Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the impacts of a transition to an “integrated managed care” model, wherein Medicaid managed care organizations moved from a “carve‐out” model to a “carve‐in” model integrating the financing of behavioral and physical health care.

Data Sources/Study Setting

Medicaid claims data from Washington State, 2014–2019, supplemented with structured interviews with key stakeholders.

Study Design

This mixed‐methods study used difference‐in‐differences models to compare changes in two counties that transitioned to financial integration in 2016 to 10 comparison counties maintaining carve‐out models, combined with qualitative analyses of 15 key informant interviews. Quantitative outcomes included binary measures of access to outpatient mental health care, primary care, the emergency department (ED), and inpatient care for mental health conditions.

Data Collection

Medicaid claims were collected administratively, and interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using a thematic analysis approach.

Principal Findings

The transition to financially integrated care was initially disruptive for behavioral health providers and was associated with a temporary decline in access to outpatient mental health services among enrollees with serious mental illness (SMI), but there were no statistically significant or sustained differences after the first year. Enrollees with SMI also experienced a slight increase in access to primary care (1.8%, 95% CI 1.0%–2.6%), but no sustained statistically significant changes in the use of ED or inpatient services for mental health care. The transition to financially integrated care had relatively little impact on primary care providers, with few changes for enrollees with mild, moderate, or no mental illness.

Conclusions

Financial integration of behavioral and physical health in Medicaid managed care did not appear to drive clinical transformation and was disruptive to behavioral health providers. States moving towards “carve‐in” models may need to incorporate support for practice transformation or financial incentives to achieve the benefits of coordinated mental and physical health care.

Keywords: managed care, Medicaid, mental health

What is known on this topic

Managed care “carve outs” of behavioral health charge a separate entity for holding financial risk and managing behavioral health services.

Many state Medicaid programs are moving away from “carve outs” to an integrated “carve in” model (with a single managed care organization responsible for managing physical and behavioral health).

Relatively little is known about the potential implications of these models on access to mental health services and whether impacts vary by severity of mental health conditions.

What this study adds

A transition to financially integrated care in Washington State was initially disruptive for behavioral health providers but had relatively little impact on primary care providers.

Integrated managed care was not associated with sustained, significant changes in access to outpatient mental health care, although enrollees with serious mental illness experienced slight increases in access to primary care.

Carving in behavioral health may create some administrative simplification for enrollees, but additional efforts—such as support for practice transformation—may be necessary to enhance access to care.

1. INTRODUCTION

Medicaid is the single largest financier of mental health care in the United States, 1 paying for at least 25% of all mental health services in the country in 2014. 2 Individuals with mental health conditions are more likely to be covered through Medicaid than other insurance programs. Compared to their commercial counterparts, adult Medicaid enrollees are almost 50% more likely to have a mental health condition and 90% more likely to have a serious mental illness (SMI). 3 Medicaid enrollees with mental health conditions often have co‐occurring physical health conditions, and their expenditures are approximately double those for enrollees with physical health conditions alone. 4 Thus, changes in how these services are financed can have significant implications for public health and the value of the Medicaid program.

Historically, Medicaid has separated the financing of physical and mental health services, creating mental or behavioral health “carve‐outs.” In these scenarios, physical health is managed and reimbursed by the primary Medicaid managed care organization (MCO), with mental health services managed and reimbursed by a behavioral health organization (BHO). Advocates for mental health carve‐outs expressed concerns that plans focused on physical health management lacked an understanding of mental health treatment, delivery, and specialty networks. Separately, some expressed concerns that blending funds in a comprehensive MCO might favor physical health services at the expense of needed mental health services.

However, new perspectives on carve‐out arrangements question whether they may act as barriers to better outcomes for Medicaid enrollees. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 A robust evidence base—including more than 80 randomized trials—demonstrated that the collaborative care model (CoCM), (a specific model of mental health integration) improves patient outcomes. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 A separate line of research tested the benefits of improving care for individuals with SMI by providing physical health care in behavioral health settings (sometimes called “reverse integration”). Although the evidence is less developed, these approaches have shown moderate success in clinical trials and observational studies. 19 , 20

Carve‐outs create separate payers and networks, potentially restricting reimbursement for physical and mental health services, presenting impediments to communications across systems, and creating complexity for enrollees. These concerns have led many states to shift to a carve‐in (integrated) model for MCOs. In contrast to the robust evidence base for clinically integrated models, relatively little is known about the effects of financial integration within MCOs, particularly in the post‐Affordable Care Act (ACA) environment.

