Abstract

Escherichia coli J96 is a uropathogen having both broad similarities to and striking differences from nonpathogenic, laboratory E. coli K-12. Strain J96 contains three large (>100-kb) unique genomic segments integrated on the chromosome; two are recognized as pathogenicity islands containing urovirulence genes. Additionally, the strain possesses a fourth smaller accessory segment of 28 kb and two deletions relative to strain K-12. We report an integrated physical and genetic map of the 5,120-kb J96 genome. The chromosome contains 26 NotI, 13 BlnI, and 7 I-CeuI macrorestriction sites. Macrorestriction mapping was rapidly accomplished by a novel transposon-based procedure: analysis of modified minitransposon insertions served to align the overlapping macrorestriction fragments generated by three different enzymes (each sharing a common cleavage site within the insert), thus integrating the three different digestion patterns and ordering the fragments. The resulting map, generated from a total of 54 mini-Tn10 insertions, was supplemented with auxanography and Southern analysis to indicate the positions of insertionally disrupted aminosynthetic genes and cloned virulence genes, respectively. Thus, it contains not only physical, macrorestriction landmarks but also the loci for eight housekeeping genes shared with strain K-12 and eight acknowledged urovirulence genes; the latter confirmed clustering of virulence genes at the large unique accessory chromosomal segments. The 115-kb J96 plasmid was resolved by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis in NotI digests. However, because the plasmid lacks restriction sites for the enzymes BlnI and I-CeuI, it was visualized in BlnI and I-CeuI digests only of derivatives carrying plasmid inserts artificially introducing these sites. Owing to an I-SceI site on the transposon, the plasmid could also be visualized and sized from plasmid insertion mutants after digestion with this enzyme. The insertional strains generated in construction of the integrated genomic map provide useful physical and genetic markers for further characterization of the J96 genome.

Bacterial urinary tract infections (UTI) are second in incidence only to those causing respiratory infections. They are most commonly seen for adult females but also observed for adult males and children. By the age of 30, one in four women will have experienced an acute uncomplicated UTI (15). Following the first infection, as many as 27% will get a second infection within 6 months (15). A common cause is ascending infection by enteric bacteria (27). A select subset of Escherichia coli strains possessing certain virulence factors for attachment and infectivity account for the majority of severe cases. The uropathogenic strain J96 (O4:K6:H5), isolated from a human pyelonephritis patient (23), was characterized by its unique binding attribute of d-mannose-resistant hemagglutination of human erythrocytes mediated by pyelonephritis-associated pili (pap) (10). Subsequent studies have identified this strain as encoding four different adherence factors (products of pap, prs, foc, and fim), two alpha-hemolysins, and the cytotoxic necrotizing factor type 1 (10). Fewer UTI E. coli strains have S fimbriae (sfa) that recognize sialyl(α2-3)β-Gal on receptors (19), cross-talk regulation between prf and sfa (33), or binding of the globoside series of glycosphingolipids Gal(α1-4)Galβ- to sheep erythrocytes and human uroepithelial cells (26). Further, several of these virulence determinants are linked to particular chromosomal regions, termed pathogenicity islands I and II (Pai-I and Pai-II) (43). More recently, it has been suggested that the rarely occurring pap adhesin types found in J96 represent a clonal group that may be associated epidemiologically with certain disease manifestations (26).

The J96 genome size, of 5,120 kb, is near the upper limit of the range for natural E. coli isolates reported by Bergthorsson and Ochman (1a). By multilocus electrophoretotyping, strain J96 is most closely related to three isolates from that study (ECOR 4, 13, and 14) with sizes of 4,580 to 4,950 kb; one of these (ECOR 14) was also uropathogenic, although the others were not known to be pathogens (2). Size discrepancies between the genomes of strain J96 and other E. coli strains, including laboratory strain K-12, are partially accounted for by two large chromosomal additions that are specific to J96-like strains (10, 11, 20). Correspondingly, two J96–K-12 polymorphisms at 64 and 94 min, measured by the crossing of macrorestriction landmarks between strains (37), occur at virulence genes carried at the loci as Pai-I and Pai-II (10, 11, 20). Although initial detection of these pathogenicity islands in strain J96 relied on these genes cloned by their virulence phenotypes along with subsequent identification of overlapping cosmids (43), detection of them has been carried out completely independently of virulence gene phenotypes by the technique of genetic clamping (37).

Genomic macrorestriction maps have been constructed by strictly physical DNA analyses alone or by a combination of physical and genetic analyses, each method having benefits and pitfalls (13, 38, 39). In every method, however, there is the requirement for overlapping or second-dimension data that will allow the ordering of anonymous macrorestriction fragments, for example, with double enzymatic digests (12) or through hybridization analysis with cloned sequences that integrate genetic and physical data (39). Specialized transposable elements carrying a battery of rare restriction sites (29) provide the opportunity for similar overlapping data because they serve to integrate at transposon insertion sites the macrorestriction patterns generated by different rare-cutter enzymes (36). That is, the use of more than one enzyme (in this case, NotI, BlnI, and I-CeuI) for restriction of genomic DNAs of multiple insertion-bearing strains provides overlapping or second-dimension data for ordering the fragments from individual enzyme digests. Collection of this type of overlapping data also reveals the presence of plasmids and the comigration of multiple chromosomal fragments as single bands in the enzyme digestion patterns. Finally, the insertions used in the mapping also represent useful genetic and physical landmarks for more detailed analysis of the genome.

Recently, we have identified two additional accessory chromosomal segments and two deletions within uropathogenic E. coli J96 relative to the nonpathogenic strain K-12 (37). In order to identify and/or verify the sizes and locations of these elements (and those of Pai-I and Pai-II), we have constructed a genomic map of strain J96. We demonstrate that the general method for de novo mutations inserting mini-Tn10 transposable elements (36) provides a rapid means for characterizing the J96 genome. Further, the specific Tn10dRCP2 insertional variants used to construct the genomic map provide a means for identifying other pathogen-specific DNA sequences by comparative macrorestriction analysis (37). This provides a platform for a further comparison within the subgroup of uropathogens that might reveal strain-specific DNAs that contribute to the diversity of epidemiologic associations (17, 25, 45).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains in this study.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Tables 1, 2, and 3.

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid (source or reference) | Description | Distance from thrA (kb) |

