH] or “Disruptive Behavior Disorders” [MeSH] or “Child Development Disorders, Pervasive” [MeSH] or “Personality Disorders” [MeSH] or “Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders” [MeSH] or “Substance-Related Disorders” [MeSH] or “Trauma and Stressor Related Disorders” [MeSH] or “Behavioral Symptoms” [MeSH] |

| 3 | 1 and 2 |

| 4 | Editorial or comment or letter |

| 5 | 3 NOT 4 |

| 6 | Date published: January 1, 1990 to June 5, 2020 |

| 7 | 5 and 6 |

| 8 | Language: English |

| 9 | 7 and 8 |

Food insecurity terms also included variations of the terms listed.

The current table includes the MeSH database terms that were included in the search strategy. The search strategy also included individual terms within each category (Available in Supplemental Table 1).

Eligibility Criteria

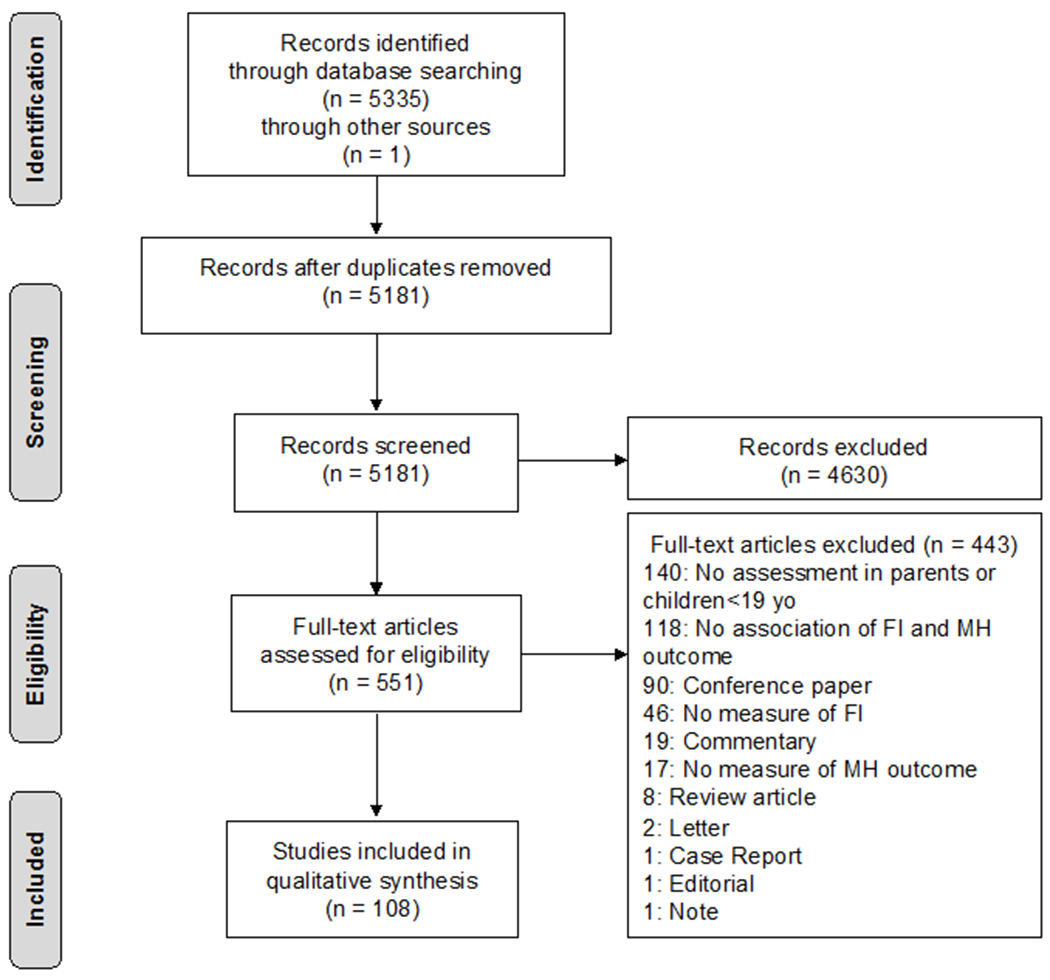

Search results were compiled and duplicates were removed using Covidence.25 Two of three investigators (K.S.C, S.C.M, K.K.P.) screened titles and abstracts (Inter-rater Reliability Cohen’s Kappa ≥0.70). Abstracts were excluded if they were not original research, investigated animal subjects, or did not report an assessment of both food insecurity and a mental health outcome. Two authors (K.S.C with S.C.M, E.C, or N.J.C.) then independently reviewed manuscripts of the remaining articles (Cohen’s Kappa ≥0.80). Studies were included if they assessed the association of food insecurity with a mental health outcome in adults with dependent children or in children 18 years old or younger. A third and fourth author (C.L.B with K.M. or D.P.) resolved discrepancies. The study selection process is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Data Extraction

Data extraction forms were created in Covidence, piloted by multiple investigators, and adjusted as needed. Extracted data included: study design, sample size, sample demographics, definition and measure of food insecurity (e.g. USDA Household Food Security Survey Module, Hunger Vital Sign), mental health outcome (e.g. depression, anxiety), measure assessing mental health outcome (e.g. Patient Health Questionnare-9), and relationship of food insecurity to the mental health outcome via odds ratios, relative risks, relative risk ratios, and logistic regressions with their respective confidence intervals and statistical significance. The duration and severity of food insecurity was extracted when provided. Covariates for each analysis were extracted as well. Sample demographics that were extracted included, but were not limited to, age, sex, race, ethnicity, language spoken, household income, insurance status, and education level. In studies that divided their results by other demographics factors (such as rural vs. urban environment) those important demographic dividers were also extracted so results could be reported with the appropriate context. We also noted if a study used nationally representative data given that their results might be better extrapolated to recognize patterns across the United States. Data extraction was performed by one investigator (S.C.M., E.C., K.K.P, or N.J.C.) and checked by a second (K.S.C.). Discrepancies were reviewed by a third author (C.L.B.).

Study-Quality Assessment

Two investigators (K.S.C., and S.C.M., E.C., K.K.P, or N.J.C.) independently determined risk of bias and confounding. Discrepancies were reviewed by a third author (C.L.B.). We utilized the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Research Triangle Institute (RTI) Item Bank to assess risk of bias and confounding.26 The risk of bias assessment reviews the selection of participants, differences between study groups, length and loss to follow up, selection of primary outcomes, and believability of results. In addition, bias that may affect the cumulative evidence was considered. Risk of bias was operationalized by total score with a score of zero indicating “low-risk,” a score of one indicating “medium-risk,” and a score of two or more, or the presence of a fatal flaw, indicating “high-risk.” The risk of confounding assessment reviews validity and reliability of measures as well as the attempt to balance the allocation between groups. For risk of confounding, scores were similarly operationalized by total score with a score of zero indicating “low-risk,” a score of one indicating “medium-risk,” and a score of two or more, or presence of a fatal flaw, indicating “high-risk.”

Qualitative Analysis

Studies were grouped by mental health outcome and patterns were assessed. We compared whether studies used validated vs. non-validated measures for both food insecurity and the mental health outcome. We then compared results between studies based on a variety of factors such as study design, food insecurity factors (severity, duration, persistence vs transient nature) and sample demographics (age, sex, race, ethnicity, etc.). This allowed for a qualitative assessment of the overarching patterns, and then for a more detailed analysis to understand if those patterns persisted for various demographic groups. Studies used diverse measures for both food insecurity and mental health outcomes, leading to high variability between studies. This limited our ability to combine mental health outcome data for meta-analysis.

