Key Words: adeno-associated virus, astrocytes, blood-brain barrier, epilepsy, epilepsy-associated depression-like behavior, neuroinflammation, pentylenetetrazol, pilocarpine, tight junction

Abstract

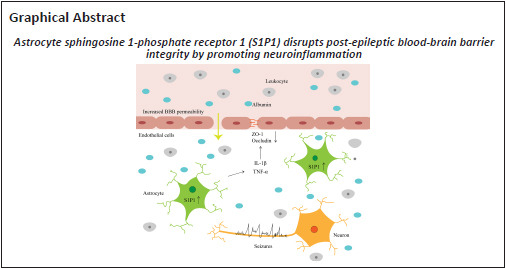

Destruction of the blood-brain barrier is a critical component of epilepsy pathology. Several studies have demonstrated that sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 contributes to the modulation of vascular integrity. However, its effect on blood-brain barrier permeability in epileptic mice remains unclear. In this study, we prepared pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus models and pentylenetetrazol-induced epilepsy models in C57BL/6 mice. S1P1 expression was increased in the hippocampus after status epilepticus, whereas tight junction protein expression was decreased in epileptic mice compared with controls. Intraperitoneal injection of SEW2871, a specific agonist of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1, decreased the level of tight junction protein in the hippocampus of epileptic mice, increased blood-brain barrier leakage, and aggravated the severity of seizures compared with the control. W146, a specific antagonist of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1, increased the level of tight junction protein, attenuated blood-brain barrier disruption, and reduced seizure severity compared with the control. Furthermore, sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 promoted the generation of interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α and caused astrocytosis. Disruption of tight junction protein and blood-brain barrier integrity by sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 was reversed by minocycline, a neuroinflammation inhibitor. Behavioral tests revealed that sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 exacerbated epilepsy-associated depression-like behaviors. Additionally, specific knockdown of astrocytic S1P1 inhibited neuroinflammatory responses and attenuated blood-brain barrier leakage, seizure severity, and epilepsy-associated depression-like behaviors. Taken together, our results suggest that astrocytic sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 exacerbates blood-brain barrier disruption in the epileptic brain by promoting neuroinflammation.

Introduction

Epilepsy is a severe nervous system disease that has a prevalence of 1–3% and affects over 50 million people globally (Pitkänen et al., 2016; Hanael et al., 2019). Epilepsy’s primary etiologies include traumatic brain injury (TBI), cerebrovascular disease, and central nervous system infections (Mac et al., 2007). Epilepsy features repeated spontaneous seizures caused by abnormal overactive or synchronized neuronal activity, and it is usually accompanied by cognitive impairment and psychological co-morbidities (Bauer et al., 2021). Despite the existing clinical therapies for epilepsy, including over 20 antiepileptic drugs and surgical procedures, treatment outcomes are generally unsatisfactory (Pitkänen et al., 2016; Achar and Ghosh, 2021). There is an increasing need to further clarify the pathological mechanisms of epilepsy. Studies have shown that various pathophysiological processes occur after the onset of epilepsy, such as oxidative stress, destruction of blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity, cytotoxicity, and glial cell proliferation. Among them, an increasing amount of evidence has shown that BBB disruption has vital contributions to the epilepsy progression (Gorter et al., 2019; Wood, 2020).

The BBB is a complicated and dynamic barrier comprising endothelial cells that are connected mainly by tight junction (TJ) proteins. After a seizure, a variety of mechanisms work together to modify the BBB characteristics. For example, seizure-induced reactive astrocytosis, glial scar formation, and cytokine upregulation can exacerbate BBB disruption (Uprety et al., 2021). Seizure-induced release of brain glutamate also increases matrix metalloproteinase activity and expression, which consequently affects BBB integrity by damaging the extracellular matrix and TJ proteins (Rempe et al., 2018). BBB destruction results in some proteins and immune cells leaking into the cerebral parenchyma, glial cell activation, inflammatory responses, ionic disturbances, excitatory synaptogenesis, and pathological plasticity. These events increase neuroexcitability and ultimately promote seizure onset (Milikovsky et al., 2019). Thus, BBB destruction is both the result and the cause of epilepsy (Löscher and Friedman, 2020). Identifying a novel strategy to reduce BBB damage may, therefore, help to alleviate neuronal injuries in the epileptic brain.

Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) is a vital molecule for lipid signaling and has various regulatory effects, such as proliferation, migration, apoptosis, and inflammation, through binding to the five S1P receptors (S1P1–5) on cell membranes (McGinley and Cohen, 2021). Among them, S1P1, S1P2, and S1P3 are widely distributed in multiple systemic organs and show a cell-specific distribution pattern in the central nervous system (Roggeri et al., 2020). An increasing amount of evidence suggests that these receptors are linked to the modulation of BBB integrity. Yanagida et al. (2017) used endothelial-specific S1P1 knockout mice to demonstrate that S1P1 maintains BBB integrity via modulating TJ protein positioning. Another report indicated that renal Janus kinase 2/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling promoted BBB injury in septic rats by downregulating S1P1 expression (Chen et al., 2020). In a lipopolysaccharide-mediated model of systemic inflammation in mice, S1P2 was shown to disrupt BBB integrity by promoting neutrophil extravasation and enhancing microglia inflammation (Xiang et al., 2021). Another study indicated that S1P3 can disrupt BBB integrity by promoting C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 expression and decreasing zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) expression in rats after intracerebral hemorrhage (Xu et al., 2021). However, it remains unclear whether S1P receptors are involved in regulating BBB dysregulation after seizures, especially in the acute phase within 72 hours after seizures (Shehata et al., 2022).

To investigate the role of S1P receptors in BBB dysfunction after seizures, we first investigated S1P receptor expression using a pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus (SE) mouse model. We then explored the effects of S1P1 on BBB integrity, neuroinflammation, seizure severity, and epilepsy-associated depression-like behavior by pharmacologically activating or inhibiting S1P1 and through astrocyte-specific knockdown of S1P1 in the brain.

Methods

Animals

To avoid the effect of changes in estrogen and progesterone levels on seizures (Janisset et al., 2022), male C57BL/6J specific pathogen-free mice (18.0–22.0 g, 6 weeks old) were obtained from GemPharmatech Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China, license No. SCXK (Su) 2018-0008). The mice were placed in separate cages (four mice per cage) and kept at a regulated temperature (22 ± 2°C) and humidity (50 ± 5%) and exposed to a 12-hour daylight/dark cycle. They had free access to food and water. All animal experimental programs were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the Medical School of Southeast University on May 15, 2021 (No. 20210515006). All experiments were designed and reported in accordance with the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines (Percie du Sert et al., 2020).

Establishment of pilocarpine-induced SE and pentylenetetrazol-kindling models

SE was evoked via intraperitoneal injection of pilocarpine as mentioned earlier (Zhu et al., 2018). First, mice underwent intraperitoneal injection of methyl-scopolamine (1 mg/kg, TCI, Shanghai, China) to minimize peripheral cholinergic influences. After half an hour, a single dose of 290 mg/kg pilocarpine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA; Cat# P6503) was injected intraperitoneally to induce SE. Control mice were administered 0.9% normal saline (0.1 mL/10 g) instead of pilocarpine. The seizure severity was evaluated in accordance with the Racine scale (Racine, 1972), as follows: Stage 0, normal behavior; Stage 1, whisker shaking, blinking, and facial muscle spasms; Stage 2, facial muscle spasms and rhythmic head nodding movements; Stage 3, unilateral or bilateral forelimb clonus; Stage 4, bilateral anterior limb clonus with hind limb standing; and Stage 5, generalized tonic-clonic seizures with falls. Stage 5 seizures lasting at least 5 minutes were defined as SE (Zhu et al., 2019). Mice were administered diazepam (7.5 mg/kg intraperitoneal injection, Jinyao, Tianjin, China) 2 hours after SE onset, which was repeated as needed to stop behavioral seizures. To induce the kindling epilepsy model, mice were administered pentylenetetrazol (PTZ; 35 mg/kg, Aladdin Reagents Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) intraperitoneally every other day from days 1 to 21, which included 11 injections. The control mice were administered 0.9% normal saline. Seizures were observed within 30 minutes after each PTZ administration (Zhu et al., 2017), and seizure intensity was assessed as described above.

