Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most prevalent malignant liver neoplasm. Despite the advances in diagnosis and treatment, the prognosis of HCC patients remains poor. Cytoskeleton‐associated membrane protein 4 (CKAP4) is a receptor of the glycosylated secretory protein Dickkopf‐1 (DKK1), and the DKK1‐CKAP4 axis is activated in pancreatic, lung, and esophageal cancer cells. Expression of DKK1 and CKAP4 has been examined in HCC in independent studies that yielded contradictory results. In this study, the relationship between the DKK1‐CKAP4 axis and HCC was comprehensively examined. In 412 HCC cases, patients whose tumors were positive for both DKK1 and CKAP4 had a poor prognosis compared to those who were positive for only one of these markers or negative for both. Deletion of either DKK1 or CKAP4 inhibited HCC cell growth. In contrast to WT DKK1, DKK1 lacking the CKAP4 binding region did not rescue the phenotypes caused by DKK1 depletion, suggesting that binding of DKK1 to CKAP4 is required for HCC cell proliferation. Anti‐CKAP4 Ab inhibited HCC growth, and its antitumor effect was clearly enhanced when combined with lenvatinib, a multikinase inhibitor. These results indicate that simultaneous expression of DKK1 and CKAP4 is involved in the aggressiveness of HCC, and that the combination of anti‐CKAP4 Ab and other therapeutics including lenvatinib could represent a promising strategy for treating advanced HCC.

Keywords: CKAP4, combination drug therapy, DKK1, HCC, lenvatinib

In hepatocellular carcinoma, the DKK1‐CKAP4 signaling axis promotes cancer growth and tumorigenesis. Combination with anti‐CKAP4 Abs enhances the antitumor effects of the existing molecularly targeted agent lenvatinib.

Abbreviations

- CKAP4

cytoskeleton‐associated protein 4

- CRD

cysteine‐rich domain

- DKK1

Dickkopf‐1

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- FGFR

fibroblast growth factor receptor

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- RTK

receptor tyrosine kinase

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

1. INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma is the fifth most common type of cancer worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer‐related death. 1 Hepatocellular carcinoma usually results from the progressive accumulation of genetic and epigenetic alterations that are associated with various etiologies, including hepatitis B and C, alcohol consumption, and obesity, and is a complex multistep biological process. 2 , 3 Recent advances in our understanding of the molecular pathology of HCC have led to patients being treated with novel therapeutic options combined with modern surgical resections, including ultrasonography‐guided puncture, per‐catheter intervention, and molecular‐targeted chemotherapy. 4 , 5

For a long time, sorafenib monotherapy was the only treatment strategy for advanced HCC with extrahepatic disease, 6 , 7 but it improved overall survival of patients by only a few months and often severe adverse effects were observed. 8 , 9 Recently, novel therapies including atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and lenvatinib improved clinical outcome of unresectable HCC cases. 10 However, their efficacy is still limited, 11 and a variety of side‐effects sometimes prevent adequate treatment, so novel therapeutic agents in combination with these drugs to enhance antitumor effects are required.

Dickkopf‐1 is a secretory antagonist of the Wnt signaling pathway. 12 , 13 There are conflicting reports on the effects of DKK1 on tumorigenesis regarding its oncogenic or tumor suppressive activities; these opposing effects might depend on the cell type and underlying genetic components. 13 , 14 It is likely that DKK1 acts as a proto‐oncogene in HCC, except for a few examples (e.g., M‐H7402 and PLC/PRF/5 cells). 15 , 16 Indeed, DKK1 is highly expressed in HCC and involved in HCC aggressiveness. 17 , 18 , 19 Thus, it represents a promising biomarker and molecular target for HCC. However, the mechanism of action of DKK1 in HCC and its intervention approach have not been established.

Cytoskeleton‐associated protein 4 (also known as CLIMP‐63 and ERGIC‐63) was originally identified as a type II transmembrane protein primarily located in the ER involved in its structural maintenance. 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 It was reported that CKAP4 is localized to the plasma membrane and functions as a receptor for DKK1. 24 Dickkopf‐1 activates the PI3K‐AKT pathway by binding CKAP4, thereby stimulating cell proliferation. 13 , 24 Simultaneous expression of DKK1 and CKAP4 is associated with poor prognosis in pancreatic, lung, and esophageal cancer. 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 Anti‐CKAP4 Ab inhibited tumor formation in xenograft models of these cancers. 30 Thus, CKAP4 could represent a molecular target for treating these cancers. Dataset analysis suggested that CKAP4 mRNA is upregulated in HCC tumors compared to normal adjacent tissues, and its expression levels are associated with poor clinical prognosis. 31 However, reports contradicting these findings have been published. For example, HCC patients with high CKAP4 expression had favorable overall survival and longer disease‐free survival than those with low expression. 32 High CKAP4 expression in HCC cells was associated with low proliferation and invasion potential through the inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. 33

To understand the relationship between the DKK1‐CKAP4 axis and HCC, it is necessary to examine the expression and function of both proteins in HCC. In this study, we comprehensively evaluated the DKK1 and CKAP4 expression levels in 412 HCC patients and found that those positive for both DKK1 and CKAP4 had a worse prognosis than those expressing only one of the markers or neither marker. In addition, we showed that both DKK1 and CKAP4 were required for the proliferation of DKK1‐overexpressing HCC cells where CKAP4 was localized to the plasma membrane. The combination of an anti‐CKAP4 Ab and lenvatinib showed additive inhibition of AKT signaling and antitumor effects. Thus, the simultaneous expression of DKK1 and CKAP4, a ligand and a receptor, plays a critical role in cancer aggressiveness, and CKAP4 represents a new therapeutic target for HCC therapy.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Patients and cancer tissues

Hepatocellular carcinoma patients (n = 412) who underwent surgery at Kobe University Hospital from January 2000 to December 2016 were examined in this study. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Patients with distant metastases were excluded. Tumors were staged according to the UICC TNM staging system, 8th edition. Resected specimens were macroscopically examined to determine the location and size of tumors. Histological specimens were fixed in 10% (v/v) formalin and embedded in paraffin.

2.2. Dickkopf‐1 and CKAP4 immunohistochemical staining in HCC tissues

Tissue microarrays of formalin‐fixed, paraffin‐embedded tumor tissue were constructed for immunohistochemistry. Three tissue cores (2 mm in diameter) were randomly taken from each case. Immunostaining was performed on a Ventana Benchmark XT (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's protocols. Deparaffinized sections were heat‐treated and incubated with a primary Ab for DKK1 or CKAP4. Immunohistochemical staining was carried out as described previously. 24 , 34 Tumors were considered DKK1‐ or CKAP4‐positive when the stained area was ≥20% of the total tumor lesion. The cut‐off was determined so that the cases positive for DKK1 and CKAP4 are most significantly divided from other cases (the cases positive for either DKK1 or CKAP4 and the cases negative for both) in respect of overall survival after operation. Three investigators assessed the sections independently in a blinded fashion. Although it is hard to detect DKK1 or CKAP4 localization on the plasma membrane immunohistochemically, ELISA is available to detect those released from cancer cells. 27

2.3. Tumor formation assay in vivo

The xenograft tumor formation assay was undertaken as previously described 24 , 34 , 35 with modification. BALB/cAJcl‐nu/nu mice (8‐week‐old male nude mice; CLEA Japan) were inoculated subcutaneously in the dorsal flank with Hep3B, Hep3B/shDKK1, or Hep3B/shCKAP4 cells (5 × 106 cells) resuspended in 150 μl Matrigel.

