Key Words: apoptosis, M1 polarization, M2 polarization, microglia, neuroinflammation, PARP14, silencing, spinal cord injury, STAT1 pathway, STAT6 pathway

Abstract

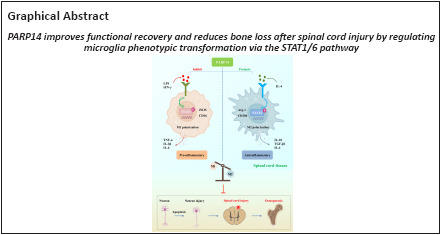

Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase family member 14 (PARP14), which is an intracellular mono(ADP-ribosyl) transferase, has been reported to promote post-stroke functional recovery, but its role in spinal cord injury (SCI) remains unclear. To investigate this, a T10 spinal cord contusion model was established in C57BL/6 mice, and immediately after the injury PARP14 shRNA-carrying lentivirus was injected 1 mm from the injury site to silence PARP14 expression. We found that PARP14 was up-regulated in the injured spinal cord and that lentivirus-mediated downregulation of PARP14 aggravated functional impairment after injury, accompanied by obvious neuronal apoptosis, severe neuroinflammation, and slight bone loss. Furthermore, PARP14 levels were elevated in microglia after SCI, PARP14 knockdown activated microglia in the spinal cord and promoted a shift from M2-polarized microglia (anti-inflammatory phenotype) to M1-polarized microglia (pro-inflammatory phenotype) that may have been mediated by the signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) 1/6 pathway. Next, microglia M1 and M2 polarization were induced in vitro using lipopolysaccharide/interferon-γ and interleukin-4, respectively. The results showed that PARP14 knockdown promoted microglia M1 polarization, accompanied by activation of the STAT1 pathway. In addition, PARP14 overexpression made microglia more prone to M2 polarization and further activated the STAT6 pathway. In conclusion, these findings suggest that PARP14 may improve functional recovery after SCI by regulating the phenotypic transformation of microglia via the STAT1/6 pathway.

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a debilitating condition, with high mortality and disability rates. It can induce a series of clinical symptoms, including motor dysfunction, muscle atrophy, osteoporosis, and more (McDonald and Sadowsky, 2002; Battaglino et al., 2012). Primary injury occurs immediately after the initial injury and is irreversible. Secondary injury, which aggravates neurological dysfunction, is reversible and often causes a series of cellular and molecular events, such as microglia activation and neuroinflammation, that lead to severe nerve damage and dysfunction (Li et al., 2016; He et al., 2017; Han et al., 2018). Among these events, activation of microglia and the subsequent release of inflammatory factors often lead directly to neuronal death (Wang et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2020). Inhibition of microglia activation and promotion of M2-type microglia polarization have been shown to improve SCI by alleviating neuroinflammation and neuronal apoptosis, among other effects, and ultimately promote the recovery of motor function and alleviate SCI-induced neuropathic pain (Lee et al., 2018; Kobashi et al., 2020; Poulen et al., 2021). Therefore, exploring potential molecular targets for inhibiting SCI-induced microglia activation and the subsequent inflammatory response may provide new directions for the clinical treatment of SCI.

Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase family member 14 (PARP14), which is a member of the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase family, catalyzes the post-translational ribosylation of proteins and uses nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide as the substrate to modify the target protein by mono- or poly-ADP ribosylation (Amé et al., 2004; Vyas et al., 2014). PARP14 expression is significantly elevated in the area surrounding cerebral infarction in a mouse model of stroke, and both PARP14 knockout and treatment with a PARP14 inhibitor aggravated functional damage of mice with stroke and increased the infarct volume (Tang et al., 2021), suggesting that PARP14 plays a protective role in central nervous system-related diseases. GEO database (GSE5296 and GSE52763) analysis showed that PARP14 expression was significantly up-regulated at the site of spinal cord lesion 1, 3, 7, 21, and 28 days after injury (Additional Figure 1 (1MB, tif) ). However, the function of PARP14 in SCI is unknown.

Microglia are important nervous system-specific immune cells that serve as tissue-resident macrophages involved in maintenance of the neural environment, response to injury, and repair (Orihuela et al., 2016; Gualerzi et al., 2021). There are two known types of microglia/macrophage polarization: 1) M1 polarization, which occurs through pro-inflammatory pathways; and 2) M2 polarization, which occurs through anti-inflammatory pathways and is usually associated with anti-inflammatory responses, tissue repair, and metabolic homeostasis (Mills et al., 2000). PARP14 silencing induces the expression of pro-inflammatory genes in interferon (IFN)-γ-treated macrophages but inhibits the expression of anti-inflammatory genes in interleukin (IL)-4-treated macrophages (Iwata et al., 2016). In microglia subjected to glucose and oxygen deprivation, PARP14 overexpression reduces the expression of lysophosphatidic acid receptor 5 (LPAR5) (Tang et al., 2021). LPAR5 has been reported to mediate microglia polarization to the pro-inflammatory phenotype (Plastira et al., 2017). The findings described above suggest that PARP14 may participate in the SCI pathological process by regulating microglia polarization. Furthermore, microglia can be induced to polarize to the M1 phenotype via signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) 1 pathway activation or to the M2 phenotype via STAT6 pathway activation, and blockade of the STAT1 pathway and activation of the STAT6 pathway can alleviate SCI (Lu et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021). PARP14 has been reported to decrease STAT1 phosphorylation but increase STAT6 phosphorylation, suggesting that PARP14 blocks the STAT1 pathway and activates the STAT6 pathway. Thus, PARP14 may affect SCI progression by regulating the microglia polarization via the STAT1/6 pathway.

SCI patients usually exhibit rapid and persistent bone loss due to impaired motor function (Biering-Sørensen et al., 1988; Dauty et al., 2000). Patients with SCI have an increased incidence of fractures due to reduced bone mechanical integrity (Zehnder et al., 2004). Additionally, increased secretion of pro-inflammatory factors stimulates osteoclast activity after SCI, leading to abnormal bone loss (Shams et al., 2021). However, whether PARP14 can affect SCI-induced bone loss by regulating SCI progression is unknown. On the basis of the evidence described above, we speculated that PARP14 might improve motor function and alleviate neuroinflammation and other pathological symptoms after SCI by inhibiting microglia polarization to the M1 pro-inflammatory phenotype, thereby inhibiting SCI-induced bone loss. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore the expression, function, and mechanism of PARP14 in SCI.

Methods

Animals

C57BL/6J mice (n = 176, specific pathogen-free level, female, 6–8 weeks, weight 22 ± 2 g) were used for the animal experiments. The mice were purchased from Beijing Huafukang Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China; license No. SCXK (Jing) 2019-0008). The use of female mice was based on previous studies (Gaviria et al., 2002; Engesser-Cesar et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2019). A previous study has shown no significant differences in clinical treatment, mortality, comorbidity rates, and secondary complications between male and female patients with SCI (Furlan et al., 2005). Both male and female patients showed the same pathological features, such as neuroinflammation, motor dysfunction, and neuronal apoptosis (Chan et al., 2013). Furthermore, there is currently no evidence that the effects of PARP14 on the pathological processes are gender-differentiated. Therefore, this study used female mice for modeling.

Mice were kept under controlled conditions with a 12/12-hour light/dark cycle at 22 ± 1°C and 45–55% humidity with free access to food and water. All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of China Medical University (approval No. CMU2021418, approval date: September 16, 2021). All animal experiments followed the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th ed) (National Research Council, 2011).

The establishment of SCI model and lentivirus injection

Animals were randomly divided into four groups: sham (n = 36), SCI (n = 60), SCI + Lv-shNC (n = 40), and SCI + Lv-shPARP14 (n = 40). The SCI model was established as previously described (Wang et al., 2019). Mice were anesthetized by 1% sodium pentobarbital injection (intraperitoneal, 45 mg/kg; Xiya Reagent, Linyi, China). After careful dissection of the paravertebral muscles, a T10 laminectomy was performed. For the SCI group, a home-made impactor (3-g weight, 1.5-mm diameter) was dropped from a height of 25 mm onto the spinal cord to generate a moderate contusive injury. Mice in the sham group underwent laminectomy only without contusion injury.

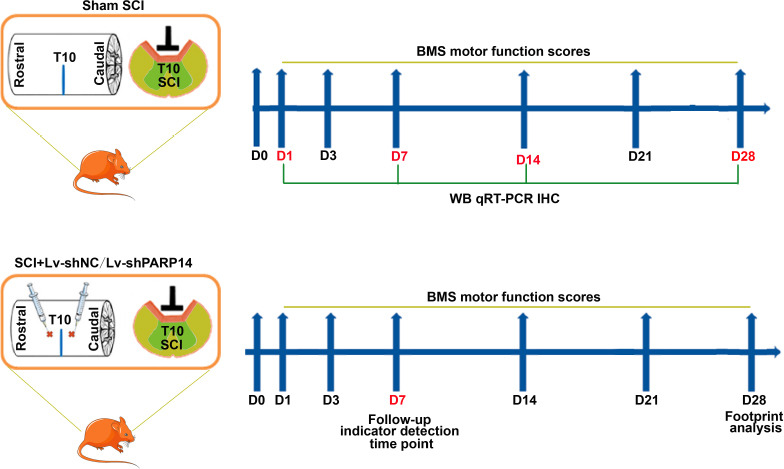

Lentivirus was injected as previously described (Patel et al., 2021). Briefly, SCI mice immediately received lentivirus containing short hairpin RNAs specifically targeting PARP14 (SCI + Lv-shPARP14 group) or negative control (NC, SCI + Lv-shNC group). The lentiviral vectors were purchased from Hunan Fenghui Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Changsha, China). Sites approximately 1 mm rostral and caudal to the lesion epicenter (0.5 mm in depth) was injected with 1 µL of virus (1 × 108 TU/mL) at a rate of approximately 1 µL/min using a Hamilton syringe. At 1, 7, 14, and 28 days post-SCI, mice were euthanized with 1% sodium pentobarbital (intraperitoneal, 200 mg/kg), and spinal cord tissues at the injury epicenter were collected for subsequent experiments. At 28 days post-SCI, femurs were removed from the sacrificed mice. After removing the muscles, the femurs were fixed in 10% neutral formaldehyde solution, or the femoral metaphysis was collected and stored at –80°C for subsequent experiments. The timeline of the experimental protocol is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Timeline of the experimental protocol.