RESULTS

Study Characteristics

The electronic database search yielded 5335 articles. Duplicates were removed and 5180 abstracts were screened. Of these, 4630 abstracts were excluded, and the remaining 550 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. One hundred and eight articles met inclusion criteria and were included in the qualitative review (Fig. 1). All studies were observational: 56 cross-sectional, 49 prospective cohort, 2 retrospective cohort, and 1 case-control. Studies surveyed parents only (n=61), children only (n=30), or parents and children (n=17). Study characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Table 2:

Study Characteristics

| Author and Publication Year | Population | Sample Size | Study Design | Sex, % Female | Age a | Race |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adynski 2019 27 | Low-income mothers | Stress: 842; Depression: 845; Anxiety:846 | Prospective Cohort | 100% | 25.68 (5.76) | African American (AA) 53.8%; Hispanic (H) 24.2%; White (W) 22% |

| Ajrouch 2010 28 | AA women in a high-poverty | 736 Mothers | Cross-sectional | 100% | 30.8 (SE 0.3) | AA 100% |

| Alaimo 2002 29 | NHANES for 15-16 yr olds | 754 Adolescents | Cross-sectional | 49.30% | 15: 46.8% 16: 53.2% |

W 66.7%; AA 15.4%; Mexican-American 7.8% |

| Ashiabi 2007 30 | Families with a child 6-11 yrs old | 9,645 Parent-child dyads | Cross-sectional | Parent 81.9%; Child 51.25% | Parents: 37.19 (7.61) Children: 8.39 (1.72) |

W 69.12%; H 16.81%; AA 14.07% |

| Austin 2017 31 | Urban, low-income women | 296 Mothers | Cross-sectional | 100% | 33.2 (10.6) | AA 56.5%; H 23.3%; W/Other 14.5% |

| Becker 2017 32 | Food pantry clients in TX | 503 Adults | Cross-sectional | 76.50% | < 25: 2.2%; 25-50: 39.4%; 51-65: 33.4% 66-75: 18.7%; > 75: 6.0% |

Latino/H 64.6%; AA 16.5%; W 11.33%; Other 6.4% |

| Becker 2019 33 | Food pantry clients in TX | 891 Adults | Cross-sectional | 67.30% | 42.07 (14.36) | Latinx/H 76.2%; W 10.1%; AA 5.9%; Other 7.8% |

| Bergmans 2018 34 | Women with SNAP | W2: 243 W3: 241 W4: 235 Mothers |

Prospective Cohort | 100% | <18: 4.7% 18-30: 80.5% 30-40: 14.5% ≥ 40: 0.4% |

AA 62.1%; H 21.5%; W 13.3%; Other 3.1% |

| Bernard 2018 35 | Parent-child dyads | 58 Parent-child dyads | Cross-sectional | Parent 97%; Child 40% | Parent: 37.4 (10.36) Child: 10.56 (2.48) |

Parent AA 76%; W 14%; Other 9%; Missing 2% |

| Black 2012 36 | Urban, low-income families | 26,950 Caregiver-child dyads | Cross-sectional | Caregiver NR; Child 46.8% | Caregiver: 25.6 (5.9); Child: 11.3 mos (9.6) | Children AA 55.2%; H 29.9%; W 13.0%; NA 0.8%; Asian: 1.1% |

| Braveman 2018 37 | Postpartum Californian women | 27102 Mothers | Cross-sectional | 100% | 15-19: 6.4%; 20-24: 19.8%; 25-29: 26.6% 30-34: 27.8%; ≥35: 19.4% |

Latina 49.8%; W 29.3%; Asian/Pacific Islander (PI) 14.7%; AA 5.7%; American Indian (AI)/ Alaska Native/other 0.5% |

| Bronte-Tinkew 2007 38 | Parents of young children | 8693 Parents | Prospective Cohort | Parent NR; Child 48.9% | Mother at child's birth: 27.56 (SE 6.4) Child: 10.5 mos (SE 1.9) |

NR |

| Browder 2012 39 | Mothers in rural America | 476 Mothers | Prospective Cohort | 100% | 30.19 | W 67.2%; Latina 25.0%; AA 7.8% |

| Bulock 2014 40 | Rural, low-income mothers | 215 Mothers | Prospective Cohort | 100% | 30.66 | W 71.8%; H/Latina 15%; AA 7.0%; Native American (NA) 0.9%; Multi-Racial 5.0%; Other: 0.5% |

| Burke 2016 41 | Children and Adolescents | 16,918 Children 14,143 Adolescents |

Cross-sectional | 49.2% | Children (Age 4-11yo): 54.4% Adolescents (Age 12-17yo): 45.6% |

Children: W 57.5%; Black, non-Hispanic 13.8%, Other, non-Hispanic 22.6%, Hispanic 6.2% Adolescents: W 59;9%, Black, non-Hispanic 13.8%, Other, non-Hispanic 20.6%, Hispanic 5.7% |

| Casey 2004 42 | Mothers in 5 states | 5,306 Mothers | Cross-sectional | 100% | NR | AA 51.4%; H 34.7%; W 11.9% |

| Chilton 2014 43 | Low-income families | 44 Mothers | Cross-sectional | 100% | Mother: 26.7 (6.6); Child: 17.7 mos (9.6) | Mothers: AA 70.5%; H 22.7%; W 6.82% |

| Coffino 2020 44 | NESARC-III | 36,145 Adults | Cross-sectional | 52% | 46.5 (0.199) | W 66.2%; H 14.8%; AA 11.8%; Other 7.3% |

| Darling 2017 45 | College freshmen | 98 Young Adults | Cross-sectional | 75% | 18.23 (0.74) | W 66%; AA 20%; More than one race 10%; Other 4% |

| Dennison 2019 46 | Children of Seattle, WA | 94 Children | Cross-sectional | 48.9% | 13.57 (3.47) | W 51.1%; AA 17.0%; H 13.8%; Asian 10.6%; Biracial/Other; 7.5% |

| Distel 2019 47 | Children of Mexican-origin immigrant families | 104 Children | Prospective Cohort | 61% | 8.39 | NR |

| Doudna 2015 48 | Rural families | 314 Mothers | Cross-sectional | 100% | Approx. 30 | Non-H W 63.1% |

| Eiden 2014 49 | Low-income children | 216 Mother-child dyads | Prospective Cohort | Parent 100%; Children 51% | Mother: 29.53 (6.06) Child: at K 5.52 (0.36) |

Mothers AA 72% |

| Ettekal 2019 50 | Low-income families | 169 Mother-child dyads | Prospective Cohort | Parents 100% Children 51% |

Mothers:29.78 (5.46) | Mothers AA 74% |

| Fernández 2018 51 | Urban 9-year-olds | 3,508 Children | Cross-sectional | Parents 100%; Children 52.5% | Mothers: 34.4 (6.0) | Mothers AA 51.9%; W 30.7%; Latina 25.2%; Asian 2.3%; NA 4.2%; Other 10.9% |

| Frazer 2011 52 | Rural, low-income families | W1: 413 W2: 314 W3: 265 |

Prospective Cohort | NR | Parents W1: 30.1; Youngest Child W1: Med 2.0, Range 0-13 | W1: W 64.6%; Latino 21.5%; AA 8.8%; NA 0.2%; Asian 0.2%; Multiracial/Other 4.6% |

| Garg 2015 53 | Low-income mothers | 2,917 Mothers | Prospective Cohort | 100% | 25.5 (SE 5.8) | W 37.5%; H 34.8%; AA 22.5%; Asian/PI 2.1%; Other 3.1% |

| Gee 2018 54 | Kindergarteners in FI homes | 1,040 Children | Retrospective Cohort | 45.10% | 65.73 mos (4.07) | H 38.6%; W 36%; AA 14.5%; Asian 2.1%; Other: NA, PI, or multiracial 8.5% |

| Gee 2019 55 | Early Childhood Longitudinal Study (ECLS), K Cohort | 7,820 Parent-child dyads | Prospective Cohort | Parents 85% Children 49.1% | NR | Children W 57%; H 22% AA 12%; Asian 4% |

| Gill 2018 56 | Low-income mothers | 4,125 Mothers | Cross-sectional | Children 49.0% | Mothers: 30.8 (6.5) Children:2.6 (1.3) | Mothers H/Latina 85.1%; AA 7.2%; W 4.5%; Asian/PI 2.2% |

| Greder 2017 57 | Rural, low-income children | 370 Mother-child dyads | Cross-sectional | Children 50.3% | Mothers: 32.6 (8.54) Children: 6 (3.25) | Mothers W 66.5%; Latina 24.1%; AA 7.9%; AI or Alaskan Native 2.9%; Asian 1.2%; PI 1.2%; Other 10%; More than once race 10.3% |

| Grineski 2018 58 | 1st graders in TX | 11,958 Children | Cross-sectional | 48.40% | Children: 85.45 mos (44.43) | H 25.2% ; AA 13.3%; Asian 4.4%; Other 5.5% |

| Guerrero 2020 59 | Infants born in 1998-2000 | 3,630 Children | Prospective Cohort | Children with FI 9% | NR | Children with FI AA 11%; H 11%; W 8%; Other 7% |

| Hall 2018 60 | High school students | 7,641 Students | Cross-sectional | 53.00% | NR | H 100% |

| Hanson 2012 61 | Low-income families | 225 Families | Cross-sectional | NR | Parents: 30 | Non-W 33.8% |

| Harrison 2008 62 | Pregnant women | 1,386 Pregnant Women | Cross-sectional | 100% | ≤17: 17.3% 18-19: 18.2% 20-24: 35.0% 25-29: 16.4% ≥30: 13.1% |

