Summary

Engineered microorganisms hold potential for disease diagnosis and treatment. Here, we present a protocol to engineer E. coli Nissle 1917 strain (iROBOT) using genome insertion and plasmid construction to diagnose, record, and ameliorate inflammatory bowel disease in mice. We describe steps for constructing and administering iROBOT, diagnosing and recording colitis, preparing samples, and analyzing fluorescence and base editing ratios of iROBOT. We detail a colitis ameliorating assay using the disease activity index, colon length, tissue pathological section, and cytokine analysis.

For complete details of the use and execution of this protocol, please refer to Zou et al.1

Subject area(s): Health Sciences, Microbiology, Model Organisms, Molecular Biology, CRISPR, Biotechnology and Bioengineering

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

A method for thiosulfate determination in vivo and in vitro colitis models

-

•

Biomarker-regulated drug release system for ameliorating colitis in mice

-

•

Method for measuring bacterial fluorescence and base editing ratios from fecal samples

Publisher’s note: Undertaking any experimental protocol requires adherence to local institutional guidelines for laboratory safety and ethics.

Engineered microorganisms hold potential for disease diagnosis and treatment. Here, we present a protocol to engineerE. coli Nissle 1917 strain (iROBOT) using genome insertion and plasmid construction to diagnose, record, and ameliorate inflammatory bowel disease in mice. We describe steps for constructing and administering iROBOT, diagnosing and recording colitis, preparing samples, and analyzing fluorescence and base editing ratios of iROBOT. We detail a colitis ameliorating assay using the disease activity index, colon length, tissue pathological section, and cytokine analysis.

Before you begin

Bacteria strains

Wild-type Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) was purchased from Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany), and competent E. coli DH5α cells were used to construct the plasmids.

The λ-Red recombination system is a convenient strategy for gene knock-out and knock-in experiments.2 The pKD46 plasmid is a widely used carrier for λ-Red recombination containing the genes γ, β, and exo, whose products are named Gam, Bet, and Exo, respectively.3 Gam inhibits the E. coli RecBCD exonuclease V so that Bet and Exo can promote recombination though a linearized DNA fragment which includes 50–59 bp long homologous arms. In addition, pKD46 is a low-copy and temperature sensitive replicon, and the γ, β, and exo genes are induced by L-arabinose. The EcN strain carrying the pKD46 plasmid was stored at our laboratory.

Mice

6–8-week-old male C57BL/J mice were purchased from Shanghai Model Organisms Center (Shanghai, China).

Institutional permissions

All animal procedures described in this protocol were performed in compliance with Chinese laws and regulations. All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the Guidelines for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the East China University of Science and Technology, and the experiments were approved by the animal ethics committee of the same institution. Readers who want to conduct animal work as described in this protocol need to acquire permission from their Animal Ethics Committee following their institutional guidelines and regulations.

Reagent preparation

Timing: 1–2 days

-

1.Preparation of liquid solutions.

-

a.Ampicillin stock solution: Add 1.0 g of ampicillin to 10 mL ddH2O to prepare the ampicillin stock solution. Next, sterilize the solution using a 0.22 μm filter and store at −20°C for up to 3 months. The final concentration in the media will be 100 μg/mL.

-

b.Streptomycin stock solution: Add 1.0 g of streptomycin sulfate powder to 10 mL ddH2O to prepare the streptomycin stock solution. Next, sterilize the solution using a 0.22 μm filter and store at −20°C for up to 3 months. The final concentration in the media will be 100 μg/mL.

-

c.Kanamycin stock solution: Add 0.5 g of kanamycin sulfate powder to 10 mL ddH2O to prepare the kanamycin stock solution. Next, sterilize the solution using a 0.22 μm filter and store at −20°C for up to 3 months. The final concentration in the media will be 50 μg/mL.

-

d.Chloramphenicol stock solution: Add 0.5 chloramphenicol powder to 10 mL of anhydrous ethanol to prepare the chloramphenicol stock solution. Next, sterilize the solution using a 0.22 μm filter store at −20°C for up to 3 months.

-

e.L-arabinose stock solution: Add 1.5 g of L-arabinose powder to 10 mL ddH2O to prepare the L-arabinose stock solution. Next, sterilize the solution using a 0.22 μm filter and store at −20°C for up to 3 months.

-

f.50% and 10% glycerin solution: Add 50 mL of glycerin to 50 mL ddH2O to obtain a 50% glycerin solution. Add 10 mL of glycerin to 90 mL ddH2O to obtain a 10% glycerin solution. Autoclave for 20 min at 121°C to sterilize the solution.

-

g.Dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) solution: Add 3 g of DSS powder to 100 mL ddH2O to obtain a 3% DSS solution. Next, sterilize the solution using a 0.45 μm filter.

-

a.

Note: the 3% DSS solution administered to mice should be replaced every 2–3 days.

-

2.Preparation of bacterial culture media.

-

a.Lysogeny broth (LB) liquid media: Add 2.5 g of LB powder to 100 mL ddH2O for LB liquid media preparation. Autoclave for 20 min at 121°C to sterilize the solution.

-

b.LB plates: Add 2.5 g of LB powder and 1.5 g of agar to 100 mL ddH2O for LB plates preparation. Autoclave for 20 min at 121°C to sterilize the media and add the appropriate concentration of antibiotics to the media when it cools down to approximately 55°C. Then, pour media into 90 mm plates, about 20 mL for each plate. Leave to solidify on a clean bench and store at 4°C for up to 1 month.

-

c.X-gal agar plates: Add 2.5 g of LB powder and 1.5 g of agar to 100 mL ddH2O for LB plates. Autoclave for 20 min at 121°C to sterilize the media and add 100 μL 50 mg/mL streptomycin sulfate and 200 μL 20 mg/mL X-gal when it cools down to approximately 55°C. Then, pour media into 90 mm plates, about 20 mL for each plate. Leave to solidify on a clean bench and store at 4°C for up to 7 days.

-

a.

-

3.Preparation of Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) buffer and agarose gel.

