Abstract

Purpose This guideline provides recommendations for the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up care of 3rd and 4th degree perineal tears which occur during vaginal birth. The aim is to improve the management of 3rd and 4th degree perineal tears and reduce the immediate and long-term damage. The guideline is intended for midwives, obstetricians and physicians involved in caring for high-grade perineal tears.

Methods A selective search of the literature was carried out. Consensus about the recommendations and statements was achieved as part of a structured process during a consensus conference with neutral moderation.

Recommendations After every vaginal birth, a careful inspection and/or palpation by the obstetrician and/or the midwife must be carried out to exclude a 3rd or 4th degree perineal tear. Vaginal and anorectal palpation is essential to assess the extent of birth trauma. The surgical team must also include a specialist physician with the appropriate expertise (preferably an obstetrician or a gynecologist or a specialist for coloproctology) who must be on call. In exceptional cases, treatment may also be delayed for up to 12 hours postpartum to ensure that a specialist is available to treat the individual layers affected by trauma. As neither the end-to-end technique nor the overlapping technique have been found to offer better results for the management of tears of the external anal sphincter, the surgeon must use the method with which he/she is most familiar. Creation of a bowel stoma during primary management of a perineal tear is not indicated. Daily cleaning of the area under running water is recommended, particularly after bowel movements. Cleaning may be carried out either by rinsing or alternate cold and warm water douches. Therapy should also include the postoperative use of laxatives over a period of at least 2 weeks. The patient must be informed about the impact of the injury on subsequent births as well as the possibility of anal incontinence.

Key words: guideline, perineal tear, management perineal tear, OASI

I Guideline Information

Guidelines program of the DGGG, OEGGG and SGGG

For information on the guidelines program, please refer to the end of the guideline.

Citation format

Management of Third and Fourth-Degree Perineal Tears After Vaginal Birth. Guideline of the DGGG, OEGGG and SGGG (S2k-Level, AWMF Registry No. 015/079, December 2020). Geburtsh Frauenheilk 2022. doi:10.1055/a-1933-2647

Guideline documents

The complete long version in German, a slide version of this guideline as well as a list of the conflicts of interest of all of the authors is available on the homepage of the AWMF: https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/015-079.html

Guideline authors

Table 1 Lead author and/or coordinating guideline author.

| Author | AWMF professional society |

|---|---|

| Prof. Dr. Werner Bader | German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics (Deutsche Gesellschaft für

Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe [DGGG]) Working Group for Urogynecology and Pelvic Floor Plastic Reconstruction (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Urogynäkologie und plastische Beckenbodenrekonstruktion [AGUB]) |

| Dr. Stephan Kropshofer | Austrian Urogynecology Working Group for Reconstructive Pelvic Floor Surgery (Österreichische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Urogynäkologie und Rekonstruktive Beckenbodenchirurgie [AUB]) |

Table 2 Participating guideline authors.

| Author Mandate holder |

DGGG working group (AG)/ AWMF/non-AWMF professional society/ organization/association |

|---|---|

| Priv. Doz. Dr. Thomas Aigmüller | Austrian Urogynecology Working Group for Reconstructive Pelvic Floor Surgery (Österreichische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Urogynäkologie und Rekonstruktive Beckenbodenchirurgie [AUB]) |

| Dr. Kathrin Beilecke | German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics (Deutsche Gesellschaft für

Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe [DGGG]) Working Group for Urogynecology and Pelvic Floor Plastic Reconstruction (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Urogynäkologie und plastische Beckenbodenrekonstruktion [AGUB]) |

| Prof. Dr. Andrea Frudinger | Österreichische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Urogynäkologie und Rekonstruktive Beckenbodenchirurgie (AUB) |

| Dr. Ksenia Krögler-Halpern | Österreichische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Urogynäkologie und Rekonstruktive Beckenbodenchirurgie (AUB) |

| Prof. Dr. Engelbert Hanzal | Österreichische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Urogynäkologie und Rekonstruktive Beckenbodenchirurgie (AUB) |

| Prof. Dr. Hanns Helmer | Österreichische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Urogynäkologie und Rekonstruktive Beckenbodenchirurgie (AUB) |

| Dr. Susanne Hölbfer | Österreichische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Urogynäkologie und Rekonstruktive Beckenbodenchirurgie (AUB) |

| Dr. Hansjörg Huemer | Österreichische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Urogynäkologie und Rekonstruktive Beckenbodenchirurgie (AUB) |

| Moenie van der Kleyn, MPH | Austrian Midwives Association (Österreichisches Hebammengremium) |

| Dr. Irmgard E. Kronberger | Austrian Working Group for Coloproctology (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Coloproktologie Österreich [ACP]) |

| Prof. Dr. Annette Kuhn | Swiss Working Group for Urogynecology and Pelvic Floor Pathology (Schweizerische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Urogynäkologie und Beckenbodenpathologie [AUG]) |

| Prof. Dr. Johann Pfeifer | Austrian Surgical Society (Österreichische Gesellschaft für Chirurgie [ÖGC]) |

| Prof. Dr. Christl Reisenauer | Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe (DGGG) Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Urogynäkologie und plastische Beckenbodenrekonstruktion (AGUB) |

| Prof. Dr. Karl Tamussino | Österreichische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Urogynäkologie und Rekonstruktive Beckenbodenchirurgie (AUB) |

| Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Umek | Österreichische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Urogynäkologie und Rekonstruktive Beckenbodenchirurgie (AUB) |

| Dr. Dieter Kölle | Österreichische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Urogynäkologie und Rekonstruktive Beckenbodenchirurgie (AUB) |

| Prof. Dr. Michael Abou-Dakn | Working Group for Obstetrics and Prenatal Medicine (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Geburtshilfe und Pränatalmedizin e. V. [AGG]) |

| Prof. Dr. Boris Gabriel | Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Urogynäkologie und plastische Beckenbodenrekonstruktion e. V. (AGUB) |

| Prof. Dr. Oliver Schwandner | Surgical Working Group for Coloproctology in Germany (Chirurgische Arbeitsgemeinschaft Coloproktologie Deutschland [CACP]) |

| Prof. Dr. Annette Kuhn | Schweizerische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Urogynäkologie und Beckenbodenpathologie (AUG) |

| Dr. Irmgard E. Kronberger | Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Coloproktologie Österreich (ACP) |

| Priv. Doz. Dr. Gunda Pristauz-Telsnigg | Austrian Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics (Österreichische Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe [OEGGG]) |

| Petra Welskop | Österreichisches Hebammengremium |

The following professional societies/working groups/organizations/associations stated that they wished to contribute to the text of the guideline and participate in the consensus conference and nominated representatives to contribute and attend ( Table 2 ).

