Abstract

Introduction

Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae are by far the most public health and urgent clinical problems with antibiotic resistance. They cause longer hospital stays, more expensive medical care, and greater mortality rates. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to indicate the prevalence of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Ethiopia.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted based on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines. Electronic databases like PubMed, Google Scholar, CINAHL, Wiley Online Library, African Journal Online, Science Direct, Embase, ResearchGate, Scopus, and the Web of Sciences were used to find relevant articles. In addition, the Joanna Briggs Institute quality appraisal tool was used to assess the quality of the included studies. Stata 14.0 was used for statistical analysis. Heterogeneity was assessed by using Cochran’s Q test and I2 statistics. In addition, publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot and Egger’s test. A random effect model was used to estimate the pooled prevalence. Sub-group and sensitivity analysis were also done.

Results

The overall pooled prevalence of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Ethiopia was 5.44% (95% CI 3.97, 6.92). The prevalence was highest [6.45% (95% CI 3.88, 9.02)] in Central Ethiopia, and lowest [(1.65% (95% CI 0.66, 2.65)] in the Southern Nations and Nationalities People Region. In terms of publication year, 2017–2018 had the highest pooled prevalence [17.44 (95% CI 8.56, 26.32)] and 2015–2016 had the lowest [2.24% (95% CI 0.87, 3.60)].

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis showed a high prevalence of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. So, to alter the routine use of antibiotics, regular drug susceptibility testing, strengthening the infection prevention approach, and additional national surveillance on the profile of carbapenem resistance and their determining genes among Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates are required.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO (2022: CRD42022340181).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12879-023-08237-5.

Keywords: Prevalence, Carbapenemase, Enterobacteriaceae, Ethiopia, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Bacterial antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is one of the major public health problems in the 21st century. It happens when changes in bacteria make the medications used to treat infections less effective [1]. In 2019, there were an estimated 4.95 (95% uncertainty level [UI], 3.62–6.57) million deaths associated with bacterial AMR, of which 1.27 million (95% UI, 0.911–1.71) were attributable to bacterial AMR. Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella pneumoniae were among the six most common pathogens associated with resistance-related deaths [2].

Infections caused by multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, like extended-spectrum-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae have been successfully treated with carbapenem antibiotics for a long time [3]. Carbapenems contain a beta-lactam ring that makes them more stable against the majority of β-lactamases [4]. According to Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines, meropenem, imipenem, ertapenem, and doripenem are used as therapies for infections caused by Enterobacteriaceae [5]. The emergence of Enterobacteriaceae producing carbapenemases has resulted in widespread resistance to carbapenems [6]. The production of carbapenemase enzymes, which are encoded by numerous genes and can be transmitted between Enterobacteriaceae via transferable genetic elements, is the primary mechanism for the development of carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae. From these, Class A Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase, Class B metallo-lactamase, and Class D OXA-lactamase are examples of commonly encountered enzymes [7].

The World Health Organization identifies Enterobacteriaceae as a significant category that causes drug-resistant illnesses [8, 9]. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) also described that CRE, such as Klebsiella species, Escherichia coli, and Enterobacter species are the most important developing resistance threats worldwide [10].

Isolates of Enterobacteriaceae that produce carbapenemase frequently exhibit multi-resistant strains due to their resistance to a wide range of different beta-lactam and non-beta lactam antibiotics [11]. From the standpoint of public health, carbapenemase-producing isolates are by far the most urgent clinical problem with antibiotic resistance [3]. There has been an alarming increase of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in recent years, predominantly K. pneumoniae [12, 13]. Compared to carbapenem susceptible Enterobacteriaceae, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) infections cause longer hospital stays, more expensive medical care, and greater mortality rates [14]. Therefore, the increasing prevalence of carbapenemase-producing strains is a significant issue, particularly in nations like Ethiopia [15].

Carbapenems are currently being used more frequently in Ethiopian healthcare institutions or by doctors as an empirical treatment. Because of this, there are still few effective treatments for severe CRE infections [16]. Emergences of Enterobacteriaceae that are resistant to carbapenems are a significant medical issue. The majority of countries are at risk of becoming the next victims of CRE. In order to stop the spread of such resistant microbes, infection prevention and control systems should be reinforced [17]. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to estimate the pooled prevalence of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Ethiopia.

Methods

Reporting and protocol registration

This Systematic Review and meta-analysis was reported using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [18]. The protocol was registered at International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) with registration number of CRD42022340181.

Data sources and search strategies

Systematic searches of electronic databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar, CINAHL, Wiley Online Library, African Journal Online, Science Direct, Embase, ResearchGate, Scopus, and the Web of Sciences were used to retrieve potentially eligible studies reporting the prevalence of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) in Ethiopia. In addition, the proceedings of annual research conferences and university repositories were screened. A snowball search was also conducted using the bibliographies of the identified studies to include additional relevant studies omitted during electronic database searches. The search was conducted from May 30, 2022, to July 15, 2022.

The following combination of key words were used to access all potentially eligible studies: “prevalence” OR “epidemiology” AND “carbapenemase-producing isolates” OR “CPE” OR “CRE” OR “carbapenem resistant” OR “multidrug-resistant” OR “antimicrobial resistance” AND “Enterobacteriaceae” OR “gram-negative bacteria” AND “Ethiopia”. The Boolean operators’ terms “OR” and “AND” were used as necessary.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Articles that fulfilled the following criteria were included in the final analysis: original articles published in peer-reviewed journals or grey literature, observational studies (cohort, cross-sectional and case control), articles published in English language, studies that reported prevalence of CPE in any region of Ethiopia, studies involving human/clinical samples, studies that accurately report the bacterial isolates of Enterobacteriaceae and their carbapenem resistance pattern based on the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), and European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) guidelines, studies published until July 15, 2022 were included.

