Abstract

Xenotransplantation research has made considerable progress in recent years, largely through the increasing availability of pigs with multiple genetic modifications. We suggest that a pig with nine genetic modifications (ie, currently available) will provide organs (initially kidneys and hearts) that would function for a clinically valuable period of time, for example, >12 months, after transplantation into patients with end-stage organ failure. The national regulatory authorities, however, will likely require evidence, based on in vitro and/or in vivo experimental data, to justify the inclusion of each individual genetic modification in the pig. We provide data both from our own experience and that of others on the advantages of pigs in which (a) all three known carbohydrate xenoantigens have been deleted (triple-knockout pigs), (b) two human complement-regulatory proteins (CD46, CD55) and two human coagulation-regulatory proteins (thrombomodulin, endothelial cell protein C receptor) are expressed, (c) the anti-apoptotic and “anti-inflammatory” molecule, human hemeoxygenase-1 is expressed, and (d) human CD47 is expressed to suppress elements of the macrophage and T-cell responses. Although many alternative genetic modifications could be made to an organ-source pig, we suggest that the genetic manipulations we identify above will all contribute to the success of the initial clinical pig kidney or heart transplants, and that the beneficial contribution of each individual manipulation is supported by considerable experimental evidence.

Keywords: clinical, genetically engineered, heart, human, kidney, pig, transgenes, triple-knockout, xenotransplantation

1 |. INTRODUCTION

With the increasingly encouraging results being achieved in pig-to-non-human primate (NHP) organ transplantation models, particularly of kidney and heart xenotransplantation,1–6 initial limited clinical trials in carefully selected patients with end-stage organ failure are drawing closer. With an increasing array of genetically engineered pigs becoming available, the question can be raised as to which combination of genetic modifications will be either optimal or necessary for an initial clinical trial.

We and others have suggested that pigs in which all three of the known carbohydrate xenoantigens against which humans have natural (preformed) xenoantibodies, namely galactose-α1,3-galactose [Gal], N-glycolylneuraminic acid [Neu5Gc], and Sda (the product of the enzyme, β-1,4-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase; ie, a triple-knockout [TKO] pig) should form the basis for any clinical trial, but that the additional expression of several human transgenic proteins would be beneficial. These include human complement-regulatory proteins (hCRPs), for example, CD46, CD55, CD59, and human coagulation-regulatory proteins, for example, thrombomodulin (TBM), endothelial cell protein C receptor (EPCR), tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI), CD39.

Although under ideal circumstances (eg, in the absence of ischemia-reperfusion injury, inflammation, or infection), the absence of natural antibody binding to the pig organ’s vascular endothelial cells may be sufficient to prevent activation of those cells or of the complement and/or coagulation cascades, the added protection provided by these human transgenes would seem advantageous, and possibly essential.

As our group has demonstrated a sustained inflammatory response after pig artery patch or organ transplantation in immunosuppressed baboons, the expression of a human protein that protects against the effects of inflammation, for example, hemeoxygenase-1 (HO-1) or A20, is also likely to be beneficial. Finally, expression of CD47 may have several advantages as there is increasing evidence that it reduces macrophage/monocyte, and possibly T-cell, activity. We therefore suggest that a pig with the above nine genetic manipulations (TKO.hCD46.hCD55.hTBM.hEPCR.hHO-1.hCD47) may be optimal in 2018 as the source of kidneys and hearts for clinical trials of xenotransplantation. Alternative human transgenes are available, but most of our experience is in pigs expressing one or more of the above genetic manipulations.

Although there are many other genetic manipulations that could be considered, some of which are aimed to protect against the human adaptive immune response, for example, swine leukocyte antigen (SLA) class I-knockout,7,8 SLA class II knockdown,9–11 transgenic expression of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4-immunoglobulin (CTLA4-Ig)12,13 or programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1),14–16 our opinion is that, although they are likely to be beneficial, they are not as important at this early stage in the development of xenotransplantation as manipulations that protect against the innate immune response. Although they will be advantageous in the near future, at present there are immunosuppressive agents (admittedly not all yet approved by national regulatory authorities) that can effectively prevent the adaptive response, for example, anti-CD40 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs).1–4,17,18 In our opinion, it is in controlling the innate immune response where genetic engineering of the pig has proved essential.

We have therefore suggested that a TKO pig that expresses two hCRPs (CD46 and CD55), two human coagulation-regulatory proteins (thrombomodulin, EPCR), human hemeoxygenase-1 (hHO-1), and hCD47 should be sufficient to ensure pig kidney or heart graft survival for a clinically valuable period of time, for example, >12 months, as long as the adaptive immune response could be satisfactorily controlled by a clinically well-tolerated immunosuppressive regimen. However, we would stress that the suggested combination may not be ideal for every xenogeneic organ, and that there are currently no reports of in vivo studies to support our opinion.

The national regulatory authorities, however, will almost certainly expect to be provided with evidence to justify the inclusion of each individual genetic modification. We here address this important point by providing our own personal opinion as a basis for further discussion. Although, with further experience, all nine of these modifications may not be proven to be absolutely essential (or may possibly even be detrimental), we believe there is evidence at the present time to indicate or suggest that all are beneficial, and will contribute to the success of the transplant.

2 |. GENETIC ENGINEERING APPROACH TO MULTIPLE GENE MANIPULATIONS

It is not our intention here to describe in detail the techniques that have been used in producing pigs with multiple genetic manipulations. In brief, however, multi-gene pigs with nine genetic modifications were generated via somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT; cloning) using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology. Fetal fibroblasts used as the starting material were homozygous knockout at the Gal locus (GTKO). Two loci (Gal and CMAH) were targeted for introduction of CD46/CD55 (2-gene vector to the CMAH locus) and TBM, EPCR, CD47, HO-1 (4-gene vector to the Gal locus). Genes in vector constructs were linked by 2A peptide sequences for multi-gene expression from either the constitutive CAG promoter (CD46, CD55, CD47, HO-1) or the endothelium-specific porcine ICAM-2 promoter (TBM, EPCR). Targeted integration of these vectors was achieved with homologous Gal or CMAH sequences flanking the transgene constructs, in combination with CRISPR/cas9 guides specific for integration at the Gal or the CMAH locus. β4GalNT2 knockout was achieved with β4Gal-specific CRISPR/Cas9 co-transfection, simultaneous with the CMAH-targeted CD46.CD55 vector.

Triple-knockout status (TKO = GTKO, CMAHKO, β4GalNT2-KO) and precise transgene integration (CD46, CD55) were confirmed by MiSeq DNA sequencing and PCR in fetuses (TKO + CD46, CD55 [5-gene]) derived from the initial SCNT pregnancies. Fetal fibroblasts from a fully confirmed 5-gene fetus were further transfected with the 4-gene vector (Gal targeted TBM.EPCR.CD47.HO1), single-cell cloned and analyzed for all precise modifications, then used for a second round of SCNT that resulted in the production of viable 9-gene offspring. Expression of all 6 transgenes was confirmed in cells from these 9GE pigs, as well as in organs (heart, lung, kidney, liver). Functional knockout (null phenotype) was also confirmed by flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry at all three knockout loci.

3 |. DELETION OF THE THREE KNOWN CARBOHYDRATE XENOANTIGENS (TKO PIGS)