This mixed‐methods paper uses a natural experiment to assess the effects of a shift to integrated managed care (IMC) within Medicaid MCOs. We analyze a policy reform in Washington State, which launched its IMC initiative in 2016. This initiative shifted from a system with separate financing for behavioral and physical health to an integrated model, with the MCO responsible for payment for both behavioral and physical health. Washington's move to IMC was staggered across county groups, with the first counties transitioning in 2016 and the final group in 2020. In this paper, we compare outcomes through 2019 in the early transition group to counties that did not transition during the study period. We focus on this first group because previous studies of coordinated care outside a clinical, controlled setting suggest that the benefits could take as long as 2–3 years, with smaller gains happening thereafter and some setbacks possible. 21 Our study allows for 15 quarters (almost 4 years) of post‐intervention observations, providing a relatively long period to observe potential changes. We analyzed changes for two subpopulations: enrollees with SMI and enrollees with mild, moderate, or no observed mental illness. Enrollees with SMI may be more likely to receive health care through community mental health centers, which may have long‐standing relationships with behavioral health carve‐outs. Thus, they may be impacted differentially by financial integration relative to enrollees with mild or moderate mental health conditions, who may receive most of their care in primary care settings. 22 , 23

2. METHODS

2.1. Study environment

Washington's Medicaid program adopted managed care for physical health services in 1987, with approximately 84% of its enrollees covered by managed care in 2016. In 1993, the state began a managed care behavioral health program with services delivered through 11 county‐based Regional Support Networks, operating as prepaid health plans. In 2014, Senate Bill 6312 directed the state to integrate physical, mental health, and substance use disorder services through managed care by 2020. Washington's move to IMC was staged at the county level. Counties in each of the 10 IMC regions generally transitioned together at one of five separate launch waves (April 2016; January 2018; January 2019; July 2019; and January 2020).

Within the state, the University of Washington houses the Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions (AIMS) Center, a national program designed to advance the implementation of the CoCM. The AIMS Center and CoCM were not formally included in the IMC initiative. However, their presence meant that Washington was well‐suited to advance clinical integration if financial integration could act as a catalyst. Washington also engaged in a Medicaid Section 1115 waiver that included efforts to support integration, beginning in 2019, and applied across all regions.

2.2. Study design

This mixed‐methods study used analyses of Medicaid claims and qualitative interviews with key stakeholders in Washington. We used a difference‐in‐differences (DID) analysis, comparing outcomes for two counties (Clark and Skamania) that moved to IMC in April 2016 to 10 counties (Thurston, Mason, Cowlitz, Lewis, Wahkiakum, Pacific, Grays Harbor, Kitsap Jefferson, and Clallam) that did not transition to IMC until January 2020. Clark and Skamania are in southwest Washington; the comparison counties are in western Washington, with two comparison counties (Cowlitz and Lewis) bordering the two treatment counties (Data S1, Section A). The study protocol was approved by the Washington State IRB. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines (see Data S1). 24

2.3. Study sample

To understand payers' first‐hand experiences with the transition to IMC (e.g., their experiences with contracting, claims review, and administering new behavioral health services), we purposefully selected one individual with IMC implementation experience (e.g., an MCO representative, an IMC implementation leader, a contract administrator, an executive director, or a medical director) from each of the five MCOs. To ensure we learned about implementation experiences across the state, we also conducted one interview with a representative from each IMC region. State and regional leaders helped us identify individuals involved in the transition who could answer questions about the impacts of IMC.

Our enrollee study population included individuals ages 13–64 enrolled in Washington's Medicaid MCOs between April 1, 2014 and December 31, 2019, allowing for 2 years of pre‐intervention data. We excluded observations where the member was dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, part of the Emergency Medicaid or medically needy spend‐down program, had less than 3 months of enrollment in the calendar year, did not reside in one of the 12 counties included in our study, or was part of the fee‐for‐service population (Data S1, Section B). Claims and enrollment data were obtained from the Washington Health Care Authority.

We defined enrollees with SMI as those with any inpatient or psychiatric residential claim, or at least two outpatient claims on separate dates in 1 year, with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD9/10295.x; F20, F25), bipolar I (ICD9/10296.0, 296.1296.4–296.7; F30, F31.0‐F31.78), major depressive disorder (ICD9/10296.2x, 296.33, 296.34; F32.2, F32.3, F33.2, F33.3), or other schizophrenia spectrum or psychotic disorder (F28). We defined individuals with mild, moderate, or no mental illness as individuals without SMI.

2.4. Variables

We focused on four binary, access‐related outcomes for this study: use of any outpatient mental health services use of any primary care services; use of the emergency department (ED) for mental health conditions or self‐harm incidents; and use of inpatient care for mental health conditions (Data S1. Section B). The unit of observation was the person‐quarter. Covariates included enrollee age, gender, and the Chronic Illness and Disability Payment System (CDPS) risk adjusters. 25

2.5. Statistical analysis

Our DID analysis was conducted at the member‐quarter level. We ran two sets of analyses. The first was restricted only to enrollees with SMI, and the second to the complement, enrollees with mild, moderate, or no mental illness. We used a linear model with the covariates described above.

We estimated the following event‐study model to assess changes over time:

where Y ijt was the outcome of interest (e.g., any OPMH visit) for individual i in region j and year t; IMC j was a binary indicator if the individual was in the counties transitioning to IMC, and α t was an indicator for each of the 22 time periods, with 7 pre‐intervention quarters and 15 post‐intervention quarters, and Q1 2016 held out as a reference quarter. The coefficients of interest—γ—capture the interaction between α and IMC and are displayed in our Figures below. Demographic covariates, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, and CDPS risk adjusters, are captured in X it ; ε ijt , is a random error.

We also estimate simple DID estimators with and without trends to capture the policy effect averaged across the 15 post‐intervention quarters. Standard errors were clustered in the primary care service area (PCSA). PCSAs were developed by the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care as groups of zip codes that represent natural markets for primary care 26 , 27 (see Data S1, Section B).