Exclusion criteria

Qualitative studies, review articles, case reports, narrative reviews, conference abstracts with no full information or if authors have not responded to our inquiry on the full text, editorials, commentaries, letters to the editor, author replies, studies not involving human/clinical samples and studies that do not include quantitative data on the prevalence of CPE were excluded.

Study selection

EndNote version 20 software was used to import all articles that were found through searching electronic databases, conference proceedings, and the bibliographies of identified studies. Then, duplicates were eliminated. Based on the eligibility criteria, the title, abstract, and full text of each article were carefully screened by two independent reviewers. Disagreements between the two reviewers were settled through discussion of the inclusion of a third reviewer to select articles for the final review.

Quality assessment

Independent reviewers critically analyzed the included studies to make sure the findings were reliable and consistent. The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality appraisal tool adapted for cross-sectional studies was used to assess the quality of the included studies [19]. The tool consisted of eight criteria. Studies with a quality score of 50% or higher were considered to be of good quality and were included for the analysis.

Data extraction process

The required information were extracted and summarized using an extraction sheet in Microsoft Office Excel software. The key findings regarding the prevalence of CPE were extracted by three independent reviewers. The Microsoft Excel sheet was prepared under subheadings decided upon by all reviewers. The three reviewers cross-checked their findings carefully, and disagreement was resolved by discussion and repetition of the steps when necessary. The extracted data contains the name of the first author, publication year, region where the study was conducted, study area, study design, study population, sample size, diagnostic methods, specimen types, species of Enterobacteriaceae isolates, number of CPE isolates, and prevalence of CPE isolates.

Statistical methods and analysis

The extracted data was exported to STATA version 14.0 for statistical analysis. Cochran’s Q test and I2 statistics were used to quantify and assess the presence of heterogeneity between studies. The presence of heterogeneity was defined as I2 test statistic values greater than 50% [20] and p-value results from a Q test less than 0.05. A random effect model was used to estimate the pooled prevalence of CPE with a 95% confidence interval [21]. The results were presented using a forest plot. The funnel plot and Egger weighted regression test were used to assess the presence or absence of publication bias. The asymmetry of the funnel plot and a p-value of < 0.05 in Egger’s test were suggestive of the presence of significant publication bias. In addition, subgroup analysis was carried out based on region, year of publication, and city. Furthermore, sensitivity analysis was also performed to determine the impact of a single study on the overall pooled estimate.

Results

Description of included studies

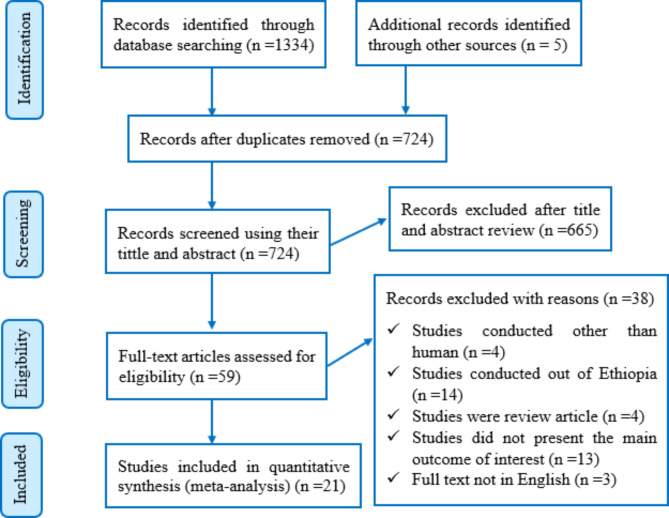

Database searches and other sources yielded a total of 1339 articles. From those articles, duplication resulted in the removal of 615 articles. A total of 724 papers were scrutinized for their titles and abstracts, and 665 studies were eliminated. A total of 59 full-text articles were then reviewed against the eligibility criteria. Following that, 38 full-text articles were excluded. Finally, only 21 articles were deemed potentially eligible and included in this review for the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the included studies for the systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of CPE in Ethiopia

Characteristics of the included studies

A total of 21 original articles reporting studies conducted in different regions of Ethiopia were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis (Tables 1 and 2). All the studies had a quality score greater than 50%. The majority of the included studies were reported from Addis Ababa (47.6%) [16, 22–30], followed by the Amhara Region (33.3%) [31–37]. Sidama [38] and the Oromia region [39] were represented by a single study. In terms of the study design, all studies were cross-sectional studies. A variety of clinical specimens, including blood, urine, stool, and other body fluids, were used by the authors. A total of 3,932 Enterobacteriaceae bacterial isolates were included. The studies reported numbers of isolated Enterobacteriaceae from different clinical samples ranging from 33 in Addis Ababa [26] to 404 in Gondar [36]. The highest prevalence of CPE (30.5%) was reported from Addis Ababa in 2019 [27], while the lowest (1%) was reported from Gondar in 2022 [36].

Table 1.

