Abstract

Mice infected with Schistosoma mansoni develop Th2 cytokine-mediated granulomatous pathology that is focused on the liver and intestines. In this study, transgenic mice constitutively expressing IL-9 were infected with S. mansoni and the outcome of infection was determined. Eight weeks after infection, transgenic mice with acute infections had a moderate increase in Th2 cytokine production but were overtly normal with respect to parasite infection and pathological responses. Transgenic mice with chronic infections died 10 weeks after infection, with 86% of transgenic mice dead by week 12 of infection, compared to 7% mortality in infected wild-type mice. Stimulation of mesenteric lymph node cells from infected transgenic mice with parasite antigen elicited elevated interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-5 production and reduced gamma interferon and tumor necrosis factor alpha production compared to the responses in wild-type mice. Morbid transgenic mice had substantial enlargement of the ileum, which was associated with muscular hypertrophy, mastocytosis, eosinophilia, goblet cell hyperplasia, and increased mucin expression. We also observed that uninfected transgenic mice exhibited alterations in their intestines. Although there was hepatic mastocytosis and eosinophilia in infected transgenic mice, there was no hepatocyte damage. Death of transgenic mice expressing IL-9 during schistosome infection was primarily associated with enteropathy. This study highlights the pleiotropic in vivo activity of IL-9 and demonstrates that an elevated Th2 cytokine phenotype leads to death during murine schistosome infection.

Interleukin-9 (IL-9) is a Th2 cytokine initially described as a T-cell and mast cell growth factor (29). Studies of transgenic mice that constitutively express IL-9 have shown that a spectrum of immunological responses are potentially mediated by IL-9, including lymphomagenesis (30), intestinal mastocytosis (13), bronchial hyperresponsiveness (4, 23), pulmonary eosinophilia (4, 23), expansion of B-1 lymphocytes (38), and resistance to intestinal nematode infection (10, 11). In addition, transgenic mice with lung-specific expression of IL-9 develop airway inflammation, mast cell hyperplasia, eosinophilia, and increased airway hyperresponsiveness (37). These studies have implicated IL-9 as an important cytokine in a number of Th2 cytokine-mediated pathologies, in particular asthma.

Infection of mice with the helminth parasite Schistosoma mansoni elicits a dynamic pathological process that is associated with both Th1 and Th2 responses (5). In mice with schistosome infections, the liver and intestine are the major organs affected. The tissue damage in the liver is primarily caused by granulomatous inflammation surrounding parasite eggs trapped in hepatic parenchyma, whereas the intestine is subject to inflammation elicited by parasite eggs being translocated through the intestinal wall. In this study, a transgenic mouse strain that constitutively expresses IL-9 (30) was infected with S. mansoni to address the influence of expression of IL-9 in an in vivo Th2-mediated pathological process. Transgenic mice with chronic infections developed a marked Th2 cytokine-dominated response that was associated with high mortality and enteropathy. This study highlights the pleiotropic in vivo activity of IL-9.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and parasite.

A Puerto Rican strain of S. mansoni was used in all experiments. Treatment of mice expressing IL-9 constitutively has been described; the Tg54 transgene-positive line and wild-type FVB/N mice were used for all experiments (30). Mice were maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions.

Parasitological and pathological techniques.

Infection and portal perfusions were done as described previously (34). The livers and intestines were removed, stored at −20°C, and used for tissue homogenates (see below) or tissue egg counts. Tissues were digested in 4% KOH, and eggs were counted as described previously (2). Fecal samples were collected on the day the mice were terminated and eggs were counted (2). In accordance with United Kingdom Home Office regulations, any infected mice that became morbid were humanely killed. Analysis of pathology was performed as described in previous studies (6, 7). Liver and ileums were fixed in Formal-saline or Carnoy's fixative. Three 4-μm-thick sections of liver or 10 to 15 sections of intestine were cut at 150-μm intervals. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (granuloma measurements), toluidine blue (mast cells), Martius scarlet blue (collagen), periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) (goblet cells), and Giemsa (eosinophils) stain. The diameter of the muscularis propria (serosa to submucosa) was measured at eight different angles on transverse sections of ileum with an ocular micrometer. The mean diameter of the muscularis propria in individual mice was calculated from measurements on at least 10 sections. All pathological parameters were assayed in a double-blind manner.

Cytokine analysis.

Spleen or mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) were aseptically removed and cultured in vitro, and cytokine was assayed in culture supernatant as described previously (6, 8). Cells were restimulated in vitro with soluble egg antigens (20 μg/ml). Anti-cytokine monoclonal antibodies and recombinant cytokine standards to detect IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, gamma interferon (IFN-γ), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) were purchased from PharMingen (San Diego, Calif.) or Genzyme (Kent, United Kingdom).

Preparation of tissue homogenates.

