Abstract

More than 60 years ago, Eugene Kennedy and coworkers elucidated the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-based pathways of glycerolipid synthesis, including the synthesis of phospholipids and triacylglycerols (TGs). The reactions of the Kennedy pathway were identified by studying the conversion of lipid intermediates and the isolation of biochemical enzymatic activities, but the molecular basis for most of these reactions was unknown. With recent progress in the cell biology, biochemistry, and structural biology in this area, we have a much more mechanistic understanding of this pathway and its reactions. In this review, we provide an overview of molecular aspects of glycerolipid synthesis, focusing on recent insights into the synthesis of TGs. Further, we go beyond the Kennedy pathway to describe the mechanisms for storage of TG in cytosolic lipid droplets and discuss how overwhelming these pathways leads to ER stress and cellular toxicity, as seen in diseases linked to lipid overload and obesity.

Enzymes of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) synthesize nearly all major lipids in the cell, including sterols, sphingolipids, phospholipids, and neutral lipids. The lipid biosynthesis pathways are essential for cellular health by providing lipids for cellular membranes. For example, the synthesis of sterols and sphingolipids initiates in the ER, but eventually these lipids are highly enriched in the plasma membrane, where their properties help to ensure effective sealing of the cell from the external environment. Also, reactions of lipid synthesis and modification in the ER membrane allow cells to maintain a balance of saturated and unsaturated fatty acyl moieties to ensure proper fluidity of membranes for their functions in the cell. Lipid synthesis in the ER therefore is important to maintain membrane homeostasis. Lipids that accumulate excessively in the ER and disrupt this homeostasis are detoxified by converting them to neutral lipids, such as cholesterol esters (CEs) or triacylglycerols (TGs) that can be safely stored in phase-separated oils within organelles called lipid droplets (LDs). In this way, neutral lipids provide the major molecular storage form of lipids to be used to generate membranes according to need or as fuel to provide metabolic energy in cells and tissues.

Many of the pathways and reactions of lipid synthesis in the ER were identified in the mid-20th century. Thanks to the technological advances in radioisotope tracing and biochemical analysis of enzymatic activities, the reactions for making different cellular lipids were largely elucidated through elegant biochemistry. However, it was decades before molecular biology approaches allowed for the identification of the genes that encode the enzymes of lipid synthesis. Only with these breakthroughs could the mechanistic dissection of lipid synthesis and its organization in the cell begin.

In the current review, we focus on one aspect of ER lipid synthesis—that of glycerolipids. We briefly provide an overview of the pathway of glycerolipid synthesis, focusing on the pathways for synthesizing phospholipids and TG-neutral lipids. For phospholipids, we provide a broad overview and some perspective on key aspects of how this pathway is organized, referring the reader to other reviews on phospholipid synthesis for greater details (Vance 2015; Kwiatek et al. 2020). For TGs, we describe recent mechanistic advances in understanding their synthesis by enzymes in the ER. We also describe the current understanding of how TGs generated in the ER phase separate to form neutral lipid oil droplets, and we discuss new insights into the molecular machinery involved in LD formation.

GLYCEROLIPID SYNTHESIS AND THE ER

The major phospholipids, such as phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidylinositol (PI), and phosphatidylglycerol (PG), are products of two major pathways, the Kennedy pathway of de novo synthesis (for PC and PE) and the cytidine diphosphate-diacylglycerol (CDP-DAG) pathway, which gives rise primarily to PS, PI, and PG. The elucidation of these pathways was a remarkable feat, drawing on elegant biochemistry and radiolabel tracer studies performed by numerous investigators. The details of phospholipid biosynthesis are vast and can be found in many excellent textbooks and reviews, and we provide here an overview of some of the key aspects of the synthesis of these glycerolipids, focusing on the early steps of the glycerolipid synthesis pathway that occur in the ER and are involved in TG synthesis and LD formation. This pathway is shown biochemically in Figure 1 and in the context of the ER in Figure 2. The CDP-DAG pathway of phospholipid synthesis is shown only schematically.

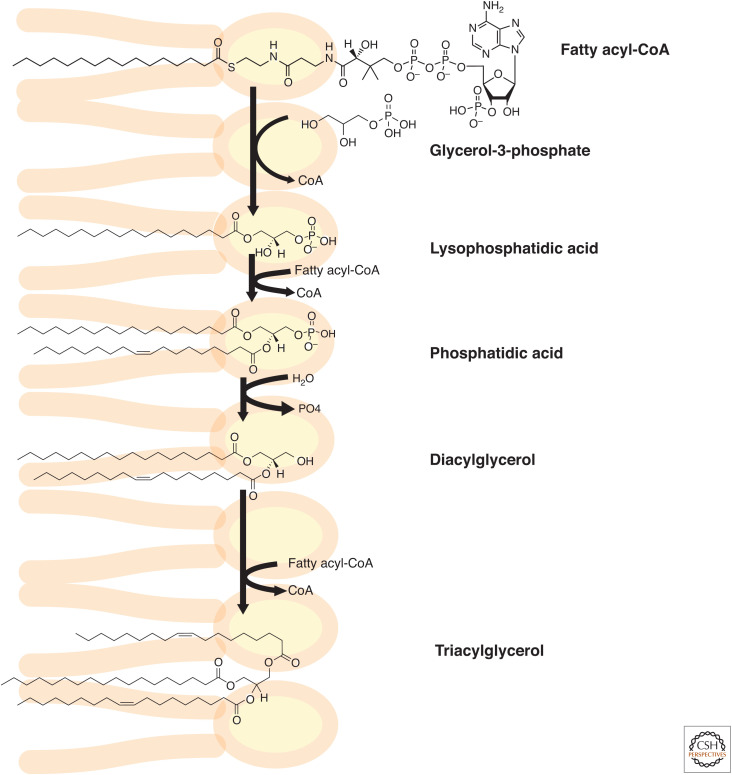

Figure 1.

Biochemistry of the early steps of the Kennedy pathway of glycerolipid synthesis. In the first steps of glycerolipid synthesis, fatty acyl-CoAs are sequentially added to a glycerol-3-phosphate backbone. The phosphate group is removed to form diacylglycerol. In the final step shown, triacylglycerols are formed from diacylglycerol and acyl-CoA substrates. Multiple enzymes catalyze each step in this pathway. See text for details.

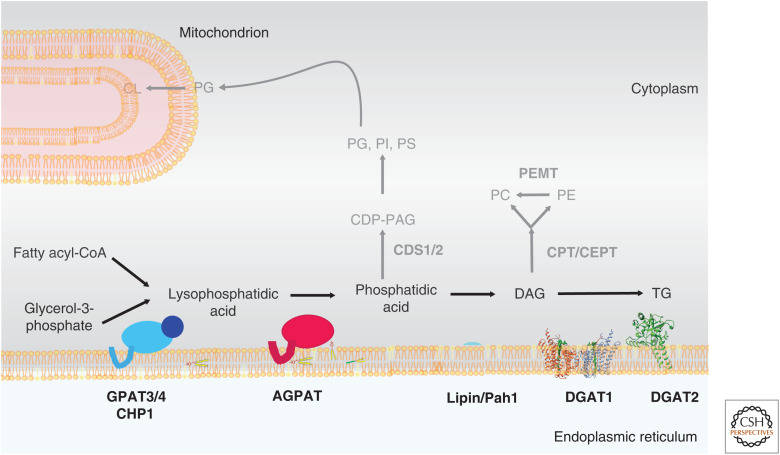

Figure 2.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-based Kennedy pathway of glycerolipid synthesis. An overview of the pathway of the early steps of glycerophospholipid synthesis in the ER is shown. Several structures that are available or predicted (lipin, DGAT1, and DGAT2) are shown at the ER membrane. Blue oval represents GPAT3 or GPAT4 with activator CHP-1 (dark blue oval); red oval, acylglycerol phosphate acyltransferase (AGPAT). Reactions of the CDP-DAG pathway and the last steps of the Kennedy pathway to synthesize phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) are shown schematically in gray. See text for details.

Phospholipids are polar glycerolipids that are synthesized primarily in the ER from fatty acids (FAs) and glycerol-3-phosphate substrates. FAs for glycerolipid synthesis arise from one of two sources. As one source, cells synthesize FAs de novo in the lipogenesis pathway regulated by transcription factors, such as SREBP1c and ChREBP (Yokoyama et al. 1993; Yamashita et al. 2001). Synthesis of FAs starts in the cytoplasm from acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA) and malonyl-CoA precursors, catalyzed by the large polypeptide fatty acid synthase (FASN in humans). This large protein encodes many different activities that sequentially add two carbon units to form an FA chain, such as palmitoyl-CoA, containing 16 carbons. In these reactions, acyl carrier protein and subsequently CoA serve as molecular handles that solubilize and enable the elongation of the FA chain.

Extracellular FAs are a second source of cellular FAs. These FAs enter the cell and must be conjugated to CoA via enzymatic reactions that require energy. This “activation” of exogenous FAs is carried out by acyl CoA synthetases (ACSLs), and there are numerous ACSL enzymes in mammals (Coleman 2019). In general, these are associated or integrated into different membranes, such as the ER for ACSL1 (Lewin et al. 2001), where they catalyze FA CoA formation from long-chain FAs in the membrane. ACSL3 localizes to the LD monolayer surface (Brasaemle et al. 2004). It appears that some ACSLs have specificity for saturated versus unsaturated FA substrates and, therefore, control of different types of FAs into the bioactive pool. For example, ACSL3 has a preference for saturated FAs, whereas ACSL4 prefers unsaturated FAs (Van Horn et al. 2005; Klett et al. 2017).

