Abstract

Oxygen evolution reaction catalysts capable of working efficiently in acidic media are highly demanded for the commercialization of proton exchange membrane water electrolysis. Herein, we report a Zn-doped RuO2 nanowire array electrocatalyst with outstanding catalytic performance for the oxygen evolution reaction under acidic conditions. Overpotentials as low as 173, 304, and 373 mV are achieved at 10, 500, and 1000 mA cm−2, respectively, with robust stability reaching to 1000 h at 10 mA cm−2. Experimental and theoretical investigations establish a clear synergistic effect of Zn dopants and oxygen vacancies on regulating the binding configurations of oxygenated adsorbates on the active centers, which then enables an alternative Ru−Zn dual-site oxide path of the reaction. Due to the change of reaction pathways, the energy barrier of rate-determining step is reduced, and the over-oxidation of Ru active sites is alleviated. As a result, the catalytic activity and stability are significantly enhanced.

Subject terms: Nanoscale materials, Electrocatalysis, Electrochemistry

Ru-based materials are promising catalysts for oxygen evolution reaction in acidic condition, but their catalytic performance needs to be further improved. Here, the authors report Zn-RuO2 nanowires with a Ru−Zn dual-site oxide reaction pathway with enhanced activity and stability for acidic oxygen evolution reaction.

Introduction

Hydrogen (H2) generation via electrochemical water splitting is a promising way to efficiently store intermittent renewable energy1–3. However, the sluggish oxygen evolution reaction (OER) on anode hinders the overall efficiency of water splitting and leads to large undesired energy consumption4,5. Therefore, the design of high performance OER catalysts is regarded as a matter of urgency for the industrial application of water-to-H2 conversion6–9. To date, attractive candidates based on earth-abundant transition metals, especially the (oxy)hydroxides and layered double hydroxides of Ni−Fe10–12, have been widely reported under basic conditions, offering a chance to build low-cost alkaline water electrolysis (AWE) assemblies without noble metals in application. However, the currently deployed AWE devices are still facing intrinsic challenges, including the low operating pressure, inevitable gas crossover, slow load response, and limited current density, mainly due to the utilization of a diaphragm and a liquid electrolyte13.

Compared with AWE, water electrolysis using proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyzers can effectively address the above challenges with significantly improved performance14–16. But the highly corrosive conditions at high oxidation potentials under acidic environments make the development of efficient OER catalysts a great challenge. Most existing OER catalysts with excellent performance in basic condition generally show unsatisfied kinetics in acidic media, which, furthermore, suffer from severe degradation under the harsh conditions. So far, only the catalysts based on Ru and Ir noble metals can meet the requirements of PEM water electrolysis in practical deployment, though the scarcity of iridium and relatively low mass activity of Ir-based catalysts are serious obstacles to industrial scale H2 production8,17,18. Ru-based catalysts, especially RuO2, show promise as OER catalysts in acidic media, being much cheaper than their Ir-based counterparts. The moderate binding strength of OER intermediates (O*, OH*, and OOH*) on Ru sites makes Ru-based catalysts very active for oxygen evolution, but the over-oxidation of Ru cations can create soluble species (Run+, n > 4) under acidic OER conditions, leading to rapid catalyst degradation and large losses in performance19–21. Poor durability is the biggest obstacle hindering the practical application of Ru-based catalysts in PEM water electrolyzers22,23.

Guest elements are usually introduced to improve the OER performance of RuO2 by modulating the chemical environment of Ru centers24. As reported recently, via constructing guest single atomic (e.g., Ni, Pt)25,26 and lattice doping (e.g., Mn, Cu, Na)27–29 sites, the overpotential of acidic OER on RuO2 can be reduced to ~180 mV@10 mA cm−2 with a durability over 200 h25. It was found that the presence of charge transfer between guest atoms and Ru cations can change the electronic structures of the Ru active sites30–33. The introduction of electron-donating dopants into RuO2 would reduce the oxidation state of Ru (Run+, n < 4), thus protecting surface Ru cations from over oxidation to soluble species during OER34,35. However, lowering the Ru oxidation state can impair the catalytic activity for OER, since the strong binding of OER intermediates on low-valent Ru sites would hinder the deprotonation of the second water molecule to form *OOH species36. Thus, high-valent Ru species generally show faster kinetics with lower overpotentials during OER26,37,38. The introduction of guest metal ions further provides a chance to create structure defects (e.g., oxygen vacancies, VO) to modulate the OER property of Ru centers31. Although the presence of VO defects would in principle reduce the oxidation state of Ru species and thus probably impair the OER activity37,39, the possible synergy between VO defects and guest elements would efficiently regulate the OER activity of Ru centers, which is not yet fully understood40–42.

From a practical perspective, in addition to the intrinsic activity, the number of active sites is also important for improving OER performance. The number of active sites can be enhanced by increasing the surface area-to-mass ratio of catalysts via morphology engineering43. RuO2-based materials with high aspect ratio morphologies demonstrate excellent activity for OER in acidic media32,44,45. In order to improve the stability of RuO2-based OER catalysts, direct construction of high aspect ratio RuO2 nanoarrays on conductive/corrosion resistant substrates is a preferred strategy. Additionally, close contact between the catalyst and substrate can also reduce interfacial charge transport resistance and facilitate the electron transfer for more efficient OER46.

Inspired by the structural advantages of dimensionally stable anodes (DSA)47, we herein synthesized Zn-doped RuO2 (py-RuO2:Zn) nanowire arrays on Ti substrate using a simple pyrolysis method. The developed py-RuO2:Zn catalyst offered outstanding catalytic activity and stability for OER in acidic media (0.5 M H2SO4). RuO2 doping by Zn2+ ions promoted the growth of nanowires (thereby increasing the availability of Ru active sites for OER), whilst also introducing VO defects and low-valent Ru sites. Theoretic investigations revealed that VO defects and Zn dopants caused a weakened binding of oxygen adsorbates at active Ru centers and, more interestingly, enable a moderate adsorption of *OH species on Zn sites. Consequently, a Ru−Zn dual-site oxide path of OER was favored and significantly enhanced the OER activity. In the meantime, the alternation of OER path avoided the over oxidation of the active metal centers, and the presence of Zn dopants and VO defects enabled a structure stabilization of RuO2 matrix. As a result, the py-RuO2:Zn nanowires exhibited low overpotentials for OER at current densities up to 1000 mA cm−2, together with outstanding stability reaching 1000 h at 10 mA cm−2, outperforming commercial RuO2 and most recently reported RuO2-based catalysts.

Results and discussion

Preparation and characterization of py-RuO2:Zn

The py-RuO2:Zn nanowire arrays were fabricated by a straightforward pyrolysis method directly on a Ti plate (Fig. 1a), similar to the DSA production in industrial applications47. In brief, a certain volume of aqueous solution containing RuCl3 and Zn(NO3)2 precursors (Zn/Ru atomic ratio = 0.5:1) was pipetted onto a freshly etched Ti plate over a confined rectangular area. After dried naturally at room temperature, the sample was then pyrolyzed at 350 °C in air to transform the precursors into metal oxides. Finally, the undesired ZnO component in the product was removed by an acid etching treatment. The derived py-RuO2:Zn product appeared as a dark gray coating tightly adhered to the Ti substrate (Supplementary Fig. 1). Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) results reveal that about 10% of Ru and 90% of Zn were removed after the acid etching treatment, leading to a decrease in the Zn/Ru atomic ratio from 54.6% to 6.39% (Supplementary Table 1). This change was confirmed by an energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis, which shows a similar Zn/Ru decrease from 56.6% to 5.15%, with both elements uniformly dispersing in the etched coating (Supplementary Figs. 2−3). Mass loadings of Ru and Zn in the acid-etched py-RuO2:Zn coating are calculated to be 520.0 and 21.5 μg cm−2, respectively, according to the ICP-MS results.

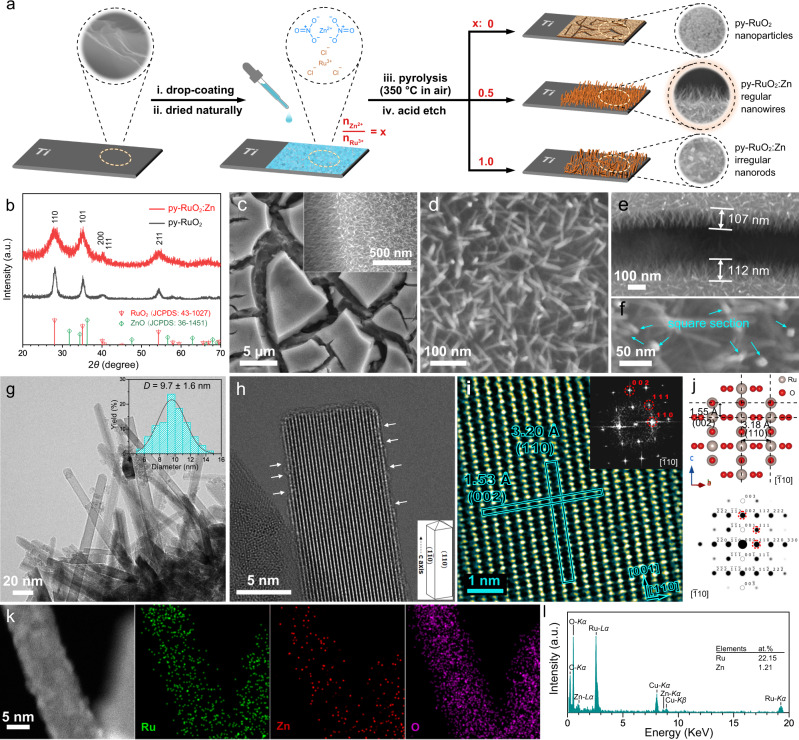

Fig. 1. Preparation scheme and physical characterizations of py-RuO2:Zn.

a Schematic illustration of catalyst fabrication method. b GIXRD patterns of py-RuO2:Zn and py-RuO2 catalysts. c, d SEM images of py-RuO2:Zn catalyst. e length and f section morphology analysis of nanowires. g TEM image and diameter distribution analysis (inset), and h HRTEM image (inset: illustration of the exposed planes and growth direction) of nanowires. i HRTEM image and corresponding FFT pattern (inset), and j crystal structure simulation of the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst. k HAADF-STEM images and l EDS analysis of Ru, Zn, and O elements in the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst.