The guideline was moderated by Dr. Monika Nothacker (AWMF-certified guideline consultant/moderator).

II Guideline Application

Purpose and objectives

The guideline provides recommendations for the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up care of 3rd and 4th degree perineal tears that occur during vaginal birth. The aim is to improve the management of 3rd and 4th degree tears and reduce the immediate and long-term damage. The guideline is intended for midwives, obstetricians and physicians involved in the care of high-grade perineal tears.

Targeted areas of patient care

Inpatient care

Outpatient care

Target user groups/target audience

This guideline is devised for the following groups of professionals:

gynecologists in private practice

gynecologists based in hospitals

midwives

coloproctologists

Adoption and period of validity

The validity of this guideline was confirmed by the executive boards/representatives of the participating professional societies/working groups/organizations/associations as well as by the board of the DGGG, the DGGG Guidelines Commission and the OEGGG and SGGG in December 2019 and was thereby approved in its entirety. This guideline is valid from 1 February 2020 through to 31 January 2023. Because of the contents of this guideline, this period of validity is only an estimate.

The guideline can be reviewed and updated at an earlier point in time if urgently required. If the guideline still reflects the current state of knowledge, the period of validity can be extended for a maximum period of five years.

III Methodology

Basic principles

The method used to prepare this guideline was determined by the class to which this guideline was assigned. The AWMF Guidance Manual (Version 1.0) has set out the respective rules and requirements for different classes of guidelines. Guidelines are differentiated into lowest (S1), intermediate (S2), and highest (S3) class. The lowest class is defined as consisting of a set of recommendations for action compiled by a non-representative group of experts. In 2004, the S2 class was divided into two subclasses: a systematic evidence-based subclass (S2e) and a structural consensus-based subclass (S2k). The highest S3 class combines both approaches.

This guideline was classified as: S2k

Grading of recommendations

The grading of evidence based on the systematic search, selection, evaluation and synthesis of an evidence base which is then used to grade the recommendations is not envisaged for S2k guidelines. The different individual statements and recommendations are only differentiated by syntax, not by symbols ( Table 3 ):

Table 3 Grading of recommendations (based on Lomotan et al., Qual Saf Health Care 2010).

| Description of binding character | Expression |

|---|---|

| Strong recommendation with highly binding character | must/must not |

| Regular recommendation with moderately binding character | should/should not |

| Open recommendation with limited binding character | may/may not |

Statements

Expositions or explanations of specific facts, circumstances or problems without any direct recommendations for action included in this guideline are referred to as “statements”. It is not possible to provide any information about the level of evidence for these statements.

Achieving consensus and level of consensus

At structured NIH-type consensus-based conferences (S2k/S3 level), authorized participants attending the session vote on draft statements and recommendations. The process is as follows. A recommendation is presented, its contents are discussed, proposed changes are put forward, and all proposed changes are voted on. If a consensus (> 75% of votes) is not achieved, there is another round of discussions, followed by a repeat vote. Finally, the extent of consensus is determined, based on the number of participants ( Table 4 ).

Table 4 Level of consensus based on extent of agreement.

| Symbol | Level of consensus | Extent of agreement |

|---|---|---|

| +++ | Strong consensus | > 95% of participants agree |

| ++ | Consensus | > 75 – 95% of participants agree |

| + | Majority agreement | > 50 – 75% of participants agree |

| – | No consensus | < 51% of participants agree |

Expert consensus

As the term already indicates, this refers to consensus decisions taken specifically with regard to recommendations/statements issued without a prior systematic search of the literature (S2k) or where evidence is lacking (S2e/S3). The term “expert consensus” (EC) used here is synonymous with terms used in other guidelines such as “good clinical practice” (GCP) or “clinical consensus point” (CCP). The strength of the recommendation is graded as previously described in the chapter Grading of recommendations but without the use of symbols; it is only expressed semantically (“must”/“must not” or “should”/“should not” or “may”/“may not”).

IV Guideline

1 Epidemiology

| Consensus-based recommendation 1.E1 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| If an episiotomy is indicated, the incision should be made in a mediolateral direction to prevent the incision from injuring the anal sphincter. | |

According to the Austrian Registry of Births, in 2017 a 3rd degree perineal tear during vaginal birth occurred in 1.9% of cases and a 4th degree perineal tear in 0.1%. 3.1% of primiparous women suffered a 3rd degree perineal tear and 0.2% had a 4th degree perineal tear. The respective figures for multiparous woman were 0.9% (grade 3 PT) and 0.1% (grade 4 PT) 1 .

In Germany, the respective incidences for the year 2017 were 1.74% (grade 3 PT) and 0.12% (grade 4 PT). There were no data on the respective incidence in primiparous and multiparous women 2 .

In contrast to these figures, a systematic review reported an incidence of 11% for tears of the external or internal anal sphincter 3 .

In recent years, the reported incidence of high-grade perineal tears has increased. This increase has primarily been attributed to improvements in the detection rate 4 , 5 , 6 .

Symptoms subsequent to perineal tears include flatulence incontinence, pathological urge to defecate and, more rarely, fecal incontinence with the consistency ranging from watery to firm stools. The frequency of these symptoms tends to increase over the years following the birth 7 , 8 , 9 .