2.6. Sensitivity analysis

Recent literature on DID models suggests that non‐parallel trends can bias results and that researchers may have placed too much confidence in tests that fail to reject the assumption of non‐parallel trends. 28 To provide a robust assessment of the potential effects of IMC, we produced event study graphs and incorporated advances in the DID literature using the methods outlined in Rambachan and Roth 29 and the R package HonestDiD 30 to examine the sensitivity of estimates to non‐linear differences in trends. To set bounds on our sensitivity analyses, we used a smoothness restriction, specifying a set M that described the possible violations of the parallel trend assumptions, where the change in the slope of the underlying trend would be no more than M between consecutive periods. We chose values of 0.05–0.25 for M based on preintervention trend differentials in that range.

2.7. Qualitative analysis

We conducted interviews between October 2021 and April 2022 using a semi‐structured interview guide (Data S1, Section C). We asked participants about their backgrounds, their experiences with IMC, and their perceptions of successes and challenges. Interviews were conducted by video software or over the phone, averaged 60 min, and were recorded with permission, and were professionally transcribed.

Transcripts were checked for accuracy, deidentified, and entered into Atlas.ti (version 9.0) for data management and analysis. 31 A three‐member research team with qualitative methods and primary care and mental health integration expertise analyzed data in tandem with data collection. We used a constant comparative method and an iterative process of analyzing and interpreting data to develop findings. 32 As transcripts became available, we analyzed the interview data as a group. We discussed key interview passages and developed an initial set of codes, continuing this group process of transcript review and coding as more data were collected. When the codes and their definitions were clear and consistent, we transitioned to independently coding the remaining transcripts until this process was complete. Regular meetings were designed to enhance reliability, discuss analytical questions, and identify emerging findings. We used an iterative process of moving between sampling, data collection, and analysis, allowing the use of early findings to refine recruitment targets as needed and monitor for saturation.

3. RESULTS

We completed 15 interviews; 10 with regional stakeholders and five with MCO representatives. Participants varied by role and wave (see Data S1, Section D). Our claims analysis included 108,875 unique enrollees (5411 with SMI; 103,464 without) in the two intervention counties and 203,486 unique enrollees in the 10 comparison counties (12,222 with SMI; 191,266 without). Table 1 displays the demographic characteristics of study groups in the intervention and comparison counties during the pre‐intervention year. Overall, enrollees in the intervention and treatment groups were relatively similar, with standardized differences having values close to 0.10 or lower. 33 The one exception was age. For the subpopulation of enrollees with mild, moderate, or no mental illness, enrollees in the treatment counties were, on average, younger than those in the intervention counties (standardized difference = 0.14).

TABLE 1.

Population characteristics for integrated managed care (IMC) regions during pre‐intervention year

| Enrollees with SMI | Enrollees with mild, moderate, or no observed mental illness | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMC Group | Comparison Group | Std. diff. | IMC Group | Comparison Group | Std. diff. | ||

| N | 3767 | 8959 | 57,414 | 111,375 | |||

| Age | 13–18 | 17.3 | 13.8 | 0.07 | 21.9 | 16.6 | 0.14 |

| 19–34 | 35.4 | 37.2 | 37.2 | 38.0 | |||

| 35–54 | 37.2 | 38.5 | 30.2 | 31.6 | |||

| 55–64 | 10.1 | 10.5 | 10.7 | 13.8 | |||

| Female | 58.4 | 58.9 | 0.01 | 53.5 | 51.3 | 0.04 | |

| Race and ethnicity | American Indian and Alaska Native | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.07 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.06 |

| Asian American and Pacific Islander | 2.6 | 2.4 | 0.01 | 6.0 | 4.8 | 0.05 | |

| Black | 4.1 | 3.0 | 0.06 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 0.05 | |

| Hispanic | 8.5 | 7.5 | 0.04 | 11.6 | 9.4 | 0.07 | |

| White | 78.7 | 82.3 | 0.09 | 71.4 | 76.4 | 0.11 | |

| Other/missing | 5.9 | 4.2 | 0.08 | 7.2 | 6.0 | 0.05 | |

| Comorbidities | Substance use Disorder | 21.8 | 22.7 | 0.02 | 5.5 | 7.9 | 0.10 |

| Cancer | 1.9 | 1.8 | 0.01 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 0.02 | |

| Cardiovascular conditions | 20.0 | 23.2 | 0.08 | 11.6 | 15.0 | 0.10 | |

| Diabetes | 8.3 | 8.9 | 0.02 | 4.3 | 5.4 | 0.05 | |

| Gastroenterological conditions | 16.6 | 19.0 | 0.06 | 7.5 | 9.4 | 0.07 | |

| Pulmonary conditions | 17.9 | 20.3 | 0.06 | 7.9 | 10.7 | 0.10 | |

Note: Pre‐intervention year is defined as April 1, 2015 through March 31, 2016. Values greater than 0.1 are typically interpreted as moderate to large differences between groups.

Abbreviation: SMI, serious mental illness; Std. diff., standardized difference.

Finding #1: The transition to financially integrated care was initially disruptive for behavioral health providers. Enrollees with SMI experienced reduced access to outpatient mental health care in the first year with no changes thereafter and a small increase in access to primary care.

The transition to IMC was challenging for behavioral health practices, which were forced to establish new relationships and contracts with MCOs.

