Abstract

Genetic code expansion has pushed protein chemistry past the canonical 22 amino acids. The key enzymes that make this possible are engineered aminoacyl tRNA synthetases. However, as the number of genetically encoded amino acids has increased over the years, obvious limits in the type and size of novel side chains that can be accommodated by the synthetase enzyme become apparent. Here, we show that chemically acylating tRNAs allow for robust, site-specific incorporation of unnatural amino acids into proteins in zebrafish embryos, an important model organism for human health and development. We apply this approach to incorporate a unique photocaged histidine analogue for which synthetase engineering efforts have failed. Additionally, we demonstrate optical control over different enzymes in live embryos by installing photocaged histidine into their active sites.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

While natural protein biosynthesis relies on the common 20 amino acids, addition of amino acids with unique chemical structures, such as photocages, bioorthogonal ligation handles, and photo-cross-linkers, to the genetic code provides fundamentally new function to proteins.1–4 Genetic code expansion is usually accomplished by introducing an orthogonal aminoacyl tRNA synthetase/tRNA pair that has been evolved to recognize and charge an unnatural amino acid (UAA) onto the tRNA, which then delivers the UAA in response to an amber stop codon during ribosomal protein synthesis.4,5 While this approach has been highly successful in introducing many unique and diverse UAAs into proteins in pro- and eukaryotic cells, as well as in animals,5,6 the size and structural complexity of the UAAs is fundamentally restricted by the aminoacyl tRNA synthetase binding pocket.7–10 Bypassing the synthetase by direct chemical acylation of the tRNA with a UAA overcomes this limitation. In fact, chemically acylated tRNAs and their use for UAA incorporation into proteins in vitro was first reported in 1989 by the Schultz group.11 To conduct these experiments in cells, delivery of the acylated tRNA represents an obstacle that was solved through injection into large frog oocytes.12,13

Surprisingly, the utilized oocytes have always been unfertilized, limiting the complexity of the system and of the biological studies. Here, we demonstrate for the first time that injection of chemically acylated tRNA into fertilized zebrafish oocytes results in robust UAA incorporation into proteins during embryo development that is comparable to enzymatic genetic code expansion in this model organism. Furthermore, we exploit direct chemical acylation to incorporate a photocaged histidine, a new UAA that has failed synthetase selections and screens for genetic code expansion.14 We demonstrate optical control of distinct histidine functions in different enzymes expressed in zebrafish embryos. Placing proteins under optical control with photocaged UAAs is complemented by the transparency of the zebrafish embryo during early development, enabling activation of protein function through brief light exposure.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