Drug administration

We assigned the mice randomly to the experiments and groups that are described below (Additional Figure 1 (3.6MB, tif) ).

Experiment 1: For investigating the effect of S1P1 on the disruption of BBB, changes in tight junction proteins and changes in inflammatory factors after epilepsy, mice were randomly divided into control, SE, SE + Vehicle (injected with dimethyl sulfoxide), SE + SEW2871 (injected with the S1P1 specific agonist SEW2871), and SE + W146 groups (injected with the S1P1 specific antagonist W146) (n = 4 or 8 per group). Vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide, 0.4 mL/kg; Beyotime, Shanghai, China), SEW2871 (dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide; 10 mg/kg; Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), or W146 (dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide; 1 mg/kg; Cayman Chemicals) was intraperitoneally injected immediately and once a day after the termination of SE (Bajwa et al., 2010).

Experiment 2: For investigating the effect of S1P1 on the severity of seizures, the kindling mice model were administered vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide, 0.4 mL/kg), SEW2871 (10 mg/kg), or W146 (1 mg/kg) intraperitoneally 30 minutes before each PTZ treatment (n = 8 per group), every other day, which included 11 injections.

Experiment 3: For investigating whether S1P1 can affect BBB destruction in epileptic mice by regulating inflammation, mice were randomly divided into SE + Vehicle, SE + SEW2871, SE + minocycline (injected with minocycline), and SE + SEW2871 + minocycline groups (n = 4 per group). Vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide, 0.4 mL/kg), SEW2871 (10 mg/kg), or minocycline (50 mg/kg, ApexBio, Houston, TX, USA) (Lu et al., 2021) was intraperitoneally injected immediately and once a day after termination of SE.

Stereotaxic virus injection

The adeno-associated virus (rAAV-GFaABC1D-mCherry-5́miR-30a-shRNA(S1P1)-3́miR-30a-WPREs) carrying the glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) promoter was used to conditionally knockdown S1P1 in mouse astrocytes. The adeno-associated virus (AAV) structure used in this study (either AAV-GFAP-shRNA-S1P1 or AAV-GFAP-shRNA-Scr) was designed and produced by Shumi Brain Science and Technology Company (Wuhan, China). To perform the microinjection, we first anesthetized the mice using an intraperitoneal injection of 1% pentobarbital sodium (35 mg/kg, Sigma-Aldrich; Cat# P-009) and placed them on a stereotaxic instrument (RWD, Shenzhen, China). The viruses were administered into the hippocampus (0.5 μL per side; antero-posterior, –2.3 mm; medial-lateral, ±1.8 mm; dorsal-ventral, –2.0 mm) (Guo et al., 2021) at a speed of 0.1 µL/min using a microsyringe (Hamilton, Bonaduz, Switzerland). Following the infusion, the needle was held in position for 5 minutes.

Western blot assay

To explore the changes in S1P receptors in the epileptic mouse brain and the role of S1P receptors on marker proteins of BBB disruption after epilepsy, the hippocampus tissues of mice at different time points (6, 12, 24, and 48 hours) after SE were extracted from the mice and lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay reagent and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Beyotime). We quantified proteins extracted from tissues using the BCA protein analysis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and denatured at 98°C for 5 minutes. Next, we isolated the protein samples using SDS-PAGE, which was followed by transfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Five percent skim milk in Tris-buffered saline Tween was applied to block membrane for 1 hour at 25 ± 2°C, followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with rabbit anti-S1P1 (1:2000, Proteintech, Wuhan, China, Cat# 55133-1-AP, RRID: AB_10793721), rabbit anti-ZO-1 (1:500, Proteintech, Cat# 21773-1-AP, RRID: AB_10733242), rabbit anti-occludin (1:1000, Proteintech, Cat# 27260-1-AP, RRID: AB_2880820), rabbit anti-S1P2 (1:1000, Proteintech, Cat# 21180-1-AP, RRID: AB_10694573), rabbit anti-S1P3 (1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK, Cat# ab108370, RRID: AB_10860371), and rabbit anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 1:5000, Proteintech, Cat# 10494-1-AP, RRID: AB_2263076) antibodies. After washing, we incubated the goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:3000, Beyotime, Cat# A0208, RRID: AB_2892644) with the membrane for 2 hours at 25 ± 2°C. Subsequently, the membranes were exposed using an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Biological Sciences, Shanghai, China). The gray value of each strip was assayed by ImageJ (V1.8.0; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) (Schneider et al., 2012), and the data were presented as the ratio to GAPDH.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

To examine the amounts of inflammatory cytokines, a mouse was sacrificed 48 hours after SE, and the hippocampal homogenates were obtained as described above. Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) levels were analyzed using specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reagents in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (Elabscience, Wuhan, China).

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay

To investigate whether S1P1 could regulate ZO-1 and occludin expression at the transcriptional level, we obtained total RNA from hippocampal tissue 48 hours after SE with RNAiso reagent (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA concentration and purity were analyzed with a nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA was then reverse transcribed by HiScript® III RT SuperMix for qPCR (Vazyme) and quantified using ChamQ™ SYBR® qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme) based on protocols. The reaction program was 95°C for 30 seconds, and then 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 seconds and 60°C for 30 seconds. The relative mRNA expression levels were normalized to those of GAPDH. The following primers obtained from GENEray (Generay, Shanghai, China) were used: S1P1 forward: 5′-ATG GTG TCC ACT AGC ATC CC-3′, reverse: 5′-CGA TGT TCA ACT TGC CTG TGT AG-3′; ZO-1 forward: 5′-GCC GCT AAG AGC ACA GCA A-3′, reverse: 5′-TCC CCA CTC TGA AAA TGA GGA-3′; occludin forward: 5′-TGA AAG TCC ACC TCC TTA CAG A-3′, reverse: 5′-CCG GAT AAA AAG AGT ACG CTG G-3′; and GAPDH forward: 5′-CGA CTT CAA CAG CAA CTC CCA CTC TTC C-3′, reverse: 5′-TCC TGG GTG GTC CAG GGT TTC TTA CTC CTT-3′.