According to the literature 5 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , the list of risk factors in descending order of importance (the respective odds ratios (OR) are given in brackets) are:

use of forceps during the birth (OR 2.9 – 4.9)

a birth weight of > 4 kg or an occipital frontal circumference of > 35 cm (OR 1.4 – 5.2; it increases with the birth weight of the infant)

a median episiotomy (OR 2.4 – 2.9)

nulliparity (OR 2.4)

vacuum extraction delivery (OR 1.7 – 2.9)

status post female genital mutilation (OR 1.6 – 2.7)

occiput posterior position of the fetus (OR 1.7 – 3.4)

shoulder dystocia (OR 2)

prolonged second stage of labor (OR 1.2 – 3.9)

Kristeller maneuver/fundal pressure (OR 1.8)

delivery in the lithotomy position or squatting position (OR 1.2 – 2.2)

Risk-reducing factors are 5 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 :

selective episiotomy (OR 0,7)

mediolateral episiotomy during operative vaginal birth (OR 0,2 – 0.5)

damp perineal compresses (OR 0.5)

perineal massage performed antenatally or during the birth (OR 0.5)

The following obstetric measures are not prophylactic, but they also do not increase the risk of high-grade perineal lacerations 5 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 :

timing and type of pushing

water birth

Ritgenʼs maneuver

vaginal balloon dilatation during pregnancy

“hands-on” vs. “hands-off” approach: “hands-off” means that no episiotomy will be carried out but this has no effect on perineal tears.

The following obstetric measures could not yet be definitively assessed:

Induction of labor with initiation of uterine contractions

Maternal obesity

Epidural anesthesia

The role of episiotomy with regard to parity and the angle of incision also requires further investigation.

2 Classification

Perineal lacerations are classified as higher grade when the trauma includes injury to the external anal sphincter 35 :

Grade 3 perineal tear: injury to the anal sphincter complex, rectal wall is intact

Grade 4 perineal tear: injury to the anal sphincter complex, injury to the anorectal mucosa

The following subdivision of grade 3 perineal tears is useful 36 :

3a: less than 50% thickness of the external anal sphincter is torn

3b: more than 50% thickness of the external anal sphincter is torn

3c: external and internal anal sphincter are torn

As the internal anal sphincter plays an important role in maintaining the mechanism of continence, every attempt must be made to identify any trauma to the internal anal sphincter in cases of extended perineal trauma 37 , 38 .

Tearing of the anal epithelium while the internal anal sphincter remains intact (buttonhole tear) is a special type of high-grade perineal laceration. It is rare but if it remains untreated, there is a real risk of developing a rectovaginal fistula. It can be diagnosed postpartum using anal palpation 39 , 40 , 41 . If the anorectal mucosa has torn while the external anal sphincter remains intact, there is a higher probability of injury to the internal anal sphincter. The conclusive identification of this type of injury is only possible with surgery or using transanal endosonography 42 , 43 .

3 Diagnosis

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.E2 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| In cases where the extent of injury is not clear, an experienced physician with specialist expertise (preferably a specialist for gynecology and obstetrics or a consultant with coloproctological expertise) must be called in. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.E3 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| If there is any doubt, the diagnosis should be high-grade perineal tear. | |

After every vaginal birth, a 3rd and 4th degree perineal tear must be excluded by careful initial inspection and/or palpation by the obstetrician and/or the midwife. The use of vaginal and anorectal palpation to assess birth trauma is extremely important. Both vaginal and rectal palpation are expressly recommended to assess the extent of injury for any perineal tear which is grade 2 or above.

If it is not possible to exclude a grade 3 perineal tear, an experienced physician with specialist expertise (preferably a specialist for gynecology and obstetrics or a consultant with coloproctological expertise) must be called in to confirm the suspected diagnosis, provide a general classification of the injury (grade 3 or grade 4 perineal tear) as guidance and initiate further action.

4 Postpartum management

| Consensus-based recommendation 4.E4 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Treatment of a grade 3 or 4 perineal tear must be carried out under sufficient regional or general anesthesia to achieve maximum relaxation of the sphincter muscles while ensuring ensure optimal visualization of the area requiring surgery. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 4.E5 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Grade 3 and 4 perineal tears must be treated in a suitable operating room with

sufficient lighting. Appropriate instruments with non-traumatic clamps must be

available. The operating surgeon must have an assistant. Completely aseptic conditions may be beneficial in selected cases. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 4.E6 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| When treating a 3rd or 4th degree perineal tear, the surgical team must include a specialist with sufficient expertise (preferably a specialist for gynecology and obstetrics or a consultant with coloproctological expertise). In exceptional cases, surgery may be delayed for up to 12 hours postpartum to ensure that treatment will be carried out by a specialist. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 4.E7 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| When treating grade 3 or 4 perineal tears, patients should receive a single perioperative dose of an antibiotic. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 4.E8 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Atraumatic, slowly absorbable sutures should be used to suture grade 3 or 4 perineal tears. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 4.E9 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Placement of a bowel stoma must not be carried out during primary surgery of a high-grade perineal tear. | |

4.1 Preparation

Management of a 3rd or 4th degree perineal care requires general or regional anesthesia to achieve maximum sphincter relaxation and sufficient pain relief. The procedure is carried out under aseptic conditions in an operating room or an equivalent facility with assistants, appropriate instruments and equipment. The patient is placed in the lithotomy position. The surgical team must include a specialist with sufficient experience 44 . However, the number of previous operations does not appear to be relevant with regard to avoiding anal incontinence 45 .

In exceptional cases, surgery may be delayed for up to 12 hours postpartum 46 . Adequate documented preoperative informed consent is required unless it is an emergency.

Patients should receive a single perioperative dose of an antibiotic 47 .

