Abstract

Background

Older age is associated with poorer outcomes to COVID-19 infection. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health established a longitudinal cohort of adults aged 65–80 years to study the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Here we describe the characteristics of the cohort in general, and specifically the immune responses at baseline and after primary and booster vaccination in a subset of longitudinal blood samples, and the epidemiological factors affecting these responses.

Methods

4551 participants were recruited, with humoral (n=299) and cellular (n=90) responses measured before vaccination and after two and three vaccine doses. Information on general health, infections, and vaccinations were obtained from questionnaires and national health registries.

Findings

Half of the participants had a chronic condition. 849 (18·7%) of 4551 were prefrail and 184 (4%) of 4551 were frail. 483 (10·6%) of 4551 had general activity limitations (scored with the Global Activity Limitation Index). After dose two, 295 (98·7%) of 299 participants were seropositive for anti-receptor binding domain IgG, and 210 (100%) of 210 participants after dose three. Spike-specific CD4 and CD8 T cell responses showed high heterogeneity after vaccination and responded to the alpha (B.1.1.7), delta (B.1.617.2), and omicron (B.1.1.529 or BA.1) variants of concern. Cellular responses to seasonal coronaviruses increased after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Heterologous prime boosting with mRNA vaccines was associated with the highest antibody (p=0·019) and CD4 T cell responses (p=0·003), and hypertension with lower antibody levels after three doses (p=0·04).

Interpretation

Most older adults, including those with comorbidities, generated good serological and cellular responses after two vaccine doses. Responses further improved after three doses, particularly after heterologous boosting. Vaccination also generated cross-reactive T cells against variants of concern and seasonal coronaviruses. Frailty was not associated with impaired immune responses, but hypertension might indicate reduced responsiveness to vaccines even after three doses. Individual differences identified through longitudinal sampling enables better prediction of the variability of vaccine responses, which can help guide future policy on the need for subsequent doses and their timing.

Funding

Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Norwegian Ministry of Health, Research Council of Norway, and Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations.

Introduction

Adults aged 65 years and older present with increased incidence of infections, increased prevalence of chronic and autoimmune diseases, and increased mortality.1 Older adults are also at a high risk of severe COVID-19 and death.2 Adults over 65 years have consequently been prioritised in mass COVID-19 vaccination campaigns. However, seroconversion rates and antibody levels after two vaccine doses can decrease with age and be lower in individuals who are immunosuppressed, obese, diabetic, or have other comorbidities.3, 4

Neutralising antibodies block viral entry and are considered a correlate of protection against infection.5 However, antibody titres wane over time6 and poorer neutralisation by vaccine-mediated antibodies has been observed against emerging strains, including SARS-CoV-2 delta (B.1.617.2)7 and omicron (B.1.1.529 or BA.1) variants of concern (VOC).8, 9 T cell responses, in addition to long-lived B cells, are important for protection against severe disease, immune longevity, and recognising new viral variants.10, 11, 12, 13 In addition, T cells specific for seasonal coronaviruses cross-react with SARS-CoV-2 epitopes, possibly contributing to protective responses.13

As many countries are facing ageing populations, longitudinal studies on the effects of ageing have been established to improve the health-care needs in older adults14 and assess the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic.4, 15, 16 However, few countries, if any, combine epidemiological data on comorbidities, frailty, function, and lifestyle factors with sequential in-depth immunological data to explore the effects of infection and vaccination.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Our search of PubMed for studies published between Jan 1 and Dec 1, 2020, using the terms “COVID-19”, “vaccination”, and “older adults”, revealed a low number of clinical trials on the effect and immunogenicity of the novel COVID-19 vaccines in older adults and no observational studies. Although several studies have since assessed vaccine effectiveness and immunogenicity in older adults, a PubMed search on Dec 15, 2022, with the search terms “longitudinal”, “cohort”, “older adults”, “COVID-19”, and “vaccination” gave results predominantly focusing on studies of vaccine responses in frail older adults living in long-term health-care facilities or specific clinical risk groups including patients with cancer or on dialysis. In addition, these studies have focused predominantly on serological responses and do not have wider epidemiological data from individuals in the general population or data on SARS-CoV-2 specific cellular responses.

Added value of this study

This study describes a prospective longitudinal cohort of over 4500 adults (the senior cohort) that has been established to monitor the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in older adults aged 65–80 years from the general population. Here we combine humoral and functional cellular responses from before and after three vaccine doses with extensive epidemiological data on infection and vaccination history, physical and mental health, comorbidities, and demographic factors, collected from national health registries and self-reported questionnaires. By analysing antibody titres and spike-specific CD4 and CD8 T cell responses generated by vaccination, we have characterised the immune response in greater depth and explored associations between immune responses and comorbidities, frailty, and limitations in daily activities. Through close monitoring of participants during the pandemic, we were able to exclude the confounding effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on vaccine responses and, therefore, have shown the effect of booster vaccination on immunity and the enhanced vaccine responses induced through heterologous prime-boosting with mRNA vaccines. Our results also show a significant association between hypertension and poorer antibody responses to vaccination, supporting other studies that have observed this effect. The ability to acquire longitudinal samples from individuals both in this study and for future work allows us to fully characterise the heterogeneity seen in the general population of older adults after vaccination and infection and provides statistical power to our findings.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our findings show that humoral and cellular immune responses are generated via vaccination in otherwise COVID-19-naive older adults and are especially enhanced by heterologous booster vaccinations. Hypertension might be a useful predictor of reduced antibody responses and should be further investigated. Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 vaccination boosted cellular responses to other seasonal human coronaviruses, suggesting possible cross-protection.

To guide future vaccine policy on the need for subsequent doses and their timing, further age-specific data are needed. To this end, we established a prospective, population-based longitudinal cohort of almost 5000 adults aged 65–80 years to study the short-term and long-term consequences of COVID-19 infection and vaccination. In a subset of participants, we characterised longitudinal cellular and humoral immune responses before and after vaccination and the ageing-associated determinants affecting these responses.

Methods

Study design and participants

The senior cohort is an ongoing, longitudinal cohort established by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Adults aged 65–80 years living in Oslo, Norway, were randomly selected from the Norwegian Population Register in two rounds (n=13 638; appendix p 3), using the SAS (version 9.4) software and the proc surveyselect command. All participants (n=1373) who gave consent in the first round (December, 2020) were immediately invited to donate blood samples. 412 blood samples were obtained from 488 participants who consented to donate blood. Questionnaires are regularly sent to all participants from both rounds (n=4852) to obtain information about general health, COVID-19 vaccination, adverse events, respiratory symptoms, and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Ethical approval was given by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics Southeast (229359). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Blood samples for peripheral blood mononuclear cells, serum, plasma, and DNA were obtained in three rounds corresponding to prevaccination (Dec 8, 2020, to May 4, 2021), after second-dose vaccination (June 13 to Oct 27, 2021), and after third-dose vaccination (Jan 31 to April 28, 2022). Longitudinal samples were obtained from the same participants.