Once FAs are activated, they can enter the glycerolipid synthesis pathway and are first esterified to the sn-1 position of glycerol-3-phosphate by glycerol phosphate acyltransferase (GPAT) enzymes, which prefer saturated FAs as substrates (Vancura and Haldar 1994). Of the GPATs, GPAT3 and GPAT4 are localized primarily in the ER, where they are important particularly for esterification of exogenously derived FAs (Chen et al. 2008; Wilfling et al. 2013; Cooper et al. 2015). When cells have LDs, these GPATs can also relocalize to the surface of these organelles and appear to contribute to the local synthesis of TG at the LD surface (Wilfling et al. 2013). In contrast, GPAT1 is localized in the mitochondria and more closely coupled to esterification of FA synthesized by de novo lipogenesis (Wendel et al. 2013). How FAs derived from de novo lipogenesis access GPAT1 at the mitochondrial surface for this reaction, and how this might contribute to the cell biology of glycerolipid synthesis, are unknown.

The structures of GPAT enzyme remain to be elucidated but AlphaFold (alphafold.ebi.ac.uk) (Senior et al. 2020) predictions suggest that they act at membrane surfaces, such as the cytoplasmic side of the ER bilayer or LD monolayer, where they covalently join FA CoA in the membrane with soluble glycerol-3-phosphate. In mammals and some other species, the protein CHP-1 is required for full GPAT3/4 activity (Zhu et al. 2019) although its function in the reaction remains unclear.

GPAT activity is considered rate-limiting for glycerolipid synthesis in the ER and generates acyl glycerol phosphate, or lysophosphatidic acid, as its product. In this manner, GPAT enzymes act as “gate keepers” for incorporation of FAs into glycerolipids. The importance of this was demonstrated in studies that showed that lipotoxicity to the ER and associated cell death caused by large amounts of saturated FAs can be prevented by blocking access of saturated FAs into glycerolipids (Masuda et al. 2015; Zhu et al. 2019). Evidence suggests that overload of cells with saturated FAs leads to an accumulation of di-saturated species of glycerolipids that do not serve well as substrates for many reactions in the glycerolipid synthesis pathway and hence accumulate in membranes, such as the ER (Piccolis et al. 2019). This likely affects membrane fluidity and triggers ER stress pathways, eventually leading to cell death (Piccolis et al. 2019). By blocking GPAT activity in the ER, these effects and the lipotoxicity caused by excessive saturated FAs are prevented (Piccolis et al. 2019; Zhu et al. 2019).

Lysophosphatic acid generated by GPAT enzymes is subsequently acylated at the sn-2 position by acyl CoA:acylglycerol phosphate acyltransferases (AGPATs). These enzymes generally prefer to add an unsaturated FA moiety to the glycerol backbone (Ellingson et al. 1970; Agarwal et al. 2011; Prasad et al. 2011). Thus, the combined GPAT and AGPAT activities generate glycerolipids that most often have a saturated FA in the sn-1 position and an unsaturated FA in the sn-2 position, which is the most common configuration for most glycerolipids (e.g., 16:0, 18:1). Further remodeling of FA moieties can be carried out via the Lands’ cycle by exchanging FA chains of glycerophospholipids by phospholipase A2, which removes an FA in the sn-2 position, and reesterification by specific LPCAT/MBOAT enzymes (Valentine et al. 2020). Polyunsaturated FAs released by PLA2 are used by cyclooxygenases and lipoxygenases as substrates to generate bioactive lipids, such as prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and others (Wang et al. 2021).

Deficiency of AGPAT2 leads to a form of congenital generalized lipodystrophy (Agarwal et al. 2002). The mechanism for lipodystrophy is not totally clear, as it is likely not due to loss of fat synthesis alone. In fact, the loss of function of AGPAT2 paradoxically results in increased levels of its product, phosphatidic acid (PA), which has been suggested to interfere with the differentiation or function of adipocytes (Gale et al. 2006).

The product of AGPAT enzymes, PA can be channeled into the synthesis of specific phospholipids (e.g., PI, PS, and PG) via the CDP-DAG pathway, or can be converted to DAG via the actions of lipin (PA hydrolase) enzymes (Reue and Wang 2019; Dey et al. 2020). In the CDP-DAG pathway, CTP:phosphatidate cytidyltransferase (or CDP-DAG synthase, with two isoenzymes encoded by CDS1 and CDS2), “activates” the phosphate headgroup of PA (in a reaction involving a CTP nucleotide and releasing a pyrophosphate) at the ER membrane. Subsequently, this key intermediate is converted to PI, PS, or PG by the addition of inositol, serine, or glycerol-3-phosphate, respectively, in a reaction that releases CDP. PG then is transported from the ER to serve as a substrate for cardiolipin synthesis in mitochondria. How the flow of lipids between different membranes in this pathway occurs and is regulated is still not fully understood but is increasingly recognized to occur at membrane contact sites (Reinisch and Prinz 2021). In addition, a separate pathway generates a distinct pool of CDP-DAG in the mitochondrial inner membrane, through a reaction catalyzed by the peripheral membrane protein TAMM41 (Blunsom and Cockcroft 2020).

PA in the ER can also be converted to DAG and serve as a precursor for de novo synthesis of PC or PE via the Kennedy pathway. Alternatively, when levels of DAG and FA are in excess, DAG can be further acylated to form TG as described below. The conversion of PA to DAG is carried out by three lipin (PA hydrolase) enzymes in mammals (Reue and Wang 2019) and four PA hydrolases in yeast (Dey et al. 2020). The structure of the lipin enzyme from Tetrahymena shows an amino-terminal amphipathic domain that binds membranes, an immunoglobulin domain, and a carboxy-terminal catalytic domain that suggests the dephosphorylation of PA likely occurs at the cytosolic surface of the ER (Khayyo et al. 2020). Deficiency of lipin-1 in mice leads to a lipodystrophy syndrome in that species (Péterfy et al. 2001), and in humans is associated with the inflammatory diseases Majeed syndrome, rhabdomyolysis, neuropathy, lipodystrophy, and neonatal fatty liver in humans (Ferguson et al. 2005).

Other important glycerophospholipids in the ER include plasmalogens that are found at highest levels in tissues such as heart, brain, and myelin. In plasmalogens, an ether, rather than an ester, bond links the FA moiety to glycerol in the sn-1position. This pathway begins in the peroxisome, where dihydroxyacetone phosphate is acylated, with conversion of the bond in the sn-1 position to an ether bond. Eventually, the 1-O-alkyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycerophosphate product is transferred to the ER, where it enters into pathways that are similar to those of ester-based glycerolipids, including the synthesis of neutral lipids similar to TG, such as monoalkyl-diacylglycerol (MADAG) (Ma et al. 2017). Despite their prevalence, ether glycerolipids have been studied less than ester glycerolipids. However, plasmalogen defects have been linked or associated with a host of pathologies (Honsho and Fujiki 2017), and increased plasmalogen production in cells is important under hypoxic conditions (Jain et al. 2020). More investigation is needed into the functions and requirements of this class of glycerolipids generated in the ER.

TRIGLYCERIDE BIOSYNTHESIS

TGs were reported as components of fats in the early 1800s by the organic chemist Michel Chevreul, who used biochemical saponification techniques to show that they are composed of FAs and glycerine. (Chevreul 1811). More than a century later, Kennedy and coworkers described their biosynthesis in chicken liver microsomes (Weiss et al. 1960). The enzyme responsible was designated acyl CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT). The first DGAT identified by molecular biology techniques, now called DGAT1, was found to be a member of the membrane-bound O-acyltransferase (MBOAT) family and to be related in DNA and protein sequences to acyl CoA:cholesterol acyltransferases (ACAT or SOAT) (Cases et al. 1998b). DGAT1 is widely expressed in mammalian tissues and cells and has orthologs in both plant and animal species (Yen et al. 2008). DGAT1 is a very hydrophobic, integral membrane protein, with multiple transmembrane domains and is found in the ER.

The molecular structure of DGAT1 reveals the enzyme to be a butterfly-shaped dimer, with nine transmembrane segments in each subunit (Sui et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020). The amino-terminal segment of each monomer contacts the adjacent monomer, although structural and functional information on this contact region is lacking. The structure of the enzyme reveals insights into its catalytic mechanism (Fig. 3). A catalytic His residue, characteristic of all MBOAT enzyme family members, lies in a hydrophobic tunnel and is buried deep within the membrane. One substrate, FA CoA, accesses the catalytic center from the cytosolic side of the membrane in an evolutionarily conserved acyl CoA-binding region. A structure obtained with an acyl CoA bound to the enzyme reveals that FA CoA binding positions the thioester bond adjacent to the catalytic His residue. DGAT1 has a variety of acyl acceptor substrates that have been described, including monoacylglycerol, long-chain alcohols, and retinol (Yen et al. 2005), but for the TG synthesis reaction the acyl acceptor is DAG. Originating possibly from either leaflet of the ER bilayer, DAG may access the enzyme from a “lateral gate” of the enzyme that opens to the midplane of the membrane. The exact catalytic reaction remains uncertain, but the catalytic histidine may deprotonate the hydroxyl group of DAG to allow a nucleophilic attack of the carbonyl group of the thioester of FA CoA. The products of the reaction are CoA-SH and TG, and the latter likely exits the catalytic center via the lateral gate into the membrane bilayer.