The behavioral health [practices], I think [IMC] had a significant impact on them. At the administrative level, it was a heavy lift. They took the biggest brunt of the transition by far. Wave 1, Regional Stakeholder 3

During the transition to IMC, behavioral health practices experienced a substantial learning curve, purchasing new electronic health record (EHR) systems in addition to adapting to new documentation and billing requirements. Some of these practices previously received cost‐based reimbursement and were unaccustomed to MCO billing procedures. Behavioral health practices also experienced claim reimbursement delays and denials while adapting to new processes. Smaller practices did not have the financial reserves to accommodate these delays and required temporary financial support to maintain their business operations.

Behavioral health practices also shifted from having a single contract with the behavioral health administrator to multiple and disparate contracts with several MCOs. Stakeholders reported that behavioral health practices experienced increased administrative burden and costs to manage the new contracts:

It has increased administrative burden, hugely increased it. We now have five contracts and five different sets of regulations on how to bill. We have to tweak our internal computer system, our medical record, as well as our accounting to be able to work with the different MCOs […] Frankly, for a provider, it's added an awful lot of complication. Wave 5, Regional Stakeholder 7

The transition to IMC may have led to increased skills and capacity among behavioral health practices, as they acquired EHRs and learned new skills necessary for reporting and engaging in quality improvement activities that could eventually improve outcomes. However, continued work was needed to integrate care and change the care delivery system.

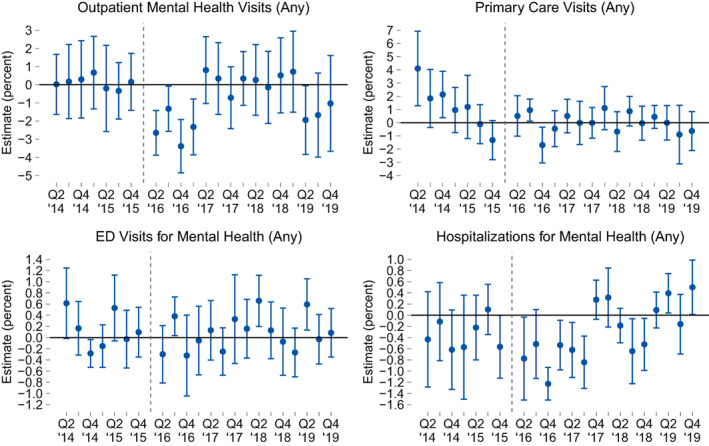

The disruptions occurring among behavioral health providers may have driven the initial disruptions in the receipt of outpatient mental health services observed in the claims data. Figure 1 displays adjusted event‐study‐type graphs of our DID estimates for any use of outpatient mental health, primary care, ED visits for mental health conditions or self‐harm, or hospitalization for mental health conditions among enrollees with SMI (see Data S1, Section E for graphs of unadjusted outcomes).

FIGURE 1.

Difference‐in‐differences (DID) estimates of changes in access associated with financial integration among Medicaid enrollees with serious mental illness (SMI). Outcomes are binary variables representing any encounter within a quarter for enrollees with SMI. Figures display adjusted DID estimates for outpatient mental health visits, primary care visits, emergency department visits for mental health conditions, and hospitalizations for mental health conditions. The integrated managed care initiative is marked by the vertical line, beginning in quarter 2 (Q2) of 2016. These figures report coefficients from an adjusted DID regression. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Access to outpatient mental health services was similar in the treatment and comparison groups leading up to the intervention but then led to a sharp drop of approximately three percentage points (from a baseline rate of 49%) for the first four quarters. This drop was not sustained, however, and after the first four quarters, access rates were relatively similar between the treatment and comparison groups. We observed a similar pattern in the use of inpatient care for mental health conditions, with decreases in the first six quarters, stabilizing thereafter, and no observed changes in the use of the ED for mental health. In contrast, trends in access to primary care differed between the intervention and comparison counties, with access rates decreasing at a faster rate in the intervention counties prior to the intervention. This trend was reversed after the intervention, with access to primary care similar across both groups. Adjusting for these trends, we found evidence of increased access to primary care in the first year. We investigate these assumptions in depth in the section on sensitivity analyses below and summarize these findings in the synthesis section.

Finding #2: The transition to financially integrated care had relatively little impact on primary care providers, with relatively few changes for enrollees with mild, moderate, or no mental illness.

Behavioral health integration is frequently conceptualized as centered in primary care, with linkages to mental health through coordination or colocation. Yet IMC required relatively little change from primary care practices. Prior to IMC, most primary care practices already had contracts in place with MCOs and could bill for behavioral health services for enrollees with mild or moderate mental illness. With the IMC transition, the focus remained largely on financial integration, with little guidance about expectations for clinical delivery changes in primary care:

In terms of the clinical side, the issue of actually integrating clinical services is still very early […] It's not there. Folks still struggle with partnerships or with being in a collaborative partnership with a health care provider or a social service agency. […] Those challenges are real and very much have not been solved. […] [The state] really focused on the financial integration of the systems and the systems being able to go under MCOs. There's a lot of work that needs to be done on the clinical side of things. Wave 1, Regional Stakeholder 3.