Distribution and characteristics of studies on CPE in Ethiopia

| Authors | Study area | Region | Pub year | Study design | Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desta et al. [25] | Addis Ababa | Central | 2016 | Cross -sectional | All hospitalized patients |

| Legese et al. [26] | Addis Ababa | Central | 2017 | Cross -sectional | Patients suspected of septicemia and UTIs |

| Beyene et al. [24] | Addis Ababa | Central | 2019 | Cross -sectional | Referred samples |

| Mitiku et al. [27] | Addis Ababa | Central | 2019 | Cross -sectional | Septicemia suspected under five children |

| Desalegn et al. [30] | Addis Ababa | Central | 2019 | Cross -sectional | Referred patients |

| Abdeta et al. [29] | Addis Ababa | Central | 2021 | Cross -sectional | Referred samples |

| Seman et al. [22] | Addis Ababa | Central | 2021 | Cross -sectional | Patients affected by urinary tract infection (UTI) |

| Tekele et al. [16] | Addis Ababa | Central | 2021 | Cross -sectional | All patients from both impatient and outpatient clinics |

| Seman et al. [23] | Addis Ababa | Central | 2022 | Cross -sectional | Adults and pediatric patients |

| Awoke et al. [28] | Addis Ababa | Central | 2022 | Cross -sectional | All patients from both impatient and outpatient clinics |

| Aklilu et al. [40] | Arba Minch | SNNPR | 2020 | Cross -sectional | Hospitalized patients with gastrointestinal colonization |

| Zakir et al. [41] | Arba Minch | SNNPR | 2022 | Cross -sectional | Neonates in intensive care units |

| Eshetie et al. [37] | Gondar | Amhara | 2015 | Cross -sectional | Symptomatic UTI suspected patients |

| Moges et al. [31] | Bahir Dar | Amhara | 2019 | Cross -sectional | Patients suspected for having bloodstream, UTI, wound and others infections |

| Alebel et al. [32] | Bahir Dar | Amhara | 2021 | Cross -sectional | Patients in intensive care units with symptoms for UTI, wound and others |

| Moges et al. [35] | Gondar, Dessie, and Debre Markos | Amhara | 2021 | Cross -sectional | Patients suspected of having bloodstream, UTI, wound and other infections |

| Worku et al. [36] | Gondar | Amhara | 2022 | Cross -sectional | Gastrointestinal tract complaint patients |

| Amare et al. [34] | Gondar | Amhara | 2022 | Cross -sectional | Asymptomatic food handlers working at the University of Gondar cafeteria |

| Tadesse et al. [33] | Bahir Dar | Amhara | 2022 | Cross -sectional | Patients symptomatic for bacterial infections |

| Alemayehu et al. [38] | Hawassa | Sidama | 2021 | Cross -sectional | All patients who visited the microbiology laboratory |

| Gashaw et al. [39] | Jimma | Oromia | 2018 | Cross -sectional | Patients had culture confirmed healthcare associated infections |

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of included articles describing CPE in Ethiopia

| Authors | Sample size | Diagnostic methods | No of isolates | Bacterial species | No (Prev) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desta et al. [25] | 267 | ROSCO Neo-Sensitabs | 267 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and K. oxytoca | 5 (2) |

| Legese et al. [26] | 322 | MHT | 33 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and Others | 4 (12.12) |

| Beyene et al. [24] | 947 | MHT | 238 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and Others | 5 (2) |

| Mitiku et al. [27] | 340 | mCIM | 59 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and Others | 18 (30.5) |

| Desalegn et al. [30] | 873 | mCIM | 154 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and Others | 6 (3.9) |

| Abdeta et al. [29] | 1,337 | mCIM | 293 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and Others | 14 (4.77) |

| Seman et al. [22] | 120 | HT and CIM | 120 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae, K. oxytoca, and Others | 8 (6.7) |

| Tekele et al. [16] | 312 | CIM | 312 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and Others | 8(2.6) |

| Seman et al. [23] | 2397 | CIM | 104 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae, K. oxytoca, and Others | 8 (7.7) |

| Awoke et al. [28] | 132 | mCIM | 132 | K. pneumoniae | 28 (21.2) |

| Aklilu et al. [40] | 421 | Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion | 421 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and Others | 6 (1.43) |

| Zakir et al. [41] | 212 | mCIM | 206 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and Others | 5 (2.42) |

| Eshetie et al. [37] | 442 | CHROM agar KPC medium | 183 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and Others | 5 (2.7) |

| Moges et al. [31] | 532 | MHT | 174 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and Others | 23 (13.2) |

| Alebel et al. [32] | 270 | mCIM | 71 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and Others | 12 (16.9) |

| Moges et al. [35] | 833 | MHT | 133 | E. coli, K. pneumonia, and Others | 8 (6) |

| Worku et al. [36] | 384 | mCIM | 404 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and Others | 4 (1) |

| Amare et al. [34] | 290 | mCIM | 347 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and Others, | 7 (2.4) |

| Tadesse et al. [33] | 384 | mCIM | 100 | E. coli, E. cloacae, K. pneumoniae, and Others | 6 (6) |

| Alemayehu et al. [38] | 103 | mCIM | 92 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae and Others | 5 (5.4) |

| Gashaw et al. [39] | 192 | Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion | 89 | E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and Others | 19 (21.3) |

HT, Hodge test; MHT, modified Hodge test; mCIM, modified carbapenem inactivation method; CIM, carbapenem inactivation method. #Others include Proteus spp., K. oxytoca, K. ozaenae, E. cloacae, Citrobacter spp, Enterobacter Spp., Salmonella spp., Serratia spp., and Morganella spp., No; number of CPE, Prev; prevalence of CPE