-

a.TAE buffer: Add 80 mL of 50× TAE buffer to 920 mL ddH2O to obtain a 1× TAE buffer.

-

b.Agarose gel: Add 0.9 g of agarose to 60 mL 1× TAE buffer, allow it to dissolve by microwave heating, and add 6 μL of nucleic acid dye when the gel cools down to around 55°C. Next, pour into the dispensing slot and insert into the comb, leave at 20°C–25°C for 30 min, and use after it has completely solidified.

-

a.

λ-Red recombination preparation

Timing: 2 days

-

4.Determination of the integration site in the EcN genome to insert the α-hemolysin-secreting system (hlyB and hlyD), kanR and ACG-tag-lacZ.

-

a.Choose a non-essential gene site to insert the α-hemolysin-secreting system (hlyB and hlyD), kanR and ACG-tag-lacZ.Note: In this protocol, hlyB, hlyD, kanR and ACG-tag-lacZ are inserted into the EcN genome to replace lacI4 and the original start codon (ATG) of lacZ.

-

b.Choose approximately 50 bp upstream and downstream the homologous arms at the determined genetic locus.Note: For lacI and lacZ of EcN, we referred to the NCBI GenBank CP022686.1. Homologous arms can be 35–59 bp but in general, the longer the homologous arms, the higher the integration efficiency.

-

c.We selected the promoters Pj23104, PAmpR, and Pj23105 to drive hlyB-hlyD, kanR, and ACG-tag-lacZ expression, respectively.Note: The complete DNA insertion fragment (named the BD-ACG-tag) was synthesized by Rui Mian Biological Technology (Shanghai, China) (Figure 1).

-

d.Amplify DNA fragments (for gene knock-in) by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for gene knock-in (Figure 1B).Note: The concentration of DNA fragments used for gene knock-in should reach 200 ng/μL.

Reagent Amount 2× Phanta® Max Buffer 25 μL Phanta® Max Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase 1 μL dNTP Mix (10 mM each) 1 μL Forward primer (10 μM) 1 μL Reverse primer (10 μM) 1 μL DNA template 25–50 ng ddH2O To 50 μL Steps Temperature Time step 1 95°C 8 min step 2 95°C 20 s step 3 56°C–65°C 20 s step 4 72°C 1 kb/min Back to step 2, 34 cycles step 5 72°C 10 min step 6 12°C 5 min Note: Readers can use a software named SnapGene to design primers and Tm calculator (https://tmcalculator.neb.com/) to obtain the annealing temperature (step 3). -

e.Design primers to confirm successful DNA fragment knock-in in the EcN genome (Figure 2). The lengths of the PCR products of wild-type EcN and recombinant EcN are 1614 bp and 5304 bp, respectively.

-

a.

-

5.Retrieval of the DNA fragments from agarose gel.

-

a.Add 5 μL of 10× DNA loading buffer to 50 μL of PCR product.

-

i.Run it on agarose gel to confirm the size using a DNA marker.

-

ii.Carefully excise the agarose gel containing the target DNA fragment.

-

iii.Use the following described protocol to obtain the PCR product (EasyPure® Quick Gel Extraction Kit was used in this protocol).

-

i.

-

b.Place the agarose gel 1.5 mL in an Eppendorf (EP) tube and add 650 μL of Gel Solubilization Buffer (GSB) (approximately 3 volumes of GSB to each volume of agarose excised).

-

c.Incubate at 55°C until the agarose gel completely dissolves, and leave it to cool down to 20°C–25°C.

-

d.Transfer the cooled solution to a Gel-Spin Column in a Collection Tube, and allow it to stand at 20°C–25°C for 1 min.

-

e.Centrifuge for 1 min at 10000 relative centrifugal force (rcf). Discard the flow-through solution.

-

f.Then, add 650 μL of Wash Buffer (WB, add 80 mL ethanol to 20 mL WB before use) to the column and centrifuge for 1 min at 10000 rcf.

-

g.Discard the flow-through solution. Repeat the wash step.

-

h.Use a clean 1.5 mL Eppendorf (EP) tube as the collection tube for the eluted DNA, heated to 55°C for 2 min (with the cap being opened wide).

-

i.Add 35–45 μL of ddH2O preheated at 55°C, allow it to stand at 20°C–25°C for 1 min, and centrifuge for 1 min to elute DNA (10000 rcf).

-

a.

CRITICAL: The indicated materials mentioned previously can be substituted with appropriate alternatives if necessary.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of λ-Red recombination

(A) The map of target DNA on E.coli Nissle 1917 genome.

(B) The map of DNA fragment for knocking and its PCR primers.

(C) The map of recombinant genome DNA on E.coli Nissle 1917 genome.

Figure 2.

Design of sequencing primers for gene knock-in

Plasmid design and construction

Timing: 5 days

-

6.Obtaining linearized DNA fragments.

-

a.The connection and amplification of two connected DNA fragments is performed by overlap PCR5,6 (Figure 3).Note: The hly-AvCys gene was synthesized by Rui Mian Biological Technology (Shanghai, China). The promoters phsA, thsR, thsS, and sfGFP were obtained by PCR from the pWT-CS2R4 plasmid. mCherry was obtained by PCR from the pKD237-3a-2 plasmid.7BE2 and gRNA scaffolds were amplified by PCR from the pWT021a plasmid.8

-

b.Connect the functional genes and their promoter and Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequences through multiple overlap PCR (Figure 4).

-

a.

-

7.Constructing the engineered pWT-AGBM plasmid.