BMS: Basso Mouse Scale; SCI: spinal cord injury.

Cell culture, infection, and treatment

The BV2 (mouse microglia) cell line was obtained from iCell (Shanghai, China, Cat# iCell-m011, RRID: CVCL-0182) and identified by STR. Cells stored in liquid nitrogen were thawed in a 37°C water bath. After thawing, the cells were centrifuged at 106 × g), and the supernatant was discarded. The cells were then resuspended in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (Servicebio, Wuhan, China) containing fetal bovine serum (10%) and inoculated into six-well plates. After 24 hours of culture in a 37°C incubator supplemented with 5% CO2, the cell status was observed, and culturing was continued with fresh medium. After cell passaging, cell counts were performed with trypan blue staining (Solarbio, Beijing, China), followed by cell treatment and infection.

Lentiviral plasmids were used to silence PARP14. A short hairpin RNA specifically targeting PARP14 was cloned into lentiviral plasmids to achieve PARP14 knockdown (Lv-shPARP14). Lv-shNC served as the negative control. Because the coding sequence region of PARP14 exceeds 2 kbp, in our experience lentiviral plasmids are not suitable for PARP14 overexpression. Therefore, an adenovirus plasmid was used to construct a recombinant adenovirus PARP14 overexpression plasmid (Ad-PARP14) because it can carry a fragment exceeding 2 kbp. Ad-NC was used as the NC. BV cells were infected with the lentiviral plasmids or adenovirus plasmids at a multiplicity of infection of 20. Seventy-two hours after infection, follow-up experiments were carried out.

For M1 polarization induction, 72 hours post-infection, BV cells were stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS)/IFN-γ for 24 hours. For M2 polarization induction, 72 hours post-infection, BV cells were stimulated with IL-4 for 24 hours.

Basso Mouse Scale score

The Basso Mouse Scale (BMS) score was used to assess locomotive function at the indicated times (0, 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days after SCI) (Basso et al., 2006). During this period, mouse hindlimb motor function was scored according to the BMS, with scores ranging from 0 (no hindlimb movement) to 9 (normal movement and coordinated gait), as previously described (Han et al., 2018).

Footprint analysis

Footprint analysis was performed as previously described (Zeng et al., 2019). On day 28 after injury, mouse gait behavior and motor coordination were evaluated. The mice’s forelimbs and hind paws were painted red and blue respectively, and the mice were placed on a track covered with white paper and encouraged to walk directly to the finish line to assess their gait and coordination.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was conducted to assess the mRNA expression level of PARP14 and bone loss-related genes. Total RNA was obtained from spinal cord tissues (injury site, 28 days post-injury), BV2 cells (1 × 106 cells per group), and bone tissues (obtained from femoral metaphysis at 28 days post-injury) using TRIzol (BioTeke, Beijing, China) and then reverse transcribed into complementary DNA using reverse transcriptase (BeyoRT II M-MLV system, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The qPCR reaction was performed using PCR MasterMix (Solarbio) and SYBR Green (Solarbio). Primers were designed by GenScript (Beijing, China). β-Actin served as a loading control. Data were analyzed using the 2–ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). The thermocycling conditions used for the qPCR reaction were as follows: 94°C for 5 minutes, 40 cycles of 94°C for 10 seconds, 60°C for 20 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds. The reaction components were as follows: cDNA template (1 µL), upstream (0.5 µL) and downstream (0.5 µL) primers, SYBR Green (0.3 µL), BeyoRT II M-MLV reverse transcriptase (10 µL), and ddH2O (7.7 µL). The sequences of the primers used for qPCR are shown in Additional Table 1.

Additional Table 1.

Primers used for quantitative polymerase chain reaction

| Gene | Sequence (5’-3’) |

|---|---|

| PARP14 | Forward: TTG TTG GTG GGA ATG AT |

| Reverse: GTT TGG GTC CTG TTG AG | |

| OPG | Forward: CTT CTT GCC TTG ATG GA |

| Reverse: TTG GGA AAG TGG GAT GT | |

| RANKL | Forward: ATG AAA GGA GGG AGC ACG AA |

| Reverse: AAG GGT TGG ACA CCT GAA TG |

OPG: Osteoprotegerin; PARP14: poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase, member 14; RANKL: receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand.

Western blot analysis

Total protein from spinal cord tissues and BV2 cells (2 × 106 cells per group) was extracted using Cell Lysis Buffer for Western and Immunoprecipitation (Beyotime), the protein concentration was determined by using a BCA protein concentration assay kit (Beyotime). The protein was then separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (8%, 12%, or 15% gel), and then transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. The membranes were blocked with skim milk (5%) and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C, followed by the incubation with secondary antibody for 45 minutes at 37°C. The antibodies used for western blotting are shown in Additional Table 2. Electrochemiluminescence solution (Beyotime) was used to visualize and quantify the immunoblots. Protein levels were normalized to β-actin.

Additional Table 2.

Antibodies used for western blot analysis

| Antibody | Manufacturer | Catalog number | RRID number | Species | Dilution | Monoclonal antibody/polyclonal antibody |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | ||||||

| antibody | ||||||

| PARP14 | Santa Cruz | sc-377150 | N/A | Mice | 1:300 | Monoclonal |

| Biotechnology | ||||||

| Cleaved | Affinity | AF7022 | AB_2835326 | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Polyclonal |

| caspase 3 | ||||||

| Bax | Affinity | AF0120 | AB_2833304 | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Polyclonal |

| Bcl-2 | Affinity | AF6139 | AB_2835021 | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Polyclonal |

| Bcl-xl | Affinity | AF6414 | AB_2835244 | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Polyclonal |

| iNOS | Affinity | AF0199 | AB_2833391 | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Polyclonal |

| CD16 | Affinity | DF7007 | AB_2838963 | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Polyclonal |

| Arg-1 | Affinity | DF6657 | AB_2838619 | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Polyclonal |

| CD206 | Affinity | DF4149 | AB_2836514 | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Polyclonal |

| STAT1 | Affinity | AF6300 | AB_2835149 | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Polyclonal |

| p-STAT1 | Affinity | AF3300 | AB_2834719 | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Polyclonal |

| STAT6 | Affinity | AF6302 | AB_2835151 | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Polyclonal |

| p-STAT6 | Affinity | AF3301 | AB_2834720 | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Polyclonal |

| β-Actin | Santa Cruz | sc-47778 | AB_626632 | Mice | 1:1000 | Monoclonal |

| Biotechnology | ||||||

| Secondary | ||||||

| antibody | ||||||

| Goat | Beyotime | A0208 | AB_2892644 | Rabbit | 1:5000 | N/A |

| anti-rabbit IgG | ||||||

| Goat | Beyotime | A0216 | AB_2860575 | Mice | 1:5000 | N/A |

| anti-mouse | ||||||

| IgG |

Arg-1: Arginase-1; iNOS: inducible nitric oxide synthase; PARP14: poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase, member 14;

STAT: signal transducer and activator of transcription.

Immunohistochemistry

PARP14 expression in spinal cord tissues at the lesion site was measured by immunohistochemistry at 1, 7, 14, and 28 days after SCI. Briefly, spinal cord tissue samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated, embedded, and sliced. After being dehydrated in a series of gradient alcohols, the spinal cord sections were incubated with 3% H2O2 at room temperature (approximately 20 ± 2°C) for 15 minutes to remove endogenous peroxidase activity. Then, sections were blocked with bovine serum albumin (1%) at room temperature (15 minutes) and incubated with primary mouse antibody against PARP14 (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA; Cat# sc-377150, RRID: AB_2920825) overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with the secondary antibody (horseradish peroxidase-conjugated; mice, 1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA; Cat# 31430; RRID: AB_228307) at room temperature (20 ± 2°C) for 1 hour. After being treated with 2,4-diaminobutyric acid (Maixin Biotechnology, Fuzhou, China), counterstained with hematoxylin (Solarbio), and dehydrated in an alcohol gradient, the PARP14-positive cells were observed under a light microscope (400×, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Nissl staining

Significant inflammatory responses often occur in the early stages of traumatic diseases (David and Kroner, 2011). Therefore, considering the timing of the inflammatory response and the purpose of this study, the effect of PARP14 on neuronal damage was examined at 7 days after SCI, similar to previous studies (Khayrullina et al., 2015; Jiang et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2018). Briefly, the 5-µm-thick paraffin sections from spinal cord obtained at 7 days post-SCI were deparaffinized, dehydrated in an alcohol gradient, stained with cresyl violet (Sinopharm, Shanghai, China), and then mounted with neutral balsam. Finally, the number of Nissl-positive cells was calculated.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling and NeuN co-staining

Neuronal apoptosis in the spinal cord at 7 days after SCI was measured by performing terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) and NeuN co-staining in spinal cord sections. After permeabilization with Triton X-100 (0.1%,) at room temperature for 8 minutes, the sections were treated with TUNEL reaction solution (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) for 1 hour, blocked in 1% bovine serum albumin (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) for 1 hour, and then treated with primary antibody against NeuN (mice, 1:200; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, UK; Cat# ab104224; RRID: AB_10711040) overnight at 4°C. After washing, the sections were treated with Cy3-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific; Cat# A-21424; RRID: AB_141780) for 1 hour at room temperature (20 ± 2°C). The nuclei were stained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Aladdin, Shanghai, China). Images were observed under a fluorescence microscope (400×, Olympus).