Liver or intestine tissue was weighed and chopped with scissors. Tissue was processed for eosinophil peroxidase (EPO) assays essentially as described previously (1). In brief, approximately 5% (wt/vol) tissue suspensions in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) (without phenol red, 10 mM HEPES) (pH 7.4) (Sigma, Dorset, United Kingdom) were homogenized on ice using a T8 Ultra-Turrax homogenizer (Janke and Kunkel GmbH, Staufen, Germany). The supernatant was centrifuged at 1,952 × g for 10 min (4°C). The pellet was retained, and red blood cells were lysed by hypotonic shock. Homogenization and centrifugation were repeated two more times. The cell pellet was resuspended in HBSS containing 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (HBSS-HTAB), rehomogenized, freeze-thawed three times in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −20°C until assayed. Intestinal tissue was processed for murine mast cell proteinase (mMCP) analysis as described previously (16). Chopped intestinal tissue was homogenized in 1 ml of 20 mM Tris–1 M NaCl (pH 7.5). Following centrifugation (9,000 × g for 30 min), the supernatant was stored at −20°C until assayed. Protein content was assayed in all intestinal homogenates.

mMCP-1 analysis.

Serum or intestinal homogenates were assayed for mMCP-1 activity using an antibody capture ELISA (26). The assay was performed with a commercial kit following the manufacturer's instructions (Moredun Scientific Ltd., Midlothian, Scotland).

EPO assay for tissue eosinophilia.

Tissue eosinophilia was determined using the EPO assay (35) as described previously (1). Intestine or liver tissue was processed as described above. The numbers of eosinophils (expressed as 106 or 107 cells per gram of tissue) were interpolated from a standard curve prepared from murine eosinophils. Blood from Nippostrongylus brasiliensis-infected mice (10 to 20% of circulating leukocytes were eosinophils) were used as a source of eosinophils. Murine eosinophils were isolated from mouse blood as described previously (36). In brief, eosinophils were purified from blood by dextran T-500 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden) sedimentation. Red blood cells were removed from the leukocyte-rich supernatant, and following washing, eosinophils were counted on eosin-stained cytospins. Eosinophils were adjusted to a stock dilution of 106 eosinophils per ml in HBSS-HTAB, freeze-thawed, and stored at −20°C.

Intestinal mucin detection.

Mucous expression was analyzed by Western blots of intestinal homogenates (prepared as described for EPO assays) using a monoclonal antibody against human colonic mucin (R35.3.3) as described previously (17, 27). Protein level estimation was performed on supernatants from the homogenates of intestines from individual mice. Supernatants were resolved on a 4 to 12% polyacrylamide gel under nonreducing conditions; 50 μg of protein was loaded per lane. Gels were stained with silver to ensure equal protein loading in wells. Following electrotransfer to nitrocellulose paper, strips were probed with R35.3.3. Mucin was detected at 79 kDa, and relative expression of this band was performed using Kodak Digital Science 1D Image Analysis Software (Rochester, N.Y.).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical differences between the values for different groups were determined by Student's t test. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

IL-9 production during S. mansoni infection of mice.

During infection of mice with S. mansoni, there are dynamic temporal changes in the relative production of Th1 and Th2 cytokines (5). Characteristically, during the first 4 weeks of infection, there is an early Th1 cytokine response that is then superseded by a marked Th2 cytokine phenotype (14, 28). The Th2 cytokine response peaks approximately 8 weeks after infection, after which there is a progressive decline in Th2 cytokine production. To date, there have not been extensive studies on the role of IL-9 in schistosome infection. Following polyclonal (mitogen) stimulation of spleen cells recovered from infected mice at various stages of infection, we observed that IL-9 production followed the general temporal pattern of Th2 cytokine production during schistosome infection (data not shown). The increased production of IL-9 during the first 8 weeks of murine schistosome infection is consistent with the results of a previous study (18). However, while we observed reduced IL-9 production from weeks 8 to 16 after infection, these researchers observed a plateauing or marginal reduction in IL-9 production from weeks 8 to 14 after infection. These data demonstrate that IL-9 production is elevated in the Th2 cytokine-dominated acute stages of schistosome infection of mice and is reduced in the chronic stages of infection.

Increased Th2 cytokine responses in an acute S. mansoni infection of transgenic mice that constitutively express IL-9.

Transgenic and wild-type mice were exposed to an acute (150-cercaria) schistosome infection to determine if expression of IL-9 altered the induction of Th2 cytokines or modified the course of infection. Mice were killed 8 weeks after infection, coincident with the peak in Th2 cytokine responses in mice. No deaths or differences in overt morbidity were observed for the groups. Parasitologically, expression of IL-9 did not influence parasite infectivity (number of worms recovered) or fecundity (egg production per worm pair) (Table 1). Infected wild-type and transgenic mice had similar-sized granulomas surrounding eggs in the liver and had comparable levels of hepatic fibrosis (Table 2). There was, however, a slight increase in the numbers of eosinophils within the egg granulomas in the livers of transgenic mice over those of wild-type mice (Table 2). Measurement of the levels of aspartate aminotransferase, a marker for hepatocyte damage, in plasma demonstrated that the infected transgenic mice and wild-type mice had comparable levels of hepatic damage (Table 2). There was no major difference in intestinal pathology in the infected wild-type and transgenic mice, with the exception of an increase in the size of the ileum of two of the eight transgenic mice. Both groups of mice had comparable levels of excretion of parasite eggs in the feces (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Parasitological data obtained from wild-type and IL-9-expressing transgenic mice with acute or chronic S. mansoni infectionsa