Participant data and national registry data were linked with the Norwegian unique personal identification number to establish birth year and sex via the National Population Register; COVID-19 vaccine type, vaccination dates, and number of doses were linked via SYSVAK, the Norwegian Immunisation Registry; and dates of PCR-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infections were established via MSIS, the Norwegian Surveillance System for Communicable Diseases. Until January 2022, PCR testing and reporting to MSIS was mandatory. Subsequently, self-testing with rapid antigen kits was recommended for adults who had received three doses. Self-reported infections and test dates were collected from questionnaires. To check accuracy, self-reported vaccination and infection status were cross-checked with SYSVAK and MSIS, respectively (appendix p 22). Breakthrough infections after dose three were followed until June 26, 2022, at the close of the eighth questionnaire, just before the national recommendation of a fourth dose for this age group.

The following variables were obtained through questionnaires: influenza vaccination, education, living and work situation, smoking, alcohol use, height, weight, exercise, bone fractures, medication, hypertension, and chronic conditions, such as asthma, chronic lung disease, diabetes, myocardial infarction, heart condition, cardiovascular disease, stroke, chronic liver disease, chronic kidney disease, neurological disease, and cancer (present or previous). Participants who selected organ transplant, immunodeficiency, or using immunosuppressive medication were collectively categorised as immunosuppressed.

Frailty was measured with the Anamnestic Frailty Phenotype, on the basis of self-reported involuntary weight loss, exhaustion, and low activity (without performance measures).17 Each item was given a score of 0 or 1. Total scores were categorised as not frail=0, prefrail=1, and frail=2–3 (appendix pp 10–12). Limitations in daily activities (as a measure of disability) were self-reported using the Global Activity Limitation Index,18 adapted by Statistics Norway, and included four concepts: (1) “having restrictions in activities”; (2) “in activities people usually do”; (3) “because of a health problem”; and (4) “for at least the past 6 months”. Response categories were aggregated into limited (1) and not limited (0). Frequency of physical exercise (minimum 10 min per day) was self-reported using five response categories from “never” to “daily”, and answers aggregated to two categories of twice or more per week or less than twice per week.

The total cohort sample presented here consists of 4551 participants (appendix p 3). A subset of participants who had provided a prevaccination blood sample (round 1) and a postvaccination blood sample (round 2) at least 14 days after the second dose by June 26, 2021, were selected for cellular analyses (n=90), with further additional participants sampled for antibody analysis (giving a total of n=299). Linkage to SYSVAK confirmed that 69 of 90 round 1 samples were prevaccination samples. The remaining 21 of 90 vaccinated individuals were excluded from the prevaccination analysis. A subsequent longitudinal sample (round 3) was obtained (n=80). After exclusion of cases with two doses only (n=1), four doses (n=2), or previous SARS-CoV-2 infection (n=6), the subset for cellular analysis after the third dose was n=71. Additional samples after dose three were selected for antibody analysis, excluding participants with previous SARS-CoV-2 infections, giving a total of 210 samples.

Serum IgG anti-receptor binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein was measured in BAU/mL, as described by Tran and colleagues.19 Thawed cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells were stimulated for 24 h at 37°C in complete medium (RPMI 1640 Medium, 10% fetal bovine serum, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1% MEM non-essential amino acids, 12 μg/mL gensumycin (all ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and 50 nM 1-thioglycerol (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) with SARS-CoV-2 spike peptides (Wuhan-Hu-1 strain, and alpha [B.1.1.7], delta, and omicron VOCs), spike and nucleocapsid pools of seasonal human coronaviruses (HCoV-OC43, HCoV-NL63, and HCoV-HKU-1), and cytomegalovirus pp65 peptides (appendix p 13). Brefeldin A (BD Golgi Plug, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) was added after 2 h. Activated CD4 T cells were identified by CD40L and TNF-α coexpression and CD8 T cells by IFN-γ or TNF-α expression (appendix p 4). Cells were stained with surface markers (CD4, CD8, CD3, LIVE/DEAD viability dye; see appendix p 13 for manufacturer details) for 30 min at 4°C, fixed with BD Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), and stained intracellularly (CD40L, IFN-γ, TNFα, and CD69) for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were resuspended in FACS buffer before acquisition with a ZE5 Cell Analyser (Bio-Rad, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of T cell responses were done with Wilcoxon rank sum or Kruskal-Wallis tests; p values were adjusted for multiple testing with the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Pearson correlations were used to describe the degree of covariation. Analyses of immunological data were done with GraphPad Prism version 9. Statistical significance is shown as exact p values.

For analysis of associations between demographic factors or health conditions and immune responses (continuous outcomes), median regression was used due to skewed distribution of the outcomes (appendix p 5).20 For analysis of factors influencing IgG anti-receptor binding domain antibody levels (BAU/mL, continuous outcome), median regression adjusted for age (in years), sex, time since vaccination (in days), and vaccine type or combination were used. Associations between SARS-CoV-2 spike-specific CD4 and CD8 T cell responses (normalised values in percent, continuous outcome) and factors were estimated using the same model, except for analysis of the sample after two doses (n=90), in which time since vaccination was excluded due to high colinearity with age (Pearson's r=0·75, p<0·001). All regression analyses were done in STATA/SE 15.0. p<0·05 was considered statistically significant.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

In total, 4852 (35·6%) of 13 638 adults aged 65–80 years consented to participate in the senior cohort study. 4551 (93·8%) of 4852 participants responded to the first questionnaire (hereafter referred to as the total study sample). 265 (54·3%) of the 488 participants who consented to blood sampling donated three sequential blood samples corresponding to pre-vaccination (round 1), after dose two vaccination (round 2), and after dose three vaccination (round 3; appendix p 3).

Overall, the characteristics of the antibody (n=299) and cellular analysis (n=90) subsets were representative of the total study (table 1 , appendix pp 10–12). The median age was 71 years (IQR 68–75) and 2385 (52·4%) of 4551 participants were women. Data on race and ethnicity are not routinely collected in Norway. 4407 (96·8%) of 4551 participants were vaccinated with at least two doses against COVID-19, the majority with BNT162b2 (Pfizer–BioNTech; 3147 [71·4%] of 4407) or mRNA-1273 (Moderna; 1259 [28·6%] of 4407), and mainly received homologous primary vaccination. There were few cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection by the end of June, 2021 (79 [1·7%] of 4551). According to self-reported data (when PCR testing was no longer mandatory), the number of infections increased considerably by the end of March, 2022 (1227 [27·0%] of 4551).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the senior cohort participants

| Participants (n=4551)* | Antibody subset (n=299)* | Cellular subset (n=90)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of birth | 1950 (1946–1953) | 1950 (1946–1953) | 1950 (1947–1953) | ||

| Age, years | 71 (68–75) | 71 (68–75) | 71 (68–74) | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Men | 2166 (47·6%) | 147 (49·2%) | 46 (51·1%) | ||

| Women | 2385 (52·4%) | 152 (50·8%) | 44 (48·9%) | ||

| Infection or vaccination status by second sampling† | |||||

| Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 by PCR | 79 (1·7%) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Dose one of vaccination against COVID-19 | 4504 (99·0%) | 299 (100%)‡ | 90 (100%)‡ | ||

| ChAdOx1-S, Vaxzevria, AstraZeneca | 5/4504 (0·1%) | 0 | 0 | ||

| BNT162b2, Comirnaty, Pfizer–BioNTech | 3208/4504 (71·2%) | 212 (70·9%) | 59 (65·6%) | ||

| mRNA-1273, Spikevax, Moderna | 1291/4504 (28·7%) | 87 (29·1%) | 31 (34·4%) | ||