-

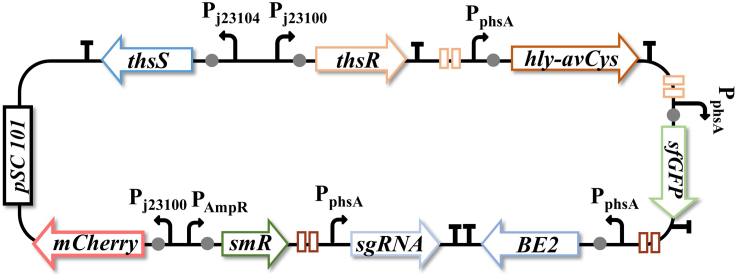

a.The final engineered plasmid, named pWT-AGBM, was composed of six components: a thiosulfate-response system consisting of thsS and thsR with Pj23104 and Pj23100 as promoters to sense thiosulfate, respectively; hly-AvCys with PphsA as a promoter; sfGFP with PphsA as a promoter; the base-editing enzyme BE2 with PphsA as a promoter; sgRNA with PphsA as a promoter; and mCherry with Pj23100 as a promoter. In the presence of thiosulfate, ThsR activates four PphsA promoters to trigger the expression of Hly-AvCystatin (treatment), sfGFP (diagnosis), BE2, and sgRNA (recording) (Figure 5).

-

b.Homologous recombination assembly was performed using the pEASY-Basic Seamless Cloning and Assembly Kit. The instructions are as follows (Figure 6):

-

a.

CRITICAL: The indicated materials and suppliers mentioned previously can be substituted with appropriate alternatives if necessary.

Note: The bacteria should be spread on LB agar plates containing 50 μg/mL streptomycin.

| Reagent | Amount |

|---|---|

| 2× Basic Assembly Mix | 5 μL |

| Linearized vector | 1 μL |

| Fragment A | 1 μL |

| Fragment B | 1 μL |

| Fragment C | 1 μL |

| Fragment D | 1 μL |

-

8.Colony PCR and sequencing to obtain and validate the desired colony for plasmid extraction.

-

a.Pick individual colonies and add to 10 μL of sterilized ddH2O.

-

b.Set PCR primers 400 bp upstream and downstream of the homologous recombination site.

-

c.Run the PCR products on an agarose gel to confirm the desired size, and sequence the correct product.

-

d.Inoculate the remaining 9 μL of the bacterial suspension into 5 mL of LB medium.

-

e.Then, add 500 μL of 50% sterilized glycerin solution to 500 μL bacterial suspension and store at −80°C.Note: The engineering plasmid should be fully sequenced before use for further steps.

Reagent Amount 2× EasyTaq PCR Super Mix 12.5 μL F-primer (10 μM) 1 μL R-primer (10 μM) 1 μL Bacterial suspension 1 μL ddH2O To 25 μL -

f.For plasmid extraction assay (EasyPure® Plasmid MiniPrep Kit was used in this protocol), the instructions are as follows: https://www.transgenbiotech.com/plasmid_dna_purification/easypure_plasmid_miniprep_kit.html.Note: Sequence the whole plasmid before use for further steps.

CRITICAL: Plasmid concentration should exceed 150 ng/μL before being transformed into the EcN strain.

CRITICAL: Plasmid concentration should exceed 150 ng/μL before being transformed into the EcN strain.

-

a.

-

9.

Construction of the pWT-AGBM-D57A plasmid.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of overlap PCR

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of engineering plasmid construction

Figure 5.

Plasmid map of pWT-AGBM

Figure 6.

Guide for construction of the plasmid pWT-AGBM

The pWT-AGBM-D57A plasmid was used as the control in this experiment. Mutate Asp (site 57) of ThsR to Ala using the Fast Mutagenesis System. The instructions are as follows: https://www.transgenbiotech.com/mutagenesis_system/fast_mutagenesis_system.html.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Streptomycin sulfate | Aladdin Biotech | Cat# S105491 |

| Kanamycin sulfate | Aladdin Biotech | Cat# K103024 |

| Ampicillin | Aladdin Biotech | Cat# A105483 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Escherichia coli: Nissle 1917 | DSMZ | Cat# DSM6601 |

| Escherichia coli: DH5α | TransGen Biotech | Cat# CD201 |

| i-ROBOT | This study | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 10010023 |

| L-Arabinose (Ara) | Aladdin Biotech | Cat# A106196 |

| Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) | Aladdin Biotech | Cat# I104812 |

| Dextran sulfate sodium salt (DSS) | MP Biomedicals | Cat# 160110 |

| X-gal | TransGen Biotech | Cat# GF201 |

| Polyformaldehyde | Servicebio | Cat# G1101 |

| Lysogeny broth | Generay Biotech | Cat# GL7002 |

| Agar | Generay Biotech | Cat# RA1001 |

| 50× TAE buffer | Generay Biotech | Cat# T1082 |

| Agarose | Generay Biotech | Cat# RA1011 |

| Glycerin | Generay Biotech | Cat# GA0854 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| pEASY®-Basic Seamless Cloning and Assembly Kit | TransGen Biotech | Cat# CU201 |

| EasyPure® Plasmid MiniPrep Kit | TransGen Biotech | Cat# EM101 |

| EasyPure® Quick Gel Extraction Kit | TransGen Biotech | Cat# EG101 |

| Fast Mutagenesis System | TransGen Biotech | Cat# FM111 |

| GelStain Blue | TransGen Biotech | Cat# GS102-01 |

| Phanta® Max Super-Fidelity DNA polymerase | Vazyme | Cat# P505 |

| Mouse IL-6 ELISA Kit | Sangon Biotech | Cat# D721022 |

| Mouse IFN-γ ELISA Kit | Sangon Biotech | Cat# D721025 |

| Mouse TNF-α ELISA Kit | Sangon Biotech | Cat# D721217 |

| Mouse IL-17 ELISA Kit | Sangon Biotech | Cat# D721024 |

| Mouse MCP-1 ELISA Kit | Sangon Biotech | Cat# D721198 |

| HE dye solution set | Servicebio | Cat# G1003 |

| Masson dye solution set | Servicebio | Cat# G1006 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Male C57BL/6J | Shanghai Model Organisms Center | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| PF-1 | tctcacctgtgacctggcgt | N/A |