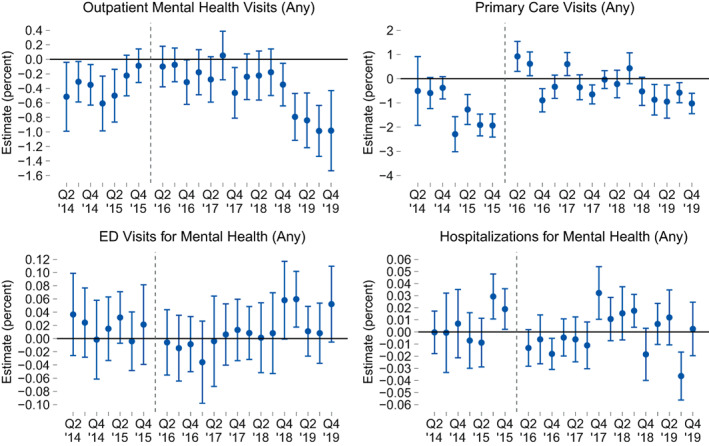

Figure 2 displays adjusted event‐study graphs of our DID estimates for enrollees with mild, moderate, or no mental illness. Although there were deviations from parallel trends in access to outpatient mental health and primary care, in general, the event study graphs do not show sustained changes in outcomes.

FIGURE 2.

Difference‐in‐differences (DID) estimates of changes in access associated with financial integration among Medicaid enrollees with mild, moderate, or no observed mental illness. Outcomes are binary variables representing any encounter within a quarter for enrollees with mild, moderate, or no observed mental illness. Figures display adjusted DID estimates for outpatient mental health visits, primary care visits, emergency department visits for mental health conditions, and hospitalizations for mental health conditions. The integrated managed care initiative is marked by the vertical line, beginning in quarter 2 (Q2) of 2016. These figures report coefficients from an adjusted DID regression. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

4. SENSITIVITY ANALYSES

We conducted sensitivity analyses for all outcomes for the 4th, 8th, 12th, and 15th post‐intervention quarters using the HonestDiD 29 , 30 package. We display these results for all outcomes, for SMI enrollees and enrollees with mild, moderate, or no mental health conditions, in the Data S1 (Section F). In summary, many estimates that appear statistically significant in our event‐study analyses were highly sensitive to the parallel trend assumption. In most cases, results were not significant unless we applied restrictive assumptions of parallel trends or strictly linear post‐treatment trends. These findings were true even in some cases where the event‐study estimates appeared significant (such as the drop in access to outpatient mental health for individuals with mild, moderate, or no mental health conditions), with the HonestDiD approach producing confidence intervals that crossed zero if we relaxed the parallel trend assumption or did not restrict post‐treatment trends to be strictly linear. The one exception was access to primary care for enrollees with SMI. These results were less sensitive to assumptions about larger pre‐intervention trends immediately after the intervention, but demonstrated greater sensitivity in later periods. The results of these sensitivity analyses inform our synthesis of findings, described below.

5. SYNTHESIS OF FINDINGS

Table 2 provides a concise summary of our estimates, incorporating information on baseline values, the parallel trends test, and preferred estimates (based on the inclusion or exclusion of differential trends). Our final estimates, based on DID regressions that average outcomes across all 15 postintervention periods, suggest a slight increase in access to primary care for enrollees with SMI (+1.8%, 95% CI 1.0%–2.6%) after accounting for pre‐trend differences. We also found a slight decrease in access to outpatient mental health services in the first four quarters, but this change was not sustained. Access to inpatient services for mental health care also declined in the first six quarters, but we observed no differences in access to the ED for mental health care. These findings correspond with interviews with key informants, who reported that IMC created new challenges for behavioral health providers, which may have limited the ability to increase access to mental health care services for enrollees with SMI while opening up greater access to primary care for these enrollees.

TABLE 2.

Summary of evidence

| Measure | Pre‐intervention mean in intervention counties | Difference in pre‐intervention trends | Preferred estimate a | Findings from sensitivity analyses | Qualitative context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrollees with serious mental illness | |||||

| Any outpatient mental health visit | 49.4% | −0.04 (−0.2, 0.2) | −0.9% (−2.5%, 0.7%) | Evidence for drop in access in first four quarters after intervention; moderately sensitive to pre‐trends assumptions. | Behavioral health practices experienced disruptions, adapting to new requirements for electronic health records, data systems, documentation, and reimbursement. Many were required to shift from a single contract with a Behavioral Health Organization to contracts with multiple managed care organizations. |

| Any primary care visit | 61.1% | −0.6 (−0.9, −0.3) | 1.8% (1.0%, 2.6%) 1 | Evidence for increase in access in first four quarters after intervention, after accounting for pre‐trends; mildly sensitive to pre‐trends assumptions. | |

| Any emergency department (ED) visit for mental health | 3.8% | −0.04 (−0.10, 0.03) | −0.03% (−0.31%, 0.25%) | Cannot reject null hypothesis of no change | |

| Any hospitalization for mental health | 2.8% | 0.04 (−0.08, 0.16) | 0.00% (−0.28%, 0.28%) | Evidence of decrease of use of inpatient services for mental health conditions in first six quarters, but sensitive to pre‐trend assumptions; cannot reject null hypothesis of no change after six quarters | |