4.2 Surgical strategy

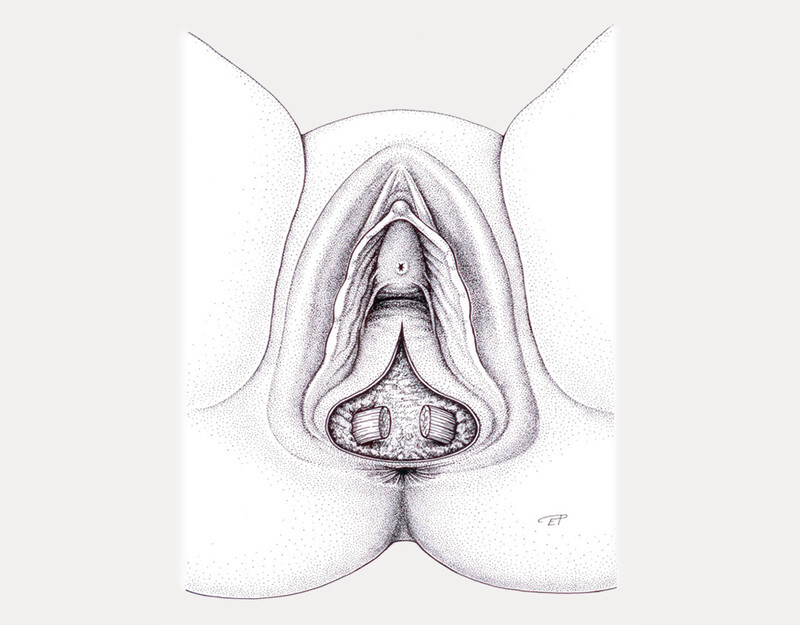

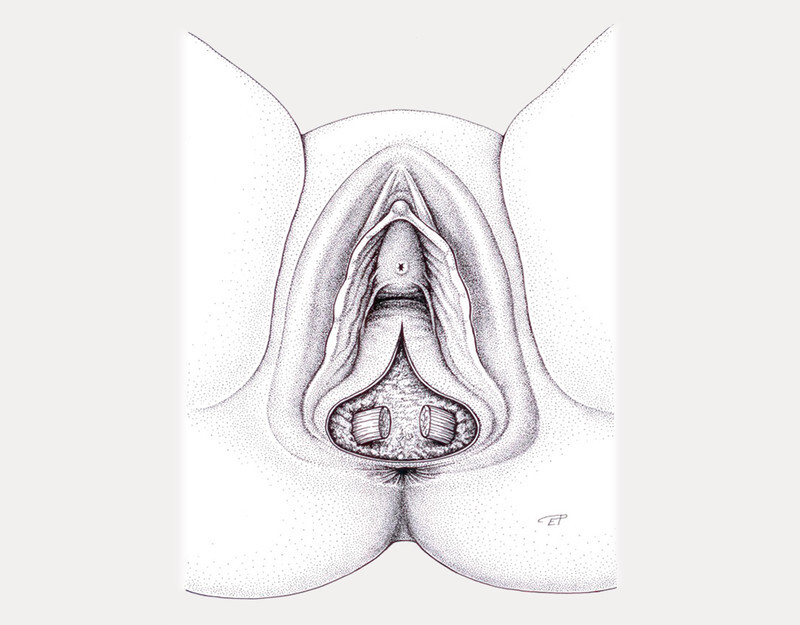

Identification of additional birth trauma and precise classification of the perineal tear based on a speculum examination and a rectal examination ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Initial situation (with the kind permission of Dr. Eva Polsterer). [rerif]

If necessary, cervical and high vaginal tears must be treated first, working from the inside to the outside, before treating the perineal tear.

For 4th degree tears: repair the anorectal epithelium using atraumatic end-to-end 3-0 sutures 48 , 49 .

If the ends of the internal anal sphincter can be identified, the edges should be approximated using atraumatic interrupted mattress sutures, preferably 3-0 sutures 49 , 50 .

The ends of the external anal sphincter must be identified and gripped with Allis clamps.