To examine the antitumor effects of the anti‐CKAP4 mAb, lenvatinib, or their combination, the mice were randomly divided into two or four groups 2 days after inoculation. Anti‐CKAP4 Ab or IgG (250 μg) was administered intravenously three times per week. Lenvatinib (1 mg/kg) was administered orally six times per week. Tumors that were not viable at 19 days after inoculation were excluded from further experiments. The mice were killed 21–28 days after inoculation. Tumor volumes were calculated using the formula: (major axis) × (minor axis) × (minor axis) × 0.5. 36 No blinding was used for the animal experiments.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Student's t‐test or the Mann–Whitney U‐test was used to determine statistical differences between the means of two groups. Analysis of variance with Dunnett's post‐hoc test was used to compare the means of three or more groups. The generalized Wilcoxon test was used to determine statistical differences between survival curves; p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software) or JMP software (SAS Institute Inc.).

Multivariate analysis was undertaken using covariates with p < 0.1 in the univariate analysis, and covariates were excluded to avoid multicollinearity. The UICC stage was considered as a covariate parameter of tumor factors, therefore it was excluded from multivariate analysis. Lymph node metastasis was excluded from multivariate analysis because of the small number of events.

The normalized dose–response curves of lenvatinib were analyzed by nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism 9. A four‐parameter logistic model was fitted to the dataset. Curves were statistically compared using an extra sum‐of‐squares F test with logIC50 as a parameter.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Simultaneous expression of DKK1 and CKAP4 is associated with poor prognosis in HCC

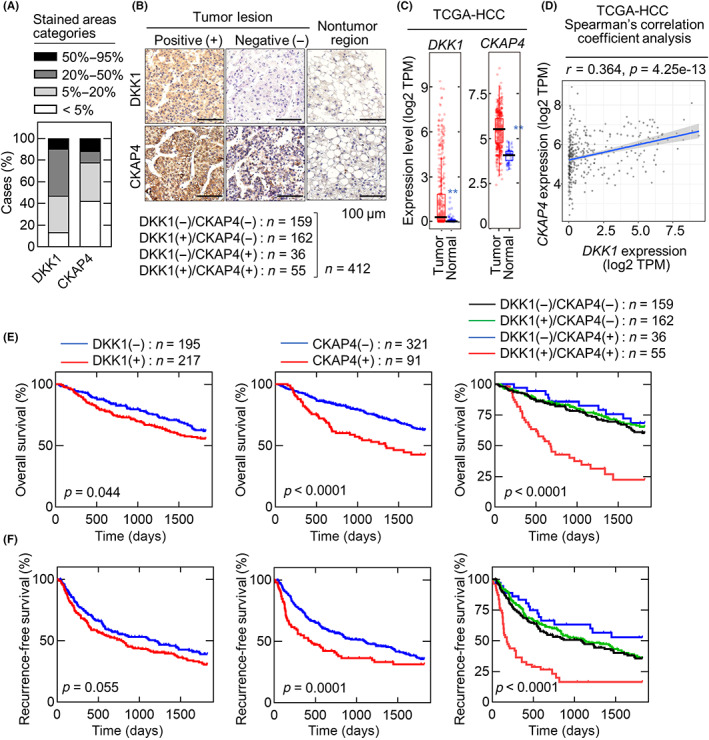

A tissue microarray of 412 HCC cases was generated, and serial sections of each specimen were immunostained with anti‐DKK1 and anti‐CKAP4 Abs. The stained areas were classified into four categories (<5%, 5%–20%, 20%–50%, and 50%–95%; Figure 1A), and the results were considered DKK1‐ or CKAP4‐positive when the stained area showed ≥20% of the total tumor lesion. There were 217 (52.7%) DKK1‐positive and 91 (22.1%) CKAP4‐positive cases (Figure 1B), whereas both proteins were minimally expressed in nontumor regions. The 412 cases were classified into four groups based on the DKK1 and CKAP4 staining profiles: 159 cases were (38.6%) negative for both markers; 162 cases (39.3%) were positive for DKK1 only; 36 cases were (8.7%) positive for CKAP4 only; 55 cases (13.3%) were positive for both DKK1 and CKAP4 (Figure 1B). Expression levels of DKK1 and CKAP4 in HCC were further analyzed using cohorts from the TCGA dataset. The mRNA levels of both genes were significantly higher in the tumors compared to the nontumor regions (Figure 1C). Furthermore, the TCGA datasets revealed a significant positive correlation between DKK1 and CKAP4 mRNA expression in HCC (Figure 1D).

FIGURE 1.

Dickkopf‐1 (DKK1) and cytoskeleton‐associated protein 4 (CKAP4) are expressed in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). (A) Staining areas of DKK1 and CKAP4 in HCC tissues were classified into four categories (<5%, 5%–20%, 20%–50%, and 50%–95%) and the percentages of categories are shown. (B) HCC tissue microarray (n = 412) was stained with anti‐DKK1 or anti‐CKAP4 Ab and hematoxylin. Scale bar, 100 μm. The number of DKK1‐ and CKAP4‐positive cases and the percentage of each subgroup are shown below. (C) In The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset, DKK1 (left panel) and CKAP4 (right panel) expression levels in the HCC tumor lesions (n = 371) and adjacent normal tissue (n = 50) were obtained from TIMER2.0. In the box plot, the median is represented by a black line, the 25th–75th percentile by a box, and the 5th–95th percentile by the error bar. **p < 0.01 (Wilcoxon's test). (D) Scatter plot shows the correlation between DKK1 (X‐axis) and CKAP4 (Y‐axis) mRNA expression obtained from the TCGA dataset (n = 371) using TIMER2.0. The solid blue line indicates the linear fit; r indicates Spearman's r correlation coefficient, and e is the base of the natural logarithm. (E, F) Relationships between overall survival (E) or recurrence‐free survival (F) and DKK1 and CKAP4 expression in HCC patients were analyzed. The Gehan–Breslow–Wilcoxon test was used for statistical analysis.

Clinicopathological examination of the 412 HCC cases revealed that the cases positive for both DKK1 and CKAP4 were significantly associated with vascular invasion compared to the cases negative for both or positive for either (Table 1). The cases positive for both were significantly associated with advanced UICC stage (≥IIIA) and extrahepatic recurrence, especially in the lung, compared to the cases that were negative for both or positive for DKK1 only (Table 1). The cases positive for both markers were also significantly associated with multiple tumors (≥2) and larger tumor size (≥5 cm) compared to the cases positive for DKK1 only (Table 1). Compared to cases negative for both markers, those positive for CKAP4 only and those positive for both were significantly associated with impaired liver function (Child–Pugh class B; Tables 1 and S1).

TABLE 1.

Relationships between simultaneous Dickkopf‐1 (DKK1) and cytoskeleton‐associated protein 4 (CKAP4) expression and clinicopathological factors in hepatocellular carcinoma cases

| Parameters | DKK1+/CKAP4+ (n = 55) | DKK1−/CKAP4− (n = 159) | p value | DKK1+/CKAP4− (n = 162) | p value | DKK1−/CKAP4+ (n = 36) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General background | |||||||

| Age (years) | 68 (41–80) | 69 (34–88) | 0.267 | 69 (33–87) | 0.545 | 71 (50–80) | 0.329 |

| Sex (male/female) | 47/8 | 134/25 | 0.834 | 138/24 | 0.961 | 32/4 | 0.636 |

| Hepatitis virus infection (non‐B non‐C/HB, HC) | 22/33 | 66/93 | 0.844 | 57/105 | 0.523 | 15/21 | 0.874 |

| Child–Pugh class (A/B) | 50/5 | 158/1 | 0.001 | 156/6 | 0.116 | 34/2 | 0.536 |

| Tumor factor | |||||||

| Tumor number (>2/1) | 26/29 | 53/106 | 0.067 | 43/119 | 0.005 | 12/24 | 0.185 |

| Tumor size (≥5 cm/<5 cm) | 30/25 | 65/94 | 0.079 | 63/99 | 0.043 | 18/18 | 0.671 |