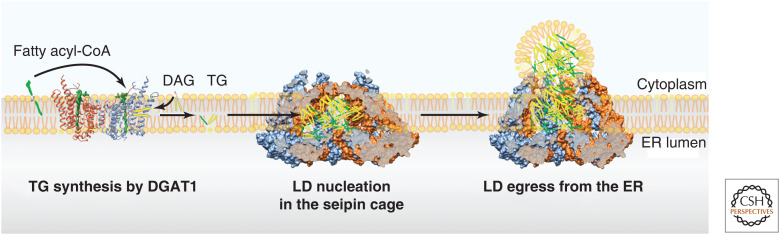

Figure 3.

Model for CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase 1 (DGAT1)-mediated triacylglycerol (TG) synthesis and liquid droplet (LD) formation at LD assembly complexes (LDACs). DGAT1 dimers synthesize TG from DAG and fatty acyl-CoA substrates. The product, TG, is released into the membrane where it rapidly diffuses. LDACs provide a space for TGs to interact with each other, rather than membrane phospholipids, thus catalyzing oil phase transition. As the nascent LD forms, it is released toward the cytoplasm by an opening of the seipin transmembrane segments in the LDAC.

DGAT1 is nearly ubiquitously expressed in mammalian tissues, and it synthesizes TG for energy storage and protects the ER from potentially toxic lipids by converting them to chemically more inert TG packaged into LDs (Chitraju et al. 2017). Loss of DGAT1 in murine tissues leads to lipotoxicity, often with ER stress (Liu et al. 2014; Chitraju et al. 2017). Conversely, overexpression of DGAT1 in macrophages, hepatocytes, heart, and skeletal muscle protects cells from lipotoxicity (Chen et al. 2002; Liu et al. 2007, 2009; Monetti et al. 2007; Koliwad et al. 2010). Additionally, the levels of DGAT1 in human adipose tissue are inversely correlated with expression of genes of ER stress (Chitraju et al. 2017).

DGAT1 was initially considered a promising therapeutic target. A host of studies in mice showed that loss of function of the enzyme led to beneficial metabolic effects (Chen and Farese 2000) and many potent and specific inhibitors of DGAT1 were developed (DeVita and Pinto 2013). However, trials in humans revealed a dose-dependent side effect of diarrhea (Denison et al. 2014). Concomitantly, humans with homozygous mutations in DGAT1 were found to have a congenital diarrhea syndrome that depends on dietary fat intake (Haas et al. 2012; Gluchowski et al. 2017). Loss of DGAT1 function causes diarrhea in humans but not mice. The reason might be that mice express a compensatory DGAT enzyme, DGAT2, in their small intestine, but humans do not (Haas et al. 2012). The precise mechanism of the intestinal toxicity for humans lacking DGAT1 in the intestine remains uncertain, but likely involves lipotoxic stress.

A second DGAT activity was purified from the oleaginous fungus Mortierella ramanniana and a gene encoding this enzyme was identified in a wide range of species, including DGAT2 in humans and the Dga1 enzyme in yeast (Cases et al. 2001; Lardizabal et al. 2001; Oelkers et al. 2002). The human DGAT2 gene encodes an enzyme with no sequence homology to DGAT1. Instead, in humans, it is part of a different gene family with seven members that also includes acyl CoA:monoacylglycerol acyltransferases (MGATs) and wax synthetases (Cases et al. 2001). Unlike DGAT1, DGAT2 does not have broad substrate specificity and primarily synthesizes TGs. A structure for DGAT2 has not been experimentally determined, but AlphaFold (Tunyasuvunakool et al. 2021) predicts that the enzyme associates with the ER via hydrophobic segments with its active site localized to the cytosolic leaflet of the ER.

Like DGAT1, DGAT2 localizes to the ER. However, unlike DGAT1, upon treating cells with oleic acid to drive LD formation, DGAT2 relocalizes around LDs, most likely in ER membranes closely associated with LDs (Kuerschner et al. 2008; Stone et al. 2009; McFie et al. 2011). At this membrane contact site, DGAT2 might synthesize TGs to directly deposit them into the LD.

Investigations of the physiological functions of DGAT2 lagged behind DGAT1 because knockout of DGAT2 leads to early postnatal lethality from skin barrier defects in mice (Stone et al. 2004). Also because of this, DGAT2 was not prioritized as a therapeutic target. However, as DGAT2 deficiency in humans apparently does not cause major problems (Ning et al. 2017), and because DGAT2 loss results in unexpected lipid metabolism phenotypes, there has been a resurgence of interest in the enzyme. Notably, loss of DGAT2 function in murine models has revealed that DGAT2 deficiency triggers a marked down-regulation of de novo lipogenesis in cells and tissues (Gluchowski et al. 2019). Conversely, overexpression of DGAT2 results in increased lipogenesis (Monetti et al. 2007). The mechanism for how DGAT2 affects lipogenesis is unclear. However, since inhibition of DGAT2 not only blocks one arm of TG synthesis but also suppresses FA synthesis, DGAT2 inhibition, through small molecules or antisense oligonucleotide technologies, has emerged as a potential therapy for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (Amin et al. 2019; Loomba et al. 2020). In early human clinical trials, DGAT2 inhibition lowered liver TG levels by ∼40% at 2 wk of treatment with no serious side effects (Amin et al. 2019). Further clinical trials are currently ongoing.

STEROL ESTER BIOSYNTHESIS

The ER also synthesizes sterol esters and stores them in LDs. Synthesis of sterol esters is catalyzed by MBOAT enzymes. In yeast, where sterol esters make up close to half of the stored neutral lipids, the Are1 and Are2 enzymes catalyze the esterification of ergosterol with fatty acyl-CoA (Yang et al. 1996). Mammalian cells also have two sterol O-acyltransferase (SOAT or ACAT) enzymes. SOAT1/ACAT1, discovered by Chang and colleagues (Yang et al. 1996) is found in most cell types and accounts for cholesterol ester synthesis in macrophages and the adrenal gland (Meiner et al. 1996). SOAT2/ACAT2, discovered by the Farese, Sturley, and Rudel groups (Anderson et al. 1998; Cases et al. 1998a; Oelkers et al. 1998) accounts for cholesterol ester synthesis in tissues that secrete cholesterol esters as components of lipoproteins, such as intestine and liver (Buhman et al. 2000). The cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structures of SOAT1 and SOAT2 were recently reported (Guan et al. 2020; Long et al. 2020, 2021), and their reaction mechanism is similar to that of DGAT enzymes, but in this case the enzymes can form tetramers and use the hydroxyl group of cholesterol as the acyl acceptor.

In some specific mammalian cell types that are specialized in cholesterol handling, such as adrenocortical cells (Meiner et al. 1998) and cholesterol-rich macrophage foam cells of atherosclerotic regions, cholesterol esters are found as the predominant neutral lipid in LDs. Storage of sterols likely serves two evolutionarily conserved functions: preservation of excess sterols for later use and detoxification of sterols to prevent them from inhibiting cellular processes. In agreement with the later hypothesis, inhibition of SOAT1/ACAT1 can have detrimental consequences as free cholesterol accumulates in some tissues (Meiner et al. 1998). However, since cholesterol accumulation in the vasculature causes the formation of atherosclerotic plaques, reducing cholesterol esters in circulating lipoproteins via inhibition of SOAT2/ACAT2 may provide a therapeutic avenue for preventing or treating cardiovascular disease. This strategy was demonstrated to be effective in a murine model (Willner et al. 2003) but has not been formally tested in humans.

LD BIOGENESIS

Synthesis of water-insoluble TG molecules generates a challenge for cells in how to store and access these molecules. The ER is key for this, generating an emulsion of oil droplets in cells. After their synthesis, TGs can diffuse within the bilayer (Santinho et al. 2020). Studies employing NMR spectroscopy showed that PC bilayers can accommodate up to ∼2.8% TG before phase separation occurs (Hamilton and Small 1981). If TG concentrations increase beyond this level, TG will phase separate and form oil drops in the bilayer.

For many years, most researchers presumed LD formation was a passive process of random sites of phase separation in the ER once enough TG has accumulated. However, we now know that cells organize and regulate LD formation and have evolved intricate protein machinery to allow storage and mobilization of TG in LDs. For instance, LD organelles have specific proteins that localized to their surfaces, including perilipin proteins (Magnin et al. 1989; Greenberg et al. 1991) and many enzymes of lipid metabolism, and that the monolayer surfaces of LDs were rich hubs of metabolic activity.