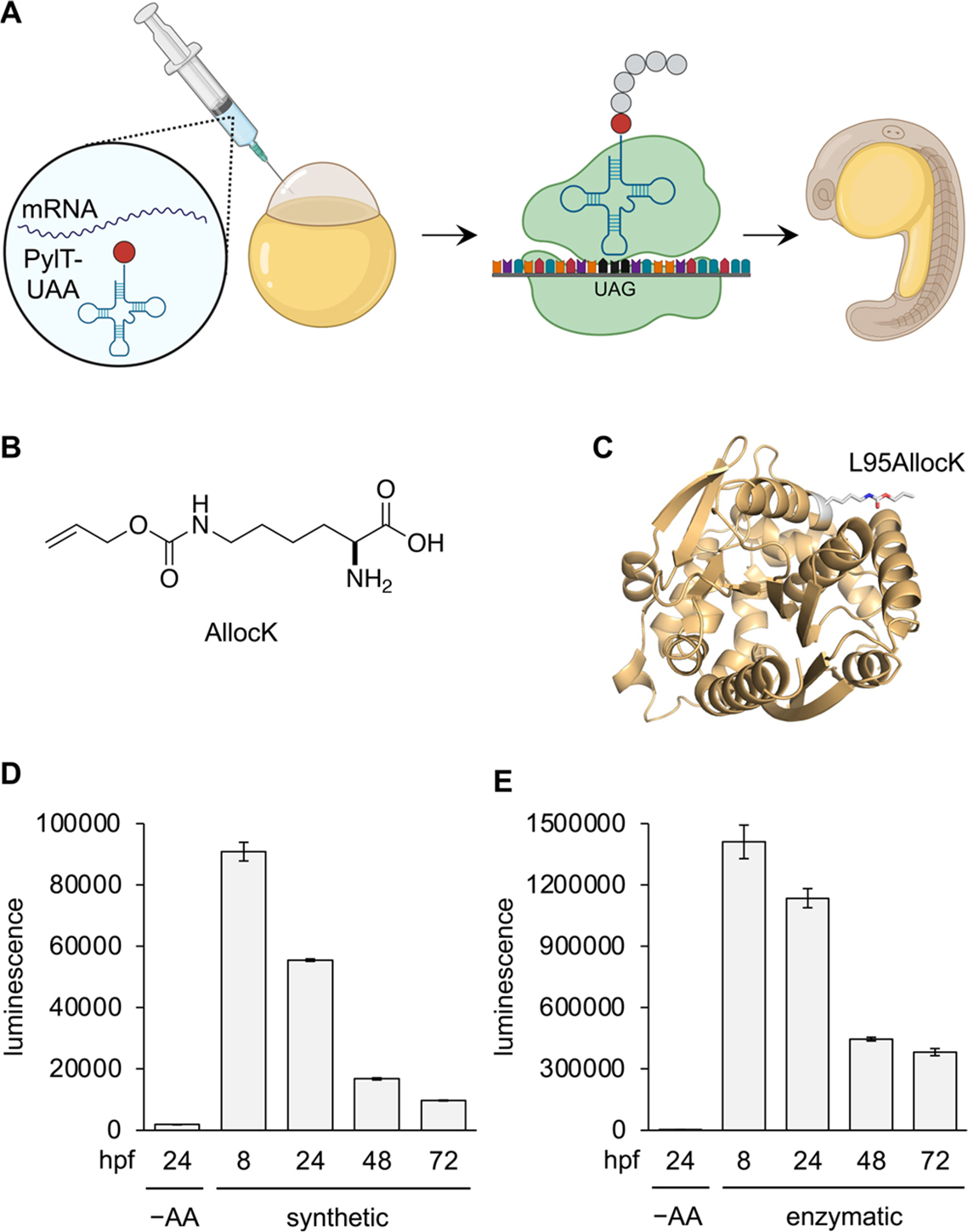

We first wanted to test whether injection of chemically acylated tRNAs in developing embryos is a viable method for amber stop codon suppression and expression of sufficient quantities of protein (Figure 1A). For the tRNA, we chose to use the archaeal pyrrolysyl tRNA from Methanosarcina barkeri (PylT) since it has been shown to be orthogonal to endogenous zebrafish tRNA synthetases,6,15–18 meaning there is no enzymatic acylation occurring that could lead to detectable incorporation of canonical amino acids at amber stop codon sites. Alloc-lysine (AllocK, Figure 1B) has previously shown good amber stop codon suppression through enzymatic genetic code expansion in zebrafish embryos15 and thus was our first UAA of choice for chemical installation on PylT and subsequent incorporation into protein in zebrafish embryos. A standard synthetic protocol was followed for PylTAllocK synthesis through chemical acylation.19 First, the amino group is protected by an acid-labile Boc group, and the acid is activated as a cyanomethyl ester, which then mono-acylates the ribose 2′ or 3′ OH of the dinucleotide pdCpA. Chromatographic separation of the two regioisomers is not needed as they rapidly interconvert in an aqueous solution.20 Following deprotection, the acylated dinucleotide is then enzymatically ligated to the remainder of the tRNA oligonucleotide to produce a translationally competent acylated tRNA. The chemically acylated PylTAllocK was suspended in sodium acetate buffer (5 mM) at pH 5, since an acidic environment reduces hydrolysis of the acyl bond.21 A Renilla luciferase reporter was used to assess incorporation of AllocK, with a permissive surface residue mutated to an amber stop codon (rLuc L95TAG, Figure 1C).15 We inserted this construct and all other reporters and genes of interest into the pCS2 vector (Supporting Information, Figure S1), commonly used as a template for in vitro transcription for mRNA generation. mRNA for this construct was co-injected into zebrafish embryos at one cell stage along with either PylTAllocK or non-acylated PylT (Figure 1A). As a benchmark for amber stop codon suppression, we compared these results to the incorporation of AllocK using co-expression of the wild-type PylT and PylT synthetase, which has shown the highest levels of UAA incorporated protein in embryos.15 After injection, embryos were incubated at 28.5 °C and lysates were collected at 8, 24, 48, and 72 hours post-fertilization (hpf), followed by assays for luciferase expression (Figure 1D,E). The non-acylated PylT injection showed no significant luciferase activity, validating the bioorthogonality of the tRNA. Gratifyingly, PylTAllocK injection resulted in high protein expression levels, though less than enzymatic tRNA acylation in the animal, as we expected. For this reporter, protein production peaked at 8 hpf but persisted until 72 hpf. This temporal course of expression is likely linked to the decay of the injected mRNA and PylT over time and the short protein half-life (about 4 h in mammalian cells) of the luciferase protein.22 The major difference between the two approaches is that enzymatic acylation of PylT can continue during the life of the synthetase and tRNA, while the chemically acylated route introduces a fixed amount of acylated PylT. Thus, we expected incorporation of the chemically acylated PylT to produce less protein. We also assessed the ability for chemically acylated PylT to suppress multiple stop codons in the same transcript (V47TAG and V70TAG), which turned out to be as efficient as genetic code expansion through expression of the tRNA synthetase enzyme, although compared to single amber stop codon suppression, protein levels were significantly reduced (Supporting Information, Figure S2). In conclusion, chemically acylating a UAA to PylT is a viable route for site-specific incorporation into proteins in zebrafish embryos.

Figure 1.

Chemically acylated tRNAs are functional in zebrafish embryos and enable site-specific incorporation of UAAs into proteins. (A) Amber stop codon suppression with a chemically acylated tRNA in zebrafish embryos. (B) Chemical structure of AllocK. (C) Protein structural representation of AllocK incorporation into the protein surface site 95 of rLuc (PDB: 2PSJ). (D,E) Incorporation of AllocK into the rLuc L95TAG reporter for up to 72 h using either chemically acylated tRNA (synthetic) or through expression of the tRNA synthetase in embryos (enzymatic). Bars represent averages from triplicate (4 pooled embryos/sample) and error bars indicate standard deviation. –AA: no AllocK or non-acylated tRNA control.

