Abstract

Neovascularization or angiogenesis is required for the progression of chronic inflammation. The mechanism of inflammatory neovascularization in tuberculosis remains unknown. Trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate (TDM) purified from Mycobacterium tuberculosis was injected into rat corneas. TDM challenge provoked a local granulomatous response in association with neovascularization. Neovascularization was seen within a few days after the challenge, with the extent of neovascularization being dose dependent, although granulomatous lesions developed 14 days after the challenge. Cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-8 (IL-8), IL-1β, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), were found in lesions at the early stage (within a few days after the challenge) and were detectable until day 21. Neovascularization was inhibited substantially by neutralizing antibodies to VEGF and IL-8 but not IL-1β. Treatment with anti-TNF-α antibodies resulted in partial inhibition. TDM possesses pleiotropic activities, and the cytokine network plays an important role in the process of neovascularization.

The pathogenicity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is related to its ability to escape killing by macrophages and induce delayed-type hypersensitivity (10). This has been attributed to several components of the M. tuberculosis cell wall. Cord factor (trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate; TDM), which is a surface glycolipid, causes M. tuberculosis to grow in serpentine cords in vitro. Virulent strains of M. tuberculosis have cord factor on their surfaces, whereas avirulent strains do not, and injection of purified cord factor into mice induces lesions characterized by chronic granulomatous inflammation (2, 20).

Macrophages stimulated with TDM produce proinflammatory and type 1 helper-T-cell-inducing cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 (IL-1), chemotactic factors, and IL-12 (32, 40). Mycobacterial TDM can induce granuloma formation by its ability to stimulate cytokine production from inflammatory cells in the host (36, 41).

Although TDM induces chronic granulomatous inflammation in the lungs, livers, and spleens of experimental animals, little is known about the neovascularization that is a feature of chronic inflammation (16). At the site of M. tuberculosis infection, inflammatory cells, including neutrophils and macrophages, are recruited and activated (9). Cytokines generated locally by such cells participate in both regulation of inflammation and neovascularization (26, 30). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) regulates the process of neovascularization (29). Neovascularization participates in both development of inflammatory responses and progression of chronic diseases (16, 29).

The precise mechanism of neovascularization in mycobacterial disease remains unknown. To clarify the role of mycobacterial TDM in inflammatory neovascularization, we have analyzed the histopathology and cytokine profile of corneal lesions induced by TDM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Rats.

Specific-pathogen-free female Wistar rats, 11 weeks of age, were purchased from the Charles River Japan, Co., Tokyo, Japan. No significant changes in the body weight were observed during the experimental period, regardless of treatment.

Reagents.

Mycobacterial TDM was prepared and purified as described previously (27, 34). Briefly, M. tuberculosis Aoyama B was cultivated in Sauton medium for 5 to 6 weeks at 37°C. Mycobacteria were autoclaved and then were disrupted ultrasonically and suspended in chloroform-methanol to extract lipids. The chloroform layer was collected and dried. Crude lipids were precipitated in acetone, subsequently in chloroform-methanol (1:2, by volume), and then in tetrahydrofuran. Precipitated crude lipids were separated by silica gel thin-layer chromatography (TLC; Uniplate; Analtech, Newark, Del.) with chloroform-methanol-water (90:10:1). TDM was visualized with iodine vapor and then recovered from TLC plates by passage through a column of silica gel (Wakogel C-200; Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan) with chloroform-methanol (3:1, by volume). The purification step was repeated until a single spot was obtained by TLC. The purity of glycolipid was confirmed by fast-atom bombardment mass spectrometry of the intact molecule with a double-focusing mass spectrometer (JMS SX102A; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) as described previously (14). Pure TDM was preserved in chloroform-methanol (3:1, by volume). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS); from Escherichia coli serotype O111:B4) and N-acetylmuramyl-d-alanyl-d-isoglutamine (MDP) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.

Induction of corneal neovascularization by TDM.

Induction of an angiogenic reaction is a true demonstration of neovascularization, because the cornea is normally avascular (21, 28). The cornea was anesthetized with a topical application of 0.4% oxybuprocaine hydrochloride (Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Osaka, Japan). A 1-mm-long transverse incision of the cornea was made at the center with microblades (K-715; Feather Safety Razor, Osaka, Japan). A pocket was subsequently formed in the corneal stroma, reaching to within 1.25 mm of the limbus. TDM was dried in a 24-gauge needle (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) and squeezed into the corneal pocket. The cornea challenged with TDM was observed daily for 3 weeks, and photographs were taken using a digital video camera mounted on a slit lamp biomicroscope (photo slit lamp SC1200; KOWA Co., Nagoya, Japan). Corneal neovascularization was assessed by measuring the maximum lengths and widths of new vessels by photography (35). The intensity of corneal edema was consistent with the presence of an inflammatory response.