Figure 1b shows a grazing incidence X-ray diffraction (GIXRD, incident angle 0.3°) pattern of the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst, as well as a pattern of the py-RuO2 catalyst that was prepared following the same pyrolysis method in the absence of the zinc precursor. The diffraction peaks of py-RuO2:Zn were almost the same as those of py-RuO2, well matching the database pattern of rutile RuO2 (JCPDS no. 43-1027). No peaks for ZnO were found. According to previous reports, Zn2+ prefers to substitutionally dope RuO2 at Ru4+ sites30,48, which is readily understood by the similar ionic radius of Ru4+ (0.62 Å) and Zn2+ (0.60 Å)49. Zn-doped RuO2 retains the rutile structure of pristine RuO248, with negligible shift in the XRD peaks seen for py-RuO2:Zn due to the low Zn content (<5 at.%). However, the diffraction peaks for py-RuO2:Zn were much broader than those of py-RuO2 (Fig. 1b), suggesting a decrease in the grain size resulting from Zn doping. The morphology of py-RuO2:Zn was next characterized by the scanning electron microscopy (SEM), with the analysis revealing a thin adherent coating with abundant microscale cracks from the precursor drying and pyrolysis steps (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 4). The coating contains dense arrays of high-quality nanowires with an average length of about 100 nm and a square cross-section along the growth direction (Fig. 1c (inset) and d−f). Control experiments revealed that the morphology of the nanowire arrays depended greatly on the composition and dosage of precursor solution and the pyrolysis temperature (Supplementary Figs. 5−7). In addition, the py-RuO2:Zn nanowire arrays could readily be fabricated on other substrates, such as carbon fiber paper (CFP) and fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) glass (Supplementary Fig. 8), highlighting the versatility of one-step pyrolysis catalyst fabrication strategy developed herein50–54. But both CFP and FTO supported py-RuO2:Zn catalyst shows a relatively lower OER activity for acidic OER (Supplementary Fig. 8). Therefore, the Ti plate was selected as the support for py-RuO2:Zn catalyst in this work, which is a widely used DSA material in chlorine evolution process47.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis revealed that the nanowires had a length around 100 nm and an average diameter of 9.7 nm, corresponding to an aspect ratio (length/diameter) of ~10 (Fig. 1g). In the high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images, random step and kink defects were found at the edges, possibly caused by the acid etching treatment (Fig. 1h). Lattice fringes with distinct interplanar distances of 3.20 Å and 1.53 Å were seen in the HRTEM images, well matching the (110) and (002) planes of rutile RuO2, respectively. This indicated that the nanowires were enclosed by {110} facets (Fig. 1i−j). The corresponding fast Fourier-transformation (FFT) electron diffraction pattern was in good agreement with the simulated one viewed along [] zone axis, suggesting single phase character and a [001] growth direction (c-axis) in the nanowire (Fig. 1i (inset) and j). The relative spatial distribution of Ru, Zn, and O elements in a single nanowire was studied by EDS under high-angle annular dark-field scanning TEM (HAADF-STEM) mode. As shown in Fig. 1k and l, each element was uniformly dispersed throughout the nanowire with a Zn/Ru atom ratio of 5.46%. This value is very close to those obtained from the ICP-MS and SEM-EDS studies (Supplementary Table 1). Interstitial Zn dopants were not seen in the atomic-resolution TEM image of a nanowire (Fig. 1i), confirming substitutional Zn doping and consistent with the XRD results.

The surface chemical information of py-RuO2:Zn and two pure RuO2 catalysts were next investigated by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). The Survey XPS spectrum confirmed the presence of Zn in py-RuO2:Zn (Supplementary Fig. 9), while the core-level Zn 2p spectrum showing peaks at 1021.4 and 1044.3 eV in a 2:1 area ratio which could readily be assigned to the Zn 2p3/2 and Zn 2p1/2 signals, respectively, of Zn2+ species (Supplementary Fig. 10)55–57. The Ru 3d XPS spectrum for py-RuO2:Zn showed intense peaks at ~281.0 and 285.0 eV (3:2 area ratio), which could readily be assigned to the 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 orbitals, respectively, of Ru4+ in RuO2 (Supplementary Fig. 11)32,58. Corresponding Ru4+ shake-up satellites were seen at ~283.1 and 287.2 eV, with the C 1 s peak of adventitious hydrocarbons being buried under the Ru 3d signal. The Ru 3d peaks for py-RuO2:Zn and py-RuO2 were positively shifted by about 0.3−0.4 eV compared with data for the commercial RuO2 powder catalyst (c-RuO2), indicating a variation of the local chemical environment at Ru sites (possibly originating from particle size effects)58,59. Peaks in less intensity were further observed at ~282.0 and 286.2 eV, assigned to the 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 orbitals, respectively, of Ru3+ in RuO258. The abnormally positive shifts in binding energies are caused by the coordination with hydroxyl adsorbates58,60. In fact, non-stoichiometric Ru3+ species generally exist in RuO2 films prepared by thermal decomposition of RuCl3 precursors61,62. The Ru 3p3/2 spectra for the different catalysts showed a main peak at 462.9 eV confirmed the predominance of Ru4+ species in all samples (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 12)45,58,59. A weak peak at 464.7 eV showed the presence of some Ru3+ species58,60. The integrated area of the Ru3+/Ru4+ signals was then calculated to examine the relative abundance of Ru3+ in the different catalysts. As shown in Supplementary Table 2, the Ru3+/Ru4+ ratio was similar for c-RuO2 (0.25) and py-RuO2 (0.31), but increased considerably on going to py-RuO2:Zn (0.55), suggesting that Zn doping increased the concentration of Ru3+ species. The higher content of low-valent Ru species on the surface of py-RuO2:Zn catalyst remained under the OER conditions, as confirmed by the Raman measurements (Supplementary Fig. 13). Since the TEM data in Fig. 1i confirmed the presence of the rutile phase in py-RuO2:Zn, a higher Ru3+ concentration suggested abundant oxygen vacancy (VO) defects in the catalyst. The O 1 s XPS spectra validated this hypothesis. As shown in Fig. 2b, the O 1 s spectra showed peaks below 530.0 eV due to lattice oxygen of RuO2 (OL−Ru) and TiO2 (OL−Ti, from the thin oxide layer on the Ti substrate in cracked areas of the film), and the peaks at 530.5, 531.5, and 533.0 eV due to O atoms in the vicinity of VO defect (OV), chemisorbed hydroxyl groups (OOH), and surface-adsorbed H2O (H2Oads), respectively63–65. Clearly, the intensity of OV peak increased on going from pure c-RuO2 to py-RuO2:Zn. The OV/OL−Ru ratio on py-RuO2:Zn (1.63) was more than twice that of c-RuO2 (0.67) (Supplementary Table 2). Good linear relationships were further recognized between the concentrations of OV and OOH and the abundance of Ru3+ species (Supplementary Fig. 14), again proving the change in the coordination of Ru sites in the catalyst. In summary, the XPS results reveal that Zn doping caused more low-valent Ru3+ species and VO defects in the RuO2 structure, both of which would impact the activity and durability of RuO2-based catalysts for acidic OER33,42.

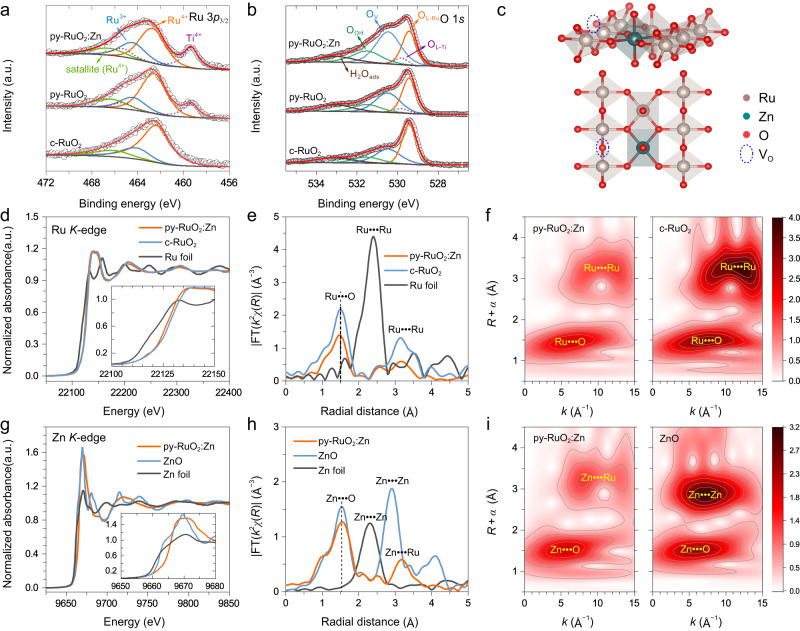

Fig. 2. XPS and XAS characterizations of py-RuO2:Zn.

a Ru 3p3/2 and b O 1 s core level XPS spectra for the py-RuO2:Zn, py-RuO2, and c-RuO2 catalysts. c Simulated structure of the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst. d Normalized Ru K-edge XANES and e Ru K-edge FT-EXAFS spectra of py-RuO2:Zn, c-RuO2, and Ru foil. f Ru K-edge WT-EXAFS spectra of py-RuO2:Zn and c-RuO2. g Normalized Zn K-edge XANES and h Zn K-edge FT-EXAFS spectra of py-RuO2:Zn, ZnO, and Zn foil. i Zn K-edge WT-EXAFS spectra of py-RuO2:Zn and ZnO.