Immunofluorescence

Mice were anesthetized 48 hours after SE by an intraperitoneal injection of 1% pentobarbital sodium (35 mg/kg) and then perfused with normal saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Brain tissue was then placed in 4% paraformaldehyde for overnight fixation as well as in 30% sucrose in phosphate buffer saline for 3 days of cryoprotection. Next, a cryostat (Leica CM1950, Wetzlar, Germany) was used to slice the brain into 30-μm thick coronal slices containing the hippocampus. After placing these brain slices into 0.3% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes and blocking in 10% goat serum (Beyotime) for 1 hour, the slices were incubated with mouse anti-GFAP (a marker for astrocyte) antibody (1:200, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA, Cat# 3670, RRID: AB_561049) at 4°C overnight. Subsequently, these brain slices were cleaned with phosphate buffer saline and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse antibody (1:500, Beyotime, Cat# A0428, RRID: AB_2893435) for 1 hour at 25 ± 2°C. After washing, we attached slices of the mouse brain to a glass slide and stained the nuclei using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Abcam). Finally, the brain slice was photographed using a fluorescence microscope (FV-3000, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Another group of mouse brain samples was also fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 4-µm thick coronal slices containing the hippocampus. After antigen retrieval, we incubated these brain slices with rabbit anti-S1P1 (1:200, Proteintech, Cat# 55133-1-AP, RRID: AB_10793721) and mouse anti-GFAP (1:200, Cell Signaling Technology, Cat# 3670, RRID: AB_561049) overnight at 4°C and then with Alexa Fluor 555 donkey anti-rabbit antibody (1:500, Beyotime, Cat# A0453, RRID: AB_2890132) and Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse antibody (1:500, Beyotime, Cat# A0428, RRID: AB_2893435) for 1 hour at 37°C. The protocol for double staining with two primary antibodies of the same species was performed as previously described (Tang et al., 2021). Briefly, a coronal hippocampal section was incubated with rabbit anti-Iba-1 (a marker for microglia; 1:400; Wako, Osaka, Japan) overnight at 4°C, and then with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:500, Beyotime, Cat# A0423, RRID: AB_2891323) for 1 hour at 37°C. After washing, slices were then incubated with antibody rabbit anti-S1P1 (1:200; Proteintech), followed by the corresponding secondary antibody. Finally, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole was used to stain the nuclei. GFAP, S1P1, and Iba-1 immunostaining were quantified using ImageJ. Cell colocalization analysis was performed on a series of sections, and four fields were captured randomly from each section. Total GFAP+ cells and GFAP+ cells co-localized with S1P1 were counted separately by a blinded observer, and the averages were obtained.

BBB permeability assay

To detect the BBB permeability 48 hours after SE, mice were first administered 2% Evans blue (EB, 4 mL/kg; Sigma-Aldrich) through the tail vein 4 hours before sacrifice. After perfusing the mice with normal saline, the hippocampal tissue was then isolated, weighed, and homogenized in cold phosphate buffered saline. After adding 50% trichloroacetic acid (Aladdin Reagents Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) to precipitate the protein, we performed centrifugation at 12,000 × g, 4°C, for 30 minutes to obtain the supernatant. The dye concentration in the supernatant was determined using Thermo Fisher Scientific Multiskan GO spectrophotometry at 620 nm. To further compare EB leakage between groups, we analyzed the coronal brain slices under a fluorescence microscope.

Sucrose preference test

This behavioral test used rodents’ innate preference for sweets to detect anhedonia (Pucilowski et al., 1993). After 2 weeks of SE, the mice were first deprived of water for 24 hours before the experiment. During the test, mice had access to two bottles, one filled with water and the other with 1% sucrose. The total test duration was 1 hour, and the bottle position was exchanged after 30 minutes. The intake of regular water and sucrose was then calculated (Zhu et al., 2017). The mice recovered for 3 days before being subjected to other tests.

Forced swim test

We evaluated depression-like behavior in mice using a forced swim test after 2 weeks of SE (Zhu et al., 2017). Briefly, a 2-L glass beaker was filled with 1900 mL of water (22–25°C). We ensured that the beaker was deep enough that the mouse’s tail did not touch the bottom. Mice were left in the beaker for 6 minutes and their actions were recorded. Mice were judged to be immobile when they did not perform any activity other than that required to keep their head above the water surface.

Statistical analysis

We conducted all statistical analyses using GraphPad Prism 8.0.1 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA, www.graphpad.com). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons between two groups were assessed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Comparisons involving multiple groups were conducted using a one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test. A difference of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

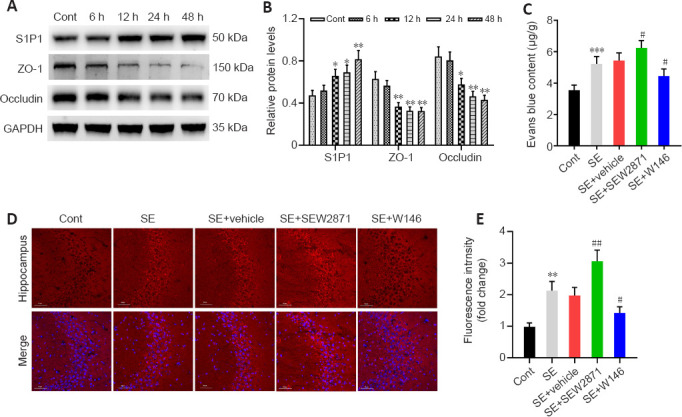

S1P1 and TJ protein expression in hippocampal tissue after SE

First, to explore changes in the S1P receptor family during the acute phase of SE, we detected S1P1 protein levels at various time points. Compared with controls, S1P1 expression in the hippocampus began to increase 12 hours (P < 0.05) after SE and peaked at 48 hours (P < 0.01, Figure 1A and B). However, S1P2 and S1P3 protein levels did not change after SE (Additional Figure 2A (1.3MB, tif) and B (1.3MB, tif) ). We also examined TJ protein levels. ZO-1 and occludin levels gradually decreased, reaching the lowest levels at 48 hours after SE (both P < 0.01, Figure 1A and B). Thus, a time point of 48 hours after SE was used in the subsequent experiments.

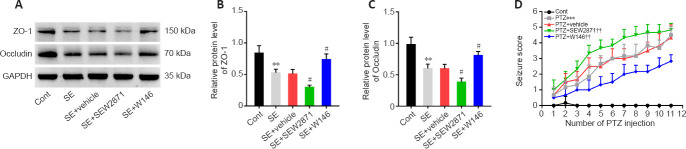

Figure 1.

S1P1 expression after SE and its effect on BBB integrity.

(A, B) Western blot analysis and quantification of S1P1, ZO-1, and occludin levels in the hippocampus at different time points after SE. The relative expression was normalized to that of GAPDH. (C–E) Photometric analysis (C) and fluorescence analysis (D, E) of hippocampal tissue showing EB leakage was higher in SE + SEW2871 but lower in SE + W146 mice. Scale bars: 50 μm. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 4 mice per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.01, vs. control group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, vs. SE + vehicle group (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test). BBB: Blood-brain barrier; EB: Evans blue; GAPDH: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; S1P1: sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1; SE: status epilepticus; ZO-1: zonula occludens-1.

Effect of S1P1 on BBB integrity after SE and seizure severity

As shown in Figure 1C, EB permeability in the SE group was increased compared with controls (P < 0.001). Compared with that in mice in the SE + Vehicle group, EB permeability in SE + SEW2871 group was higher (P < 0.05) while that in SE + W146 mice was lower (P < 0.05). Similarly, the results showed higher EB leakage in the SE + SEW2871 group (P < 0.01) but lower leakage in the SE + W146 (P < 0.05) group compared with that in the SE + Vehicle group (Figure 1D and E). The influence of S1P1 on TJ protein after SE was then explored using western blot. Compared with that in the SE + Vehicle group, levels of both ZO-1 and occludin in the SE + SEW2871 group were lower (both P < 0.05), while those of both in the SE + W146 group were higher (both P < 0.05; Figure 2A–C). Moreover, SEW2871 pretreatment increased seizure severity, whereas W146 pretreatment reduced seizure severity (both P < 0.01; Figure 2D) compared with that of the PTZ + vehicle group in PTZ-kindling epilepsy model mice.

Figure 2.

Effect of S1P1 on tight junction protein at 48 hours after SE and seizure severity.