| Infection and group | Infectivity (no. of worm pairs) | Fecundity (103 eggs per worm pair) | No. of eggs in tissue (103/g)

|

No. of eggs excreted into feces | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | Intestine | ||||

| Acute | |||||

| Wild-type | 11.3 ± 5.1 | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 9.6 ± 3.5 | 14.7 ± 6.4 | 530 ± 280 |

| Transgenic | 10.5 ± 2.8 | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 9.1 ± 3.3 | 14.3 ± 4.7 | 625 ± 377 |

| Chronic | |||||

| Wild-type | 2.3 ± 1.3 | 5.3 ± 2.7 | 4.8 ± 1.7 | 7.4 ± 2.3 | 143 ± 157 |

| Transgenic | 2.1 ± 1.4 | 6.1 ± 3.1 | 4.7 ± 1.5 | 8.1 ± 4.0 | 185 ± 140 |

Parasitological data were obtained from wild-type mice and transgenic mice that constitutively expressed IL-9. Both sets of mice were exposed to acute (150-cercaria) or chronic (25-cercaria) S. mansoni infections. Data are from eight acutely and five chronically infected mice that were killed on days 56 and 72 after infection, respectively. Data are presented as means ± standard deviations and are representative of two separate experiments.

TABLE 2.

Hepatic alterations in wild-type and IL-9-expressing transgenic mice with received acute or chronic S. mansoni infectionsa

| Infection and group | Granuloma diam (μm) | Fibrosis (μg of collagen/mg) | Eosinophiliab

|

Mastocytosisc | Hepatocyte damaged (AST SFU/ml) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Granuloma (%) | No. of eosinophils (107/g) | |||||

| Acute | ||||||

| Wild-type | 305 ± 20 | 8.5 ± 1.9 | 47 ± 11 | NDe | ND | 349 ± 64 |

| Transgenic | 311 ± 44 | 9.1 ± 2.6 | 51 ± 9 | ND | ND | 360 ± 59 |

| Chronic | ||||||

| Wild-type | 274 ± 23 | 14.1 ± 3.4 | 34 ± 18 | 21.6 ± 4.5 | 3.4 ± 2.3 | 245 ± 28 |

| Transgenic | 250 ± 35 | 12.3 ± 2.5 | 64 ± 27f | 41.3 ± 11.7f | 9.1 ± 3.4f | 210 ± 37 |

Hepatic alterations in wild-type mice and transgenic mice that constitutively expressed IL-9. Both sets of mice were exposed to acute (150-cercaria) or chronic (25-cercaria) S. mansoni infections. Data are from eight acutely and five chronically infected mice that were killed on days 56 and 72 after infection, respectively. Data are presented as means ± standard deviations and are representative of two separate experiments.

Hepatic eosinophilia is presented as a percentage of eosinophils within the granuloma and as the number of eosinophils per gram of protein.

Mastocytosis was determined by measurement of mMCP-1 activity in liver homogenates and is presented as milligram of protease activity per gram of protein.

Hepatocyte damage was quantified by assay for plasma aspartate aminotransferase (AST) activity.

ND, not determined.

Significantly greater in transgenic mice than in wild-type mice (P < 0.01 by Student's t test).

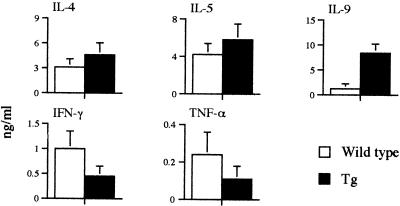

MLN cells recovered from infected mice were restimulated with parasite egg antigens. MLN cells from infected transgenic mice had significant greater production of IL-9 after restimulation with egg antigens relative to IL-9 release from cells from infected wild-type mice (Fig. 1A). Infected transgenic mice had a nonsignificant increase in production of Th2 cytokines (IL-4 and IL-5) and reduced Th1 cytokine (IFN-γ and TNF-α) responses compared to those of wild-type mice (Fig. 1A). ELISAs for the levels of parasite antigen-specific antibody in serum demonstrated there were elevated immunoglobulin E (IgE) and IgG1 responses in the transgenic mice than in the infected wild-type mice (data not shown). Collectively, the data indicate that the expression of IL-9 during an 8-week acute schistosome infection caused a moderate increase in the production of Th2 cytokines but did not cause any major parasitological or pathological alterations.

FIG. 1.

Th1 and Th2 cytokine profiles in wild-type mice and transgenic (Tg) mice that constitutively express IL-9 (Tg) with acute S. mansoni infections. Mice were terminated on day 58 after infection. MLN from two to four mice were pooled and stimulated with parasite egg antigens (20 μg/ml). Data presented are means ± standard deviations from three cultures.

Th2 cytokine-dominated responses and high mortality during chronic schistosome infection of transgenic mice that constitutively express IL-9.