XPS probes the top few nanometers in materials. To gain more comprehensive insights about the bulk electronic structure of the py-RuO2:Zn catalysts, we carried out X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) measurements at the Ru K-edge and Zn K-edge. Figure 2d shows Ru K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra for py-RuO2:Zn, Ru metal foil, and pure RuO2 powder. The absorption edge positions for py-RuO2:Zn and RuO2 were at higher energy compared to that of the Ru foils, reflecting the higher oxidation state of Ru in the oxide materials. The absorption edge of py-RuO2:Zn was at slightly lower energy than for the c-RuO2, suggesting a slightly lower Ru valence state in py-RuO2:Zn. Calculations on basis of adsorption edge energy revealed that an average oxidation state of Ru species in the catalyst was approximately +3.4 (Supplementary Fig. 15), which was considered as the combination of pristine Ru4+ and Ru3+ cations. The Zn K-edge XANES spectra for py-RuO2:Zn, ZnO powder, and Zn foil are shown in Fig. 2g. The spectrum for py-RuO2:Zn was quite distinct to those of the references samples, revealing a Zn2+ oxidation state but without the fine structure associated with ZnO. The “white line” feature of py-RuO2:Zn was considerably broader than that of the bulk ZnO reference and did not show the characteristic ZnO shoulder at ~9663 eV66,67. The results indicate that the coordination of Zn2+ atoms in py-RuO2:Zn was different to the tetrahedral Zn−O coordination found in wurtzite ZnO, with the obvious explanation being the adoption of an octahedral structure through substitutional doping of Zn at Ru sites in the RuO2 lattice66,67.

We note that when the Zn dopants took an octahedral coordination structure through substitutionally doping at Ru sites in the RuO2 lattice, a fraction of the Ru will, in principle, be oxidized above +4 to accommodate the divalent metal, associated with a generation of stoichiometric oxide30. However, when oxygen vacancies (VO) present, the oxidation state of Run+ (n > 4) would be reduced. Recently, Liu and colleagues reported a Na-doped amorphous/crystalline RuO2 catalyst containing more low-valent Run+ (n < 4) species with the presence of high abundant VO defects40. To further understand the role of Zn doping on the generation of VO defects, the relationship between Zn content and VO concentration was analyzed on basis of XPS results. A linear dependence of OV/OL-Ru on the Zn content was found (Supplementary Fig. 16), indicating that the doping of Zn element can induce the generation of VO defects. In the meantime, the presence of Ru3+ and VO defects was also found in the undoped py-RuO2 catalyst, seemly caused by the catalyst synthesis method used here61,62. Thus, it can conclude that the Zn doping, in addition to the catalysis synthesis method, has induced the generation of VO defects and the low-valent Ru sites.

Figure 2e shows Fourier transformed (FT) k2-weighted Ru K-edge extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra for py-RuO2:Zn and relevant reference samples. The main peaks at 1.50 and 3.14 Å for pure RuO2 correspond to the first Ru−O and Ru−Ru coordination shells of Ru cations31,68, respectively. For py-RuO2:Zn, these sample features were observed at 1.47 and 3.17 Å, respectively, indicating a slight change in Ru cation coordination environment with Zn doping. Compared with RuO2, py-RuO2:Zn showed reduced intensities for both Ru−O and Ru−Ru peaks, suggesting that the coordination number of Ru sites was decreased69, consistent with the presence of VO defects. Further, the substitutionally doping of Zn would make the second peak a mixture of Ru−Ru and Ru−Zn scattering. In addition, the Zn K-edge EXAFS spectrum of py-RuO2:Zn in Fig. 2h closely resembled the Ru K-edge spectrum, suggesting an octahedral-like Zn coordination (Supplementary Fig. 17). The first peak observed at 1.55 Å in the Zn K-edge R-space plot for py-RuO2:Zn, assigned to the first Zn−O coordination shell, was longer than the 1.47 Å for Ru−O bonds (as expected since Zn2+ has a lower charge than Ru4+). The second strong peak at 3.18 Å was longer than the Zn−Zn shell distance in ZnO (2.91 Å), being more comparable to the Ru−Ru distance (3.17 Å) in py-RuO2:Zn or c-RuO2 (3.14 Å). Previously, Petrykin and colleagues reported similar Zn K-edge EXAFS spectra for Ru1−xZnxO2 (x ≤ 0.2) materials and assigned the peak located at ~3.1 Å to Zn−Ru backscattering at Zn sites based on a structural fitting analysis48. We believe, the peak at 3.18 Å in the Zn K-edge spectrum of py-RuO2:Zn has the same origin, arising from substitution of Ru ions by Zn ions in the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst. The wavelet transform (WT) EXAFS measurements provided further confirmation for this assignment (Fig. 2f and i, and Supplementary Fig. 18). The maximum-intensity Ru K-edge values for py-RuO2:Zn were observed at k ≈ 6.5 and 12.5 Å−1, attributed to Ru−O and Ru−Ru/Zn scattering paths (Fig. 2f), respectively. These features were weaker than those of the reference RuO2 sample, which may have been due to the nanosize of the py-RuO2:Zn nanowires and also the mixed Ru-Ru/Zn coordination shell. The Zn K-edge WT plot of py-RuO2:Zn in Fig. 2i showed a similar contour profile to the Ru K-edge plot in Fig. 2f. On basis of the observations, the model crystal structure for py-RuO2:Zn could be proposed (Fig. 2c) based on the rutile structure of pure RuO2 with partial substitution of Ru atoms by Zn atoms. The introduction of Zn2+ ions promotes the formation of oxygen vacancies in the near vicinity. The loss of O at the vertex of the RuO6 octahedra would lower the average Ru valence, which has particular relevance to the OER performance33,68.

Electrocatalytic performance of py-RuO2:Zn toward acidic OER

The OER activity of the as-prepared py-RuO2:Zn catalyst was examined in an O2-saturated 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolyte using a conventional three-electrode set-up. The Ag/AgCl reference electrode was first calibrated against the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) (Supplementary Fig. 19). For comparison, the activities of py-RuO2 and c-RuO2 were also measured under identical conditions. In order to minimize the background capacitive current, the linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves reported were obtained by taking the average results of the positive/negative-going scans of a cyclic voltammetry curve (CV) (Supplementary Fig. 20a). The capacitance-corrected LSV curve was then performed an 85% iR-compensation correction (Supplementary Fig. 20b)70. The CV curves shows no obvious degradation during the first 30 cycles on py-RuO2:Zn (Supplementary Fig. 21), implying that the pristine surface offered high OER activity without the need for pre-activation treatment71. Figure 3a displays the LSV results of OER on the different catalysts. The sharply rising anodic current related to the OER process appeared at more negative potentials on py-RuO2:Zn compared to pure c-RuO2. The associated OER onset potential was ~1.33 V (vs RHE), corresponding to an overpotential (η) of ~100 mV, much lower than those of py-RuO2 (~1.38 V, η ≈ 150 mV) and c-RuO2 (~1.42 V, η ≈ 190 mV) (Supplementary Fig. 22)72. Accordingly, the OER process is a more easily triggered on py-RuO2:Zn. The superior OER activity of py-RuO2:Zn was retained on increasing the current density. To achieve a current density of 10 mA cm−2, py-RuO2:Zn required a low potential of 1.403 V (η = 173 mV), outperforming py-RuO2 (1.458 V, η = 228 mV) and the commercial c-RuO2 reference catalyst (1.521 V, η = 291 mV)40,73. At a higher overpotential of η = 300 mV, py-RuO2:Zn achieves a current density of 476 mA cm−2, which was 4.4 and 36.1 times as larger than values for py-RuO2 and c-RuO2, respectively (Fig. 3c). Moreover, the OER process can be polarized to an industrial current density of 1.0 A cm−2 on py-RuO2:Zn catalyst, operating at a very competitive potential of 1.603 V (η = 373 mV) (Fig. 3b)33,73. Such a large current density can be reached more than five continuous CV cycles, but accompanied by a gradually degradation in the OER activity (Supplementary Fig. 23). The faradaic efficiency (FE) of OER on py-RuO2:Zn catalyst was measured by the water displacement method under the chronopotentiometric condition at current densities of 25 and 40 mA cm−2. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 24, the measured oxygen amount fits well with the theoretical values calculated from Faraday’s law of electrolysis, approaching ~99% and ~100% FE at 25 and 40 mA cm−2, respectively. Notably, the OER activity of py-RuO2:Zn was greatly affected by the conditions of catalyst preparation (Supplementary Figs. 5−7), with the optimal OER performance being achieved with a regular nanowire morphology on Ti plate.

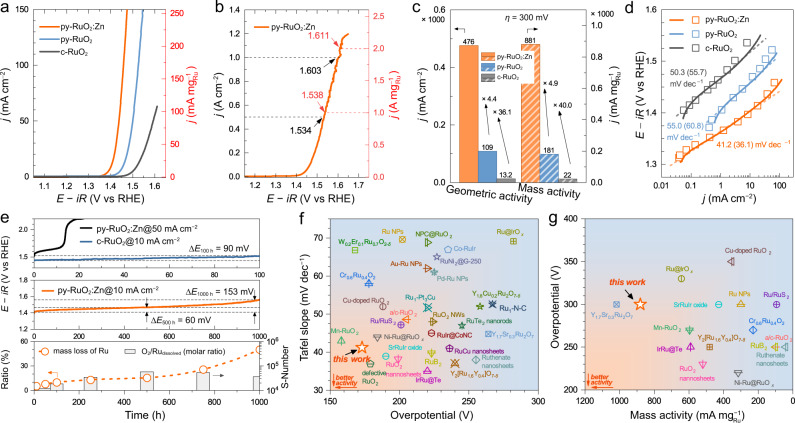

Fig. 3. OER performance of py-RuO2:Zn in acidic media.

a Geometric area and Ru mass normalized LSV curves with 85% iR-correction of py-RuO2:Zn, py-RuO2, and c-RuO2 for OER in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution (pH = 0.30 ± 0.01) with O2 saturation. Solution resistances for iR-correction are 2.8, 2.6, and 4.5 Ω for py-RuO2:Zn, py-RuO2, and c-RuO2, respectively. Mass loadings of Ru metal are 0.52, 0.60, and 0.60 mg cm−2 for py-RuO2:Zn, py-RuO2, and c-RuO2, respectively. b Geometric area and Ru mass normalized LSV curve of py-RuO2:Zn for OER under high current density. c Comparisons of OER geometric and mass activities at an overpotential of 300 mV on py-RuO2:Zn, py-RuO2, and c-RuO2. d Tafel plots derived from the LSV curves (solid line) and the steady-state polarization curves (scatters). Values in parentheses were derived from steady-state polarization curves. e Chronopotentiometric stability tests of py-RuO2:Zn and c-RuO2 (upper plot: 100 h at 50 mA cm−2; middle plot: 1000 h at 10 mA cm−2) and mass loss analysis of Ru and corresponding stability number (S-Number) on py-RuO2:Zn during the stability test determined by ICP-MS (lower plot). Comparison of overpotentials and f Tafel slopes, and g mass activities for py-RuO2:Zn and other recently reported high performance RuO2-based OER catalysts.