Histologic examination.

The cornea was excised and fixed in 10% formalin. Routine paraffin-embedded, hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections were prepared from each cornea. Factor VIII-related antigen in blood vessels as an endothelial marker (17) was visualized by immunohistochemistry (16). In brief, frozen tissue sections were immunostained with polyclonal rabbit antibody against human factor VIII-related antigen (Dako, Carpinteria, Calif.), which is known to cross-react with rat factor VIII (33). Biotinylated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) and peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin were used as second and third reagents, respectively. The substrate for the red color reaction was 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole in N,N-dimethylformamide (Sigma Chemical Co.). After being rinsed with distilled water, sections were observed microscopically.

EIAs for cytokines.

Rats were sacrificed at intervals of 1.5, 3, 6, and 12 h and 1, 3, 7, 14, and 21 days after TDM challenge. Corneas were removed aseptically and then homogenized in 300 μl of 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4) containing 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1 μg of aprotinin-isopropanol per ml, and 100 μg of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride-isopropanol (Sigma Chemical Co.) per ml. Each sample was transferred to a 1-ml tube and centrifuged at 7,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernate was collected and assayed for antigenic cytokines using commercially available enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kits, such as the Quantikine mouse VEGF immunoassay (sensitivity, <3.0 pg/ml; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.), Panatest A series rat IL-8 (<4.7 pg/ml; Panapharm Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan), rat TNF-α (<4.0 pg/ml; Biosource International), and IL-1β enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (<3.0 pg/ml; Biosource International). The mouse VEGF assay kit is also available for measuring rat VEGF, according to the manufacture's instructions. Protein contents of supernates were measured with a DC protein assay kit (sensitivity, <0.2 mg protein/ml; Bio-Rad, San Diego, Calif.). EIAs were performed in duplicate.

Inhibition of TDM-induced corneal neovascularization by neutralizing anti-cytokine antibodies.

Rabbit anti-rat TNF-α (500 ng/ml neutralized 50% of the bioactivity due to 25 pg of TNF-α per ml), IL-1β (10 ng/ml neutralized 50% of the bioactivity due to 50 pg of IL-1β per ml), and VEGF (100 ng/ml neutralized 50% of the bioactivity due to 10 ng of VEGF per ml) polyclonal antibodies were purchased from R&D Systems, and anti-rat IL-8 polyclonal antibody (10 ng/ml neutralized 50% of the bioactivity due to 50 pg of IL-8 per ml) was obtained from Panapharm Laboratories. Ten nanograms of each anticytokine antibody was injected into the corneal pocket. Immediately after the treatment, rats were challenged with TDM.

Statistical analyses.

Each group had at least six rats. Data were analyzed with a Power Macintosh G3 computer using a statistical software package (StatView 5.0; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, N.C.) and expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD). Data that appeared statistically significant were compared by analysis of variance for comparison of the means of multiple groups, and values were considered significant if P values were less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Induction of corneal neovascularization by TDM challenge.