Immunofluorescence

After dewaxing and hydration, spinal cord sections and cell sheets (1 × 105 cells per group) were incubated with primary antibodies. For immunofluorescence double staining, slides were co-incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody against PARP14 (RABBIT; 1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Cat# sc-377150; RRID: AB_2920825) and ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1, mice; 1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Cat# sc-32725; RRID: AB_667733), p-STAT6 (rabbit; 1:100; Affinity Biosciences, Cincinnati, OH, USA; Cat# AF3301; RRID: AB_2834720) and Iba1 (mice; 1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), p-STAT1 (rabbit; 1:100; Affinity; Cat# AF3300; RRID: AB_2834719) and Iba1 (mice; 1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) (rabbit; 1:100; Affinity; Cat# AF0199; RRID: AB_2833391) and Iba1 (mice; 1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or arginase-1 (Arg-1) (rabbit; 1:100; Affinity; Cat# DF6657; RRID: AB_2838619) and Iba1 (mice; 1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The slides were then co-incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:200; Abcam; Cat# ab6717; RRID: AB_955238) and Cy3-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific; Cat# A-21424; RRID: AB_141780) for 90 minutes at room temperature. The nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Aladdin). Immunofluorescence single staining was performed as described above. The stained cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope (400×).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The concentration of pro-inflammatory (tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-1β, IL-6) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, IL-4) factors in spinal cord samples or cell supernatant (obtained by centrifugation after tissue homogenization) was measured using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (Multi-Science, Hangzhou, China).

Micro-computed tomography analysis

The micro-computed tomography analysis was conducted using a QuantumGX Micro-CT Imaging System (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) at 28 days post-SCI. To evaluate the microarchitecture of the femoral metaphysis, the trabecular bone was excised as the region of interest. The trabecular bone volume fraction, trabecular number, trabecular thickness, and trabecular spacing were calculated within the delimited region of interest.

Bone histomorphometric detection

Twenty-eight days after SCI, bone histomorphometric detection was conducted. After dewaxing and hydration, the sections obtained from the femoral metaphysis were subjected to hematoxylin and eosin staining and tartrate-resistant acidic phosphatase (TRAP) staining. For hematoxylin (Solarbio) and eosin (Sangon Biotech) staining, the sections were stained sequentially with hematoxylin and eosin. For TRAP staining, the sections were first fixed in TRAP fixative (Solarbio) for 1 minute at 4°C and treated with TRAP incubation solution at 37°C for 60 minutes. After being counterstained with hematoxylin for 3 minutes, the sections were rinsed with tap water to wash out the blue stain. After staining, images were obtained using an Olympus BX53 fluorescence microscope (400×) to observe TRAP-positive cells and pathological changes in the bone tissue.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 8.0.1 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA, www.graphpad.com) was used to analyze the data. The evaluators were blinded to the group assignments. Six mice from each group were sacrificed at each time point for in vivo detection. Effect sizes for in vivo detection were calculated by post hoc power analysis to confirm the power of the analysis (Faul et al., 2007; Plate et al., 2019). Three technical replicates were performed for each experiment. Comparisons between the two groups were made by Student’s t-test. One-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used for multiple comparisons. All values are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

PARP14 is upregulated in spinal cord tissues after SCI, and PARP14 deficiency exacerbates motor dysfunction in mice with SCI

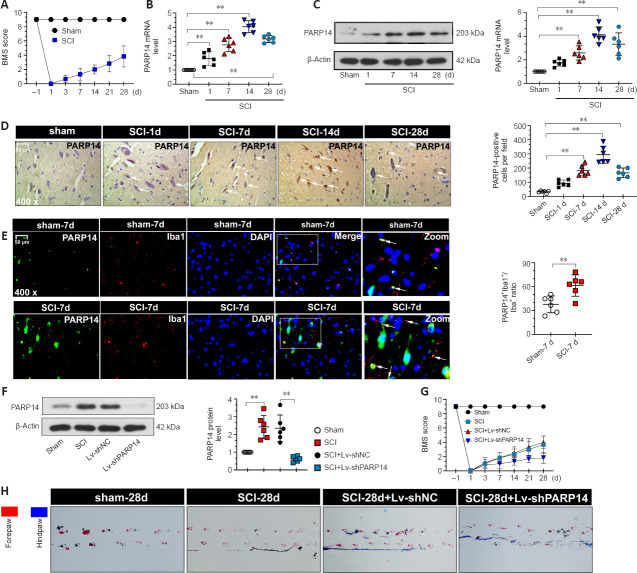

GEO database (GSE5296 and GSE52763) analysis showed that PARP14 expression was markedly increased at sites of spinal cord 1, 3, 7, 21, and 28 days after SCI (Additional Figure 1 (1MB, tif) ). To explore the role of PARP14 in SCI, we first established the mouse model of SCI. The locomotor function of the mice in each group was analyzed by determining the BMS score. The results showed that mice with SCI had lower scores than the sham mice (Figure 2A), suggesting that the SCI mouse model was established successfully. PARP14 expression in the spinal cord was detected by qPCR, western blot analysis, and immunohistochemistry staining at 1, 7, 14, and 28 days after injury. PARP14 protein and mRNA expression were markedly increased in mice with SCI compared with those in the sham group (Figure 2B–D). Moreover, immunofluorescence double-staining for PARP14 and Iba1 (a microglia marker) showed that compared with the sham group, PARP14 expression was also increased in microglia after SCI (Figure 2E). Next, we knocked down PARP14 expression in the spinal cord by injecting PARP14 short hairpin RNA-carrying lentivirus (Lv-shPARP14) or NC (Lv-shNC) approximately 1 mm above and below the injury site. Our results showed that Lv-shPARP14 injection significantly decreased PARP14 protein expression in the spinal cord 7 days after SCI (Figure 2F). The behavioral assessment demonstrated that administration of LV-shPARP14 started to enhance motor dysfunction 3 days after injection, compared with mice receiving the LV-shNC, and the accelerated progression of motor dysfunction persisted until the final observation at 28 days post-injury (Figure 2G). Footprint analysis (28 days post-SCI) showed that mice with SCI had uncoordinated gaits and exhibited extensive drag of both hindlimbs, and silencing PARP14 aggravated these behaviors (Figure 2H), indicating that PARP14 may play a compensatory role in SCI.

Figure 2.

PARP14 is upregulated in spinal cord tissues after SCI, and PARP14 deficiency exacerbates motor dysfunction in a mouse model of spinal cord injury.

(A) Mice in the SCI group exhibited lower BMS scores at different time points compared with the sham group. (B–D) qPCR, western blot analysis, and immunohistochemistry showed that PARP14 expression (arrows) was increased at 1, 7, 14, and 28 days after SCI. (E) Representative images showing PARP14+/Iba1+ immunofluorescence staining at 7 days post-SCI. PARP14 expression in microglia was increased. White arrows indicate PARP14+ (green, FITC-labeled)/Iba1+ (red, Cy3-labeled, microglia marker) cells. Scale bars: 50 µm in D and E. (F) PARP14 protein expression was measured by western blot analysis 7 days post-SCI) in mice that received Lv-shPARP14 or Lv-shNC. PARP14 protein expression was increased in mice with SCI and decreased by injection with Lv-shPARP14. (G) Lv-shPARP14 injection enhanced the SCI-induced decrease in BMS score at different time points. (H) Footprint analysis was performed for each group 28 days post-SCI. Red indicates the forepaws, and blue indicates the hindlimb. Values are shown as mean ± SD (n = 6). **P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test analysis (E, F)or one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (A–D, G)). Images were taken from the gray matter ventral horn at the injury site. Spinal cord tissues from the injury site were used for qPCR and western blot detection. BMS: Basso Mouse Scale; DAPI: 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; FITC: fluorescein isothiocyanate; Iba1: ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1; PARP14: poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase, member 14; qPCR: quantitative polymerase chain reaction; SCI: spinal cord injury.