AA 44.0%; Asian/PI 19.2%; H (any race) 15.7%; AI 13.9%; W 5.4%; Multiracial 1.7% |

| Hatem 2020 63 | Fragile Families and Child Well-Being Study (FFCWS) | 2,626 Adolescents | Prospective Cohort | 49% | Mothers: 28.16 (6.01) | Adolescents AA 49%; W 27%; H 24% |

| Heflin 2009 64 | Parents with newborn children | Y1: 3,541 Y3: 3,516 |

Prospective Cohort | Parents 100% | Parent Y1: 26.5 Youngest Child Y1: 2.3 | Y1: AA 47.9%; H 24.9%; W 23.5%; Other 3.8% |

| Heflin 2005 65 | Female welfare recipients | 753 Mothers | Prospective Cohort | 100% | ≥35 W1: 27.0% | W1 AA 50%; W 50% |

| Heflin 2008 66 | Panel Study of Income Dynamics | 4,438 Families | Prospective Cohort | NR | Parent: 43.21 (SE 10.18) Youngest Child: 4.01 (SE 5.35) | W 61.6%; AA 30.5%; Other 7.9% |

| Helton 2019 67 | FFCWS | 2,330 Mother-child dyads | Prospective Cohort | Children 48% | Mothers: 25.28 Children: 61.87 mos | AA 49%; H 27% |

| Hernandez 2014 68 | FFCWS | 1,690 Families | Prospective Cohort | Parents 100% | Mothers: 28.42 (6.05) | AA 44%; H 26%; W 26%; Other 3% |

| Himmelgreen 1998 69 | Puerto Rican women | 82 Mothers | Cross-sectional | 100% | Mothers: 33.3 (5.4) | Puerto Rican 100% |

| Horodynski 2018 70 | Growing Healthy Project | 567 Families | Cross-sectional | Caregiver NR; Child 51% | Caregiver: 29.5 (6.7) Children: 49.0 mos (6.1) | Caregivers W 62%; AA 30%; H/Other 8% |

| Howells 2020 71 | Pregnant women after Hurricane Florence | 83 Mothers | Cross-sectional | 100% | Mothers: 30.9 | W 88.0%; H 4.8%; AA 3.6%; Other 3.6% |

| Hromi-Fiedler 2011 72 | Low-income, pregnant Latinas | 135 Women | Cross-sectional | 100% | Mothers: 25.24 (5.65) | Puerto Rican 65.2%; Non-Puerto Rican Latina 34.8% |

| Huang 2016 73 | Children in K to fifth grade | 7,348 Children | Cross-sectional | Children 49.53% | Mothers: 32.8 (5.8) Children: 68.4 (4.3) | W 60.0%; H 19.3%; AA 13.9%; Other 6.8% |

| Huddleston-Casas 2009 74 | Rural, low-income mothers | W1: 413 W2: 325 W3: 270 |

Prospective Cohort | 100% | Mothers: 30.04 (7.72) | W 62.2%; H/Latina 21.4%; AA 11.2%; Other 5.1% |

| Jacknowitz 2015 75 | Children | 7,850 Children | Prospective Cohort | Children 49.5% | NR | Children W 36.8%; H 24%; AA 19.2%; Other 20.0% |

| Jackson 2017 76 | ECLS, K Cohort | 6,531 Children | Prospective Cohort | 49% | NR | Non-W 37% |

| Jackson 2017 77 | ECLS, Birth Cohort | 4,721 Adults | Prospective Cohort | NR | NR | NR |

| Johnson 2018 78 | Low-income households | 2,800 Children | Prospective Cohort | 48% | Children: 68.07 mos (4.42) | Mothers W 42%; H 32%; AA 20%; Asian 6% |

| Johnson 2018 79 | Children born in 2001 | 3,600 Children | Prospective Cohort | 9 mo cohort 50%; 2 yr cohort 49%; Preschool cohort 48% | 68.15 mos (4.39) at 2 yr follow-up: 68.07 mos (4.37) at Preschool follow-up: 68.01 mos (4.36) | at 9 mo. W 39%; H 32%; AA 20%; Other 9% |

| Koury 2020 80 | Economically disadvantaged mothers | 219 Mother-child dyads | Cross-sectional | 100% | NR | NR |

| Kim 2012 81 | At-risk mothers | 324 Mothers | Cross-sectional | 100% | <20: 13% ≥20: 87% |

H or Latina 50.0%; AA 25.3%; W 16.4%; Other 8.4% |

| Kimbro 2015 82 | Children in FI households | 6,300 Children | Retrospective Cohort | 50% | Mothers: 33.7 Children: 73.70 mos | W 53%; H 26%; AA 12%; Asian 4%; Other 5% |

| King 2017 83 | Urban children | 2,829 Children | Cross-sectional | Parent 100%; Child 48% | Children: approx. 5 yrs old | NR |

| King 2018 84 | FFCWS | 2,488 Children | Prospective Cohort | Parents 100%; Children NR | NR | Mothers AA 52.7%; W 22.4%; H 21.6% |

| Kleinman 2002 85 | Inner-city children | 97 Children | Prospective Cohort | Children 59% | NR | Children: AA or H >70% |

| Kleinman 1998 86 | CCHIP study | 328 Children | Cross-sectional | Parents 84%; Children 47% | Child: 8.4 | NR |

| Laraia 2015 87 | Pregnant women | 526 Mothers | Prospective Cohort | 100% | Mothers: 30.06 (5.2) | W/Other 87.6%; AA 11.9% |

| Laraia 2009 88 | Low-income, first-time AA mothers | 206 Mothers | Prospective Cohort | Parents 100% | Mothers: 22.66 (3.77) | AA 100% |

| Laraia 2006 89 | Mothers | 606 Mothers | Prospective Cohort | 100% | Mothers: 27.2 (5.6) | W 58.9%; AA 33.2%; Other 7.9% |

| Lent 2009 90 | Poor, rural families | 29 Families | Prospective Cohort | Parents 100% | Mothers:29.3 | Non-H W 89.7% |

| Letiecq 2019 91 | Central American immigrant mothers | 134 Mothers | Cross-sectional | Parents 100% | Mothers: 34.63 (7.35) | Latina/H 100% |

| McLaughlin 2012 92 | Adolescents, NCS-A 2001 to 2004 | 6,483 Parent-child dyads | Cross-sectional | NR | Children: Range 13-17 | NR |

| Mersky 2017 93 | Low-income women | 1,241 Mothers | Prospective Cohort | Parents 100% | Mothers: 24.2 (5.7) | W 33.2%; AA 27.4%; H 22.6%; AI 8.0%; Other 8.9% |

| Munger 2016 94 | Mothers with SNAP | 1,225 Mothers | Prospective Cohort | Parents 100% | NR | AA 42%; H 30%; W 24%; Other 4% |

| Murphy 1998 95 | Low-income children | 101 Parent-child dyads | Prospective Cohort | Parents NR, Children 53% | NR | AA 80% |

| Nagata 2019 8 | Low-income Latino households | 168 Mother-child dyads | Prospective Cohort | Children 49.2% | Mothers at 4-yr follow-up: 30.4 (5.3) | Mexican 59.5%; Other 40.5% |

| Nelson 2016 96 | Children | 4,900 Children | Prospective Cohort | Children 54% | Mothers: 29.4 | W 58.8%; H/Latino 26.1% AA 15.2%; Asian 2.6%; Multiracial/Other 5.5% |

| Niemeier 2019 97 | 10-12th grade students | 1493 Children | Cross-sectional | Children 53.9% | NR | H 52.8% |

| Noonan 2016 98 | ECLS, Birth cohort | Sample A: 8150; Sample B: 9100; Sample C: 7800; Mothers | Prospective cohort | Parents 100% | Mothers at child's birth Sample A: 27.9 (6.31) Sample B: 27.6 (6.34) Sample C: 27.6 (6.29) |

Maternal characteristics at birth, Sample A AA 15.6%; H 15.4%; Asian/PI 13.4%; AI 4.4% |

| Phojanakong 2020 99 | Families with young children | 372 Caregivers | Prospective Cohort | Parents 94.1% | Parents: 28.0 (11.4) | AA 91.1%; H 3.5%; W 2.4%; Other 3.0% |

| Poll 2020 100 | Male collegiate athletes | 111 Young Adults | Cross-sectional | Adults 0% | 21 (2), Range 19-23 | W 56.8%; AA 34.2%; Other/Multiracial: 5.6%; AI or Native Alaskan 1.8%; H 0.9%; Hawaiian/PI: 0.9% |

| Poole-Di Salvo 2016 101 | 12-16 year-old students | 8,600 Adolescents | Cross-sectional | Adolescents 47.8% | Mothers <30: 7.2%; 30-47: 76.9%; >47: 15.9%; Child (range; 12.33-16.90) | W 57.1%; H 18.4%; AA 17.3%; Other 7.2% |

| Potochnick 2019 102 | H/Latino Youth | 1,362 Youth | Cross-sectional | Children 49.2% | Children:12.2 | H 100% |

| Pulgar 2016 103 | Latina Women in farmworker families | 248 Mother-child dyads | Cross-sectional | Parents 100% | 18-25: 29.0% 26-35: 55.7% 36-45: 15.3% |