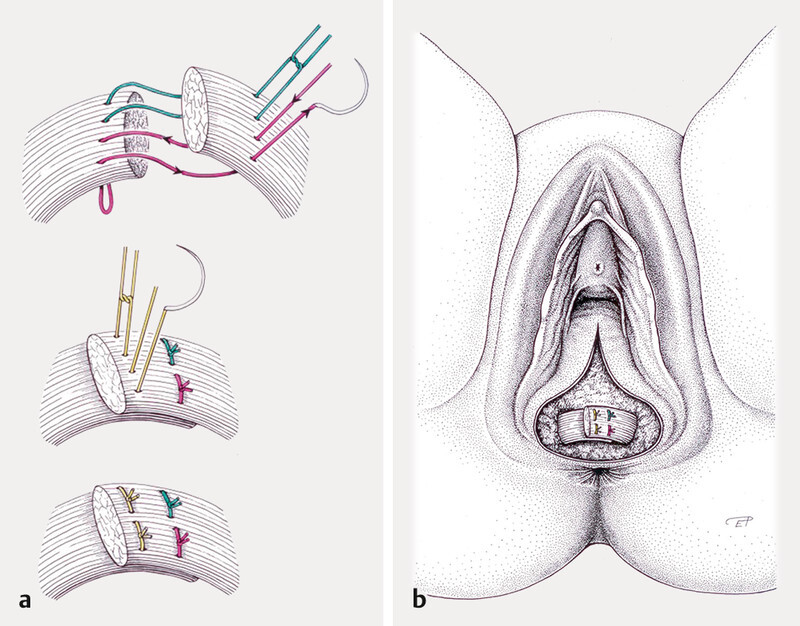

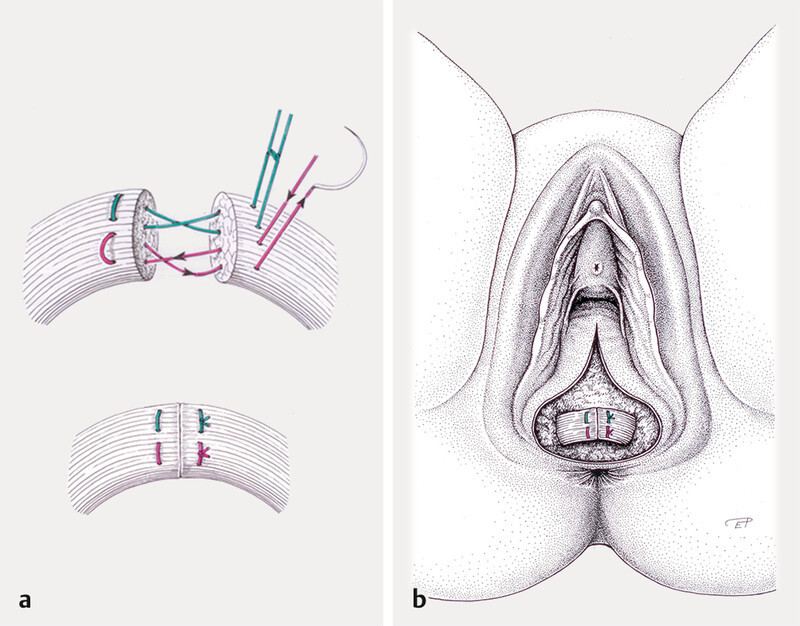

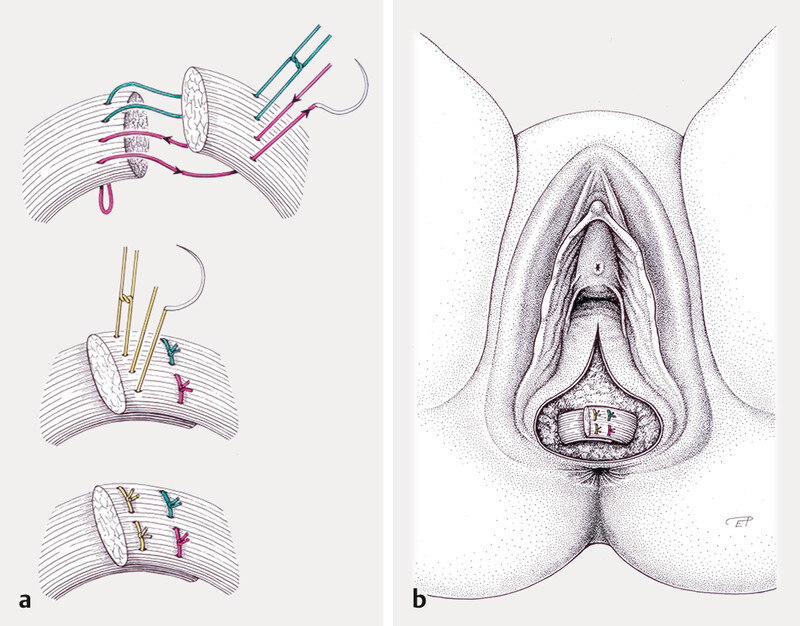

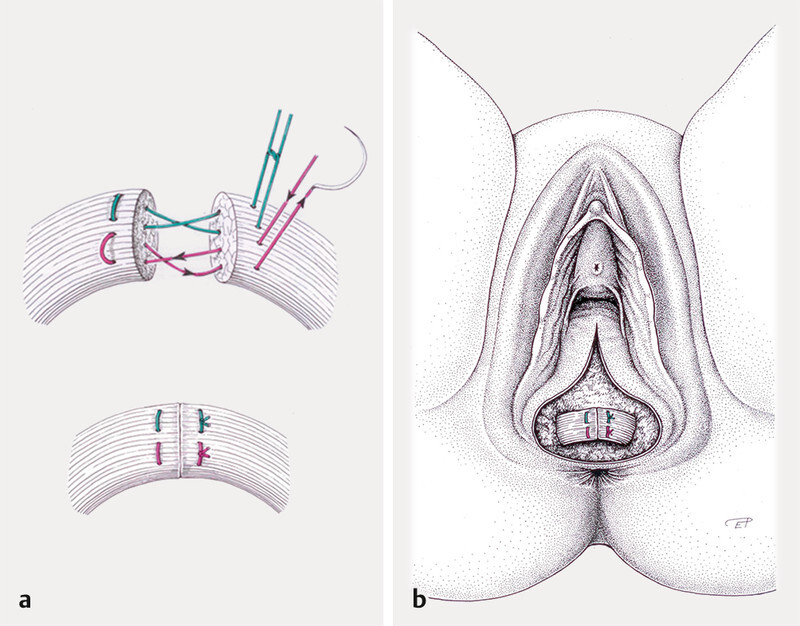

The external anal sphincter must be sutured with atraumatic U-sutures, preferably 2-0 sutures. There is a choice between 2 methods for the repair: an overlapping technique and an end-to-end technique ( Figs. 2 und 3 ) 51 , 52 , 53 . The end-to-end technique should be used if the muscle has not torn completely 45 , 54 . The overlapping technique reduces symptoms of fecal urgency and fecal incontinence after 1 year, but after 3 years no differences were found between the two techniques 55 . There is some evidence that using the end-to-end technique reduces the flatulence rate 54 . It is not possible to give a definitive recommendation about the best surgical method. The surgeon should use the method he/she is most familiar with.

Fig. 2.

Overlapping technique (with the kind permission of Dr. Eva Polsterer). [rerif]

Fig. 3.

End-to-end technique (with the kind permission of Dr. Eva Polsterer). [rerif]

The perineum must be repaired layer by layer.

Birth injuries must be recorded and an operative report must be written.

Atraumatic slowly absorbable sutures should be used for items 2 – 6. The choice between braided or monofilament sutures is up to the surgeonʼs individual preference 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 . Placement of a bowel stoma is not indicated 56 , 57 .

| Consensus-based recommendation 4.E10 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| For 4th degree perineal tears, the anorectal epithelium should be repaired using an end-to-end technique and atraumatic sutures should be used, preferably 3-0 sutures. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 4.E11 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| If the ends of the internal anal sphincter can be identified, the edges must be approximated and sutured using atraumatic interrupted mattress sutures, preferably 3-0 sutures. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 4.E12 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| The end-to-end technique should be used if the external anal sphincter has not torn completely. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 4.E13 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Neither the end-to-end technique nor the overlapping technique has been found to result in better outcomes following the repair of tears of the external anal sphincter. The surgeon must therefore use the method with which he/she is most familiar. | |

5 The postpartum period

| Consensus-based recommendation 5.E14 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| There is no evidence supporting the prophylactic postoperative administration of antibiotics. Postoperative doses of antibiotics may be recommended in selected cases after an individual risk assessment which also takes local contamination and any potentially serious consequences into account. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 5.E15 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Laxatives should be administered for a period of at least 2 weeks postoperatively. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 5.E16 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Daily cleaning with running water is recommended, particularly after a bowel movement. Washing can be carried out by rinsing the area or using alternate cold and hot water douches. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 5.E17 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Sitz baths (with or without additives) and ointments should not be used. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 5.E18 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Cool pads or cool topical analgesic medication should be used as it may reduce the swelling and thereby have a positive impact on pain. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 5.E19 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| It is important to ensure that pain therapy is adequate as local pain could lead to urinary and even fecal retention. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 5.E20 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| No rectal examination should be carried out in cases where the postpartum healing process is uncomplicated. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 5.E21 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Patients must be informed about the extent of their birth trauma and potential

late sequelae. The information must also include information about follow-up

care, the actions they should take, and the help that is available. Patients must be informed about the possibility of a longer latency period until the appearance of symptoms of anal incontinence. | |

5.1 Antibiotics

There is only indirect evidence about the benefit of extended postoperative prophylactic administration of antibiotics 58 . Extended antibiotic prophylaxis (e.g., cephalosporin + metronidazole for 5 days) may be administered after weighing up the risks in each individual case 36 .