| PR-1 | gggttttcccagtcacgacg | N/A |

| SF-1 | ccgctttgagcaactgctct | N/A |

| SR-1 | ttcaggctgcgcaactgttg | N/A |

| Sequalizer-F | gccatcctatggaactgcct | N/A |

| Sequalizer-R | gggttttcccagtcacgacg | N/A |

| thsS | Daeffler et al.7 | N/A |

| thsR | Daeffler et al.7 | N/A |

| BE2 | Tang et al.8 | N/A |

| sfGFP | Daeffler et al.7 | N/A |

| mCherry | Daeffler et al.7 | N/A |

| PphsA | Daeffler et al.7 | N/A |

| kanR | Zou et al.1 | N/A |

| sgRNA | Zou et al.1 | N/A |

| hly-AvCys | Zou et al.1 | N/A |

| hlyB | Zou et al.1 | N/A |

| hlyD | Zou et al.1 | N/A |

| ACG-tag-LacZ | Zou et al.1 | N/A |

| Promoters and SD sequences | Zou et al.1 | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pKD236-4b | Daeffler et al.7 | Addgene #90956 |

| pKD237-3a-2 | Daeffler et al.7 | Addgene #90957 |

| pWT021a | Tang et al.8 | Addgene #107895 |

| pWT-CS2R4 | Zou et al.1 | N/A |

| pWT-AGBM | This study | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism 8 | GraphPad Prism | N/A |

| De Novo DNA | A Salis Lab spin-off | https://salislab.net/software |

| MATLAB | MathWorks | N/A |

| NIS-Elements Viewer | Nikon | N/A |

| Media Cybemetics | Media Cybemetics | N/A |

| FlowJo | BD Biosciences | N/A |

Materials and Equipment

| Reagent | Amount |

|---|---|

| 2×Phanta® Max Buffer | 25 μL |

| Phanta® Max Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | 1 μL |

| dNTP Mix (10 mM each) | 1 μL |

| Forward primer (10 μM) | 1 μL |

| Reverse primer (10 μM) | 1 μL |

| DNA template | 25-50 ng |

| ddH2O | To 50 μL |

20 mg/mL X-gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-beta-D-galacto-pyranoside) solution

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| X-gal | 20 mg/mL | 100 mg |

| Dimethylformamide (DMF) | N/A | 5 mL |

| Total | N/A | 5 mL |

Storage: -20 °C < 6 month. Keep in dark place.

TAE buffer (Tris-acetate-EDTA) 50×

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Acetic Acid (glacial) | 1 M | 60.5 mL |

| Tris Base | 2 M | 242.2 g |

| EDTA sodium salt dihydrate | 50 mM | 18.6 g |

| ddH2O | N/A | To 1000 mL |

| Total | N/A | 1000 mL |

Storage: Store at room temperature.

Step-by-step method details

Preparation of electrocompetent EcN strain (with pKD46) for genome insertion

Timing: 2 days (for steps 1 to 7)

This step involves the preparation of electrocompetent EcN cells with the pKD46 plasmid (EcN-pKD46), the insertion of DNA fragments into the EcN genome, and the selection of the clones with the correct genome insertion.

Preparation of electrocompetent cell

-

1.

Streak the EcN-pKD46 strain on a plate containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin and then cultured at 30°C for 12 h.

-

2.Inoculate a single colony into 5 mL LB media for 12 h (30°C, 220 rpm).

-

a.Inoculate the culture at 1:200 dilution in 50 mL LB media containing 0.2% L-arabinose and 100 μg/mL ampicillin to an OD600 of 0.5–0.6 (30°C, 220 rpm).

-

b.Allow the culture to cool on ice for 10 min.

-

a.

Note: The induction time of L-arabinose is usually 4.5–5 h to ensure the expression of sufficient Gam, Bet, and Exo proteins.

-

3.

Harvest the culture by centrifugation for 10 min at 4°C and 3000 rcf. Wash the cells three times with 30 mL of ice-cold 10% glycerol to prepare electrocompetent cells.

Note: In our protocol, we centrifuged immediately after adding 30 mL ice-cold 10% glycerol to precipitate the culture.

-

4.

After washing three times, resuspend the culture in 1 mL of ice-cold 10% glycerol. Next, transfer into 1.5 mL tubes (100 μL/tube) for DNA transformation.

Transformation

-

5.

Add 10–15 μL of BD-ACG-tag DNA fragments (approximately 2–3 μg) to electrocompetent cells and incubate on ice for 10 min.

-

6.

Add the DNA-cell mixture into a gapped cuvette. Electroporate the mixture at an electric field intensity of 3 kV (15 kV/cm) for 4 ms to transform DNA fragments into electrocompetent cells. Resuspend the cells in 800 μL LB media immediately after electroporation pulse and recovery at 37°C for 2–3 h.

Note: In our protocol, the activation process took more than 2 h to ensure the recombination of DNA fragments and bacterial genomes.

-

7.

Pellet the cultures at 6000 rcf for 1 min. Discard the supernatant and resuspend the cells. Spread the cultures on agar plates containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin and culture at 37°C for 12 h.

Selection of the clones with the desired genome insertion

Timing: 2 days

This step involves the selection of the clones with correct genome insertion.

-

8.

Pick 5–10 colonies and add to 10 μL sterilized ddH2O, and use 1 μL of the suspension to execute the colony PCR program (use 1 μL EcN suspension as a control, refer to step 8 in “before you begin” section). Add the remaining bacterial suspension to 5 mL of LB medium containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin and culture at 37°C for 12 h.

-

9.

Run the PCR products on a 1.5% agarose gel to confirm their size and sequence the correct one. The lengths of the PCR products of wild-type EcN and recombinant EcN are 1614 and 5304 bp, respectively (Figure 7).

-

10.

Next, add 500 μL 50% sterilized glycerin solution to 500 μL of the suspension containing the correct recombinant bacteria and store at −80°C. In our experiment, the recombinant EcN was named EcN-hlyBD-ACG-tag-LacZ.

Figure 7.

Screening of the recombinant clones by colony PCR

Preparation of electrocompetent EcN-hlyBD-ACG-tag-LacZ for pWT-AGBM transformation

Timing: 3 days

This step covers the preparation of electrocompetent EcN-hlyBD-ACG-tag-LacZ cells, transformation of pWT-AGBM plasmid into EcN-hlyBD-ACG-tag-LacZ, and selection of the correct transformants.

Preparation of electrocompetent cell for plasmid transformation

-

11.