NR |

| Raiford 2014 104 | Young, AA women in resource-poor communities | 237 Mothers | Cross-sectional | Parents 100% | Mothers 17.6 (1.0) | AA 100% |

| Richards 2020 105 | Pregnant women | 752 Mothers | Prospective Cohort | Parents 100% | Mothers:28.9 (5.6) | W 64.6%; H 20.4%; AA 5.5%; Other 9.5% |

| Rodriguez-JenKins 2014 106 | Families with child welfare | 771 Caregivers | Cross-sectional | Caregivers 92% | Caregivers 32.4 | W 62%; AA 5%; AI/Alaskan Native 6.6%; Latino 5.4%; Asian American/PI 1.9%; Multiracial 17.1% |

| Rongstad 2018 107 | Children | 1,330 Children | Cross-sectional | Children 50.3% | 0-1: 5%; 2-5: 36%; 6-10: 32%; 11-15: 20%; 16-20: 7% | W 77.4%; H/Latino 8.4%; AA 4.7%; Asian 4.3%; Multiracial/Other 5.2% |

| Rose-Jacobs 2008 108 | Low-income families | 2,010 Caregiver-child dyads | Cross-sectional | Children 53.6% | Caregiver <21: 14.2%; Children 4-12m: 40%; 13-24m: 39%; 25-36m: 21% | Caregiver AA 59.3%; H 19.8%; W 19.7%; Asian 1%; NA 1% |

| Rose-Jacobs 2019 109 | Pregnant women on opioid agonist treatment | 75 Women | Cross-sectional | Parents 100%; Children 52.3% | Mothers: 28.8 (5.2) | Mothers W, non-H 82.9% |

| Rose-Jacobs 2019 110 | Pregnant women being treated for opioid use | 100 Women | Cross-sectional | Parents 100% | Mothers: 28.6 (5.1) | W/non-H 73.0% |

| Rosenthal 2015 111 | Disadvantaged pregnant young women | 484 Mothers | Prospective Cohort | Parents 100% | Mothers: 18.66 (1.68) | Latina 54.5%; AA 33.5% |

| Salas-Wright 2020 112 | Venezuelan immigrant children | 399 Children | Cross-sectional | Children 43.61% | Children:14.4 (1.75) | NR |

| Sun 2016 113 | Mothers | 1,255 Mothers | Cross-sectional | Parents 100% | Caregiver: Median 24, Range 22-28 Child: Median 18.5mos, Range 9-31 |

H 47.5%; AA 39.0%; W 10.6%; Other 3% |

| Sidebottom 2014 114 | Women at urban community health center | 594 Mothers | Prospective Cohort | Parents 100% | Mothers: 21.9 (5.45); <20: 39.5%; 20-24: 36.6%; ≥25: 23.8% | AA 50.5%; NA 20.2%; Asian/PI 16.0%; H 7.7% W 3.9%; Multiple 1.7% |

| Siefert 2007 115 | Low-income, AA mothers | 824 Mothers | Cross-sectional | Parents 100% | Mothers 18-24: 36.7%; 25-34: 50%; 35-54: 13.2% | AA 100% |

| Siefert 2001 116 | Single women receiving welfare | 724 Mothers | Cross-sectional | Parents 100% | Mothers 25-34: 46.3%; ≥35: 25.7% | AA 55.8%; Non-H W 44.2% |

| Slack 2005 117 | Families receiving welfare | W1: 1,363 W2: 1,183 Children |

Prospective Cohort | Children 47.8% | Children 3-5: 37.8%, 6-12: 62.2% | Caregiver: AA 78.7%; Children: AA 80% |

| Slopen 2010 118 | Children | 2,810 Children | Prospective Cohort | Children 50.50% | Caregiver: 35.58 (0.31) Children: 8.16 (0.05) | Children H 42.54%; AA 31.92% W 13.82%; Other 11.72% |

| Ten Haagen 2014 119 | Families in Boston | 308 Families | Prospective Cohort | Caregivers 100% | Mothers: 33.88 (7.46) | AA 47%; H 33%; W 7%; Other 13% |

| Testa 2020 120 | Adolescents | 12,228 Adolescents | Prospective Cohort | 54.40% | NR | W 56.6%; AA 19.7%; H 15.6%; Other 8.1% |

| Thomas 2019 121 | Children ages 2 to 17 yrs | 29,341 Children | Cross-sectional | Children 48.5% | Children: 9.65 (4.69) | Children W 50.5%; H 27.3%; AA 14.0%; Asian 5.8%; Other 2.5% |

| Trapp 2015 122 | Low-income, preschool children | 222 Children | Cross-sectional | Children 50% | Children: 35mos (8.7) | Puerto Rican 61%; H, non-Puerto Rican 29%; AA 10% |

| Tseng 2017 123 | Matched child-parent data from the 2014 to 2015 NHIS | 18,456 Parent-child dyads | Cross-sectional | Parents 61% | Parents 18-29: 22%; 30-39: 34%; ≥40: 44% | Parents W 56.7%; H 21.5%; AA 11.6%; Other 10.3% |

| Vaughn 2016 124 | NESARC | 34,427 Adults | Prospective Cohort | 51.94% | 49.1 (17.3) | W 70.67%; AA 11.29%; H 4.31%; Other 11.37% |

| Wu 2018 125 | ECLS, Birth Cohort | 6,970 Children | Prospective Cohort | Parents 100%; Children 49.2% | NR | Children W 40.8%; H 20.0%; AA 15.6%; Asian/PI 11.6% NA/Alaskan Native 3.4%; Multiracial 8.4% |

| Ward 2019 126 | Families in AR | 693 Caregivers | Cross-sectional | Caregivers 100%; Children 50.8% | NR | AA 55.7%; W 22.2% H 14.3%; Other 7.8% |

| Weinreb 2002 127 | Homeless and low-income mothers and children | 322 Mothers 355 Children |

Case-control | Caregivers 100%; Children 45.4% | Mothers: 30.4 Children: School-aged: 10.1; 57.2% Preschool-aged: 4.2; 42.8% | Mothers: Puerto Rican 41.8%; W 33.5%, AA 13.4%, Other 11.2% |

| West 2019 128 | Adolescents in Project EAT | 2,179 Adolescents | Prospective Cohort | 52.80% | 14.9 (1.6) | W 63.42%; Asian 19.18%; AA 10.00%; H 3.95%; Other 2.75% |

| Whitaker 2006 129 | Mothers and preschool aged children | 2,870 Mother-child dyads | Cross-sectional | Parents 100% | NR | Mothers AA 50.7%; H 23.4%; W 22.6%; Other 3.3% |

| Whitsett 2019 130 | Welfare, Children, and Families Study | 1,049 Children | Prospective Cohort | Children 54% | Caregiver: 38.03 (7.71) Children: 12.02 (1.39) | Caregiver AA 41%; H 53%; W 5% |

| Willis 2016 131 | Middle school students | 324 Children | Cross-sectional | Children 53.60% | Children: 11.4 (0.92) | Children: W 52.10%; H 20.70% |

| ZasLow 2009 132 | ECLS, Children Cohort | 8,944 Children | Prospective Cohort | Parents 100%; Children 48.9% | Mothers at child’s birth: 27.3 (13.1) Children: 24.4mos (2.5) |

Children W 43.1%; Other 20.9%; H 20.2%; AA 15.9%; |

| Zekeri 2019 133 | AA single mothers living with HIV/AIDS | 190 Mothers | Cross-sectional | Parents 100% | NR | AA 100% |

Table 2: Study characteristics for the 108 studies included in qualitative analysis, including information regarding FI.

Mean (SD) in years, unless otherwise indicated.

Mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated. Abbreviations: AA, African American; H, Hispanic; W, White; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; FI, Food Insecurity; NR, not reported; RCFIM, Radimer Cornell Food Insecurity Measure; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; W1, Wave 1; W2, Wave 2; W3, Wave 3; W4, Wave 4; HVS, Hunger Vital Sign; USDA, United States Department of Agriculture; HFSSM, Household Food Security Survey Module; PI, Pacific Islander; AI, American Indian; FS, Food Security; LFS, Low Food Security; VLFS, Very Low Food Security; NA, Native American; NESARC-III, National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III; CCHIP, Community Childhood Hunger Identification Project; FFCWS, Fragile Families and Child Welfare Study; K, Kindergarten; MFS, Marginal Food Security; NCS-A, National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement; ECLS, Early Childhood Longitudinal Study; NCAA, National Collegiate Athletic Association; EAT, Eating Among Teens and Young Adults; HIV/AIDS, Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

Food Insecurity

Food insecurity was defined using 10 validated and eight non-validated measures. Most studies (n=84) measured food insecurity at the household level, while 11 studies used a parent-level measure and 18 studies assessed food insecurity at the child level. The majority of studies (n=83) utilized a form of the USDA Household Food Security Survey Module. Studies commonly dichotomized the scale as “food insecurity” or “no food insecurity,” or utilized the USDA categories of food security (FS) (high, marginal, low, or very low).1 Of the 24 studies that utilized nationally representative data, the prevalence of food insecurity was as high as 25%.30 Non-validated measures tended to estimate a higher prevalence of food insecurity.