Prevalence of CPE in Ethiopia

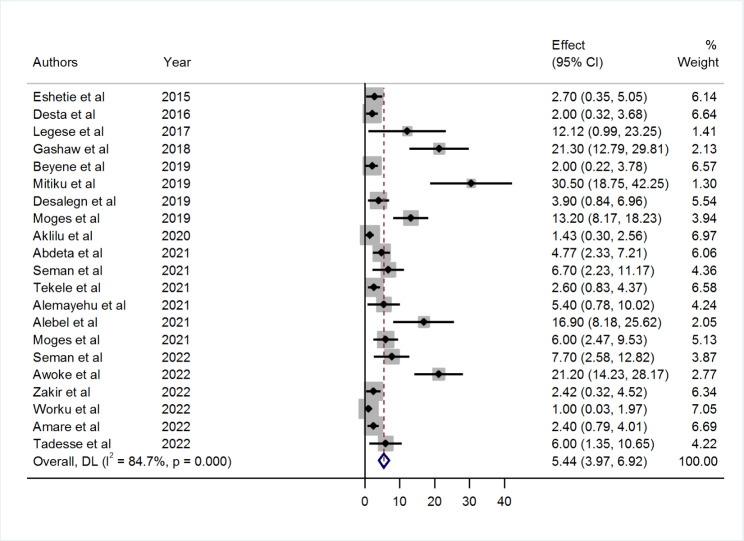

A greater disparity in the prevalence of CPE was revealed in the studies. The prevalence ranges from 1% (95% CI: 0.03, 1.97) reported in Gondar to 30.50% (95% CI: 18.75, 42.25) reported in Addis Ababa. The overall pooled prevalence of CPE in Ethiopia from the random effects model was 5.44% (95% CI: 3.97, 6.92). There was a high level of heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 84.7%) and the Q test (Tau-squared = 7.77, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot showing the pooled prevalence of CPE in Ethiopia from random-effect model analysis

Subgroup analysis of CPE prevalence in Ethiopia

The subgroup analysis by different regions of Ethiopia indicated that the highest pooled prevalence of 6.45% (95% CI 3.88, 9.02) was observed in Central Ethiopia, followed by 5.27% (95% CI 2.66, 7.88) in the Amhara region. On the other hand, the lowest prevalence of 1.65% (95% CI 0.66, 2.65) was reported in the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR). In addition, the subgroup analysis based on city revealed a prevalence of 11.35% (95% CI: 5.15, 17.59) in Bahir Dar, 6.45% (95% CI: 3.88, 9.02) in Addis Ababa, 1.9% (95% CI: 0.73, 3.08) in Gondar, and 1.65% (95% CI: 0.66, 2.65) in Arba Minch. Similarly, subgroup analysis based on the publication year of studies showed that the highest pooled prevalence of 17.44 (95% CI 8.56, 26.32) was reported in 2017–2018 followed by 6.60% (95% CI: 2.66, 10.55) in 2019–2020, and 5.30% (95% CI: 3.39, 7.20) in 2021–2022. The lowest prevalence of 2.24% (95% CI: 0.87, 3.60) was reported in 2015–2016 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of CPE by region, city and year of publication in Ethiopia

| Subgroup | No of studies | Pooled prevalence (95% CI) | Heterogeneity test (I2) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Central | 10 | 6.45 (3.88, 9.02) | 84.9% | < 0.001 |

| Amhara | 7 | 5.27 (2.66, 7.88) | 85.5% | < 0.001 | |

| SNNPR | 2 | 1.65 (0.66, 2.65) | 0.0% | 0.416 | |

| Total pooled | 19 | 4.92 (3.49, 6.36) | 83.3% | < 0.001 | |

| City | Addis Ababa | 10 | 6.45 (3.88, 9.02) | 84.9% | < 0.001 |

| Gondar | 4 | 1.9 (0.73, 3.08) | 36.4% | 0.194 | |

| Bahir Dar | 3 | 11.35 (5.15, 17.59) | 70.4% | 0.034 | |

| Arba Minch | 2 | 1.65 (0.66, 2.65) | 0.0% | 0.416 | |

| Total pooled | 19 | 4.86 (3.42, 6.29) | 83.3% | < 0.001 | |

| Publication year | 2015–2016 | 2 | 2.24 (0.87, 3.60) | 0.0% | 0.635 |

| 2017–2018 | 2 | 17.44 (8.56, 26.32) | 39.4% | 0.199 | |

| 2019–2020 | 5 | 6.60 (2.66, 10.55) | 90.8% | < 0.001 | |

| 2021–2022 | 12 | 5.30 (3.39, 7.20) | 82.9% | < 0.001 | |

| Total pooled | 21 | 5.44 (3.96, 6.92) | 83.6% | < 0.001 | |

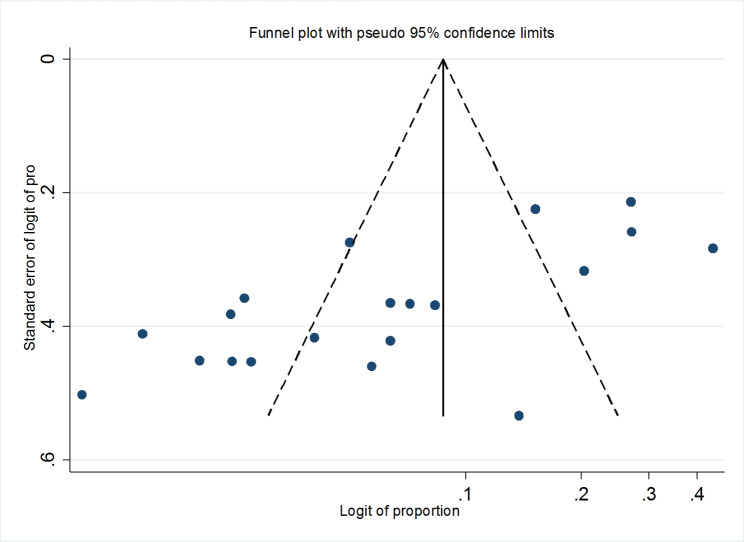

Publication bias

The selected studies were visually evaluated using a funnel plot for possible publication bias. The asymmetry of the funnel plot indicated the presence of publication bias, as more than 66% of the studies fell on the left side of the triangular region (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the result of Egger’s test also revealed a marginally significant publication bias (p < 0.01) (Table 4).