To evaluate the intrinsic OER performance of the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst, we further calculated the mass activity according to the total loading of Ru metal determined by ICP-MS (Supplementary Table 1). As shown in Fig. 3a, the OER mass activity of the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst greatly surpassed those of py-RuO2 and c-RuO2. A current density of 100 mA can be achieved at a low potential of 1.442 V (η = 212 mV) on py-RuO2:Zn, whereas 1.508 V (η = 278 mV) and 1.607 V (η = 377 mV) were required on py-RuO2 and c-RuO2, respectively. At η = 300 mV, py-RuO2:Zn delivered a current density up to 881 mA (Fig. 3c). In contrast, just 181 mA was realized on py-RuO2 and 22.0 mA on c-RuO273. The remarkable OER activity of the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst well retained at high current densities, evidenced by values of 1.538 V@1.0 A and 1.611 V@2.0 A (Fig. 3b). It is also worth noting that the OER activity of py-RuO2:Zn greatly surpassed those of reported Zn-doped RuO2 catalysts30,48,74. A rutile-type Zn0.19Ru0.81O2 was previously studied by Burnett and colleagues30. Although the Zn0.19Ru0.81O2 catalyst reported in that work displayed an OER activity better than commercial RuO2, its performance was vastly inferior to the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst in the current study, with OER activity at η = 300 mV only reached at 60 mA . Actually, Zn0.19Ru0.81O2 was reported to possess a defect-free stoichiometric oxide. The fully occupied oxygen sites were proposed to require a higher average Ru oxidation state (above +4) to balance charge, which is obviously different to the structure of the defective py-RuO2:Zn catalyst. The difference in crystal structure of the Zn-doped RuO2 catalysts explains the variation in OER performance between our work and that of Burnett and colleagues30. Recently, a surface evolution of Zn-doped RuO2 under the reaction was found to enable a construction of surface defects (e.g., VO defects) and active Ru sites75, consistent with the theoretically predicted results on RuO2 catalyst39. A low overpotential of 190 mV and a good stability up to 60 h were observed at the current density of 10 mA cm−2 on this surface etched catalyst. Next, the electrochemical active surface area (ECSA) was calculated for the different catalysts and used to normalize the OER current, in order to eliminate the effect of catalyst morphology. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 25, py-RuO2:Zn possessed a much larger ECSA and a higher specific OER activity compared to the pure RuO2 catalysts studied in this work, largely due to the significant difference in the morphology of them (Supplementary Fig. 5). Figure 3d shows the Tafel slope analyses for the different catalysts. The plots were derived from the iR-corrected LSV curves and the steady-state polarization curves (Supplementary Fig. 26)76. Clearly, py-RuO2:Zn offered the lowest Tafel slope of 41.2 (36.1) mV dec−1, suggesting faster OER kinetics compared to the py-RuO2 and c-RuO2 catalysts25,73. A Tafel slope around 40 mV dec−1 implies a better kinetics of the OHads deprotonation to form Oads and the O−O bond formation8,77. Moreover, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) results (Supplementary Figs. 27−28, and Supplementary Table 3) showed that the charge transfer resistance (Rct) was significantly smaller on py-RuO2:Zn than it on pure py-RuO2, for instance, 9.0 Ω and 114.7 Ω at 1.40 V, respectively, further proving a much faster charge transfer rate of OER and thereby an improved reaction kinetics on py-RuO2:Zn. In summary, the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst demonstrated excellent OER activity compared to the pure RuO2 reference catalysts and state-of-the-art performance compared to RuO2-based acidic OER catalysts recently reported (Fig. 3f, g, and Supplementary Table 4).

Next, catalytic stability of py-RuO2:Zn during OER was investigated using a chronopotentiometric (CP) method at a constant current density. As shown in Fig. 3e, py-RuO2:Zn displayed far better stability than the c-RuO2 catalyst. At a typical current density of 10 mA cm−2, the OER potential on py-RuO2:Zn increased by only 60 mV during the initial 500 h of testing and by only 153 mV over 1000 h of testing. In contrast, the c-RuO2 catalyst dramatically lost activity over 15 h under identical conditions41,73. At a higher current density of 50 mA cm−2, py-RuO2:Zn showed excellent stability over 100 h with an overpotential increase of only 90 mV (Fig. 3e), while potential increase was 70 mV after a test at the current density of 100 mA cm−2 for 24 h (Supplementary Fig. 29). The good stability of py-RuO2:Zn was further investigated under the CV cycling condition. The potential at 100 mA cm−2 was increased by about 28 mV after a 2000-cycles test (Supplementary Fig. 30). Compared with recently reported RuO2-based catalysts, the stability of py-RuO2:Zn was also more distinguished (Supplementary Table 4). For example, the degradation of the OER overpotential (ΔE) at 10 mA cm−2 for py-RuO2:Zn was much smaller than that reported for the best Ru/α-MnO2 (ΔE = 169 mV@200 h) and LixRuO2 (ΔE = 120 mV@70 h) catalysts under similar testing conditions35,41. During the stability test, the dissolution of Ru from py-RuO2:Zn catalyst was determined by ICP-MS. Figure 3e (lower plot) shows the mass loss of Ru normalized against the initial Ru loading in freshly prepared py-RuO2:Zn. Three distinct stages were seen in the Ru dissolution profile. During the initial 100 h, ~10% Ru loss occurred with the loss increasing slowly to ~15% after 500 h. In the final 1000 h, the Ru loss increased to ~50%. This trend is generally consistent with the performance degradation behavior seen for the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst in the CP stability test (Fig. 3e, middle plot). The OER potential shows an increase of 28 mV, from 1.408 V to 1.436 V, in the first 100 h test, followed by a further 32 mV increase from 1.436 V to 1.468 V between 100 h and 500 h. Finally, a larger 93 mV increase, from 1.468 V to 1.561 V, was found between 500 h and 1000 h. Consequently, although the OER potential degradation of py-RuO2:Zn was very modest over 1000 h (compared to previously reported RuO2 catalysts in acidic media), the ~50% Ru mass loss at the end of the tests indicated serious corrosion in the latter stages, which was then confirmed by post-stability test SEM imaging and optical photographs (Supplementary Fig. 31). In addition, stability number (S-number), a recommended metric to quantify the catalyst stability during the reaction78, was calculated by normalizing the moles of O2 evolved () with the moles of Ru dissolved (), i.e., S-number = 38. As shown in Fig. 3e lower plot, the S-number exhibited an increase in the initial 500 h and then a decrease in the following 500 h. A top value of ~6 × 104 was obtained, which is comparable to those observed on Ru-based pyrochlores38. We also note that the mass loss of Ru up to ~15% within 500 h from the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst seems to be serious for industrial applications. However, the corresponding dissolution rate of Ru, 0.156 , is much lower than that of the commercial RuO2 (~40 ). Further compared with the high active RuO2-based acidic OER catalysts recently reported (Supplementary Table 5), the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst also ranks the top-level of stability in terms of the Ru dissolution rate. When normalized by the ECSA, a value of 37.6 for Ru dissolution rate was obtained on the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst, significantly lower than the ~1.05 on commercial RuO2, indicating an intrinsically improved stability of the catalyst.