|---|---|---|

| Parent strains | ||

| J96 (Rod Welsch) | Uropathogenic E. coli | |

| MG1655 (1) | E. coli K-12 prototype | |

| Plasmids | ||

| Bacillus subtilis pGI290 (29) | ||

| Bacillus subtilis pGI300 (29) | ||

| χM4355 (this study) | pJK275 with Tn10dKanRCP2; Kmr; J96 115-kb plasmid | |

| χM4356 (this study) | pJK308 with Tn10dKanRCP2; Kmr; J96 115-kb plasmid | |

| Insertion mutants (this study) | ||

| J96::Tn10dKanRCP2 Kmr strains | ||

| χM4302 | zab-353 | 80 |

| χM4303 | zag-361 | 283 |

| χM4305 | zbb-414 | 513 |

| χM4306 | abf-355 | 668 |

| χM4307 | zbg-411 | 753 |

| χM4308 | zbh-341 | 830 |

| χM4309 | zbj-354 | 912 |

| χM4310 | zcb-527 | 982 |

| χM4311 | zcc-346 | 1,025 |

| χM4312 | zce-312 | 1,155 |

| χM4313 | zcg-384 | 1,323 |

| χM4314 | zch-313 | 1,411 |

| χM4315 | zda-380 | 1,505 |

| χM4316 | zdc-332 | 1,612 |

| χM4317 | zdd-606 | 1,628 |

| χM4318 | zdf-306 | 1,746 |

| χM4319 | zdg-406 | 1,785 |

| χM4320 | zdi-415 | 1,853 |

| χM4321 | zdj-547 | 1,880 |

| χM4323 | ilv-624 | 1,988 |

| χM4324 | zef-396 | 2,085 |

| χM4325 | zeh-301 | 2,243 |

| χM4326 | zej-350 | 2,383 |

| χM4327 | zfa-320 | 2,398 |

| χM4328 | zfb-318 | 2,494 |

| χM4329 | zfd-546 | 2,551 |

| χM4330 | phe-625 | 2,598 |

| χM4331 | zff-423 | 2,653 |

| χM4332 | met-621 | 2,713 |

| χM4333 | cys-626 | 2,718 |

| χM4334 | zfh-458 | 2,723 |

| χM4335 | zfj-402 | 2,786 |

| χM4336 | zga-351 | 2,873 |

| χM4337 | zgd-392 | 3,046 |

| χM4338 | zge-312 | 3,106 |

| χM4339 | zgf-324 | 3,176 |

| χM4340 | zgi-338 | 3,354 |

| χM4341 | arg-622 | 3,375 |

| χM4345 | thr-627 | 3,858 |

| χM4346 | zhj-363 | 3,928 |

| χM4347 | zib-367 | 4,040 |

| χM4348 | cys-620 | 4,060 |

| χM4349 | zic-532 | 4,105 |

| χM4350 | zie-436 | 4,195 |

| χM4351 | pro-623 | 4,215 |

| χM4354 | zjj-350 | 4,975 |

| J96::Tn10dSpcRCP2 Spr strains | ||

| χM4301 | zaa-655 | 5 |

| χM4304 | zaj-629 | 413 |

| χM4322 | zec-644 | 1,968 |

| χM4342 | zha-647 | 3,543 |

| χM4343 | zhg-641 | 3,723 |

| χM4344 | zhh-643 | 3,833 |

| χM4352 | zjc-633 | 4,525 |

| χM4353 | zjf-632 | 4,750 |

TABLE 2.

Macrorestriction mapping of J96 with de novo insertions of Tn10dRCP2

| Strain | Fragment interrupted (CCW position, CW position)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| NotI | BlnI | I-CeuI | |

| χM4301 | EN (270, 20) | GB (80, 200) | GC (890, 200) |

| χM4302 | CN (60, 290) | GB (150, 130) | GC (960, 130) |

| χM4303 | CN (260, 100) | AB (75, 1,585) | AC (75, 2,275) |

| χM4304 | GN (35, 210) | AB (200, 1,460) | AC (200, 2,150) |

| χM4305 | GN (135, 115) | AB (300, 1,360) | AC (300, 2,050) |

| χM4306 | NN (45, 110) | AB (450, 1,210) | AC (450, 1,900) |

| χM4307 | NN (135, 20) | AB (530, 1,130) | AC (530, 1,820) |

| χM4308 | PN (55, 85) | AB (610, 1,050) | AC (610, 1,740) |

| χM4309 | PN (130, 10) | AB (690, 970) | AC (690, 1,660) |

| χM4310 | MN (55, 100) | AB (760, 900) | AC (760, 1,590) |

| χM4311 | MN (100, 50) | AB (800, 860) | AC (800, 1,550) |

| χM4312 | DN (90, 200) | AB (930, 730) | AC (930, 1,420) |

| χM4313 | DN (245, 45) | AB (1,100, 550) | AC (1,100, 1,250) |

| χM4314 | JN (40, 190) | AB (1,190, 460) | AC (1,190, 1,160) |

| χM4315 | JN (140, 95) | AB (1,285, 375) | AC (1,285, 1,065) |

| χM4316 | RN (15, 95) | AB (1,390, 270) | AC (1,390, 960) |

| χM4317 | RN (30, 75) | AB (1,405, 255) | AC (1,405, 945) |

| χM4318 | SN (15, 100) | AB (1,525, 135) | AC (1,525, 825) |

| χM4319 | SN (55, 55) | AB (1,560, 100) | AC (1,560, 790) |

| χM4320 | TN (10, 90) | AB (1,630, 30) | AC (1,630, 720) |

| χM4321 | TN (40, 60) | AB (1,655, 5) | AC (1,655, 695) |

| χM4322 | HN (20, 230) | CB (10, 600) | AC (1,750, 600) |

| χM4323 | HN (40, 210) | CB (30, 580) | AC (1,770, 580) |

| χM4324 | HN (125, 125) | CB (110, 500) | AC (1,850, 500) |

| χM4325 | LN (20, 145) | CB (265, 345) | AC (2,005, 345) |

| χM4326 | LN (160, 5) | CB (405, 205) | AC (2,145, 205) |

| χM4327 | ON (10, 145) | CB (420, 190) | AC (2,160, 190) |

| χM4328 | ON (110, 45) | CB (510, 95) | AC (2,255, 95) |

| χM4329 | KN (15, 165) | CB (570, 40) | AC (2,310, 40) |

| χM4330 | KN (65, 115) | EB (5, 430) | BC (5, 885) |

| χM4331 | KN (120, 60) | EB (60, 375) | BC (60, 830) |

| χM4332 | ZN (4, 6) | EB (120, 320) | BC (120, 770) |

| χM4333 | ZN (8, 2) | EB (125, 315) | BC (125, 765) |

| χM4334 | UN (5, 90) | EB (130, 310) | BC (130, 760) |

| χM4335 | UN (70, 25) | EB (190, 245) | BC (190, 700) |

| χM4336 | FN (60, 210) | EB (280, 155) | BC (280, 610) |

| χM4337 | FN (240, 30) | JB (20, 75) | BC (445, 445) |

| χM4338 | BN (25, 685) | JB (85, 10) | BC (505, 385) |

| χM4339 | BN (95, 615) | FB (60, 305) | BC (575, 305) |

| χM4340 | BN (270, 440) | FB (235, 125) | BC (755, 125) |

| χM4341 | BN (290, 420) | FB (255, 105) | BC (780, 105) |

| χM4342 | BN (440, 270) | DB (70, 430) | CC (70, 430) |

| χM4343 | BN (625, 85) | DB (250, 250) | CC (250, 250) |

| χM4344 | VN (25, 15) | DB (360, 140) | CC (360, 140) |

| χM4345 | IN (20, 220) | DB (380, 120) | CC (380, 120) |

| χM4346 | IN (90, 150) | DB (450, 50) | CC (450, 50) |

| χM4347 | IN (195, 45) | IB (65, 50) | DC (65, 50) |

| χM4348 | IN (215, 25) | IB (85, 30) | DC (85, 30) |

| χM4349 | WN (25, 10) | HB (5, 130) | EC (5, 130) |

| χM4350 | AN (80, 680) | HB (95, 40) | EC (95, 40) |

| χM4351 | AN (100, 660) | HB (115, 20) | EC (115, 20) |

| χM4352 | AN (410, 350) | BB (250, 560) | GC (250, 840) |

| χM4353 | AN (635, 125) | BB (475, 335) | GC (475, 615) |

| χM4354 | EN (100, 200) | BB (700, 110) | GC (700, 390) |

CCW, counterclockwise; CW, clockwise. Positions are given in kilobases.