To form LDs from the ER, dedicated protein machinery, termed LD assembly complexes (LDACs) has evolved to ensure that LDs form in a regular manner at TG concentrations below the threshold that leads to spontaneous LD formation. LDACs comprise oligomeric complexes localized throughout the ER where they facilitate LD formation. Several proteins are part of this complex. The primary protein, which is required for normal LD formation, is seipin, encoded by the BSCL2 gene in humans and the Fld1 gene in yeast (Szymanski et al. 2007; Fei et al. 2008; Salo et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2016). Other proteins include LDAF1 (alternatively called promethin) (Castro et al. 2019; Chung et al. 2019) in many organisms, including flies and humans, and Ldb16 and Ldo proteins in yeast (Wang et al. 2014; Eisenberg-Bord et al. 2018; Teixeira et al. 2018; Castro et al. 2019). In addition, yet other proteins may be components of LDACs. For example, a host of proteins, including Pex30, the lipin-homolog Pah1, and its activator Nem1, localize to sites of LD formation in yeast (Wolinski et al. 2015; Joshi et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2018; Choudhary et al. 2020) and may interact with the LDAC machinery.

The seipin gene was originally identified from mutations that give rise to generalized lipodystrophy (Magré et al. 2001). The seipin gene encodes a ∼44 kDa protein with two transmembrane segments, a short cytosolic tail and a larger ER luminal domain. In the ER, seipin forms an oligomeric ring (Binns et al. 2010; Sui et al. 2018; Yan et al. 2018). LDs appear to form at seipin complexes (Chung et al. 2019) and each LD associates with at least one seipin focus at the interface with the ER (Szymanski et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2016).

Recent studies of the structure of the seipin oligomeric complex have also shed some light on its function in LDACs. The first two structures obtained by cryo-EM showed highly conserved ER lumenal domains for Drosophila and the human protein (Sui et al. 2018; Yan et al. 2018): similar, large 15-nm oligomeric rings composed of 12 or 11 β-sandwich domains in flies or humans, respectively. Each subunit domain positions a hydrophobic helix toward the center of the ring in a position likely embedded in the lumenal leaflet of the ER membrane. The studies suggested a model in which the seipin lumenal domains may anchor, forming LDs to the ER and aid by promoting TG accumulation at sites of nascent LD formation. In addition, based on structural similarities and biochemical experiments, the lumenal domain of seipin was suggested to bind phosphatidic acid (Yan et al. 2018) but the relevance of this is not yet clear. In addition to the lumenal domains, the transmembrane segments of seipin are evolutionarily conserved and important for the function of the protein (Arlt et al. 2022). Cryo-EM structural models of seipin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae include the transmembrane segments of the yeast decameric oligomer (Klug et al. 2021; Arlt et al. 2022; Kim et al. 2022). The lumenal domains and transmembrane segments form a cage-like structure in the ER. Two conformations of the transmembrane segments in one of the cryo-EM structures suggests that this cage is flexible and can open toward the cytoplasm. These observations led to a working model for how seipin functions to facilitate LD formation (Fig. 3). TGs formed by DGAT enzymes diffuse throughout the ER bilayer at concentrations below the phase-transition point. Seipin transmembrane segments form a cage that excludes phospholipids and favors TGs entering the cage where they can interact with hydrophobic transmembrane segments of seipin, and possibly other LDAC accessory proteins such as LDAF1. These interactions favor nucleation of TG phase separation at concentrations below 2.8% in the membrane, so that LDs form at seipin complexes rather than at random locations in the ER. TG then accumulates in the growing LDs due to Ostwald ripening (i.e., diffusion of TGs in the ER from smaller to larger droplets, thermodynamically driven because larger droplets are more energetically favored for more TGs to achieve a lower energy state). In this manner, the LD grows and emerges from the seipin oligomer at the cytosolic face of the ER. Flexibility in the transmembrane segments may allow the transmembrane segments to open as the LD forms, essentially forming a neck of the LD that is attached to the ER. The diameter of such connections that were observed by electron microscopy (10–15 nm) is similar to the diameter of the seipin complex (Salo et al. 2019).

It appears that the seipin transmembrane segments may serve to restrict some ER proteins from accessing forming LDs. For example, a hydrophobic hairpin segment of GPAT4, termed LiveDrop, can access and localize to LDs as they form (Wang et al. 2016). Additionally, the ER proteins LD-associated hydrolase (LDAH) and UBXD8 target to nascent forming LDs (Song et al. 2021). In contrast, full-length GPAT4 and other ER proteins do not localize to LDs during formation, but apparently target LDs at later timepoints, well after formation, via other mechanisms. In support of the notion that seipin excludes numerous proteins from forming LDs, many proteins that normally do not target to newly formed LDs can aberrantly target these LDs when seipin is deleted and LDs form in a non-seipin-dependent manner (Grippa et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2016).

In human cells, LDAF1 is part of the LDAC (Chung et al. 2019) and required for normal LD formation. The structure of LDAF1 is unknown but it interacts with the hydrophobic helix of seipin and localizes to the sites of LD formation (Chung et al. 2019). As LDs form and grow, LDAF1 coats the expanding surface of the emerging LDs. The function of LDAF1 is unclear but LDs form abnormally in cells lacking LDAF1. There are fewer and larger LDs, and they form at an apparently higher cellular TG concentration (Chung et al. 2019). Therefore, LDAF1 appears to be nonessential but a modifier of the LD formation process. Interestingly, seipin deficiency results in loss of LDAF1 in addition to seipin, suggesting that seipin is required to maintain cellular levels of LDAF1 (Chung et al. 2019). In yeast, the distantly related Ldo proteins may act similarly to LDAF1 in mammalian cells (Eisenberg-Bord et al. 2018; Teixeira et al. 2018).

The model of LD formation at LDAC sites containing seipin is currently the prevailing model. However, studies in yeast in particular have suggested alternative factors that may contribute to LD formation and that formation may occur at specialized domains of the ER (Choudhary and Schneiter 2020). For example, the PEX genes PEX30 and PEX29, found in the ER, are implicated as promoting LD formation in yeast (Joshi et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2018; Ferreira and Carvalho 2021) and this involves the reticulon homology domains of these proteins. PEX30 has a mammalian ortholog, multiple C2, and transmembrane domain-containing protein 2 (MCTP2), which may function similarly (Joshi et al. 2021, 2022). Related to this, numerous other tubule-promoting ER proteins, such as atlastin and REEP proteins, appear to promote LD formation (Klemm et al. 2013). This may be because they promote tubule formation, and tubule formation in turn promotes LD formation (Santinho et al. 2020).

Numerous proteins, on the order of tens to hundreds, target to the surface of LDs. The Lipid Droplet Knowledge Portal (Mejhert et al. 2022; www.lipiddroplet.org) integrates information for LD proteins and other systematic data sets relating to LD biology. Proteins that target LDs are rich in enzymes of lipid synthesis or catabolism, but also many proteins of undefined function localize to LD surfaces. The targeting of proteins to LDs can be viewed from the lens of LD formation, and there are several categories of LD-targeted proteins. Some proteins, such as PLIN3, can target LDs from the cytosol just after LD formation (Chung et al. 2019) in a process termed cytosol-to-LD (CYTOLD) targeting (for review, see Olarte et al. 2022). The principles of CYTOLD targeting involve protein binding to LD monolayers via hydrophobic sequences or amphipathic helices that interact with and bind packing defects at the LD surface (Prévost et al. 2018). Other proteins target LDs via ER-to-LD (ERTOLD) targeting. Such proteins can target either during formation or later after LDs are formed. Available data suggest that late ERTOLD targeting occurs via ER-LD membrane bridges that are established after initial LD formation at LDAC (for review, see Olarte et al. 2022). Among the proteins that may target via late ERTOLD are proteins important in NAFLD disease pathogenesis, such as ATGL and possibly PNPLA3 (Soni et al. 2009). However, most studies of these proteins use heterologous overexpression, so the pathways that endogenous proteins take remain to be determined. The principles of targeting of another important disease protein, the HSD17B13 enzyme with human genetic variants modifying the progression of liver disease (Ma et al. 2020) also remains to be elucidated.

Nearly all eukaryotic cells appear to have the capacity to form cytosolic LDs from the ER when large amounts of oleic acid are provided as a substrate to generate TG. However, some cells evolved the capacity to secrete TG via the lumen of the ER as components of secreted lipoproteins. This process occurs in Drosophila, where TGs can be secreted on lipoproteins formed with vitellogenin, but is best understood in mammalian cells, where TGs are secreted as part of apolipoprotein B (apo-B)-containing lipoproteins. This cellular adaptation can be found in cells, such as intestinal enterocytes, hepatocytes, and yolk sac endodermal cells (Ma et al. 2020), and it requires apo-B and the microsomal TG transfer protein (MTP). How lipoproteins are synthesized and secreted is the subject of multiple reviews (Ginsberg 1998; Ginsberg and Fisher 2009; Sirwi and Hussain 2018). A current model is that as apo-B is translated through the translocon and cotranslationally lipidated by MTP, which can facilitate the transfer of both TG and PL from the ER bilayer to the nascent lipoprotein (Young 1990). Other proteins, such as Sar1B, CIDE-B, TM6SF2, and TGH have been implicated in this process (Jones et al. 2003; Dolinsky et al. 2004; Ye et al. 2009; Smagris et al. 2016). For larger multicellular organisms, the formation of these TG-rich lipoproteins is essential, likely to transport energy stores and fat-soluble substances, such as vitamins, throughout the aqueous circulation. Total deficiency of either apo-B or MTP results in a severe depletion of apo-B-containing lipoproteins from the circulation, a condition called abetalipoproteinemia (Rader and Brewer 1993).