5.2 Laxatives

The postoperative use of laxatives is recommended (for pain reduction and to obtain a better functional outcome) 58 , 59 . The authors of the guideline recommend the administration of laxatives for a period of at least 2 weeks postoperatively. No laxative therapy should be prescribed if the patient is suffering from diarrhea.

5.2 Pain therapy and local therapy

Daily cleaning using running water of drinking water quality is recommended, particularly after a bowel movement (e.g., alternating cold and warm douches). There is no evidence supporting the utility of sitz baths with or without additives or the use of wound ointments with special additives.

Cool compresses or cool topical analgesic medication may reduce the swelling and thereby have a positive impact on pain 60 .

It is important to ensure that pain therapy is adequate as local pain could lead to urinary or even fecal retention 61 .

No rectal examination should be carried out in cases where the postpartum healing process is uncomplicated 50 .

The rate of wound complications after 3rd or 4th degree perineal tears (wound infection, dehiscence, repeat surgery, re-admission to hospital) is between 7.3% 62 and 24.6% 63 ; smoking and a higher BMI are known to be independent risk factors while antibiotic therapy intrapartum reduces the risk of wound healing disorders 62 , 63 .

Patients must be informed about the extent of their birth injury as well as potential late sequelae. Patients must be provided with sufficient information about follow-up care, the actions they should take and the help that is available.

6 Follow-up care

| Consensus-based recommendation 6.E22 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| A gynecological or coloproctological follow-up examination should be carried out after about 3 months and must include a review of the patientʼs medical history, symptoms of anal incontinence, an inspection of the area, and vaginal and rectal palpation. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 6.E23 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Patients should be referred to physiotherapy to strengthen their pelvic floor musculature. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 6.E24 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| If symptoms of anal incontinence persist despite carrying out all conservative treatment options, the patient must be referred to a center with the appropriate expertise (anal endosonography, conservative and surgical treatment options). | |

A gynecological follow-up examination should be carried out around 3 months postpartum. The follow-up examination must at least include the following:

-

Review of the patientʼs medical history including questions about the following symptoms of anal incontinence. The incidences of the various symptoms reported at early follow-up examinations after 3rd or 4th degree perineal tears are given in brackets 52 , 57 , 64 – 67

flatulence incontinence (up to 50%)

fecal urgency (26%)

liquid stool incontinence (8%)

solid stool incontinence (4%)

Inspection of the affected area

Vaginal and rectal palpation

Referral of the patient to physiotherapy to strengthen her pelvic floor musculature. Early biofeedback-supported physiotherapy offers no advantages compared to classic pelvic floor training 68 . In cases with anal incontinence, triple-target therapy (a combination of amplitude modulated medium frequency stimulation and electromyography biofeedback) has been found to offer superior results compared to standard stimulation therapy with electromyography biofeedback 69 .

The patient must be informed about the potential long latency period until the occurrence/worsening of symptoms of anal incontinence 7 , 70 .

Counselling with regard to subsequent deliveries

If the patient continues to have symptoms of anal incontinence, she should be referred to a center with the appropriate expertise (anal endosonography, conservative and surgical treatment options).

7 Recommendations for subsequent births

| Consensus-based recommendation 7.E25 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Women who have a 3rd or 4th degree perineal tear should be offered an elective caesarean section, especially women with persistent symptoms of anal incontinence, reduced sphincter function or suspected fetal macrosomia. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 7.E26 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Women wishing to have a spontaneous vaginal birth must be carefully evaluated with regard to their history of potential sequelae of a previous 3rd or 4th degree perineal injury and be informed in detail about the potential risks. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 7.E27 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| The indications for an episiotomy in a woman wishing to have a subsequent pregnancy with a vaginal birth after a previous 3rd or 4th degree perineal tear must very restrictive. | |

The existing data does not permit any clear recommendations as to the birth mode in future pregnancies. The patient must be informed that, depending on the data source, the risk of a repeat injury to the anal sphincter in a subsequent vaginal birth ranges from non-existent 45 , 54 , 55 to a sevenfold higher risk 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 ; however, more than 95% of women do not suffer a repeat high-grade perineal tear 73 , 76 .

The risk of perineal laceration increases with increasing birth weight of the baby 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 . It has also been shown that in vaginal births after a previous 3rd or 4th degree perineal tear, the short-term risk of persistent fecal incontinence is higher 77 , 78 . The difference was no longer found in long-term studies which covered a period of 5 or more years 79 , 80 .

Elective caesarean section should be offered to all women who have previously had a grade 3 or grade 4 perineal tear, particularly patients with persistent symptoms of fecal incontinence, reduced sphincter function or suspected fetal macrosomia.

An episiotomy must be carried out restrictively if a woman wishes to have a vaginal delivery in a subsequent pregnancy after a prior 3rd or 4th degree perineal tear 76 .

The following approach must be used if the patient wishes to have a vaginal delivery:

Good communication with the patient

Perineal “hands-on” support to ensure optimal control of the birth and gradual delivery of the babyʼs head

Slow delivery of the babyʼs head

The patient may freely choose the position in which she gives birth; however, once the baby is crowning, the perineal area must be clearly visible

A mediolateral episiotomy should be performed if required in individual cases 81

Acknowledgements

In memoriam Dr. Irmgard „Soni“ Kronberger.

Acknowledgements

In memoriam Dr. Irmgard “Soni” Kronberger.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt The conflicts of interest of all of the authors are listed in the long version of the guideline./Die Interessenkonflikte der Autoren sind in der Langfassung der Leitlinie aufgelistet.