| Dose two of vaccination against COVID-19 | 4407 (96·8%) | 299 (100%)‡ | 90 (100%)‡ | ||

| ChAdOx1-S, Vaxzevria, AstraZeneca | 1/4407 (0·0%) | 0 | 0 | ||

| BNT162b2, Comirnaty, Pfizer–BioNTech | 3147/4407 (71·4%) | 212 (70·9%) | 59 (65·6%) | ||

| mRNA-1273, Spikevax, Moderna | 1259/4407 (28·6%) | 87 (29·1%) | 31 (34·4%) | ||

| Days between dose one and two, mean (range) | 40 (20–92) | 40 (21–69) | 40 (21–69) | ||

| Days between sampling and dose two | NA | 118 (43–146) | 33 (26–43) | ||

| Dose three of vaccination against COVID-19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Unvaccinated | 47 (1·0%) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Infection or vaccination status by third sampling§ | |||||

| Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 by PCR or rapid antigen test | 1227 (27·0%) | 0/210 (0%)¶ | 0/71 (0%)¶ | ||

| Dose three of vaccination against COVID-19 | 4354 (95·7%) | 210/210 (100%)¶ | 71/71 (100%)¶ | ||

| BNT162b2, Comirnaty, Pfizer–BioNTech | 2842/4354 (65·3%) | 145/210 (69·0%)¶ | 52/71 (73·2%)¶ | ||

| mRNA-1273, Spikevax, Moderna | 1512/4354 (34·7%) | 65/210 (31·0%)¶ | 19/71 (26·8%)¶ | ||

| Days between dose two and three, mean (range) | 196 (40–322) | 198 (138–271), n=210¶ | 194 (138–253), n=71¶ | ||

| Days between sampling and dose three | NA | 99 (82–123), n=210¶ | 79 (63–98), n=71¶ | ||

| Dose 4 of vaccination against COVID-19 | 68 (1·5%) | 0/210 (0%)¶ | 0/71 (0%)¶ | ||

| Breakthrough infections after dose three‖ | 1304/4298 (30·3%)** | 32/210 (15·2%)¶†† | 18/71 (25·4%)¶†† | ||

| Influenza vaccination, 2020–2021 | |||||

| Yes | 3145 (69·1%) | 222 (74·2%) | 59 (65·6%) | ||

| Data missing | 114 (2·5%) | 10 (3·3%) | 4 (4·4%) | ||

| Housing | |||||

| Long-term care facility | 6 (0·1%) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Data missing | 229 (5·0%) | 12 (4·0%) | 2 (2·2%) | ||

| Smoking | |||||

| Daily smoker | 221 (4·9%) | 9 (3·0%) | 2 (2·2%) | ||

| Data missing | 232 (5·1%) | 11 (3·7%) | 4 (4·4%) | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 | |||||

| <18·5 | 68 (1·5%) | 7 (2·3%) | 1 (1·1%) | ||

| 18·5–24·9 | 2163 (47·5%) | 138 (46·2%) | 43 (47·8%) | ||

| 25·0–29·9 | 1606 (35·3%) | 110 (36·8%) | 31 (34·4%) | ||

| ≥30·0 | 534 (11·7%) | 34 (11·4%) | 13 (14·4%) | ||

| Data missing | 180 (4·0%) | 10 (3·3%) | 2 (2·2%) | ||

| Chronic diseases or conditions | |||||

| At least one chronic disease‡‡ | 2184 (48·0%) | 146 (48·8%) | 44 (48·9%) | ||

| No chronic disease§§ | 2268 (49·8%) | 148 (49·5%) | 45 (50·0%) | ||

| Asthma | 423 (9·3%) | 22 (7·4%) | 5 (5·6%) | ||

| Chronic lung disease | 228 (5·0%) | 13 (4·3%) | 5 (5·6%) | ||

| Chronic heart or cardiovascular disease | 462 (10·2%) | 32 (10·7%) | 8 (8·9%) | ||

| Hypertension | 1468 (32·3%) | 104 (34·8%) | 32 (35·6%) | ||

| Myocardial infarction, anytime | 258 (5·7%) | 23 (7·7%) | 7 (7·8%) | ||

| Stroke, anytime | 204 (4·5%) | 13 (4·3%) | 4 (4·4%) | ||

| Diabetes | 345 (7·6%) | 23 (7·7%) | 4 (4·4%) | ||

| Chronic liver disease | 31 (0·7%) | 1 (0·3%) | 0 | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 52 (1·1%) | 2 (0·7%) | 0 | ||

| Neurological disease | 251 (5·5%) | 14 (4·7%) | 3 (3·3%) | ||

| Cancer, anytime | 812 (17·8%) | 50 (16·7%) | 17 (18·9%) | ||

| Cancer, active | 118 (2·6%) | 3 (1·0%) | 1 (1·1%) | ||

| Cancer, previous | 694 (15·2%) | 47 (15·7%) | 16 (17·8%) | ||

| Immunosuppressed¶¶ | 199 (4·4%) | 11 (3·7%) | 4 (4·4%) | ||

| Organ recipient | 27 (0·6%) | 1 (0·3%) | 1 (1·1%) | ||

| Immunodeficiency | 95 (2·1%) | 4 (1·3%) | 0 | ||

| Immunosuppressive medication | 31 (0·7%) | 8 (2·7%) | 4 (4·4%) | ||

| Data on all chronic conditions missing | 99 (2·2%) | 5 (1·7%) | 1 (1·1%) | ||

| Anamnestic Frailty Phenotype | |||||

| Non-frail, score=0 | 3427 (75·3%) | 230 (76·9%) | 73 (81·1%) | ||

| Prefrail, score=1 | 849 (18·7%) | 53 (17·7%) | 14 (15·6%) | ||

| Frail, score=2–3 | 184 (4·0%) | 11 (3·7%) | 1 (1·1%) | ||

| Data missing | 91 (2·0%) | 5 (1·7%) | 2 (2·2%) | ||

| Global Activity Limitation Index | |||||

| Not limited | 4036 (88·7%) | 266 (89·0%) | 83 (92·2%) | ||

| Limited | 483 (10·6%) | 29 (9·7%) | 6 (6·7%) | ||

| Data missing | 32 (0·7%) | 4 (1·3%) | 1 (1·1%) | ||

| On regular medication | |||||

| Yes | 3421 (75·2%) | 224 (74·9%) | 63 (70·0%) | ||

| Data missing | 11 (0·2%) | 0 | 0 | ||

Data are median (IQR) or n (%), unless otherwise stated. NA=not applicable.

Percentages shown as proportion of N=4551, N=299, or N=90, unless otherwise stated.

Status on June 26, 2021, date of which the last second round samples for cellular analysis were obtained.

Blood samples were selected from participants vaccinated with two vaccine doses per definition.

Status on March 21, 2022, date of which the last third round samples for cellular analysis were obtained.

Samples from participants with a sequential third sample, vaccinated with three doses only at the time of sampling and with no previous infection, were selected (210 of 299 participants in the antibody subset and 71 of 90 participants in the cellular subset) for the analysis after dose three.

Status on June 26, 2022 (at the close of the eighth questionnaire, before the dose four vaccination campaign).

Participants with three doses and no previous infections.

Previous infections or breakthrough infections were excluded per definition to explore vaccine specific responses in the 210 and 71 participants; hence the percentage of breakthrough infections appears lower than for the whole cohort.