In mice with chronic schistosome infections, the production of IL-9 and other Th2 cytokines is down modulated from approximately 8 to 12 weeks after infection. To determine whether the expression of IL-9 influenced the ability of mice to down modulate Th2 cytokine responses, transgenic mice were infected with a light (25-cercaria) chronic infection. Unexpectedly, for mice with chronic infections, there was high mortality of transgenic mice, with transgenic animals dying from day 74 after infection (Fig. 2). By 83 days after infection, 86% (12 of 14 mice infected) of the transgenic mice had died, whereas 7% (1 of 15 mice infected) of wild-type mice had succumbed. This IL-9-expressing transgenic mouse strain is predisposed to develop thymic lymphomas from 3 to 9 months of age (31). We therefore checked if death of transgenic mice was associated with thymus enlargement. No infected transgenic mice had evidence of alterations in thymus size. As uninfected transgenic mice of the same age that were housed in the same room as that of infected mice did not die, we attribute the deaths of the transgenic mice to schistosome infection.

FIG. 2.

Survival of mice with chronic S. mansoni infections. The mortality for IL-9-expressing transgenic (Tg) mice was much higher than that of the wild-type (Wt) mice.

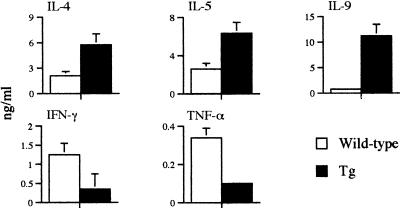

In a second chronic infection, mice were terminated on day 72 after infection when the infected transgenic mice had started to develop morbidity. There were no parasitological differences between schistosome-infected transgenic and wild-type mice (Table 1). Cells from the MLN were restimulated with egg antigens, and cytokine production was measured by ELISA. Infected transgenic mice had a marked elevation in the production of IL-4 and IL-5 relative to wild-type mice and a reciprocal reduced production of IFN-γ and TNF-α (Fig. 3). Other Th2 cytokines (IL-10 and IL-13) were also elevated in the infected transgenic mice than in the wild-type mice. Transgenic mice also had increased levels of parasite antigen-specific IgE (data not shown). With respect to the induction of cytokine production following a chronic schistosome infection, the transgenic mice have a Th2 cytokine-dominated response relative to wild-type mice. It has been previously observed that Th2 cytokine responses are required in schistosome infection to prevent exacerbated Th1 responses evoking pathology (5, 7, 33). The data presented here illustrate that a Th2-polarized cytokine response can lead to death during chronic schistosome infection of mice. In agreement with this observation, a recent study has also demonstrated that a Th2 cytokine-dominated response causes lethal pathology during murine schistosome infection (15).

FIG. 3.

Th1 and Th2 cytokine profiles in wild-type and IL-9-expressing transgenic (Tg) mice with chronic S. mansoni infections. Mice were terminated on day 72 after infection. MLN from two to four mice were pooled and stimulated with parasite egg antigens (20 μg/ml). Data presented are means ± standard deviations from three cultures.

Enteropathy in infected transgenic mice.

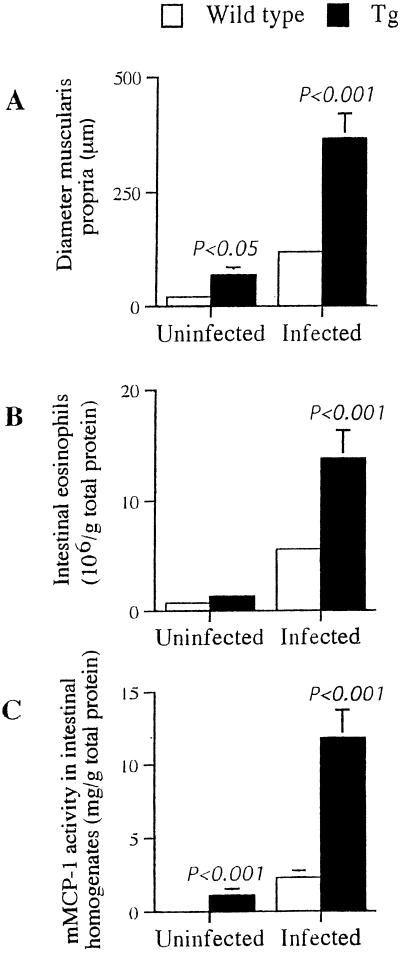

Gross examination during autopsy of chronically infected mice demonstrated marked distension of the small intestines of all infected mice relative to those of uninfected mice (Fig. 4A). There was striking enlargement of the ileums of all infected transgenic mice compared to infected wild-type animals, with the size of the ileum in transgenic mice that had overt morbidity at termination being increased three- to sixfold (Fig. 4A). The enlargement in size of the intestine of infected transgenic mice was not associated with alterations in the submucosa or serosa but was due to a profound increase in the size of the muscularis propria (Fig. 4B). Measurements of the diameter of the muscularis propria demonstrated the significant (P < 0.001) increase in its size in the infected transgenic mice over that of infected wild-type mice (Fig. 5A). The intestinal enlargement observed in wild-type mice is comparable to a previous study in schistosome-infected mice (3), and similar intestinal changes have been observed during infection of other animals (9, 20). It was also observed that uninfected transgenic mice had enlarged small intestines relative to the size of the intestines in wild-type mice (Fig. 4A), with a significant (P < 0.05) increase in the diameter of the muscularis propria (Fig. 5A). However, the intestinal enlargement in uninfected transgenic mice was extremely variable between individual mice, with approximately 50% of transgenic mice having intestines of comparable size to those of wild-type mice.