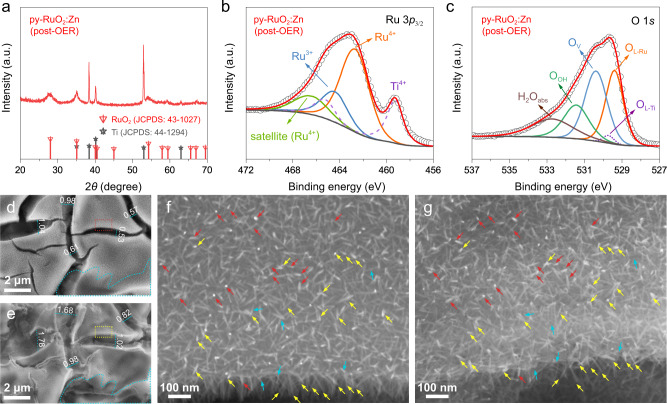

In order to gain deeper insights about py-RuO2:Zn catalyst degradation during acidic OER, we performed a further durability test at 10 mA cm−2 for 350 h (Supplementary Fig. 32). The 350 h was selected on basis of the apparent inflection point in the Ru dissolution curve (Fig. 3e, lower plot). XRD revealed that the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst retained a rutile structure after 350 h (Fig. 4a). The core level Ru 3d, Ru 3p3/2, and O 1 s XPS spectra showed a slight decrease in the concentrations of Ru3+ species and VO defects on the surface (Fig. 4b, c, Supplementary Fig. 33, and Supplementary Table 2). No obvious change was found in the Zn 2p XPS spectra (Supplementary Fig. 34). Quasi-in situ SEM measurements taken at some pre-marked locations before and after the OER stability test were used to study Ru dissolution from the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst. Some corrosion was observed in the catalyst coating on the Ti plate after the test (Supplementary Fig. 35), accompanied by an expansion of the original coating cracks (Fig. 4d−e). The corrosion appears to begin preferentially at the edges of the cracks and then gradually expand into the plateau domains. A close comparison (marked by arrows) revealed that the majority of py-RuO2:Zn nanowires retained their original locations and morphologies (marked by red arrows), especially those far from the cracks. Nanowires near the cracks showed more obvious changes in their spatial directions and morphologies (marked by yellow arrows). A few nanowires disappeared completely after the 350 h of testing (marked by cyan arrows). Optical images (Supplementary Fig. 31c) revealed that the py-RuO2:Zn coating remained in a good condition after the 350 h test, showing good adhesion and a uniform dispersion of elements (Supplementary Fig. 36), which is consistent with a relatively slow mass loss of Ru during the first 500 h of OER testing (Fig. 3e, lower plot). Results suggest that there is likely a threshold potential that determines the dissolution rate of Ru in the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst during OER, above which dissolution proceeds very rapidly. Based on the CP results, this threshold potential appears to be ~1.46 V (Supplementary Fig. 37). Anodic polarization higher than 1.46 V will result in accelerated corrosion of the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst. The accelerated degradation of py-RuO2:Zn at potentials above 1.46 V was further observed under a CP test at 100 mA cm−2, which exhibited a faster increase of overpotential by 70 mV within 24 h (Supplementary Fig. 29). The result agrees with the previous reports on the stability window of RuO2-based catalysts6,79,80. Although the stability of py-RuO2:Zn did not obviously break the reported potential limit, the onset overpotential of OER was significantly reduced, providing a widened stability window to the application of py-RuO2:Zn. Furthermore, we find that the potential of 1.46 V is close to the inflection region in the Tafel plot (Supplementary Fig. 38), indicating a change in the rate-determining step of OER with the change in Ru dissolution rate8,77.

Fig. 4. Stability analysis of py-RuO2:Zn for acidic OER.

a XRD pattern, b Ru 3p3/2 and c O 1 s XPS spectra of py-RuO2:Zn catalyst post OER test. Quasi-in situ SEM images of the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst d, f before and e, g after a continuous OER test at 10 mA cm−2 for 350 h. The red and yellow arrows indicate nanowires that retained or slightly lost their morphologies during OER, respectively, whilst the cyan arrows indicate nanowires that completely disappeared after the test.

Insights into OER process and relevant mechanism

On the LSV curve for OER (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 22), low onset potential (~1.33 V) and overpotential (173 mV at 10 mA cm−2) were observed and have been assigned to an anodic OER process on the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst. Such low threshold potentials are impressive because they well exceeded the theoretical limit of OER onset overpotential (~250 mV) on the optimal catalyst, based on the adsorbate evolution mechanism (AEM) involving single active metal site and the linear scaling relationships between the adsorption energies of *O, *OH, and *OOH intermediates (ΔEOOH = ΔEOH + 3.2 eV ± 0.2 eV)36,81. We then performed experiments using a rotating ring-disk electrode (RRDE) setup and confirmed the explicit contribution of OER process to the observed anodic current at potentials around 1.40 V (Supplementary Fig. 39). Thus, the low threshold potentials of OER suggested that there may be other paths of OER on the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst in addition to the AEM, especially at low overpotentials. Recently, Scott and colleagues performed a trace detection of O2 and found an electrochemical generation of O2 from OER on the RuOx catalyst at the potential as low as 1.30 V82. Further by comparing the trends in Ru dissolution and oxygen evolution, they suggested a negligible contribution of lattice oxygen evolution to the overall OER activity for RuOx in acidic media22. A comprehensive theoretical study on the recently reported mechanisms of OER revealed that the presence of nonelectrochemical steps (e.g., *OO dimer formation/desorption) tends to increase rather than to reduce the thermodynamic overpotential of OER, while the presence of surface defects (e.g., VO defects) probably alters the configuration of adsorbed intermediates to improve the OER activity83.

In this work, a high concentration of VO defects and low-valent Ru species existed in the py-RuO2:Zn catalyst, which may play important roles in improving the OER property31,41, in addition to the catalyst electrical conductivity (Supplementary Fig. 28 and Supplementary Table 3)84. When plotting specific current densities against the VO concentrations, a good linear relationship was established, revealing a clear impact of VO defects on the OER activity (Supplementary Fig. 40). However, the lower oxidation state of Ru sites and higher concentration of VO defects were expected to result in much stronger *OH adsorption and be detrimental to the OER activity of RuO2-based catalysts, based on the linear scaling relationships between the adsorbates binding energies following conventional AEM path36,81. Accordingly, enhancement on OER activity was achieved when there were high-valent Ru sites and less VO defects37,38. This seems conflict with our result that an enhanced OER activity was obtained on VO defects containing Zn-doped RuO2 catalyst. We speculated that the positive effect of VO defects on OER activity was realized with the assistance of the Zn dopants. VO defect and Zn dopants can synergistically regulate the coordinative environment and electronic structure of vicinal Ru centers and thus optimize the binding configurations of OER intermediates40,41,85. Consequently, the OER activity may be improved.

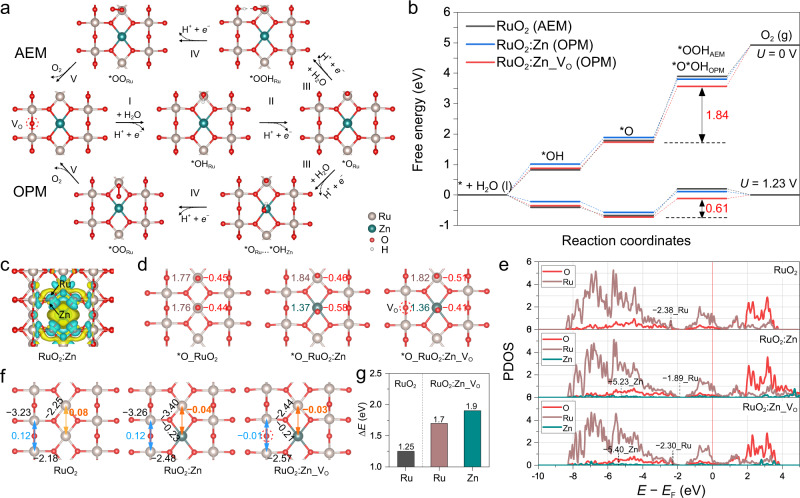

To understand the Zn doping and oxygen vacancies effect on the OER activity, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed. The Zn doped RuO2 (RuO2:Zn) and that with O vacancies (RuO2:Zn_VO) were built on the optimized RuO2 (110) surfaces (Supplementary Fig. 41). Zn was found to be more stably doped at the coordinatively unsaturated Ru (Rucus) position than the fully coordinated bridge Ru (Rubri) site, while the bridge row O could form stable vacancy site. Then, different OER paths were investigated to determine the preferred reaction pathways, including the AEM and lattice oxygen mechanism (LOM), as well as the recently highlighted dual-site oxide path mechanism (OPM) (Supplementary Fig. 42)35,83. The adsorption energies of reaction intermediates were summarized in the Supplementary Table 6. For clean RuO2, stronger binding of OH adsorbates (ΔGOH = 0.82 eV) resulted in the OER proceeding favorably via a AEM path, following the four-proton-coupled electron transfer steps as H2O → *OH → *O → *OOH → O236. The formation of *OOH is the rate-determining step (RDS) with a large free energies barrier of 2.10 eV. By comparison, the LOM and dual site OPM paths are suppressed with much higher energy barriers of RDS (ΔGmax for LOM 3.79 eV and OPM 2.48 eV, where ΔGmax is the maximum free energy differences among the primary proton-coupled electron transfer steps) (Supplementary Fig. 43). For RuO2_VO, the presence of bridged O vacancies caused accumulated charge density at both the vicinal Rubri and Rucus sites (Supplementary Fig. 44), which then enhanced the binding of *OH at Rucus centers (ΔGOH = 0.70 eV) and induced a larger free energies barrier of 2.28 eV for *OOH formation (Supplementary Fig. 45). Therefore, the presence of VO defects is harmful to the OER proceeding on RuO237,38. In contrast, on the surface of stoichiometric RuO2:Zn oxide, the doping of Zn at Rucus sites induced a reduction of the charge density at Ru centers, which agreed with the knowledge that a fraction of the Ru will be oxidized above +4 to accommodate the divalent Zn metal30. As a result, the *OH binding is weakened (ΔGOH = 1.01 eV) and the OER activity is improved. More interestingly, a Ru−Zn dual-site OPM appeared to be more favorable with a lower ΔGmax of 1.91 eV for the third proton-coupled electron transfer step (*ORu → *ORu…*OHZn), caused by the different binding strength of intermediates on the two sites (Supplementary Fig. 46). The density of sates (DOS) and charge density difference suggested that Zn donated some electron to the O and Zn had a lower d-band center than Ru (Fig. 5c−e). Therefore, Zn showed weaker absorption of *O, *OH, and *OOH. For example, Zn sites had a ΔGOH of 1.77 eV, while Ru site had a ΔGOH of 1.01 eV. This would ease the formation of second *O. In addition, the charge difference between Zn and Ru also played an important role in promoting the OER, which resulted in a ~ 0.1 e charge difference for the two absorbed *O on Zn and Ru and thus promoted the formation of O−O coupling, and eventually the formation of O2 (Fig. 5d). With the presence of VO defects, the charge density at both the Rucus and Zncus sites on RuO2:Zn_VO surface is slightly increased (Supplementary Fig. 44), associated with a shift of Ru d-band center away from Fermi, which further optimized the absorption of intermediates (Fig. 5e). Consequently, the ΔGmax (*ORu → *ORu…*OHZn) of OPM is further decreased to 1.84 eV for RuO2:Zn with VO defects (Fig. 5b). Therefore, we believed that the down shift of Fermi by O vacancy, the weaker absorption of *OH on Zn and the charge difference of Zn and Ru synergistically lowered the OER overpotential () from 0.87 V for RuO2 to 0.61 V for the O vacancy-containing Zn doped RuO2, by converting the OER path from the single-site AEM to the dual-site OPM (Fig. 5a, b).