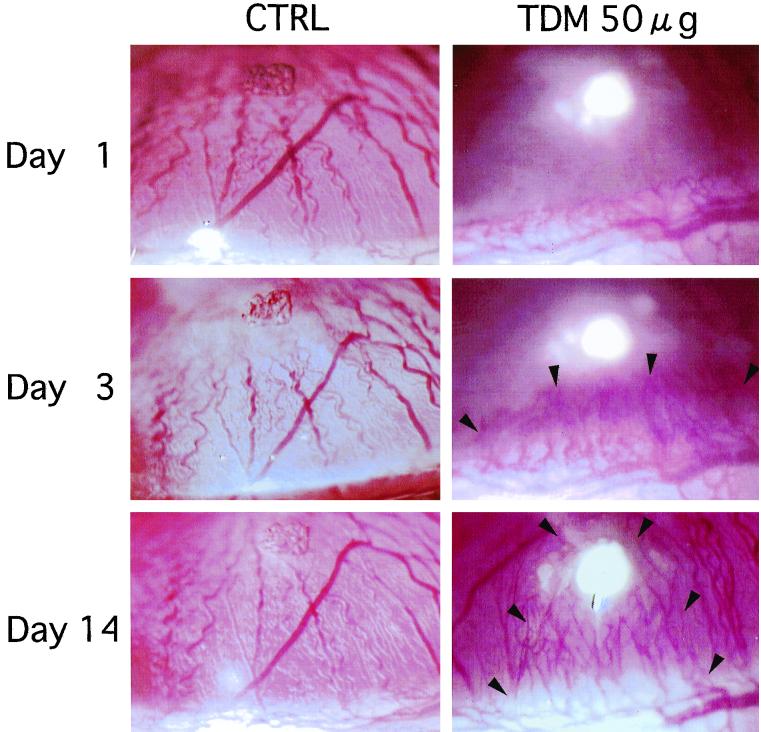

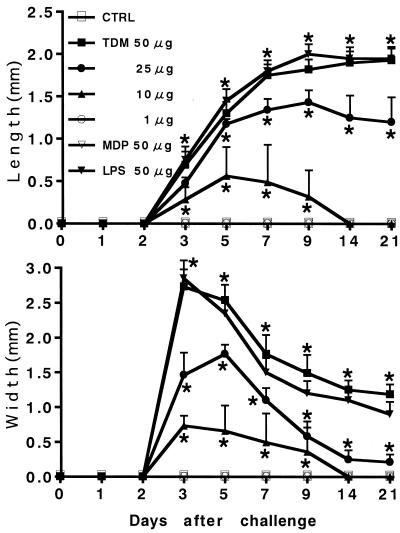

Corneal neovascularization was seen in groups of rats challenged with 10, 25, and 50 μg of TDM but not in controls or the group challenged with 1 μg of TDM (Fig. 1). Neovascularization began sprouting into the corneal stroma from the limbus to the site of TDM injection within a few days after the challenge. In the group challenged with 10 μg of TDM, neovascularization subsided gradually within 2 weeks. In contrast, in groups challenged with 25 and 50 μg of TDM, neovascularization developed and persisted more than 3 weeks after the challenge. Figure 2 shows the time kinetics of neovascularization induced by various doses of TDM. The lengths and widths of new vessels induced by TDM are shown in a dose-dependent manner. The growth rates of new vessels were 0.11 ± 0.03 (10 μg of TDM), 0.17 ± 0.01 (25 μg), and 0.18 ± 0.01 (50 μg) mm/day for vessel length and 0.24 ± 0.03 (10 μg), 0.34 ± 0.01 (25 μg), and 0.92 ± 0.04 (50 μg) mm/day for vessel width. In groups of rats that showed neovascularization, corneal opacity due to infiltration of inflammatory cells was found at day 2 and persisted up to 10 days after the challenge, which was most prominent in the group of rats challenged with 50 μg of TDM. Based on these results, we used 50 μg of TDM as the optimal dose for induction of corneal neovascularization as determined by a dose-response experiment with doses ranging from 1 to 50 μg. In contrast to TDM, MDP (50 μg) from mycobacterial peptidoglycan was incapable of inducing angiogenesis, although LPS (50 μg) from E. coli could induce angiogenesis. The potency and time kinetics of angiogenesis induced by LPS were similar to those of TDM (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Induction of corneal neovascularization in rats by TDM challenge. Corneas challenged with vehicle alone did not develop neovascularization. TDM challenge induced corneal neovascularization by day 3 that persisted up to day 21 in a dose-dependent fashion. Arrowheads indicate new blood vessels in the cornea.

FIG. 2.

Time kinetic study of corneal neovascularization induced by TDM challenge. New vessel growth is expressed as the maximal lengths and widths of new vessels. Data are means ± SD (n = 10/group). The asterisks indicate statistical significance relative to results with control (CTRL) rats challenged with vehicle alone (P < 0.02).

Histologic examination.