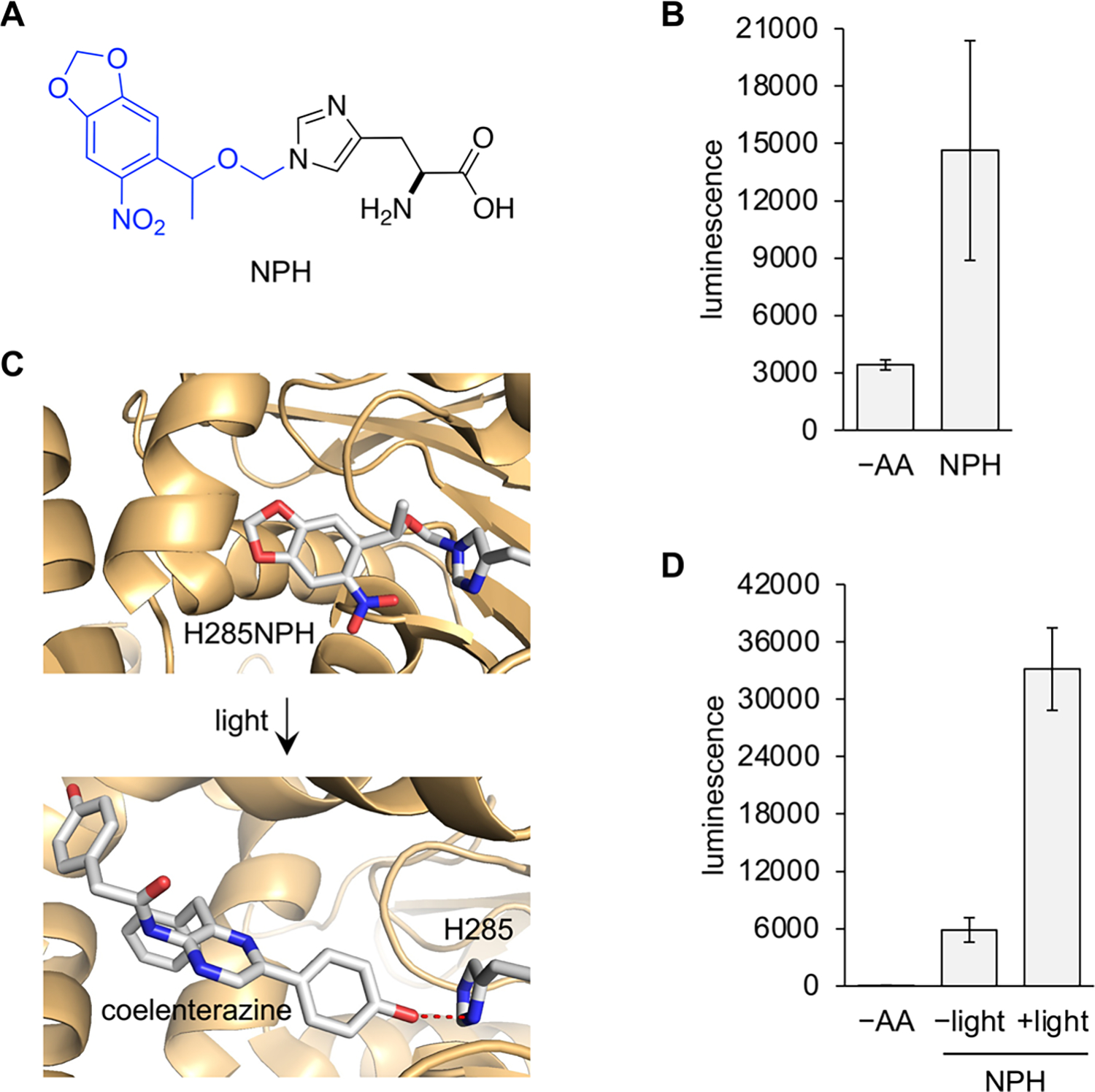

Genetic code expansion has enabled incorporation of several unique and useful UAAs, but many fail to incorporate efficiently enough for robust protein expression, despite numerous attempts at synthetase selections and engineering. One such UAA is NPOM-histidine (NPH, Figure 2A),14 a photocaged variant of histidine that would have broad applicability for optical control of enzymes that rely on histidine for catalysis.23,24 The NPOM photocaging group, which relies on an oxymethylene linkage to the heterocyclic nitrogen, has been shown to effectively cage histidine, while carbamate linkages at the heterocylic amine are unstable to aqueous conditions.14,25 The NPOM group can be removed with 405 nm light and has greatly improved decaging kinetics relative to other ortho-nitrobenzyl photocages installed on nitrogen heterocycles.26

Figure 2.

Incorporation of photocaged histidine using chemically acylated PylT and optical activation of enzyme function. (A) Chemical structure of photocaged histidine (NPH). The blue portion is removed after 405 nm light irradiation. (B) Incorporation of NPH into the rLuc 95TAG reporter. (C) Protein structural representation of NPH incorporation into the substrate binding site for rLuc (PDB: 2PSJ). Hydrogen bonding is indicated by red dashes. (D) Incorporation of NPH at site 285 and activation of rLuc activity with 405 nm light (2 min). Bars represent averages from triplicate (4 pooled embryos/sample), and error bars indicate standard deviation. –AA: nonacylated tRNA control. NPH: NPH acylated tRNA.