Mental Health Outcomes

The majority of studies evaluated the relationship between food insecurity and symptoms of depression, anxiety, externalizing and internalizing behaviors (directing problematic energy outward and towards oneself, respectively), hyperactivity, and stress.133,131,132 Additional studies evaluated the relationship between food insecurity and aggression, substance use, eating disorders, suicidality, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Qualitative analysis for all mental health outcomes is presented in Supplemental Table 2.

Depression

Seventy-four studies assessed food insecurity with symptoms of depression (62 parent studies, 14 child studies). Depression was defined using 21 unique measures. There was a statistically significant association between food insecurity and depressive symptoms in 59 parent and 10 child studies. For parents, depressive symptoms and food insecurity were associated in urban31,83 and rural populations.39,40,48,52,57,74,103 The connection between food insecurity and depressive symptoms persisted in mothers of older children,57,127 younger children,57,59,80,98,99,122,127,134,135 and pregnant women.62,109,110

For children, significant correlations were seen between food insecurity and depression among children 2-17 years old. Notably, the studies with the greatest strength of evidence (large sample size combined with low risk for bias and low risk for confounding) also demonstrated a statistically significant association between food insecurity and depressive symptoms in children.92,121,129 One study reported a stronger correlation between food insecurity and symptoms of depression in younger children than older children.117 Food insecurity was associated with increased odds of suicide attempt in a nationally representative group of 15-year-olds and a group of Hispanic teens.60,136 Longitudinal studies demonstrated that food insecurity at age five years was associated with depressive symptoms throughout childhood134 and at age 15 years.63 Depression in adolescence was also strongly correlated with food insecurity in adulthood,120 and conversely, adults with depression were more likely to have experienced childhood food insecurity compared to their non-depressed counterparts.45 Three studies failed to demonstrate a statistically significant association between food insecurity and depressive symptoms in children. These studies included a nationally representative sample of 15-16-year-olds29 and a sample of Hispanic youth.102

Anxiety

Seventeen studies assessed food insecurity with symptoms of anxiety (eight parent, ten child studies). Anxiety was defined using 13 unique measures, most of which were validated. Food insecurity was significantly associated with anxiety symptoms in seven parent studies. Food insecurity in a child in the home was the most consistent and impactful predictor of parental anxiety, when compared to household- and parent-level food insecurity.32,33

Food insecurity was associated with anxiety symptoms in six child studies. Of the studies with the greatest strength of evidence, Hatem et al. demonstrated that food insecurity at five years of life is associated with increased symptoms of anxiety at age 15 years63 and McLaughlin et al. (2012) found significantly increased odds of anxiety symptoms in children with FI.92 Three of the four studies that failed to demonstrate a statistically significant interaction between food insecurity and anxiety, including one study with high strength of evidence, interviewed majority Hispanic children8,102,107. Both marginal food security and risk of hunger were associated with increased anxiety,86,134 and more intense food insecurity correlated with more intense symptoms of anxiety in children.127 Longitudinal data revealed that childhood food insecurity impacts future anxiety.63,111,137

Externalizing Behaviors

Twenty-one studies evaluated food insecurity with externalizing behaviors in children. Four unique measures defined externalizing behaviors. Sixteen studies found a statistically significant relationship between food insecurity and externalizing behaviors. Of the two studies in this category with the highest strength of evidence, one found that transitions into and out of food insecurity were associated with increased externalizing behaviors and one did not find a statistically significant association between food insecurity and externalizing behaviors.55,73

Internalizing Behaviors

Thirteen studies assessed food insecurity and internalizing behaviors in children, and most, including those with the strongest strength of evidence, found a statistically significant association between these variables (n=10). All studies without statistically significant associations between food insecurity and internalizing (n=3) surveyed majority non-Hispanic White populations, and two reported an average child age of 6-7 years old.55,57,58

Hyperactivity

Twelve studies assessed food insecurity with hyperactivity in children. Nine studies found a statistically significant correlation between food insecurity and hyperactivity. The majority of children surveyed were younger than 10 years old.

Stress

Twelve studies assessed stress with food insecurity in parents. Five parent studies found a statistically significant relationship between food insecurity and stress.

Risk of Bias in Studies

Sixty-nine studies were low-risk for bias and 57 were low-risk for confounding (Table 3). Lack of adjusted analysis was the most common reason for confounding. Precision of studies varied greatly as sample sizes ranged from 2990 to 36,145.44

Table 3.

Risk of Bias and Confounding for the studies included in qualitative analysis

| Study ID | Risk of Bias | Risk of Confounding |

|---|---|---|

| Adynski 2019 27 | Medium | Low |

| Ajrouch 2010 28 | Low | Low |

| Alaimo 2002 29 | Low | Low |

| Ashiabi 2007 30 | Low | Low |

| Austin 2017 31 | Low | Medium |

| Becker 2017 32 | Medium | High |

| Becker 2019 33 | Medium | High |

| Bergmans 2018 34 | Low | High |

| Bernard 2018 35 | Low | High |

| Black 2012 36 | Low | High |

| Braveman 2018 37 | Medium | High |

| Bronte-Tinkew 2007 38 | Medium | Low |

| Browder 2012 39 | Medium | Medium |

| Bulock 2014 40 | Low | High |

| Burke 2016 41 | Low | Low |

| Casey 2004 42 | Low | Low |

| Chilton 2014 43 | High | High |

| Coffino 2020 44 | Medium | Low |

| Darling 2017 45 | Low | High |

| Dennison 2019 46 | Low | Medium |

| Distel 2019 47 | Medium | High |

| Doudna 2015 48 | Low | Low |

| Eiden 2014 49 | Low | Low |

| Ettekal 2019 50 | Low | Low |

| Fernández 2018 51 | Low | Low |

| Frazer 2011 52 | Low | Low |

| Garg 2015 53 | Low | Low |

| Gee 2018 54 | Low | High |

| Gee 2019 55 | Low | Low |

| Gill 2018 56 | Low | High |

| Greder 2017 57 | Low | Low |

| Grineski 2018 58 | Low | Medium |

| Guerrero 2020 59 | Medium | Low |

| Hall 2018 60 | Low | Medium |

| Hanson 2012 61 | Medium | Medium |

| Harrison 2008 62 | Low | High |

| Hatem 2020 63 | Low | Low |

| Heflin 2005 65 | Low | Low |

| Heflin 2008 66 | Low | Low |

| Heflin 2009 64 | Low | Low |

| Helton 2019 67 | Low | Low |

| Hernandez 2014 68 | Medium | Low |

| Himmelgreen 1998 69 | High | High |

| Horodynski 2018 70 | Low | High |

| Howells 2020 71 | Medium | Low |

| Hromi-Fiedler 2011 72 | Low | Low |

| Huang 2016 73 | Low | Low |

| Huddleston-Casas 2009 74 | Low | Medium |

| Jacknowitz 2015 75 | Medium | Medium |

| Jackson 2017 76 | Medium | Medium |

| Jackson 2017 77 | Medium | Low |

| Johnson 2018 78 | Low | Medium |

| Johnson 2018 79 | Medium | Low |

| Kim 2012 81 | Medium | Medium |

| Kimbro 2015 82 | Low | Low |

| King 2017 83 | Medium | Low |

| King 2018 84 | Medium | Low |

| Kleinman 1998 86 | Low | High |

| Kleinman 2002 85 | Low | High |

| Koury 2020 80 | Low | Low |

| Laraia 2006 89 | Low | Low |

| Laraia 2009 88 | Low | Low |

| Laraia 2015 87 | Low | Low |

| Lent 2009 90 | Medium | High |

| Letiecq 2019 91 | Low | Low |

| McLaughlin 2012 92 | Low | Low |

| Mersky 2017 93 | Low | Medium |

| Munger 2016 94 | Low | Low |

| Murphy 1998 95 | Medium | Low |

| Nagata 2019 8 | Medium | Low |

| Nelson 2016 96 | Low | Low |

| Niemeier 2019 97 | Low | Medium |

| Noonan 2016 98 | Medium | Low |

| Phojanakong 2020 99 | Low | Low |

| Poll 2020 100 | Medium | High |

| Poole-Di Salvo 2016 101 | Low | Low |

| Potochnick 2019 102 | Low | Low |

| Pulgar 2016 103 | Low | Low |

| Raiford 2014 104 | Low | High |

| Richards 2020 105 | Medium | Low |

| Rodriguez-JenKins 2014 106 | Medium | Medium |

| Rongstad 2018 107 | Medium | Medium |

| Rose-Jacobs 2008 108 | Low | High |

| Rose-Jacobs 2019 109 | Medium | Medium |

| Rose-Jacobs 2019 110 | Low | High |

| Rosenthal 2015 111 | Medium | Medium |

| Salas-Wright 2020 112 | Low | Medium |

| Sidebottom 2014 114 | Low | Medium |

| Siefert 2001 116 | Low | Low |

| Siefert 2007 115 | Low | Medium |

| Slack 2005 117 | Low | Low |

| Slopen 2010 118 | Medium | Medium |

| Sun 2016 113 | Medium | Low |

| Ten Haagen 2014 119 | High | Medium |

| Testa 2020 120 | Medium | Medium |

| Thomas 2019 121 | Low | Low |

| Trapp 2015 122 | Low | High |

| Tseng 2017 123 | Low | Low |

| Vaughn 2016 124 | Low | Medium |

| Ward 2019 126 | Medium | Low |

| Weinreb 2002 127 | Medium | Low |

| West 2019 128 | Low | Medium |

| Whitaker 2006 129 | Low | Low |

| Whitsett 2019 130 | Low | Low |

| Willis 2016 131 | Medium | High |

| Wu 2018 125 | Low | High |

| Zaslow 2009 132 | Medium | Low |

| Zekeri 2019 133 | Low | Medium |

Risk of Bias based on Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality RTI Item Bank, items 1, 3, 7, 8, 9, and 11. Bias by total score: Score 0 = “Low-risk”; 1 = “Medium-risk”; 2+ or a Fatal Flaw is present = “High-risk”. Risk of Confounding based on Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality RTI Item Bank, items 6, 12, and 13. Confounding by total score: Score 0 = “Low-risk”; 1 = “Medium-risk”; 2+ = “High-risk”.24