The catabolism of TGs in LDs is not the focus of this review, but can be found elsewhere (Yang and Mottillo 2020; Grabner et al. 2021). In brief, TGs are hydrolyzed at the LD surface predominantly via the actions of adipose TG lipase (ATGL) with coactivator CGI-58 to generate FA and DAG products (Zimmermann et al. 2004; Lass et al. 2006). DAG is then further hydrolyzed by hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) to generate monoacylglycerol (MAG) and fatty acids (Haemmerle et al. 2002). MAG can be further hydrolyzed to glycerol and FA by MAG lipase (Mulvihill and Nomura 2013). This process of sequential hydrolysis, or lipolysis, is subject to different regulatory factors in different cells or tissues. Alternatively, TG in LDs can be turned over via selective autophagy of LDs, or lipophagy (Filali-Mouncef et al. 2022). Currently, little is known about the molecular mechanism and regulation of lipophagy.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Much progress has been made in our understanding of lipid synthesis in the ER and the biochemical mechanisms of these reactions are becoming clear. Yet, important and intriguing questions remain.

For glycerolipid synthesis, how are the different ER enzymes of the pathways regulated? How are they organized, and do they form a multi-enzyme complex? Are substrates channeled between reactions? How do cells move lipid precursors between their location of synthesis in the ER and their final destinations elsewhere in the cell? How are lipid compositions maintained in the ER that differ markedly from other organelles and the plasma membrane? What are the structures and biochemical mechanisms for GPAT and AGPAT enzymes?

For TG synthesis and LDs, how is TG synthesis activated and what determines whether DAG flows into phospholipids or TG? What is the catalytic mechanism of DGAT2? How do ER enzymes catalyzing the same biochemical reactions, such as DGAT1 and DGAT2, participate in different biological processes in cells? Which functions do these enzymes have in different aspects of physiology? Will DGAT inhibition turn out to be useful for pharmaceutical purposes? Will the enzymes be useful for industrial purposes concerning oil production? With so many new tools available to investigators, the answers to these questions are within reach.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the many investigators, in our laboratory and those of colleagues, who have contributed to the knowledge we attempted to summarize in this review, and we regret that due to space limitations we could not cite all the many important papers in a brief review. We also thank M. Ormenaj and G. Howard for editorial services. This work and review were supported by NIH Grants NIH R01GM124348 (to R.V.F.) and R01GM097194 (to T.C.W). Tobias Walther is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Editors: Susan Ferro-Novick, Tom A. Rapoport, and Randy Schekman

Additional Perspectives on The Endoplasmic Reticulum available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Agarwal AK, Arioglu E, De Almeida S, Akkoc N, Taylor SI, Bowcock AM, Barnes RI, Garg A. 2002. AGPAT2 is mutated in congenital generalized lipodystrophy linked to chromosome 9q34. Nat Genet 31: 21–23. 10.1038/ng880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal AK, Sukumaran S, Cortés VA, Tunison K, Mizrachi D, Sankella S, Gerard RD, Horton JD, Garg A. 2011. Human 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate O-acyltransferase isoforms 1 and 2: biochemical characterization and inability to rescue hepatic steatosis in Agpat2−/− gene lipodystrophic mice. J Biol Chem 286: 37676–37691. 10.1074/jbc.M111.250449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin NB, Carvajal-Gonzalez S, Purkal J, Zhu T, Crowley C, Perez S, Chidsey K, Kim AM, Goodwin B. 2019. Targeting diacylglycerol acyltransferase 2 for the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Sci Transl Med 11: eaav9701. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav9701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RA, Joyce C, Davis M, Reagan JW, Clark M, Shelness GS, Rudel LL. 1998. Identification of a form of acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase specific to liver and intestine in nonhuman primates. J Biol Chem 273: 26747–26754. 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlt H, Sui X, Folger B, Adams C, Chen X, Remme R, Hamprecht FA, DiMaio F, Liao M, Goodman JM, et al. 2022. Seipin forms a flexible cage at lipid droplet formation sites. Nat Struct Molec Biol 29: 194–202. 10.1038/s41594-021-00718-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binns D, Lee S, Hilton CL, Jiang QX, Goodman JM. 2010. Seipin is a discrete homooligomer. Biochemistry 49: 10747–10755. 10.1021/bi1013003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blunsom NJ, Cockcroft S. 2020. CDP-diacylglycerol synthases (CDS): gateway to phosphatidylinositol and cardiolipin synthesis. Front Cell Dev Biol 8: 63. 10.3389/fcell.2020.00063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasaemle DL, Dolios G, Shapiro L, Wang R. 2004. Proteomic analysis of proteins associated with lipid droplets of basal and lipolytically stimulated 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem 279: 46835–46842. 10.1074/jbc.M409340200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhman KK, Accad M, Novak S, Choi RS, Wong JS, Hamilton RL, Turley S, Farese RV Jr. 2000. Resistance to diet-induced hypercholesterolemia and gallstone formation in ACAT2-deficient mice. Nat Med 6: 1341–1347. 10.1038/82153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cases S, Novak S, Zheng YW, Myers HM, Lear SR, Sande E, Welch CB, Lusis AJ, Spencer TA, Krause BR, et al. 1998a. ACAT-2, a second mammalian acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase. Its cloning, expression, and characterization. J Biol Chem 273: 26755–26764. 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cases S, Smith SJ, Zheng YW, Myers HM, Lear SR, Sande E, Novak S, Collins C, Welch CB, Lusis AJ, et al. 1998b. Identification of a gene encoding an acyl CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase, a key enzyme in triacylglycerol synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 95: 13018–13023. 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cases S, Stone SJ, Zhou P, Yen E, Tow B, Lardizabal KD, Voelker T, Farese RV Jr. 2001. Cloning of DGAT2, a second mammalian diacylglycerol acyltransferase, and related family members. J Biol Chem 276: 38870–38876. 10.1074/jbc.M106219200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro IG, Eisenberg-Bord M, Persiani E, Rochford JJ, Schuldiner M, Bohnert M. 2019. Promethin is a conserved seipin partner protein. Cells 8: 268. 10.3390/cells8030268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HC, Farese RV Jr. 2000. DGAT and triglyceride synthesis: a new target for obesity treatment? Trends Cardiovasc Med 10: 188–192. 10.1016/S1050-1738(00)00066-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HC, Stone SJ, Zhou P, Buhman KK, Farese RV Jr. 2002. Dissociation of obesity and impaired glucose disposal in mice overexpressing acyl coenzyme A:diacylglycerol acyltransferase 1 in white adipose tissue. Diabetes 51: 3189–3195. 10.2337/diabetes.51.11.3189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YQ, Kuo MS, Li S, Bui HH, Peake DA, Sanders PE, Thibodeaux SJ, Chu S, Qian YW, Zhao Y, et al. 2008. AGPAT6 is a novel microsomal glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase. J Biol Chem 283: 10048–10057. 10.1074/jbc.M708151200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevreul M. 1811. A chemical study of oils and fats of animal origin (ed. Dijkstra AJ, List GR), p. 348. AOCS Lipid Library Urbana, IL. [Google Scholar]