PylT was acylated with NPH, and its incorporation into proteins in zebrafish embryos was first assessed with the rLuc L95TAG reporter again. Embryo lysates were collected at 24 hpf, and the luminescence readout demonstrated significant incorporation above background (Figure 2B), albeit lower than that of AllocK. The reason for this is unknown but may be due to different binding affinities to EF1a, which is essential to stabilizing the acyl bond and directing the tRNA to the ribosome.27

In order to test the ability of NPH to optically control protein function in embryos, a histidine known to hydrogen-bond to coelenterezine in the rLuc substrate pocket was mutated to the amber stop codon (H285TAG, Figure 2C). Although mutation to alanine at this site still retained 11% activity compared to wild-type enzyme,28 we suspected the extra steric bulk of the NPOM group to not only block H-bonding but also further disrupt substrate binding. Injection of the PylTNPH and rLuc H285UAG mRNA was conducted under a red light filter, and embryos were incubated in the dark to eliminate any potential for background decaging of NPH. At 24 hpf, live embryos expressing rLuc 285NPH were irradiated with 405 nm light (LED), followed by lysis and luminescence readout. The irradiated samples showed ~6-fold increase in enzymatic activity over non-irradiated samples (Figure 2D). The non-irradiated condition had rLuc activity above the –AA background, likely related to the aforementioned mutational tolerance at site 285. An irradiation timecourse was conducted next, showing that enzyme function could be tuned through the duration of irradiation and that rLuc activity plateaued after 1 min of light exposure (Supporting Information, Figure S3). Extended irradiation beyond what is needed for complete decaging of NPH resulted in a decrease in luciferase activity, possibly due to photodegradation of the enzyme.