| Enrollees with mild, moderate or no observed mental illness | |||||

| Any outpatient mental health visit | 8.2% | 0.06 (0.01, 0.11) | 0.07% (−0.1%, 0.3%) 1 | Estimates very sensitive to assumptions about pretrends; lacks sufficient evidence to suggest change | IMC required relatively little change from primary care practices and was associated with little guidance about what should be expected on the clinical or delivery side. |

| Any primary care visit | 35.2% | −0.07 (−0.2, 0.1) | Null finding 2 | Estimates very sensitive to any assumption of pre‐trend effect | |

| Any ED visits for mental health | 0.3% | −0.00 (−0.01, 0.00) | 0.00% (−0.03%, 0.02%) | Cannot reject null hypothesis of no change | |

| Any hospitalization for mental health | 0.07% | −0.00 (−0.00, 0.00) | 0.01% (−0.02%, 0.01%) | Cannot reject null hypothesis of no change | |

Note: Outcomes are binary variables representing any encounter within a quarter. Difference‐in‐differences (DID) estimates represent changes associated with transition to integrated managed care, averaged over 15 quarters. Bold entries are statistically significant at the 5% level.

Regression estimates without a footnote are based on standard DID estimates that do not incorporate differential trends. Regression estimates with a footnote of “1” are based on DID estimates with differential trends. Rather than present a single regression estimate for any primary care visit for enrollees with mild, moderate or no observed mental illness (footnote of “2”) we present a null finding; estimates are very sensitive to the inclusion of a linear trend and suggest that small deviations from linearity would produce results that are not significantly different from zero.

In contrast, in our analyses of enrollees with mild, moderate, or no mental health conditions, we find null effects across all outcomes. These findings correspond with qualitative data that suggest that IMC had relatively little impact on clinical changes in primary care.

6. DISCUSSION

Our study of two counties that transitioned to financial integration has several key findings. First, financial integration did not lead to significant changes in the use of ambulatory or emergency mental health services among enrollees with mild, moderate, or no mental health conditions. Enrollees with SMI experienced decreased access to mental health services in the first year, but no change overall when averaged across the 15 quarters following the intervention. However, enrollees with SMI also had slightly greater access to primary care services after IMC (an increase of approximately 2%, based on an average access rate of 61%). We did not find evidence for increased access to mental health services among enrollees with mild, moderate, or no mental health conditions. Qualitative data indicated that financial integration was initially disruptive to behavioral health providers but had little impact on primary care providers and did not catalyze substantial changes in clinical or delivery systems.

This paper contributes to a greater understanding of carve‐in models for mental health services in Medicaid. Frank and Garfield's 2007 review of behavioral health carve‐outs in Medicaid and commercial markets was generally favorable, concluding that “[a]lthough not perfect, carve‐outs have been instrumental in addressing long‐standing challenges in utilization, access, and cost of behavioral health care.” 34 Within Medicaid, their review found carve‐outs to be associated with lower utilization of psychiatric inpatient services but did not find strong associations with outpatient utilization or quality. A more recent RAND assessment 35 of states' experiences in adopting a behavioral health carve‐in model found only three studies that examined the outcomes of the carve‐in model with rigorous quasi‐experimental designs. 22 , 36 , 37 These single‐state studies were somewhat inconsistent in their findings, with two studies finding increased behavioral health access with the carve‐in and one finding decreased access. Our study differs from these studies in the longer (nearly four‐year) period of post‐intervention observations and a relative lack of confounding policies. Furthermore, to our knowledge, ours is the only study that uses longitudinal data drawn from the post‐ACA era to assess the carve‐in question for Medicaid enrollees with and without SMI.

Our study found no increases in access to outpatient mental health services, with some evidence of decreased access in the first year among enrollees with SMI and increased access to primary care, and potential decreases in access to outpatient mental health care in later periods for enrollees with mild, moderate, or no mental health conditions, although those findings were sensitive to modeling assumptions. Although IMC's impacts on access were small, and primarily confined to enrollees with SMI, the shift to financial integration may have produced other benefits that we did not measure. For example, IMC may have benefited enrollees by creating a single plan for coverage rather than requiring coordination between two. Furthermore, moving behavioral health into MCOs created opportunities for greater overall resources and economies of scale, with MCOs potentially using their statewide view and data analytics in ways that could benefit enrollees.

The lack of increased access to outpatient mental health services does not necessarily indicate a reduction in quality, coordination, or patient‐centered outcomes, particularly if accompanied by increased access to primary care services. In fact, the IMPACT trial—a randomized test of the CoCM—demonstrated a reduction in depressive symptoms of 50% or more, despite negligible differences between the treatment and control arms for primary care visits, outpatient specialty care visits, or hospitalizations for mental health conditions. 11 , 38 Furthermore, Washington State's Research and Data Analysis Division analyzed changes in the two early adopter counties, finding IMC to be associated with significant improvements in several quality measures (including, e.g., access to Cervical Cancer Screening and access to Mental Health Treatment). 39 Thus, the changes observed in our study do not necessarily imply that enrollees were worse off under IMC. In particular, the lack of increased ED visits for mental health and the temporary reduction in hospitalizations for mental health conditions suggest that any reductions in outpatient mental health visits were not substantial enough to spill over into the acute care setting.