(A–C) Western blot analysis (A) and quantification (B, C) showed that S1P1 had a disruptive effect on ZO-1 and occludin (n = 4 mice per group) expression at 48 hours after SE. The relative expression was normalized using GAPDH. (D) Time-course effect of S1P1 on the Racine scale score in PTZ-kindled mice (n = 8 mice per group). Data are presented as the mean ± SD. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, vs. control group; #P < 0.05, vs. SE + vehicle group; ††P < 0.01, vs. PTZ + vehicle group (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test). GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; PTZ: pentylenetetrazol; S1P1: sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1; SE: status epilepticus; ZO-1: zonula occludens-1.

S1P1 disrupts BBB integrity after SE by regulating neuroinflammation

To examine whether S1P1 affects BBB integrity by regulating neuroinflammation, we first examined the effect of S1P1 on neuroinflammatory cytokines. IL-1β and TNF-α levels were markedly higher in the hippocampus after SE compared with those of controls (both P < 0.001). Furthermore, IL-1β and TNF-α levels appeared to be higher in the SE + SEW2871 group (P < 0.001 for IL-1β and P < 0.01 for TNF-α, respectively) and lower in the SE + W146 group compared with those in the SE + Vehicle group (both P < 0.01; Figure 3A). We then tested whether minocycline has an anti-inflammatory role by measuring neuroinflammatory cytokine levels in this mouse model. IL-1β (P < 0.001) and TNF-α (P < 0.01) levels decreased in the SE + minocycline group compared with those in the SE + Vehicle group. Compared with the SE + SEW2871 + minocycline group, IL-1β and TNF-α levels were increased in the SE + SEW2871 group (P < 0.01 for IL-1β and P < 0.05 for TNF-α, respectively) and decreased at SE + minocycline group (both P < 0.001; Additional Figure 3 (1MB, tif) ).

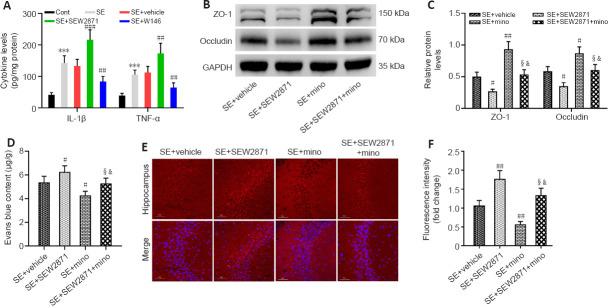

Figure 3.

Destruction of BBB integrity by S1P1 depends on hippocampal neuroinflammation at 48 hours after SE.

(A) ELISA results showed that S1P1 increased IL-1β and TNF-α levels after SE in mice. (B, C) Western blot analysis (B) and quantification (C) results showed that minocycline attenuated the disruptive effect of S1P1 on ZO-1 and occludin expression. The relative expression was normalized using GAPDH. (D–F) Photometric analysis (D) and fluorescence analysis (E, F) of EB dye content showed that EB leakage was higher in SE + SEW2871 but lower in SE + SEW2871 + minocycline (SE + SEW2871 + mino) mice. Scale bars: 50 μm. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 4 mice per group). ***P < 0.001, vs. control group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, vs. SE + vehicle group; ¦P < 0.05, vs. SE + SEW2871 group; &P < 0.05, vs. SE + minocycline (SE + mino) group (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test). BBB: Blood-brain barrier; cont: control; EB: Evans blue; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; GAPDH: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; IL-1β: interleukin-1β; PTZ: pentylenetetrazol; S1P1: sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1; SE: status epilepticus; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α; ZO-1: zonula occludens-1.

Subsequently, we found elevated ZO-1 and occludin levels in the hippocampus of SE + minocycline group compared with those in the SE + Vehicle group (P < 0.01 for ZO-1, P < 0.05 for occludin). ZO-1 and occludin levels were increased in the SE + SEW2871 + minocycline group compared with those in the SE + SEW2871 group (both P < 0.05), but they were decreased in the SE + SEW2871 + minocycline group compared with those in the SE + minocycline group (both P < 0.05; Figure 3B and C). Consistent with these findings, EB leakage was lower in the SE + minocycline group compared with that in the SE + Vehicle group. Furthermore, EB leakage in the SE + SEW2871 + minocycline group was lower than that in the SE + SEW2871 group but higher than that in the SE + minocycline group (all P < 0.05; Figure 3D–F).

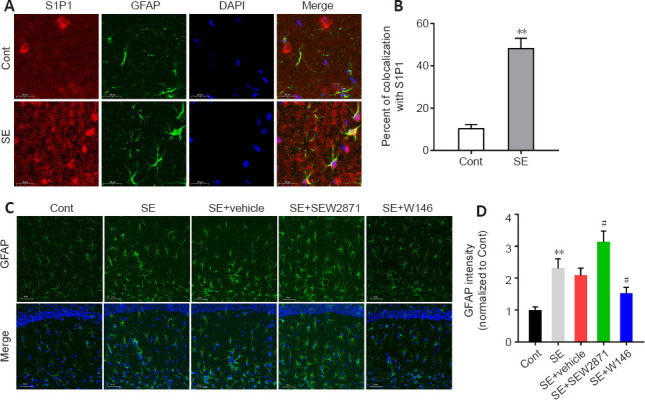

S1P1 is highly expressed in hippocampal astrocytes after SE and promotes astrocyte activation

To further investigate how S1P1 regulates neuroinflammation, we performed an immunofluorescence colocalization analysis of S1P1 with astrocytes and microglia. The results indicated that co-localization of S1P1 with astrocytes was markedly higher after SE compared with that of controls (P < 0.01; Figure 4A and B), while no obvious co-localization was observed in microglia (Additional Figure 4 (1.4MB, tif) ). Compared with that in the SE + Vehicle group, the GFAP fluorescence intensity was higher in the SE + SEW2871 group and lower in the SE + W146 group (both P < 0.05; Figure 4C and D).

Figure 4.

S1P1 expression is increased in hippocampal astrocytes, which promote astrocyte activation after SE.

(A) Colocalization of S1P1 (red, Alexa Flour 555)- and GFAP (green, Alexa Flour 488)-positive cells in the mouse hippocampus. S1P1 colocalization with astrocytes was higher after SE compared with that of controls. (B) Quantification of the S1P1 colocalization with astrocytes. (C) Representative fluorescence images of GFAP (green, Alexa Flour 488) in the mouse hippocampus. The fluorescence intensity of GFAP was higher in the SE + SEW2871 group and lower in the SE + W146 group compared with that of the control. Scale bars: 20 μm (A), 50 μm (C). (D) Quantification of GFAP staining intensities in the mouse hippocampus. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 4 mice per group). **P < 0.01, vs. Control group; #P < 0.05, vs. SE + vehicle group (two-tailed Student’s t-test for B, one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for D). Cont: Control; DAPI: 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein; S1P1: sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1; SE: status epilepticus.