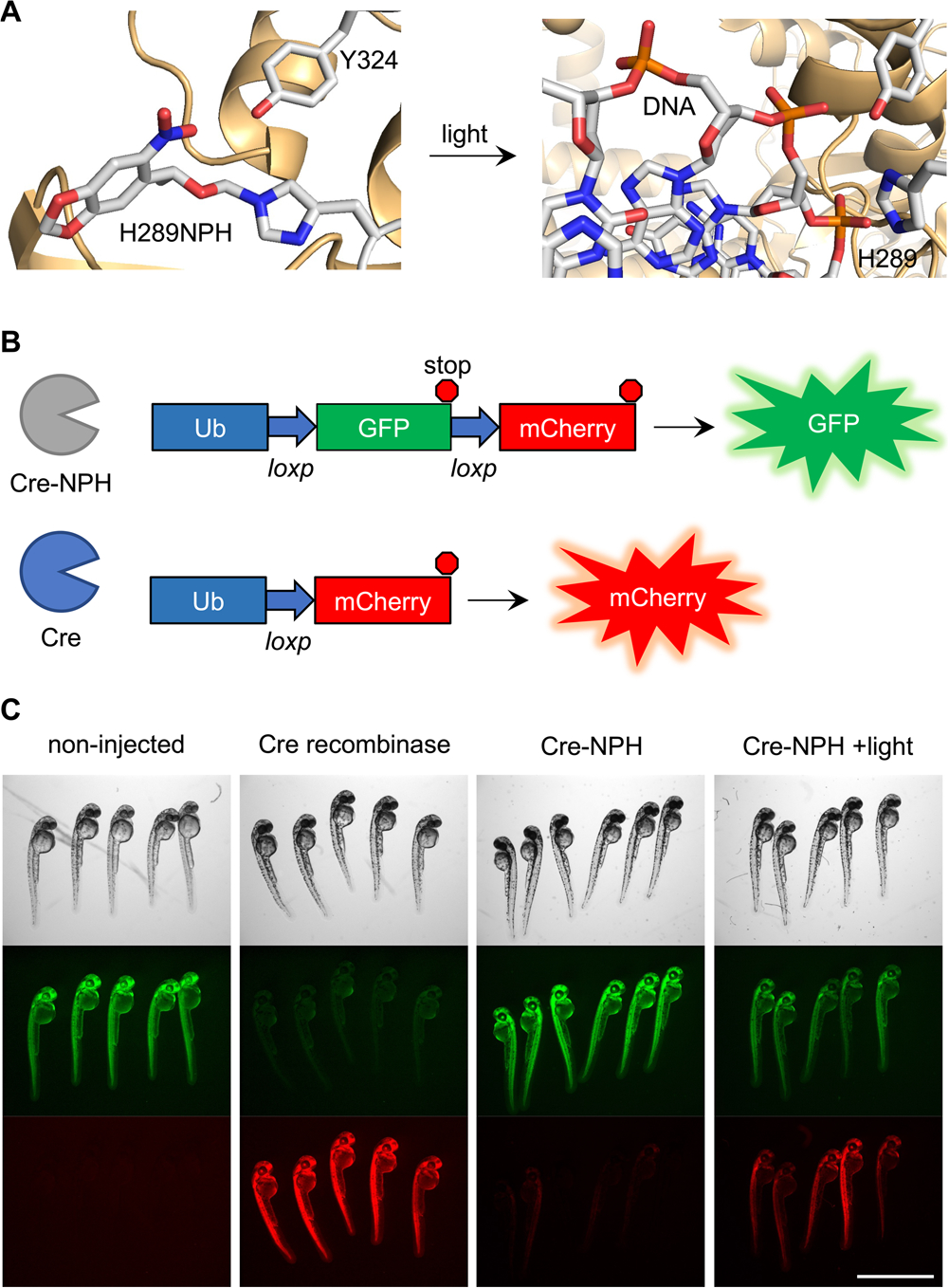

To further validate the ability to photocage enzymes via incorporation of NPH into protein in zebrafish embryos, we turned to Cre recombinase. The active site of this enzyme has a conserved histidine (H289) that, while not directly involved in catalysis, cannot be mutated to bulky aromatic residues without suffering loss of activity likely due to its position in the DNA binding site and proximity to the nucleophilic tyrosine Y324 (Figure 3A).29 We made the H289TAG mutant and coinjected mRNA with PylTNPH into a Cre recombinase reporter transgenic fish line.30 The embryos express EGFP flanked by loxP sites under a ubiquitin promotor, which upon recombination via Cre recombinase, removes EGFP and its stop codon and allows expression of mCherry instead (Figure 3B). Embryos expressing Cre recombinase 289NPH (Cre-NPH) were irradiated with 405 nm light at 5 hpf to activate the enzyme, and were imaged at 48 hpf (Figure 3C). We chose to irradiate at 5 hpf to allow enough time for expression of the caged Cre recombinase while simultaneously activating Cre recombinase during an early stage where fewer recombination events are necessary for whole-embryo expression of mCherry. This timepoint was chosen based on results from PylRS-mediated incorporation of caged amino acids.16 Non-injected embryos had bright EGFP fluorescence and showed no presence of mCherry, while the wild-type Cre recombinase expression condition led to strong mCherry fluorescence and no detectable EGFP, validating the function of the assay. Cre-NPH expression had similar fluorescence patterns as the non-injected embryos, and the photoactivation of Cre-NPH expressing embryos displayed good mCherry fluorescence. This suggests excellent activation of Cre-NPH with light exposure and minimal background activity in the non-irradiated samples, supporting the stability of NPH in embryos and its facile decaging. mCherry fluorescence was also quantified and verified this (Supporting Information, Figure S4). EGFP fluorescence is still seen in the irradiated Cre-NPH sample since Cre recombinase activity was triggered at 5 hpf; thus, EGFP expressed before recombination will remain, and overall recombination may be lower than what is observed after wild-type mRNA injection because recombination must take place in thousands of cells at the 5 hpf timepoint, rather than just a few cells right after injection.16 Of note, after irradiation, PylTNPH is also decaged to PylTHis and can still be incorporated at the amber stop codon. Thus, expression of active enzyme can occur until PylTHis is consumed or degraded. Because photo-decaging represents an irreversible on-switch and is much faster than protein translation, we do not expect this to impact time-resolved studies of protein function.

Figure 3.

Optical control of Cre recombinase activity with photocaged histidine. (A) Protein structural representation of NPH incorporation into the active site (PDB: 1NZB). (B) Schematic of the transgenic fish line fluorescent reporter used to detect Cre recombinase activity. (C) Images of embryos at 48 hpf. Irradiation of the Cre-NPH expressing embryos was conducted at 5 hpf. Scale bar = 2 mm.

In addition to hydrogen bonding and providing steric constraint, histidine also often acts as a general base in many enzymatic processes. Proteases, for example, rely on a histidine residue to deprotonate an active site serine or cysteine and activate it for nucleophilic attack of the protein substrate backbone.31–33 Conditional control of proteases allow for regulation of target protein inactivation or subcellular localization in live cells.2 We sought to optically control the single chain variant viral protease from the hepatitis C virus (HCVp) by replacing the general base in the active site, histidine H57, with NPH (Figure 4A,B).34,35 HCVp has been optically controlled using Dronpa domains or PhoCl to achieve protein cleavage in mammalian cells.36,37 This can be used to selectively degrade a protein or to control protein localization with removal of a signaling peptide. However, these approaches require fusion of protein domains or inhibitor strands that may not be readily generalizable to any protease. We endeavored to demonstrate a universal method for optical control of protease function using NPH incorporation into HCVp and the first demonstration of its photoactivation in an aquatic embryo.