TABLE 3.

Strains used in the identification of plasmid DNA in the macrorestriction digests of J96

| Strain | Fragment interrupted

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| NotIa | BlnI | I-CeuI | |

| χM4357 | QN (25, 90) | None; 115-kb plasmid | None; 115-kb plasmid |

| χM4358 | QN (55, 55) | None; 115-kb plasmid | None; 115-kb plasmid |

Numbers in parentheses are the counterclockwise and clockwise positions, respectively, in kilobases.

Microbiological techniques.

Bacterial strains were grown in Luria-Bertani medium (LB) with aeration or on solid LB or M9-glucose (32). Media were supplemented with kanamycin (25 μg/ml) or spectinomycin (100 μg/ml) as required. Cultures were incubated at 37°C. Cells were stored long-term by suspending them in LB-glycerol (80%/20% [vol/vol]) and cooling them to −80°C. Bacteriophage stocks were grown and stored as described by Sternberg and Maurer (42). De novo insertion mutants of E. coli strain J96 containing single Tn10dKanRCP2 or Tn10dSpcRCP2 insertions were generated by electroporation with plasmid pGI290 or pGI300, respectively, as previously described for strain K-12 (36). Double insertion mutants of strain MG1655 and single and double insertion mutants of strain J96 were generated by transducing recipient strains with P1Δdamrev6 lysates of MG1655 insertion mutants (36). Each Tn10dRCP2 insertion was mapped, and the genome structure was assessed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) following NotI, BlnI, or I-CeuI digestion. Genome structure, assessed by PFGE in up to six independent isolates from each transduction, was used to confirm P1 transduction fidelity and lack of transduction-associated rearrangements.

PFGE.

Genomic DNAs were purified from 5-ml overnight cultures of wild-type and insertionally mutagenized E. coli strain J96 in a manner suitable for yielding macrorestriction fragments (50 to 1,000 kb), as described previously (36). After digestion of agarose-embedded DNAs with I-CeuI (New England BioLabs, Beverly, Mass.) for 1 h, NotI (New England BioLabs) for 3 to 4 h, or BlnI (Panvera, Madison, Wis.) overnight, according to the manufacturers' directions, and after reaction buffer decanting, dots were melted (70°C) and gently pipetted with 200-μl tips into sample wells in 1.3% (wt/vol) Bio-Rad (Hercules, Calif.) PFGE-approved agarose (FMC, Portland, Maine) gels for electrophoresis in 0.5× TBE buffer (0.045 M Tris [pH 8.0] containing 0.045 M boric acid and 0.001 M EDTA) in a contour-clamped homogeneous electric field PFGE apparatus (DRIII; Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Pulsed-field ramping parameters were determined as described elsewhere (3). After electrophoresis of samples with Megabase I and/or II DNA standards (Gibco/BRL, Bethesda, Md.), fragment sizes were quantitated as described elsewhere (21).

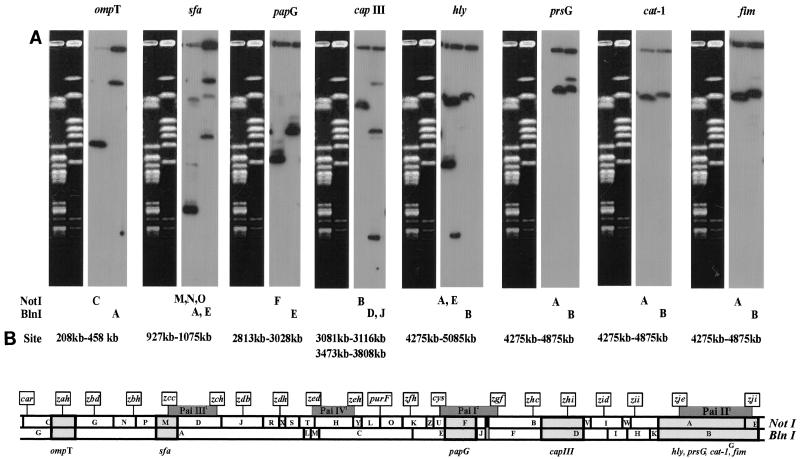

Southern blot analysis.

J96 virulence genes were identified through the hybridization of digoxigenin-labeled specific oligonucleotide probes for the ompT, sfa, papG, capIII, hly, prsG, cat-1, and fim genes by employing the conditions previously described (16).

RESULTS

Initial characterization of E. coli strain J96: genomic macrorestriction digestion patterns generated with NotI, BlnI, and I-CeuI.

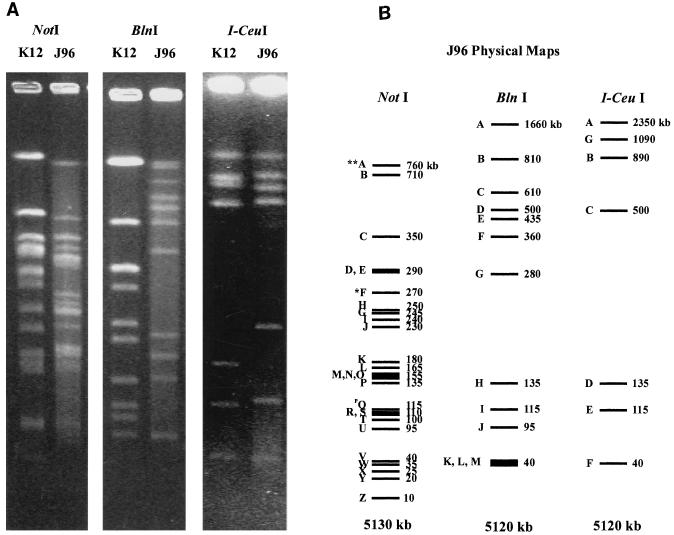

Macrorestriction digests of purified total genomic DNA from strain J96 with the enzymes NotI, BlnI, and I-CeuI yielded 26, 13, and 7 macrorestriction fragments, respectively (Fig. 1A). Previous work has shown that the highly conserved recognition sequence for the intron-encoded endonuclease I-CeuI is contained in the rrl 23S ribosomal genes. There are seven such ribosomal clusters in E. coli, yielding seven fragments. The less well conserved sites for the enzyme BlnI are often found within several of the rrs 16S ribosomal genes, yielding identically sized fragments between BlnI and I-CeuI digests whenever sites occur in the same pair of adjacent ribosomal clusters. This is the case for four of the seven I-CeuI fragments corresponding to the occurrence of sites for BlnI and I-CeuI in rrnA, -B, -C, -D, and -E. It is likely that the other three rrn clusters carry both BlnI and I-CeuI sites but that the BlnI fragments are interrupted by the occurrence of other BlnI sites. It should be noted that we chose a level of resolution that ignores the existence of very small fragments, too small to be easily resolved by PFGE (e.g., <5 kb), even though they most likely exist at least for the BlnI (also known as AvrII) digests (14). The size of the genome, as determined by the sum of all restriction fragments for each enzyme, illustrated in Fig. 1B, was measured as 5,130 kb for NotI, 5,120 kb for BlnI, and 5,120 kb for I-CeuI, for an average of 5,123 kb.

FIG. 1.