DISCUSSION

This systematic review revealed that food insecurity is associated with a variety of mental health outcomes in both parents and children. A majority of studies demonstrated a statistically significant relationship between food insecurity and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress in parents. In children, food insecurity had a statistically significant association with symptoms of depression, externalizing behaviors, internalizing behaviors, and hyperactivity in a majority of studies.

Depression

Our study demonstrated that food insecurity and symptoms of depression are intimately connected. This association persisted through various races, ethnicities, education levels, and geographic locations, but certain demographic groups were more affected than others. Food insecurity was associated with more than double the odds of depression for non-Hispanic Black mothers28,42,115,133 and with double or nearly double the odds of depression in Hispanic mothers,8,72,91 while the association was weaker for majority non-Hispanic White populations. It is well known that non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic families are impacted by food insecurity at greater rates than non-Hispanic White families.138 Our review also reports that among families with food insecurity, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic families are impacted by poor mental health at a greater rate. These findings were also reported by Dush (2019) when reviewing adolescent food insecurity and behaviors.139 Discrimination and structural racism are gaining recognition as significant contributors to racial disparity in health outcomes and likely contribute to our results.140 Differential rates of unemployment, incarceration, disability, and poverty among racial groups all contribute to the disparate rates of food insecurity.140 Racial/ethnic discrimination predicts both emergence of food insecurity and depression, and the synergistic effect may explain why racial/ethnic minority families with food insecurity have worse mental health outcomes.141

For children, there was a striking connection between food insecurity and suicidality. Two studies revealed that food insecurity was associated with more than double the odds that a youth will attempt suicide. One study in our review surveyed a sample of Hispanic teens and found that food insecurity was related to increased odds of a suicide attempt more for boys than girls.60 To our knowledge, this is the first review to collate studies associating suicidality with food insecurity in children. The rate of suicide attempts continues to rise, and the rate for Hispanic boys is increasing far more rapidly than that of the general population.142 It is critical that healthcare providers screen for suicidality in at-risk populations, including those experiencing food insecurity.

Food insecurity also exhibited a dose-dependent relationship with mental health outcomes. Child food insecurity is considered the most severe form of food insecurity because parents typically attempt to shield their children from the effects of food insecurity.2 Child food insecurity was associated with more severe depression in parents than parent- or household-level FI.33,84 Marginal food security and low food security were associated with symptoms of depression, but to a lesser degree than food insecurity and very low food security, respectively.56,105 Similarly, the duration and continuity of food insecurity appears to impact psychologic outcomes. Persistent food insecurity was associated with increased odds of depression significantly more than discontinuous food insecurity, while those with discontinuous food insecurity did not have significantly different depression than those who never had food insecurity.61 Recurrent food insecurity, compared to one episode of food insecurity, had a stronger association with depression for parents.55 This review, therefore, confirms that the intensity and frequency of food insecurity impacts mental health outcomes. These factors must be evaluated for a complete understanding of a family’s risk for mental health disorders.

Food insecurity and depression have a positive reinforcing relationship: food insecurity was related to concurrent depression and future depression, and depression was associated with future food insecurity. Several studies demonstrated that parents and children with symptoms of depression are more likely to maintain food insecurity, or fall into food insecurity, compared to acquire food security.79,94,143 There are various suggested mechanisms for this cyclical relationship. Food insecurity and malnutrition may heighten biological responses to emotions such as stress.144 A lack of macronutrient diversity can also impact the substrates available to construct neurotransmitters critical for regulating mood.12,13 Similarly, poor iron intake due to food insecurity may alter brain development in children and have lasting effects on neuropsychiatric regulation.145 Iron deficiency anemia is also independently associated with depression and may connect food insecurity with maternal depression.146 Depression also limits employment opportunities, which may contribute to the development or persistence of food insecurity.143 It is likely that both biological and psychosocial mechanisms contribute to the connection between food insecurity and depression.

It is reasonable to wonder if relieving food insecurity will also relieve negative mental health effects. Jacknowitz et al. (2015) found that transitions into and out of food insecurity and depression were correlated.75 Still, children who experience food insecurity are more likely to suffer from mental health problems later in life, regardless of their food security status in adulthood.45 More research must be dedicated to understanding the effect of treating food insecurity on changes in mental health.

Anxiety

Anxiety is less clearly associated with food insecurity. Fewer studies measured symptoms of anxiety, and while most parent studies found a statistically significant relationship between food insecurity and anxiety, this was only true in a little more than half of child studies. These results are in contrast to those of Myers (2020), who reports that food insecurity is positively correlated with anxiety in adult and adolescent populations across the globe.147 The relationship between food insecurity and anxiety symptoms may depend on the race/ethnicity of the population. Our review revealed that anxiety and food insecurity were significantly correlated in non-Hispanic White populations, but the relationship was less consistent in majority Hispanic populations.8,102 This may be due to under-diagnosis of anxiety in Hispanic populations since standardized measures inadequately capture variances in cultural comprehension of anxiety.148 Statistical significance did not depend on the definition or prevalence of anxiety in a given study. The relationship between food insecurity and symptoms of anxiety in children may be less consistent than that of parents due to shielding and because child anxiety is better assessed through externalizing/internalizing behaviors.149

Externalizing and Internalizing Behaviors, Hyperactivity

Age, duration and intensity of food insecurity, and sex influenced the relationship between food insecurity and externalizing and internalizing behaviors in children. In several studies, food insecurity was associated with increased odds of externalizing behaviors in toddlers and preschool-aged children, but not in school-aged children.49,57,59,78 Nonetheless, Fernandez et al. (2018) found that food insecurity influenced rule-breaking behaviors in 9-year-olds and food insecurity was associated with hyperactivity in children less than ten years old.51 A connection between food insecurity and internalizing behaviors was found in both preschool- and school-aged children.117,127 The differing prevalence of externalizing and internalizing problem behaviors in these age groups at baseline may contribute to this effect.149,150 Our findings corroborate those of Shankar et al. (2017), who reported that food insecurity was associated with poor child behavior and academic performance.151 We also found that persistent food insecurity affected externalizing and internalizing behaviors more than transient food insecurity.58,82,118 Similar to other mental health outcomes, severe food insecurity had a stronger association with behavioral problems, including hyperactivity, than moderate food insecurity.84,95,134

The relationship between food insecurity and internalizing behaviors may be related to poor diet quality. O’Neil et al. (2014) found in their review that poor diet quality was associated with worse internalizing disorders in children, although many included studies did not account for activity level or socioeconomic status, which may also contribute to internalizing behaviors.152 Recognizing the impact of food insecurity on child behavior is imperative because mental health disorders are more likely to present as behavioral changes in younger populations. Additionally, mental health problems are more likely to be unrecognized in children of lower socioeconomic status.153 Taken together, healthcare workers screening for food insecurity should subsequently consider adding mental health and behavioral screens for children with household food insecurity.

Stress

Food insecurity is a risk factor for chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. Research suggests this is because food insecurity acts as a chronic stressor, increasing inflammation in the body.154 Interestingly, less than half of stress studies in our review supported a significant association between stress and food insecurity. A different mechanism, therefore, may connect food insecurity and chronic disease. Notably, the studies included in this review assessed psychological stress rather than biological measures of stress, such as cortisol. Nearly all studies surveyed only low-income families, suggesting that income may moderate the relationship. In contrast to our review, Pourmetabbed et al (2020) found that food insecurity increased stress in men and women in North America.155 It is notable that the aforementioned review assessed studies of all adult participants and not exclusively parents, reflecting that parents indeed may experience food insecurity differentially from the general population.