Fig. 5. OER mechanism analysis.

a AEM and OPM paths of OER on the RuO2:Zn_VO surface. b The free energy diagrams for preferred OER paths on the surfaces of RuO2, RuO2:Zn, and RuO2:Zn_VO. c Differential charge density analysis of RuO2:Zn. The blue and yellow shaded area mean the electron density accumulation and donation. d Bader charge analysis for Ru (brown), Zn (dark cyan), and O (red) sites on the double *O adsorbed surfaces of RuO2, RuO2:Zn, and RuO2:Zn_VO. e PDOS of Ru 4d, O 2p, and Zn 3d-bands for RuO2, RuO2:Zn, and RuO2:Zn_VO; corresponding d-band centers are denoted by dashed lines. f ICOHP analysis of Ru−O, Ru···Ru, Ru···Zn, and Zn−O on the surfaces of RuO2, RuO2:Zn, and RuO2:Zn_VO. g De-metallization energies of Ru from RuO2, and Ru and Zn from RuO2:Zn_VO.

In terms of the stability enhancement, the present dual-site OPM path of OER avoids the step of *O → *OOH, which generally proceeds above 1.3 V on single Ru site86. Thus, it was possible to stabilize the OER active sites against the excessive oxidation under the OPM path. We then studied the electrochemical redox features of the Ru species on py-RuO2:Zn, py-RuO2, and c-RuO2 catalysts in potential regions preceding OER process (Supplementary Fig. 47). Compared with those on py-RuO2 and c-RuO2, the redox peaks of Ru4+/ Run+ (n > 4) above 1.2 V were significantly suppressed on py-RuO2:Zn, indicating an efficient protection on Ru cations from over oxidation to soluble species21,87,88. Consequently, the catalytic stability of py-RuO2:Zn for OER would be enhanced. To gain more insights into the effect of Zn doping and VO defects on the structure stabilization of RuO2, the crystal orbital Hamilton population (COHP) of Ru−O and Zn−O bonds, as well as Ru···Ru and Ru···Zn metal couplings, were analyzed on the optimized RuO2, RuO2:Zn, and RuO2:Zn_VO surfaces. As shown in Fig. 5f, the integrated COHP (ICOHP) values of Rucus−O for RuO2:Zn, and RuO2:Zn_VO are −3.40 eV and −2.44 eV, respectively, which have been negatively shifted from that for pristine RuO2 (−2.25 eV), thereby revealing a strengthened Rucus−O bond on those Zn-doped samples. In addition, small negative ICOHP values of Rucus···Zn were found on both the RuO2:Zn (−0.04 eV) and RuO2:Zn_VO (−0.03 eV) with the Zn doping, indicating a weak long range orbital coupling between Zn dopants and the vicinal Rucus sites. In contrast, there is no clear interaction of Rucus···Rucus (0.08 eV for ICOHP) on the pristine RuO2. Accordingly, the Rucus sites would be further stabilized by the Zn dopants. When bridged VO defects present, the ICOHP of Rubri···Rubri for RuO2:Zn_VO also acquired a small negative value of −0.01 eV, while it was a positive value of 0.12 eV on both the RuO2 and RuO2:Zn. This indicated an enhanced interaction between two adjacent Rubri sites in the vicinity of VO defect. The enhanced stability of Zn doped RuO2 with Vo is also demonstrated by the de-metallization energies of Ru and Zn (Fig. 5g). The doping of Zn induced an increased de-metallization energy of Ru by around 0.5 eV and thus stabilized the RuO2. The Zn dopants themselves possessed relatively higher de-metallization energies by around 0.2 eV than the Ru in RuO2:Zn_VO. The overall results suggested that the RuO2 structure become more stable after the introduction of Zn dopants and VO defects.

In summary, Zn-doped RuO2 nanowire arrays with outstanding performance of acidic OER were successfully synthesized by a simple pyrolysis method. The substitutionally doping of Zn both regulated catalyst morphology and created an abundance of VO defects and low-valent Ru sites. The self-supporting py-RuO2:Zn nanowires (on Ti) exhibited impressive activity and durability for OER in 0.5 M H2SO4, evidenced by low overpotentials of 173, 304, and 373 mV at 10, 500, and 1000 mA cm−2, respectively, and very modest degradations during continuous tests at 10 mA cm−2 for 1000 h and 50 mA cm−2 for 100 h. Theoretical studies showed that the VO defects and Zn dopants caused an weakened binding of oxygen adsorbates at active Ru centers and, more interestingly, enabled a moderate adsorption of *OH species on Zn sites. As a result, the OER path was altered from the conventional AEM to a Ru−Zn dual-site OPM, thereby significantly enhancing the OER activity. In the meantime, the OPM path avoided the over oxidation of the OER metal sites and thus protected the active centers, and the presence of Zn dopants and VO defects enabled a structure stabilization of RuO2 matrix. Consequently, an excellent OER stability was obtained on the VO-containing Zn-doped RuO2 oxide.

Methods

Preparation of py-RuO2:Zn on metallic Ti plate

Ti plate was first etched in 10 wt.% oxalic acid solution at 95 °C for 2 h to remove the surface oxide, then rinsed with copious deionized water and dried in air. Amount of aqueous solution containing RuCl3 and Zn(NO3)3 with controlled mole ratio of Zn/Ru and dosage of Ru3+ cation was pipetted onto the freshly cleaned Ti plate with a confined area of 0.5 × 1.0 cm2. The obtained precursor coating was dried naturally in air and then pyrolyzed in a muffle furnace at 350 °C for 4 h in air (ramping rate: 5 °C min−1) to transform the precursors to metal oxide. After naturally cooled to room temperature, the sample was then etched in 1.0 M HCl aqueous solution to remove the unwanted ZnO species. The resulted sample was rinsed with copious water and dried in air. To optimize the morphology and OER performance of py-RuO2:Zn catalyst, the conditions of preparation were screened, including the Zn/Ru mole ratio (0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 5.0) and Ru3+ dosage (1.0, 3.0, 6.0 μmol cm−2) in the precursor solution, and the reaction temperature (300, 350, 400, 450, 500 °C) of pyrolysis. The results revealed that py-RuO2:Zn catalyst with regular nanowire array appearance and the best OER property can be controllable constructed under the conditions: 0.5, 6.0 μmol cm−2, and 350 °C for the Zn/Ru mole ratio, Ru3+ dosage, and reaction temperature, respectively.

For comparison, pure RuO2, referred as py-RuO2, was also prepared by the pyrolysis method under the optimal conditions without the addition of Zn precursor. The commercial RuO2, referred as c-RuO2, purchased from Sigma Aldrich was also used as a control sample for comparison. In addition, other materials, such as carbon fiber paper (CFP) and fluorine-doped tin oxide glass (FTO), were then used to replace the Ti plate in the fabrication of py-RuO2:Zn nanowire arrays coating under the identical conditions, in order to examine the practicability of this method on different substrates.

Physical characterizations

Scanning electron microscopic (SEM) images and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis were obtained with Merlin Compact (Carl Zeiss NTS GmbH) at 15 kV. Grazing incidence XRD (GIXRD) patterns were performed on a Phillips PANalytical X’Pert Pro diffractometer operating at 40 mA and 40 kV using a curved graphite diffracted-beam monochromator with Cu Kα radiation (incident angle = 0.3° for GIXRD, λ = 1.541 Å). XRD patterns were recorded by the SmartLab (Rigaku) diffractometer with Cu-Kα radiation. High-resolution transmission electron microscopic (HRTEM) studies and high-angle annular dark-field scanning TEM (HADDF-STEM) analyses were performed on JEOL 2100 F at 200 kV. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) studies were carried out on Thermo ESCALAB 250XI using an Al Kα monochromated source (150 W, hν = 1486.6 eV). The X-ray absorption fine structure spectra (XAFS) were collected at BL14W beamline in Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF). The mass loadings of Ru and Zn in py-RuO2:Zn catalysts before and after the acid etching treatment were separately measured by ICP-MS method (Supplementary Table 1). To prepare the analytical solution, 5 mg of the py-RuO2:Zn powder scraped off the Ti substrate was dispersed in 20 mL solution containing HNO3, HCl, and HClO4 with the ratio of 4:12:3, then transferred into a hydrothermal 50 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave. Finally, the sample was sealed and treated at 180 °C for 72 h to fully digest all solid parts. The dissolution of Ru element was studied by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, Aglient 7800). Degradation of py-RuO2:Zn in duration test was monitored by taking a 1 mL sample of the electrolyte solution at different time after the test (1, 10, 50, 100, 250, 750, 1000 h) for ICP-MS analysis. The 1 mL sample was diluted with 0.5 M H2SO4 and 0.1 M HCl.