J96 NotI, BlnI, and I-CeuI native genomic DNA digestion patterns. (A) PFGE of wild-type K-12 strain MG1655 and of wild-type strain J96 genomic DNAs digested with NotI, BlnI, and I-CeuI. PFGE pulse times were ramped from 55 to 65 s over 7 h and from 20 to 30 s over 8 h. (B) Schematic representation of the restriction patterns in panel A. Alphabetical labeling of fragments follows the precedents set in K-12 mapping for NotI, BlnI, and I-CeuI digests. Individual fragment sizes are to the right in kilobases, with the totals beneath in kilobases. The J96 plasmid band, QN, is denoted with the superscript P and is found only in native genomic NotI digests. Fragments highlighted with the single asterisk, FN and EB, and the double asterisks, AN and BB, are those containing known loci for J96 pathogenicity islands, Pai-4 and Pai-5 (also called Pai-I and Pai-II, respectively) at 64 and 85 min, respectively.

Altered macrorestriction patterns of J96 insertion mutants.

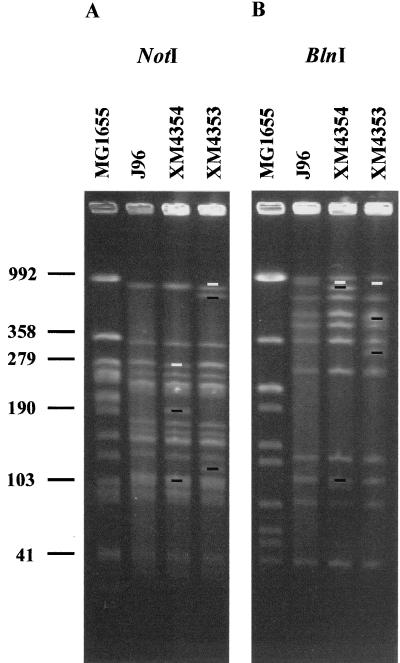

Several methods have been used to order the anonymous fragments from an enzyme digest (13, 39), each with some strategy that yields internally consistent two-dimensional or overlapping data. Herein, random mutagenesis of the J96 genome was carried out with the modified Tn10 elements Tn10dKanRCP2 and Tn10dSpcRCP2 (29), as has been previously described for strain K-12 (36). A typical macrorestriction analysis of two Tn10dRCP2 insertions within J96 strains χM4354 and χM4353 is shown in Fig. 2. Strain χM4354 contains the Tn10dKanRCP2 element. The insertion of the transposon disrupts the typical NotI band pattern obtained for wild-type J96 DNA (Fig. 2A, lane 2). The transposon inserted into NotI fragment E (EN) resulted in the introduction of a new NotI site and the appearance of the 100-kb and the 200-kb fragments (Fig. 2A, lane 3). Similarly, when the DNA from this same strain was digested with BlnI, band B (BB) was lost where the insertion occurred. The appearance of two new fragments of 700 and 110 kb (Fig. 2B, lane 3) was due to the corresponding introduction of the new BlnI site carried by the transposon. Macrorestriction analysis of χM4353 containing the Tn10dSpcRCP2 element shows that the introduction of this transposon occurred within band AN (loss of band A) and shows the appearance of two new bands of 635 and 125 kb (Fig. 2A, lane 4). The corresponding BlnI restriction digest of the same strain showed that the insertion occurred within band BB. There were a loss of band BB and the appearance of two new bands of 475 and 335 kb (Fig. 2B, lane 4). These data indicate that there is likely an end-to-end alignment between NotI bands AN and EN, as the Tn10dRCP2s both occur in BlnI band BB.

FIG. 2.

Localization of mini-Tn10 insertions in the J96 genome. (A) PFGE of genomic DNAs digested with NotI from K-12 strain MG1655, strain J96, and two independent J96::Tn10dRCP2 insertion mutants, χM4353 and χM4354. (B) PFGE of genomic DNAs digested with BlnI from the identical isolates. In both gels, composed of 1.2% (wt/vol) Bio-Rad PFGE agarose, the PFGE pulse times were ramped from 55 to 65 s for 7 h, 20 to 30 s for 8 h, and 7 to 15 s for 11 h in 0.5× TBE buffer. Native fragments missing from insertion mutants are marked by white bars, while novel subfragments from insertion mutants are marked by black bars. Numbers at left are sizes in kilobases.

J96 genomic map assembly: macrorestriction positions of the Tn10dRCP2 insertions.

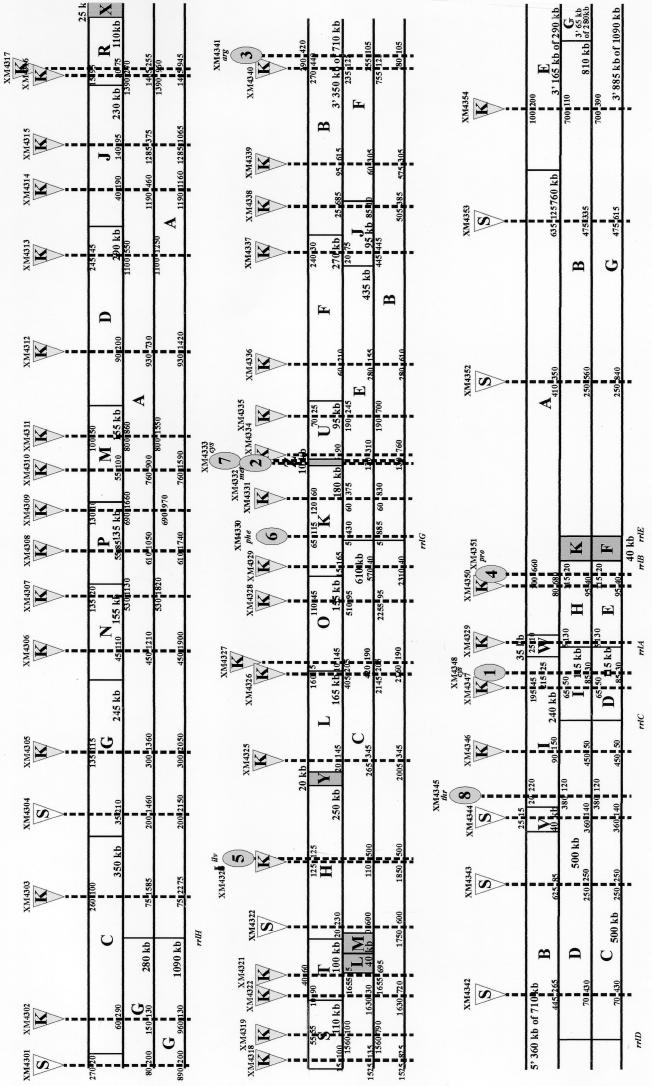

For the J96 genomic map assembly, shown in Fig. 3, end-to-end alignments were constructed from a selected subset of representative Tn10dRCP2 insertion-bearing J96 strains (Table 2). Initially, 362 presumptive J96 insertion mutants were isolated. Of these initial isolates, 182 were screened concurrently with NotI and BlnI, 102 were digested with NotI only, 4 were digested with BlnI only, 4 did not contain an insert, and 35 were not analyzed. The 102 Tn10dRCP2 insertion mutants were analyzed with NotI only as a quick screen for isolates without detected insertions and/or for clarifying band positions of only certain fragments. A total of 54 were selected for the ordering of the genomic J96 fragments based on the point of insertion of the Tn10dRCP2 generating overlaps between each of the NotI, BlnI, and I-CeuI fragments. This number of insertions was sufficient to align 24 of the 26 NotI fragments with their overlapping BlnI and I-CeuI fragments. Likewise, 10 of 13 BlnI fragments were aligned with the appropriate NotI and I-CeuI fragments and six of the seven I-CeuI fragments were aligned with NotI and BlnI fragments. From this subset, 39 of 46 NotI, BlnI, and I-CeuI band fragments positioned by end-to-end alignment resulted in two large contigs representing ∼60 and 40% of the J96 chromosome. The remaining seven fragments, bands XN, YN, and ZN; bands KB, LB, and MB; and I-CeuI band FC (Fig. 3, areas highlighted in gray), were not interrupted by an RCP2 insertion and were positioned by cross-digest hybridizations and/or double macrorestriction digestions.

