Abstract

The current study examined the effects of specific COVID-19 stressors (i.e., family member’s death due to COVID-19, COVID-19 infection, and school/financial stressors) on stress, anxiety, and depression and the potential buffering roles of resilience and perceived social support in the association between COVID-19 stressors and psychological symptoms in a Hispanic university student sample (n = 664). Participants were classified in three stressor groups: those reporting a family member’s death due to COVID-19 (15.7%), those reporting their own or a family member’s COVID-19 infection but no COVID-19 death (35.5%), and those reporting only school and/or financial stressors due to the pandemic (48.8%). Participants completed self-report measures online. Over 50% of participants with a COVID-19 death or infection in the family reported clinical levels of depression symptoms and over 40% endorsed clinically elevated anxiety symptoms. A series of moderation analyses with multi-categorical predictors found that among relatively highly resilient people, the magnitudes of the impact of COVID-19 infection or death on stress, anxiety, and depression were similar to the effect of a financial/school stressor alone, suggesting the buffering role of resilience. Perceived social support did not play a buffering role in the associations. Family member death due to COVID-19 and COVID-19 infection had significant negative psychological impacts on Hispanic young adults. Internal personal resources such as resilience, rather than external personal resources such as perceived social support, appear to be a critical factor that may help protect Hispanic individuals’ mental health from the worst stressors of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, Stress, Anxiety, Depression, Resilience, Perceived social support, Hispanics

Since its emergence in 2019, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become a major public health crisis globally. The sweeping illness, death, and the broader disruption of the pandemic led to wide-scale mental health struggles, as suggested by high prevalence rates of stress, anxiety, and depression. National and international meta-analytic and review studies reported that over 25% of the reviewed samples had elevated depression, anxiety, and stress (Chang et al., 2021; Jehi et al., 2022; Santabárbara et al., 2021; Xiong et al., 2020). Younger adults and students were particularly at risk for developing psychological symptoms in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Cunningham et al., 2021; Santabárbara et al., 2021; Xiong et al., 2020). In the United States (US), younger individuals were found to have more severe depression and anxiety than older people (Cunningham et al., 2021).

In the US, pre-existing ethnic and racial inequalities in healthcare access and quality, socioeconomic standing, and frontline work have distributed the pandemic’s impacts unequally (Aucejo et al., 2020; Montenovo et al., 2021). Hispanic individuals have been severely affected by the pandemic, based on data showing that while Hispanics constitute 18.5% of the US population, they accounted for 24.3% of COVID-19 cases (CDC, 2022). Hispanic individuals also appear at risk for experiencing severe psychological impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic compared to other ethnic groups (e.g., French et al., 2020; Rudenstine et al., 2021). According to Rudenstine et al. (2021) Hispanics showed higher prevalence of clinically significant levels of depressive symptoms in response to the pandemic than non-Hispanics. Other studies estimate commensurate, but nonetheless worrisome, elevations in psychological symptoms between Hispanic and non-Hispanic college students. For example, similar, levels of depression and stress symptoms were found for Hispanic and non-Hispanic students (Hoyt et al., 2021). In a nationally representative sample, similar levels and trajectories of anxiety over 3 months were reported by Hispanic and non-Hispanic Whites (Jacobs & Burch, 2021). Still, the socioeconomic disadvantages of Hispanic individuals in general may make the cultural group vulnerable to experiencing negative consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to recent reports, elevated unemployment rates and educational disruptions among Hispanic individuals have been found (e.g., Congressional Research Service Report, 2020; Montenovo et al., 2021), which may be negatively impactful to psychological well-being of Hispanic young adults during the pandemic. Given that the Hispanic population was approximately 18.5% in 2019 and estimated to reach 27.5% of the US population by 2060 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020), it is critical to better understand the negative psychological consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic for this vulnerable cultural group, particularly the young adult Hispanic subgroup.