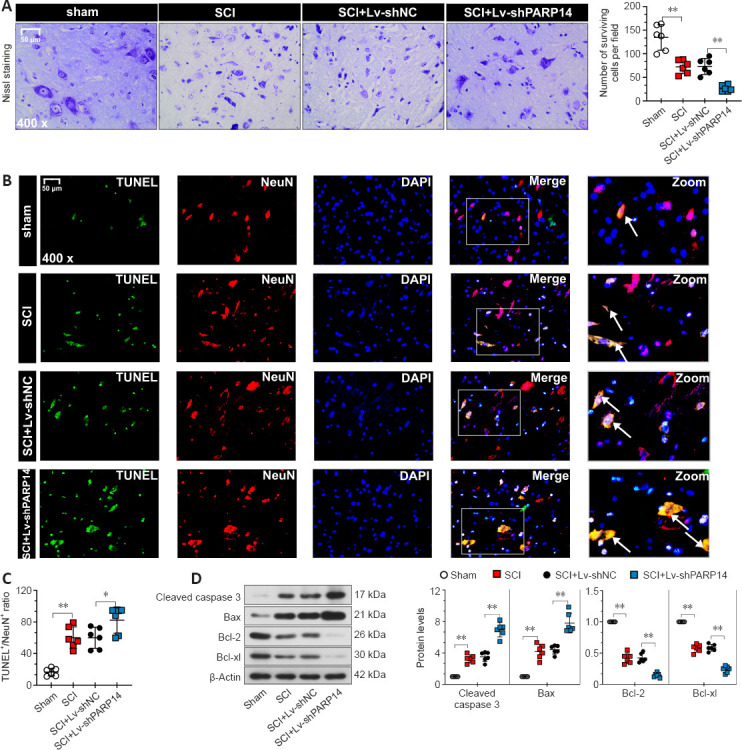

PARP14 deficiency exacerbates SCI-induced neuronal apoptosis

Next, we explored the role of PARP14 in neuronal apoptosis. Nissl staining for gray ventral motor neurons showed that mice 7 days post-SCI had more neuron loss than that in the sham mice, and PARP14 knockdown further enhanced SCI-induced neuron loss (Figure 3A). TUNEL and NeuN (a neuronal marker) co-staining showed that compared with the sham group, mice 7 days post-SCI exhibited increased neuronal apoptosis, which was enhanced by PARP14 downregulation (Figure 3B and C). Western blot analysis of apoptosis-related factors showed that cleaved caspase 3 and Bax (pro-apoptotic factors) levels were elevated in the spinal cord of SCI mice, whereas Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl (anti-apoptosis factors) levels were markedly decreased, and PARP14 silencing aggravated both of these trends (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

PARP14 deficiency exacerbates SCI-induced neuronal apoptosis at 7 days post-SCI.

(A) Representative images and quantitative analysis of Nissl staining in each group. Lv-shPARP14 injection increased SCI-induced neuronal loss. (B, C) Representative images and quantitative analysis showing TUNEL+/NeuN+ immunofluorescence staining. Lv-shPARP14 injection increased SCI-induced neuronal apoptosis. White arrows indicate TUNEL+ (green, apoptosis cells)/NeuN+ (red, Cy3-labeled, neuronal marker) cells. Scale bars: 50 µm in A and B. (D) Western blot analysis of cleaved caspase 3, bax, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xl in each group. Lv-shPARP14 injection enhanced the SCI-induced increase in cleaved caspase 3 and bax (pro-apoptotic factors) expression and decrease in Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl (anti-apoptotic factors) expression. Values are shown as mean ± SD (n = 6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test). Images were taken from the gray matter ventral horn at the injury site. Spinal cord tissues from the injury site were used for western blot detection. DAPI: 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole; PARP14: poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase, member 14; SCI: spinal cord injury; TUNEL: terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling.

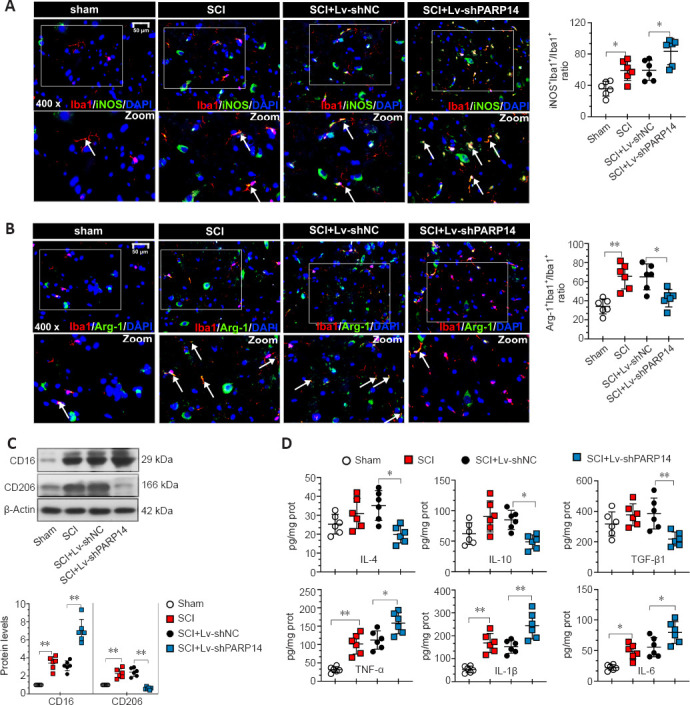

PARP14 deficiency exacerbates the shift of M2-polarized microglia to M1-polarized microglia in mice with SCI

The microglia activation-mediated neuroinflammatory response is an important contributing factor to secondary injury in SCI. Moreover, PARP14 has been reported to regulate macrophage polarization (Iwata et al., 2016). Thus, we explored whether PARP14 regulates microglia polarization in SCI. Double immunofluorescent staining was performed for Iba1 (microglia marker) and M1 (pro-inflammatory phenotype)-associated iNOS or M2 (anti-inflammatory phenotype)-associated Arg-1 (Lisi et al., 2017). The results showed that iNOS and Arg-1 expression were increased in the microglia of mice 7 days post-SCI, and that PARP14 silencing increased iNOS expression but decreased Arg-1 expression (Figure 4A and B). Moreover, western blot analysis indicated that M1-related factor CD16 and M2-related factor CD206 protein levels in the spinal cord of mice 7 days post-SCI were increased, and that PARP14 downregulation significantly increased CD16 expression but decreased CD206 expression (Figure 4C). In addition, PARP14 knockdown promoted the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6) and reduced the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β1, and IL-4) in mice 7 days post-SCI (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

PARP14 deficiency exacerbates the shift of M2-polarized microglia to M1-polarized microglia in mice 7 days post-SCI.

(A) Representative images and quantitative analysis showing iNOS+/Iba1+ immunofluorescence staining. Lv-shPARP14 injection enhanced the SCI-induced increase in iNOS expression (pro-inflammatory phenotype). White arrows indicate iNOS+ (green, FITC-labeled)/Iba1+ (red, Cy3-labeled, microglia marker) cells. (B) Representative images and quantitative analysis showing Arg-1+/Iba1+ immunofluorescence staining. Lv-shPARP14 injection reversed the SCI-induced increase in Arg-1 expression (anti-inflammatory phenotype). White arrows indicate Arg-1+ (green, FITC-labeled)/Iba1+ (red, Cy3-labeled, microglia marker) cells. Scale bars: 50 µm in A and B. (C) Relative protein expression of CD16 and CD206 in each group. Lv-shPARP14 injection enhanced the SCI-induced increase in CD16 (M1-type marker) expression and decreased the SCI-induced increase in CD206 (M2-type marker) expression. (D) The concentration of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6) and anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β1, and IL-4) in each group was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Lv-shPARP14 injection increased the concentration of pro-inflammatory cytokines but decreased anti-inflammatory cytokine accumulation. Values are shown as mean ± SD (n = 6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test). Images were taken of the gray matter ventral horn at the injury site. Spinal cord tissues from the injury site were used for western blot and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detection. Arg-1: Arginase-1; DAPI: 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; FITC: fluorescein isothiocyanate; Iba1: ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1; IL: interleukin; iNOS: inducible nitric oxide synthase; PARP14: poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase, member 14; SCI: spinal cord injury; TGF-β1: transforming growth factor-beta1; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor alpha.

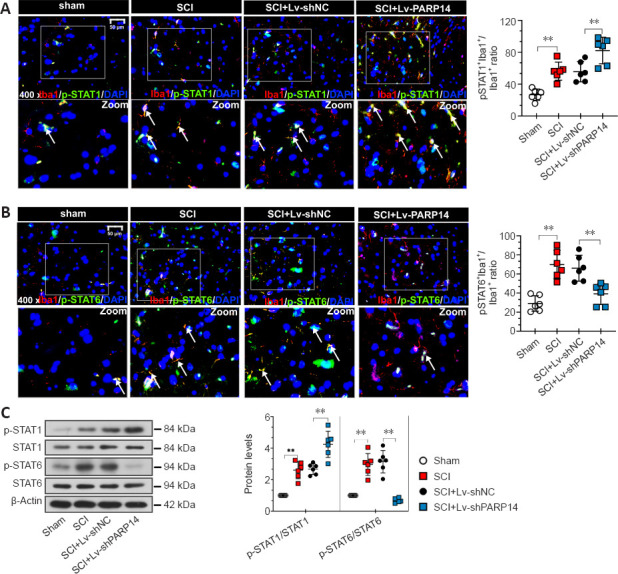

PARP14 deficiency activates the STAT1 pathway but blocks the STAT6 pathway in mice with SCI

The STAT1 pathway mediates M1 microglia/macrophage polarization, and the STAT6 pathway is a key signaling pathway for M2-like polarization of microglia/macrophages (Gan et al., 2017; Li et al., 2021). Therefore, we next analyzed the effects of PARP14 on the STAT1/STAT6 pathway. Double immunofluorescent staining was performed for Iba1 and p-STAT1 (Try701) or p-STAT6 (Tyr641). When PARP14 expression was knocked down, p-STAT1 expression was increased, whereas p-STAT6 was decreased in mice 7 days post-SCI (Figure 5A and B). Consistent with this, p-STAT1 and p-STAT6 protein levels in the spinal cord of mice 7 days post-SCI were increased, while PARP14 inhibition increased p-STAT1 expression but decreased p-STAT6 expression (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

PARP14 deficiency activates the STAT1 pathway but blocks the STAT6 pathway in mice 7 days post-SCI.