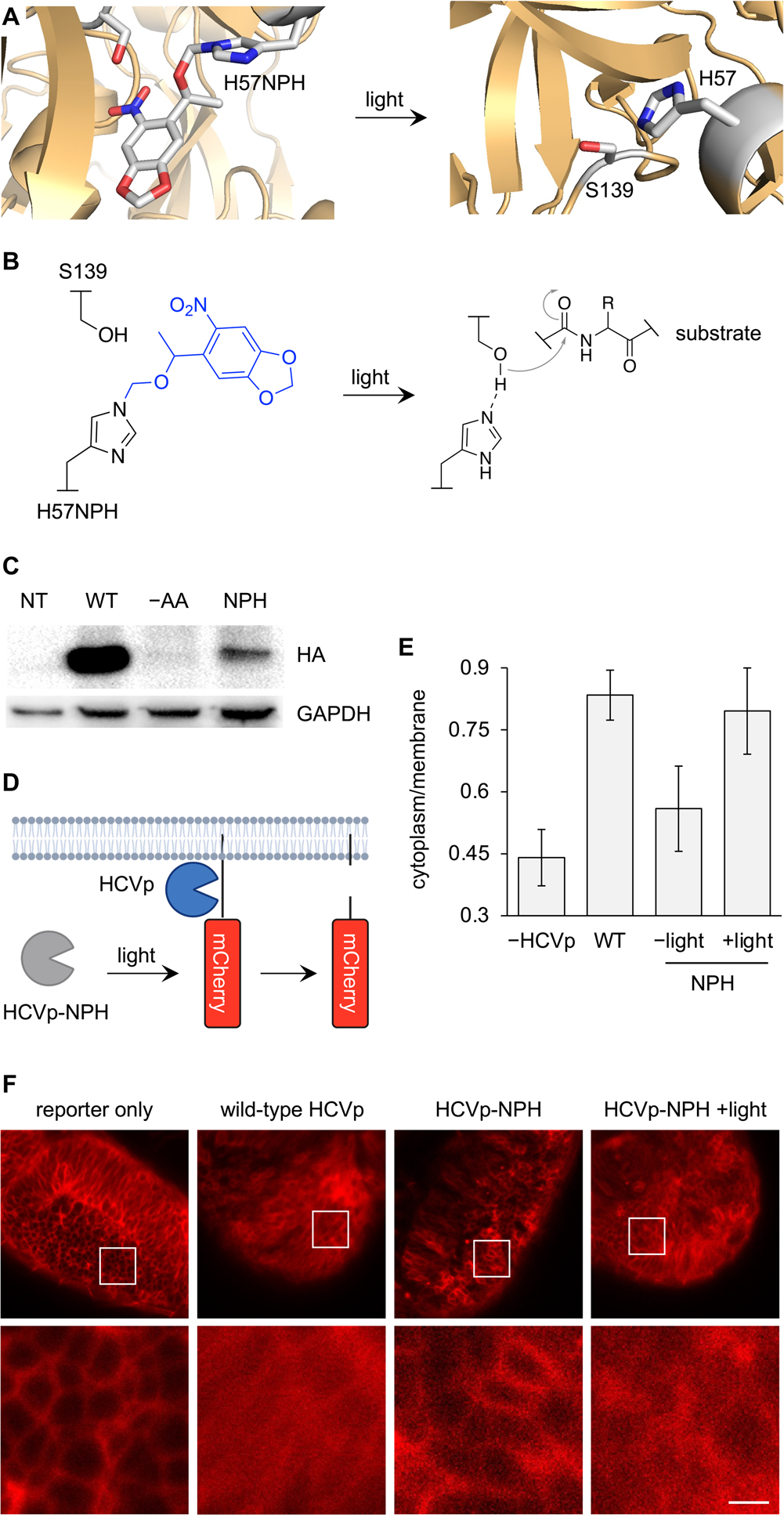

Figure 4.

Optical control of protease function in zebrafish embryos. (A) Structural representation of NPH incorporation into the HCVp active site (PDB: 1NS3). (B) Mechanistic diagram of HCVp proteolysis. (C) Western blot of NPH incorporation into HCVp with a C-terminal HA tag. (D) Cartoon of the fluorescent membrane translocation reporter for HCVp. (E) Quantification of the cytoplasm/membrane ratio of mCherry fluorescence in 24 hpf embryos. Bars represent averages (from 10 cells), and error bars represent standard deviation. (F) Confocal images of 24 hpf embryo brains used for quantification. Scale bar = 40 μm.

We first confirmed that the HCVp H57NPH (HCVp-NPH) mutant was expressed in zebrafish. An anti-HA western blot demonstrated good expression of the protein and no background suppression of the amber codon in the absence of the PylTNPH at 24 hpf (Figure 4C). To measure HCVp activity, we used a fluorescent membrane translocation reporter (mCherry-CAAX) that has an HCVp cleavage site located between the membrane anchor and mCherry (Figure 4D).37 Imaging and irradiation were performed at 24 hpf when the reporter showed the highest level of expression and when organs could be readily differentiated for imaging. At 24 hpf, HCVp-NPH expressing embryos were irradiated with 405 nm light and then incubated at 28.5 °C for 3 h. A region of the embryo brain was imaged at 24 hpf, and the cytoplasm-to-membrane ratio (C/M) of mCherry fluorescence was measured for each condition (Figure 4E,F). The brain was chosen for imaging due to the high density of cells that could be imaged in one confocal plane, and abundant expression of the reporter with appropriate subcellular localization was observed. The reporter-only injection showed great isolation of mCherry to the plasma membrane, while wild-type HCVp expression displayed a more homogenous distribution of mCherry throughout the cell, validating the assay for HCVp activity. Expression of the caged HCVp-NPH demonstrated similar mCherry localization to the membrane as the reporter-only control, and in the irradiated embryos, the fluorescence distribution mimicked that of the wild-type HCVp, confirming optical off-to-on switching of protease function through 405 nm irradiation.

To further assess the robustness of optical control of protease activity in zebrafish embryos, the assay was repeated and the embryo eye was imaged this time, which showed a similar subcellular redistribution for the wild-type protease expression and the irradiated HCVp-NPH embryos, while the non-irradiated animals had primarily membrane-localized fluorescence (Supporting Information, Figure S5).

Taken together, we demonstrated that chemical acylation of PylT is a viable method for incorporation of UAAs into proteins in zebrafish embryos, opening the possibility of designing, synthesizing, and using UAAs with novel structures and novel functions for which tRNA synthetases could not be engineered. Although the biological environments between the unfertilized Xenopus oocyte and the fertilized, developing, and multicellular zebrafish embryo are very different, the methodology for amber stop codon suppression with chemically acylated tRNA is very similar. This includes the chemical acylation of tRNA with the UAA of interest and