Asthma, other chronic lung disease, diabetes, myocardial infarction, heart condition or cardiovascular disease, stroke (anytime), chronic liver disease, chronic kidney disease, neurological disease, cancer (anytime), immunosuppressed; note that hypertension is not included as a chronic disease or condition.

Not having any of the chronic diseases or conditions listed.

Based on the following question, “Do you have any of the following conditions? Yes or no.”

Almost half of participants reported having at least one chronic disease or condition (2184 [48·0%] of 4551), and 1468 (32·3%) self-reported hypertension. 3421 (75·2%) reported taking regular medication. Nevertheless, only 184 (4·0%) participants were frail, 849 (18·7%) were prefrail, and 483 (10·6%) reported limited function in daily activities. Very few lived in long-term care facilities (six [0·1%] of 4551). A minority had had bone fractures during the past five years (493 [10·8%] of 4551). These proportions were slightly lower for the cellular and antibody subsets (table 1). Many participants had a higher education (2867 [63·0%] of 4551; appendix pp 10–12).

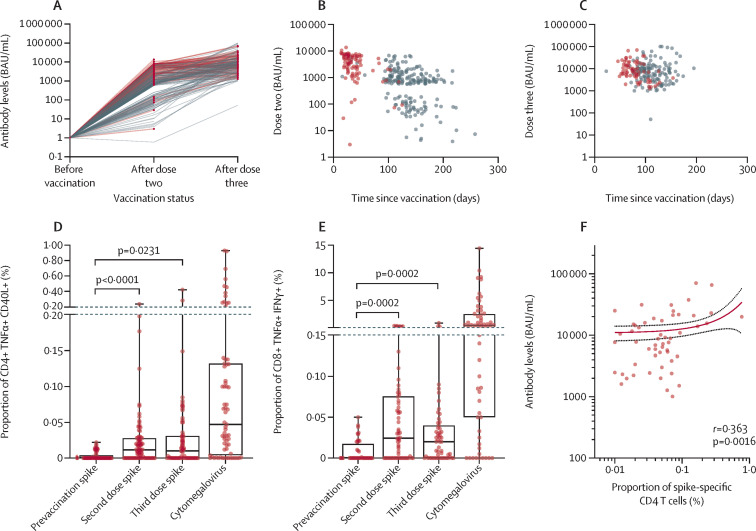

Most blood samples were seropositive for SARS-CoV-2 spike antibodies after the second dose (295 [98·7%] of 299), although responses showed wide heterogeneity. After the third dose, all were seropositive (n=210) with antibody levels mainly ranging from 103 to 105 BAU/mL (figure 1A ). Median time since vaccination was shorter for the cell sampling subset (33 days [IQR 26–43]; n=90) compared with all samples for antibody analysis (118 days [IQR 43–146]; n=299) after the second dose (figure 1B); and 79 days (IQR 63–98; n=71) and 99 days (IQR 82–123; n=210), respectively, after the third dose (figure 1C; table 1).

Figure 1.

Humoral and cellular responses after two and three doses of mRNA vaccine

(A) Individual anti-spike antibody concentrations before vaccination (n=211) and after two (n=299) and three doses (n=210; grey lines). Median time since vaccination was shorter for the subset with cell sampling (n=90; red lines); time between sampling and vaccination for each subset varied slightly between second (B) and third (C) vaccinations. CD4 (D) and CD8 (E) T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 spike peptides before vaccination (n=69) and after two (n=90) and three vaccine doses (n=71), and to cytomegalovirus pp65 peptides (n=69). Unstimulated background was subtracted from all conditions. (F) Correlation of post-vaccination receptor binding domain levels and spike-specific CD4 T cell responses after third dose (n=71) by non-linear regression analysis. Points indicate individual responses for all plots. Box-and-whisker plots (D–E) show the median, IQR, and range; all statistics calculated by paired Wilcoxon tests.

Overall, SARS-CoV-2 spike-specific CD4 and CD8 T cell responses were significantly increased after two doses (figure 1D–E). There was a further increase in the frequency of spike-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells after the third dose (figure 1D–E) in most individuals, although this did not reach statistical significance. CD4 T cell responses showed some correlation with antibody titres (r=0·363; figure 1F) after three doses, but CD8 T cells did not (appendix p 6). IFN-γ levels in cell supernatants after stimulation with spike peptides were significantly increased in samples after vaccination compared with baseline (appendix p 7). Most individuals had strong T cell responses to cytomegalovirus (figure 1D–E), showing that individuals also had detectable responses to non-SARS-CoV-2 antigens.

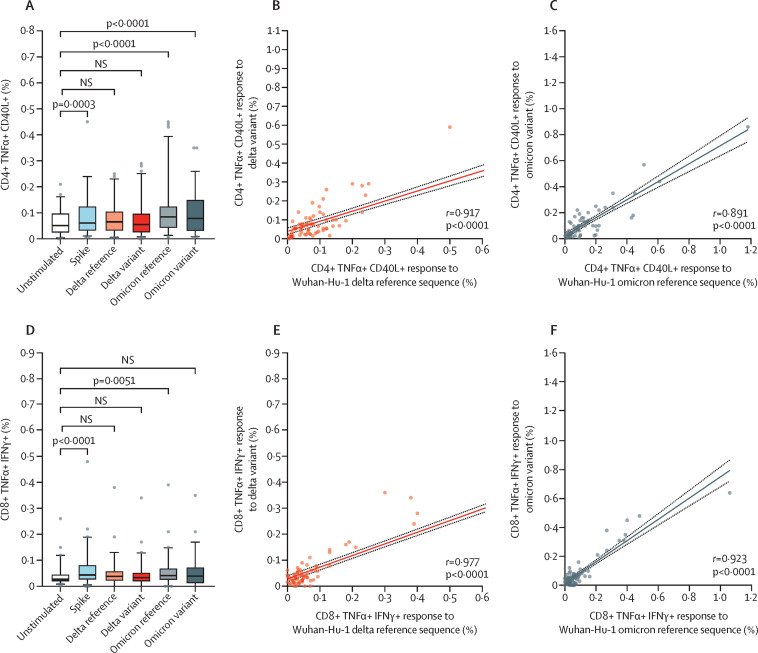

To assess the potential of vaccine-induced cross-protection against new SARS-CoV-2 VOCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were stimulated with spike peptides derived from the alpha, delta, and omicron variants after two or three vaccine doses, reflecting the circulating strains during sampling (figure 2 , appendix p 7). After two doses, CD4 and CD8 T cell responses against the alpha and delta variants were significantly upregulated (appendix p 7). Likewise, after three vaccine doses CD4 T cell responses against the omicron VOC increased, although CD8 T cell responses were predominantly low (figure 2D). Both CD4 and CD8 T cell responses to all VOCs correlated strongly with their corresponding wild-type reference peptides (after the second vaccine, alpha and delta responses for CD4 T cells, r=0·86 and r=0·85; CD8 T cells, r=0·75 and r=0·87; p<0·0001; appendix p 7), and improved further after the third dose (delta and omicron responses for CD4 T cells, r=0·91 and r=0·89; CD8 T cells r=0·98 and r=0·92; p<0·0001; figure 2B–C, E–F).

Figure 2.