FIG. 3.

J96 NotI–BlnI–I-CeuI map including the locations of 54 Tn10dRCP2 insertions used in the map's assembly. The linearized circular map is depicted in three segments connected English text-wise, with the circle opened at the upper left and lower right ends. Native NotI, BlnI, and I-CeuI sites and fragments are shown in the upper, middle, and lower tiers, respectively. The 54 Tn10dRCP2 insertions selected for map assembly are shown as filled wedges over dotted lines indicating the disruptions of native fragments in the three different macrorestriction backgrounds. Native macrorestriction fragments are labeled alphabetically as in Fig. 1. Sizes of the subfragments generated by insertion in different macrorestriction backgrounds are shown adjacent to the dotted lines on either side. The Tn10dRCP2 insertions are labeled above each wedge by the insertion mutant from which they were isolated. The Tn10dRCP2 insertions causing auxotrophies are depicted by ovals labeled 1 to 7 and phenotype. Putative locations of the seven rrl genes, each at a native I-CeuI site, are shown.

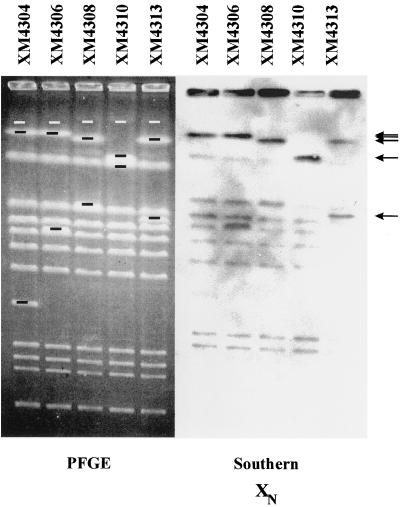

An example of Southern analysis used in positioning band XN is shown in Fig. 4. In an initial screen across the genome, the RCP2-bearing (J96::RCP2) derivative χM4312 was digested with BlnI. Strain χM4312 contains an RCP2 insertion within band AB (and thus a new BlnI site within the AB fragment) and two new subfragments of 930 and 730 kb. From Fig. 4, it can be shown that band XN hybridizes to the larger 730-kb subfragment from band AB, as designated by an arrow. Fine positioning of band XN within band AB (1,660 kb) was accomplished through further cross-hybridization analysis and is illustrated in Fig. 4. Cross hybridization is shown using a series of RCP2 insertions advancing clockwise through the AB fragment. These ordered insertions oriented band XN on the native AB fragment. Shown are insertional strains χM4304, χM4306, χM4308, χM4310, and χM4313. If band XN lies to the right of the insertions in band AB, then the subfragment to which it hybridizes gets gradually smaller. Conversely, if band XN lies to the left of the insertions, then the hybridizing subfragment gets larger. BlnI macrorestriction analysis of these strains is shown in the ethidium bromide-stained PFGE gel (left panel) along with hybridization of the band pattern to fragment XN (right panel). The RCP2 insertions in these strains yield band AB subfragments of 1,460 and 200 kb, 1,210 and 450 kb, 1,050 and 610 kb, 900 and 760 kb, and 1,100 and 550 kb, respectively. It is shown by cross hybridization to the clockwise (left to right)-advancing series of insertions that fragment XN hybridized to subfragments of gradually diminishing sizes. Thus, fragment XN lies to the right of the entire series. Similar analyses were performed in further placement of band XN and to place fragment YN within CB and fragment ZN within EB. Likewise, fragments KB and FC were positioned.

FIG. 4.

Location of band XN within subfragments of band AB generated by a series of mini-Tn10 insertions. PFGE and Southern hybridization to band XN of genomic DNAs from a series of J96::Tn10dRCP2 insertion mutants are shown. PFGE pulse times were ramped from 55 to 65 s for 7 h and from 20 to 30 s for 8 h in 0.5× TBE buffer. The gel was 1.2% (wt/vol) Bio-Rad PFGE-certified agarose. The mutants contained an ordered series of insertions advancing clockwise (left to right) within band AB. The missing band (AB) from each mutant is marked by white bars, while novel bands from each of them are marked by black bars. Arrows indicate the subfragments hybridizing most strongly to fragment XN.

Employing the above strategies, the physical map of the J96 chromosome from the NotI, BlnI, and I-CeuI macrorestriction digests of the selected subset Tn10dRCP2 insertion-bearing J96 strains resulted in two contigs representing a roughly 60/40 split of the chromosome. Closure of the chromosome at the WN-IN and HN-TN overhangs was accomplished by Southern hybridization of digoxigenin-labeled KB, LB, and MB DNAs to the AN, TN, and HN bands and by double macrorestriction digestions of excised fragments. The WN-IN overhangs indicated by macrorestriction analysis of RCP2 insertion-bearing strains suggested that these two NotI fragments were adjacent fragments. This was confirmed through Southern analysis, with fragment WN hybridizing to both bands HB and IB (data not shown). The HN-TN overhangs did not close, with bands HN and TN forming NotI overhangs of 25 and 60 kb, respectively, suggesting 85 kb of missing BlnI fragment(s). One possible explanation is that this 85-kb gap was indicative of three different restriction fragments forming the lowest-molecular-weight band in the BlnI digest. This is supported not only by the size of the NotI overhangs identified for bands TN and HN through insertion of the RCP2 element, but also by the much higher hybridization signal intensity of the lowest-molecular-weight BlnI band to band TN than to band HN. Finally, when the counterclockwise NotI subfragment of band TN generated in a NotI digest of insertion strain χM4329 was excised from a PFGE gel and subjected to a second enzymatic digestion with BlnI, it yielded three subfragments (data not shown). This indicated two BlnI sites within band TN in addition to the one within band HN. Given these overlapping relationships, the J96 macrorestriction map could be drawn in the linearized fashion shown in Fig. 3.

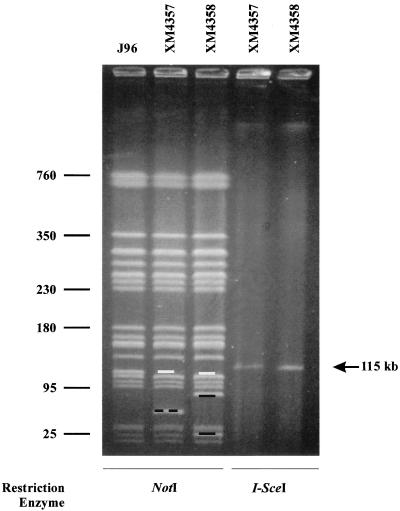

Confirmation of plasmid DNA in the macrorestriction digests of J96.