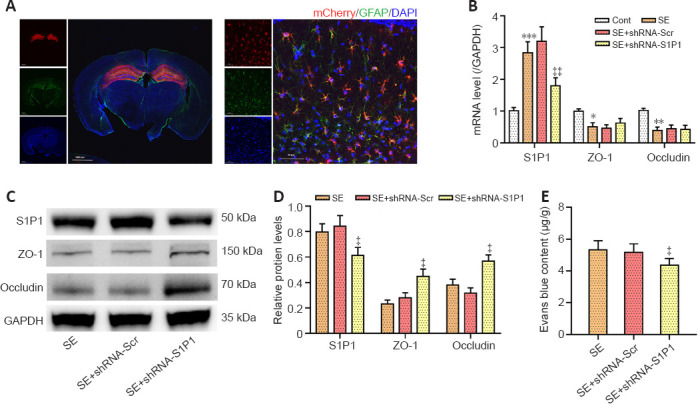

Astrocyte-specific knockdown of S1P1 improves BBB disruption after SE

Immunofluorescence staining results showed marked viral fluorescence expressed in hippocampus and colocalized to astrocytes (Figure 5A). Confirming S1P1 knockdown, both S1P1 mRNA and protein levels were markedly decreased in the SE + shRNA-S1P1 group compared with that in the SE + shRNA-Scr group (both P < 0.05; Figure 5B–D). ZO-1 and occludin mRNA levels were not different between the two groups, although ZO-1 and occludin protein levels appeared to be elevated in the SE + shRNA-S1P1 group compared with that in the SE + shRNA-Scr group (both P < 0.05; Figure 5B–D). Additionally, EB permeability decreased in the SE + shRNA-S1P1 group compared with that in the SE + shRNA-Scr group (P < 0.05; Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

Effects of astrocyte-specific knockdown of S1P1 on tight junction proteins and BBB integrity in the hippocampus.

(A) Colocalization of mCherry-AAV with GFAP 4 weeks after microinjection, which showed adeno-associated viruses can target hippocampal astrocytes. Red represents rAAV-GFaABC1D-mCherry-shRNA (Scramble/S1P1), mCherry; green, GFAP, Alexa Flour 488; blue, DAPI. Scale bars: 1400 μm (left) or 50 μm (right). (B) The RT-PCR assay showed that injection of AAV with astrocyte-specific knockdown of S1P1 reduced S1P1 mRNA levels but had no effect on ZO-1 and occludin mRNA expression after SE. (C, D) Western blot analysis (C) and quantification (D) results showed that astrocyte-specific knockdown of S1P1 increased ZO-1 and occludin expression after SE. The relative expression was normalized to that of GAPDH. (E) Photometric analysis of EB dye content showed that astrocyte-specific knockdown of S1P1 reduced BBB leakage after SE. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 4 mice per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, vs. control group; ‡P < 0.05, ‡‡P < 0.01, vs. SE + shRNA-Scr group (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test). AAV: Adeno-associated viruses; BBB: blood-brain barrier; DAPI: 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; EB: Evans blue; GAPDH: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein; RT-PCR: reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; S1P1: sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1; SE: status epilepticus; ZO-1: zonula occludens-1.

Astrocyte-specific knockdown of S1P1 suppresses neuroinflammation and reduces seizure severity

The GFAP fluorescence intensity was decreased in the SE + shRNA-S1P1 group compared with that in the SE + shRNA-Scr group (P < 0.01; Figure 6A and B). IL-1β and TNF-α levels were also lower in the SE + shRNA-S1P1 group compared with that in the SE + shRNA-Scr group (P < 0.01 for IL-1β and P < 0.001 for TNF-α, respectively; Figure 6C and D). Additionally, in the PTZ-kindling model, seizure severity was decreased in the PTZ + shRNA-S1P1 group compared with that in the PTZ + shRNA-Scr group (P < 0.01; Figure 6E).

Figure 6.

Effects of astrocyte-specific knockdown of S1P1 on inflammation and seizure severity.

(A) Representative fluorescence images of GFAP (green, Alexa Flour 488) in the mouse hippocampus. The GFAP fluorescence intensity in the SE + shRNA-S1P1 group was lower than that in the SE + shRNA-Scr group. Scale bars: 50 μm. (B) Quantification of GFAP staining intensities in the mouse hippocampus (n = 4 mice per group). The relative expression was normalized to that of the SE group. (C, D) The ELISA results showed that astrocyte-specific knockdown of S1P1 decreased IL-1β and TNF-α levels after SE in mice (n = 4 mice per group). (E) PTZ-kindling showed that astrocyte-specific knockdown of S1P1 reduced seizure severity (n = 8 mice per group). Data are presented as the mean ± SD. ‡‡P < 0.01, ‡‡‡P < 0.001, vs. SE + shRNA-Scr group; ^^P < 0.01, vs. PTZ + shRNA-Scr group (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test). DAPI: 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein; IL-1β: interleukin-1β; PTZ: pentylenetetrazol; S1P1: sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1; SE: status epilepticus; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α.

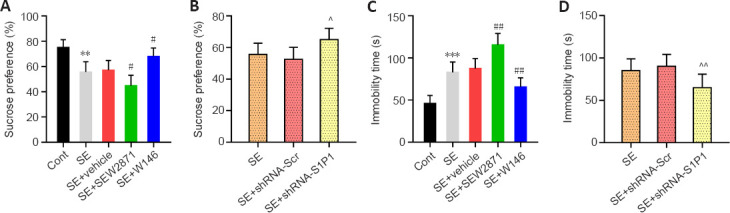

S1P1 effects on epilepsy-associated depression-like behaviors

Compared with that in the SE + Vehicle group, the percentage of sucrose water consumption was lower in SE + SEW2871 group (P < 0.05) but higher in the SE + W146 group (P < 0.05; Figure 7A). Astrocyte-specific knockdown of S1P1 reduced depression-like behaviors, as demonstrated by higher sucrose water consumption in the SE + shRNA-S1P1 group compared with that in the SE + shRNA-Scr group (P < 0.01; Figure 7B). In the forced swimming test, compared with that in the SE + Vehicle group, the immobility time was increased in the SE + SEW2871 group and decreased in the SE + W146 group (both P < 0.01; Figure 7C). Furthermore, the immobility time was reduced in the SE + shRNA-S1P1 group compared with that in the SE + shRNA-Scr group (P < 0.01, Figure 7D).

Figure 7.

Effect of S1P1 on epilepsy-associated depression-like behaviors in mice.

(A, B) Percentage of sucrose water consumption during the sucrose preference test. (C, D) Immobility time during the forced swim test. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 8 mice per group). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, vs. control group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, vs. SE + vehicle group; ^P < 0.05, ^^P < 0.01, vs. PTZ + shRNA-Scr group (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test). Cont: Control; PTZ: pentylenetetrazol; SE: status epilepticus; S1P1: sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1.

Discussion

Although previous studies indicate that BBB disruption plays key roles in epilepsy progression, potential molecular pathologies are not entirely elucidated. Here, we performed various tests to elucidate the role of S1P1 in epilepsy. We first found that S1P1 expression levels were elevated in the hippocampal tissue of SE mice. Subsequently, we confirmed that S1P1 activation promoted the release of neuroinflammatory cytokines and exacerbated BBB damage, whereas S1P1 inhibition reduced neuroinflammatory cytokines and mitigated BBB damage in the epileptic brain. Our data revealed that S1P1 expression was increased in activated astrocytes after SE and that astrocyte-specific knockdown of S1P1 reduced neuroinflammatory cytokine release and alleviated BBB leakage. Additionally, we demonstrated that seizure severity and epilepsy-associated depression-like behaviors were improved in mice after inhibition or astrocyte-specific S1P1 knockdown. These findings indicate that S1P1 is a key injury response gene closely associated with BBB integrity in the epileptic brain.