(A) Representative images and quantitative analysis showing p-STAT1 (Try701)+/Iba1+ immunofluorescence staining. Lv-shPARP14 injection further promoted SCI-induced STAT1 pathway activation. White arrows indicate p-STAT1 (Try701)+ (green, FITC-labeled)/Iba1+ (red, Cy3-labeled, microglia marker) cells. (B) Representative images and quantitative analysis showing p-STAT6 (Tyr641)+/Iba1+ immunofluorescence staining. Lv-shPARP14 injection inhibited SCI-induced STAT6 pathway activation. White arrows indicated p-STAT6 (Tyr641)+ (green, FITC-labeled)/Iba1+ (red, Cy3-labeled) cells. Scale bars: 50 µm. (C) Relative protein levels of p-STAT1 (Try701), and p-STAT6 (Tyr641) in each group were detected by western blot analysis. p-STAT1 (Try701) expression was increased by Lv-shPARP14 injection, but p-STAT6 (Tyr641) expression was decreased by PARP14 silencing. Values are shown as mean ± SD (n = 6). **P < 0.01 (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test). Images were taken from the gray matter ventral horn at the injury site. Spinal cord tissues from the injury site were used for western blot detection. DAPI: 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole; Iba1: ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1; PARP14: poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase, member 14; SCI: spinal cord injury; STAT1: signal transducer and activator of transcription.

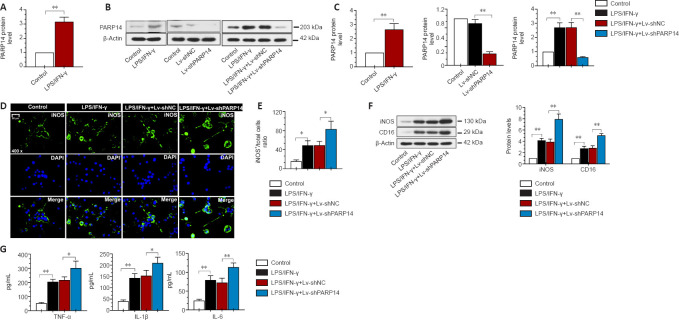

PARP14 deficiency promotes microglia M1 polarization in vitro

To investigate the function of PARP14 in microglia-mediated neuroinflammatory responses, microglia were treated with LPS/IFN-γ to induce M1 polarization. PARP14 mRNA and protein levels were significantly upregulated in microglia in response to stimulation with LPS/IFN-γ (Figure 6A–C). To silence PARP14 expression in microglia stimulated with LPS/IFN-γ, microglia were transfected with Lv-shPARP14 or Lv-shNC, and the transfection efficiency was verified by western blot analysis (Figure 6B and C). Transfection of microglia stimulated with LPS/IFN-γ with Lv-shPARP14 significantly reduced PARP14 expression (Figure 6B and C). Immunofluorescence staining and western blot analysis showed that the expression of an M1 phenotype microglial marker (iNOS) was significantly increased in LPS/IFN-γ-treated microglia, and PARP14 knockdown enhanced this effect (Figure 6D–F). CD16 and iNOS expression levels remained similar in response to various stimuli, as detected by western blot analysis (Figure 6F). In addition, LPS/IFN-γ triggered the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6), whose levels increased further in response to PARP14 silencing (Figure 6G).

Figure 6.

PARP14 deficiency promotes microglia M1 polarization in vitro.

(A) Relative PARP14 mRNA levels in microglia increased in response to LPS/IFN-γ stimulation. (B, C) PARP14 knockdown decreased the LPS/IFN-γ-induced increase in PARP14 protein levels. (D, E) Representative images and quantitative analysis showing iNOS immunofluorescence staining. PARP14 downregulation enhanced the LPS/IFN-γ-induced increase in iNOS (pro-inflammatory phenotype) expression. Green (FITC-labeled) indicates iNOS, and blue indicates nuclei. Scale bar: 50 µm. (F) Relative iNOS and CD16 protein levels in each group. PARP14 silencing further promoted the LPS/IFN-γ-induced increase in iNOS and CD16 expression. (G) Concentration of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6) in all the groups. PARP14 knockdown promoted the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, as determined by ELISA. Values are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test (A, C-left) or one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (C-middle and right, E–G)). DAPI: 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; FITC: fluorescein isothiocyanate; IFN-γ: interferon-gamma; IL: interleukin; iNOS: inducible nitric oxide synthase; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; PARP14: poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase, member 14; SCI: spinal cord injury; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor alpha.

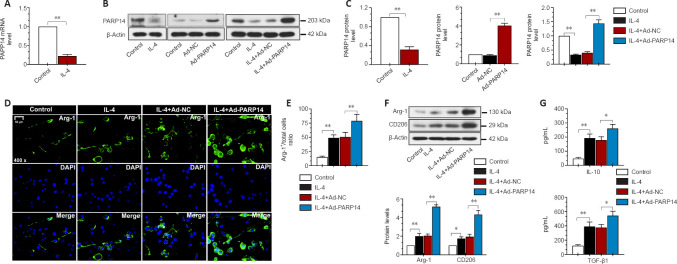

PARP14 overexpression promotes microglia M2 polarization in vitro

Next, we treated microglia with IL-4 to induce M2 polarization. As presented in Figure 7A–C, in response to treatment with IL-4, PARP14 mRNA and protein expression decreased markedly. To induce PARP14 overexpression, microglia were transfected with an adenovirus PARP14 overexpression vector (Ad-PARP14) or its NC (Ad-NC), and the transfection efficiency was verified by western blot analysis (Figure 7B and C). Ad-PARP14 infection significantly increased PARP14 expression in microglia stimulated with IL-4 (Figure 7B and C). The immunofluorescence staining results showed that IL-4 treatment increased Arg-1 expression, and Ad-PARP14 infection further enhanced Arg-1 expression (Figure 7D and E). Western blot analysis showed that M2 phenotype microglial marker (Arg-1 and CD206) protein levels were significantly increased in microglia stimulated with IL-4 and further elevated by PARP14 overexpression (Figure 7F). In addition, treatment with IL-4 increased the accumulation of anti-inflammatory cytokines (TGF-β1 and IL-10), and the levels of these cytokines were further increased by PARP14 overexpression (Figure 7G).

Figure 7.

PARP14 overexpression promotes microglia M2 polarization in vitro.

(A) Relative PARP14 mRNA levels in microglia decreased in response to interleukin (IL)-4 stimulation. (B, C) Transfection with an ad-PARP14 vector reversed the IL-4-induced decrease in PARP14 expression. (D, E) Representative images and quantitative analysis of Arg-1 immunofluorescence staining. PARP14 overexpression enhanced the IL-4-induced increase in Arg-1 (anti-inflammatory phenotype) expression. Green (FITC-labeled) indicates Arg-1, and blue indicates nuclei. Scale bar: 50 µm. (F) Relative protein levels of Arg-1 and CD206 in each group. PARP14 overexpression further promoted the IL-4-induced increase in Arg-1 and CD206 expression. (G) Concentrations of anti-inflammatory cytokines (TGF-β1 and IL-10) in all the groups. PARP14 overexpression promoted the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines. Values are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test analysis, or one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test). Arg-1: Arginase-1; DAPI: 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; FITC: fluorescein isothiocyanate; IL: interleukin; PARP14: poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase, member 14; SCI: spinal cord injury; TGF-β1: transforming growth factor-beta1.

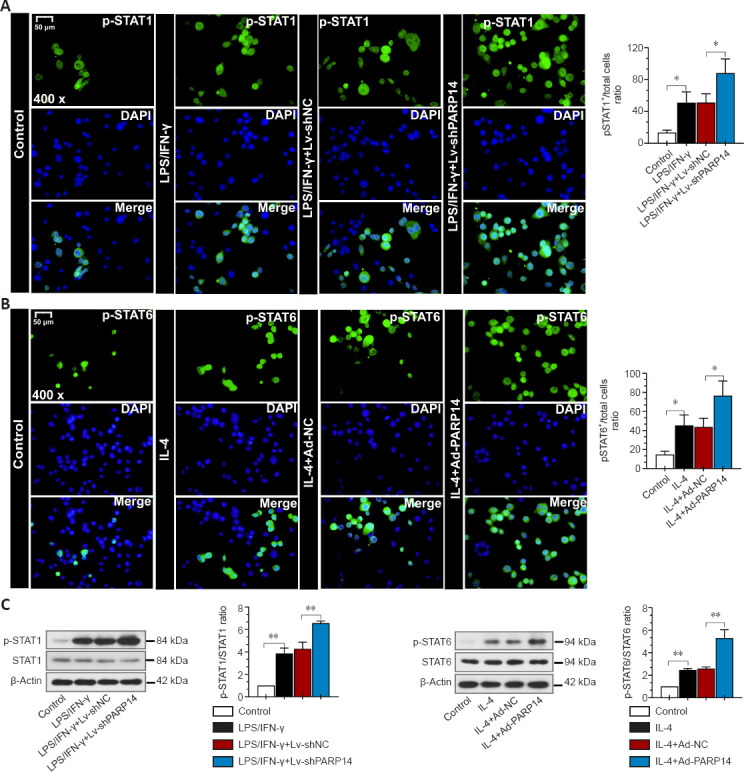

PARP14 regulates microglia M1/M2 polarization through the STAT1/6 pathway in vitro

Next, we investigated the mechanism by which PARP14 regulates the microglia-mediated inflammatory response. As shown in Figure 8A and C, p-STAT1 expression was significantly increased by stimulation with LPS/IFN-γ, and PARP14 knockdown further elevated p-STAT1 expression levels. In addition, treatment with IL-4 significantly increased p-STAT6 expression, and PARP14 overexpression further enhanced this effect (Figure 8B and C).