Vaccine induced CD4 and CD8 T cells also respond to delta and omicron SARS-CoV-2 variants

T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 spike-specific peptides (n=71) after three vaccine doses. CD4 (A–C) and CD8 (D–F) T cell responses to mutated regions from SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern were upregulated compared with unstimulated cells. CD4 and CD8 T cell responses to the mutated regions correlated with their reference sequences for delta (B and E) and omicron (C and F), respectively. r and p values are shown on each plot. Box-and-whisker plots indicate the median, IQR, and 5th and 95th percentiles. NS=not significant.

We also investigated potential cross-reactive T cell responses to seasonal human coronaviruses. Before vaccination, cellular responses to seasonal coronavirus spike peptides were detectable in a small number of individuals but were generally low (appendix p 8); after vaccination CD4 and CD8 T cell responses to seasonal coronavirus spike peptides were detected in multiple individuals. Corresponding increases in responses to nucleocapsid peptides of the seasonal coronaviruses were not observed. Spike-specific seasonal coronavirus and SARS-CoV-2 responses showed significant correlation for both CD4 and CD8 T cells (appendix p 8) after vaccination, but there was no correlation between seasonal coronavirus nucleocapsid and SARS-CoV-2 spike responses (appendix p 8).

We then explored the association between demographic characteristics and health conditions with immune responses after vaccination. Primary vaccination with mRNA-1273 was significantly associated with higher antibody titres compared with BNT162b2 (p<0·001, n=299; appendix pp 14–15). There was a negative association between antibody levels and time since vaccination (p<0·001). Increased age was also negatively associated with antibody levels after primary vaccination in the univariate model, but not in the multivariate model. No association was found between the vaccine type given as dose three and responses after the third dose (table 2 , table 3 ). However, two doses of mRNA-1273 followed by one dose of BNT162b2 was associated with higher levels of antibodies and CD4 T cell responses compared with three doses of BNT162b2 (p=0·019 [n=210] and p=0·003 [n=71]; table 2, table 3). Two doses of BNT162b2 and an mRNA-1273 booster also gave higher antibody levels, although this was not significant (p=0·055, n=210). No other associations with CD4 or CD8 T cell responses were found after two or three doses (eg, sex, chronic lung and heart conditions, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, immunosuppression, obesity, frailty, or Global Activity Limitation Index score; table 3, appendix pp 16–21). Finally, antibody levels after the third dose were negatively associated with self-reported hypertension (p=0·003; table 2).

Table 2.

Median anti-receptor binding domain antibody levels (BAU/mL) after the third dose of the COVID-19 vaccine in the senior cohort, and median regression analysis to explore factors influencing antibody levels

| Participants (n=210)* | Anti-spike antibody levels (BAU/mL) |

Univariate median regression |

Multivariate median regression† |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI)‡ | p value | Coefficient (95% CI)‡ | p value | ||||

| Age, years | |||||||

| 65–70 | 88 (42%) | 7518 (4609 to 13 810) | Ref | .. | Ref | .. | |

| 71–75 | 77 (37%) | 7120 (3111 to 10 946) | −400 (−3049 to 2249) | 0·766 | −640 (−3428 to 2148) | 0·651 | |

| 76–80 | 106 (50%) | 7518 (4535 to 13 708) | −342 (−3453 to 2770) | 0·829 | 1644 (−1677 to 4965) | 0·330 | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 106 (50%) | 7518 (4535 to 13 708) | Ref | .. | Ref | .. | |

| Male | 104 (50%) | 7040 (3143 to 13 418) | −475 (−2732 to 1782) | 0·679 | −70 (−2456 to 2316) | 0·954 | |

| Vaccine type, dose three | |||||||

| BNT-162b2 | 145 (69%) | 7023 (2960 to 12 428) | Ref | .. | Ref§ | .. | |

| mRNA-1273 | 65 (31%) | 8092 (5481 to 13 912) | 1070 (−1382 to 3521) | 0·391 | 1546 (−1160 to 4252) | 0·261 | |

| Vaccine type, combinations | |||||||

| Three doses of BNT-162b2 | 115 (55%) | 5979 (2899 to 10 512) | Ref | .. | Ref | .. | |

| Three doses of mRNA-1273 | 31 (15%) | 7516 (5451 to 13 225) | 1537 (−1878 to 4951) | 0·376 | 2506 (−1148 to 6160) | 0·178 | |

| Two doses of BNT-162b2 plus mRNA-1273 | 34 (16%) | 8485 (5935 to 16 091) | 2898 (−396 to 6192) | 0·084 | 3309 (−68 to 6686) | 0·055 | |

| Two doses of mRNA-1273 plus BNT-162b2 | 30 (14%) | 10287 (4609 to 17 193) | 4723 (1263 to 8182) | 0·008 | 4240 (717 to 7763) | 0·019 | |

| Chronic condition | |||||||

| No | 108/207 (52%) | 7576 (3913 to 14 107) | Ref | .. | Ref | .. | |

| Yes | 99/207 (48%) | 7120 (3477 to 11 612) | −468 (−2723 to 1787) | 0·683 | −573 (−2932 to 1786) | 0·633 | |

| Asthma or chronic lung condition | |||||||

| No | 187/209 (89%) | 7186 (3898 to 13 912) | Ref | .. | Ref | .. | |

| Yes | 22/209 (11%) | 8407 (2817 to 10 512) | 1266 (−2407 to 4939) | 0·497 | −1743 (−5592 to 2107) | 0·373 | |

| Chronic heart or cardiovascular disease | |||||||

| No | 185/207 (89%) | 7274 (3404 to 13 708) | Ref | .. | Ref | .. | |

| Yes | 24/207 (11%) | 8631 (4555 to 12 086) | 2473 (−868 to 5813) | 0·146 | 2453 (−1175 to 6081) | 0·184 | |

| Hypertension | |||||||

| No | 127/209 (61%) | 7969 (3944 to 15 567) | Ref | .. | Ref | .. | |

| Yes | 82/209 (39%) | 5948 (3024 to 10 702) | −2008 (−4227 to 211) | 0·076 | −2619 (−5116 to −122) | 0·040 | |

| Diabetes | |||||||

| No | 194/210 (92%) | 7363 (3898 to 13 377) | Ref | .. | Ref | .. | |

| Yes | 16/210 (8%) | 7923 (3035 to 16 775) | 1348 (−2783 to 5478) | 0·521 | 531 (−4143 to 5206) | 0·823 | |

| Cancer (anytime) | |||||||

| No | 175/210 (83%) | 7564 (3477 to 13 708) | Ref | .. | Ref | .. | |

| Yes | 35/210 (17%) | 7035 (3828 to 13 377) | −529 (−3428 to 2370) | 0·719 | −500 (−3633 to 2633) | 0·753 | |

| Immunosuppressed | |||||||

| No | 202/209 (97%) | 7363 (3898 to 13 708) | Ref | .. | Ref | .. | |

| Yes | 7/209 (3%) | 4977 (2478 to 13 377) | −2476 (−8697 to 3745) | 0·434 | 1421 (−5072 to 7915) | 0·666 | |

| Obesity, ≥30·0 kg/m2 | |||||||

| No | 179/203 (88%) | 7274 (3828 to 13 311) | Ref | .. | Ref | .. | |

| Yes | 24/203 (12%) | 7881 (3641 to 18 560) | 1442 (−1947 to 4831) | 0·402 | 746 (−2963 to 4455) | 0·692 | |