Fig. 3.

Funnel plot on the prevalence of CPE in Ethiopia

Table 4.

Egger’s test statistics of the prevalence of CPE in Ethiopia

| Std_Eff | Coef. | Std. Err. | T | P> |t| | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope | -1.17 | 0.44 | -2.64 | 0.016 | -2.10, -0.24 |

| Bias | 4.00 | 0.39 | 10.23 | 0.000 | 3.18, 4.82 |

Trim and fill analysis of pooled prevalence of CPE in Ethiopia

A trim and fill analysis was performed due to the presence of publication bias. After adding ten studies, the pooled prevalence of CPE in Ethiopia was 2.31% (95% CI: 0.68–3.94) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Trim and fill analysis of the prevalence of CPE in Ethiopia

| Method | Pooled est. | 95% CI | Asymptotic | No. of studies | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | z-value | p-value | |||

| Fixed | 2.556 | 2.071 | 3.042 | 10.323 | 0.000 | 21 |

| Random | 5.440 | 3.963 | 6.916 | 7.219 | 0.000 | |

| Test for heterogeneity: Q = 130.257 on 20 degrees of freedom (p = 0.000) | ||||||

| Moment-based estimate of between studies variance = 7.775 | ||||||

| Trimming estimator: Linear | ||||||

| Meta-analysis type: Fixed-effects model | ||||||

| Iteration | Estimate | Tn | # To trim | Diff | ||

| 1 | 2.556 | 198 | 8 | 231 | ||

| 2 | 2.079 | 213 | 10 | 30 | ||

| 3 | 1.972 | 218 | 10 | 10 | ||

| 4 | 1.972 | 218 | 10 | 0 | ||

| Filled | ||||||

| Meta-analysis | ||||||

| Method | Pooled est. | 95% CI | Asymptotic | No. of studies | ||

| Lower | Upper | z-value | p-value | |||

| Fixed | 1.972 | 1.503 | 2.442 | 8.240 | 0.000 | 31 |

| Random | 2.316 | 0.689 | 3.942 | 2.790 | 0.005 | |

| Test for heterogeneity: Q = 256.906 on 30 degrees of freedom (p = 0.000) | ||||||

| Moment-based estimate of between studies variance = 14.681 | ||||||

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was carried out using a random effects model to assess the impact of several studies on the combined estimate. The pooled prevalence that was obtained after individual studies were excluded was within the 95% CI of the total pooled estimate. This demonstrates that no single study had an impact on the total pooled effect magnitude (Table 6).

Table 6.

Sensitivity analysis of the prevalence of CPE in Ethiopia

| Study omitted | Estimate | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Seman et al. [22] | 5.37 | 3.86, 6.88 |

| Seman et al. [23] | 5.33 | 3.83, 6.82 |

| Legese et al. [26] | 5.32 | 3.84, 6.80 |

| Tekele et al. [16] | 5.75 | 4.16, 7.34 |

| Awoke et al. [28] | 4.74 | 3.38, 6.09 |

| Zakir et al. [41] | 5.73 | 4.16, 7.30 |

| Aklilu et al. [40] | 5.94 | 4.30, 7.58 |

| Tadesse et al. [33] | 5.41 | 3.90, 6.93 |

| Abdeta et al. [29] | 5.51 | 3.97, 7.05 |

| Amare et al. [34] | 5.79 | 4.19, 7.39 |

| Moges et al. [35] | 5.41 | 3.89, 6.92 |

| Worku et al. [36] | 5.94 | 4.32, 7.57 |

| Eshetie et al. [37] | 5.69 | 4.12, 7.25 |

| Alemayehu et al. [38] | 5.45 | 3.93, 6.96 |

| Gashaw et al. [39] | 4.93 | 3.53, 6.33 |

| Beyene et al. [24] | 5.79 | 4.20, 7.38 |

| Desta et al. [25] | 5.80 | 4.21, 7.40 |

| Mitiku et al. [27] | 4.92 | 3.54, 6.30 |

| Desalegn et al. [30] | 5.56 | 4.02, 7.10 |

| Moges et al. [31] | 4.96 | 3.54, 6.39 |

| Alebel et al. [32] | 5.11 | 3.67, 6.55 |

| Combined | 5.43 | 3.96, 6.91 |

Discussion

The current systematic review and meta-analysis was carried out to determine the pooled prevalence of CPE in Ethiopia. Antibiotic resistance among Enterobacteriaceae has been widely reported and has grown to represent a serious threat to the delivery of healthcare [42]. Due to their high levels of antibiotic resistance, carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) are challenging to treat since they are able to break down all beta-lactam medicines, including carbapenems, and render them ineffective [43]. Their high prevalence may also result in higher mortality, longer hospital stays, and increased consumption of healthcare services [44, 45]. Estimating the pooled prevalence of CPE is therefore a critical step to offering information on the temporal and geographic incidence of carbapenem resistance, as well as the extent of the problem, in order to develop a national public health response to these emerging pathogens.