Financial integration may be insufficient to drive large improvements in mental health care. 35 , 40 , 41 , 42 Thus, states may need to couple these efforts with support for practice transformation or a stronger set of aligned incentives. 35 Some states have created carve‐in or carve‐out models for specific populations, such as enrollees with SMI or substance use disorders. 23 , 43 Given the moderately differential impacts of this study and the study by Charlesworth and colleagues, 22 additional considerations for these targeted carve‐in approaches may be warranted.

Overall, more efforts are needed to identify how Medicaid programs can capitalize on the benefits of integrated care. In particular, it will be essential to understand how financial integration affects the cost of care, the size and quality of mental health networks, and whether certain populations (e.g., enrollees with SMI) are more or less likely to benefit from new arrangements.

7. LIMITATIONS

This analysis had several limitations. We assessed changes in two counties that were the first to transition to IMC; they may not be representative of delivery systems that generalize to the larger Medicaid population. Future studies will assess changes across all five IMC regions. Second, our study did not provide information about whether providers could communicate and coordinate better with each other following IMC. Third, the IMC transition may have resulted in changes in the way encounter systems recorded visits, potentially biasing our results down if behavioral health providers failed to record all visits during the change in data systems. Fourth, we used linear models to assess binary outcomes; compared to logistic models, linear models can yield predicted probabilities outside the 0–1 interval, but they provide greater ease of interpretation, and the treatment effect estimates are likely to be similar for large N studies. Fifth, interviews took place in 2021 and 2022, requiring respondents to retrospectively describe the transition, potentially introducing recall bias. Sixth, we did not evaluate measures of quality or patient outcomes such as well‐being or mental or physical health. Our analysis was limited, in part, by 2 years of pre‐intervention data. Many quality measures require a one‐year observation period, often with an additional lookback year, shortening the available pre‐intervention observation period. Given the sensitivities to assumptions around parallel trends, we chose to focus on access outcomes and reserve assessments of quality for future studies. It is possible that patient‐centered outcomes could have changed with IMC and that the simplification granted by a single health plan may have led to improvements in enrollee experience. We cannot exclude the possibility that more significant changes from financial integration may emerge over a longer time horizon.

8. CONCLUSIONS

In this study, a transition to an integrated, carve‐in arrangement was associated with a small but statistically significant increase in access to primary care services and no sustained change in access to outpatient mental health visits among enrollees with SMI. There were no sustained, significant changes for enrollees with mild, moderate, or no observed mental illness. Financial integration presented new challenges and disruptions to behavioral health agencies but had little impact on primary care clinics. Efforts to improve the coordination of physical and behavioral health by financially integrating these services in Medicaid managed care hold promise but may require incentives or support for practice transformation in addition to—or in place of—carve‐in arrangements.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supporting information.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Mental Health (1R01MH123416 [McConnell]; K08MH123624 [Zhu]).

McConnell KJ, Edelstein S, Hall J, et al. The effects of behavioral health integration in Medicaid managed care on access to mental health and primary care services—Evidence from early adopters. Health Serv Res. 2023;58(3):622‐633. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.14132

REFERENCES

- 1. Mark TL, Levit KR, Yee T, Chow CM. Spending on mental and substance use disorders projected to grow more slowly than all health spending through 2020. Health Aff. 2014;33(8):1407‐1415. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mark TL, Yee T, Levit KR, Camacho‐Cook J, Cutler E, Carroll CD. Insurance financing increased for mental health conditions but not for substance use disorders, 1986–2014. Health Aff. 2016;35(6):958‐965. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. MACPAC . 2021. Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP.