Limitations

All studies in this review were observational, limiting our ability to assign causality between food insecurity and mental health outcomes. Food insecurity and mental health parameters were typically collected from the same individual, leading to shared method variance. Additionally, food insecurity and all mental health outcomes were defined using various validated and non-validated measures, and were assessed in a myriad of sub-populations, making it difficult to compare results and draw overarching conclusions. While we intended to compare the impact of food insecurity on mental health in children and in parents, few studies assessed the same mental health outcome in both parents and children, which limited our ability to understand how food insecurity in a home differentially impacts family members. The cumulative evidence in this review is also limited by potential publication bias, the risk of selective reporting within studies, and missing confidence intervals from some included studies.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings of this systematic review highlight the inexplicable link between food insecurity and mental health in parents and children. There is a need for policy and public health interventions that address both issues.156 Both populations are especially vulnerable to the impact of food insecurity given parents’ responsibility of caring for dependents and children’s developing behavior and thought patterns. Policy or public health approaches could include increasing the benefit amount or reducing the administrative burden for accessing nutrition subsidies, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or the Special Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). Both SNAP and WIC reduce food insecurity, and there is a growing body of evidence showing these programs could improve health outcomes.157,158 Another approach could be providing income subsidies or universal basic income, such as through the Child Tax Credit. There is increasing evidence that providing basic income may improve health, particularly mental health.159 Given the rise in both food insecurity and mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is more important now than ever to develop public health and policy interventions that identify and address food insecurity and mental health sequelae.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 1: Complete Search Strategy for PubMed Database

Supplemental Table 2: Relationship between food insecurity and mental health outcomes with studies categorized by the mental health outcome assessed

What this Systematic Review Adds.

This review consolidates existing literature examining the associations of food insecurity with mental health problems

Food insecurity is associated with depression and anxiety in parents and with depression, externalizing/internalizing behaviors, and hyperactivity in children

Greater food insecurity duration and intensity are associated with worse mental health outcomes

How to Use this Systematic Review.

To identify where further research is needed to examine if mitigating food insecurity improves mental health outcomes

To serve as a reference when developing clinical screening and intervention programs for food insecurity and mental health problems

To serve as a reference when developing public health and policy interventions that identify and address food insecurity and mental health sequelae

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank Akhila “Soni” Boyina for contributing to the Title and Abstract Review and Mark McKone and Carpenter Library for their assistance generating the search strategy and collecting studies. Dr. Brown was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant 1K23HD099249). Dr. Palakshappa is supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (K23HL146902). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funding:

Dr. Brown was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant K23HD099249). Dr. Palakshappa is supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (K23HL146902). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funding source had no role in the study design; collection, analysis or interpretation of data; writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication

Footnotes

Declarations of Interest: none

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Definitions of Food Security. Last updated September 2021. <https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/definitions-of-food-security/>.

- 2.U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Key Statistics & Graphics. Last updated September 2021. <https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/key-statistics-graphics/>.