TJ proteins are important in sustaining BBB integrity, and changes in TJ proteins are often used as an indicator of BBB integrity (Huang et al., 2021; Cheng et al., 2022). Our data indicated a decrease in TJ protein levels and an increase in BBB leakage after SE in mice. Similar to our findings, a study using a pilocarpine-induced seizure model in rats showed dynamic, time-dependent BBB disruption in the acute phase (Mendes et al., 2019). This finding highlights the need to identify therapeutic targets to reverse BBB disruption in the acute phase of SE. S1P1 as a transmembrane G protein-coupled receptor that participates in a wide range of biological processes (Weichand et al., 2017). Here, we demonstrated that S1P1 levels were increased in hippocampal tissue after SE in mice, while pharmacological S1P1 activation decreased ZO-1 and occludin and S1P1 inhibition increased these TJ protein levels. Similar to our data, another study indicated that S1P1 knockdown attenuated BBB destruction in the transient middle cerebral artery occlusion mouse model by attenuating TJ protein degradation and ICAM-1 upregulation in the brain (Gaire et al., 2018). Conversely, another report demonstrated that selective S1P1 modulators attenuated BBB disruption after TBI in mice by decreasing endothelial cell apoptosis (Cheng et al., 2021). These studies revealed that the mechanisms of S1P1 involvement in modulating BBB destruction were complex and varied in different disease models.

The ability of neuroinflammation to disrupt TJ proteins is an important mechanism resulting in impaired BBB integrity (Shi et al., 2019). A previous study indicated that S1P1 signaling plays key roles in inflammation (Aoki et al., 2016), and thus, we proposed the hypothesis that S1P1 might affect BBB integrity by modulating neuroinflammation. The results reported here show that pharmacological activation increased IL-1β and TNF-α levels, whereas inhibiting S1P1 decreased these inflammatory cytokines. Subsequently, blocking neuroinflammation reversed the damaging effects S1P1 activation on TJ protein and BBB integrity, suggesting that S1P1 is a pro-inflammatory mediator in the acute phase of SE. Consistent with our findings, Doyle et al. (2019) showed that the S1P1 agonist SEW2871 induced mechanical dystonia in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord through increasing IL-1β and NOD-like receptor protein 3 levels. Moreover, S1P1 was shown to promote TNF-α and IL-1β generation in human lymphatic endothelial cells by mediating nuclear factor-kappa B signaling, thereby modulating lymphangiogenesis (Zheng et al., 2019). Another report revealed that S1P1 activation significantly reduced urinary TNF-α levels in rats with diabetic nephropathy and TNF-α mRNA levels in immortalized podocytes grown in a high glucose medium (Awad et al., 2011).

Following central nervous system stimulation, neuroinflammation is mainly mediated by glial cells (Xue and Yong, 2020; Li et al., 2022). Our findings indicated that S1P1 expression was elevated on hippocampal astrocytes in SE mice. Astrocyte-specific S1P1 knockdown decreased neuroinflammatory cytokine levels and astrocyte activation after SE. Similarly, Van Doorn et al. (2010) found that S1P1 was markedly increased on reactive astrocytes in brain lesions from people with multiple sclerosis. S1P1 downregulation in astrocytes was shown to reduce reactive astrogliosis and decrease disease severity in experimental mouse autoimmune encephalomyelitis (Brinkmann, 2009). Thus, S1P1 in astrocytes seems to play critical roles in the neuroimmune-inflammatory response. We also found that astrocyte-specific S1P1 knockdown increased ZO-1 and occludin levels but had no effect on their mRNA levels, suggesting that the increase in TJ protein was not a result of transcriptional activation. Taken together, these findings suggest that astrocytic S1P1 disrupts TJ proteins by promoting neuroinflammation after SE, which in turn disrupts the BBB integrity.

An increasing amount of evidence has implicated BBB disruption in the development of many neurological disorders (Sweeney et al., 2018). Here, we showed that pharmacological inhibition or astrocyte-specific knockdown of S1P1 knockdown of attenuated seizure severity and epilepsy-associated depression-like behaviors. These effects may be related to the infiltration of an intravascular mass into brain after disruption of the BBB integrity, which alters the neuronal microenvironment, increases its excitability, lowers the firing threshold, and ultimately promotes seizures (Archie et al., 2021). Thus, studies on the mechanisms of BBB disruption have the potential to provide new therapeutic strategies for epilepsy.

This study had some limitations. First, we used only young male mice in the experiments, and thus, there might be sex and age biases. Second, we did not perform intracranial electroencephalogram monitoring of the pilocarpine or PTZ-induced epilepsy models, which might have resulted in missing some non-convulsive seizures. Third, our study was based on a mouse model of chemically induced seizures that does not fully reflect epileptic activity in humans. Therefore, validation in additional epilepsy animal models is necessary. Fourth, we only examined the hippocampus. Other regions of the brain may be influenced by BBB disruption after epilepsy; thus, it would be worthwhile to investigate the role of S1P1 in such regions. Fifth, we did not explore the potential molecular signaling mechanisms by which S1P1 regulates inflammation and BBB integrity after SE and we did not confirm whether S1P1 expression is elevated in an in vitro epilepsy model. Finally, we did not confirm whether astrocyte-specific S1P1 overexpression exacerbates SE-induced BBB disruption. We aim to address these limitations in the next phase of our research.

Taken together, our findings suggest that S1P1 plays a disruptive role after SE, in which S1P1 disrupts the BBB integrity by activating astrocytes and releasing inflammatory cytokines. This study showed that specific inhibition or astrocyte-specific knockdown of S1P1 reduces BBB leakage, attenuates seizure severity, and improves epilepsy-associated depression-like behavior, making it a potential novel target for suppression of neuronal injuries in epilepsy patients.

Additional files:

Additional Figure 1 (3.6MB, tif) : Study flowchart.

Study flowchart.

(A) The effects of S1P1 on BBB integrity, inflammation, and behavior in epileptic mice were explored by pharmacological activation or inhibition of S1P1. (B) To investigate the role of S1P1 on the severity of seizures in mice. (C) Investigating whether the disruption of BBB integrity by S1P1 in epileptic mice can be blocked by minocycline. (D) Probing the effects of astrocyte-specific knockdown of S1P1 on BBB integrity, inflammation, and behavior in epileptic mice. BBB: Blood-brain barrier; EB: Evans blue; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; FST: forced swim test; GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein; IL-1β: interleukin-1β; mino: minocycline; PTZ: pentylenetetrazol; qPCR: quantitative polymerase chain reaction; S1P1: sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1; SE: status epilepticus; SPT: sucrose preference test; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α; ZO-1: zonula occludens-1.

Additional Figure 2 (1.3MB, tif) : Expression of S1P2 and S1P3 in the hippocampus after SE.

Expression of S1P2 and S1P3 in the hippocampus after SE.

Western blots (A) and quantification (B) of S1P2 and S1P3 levels after SE. The relative expression was normalized by GAPDH. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4 mice per group), and were analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t-test. GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; S1P2: sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 2; S1P3: sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 3; SE: status epilepticus.

Additional Figure 3 (1MB, tif) : Effect of minocycline on S1P1 promoting the release of inflammatory cytokines in the hippocampus.

Effect of minocycline on S1P1 promoting the release of inflammatory cytokines in the hippocampus.

The ELISA results showed that minocycline inhibited the promotion of IL-1β and TNF-α release by S1P1 after SE in mice. Data are presented as mean M SD (n = 4 mice per group). ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, vs. SE + vehicle group; §§P < 0.01, vs. SE + SEW2871 group; &&&P < 0.001, vs. SE + minocycline (SE + mino) group (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test). ELISA: Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IL-1β: interleukin-1β; S1P1: sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1; SE: status epilepticus; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α.

Additional Figure 4 (1.4MB, tif) : Colocalization analysis of S1P1 with microglia in the hippocampus.

Colocalization analysis of S1P1 with microglia in the hippocampus.

Colocalization of S1P1 (red, Alexa Flour 555) with Iba-1 (green, Alexa Flour 488) in control and SE mice. No obvious colocalization was observed in microglia. Scale bars: 20 μm. DAPI: 4’,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole; Iba-1: ionized calcium binding adapter molecule 1; S1P1: sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1; SE: status epilepticus.