Streak the EcN-hlyBD-ACG-tag-LacZ strain onto a plate containing 50 mg/mL kanamycin and then culture at 37°C for 12 h.

-

12.

Inoculate a single colony into 5 mL of LB media for 12 h (37°C, 220 rpm). Inoculate the culture in 50 mL of LB media (1:200) containing 50 mg/mL kanamycin to an OD600 of 0.3 (37°C, 220 rpm). Allow the culture to cool on ice for 10 min.

-

13.

Harvest the culture by centrifugation for 10 min at 4°C and 3000 rcf. Wash the cells three times with 30 mL ice-cold 10% glycerol to prepare electrocompetent cells.

-

14.

After washing three times, resuspend the culture in 1 mL of ice-cold 10% glycerol. Then transfer into 1.5 mL tubes (100 μL/tube) for DNA transformation.

Transformation

-

15.

Add 10–15 μL of pWT-AGBM plasmid (approximately 1.5–2 μg) to electrocompetent cells and incubate on ice for 10 min.

-

16.

Add the plasmid-cell mixture to a gapped cuvette.

-

17.

Electroporate the mixture at an electric field intensity of 3 kV (15 kV/cm) for 4 ms to transform the plasmids into electrocompetent cells.

-

18.

Resuspend the cells immediately after pulse with 800 μL of LB media and activate at 37°C for 1–1.5 h.

-

19.

Centrifuge the cultures at 6000 rcf for 1 min. Discard the supernatant (600 μL) and resuspend the cells. Spread the cultures on an agar plate containing 50 μg/mL streptomycin and incubate at 37°C for 12 h.

Selection of the cloning product containing the pWT-AGBM plasmid

Timing: 2 days

This step involves the selection of the cloning product containing the pWT-AGBM plasmid.

-

20.

Pick 5–10 colonies and add to 10 μL sterilized ddH2O; use 1 μL of the suspension to execute the colony PCR program (refer to step 8 in “before you begin” section). Add the remaining bacterial suspension to 5 mL of LB media containing 50 μg/mL streptomycin and culture at 37°C for 12 h.

-

21.

Run the PCR products on a 1.5% agarose gel to confirm their size and sequence the correct one. Add 500 μL 50% sterilized glycerin solution to 500 μL of the correct engineered bacterial suspension and store at −80°C; in our experiment, this strain was named i-ROBOT.

Note: The i-ROBOT strain is multifunctional with the following traits: (1) sensing inflammatory markers with high sensitivity for early diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), (2) recording IBD information and (3) responsively expressing and releasing drugs in situ in a self-tunable.

-

22.

Use the same method to obtain the control strain D57A, which contains the pWT-AGBM-D57A plasmid in the EcN-hlyBD-ACG-tag-LacZ chassis.

Diagnosis and record of DSS-induced mouse colitis by i-ROBOT

Timing: 8–9 days

This step includes the diagnosis and recording of thiosulfate in DSS-induced colitis in mice using i-ROBOT. The engineered i-ROBOT bacteria is administered to the mice, and the fecal and colon contents are collected. Next, the flora from fecal and colon contents is collected, and green fluorescence, base editing rate, and blue clone ratio of i-ROBOT contained in the contents are recorded (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

The flow chart of i-ROBOT diagnoses and record of DSS-induced mouse colitis

DSS-induced mouse colitis experiments

-

23.

Divide the mice into four groups, and administer 3% DSS for drinking to each group for 0, 1, 3, and 5 days (Figure 9). Weigh mice on day 0, 1, 3 and 5 for assessing the disease activity index (DAI).

Note: Before the experiments began, the mice were acclimated to the environment for one week. The animals were randomly allocated to each group.

-

24.

DAI assessment of each mouse on the day 0, 1, 3, 5.

CRITICAL: We suggest assess the DAI under the blind condition.

| Score | Weight loss (%) | Stool consistency | Blood in stool |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | None | Normal | Normal |

| 1 | 1–5 | Slightly loose stool | Small presence of blood |

| 2 | 5–10 | Loose stool | Significant presence of blood |

| 3 | 10–15 | Diarrhea | Gross blood |

| 4 | >15 | Diarrhea | Gross blood |

Figure 9.

Guide for four groups

The first group (group 1) of mice drink water freely for 5 days. The second group (group 2) of mice drink water freely for 4 days, and then drank 3% DSS freely for 1 day. The third group (group 3) of mice drink water freely for 2 days, and then drank 3% DSS freely for 3 days. The fourth group (group 4) of mice drink water freely for 5 days.

Bacteria preparation administration and sample preparation

-

25.Bacteria preparation.

-

a.Streak the i-ROBOT strain on a plate containing 50 mg/mL streptomycin and then culture at 37°C for 12 h, and inoculate a single colony into 5 mL of LB media for 12 h to activate the strain.

-

b.Inoculate the activated culture in a 24-well cell culture plate with 750 μL of LB media (1:200) containing 50 mg/mL streptomycin in 37°C with shaking at 1000 rpm for 8 h. Carry out this process in a microplate shaker.

-

c.Collect all cultures and wash with PBS twice.

-

d.Resuspend the i-ROBOT strain to 1 × 109 CFU/100 μL with PBS.

-

a.

CRITICAL: Readers should establish a standard curve for the correlation between i-ROBOT CFUs (by plating a dilution series) and OD600. Calculate the number of cultures by OD600, and then dilute to 1 × 109 CFU/100 μL.

-

26.Administer a total of 2 × 109 CFU (200 μL) of i-ROBOT to each mouse on the fifth day.

-

a.Stabilize the mouse by holding its head, neck and back.

-

b.Keep mouse lower jaw and neck at 180°, to make sure the esophagus is unobstructed.

-

c.Inject the gavage needle (8#45 mm) from mouth, keep the needle moving in parallel with the esophagus of mouse and then inject 200 μL bacteria.

-

a.

-

27.Sample preparation.

-

a.Collect the fecal over a 6–12 h period after bacterial gavage and euthanize the mice to get the colon contents at 12 h after bacterial gavage. Transfer the fecal and colon contents to a 2 mL centrifuge tube with two steel grinding beads (3 mm).