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, the pooled prevalence of CPE in Ethiopia was 5.44% (95% CI: 3.97, 6.92). However, it was varied to 2.31% (95% CI: 0.68, 3.94) by adding ten studies to the trim and fill analysis. The observed high carbapenem resistance rate could be due to prior antimicrobial exposure, a history of hospitalization, the length of hospital stays, the presence of invasive devices, advanced age, and severe underlying diseases [46]. It could also potentially be attributable to drugs being prescribed without awareness of their susceptibility pattern or the introduction and spread of carbapenem-resistant bacterial strains from other places with high resistance rates. Repetitive, improper, and inaccurate use of antimicrobial drugs in empirical treatment, as well as inadequate infection control techniques, may also increase the prevalence of carbapenem resistant Enterobacteriaceae in the population.

The pooled estimate is comparable with the reports from Kuwait (4.9%) [47], Lebanon (5.19%) [48], Malaysia (5.74%) [49], Senegal (5.1%) [50], and the United Arab Emirates (4.6%) [51]. On the other hand, the finding is higher when compared to the findings of previous reports from eighteen European nations (2%) [52], South Korea (1.6%) [53], Belgium (3.5%) [54], Lebanon (3%) [55], and Afghanistan (3.4%) [56]. Nevertheless, the pooled prevalence report was lower than reports from Kuwait (8%) [57], Saudi Arabia (23.9%) [58], and Egypt (54.1%) [59]. This difference could be because of the use of different antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST) methods, target population, sample type, type and number of bacteria isolates, the definition used to classify presence of carbapenemase-producing isolates, antibiotic use policy variations, and geographical area. Additionally, the discrepancy could be attributed to differences in local antibiotic prescribing habits and infection control programs in various health care facilities [60].

The high degree of heterogeneity in the overall prevalence found in our analysis could be caused by a number of factors. As a result, we took into account post-hoc subgroup analysis by many factors, including region, city, and publication year of the study. Variations in the prevalence of CPE were observed in different regions of Ethiopia, with the highest in Central Ethiopia (6.45%) and the lowest in the SNNPR region (1.65%). Moreover, the sub-group analysis by city found the highest CPE prevalence in Bahir Dar (11.35%) and the lowest in Arba Minch (1.65%). Finally, the sub-group analysis by publication year of the study indicated that the highest prevalence of CPE was found in 2017–2018 (17.44%) and the lowest in 2015–2016 (2.24%). This discrepancy might be attributable to the study period, environmental factors, target population, type of sample, and type and number of bacteria isolates. Some factors were also mentioned as one of the reasons for the discrepancy in the prevalence of carbapenem resistant Enterobacteriaceae.

This review has certain strengths and limitations. It involved more than one reviewer. In addition, we employed a comprehensive search technique and attempted to investigate grey literature. Moreover, during this review, we have also strictly followed the PRISMA guidelines. However, our meta-analysis has limitations, such as the presence of significant heterogeneity even after subgroup analysis for some variables. Also, only studies published in English were included, which may expose the study to language bias. As a result, the meta-analysis revealed significant heterogeneity, with some CIs overlapping in the subgroup analysis. So, some estimations could be impacted by group interaction. On the other hand, it was unable to assess factors associated with the pooled prevalence of CPE. Furthermore, all of the studies included in this systematic review and meta-analysis were cross-sectional studies, and the outcome variability may be influenced by other confounding variables. These limitations may have an impact on the findings reported in this review regarding the overall prevalence of CPE in Ethiopia.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis showed a high prevalence of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Ethiopia. As a result, steps should be taken to reduce the spread of CPE. Resistance to third-generation cephalosporins is also a major issue. However, it is necessary to improve the infection prevention strategy and conduct additional national surveillance on the profile of carbapenemase production and their determining genes among Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to offer our profound gratitude to the authors of the original articles as well as the study participants. Finally, we would like to thank everyone who helped us perform this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Abbreviations

- CLSI

Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute

- CPE

Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae

- CRE

Carbapenem Resistant Enterobacteriaceae

- SNNPR

Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region

Author Contribution

Ermiyas A. conceptualize and design the study and search for articles, screen, and extract data, and evaluate the quality of the articles included. In addition, perform statistical analysis and write the manuscript. Temesgen F., Alemu G., Nuhamin AT., Hussen E., Endris E., Mesfin F., Habtye B., Ousman M., Mihret T., Daniel G., Habtu D., and Mengistie YG. involved in searching articles, screening and extracting data, assessing the quality of included data, and assisting in the analysis and reviewing, and editing the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final draft of the manuscript before it was submitted for publication.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data Availability

All the datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the manuscript.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declared that no competing interest for their work.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ermiyas Alemayehu, Email: ermiyas0009@gmail.com.

Temesgen Fiseha, Email: temafiseha@gmail.com.

Alemu Gedefie, Email: alemugedefie@gmail.com.

Nuhamin Alemayehu Tesfaye, Email: nuham4629@gmail.com.

Hussen Ebrahim, Email: husshosam@gmail.com.

Endris Ebrahim, Email: endris.index@gmail.com.

Mesfin Fiseha, Email: mesfinfiseha40@gmail.com.

Habtye Bisetegn, Email: habtiye21@gmail.com.

Ousman Mohammed, Email: ousmanabum@gmail.com.

Mihret Tilahun, Email: tilahunmihret21@gmail.com.

Daniel Gebretsadik, Email: gebretsadikd@gmail.com.

Habtu Debash, Email: habtudebash@gmail.com.

Mengistie Yirsaw Gobezie, Email: zemen.girum@gmail.com.

References

- 1.O’Neill J. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. 2016.

- 2.Murray CJ, Ikuta KS, Sharara F, Swetschinski L, Aguilar GR, Gray A, et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet. 2022;399(10325):629–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nordmann P, Gniadkowski M, Giske C, Poirel L, Woodford N, Miriagou V, et al. Identification and screening of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(5):432–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meletis G. Carbapenem resistance: overview of the problem and future perspectives. Therapeutic Adv Infect disease. 2016;3(1):15–21. doi: 10.1177/2049936115621709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CLSI. Clinical and laboratory standards institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 2018.