- Chitraju C, Mejhert N, Haas JT, Diaz-Ramirez LG, Grueter CA, Imbriglio JE, Pinto S, Koliwad SK, Walther TC, Farese RV Jr. 2017. Triglyceride synthesis by DGAT1 protects adipocytes from lipid-induced ER stress during lipolysis. Cell Metab 26: 407–418.e3. 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary V, Schneiter R. 2020. Lipid droplet biogenesis from specialized ER subdomains. Microb Cell 7: 218–221. 10.15698/mic2020.08.727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary V, El Atab O, Mizzon G, Prinz WA, Schneiter R. 2020. Seipin and Nem1 establish discrete ER subdomains to initiate yeast lipid droplet biogenesis. J Cell Biol 219: e201910177. 10.1083/jcb.201910177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung J, Wu X, Lambert TJ, Lai ZW, Walther TC, Farese RV Jr. 2019. LDAF1 and seipin form a lipid droplet assembly complex. Dev Cell 51: 551–563.e7. 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman RA. 2019. It takes a village: channeling fatty acid metabolism and triacylglycerol formation via protein interactomes. J Lipid Res 60: 490–497. 10.1194/jlr.S091843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper DE, Grevengoed TJ, Klett EL, Coleman RA. 2015. Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase isoform-4 (GPAT4) limits oxidation of exogenous fatty acids in brown adipocytes. J Biol Chem 290: 15112–15120. 10.1074/jbc.M115.649970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison H, Nilsson C, Löfgren L, Himmelmann A, Mårtensson G, Knutsson M, Al-Shurbaji A, Tornqvist H, Eriksson JW. 2014. Diacylglycerol acyltransferase 1 inhibition with AZD7687 alters lipid handling and hormone secretion in the gut with intolerable side effects: a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 16: 334–343. 10.1111/dom.12221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVita RJ, Pinto S. 2013. Current status of the research and development of diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 1 (DGAT1) inhibitors. J Med Chem 56: 9820–9825. 10.1021/jm4007033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey P, Han GS, Carman GM. 2020. A review of phosphatidate phosphatase assays. J Lipid Res 61: 1556–1564. 10.1194/jlr.R120001092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolinsky VW, Gilham D, Alam M, Vance DE, Lehner R. 2004. Triacylglycerol hydrolase: role in intracellular lipid metabolism. Cell Mol Life Sci 61: 1633–1651. 10.1007/s00018-004-3426-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg-Bord M, Mari M, Weill U, Rosenfeld-Gur E, Moldavski O, Castro IG, Soni KG, Harpaz N, Levine TP, Futerman AH, et al. 2018. Identification of seipin-linked factors that act as determinants of a lipid droplet subpopulation. J Cell Biol 217: 269–282. 10.1083/jcb.201704122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellingson JS, Hill EE, Lands WE. 1970. The control of fatty acid composition in glycerolipids of the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim Biophys Acta 196: 176–192. 10.1016/0005-2736(70)90005-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei W, Shui G, Gaeta B, Du X, Kuerschner L, Li P, Brown AJ, Wenk MR, Parton RG, Yang H. 2008. Fld1p, a functional homologue of human seipin, regulates the size of lipid droplets in yeast. J Cell Biol 180: 473–482. 10.1083/jcb.200711136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson PJ, Chen S, Tayeh MK, Ochoa L, Leal SM, Pelet A, Munnich A, Lyonnet S, Majeed HA, El-Shanti H. 2005. Homozygous mutations in LPIN2 are responsible for the syndrome of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis and congenital dyserythropoietic anaemia (Majeed syndrome). J Med Genet 42: 551–557. 10.1136/jmg.2005.030759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira JV, Carvalho P. 2021. Pex30-like proteins function as adaptors at distinct ER membrane contact sites. J Cell Biol 220: e202103176. 10.1083/jcb.202103176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filali-Mouncef Y, Hunter C, Roccio F, Zagkou S, Dupont N, Primard C, Proikas-Cezanne T, Reggiori F. 2022. The ménage à trois of autophagy, lipid droplets and liver disease. Autophagy 18: 50–72. 10.1080/15548627.2021.1895658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale SE, Frolov A, Han X, Bickel PE, Cao L, Bowcock A, Schaffer JE, Ory DS. 2006. A regulatory role for 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate-O-acyltransferase 2 in adipocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem 281: 11082–11089. 10.1074/jbc.M509612200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg HN. 1998. Lipoprotein physiology. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 27: 503–519. 10.1016/S0889-8529(05)70023-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg HN, Fisher EA. 2009. The ever-expanding role of degradation in the regulation of apolipoprotein B metabolism. J Lipid Res 50: S162–S166. 10.1194/jlr.R800090-JLR200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluchowski NL, Chitraju C, Picoraro JA, Mejhert N, Pinto S, Xin W, Kamin DS, Winter HS, Chung WK, Walther TC, et al. 2017. Identification and characterization of a novel DGAT1 missense mutation associated with congenital diarrhea. J Lipid Res 58: 1230–1237. 10.1194/jlr.P075119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluchowski NL, Gabriel KR, Chitraju C, Bronson RT, Mejhert N, Boland S, Wang K, Lai ZW, Farese RV Jr, Walther TC. 2019. Hepatocyte deletion of triglyceride-synthesis enzyme Acyl CoA: diacylglycerol acyltransferase 2 reduces steatosis without increasing inflammation or fibrosis in mice. Hepatology 70: 1972–1985. 10.1002/hep.30765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabner GF, Xie H, Schweiger M, Zechner R. 2021. Lipolysis: cellular mechanisms for lipid mobilization from fat stores. Nat Metab 3: 1445–1465. 10.1038/s42255-021-00493-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg AS, Egan JJ, Wek SA, Garty NB, Blanchette-Mackie EJ, Londos C. 1991. Perilipin, a major hormonally regulated adipocyte-specific phosphoprotein associated with the periphery of lipid storage droplets. J Biol Chem 266: 11341–11346. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)99168-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grippa A, Buxó L, Mora G, Funaya C, Idrissi FZ, Mancuso F, Gomez R, Muntanyà J, Sabidó E, Carvalho P. 2015. The seipin complex Fld1/Ldb16 stabilizes ER-lipid droplet contact sites. J Cell Biol 211: 829–844. 10.1083/jcb.201502070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan C, Niu Y, Chen SC, Kang Y, Wu JX, Nishi K, Chang CCY, Chang TY, Luo T, Chen L. 2020. Structural insights into the inhibition mechanism of human sterol O-acyltransferase 1 by a competitive inhibitor. Nat Commun 11: 2478. 10.1038/s41467-020-16288-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas JT, Winter HS, Lim E, Kirby A, Blumenstiel B, DeFelice M, Gabriel S, Jalas C, Branski D, Grueter CA, et al. 2012. DGAT1 mutation is linked to a congenital diarrheal disorder. J Clin Invest 122: 4680–4684. 10.1172/JCI64873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haemmerle G, Zimmermann R, Hayn M, Theussl C, Waeg G, Wagner E, Sattler W, Magin TM, Wagner EF, Zechner R. 2002. Hormone-sensitive lipase deficiency in mice causes diglyceride accumulation in adipose tissue, muscle, and testis. J Biol Chem 277: 4806–4815. 10.1074/jbc.M110355200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JA, Small DM. 1981. Solubilization and localization of triolein in phosphatidylcholine bilayers: a 13C NMR study. Proc Natl Acad Sci 78: 6878–6882. 10.1073/pnas.78.11.6878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honsho M, Fujiki Y. 2017. Plasmalogen homeostasis—regulation of plasmalogen biosynthesis and its physiological consequence in mammals. FEBS Lett 591: 2720–2729. 10.1002/1873-3468.12743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain IH, Calvo SE, Markhard AL, Skinner OS, To TL, Ast T, Mootha VK. 2020. Genetic screen for cell fitness in high or low oxygen highlights mitochondrial and lipid metabolism. Cell 181: 716–727.e11. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B, Jones EL, Bonney SA, Patel HN, Mensenkamp AR, Eichenbaum-Voline S, Rudling M, Myrdal U, Annesi G, Naik S, et al. 2003. Mutations in a Sar1 GTPase of COPII vesicles are associated with lipid absorption disorders. Nat Genet 34: 29–31. 10.1038/ng1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi AS, Nebenfuehr B, Choudhary V, Satpute-Krishnan P, Levine TP, Golden A, Prinz WA. 2018. Lipid droplet and peroxisome biogenesis occur at the same ER subdomains. Nat Commun 9: 2940. 10.1038/s41467-018-05277-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi AS, Ragusa JV, Prinz WA, Cohen S. 2021. Multiple C2 domain-containing transmembrane proteins promote lipid droplet biogenesis and growth at specialized endoplasmic reticulum subdomains. Mol Biol Cell 32: 1147–1157. 10.1091/mbc.E20-09-0590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A, Ragusa J, Prinz W, Cohen S. 2022. Formation of nascent lipid droplets at specialized ER subdomains. FASEB J 10.1096/fasebj.2022.36.S1.0R300 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khayyo VI, Hoffmann RM, Wang H, Bell JA, Burke JE, Reue K, Airola MV. 2020. Crystal structure of a lipin/Pah phosphatidic acid phosphatase. Nat Commun 11: 1309. 10.1038/s41467-020-15124-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Chung J, Arlt H, Pak AJ, Farese RV, Walther TC, Voth GA. 2022. Seipin transmembrane segments critically function in triglyceride nucleation and lipid droplet budding from the membrane. eLife 10.7554/eLife.75808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemm RW, Norton JP, Cole RA, Li CS, Park SH, Crane MM, Li L, Jin D, Boye-Doe A, Liu TY, et al. 2013. A conserved role for atlastin GTPases in regulating lipid droplet size. Cell Rep 3: 1465–1475. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klett EL, Chen S, Yechoor A, Lih FB, Coleman RA. 2017. Long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase isoforms differ in preferences for eicosanoid species and long-chain fatty acids. J Lipid Res 58: 884–894. 10.1194/jlr.M072512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klug YA, Deme JC, Corey RA, Renne MF, Stansfeld PJ, Lea SM, Carvalho P. 2021. Mechanism of lipid droplet formation by the yeast Sei1/Ldb16 seipin complex. Nat Commun 12: 5892. 