CRITICAL: Six h after gavage, all mice were assigned to separate cages to collect feces from individual mice. Removing the padding can make it more convenient to collect feces.

CRITICAL: Six h after gavage, all mice were assigned to separate cages to collect feces from individual mice. Removing the padding can make it more convenient to collect feces. -

b.Add 1.5 mL of ice-cold PBS (containing 1 mg/mL chloramphenicol) to the tube (20 mg sample/mL PBS).Note: High concentration of chloramphenicol is used to halt protein translation.

-

c.Use the “high-speed low-temperature tissue homogenizer” (KZ-III-F, Servicebio, Hubei, China) to homogenize samples. The instructions are as follows: http://shopobs.servicebio.cn/2022/04/01/1648813395478380977.pdf.Note: Readers can also use glass beads or other beads if sufficient grinding can be performed by other vortex means.

-

d.Filter the vortexed samples through a 5-μm syringe filter to remove large debris.Note: Readers can dilute the samples to allow them to pass easily through the filter.

-

e.Centrifuge and wash the filtered samples at 4°C. Resuspend the precipitate in ice-cold PBS containing 1 mg/mL chloramphenicol.

-

a.

Flow cytometry

-

28.

Transfer 750 μL of the prepared sample into a 24-well cell culture plate (standard microplate), incubate in a microplate shaker (37°C, 1000 rpm) for 2 h to maturate the green fluorophores, and then transfer to a 4°C refrigerator, or analyze the intensity of green fluorescence by flow cytometry immediately.

Note: We recommend that readers analyze fluorescence by flow cytometry less than 12 h after sample collection.

-

29.

Perform flow cytometry analysis using a CytoFLEX S flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) with blue (488 nm, 30 mW) and yellow (561 nm, 50 mW) lasers.

-

30.

Perform the first gating (P1) according to the FSC/SSC scatter characteristics of the i-ROBOT.1

-

31.

Perform the second gating (P2) according to the red fluorescence intensity of i-ROBOT to ignore counts with low red fluorescence.1

-

32.

Analyze a total of 30,000 events or 600 s within the gated population.

Note: Before analysis, dilute the sample properly to avoid blocking the flow cytometer.

Analysis of records

-

33.

Inoculate the prepared sample (obtained in step 32) in 750 μL of LB media (1:50) containing 50 mg/mL streptomycin at 37°C (1000 rpm) for 12 h.

-

34.

Collect and wash the culture.

-

35.

Serially dilute the culture, spread on an X-gal agar plate, and culture at 37°C. After 12 h, count the numbers of blue and white colonies.

-

36.

Add 1 μL of culture and 1 μL of uninduced i-ROBOT (as an unmodified reference) to the colony PCR system (refer to step 8 in “before you begin” section).

Note: Use Sequalizer-F as the upstream primer and Sequalizer-R as the downstream primer.

-

37.

Sequence the PCR products using the Sequalizer-F primer to obtain Sanger chromatogram signals.

-

38.

Use Sequalizer9 to calculate the difference between a sample and an unmodified reference to identify the base-editing ratio (Software: MATLAB R2018a).

Amelioration of disease activity in mice with DSS-induced colitis by i-ROBOT

Timing: 15–20 days

This step includes the amelioration of disease activity in colitis mice by i-ROBOT (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

The flow chart of i-ROBOT ameliorates disease activity in mice with DSS-induced colitis

Bacteria preparation and DSS-induced mouse colitis experiments

-

39.Bacteria preparation.

-

a.Streak the i-ROBOT and D57A strains on a plate containing 50 mg/mL streptomycin and culture at 37°C for 12 h. Inoculate a single colony into 5 mL of LB media for 12 h to activate the strain.

-

b.Inoculate the activated culture in 30 mL of LB media (1:200) containing 50 mg/mL streptomycin at 37°C (220 rpm) for 8 h.

-

c.Collect all cultures and wash twice with PBS.

-

d.Resuspend the i-ROBOT strain to 5 × 109 CFU/100 μL with PBS.

-

a.

-

40.Divide the mice into four groups (Figure 11).

-

a.Allow the first group (named “PBS (DSS-)”) of mice to drink water freely for 8 days. Administer 200 μL PBS daily to the mice.

-

b.Allow the second group (named “PBS (DSS+)”) of mice to drink water freely for 3 days and 3% DSS for 5 days. Administer 200 μL PBS daily to the mice.

-

c.Allow the third group (named “D57A (DSS+)”) of mice to drink water freely for 3 days and 3% DSS for 5 days. Administer 200 μL of D57A strain (1 × 1010 CFUs) to the mice daily.

-

d.Allow the fourth group (named “i-ROBOT (DSS+)”) of mice to drink water freely for 3 days and 3% DSS for 5 days. Administer 200 μL of i-ROBOT strain (1 × 1010 CFU) to the mice daily.

-

a.

Figure 11.

Guide for four groups

The first group of mice to drink water freely for 8 days and administer 200 μL PBS daily to the mice. The second group of mice to drink water freely for 3 days, 3% DSS for 5 days and administer 200 μL PBS daily to the mice. The third group of mice to drink water freely for 3 days, 3% DSS for 5 days and administer 200 μL of D57A strain (1 × 1010 CFU) to the mice daily. The fourth group of mice to drink water freely for 3 days, 3% DSS for 5 days and administer 200 μL of i-ROBOT strain (1 × 1010 CFU) to the mice daily.

Analysis of therapeutic efficacy

-

41.

Record the weight of mice every day.

-

42.

Assess the DAI of mice on day 8.

-

43.

Perform cervical dislocation to euthanize the mice, and dissect the colon, put it on ice, and measure the length.

Note: Autoclave the scissors and tweezers before you start.

-

44.

Gently rinse the colon surface with PBS.

-

45.Divide the distal colon close to the rectum into three parts (approximately 1 cm each).

-

a.Fix the part closest to the rectum (it may contain part of rectal tissue) with 4% paraformaldehyde at 20°C–25°C for 24 h.