Additional file 1: Open peer review report 1 (83KB, pdf) .

Acknowledgments:

We thank the Institute of Neuropsychiatry, Southeast University for the consultation and instrumentation for this work.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Nos. 82071393 (to HLC), 81830040 (to ZJZ), 82130042 (to ZJZ); Science and Technology Program of Guangdong Province, No. 2018B030334001 (to ZJZ); and the Program of Excellent Talents in Medical Science of Jiangsu Province, No. JCRCA2016006 (to ZJZ).

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Availability of data and materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Open peer reviewer: Alessandro Castorina, University of Technology Sydney, Australia.

P-Reviewer: Castorina A; C-Editor: Zhao M; S-Editors: Yu J, Li CH; L-Editors: Yu J, Song LP; T-Editor: Jia Y

References

- 1.Achar A, Ghosh C. Multiple hurdle mechanism and blood-brain barrier in epilepsy:glucocorticoid receptor-heat shock proteins on drug regulation. Neural Regen Res. (2021);16:2427–2428. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.313046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aoki M, Aoki H, Ramanathan R, Hait NC, Takabe K. Sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling in immune cells and inflammation:roles and therapeutic potential. Mediators Inflamm. (2016);2016:8606878. doi: 10.1155/2016/8606878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Archie SR, Al Shoyaib A, Cucullo L. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction in CNS disorders and putative therapeutic targets:an overview. Pharmaceutics. (2021);13:1779. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13111779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Awad AS, Rouse MD, Khutsishvili K, Huang L, Bolton WK, Lynch KR, Okusa MD. Chronic sphingosine 1-phosphate 1 receptor activation attenuates early-stage diabetic nephropathy independent of lymphocytes. Kidney Int. (2011);79:1090–1098. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bajwa A, Jo SK, Ye H, Huang L, Dondeti KR, Rosin DL, Haase VH, Macdonald TL, Lynch KR, Okusa MD. Activation of sphingosine-1-phosphate 1 receptor in the proximal tubule protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2010);21:955–965. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009060662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer PR, Tolner EA, Keezer MR, Ferrari MD, Sander JW. Headache in people with epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurol. (2021);17:529–544. doi: 10.1038/s41582-021-00516-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brinkmann V. FTY720 (fingolimod) in Multiple Sclerosis:therapeutic effects in the immune and the central nervous system. Br J Pharmacol. (2009);158:1173–1182. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00451.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen SL, Cai GX, Ding HG, Liu XQ, Wang ZH, Jing YW, Han YL, Jiang WQ, Wen MY. JAK/STAT signaling pathway-mediated microRNA-181b promoted blood-brain barrier impairment by targeting sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 in septic rats. Ann Transl Med. (2020);8:1458. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-7024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng H, Di G, Gao CC, He G, Wang X, Han YL, Sun LA, Zhou ML, Jiang X. FTY720 reduces endothelial cell apoptosis and remodels neurovascular unit after experimental traumatic brain injury. Int J Med Sci. (2021);18:304–313. doi: 10.7150/ijms.49066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng YQ, Wu CR, Du MR, Zhou Q, Wu BY, Fu JY, Balawi E, Tan WL, Liao ZB. CircLphn3 protects the blood-brain barrier in traumatic brain injury. Neural Regen Res. (2022);17:812–818. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.322467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doyle TM, Chen Z, Durante M, Salvemini D. Activation of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 in the spinal cord produces mechanohypersensitivity through the activation of inflammasome and IL-1βpathway. J Pain. (2019);20:956–964. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaire BP, Lee CH, Sapkota A, Lee SY, Chun J, Cho HJ, Nam TG, Choi JW. Identification of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor subtype 1 (S1P(1)) as a pathogenic factor in transient focal cerebral ischemia. Mol Neurobiol. (2018);55:2320–2332. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0468-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorter JA, Aronica E, van Vliet EA. The roof is leaking and a storm is raging:repairing the blood-brain barrier in the fight against epilepsy. Epilepsy Curr. (2019);19:177–181. doi: 10.1177/1535759719844750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo L, Gao T, Gao C, Jia X, Ni J, Han C, Wang Y. Stimulation of astrocytic sigma-1 receptor is sufficient to ameliorate inflammation- induced depression. Behav Brain Res. (2021);410:113344. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2021.113344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanael E, Veksler R, Friedman A, Bar-Klein G, Senatorov VV, Jr, Kaufer D, Konstantin L, Elkin M, Chai O, Peery D, Shamir MH. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction in canine epileptic seizures detected by dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Epilepsia. (2019);60:1005–1016. doi: 10.1111/epi.14739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang X, Hussain B, Chang J. Peripheral inflammation and blood-brain barrier disruption:effects and mechanisms. CNS Neurosci Ther. (2021);27:36–47. doi: 10.1111/cns.13569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janisset N, Romariz SAA, Hashiguchi D, Quintella ML, Gimenes C, Yokoyama T, Filev R, Carlini E, Barbosa da Silva R, Faber J, Longo BM. Partial protective effects of cannabidiol against PTZ-induced acute seizures in female rats during the proestrus-estrus transition. Epilepsy Behav. (2022);129:108615. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2022.108615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Löscher W, Friedman A. Structural, molecular, and functional alterations of the blood-brain barrier during epileptogenesis and epilepsy:a cause, consequence, or both? Int J Mol Sci. (2020);21:591. doi: 10.3390/ijms21020591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li XL, Wang B, Yang FB, Chen LG, You J. HOXA11-AS aggravates microglia-induced neuroinflammation after traumatic brain injury. Neural Regen Res. (2022);17:1096–1105. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.322645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu Y, Zhou M, Li Y, Li Y, Hua Y, Fan Y. Minocycline promotes functional recovery in ischemic stroke by modulating microglia polarization through STAT1/STAT6 pathways. Biochem Pharmacol. (2021);186:114464. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2021.114464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mac TL, Tran DS, Quet F, Odermatt P, Preux PM, Tan CT. Epidemiology, aetiology, and clinical management of epilepsy in Asia:a systematic review. Lancet Neurol. (2007);6:533–543. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGinley MP, Cohen JA. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulators in multiple sclerosis and other conditions. Lancet. (2021);398:1184–1194. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00244-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mendes NF, Pansani AP, Carmanhães ERF, Tange P, Meireles JV, Ochikubo M, Chagas JR, da Silva AV, Monteiro de Castro G, Le Sueur-Maluf L. The blood-brain barrier breakdown during acute phase of the pilocarpine model of epilepsy is dynamic and time-dependent. Front Neurol. (2019);10:382. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milikovsky DZ, Ofer J, Senatorov VV, Jr, Friedman AR, Prager O, Sheintuch L, Elazari N, Veksler R, Zelig D, Weissberg I, Bar-Klein G, Swissa E, Hanael E, Ben-Arie G, Schefenbauer O, Kamintsky L, Saar-Ashkenazy R, Shelef I, Shamir MH, Goldberg I, et al. Paroxysmal slow cortical activity in Alzheimer's disease and epilepsy is associated with blood-brain barrier dysfunction. Sci Transl Med. (2019);11:eaaw8954. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw8954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Percie du Sert N, Hurst V, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M, Browne WJ, Clark A, Cuthill IC, Dirnagl U, Emerson M, Garner P, Holgate ST, Howells DW, Karp NA, Lazic SE, Lidster K, MacCallum CJ, Macleod M, Pearl EJ, et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. (2020);18:e3000410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pitkänen A, Löscher W, Vezzani A, Becker AJ, Simonato M, Lukasiuk K, Gröhn O, Bankstahl JP, Friedman A, Aronica E, Gorter JA, Ravizza T, Sisodiya SM, Kokaia M, Beck H. Advances in the development of biomarkers for epilepsy. Lancet Neurol. (2016);15:843–856. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pucilowski O, Overstreet DH, Rezvani AH, Janowsky DS. Chronic mild stress-induced anhedonia:greater effect in a genetic rat model of depression. Physiol Behav. (1993);54:1215–1220. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90351-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Racine RJ. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. (1972);32:281–294. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(72)90177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rempe RG, Hartz AMS, Soldner ELB, Sokola BS, Alluri SR, Abner EL, Kryscio RJ, Pekcec A, Schlichtiger J, Bauer B. Matrix metalloproteinase-mediated blood-brain barrier dysfunction in epilepsy. J Neurosci. (2018);38:4301–4315. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2751-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roggeri A, Schepers M, Tiane A, Rombaut B, van Veggel L, Hellings N, Prickaerts J, Pittaluga A, Vanmierlo T. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulators and oligodendroglial cells:beyond immunomodulation. Int J Mol Sci. (2020);21:7537. doi: 10.3390/ijms21207537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ:25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. (2012);9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shehata NI, Abdelsamad MA, Amin HAA, Sadik NAH, Shaheen AA. Ameliorating effect of ketogenic diet on acute status epilepticus: Insights into biochemical and histological changes in rat hippocampus. J Food Biochem. (2022) doi: 10.1111/jfbc.14217. doi:10.1111/jfbc.14217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi K, Tian DC, Li ZG, Ducruet AF, Lawton MT, Shi FD. Global brain inflammation in stroke. Lancet Neurol. (2019);18:1058–1066. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30078-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sweeney MD, Sagare AP, Zlokovic BV. Blood-brain barrier breakdown in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. (2018);14:133–150. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang Y, Liu J, Wang Y, Yang L, Han B, Zhang Y, Bai Y, Shen L, Li M, Jiang T, Ye Q, Yu X, Huang R, Zhang Z, Xu Y, Yao H. PARP14 inhibits microglial activation via LPAR5 to promote post-stroke functional recovery. Autophagy. (2021);17:2905–2922. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2020.1847799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uprety A, Kang Y, Kim SY. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction as a potential therapeutic target for neurodegenerative disorders. Arch Pharm Res. (2021);44:487–498. doi: 10.1007/s12272-021-01332-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Doorn R, Van Horssen J, Verzijl D, Witte M, Ronken E, Van Het Hof B, Lakeman K, Dijkstra CD, Van Der Valk P, Reijerkerk A, Alewijnse AE, Peters SL, De Vries HE. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 and 3 are upregulated in multiple sclerosis lesions. Glia. (2010);58:1465–1476. doi: 10.1002/glia.21021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weichand B, Popp R, Dziumbla S, Mora J, Strack E, Elwakeel E, Frank AC, Scholich K, Pierre S, Syed SN, Olesch C, Ringleb J, Ören B, Döring C, Savai R, Jung M, von Knethen A, Levkau B, Fleming I, Weigert A, et al. S1PR1 on tumor-associated macrophages promotes lymphangiogenesis and metastasis via NLRP3/IL-1β. J Exp Med. (2017);214:2695–2713. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wood H. Blood-brain barrier pathology linked to epilepsy in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. (2020);16:66. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0304-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiang P, Chew WS, Seow WL, Lam BWS, Ong WY, Herr DR. The S1P(2) receptor regulates blood-brain barrier integrity and leukocyte extravasation with implications for neurodegenerative disease. Neurochem Int. (2021);146:105018. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2021.105018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu D, Gao Q, Wang F, Peng Q, Wang G, Wei Q, Lei S, Zhao S, Zhang L, Guo F. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 3 is implicated in BBB injury via the CCL2-CCR2 axis following acute intracerebral hemorrhage. CNS Neurosci Ther. (2021);27:674–686. doi: 10.1111/cns.13626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xue M, Yong VW. Neuroinflammation in intracerebral haemorrhage:immunotherapies with potential for translation. Lancet Neurol. (2020);19:1023–1032. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30364-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yanagida K, Liu CH, Faraco G, Galvani S, Smith HK, Burg N, Anrather J, Sanchez T, Iadecola C, Hla T. Size-selective opening of the blood-brain barrier by targeting endothelial sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2017);114:4531–4536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618659114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng Z, Zeng YZ, Ren K, Zhu X, Tan Y, Li Y, Li Q, Yi GH. S1P promotes inflammation-induced tube formation by HLECs via the S1PR1/NF-κB pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. (2019);66:224–235. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu X, Zhang A, Dong J, Yao Y, Zhu M, Xu K, Al Hamda MH. MicroRNA-23a contributes to hippocampal neuronal injuries and spatial memory impairment in an experimental model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Res Bull. (2019);152:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2019.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu X, Dong J, Han B, Huang R, Zhang A, Xia Z, Chang H, Chao J, Yao H. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase contributes to PTZ kindling epilepsy-induced hippocampal endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative damage. Front Cell Neurosci. (2017);11:377. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu X, Li X, Zhu M, Xu K, Yang L, Han B, Huang R, Zhang A, Yao H. Metalloprotease Adam10 suppresses epilepsy through repression of hippocampal neuroinflammation. J Neuroinflammation. (2018);15:221. doi: 10.1186/s12974-018-1260-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Study flowchart.