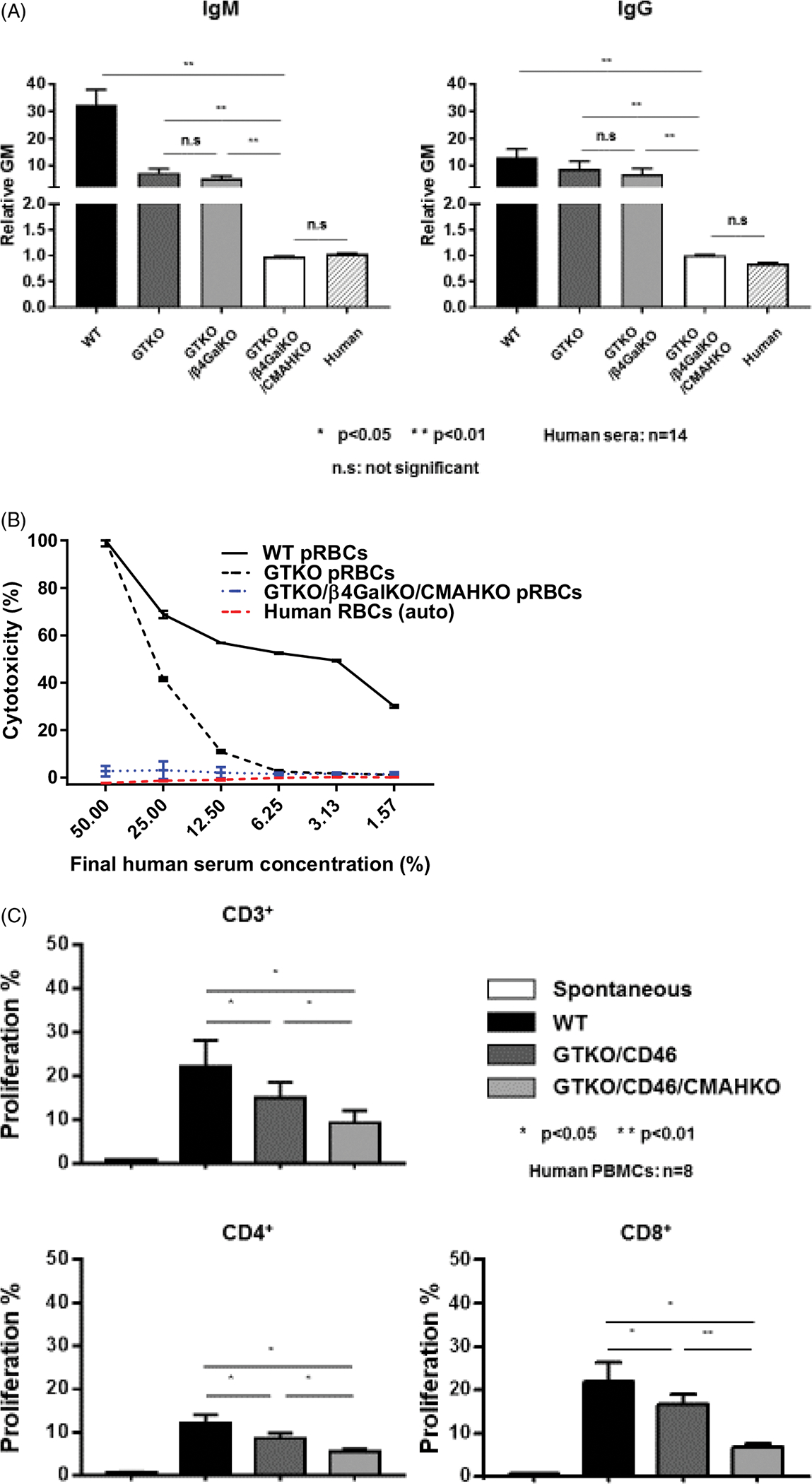

The deletion of expression of the major pig xenoantigen (Gal) by knockout of α1,3-galactosyltransferase in 2003 (GTKO)19–22 was a major advance in xenotransplantation. It resulted in a significant increase in pig heterotopic (non-life–supporting) heart graft survival in baboons23,24 and a less impressive, but nevertheless encouraging, survival of life-supporting pig kidney grafts.25 Subsequently, the identification of two other carbohydrate xenoantigens in pigs26–28 and their knockout29,30 were other major steps forward. Although transplants of TKO pig organs have not yet been tested in NHPs, there is increasing in vitro data indicating that TKO pig organs will prove to be a major advance on GTKO organs. This advantage will not only be related to the absence of antibody binding to, and serum cytotoxicity of, the pig vascular endothelial cells (Figure 1A,B), but also to reducing the T-cell response to the organ (Figure 1C). The mechanism of how the T-cell proliferative response is reduced remains uncertain, but is probably associated with a reduction in the overall xenoantigen load.

FIGURE 1.

A, Human IgM (left) and IgG (right) antibody binding to wild-type (WT), GTKO, double-knockout (DKO, ie, KO of Gal and Sda), and TKO pig red blood cells (RBCs). Human serum antibody binding to pRBCs (n = 14) was measured by flow cytometry using the relative geometric mean (GM), which was calculated by dividing the GM value for each sample by the negative control, as previously described (refs31,110). Negative controls were obtained by incubating the cells with secondary anti-human antibodies only (with no serum). Binding to TKO pig RBCs was not significantly different from human IgM and IgG binding to human RBCs of blood type O. (Note that our data support the observation that the deletion of β4GalNT2 has little effect in reducing antigenicity to humans, as opposed to baboons (Figure 2A) or New World monkeys (Figure 2B)). B, Pooled human serum complement-dependent cytotoxicity (hemolysis) to WT, GTKO, and TKO (GTKO/β4GalKO/CMAHKO) pig RBCs was performed, as previously described (ref111). Briefly, RBCs were incubated with diluted serum for 30 min at 37°C. After washing, RBCs were incubated with rabbit complement (Sigma; final concentration 20%) for 150 min at 37°C. After centrifugation, supernatant was collected, and hemolysis was evaluated using a Multi-Label Microplate Reader (Perkin Elmer Victor3). The absorbance of each sample at 541 nm was measured. Cytotoxicity of the same serum to autologous human O RBCs was tested as a control. C, Human T-cell proliferative response to WT, GTKO.hCD46, and GTKO.hCD46.CMAHKO (Neu5GcKO) pig peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in mixed leukocyte reaction (MLR; ref112). (TKO pig PBMCs were not available to us.)

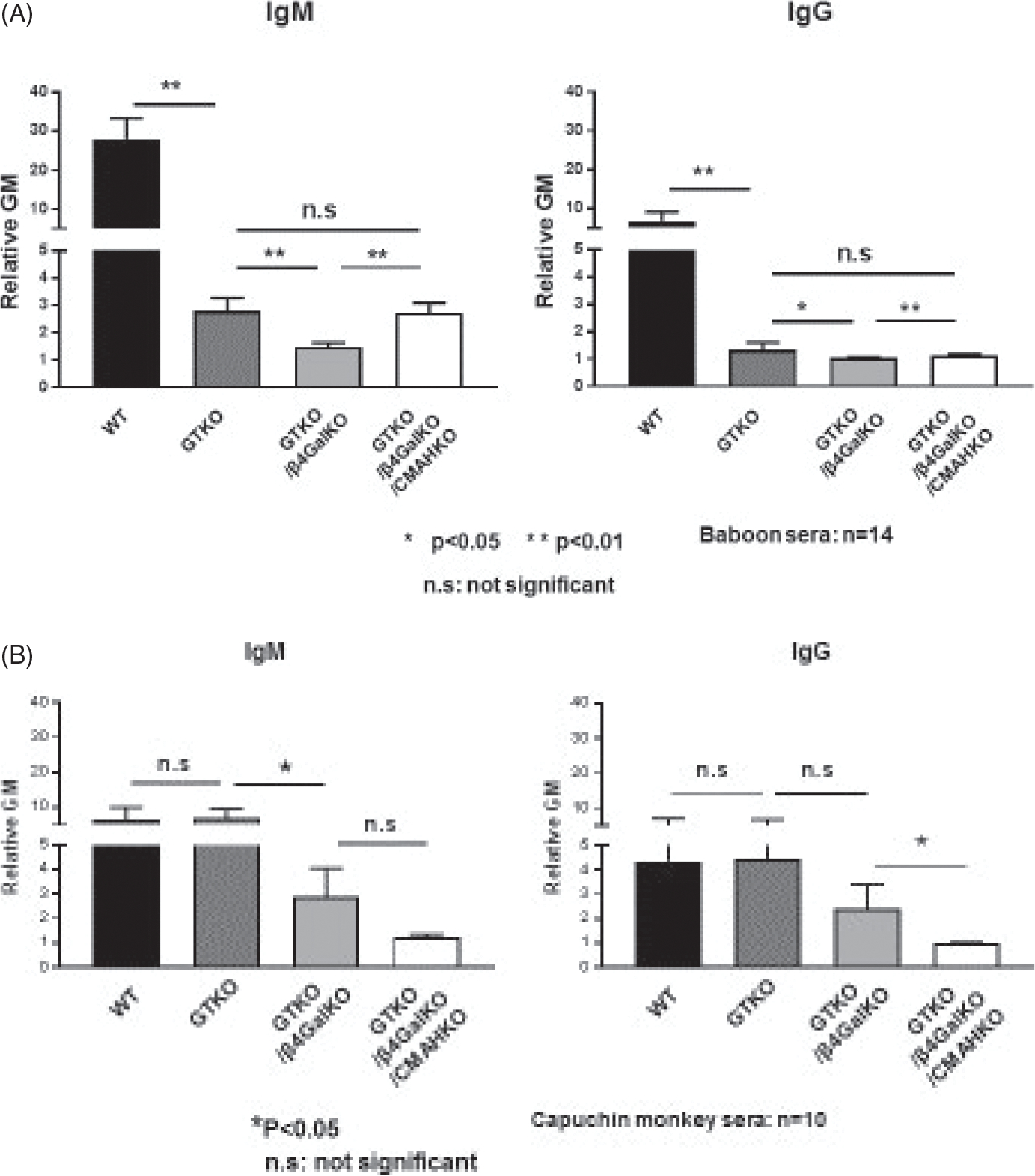

Testing in vivo has not yet been reported, in part because Old World NHPs express Neu5Gc and appear to have antibodies against a new target epitope exposed by TKO in the pig (sometimes referred to as the “4th xenoantigen”; Figure 2A).31 In this respect, New World monkeys would prove better surrogates for humans (Figure 2B),31 but the limited size of the majority of the available New World monkeys largely prohibits pig organ transplantation in these species. Nevertheless, there is evidence from experiments in which human blood has been perfused through pig lungs or livers ex vivo that deletion of expression of Neu5Gc reduces human anti-pig antibody binding and is beneficial to organ survival.32,33

FIGURE 2.