References/Literatur

- 1.Delmarko I, Leitner H, Harrasser L. Bericht Geburtenregister Österreich – Geburtenjahr 2017. 2017. https://www.iet.at/page.cfm?vpath=register/geburtenregister https://www.iet.at/page.cfm?vpath=register/geburtenregister

- 2.Institut für Qualitätssicherung und Transparenz im Gesundheitswesen . Bundesauswertung 2017 (Geburtshilfe). Germany 2017. 2017. https://www.dghwi.de/iqtig-basisauswertung-geburtshilfe-2019/ https://www.dghwi.de/iqtig-basisauswertung-geburtshilfe-2019/

- 3.Dudding T C, Vaizey C J, Kamm M A. Obstetric anal sphincter injury: incidence, risk factors, and management. Ann Surg. 2008;247:224–237. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318142cdf4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gurol-Urganci I, Cromwell D A, Edozien L C. Third- and fourth-degree perineal tears among primiparous women in England between 2000 and 2012: time trends and risk factors. BJOG. 2013;120:1516–1525. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ekeus C, Nilsson E, Gottvall K. Increasing incidence of anal sphincter tears among primiparas in Sweden: a population-based register study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87:564–573. doi: 10.1080/00016340802030629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kettle C, Tohill S. Perineal care. BMJ Clin Evid. 2011;2011:1401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frudinger A, Ballon M, Taylor S A. The natural history of clinically unrecognized anal sphincter tears over 10 years after first vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1058–1064. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816c4433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nordenstam J, Altman D, Brismar S. Natural progression of anal incontinence after childbirth. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:1029–1035. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-0901-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollack J, Nordenstam J, Brismar S. Anal incontinence after vaginal delivery: a five-year prospective cohort study. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:1397–1402. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000147597.45349.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aasheim V, Nilsen A BV, Reinar L M. Perineal techniques during the second stage of labour for reducing perineal trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(06):CD006672. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006672.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ampt A J, Ford J B, Roberts C L. Trends in obstetric anal sphincter injuries and associated risk factors for vaginal singleton term births in New South Wales 2001–2009. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;53:9–16. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baghestan E, Irgens L M, Bordahl P E. Trends in risk factors for obstetric anal sphincter injuries in Norway. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:25–34. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e2f50b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berggren V, Gottvall K, Isman E. Infibulated women have an increased risk of anal sphincter tears at delivery: a population-based Swedish register study of 250 000 births. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92:101–108. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blomberg M. Maternal body mass index and risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:395803. doi: 10.1155/2014/395803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brito L G, Ferreira C H, Duarte G. Antepartum use of Epi-No birth trainer for preventing perineal trauma: systematic review. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:1429–1436. doi: 10.1007/s00192-015-2687-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bulchandani S, Watts E, Sucharitha A. Manual perineal support at the time of childbirth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2015;122:1157–1165. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carroli G, Mignini L. Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(01):CD000081. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000081.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corrêa Junior M D, Passini Júnior R. Selective Episiotomy: Indications, Techinique, and Association with Severe Perineal Lacerations. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2016;38:301–307. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1584942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Vogel J, van der Leeuw-van Beek A, Gietelink D. The effect of a mediolateral episiotomy during operative vaginal delivery on the risk of developing obstetrical anal sphincter injuries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:4040–4.04E7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elvander C, Ahlberg M, Thies-Lagergren L. Birth position and obstetric anal sphincter injury: a population-based study of 113 000 spontaneous births. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:252. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0689-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garretto D, Lin B B, Syn H L. Obesity May Be Protective against Severe Perineal Lacerations. J Obes. 2016;2016:9.376592E6. doi: 10.1155/2016/9376592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groutz A, Hasson J, Wengier A. Third- and fourth-degree perineal tears: prevalence and risk factors in the third millennium. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:3470–3.47E6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hauck Y L, Lewis L, Nathan E A. Risk factors for severe perineal trauma during vaginal childbirth: a Western Australian retrospective cohort study. Women Birth. 2015;28:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hollowell J, Pillas D, Rowe R. The impact of maternal obesity on intrapartum outcomes in otherwise low risk women: secondary analysis of the Birthplace national prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2014;121:343–355. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jango H, Langhoff-Roos J, Rosthoj S. Modifiable risk factors of obstetric anal sphincter injury in primiparous women: a population-based cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:590–5.9E7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang H, Qian X, Carroli G. Selective versus routine use of episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(02):CD000081. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000081.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamisan Atan I, Shek K L, Langer S. Does the Epi-No((R)) birth trainer prevent vaginal birth-related pelvic floor trauma? A multicentre prospective randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2016;123:995–1003. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landy H J, Laughon S K, Bailit J L. Characteristics associated with severe perineal and cervical lacerations during vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:627–635. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820afaf2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laughon S K, Berghella V, Reddy U M. Neonatal and maternal outcomes with prolonged second stage of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:57–67. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindholm E S, Altman D. Risk of obstetric anal sphincter lacerations among obese women. BJOG. 2013;120:1110–1115. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lund N S, Persson L K, Jango H. Episiotomy in vacuum-assisted delivery affects the risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;207:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raisanen S, Selander T, Cartwright R. The association of episiotomy with obstetric anal sphincter injury–a population based matched cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simic M, Cnattingius S, Petersson G. Duration of second stage of labor and instrumental delivery as risk factors for severe perineal lacerations: population-based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:72. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1251-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith L A, Price N, Simonite V. Incidence of and risk factors for perineal trauma: a prospective observational study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cunningham F, Leveno K, Bloom S, Hauth J, Rouse D, Spong C.Williams Obstetrics 23rd ed.ed.New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists . Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Guideline No. 29, Clinical Green Top Guidelines: Management of third- and fourth-degree perineal tears following vaginal delivery. March 2007. http://www.rcog.org.uk/guidelines http://www.rcog.org.uk/guidelines