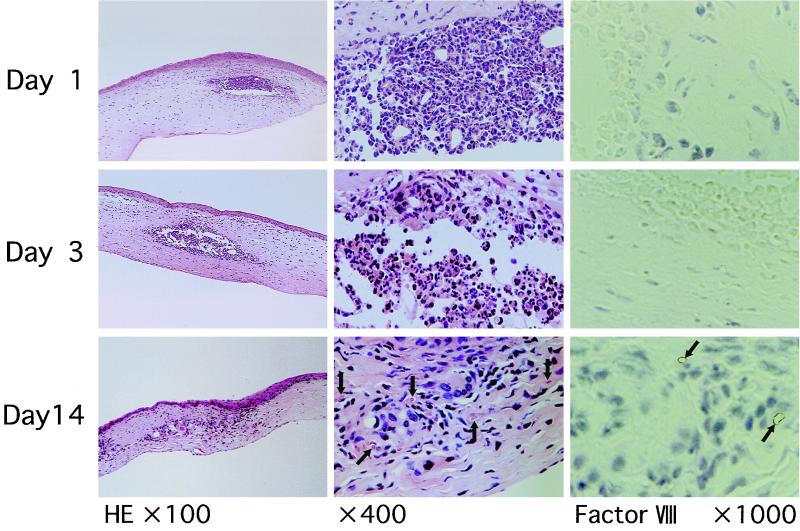

Polymorphonuclear leukocytes were infiltrated at the site of TDM challenge at doses ranging from 10 to 50 μg until day 3, indicating acute inflammatory response (Fig. 3). By contrast, mononuclear cells, such as macrophages and lymphocytes, accumulated locally 14 days after the challenge at doses ranging from 10 to 50 μg, suggesting granulomatous responses in the late stage. Simultaneously, neovascularization around granulomatous lesions, which contained red blood cells in the lumen, was detectable 14 days after the challenge at similar doses. In an immunohistochemical analysis, the new blood vessels were positive for factor VIII-related antigen, a specific marker for endothelial cells. Although LPS exhibited angiogenic activity similar to that of TDM, LPS induced marked infiltration of inflammatory cells composed primarily of polymorphonuclear neutrophils throughout the course of experiments.

FIG. 3.

Histopathology of rat corneas challenged with TDM. Histologic sections (4 μm thick) of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes infiltrated primarily at the site of TDM challenge until day 3. Focal accumulation of macrophages, including epithelioid macrophages, was evident by day 14, suggesting the development of granulomas. Neovascularization was found around granulomas but not in the center of the lesion (indicated by arrows). In the immunohistochemical analysis, the new blood vessels were positive for factor VIII-related antigen, a specific marker for endothelial cells (arrows).

Cytokines in the lesion.

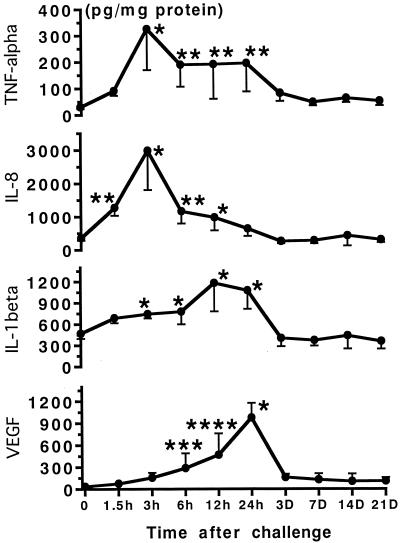

The local concentration of TNF-α increased rapidly and reached a peak (325.7 ± 63.9 pg/mg of protein) at 3 h after TDM challenge. Subsequently, TNF-α appeared to be only partially sustained during the first 24 h and declined thereafter (Fig. 4). Lesional IL-8 was found in the early stage, 3 h after the challenge (2,985.5 ± 838.7 pg/mg of protein), and then returned to the baseline level within 1 day. In contrast, both IL-1β and VEGF reached a peak at 12 to 24 h after the challenge (IL-1β; 1,156.9 ± 266.8 pg/mg of protein; VEGF, 975.1 ± 101.3 pg/mg of protein) and then returned to the baseline levels within 3 days.

FIG. 4.

Antigenic cytokine levels in corneas challenged with TDM. Local cytokine levels were measured with commercially available EIA kits. Data are means ± SD (n = 10/group). The asterisks indicate statistical significance relative to values for control rats challenged with vehicle alone (∗, P < 0.0001; ∗∗, P < 0.001; ∗∗∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗∗∗, P < 0.001).

Inhibition of corneal neovascularization by neutralizing anticytokine antibodies.