| Histology (poor/well or moderate) | 13/42 | 20/139 | 0.059 | 20/142 | 0.053 | 8/28 | 0.875 |

| Lymph node metastasis (positive/negative) | 2/53 | 1/158 | 0.102 | 1/161 | 0.098 | 0/36 | 0.247 |

| Vascular invasion (positive/negative) | 32/23 | 56/103 | 0.003 | 54/108 | 0.001 | 13/23 | 0.039 |

| Capsular formation (positive/negative) | 45/10 | 137/21 | 0.385 | 138/23 | 0.495 | 31/5 | 0.589 |

| Capsular invasion (positive/negative) | 38/17 | 112/46 | 0.802 | 110/48 | 0.942 | 24/12 | 0.809 |

| UICC stage (IIIA–IVA/ IA–II) | 26/29 | 40/119 | 0.003 | 35/127 | 0.0004 | 12/24 | 0.185 |

| Intrahepatic recurrence (positive/negative) | 33/22 | 83/76 | 0.316 | 89/73 | 0.512 | 16/20 | 0.145 |

| Extrahepatic recurrence (positive/negative) | 14/41 | 14/145 | 0.003 | 12/150 | 0.001 | 6/30 | 0.316 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 2 | 2 | 0.294 | 3 | 0.446 | 2 | 0.662 |

| Lung metastasis | 9 | 8 | 0.012 | 3 | <0.0001 | 3 | 0.268 |

| Bone metastasis | 4 | 4 | 0.133 | 6 | 0.275 | 1 | 0.358 |

Note: Continuous variables are expressed as medians with ranges. p values were calculated by comparing between double positive cases and each other cases. p values ≤0.05 are statistically significant.

Abbreviations: HB, hepatitis B; HC, hepatitis C; non‐B non‐C, non‐hepatitis B and non‐hepatitis C.

Five‐year overall survival was significantly reduced in patients who were DKK1‐positive or CKAP4‐positive, and 5‐year recurrence‐free survival was significantly reduced in patients who were CKAP4‐positive compared to their negative counterparts (Figure 1E,F). Notably, patients who were positive for both DKK1 and CKAP4 had significantly lower 5‐year overall survival and disease‐free survival compared to those who were positive for either or negative for both markers. There were no significant differences in 5‐year overall survival or 5‐year recurrence‐free survival between patients positive only for DKK1 or CKAP4 and those who were negative for both (Figure 1E,F).

The univariate analysis indicated that simultaneous expression of DKK1 and CKAP4 was associated with inferior 5‐year overall survival (hazard ratio = 3.39–4.64), tumor number ≥2, tumor size ≥5 cm, positive lymph node metastasis and vascular invasion, and advanced UICC stage (≥IIIA; Table 2). The multivariate analysis also indicated that the expression of both DKK1 and CKAP4 was an independent prognostic factor for 5‐year overall survival, in addition to age ≥60 years, tumor number ≥2, tumor size ≥5 cm, and vascular invasion (Table 3). Similar results were observed for relapse‐free survival (Tables 4 and 5). These analyses clearly indicate that simultaneous expression of DKK1 and CKAP4 increases HCC aggressiveness.

TABLE 2.

Univariate analysis of 5‐year overall survival of hepatocellular carcinoma cases by Cox proportional hazards model

| Parameters | Number | HR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General background | ||||

| Age (≥60 years/<60 years) | 351/61 | 1.57 | 0.99–2.48 | 0.055 |

| Sex (male/female) | 351/61 | 0.75 | 0.50–1.13 | 0.172 |

| Hepatitis virus infection (HB, HC/non‐B non‐C) | 160/252 | 1.11 | 0.80–1.52 | 0.542 |

| Child–Pugh classification (B/A) | 14/398 | 1.39 | 0.65–2.96 | 0.397 |

| Tumor factor | ||||

| Tumor number (>2/1) | 134/278 | 2.24 | 1.65–3.04 | <0.0001 |

| Tumor size (≥5 cm/<5 cm) | 176/236 | 1.97 | 1.45–2.67 | <0.0001 |

| Histology (poor/well or moderate) | 61/351 | 1.23 | 0.81–1.85 | 0.329 |

| Lymph node metastasis (positive/negative) | 4/408 | 10.41 | 3.76–28.79 | <0.0001 |

| Vascular invasion (positive/negative) | 155/257 | 2.24 | 1.65–3.03 | <0.0001 |

| Capsular formation (positive/negative) | 351/59 | 0.85 | 0.56–1.28 | 0.430 |

| Capsular invasion (positive/negative) | 284/123 | 1.02 | 0.73–1.43 | 0.893 |

| UICC stage (IIIA–IVA/IA–II) | 113/299 | 2.51 | 1.84–3.44 | <0.0001 |

| DKK1/CKAP4 expression | ||||

| DKK1+/CKAP4+ vs. DKK1 − CKAP4− | 55/159 | 3.39 | 2.21–5.20 | <0.0001 |

| DKK1+/CKAP4+ vs. DKK1 + CKAP4− | 55/162 | 3.94 | 2.54–6.11 | <0.0001 |

| DKK1+/CKAP4+ vs. DKK1−CKAP4+ | 55/36 | 4.64 | 2.29–9.40 | <0.0001 |

Note: p values ≤0.05 are statistically significant.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CKAP4, cytoskeleton‐associated protein 4; DKK1, Dickkopf‐1; HB, hepatitis B; HC, hepatitis C; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; non‐B non‐C, non‐hepatitis B and non‐hepatitis C; HR, hazard ratio.

TABLE 3.

Multivariate analysis of 5‐year overall survival of hepatocellular carcinoma cases by Cox proportional hazards model

| Parameters | Number | HR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General background | ||||

| Age (≥60 years/<60 years) | 351/61 | 2.35 | 1.33–4.17 | 0.003 |

| Tumor factor | ||||

| Tumor number (>2/1) | 134/278 | 1.97 | 1.42–2.73 | <0.0001 |

| Tumor size (≥5 cm/<5 cm) | 176/236 | 1.68 | 1.18–2.38 | 0.004 |

| Vascular invasion (positive/negative) | 155/257 | 1.69 | 1.18–2.40 | 0.004 |

| DKK1/CKAP4 expression | ||||

| DKK1+/CKAP4+ vs. DKK1 − CKAP4− | 55/159 | 2.89 | 1.87–4.48 | <0.0001 |

| DKK1+/CKAP4+ vs. DKK1 + CKAP4− | 55/162 | 3.31 | 2.11–5.17 | <0.0001 |

| DKK1+/CKAP4+ vs. DKK1 − CKAP4+ | 55/36 | 4.19 | 2.06–8.54 | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CKAP4, cytoskeleton‐associated protein 4; DKK1, Dickkopf‐1; HB, hepatitis B; HC, hepatitis C; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; non‐B non‐C, non‐hepatitis B and non‐hepatitis C; HR, hazard ratio.

TABLE 4.