-

b.Freeze the middle part in liquid nitrogen and store at −80°C for cytokine detection.

-

c.Freeze the part near the cecum in liquid nitrogen and store at −80°C.

-

a.

Histological studies

-

46.Hematoxylin-eosin staining (HE staining).

-

a.Embed the fixed colonic samples in paraffin, section (5 μm) them, and stain with hematoxylin and eosin. The instructions are as follows: https://www.servicebio.com/data-detail?id=5590&code=RSSYBG.

-

b.Observe with microscopic inspection, image acquisition and analysis.

-

a.

-

47.Masson staining and fibrosis analysis.

-

a.Embed the fixed colonic samples in paraffin, section (5 μm) them, and stain with Masson’s dye solution.

-

b.Observe with microscopic inspection, followed by image acquisition and analysis.

-

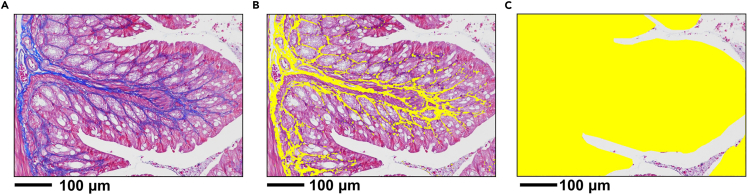

c.Use an Eclipse Ci-L photographic microscope to image the selected area (200x) as shown in Figure 12A.Note: During imaging, ensure that the tissue fills the entire field of vision and that the background light of each photo is consistent.

- d.

-

e.The proportion of positive area (%) = collagen pixel area/tissue pixel area × 100.

-

a.

-

48.Analysis of cytokines in animal tissues.

-

a.Homogenize the middle part of the colon (100 mg tissue/100 μL ice-cold PBS or ice-cold physiological saline).

-

b.Centrifuge homogenized samples at 3000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min and transfer the supernatants to new tubes.

-

c.Use ELISA cytokine detection kits for cytokine detection. Follow the instructions: https://www.sangon.com/productImage/DOC/D721022/D721022_ZH_P.pdf.

-

a.

Note: Carry out three repeated experiments on each sample.

Figure 12.

Masson staining for detecting fibrosis in sections

(A) Image of Masson staining.

(B) Area of collagen pixel.

(C) Area of tissue pixel.

Expected outcomes

In this protocol, we describe a detailed method for designing and constructing an intelligent probiotic i-ROBOT containing three key modules (fluorescence reporting, a base-editing system, and drug secretion) for diagnosing, recording, and ameliorating inflammatory bowel disease in mice.

After oral administration, we analyzed the ability of i-ROBOT to diagnose and record colitis in mice. i-ROBOTs isolated from inflamed mice (3% DSS treatment for 3 and 5 days) showed higher green fluorescence intensity (Figures 13A and 13B), base-editing ratios (Figures 13C and 13D), and blue clone ratios (Figures 13E and 13F) than that of those isolated from healthy mice (3% DSS treatment for 0 days).

Figure 13.

Diagnoses and records of DSS-induced mouse colitis by i-ROBOT (Adapted from1)

(A) Measurement of the fluorescence intensity of engineered bacteria in fecal samples by flow cytometry (mean ± SEM; n = 5; individual dots represent individual mice; statistical significance was determined by an unpaired two-tailed t test; ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001).

(B) Measurement of the fluorescence intensity of engineered bacteria in colon content samples by flow cytometry (mean ± SEM; n = 5; individual dots represent individual mice; statistical significance was determined by an unpaired two-tailed t test; ∗∗p ≤ 0.01).

(C) Results of the sequencing of the engineered bacteria in fecal samples (mean ± SEM; n = 5; individual dots represent individual mice; statistical significance was determined by an unpaired two-tailed t test; ∗∗p ≤ 0.01).

(D) Results of the sequencing of the engineered bacteria in colon content samples (mean ± SEM; n = 5; individual dots represent individual mice; statistical significance was determined by an unpaired two-tailed t test; ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01).

(E) Results of the plate counting of the engineered bacteria in fecal samples (mean ± SEM; n = 5; individual dots represent individual mice; statistical significance was determined by an unpaired two-tailed t test; ∗∗p ≤ 0.01).

(F) Results of the plate counting of the engineered bacteria in colon content samples (mean ± SEM; n = 5; individual dots represent individual mice; statistical significance was determined by an unpaired two-tailed t test; ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001).

Daily oral administration of i-ROBOT ameliorated disease activity (Figure 14A), weight loss (Figure 14B), and reduction of colon length (Figure 14C) in mice colitis model. Compared to that in the disease group, less inflammatory cell infiltration and satisfactory colorectal integrity were observed in the i-ROBOT treatment group (Figure 14D). In addition, compared to that in the disease group, i-ROBOT reduced the inflammatory factor level, and there was no significant difference from that in healthy mice (Figures 14E–14I).

Figure 14.

i-ROBOT ameliorates DSS-induced colitis in mice (Adapted from1)

(A) DAI on the fifth day of DSS administration (mean ± SEM; n ≥ 4; individual dots represent individual mice; statistical significance was determined using an unpaired two-tailed t-test; ∗p ≤ 0.05).

(B) Weight change of the mice in each group (mean ± SEM; n ≥ 4; individual dots represent individual mice; statistical significance was determined using an unpaired two-tailed t-test; ∗p ≤ 0.05).

(C) Colon length of each group of mice (mean ± SEM; n ≥ 4; individual dots represent individual mice; statistical significance was determined using an unpaired two-tailed t-test; ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001).

(D) Histological images of distal colon sections from each experimental group stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Red arrows: multifocal mucosal necrosis with disappearance of the glands and goblet cells. Black arrows indicate glandular atypia. Yellow arrow: lymphocytic infiltration and inflammation invading the submucosa. White arrow: repair of connective tissue hyperplasia. Green arrows: multifocal edema of the submucosa with loose connective tissue and vasodilation with few lymphocytes.