Figure 8.

PARP14 regulates microglia M1/M2 polarization through the STAT1/6 pathway in vitro.

(A) Representative images and quantitative analysis of p-STAT1 (Try701) immunofluorescence staining. PARP14 silencing further promoted the LPS/IFN-γ-induced increase in p-STAT1 expression. Green (FITC-labeled) indicates p-STAT1, and blue indicates nuclei. (B) Representative images and quantitative analysis of p-STAT6 immunofluorescence staining. PARP14 overexpression further promoted the IL-4-induced increase in p-STAT6 expression. Green (FITC-labeled) indicates p-STAT6, and blue indicates nuclei. Scale bars: 50 µm. (C) Relative protein levels of STAT1, p-STAT1 (Try701), STAT6, and p-STAT6 (Tyr641) in each group. PARP14 knockdown further activated the STAT1 pathway, and PARP14 overexpression further activated the STAT6 pathway. Values are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test). DAPI: 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole; FITC: fluorescein isothiocyanate; IFN-γ: interferon-γ; IL: interleukin; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; PARP14: poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase, member 14; SCI: spinal cord injury; STAT: signal transducer and activator of transcription.

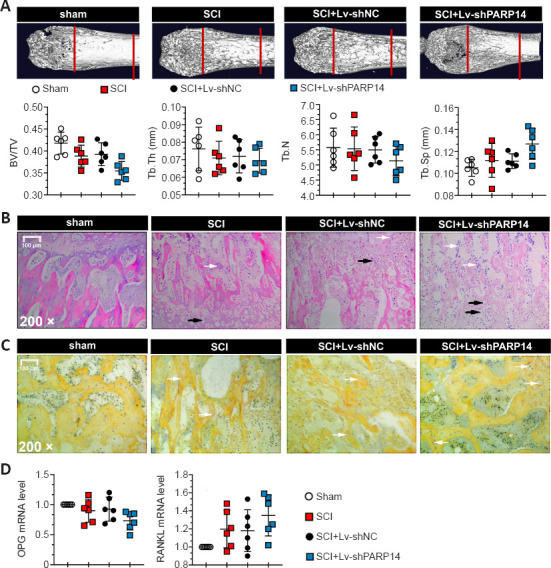

PARP14 deficiency exacerbates SCI-induced bone loss

Rapid bone loss and osteoporosis are closely associated with SCI (Edwards et al., 2018). Therefore, we explored the effects of PARP14 on SCI-induced bone loss 28 days post-SCI. The micro-computed tomography results showed that PARP14 knockdown further decreased trabecular bone volume, trabecular thickness, and trabecular number, and increased trabecular spacing (P > 0.05; Figure 9A). Hematoxylin and eosin staining indicated that PARP14 knockdown increased SCI-induced inflammatory infiltration and the formation osteocyte lacunae, as well as exacerbating disruption of the bone structure (P > 0.05; Figure 9B). The number of osteoclasts identified histochemically by TRAP staining was increased in SCI mice and further increased by PARP14 silencing (P > 0.05; Figure 9C). In addition, PARP14 knockdown increased receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand (RANKL) (osteoclast differentiation marker) mRNA levels but decreased osteoprotegerin (OPG) (osteogenic differentiation marker) mRNA levels (P > 0.05; Figure 9D).

Figure 9.

PARP14 deficiency exacerbates SCI-induced bone loss (28 days post-SCI).

(A) Images of femoral metaphyses. Trabecular bone volume fraction (BV/TV), trabecular number (Tb.N), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), and trabecular spacing (Tb.Sp) were calculated for trabecular bone. Mice with SCI exhibited increased BV/TV, Tb.N, and Tb.Th but decreased Tb.Sp, and PARP14 silencing enhanced these changes (P > 0.05). (B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of femoral metaphyses. PARP14 knockdown increased SCI-induced inflammatory infiltration and osteocyte lacunae and exacerbated disruption of the bone structure. White arrows indicate inflammatory infiltration, and black arrows indicate osteocyte lacunae. Scale bars: 100 µm. (C) TRAP staining of the femoral metaphysis. White arrows indicate TRAP-positive staining (reddish-brown color). (D) Relative mRNA levels of RANKL and osteoprotegerin. Values are shown as mean ± SD (n = 6). Images were taken from the femoral metaphysis. Bone tissues at femoral metaphysis were used for qPCR detection. BV/TV: Trabecular bone volume fraction; PARP14: poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase, member 14; qPCR: quantitative polymerase chain reaction; SCI: spinal cord injury; RANKL: receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand; SCI: spinal cord injury; Tb.N: trabecular number; Tb.Sp: trabecular spacing; Tb.Th: trabecular thickness; TRAP: tartrate-resistant acidic phosphatase.

Discussion

Here, we report for the first time the protective role that PARP14 plays in SCI. We found that PARP14 expression was markedly increased in the injury site in a mouse model of SCI, and that PARP14 knockdown aggravated SCI. In vivo and in vitro experiments indicated that PARP14 inhibits microglia M1 polarization, most likely by blocking the STAT1 pathway, and promotes microglia M2 polarization by activating the STAT6 pathway. Furthermore, we showed that PARP14 silencing promoted SCI-induced bone loss. Taken together, our findings suggest that PARP14 may be a promising therapeutic target for SCI.

In this study, we found that PARP14 is upregulated in SCI as a compensatory mechanism. Similarly, PARP14 plays a protective role in mice with stroke (Tang et al., 2021). These observations suggest that increased PARP14 expression is a self-protective response initiated by the central nervous system in response to traumatic stimuli. In addition to PARP14, many genes perform compensatory functions in SCI. For instance, progranulin (PGRN) expression is increased in the microglia of mice with SCI, and PGRN knockout enhances SCI-induced neuroinflammation (Wang et al., 2019).

Secondary SCI usually occurs within seconds to months after the initial injury and has become an important target for current medical interventions. Inflammation is the main driver of SCI. After the initial injury, large quantities of inflammatory cells infiltrate the damaged and necrotic areas, transforming them into damaged cavities and preventing neuron regeneration (Seki and Fehlings, 2008). Microglia are the most common immune cells in the central nervous system. Upon stimulation, microglia are over-activated, which promotes M1 polarization and the consequent release of inflammatory cytokines, further aggravating the inflammatory response. Microglia/macrophages can reverse their polarization completely from M2 to M1 according to the chemokine environment. Microglia are stimulated by LPS or IFN-γ to adopt the M1 phenotype and express pro-inflammatory cytokines, and IL-4/IL-13 stimulates microglia to adopt the M2 phenotype, which helps resolve inflammation and initiate tissue repair (Orihuela et al., 2016). Our in vivo results indicate that PARP14 promotes microglia M2 polarization but suppresses microglia M1 polarization. Interestingly, SCI also promoted M2 polarization, possible as a self-protective mechanism. Although the anti-inflammatory microglia phenotype was enhanced after SCI, the pronounced inflammatory response that occurs after SCI suggests that the microglia pro-inflammatory phenotype is stronger than the microglia anti-inflammatory phenotype in this context. In addition, PARP14 expression increased after microglia M1 polarization was induced and decreased after microglia M2 polarization was induced, which is consistent with previous results (Iwata et al., 2016) but inconsistent with the known functions of PARP14. One possible explanation for this observation is that, in line with its compensatory effects in vivo, PARP14 was also upregulated after inducing microglia to release adverse pro-inflammatory factors in vitro. Previous studies have demonstrated that the excessive accumulation of M1-type microglia leads to neuroinflammation, and induction microglia M2 polarization alleviates inflammation after SCI (Wang et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2018). These observations suggest that PARP14 plays a protective role in SCI by inducing microglia to undergo polarization to the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype. Similarly, salidroside has been shown to reduce neuroinflammation and improve functional recovery after SCI by inducing microglia M2 polarization (Wang et al., 2018). Inhibition of the high mobility group box 1 receptor for advanced glycation end products axis provided neuroprotection after SCI by inhibiting microglia M1 polarization (Fan et al., 2020). Therefore, the phenotypic transformation of microglia plays an important role in the progress of SCI. Furthermore, our results showed that silencing PARP14 promoted neuronal apoptosis in SCI. The release of inflammatory factors can damage neurons and induce apoptosis. Co-culturing M1-type microglia with neurons has been reported to induce neuronal apoptosis (Wang et al., 2018). Our findings suggest that PARP14 may inhibit neuronal apoptosis by inhibiting microglia M1 polarization, further indicating that the phenotypic transition of microglia may be an effective target for SCI treatment. Additionally, PARP14 has been reported to specifically increase the stability of cyclin D1 mRNA, thereby promoting cycle progression (O’Connor et al., 2021), indicating that PARP14 promotes cell proliferation. Therefore, the inhibitory effect of PARP14 on neuronal loss in the mouse model of SCI used in this study may also involve promotion of neuron survival.