(A) Baboon (n = 14) and (B) capuchin monkey (a New World monkey) (n = 10) IgM and IgG antibody binding to WT, GTKO, DKO (KO of Gal and Sda), and TKO pig RBCs. Serum antibody binding to pig RBCs was performed, as previously described (ref31). (Note that CMAHKO in pig cells appears to expose a fourth xenoantigen against which Old World NHPs, but not New World monkeys, have natural antibodies. TKO pig organ transplantation in Old World NHPs may therefore be problematic and disadvantageous.)

Based on the in vitro data, grafts from TKO pigs should have a major survival advantage over those from single- or double-knockout pigs, and may therefore be fundamental to the success of clinical organ xenotransplantation. There is a difference of opinion on whether the insertion of human protective transgenes is necessary, with some believing that TKO alone will be sufficient. We would point out that in ABO-incompatible organ allotransplantation and in allotransplantation in the presence of anti-HLA antibodies (panel-reactive antibodies), the graft is to some extent protected by the expression of species-specific hCRPs, human coagulation-regulatory proteins, and human “anti-inflammatory” proteins on its cells. This is not the case after xenotransplantation where a small amount of natural antibody or of de novo antibody could have a much greater detrimental effect. An additional and even more important factor, of course, is that the complement and coagulation cascades can be activated by several factors that do not involve antibody.34

There must, however, be justification, based on in vitro and/or in vivo experimental evidence, for the introduction of human transgenes and, in the case of our suggested “9-gene” pigs, we believe this can be provided.

4 |. EXPRESSION OF HUMAN COMPLEMENT-REGULATORY PROTEINS

This genetic manipulation was among the earliest suggested35,36 and the first carried out in pigs and tested both in vitro and in vivo in NHP models.37–39 We therefore have considerable evidence for its beneficial effect.

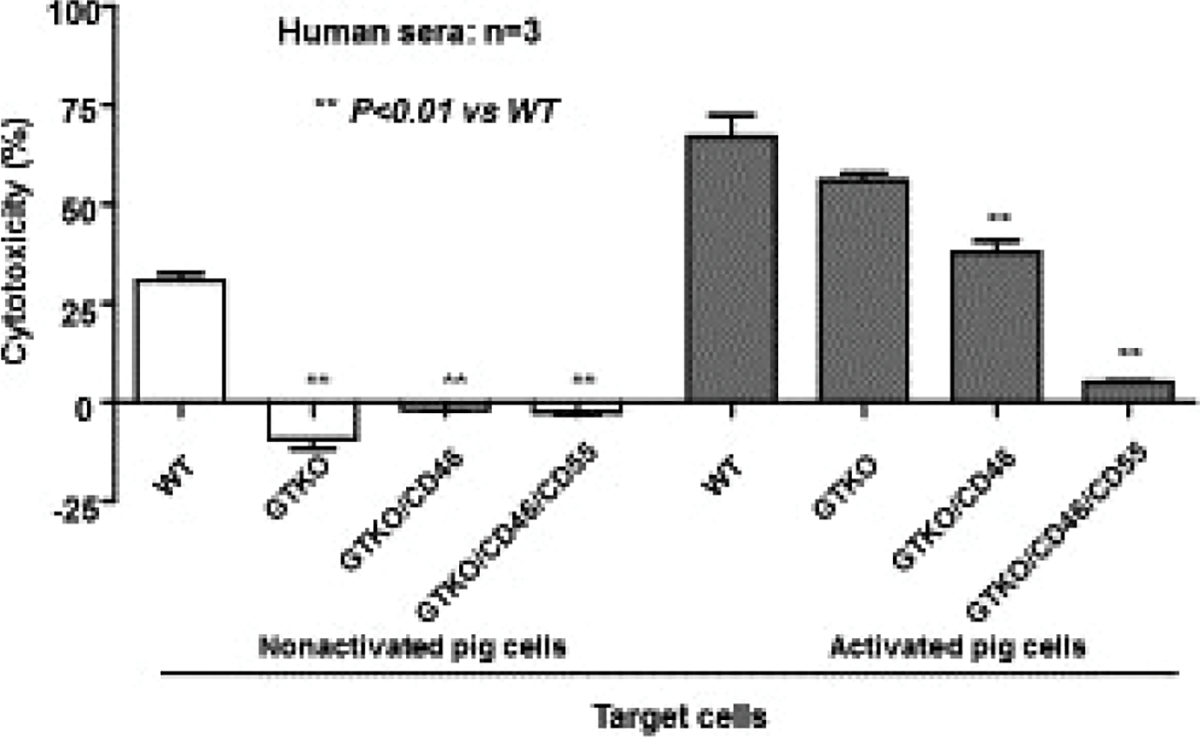

In vitro, transgenic expression of a single hCRP, for example, CD55 (decay-accelerating factor, DAF) or CD46 (membrane cofactor protein, MCP), is associated with a significant reduction in cytotoxicity of pig cells exposed to human serum (Figure 3).40 Expression of CD46 or CD55 appears to be equally effective, and there is evidence that expression of both transgenes is preferable to one alone (Figure 3).41,42

FIGURE 3.

Human serum cytotoxicity to WT, GTKO, GTKO. hCD46, and GTKO.hCD46.hCD55 pig corneal endothelial cells both before (left) and after (right) activation with pig IFN-γ (ref113). Before activation, there was no serum cytotoxicity to GTKO, GTKO/CD46, or GTKO/CD46/CD55 pig cells. After activation, serum cytotoxicity was significantly increased, but the expression of two human complement-regulatory proteins (CD46 and CD55) almost completely prevented cytotoxicity

In vivo, early studies by White, Cozzi, and their colleagues provided considerable evidence that, in NHPs, transplants of pig hearts and kidneys expressing hCD55 survived significantly longer than organs from wild-type (ie, genetically unmodified) pigs (reviewed in43,44). The graft survival achieved was similar to that later achieved by the transplantation of GTKO pig organs that did not express a hCRP.23–25 For example, hCD55-transgenic pig kidney survival reached a maximum of 90 days,45,46 comparable to that of GTKO pig kidney of 83 days.25 Although one GTKO pig heart graft functioned for 179 days, survival of the majority of heart grafts between those protected by GTKO and those protected by hCD55 was similar.43,44

When the two genetic modifications were combined, for example, GTKO.CD46 grafts, there was evidence that early graft failure was reduced further.47–49 There are, however, potential complications from the expression of hCRPs, such as susceptibility to human infectious agents. Human complement regulators are used by many pathogens as co-receptors to enter host cells42 and evade host immunity,50,51 or as a receptor of toxins produced by the pathogens.52 There is, therefore, the potential that a pig expressing one or more hCRPs might be at a higher risk for infection, particularly of the graft itself, though there do not appear to be any reports in this respect in preclinical models. Pigs expressing high levels of one (hCD46) or both hCRPs (hCD46 and hCD55) have been generated and replicated over two decades, with no evidence of higher risk of infections for the pigs or organs derived therefrom (D. Ayares, unpublished data).

There are, of course, therapeutic agents that could be administered to the recipient of a xenograft that can deplete or inhibit complement, but some of these are not clinically applicable, for example, cobra venom factor, and others very expensive, for example eculizumab. More importantly, the sustained systemic depletion or inhibition of complement risks infectious complications, whereas the local protection afforded by expression of a hCRP on the graft is safer in this respect.