Electrochemical measurements

All electrochemical measurements were tested using a CHI 660E electrochemical analyzer (CH Instruments, Inc., Shanghai) in O2-saturated 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolyte. The pH of the electrolyte, 0.30 ± 0.01, was measured with a microprocessor-based pH-meter (Leici PHSJ-3F) and further calibrated by a reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE). A H-type three-electrode cell was used with a proton exchange membrane to separate each chamber. Saturated Ag/AgCl immersed in a double salt bridge and Pt plate served as the reference and counter electrodes, respectively. The Ag/AgCl reference electrode was first calibrated by a reversible hydrogen electrode, and the potential was reported on RHE scale with 85% iR-correction unless otherwise specified. Solution resistance (R = 3.2 ± 0.4, 2.9 ± 0.4, and 4.0 ± 0.6 Ω for py-RuO2:Zn, py-RuO2, and c-RuO2, respectively) was measured by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) at frequencies ranging from 10 Hz to 100 kHz. The current densities were calculated with respect to the geometrical area of the electrodes (0.5 × 1.0 cm2). Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) and cyclic voltammetry (CV) techniques were performed to examine the electrocatalytic performances of the as-prepared catalysts toward oxygen evolution reaction (OER) in acidic environments. A potential scan rate of 10 mV s−1 is used. Chronopotentiometric (CP) technique was employed for the long-term stability test of OER.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations

We have employed the Vienna Ab Initio Package (VASP)89,90 to perform all the density functional theory (DFT) calculations within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) using the RPBE91 formulation. We have chosen the projected augmented wave (PAW) potentials92,93 to describe the ionic cores and take valence electrons into account using a plane wave basis set with a kinetic energy cutoff of 450 eV. Partial occupancies of the Kohn−Sham orbitals were allowed using the Gaussian smearing method and a width of 0.05 eV. The electronic energy was considered self-consistent when the energy change was smaller than 10−6 eV. A 2 × 2 unit cell with 4-layers thickness was employed with 15 Å vacuum in the z axis to avoid image interactions. The bottom two layers were keep fixed while the top two layers were relaxed during geometry optimization. A geometry optimization was considered convergent when the force change was smaller than 0.05 eV/Å. Grimme’s DFT-D3 methodology94 was used to describe the dispersion interactions. The Brillouin zone integral uses the surfaces structures of 3 × 3 × 1 monk horst pack K point sampling. The de- metallization energies were computed as ΔE = Esurface − Eatom − Esurface-vac, where Esurface and Esurface-vac are the total energies of the surface and surfaces with one metal removed, Eatom is the single atom energies in the hexagonal Ru and Zn. The computational hydrogen electrode (CHE) approach was used which assumes that the chemical potential of a proton-electron pair is equal to that of gas-phase H2, at Uelec = 0 V vs. RHE. The reaction free energy of each proton-electron transfer step were obtained by , where ΔE is the change in the total ground-state energy obtained from DFT calculations, ΔZPE is the change in zero-point energies, T is 298 K and ΔS is the change in entropy. ΔGU = eU, where U is the electrode potential. and the pH = 0 was used. is neglected in the calculations.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge financial supports from the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (182300410196), National Natural Science Foundation of China (U22A20120, 52071135, 51871090, U1804135, and 51671080), Plan for Scientific Innovation Talent of Henan Province (194200510019), and Key Project of Educational Commission of Henan Province (19A150025).

Source data

Author contributions

D.Z., B.L., and S.L. conceived the study. M.L., Y.Y., B.X., and D.Z. designed the experiment and performed the initial tests. X.Y conducted the theoretical calculations. H.S., and G.I.N.W. assisted in the data analysis. D.Z., M.L., and X.Y. co-wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Maria Retuerto, Michal Bajdich and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information, where the source data of Figs. 1−5 are listed in the Source Data file (10.6084/m9.figshare.22621852)95. Extra data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Dafeng Zhang, Mengnan Li, Xue Yong.

Contributor Information

Baozhong Liu, Email: bzliu@hpu.edu.cn.

Siyu Lu, Email: sylu2013@zzu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-023-38213-1.