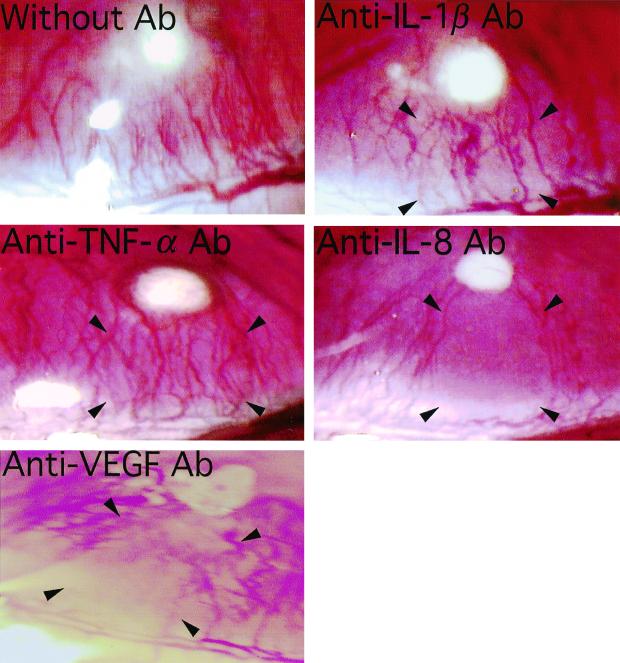

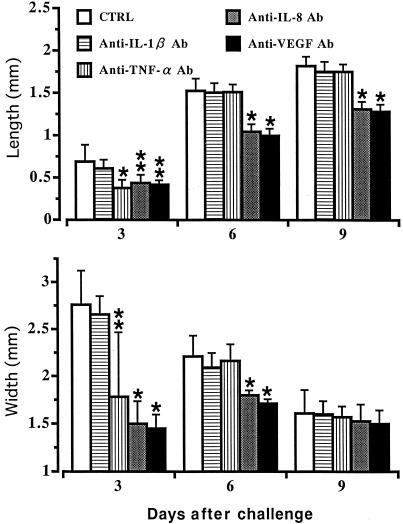

Treatment of TDM-challenged rats (50 μg) with neutralizing antibodies (10 ng) against cytokines resulted in a 66% reduction of lesional IL-1β at 12 h by anti-IL-1β antibody, a 70% decrease of TNF-α at 3 h by anti-TNF-α antibody, an 81% reduction of IL-8 at 3 h by anti-IL-8 antibody, and a 77% reduction of VEGF at 24 h by anti-VEGF antibody compared to levels in rats challenged with TDM alone. Although treatment with anti-IL-1β antibody did not inhibit neovascularization, administration of either anti-IL-8 or anti-VEGF antibody resulted in inhibition of corneal neovascularization elicited by TDM challenge (Fig. 5). Treatment with anticytokine antibodies to IL-8 and VEGF inhibited significantly both the lengths and widths of new blood vessels (Fig. 6) (P < 0.05). Administration of anti-TNF-α antibody led to a transient suppression of neovascularization. Inflammatory cell infiltration in the cornea was inhibited in TDM-challenged rats treated with either anti-IL-8 or anti-VEGF antibody compared to levels in untreated groups.

FIG. 5.

Inhibition of TDM-induced corneal neovascularization by in vivo treatment with neutralizing anti-cytokine antibodies (Ab) to IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-8, and VEGF. Administration of antibodies to IL-8 and VEGF substantially inhibited neovascularization, although antibodies to IL-1β and TNF-α did not induce significant inhibition. Antibodies were injected into the sites indicated by arrowheads. The pictures represent lesions 6 days after the treatment.

FIG. 6.

Morphometric analyses of the inhibition of TDM-induced corneal neovascularization by in vivo treatment with neutralizing anti-cytokine antibody (Ab). Data are means ± SD (n = 10/group). The asterisks indicate statistical significance relative to values for control (CTRL) rats challenged with vehicle alone (∗, P < 0.01; ∗∗, P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Our study has demonstrated that intracorneal challenge with TDM derived from M. tuberculosis can induce inflammatory responses, including granuloma formation and neovascularization. Proinflammatory cytokines and VEGF were detectable in the early stage of the process. In addition, treatment with neutralizing antibodies against IL-8 and VEGF inhibited inflammatory cell infiltration and neovascularization at the site of TDM challenge. Collectively, our results suggest that cytokines such as IL-8 and VEGF participate in both local accumulation of inflammatory cells and neovascularization, which are features of granulomatous inflammation. In this study we have used TDM of M. tuberculosis, whereas a previous study employed TDM derived from Rhodococcus sp. (38). TDM from Rhodococcus, which has a much shorter carbon chain length (C34 to C38) of mycolic acids than that from M. tuberculosis (C74 to C86), exhibited lower toxicities (38). In addition, we have used avascular corneas of rats, while the previous study (38) employed cutaneous air pouches of mice as experimental models for angiogenesis. Because IL-8, which induces angiogenesis (21) and recruitment of inflammatory cells, has been identified in rats but not in mice (3), this approach of using rats has advantages for exploring factors involved in angiogenesis and inflammation. We have also examined the angiogenic activities of MDP and LPS. In contrast to TDM, MDP from mycobacterial peptidoglycan was incapable of inducing angiogenesis. LPS from E. coli could induce angiogenesis and marked infiltration of inflammatory cells composed primarily of polymorphonuclear neutrophils, although mononuclear cells were a predominant cell type in tuberculosis- and in TDM-elicited lesions. The latter finding may also explain the histopathologic feature of inflammation induced by mycobacteria being characterized by mononuclear cell infiltration, whereas inflammation induced by E. coli is characterized by neutrophil infiltration.