5 |. EXPRESSION OF HUMAN COAGULATION-REGULATORY PROTEINS

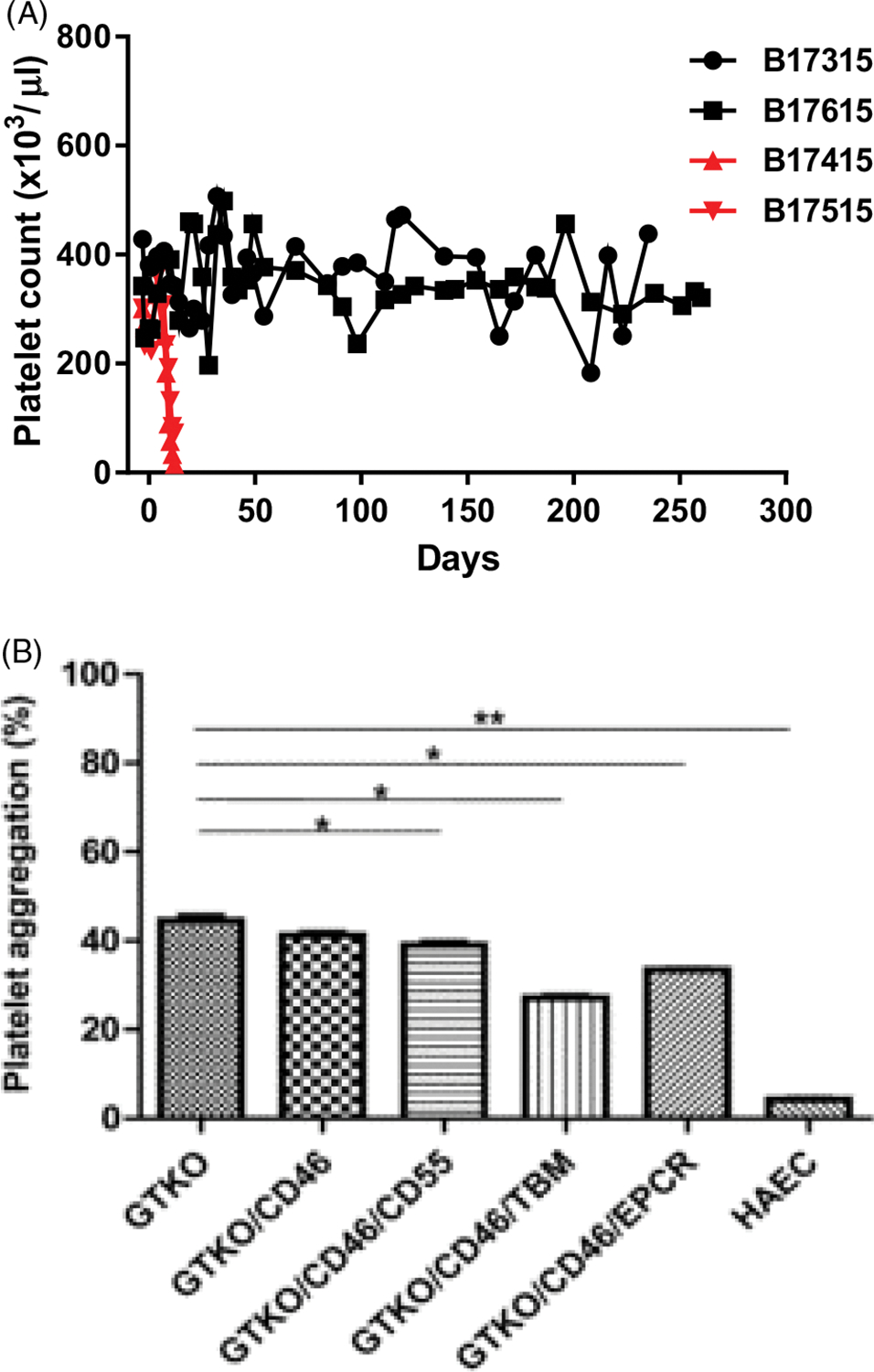

Nevertheless, despite the above progress, most pig grafts failed from the development of thrombotic microangiopathy in the graft,53–56 which could lead to the onset of consumptive coagulopathy in the recipient (Figure 4A). This complication is believed to be secondary to a low level of antibody binding to, or complement deposition on, the graft vascular endothelium, and so is, at least in part, immune-mediated. Systemic anticoagulation of the recipient (eg, with heparin, low molecular weight heparin, warfarin) or by the administration of anti-platelet agents (eg, aspirin, clopidogrel) was largely unsuccessful in preventing this complication,57–59 but the transplantation of an organ from a GTKO.hCD46 pig that additionally expressed a human coagulation-regulatory protein made a significant difference (Figure 4A) (reviewed in60).

FIGURE 4.

A, Rapid development of thrombocytopenia (consumptive coagulopathy) in two baboons with life-supporting GTKO.hCD46 pig kidney grafts (indicated in red), and maintenance of normal platelet counts in two baboons (treated identically) with life-supporting GKTO.hCD46.hTBM pig kidney grafts (indicated in black). (Modified from Iwase H et al, ref4). B, Results of human platelet aggregation assay when human platelets were co-incubated with WT, GTKO.hCD46, GTKO.hCD46.hCD55, GTKO.hCD46. hTBM, and GTKO.hCD46.hEPCR pig aortic endothelial cells (AECs). Human platelet aggregation when exposed to human AECs is shown as a control. (Reproduced with permission from Iwase et al, ref61)

In vitro, cells from GTKO.CD46 pigs that also expressed TBM or EPCR were associated with reduced platelet aggregation in a platelet aggregation assay (Figure 4B).61

In vivo, Mohiuddin and his colleagues reported several heterotopic (non-life–supporting) heart grafts from GTKO.hCD46.hTBM functioning for more than a year.1,2 Recently, 6-month survival of genetically identical pig grafts placed orthotopically in baboons has been reported by the Munich group.62 Life-supporting pig kidney grafts have also functioned for several months in the absence of any features of rejection, thrombotic microangiopathy, or consumptive coagulopathy (Figure 4A) (with the recipients eventually requiring euthanasia for opportunistic systemic infections, but not for immune injury to the grafts).3,4. However, in our personal experience, expression of one or more human coagulation-regulatory proteins may not protect the pig kidney when the immunosuppressive therapy administered is inadequate. In this respect, a costimulation-based immunosuppressive therapy appears to be more effective than conventional immunosuppressive therapy.17

In addition to its anticoagulant effect, TBM also has an anti-inflammatory function (see below).63 One intriguing and possibly important observation made in vitro has been that, whereas the expression of native pig TBM is downregulated during inflammation, thus reducing its protection against coagulation dysregulation and inflammation, expression of transgenic hTBM is not downregulated,64 thus maintaining both of its beneficial functions.

As with the complement cascade, there are several agents that can induce a state of anticoagulation in the recipient of a pig graft or reduce platelet activation/aggregation, but these have generally proved unsuccessful in preventing a thrombotic microangiopathy from developing (see above). Furthermore, avoiding systemic anticoagulation would be an advantage.

The transgenic expression of hCRPs and human coagulation-regulatory proteins has now been extensively tested in vitro and in vivo, and their beneficial effects in xenotransplantation have been demonstrated. Expression of these human transgenes together with deletion of the three known carbohydrate xenoantigens may alone be sufficient to enable long-term survival of a pig heart or kidney to be obtained. There are other human transgenes, however, that have been included in pigs with multiple genetic manipulations, where it has therefore been more difficult to demonstrate their individual specific benefit. These would include HO-1 and CD47.

6 |. EXPRESSION OF HUMAN HEMEOXYGENASE-1

There is increasing evidence for a sustained inflammatory response to a xenograft, which actually precedes the platelet aggregation that occurs in the graft and therefore may be a causative factor.65–68 The interaction between inflammation, coagulation, and the immune response is complex,69–74 but it is generally accepted that inflammation can greatly augment the immune response (Figure 3).

The benefits of HO-1 in transplantation are mediated by its strong anti-oxidative, anti-apoptotic, and anti-inflammatory effects.75 Other helpful functions of HO-1 are its ability to modulate the immune response, maintain microcirculation, facilitate angiogenesis, and inhibit platelet aggregation.76,77 The postulated mechanism of biological function of HO-1 is to degrade the deleterious accumulation of free heme, which leads to a suppressive effect on monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1).78 In addition, HO-1 mediates beneficial effects by degrading heme into three different biologically active molecules, carbon monoxide (CO), free iron (Fe2+), and biliverdin, which synergize in preventing disease progression and inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory agonists, which in turn inhibits inflammation, and reduces cytotoxicity.78,79 HO-1 expression is crucial in downregulating inflammatory responses in a variety of experimental systems.80