The STAT6 pathway is a key signaling pathway for the M2-like polarization of microglia/macrophages. One study has shown that gefitinib inhibited M2 polarization of tumor-associated macrophages by inhibiting activation of the STAT6 pathway (Tariq et al., 2017). Physalin D activated the STAT6 pathway and enhanced STAT6 nuclear translocation to achieve macrophage M2 polarization (Ding et al., 2019). Our results indicate that PARP14 may induce microglia M2 polarization by activating the STAT6 pathway, thereby exerting an anti-inflammatory effect. PARP14 functions as a transcriptional switch for STAT6-mediated transcription: normally, it acts as a transcriptional repressor by recruiting histone deacetylases, but when stimulated by IL-4, it facilitates STAT6 binding to target gene promoters (Mehrotra et al., 2011). Therefore, we speculate that PARP14 may promote the transcription of STAT6-mediated M2 polarization-related factors by activating the STAT6 pathway.

The STAT1 pathway is a vital regulatory pathway for M1 type polarization of microglia/macrophages. Physalin D suppresses macrophage M1 polarization by inhibiting STAT1 activation and nuclear translocation (Ding et al., 2019). In addition, inhibiting the STAT1 pathway promoted macrophage M2 polarization (Haydar et al., 2019). Studies have also shown that PARP14 can negatively regulate the phosphorylation of downstream genes through glycosylation modification. For example, PARP14-mediated glycosylation of the Glu657 and Glu705 sites of STAT1 inhibited phosphorylation of the Try701 site of STAT1 (Iwata et al., 2016). Phosphorylation at STAT1 Try701 was increased in hypoxia and drove M1 microglia activation and neuroinflammation (Butturini et al., 2019). Therefore, PARP14 may inhibit activation of the STAT1 pathway in SCI through glycosylation of STAT1. Furthermore, Tang et al. (2021) demonstrated that PARP14 inhibits microglial activation by inhibiting LPAR5 transcription. LPAR5 has been reported to be an important regulator of the microglia pro-inflammatory phenotype (Plastira et al., 2017). Therefore, PARP14 may exert its anti-inflammatory effect, at least in part, through the PARP14/LPAR5 axis.

SCI can cause rapid and severe osteoporosis and increase the risk of fractures (Qin et al., 2010; Battaglino et al., 2012). Individuals with SCI often suffer from reduced bone mass and bone integrity, as well as from osteoporosis (Armas and Recker, 2012). In addition, a moderate-severe contusion model of SCI exhibits rapid cancellous bone degeneration and progressive cortical bone loss (Otzel et al., 2019). Significant bone loss is usually observed in moderate-severe and severe SCI models (Otzel et al., 2019; Sahbani et al., 2021; Yarrow et al., 2021). However, in our study, no significant bone loss was observed in SCI mice compared with sham-operated mice, most likely because we only induced a moderate injury. In addition, PARP14 silencing aggravated SCI-induced bone loss, although the difference was not statistically significant. This study clarifies that the PARP14-mediated microglial phenotype switch may promote SCI progression. However, whether PARP14 is involved in SCI progression through other pathways needs further study. Moreover, the results should be confirmed with a larger sample size.

In the present study, we explored the effects of PARP14 on SCI both in vitro and in vivo. We found that PARP14 alleviated neuroinflammation and neuronal apoptosis in a mouse model of SCI, which is possible by inhibiting microglia M1 polarization and promoting microglia M2 polarization. Furthermore, we found that PARP14 suppressed STAT1 activation, thereby inhibiting microglia M1 polarization and activating the STAT6 pathway to induce microglia M2 polarization. In summary, our results suggest that PARP14 may regulate microglia M1/M2 polarization via the STAT1/6 pathway.

Additional files:

Additional Figure 1 (1MB, tif) : Quantified data from the GEO database (GSE5296 and GSE52763).

Quantified data from the GEO database (GSE5296 and GSE52763).

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test). PARP14: Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase, member 14; SCI: spinal cord injury.

Additional Table 1: Primers used for quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Additional Table 2: Antibodies used for Western blot.

Additional file 1: Open peer review report 1 (97.5KB, pdf) .

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by the Shenyang Science and Technology Project, No. 20-205-4-092 (to AHX).

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest.

Availability of data and materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Open peer reviewer: Olivia C Eller, University of Kansas Medical Center, USA.

P-Reviewer: Eller OC; C-Editor: Zhao M; S-Editors: Yu J, Li CH; L-Editors: Crow E, Yu J, Song LP; T-Editor: Jia Y