- 3.Chi DL, Masterson EE, Carle AC, Mancl LA, Coldwell SE. Socioeconomic status, food security, and dental caries in US children: mediation analyses of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007-2008. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(5):860–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook JT, Frank DA, Levenson SM, et al. Child food insecurity increases risks posed by household food insecurity to young children's health. J Nutr. 2006;136(4):1073–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eicher-Miller HA, Mason AC, Weaver CM, McCabe GP, Boushey CJ. Food insecurity is associated with iron deficiency anemia in US adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(5):1358–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirkpatrick SI, McIntyre L, Potestio ML. Child hunger and long-term adverse consequences for health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(8):754–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagata JM, Palar K, Gooding HC, Garber AK, Bibbins-Domingo K, Weiser SD. Food Insecurity and Chronic Disease in US Young Adults: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(12):2756–2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagata JM, Gomberg S, Hagan MJ, Heyman MB, Wojcicki JM. Food insecurity is associated with maternal depression and child pervasive developmental symptoms in low-income Latino households. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2019;14(4):526–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polsky JY, Gilmour H. Food insecurity and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Rep. 2020;31(12):3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maynard M, Andrade L, Packull-McCormick S, Perlman CM, Leos-Toro C, Kirkpatrick SI. Food Insecurity and Mental Health among Females in High-Income Countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raskind IG, Haardörfer R, Berg CJ. Food insecurity, psychosocial health and academic performance among college and university students in Georgia, USA. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(3):476–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mofleh D, Ranjit N, Chuang RJ, Cox JN, Anthony C, Sharma SV. Association Between Food Insecurity and Diet Quality Among Early Care and Education Providers in the Pennsylvania Head Start Program. Prev Chronic Dis. 2021;18:E60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanson KL, Connor LM. Food insecurity and dietary quality in US adults and children: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100(2):684–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma A, Sharma SD, Sharma M. Mental health promotion: a narrative review of emerging trends. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2017;30(5):339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wortzel JR, Turner BE, Weeks BT, et al. Trends in mental health clinical research: Characterizing the ClinicalTrials.gov registry from 2007–2018. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(6):e0233996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCarthy M Mental disorders common among US children, CDC says. BMJ. 2013;346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark C, Rodgers B, Caldwell T, Power C, Stansfeld S. Childhood and adulthood psychological ill health as predictors of midlife affective and anxiety disorders: the 1958 British Birth Cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(6):668–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eckshtain D, Marchette LK, Schleider J, Weisz JR. Parental Depressive Symptoms as a Predictor of Outcome in the Treatment of Child Depression. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2018;46(4):825–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Priel A, Djalovski A, Zagoory-Sharon O, Feldman R. Maternal depression impacts child psychopathology across the first decade of life: Oxytocin and synchrony as markers of resilience. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(1):30–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanson KL, Connor LM. Food insecurity and dietary quality in US adults and children: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100(2):684–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ng SW, Hollingsworth BA, Busey EA, Wandell JL, Miles DR, Poti JM. Federal Nutrition Program Revisions Impact Low-income Households' Food Purchases. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(3):403–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Odoms-Young AM, Kong A, Schiffer LA, et al. Evaluating the initial impact of the revised Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) food packages on dietary intake and home food availability in African-American and Hispanic families. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(1):83–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tester JM, Leung CW, Crawford PB. Revised WIC Food Package and Children's Diet Quality. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews. National Institute for Health Research. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/. Accessed2021. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Covidence Systematic Review Software [computer program]. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Viswanathan M, Berkman ND, Dryden DM, Hartling L. Assessing Risk of Bias and Confounding in Observational Studies of Interventions or Exposures: Further Development of the RTI Item Bank. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adynski H, Zimmer C, Thorp J Jr., Santos HP Jr. Predictors of psychological distress in low-income mothers over the first postpartum year. Res Nurs Health. 2019;42(3):205–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ajrouch KJ, Reisine S, Lim S, Sohn W, Ismail A. Situational stressors among African-American women living in low-income urban areas: the role of social support. Women Health. 2010;50(2):159–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA. Family food insufficiency, but not low family income, is positively associated with dysthymia and suicide symptoms in adolescents. J Nutr. 2002;132(4):719–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ashiabi GS, O'Neal KK. Children's health status: examining the associations among income poverty, material hardship, and parental factors. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(9):e940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Austin AE, Smith MV. Examining Material Hardship in Mothers: Associations of Diaper Need and Food Insufficiency with Maternal Depressive Symptoms. Health Equity. 2017;1(1):127–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Becker CB, Middlemass K, Taylor B, Johnson C, Gomez F. Food insecurity and eating disorder pathology. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2017;50(9):1031–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Becker CB, Middlemass KM, Gomez F, Martinez-Abrego A. Eating disorder pathology among individuals living with food insecurity: A replication study. Clinical Psychological Science. 2019;7(5):1144–1158. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bergmans RS, Berger LM, Palta M, Robert SA, Ehrenthal DB, Malecki K. Participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and maternal depressive symptoms: Moderation by program perception. Soc Sci Med. 2018;197:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bernard R, Hammarlund R, Bouquet M, et al. Parent and Child Reports of Food Insecurity and Mental Health: Divergent Perspectives. Ochsner J. 2018;18(4):318–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Black MM, Quigg AM, Cook J, et al. WIC participation and attenuation of stress-related child health risks of household food insecurity and caregiver depressive symptoms. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2012;166(5):444–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braveman P, Heck K, Egerter S, Rinki C, Marchi K, Curtis M. Economic Hardship in Childhood: A Neglected Issue in ACE Studies? Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(3):308–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bronte-Tinkew J, Zaslow M, Capps R, Horowitz A, McNamara M. Food insecurity works through depression, parenting, and infant feeding to influence overweight and health in toddlers. J Nutr. 2007;137(9):2160–2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Browder DE. Latino mothers in rural America: A mixed methods assessment of maternal depression. 2012;72:3524–3524. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bulock LA. Theorizing about resilience and its relationship to depression among rural low-income mothers:Mixed methods approaches. 2014;75. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burke MP, Martini LH, Çayır E, Hartline-Grafton HL, Meade RL. Severity of Household Food Insecurity Is Positively Associated with Mental Disorders among Children and Adolescents in the United States. J Nutr. 2016;146(10):2019–2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Casey P, Goolsby S, Berkowitz C, et al. Maternal depression, changing public assistance, food security, and child health status. Pediatrics. 2004;113(2):298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chilton MM, Rabinowich JR, Woolf NH. Very low food security in the USA is linked with exposure to violence. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(1):73–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coffino JA, Grilo CM, Udo T. Childhood food neglect and adverse experiences associated with DSM-5 eating disorders in U.S. National Sample. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2020;127:75–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Darling KE, Fahrenkamp AJ, Wilson SM, D'Auria AL, Sato AF. Physical and mental health outcomes associated with prior food insecurity among young adults. J Health Psychol. 2017;22(5):572–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dennison MJ, Rosen ML, Sambrook KA, Jenness JL, Sheridan MA, McLaughlin KA. Differential Associations of Distinct Forms of Childhood Adversity With Neurobehavioral Measures of Reward Processing: A Developmental Pathway to Depression. Child Dev. 2019;90(1):e96–e113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Distel LML, Egbert AH, Bohnert AM, Santiago CD. Chronic Stress and Food Insecurity: Examining Key Environmental Family Factors Related to Body Mass Index Among Low-Income Mexican-Origin Youth. Fam Community Health. 2019;42(3):213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doudna KD, Reina AS, Greder KA. Longitudinal associations among food insecurity, depressive symptoms, and parenting. Journal of Rural Mental Health. 2015;39(3–4):178–187. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eiden RD, Coles CD, Schuetze P, Colder CR. Externalizing behavior problems among polydrug cocaine-exposed children: Indirect pathways via maternal harshness and self-regulation in early childhood. Psychol Addict Behav. 2014;28(1):139–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ettekal I, Eiden RD, Nickerson AB, Schuetze P. Comparing alternative methods of measuring cumulative risk based on multiple risk indicators: Are there differential effects on children's externalizing problems? PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0219134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fernández CR, Yomogida M, Aratani Y, Hernández D. Dual Food and Energy Hardship and Associated Child Behavior Problems. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(8):889–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Frazer MS. Poverty measurement and depression symptomology in the context of welfare reform. 2011;72:1460–1460. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, Cook J, Cordella N. Influence of maternal depression on household food insecurity for low-income families. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(3):305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gee KA. Growing Up With A Food Insecure Adult: The Cognitive Consequences of Recurrent Versus Transitory Food Insecurity Across the Early Elementary Years. Journal of Family Issues. 2018;39(8):2437–2460. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gee KA, Asim M. Parenting While Food Insecure: Links Between Adult Food Insecurity, Parenting Aggravation, and Children's Behaviors. Journal of Family Issues. 2019;40(11):1462–1485. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gill M, Koleilat M, Whaley SE. The Impact of Food Insecurity on the Home Emotional Environment Among Low-Income Mothers of Young Children. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(8):1146–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Greder KA, Peng C, Doudna KD, Sarver SL. Role of family stressors on rural low-income children’s behaviors. Child & Youth Care Forum. 2017;46(5):703–720. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grineski SE, Morales DX, Collins TW, Rubio R. Transitional Dynamics of Household Food Insecurity Impact Children's Developmental Outcomes. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2018;39(9):715–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guerrero N, Wagner KM, Gangnon R, et al. Food Insecurity and Housing Instability Partially Mediate the Association Between Maternal Depression and Child Problem Behavior. J Prim Prev. 2020;41(3):245–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hall M, Fullerton L, FitzGerald C, Green D. Suicide Risk and Resiliency Factors Among Hispanic Teens in New Mexico: Schools Can Make a Difference. J Sch Health. 2018;88(3):227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hanson KL, Olson CM. Chronic health conditions and depressive symptoms strongly predict persistent food insecurity among rural low-income families. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(3):1174–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harrison PA, Sidebottom AC. Systematic prenatal screening for psychosocial risks. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(1):258–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hatem C, Lee CY, Zhao X, Reesor-Oyer L, Lopez T, Hernandez DC. Food insecurity and housing instability during early childhood as predictors of adolescent mental health. J Fam Psychol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heflin CM, Iceland J. Poverty, Material Hardship, and Depression. Social Science Quarterly. 2009;90(5):1051–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heflin CM, Siefert K, Williams DR. Food insufficiency and women's mental health: findings from a 3-year panel of welfare recipients. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(9):1971–1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Heflin CM, Ziliak JP. Food insufficiency, food stamp participation, and mental health. Social Science Quarterly. 2008;89(3):706–727. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Helton JJ, Jackson DB, Boutwell BB, Vaughn MG. Household Food Insecurity and Parent-to-Child Aggression. Child Maltreat. 2019;24(2):213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hernandez DC, Marshall A, Mineo C. Maternal depression mediates the association between intimate partner violence and food insecurity. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(1):29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Himmelgreen DA, Pérez-Escamilla R, Segura-Millán S, Romero-Daza N, Tanasescu M, Singer M. A comparison of the nutritional status and food security of drug-using and non-drug-using Hispanic women in Hartford, Connecticut. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1998;107(3):351–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Horodynski MA, Brophy-Herb HE, Martoccio TL, et al. Familial psychosocial risk classes and preschooler body mass index: The moderating effect of caregiver feeding style. Appetite. 2018;123:216–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Howells ME, Dancause K, Pond R, Rivera L, Simmons D, Alston BD. Maternal marital status predicts self-reported stress among pregnant women following hurricane Florence. American journal of human biology : the official journal of the Human Biology Council. 2020:e23427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hromi-Fiedler A, Bermúdez-Millán A, Segura-Pérez S, Pérez-Escamilla R. Household food insecurity is associated with depressive symptoms among low-income pregnant Latinas. Matern Child Nutr. 2011;7(4):421–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang J, Vaughn MG. Household food insecurity and children’s behaviour problems: New evidence from a trajectories-based study. British Journal of Social Work. 2016;46(4):993–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Huddleston-Casas C, Charnigo R, Simmons LA. Food insecurity and maternal depression in rural, low-income families: a longitudinal investigation. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(8):1133–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jacknowitz A, Morrissey T, Brannegan A. Food insecurity across the first five years: Triggers of onset and exit. Children and Youth Services Review. 2015;53:24–33. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jackson DB, Vaughn MG. Household food insecurity during childhood and adolescent misconduct. Prev Med. 2017;96:113–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jackson DB, Vaughn MG. Parental History of Disruptive Life Events and Household Food Insecurity. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2017;49(7):554-+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Johnson AD, Markowitz AJ. Associations Between Household Food Insecurity in Early Childhood and Children's Kindergarten Skills. Child Dev. 2018;89(2):e1–e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Johnson AD, Markowitz AJ. Food Insecurity and Family Well-Being Outcomes among Households with Young Children. Journal of Pediatrics. 2018;196:275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Koury AJ, Dynia J, Dore R, et al. Food Insecurity and Depression among Economically Disadvantaged Mothers: Does Maternal Efficacy Matter? Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kim HG, Geppert J, Quan T, Bracha Y, Lupo V, Cutts DB. Screening for postpartum depression among low-income mothers using an interactive voice response system. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(4):921–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kimbro RT, Denney JT. Transitions Into Food Insecurity Associated With Behavioral Problems And Worse Overall Health Among Children. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(11):1949–1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.King C Soft drinks consumption and child behaviour problems: the role of food insecurity and sleep patterns. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(2):266–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.King C Food insecurity and child behavior problems in fragile families. Econ Hum Biol. 2018;28:14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kleinman RE, Hall S, Green H, et al. Diet, breakfast, and academic performance in children. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism. 2002;46(SUPPL. 1):24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kleinman RE, Murphy JM, Little M, et al. Hunger in children in the United States: potential behavioral and emotional correlates. Pediatrics. 1998;101(1):E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Laraia B, Vinikoor-Imler LC, Siega-Riz AM. Food insecurity during pregnancy leads to stress, disordered eating, and greater postpartum weight among overweight women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23(6):1303–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Laraia BA, Borja JB, Bentley ME. Grandmothers, fathers, and depressive symptoms are associated with food insecurity among low-income first-time African-American mothers in North Carolina. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(6):1042–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Laraia BA, Siega-Riz AM, Gundersen C, Dole N. Psychosocial factors and socioeconomic indicators are associated with household food insecurity among pregnant women. J Nutr. 2006;136(1):177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lent MD, Petrovic LE, Swanson JA, Olson CM. Maternal mental health and the persistence of food insecurity in poor rural families. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(3):645–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Letiecq BL, Mehta S, Vesely CK, Goodman RD, Marquez M, Moron LP. Central American Immigrant Mothers' Mental Health in the Context of Illegality: Structural Stress, Parental Concern, and Trauma. Fam Community Health. 2019;42(4):271–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]