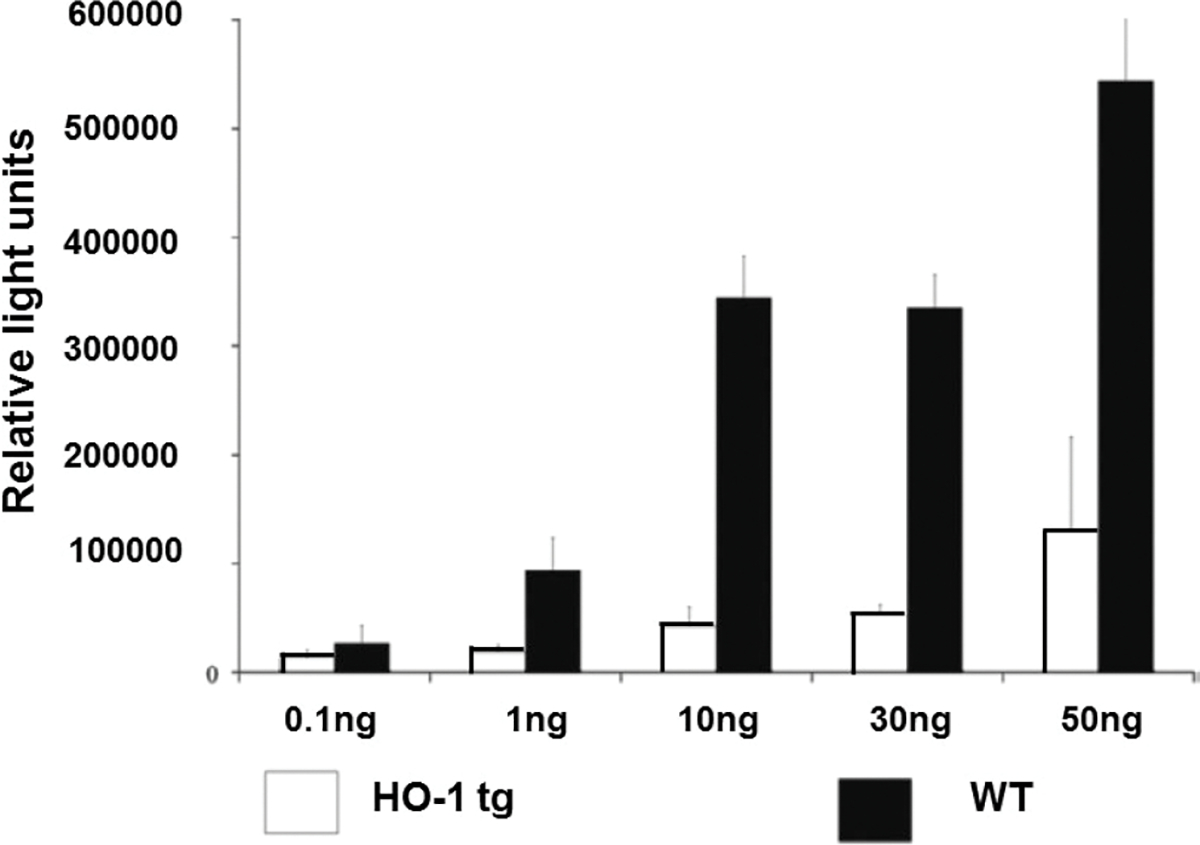

The protective effects of hHO-1 have been observed in cell-based in vitro experiments (Figure 5) and in animal experiments. For example, organs expressing HO-1 were shown to be critical for prolonged survival of mouse cardiac xenografts in rats,81,82 and expression of hHO-1 in pig islets (that are particularly sensitive to hypoxic stress and more prone to suffer ischemic injury) prolonged their survival in mice, and decreased immune cell infiltration and islet cell apoptosis.83 Although not all investigations have demonstrated a benefit from expression of hHO-1, the majority of the data indicate that its expression could be an important factor when designing multi-transgenic pigs for clinical xenotransplantation.

FIGURE5.

Human hemeoxygenase-1 (hHO-1) transgenic pig aortic endothelial cells (PAEC) are protected against TNF-α–mediated apoptosis, measured by a caspase 3/7 assay. PAECs from hHO-1 transgenic pigs were better protected against TNF-α–mediated apoptosis compared to WT PAEC. (Modified from, and with the courtesy of, Petersen et al, ref114)

7 |. EXPRESSION OF HCD47

Fortunately, in some cases, genetic engineering of the organ-source pigs directed toward protection from the innate immune response also reduces the adaptive immune response (Figure 1C).84 Even the expression of a hCRP appears to reduce the T-cell response to the graft.85 Nevertheless, there are other approaches that may reduce the innate and inflammatory responses and thus reduce the adaptive response further.

Several groups have reported that innate immune cell activation results from a combination of (a) xenoantigen recognition by activating receptors, and (b) incompatibility of inhibitory receptor-ligand interactions, and that innate immune cells can be activated by xenografts in the absence of antibodies.86–89 Furthermore, the innate response to a xenograft may persist even when the adaptive response has been suppressed.

Macrophages play an important role in innate cell xenograft rejection, and activated macrophages contribute to cellular xenograft rejection by direct toxicity (eg, by the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines) or indirectly by contributing to the amplification of the T-cell response. Therefore, regulation of macrophages should improve xenograft survival. One strategy toward this aim is to produce pigs transgenic for hCD47.87

CD47 is well-known as a negative-regulator of macrophages.90 It is expressed in many cells, including erythrocytes, hematopoietic cells, platelets, and endothelial cells. Its ligation to the signal regulatory protein-alpha (SIRP-α) on macrophages or antigen-presenting cells phosphorylates SIRP-α and leads to suppression of macrophage-mediated autologous phagocytosis as a marker of self.91 SIRP-α, therefore, inhibits monocyte/macrophage-mediated phagocytosis when it identifies species-specific CD47.86,92

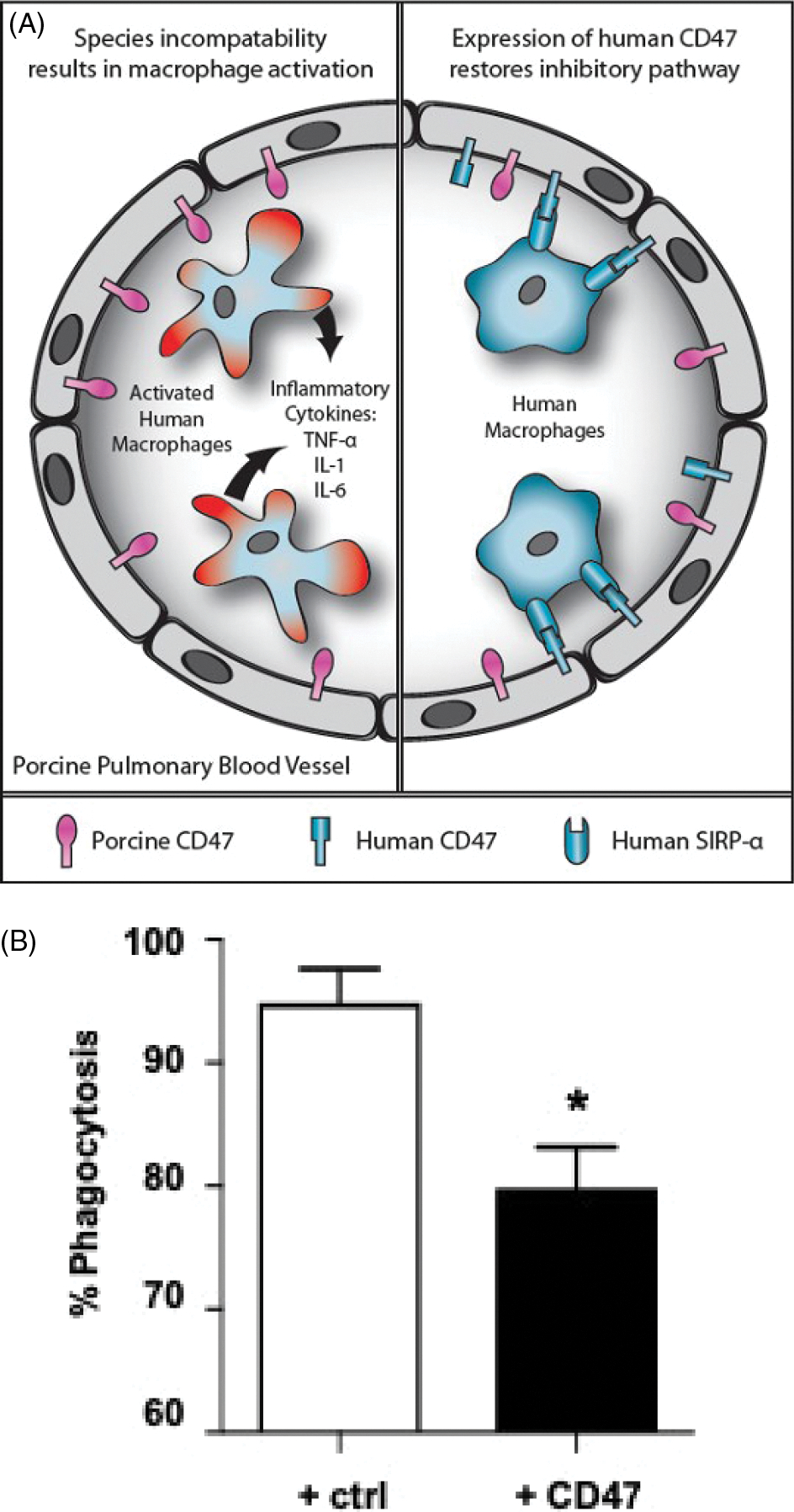

Although we are greatly simplifying a complex topic93,94 (eg, because SIRP-α is polymorphic whereas CD47 is monomorphic), pig CD47 is not recognized by primate SIRP-α as self, and therefore, macrophages are activated against the graft (Figure 6A). Transfection of cells with the gene for CD47 from the same species as the recipient macrophages prevents phagocytosis by activation of SIRP-α in both mouse92 and human86 models. In our own laboratories, transgenic pigs that express hCD47 have been generated in an effort to prevent macrophage activation. Although hCD47 was expressed on pig cells in combination with other genetic manipulations, in vitro evidence for a significant reduction in phagocytosis was obtained (Figure 6B), which we attributed largely to the expression of hCD47.

FIGURE 6.