FIG. 4.

Intestinal and hepatic alterations in IL-9-expressing transgenic (Tg) and wild-type (Wt) mice. (A) Uninfected (−) or chronically infected (+) Tg mice had a marked increase in the size of the ileum relative to that of uninfected or infected wild-type mice (hematoxylin and eosin stained). (B) Intestinal enlargement in the infected Tg mice was associated with marked distension of the muscularis propria compared to that of infected wild-type mice (hematoxylin and eosin stained). Bar, 45 μm. (C and D) Within the muscularis propria of infected Tg mice, there was marked infiltration of mast cells (C) and eosinophils (D). Toluidine blue (C) and hematoxylin and eosin (D) stain was used. Bars, 40 μm (C) and 50 μm (D). There was marked goblet cell hyperplasia in the ileums of Tg mice (PAS stained). Bar, 30 μm. (F) In the livers of infected Tg mice, there was a pronounced infiltration of eosinophils within the granuloma surrounding the egg compared to wild-type mice (hematoxylin and eosin stained). Bar, 30 μm.

FIG. 5.

Enteropathy in uninfected and chronically infected IL-9-expressing transgenic (Tg) mice. (A) The diameter of the muscularis propria was measured on histological sections with an ocular micrometer. (B and C) To quantify the extent of eosinophilia and mastocytosis in the ileums of mice, tissue homogenates were assayed for EPO (B) and mMCP-1 activity (C). Results are from 4 to 12 mice per group, and data are presented as means ± standard errors. Statistical differences between groups were determined by Student's t test.

Histological analysis demonstrated that the increase in the size of the muscularis propria of infected transgenic mice was due to muscular hypertrophy (Fig. 4B) and infiltration of mast cells (Fig. 4C) and eosinophils (Fig. 4D). In the infected transgenic mice, eosinophils were detected within the egg granuloma and throughout the muscularis propria (Fig. 4D), whereas in infected wild-type mice, eosinophils were primarily associated with the granuloma surrounding the egg (not shown). To quantify the levels of intestinal eosinophilia, we measured EPO activity in tissue homogenates. Uninfected transgenic mice had slightly elevated numbers of intestinal eosinophils than wild-type mice (Fig. 5B). Schistosome infection elicited a marked intestinal eosinophilia in both wild-type and transgenic mice, with infected transgenic mice having two- to threefold-more intestinal eosinophils than infected wild-type mice (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4B). Infiltration of the intestine by eosinophils is a normal process during schistosome infection of mice, with eosinophils within the intestine proposed to reduce intestinal inflammation (5) and aid the translocation of the egg through the intestinal wall (19). However, IL-9-expressing transgenic mice and wild-type mice with acute or chronic schistosome infections had comparable numbers of eggs excreted, even though the transgenic mice had intestinal eosinophilia (Table 1).

Intestinal mastocytosis during schistosome infection of mice has been reported previously, with increased intraepithelial intestinal mast cells and intestinal mast cell protease (mMCP-1) activity in infected mice (24). Initially, as performed previously in the same mouse strain following gastrointestinal nematode challenge (10, 11), we counted the numbers of intraepithelial mast cells on toluidine blue-stained sections of intestine. However, as we had observed marked mast cell infiltration of the muscularis propria (Fig. 4C), we measured the levels of mMCP-1 in intestinal homogenates to quantify total intestinal mast cells. In intestinal homogenates of uninfected wild-type mice, there was limited mMCP-1 activity but significantly elevated protease activity in transgenic mice (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5C). The mastocytosis induced during schistosome infection was reflected in elevated mMCP-1 activity in infected wild-type mice and fourfold-greater protease activity in infected transgenic mice (Fig. 5C). The intestinal mastocytosis in uninfected IL-9-expressing transgenic mice has been reported previously (11, 13). Our data on elevated intestinal mast cells and mMCP-1 activity in schistosome-infected transgenic mice is consistent with previous studies in the same mouse strain following challenge with gastrointestinal nematodes (10, 11).