10.1038/s41467-021-26162-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koliwad SK, Streeper RS, Monetti M, Cornelissen I, Chan L, Terayama K, Naylor S, Rao M, Hubbard B, Farese RV Jr. 2010. DGAT1-dependent triacylglycerol storage by macrophages protects mice from diet-induced insulin resistance and inflammation. J Clin Invest 120: 756–767. 10.1172/JCI36066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuerschner L, Moessinger C, Thiele C. 2008. Imaging of lipid biosynthesis: how a neutral lipid enters lipid droplets. Traffic 9: 338–352. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00689.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatek JM, Han GS, Carman GM. 2020. Phosphatidate-mediated regulation of lipid synthesis at the nuclear/endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 1865: 158434. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2019.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lardizabal KD, Mai JT, Wagner NW, Wyrick A, Voelker T, Hawkins DJ. 2001. DGAT2 is a new diacylglycerol acyltransferase gene family: purification, cloning, and expression in insect cells of two polypeptides from Mortierella ramanniana with diacylglycerol acyltransferase activity. J Biol Chem 276: 38862–38869. 10.1074/jbc.M106168200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lass A, Zimmermann R, Haemmerle G, Riederer M, Schoiswohl G, Schweiger M, Kienesberger P, Strauss JG, Gorkiewicz G, Zechner R. 2006. Adipose triglyceride lipase-mediated lipolysis of cellular fat stores is activated by CGI-58 and defective in Chanarin–Dorfman syndrome. Cell Metab 3: 309–319. 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin TM, Kim JH, Granger DA, Vance JE, Coleman RA. 2001. Acyl-CoA synthetase isoforms 1, 4, and 5 are present in different subcellular membranes in rat liver and can be inhibited independently. J Biol Chem 276: 24674–24679. 10.1074/jbc.M102036200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Zhang Y, Chen N, Shi X, Tsang B, Yu YH. 2007. Upregulation of myocellular DGAT1 augments triglyceride synthesis in skeletal muscle and protects against fat-induced insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 117: 1679–1689. 10.1172/JCI30565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Shi X, Bharadwaj KG, Ikeda S, Yamashita H, Yagyu H, Schaffer JE, Yu YH, Goldberg IJ. 2009. DGAT1 expression increases heart triglyceride content but ameliorates lipotoxicity. J Biol Chem 284: 36312–36323. 10.1074/jbc.M109.049817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Trent CM, Fang X, Son NH, Jiang H, Blaner WS, Hu Y, Yin YX, Farese RV Jr, Homma S, et al. 2014. Cardiomyocyte-specific loss of diacylglycerol acyltransferase 1 (DGAT1) reproduces the abnormalities in lipids found in severe heart failure. J Biol Chem 289: 29881–29891. 10.1074/jbc.M114.601864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long T, Sun Y, Hassan A, Qi X, Li X. 2020. Structure of nevanimibe-bound tetrameric human ACAT1. Nature 581: 339–343. 10.1038/s41586-020-2295-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long T, Liu Y, Li X. 2021. Molecular structures of human ACAT2 disclose mechanism for selective inhibition. Structure 29: 1410–1418.e4. 10.1016/j.str.2021.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomba R, Morgan E, Watts L, Xia S, Hannan LA, Geary RS, Baker BF, Bhanot S. 2020. Novel antisense inhibition of diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 2 for treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 5: 829–838. 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30186-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z, Onorato JM, Chen L, Nelson DW, Yen CE, Cheng D. 2017. Synthesis of neutral ether lipid monoalkyl-diacylglycerol by lipid acyltransferases. J Lipid Res 58: 1091–1099. 10.1194/jlr.M073445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Karki S, Brown PM, Lin DD, Podszun MC, Zhou W, Belyaeva OV, Kedishvili NY, Rotman Y. 2020. Characterization of essential domains in HSD17B13 for cellular localization and enzymatic activity. J Lipid Res 61: 1400–1409. 10.1194/jlr.RA120000907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnin M, Cooper HM, Mick G. 1989. Retinohypothalamic pathway: a breach in the law of Newton-Müller-Gudden? Brain Res 488: 390–397. 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90737-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magré J, Delépine M, Khallouf E, Gedde-Dahl T Jr, Van Maldergem L, Sobel E, Papp J, Meier M, Mégarbané A, Bachy A, et al. 2001. Identification of the gene altered in Berardinelli-Seip congenital lipodystrophy on chromosome 11q13. Nat Genet 28: 365–370. 10.1038/ng585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda M, Miyazaki-Anzai S, Keenan AL, Okamura K, Kendrick J, Chonchol M, Offermanns S, Ntambi JM, Kuro OM, Miyazaki M. 2015. Saturated phosphatidic acids mediate saturated fatty acid-induced vascular calcification and lipotoxicity. J Clin Invest 125: 4544–4558. 10.1172/JCI82871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFie PJ, Banman SL, Kary S, Stone SJ. 2011. Murine diacylglycerol acyltransferase-2 (DGAT2) can catalyze triacylglycerol synthesis and promote lipid droplet formation independent of its localization to the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 286: 28235–28246. 10.1074/jbc.M111.256008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiner VL, Cases S, Myers HM, Sande ER, Bellosta S, Schambelan M, Pitas RE, McGuire J, Herz J, Farese RV Jr. 1996. Disruption of the acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase gene in mice: evidence suggesting multiple cholesterol esterification enzymes in mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci 93: 14041–14046. 10.1073/pnas.93.24.14041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiner VL, Welch CL, Cases S, Myers HM, Sande E, Lusis AJ, Farese RV Jr. 1998. Adrenocortical lipid depletion gene (ald) in AKR mice is associated with an acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT) mutation. J Biol Chem 273: 1064–1069. 10.1074/jbc.273.2.1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejhert N, Gabriel KR, Frendo-Cumbo S, Krahmer N, Song J, Kuruvilla L, Chitraju C, Boland S, Jang DK, von Grotthuss M, et al. 2022. The lipid droplet knowledge portal: a resource for systematic analyses of lipid droplet biology. Dev Cell 57: 387–397.e4. 10.1016/j.devcel.2022.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monetti M, Levin MC, Watt MJ, Sajan MP, Marmor S, Hubbard BK, Stevens RD, Bain JR, Newgard CB, Farese RV Sr, et al. 2007. Dissociation of hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance in mice overexpressing DGAT in the liver. Cell Metab 6: 69–78. 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvihill MM, Nomura DK. 2013. Therapeutic potential of monoacylglycerol lipase inhibitors. Life Sci 92: 492–497. 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.10.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning T, Zou Y, Yang M, Lu Q, Chen M, Liu W, Zhao S, Sun Y, Shi J, Ma Q, et al. 2017. Genetic interaction of DGAT2 and FAAH in the development of human obesity. Endocrine 56: 366–378. 10.1007/s12020-017-1261-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelkers P, Behari A, Cromley D, Billheimer JT, Sturley SL. 1998. Characterization of two human genes encoding acyl coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase-related enzymes. J Biol Chem 273: 26765–26771. 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelkers P, Cromley D, Padamsee M, Billheimer JT, Sturley SL. 2002. The DGA1 gene determines a second triglyceride synthetic pathway in yeast. J Biol Chem 277: 8877–8881. 10.1074/jbc.M111646200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olarte MJ, Swanson JMJ, Walther TC, Farese RV Jr. 2022. The CYTOLD and ERTOLD pathways for lipid droplet-protein targeting. Trends Biochem Sci 47: 39–51. 10.1016/j.tibs.2021.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Péterfy M, Phan J, Xu P, Reue K. 2001. Lipodystrophy in the fld mouse results from mutation of a new gene encoding a nuclear protein, lipin. Nat Genet 27: 121–124. 10.1038/83685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccolis M, Bond LM, Kampmann M, Pulimeno P, Chitraju C, Jayson CBK, Vaites LP, Boland S, Lai ZW, Gabriel KR, et al. 2019. Probing the global cellular responses to lipotoxicity caused by saturated fatty acids. Mol Cell 74: 32–44.e8. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.01.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad SS, Garg A, Agarwal AK. 2011. Enzymatic activities of the human AGPAT isoform 3 and isoform 5: localization of AGPAT5 to mitochondria. J Lipid Res 52: 451–462. 10.1194/jlr.M007575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prévost C, Sharp ME, Kory N, Lin Q, Voth GA, Farese RV Jr, Walther TC. 2018. Mechanism and determinants of amphipathic helix-containing protein targeting to lipid droplets. Dev Cell 44: 73–86.e4. 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rader DJ, Brewer HB Jr. 1993. Abetalipoproteinemia. New insights into lipoprotein assembly and vitamin E metabolism from a rare genetic disease. JAMA 270: 865–869. 10.1001/jama.1993.03510070087042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinisch KM, Prinz WA. 2021. Mechanisms of nonvesicular lipid transport. J Cell Biol 220: e202012058. 10.1083/jcb.202012058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reue K, Wang H. 2019. Mammalian lipin phosphatidic acid phosphatases in lipid synthesis and beyond: metabolic and inflammatory disorders. J Lipid Res 60: 728–733. 10.1194/jlr.S091769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salo VT, Belevich I, Li S, Karhinen L, Vihinen H, Vigouroux C, Magré J, Thiele C, Hölttä-Vuori M, Jokitalo E, et al. 2016. Seipin regulates ER-lipid droplet contacts and cargo delivery. EMBO J 35: 2699–2716. 10.15252/embj.201695170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salo VT, Li S, Vihinen H, Hölttä-Vuori M, Szkalisity A, Horvath P, Belevich I, Peränen J, Thiele C, Somerharju P, et al. 2019. Seipin facilitates triglyceride flow to lipid droplet and counteracts droplet ripening via endoplasmic reticulum contact. Dev Cell 50: 478–493.e9. 