Fragment QN from strain J96 was confirmed to contain plasmid DNA by the closed-circular topology of its undigested precursor. From the above-mentioned collection of 362 isolates, seven different J96::Tn10dRCP2 mutants were found carrying insertions that disrupted band QN. These were at different loci on the fragment, as they resulted in different pairs of NotI subfragments by PFGE, all totaling 115 kb. Owing to the closed-circular topology of fragment QN's precursor, however, each insertion also resulted in single bands of identical sizes (115 kb) following digestion with BlnI, I-CeuI, or I-SceI (all of which, in addition to NotI, cleave within the RCP2 element [29]). NotI and I-SceI analyses from two of these insertion mutants, strains χM4357 and χM4358, are shown in Fig. 5. The absence of 115-kb plasmid bands in BlnI, I-CeuI, and I-SceI digests from wild-type J96 and its derivatives lacking plasmid insertions (results not shown) was consistent with the failure of large closed-circular DNAs to migrate into pulsed-field gels (3).

FIG. 5.

NotI and I-SceI digestions of different insertions in the 115-kb J96 plasmid. The figure shows PFGE with pulse times ramped from 55 to 65 s for 7 h, 20 to 30 s for 8 h, and 7 to 15 s for 11 h in 0.5× TBE buffer with the gel composed of 1.2% (wt/vol) Bio-Rad PFGE agarose, performed with genomic DNAs from wild-type J96 and J96 insertion mutants. Native bands missing from insertion mutants are marked by white bars, while novel bands from insertion mutants are marked by black bars. Numbers at left are sizes in kilobases.

Mapping of auxotrophies, rrl genes, and virulence factors.

An advantage of physical mapping with rare-restriction site insertions, compared to Southern hybridizations or second-enzyme redigestions of excised bands, is that the restriction landmarks needed for physical mapping can be generated in insertion mutants that are also useful in genetic mapping. Thus, the use of Tn10dRCP2 insertions can be employed to develop functional (i.e., biochemical-genetic) correlations with the J96 physical map. Eight different insertions that contributed to physical mapping were found to also cause J96 auxotrophies that, by a combination of auxanography and map location, could be inferred to interrupt homologs of genes previously described for strain K-12 (36). Thus, these insertions allowed integration of the newly constructed (and largely featureless) J96 physical map with the extensively characterized E. coli genetic map.

Additional functional correlations with the J96 physical map were identified through the conservation of native I-CeuI sites within 23S ribosomal (rrl) genes (28) and by Southern analyses to localize known virulence genes. The seven rrl genes, conserved throughout E. coli and, indeed, throughout the family Enterobacteriaceae, were located at the cleavage sites from I-CeuI digestion; the positions of these seven sites were consistent with overall conservation of E. coli chromosomal organization (28).

Eight acknowledged virulence genes (encoding outer membrane protease T [ompT], F1C fimbriae [foc], PapG and PrsG pili, group III capsule, alpha-hemolysin [hly], chloramphenicol acetyltransferase [cat-1], and type 1 pili [fim]), were localized to sequences between native rare restriction sites by Southern analyses to overlapping NotI and BlnI fragments (Fig. 6). Six of these eight virulence genes were found, as expected, at sequences corresponding to the locations of either of the two well-studied J96 pathogenicity islands, Pai-I and Pai-II (10, 11, 20). Of note, the group II capsule (kpsMT) genes hybridized to the two nonadjacent NotI fragments BN and UN. This is explained, at least in part, by an insertion of Pai-I between fragments BN and UN and was consistent with the lack of group II capsule expression characterizing strain J96. The foc genes, encoding F1C pili, were localized (hybridization with sfa) to 25 min (34, 40). This is the same region containing the closely related sfa genes in newborn sepsis-associated E. coli strain K1 (37).

FIG. 6.

Positioning of virulence genes by Southern analysis. (A) Southern hybridizations of eight different virulence gene clones to wild-type J96 genomic DNAs. The corresponding pulsed-field gel (composed of 1.2% [wt/vol] Bio-Rad PFGE agarose and with pulse times ramped from 55 to 65 s for 7 h, 20 to 30 s for 8 h, and 7 to 15 s for 11 h in 0.5× TBE buffer) from which the genomic DNAs (digested with either NotI or BlnI) were transferred is shown to the left of each filter hybridization. Above each filter, the particular clone used in hybridization is labeled by virulence gene(s). Below each filter are given the alphabetical designations of the particular NotI and BlnI bands to which the probe hybridized. (B) Genomic map localizations of the eight virulence gene clusters. For each clone, hybridization zones are labeled by virulence gene(s). Regions of hybridization overlap between the NotI and BlnI maps are shaded. The extent of overlap by the native restriction site positions in Fig. 3 is given, for each clone, in kilobases above the map. Also given are the positions (10, 20) of known pathogenicity islands (shaded boxes above the map) and the map positions (36) of a series of 20 Tn10dRCP2 insertions (by flags inserted above the map) used previously to integrate the J96 and K-12 genomic copies (37).

DISCUSSION

Rare cutting restriction endonucleases and PFGE are very powerful tools for the study of bacterial genomes. Whole genomes have been analyzed in the manner traditionally available only for plasmid-sized DNAs, allowing strains to be characterized (i) by physical mapping for the analysis of genomic organization and gene locus relationships (4, 6, 8, 31, 37), (ii) through genomic macrorestriction fingerprinting for population analysis and epidemiologic studies (36), (iii) through intra- and interspecies comparative genomics (9, 37), and (iv) by nucleotide sequence after fragmentation of the genome into contiguous and/or nonoverlapping segments (5, 7, 30). Ultimately, a macrorestriction map from a given strain integrated with the species' genetic map may provide a critical step in studying that strain's uniqueness. While sequencing efforts are rapidly increasing the details available for various prototypic genomes, the costs are generally too great to resequence even the major variants in a given species. Indeed, comparative macrorestriction mapping guided by the genetic map shared by different copies may provide a significant cost savings by identifying the copy-specific DNAs to be sequenced while avoiding coinherited sequences. Thus, characterization of the various different copies of a bacterial genome through assembly of their physical maps provides a useful first step toward comprehensive description of the species' genome.

Recently, we have identified two additional accessory chromosomal segments and two deletions within the uropathogenic E. coli strain J96 relative to the nonpathogenic strain K-12 (37). In order to identify and verify the sizes and locations of these elements (and those of Pai-I and Pai-II), we constructed a genomic map from J96. We demonstrate that the general method for de novo mutations inserting mini-Tn10 transposable elements (36) provides a rapid means for physical and genetic mapping of the J96 genome.

The J96 physical map was determined from (i) the ordering of insertions made possible by their localization in overlapping domains of NotI, BlnI, and/or I-CeuI fragments and (ii) the orienting of subfragments generated by cleavages at insertion sites made possible by the inevitability that a given pair of J96::Tn10dRCP2 insertions must lie precisely the same distance apart regardless of whether by NotI, BlnI, or I-CeuI mapping. Digestions of E. coli J96 genomic DNA with either NotI, BlnI, or I-CeuI yielded 27, 11, and 7 genomic fragments, respectively. From the macrorestriction analyses, the total size for the J96 genome was 5,120 kb; this is compared with 4,640 kb for the genome of laboratory strain K-12 (37). Digestion with I-SceI yielded no fragments, consistent with the expected lack of native I-SceI sites (41, 44). These native macrorestriction patterns from strain J96, although allowing fingerprinting and preliminary sizing of the genome, failed to provide conclusive evidence of doublet, triplet, or plasmid bands, or any evidence of the end-to-end alignments of chromosomal fragments. Thus, further characterization was carried out by mutagenesis with Tn10dRCP2 minitransposons.