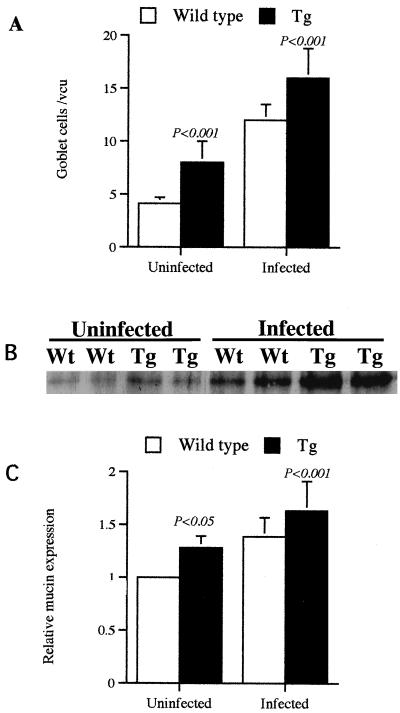

PAS-stained sections of ileum demonstrated marked goblet cell hyperplasia in the infected transgenic mice (Fig. 5E). Numeration of PAS-positive goblet cells per villous crypt unit demonstrated the elevation in goblet cells in the transgenic mice, with naive transgenic mice having approximately twice the numbers of goblet cells as wild-type mice (Fig. 6A). To more accurately analyze intestinal mucous expression in individual animals, a monoclonal anti-human colonic mucin (R35.3.3) antibody was used to detect mucin in Western blots of intestinal homogenates (17, 27). Using this method, the relative expression of mucin, a band at 79 kDa, in different animals was evident (Fig. 6B). Densitometry was used to quantify intestinal mucin expression in individual mice (Fig. 6C). There was greater intestinal expression of mucin in uninfected transgenic mice than in wild-type mice (P < 0.05). Schistosome infection elicited an increase in intestinal mucin expression (P < 0.001) in both wild-type and transgenic animals compared to that in uninfected mice (Fig. 6B and C). Mucin expression was significantly greater in infected transgenic mice than wild-type mice. The observation that IL-9 may elicit mucin expression in this study is in agreement with recent studies that demonstrate this cytokine may directly stimulate mucin production (21, 22).

FIG. 6.

Goblet cell hyperplasia and mucin expression in transgenic (Tg) mice that constitutively express IL-9. (A) The numbers of goblet cells per villous crypt unit (vcu) were counted on PAS-stained ileum sections from uninfected or infected Tg and wild-type mice. (B and C). Mucin expression in the ileum was determined by Western blotting of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis-resolved ileum homogenates using an anti-mucin monoclonal antibody. (B) A representative Western blot showing mucin expression (79 kDa) in uninfected and infected wild-type (Wt) and transgenic (Tg) mice is shown. Densitometry of the intensities of the mucin band on a series of Western blots was used to quantify the levels of mucin expression in groups of mice. (C) Data are presented as the increase in mucin expression in different groups of mice relative to the mucin levels in uninfected wild-type mice, which was set at 1. Data are from 3 to 10 mice per group and are presented as means ± standard errors. Statistical differences between groups were determined by Student's t test.

With respect to the livers of chronically infected animals, there was no difference between transgenic and wild-type mice with respect to the size of the granuloma or the degree of hepatic fibrosis (Table 2). However, there was a striking predominance of eosinophils within the granuloma of infected transgenic mice relative to that in wild-type mice (Fig. 4E). We also detected sporadic eosinophil infiltrates throughout the hepatic parenchyma and surrounding portal tracts of the infected transgenic mice (not shown). Assays for EPO activity in hepatic tissue confirmed there was two- to threefold more eosinophils within the livers of chronically infected transgenic mice than in infected wild-type animals (Table 2). On toluidine blue-stained liver sections, there was increased mast cells in transgenic mice, with assays for mMCP-1 activity on liver homogenates demonstrating significant mastocytosis in the infected transgenic mice relative to wild-type mice (Table 2). The marked eosinophil infiltration of the livers of infected transgenic mice is potentially significant, as eosinophils have been causally associated with a number of liver diseases (25).

With respect to murine schistosomiasis, it has been suggested that various mediators that are released by degranulation of eosinophils may stimulate hepatic damage in schistosome-infected mice (12). However, despite the increased hepatic eosinophilia and mastocytosis in the infected transgenic mice, these mice and wild-type mice had comparable plasma transaminase levels (Table 2), implying there was no increase in hepatocyte damage.

In conclusion, infection of mice expressing IL-9 with a helminth infection that elicits elevated Th2 cytokine caused fatalities in transgenic mice. A range of Th2 cytokine-mediated responses that are elicited in wild-type mice during schistosome infection were exacerbated in IL-9-expressing transgenic mice including the following: (i) a marked elevation in Th2 cytokine production and reduction in Th1 production, (ii) increased tissue (intestine and liver) eosinophilia and mastocytosis, and (iii) intestinal goblet cell hyperplasia and mucin expression. In addition, transgenic mice had marked hypertrophy of the muscularis in the intestine, implicating a potential effect of IL-9 on smooth muscle. In contrast, a number of other responses were not affected, including parasite infectivity or fecundity and egg excretion. We cannot attribute the various responses that we have observed in schistosome-infected IL-9-expressing transgenic mice as solely due to IL-9, since expression of IL-9 elicited a marked elevation in Th2 cytokine production following infection. However, certain Th2 cytokine-mediated responses (hepatic granuloma formation and fibrosis) were not affected by expression of IL-9. With respect to the elevated mucin expression in transgenic mice, there is emerging evidence that IL-9 may have a direct role in this response; e.g., IL-9 has been shown to directly induce mucin production in respiratory epithelial cells (21), and the IL-9-expressing transgenic mouse strain used in this study has been shown to have elevated mucin expression in the lung (22). Similarly, tissue eosinophilia and mastocytosis have been reported in previous studies in IL-9-expressing transgenic mice (4, 37), and with respect to eosinophilia, in vivo neutralization of IL-9 activity by antibody treatment blocks parasite-induced blood eosinophilia (32). The data presented in this study enlarge the spectrum of responses elicited in mice that constitutively express IL-9. This study illustrates the pleiotropic activities of IL-9 and its potential role in Th2 cytokine-mediated pathologies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Fiona Culley for advice on eosinophil peroxidase assays, Hugh Miller and Elisabeth Thornton for assistance with mMCP-1 assays, and Daniel Podolsky for kindly providing the anti-mucin monoclonal antibody. We are grateful to Barry Potter for performing histology.