- 6.Nordmann P, Dortet L, Poirel L. Carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae: here is the storm! Trends Mol Med. 2012;18(5):263–72. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diene SM, Rolain J-M. Carbapenemase genes and genetic platforms in gram-negative bacilli: Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter species. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(9):831–8. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . WHO priority pathogens list for R&D of new antibiotics. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon MA, Feasey NA, Nyirenda TS, Graham SM. Nontyphoid salmonella disease. Hunter’s Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Diseases: Elsevier; 2020. p. 500-6.

- 10.Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States., 2019: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centres for Disease Control and Prevention; 2019.

- 11.Manageiro V, Romão R, Moura IB, Sampaio DA, Vieira L, Ferreira E, et al. Molecular epidemiology and risk factors of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates in portuguese hospitals: results from european survey on carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (EuSCAPE) Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2834. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Logan LK, Weinstein RA. The epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: the impact and evolution of a global menace. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(suppl1):28–S36. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pitout JD, Nordmann P, Poirel L. Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, a key pathogen set for global nosocomial dominance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(10):5873–84. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01019-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Duin D, Paterson DL. Multidrug-resistant bacteria in the community: trends and lessons learned. Infect disease Clin. 2016;30(2):377–90. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sultan BA, Khan E, Hussain F, Nasir A, Irfan S. Effectiveness of modified Hodge test to detect NDM-1 carbapenemases: an experience from Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013;63(8):955–60. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tekele SG, Teklu DS, Legese MH, Weldehana DG, Belete MA, Tullu KD et al. Multidrug-Resistant and Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BioMed Research International. 2021;2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Friedman ND, Carmeli Y, Walton AL, Schwaber MJ. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a strategic roadmap for infection control. Infect control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(5):580–94. doi: 10.1017/ice.2017.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst reviews. 2021;10(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munn Z, Moola S, Riitano D, Lisy K. The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. Int J health policy Manage. 2014;3(3):123. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seman A, Sebre S, Awoke T, Yeshitela B, Asseffa A, Asrat D, et al. The magnitude of carbapenemase and ESBL producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates from patients with urinary tract infections at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Teaching Hospital. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Springer; 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seman A, Mihret A, Sebre S, Awoke T, Yeshitela B, Yitayew B, et al. Prevalence and molecular characterization of extended spectrum β-Lactamase and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates from bloodstream infection suspected patients in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Infect Drug Resist. 2022;15:1367. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S349566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beyene D, Bitew A, Fantew S, Mihret A, Evans M. Multidrug-resistant profile and prevalence of extended spectrum β-lactamase and carbapenemase production in fermentative gram-negative bacilli recovered from patients and specimens referred to National Reference Laboratory, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(9):e0222911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desta K, Woldeamanuel Y, Azazh A, Mohammod H, Desalegn D, Shimelis D, et al. High gastrointestinal colonization rate with extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in hospitalized patients: emergence of carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(8):e0161685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Legese MH, Weldearegay GM, Asrat D. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae among ethiopian children. Infect drug Resist. 2017;10:27. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S127177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitiku M, Ayenew Z, Desta K. Multi-drug resistant, extended spectrum beta-lactamase and carbapenemase producing bacterial isolates among septicemia suspected under five children in Tikur Anbesa Specialized Hospital. Addis Ababa Ethiopia: Cross-sectional study; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Awoke T, Teka B, Aseffa A, Sebre S, Seman A, Yeshitela B, et al. Detection of bla KPC and bla NDM carbapenemase genes among Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Dominance of bla NDM. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(4):e0267657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0267657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdeta A, Bitew A, Fentaw S, Tsige E, Assefa D, Lejisa T, et al. Phenotypic characterization of carbapenem non-susceptible gram-negative bacilli isolated from clinical specimens. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(12):e0256556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Desalegn Y. Multidrug resistance among fermentative and non-fermentative gram-negative bacilli isolated from clinical specimens at Arsho Advanced Medical Laboratory, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 2019.