The mini-Tn10-based transposons Tn10dKanRCP2 and Tn10dSpcRCP2 were used to characterize the J96 genome in a number of ways. First, Tn10dRCP2 insertions were used to determine the end-to-end alignments of native chromosomal NotI, BlnI, and I-CeuI fragments. Although typical procedures of aligning genomic macrorestriction fragments have employed (i) Southern analyses probing with either linking clones or genetically mapped clones or (ii) double digestions (at exclusively native sites) of excised bands, end-to-end alignments and map assembly were performed in this instance by the integration of macrorestriction patterns inherent with insertions carrying the RCP2 element. Employing this strategy, a single large contig of overlapping chromosomal NotI, BlnI, and I-CeuI fragments that had interdigitating NotI–BlnI–I-CeuI ends at NotI fragments I and W (fragments IN and WN) was assembled. Circularization at these ends was confirmed by Southern hybridization of BlnI fragment I (fragment IB) with fragments IN and WN. In addition, fragments XN and YN; fragments KB, LB, and MB; and fragment FC, all <40 kb and in total representing <3% of the J96 chromosome, were uninterrupted by insertions and consequently were positioned by Southern hybridizations.

Second, Tn10dRCP2 insertions were used to detect doublet and triplet bands in the NotI, BlnI, and I-CeuI restriction patterns from the wild-type strain. These were detected by separate interruption of each fragment contributing to the native NotI, BlnI, and I-CeuI restriction patterns. Where possible, demonstration of doublet and triplet bands was made by introduction of multiple insertions conferring resistance to different antibiotics in the same strain. The advantage of distinguishing multiplet bands in this way, in physical mapping with rare-restriction site insertions, is unavailable by traditional methods. In addition, the restriction landmarks used in physical mapping are insertion mutations that can also be useful in genetic mapping.

Third, Tn10dRCP2 insertions were used to demonstrate the closed-circular topology of a J96 plasmid band. I-SceI digestion of genomic DNA from J96 mutants carrying independent Tn10dRCP2 insertions generated identical bands of the same size as the 13th largest native NotI band, QN, of 115 kb. The insertions' locations at different sites in fragment QN were confirmed by the different subfragment pairs generated from these mutants. Thus, the 115-kb band QN from wild-type J96 contained plasmid DNA that was linearized by a native NotI site.

A fourth use of Tn10dRCP2 insertions was to develop functional (biochemical-genetic) correlations with the J96 physical map. Eight different insertions that contributed to physical mapping were found to also cause J96 auxotrophies that, by a combination of auxanography and map location, could be inferred to interrupt homologs of genes previously described for strain K-12. Thus, these insertions allowed integration of the newly constructed (and largely featureless) J96 physical map with the extensively characterized E. coli genetic map (9).

Additionally, two functional correlations of the J96 physical map with the E. coli genetic map were the conservation of native I-CeuI sites within rrl sequences (28) and that by Southern hybridization to known J96 virulence genes. These seven rrl genes conserved throughout the E. coli species and, indeed, throughout the family Enterobacteriaceae were located at the I-CeuI cleavage sites. The positions of these seven sites were consistent with overall conservation of E. coli chromosomal organization of the rrl loci (28).

Eight acknowledged virulence genes were localized to sequences between native rare restriction sites by hybridizations to overlapping NotI and BlnI fragments. Six of these eight virulence genes were found, as expected, at sequences corresponding to the locations of either of the two J96 pathogenicity islands Pai-4 (also called Pai-I) and Pai-5 (also called Pai-II). These pathogenic polymorphisms have been detected by the crossing of Tn10dRCP2 alleles between strains K-12 and J96 to allow alignment of their chromosomes' physical maps into heteroduplex-like structures (9). Also, the foc genes, encoding F1C pili, were mapped to 25 min (35, 40), the same region containing the related sfa genes in newborn sepsis-associated E. coli (37).

Thus, integrated physical-genetic maps of genomes afford important advantages that remain beyond our reach by either physical or genetic mapping alone. Nevertheless, owing largely to the techniques that have been available, physical maps and genetic maps have been traditionally viewed independently of one another, with integration taking place only at stages subsequent to complete assembly. Although the current trend is for physical mapping to proceed from the long range (macrorestriction maps), to the mid-range (ordered overlapping clones) to the detailed (primary nucleotide sequence) entirely apart from any systematic genetic integration, the transposon-based mapping demonstrated herein affords such integration, which is useful for intraspecies comparisons in E. coli and other bacteria. Since the E. coli genetic map is conserved species-wide (22), Tn10dRCP2 insertions crossed between different uropathogenic isolates can be employed to generate macrorestriction map correspondences and, consequently, in pairs, allow determination of regions of macrorestriction fragment length isomorphism and polymorphism (37). Thus, the 54 Tn10dRCP2 insertion-bearing J96 mutants described herein each generate (regardless of the interrupted gene) both an RCP2 resistance allele and an RCP2 restriction landmark. These can be used not only in physical mapping to accurately position other insertions but also in “genetic clamping” (genetic inference of physical-map correspondences between strains or lineages) (37). These specific Tn10dRCP2 insertional variants provide a means for identifying other pathogen-specific DNAs and for carrying out comparative genomic analysis (37). Thus, they provide a platform for a further comparison within the subgroup of uropathogens that might reveal strain-specific DNAs that contribute to the diversity of epidemiologic associations (17, 25, 45). Future analyses may reveal genetic polymorphisms accounting for uropathogenic strain-specific traits, including pathogenicity or the molecular evolution of new virulent strains and potential therapeutic targets.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bachmann B J. Derivations and genotypes of some mutant derivatives of Escherichia coli K-12. In: Neidhardt F C, Ingraham J L, Low K B, Magasanik B, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1987. pp. 1190–1219. [Google Scholar]