Univariate analysis of 5‐year relapse‐free survival of hepatocellular carcinoma cases by Cox proportional hazards model

| Parameters | Number | HR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General background | ||||

| Age (≥60 years/<60 years) | 351/61 | 1.42 | 0.96–2.09 | 0.0660 |

| Sex (male/female) | 351/61 | 0.74 | 0.53–1.03 | 0.0860 |

| Hepatitis virus infection (HB, HC/non‐B non‐C) | 160/252 | 1.25 | 0.95–1.63 | 0.1010 |

| Child–Pugh classification (B/A) | 14/398 | 1.51 | 0.80–2.85 | 0.2300 |

| Tumor factor | ||||

| Tumor number (>2/1) | 134/278 | 2.48 | 1.91–3.23 | <0.0001 |

| Tumor size (≥5 cm/<5 cm) | 176/236 | 1.79 | 1.39–2.31 | <0.0001 |

| Histology (poor/well or moderate) | 61/351 | 1.26 | 0.89–1.78 | 0.2060 |

| Lymph node metastasis (positive/negative) | 4/408 | 4.60 | 1.46–14.48 | 0.0360 |

| Vascular invasion (positive/negative) | 155/257 | 1.96 | 1.52–2.54 | <0.0001 |

| Capsular formation (positive/negative) | 351/59 | 1.04 | 0.72–1.51 | 0.8410 |

| Capsular invasion (positive/negative) | 284/123 | 1.41 | 1.06–1.89 | 0.0170 |

| UICC stage (IIIA–IVA/IA–II) | 113/299 | 2.32 | 1.77–3.04 | <0.0001 |

| DKK1/CKAP4 expression | ||||

| DKK1+/CKAP4+ vs. DKK1 − CKAP4− | 55/159 | 2.58 | 1.78–3.73 | <0.0001 |

| DKK1+/CKAP4+ vs. DKK1 + CKAP4− | 55/162 | 2.76 | 1.91–4.00 | <0.0001 |

| DKK1+/CKAP4+ vs. DKK1 − CKAP4+ | 55/36 | 4.02 | 2.25–7.18 | <0.0001 |

Note: p values ≤0.05 are statistically significant.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CKAP4, cytoskeleton‐associated protein 4; DKK1, Dickkopf‐1; HB, hepatitis B; HC, hepatitis C; non‐B non‐C, non‐hepatitis B and non‐hepatitis C; HR, hazard ratio.

TABLE 5.

Multivariate analysis of 5‐year relapse‐free survival of hepatocellular carcinoma cases by Cox proportional hazards model

| Parameters | Number | HR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General background | ||||

| Age (≥60 years/<60 years) | 351/61 | 1.34 | 0.90–1.99 | 0.145 |

| Sex (male/female) | 351/61 | 0.64 | 0.45–0.90 | 0.011 |

| Tumor factor | ||||

| Tumor number (>2/1) | 134/278 | 2.26 | 1.73–2.95 | <0.0001 |

| Tumor size (≥5 cm/<5 cm) | 176/236 | 1.40 | 1.06–1.84 | 0.018 |

| Vascular invasion (positive/negative) | 155/257 | 1.51 | 1.14–2.00 | 0.004 |

| Capsular invasion (positive/negative) | 284/123 | 1.21 | 0.90–1.64 | 0.204 |

| DKK1/CKAP4 expression | ||||

| DKK1+/CKAP4+ vs. DKK1 − CKAP4− | 55/159 | 2.61 | 1.78–3.79 | <0.0001 |

| DKK1+/CKAP4+ vs. DKK1 + CKAP4− | 55/162 | 2.61 | 1.78–3.81 | <0.0001 |

| DKK1+/CKAP4+ vs. DKK1 − CKAP4+ | 55/36 | 4.17 | 2.32–7.49 | <0.0001 |

Note: p values ≤0.05 are statistically significant.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CKAP4, cytoskeleton‐associated protein 4; DKK1, Dickkopf‐1; HB, hepatitis B; HC, hepatitis C; non‐B non‐C, non‐hepatitis B and non‐hepatitis C; HR, hazard ratio.

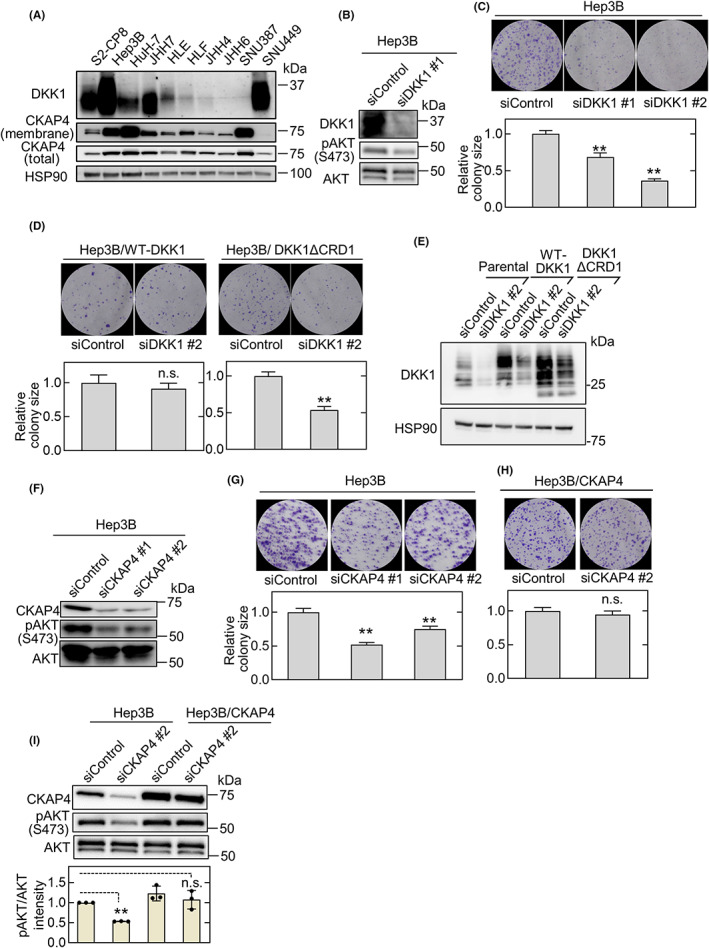

3.2. Dickkopf‐1 and CKAP4 are expressed in HCC cells in a cell context manner

Expression levels of DKK1 and CKAP4 were examined in nine HCC cell lines compared to S2‐CP8 pancreatic cancer cells that have high expression levels of both proteins (Figure 2A). The DKK1 expression levels were variable, with the strongest expression in Hep3B and SNU449 cells followed by JHH7 and HuH‐7 cells and lower expression in HLE, HLF, JHH4, JHH6, and SNU387 cells.

FIGURE 2.

Dickkopf‐1 (DKK1) and cytoskeleton‐associated protein 4 (CKAP4) are required for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cell proliferation. (A) Various HCC and S2‐CP8 pancreatic cancer cells were biotinylated, and cell surface proteins were precipitated using NeutrAvidin Agarose beads. Precipitates (membranes) were probed with an anti‐CKAP4 Ab, and the cell lysates were probed with the indicated Abs. Heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) was used as a loading control. (B) Lysates from Hep3B cells transfected with control siRNA (siControl) or DKK1 siRNA #1 (siDKK1 #1) were probed with the indicated Abs. (C) Hep3B cells transfected with control or two independent DKK1 siRNAs were cultured for 14 days. The areas of the colonies were measured. Microscopic images of representative colonies (top panels) and colony areas (bottom panels) are shown. The areas of at least 50 colonies were measured for each condition, and the results are expressed relative to the control condition. Data are presented as the mean ± SE. **p < 0.01 (ANOVA post‐hoc test). (D) Hep3B cells stably expressing WT DKK1 or DKK1ΔCRD1 (cysteine‐rich domain 1) were transfected with control or DKK1 siRNA #2 and cultured for 14 days. **p < 0.01 (Student's t‐test). n.s., not significant. (E) Lysates from Hep3B cells and Hep3B cells stably expressing WT DKK1 or DKK1ΔCRD1 and transfected with control or DKK1 siRNA #2 were probed with the indicated Abs. (F) Lysates from Hep3B cells transfected with control or two independent CKAP4 siRNAs (siCKAP4) were probed with the indicated Abs. (G) Hep3B cells transfected with control or two independent CKAP4 siRNAs were cultured for 14 days. The areas of the colonies were measured. **p < 0.01 (ANOVA post‐hoc test). (H) Hep3B cells stably expressing CKAP4 and transfected with control or CKAP4 siRNA #2 were cultured for 14 days. n.s., not significant (Student's t‐test). (I) Lysates from Hep3B cells and Hep3B cells stably expressing CKAP4 transfected with control or CKAP4 siRNA #2 were probed with the indicated Abs (top panels). Relative band intensities for pAKT/AKT are shown in arbitrary units (bottom panel). Scale bars, 1 mm. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. **p < 0.01 (ANOVA post‐hoc test). n.s., not significant

Higher CKAP4 protein levels were observed in the total cell lysates from Hep3B, HuH‐7, JHH7, HLF, and SNU387 cells than in other HCC cells (Figure 2A, CKAP4 (total)). Because CKAP4 primarily localizes to the ER and partly to the plasma membrane, its cell surface expression levels were evaluated. Localization of CKAP4 to the plasma membrane was clearly detected in Hep3B, HuH‐7, JHH7, HLF, and SNU387 cells, depending on total expression level (Figure 2A, CKAP4 (membrane)). The DKK1 and CKAP4 mRNA levels in these HCC cell lines were almost comparable to their protein levels in the total cell lysates (Figure S1A). Therefore, Hep3B and JHH7 cells were used in subsequent experiments to represent HCC cells with DKK1‐positive and cell surface CKAP4 expression.