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust. P.G.F. is supported by a Wellcome Trust Career Development Award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Das A M, Williams T J, Lobb R, Nourshargh S. Lung eosinophilia is dependent on IL-5 and the adhesion molecules CD18 and VLA-4, in a guinea-pig model. Immunology. 1995;84:41–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doenhoff M, Musallam R, Bain J, McGregor A. Schistosoma mansoni infections in T-cell deprived mice, and the ameliorating effect of administering homologous chronic infection serum. I. Pathogenesis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1979;28:260–273. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1979.28.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domingo E O, Warren K S. Pathology and pathophysiology of the small intestine in murine schistosomiasis mansoni, including a review of the literature. Gastroenterology. 1969;56:231–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dong Q, Louahed J, Vink A, Sullivan C D, Messler C J, Zhou Y, Haczku A, Huaux F, Arras M, Holroyd K J, Renauld J C, Levitt R C, Nicolaides N C. IL-9 induces chemokine expression in lung epithelial cells and baseline airway eosinophilia in transgenic mice. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:2130–2139. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199907)29:07<2130::AID-IMMU2130>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fallon P G. Immunopathology of schistosomiasis: a cautionary tale of mice and men. Immunol Today. 2000;21:29–34. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01551-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fallon P G, Dunne D W. Tolerization of mice to Schistosoma mansoni egg antigens causes elevated type 1 and diminished type 2 cytokine responses and increased mortality in acute infection. J Immunol. 1999;162:4122–4132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fallon P G, Richardson E J, McKenzie G J, McKenzie A N. Schistosome infection of transgenic mice defines distinct and contrasting pathogenic roles for IL-4 and IL-13: IL-13 is a profibrotic agent. J Immunol. 2000;164:2585–2591. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fallon P G, Smith P, Dunne D W. Type 1 and type 2 cytokine-producing mouse CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in acute Schistosoma mansoni infection. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1408–1416. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199804)28:04<1408::AID-IMMU1408>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farah I O, Nyindo M. Acute schistosomiasis mansoni in the baboon Papio anubis gives rise to goblet-cell hyperplasia and villus atrophy that are modulated by an irradiated cercarial vaccine. Parasitol Res. 1997;83:281–284. doi: 10.1007/s004360050247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faulkner H, Humphreys N, Renauld J C, Van Snick J, Grencis R. Interleukin-9 is involved in host protective immunity to intestinal nematode infection. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2536–2540. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faulkner H, Renauld J C, Van Snick J, Grencis R K. Interleukin-9 enhances resistance to the intestinal nematode Trichuris muris. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3832–3840. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3832-3840.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gharib B, Abdallahi O M, Dessein H, De Reggi M. Development of eosinophil peroxidase activity and concomitant alteration of the antioxidant defenses in the liver of mice infected with Schistosoma mansoni. J Hepatol. 1999;30:594–602. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80189-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Godfraind C, Louahed J, Faulkner H, Vink A, Warnier G, Grencis R, Renauld J C. Intraepithelial infiltration by mast cells with both connective tissue-type and mucosal-type characteristics in gut, trachea, and kidneys of IL-9 transgenic mice. J Immunol. 1998;160:3989–3996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grzych J M, Pearce E, Cheever A, Caulada Z A, Caspar P, Heiny S, Lewis F, Sher A. Egg deposition is the major stimulus for the production of Th2 cytokines in murine schistosomiasis mansoni. J Immunol. 1991;146:1322–1327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffmann K F, Cheever A W, Wynn T A. IL-10 and the dangers of immune polarization: excessive type 1 and type 2 cytokine responses induce distinct forms of lethal immunopathology in murine schistosomiasis. J Immunol. 2000;164:6406–6416. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huntley J F, Gooden C, Newlands G F, Mackellar A, Lammas D A, Wakelin D, Tuohy M, Woodbury R G, Miller H R. Distribution of intestinal mast cell proteinase in blood and tissues of normal and Trichinella-infected mice. Parasite Immunol. 1990;12:85–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1990.tb00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Itoh H, Beck P L, Inoue N, Xavier R, Podolsky D K. A paradoxical reduction in susceptibility to colonic injury upon targeted transgenic ablation of goblet cells. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1539–1547. doi: 10.1172/JCI6211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khalil R M A, Luz A, Mailhammer R, Moeller J, Mohamed A A, Omran S, Dörmer P, Hültner L. Schistosoma mansoni infection in mice augments the capacity for interleukin 3 (IL-3) and IL-9 production and concurrently enlarges progenitor pools for mast cells and granulocytes-macrophages. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4960–4966. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.4960-4966.