- 31.Moges F, Eshetie S, Abebe W, Mekonnen F, Dagnew M, Endale A, et al. High prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing gram-negative pathogens from patients attending Felege Hiwot Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Bahir Dar, Amhara region. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(4):e0215177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alebel M, Mekonnen F, Mulu W. Extended-spectrum β-Lactamase and carbapenemase producing gram-negative bacilli infections among patients in intensive care units of Felegehiwot Referral Hospital: a prospective cross-sectional study. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:391. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S292246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tadesse S, Mulu W, Genet C, Kibret M, Belete MA. Emergence of high prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae species among patients in Northwestern Ethiopia Region. BioMed Research International. 2022;2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Amare A, Eshetie S, Kasew D, Moges F. High prevalence of fecal carriage of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae among food handlers at the University of Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(3):e0264818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moges F, Gizachew M, Dagnew M, Amare A, Sharew B, Eshetie S, et al. Multidrug resistance and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing gram-negative bacteria from three Referral Hospitals of Amhara region, Ethiopia. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2021;20(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12941-021-00422-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Worku M, Getie M, Moges F, Mehari AG. Extended-Spectrum beta-lactamase-and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae family of bacteria from diarrheal Stool samples in Northwest Ethiopia. Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Infectious Diseases. 2022;2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Eshetie S, Unakal C, Gelaw A, Ayelign B, Endris M, Moges F. Multidrug resistant and carbapenemase producing Enterobacteriaceae among patients with urinary tract infection at referral hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Antimicrob Resist Infect control. 2015;4(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13756-015-0054-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alemayehu T, Asnake S, Tadesse B, Azerefegn E, Mitiku E, Agegnehu A et al. Phenotypic detection of carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacilli from a clinical specimen in Sidama, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study.Infection and Drug Resistance. 2021:369–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Gashaw M, Berhane M, Bekele S, Kibru G, Teshager L, Yilma Y, et al. Emergence of high drug resistant bacterial isolates from patients with health care associated infections at Jimma University medical center: a cross sectional study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13756-018-0431-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aklilu A, Manilal A, Ameya G, Woldemariam M, Siraj M. Gastrointestinal tract colonization rate of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and associated factors among hospitalized patients in Arba Minch General Hospital, Arba Minch, Ethiopia. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:1517. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S239092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zakir A, Regasa Dadi B, Aklilu A, Oumer Y. Investigation of Extended-spectrum β-lactamase and carbapenemase producing gram-negative bacilli in rectal swabs collected from neonates and their associated factors in neonatal intensive care units of Southern Ethiopia.Infection and Drug Resistance. 2021:3907–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Almugadam B, Ali N, Ahmed A, Ahmed E, Wang L. Prevalence and antibiotics susceptibility patterns of carbapenem resistant Enterobacteriaceae. J Bacteriol Mycol Open Access. 2018;6(3):187–90. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huttner A, Harbarth S, Carlet J, Cosgrove S, Goossens H, Holmes A, et al. Antimicrobial resistance: a global view from the 2013 World Healthcare-Associated Infections Forum. Antimicrob Resist Infect control. 2013;2(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/2047-2994-2-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu Y, Gu B, Huang M, Liu H, Xu T, Xia W, et al. Epidemiology of carbapenem resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) during 2000–2012 in Asia. J Thorac disease. 2015;7(3):376. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.12.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wailan AM, Paterson DL, Kennedy K, Ingram PR, Bursle E, Sidjabat HE. Genomic characteristics of NDM-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates in Australia and their bla NDM genetic contexts. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(1):136–41. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01243-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Loon K, Voor in ‘t holt AF, Vos MC. A systematic review and meta-analyses of the clinical epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2018;62(1):e01730-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Jamal WY, Albert MJ, Khodakhast F, Poirel L, Rotimi VO. Emergence of new sequence type OXA-48 carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Kuwait. Microb Drug Resist. 2015;21(3):329–34. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2014.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hamze M. Epidemiology and antibiotic susceptibility patterns of Carbapenem Resistant gram negative bacteria isolated from two tertiary care hospitals in North Lebanon: carbapenem resistant gram negative bacteria in North Lebanon.The International Arabic Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2018;8(2).

- 49.Zaidah AR, Mohammad NI, Suraiya S, Harun A. High burden of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) fecal carriage at a teaching hospital: cost-effectiveness of screening in low-resource setting. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017;6(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s13756-017-0200-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Makhtar C, Mamadou TM, Awa B-D, Assane D, Halimatou D-N, Farba K, et al. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates in a senegalese teaching hospital: a cross sectional study. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2017;11(44):1600–5. doi: 10.5897/AJMR2017.8716. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moubareck CA, Mouftah SF, Pál T, Ghazawi A, Halat DH, Nabi A, et al. Clonal emergence of Klebsiella pneumoniae ST14 co-producing OXA-48-type and NDM carbapenemases with high rate of colistin resistance in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;52(1):90–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sader HS, Castanheira M, Flamm RK, Mendes RE, Farrell DJ, Jones RN. Tigecycline activity tested against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae from 18 european nations: results from the sentary surveillance program (2010–2013) Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;83(2):183–6. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee H-J, Choi J-K, Cho S-Y, Kim S-H, Park SH, Choi S-M, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: prevalence and risk factors in a single community-based hospital in Korea. Infect Chemother. 2016;48(3):166–73. doi: 10.3947/ic.2016.48.3.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang T-D, Berhin C, Bogaerts P, Glupczynski Y, group ams, Caddrobi J, et al. Prevalence and mechanisms of resistance to carbapenems in Enterobacteriaceae isolates from 24 hospitals in Belgium. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(8):1832–7. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moghnieh R, Araj GF, Awad L, Daoud Z, Mokhbat JE, Jisr T, et al. A compilation of antimicrobial susceptibility data from a network of 13 lebanese hospitals reflecting the national situation during 2015–2016. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2019;8(1):1–17. doi: 10.1186/s13756-019-0487-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mende K, Beckius ML, Zera WC, Onmus-Leone F, Murray CCK, Tribble DR. Low prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae among wounded military personnel.US Army Medical Department Journal. 2017(2–17):12. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Jamal WY, Albert MJ, Rotimi VO. High prevalence of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-1 (NDM-1) producers among carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Kuwait. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3):e0152638. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Faidah HS, Momenah AM, El-Said HM, Barhameen AA, Ashgar SS, Johargy A, et al. Trends in the annual incidence of carbapenem resistant among gram negative bacilli in a large teaching hospital in Makah City, Saudi Arabia. J Tuberculosis Res. 2017;5(04):229. doi: 10.4236/jtr.2017.54024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kotb S, Lyman M, Ismail G, Abd El Fattah M, Girgis SA, Etman A, et al. Epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in egyptian intensive care units using national healthcare–associated infections surveillance data, 2011–2017. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;9(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13756-019-0639-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dahab R, Ibrahim AM, Altayb HN. Phenotypic and genotypic detection of carbapenemase enzymes producing gram-negative bacilli isolated from patients in Khartoum State. F1000Research. 2017;6(1656):1656. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.12432.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the manuscript.