3.3. DKK1‐CKAP4 axis promotes HCC cell proliferation

Knockdown of DKK1 by two different siRNA in Hep3B cells resulted in the inhibition of AKT activity and colony formation in vitro (Figure 2B,C). Colony formation was restored by ectopically expressed WT DKK1 but not by DKK1ΔCRD1, which lacks the CRD1 of DKK1 and does not bind to CKAP4 24 (Figure 2D,E). These results suggested that the phenotype induced by DKK1 knockdown is not an off‐target siRNA effect and that binding of DKK1 to CKAP4 is required for HCC proliferation. Depletion of CKAP4 by two different CKAP4 siRNA inhibited AKT activity in Hep3B cells and colony formation, which could be restored by exogenous CKAP4 expression (Figure 2F–I). Similar results were observed with JHH7 cells (Figure S1B–I), which further confirmed that the DKK1‐CKAP4 axis is active in HCC cells.

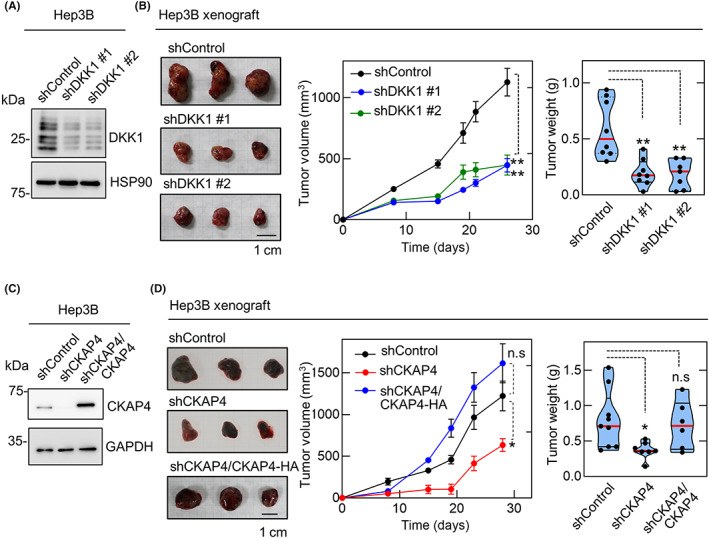

The role of DKK1 and CKAP4 expression in tumorigenesis in vivo was investigated by subcutaneous injection of Hep3B cells into the dorsal flank of immunodeficient mice. The size of the xenografts derived from Hep3B cells stably expressing two different DKK1 shRNAs was less than that of Hep3B tumors expressing control shRNA (Figure 3A,B). Hep3B cell‐induced xenograft tumor formation was also inhibited by CKAP4 knockdown and rescued by CKAP4 expression (Figure 3C,D). These results indicated that expression of both DKK1 and CKAP4 is required for tumor formation in vivo and suggested that CKAP4 is a potential molecular target for HCC therapy.

FIGURE 3.

Dickkopf‐1 (DKK1) and cytoskeleton‐associated protein 4 (CKAP4) are necessary for hepatocellular carcinoma tumor formation in vivo. (A, B) Lysates from Hep3B cells stably expressing control or two independent DKK1 shRNAs were probed with the indicated Abs (A). Hep3B cells stably expressing control (n = 8) or two independent DKK1 shRNAs (#1, n = 8; #2, n = 7) were subcutaneously inoculated into immunodeficient mice (B). Tumor volumes are presented as the mean ± SE, and tumor weights are plotted as violin plots with median values indicated by the red lines and the interquartile ranges by the dotted lines. **p < 0.01 (ANOVA post hoc test). (C, D) Lysates from Hep3B cells stably expressing control shRNA, CKAP4 shRNA, or CKAP4 shRNA and CKAP4‐HA were probed with the indicated Abs (C). Hep3B cells stably expressing control shRNA (n = 9), CKAP4 shRNA (n = 7), or CKAP4 shRNA and CKAP4‐HA (n = 6) were subcutaneously inoculated into immunocompromised mice (D). Scale bars, 10 mm. *p < 0.05 (ANOVA post hoc test). n.s., not significant