(A) The effects of S1P1 on BBB integrity, inflammation, and behavior in epileptic mice were explored by pharmacological activation or inhibition of S1P1. (B) To investigate the role of S1P1 on the severity of seizures in mice. (C) Investigating whether the disruption of BBB integrity by S1P1 in epileptic mice can be blocked by minocycline. (D) Probing the effects of astrocyte-specific knockdown of S1P1 on BBB integrity, inflammation, and behavior in epileptic mice. BBB: Blood-brain barrier; EB: Evans blue; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; FST: forced swim test; GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein; IL-1β: interleukin-1β; mino: minocycline; PTZ: pentylenetetrazol; qPCR: quantitative polymerase chain reaction; S1P1: sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1; SE: status epilepticus; SPT: sucrose preference test; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α; ZO-1: zonula occludens-1.

Expression of S1P2 and S1P3 in the hippocampus after SE.

Western blots (A) and quantification (B) of S1P2 and S1P3 levels after SE. The relative expression was normalized by GAPDH. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4 mice per group), and were analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t-test. GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; S1P2: sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 2; S1P3: sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 3; SE: status epilepticus.

Effect of minocycline on S1P1 promoting the release of inflammatory cytokines in the hippocampus.

The ELISA results showed that minocycline inhibited the promotion of IL-1β and TNF-α release by S1P1 after SE in mice. Data are presented as mean M SD (n = 4 mice per group). ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, vs. SE + vehicle group; §§P < 0.01, vs. SE + SEW2871 group; &&&P < 0.001, vs. SE + minocycline (SE + mino) group (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test). ELISA: Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IL-1β: interleukin-1β; S1P1: sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1; SE: status epilepticus; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α.

Colocalization analysis of S1P1 with microglia in the hippocampus.

Colocalization of S1P1 (red, Alexa Flour 555) with Iba-1 (green, Alexa Flour 488) in control and SE mice. No obvious colocalization was observed in microglia. Scale bars: 20 μm. DAPI: 4’,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole; Iba-1: ionized calcium binding adapter molecule 1; S1P1: sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1; SE: status epilepticus.