Chronic inflammation is associated histologically with the presence of lymphocytes and macrophages and with the proliferation of blood vessels and connective tissue (16, 20, 22). Chronic inflammation, such as tuberculosis, is characterized by infiltration of a local accumulation of mononuclear cells, i.e., the formation of a granuloma that is surrounded by neovascularization (7, 20). It is known that mycobacterial TDM induces granulomatous inflammatory responses in mice and rats (2, 4, 20, 24), but the role of TDM in neovascularization remains unknown. In the present study, neovascularization was found 3 days after the challenge with TDM, whereas granulomas were seen 14 days after the challenge. Thus, neovascularization precedes the development of granulomas. In most tissues the presence of inflammatory macrophages results from the recruitment of peripheral blood monocytes. Their presence implies that neovascularization is required for supply and recruitment of monocytes/macrophages to the site of subsequent granuloma formation. It should be noted that neovascularization was found around granulomas but not in the center of a lesion. This finding suggests that the lesion itself is an anaerobic environment, although tubercle bacilli are aerobic. The infected host produces an environment hostile to mycobacteria to inhibit their growth. The granuloma may represent a cellular attempt to eliminate infectious agents. We could not find necrosis histopathologically in the corneal tissue challenged with TDM throughout the experimental period, although TDM induced angiogenesis and granulomatous inflammation at the site. MDP derived from M. tuberculosis could not elicit both angiogenesis and granulomatous inflammation. It seems unlikely that the inflammation induced by TDM leads to local necrosis at days 1 and 3 followed by angiogenesis on day 14. By contrast, LPS of E. coli could recruit predominantly neutrophils and induce necrosis and then neovascularization. Thus, it may be likely that tissue necrosis induced by LPS challenge, but not by TDM, results in a regeneration and angiogenesis.

In chronic inflammatory responses induced by TDM, it has been demonstrated that proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, TNF-α, and chemokines, participate in granuloma formation (20, 22). These cytokines have an ability to regulate both inflammatory responses and neovascularization (21, 30). TNF-α is produced by various cells in the inflammatory site (15) and induces angiogenic cytokines, including IL-8, VEGF, and basic fibroblast growth factor, which are involved in neovascularization (42). Although the cellular source of TNF-α in the cornea remains unknown, corneal keratocytes and epithelial cells are known to produce TNF-α (39). The indirect effects of neovascularization induced by IL-1β are mediated via other cytokines (13, 25, 37). By contrast, it is reported that IL-1β inhibits neovascularization (8). The role of IL-1β in neovascularization is controversial. We have demonstrated the transient inhibition of corneal neovascularization by anti-TNF-α antibody and the lack of angiogenic activity by IL-1β (Fig. 5 and 6). Taken together, proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and TNF-α, appear to be of little importance in neovascularization.

VEGF, produced by endothelial cells, neutrophils, and keratinocytes in response to inflammatory stimuli (12, 16), plays a key role in neovascularization (1, 29). VEGF also acts as a vascular permeability factor (12) and a monocyte chemotactic factor (6). Our results showing that treatment with anti-VEGF antibody inhibited both inflammatory cell infiltration and neovascularization suggest the involvement of VEGF in TDM-induced inflammation. It is, therefore, likely that VEGF plays a role in the development of TDM-induced chronic inflammation, including granuloma formation and neovascularization.

IL-8 is a chemotactic factor and chemokine for neutrophils and T lymphocytes (31, 34). In the cornea, it is produced by stromal and epithelial cells in response to either TNF-α or IL-1β (11). IL-8 can induce neovascularization by acting on vascular endothelial cells directly (21). In our study, corneas challenged with TDM showed an early increase of IL-8, inflammatory cell infiltration, and neovascularization, which were inhibited by in vivo treatment with anti-IL-8 antibody. This result suggests that IL-8 may participate in both neovascularization and inflammatory responses and that it may play an important role in the induction phase of chronic inflammation (18, 19). It has been reported that IL-8 has chemotactic activities for neutrophils at the early stage and for T lymphocytes at the later stage in the development of an antigen-specific, tuberculin skin reaction (23). Because TDM is the surface cell wall component of M. tuberculosis, it may be recognized initially by the immune system of the host. Thus, TDM may play an important role in the early phase of mycobacterial infection.