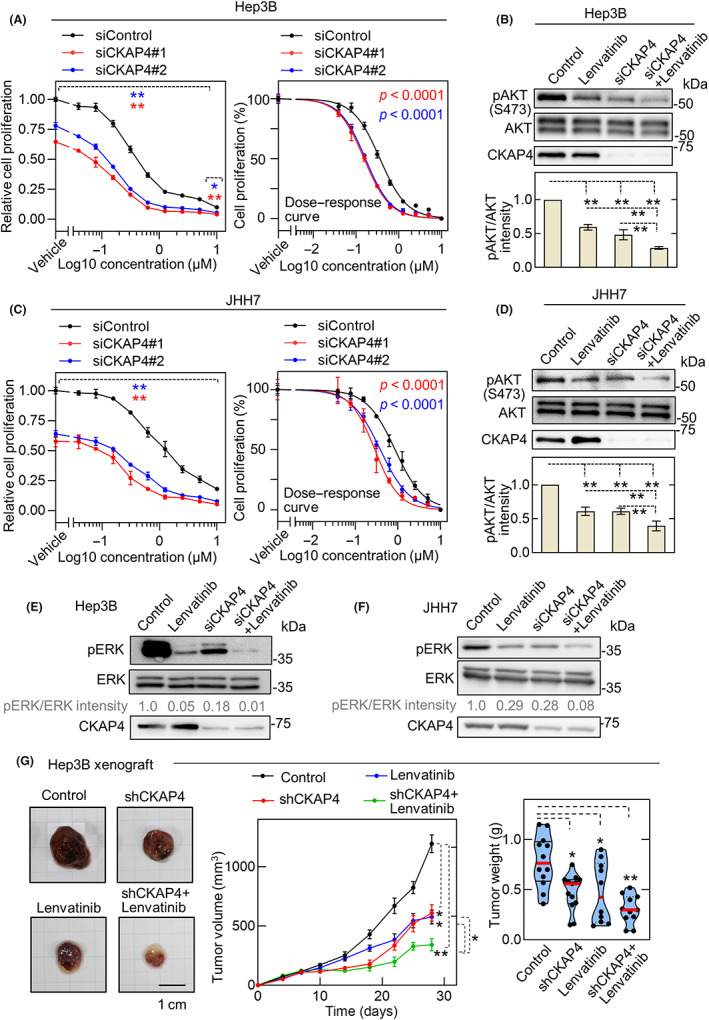

3.4. Depletion of CKAP4 in HCC cells enhances antitumor activity of lenvatinib

Lenvatinib is a multikinase inhibitor that is widely used in clinical practice for advanced HCC cases. 7 , 37 Lenvatinib exerts its antitumor effect by suppressing the activation of AKT and ERK downstream of multiple RTKs. 38 , 39 In contrast, CKAP4 induces activation of AKT and regulates cell proliferation independently of RTKs. 24 Therefore, the combined effects of CKAP4 depletion and lenvatinib, which have a common point of action, AKT, through different pathways, were evaluated. Lenvatinib inhibited 2D cell proliferation of Hep3B cells in a concentration‐dependent manner. Knockdown of CKAP4 also inhibited 2D cell proliferation, and the addition of lenvatinib showed further inhibition (Figure 4A, left panel). The dose‐dependent growth inhibition at each lenvatinib concentration in CKAP4‐deficient cells was significantly higher than in the control siRNA‐treated group (Figure 4A, right panel). Consistent with these results, both CKAP4 knockdown and lenvatinib treatment inhibited AKT activity in Hep3B cells, and their combination showed the strongest inhibition (Figure 4B). Similar results were observed for JHH7 cells (Figure 4C,D). Lenvatinib is known to inhibit ERK in HCC cells. 38 Indeed, this multiple RTK inhibitor suppressed ERK in Hep3B and JHH7 cells (Figure 4E,F). Knockdown of CKAP4 also inhibited ERK and enhanced the inhibitory activity by lenvatinib (Figure 4E,F).

FIGURE 4.

Cytoskeleton‐associated protein 4 (CKAP4) depletion in hepatocellular carcinoma cells enhances the antitumor activity of lenvatinib. (A, C) Hep3B (A) and JHH7 (C) cells were transfected with control or two independent CKAP4 siRNAs and then subjected to a 2D cell proliferation assay in the presence of the indicated concentration of lenvatinib (left panels). Results are expressed as arbitrary units (siControl cells without lenvatinib treatment = 1). Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Normalized dose–response curves of cell proliferation analyzed by nonlinear regression model are shown. Each curve was statistically compared using logIC50 as a parameter (right panels). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 (ANOVA post hoc test). (B, D) Hep3B (B) and JHH7 (D) cells transfected with control or CKAP4 siRNA were treated with vehicle or 1 μM lenvatinib for 12 h. Cell lysates were probed with the indicated antibodies (top panels). Relative band intensities for pAKT/AKT are shown in arbitrary units (bottom panel). **p < 0.01 (ANOVA post‐hoc test). (E, F) Hep3B (E) and JHH7 (F) cells transfected with control or CKAP4 siRNA were treated with vehicle or 1 μM lenvatinib for 12 h. Cell lysates were probed with the indicated Abs (top panels). Relative band intensities for pERK/ERK are shown in arbitrary units. (G) Mice were subcutaneously inoculated with Hep3B cells stably expressing control or CKAP4 shRNA and treated daily with vehicle (control: n = 12, shCKAP4: n = 13) or 1 mg/kg of lenvatinib orally (control, n = 10; shCKAP4, n = 11). Tumor development was observed for 28 days. Tumor volumes are shown as the mean ± SE. Tumor weights are plotted as violin plots. Scale bar, 10 mm. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 (ANOVA post‐hoc test)

Oral administration of lenvatinib to immunodeficient mice inoculated with Hep3B cells in the dorsal flank inhibited in vivo tumor formation as well as CKAP4 depletion (Figure 4G). Depletion of CKAP4 or lenvatinib treatment alone decreased tumor growth by approximately 50%, and their combination caused approximately 75% growth inhibition (Figure 4G). These results indicated that CKAP4 depletion and lenvatinib could suppress in vivo HCC tumor growth through AKT or ERK inhibition and that their combination had additive antitumor effects.

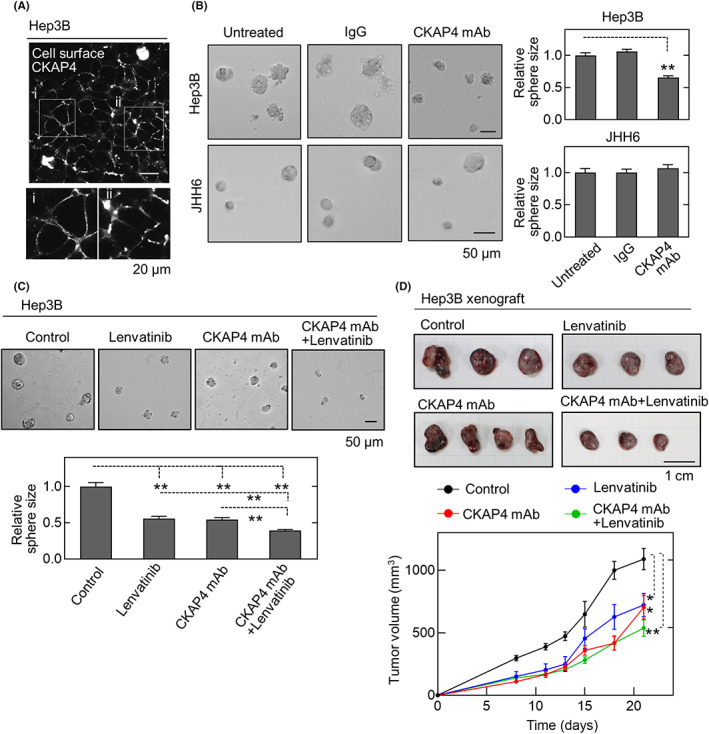

3.5. Combination of anti‐CKAP4 Ab and lenvatinib shows strong inhibition against HCC cell proliferation

Anti‐CKAP4 mAb (3F11‐2B10) was generated by immunizing CKAP4 KO mice with the recombinant extracellular domain of human CKAP4. This Ab inhibits the binding of DKK1 to CKAP4 and suppresses tumor formation in a pancreatic xenograft model. 27 When intact Hep3B cells were stained with the anti‐CKAP4 Ab without permeabilization, CKAP4 was detected on the plasma membrane (Figure 5A), indicating that the Ab can recognize CKAP4 on the plasma membrane of HCC cells. This Ab suppressed sphere formation by Hep3B cells in vitro, but not JHH6 cells, an HCC cell line negative for DKK1 and cell surface CKAP4 expression (Figure 5B, see also Figure 2A). Based on the results that CKAP4 depletion enhanced the antitumor effect of lenvatinib, the combined effect of anti‐CKAP4 Ab and lenvatinib was further evaluated. Of note, the combination of anti‐CKAP4 Ab and lenvatinib strongly inhibited Hep3B sphere formation compared to each treatment alone (Figure 5C).

FIGURE 5.

Anti‐cytoskeleton‐associated protein 4 (CKAP4) Ab and lenvatinib additively inhibit hepatocellular carcinoma growth. (A) Hep3B cells were stained with anti‐CKAP4 Ab under nonpermeabilizing conditions. Signals were detected using the tyramide signal amplification (TSA) system. Scale bar, 20 μm. (B) Hep3B (top left panels) and JHH6 cells (bottom left panels) treated with 20 μg/ml control IgG or anti‐CKAP4 Ab were subjected to the sphere formation assay. For each condition, the sizes of the spheres are expressed relative to the control condition. Scale bar, 50 μm. Data are presented as the mean ± SE. **p < 0.01 (ANOVA post hoc test). (C) Hep3B cells treated with 20 μg/ml anti‐CKAP4 Ab, 0.1 μM lenvatinib, or their combination were subjected to the sphere formation assay. Scale bar, 50 μm. **p < 0.01 (ANOVA post hoc test). (D) Hep3B cells were subcutaneously transplanted into immunodeficient mice. From day 2 after transplantation, control IgG or anti‐CKAP4 Ab (250 μg/body) was given intravenously three times a week with or without 1 mg/kg lenvatinib orally six times per week (control, n = 8; anti‐CKAP4 Ab, n = 14; lenvatinib, n = 11; anti‐CKAP4 Ab + lenvatinib, n = 10). Tumor development was observed for 21 days. Scale bar, 10 mm. Data are presented as the mean ± SE. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 (Wilcoxon's rank–sum test)

Furthermore, to examine the antitumor effect of anti‐CKAP4 Ab–lenvatinib combination therapy in a xenograft tumor model, mice were intravenously treated with control IgG or anti‐CKAP4 Ab three times per week, and vehicle or lenvatinib was given orally six times per week. Tumor development was followed for 21 days. Treatment with anti‐CKAP4 Ab or lenvatinib alone inhibited tumor growth compared to the untreated control group (Figure 5D). Furthermore, the combined treatment potently inhibited tumorigenesis compared to the single agents (Figure 5D).