| Frailty Index | |||||||

| Not frail | 158/205 (77%) | 7576 (4258 to 15 160) | Ref | .. | Ref | .. | |

| Prefrail or frail | 47/205 (23%) | 7023 (2666 to 10 889) | −565 (−3402 to 2272) | 0·695 | −202 (−2908 to 2504) | 0·883 | |

| Global Activity Limitation Index | |||||||

| Not limited | 185/206 (90%) | 7520 (3917 to 13 896) | Ref | .. | Ref | .. | |

| Limited | 21/206 (10%) | 5919 (2176 to 11 612) | −1601 (−5322 to 2120) | 0·397 | −1307 (−5173 to 2559) | 0·506 | |

| Age, per year | 210 | NA | −41 (−328 to 245) | 0·776 | 88 (−243 to 418) | 0·601 | |

| Time since vaccination, per day | 210 | NA | −36 (−75 to 2) | 0·067 | −31 (−74 to 13) | 0·163 | |

| BMI, per kg/m2 | 203 | NA | −13 (−253 to 227) | 0·916 | 46 (−217 to 310) | 0·729 | |

Data are n (%) or median (IQR), unless otherwise stated. NA=not applicable.

For some factors, data were missing for up to seven participants; these were excluded in the analysis.

Adjusted for age (continuous variable), time since vaccination (continuous variable), sex, and vaccine combination of the three doses (unless the covariate was the exposure variable).

The coefficient is the difference in the median BAU/mL titre between the groups being compared, or per unit (continuous variables); for example, in the univariate model the median antibody titre after two doses of mRNA-1273 and one dose of BNT-162b2 is 4723 BAU/mL higher compare to three doses of BNT-162b2, and 4240 BAU/mL higher in the multivariate model.

Adjusted for age (continuous variable), time since vaccination (continuous variable), and sex.

Table 3.

Median CD4 spike responses (%) after the third dose of the COVID-19 vaccine in the senior cohort, and median regression analysis to explore factors influencing CD4 spike response

| Participants (n=71)* | Percentage of CD4 spike cells |

Univariate median regression |

Multivariate median regression† |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95 CI%)‡ | p value | Coefficient (95 CI%)‡ | p value | ||||

| Age, years | |||||||

| 65–70 | 36 (51%) | 0·042 (0·016 to 0·074) | Ref | Ref | |||

| 71–75 | 23 (32%) | 0·02 (0·000 to 0·060) | −0·024 (−0·055 to 0·007) | 0·121 | −0·010 (−0·041 to 0·021) | 0·513 | |

| 76–80 | 12 (17%) | 0·006 (0·000 to 0·055) | −0·032 (−0·070 to 0·007) | 0·104 | −0·029 (−0·067 to 0·009) | 0·136 | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 34 (48%) | 0·021 (0·000 to 0·052) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Male | 37 (52%) | 0·04 (0·010 to 0·070) | 0·017 (−0·008 to 0·043) | 0·181 | 0·003 (−0·021 to 0·027) | 0·812 | |

| Vaccine type, dose three | |||||||

| BNT-162b2 | 52 (73%) | 0·024 (0·000 to 0·062) | Ref | Ref§ | |||

| mRNA-1273 | 19 (27%) | 0·04 (0·018 to 0·069) | 0·015 (−0·017 to 0·047) | 0·359 | 0·010 (−0·020 to 0·039) | 0·516 | |

| Vaccine type, combinations | |||||||

| Three doses of BNT-162b2 | 43 (61%) | 0·019 (0·000 to 0·050) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Three doses of mRNA-1273 | 12 (17%) | 0·049 (0·037 to 0·072) | 0·032 (−0·004 to 0·068) | 0·082 | 0·017 (−0·022 to 0·056) | 0·389 | |

| Two doses of BNT-162b2 plus mRNA-1273 | 7 (10%) | 0·018 (0·000 to 0·067) | −0·001 (−0·046 to 0·044) | 0·965 | −0·003 (−0·047 to 0·042) | 0·909 | |

| Two doses of mRNA-1273 plus BNT-162b2 | 9 (13%) | 0·089 (0·070 to 0·161) | 0·070 (0·029 to 0·111) | 0·001 | 0·062 (0·022 to 0·101) | 0·003 | |

| Chronic condition | |||||||

| No | 40/71 (56%) | 0·031 (0·005 to 0·068) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Yes | 31/71 (44%) | 0·04 (0·000 to 0·061) | 0·007 (−0·020 to 0·034) | 0·612 | −0·002 (−0·030 to 0·026) | 0·876 | |

| Asthma or chronic lung condition | |||||||

| No | 64/70 (91%) | 0·03 (0·000 to 0·068) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Yes | 6/70 (9%) | 0·042 (0·013 to 0·050) | 0·012 (−0·046 to 0·070) | 0·682 | 0·017 (−0·033 to 0·066) | 0·504 | |

| Chronic heart or cardiovascular condition | |||||||

| No | 64/70 (91%) | 0·024 (0·000 to 0·062) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Yes | 6/70 (9%) | 0·055 (0·040 to 0·093) | 0·035 (−0·019 to 0·089) | 0·204 | 0·048 (−0·003 to 0·099) | 0·066 | |

| Hypertension | |||||||

| No | 43 (61%) | 0·038 (0·010 to 0·070) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Yes | 28 (39%) | 0·033 (0·000 to 0·062) | −0·005 (−0·035 to 0·025) | 0·742 | −0·009 (−0·032 to 0·015) | 0·480 | |

| Diabetes | |||||||

| No | 68 (96%) | 0·036 (0·010 to 0·068) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Yes | 3 (4%) | 0 (0·000 to 0·061) | −0·038 (−0·105 to 0·029) | 0·261 | −0·044 (−0·105 to 0·017) | 0·153 | |

| Cancer, anytime | |||||||

| No | 57 (80%) | 0·032 (0·010 to 0·061) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Yes | 14 (20%) | 0·047 (0·000 to 0·090) | 0·018 (−0·019 to 0·055) | 0·332 | 0·015 (−0·017 to 0·048) | 0·343 | |

| Immunosuppression | |||||||

| No | 69 (97%) | 0·033 (0·001 to 0·063) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Yes | 2 (3%) | 0·040 (0·010 to 0·070) | 0·037 (−0·041 to 0·115) | 0·348 | 0·037 (−0·049 to 0·122) | 0·394 | |

| Obesity, ≥30·0 kg/m2 | |||||||

| No | 61/70 (87%) | 0·028 (0·001 to 0·063) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Yes | 9/70 (13%) | 0·048 (0·010 to 0·073) | 0·020 (−0·019 to 0·059) | 0·310 | 0·020 (−0·018 to 0·057) | 0·298 | |

| Frailty Index | |||||||

| Not frail | 57/69 (83%) | 0·028 (0·001 to 0·070) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Prefrail or frail | 12/69 (17%) | 0·044 (0·016 to 0·061) | 0·012 (−0·031 to 0·055) | 0·581 | 0·007 (−0·029 to 0·043) | 0·685 | |

| Global Activity Limitation Index | |||||||

| Not limited | 65/70 (93%) | 0·032 (0·010 to 0·067) | Ref | Ref | |||

| Limited | 5/70 (7%) | 0·040 (0·000 to 0·061) | 0·008 (−0·045 to 0·061) | 0·762 | −0·004 (−0·053 to 0·045) | 0·870 | |

| Age, per year | 71 | NA | −0·004 (−0·008 to −0·001) | 0·027 | −0·003 (−0·006 to 0·001) | 0·152 | |

| Time since vaccination, per day | 71 | NA | 0·000 (−0·001 to 0·001) | 0·711 | 0·000 (−0·001 to 0·001) | 0·753 | |

| BMI, per kg/m2 | 70 | NA | 0·002 (−0·001 to 0·006) | 0·178 | 0·002 (−0·002 to 0·005) | 0·324 | |

Data are n (%) or median (IQR), unless otherwise specified. NA=not applicable.