the in vitro transcription of the mRNA of interest with an amber stop codon at the site of incorporation. The major differences are optimization of the amounts of acylated tRNA and mRNA injected per embryo to avoid toxicity and disruption of development, as well as the timing of optical stimulation and/or assay readout based on the design of the biological study and the need for expression of sufficient protein amounts. In the unfertilized Xenopus oocyte, between 1 and 50 ng of the mRNA may be injected, along with 10–100 ng of the acylated tRNA. Most of these experiments involve UAA incorporation into an ion channel and subsequent electrophysiological assays at 24–48 h post-injection.12 In fertilized zebrafish oocytes, up to 0.4 ng of the mRNA of interest were injected, along with up to 16 ng of acylated tRNA. We saw evidence of expression of UAA-incorporated protein as early as 5 hpf. Histidine is an important amino acid that is essential for many protein functions in several ways.38,39 It is commonly part of a catalytic triad that provides a charge relay in order to promote nucleophilic attack of a substrate, as is the case in proteases. It can also facilitate reactions by deprotonating the substrate and intermediates or participate in substrate binding through hydrogen bonding, as it does in luciferase. Histidine is frequently involved in coordination of metal ions such as in zinc finger transcription factors. Incorporating a photocaged histidine into the active site of proteins would allow for generalizable conditional control of many classes of enzymes and has long been sought after in the genetic code expansion field with minimal success. The NPOM group is an ideal photocage for histidine due to its stability under physiological conditions and its ability to be removed through brief exposure to 405 nm light. Here, we show that the caged histidine NPH, for which we have had no success in finding a compatible aminoacyl tRNA synthetase, can incorporate robustly into the active sites of several enzymes in live zebrafish embryos by injection of a chemically acylated PylT. We achieved optically controlled enzyme function through disruption of substrate hydrogen bonding, sterically occluding an active site, or blocking histidine’s function as a base. Zebrafish embryo microinjection is a standard and commonly used procedure, making it easy to introduce chemically acylated tRNAs into a vertebrate animal model.40,41 Additionally, the chemistry for chemical acylation of amino acids and even more exotic molecules like alpha-hydroxy acids42 and β-amino acids43 is well established and generalized. Ribozyme-mediated acylation of tRNA has also been established, reducing the number of required synthetic steps and streamlining the development of diverse and unique acylated tRNAs.10,44,45 Surprisingly, studies using chemically acylated tRNAs have been limited to in vitro protein expression or unfertilized Xenopus oocytes. Translating this approach to an important vertebrate animal model for human development and disease will significantly expand the utility and repertoire of UAAs that can be incorporated into proteins in vivo by bypassing the limitations of aminoacyl tRNA synthetases. We expect that this methodology can be applied to studying a wide range of biological processes.46,47