- 4. Boyd C, Leff B, Weiss C, Wolff J, Clark R, Richards T. Clarifying Multimorbidity to Improve Targeting and Delivery of Clinical Services for Medicaid Population. Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Katon W. Collaborative depression care models: from development to dissemination. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(5):550‐552. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Unützer J, Schoenbaum M, Druss BG, Katon WJ. Transforming mental health Care at the Interface with general Medicine: report for the presidents commission. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(1):37‐47. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.1.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bachman J, Pincus HA, Houtsinger JK, Unützer J. Funding mechanisms for depression care management: opportunities and challenges. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(4):278‐288. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Frank RG, Huskamp HA, Pincus HA. Aligning incentives in the treatment of depression in primary care with evidence‐based practice. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(5):682‐687. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.5.682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goldberg RJ. Financial incentives influencing the integration of mental health care and primary care. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(8):1071‐1075. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.8.1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thota AB, Sipe TA, Byard GJ, et al. Collaborative care to improve the management of depressive disorders: a community guide systematic review and meta‐analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(5):525‐538. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Unutzer J, Katon WJ, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late‐life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2836‐2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(10):CD006525. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006525.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. O'Connor EA, Whitlock EP, Beil TL, Gaynes BN. Screening for depression in adult patients in primary care settings: a systematic evidence review. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(11):793‐803. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Siu AL, US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) , Bibbins‐Domingo K, et al. Screening for depression in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315(4):380‐387. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta‐analysis and review of longer‐term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(21):2314‐2321. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hunkeler EM, Katon W, Tang L, et al. Long term outcomes from the IMPACT randomised trial for depressed elderly patients in primary care. BMJ. 2006;332(7536):259‐263. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38683.710255.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Woltmann E, Grogan‐Kaylor A, Perron B, Georges H, Kilbourne AM, Bauer MS. Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health care settings: systematic review and meta‐analysis. AJP. 2012;169(8):790‐804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11111616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miller CJ, Grogan‐Kaylor A, Perron BE, Kilbourne AM, Woltmann E, Bauer MS. Collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions: cumulative meta‐analysis and meta‐regression to guide future research and implementation. Med Care. 2013;51(10):922‐930. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a3e4c4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ward MC, Druss BG. Reverse integration initiatives for individuals with serious mental illness. FOC. 2017;15(3):271‐278. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.20170011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Druss BG, von Esenwein SA, Glick GE, et al. Randomized trial of an integrated behavioral health home: the Health Outcomes Management and Evaluation (HOME) study. AJP. 2016;174(3):246‐255. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16050507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carlo AD, Jeng PJ, Bao Y, Unützer J. The learning curve after implementation of collaborative care in a state mental health integration program. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(2):139‐142. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201800249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Charlesworth CJ, Zhu JM, Horvitz‐Lennon M, McConnell KJ. Use of behavioral health care in Medicaid managed care carve‐out versus carve‐in arrangements. Health Serv Res. 2021;56(5):805‐816. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McConnell K, Hall J, Lindner S, et al. Financial Integration of Behavioral Health in Medicaid Managed Care Organizations: A New Taxonomy. Center for Health Systems Effectiveness, Oregon Health & Science University; 2021. Accessed June 20, 2021. https://www.ohsu.edu/sites/default/files/2021‐05/McConnell%20et%20al.%20Financial%20Integration%20of%20Behavioral%20Health%20in%20Medicaid.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495‐1499. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kronick R, Gilmer T, Dreyfus T, Lee L. Improving health‐based payment for Medicaid beneficiaries: CDPS. Health Care Financ Rev. 2000;21(3):29‐64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goodman DC, Mick SS, Bott D, et al. Primary care service areas: a new tool for the evaluation of primary care services. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(1):287‐309. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. The Dartmouth Institute ‐ Primary Care Service Area (PCSA). Published 2015. Accessed December 1, 2015. http://tdi.dartmouth.edu/research/evaluating/health-system-focus/primary-care-service-area

- 28. Roth J, Sant'Anna PHC, Bilinski A, Poe J. What's Trending in Difference‐in‐Differences? A Synthesis of the Recent Econometrics Literature. Published online January 13, 2022. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2201.01194 [DOI]

- 29. Rambachan A, Roth J. A More Credible Approach to Parallel Trends. Published 2022. Accessed April 1, 2022. https://jonathandroth.github.io/assets/files/HonestParallelTrends_Main.pdf

- 30. Rambachan A. HonestDiD. Published online July 8, 2022. Accessed July 29, 2022. https://github.com/asheshrambachan/HonestDiD

- 31. Atlas.ti. Scientific Software Development GmbH [ATLAS.ti 9 Windows]. 2020.

- 32. Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 3rd ed. SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Austin PC. Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Commun Statis Simulat Comput. 2009;38(6):1228‐1234. doi: 10.1080/03610910902859574 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Frank RG, Garfield RL. Managed behavioral health care carve‐outs: past performance and future prospects. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28(1):303‐320. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Horvitz‐Lennon MA, Levin JS, Breslau J, Kushner J, Eberhart NK, Bhandarkar M. Carve‐In models for specialty behavioral health services in Medicaid. Lessons for the State of California. RAND Corporation; 2022. Accessed May 1, 2022. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1517-1.html [Google Scholar]

- 36. Frimpong EY, Ferdousi W, Rowan GA, Radigan M. Impact of the 1115 behavioral health Medicaid waiver on adult Medicaid beneficiaries in New York State. Health Serv Res. 2021;56(4):677‐690. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Xiang X, Owen R, Langi FLFG, et al. Impacts of an integrated Medicaid managed care program for adults with behavioral health conditions: the experience of Illinois. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2019;46(1):44‐53. doi: 10.1007/s10488-018-0892-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Unutzer J, Katon WJ, Fan MY, et al. Long‐term cost effects of collaborative care for late‐life depression. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(2):95‐100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bittinger K, Court B, Mancuso D. Evaluation of Integrated Managed Care for Medicaid Beneficiaries in Southwest Washington: First Year Outcomes. Washington State Department of Social and Health Services; 2019. Accessed December 4, 2019. https://www.dshs.wa.gov/ffa/rda/research‐reports/evaluation‐integrated‐managed‐care‐medicaid‐beneficiaries‐southwest‐washington‐first‐year‐outcomes [Google Scholar]

- 40. Figueroa JF, Phelan J, Newton H, Orav EJ, Meara ER. ACO participation associated with decreased spending for Medicare beneficiaries with serious mental illness. Health Aff. 2022;41(8):1182‐1190. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Colla C, Yang W, Mainor AJ, et al. Organizational integration, practice capabilities, and outcomes in clinically complex medicare beneficiaries. Health Serv Res. 2020;26:1085‐1097. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lewis VA, Colla CH, Tierney K, Citters ADV, Fisher ES, Meara E. Few ACOs pursue innovative models that integrate care for mental illness and substance abuse with primary care. Health Aff. 2014;33(10):1808‐1816. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Auty SG, Cole MB, Wallace J. Association between Medicaid managed care coverage of substance use services and treatment utilization. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(8):e222812. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.2812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supporting information.