For some factors, data were missing for up to two participants; these were excluded in the analysis.

Adjusted for age (continuous variable), time since vaccination (continuous variable), sex and vaccine combination of the three doses (unless the covariate was the exposure variable).

The coefficient is the difference in the median percentage increase in the CD4 spike response between the groups being compared, or per unit (continuous variables); for example, in the univariate model, the median CD4 spike response after two doses of mRNA-1273 and one dose of BNT-162b2 is 0·070% higher compared with three doses of BNT-162b2, and 0·062% higher in the multivariate model.

Adjusted for age (continuous variable), time since vaccination (continuous variable), and sex.

Lastly, we explored the number of breakthrough infections after three doses. In total, 1304 (30·3%) of 4298 participants had a breakthrough infection. The percentage was lower in the antibody (32 [15·2%] of 210) and cellular (18 [25·4%] of 71) subsets due to exclusion of cases infected before sampling (table 1). As cellular responses might be associated with reduced severity of disease, we explored the self-reported severity in this subset (n=71). Of the 15 of 18 participants who had breakthrough infections and self-reported their degree of illness, 12 (80%) of 15 reported “not/barely ill”; two (13%) of 15 “moderately ill, bedridden for several days”; and one (7%) of 15 “very ill”. According to MSIS, none were hospitalised. Since most participants reported very mild illness, this provided limited power for further analysis on associations with cellular responses.

Median antibody levels in those with (32 of 210) and without breakthrough infections (178 of 210) measured before infection were not statistically different (7053 BAU/mL [IQR 3505–14 692] vs 7518 BAU/mL [IQR 3828–13 377], p=0·88; appendix p 9). The median number of days between dose three and the end of follow-up was similar for both groups (215 days [IQR 206–227] vs 217 days [IQR 202–223], respectively; p=0·73).

Discussion

Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 protect older adults against severe disease,3, 4 but durability and protection against new VOCs is still under examination. We have established a longitudinal cohort for studying the consequences of the pandemic in adults aged 65–80 years showing that two and three doses of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines generate spike-specific CD4 and CD8 T cell responses, high seroconversion rates, and high antibody titres. Both vaccine type and time since vaccination influenced antibody levels after primary vaccination. Hypertension was associated with lower antibody responses after the third dose. Heterologous booster vaccination was beneficial for the anti-spike antibody and CD4 T cell response, particularly two doses of mRNA-1273 followed by one dose of BNT162b2. Furthermore, CD4 T cells responded to the alpha, delta, and omicron VOCs and responses to the reference and mutated peptides strongly correlated, suggesting that individuals who mount a strong response to vaccine-derived wild-type spike peptides also respond strongly to VOCs. Overall, breakthrough infections after booster vaccination resulted in mild disease. Finally, we found that T cell responses to seasonal human coronavirus spike peptides increased after vaccination. This correlation of spike-specific seasonal coronavirus and SARS-CoV-2 responses suggests that vaccination could lead to cross-protection to other VOCs and to seasonal coronaviruses.

Vaccine type, heterologous booster vaccination, age, and time since vaccination have previously been identified as predictors of anti-spike antibody responses.4, 6, 21 We did not find clear age-related differences, but the age range was small and excluded the most elderly. Disentangling the effects of age and time since vaccination is difficult in this type of study as time intervals were longer for older participants prioritised for vaccination and increasing age might correspond with poorer immune responses. Lower antibody levels after dose two might partly be explained by waning, since 25% of the participants were sampled more than 146 days after vaccination. A third dose improved humoral and cellular responses in participants, supporting previous studies showing that elderly individuals require more than two vaccine doses.22, 23 Booster vaccination increased the frequency of spike-specific T cells found in individuals and the proportion of individuals with detectable CD4 T cell responses. We found an association between lower antibody levels and hypertension after the third dose. Unlike other studies,24, 25 we did not find this association after two doses, possibly due to insufficient titres after dose two and heterogeneous responses in the seniors. We found no other significant predictors of vaccine-induced spike-specific CD4 or CD8 T cells. In general, these responses showed wide heterogeneity, consistent with other studies.3 The absence of associations with other factors might be due to a small group size, and varying time between sampling and vaccination.

Vaccine efficacy against emerging VOCs is an ongoing concern. Our results show that vaccine-induced CD4 T cell responses recognised mutated epitopes in the alpha, delta, and omicron VOCs. Moreover, CD8 T cell responses against the VOCs were increased after a third vaccine dose, potentially leading to less susceptibility to viral evasion.12, 13, 26 The 15-mer spike peptides used might also skew cellular responses towards CD4 T cells, under-representing spike-specific CD8 T cell responses. Nevertheless, these data suggest that vaccine-induced cellular cross-protection against SARS-CoV-2 VOCs in older adults might compensate for evasion of neutralising antibodies by VOCs with mutated receptor-binding domains.26

Antibody levels in those with and without breakthrough infections were similar, but the ability to neutralise new VOCs might differ. Almost all breakthrough infections reported very mild illness, providing limited power for further analysis here. However, this supports our interpretation that healthy seniors generate good spike-specific cellular responses which protect against severe disease (hospitalisation or death). This is consistent with a recent study from the same cohort, showing that the effectiveness of booster vaccination increased with increasing self-reported COVID-19 severity.27

It is not yet clear whether cross-reactivity with other human seasonal coronaviruses contributes to pre-existing immunity.13 We observed significant increases in the frequency of T cells responding to seasonal coronavirus spike peptides after vaccination and moderate to strong correlation between T cell responses to seasonal coronaviruses and SARS-CoV-2, but no increased response to seasonal coronavirus nucleocapsid peptides. This strongly suggests that SARS-CoV-2 vaccination generates T cells capable of cross-reacting with seasonal coronaviruses rather than unrelated infections with seasonal coronaviruses in the sampling interim. However, it is unclear whether these are de novo responses or cross-reactive expansions of existing seasonal coronavirus-specific cells. Other studies have found that vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 boosts T cell responses against the seasonal coronavirus HCoV-NL63,28 and pre-existing seasonal coronavirus-specific T cells might prevent the establishment of SARS-CoV-2 infection.29 Other studies argue against clinical protection from cross-reactive immunity.13 Further studies are needed to map the pre-existing cross-reactive T cell repertoire and assess to what extent such T cells mediate the protective response against SARS-CoV-2.

A strength of this cohort is the large sample size with ongoing data collection and high participation rates. Baseline samples were acquired before widespread vaccination. Infection rates in Norway were low before the third dose became available (Oct 5, 2021), but increased in February–March, 2022, corresponding to the omicron VOC wave. Close monitoring through the national infection registry and self-reported testing enabled the exclusion of these cases, thus our data represent mRNA vaccine-induced immune responses in this population.