References

- 1.Amé JC, Spenlehauer C, de Murcia G. The PARP superfamily. Bioessays. (2004);26:882–893. doi: 10.1002/bies.20085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armas LA, Recker RR. Pathophysiology of osteoporosis:new mechanistic insights. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. (2012);41:475–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basso DM, Fisher LC, Anderson AJ, Jakeman LB, McTigue DM, Popovich PG. Basso Mouse Scale for locomotion detects differences in recovery after spinal cord injury in five common mouse strains. J Neurotrauma. (2006);23:635–659. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Battaglino RA, Lazzari AA, Garshick E, Morse LR. Spinal cord injury-induced osteoporosis:pathogenesis and emerging therapies. Curr Osteoporos Rep. (2012);10:278–285. doi: 10.1007/s11914-012-0117-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biering-Sørensen F, Bohr H, Schaadt O. Bone mineral content of the lumbar spine and lower extremities years after spinal cord lesion. Paraplegia. (1988);26:293–301. doi: 10.1038/sc.1988.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butturini E, Boriero D, Carcereri de Prati A, Mariotto S. STAT1 drives M1 microglia activation and neuroinflammation under hypoxia. Arch Biochem Biophys. (2019);669:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2019.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan WM, Mohammed Y, Lee I, Pearse DD. Effect of gender on recovery after spinal cord injury. Transl Stroke Res. (2013);4:447–461. doi: 10.1007/s12975-012-0249-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen M, Gao YT, Li WX, Wang JC, He YP, Li ZW, Gan GS, Yuan B. FBW7 protects against spinal cord injury by mitigating inflammation-associated neuronal apoptosis in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2020);532:576–583. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dauty M, Perrouin Verbe B, Maugars Y, Dubois C, Mathe JF. Supralesional and sublesional bone mineral density in spinal cord-injured patients. Bone. (2000);27:305–309. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00326-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.David S, Kroner A. Repertoire of microglial and macrophage responses after spinal cord injury. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2011);12:388–399. doi: 10.1038/nrn3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding N, Wang Y, Dou C, Liu F, Guan G, Wei K, Yang J, Yang M, Tan J, Zeng W, Zhu C. Physalin D regulates macrophage M1/M2 polarization via the STAT1/6 pathway. J Cell Physiol. (2019);234:8788–8796. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards WB, Simonian N, Haider IT, Anschel AS, Chen D, Gordon KE, Gregory EK, Kim KH, Parachuri R, Troy KL, Schnitzer TJ. Effects of teriparatide and vibration on bone mass and bone strength in people with bone loss and spinal cord injury:a randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res. (2018);33:1729–1740. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engesser-Cesar C, Anderson AJ, Basso DM, Edgerton VR, Cotman CW. Voluntary wheel running improves recovery from a moderate spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. (2005);22:157–171. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan H, Tang HB, Chen Z, Wang HQ, Zhang L, Jiang Y, Li T, Yang CF, Wang XY, Li X, Wu SX, Zhang GL. Inhibiting HMGB1-RAGE axis prevents pro-inflammatory macrophages/microglia polarization and affords neuroprotection after spinal cord injury. J Neuroinflammation. (2020);17:295. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-01973-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3:a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. (2007);39:175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furlan JC, Krassioukov AV, Fehlings MG. The effects of gender on clinical and neurological outcomes after acute cervical spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. (2005);22:368–381. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gan ZS, Wang QQ, Li JH, Wang XL, Wang YZ, Du HH. Iron reduces M1 macrophage polarization in RAW264.7 macrophages associated with inhibition of STAT1. Mediators Inflamm. (2017);2017:8570818. doi: 10.1155/2017/8570818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaviria M, Haton H, Sandillon F, Privat A. A mouse model of acute ischemic spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. (2002);19:205–221. doi: 10.1089/08977150252806965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gualerzi A, Lombardi M, Verderio C. Microglia-oligodendrocyte intercellular communication:role of extracellular vesicle lipids in functional signalling. Neural Regen Res. (2021);16:1194–1195. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.300430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han D, Yu Z, Liu W, Yin D, Pu Y, Feng J, Yuan Y, Huang A, Cao L, He C. Plasma Hemopexin ameliorates murine spinal cord injury by switching microglia from the M1 state to the M2 state. Cell Death Dis. (2018);9:181. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0236-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haydar D, Cory TJ, Birket SE, Murphy BS, Pennypacker KR, Sinai AP, Feola DJ. Azithromycin polarizes macrophages to an M2 phenotype via inhibition of the STAT1 and NF-κB signaling pathways. J Immunol. (2019);203:1021–1030. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1801228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He Z, Zou S, Yin J, Gao Z, Liu Y, Wu Y, He H, Zhou Y, Wang Q, Li J, Wu F, Xu HZ, Jia X, Xiao J. Inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress preserves the integrity of blood-spinal cord barrier in diabetic rats subjected to spinal cord injury. Sci Rep. (2017);7:7661. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08052-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwata H, Goettsch C, Sharma A, Ricchiuto P, Goh WW, Halu A, Yamada I, Yoshida H, Hara T, Wei M, Inoue N, Fukuda D, Mojcher A, Mattson PC, Barabási AL, Boothby M, Aikawa E, Singh SA, Aikawa M. PARP9 and PARP14 cross-regulate macrophage activation via STAT1 ADP-ribosylation. Nat Commun. (2016);7:12849. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang W, Li M, He F, Zhou S, Zhu L. Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome to attenuate spinal cord injury in mice. J Neuroinflammation. (2017);14:207. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0980-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khayrullina G, Bermudez S, Byrnes KR. Inhibition of NOX2 reduces locomotor impairment, inflammation, and oxidative stress after spinal cord injury. J Neuroinflammation. (2015);12:172. doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0391-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobashi S, Terashima T, Katagi M, Nakae Y, Okano J, Suzuki Y, Urushitani M, Kojima H. Transplantation of M2-deviated microglia promotes recovery of motor function after spinal cord injury in mice. Mol Ther. (2020);28:254–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JY, Choi HY, Ju BG, Yune TY. Estrogen alleviates neuropathic pain induced after spinal cord injury by inhibiting microglia and astrocyte activation. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. (2018);1864:2472–2480. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li HT, Zhao XZ, Zhang XR, Li G, Jia ZQ, Sun P, Wang JQ, Fan ZK, Lv G. Exendin-4 enhances motor function recovery via promotion of autophagy and inhibition of neuronal apoptosis after spinal cord injury in rats. Mol Neurobiol. (2016);53:4073–4082. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9327-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, Sheng Q, Zhang C, Han C, Bai H, Lai P, Fan Y, Ding Y, Dou X. STAT6 up-regulation amplifies M2 macrophage anti-inflammatory capacity through mesenchymal stem cells. Int Immunopharmacol. (2021);91:107266. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lisi L, Ciotti GM, Braun D, Kalinin S, Currò D, Dello Russo C, Coli A, Mangiola A, Anile C, Feinstein DL, Navarra P. Expression of iNOS, CD163, and ARG-1 taken as M1 and M2 markers of microglial polarization in human glioblastoma and the surrounding normal parenchyma. Neurosci Lett. (2017);645:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.02.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. (2001);25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu Y, Zhou M, Li Y, Li Y, Hua Y, Fan Y. Minocycline promotes functional recovery in ischemic stroke by modulating microglia polarization through STAT1/STAT6 pathways. Biochem Pharmacol. (2021);186:114464. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2021.114464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McDonald JW, Sadowsky C. Spinal-cord injury. Lancet. (2002);359:417–425. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07603-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mehrotra P, Riley JP, Patel R, Li F, Voss L, Goenka S. PARP-14 functions as a transcriptional switch for Stat6-dependent gene activation. J Biol Chem. (2011);286:1767–1776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.157768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mills CD, Kincaid K, Alt JM, Heilman MJ, Hill AM. M-1/M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. J Immunol. (2000);164:6166–6173. [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Eighth Edition. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Connor MJ, Thakar T, Nicolae CM, Moldovan GL. PARP14 regulates cyclin D1 expression to promote cell-cycle progression. Oncogene. (2021);40:4872–4883. doi: 10.1038/s41388-021-01881-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orihuela R, McPherson CA, Harry GJ. Microglial M1/M2 polarization and metabolic states. Br J Pharmacol. (2016);173:649–665. doi: 10.1111/bph.13139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Otzel DM, Conover CF, Ye F, Phillips EG, Bassett T, Wnek RD, Flores M, Catter A, Ghosh P, Balaez A, Petusevsky J, Chen C, Gao Y, Zhang Y, Jiron JM, Bose PK, Borst SE, Wronski TJ, Aguirre JI, Yarrow JF. Longitudinal examination of bone loss in male rats after moderate-severe contusion spinal cord injury. Calcif Tissue Int. (2019);104:79–91. doi: 10.1007/s00223-018-0471-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel M, Li Y, Anderson J, Castro-Pedrido S, Skinner R, Lei S, Finkel Z, Rodriguez B, Esteban F, Lee KB, Lyu YL, Cai L. Gsx1 promotes locomotor functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Mol Ther. (2021);29:2469–2482. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Plastira I, Bernhart E, Goeritzer M, DeVaney T, Reicher H, Hammer A, Lohberger B, Wintersperger A, Zucol B, Graier WF, Kratky D, Malle E, Sattler W. Lysophosphatidic acid via LPA-receptor 5/protein kinase D-dependent pathways induces a motile and pro-inflammatory microglial phenotype. J Neuroinflammation. (2017);14:253. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-1024-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plate JDJ, Borggreve AS, van Hillegersberg R, Peelen LM. Post hoc power calculation:observing the expected. Ann Surg. (2019);269:e11. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poulen G, Aloy E, Bringuier CM, Mestre-Francés N, Artus EVF, Cardoso M, Perez JC, Goze-Bac C, Boukhaddaoui H, Lonjon N, Gerber YN, Perrin FE. Inhibiting microglia proliferation after spinal cord injury improves recovery in mice and nonhuman primates. Theranostics. (2021);11:8640–8659. doi: 10.7150/thno.61833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qin W, Bauman WA, Cardozo C. Bone and muscle loss after spinal cord injury:organ interactions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2010);1211:66–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sahbani K, Shultz LC, Cardozo CP, Bauman WA, Tawfeek HA. Absence of αβT cells accelerates disuse bone loss in male mice after spinal cord injury. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2021);1487:43–55. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seki T, Fehlings MG. Mechanistic insights into posttraumatic syringomyelia based on a novel in vivo animal model. Laboratory investigation. J Neurosurg Spine. (2008);8:365–375. doi: 10.3171/SPI/2008/8/4/365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shams R, Drasites KP, Zaman V, Matzelle D, Shields DC, Garner DP, Sole CJ, Haque A, Banik NL. The pathophysiology of osteoporosis after spinal cord injury. Int J Mol Sci. (2021);22:3057. doi: 10.3390/ijms22063057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tang Y, Liu J, Wang Y, Yang L, Han B, Zhang Y, Bai Y, Shen L, Li M, Jiang T, Ye Q, Yu X, Huang R, Zhang Z, Xu Y, Yao H. PARP14 inhibits microglial activation via LPAR5 to promote post-stroke functional recovery. Autophagy. (2021);17:2905–2922. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2020.1847799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tariq M, Zhang JQ, Liang GK, He QJ, Ding L, Yang B. Gefitinib inhibits M2-like polarization of tumor-associated macrophages in Lewis lung cancer by targeting the STAT6 signaling pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin. (2017);38:1501–1511. doi: 10.1038/aps.2017.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vyas S, Matic I, Uchima L, Rood J, Zaja R, Hay RT, Ahel I, Chang P. Family-wide analysis of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity. Nat Commun. (2014);5:4426. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang C, Zhang L, Ndong JC, Hettinghouse A, Sun G, Chen C, Zhang C, Liu R, Liu CJ. Progranulin deficiency exacerbates spinal cord injury by promoting neuroinflammation and cell apoptosis in mice. J Neuroinflammation. (2019);16:238. doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1630-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang C, Wang Q, Lou Y, Xu J, Feng Z, Chen Y, Tang Q, Zheng G, Zhang Z, Wu Y, Tian N, Zhou Y, Xu H, Zhang X. Salidroside attenuates neuroinflammation and improves functional recovery after spinal cord injury through microglia polarization regulation. J Cell Mol Med. (2018);22:1148–1166. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu H, Zheng J, Xu S, Fang Y, Wu Y, Zeng J, Shao A, Shi L, Lu J, Mei S, Wang X, Guo X, Wang Y, Zhao Z, Zhang J. Mer regulates microglial/macrophage M1/M2 polarization and alleviates neuroinflammation following traumatic brain injury. J Neuroinflammation. (2021);18:2. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-02041-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu S, Zhu W, Shao M, Zhang F, Guo J, Xu H, Jiang J, Ma X, Xia X, Zhi X, Zhou P, Lu F. Ecto-5'-nucleotidase (CD73) attenuates inflammation after spinal cord injury by promoting macrophages/microglia M2 polarization in mice. J Neuroinflammation. (2018);15:155. doi: 10.1186/s12974-018-1183-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yarrow JF, Wnek RD, Conover CF, Reynolds MC, Buckley KH, Kura JR, Sutor TW, Otzel DM, Mattingly AJ, Croft S, Aguirre JI, Borst SE, Beck DT, McCullough DJ. Bone loss after severe spinal cord injury coincides with reduced bone formation and precedes bone blood flow deficits. J Appl Physiol (1985) (2021);131:1288–1299. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00444.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zehnder Y, Lüthi M, Michel D, Knecht H, Perrelet R, Neto I, Kraenzlin M, Zäch G, Lippuner K. Long-term changes in bone metabolism, bone mineral density, quantitative ultrasound parameters, and fracture incidence after spinal cord injury:a cross-sectional observational study in 100 paraplegic men. Osteoporos Int. (2004);15:180–189. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1529-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zeng H, Liu N, Yang YY, Xing HY, Liu XX, Li F, La GY, Huang MJ, Zhou MW. Lentivirus-mediated downregulation of α-synuclein reduces neuroinflammation and promotes functional recovery in rats with spinal cord injury. J Neuroinflammation. (2019);16:283. doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1658-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Quantified data from the GEO database (GSE5296 and GSE52763).

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test). PARP14: Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase, member 14; SCI: spinal cord injury.