- 1a.Bergthorsson U, Ochman H. Distribution of chromosome length variation in natural isolates of Escherichia coli. Mol Biol Evol. 1998;15:6–16. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergthorsson U, Ochman H. Heterogeneity of genome sizes among natural isolates of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5784–5789. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.5784-5789.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birren B, Lai E. Pulsed field gel electrophoresis: a practical guide. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackwood R A, Rode C K, Pierson C L, Bloch C A. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis genomic fingerprinting of hospital Escherichia coli bacteraemia isolates. J Med Microbiol. 1997;46:506–510. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-6-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blattner F, Plunkett III G, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Riley M, Burland V, Collado-Vides J, Glassner J D, Rode C K, Mayhew G, Gregor J, Davis N W, Kirkpatrick H, Goeden M, Rose D, Mau R, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli. Science. 1997;277:1453–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloch C, Rode C. Pathogenicity island evaluation in Escherichia coli K1 by crossing with strain K-12. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3218–3223. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3218-3223.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloch C, Rode C, Obreque V, Mahillon J. Purification of Escherichia coli chromosomal segments without cloning. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;223:104–111. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bloch C A, Huang S-H, Rode C K, Kim K S. Mapping of noninvasion TnphoA mutations on the Escherichia coli O18:K1:H7 chromosome. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;144:171–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bloch C A, Rode C K, Obreque V H, Russell K Y. Comparative genome mapping with mobile physical map landmarks. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7121–7125. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.7121-7125.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blum G, Falbo V, Caprioli A, Hacker J. Gene clusters encoding the cytotoxic necrotizing factor type 1, Prs-fimbriae and α-hemolysin form the pathogenicity island II of the uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain J96. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;126:189–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blum G, Ott M, Lischewski A, Ritter A, Imrich H, Tschape H, Hacker J. Excision of large DNA regions termed pathogenicity islands from tRNA-specific loci in the chromosome of an Escherichia coli wild-type pathogen. Infect Immun. 1994;62:606–614. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.606-614.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canard B, Saint-Joanis B, Cole S T. Genomic diversity and organization of virulence genes in the pathogenic anaerobe Clostridium perfringens. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1421–1429. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole S T, Saint Girons I. Bacterial genomics. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1994;14:139–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniels D. The complete AvrII restriction map of the Escherichia coli genome and comparisons of several laboratory strains. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:2649–2651. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.9.2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foxman B. Recurring urinary tract infection: incidence and risk factors. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:331–333. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.3.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foxman B, Zhang L, Palin K, Tallman P, Marrs C. Bacterial virulence characteristics of Escherichia coli isolates from first-time urinary tract infection. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1514–1521. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.6.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foxman B, Zhang L, Tallman P, Palin K, Rode C, Bloch C, Gillespie B, Marrs C. Virulence characteristics of Escherichia coli causing first urinary tract infection predict risk of second infection. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1536–1541. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.6.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foxman B, Zhang L, Tallman P, Andree B C, Geiger A M, Koopman J S, Gillespie B W, Palin K A, Sobel J D, Rode C K, Bloch C A, Marrs C F. Transmission of uropathogens between sex partners. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:989–992. doi: 10.1086/514007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hacker J. Genetic determinants coding for fimbriae and adhesins of extraintestinal Escherichia coli. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1990;151:1–27. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74703-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hacker J, Bender L, Ott M, Wingender J, Lund B, Marre R, Goebel W. Deletions of chromosomal regions coding for fimbriae and hemolysins occur in vitro and in vivo in various extraintestinal Escherichia coli isolates. Microb Pathog. 1990;8:213–225. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(90)90048-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heath J D, Perkins J D, Sharma B, Weinstock G M. NotI genomic cleavage map of Escherichia coli K-12 strain MG1655. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:558–567. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.558-567.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill C W, Harnish B W. Inversions between ribosomal RNA genes of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:7069–7072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.7069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hull R A, Gill R E, Hsu P, Minshew B H, Falkow S. Construction and expression of recombinant plasmids encoding type 1 or d-mannose-resistant pili from a urinary tract infection Escherichia coli isolate. Infect Immun. 1981;33:933–938. doi: 10.1128/iai.33.3.933-938.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson J, Brown J. A novel multiply primed polymerase chain reaction assay for identification of variant papG genes encoding the Gal(alpha 1-4)Gal-binding PapG adhesins of Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:920–926. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.4.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson J, Russo T, Scheutz F, Brown J, Zhang L, Palin K, Rode C, Bloch C, Marrs C, Foxman B. Discovery of disseminated J96-like strains of uropathogenic Escherichia coli O4:H5 containing genes for both PapG(J96) (class I) and PrsG(J96) (class III) Gal(alpha1-4)Gal-binding adhesins. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:983–988. doi: 10.1086/514006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson J R, Stapleton A E, Russo T A, Scheutz F, Brown J J, Maslow J N. Characteristics and prevalence within serogroup O4 of a J96-like clonal group of uropathogenic Escherichia coli O4:H5 containing the class I and class III alleles of papG. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2153–2159. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2153-2159.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kunin C. Detection, prevention and management of urinary tract infections. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lea & Febiger; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu S-L, Hessel A, Sanderson K E. Genomic mapping with I-CeuI, an intron-encoded endonuclease specific for genes for ribosomal RNA, in Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli, and other bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6874–6878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahillon J, Rode C, Leonard C, Bloch C. Ultrarare restriction site-carrying transposons for bacterial genomics. Gene. 1997;187:273–279. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00766-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahillon J, Kirkpatrick H A, Kijenski H L, Bloch C A, Rode C K, Mayhew G F, Rose D J, Plunkett G, 3rd, Burland V, Blattner F R. Subdivision of the Escherichia coli K-12 genome for sequencing: manipulation and DNA sequence of transposable elements introducing unique restriction sites. Gene. 1998;223:47–54. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00365-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maurelli A T, Fernandez R E, Bloch C A, Rode C K, Fasano A. “Black holes” and bacterial pathogenicity: a large genomic deletion that enhances the virulence of Shigella spp. and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3943–3948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morschhäuser J, Vetter V, Emödy L, Hacker J. Adhesin regulatory genes within large, unstable DNA regions of pathogenic Escherichia coli: cross-talk between different adhesin gene clusters. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:555–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ott M, Hacker J. Analysis of the variability of S-fimbriae expression in an Escherichia coli pathogen. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;63:233–238. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(91)90091-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ott M, Bender L, Blum G, Schmittroth M, Achtman M, Tschape H, Hacker J. Virulence patterns and long-range genetic mapping of extraintestinal Escherichia coli K1, K5, and K100 isolates: use of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2664–2672. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2664-2672.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rode C K, Obreque V H, Bloch C A. New tools for integrated genetic and physical analyses of the Escherichia coli chromosome. Gene. 1995;166:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00630-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rode C K, Melkerson-Watson L J, Johnson A T, Bloch C A. Type-specific contributions to chromosome size differences in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1999;67:230–236. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.230-236.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Romling U, Grothues D, Heuer T, Tummler B. Physical genome analysis of bacteria. Electrophoresis. 1992;13:626–631. doi: 10.1002/elps.11501301128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Romling U, Tummler B. Bacterial genome mapping. J Biotechnol. 1994;35:155–164. doi: 10.1016/0168-1656(94)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmoll T, Morschhauser J, Ott M, Ludwig B, van Die I, Hacker J. Complete genetic organization and functional aspects of the Escherichia coli S fimbrial adhesion determinant: nucleotide sequence of the genes sfa B, C, D, E, F. Microb Pathog. 1990;9:331–343. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(90)90067-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shibata T, Watabe H, Kaneko T, Iino T, Ando T. On the nucleotide sequence recognized by a eukaryotic site-specific endonuclease, Endo.SceI from yeast. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:10499–10506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sternberg N L, Maurer R. Bacteriophage-mediated generalized transduction in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:18–43. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swenson D, Bukanov N, Berg D, Welch R. Two pathogenicity islands in uropathogenic Escherichia coli J96: cosmid cloning and sample sequencing. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3736–3743. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3736-3743.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watabe H, Iino T, Kaneko T, Shibata T, Ando T. A new class of site-specific endodeoxyribonucleases. Endo.Sce I isolated from a eukaryote, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:4663–4665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang L, Foxman B, Tallman P, Cladera E, Le Bouguenec C, Marrs C. Distribution of drb genes coding for Dr binding adhesins among uropathogenic and fecal Escherichia coli isolates and identification of new subtypes. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2011–2018. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2011-2018.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]