The vaccination coverage in the cohort was high at the time of sampling (over 95%), consistent with the general population for this age group. However, the cohort might under-represent individuals with frailties and chronic conditions, because only 10·6% of participants had limitations in daily activities compared with 20% of Norwegian adults aged 67–79 years.30 The cohort is also skewed towards a higher educational level than the national average for adults over 67 years (32·0% vs 6·6% having more than 4 years of higher education, respectively).30 Less digitally-enabled individuals might be under-represented, as online consent and questionnaire participation was a prerequisite. Epidemiological variables obtained from questionnaires might be subject to recall bias, although frequent questionnaires reduce this risk. Finally, this cohort is limited to a city region, and the upper age limit at enrolment was 80 years, excluding people above that age.

Further studies in older adults are needed to identify how cellular and humoral responses change with additional vaccine doses and whether vaccine-induced immunity reaches a plateau. Blood sampling and examination of in-depth immune phenotypes and epidemiological factors is ongoing to identify predictors of high or low responders. A better understanding of the heterogeneity of immune responses in older adults might ultimately enable a more personalised approach to vaccination in this diverse group and better protection against COVID-19.

Data sharing

The data analysed in this study consist of sensitive information on an individual level. Due to protection of privacy and restrictions from the Norwegian Data Inspectorate and the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, the data are not publicly available.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants in the senior cohort. We also thank Ingvild Bokn and all the other staff at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and Oslo University Hospital involved in data collection, biobanking, and data management. This work was supported by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, the Norwegian Ministry of Health, through a programme for COVID-19 vaccination surveillance, the Research Council of Norway (312693), and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations.

Contributors

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.WHO Ageing and health. Oct 1, 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 risks and vaccine information for older adults. August 4, 2021. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/119720

- 3.Collier DA, Ferreira IATM, Kotagiri P, et al. Age-related immune response heterogeneity to SARS-CoV-2 vaccine BNT162b2. Nature. 2021;596:417–422. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03739-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward H, Whitaker M, Flower B, et al. Population antibody responses following COVID-19 vaccination in 212,102 individuals. Nat Commun. 2022;13:907. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28527-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldblatt D, Alter G, Crotty S, Plotkin SA. Correlates of protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 disease. Immunol Rev. 2022;310:6–26. doi: 10.1111/imr.13091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levin EG, Lustig Y, Cohen C, et al. Waning immune humoral response to BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine over 6 months. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:e84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2114583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Planas D, Veyer D, Baidaliuk A, et al. Reduced sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 variant delta to antibody neutralization. Nature. 2021;596:276–280. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03777-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dejnirattisai W, Shaw RH, Supasa P, et al. Reduced neutralisation of SARS-CoV-2 omicron B.1.1.529 variant by post-immunisation serum. Lancet. 2022;399:234–236. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02844-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt F, Muecksch F, Weisblum Y, et al. Plasma neutralization of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:599–601. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2119641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goel RR, Painter MM, Apostolidis SA, et al. mRNA vaccines induce durable immune memory to SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern. Science. 2021;374 doi: 10.1126/science.abm0829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kared H, Wolf AS, Alirezaylavasani A, et al. Immune responses in omicron SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection in vaccinated adults. Nat Commun. 2022;13 doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31888-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J, Chandrashekar A, Sellers D, et al. Vaccines elicit highly conserved cellular immunity to SARS-CoV-2 omicron. Nature. 2022;603:493–496. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04465-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moss P. The T cell immune response against SARS-CoV-2. Nat Immunol. 2022;23:186–193. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-01122-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seematter-Bagnoud L, Santos-Eggimann B. Population-based cohorts of the 50s and over: a summary of worldwide previous and ongoing studies for research on health in ageing. Eur J Ageing. 2006;3:41–59. doi: 10.1007/s10433-006-0022-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoogendijk EO, van der Horst MHL, Poppelaars J, van Vliet M, Huisman M. Multiple domains of functioning in older adults during the pandemic: design and basic characteristics of the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam COVID-19 questionnaire. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33:1423–1428. doi: 10.1007/s40520-021-01829-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holt H, Relton C, Talaei M, et al. Cohort profile: longitudinal population-based study of COVID-19 in UK adults (COVIDENCE UK) medRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1101/2022.06.20.22276205. published online June 24. (preprint). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pedone C, Costanzo L, Cesari M, Bandinelli S, Ferrucci L, Incalzi RA. Are performance measures necessary to predict loss of independence in elderly people? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71:84–89. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jagger C, Gillies C, Cambois E, Van Oyen H, Nusselder W, Robine JM. The Global Activity Limitation Index measured function and disability similarly across European countries. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:892–899. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tran TT, Vaage EB, Mehta A, et al. Titers of antibodies against ancestral SARS-CoV-2 correlate with levels of neutralizing antibodies to multiple variants. NPJ Vaccines. 2022;7:174. doi: 10.1038/s41541-022-00586-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGreevy KM, Lipsitz SR, Linder JA, Rimm E, Hoel DG. Using median regression to obtain adjusted estimates of central tendency for skewed laboratory and epidemiologic data. Clin Chem. 2009;55:165–169. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.106260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atmar RL, Lyke KE, Deming ME, et al. Homologous and heterologous COVID-19 booster vaccinations. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1046–1057. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Renia L, Goh YS, Rouers A, et al. Lower vaccine-acquired immunity in the elderly population following two-dose BNT162b2 vaccination is alleviated by a third vaccine dose. Nat Commun. 2022;13 doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32312-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romero-Olmedo AJ, Schulz AR, Hochstätter S, et al. Induction of robust cellular and humoral immunity against SARS-CoV-2 after a third dose of BNT162b2 vaccine in previously unresponsive older adults. Nat Microbiol. 2022;7:195–199. doi: 10.1038/s41564-021-01046-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soegiarto G, Wulandari L, Purnomosari D, et al. Hypertension is associated with antibody response and breakthrough infection in health care workers following vaccination with inactivated SARS-CoV-2. Vaccine. 2022;40:4046–4056. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.05.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lustig Y, Sapir E, Regev-Yochay G, et al. BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine and correlates of humoral immune responses and dynamics: a prospective, single-centre, longitudinal cohort study in health-care workers. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:999–1009. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00220-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harvey WT, Carabelli AM, Jackson B, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19:409–424. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00573-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laake I, Skodvin SN, Blix K, et al. Effectiveness of mRNA booster vaccination against mild, moderate, and severe COVID-19 caused by the omicron variant in a large, population-based, Norwegian cohort. J Infect Dis. 2022;226:1924–1933. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woldemeskel BA, Garliss CC, Blankson JN. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines induce broad CD4+ T cell responses that recognize SARS-CoV-2 variants and HCoV-NL63. J Clin Invest. 2021;131 doi: 10.1172/JCI149335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swadling L, Diniz MO, Schmidt NM, et al. Pre-existing polymerase-specific T cells expand in abortive seronegative SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2022;601:110–117. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04186-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Statistics Norway Statbank Norway. 2022. https://www.ssb.no/en/statbank

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data analysed in this study consist of sensitive information on an individual level. Due to protection of privacy and restrictions from the Norwegian Data Inspectorate and the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, the data are not publicly available.