A, Schematic representation of CD47-SIRP-α interaction in relation to natural expression of SIRP-α on human macrophages. Left: After transplantation of an unmodified pig lung into a human, the expression of pig CD47 on the endothelial cells of the pulmonary blood vessels will not be recognized by human SIRP-α–expressing macrophages, which will therefore not be inhibited but will become activated; inflammatory cytokines will be produced and graft injury will occur. Right: When a lung from a pig transgenic for human CD47 is transplanted, the human SIRP-α–expressing macrophages will recognize the pig tissues as “self,” and activation will be inhibited; cytokine production and graft injury will not occur. (Reproduced with permission from Cooper et al, 2012, ref115). B, Human (h) CD47 surface expression on pig aortic endothelial cells reduces phagocytosis. Labeled control (GTKO. CD46) pig endothelial cells (white bar) or hCD47-expressing pig endothelial cells (black bar) isolated from transgenic pigs were co-incubated with human macrophages derived from freshly isolated monocytes. High surface expression of CD47 was associated with a significant reduction in phagocytosis (measured by flow cytometry). Statistical comparisons were calculated using a paired T test (*P < 0.05)

Ide and his colleagues were among the first to demonstrate that human macrophages can phagocytose pig cells even in the absence of antibody or complement opsonization,86 and drew attention to the incompatibility of CD47. They verified that expression of human CD47 in pig cells reduced their phagocytosis by human macrophages.

In vitro, expression of hCD47 on pig cells not only suppresses the activation of human macrophages but, importantly, also suppresses inflammatory cytokine (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) production, and macrophage-mediated pig cell cytotoxicity.95,96 In addition, Yan et al have demonstrated that pig graft infiltration by human T cells is suppressed by expression of hCD47.96 Illustrating the complex interaction of the immune, coagulation, and inflammatory systems, when hCD47 was expressed with human tissue factor pathway inhibitor (hTFPI), hCD47-SIRP-α signaling was potentiated.95

In vivo evidence of the beneficial effect of expression of hCD47 in pigs has also been demonstrated but, like hHO-1, it has usually been expressed in pigs in combination with several other human transgenes, making it difficult to determine its individual effect. However, the survival of pig skin grafts in baboons was extended if the grafts expressed hCD47,97 and the transgenic expression of hCD47 enhanced engraftment in an experimental model of pig-to-human hematopoietic cell transplantation.98 There is also a preliminary report that there is less proteinuria in baboons if a GTKO pig kidney graft expresses hCD47 and CD55.99

Nevertheless, expression of hCD47 in the pig, although important if hematopoietic progenitor cell transplantation forms part of the xenotransplantation protocol, may be less important—or even detrimental100—in solid organ xenotransplantation. This may be particularly so as macrophage activation may be stimulated in part by antibody binding to the target pig antigens. In the complete absence of antibody binding, for example, in the case of a TKO pig organ transplant, macrophages may play a weaker role in the response to the graft, but nevertheless will inhibit macrophage-mediated phagocytosis.

In summary, in particular in relation to pig cell transplantation, if not organ transplantation, there is increasing evidence that regulation of the recipient macrophage response through CD47-SIRP-α signaling by the generation of hCD47-transgenic pigs is a promising approach for improving xenograft survival.

8 |. COMMENT

It will be noted that we have not included any genetic engineering aimed at reducing activation or expression of porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERV),101–104 and that is because the risk of a pathogenic effect from PERV is now considered low.105 Furthermore, knockout of all of its copy numbers may well be detrimental to the pig cell, limiting the number of other genetic manipulations that can be made.

As problems related to the immune response are now being resolved, attention can be directed to whether pig organs will function normally in primate hosts. There have been few studies in this respect, but recent data indicate that some problems initially perceived to be related to physiological differences between pig and primate were in fact related to the effects of the immune response. When the immune response has been adequately controlled, organ function has remained largely normal.2,4,106

Although it is unlikely that all of the myriad products of a pig liver will be able to fulfill the requirements of a primate, the heart, kidney, and, to some degree, the lung are relatively simple organs in this respect. If any problems arise, they can be resolved by genetic engineering of the pig. The only potential problem (apart from rapid growth of the kidney4,106) that we have observed to date has been the possibility that pig renin (produced by the kidney) may be inadequate in primates.107 We have observed episodes of hypovolemia/dehydration in recipient baboons that we have documented might be associated with an abnormality in, or an absence of, renin function. If we are correct, the ultimate solution may be to genetically engineer the organ-source pig to produce human renin.

We suggest that the genetic manipulations we identify above will all contribute to the success of the initial clinical pig kidney or heart transplants, and that the beneficial contribution of each individual manipulation is supported by considerable experimental evidence. In the future, it is likely that manipulations such as SLA class I-knockout and/or SLA class II knockdown (by the introduction of a mutant CIITA gene), or the transgenic expression of CTLA4-Ig or PD-L1 will be introduced, thus enabling a reduction in the intensity of exogenous immunosuppressive therapy. Natural killer cells may also play a role in xenograft rejection, and here, again genetic engineering of the pig (to express HLA-E and/or G and/or Cw3) may prevent this.108 Indeed, expression of HLA-E has also been demonstrated to suppress macrophage-mediated cytotoxicity.109

However, for the initial clinical trials, the “9-gene” pig discussed above (or a similar pig) should be sufficient to allow clinically relevant prolonged graft survival.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Work on xenotransplantation at the University of Alabama at Birmingham is supported in part by NIH NIAID U19 grant AI090959, and by a grant from United Therapeutics.

Funding information

United Therapeutics Corporation, Grant/Award Number: 000511202-0001; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Grant/Award Number: U19AI090959

Abbreviations:

- CIITA

dominant-negative mutant major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II transactivator gene