It was shown that lenvatinib inhibits angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. 38 , 40 Human umbilical vascular endothelial cells expressed DKK1 less than JHH7 or Hep3B cells, which was a low level similar to that of HuH‐7 cells, and plasma membrane CKAP4 expression in HUVECs was comparable to that of HuH‐7 cells (Figure S2A,B), suggesting that the DKK1‐CKAP4 signal is not highly activated. Consistently, anti‐CKAP4 Ab did not significantly inhibit cell proliferation of HUVECs under the conditions that lenvatinib did it. In addition, the Ab did not affect the growth‐inhibitory effect of lenvatinib (Figure S2C). Therefore, DKK1‐CKAP4 signaling is less important in endothelial cells compared to cancer cells in an autocrine manner. Taken together, these results suggest that CKAP4 is a molecular target for HCC expressing both DKK1 and CKAP4, and the combination of anti‐CKAP4 Ab and lenvatinib represents a new strategy for HCC therapy.

4. DISCUSSION

It has been reported that DKK1 is overexpressed in HCC and promotes proliferation, migration, and invasion. 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 Contradictory results have been reported for the relationship between CKAP4 expression and prognosis. 31 , 32 , 33 However, in these previous studies, the CKAP4‐positive cases must contain both DKK1‐positive and ‐negative cases because the HCC specimens were only stained with an anti‐CKAP4 Ab. In this study, we found that simultaneous expression of DKK1 and CKAP4 is associated with HCC aggressiveness and poor prognosis compared to the expression of either alone, using tissue microarray and clinicopathological data from 412 HCC patients. Similar results have been observed for pancreatic, lung, and esophageal cancer. 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 Therefore, immunohistochemical analyses of both DKK1 and CKAP4 expression are necessary to evaluate the activation of the DKK1‐CKAP4 axis in HCC.

Clinicopathological examination revealed that simultaneous expression of both DKK1 and CKAP4 is significantly associated with various clinicopathological parameters. Because cases positive for both DKK1 and CKAP4 showed frequent extrahepatic recurrence, especially in the lung, they were more likely to be ineligible for surgical resection, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, radiofrequency ablation, or liver transplantation. There were no significant differences between the cases positive for both DKK1 and CKAP4 and the cases positive for only CKAP4 for some clinicopathological parameters. One possible explanation could be that there are other sources of DKK1 in the tumor microenvironment, including stromal tissues or blood cells.

Among the nine HCC cells, Hep3B and JHH7 cells highly expressed DKK1 and cell surface CKAP4. Depletion of either DKK1 or CKAP4 from these cells inhibited cell growth in vitro and in vivo. The CRD1 of DKK1 is required for the binding of DKK1 to CKAP4. 24 The results showing that DKK1ΔCRD1 could not rescue the phenotypes induced by DKK1 depletion supports the idea that CKAP4 functions as a DKK1 receptor to promote HCC cell proliferation.

Both FGF and FGFR are typically overexpressed in HCC, and in particular, aberrant expression of FGF19/FGFR4 contributes to HCC progression and ultimately activates downstream signaling pathways such as PI3K/AKT and Ras/ERK. 41 Indeed, lenvatinib has been shown to significantly inhibit the proliferation of HCC cell lines overexpressing FGF19 and FGFRs in vitro and in vivo 38 , 42 through the inhibition of AKT and ERK. As the DKK1‐CKAP4 axis activates AKT through PI3K, the inhibition of HCC cell proliferation by anti‐CKAP4 Ab is reasonable. Therefore, treatment of HCC with both DKK1‐ and CKAP4‐positive patients with anti‐CKAP4 Ab and multikinase inhibitors could be clinically rational.

The IMbrave 150 trial showed that the combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab, which target programmed death‐ligand 1 (PD‐L1) 43 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), 44 respectively, is associated with significantly better overall survival and relapse‐free survival than sorafenib, a conventional multikinase inhibitor. 45 Irrespective of its clinical efficacy, there is growing concern about immune‐related adverse events in various organs, which might shorten the therapeutic intervention. 46 Therefore, lenvatinib remains the second most important drug in the treatment of unresectable HCC after the combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab. Depletion of CKAP4 suppressed ERK in an unknown manner. As lenvatinib and CKAP4 knockdown suppressed ERK activity more than additively, their inhibitory mechanisms for ERK would be different. In addition, combining the anti‐CKAP4 Ab and lenvatinib resulted in stronger inhibition of AKT activity and cell proliferation than either monotherapy. This combination is a promising strategy because it improves the antitumor effect of lenvatinib and also reduces the dose. However, there is still a limitation for the use of anti‐CKAP4 Ab. As this Ab is theoretically effective for HCC cells with DKK1 expression and CKAP4 membrane expression, it would not be useful for tumor cells without expression of either DKK1 or CKAP4 due to intratumoral heterogeneity of DKK1 and CKAP4 expression.

In conclusion, simultaneous expression of DKK1 and its receptor, CKAP4, is an important prognostic factor of HCC. The DKK1‐CKAP4 axis could represent a novel target for HCC therapy, and the lenvatinib–anti‐CKAP4 Ab combination could underpin the development of a novel therapeutic strategy for HCC.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: K.I., S.M., H.G., and A.K. Methodology: K.I., S.M., R.S., H.K., M.A., H.G., Y.Z., and A.K. Investigation: K.I., S.M., H.K., H.G., and Y.Z. Resources: Y.Z., M.A., and T.K. Writing: K.I., S.M., R.S., H.G., and A.K. Supervision: T.F. and A.K. Project administration: K.I., S.M., and A.K. Funding acquisition: S.M., R.S., and A.K.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The work was supported by Grants‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan to A.K. (2016–2021, No. 16H06374), S.M. (2018–2020, No. 18975691, No. 18K06956; 2021–2023, No. 21K07121), and R.S. (2020–2021, No. 20K16330; 2022–2023, No. 22K15511). This work was also supported by the Project for Cancer Research And Therapeutic Evolution (P‐CREATE) (18cm0106132h0001, 2018) and (20cm0106152h0002, 2019–2021) and the Translational Research Program (22ym0126039h0002, 2021–2023) to A.K., and Science and Technology Platform Program for Advanced Biological Medicine (22am0401003h0004, 2021–2023) to S.M. from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) and by grants to A.K from the Yasuda Memorial Foundation, the Ichiro Kanehara Foundation of the Promotion of Medical Science and Medical Care, and Integrated Frontier Research for Medical Science Division, Institute for Open and Transdisciplinary Research Initiatives (OTRI), Osaka University to S.M.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Akira Kikuchi is a current member (Associate Editor) of the editorial board of Cancer Science. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Approval of the research protocol by an institutional review board: The protocol for human specimens was approved by the ethical review boards of the Graduate School of Medicine, Kobe University, Japan (No. 180343) and the Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka University, Japan (No. 19292).

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Registry and registration no. of the study/trial: N/A.

Animal studies: All animal study protocols were approved by the Animal Research Committee of Osaka University, Japan (No. 01‐033‐009).

Supporting information

Data S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Murakami (Division of Clinical and Translational Research Center, Kobe University Hospital, Kobe, Japan) for her help with the clinical statistics.