References

- 1.Gür TM. Review of electrical energy storage technologies, materials and systems: challenges and prospects for large-scale grid storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018;11:2696–2767. doi: 10.1039/C8EE01419A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li W, et al. Exploiting Ru−induced lattice strain in CoRu nanoalloys for robust bifunctional hydrogen production. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:3290–3298. doi: 10.1002/anie.202013985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song H, et al. Single atom ruthenium-doped CoP/CDs nanosheets via splicing of carbon-dots for robust hydrogen production. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:7234–7244. doi: 10.1002/anie.202017102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ding H, Liu H, Chu W, Wu C, Xie Y. Structural transformation of heterogeneous materials for electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction. Chem. Rev. 2021;121:13174–13212. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali A, Long F, Shen PK. Innovative strategies for overall water splitting using nanostructured transition metal electrocatalysts. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2022;5:1. doi: 10.1007/s41918-022-00136-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCrory CCL, et al. Benchmarking hydrogen evolving reaction and oxygen evolving reaction electrocatalysts for solar water splitting devices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:4347–4357. doi: 10.1021/ja510442p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCrory CCL, Jung S, Peters JC, Jaramillo TF. Benchmarking heterogeneous electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:16977–16987. doi: 10.1021/ja407115p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.An L, et al. Recent development of oxygen evolution electrocatalysts in acidic environment. Adv. Mater. 2021;33:2006328. doi: 10.1002/adma.202006328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lei Z, et al. Coordination modulation of iridium single-atom catalyst maximizing water oxidation activity. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:24. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27664-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Z, et al. Tm ldh meets birnessite: a 2d−2d hybrid catalyst with long-term stability for water oxidation at industrial operating conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:9699–9705. doi: 10.1002/anie.202016064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thangavel P, Kim G, Kim KS. Electrochemical integration of amorphous NiFe (oxy)hydroxides on surface-activated carbon fibers for high-efficiency oxygen evolution in alkaline anion exchange membrane water electrolysis. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2021;9:14043–14051. doi: 10.1039/D1TA02883A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He Z, et al. Activating lattice oxygen in NiFe-based (oxy)hydroxide for water electrolysis. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:2191. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29875-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carmo M, Fritz DL, Mergel J, Stolten D. A comprehensive review on PEM water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 2013;38:4901–4934. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2013.01.151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reier T, Nong HN, Teschner D, Schlögl R, Strasser P. Electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction in acidic environments–reaction mechanisms and catalysts. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017;7:1601275. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201601275. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kibsgaard J, Chorkendorff I. Considerations for the scaling-up of water splitting catalysts. Nat. Energy. 2019;4:430–433. doi: 10.1038/s41560-019-0407-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Z, et al. Advances in oxygen evolution electrocatalysts for proton exchange membrane water electrolyzers. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022;12:2103670. doi: 10.1002/aenm.202103670. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L, Wang P, Shao Q, Huang X. Recent progress in advanced electrocatalyst design for acidic oxygen evolution reaction. Adv. Mater. 2021;33:2004243. doi: 10.1002/adma.202004243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.She L, et al. On the durability of iridium-based electrocatalysts toward the oxygen evolution reaction under acid environment. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022;32:2108465. doi: 10.1002/adfm.202108465. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spöri C, Kwan JTH, Bonakdarpour A, Wilkinson DP, Strasser P. The stability challenges of oxygen evolving catalysts: towards a common fundamental understanding and mitigation of catalyst degradation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:5994–6021. doi: 10.1002/anie.201608601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roy C, et al. Trends in activity and dissolution on RuO2 under oxygen evolution conditions: particles versus well-defined extended surfaces. ACS Energy Lett. 2018;3:2045–2051. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.8b01178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rao RR, et al. Operando identification of site-dependent water oxidation activity on ruthenium dioxide single-crystal surfaces. Nat. Catal. 2020;3:516–525. doi: 10.1038/s41929-020-0457-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott SB, et al. The low overpotential regime of acidic water oxidation part ii: trends in metal and oxygen stability numbers. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022;15:1988–2001. doi: 10.1039/D1EE03915F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen F-Y, Wu Z-Y, Adler Z, Wang H. Stability challenges of electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction: from mechanistic understanding to reactor design. Joule. 2021;5:1704–1731. doi: 10.1016/j.joule.2021.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun H, Jung W. Recent advances in doped ruthenium oxides as high-efficiency electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2021;9:15506–15521. doi: 10.1039/D1TA03452A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harzandi AM, et al. Ruthenium core–shell engineering with nickel single atoms for selective oxygen evolution via nondestructive mechanism. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021;11:2003448. doi: 10.1002/aenm.202003448. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J, et al. Single-site Pt-doped RuO2 hollow nanospheres with interstitial C for high-performance acidic overall water splitting. Sci. Adv. 2022;8:eabl9271. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abl9271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen S, et al. Mn-doped RuO2 nanocrystals as highly active electrocatalysts for enhanced oxygen evolution in acidic media. ACS Catal. 2020;10:1152–1160. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.9b04922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su J, et al. Assembling ultrasmall copper-doped ruthenium oxide nanocrystals into hollow porous polyhedra: highly robust electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution in acidic media. Adv. Mater. 2018;30:1801351. doi: 10.1002/adma.201801351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Retuerto M, et al. Na-doped ruthenium perovskite electrocatalysts with improved oxygen evolution activity and durability in acidic media. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2041. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09791-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burnett DL, et al. (M,Ru)O2 (M = Mg, Zn, Cu, Ni, Co) rutiles and their use as oxygen evolution electrocatalysts in membrane electrode assemblies under acidic conditions. Chem. Mater. 2020;32:6150–6160. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.0c01884. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang K, et al. Highly active ruthenium sites stabilized by modulating electron-feeding for sustainable acidic oxygen-evolution electrocatalysis. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022;15:2356–2365. doi: 10.1039/D1EE03610F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou C, et al. Superdurable bifunctional oxygen electrocatalyst for high-performance zinc–air batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144:2694–2704. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c11675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hao S, et al. Dopants fixation of ruthenium for boosting acidic oxygen evolution stability and activity. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5368. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19212-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X, et al. Electronic structure modulation of RuO2 by TiO2 enriched with oxygen vacancies to boost acidic O2 evolution. ACS Catal. 2022;12:9437–9445. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.2c01944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin C, et al. In-situ reconstructed Ru atom array on α-MnO2 with enhanced performance for acidic water oxidation. Nat. Catal. 2021;4:1012–1023. doi: 10.1038/s41929-021-00703-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Man IC, et al. Universality in oxygen evolution electrocatalysis on oxide surfaces. ChemCatChem. 2011;3:1159–1165. doi: 10.1002/cctc.201000397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gayen P, Saha S, Bhattacharyya K, Ramani VK. Oxidation state and oxygen-vacancy-induced work function controls bifunctional oxygen electrocatalytic activity. ACS Catal. 2020;10:7734–7746. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.0c01541. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hubert MA, et al. Acidic oxygen evolution reaction activity–stability relationships in Ru-based pyrochlores. ACS Catal. 2020;10:12182–12196. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.0c02252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dickens CF, Nørskov JK. A theoretical investigation into the role of surface defects for oxygen evolution on RuO2. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2017;121:18516–18524. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b03481. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang L, et al. Sodium-decorated amorphous/crystalline RuO2 with rich oxygen vacancies: a robust pH-universal oxygen evolution electrocatalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:18821–18829. doi: 10.1002/anie.202106631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qin Y, et al. RuO2 electronic structure and lattice strain dual engineering for enhanced acidic oxygen evolution reaction performance. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:3784. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31468-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuznetsov DA, et al. Tailoring lattice oxygen binding in ruthenium pyrochlores to enhance oxygen evolution activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:7883–7888. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c01135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seh ZW, et al. Combining theory and experiment in electrocatalysis: insights into materials design. Science. 2017;355:146. doi: 10.1126/science.aad4998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao ZL, et al. Boosting oxygen evolution reaction using defect-rich ultra-thin ruthenium oxide nanosheets in acidic media. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020;13:5143–5151. doi: 10.1039/D0EE01960G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ge R, et al. Ultrafine defective RuO2 electrocatayst integrated on carbon cloth for robust water oxidation in acidic media. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019;9:1901313. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201901313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun H, et al. Self-supported transition-metal-based electrocatalysts for hydrogen and oxygen evolution. Adv. Mater. 2020;32:1806326. doi: 10.1002/adma.201806326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karlsson RKB, Cornell A. Selectivity between oxygen and chlorine evolution in the chlor-alkali and chlorate processes. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:2982–3028. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petrykin V, et al. Zn-doped RuO2 electrocatalyts for selective oxygen evolution: relationship between local structure and electrocatalytic behavior in chloride containing media. Chem. Mater. 2011;23:200–207. doi: 10.1021/cm1028782. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shannon RD, Prewitt CT. Effective ionic radii in oxides and fluorides. Acta Crystallogr. B. 1969;25:925–946. doi: 10.1107/S0567740869003220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chueh YL, et al. RuO2 nanowires and RuO2/TiO2 core/shell nanowires: from synthesis to mechanical, optical, electrical, and photoconductive properties. Adv. Mater. 2007;19:143–149. doi: 10.1002/adma.200601830. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kang M, et al. Single carbon fiber decorated with RuO2 nanorods as a highly electrocatalytic sensing element. Anal. Chem. 2012;84:9485–9491. doi: 10.1021/ac302334t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen ZG, Pei F, Pei YT, De Hosson JTM. A versatile route for the synthesis of single crystalline oxide nanorods: growth behavior and field emission characteristics. Cryst. Growth Des. 2010;10:2585–2590. doi: 10.1021/cg901558n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee Y, et al. Facile synthesis of single crystalline metallic RuO2 nanowires and electromigration-induced transport properties. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2011;115:4611–4615. doi: 10.1021/jp200426s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuete Saa D, et al. Synthesis of RuO2 nanowires from Ru thin films by atmospheric pressure micro-post-discharge. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016;295:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2015.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lin S, et al. Ni–Zn dual sites switch the CO2 hydrogenation selectivity via tuning of the d-band center. ACS Catal. 2022;12:3346–3356. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.1c05582. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Katea SN, Broqvist P, Kullgren J, Hemmer E, Westin G. Fast, low-cost synthesis of ZnO:Eu nanosponges and the nature of ln doping in ZnO. Inorg. Chem. 2020;59:7584–7602. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c00472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu B, Zeng HC. Fabrication of ZnO “dandelions” via a modified kirkendall process. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:16744–16746. doi: 10.1021/ja044825a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morgan DJ. Resolving ruthenium: XPS studies of common ruthenium materials. Surf. Interface Anal. 2015;47:1072–1079. doi: 10.1002/sia.5852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karlsson RKB, Cornell A, Pettersson LGM. Structural changes in RuO2 during electrochemical hydrogen evolution. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2016;120:7094–7102. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b11696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen Y, et al. A robust fuel cell operated on nearly dry methane at 500 °C enabled by synergistic thermal catalysis and electrocatalysis. Nat. Energy. 2018;3:1042–1050. doi: 10.1038/s41560-018-0262-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Doubova LM, Daolio S, De Battisti A. Examination of RuO2 single-crystal surfaces: charge storage mechanism in H2SO4 aqueous solution. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2002;532:25–33. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0728(02)00981-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arikawa T, Takasu Y, Murakami Y, Asakura K, Iwasawa Y. Characterization of the structure of RuO2−IrO2/Ti electrodes by exafs. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:3736–3741. doi: 10.1021/jp9728114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu Y, et al. Enhanced N2 electroreduction over LaCoO3 by introducing oxygen vacancies. ACS Catal. 2020;10:1077–1085. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.9b03864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li P, et al. Visible-light-driven nitrogen fixation catalyzed by Bi5O7Br nanostructures: enhanced performance by oxygen vacancies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:12430–12439. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c05097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peng S, et al. Necklace-like multishelled hollow spinel oxides with oxygen vacancies for efficient water electrolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:13644–13653. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b05134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jeon HS, et al. Operando evolution of the structure and oxidation state of size-controlled Zn nanoparticles during CO2 electroreduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:9383–9386. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b05258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ozkendir OM, Yildirimcan S, Yuzer A, Ocakoglu K. Crystal and electronic structure study of Mn doped wurtzite ZnO nanoparticles. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2016;26:347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.pnsc.2016.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lin Y, et al. Chromium-ruthenium oxide solid solution electrocatalyst for highly efficient oxygen evolution reaction in acidic media. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:162. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08144-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang Y, et al. Structurally disordered RuO2 nanosheets with rich oxygen vacancies for enhanced nitrate electroreduction to ammonia. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022;61:e202202604. doi: 10.1002/anie.202202604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wei C, et al. Recommended practices and benchmark activity for hydrogen and oxygen electrocatalysis in water splitting and fuel cells. Adv. Mater. 2019;31:1806296. doi: 10.1002/adma.201806296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhao S, Yang Y, Tang Z. Insight into structural evolution, active sites, and stability of heterogeneous electrocatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022;61:e202110186. doi: 10.1002/anie.202110186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stoerzinger KA, Qiao L, Biegalski MD, Shao-Horn Y. Orientation-dependent oxygen evolution activities of rutile IrO2 and RuO2. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014;5:1636–1641. doi: 10.1021/jz500610u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wen Y, et al. Stabilizing highly active Ru sites by suppressing lattice oxygen participation in acidic water oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:6482–6490. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c00384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang H, Wu B, Su J, Zhao K, Chen L. MOF-derived zinc-doped ruthenium oxide hollow nanorods as highly active and stable electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution in acidic media. ChemNanoMat. 2021;7:117–121. doi: 10.1002/cnma.202000526. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhou Y-N, et al. Surface evolution of Zn doped-RuO2 under different etching methods towards acidic oxygen evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2022;10:16193–16203. doi: 10.1039/D2TA03527H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Anantharaj S, Noda S, Driess M, Menezes PW. The pitfalls of using potentiodynamic polarization curves for tafel analysis in electrocatalytic water splitting. ACS Energy Lett. 2021;6:1607–1611. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.1c00608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dickens CF, Kirk C, Nørskov JK. Insights into the electrochemical oxygen evolution reaction with ab initio calculations and microkinetic modeling: Beyond the limiting potential volcano. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2019;123:18960–18977. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b03830. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Geiger S, et al. The stability number as a metric for electrocatalyst stability benchmarking. Nat. Catal. 2018;1:508–515. doi: 10.1038/s41929-018-0085-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cherevko S, et al. Oxygen and hydrogen evolution reactions on Ru, RuO2, Ir, and IrO2 thin film electrodes in acidic and alkaline electrolytes: a comparative study on activity and stability. Catal. Today. 2016;262:170–180. doi: 10.1016/j.cattod.2015.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang Z, Guo X, Montoya J, Nørskov JK. Predicting aqueous stability of solid with computed pourbaix diagram using scan functional. NPJ Comput. Mater. 2020;6:160. doi: 10.1038/s41524-020-00430-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rossmeisl J, Qu ZW, Zhu H, Kroes GJ, Nørskov JK. Electrolysis of water on oxide surfaces. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2007;607:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2006.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Scott SB, et al. The low overpotential regime of acidic water oxidation part I: the importance of O2 detection. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022;15:1977–1987. doi: 10.1039/D1EE03914H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vonrüti N, Rao R, Giordano L, Shao-Horn Y, Aschauer U. Implications of nonelectrochemical reaction steps on the oxygen evolution reaction: oxygen dimer formation on perovskite oxide and oxynitride surfaces. ACS Catal. 2022;12:1433–1442. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.1c03308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhu K, Shi F, Zhu X, Yang W. The roles of oxygen vacancies in electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction. Nano Energy. 2020;73:104761. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2020.104761. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jin H, et al. Safeguarding the RuO2 phase against lattice oxygen oxidation during acidic water electrooxidation. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022;15:1119–1130. doi: 10.1039/D1EE02636D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rao RR, et al. Towards identifying the active sites on RuO2(110) in catalyzing oxygen evolution. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017;10:2626–2637. doi: 10.1039/C7EE02307C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stoerzinger KA, et al. Orientation-dependent oxygen evolution on RuO2 without lattice exchange. ACS Energy Lett. 2017;2:876–881. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.7b00135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Guerrini E, Consonni V, Trasatti S. Surface and electrocatalytic properties of well-defined and vicinal RuO2 single crystal faces. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2005;9:320–329. doi: 10.1007/s10008-004-0602-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]