- EPCR

endothelial cell protein C receptor

- Gal

galactose-α1,3-galactose

- GTKO

α1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout

- hCRP

human complement-regulatory protein

- HO-1

hemeoxygenase-1

- IL-6R

interleukin-6 receptor

- NHP

non-human primate

- PERV

porcine endogenous retrovirus

- TBM

thrombomodulin

- TKO

triple gene-knockout

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Elena Federzoni is an employee of United Therapeutics, and Amy Dandro and David Ayares are employees of Revivicor, Inc The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mohiuddin MM, Singh AK, Corcoran PC, et al. One-year heterotopic cardiac xenograft survival in a pig to baboon model. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:488–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohiuddin MM, Singh AK, Corcoran PC, et al. Chimeric 2C10R4 anti-CD40 antibody therapy is critical for long-term survival of GTKO.hCD46.hTBM pig-to-primate cardiac xenograft. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwase H, Liu H, Wijkstrom M, et al. Pig kidney graft survival in a baboon for 136 days: longest life-supporting organ graft survival to date. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:302–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwase H, Hara H, Ezzelarab M, et al. Immunological and physiological observations in baboons with life-supporting genetically engineered pig kidney grafts. Xenotransplantation. 2017;24(2):e12293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higginbotham L, Mathews D, Breeden CA, et al. Pre-transplant antibody screening and anti-CD154 costimulation blockade promote long-term xenograft survival in a pig-to-primate kidney transplant model. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:221–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams AB, Kim SC, Martens GR, et al. Xenoantigen deletion and chemical immunosuppression can prolong renal xenograft survival. Ann Surg. 2018;268(4):564–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reyes LM, Estrada JL, Wang ZY, et al. Creating class I MHC-null pigs using guide RNA and the Cas9 endonuclease. J Immunol. 2014;193:5751–5757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martens GR, Reyes LM, Butler JR, et al. Humoral reactivity of renal transplant-waitlisted patients to cells from GGTA1/CMAH/B4GalNT2, and SLA class I knockout pigs. Transplantation. 2017;101:e86–e92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hara H, Witt W, Crossley T, et al. Human dominant-negative class II transactivator transgenic pigs – effect on the human anti-pig T cell immune response and immune status. Immunology. 2013;140:39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwase H, Ekser B, Satyananda V, et al. Initial in vivo experience of pig artery patch transplantation in baboons using mutant MHC (CIITA-DN) pigs. Transpl Immunol. 2015;32:99–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ladowski JM, Reyes LM, Martens GR, et al. Swine leukocyte antigen class II is a xenoantigen. Transplantation. 2018;102:248–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phelps CJ, Ball SF, Vaught TD, et al. Production and characterization of transgenic pigs expressing porcine CTLA4-Ig. Xenotransplantation. 2009;16:477–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klymiuk N, van Buerck L, Bahr A, et al. Xenografted islet cell clusters from INSLEA29Y transgenic pigs rescue diabetes and prevent immune rejection in humanized mice. Diabetes. 2012;61:1527–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeon D-H, Oh K, Oh BC, et al. Porcine PD-L1: cloning, characterization, and implications during xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2007;14:236–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plege A, Borns K, Beer L, Baars W, Klempnauer J, Schwinzer R. Downregulation of cytolytic activity of human effector cells by transgenic expression of human PD-ligand-1 on porcine target cells. Transpl Int. 2010;23:1293–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buermann A, Petkov S, Petersen B, et al. Pigs expressing the human inhibitory ligand PD-L1 (CD 274) provide a new source of xenogeneic cells and tissues with low immunogenic properties. Xenotransplantation. 2018;25(5):e12387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto T, Hara H, Foote J, et al. Life-supporting kidney xenotransplantation from genetically-engineered pigs in baboons: a comparison of two immunosuppressive regimens. Transplantation. 2019. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwase H, Ekser B, Satyananda V, et al. Pig-to-baboon heterotopic heart transplantation – exploratory preliminary experience with pigs transgenic for human thrombomodulin and comparison of three costimulation blockade-based regimens. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:211–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Good AH, Cooper D, Malcolm AJ, et al. Identification of carbohydrate structures that bind human antiporcine antibodies: implications for discordant xenografting in man. Transplant Proc. 1992;24:559–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper D, Koren E, Oriol R. Genetically engineered pigs. Lancet. 1993;342:682–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phelps CJ, Koike C, Vaught TD, et al. Production of alpha 1,3-galactosyltransferase-deficient pigs. Science (New York, NY). 2003;299:411–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kolber-Simonds D, Lai L, Watt SR, et al. Production of alpha-1,3-galactosyltransferase null pigs by means of nuclear transfer with fibroblasts bearing loss of heterozygosity mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:7335–7340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuwaki K, Tseng Y-L, Dor F, et al. Heart transplantation in baboons using α1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout pigs as donors: initial experience. Nat Med. 2005;11:29–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tseng YL, Kuwaki K, Dor FJ, et al. α1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout pig heart transplantation in baboons with survival approaching six months. Transplantation. 2005;80:1493–1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamada K, Yazawa K, Shimizu A, et al. Marked prolongation of porcine renal xenograft survival in baboons through the use of α1,3- galactosyltransferase gene-knockout donors and the cotransplantation of vascularized thymic tissue. Nat Med. 2005;11:32–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bouhours D, Pourcel C, Bouhours JE. Simultaneous expression by porcine aorta endothelial cells of glycosphingolipids bearing the major epitope for human xenoreactive antibodies (Gal alpha1–3Gal), blood group H determinant and N-glycolylneuraminic acid. Glycoconj J. 1996;13:947–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu A, Hurst R. Anti-N-glycolylneuraminic acid antibodies identified in healthy human serum. Xenotransplantation. 2002;9:376–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Byrne GW, Du Z, Stalboerger P, Kogelberg H, McGregor CG. Cloning and expression of porcine beta1,4 N-acetylgalactosaminyl Xenotransplantation. 2014;21:543–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lutz AJ, Li P, Estrada JL, et al. Double knockout pigs deficient in N-glycolylneuraminic acid and galactose alpha-1,3-galactose reduce the humoral barrier to xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2013;20:27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Estrada JL, Martens G, Li P, et al. Evaluation of human and non-human primate antibody binding to pig cells lacking GGTA1/CMAH/beta4GALNT2 genes. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:194–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Q, Shaikh S, Iwase H, et al. Carbohydrate antigen expression and anti-pig antibodies in New World capuchin monkeys: relevance to studies of xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2019;e12498. 10.1111/xen.12498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burdorf L, Azimzadeh AM, Pierson RN 3rd. Progress and challenges in lung xenotransplantation: an update. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2018;23:621–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cimeno A, French BM, Powell JM, et al. Synthetic liver function is detectable in transgenic porcine livers perfused with human blood. Xenotransplantation. 2018;25(1):e12361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ricklin D, Lambris JD. Complement in immune and inflammatory disorders: pathophysiological mechanisms. J Immunol. 2013;190:3831–3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dalmasso AP, Vercellotti GM, Platt JL, Bach FH. Inhibition of complement-mediated endothelial cell cytotoxicity by decay-accelerating factor. Potential for prevention of xenograft hyperacute rejection. Transplantation. 1991;52:530–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.White DJ, Oglesby T, Liszewski MK, et al. Expression of human decay accelerating factor or membrane cofactor protein genes on mouse cells inhibits lysis by human complement. Transpl Int. 1992;5(Suppl 1):S648–S650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fodor WL, Williams BL, Matis LA, et al. Expression of a functional human complement inhibitor in a transgenic pig as a model for the prevention of xenogeneic hyperacute organ rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11153–11157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.White D, Langford GA, Cozzi E, Young VK. Production of pigs transgenic for human DAF: a strategy for xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 1995;2:213–217. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cozzi E, White DJ. The generation of transgenic pigs as potential organ donors for humans. Nat Med. 1995;1:964–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hara H, Long C, Lin YJ, et al. In vitro investigation of pig cells for resistance to human antibody-mediated rejection. Transpl Int. 2008;21:1163–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyagawa S, Shirakura R, Iwata K, et al. Effects of transfected complement regulatory proteins, MCP, DAF, and MCP.DAF hybrid, on complement-mediated swine endothelial cell lysis. Transplantation. 1994;58:834–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miyagawa S, Yamamoto A, Matsunami K, et al. Complement regulation in the GalT KO era. Xenotransplantation. 2010;17:11–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lambrigts D, Sachs DH, Cooper D. Discordant organ xenotransplantation in primates – world experience and current status. Transplantation. 1998;66:547–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cooper D, Satyananda V, Ekser B, et al. Progress in pig-to-nonhuman primate transplantation models (1998–2013): a comprehensive review of the literature. Xenotransplantation. 2014;21:397–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cozzi E, Vial C, Ostlie D, et al. Maintenance triple immunosuppression with cyclosporin A, mycophenolate sodium and steroids allows prolonged survival of primate recipients of hDAF porcine renal xenografts. Xenotransplantation. 2003;10:300–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baldan N, Rigotti P, Calabrese F, et al. Ureteral stenosis in HDAF pig-to-primate renal xenotransplantation: a phenomenon related to immunological events? Am J Transplant. 2004;4:475–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Azimzadeh A, Kelishadi S, Ezzelarab M, et al. Early graft failure of GTKO pig organs in baboons is reduced in hCPRP expression. Xenotransplantation. 2009;16:356 (Abstract). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Azimzadeh AM, Kelishadi SS, Ezzelarab MB, et al. Early graft failure of GalTKO pig organs in baboons is reduced by expression of a human complement pathway-regulatory protein. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:310–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McGregor C, Ricci D, Miyagi N, et al. Human CD55 expression blocks hyperacute rejection and restricts complement activation in Gal knockout cardiac xenografts. Transplantation. 2012;93:686–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Agrawal P, Nawadkar R, Ojha H, Kumar J, Sahu A. Complement evasion strategies of viruses: an overview. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bennett KM, Rooijakkers SH, Gorham RD Jr. Let’s Tie the knot: marriage of complement and adaptive immunity in pathogen evasion, for better or worse. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnson S, Brooks NJ, Smith RA, Lea SM, Bubeck D. Structural basis for recognition of the pore-forming toxin intermedilysin by human complement receptor CD59. Cell Rep. 2013;3:1369–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Houser SL, Kuwaki K, Knosalla C, et al. Thrombotic microangiopathy and graft arteriopathy in pig hearts following transplantation into baboons. Xenotransplantation. 2004;11:416–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shimizu A, Yamada K, Yamamoto S, et al. Thrombotic microangiopathic glomerulopathy in human decay accelerating factor-transgenic swine-to-baboon kidney xenografts. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2732–2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shimizu A, Hisashi Y, Kuwaki K, et al. Thrombotic microangiopathy associated with humoral rejection of cardiac xenografts from alpha1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout pigs in baboons. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1471–1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shimizu A, Yamada K, Robson SC, Sachs DH, Colvin RB. Pathologic characteristics of transplanted kidney xenografts. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:225–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schirmer JM, Fass DN, Byrne GW, Tazelaar HD, Logan JS, McGregor C. Effective antiplatelet therapy does not prolong transgenic pig to baboon cardiac xenograft survival. Xenotransplantation. 2004;11:436–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Byrne GW, Schirmer JM, Fass DN, et al. Warfarin or low-molecular-weight heparin therapy does not prolong pig-to-primate cardiac xenograft function. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1011–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Byrne GW, Davies WR, Oi K, et al. Increased immunosuppression, not anticoagulation, extends cardiac xenograft survival. Transplantation. 2006;82:1787–1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang L, Cooper D, Burdorf L, Wang Y, Iwase H. Overcoming coagulation dysregulation in pig solid organ transplantation in nonhuman primates: recent progress. Transplantation. 2018;10:1050–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Iwase H, Ekser B, Hara H, et al. Regulation of human platelet aggregation by genetically modified pig endothelial cells and thrombin inhibition. Xenotransplantation. 2014;21:72–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Langin M, Mayr T, Reichart B, et al. Consistent success in life-supporting porcine cardiac xenotransplantation. Nature. 2018;564(7736):430–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hagiwara S, Iwasaka H, Matsumoto S, Hasegawa A, Yasuda N, Noguchi T. In vivo and in vitro effects of the anticoagulant, thrombomodulin, on the inflammatory response in rodent models. Shock. 2010;33:282–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hara H, Iwase H, Miyagawa Y, et al. Reducing the inflammatory response by expressing human thrombomodulin in pigs. Xenotransplantation. 2017;24:19–20. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ezzelarab MB, Ekser B, Azimzadeh A, et al. Systemic inflammation in xenograft recipients precedes activation of coagulation. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:32–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ezzelarab MB, Cooper D. Systemic inflammation in xenograft recipients (SIXR): a new paradigm in pig-to-primate xenotransplantation? Int J Surg. 2015;23(Pt B):301–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Iwase H, Ekser B, Zhou H, et al. Further evidence for sustained systemic inflammation in xenograft recipients (SIXR). Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:399–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Iwase H, Liu H, Li T, et al. Therapeutic regulation of systemic inflammation in xenograft recipients. Xenotransplantation. 2017;24:e12296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang JS, Yen HL, Yang CM. Warm-up exercise suppresses platelet-eosinophil/neutrophil aggregation and platelet-promoted release of eosinophil/neutrophil oxidant products enhanced by severe exercise in men. Thromb Haemost. 2006;95:490–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Heeger PS, Kemper C. Novel roles of complement in T effector cell regulation. Immunobiology. 2012;217:216–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Noris M, Remuzzi G. Overview of complement activation and regulation. Semin Nephrol. 2013;33:479–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ekdahl KN, Teramura Y, Hamad OA, et al. Dangerous liaisons: complement, coagulation, and kallikrein/kinin cross-talk act as a linchpin in the events leading to thromboinflammation. Immunol Rev. 2016;274:245–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Engelmann B, Massberg S. Thrombosis as an intravascular effector of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:34–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Killick J, Morisse G, Sieger D, Astier AL. Complement as a regulator of adaptive immunity. Semin Immunopathol. 2018;40(1):37–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ollinger R, Pratschke J. Role of heme oxygenase-1 in transplantation. Transpl Int. 2010;23:1071–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Katori M, Busuttil RW, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Heme oxygenase-1 system in organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;74:905–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bhang SH, Kim JH, Yang HS, et al. Combined gene therapy with hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and heme oxygenase-1 for therapeutic angiogenesis. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:915–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Soares MP, Bach FH. Heme oxygenase-1: from biology to therapeutic potential. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Loboda A, Jazwa A, Grochot-Przeczek A, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 and the vascular bed: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:1767–1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Otterbein LE, Choi AM. Heme oxygenase: colors of defense against cellular stress. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:L1029–L1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Soares MP, Lin Y, Anrather J, et al. Expression of heme oxygenase-1 can determine cardiac xenograft survival. Nat Med. 1998;4:1073–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Camara NO, Soares MP. Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), a protective gene that prevents chronic graft dysfunction. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:426–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yan JJ, Yeom HJ, Jeong JC, et al. Beneficial effects of the transgenic expression of human sTNFalphaR-Fc and HO-1 on pig-to-mouse islet xenograft survival. Transpl Immunol. 2016;34:25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wilhite T, Ezzelarab C, Hara H, et al. The effect of Gal expression on pig cells on the human T-cell xenoresponse. Xenotransplantation. 2012;19:56–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ezzelarab MB, Ayares D, Cooper D. Transgenic expression of human CD46: does it reduce the primate T-cell response to pig endothelial cells? Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:487–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ide K, Wang H, Tahara H, et al. Role for CD47-SIRPalpha signaling in xenograft rejection by macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5062–5066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yang YG. CD47 in xenograft rejection and tolerance induction. Xenotransplantation. 2010;17:267–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Navarro-Alvarez N, Yang YG. CD47: a new player in phagocytosis and xenograft rejection. Cell Mol Immunol. 2011;8:285–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang H, Yang YG. Innate cellular immunity and xenotransplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2012;17:162–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Oldenborg PA, Zheleznyak A, Fang YF, et al. Role of CD47 as a marker of self on red blood cells. Science. 2000;288:2051–2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Okazawa H, Motegi S, Ohyama N, et al. Negative regulation of phagocytosis in macrophages by the CD47-SHPS-1 system. J Immunol. 2005;174:2004–2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wang H, Verhalen J, Madariaga ML, et al. Attenuation of phagocytosis of xenogeneic cells by manipulating CD47. Blood. 2007;109:836–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dai H, Friday AJ, Abou-Daya KI, et al. Donor SIRPαpolymorphism modulates the innate immune response to allogeneic grafts. Sci Immunol. 2017;2(12):eaam6202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Boettcher AN, Cunnick JE, Powell EJ, et al. Porcine signal regulatory protein alpha binds to human CD47 to inhibit phagocytosis: implications for human hematopoietic stem cell transplantation into severe combined immunodeficient pigs. Xenotransplantation. 2018:e12466. 10.1111/xen.12466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jung SH, Hwang JH, Kim SE, et al. The potentiating effect of hTFPI in the presence of hCD47 reduces the cytotoxicity of human macrophages. Xenotransplantation. 2017;24(3):e12301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yan JJ, Koo TY, Lee HS, et al. Role of human CD200 overexpression in pig-to-human xenogeneic immune response compared with human CD47 overexpression. Transplantation. 2018;102:406–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tena AA, Sachs DH, Mallard C, et al. Prolonged survival of pig skin on baboons after administration of pig cells expressing human CD47. Transplantation. 2017;101:316–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tena A, Kurtz J, Leonard Da, et al. Transgenic expression of human CD47 markedly increases engraftment in a murine model of pig-to-human hematopoietic cell transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:2713–2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yamada K, Shah JA, Tanabe T, Lanaspa MA, Johnson RJ. Xenotransplantation: where are we with potential kidney recipients? Recent progress and potential future clinical trials. Curr Transplant Rep. 2017;4:101–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chen M, Wang Y, Wang H, Sun L, Fu Y, Yang YG. Elimination of donor CD47 protects against vascularized allograft rejection in mice. Xenotransplantation. 2018:e12459. 10.1111/xen.12459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dieckhoff B, Karlas A, Hofmann A, et al. Inhibition of porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERVs) in primary porcine cells by RNA interference using lentiviral vectors. Arch Virol. 2007;152:629–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dieckhoff B, Petersen B, Kues WA, Kurth R, Niemann H, Denner J. Knockdown of porcine endogenous retrovirus (PERV) expression by PERV-specific shRNA in transgenic pigs. Xenotransplantation. 2008;15:36–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ramsoondar J, Vaught T, Ball S, et al. Production of transgenic pigs that express porcine endogenous retrovirus small interfering RNAs. Xenotransplantation. 2009;16:164–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Niu D, Wei H-J, Lin L, et al. Inactivation of porcine endogenous retrovirus in pigs using CRISPR-Cas9. Science. 2017;357:1303–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fishman JA. Infectious disease risks in xenotransplantation. Am J Transplant. 2018;18:1857–1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Iwase H, Klein E, Cooper D. Physiological aspects of pig kidney transplantation in primates. Comp Med. 2018;68:332–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Iwase H, Yamamoto T, Cooper D. Episodes of hypovolemia/dehydration in baboons with pig kidney transplants: a new syndrome of clinical importance? Xenotransplantation. 2018;e12472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cooper D, Ekser B, Ramsoondar J, Phelps C, Ayares D. The role of genetically-engineered pigs in xenotransplantation research. J Pathol. 2016;238:288–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Maeda A, Kawamura T, Ueno T, Usui N, Eguchi H, Miyagawa S. The suppression of inflammatory macrophage-mediated cytotoxicity and proinflammatory cytokine production by transgenic expression of HLA-E. Transpl Immunol. 2013;29:76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gao B, Long C, Lee W, et al. Anti-Neu5Gc and anti-non-Neu5Gc antibodies in healthy humans. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0180768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wang ZY, Burlak C, Estrada JL, Li P, Tector MF, Tector AJ. Erythrocytes from GGTA1/CMAH knockout pigs: implications for xenotransfusion and testing in non-human primates. Xenotransplantation. 2014;21:376–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhang Z, Hara H, Long C, et al. Immune response of HLA-highly-sensitized and non-sensitized patients to genetically-engineered pig cells. Transplantation. 2017;102:e195–e204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hara H, Koike N, Long C, et al. Initial in vitro investigation of the human immune response to corneal cells from genetically-modified pigs. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:5278–5286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Petersen B, Ramackers W, Lucas-Hahn A, et al. Transgenic expression of human heme oxygenase-1 in pigs confers resistance against xenograft rejection during ex vivo perfusion of porcine kidneys. Xenotransplantation. 2011;18:355–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Cooper D, Ekser B, Burlak C, et al. Clinical lung xenotransplantation – what genetic modifications to the pig may be necessary? Xenotransplantation. 2012;19:144–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]