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santinho A, Salo VT, Chorlay A, Li S, Zhou X, Omrane M, Ikonen E, Thiam AR. 2020. Membrane curvature catalyzes lipid droplet assembly. Curr Biol 30: 2481–2494.e6. 10.1016/j.cub.2020.04.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senior AW, Evans R, Jumper J, Kirkpatrick J, Sifre L, Green T, Qin C, Žídek A, Nelson AWR, Bridgland A, et al. 2020. Improved protein structure prediction using potentials from deep learning. Nature 577: 706–710. 10.1038/s41586-019-1923-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirwi A, Hussain MM. 2018. Lipid transfer proteins in the assembly of apoB-containing lipoproteins. J Lipid Res 59: 1094–1102. 10.1194/jlr.R083451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smagris E, Gilyard S, BasuRay S, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. 2016. Inactivation of Tm6sf2, a gene defective in fatty liver disease, impairs lipidation but not secretion of very low density lipoproteins. J Biol Chem 291: 10659–10676. 10.1074/jbc.M116.719955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Mizrak A, Lee CW, Cicconet M, Lai ZW, Lu CH, Mohr SE, Farese RV, Walther TC. 2021. Identification of two pathways mediating protein targeting from ER to lipid droplets. bioRxiv 10.1101/2021.09.14.460330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soni KG, Mardones GA, Sougrat R, Smirnova E, Jackson CL, Bonifacino JS. 2009. Coatomer-dependent protein delivery to lipid droplets. J Cell Sci 122: 1834–1841. 10.1242/jcs.045849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone SJ, Myers HM, Watkins SM, Brown BE, Feingold KR, Elias PM, Farese RV Jr. 2004. Lipopenia and skin barrier abnormalities in DGAT2-deficient mice. J Biol Chem 279: 11767–11776. 10.1074/jbc.M311000200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone SJ, Levin MC, Zhou P, Han J, Walther TC, Farese RV Jr. 2009. The endoplasmic reticulum enzyme DGAT2 is found in mitochondria-associated membranes and has a mitochondrial targeting signal that promotes its association with mitochondria. J Biol Chem 284: 5352–5361. 10.1074/jbc.M805768200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui X, Arlt H, Brock KP, Lai ZW, DiMaio F, Marks DS, Liao M, Farese RV Jr, Walther TC. 2018. Cryo-electron microscopy structure of the lipid droplet-formation protein seipin. J Cell Biol 217: 4080–4091. 10.1083/jcb.201809067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui X, Wang K, Gluchowski NL, Elliott SD, Liao M, Walther TC, Farese RV Jr. 2020. Structure and catalytic mechanism of a human triacylglycerol-synthesis enzyme. Nature 581: 323–328. 10.1038/s41586-020-2289-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski KM, Binns D, Bartz R, Grishin NV, Li WP, Agarwal AK, Garg A, Anderson RG, Goodman JM. 2007. The lipodystrophy protein seipin is found at endoplasmic reticulum lipid droplet junctions and is important for droplet morphology. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 20890–20895. 10.1073/pnas.0704154104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira V, Johnsen L, Martínez-Montañés F, Grippa A, Buxó L, Idrissi FZ, Ejsing CS, Carvalho P. 2018. Regulation of lipid droplets by metabolically controlled Ldo isoforms. J Cell Biol 217: 127–138. 10.1083/jcb.201704115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunyasuvunakool K, Adler J, Wu Z, Green T, Zielinski M, Žídek A, Bridgland A, Cowie A, Meyer C, Laydon A, et al. 2021. Highly accurate protein structure prediction for the human proteome. Nature 596: 590–596. 10.1038/s41586-021-03828-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine WJ, Hashidate-Yoshida T, Yamamoto S, Shindou H. 2020. Biosynthetic enzymes of membrane glycerophospholipid diversity as therapeutic targets for drug development. Adv Exp Med Biol 1274: 5–27. 10.1007/978-3-030-50621-6_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance JE. 2015. Phospholipid synthesis and transport in mammalian cells. Traffic 16: 1–18. 10.1111/tra.12230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancura A, Haldar D. 1994. Purification and characterization of glycerophosphate acyltransferase from rat liver mitochondria. J Biol Chem 269: 27209–27215. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)46970-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Horn CG, Caviglia JM, Li LO, Wang S, Granger DA, Coleman RA. 2005. Characterization of recombinant long-chain rat acyl-CoA synthetase isoforms 3 and 6: identification of a novel variant of isoform 6. Biochemistry 44: 1635–1642. 10.1021/bi047721l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CW, Miao YH, Chang YS. 2014. Control of lipid droplet size in budding yeast requires the collaboration between Fld1 and Ldb16. J Cell Sci 127: 1214–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Becuwe M, Housden BE, Chitraju C, Porras AJ, Graham MM, Liu XN, Thiam AR, Savage DB, Agarwal AK, et al. 2016. Seipin is required for converting nascent to mature lipid droplets. eLife 5: e16582. 10.7554/eLife.16582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Idrissi FZ, Hermansson M, Grippa A, Ejsing CS, Carvalho P. 2018. Seipin and the membrane-shaping protein Pex30 cooperate in organelle budding from the endoplasmic reticulum. Nat Commun 9: 2939. 10.1038/s41467-018-05278-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Qian H, Nian Y, Han Y, Ren Z, Zhang H, Hu L, Prasad BVV, Laganowsky A, Yan N, et al. 2020. Structure and mechanism of human diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 1. Nature 581: 329–332. 10.1038/s41586-020-2280-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Wu L, Chen J, Dong L, Chen C, Wen Z, Hu J, Fleming I, Wang DW. 2021. Metabolism pathways of arachidonic acids: mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther 6: 94. 10.1038/s41392-020-00443-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss SB, Kennedy EP, Kiyasu JY. 1960. The enzymatic synthesis of triglycerides. J Biol Chem 235: 40–44. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)69581-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel AA, Cooper DE, Ilkayeva OR, Muoio DM, Coleman RA. 2013. Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase (GPAT)-1, but not GPAT4, incorporates newly synthesized fatty acids into triacylglycerol and diminishes fatty acid oxidation. J Biol Chem 288: 27299–27306. 10.1074/jbc.M113.485219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfling F, Wang H, Haas JT, Krahmer N, Gould TJ, Uchida A, Cheng JX, Graham M, Christiano R, Fröhlich F, et al. 2013. Triacylglycerol synthesis enzymes mediate lipid droplet growth by relocalizing from the ER to lipid droplets. Dev Cell 24: 384–399. 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner EL, Tow B, Buhman KK, Wilson M, Sanan DA, Rudel LL, Farese RV Jr. 2003. Deficiency of acyl CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase 2 prevents atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 1262–1267. 10.1073/pnas.0336398100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolinski H, Hofbauer HF, Hellauer K, Cristobal-Sarramian A, Kolb D, Radulovic M, Knittelfelder OL, Rechberger GN, Kohlwein SD. 2015. Seipin is involved in the regulation of phosphatidic acid metabolism at a subdomain of the nuclear envelope in yeast. Biochim Biophys Acta 1851: 1450–1464. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2015.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita H, Takenoshita M, Sakurai M, Bruick RK, Henzel WJ, Shillinglaw W, Arnot D, Uyeda K. 2001. A glucose-responsive transcription factor that regulates carbohydrate metabolism in the liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci 98: 9116–9121. 10.1073/pnas.161284298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan R, Qian H, Lukmantara I, Gao M, Du X, Yan N, Yang H. 2018. Human SEIPIN binds anionic phospholipids. Dev Cell 47: 248–256.e4. 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A, Mottillo EP. 2020. Adipocyte lipolysis: from molecular mechanisms of regulation to disease and therapeutics. Biochem J 477: 985–1008. 10.1042/BCJ20190468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Bard M, Bruner DA, Gleeson A, Deckelbaum RJ, Aljinovic G, Pohl TM, Rothstein R, Sturley SL. 1996. Sterol esterification in yeast: a two-gene process. Science 272: 1353–1356. 10.1126/science.272.5266.1353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J, Li JZ, Liu Y, Li X, Yang T, Ma X, Li Q, Yao Z, Li P. 2009. Cideb, an ER- and lipid droplet-associated protein, mediates VLDL lipidation and maturation by interacting with apolipoprotein B. Cell Metab 9: 177–190. 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen CL, Monetti M, Burri BJ, Farese RV Jr. 2005. The triacylglycerol synthesis enzyme DGAT1 also catalyzes the synthesis of diacylglycerols, waxes, and retinyl esters. J Lipid Res 46: 1502–1511. 10.1194/jlr.M500036-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen CL, Stone SJ, Koliwad S, Harris C, Farese RV Jr. 2008. Thematic review series: glycerolipids. DGAT enzymes and triacylglycerol biosynthesis. J Lipid Res 49: 2283–2301. 10.1194/jlr.R800018-JLR200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama C, Wang X, Briggs MR, Admon A, Wu J, Hua X, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. 1993. SREBP-1, a basic-helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper protein that controls transcription of the low density lipoprotein receptor gene. Cell 75: 187–197. 10.1016/S0092-8674(05)80095-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SG. 1990. Recent progress in understanding apolipoprotein B. Circulation 82: 1574–1594. 10.1161/01.CIR.82.5.1574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu XG, Nicholson Puthenveedu S, Shen Y, La K, Ozlu C, Wang T, Klompstra D, Gultekin Y, Chi J, Fidelin J, et al. 2019. CHP1 regulates compartmentalized glycerolipid synthesis by activating GPAT4. Mol Cell 74: 45–58.e7. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.01.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann R, Strauss JG, Haemmerle G, Schoiswohl G, Birner-Gruenberger R, Riederer M, Lass A, Neuberger G, Eisenhaber F, Hermetter A, et al. 2004. Fat mobilization in adipose tissue is promoted by adipose triglyceride lipase. Science 306: 1383–1386. 10.1126/science.1100747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]