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge financial support from the National Institutes of Health (R01GM132565, R01GM106569, R01HL156398, and R24NS104617). W.B. was supported by a University of Pittsburgh Mellon Predoctoral Fellowship. We thank Dr. Joshua Wesalo for site-directed mutagenesis of the rLuc 285TAG construct. Some figures were generated using BioRender.com.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/jacs.2c11452

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.2c11452.

Experimental methods, primer and gene sequences, plasmid maps, additional luminescence and fluorescence quantification, additional micrographs, chromatograms, and mass spectra (PDF)

Contributor Information

Wes Brown, Department of Chemistry, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260, United States.

Jason D. Galpin, Department of Molecular Physiology and Biophysics, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52242, United States

Carolyn Rosenblum, Department of Chemistry, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260, United States.

Michael Tsang, Department of Developmental Biology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260, United States.

Christopher A. Ahern, Department of Molecular Physiology and Biophysics, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52242, United States

Alexander Deiters, Department of Chemistry, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Chung CZ; Amikura K; Söll D Using Genetic Code Expansion for Protein Biochemical Studies. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 598577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Courtney T; Deiters A Recent advances in the optical control of protein function through genetic code expansion. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2018, 46, 99–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Schmidt M; Summerer D Genetic code expansion as a tool to study regulatory processes of transcription. Front. Chem. 2014, 2, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Shandell MA; Tan Z; Cornish VW Genetic Code Expansion: A Brief History and Perspective. Biochemistry 2021, 60, 3455–3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Chin JW Expanding and Reprogramming the Genetic Code of Cells and Animals. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2014, 83, 379–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Brown W; Liu J; Deiters A Genetic Code Expansion in Animals. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, 13, 2375–2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Wan W; Tharp JM; Liu WR Pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase: an ordinary enzyme but an outstanding genetic code expansion tool. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1844, 1059–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Crnković A; Suzuki T; Söll D; Reynolds NM Pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase, an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase for genetic code expansion. Croat. Chem. Acta 2016, 89, 163–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Takimoto JK; Dellas N; Noel JP; Wang L Stereochemical basis for engineered pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase and the efficient in vivo incorporation of structurally divergent non-native amino acids. ACS Chem. Biol. 2011, 6, 733–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Lee J; Schwieter KE; Watkins AM; Kim DS; Yu H; Schwarz KJ; Lim J; Coronado J; Byrom M; Anslyn EV; Ellington AD; Moore JS; Jewett MC Expanding the limits of the second genetic code with ribozymes. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Noren CJ; Anthony-Cahill SJ; Griffith MC; Schultz PG A General Method for Site-specific Incorporation of Unnatural Amino Acids into Proteins. Science 1989, 244, 182–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Dougherty DA; Van Arnam EB In vivo incorporation of non-canonical amino acids by using the chemical aminoacylation strategy: a broadly applicable mechanistic tool. ChemBioChem 2014, 15, 1710–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Wu Y; Wang Z; Qiao X; Li J; Shu X; Qi H Emerging Methods for Efficient and Extensive Incorporation of Non-canonical Amino Acids Using Cell-Free Systems. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Deiters A; Lusic H A New Photocaging Group for Aromatic N-Heterocycles. Synthesis 2006, 13, 2147–2150. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Liu J; Hemphill J; Samanta S; Tsang M; Deiters A Genetic Code Expansion in Zebrafish Embryos and Its Application to Optical Control of Cell Signaling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 9100–9103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Brown W; Liu J; Tsang M; Deiters A Cell-Lineage Tracing in Zebrafish Embryos with an Expanded Genetic Code. ChemBioChem 2018, 19, 1244–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Chen Y; Ma J; Lu W; Tian M; Thauvin M; Yuan C; Volovitch M; Wang Q; Holst J; Liu M; Vriz S; Ye S; Wang L; Li D Heritable expansion of the genetic code in mouse and zebrafish. Cell Res. 2017, 27, 294–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Syed J; Palani S; Clarke ST; Asad Z; Bottrill AR; Jones AME; Sampath K; Balasubramanian MK Expanding the Zebrafish Genetic Code through Site-Specific Introduction of Azidolysine, Bicyclononyne-lysine, and Diazirine-lysine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Robertson SA; Ellman JA; Schultz PG A general and efficient route for chemical aminoacylation of transfer RNAs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 2722–2729. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Schuber F; Pinck M On the chemical reactivity of aminoacyl-tRNA ester bond. I. Influence of pH and nature of the acyl group on the rate of hydrolysis. Biochimie 1974, 56, 383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Lodemann E; Niedenthal I; Wacker A Influence of pH on the Stability of Some Aminoacyl Transfer Ribonucleic Acids and Their Elution Pattern in Chromatography on Columns of Methylated Albumin Adsorbed on Kieselguhr. Z. Naturforsch., B: Anorg. Chem., Org. Chem., Biochem., Biophys., Biol. 1970, 25, 845–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Thorne N; Inglese J; Auld DS Illuminating insights into firefly luciferase and other bioluminescent reporters used in chemical biology. Chem. Biol. 2010, 17, 646–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Ankenbruck N; Courtney T; Naro Y; Deiters A Optochemical Control of Biological Processes in Cells and Animals. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 2768–2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Gardner L; Deiters A Light-controlled synthetic gene circuits. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2012, 16, 292–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Bardhan A; Deiters A Development of photolabile protecting groups and their application to the optochemical control of cell signaling. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2019, 57, 164–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Klán P; Šolomek T; Bochet CG; Blanc A; Givens R; Rubina M; Popik V; Kostikov A; Wirz J Photoremovable Protecting Groups in Chemistry and Biology: Reaction Mechanisms and Efficacy. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 119–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Peacock JR; Walvoord RR; Chang AY; Kozlowski MC; Gamper H; Hou YM Amino acid-dependent stability of the acyl linkage in aminoacyl-tRNA. RNA 2014, 20, 758–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Woo J; Howell MH; von Arnim AG Structure-function studies on the active site of the coelenterazine-dependent luciferase from Renilla. Protein Sci. 2008, 17, 725–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Gibb B; Gupta K; Ghosh K; Sharp R; Chen J; Van Duyne GD Requirements for catalysis in the Cre recombinase active site. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 5817–5832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Brown W; Deiters A Light-activation of Cre recombinase in zebrafish embryos through genetic code expansion. Methods in Enzymology; Deiters, A., Ed; Academic Press, 2019; Chapter 13, Vol. 624, pp 265–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Radisky S; Lee M; Lu K; Koshland E Insights into the serine protease mechanism from atomic resolution structures of trypsin reaction intermediates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006, 103, 6835–6840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Carter P; Wells JA Dissecting the catalytic triad of a serine protease. Nature 1988, 332, 564–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Hedstrom L Serine Protease Mechanism and Specificity. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 4501–4524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Chatel-Chaix L; Baril M; Lamarre D Hepatitis C Virus NS3/4A Protease Inhibitors: A Light at the End of the Tunnel. Viruses 2010, 2, 1752–1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Taremi SS; Beyer B; Maher M; Yao N; Prosise W; Weber PC; Malcolm BA Construction, expression, and characterization of a novel fully activated recombinant single-chain hepatitis C virus protease. Protein Sci. 1998, 7, 2143–2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Zhou XX; Chung HK; Lam AJ; Lin MZ Optical Control of Protein Activity by Fluorescent Protein Domains. Science 2012, 338, 810–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Zhang W; Lohman AW; Zhuravlova Y; Lu X; Wiens MD; Hoi H; Yaganoglu S; Mohr MA; Kitova EN; Klassen JS; Pantazis P; Thompson RJ; Campbell RE Optogenetic control with a photocleavable protein, PhoCl. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 391–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Liao S-M; Du Q-S; Meng J-Z; Pang Z-W; Huang R-B The multiple roles of histidine in protein interactions. Chem. Cent. J. 2013, 7, 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Schneider F Histidine in Enzyme Active Centers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1978, 17, 583–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Yuan S; Sun Z Microinjection of mRNA and morpholino antisense oligonucleotides in zebrafish embryos. J. Vis. Exp. 2009, 7, 1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Rosen JN; Sweeney MF; Mably JD Microinjection of zebrafish embryos to analyze gene function. J. Vis. Exp. 2009, 9, 1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Ohta A; Murakami H; Suga H Polymerization of α-Hydroxy Acids by Ribosomes. ChemBioChem 2008, 9, 2773–2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Fujino T; Goto Y; Suga H; Murakami H Ribosomal Synthesis of Peptides with Multiple β-Amino Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 1962–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Goto Y; Katoh T; Suga H Flexizymes for genetic code reprogramming. Nat. Protoc. 2011, 6, 779–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Ohuchi M; Murakami H; Suga H The flexizyme system: a highly flexible tRNA aminoacylation tool for the translation apparatus. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2007, 11, 537–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Bradford YM; Toro S; Ramachandran S; Ruzicka L; Howe DG; Eagle A; Kalita P; Martin R; Taylor Moxon SA; Schaper K; Westerfield M Zebrafish Models of Human Disease: Gaining Insight into Human Disease at ZFIN. ILAR J. 2017, 58, 4–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Teame T; Zhang Z; Ran C; Zhang H; Yang Y; Ding Q; Xie M; Gao C; Ye Y; Duan M; Zhou Z The use of zebrafish (Danio rerio) as biomedical models. Anim. Front. 2019, 9, 68–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.