Mycobacteria produce biologically active substances. Among them, lipid components such as TDM possess multiple biological activities (5). In mycobacterial infection, the activity of TDM is characterized by granulomatous inflammation, including neovascularization. We have demonstrated here that mycobacterial TDM itself can induce chronic inflammation, including granuloma formation and neovascularization through cytokine-dependent mechanisms. Thus, our study provides novel evidence for the biological activity of mycobacterial TDM. This helps us to better understand the mechanism of mycobacterial disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Health and Welfare (Research on Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases, health sciences research grants) of Japan and The United States-Japan Cooperative Medical Science Program against Tuberculosis and Leprosy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amano S, Rohan R, Kuroki M, Tolentino M, Adamis A P. Requirement for vascular endothelial growth factor in wound- and inflammation-related corneal neovascularization. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asano M, Nakane A, Minagawa T. Endogenous gamma interferon is essential in granuloma formation induced by glycolipid-containing mycolic acid in mice. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2872–2878. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.2872-2878.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baggiolini M, Dewald B, Moser B. Human chemokines: an update. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:675–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bekierkunst A, Yarkoni E. Granulomatous hypersensitivity to trehalose-6,6′-dimycolate (cord factor) in mice infected with BCG. Infect Immun. 1973;7:631–638. doi: 10.1128/iai.7.4.631-638.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Besra G S, Chatterjee D. Lipids and carbohydrates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In: Bloom B R, editor. Tuberculosis: pathogenesis, protection, and control. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1994. pp. 285–306. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clauss M, Gerlach M, Gerlach H, Brett J, Wang F, Familletti P C, Pan Y C, Olander J V, Connolly D T, Stern D. Vascular permeability factor: a tumor-derived polypeptide that induces endothelial cell and monocyte procoagulant activity, and promotes monocyte migration. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1535–1545. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.6.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Courtade E T, Tsuda T, Thomas C R, Dannenberg A M. Capillary density in developing and healing tuberculous lesions produced by BCG in rabbits. A quantitative study. Am J Pathol. 1975;78:243–260. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cozzolino F, Torcia M, Aldinucci D, Ziche M, Almerigogna F, Bani D, Stern D M. Interleukin 1 is an autocrine regulator of human endothelial cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6487–6491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doenhoff M J. Granulomatous inflammation and the transmission of infection. Schistosomiasis—and TB too? Immunol Today. 1998;19:462–467. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01310-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellner J J. The immune response in human tuberculosis. Implications for tuberculosis control. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1351–1359. doi: 10.1086/514132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elner V M, Strieter R M, Pavilack M A, Elner S G, Remick D G, Danforth J M, Kunkel S L. Human corneal interleukin-8. IL-1 and TNF-induced gene expression and secretion. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:977–988. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrara N, Houck K, Jakeman L, Leung D W. Molecular and biological properties of the vascular endothelial growth factor family of proteins. Endocr Rev. 1992;13:18–32. doi: 10.1210/edrv-13-1-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gay C G, Winkles J A. Interleukin 1 regulates heparin-binding growth factor 2 gene expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:296–300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.1.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamasaki N, Isowa K I, Kamada K, Terano Y, Matsumoto T, Arakawa T, Kobayashi K, Yano I. In vivo administration of mycobacterial cord factor (trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate) can induce lung and liver granulomas and thymic atrophy in rabbits. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3704–3709. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3704-3709.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henricson B E, Benjamin W R, Vogel S N. Differential cytokine induction by doses of lipopolysaccharide and monophosphoryl lipid A that result in equivalent early endotoxin tolerance. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2429–2437. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.8.2429-2437.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson J R, Seed M P, Kircher C H, Willoughby D A, Winkler J D. The codependence of angiogenesis and chronic inflammation. FASEB J. 1997;11:457–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jain R K, Schlenger K, Hockel M, Yuan F. Quantitative angiogenesis assays: progress and problems. Nat Med. 1997;3:1203–1208. doi: 10.1038/nm1197-1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kasahara K, Sato I, Ogura K, Takeuchi H, Kobayashi K, Adachi M. Expression of chemokines and induction of rapid cell death in human blood neutrophils by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:127–137. doi: 10.1086/515585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasahara K, Tobe T, Tomita M, Mukaida N, Shao-Bu S, Matsushima K, Yoshida T, Sugihara S, Kobayashi K. Selective expression of monocyte chemotactic and activating factor/monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 in human blood monocytes by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:1238–1247. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.5.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobayashi K, Yoshida T. The immunopathogenesis of granulomatous inflammation induced by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Methods. 1996;9:204–214. doi: 10.1006/meth.1996.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koch A E, Polverini P J, Kunkel S L, Harlow L A, DiPietro L A, Elner V M, Elner S G, Strieter R M. Interleukin-8 as a macrophage-derived mediator of angiogenesis. Science. 