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lenzi H L, Lenzi J A, Sobral A C. Eosinophils favor the passage of eggs to the intestinal lumen in schistosomiasis. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1987;20:433–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindberg R, Johansen M V, Monrad J, Christensen N O, Nansen P. Experimental Schistosoma bovis infection in goats: the inflammatory response in the small intestine and liver in various phases of infection and reinfection. J Parasitol. 1997;83:454–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Longphre M, Li D, Gallup M, Drori E, Ordonez C L, Redman T, Wenzel S, Bice D E, Fahy J V, Basbaum C. Allergen-induced IL-9 directly stimulates mucin transcription in respiratory epithelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1375–1382. doi: 10.1172/JCI6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Louahed J, Toda M, Jen J, Hamid Q, Renauld J-C, Levitt R C, Nicolaides N C. Interleukin-9 upregulates mucus expression in the airways. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;22:649–656. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.22.6.3927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLane M P, Haczku A, van de Rijn M, Weiss C, Ferrante V, MacDonald D, Renauld J C, Nicolaides N C, Holroyd K J, Levitt R C. Interleukin-9 promotes allergen-induced eosinophilic inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in transgenic mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;19:713–720. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.19.5.3457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller H R, Newlands G F, McKellar A, Inglis L, Coulson P S, Wilson R A. Hepatic recruitment of mast cells occurs in rats but not mice infected with Schistosoma mansoni. Parasite Immunol. 1994;16:145–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1994.tb00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neuberger J. Eosinophils and primary biliary cirrhosis—stoking the fire? Hepatology. 1999;30:335–337. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newlands G F, Knox D P, Pirie-Shepherd S R, Miller H R. Biochemical and immunological characterization of multiple glycoforms of mouse mast cell protease 1: comparison with an isolated murine serosal mast cell protease (MMCP-4) Biochem J. 1993;294:127–135. doi: 10.1042/bj2940127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogata H, Podolsky D K. Trefoil peptide expression and secretion is regulated by neuropeptides and acetylcholine. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:G348–G354. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.2.G348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pearce E J, Caspar P, Grzych J M, Lewis F A, Sher A. Downregulation of Th1 cytokine production accompanies induction of Th2 responses by a parasitic helminth, Schistosoma mansoni. J Exp Med. 1991;173:159–166. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.1.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Renauld J C, Kermouni A, Vink A, Louahed J, Van Snick J. Interleukin-9 and its receptor: involvement in mast cell differentiation and T cell oncogenesis. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;57:353–360. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Renauld J C, van der Lugt N, Vink A, van Roon M, Godfraind C, Warnier G, Merz H, Feller A, Berns A, Van Snick J. Thymic lymphomas in interleukin 9 transgenic mice. Oncogene. 1994;9:1327–1332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Renauld J C, Vink A, Louahed J, Van Snick J. Interleukin-9 is a major anti-apoptotic factor for thymic lymphomas. Blood. 1995;85:1300–1305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richard M, Grencis R K, Humphreys N E, Renauld J C, Van Snick J. Anti-IL-9 vaccination prevents worm expulsion and blood eosinophilia in Trichuris muris-infected mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:767–772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosa Brunet L, Finkelman F D, Cheever A W, Kopf M A, Pearce E J. IL-4 protects against TNF-alpha-mediated cachexia and death during acute schistosomiasis. J Immunol. 1997;159:777–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smithers S R, Terry R J. The infection of laboratory hosts with cercariae of Schistosoma mansoni and the recovery of the adult worms. Parasitology. 1965;55:695–700. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000086248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strath M, Warren D J, Sanderson C J. Detection of eosinophils using an eosinophil peroxidase assay. Its use as an assay for eosinophil differentiation factors. J Immunol Methods. 1985;83:209–215. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(85)90242-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teixeira M M, Wells T N, Lukacs N W, Proudfoot A E, Kunkel S L, Williams T J, Hellewell P G. Chemokine-induced eosinophil recruitment. Evidence of a role for endogenous eotaxin in an in vivo allergy model in mouse skin. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1657–1666. doi: 10.1172/JCI119690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Temann U A, Geba G P, Rankin J A, Flavell R A. Expression of interleukin 9 in the lungs of transgenic mice causes airway inflammation, mast cell hyperplasia, and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1307–1320. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.7.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vink A, Warnier G, Brombacher F, Renauld J C. Interleukin 9-induced in vivo expansion of the B-1 lymphocyte population. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1413–1423. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.9.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]