(E–I) Determination of the levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-17A, and MCP-1 in the colon samples of mice in each group by ELISA (mean ± SEM; n ≥ 4; individual dots represent individual mice; statistical significance was determined by an unpaired two-tailed t-test; n.s. p > 0.05, ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01).

Limitations

The thiosulfate-responsive genetic circuits constructed using this protocol exhibited satisfactory sensing performance in the EcN strain. However, we did not test this genetic circuit in other bacteria, except E. coli DH5α. Although both EcN1 and DH5α10 belong to Escherichia coli, their genetic circuits exhibit different performances. Therefore, we propose to consider some key points when applying thiosulfate-responsive sensors to other bacterial strains: 1. Codon optimization of sensing elements (ThsS/ThsR). 2. Validation of the strength of the promoter and Ribosome binding site (RBS) for ThsS and ThsR in other strains.

We used a DSS-induced mouse model, one of the most widely used colitis models, to test the functions of i-ROBOT. We did not apply this protocol to other colitis models, such as Salmonella typhimurium-induced11 and TNBS-induced models.12 Nevertheless, i-ROBOT has the potential to become a valuable diagnostic and therapeutic tool for other colitis models if increased thiosulfate is generated in these colitis models.

Troubleshooting

Problem 1

Inability to obtain colonies after EcN-hlyBD-ACG-tag-LacZ transformation (steps 15–19).

Potential solution

-

1.

Increase the concentration of the pWT-AGBM plasmid.

-

2.

Try the electric shock twice at 3 kV (15 kV/cm) for 4 ms.

-

3.

Culture the plates at 37°C for longer time.

Problem 2

Feces (loose stool or diarrhea) of colitis mice are difficult to isolate from the cages (step 34).

Potential solution

Rinse the stool gently with ice-cold PBS and transfer all suspended solids into a tube.

Problem 3

Vortexed samples cannot pass through a 5-μm syringe filter (step 27).

Potential solution

Dilute the samples to allow easy passage through a filter, centrifuge, and concentrate to the required concentration.

Problem 4

Too many or too few colony-forming units on an X-gal agar plate (step 35).

Potential solution

We recommend estimating these records by counting 80–500 blue and white colony-forming units on an X-gal agar plate. Readers can establish a standard curve for the correlation between i-ROBOT CFUs and OD600.

Problem 5

Failure to detect tissue cytokines (step 48).

Potential solution

The levels are lower than the lower detection limit: 1. Samples should be stored at −80°C and assayed within 2 weeks to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. 2. Reduce the volume of PBS used for homogenization. 3. Add protease inhibitors to PBS.

The levels are higher than the upper detection limit: dilute samples.

We recommended that all standards and samples be assayed in duplicate at least.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Bang-Ce Ye (bcye@ecust.edu.cn).

Materials availability

All requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact (bcye@ecust.edu.cn). All reagents including bacteria and plasmid may be available on request after completion of a Materials Transfer Agreement.

Acknowledgments

This work was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22134003) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2020YFA0908800).

Author contributions

Z.-P.Z., Y.Z., and B.-C.Y. designed the experiments. Z.-P.Z., Y.-H.F., and W.D. wrote the paper. Z.-P.Z., Y.D., and T.-T.F. contributed to the general methodology. Y.Z. and B.-C.Y. revised the paper and provided funding support.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Ying Zhou, Email: zhouying@ecust.edu.cn.

Bang-Ce Ye, Email: bcye@ecust.edu.cn.

Data and code availability

This study did not generate/analyze datasets/code.

References

- 1.Zou Z.P., Du Y., Fang T.T., Zhou Y., Ye B.C. Biomarker-responsive engineered probiotic diagnoses, records, and ameliorates inflammatory bowel disease in mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2023;31:199–212.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2022.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Datsenko K.A., Wanner B.L. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy K.C. Use of bacteriophage lambda recombination functions to promote gene replacement in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:2063–2071. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.8.2063-2071.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zou Z.P., Ye B.C. Long-Term rewritable report and recording of environmental stimuli in engineered bacterial populations. ACS Synth. Biol. 2020;9:2440–2449. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.0c00193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson R.C., Blankenship J.R., Kraus P.R., de Jesus Berrios M., Hull C.M., D'Souza C., Wang P., Heitman J. A PCR-based strategy to generate integrative targeting alleles with large regions of homology. Microbiology. 2002;148:2607–2615. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-8-2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bryksin A.V., Matsumura I. Overlap extension PCR cloning: a simple and reliable way to create recombinant plasmids. Biotechniques. 2010;48:463–465. doi: 10.2144/000113418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daeffler K.N.M., Galley J.D., Sheth R.U., Ortiz-Velez L.C., Bibb C.O., Shroyer N.F., Britton R.A., Tabor J.J. Engineering bacterial thiosulfate and tetrathionate sensors for detecting gut inflammation. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2017;13:923. doi: 10.15252/msb.20167416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang W., Liu D.R. Rewritable multi-event analog recording in bacterial and mammalian cells. Science. 2018;360:eaap8992. doi: 10.1126/science.aap8992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farzadfard F., Gharaei N., Higashikuni Y., Jung G., Cao J., Lu T.K. Single-nucleotide-resolution computing and memory in living cells. Mol. Cell. 2019;75:769–780.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang T.T., Zou Z.P., Zhou Y., Ye B.C. Prebiotics-controlled disposable engineered bacteria for intestinal diseases. ACS Synth. Biol. 2022;11:3004–3014. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.2c00182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riglar D.T., Giessen T.W., Baym M., Kerns S.J., Niederhuber M.J., Bronson R.T., Kotula J.W., Gerber G.K., Way J.C., Silver P.A. Engineered bacteria can function in the mammalian gut long-term as live diagnostics of inflammation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017;35:653–658. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott B.M., Gutiérrez-Vázquez C., Sanmarco L.M., da Silva Pereira J.A., Li Z., Plasencia A., Hewson P., Cox L.M., O'Brien M., Chen S.K., et al. Self-tunable engineered yeast probiotics for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Med. 2021;27:1212–1222. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01390-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This study did not generate/analyze datasets/code.