1992;258:1798–1801. doi: 10.1126/science.1281554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunkel S L, Chensue S W, Strieter R M, Lynch J P, Remick D G. Cellular and molecular aspects of granulomatous inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1989;1:439–448. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/1.6.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larsen C G, Thomsen M K, Gesser B, Thomsen P D, Deleuran B W, Nowak J, Skødt V, Thomsen H K, Deleuran M, Thestrup-Pedersen K, Harada A, Matsushima K, T. M. The delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction is dependent on IL-8: inhibition of a tuberculin skin reaction by anti-IL-8 monoclonal antibody. J Immunol. 1995;155:2151–2157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lederer E, Adam A, Ciorbaru R, Petit J F, Wietzerbin J. Cell walls of mycobacteria and related organisms; chemistry and immunostimulant properties. Mol Cell Biochem. 1975;7:87–104. doi: 10.1007/BF01792076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J, Perrella M A, Tsai J C, Yet S F, Hsieh C M, Yoshizumi M, Patterson C, Endege W O, Zhou F, Lee M E. Induction of vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression by interleukin-1β in rat aortic smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:308–312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.1.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Logan A. Angiogenesis. Lancet. 1993;341:1467–1468. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90902-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maekura R, Nakagawa M, Nakamura Y, Hiraga T, Yamamura Y, Ito M, Ueda E, Yano S, He H, Oka S, et al. Clinical evaluation of rapid serodiagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis by ELISA with cord factor (trehalose-6,6′-dimycolate) as antigen purified from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:997–1001. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.4_Pt_1.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muthukkaruppan V, Auerbach R. Angiogenesis in the mouse cornea. Science. 1979;205:1416–1418. doi: 10.1126/science.472760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neufeld G, Cohen T, Gengrinovitch S, Poltorak Z. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors. FASEB J. 1999;13:9–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oppenheim J J, Neta R. Pathophysiological roles of cytokines in development, immunity, and inflammation. FASEB J. 1994;8:158–162. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.2.8119486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oppenheim J J, Zachariae C O C, Mukaida N, Matsushima K. Properties of the novel proinflammatory supergene “intercrine” cytokine family. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:617–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.003153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oswald I P, Dozois C M, Petit J F, Lemaire G. Interleukin-12 synthesis is a required step in trehalose dimycolate-induced activation of mouse peritoneal macrophages. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1364–1369. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1364-1369.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Otsuki Y, Kubo H, Magari S. Immunohistochemical differentiation between lymphatic vessels and blood vessels. Use of anti-basement membrane antibodies and anti-factor VIII-related antigen. Arch Histol Cytol. 1990;53(Suppl.):95–105. doi: 10.1679/aohc.53.suppl_95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ozeki Y, Kaneda K, Fujiwara N, Morimoto M, Oka S, Yano I. In vivo induction of apoptosis in the thymus by administration of mycobacterial cord factor (trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate) Infect Immun. 1997;65:1793–1799. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1793-1799.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parke A, Bhattacherjee P, Palmer R M, Lazarus N R. Characterization and quantification of copper sulfate-induced vascularization of the rabbit cornea. Am J Pathol. 1988;130:173–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perez R L, Roman J, Staton G W, Jr, Hunter R L. Extravascular coagulation and fibrinolysis in murine lung inflammation induced by the mycobacterial cord factor trehalose-6,6′-dimycolate. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:510–518. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.2.8306054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raines E W, Dower S K, Ross R. Interleukin-1 mitogenic activity for fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells is due to PDGF-AA. Science. 1989;243:393–396. doi: 10.1126/science.2783498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakaguchi I, Ikeda N, Nakayama M, Kato Y, Yano I, Kaneda K. Trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate (cord factor) enhances neovascularization through vascular endothelial growth factor production by neutrophils and macrophages. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2043–2052. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.2043-2052.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takano Y, Fukagawa K, Shimmura S, Tsubota K, Oguchi Y, Saito H. IL-4 regulates chemokine production induced by TNF-α in keratocytes and corneal epithelial cells. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:1074–1076. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.9.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yano I, Tomiyasu I, Kaneda K, Kato Y, Sumi Y, Kurano S, Sugimoto N, Sawai H. Isolation of mycolic acid-containing glycolipids in Nocardia rubra and their granuloma forming activity in mice. J Pharmacobio-Dyn. 1987;10:113–123. doi: 10.1248/bpb1978.10.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yarkoni E, Rapp H J. Granuloma formation in lungs of mice after intravenous administration of emulsified trehalose-6,6′-dimycolate (cord factor): reaction intensity depends on size distribution of the oil droplets. Infect Immun. 1977;18:552–554. doi: 10.1128/iai.18.2.552-554.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshida S, Ono M, Shono T, Izumi H, Ishibashi T, Suzuki H, Kuwano M. Involvement of interleukin-8, vascular endothelial growth factor, and basic fibroblast growth factor in tumor necrosis factor alpha-dependent angiogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4015–4023. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.4015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]