Iguchi K, Sada R, Matsumoto S, et al. DKK1‐CKAP4 signal axis promotes hepatocellular carcinoma aggressiveness. Cancer Sci. 2023;114:2063‐2077. doi: 10.1111/cas.15743

Kosuke Iguchi and Ryota Sada contributed equally to this study.

Contributor Information

Shinji Matsumoto, Email: shinjim@molbiobc.med.osaka-u.ac.jp.

Akira Kikuchi, Email: akikuchi@cider.osaka-u.ac.jp.

REFERENCES

- 1. Attwa MH, El‐Etreby SA. Guide for diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:1632‐1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goossens N, Sun X, Hoshida Y. Molecular classification of hepatocellular carcinoma: potential therapeutic implications. Hepat Oncol. 2015;2:371‐379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marquardt JU, Andersen JB, Thorgeirsson SS. Functional and genetic deconstruction of the cellular origin in liver cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:653‐667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grabinski N, Ewald F, Hofmann BT, et al. Combined targeting of AKT and mTOR synergistically inhibits proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer. 2012;11:85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bruix J, Reig M, Sherman M. Evidence‐based diagnosis, staging, and treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:835‐853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378‐390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first‐line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non‐inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391:1163‐1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia‐Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iavarone M, Cabibbo G, Biolato M, et al. Predictors of survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma who permanently discontinued sorafenib. Hepatology. 2015;62:784‐791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee MS, Ryoo BY, Hsu CH, et al. Atezolizumab with or without bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (GO30140): an open‐label, multicentre, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:808‐820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Al‐Salama ZT, Syed YY, Scott LJ. Lenvatinib: a review in hepatocellular carcinoma. Drugs. 2019;79:665‐674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Niehrs C. Function and biological roles of the Dickkopf family of Wnt modulators. Oncogene. 2006;25:7469‐7481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kikuchi A, Fumoto K, Kimura H. The Dickkopf1‐cytoskeleton‐associated protein 4 axis creates a novel signalling pathway and may represent a molecular target for cancer therapy. Br J Pharmacol. 2017;174:4651‐4665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kagey MH, He X. Rationale for targeting the Wnt signalling modulator Dickkopf‐1 for oncology. Br J Pharmacol. 2017;174:4637‐4650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fezza M, Moussa M, Aoun R, Haber R, Hilal G. DKK1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma inflammation, migration and invasion: implication of TGF‐β1. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0223252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Qin X, Zhang H, Zhou X, et al. Proliferation and migration mediated by Dkk‐1/Wnt/β‐catenin cascade in a model of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Transl Res. 2007;150:281‐294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yang H, Chen GD, Fang F, et al. Dickkopf‐1: as a diagnostic and prognostic serum marker for early hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Biol Markers. 2013;28:286‐297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang J, Zhao Y, Yang Q. Sensitivity and specificity of Dickkopf‐1 protein in serum for diagnosing hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta‐analysis. Int J Biol Markers. 2014;29:e403‐e410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li J, Gong W, Li X, et al. Recent Progress of Wnt pathway inhibitor Dickkopf‐1 in liver cancer. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2018;18:5192‐5206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schweizer A, Ericsson M, Bachi T, Griffiths G, Hauri HP. Characterization of a novel 63 kDa membrane protein. Implications for the organization of the ER‐to‐Golgi pathway. J Cell Sci. 1993;104(Pt 3):671‐683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shibata Y, Shemesh T, Prinz WA, Palazzo AF, Kozlov MM, Rapoport TA. Mechanisms determining the morphology of the peripheral ER. Cell. 2010;143:774‐788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Klopfenstein DR, Kappeler F, Hauri HP. A novel direct interaction of endoplasmic reticulum with microtubules. EMBO J. 1998;17:6168‐6177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vedrenne C, Hauri HP. Morphogenesis of the endoplasmic reticulum: beyond active membrane expansion. Traffic. 2006;7:639‐646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kimura H, Fumoto K, Shojima K, et al. CKAP4 is a Dickkopf1 receptor and is involved in tumor progression. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:2689‐2705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shinno N, Kimura H, Sada R, et al. Activation of the Dickkopf1‐CKAP4 pathway is associated with poor prognosis of esophageal cancer and anti‐CKAP4 antibody may be a new therapeutic drug. Oncogene. 2018;37:3471‐3484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kajiwara C, Fumoto K, Kimura H, et al. p63‐dependent Dickkopf3 expression promotes esophageal cancer cell proliferation via CKAP4. Cancer Res. 2018;78:6107‐6120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kimura H, Yamamoto H, Harada T, et al. CKAP4, a DKK1 receptor, is a biomarker in exosomes derived from pancreatic cancer and a molecular target for therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:1936‐1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kimura H, Sada R, Takada N, et al. The Dickkopf1 and FOXM1 positive feedback loop promotes tumor growth in pancreatic and esophageal cancers. Oncogene. 2021;40:4486‐4502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nagoya A, Sada R, Kimura H, et al. CKAP4 is a potential exosomal biomarker and a therapeutic target for lung cancer. Translational LungCancer Res. 2023; in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kikuchi A, Matsumoto S, Sada R. Dickkopf signaling, beyond Wnt‐mediated biology. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2022;125:55‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen ZY, Wang T, Gan X, et al. Cytoskeleton‐associated membrane protein 4 is upregulated in tumor tissues and is associated with clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2020;19:3889‐3898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li SX, Tang GS, Zhou DX, et al. Prognostic significance of cytoskeleton‐associated membrane protein 4 and its palmitoyl acyltransferase DHHC2 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2014;120:1520‐1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li SX, Liu LJ, Dong LW, et al. CKAP4 inhibited growth and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma through regulating EGFR signaling. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:7999‐8005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fujii S, Matsumoto S, Nojima S, Morii E, Kikuchi A. Arl4c expression in colorectal and lung cancers promotes tumorigenesis and may represent a novel therapeutic target. Oncogene. 2015;34:4834‐4844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shojima K, Sato A, Hanaki H, et al. Wnt5a promotes cancer cell invasion and proliferation by receptor‐mediated endocytosis‐dependent and ‐independent mechanisms, respectively. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mitsuishi Y, Taguchi K, Kawatani Y, et al. Nrf2 redirects glucose and glutamine into anabolic pathways in metabolic reprogramming. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:66‐79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mody K, Abou‐Alfa GK. Systemic therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in an evolving landscape. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Matsuki M, Hoshi T, Yamamoto Y, et al. Lenvatinib inhibits angiogenesis and tumor fibroblast growth factor signaling pathways in human hepatocellular carcinoma models. Cancer Med. 2018;7:2641‐2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhao Y, Zhang YN, Wang KT, Chen L. Lenvatinib for hepatocellular carcinoma: from preclinical mechanisms to anti‐cancer therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2020;1874:188391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yamamoto Y, Matsui J, Matsushima T, et al. Lenvatinib, an angiogenesis inhibitor targeting VEGFR/FGFR, shows broad antitumor activity in human tumor xenograft models associated with microvessel density and pericyte coverage. Vasc Cell. 2014;6:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Raja A, Park I, Haq F, Ahn SM. FGF19‐FGFR4 signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cells. 2019;8:536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ogasawara S, Mihara Y, Kondo R, Kusano H, Akiba J, Yano H. Antiproliferative effect of Lenvatinib on human liver cancer cell lines in vitro and In vivo. Anticancer Res. 2019;39:5973‐5982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Herbst RS, Soria JC, Kowanetz M, et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti‐PD‐L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature. 2014;515:563‐567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ferrara N, Hillan KJ, Novotny W. Bevacizumab (Avastin), a humanized anti‐VEGF monoclonal antibody for cancer therapy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:328‐335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1894‐1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Postow MA, Sidlow R, Hellmann MD. Immune‐related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:158‐168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1