- 37.Lindqvist P G, Jernetz M. A modified surgical approach to women with obstetric anal sphincter tears by separate suturing of external and internal anal sphincter. A modified approach to obstetric anal sphincter injury. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10:51. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahony R, Behan M, Daly L. Internal anal sphincter defect influences continence outcome following obstetric anal sphincter injury. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:2170–2.17E7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chew S S, Rieger N A. Transperineal repair of obstetric-related anovaginal fistula. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;44:68–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2004.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rahman M S, Al-Suleiman S A, El-Yahia A R. Surgical treatment of rectovaginal fistula of obstetric origin: a review of 15 yearsʼ experience in a teaching hospital. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;23:607–610. doi: 10.1080/01443610310001604349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rieger N, Perera S, Stephens J. Anal sphincter function and integrity after primary repair of third-degree tear: uncontrolled prospective analysis. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74:122–124. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-1433.2003.02920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sentovich S M, Blatchford G J, Rivela L J. Diagnosing anal sphincter injury with transanal ultrasound and manometry. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1430–1434. doi: 10.1007/BF02070707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burnett S J, Spence-Jones C, Speakman C T. Unsuspected sphincter damage following childbirth revealed by anal endosonography. Br J Radiol. 1991;64:225–227. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-64-759-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sultan A H. London: Springer; 2003. Primary and secondary anal Sphincter Repair; pp. 149–157. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scheer I, Thakar R, Sultan A H. Mode of delivery after previous obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS)–a reappraisal? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:1095–1101. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-0908-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nordenstam J, Mellgren A, Altman D. Immediate or delayed repair of obstetric anal sphincter tears-a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2008;115:857–865. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duggal N, Mercado C, Daniels K. Antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of postpartum perineal wound complications: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1268–1273. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816de8ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Briel J W, de Boer L M, Hop W C. Clinical outcome of anterior overlapping external anal sphincter repair with internal anal sphincter imbrication. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:209–214. doi: 10.1007/BF02238250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thakar R, Sultan A H. Management of obstetric anal sphincter injury. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;5:72–78. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sultan A H, Monga A K, Kumar D. Primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter rupture using the overlap technique. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106:318–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Farrell S A, Gilmour D, Turnbull G K. Overlapping compared with end-to-end repair of third- and fourth-degree obstetric anal sphincter tears: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:16–24. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e366ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fernando R, Sultan A H, Kettle C. Methods of repair for obstetric anal sphincter injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(03):CD002866. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002866.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fernando R J, Sultan A H, Kettle C. Repair techniques for obstetric anal sphincter injuries: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1261–1268. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000218693.24144.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Priddis H, Dahlen H G, Schmied V. Risk of recurrence, subsequent mode of birth and morbidity for women who experienced severe perineal trauma in a first birth in New South Wales between 2000–2008: a population based data linkage study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:89. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Edwards H, Grotegut C, Harmanli O H. Is severe perineal damage increased in women with prior anal sphincter injury? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;19:723–727. doi: 10.1080/14767050600921307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clark C L, Wilkinson K H, Rihani H R. Peri-operative management of patients having external anal sphincter repairs: temporary prevention of defaecation does not improve outcomes. Colorectal Dis. 2001;3:238–244. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2001.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hasegawa H, Yoshioka K, Keighley M R.Randomized trial of fecal diversion for sphincter repair Dis Colon Rectum 200043961–964.discussion 964–965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kirss J, Pinta T, Bockelman C. Factors predicting a failed primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter injury. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95:1063–1069. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mahony R, Behan M, OʼHerlihy C. Randomized, clinical trial of bowel confinement vs. laxative use after primary repair of a third-degree obstetric anal sphincter tear. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:12–17. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.East C E, Begg L, Henshall N E. Local cooling for relieving pain from perineal trauma sustained during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(05):CD006304. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006304.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologistsʼ Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics . Practice Bulletin No. 165: Prevention and Management of Obstetric Lacerations at Vaginal Delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e1–e15. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stock L, Basham E, Gossett D R. Factors associated with wound complications in women with obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS) Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208:3270–3.27E8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lewicky-Gaupp C, Leader-Cramer A, Johnson L L. Wound complications after obstetric anal sphincter injuries. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1088–1093. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fitzpatrick M, Behan M, OʼConnell P R. A randomized clinical trial comparing primary overlap with approximation repair of third-degree obstetric tears. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:1220–1224. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.108880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Garcia V, Rogers R G, Kim S S. Primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter laceration: a randomized trial of two surgical techniques. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1697–1701. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Malouf A J, Norton C S, Engel A F. Long-term results of overlapping anterior anal-sphincter repair for obstetric trauma. Lancet. 2000;355:260–265. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Williams A, Adams E J, Tincello D G. How to repair an anal sphincter injury after vaginal delivery: results of a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2006;113:201–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Peirce C, Murphy C, Fitzpatrick M.Randomised controlled trial comparing early home biofeedback physiotherapy with pelvic floor exercises for the treatment of third-degree tears (EBAPT Trial) BJOG 20131201240–1247.discussion 1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schwandner T, Konig I R, Heimerl T. Triple target treatment (3 T) is more effective than biofeedback alone for anal incontinence: the 3 T-AI study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:1007–1016. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181db7738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Poen A C, Felt-Bersma R J, Dekker G A. Third degree obstetric perineal tears: risk factors and the preventive role of mediolateral episiotomy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:563–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb11533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Baghestan E, Irgens L M, Bordahl P E. Risk of recurrence and subsequent delivery after obstetric anal sphincter injuries. BJOG. 2012;119:62–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Elfaghi I, Johansson-Ernste B, Rydhstroem H. Rupture of the sphincter ani: the recurrence rate in second delivery. BJOG. 2004;111:1361–1364. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Harkin R, Fitzpatrick M, OʼConnell P R. Anal sphincter disruption at vaginal delivery: is recurrence predictable? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003;109:149–152. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(03)00008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Payne T N, Carey J C, Rayburn W F. Prior third- or fourth-degree perineal tears and recurrence risks. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1999;64:55–57. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(98)00207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Peleg D, Kennedy C M, Merrill D. Risk of repetition of a severe perineal laceration. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:1021–1024. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00556-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Basham E, Stock L, Lewicky-Gaupp C. Subsequent pregnancy outcomes after obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS) Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19:328–332. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e3182a5f98e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bek K M, Laurberg S. Risks of anal incontinence from subsequent vaginal delivery after a complete obstetric anal sphincter tear. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:724–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb13870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fynes M, Donnelly V, Behan M. Effect of second vaginal delivery on anorectal physiology and faecal continence: a prospective study. Lancet. 1999;354:983–986. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)11205-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Faltin D L, Otero M, Petignat P. Womenʼs health 18 years after rupture of the anal sphincter during childbirth: I. Fecal incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1255–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.10.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sze E H. Anal incontinence among women with one versus two complete third-degree perineal lacerations. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;90:213–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Laine K, Skjeldestad F E, Sandvik L. Incidence of obstetric anal sphincter injuries after training to protect the perineum: cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001649. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]