In order to anticipate and counteract the negative psychological outcomes of the continuing pandemic, it is important to understand which aspects of the pandemic are most challenging for which groups. In fact, inconsistent associations between pandemic-related stressors and responses have been found in studies conducted within and outside of the US and no clear explanation has emerged for differing findings. Specifically, some evidence shows that the death of someone close due to COVID-19 typically has strong associations with depression (e.g., Nie et al., 2020), anxiety (e.g., Nie et al., 2020), and stress (e.g., Fan et al., 2021), but there are also a few reports of limited to no association between COVID-19 death and psychological outcomes for student samples within and outside the US (Díaz-Jiménez et al., 2020; Oh et al., 2021). Similarly, one’s own COVID-19 infection and infection in the family are generally associated with elevated psychopathology including depression, anxiety, and stress in the general population and college students across the world (Fan et al., 2021; Knowles et al., 2021; Nie et al., 2020; Oh et al., 2021; Sánchez-Teruel et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020). Yet, some counterevidence exists, with a few studies finding that one’s own infection and/or the infection of someone close had limited or no associations with psychological symptoms in the US and other countries (e.g.,Frontera et al., 2021; Horesh et al., 2020; Shanahan et al., 2020). The few scattered studies that report no or very minimal association between COVID-19 stressors and psychological outcomes do not yet appear to have a consistent through line and even less is known about where Hispanic young adults fit in the emerging picture. Unfortunately, none of the research to date has examined a sample composed solely of Hispanic participants, and as such, the existence and magnitude of possible associations between COVID-19 stressors and psychological outcomes in Hispanic individuals is particularly uncertain.

The negative psychological impacts of pandemic-related financial stress and education disruption have also been reported. Both financial stress (Balakrishnan et al., 2022; Kujawa et al., 2020; Oh et al., 2021) and school stress (Kujawa et al., 2020; Tasso et al., 2021) have been identified as strong predictors of elevated psychopathology including depression, anxiety, and stress in the US and across the world. However, the level and associations of these variables likely vary among different ethnic and racial groups and research has not yet addressed this question. For example, one study using a non-Hispanic White American sample found that financial stress did not affect general worry symptoms during the pandemic (Nitschke et al., 2021). Among a Hispanic sample, it seems likely that the exacerbated unemployment rates due to the pandemic and pandemic-related educational disruptions worsened by Hispanics individuals’ low levels of access to computers and internet for educational use (e.g., Congressional Research Service Report, 2020; Montenovo et al., 2021) may cause negative psychological consequences in Hispanic college students. This has yet to be examined.

The available research to date, as noted above, indicates the complexity of attempting to predict the psychological consequences of various COVID-19 stressors for a broad range of groups. Further, the relative impacts of COVID-19 stressors on psychological outcomes, such as whether a family member’s death due to COVID-19 causes more severe psychological distress than a COVID-19 infection in the family, are unclear. Most past research examined adverse psychological effects in response to each binary-coded stressor category alone (e.g., death due to COVID-19 vs. no death; COVID-19 infection vs. no infection). These were valuable contributions to our knowledge base, comparing the presence of a COVID-19 stressor to the absence of it (e.g., Díaz-Jiménez et al., 2020; Horesh et al., 2020; Nie et al., 2020; Oh et al., 2021). An important next step is to examine outcomes between COVID-19 stressors. It is not yet known which stressors of the pandemic are the most challenging to cope with for whom. Identifying a hierarchy of pandemic-related stressors and responses for different groups may contribute to the development of more targeted and nuanced preventive actions against the negative impacts of the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic.

Resilience and perceived social support as moderators

Varying associations between specific pandemic stressors (e.g., COVID-19 infection or death) and negative psychological outcomes seem to suggest the presence of moderator variables. Personal resources, such as resilience, have been theorized to have stress-buffering effects (Carver, 1998), and thus are potential moderators worthy of study. According to Carver’s (1998) model, resilience is characterized by the ability to bounce back to prior psychological functioning despite stressful experiences. Connor and Davidson’s model of resilience (Connor & Davidson, 2003; Davidson et al., 2005) addresses outcomes from a disruption of a biopsychospiritual balance in response to stressors, which include one’s capacity to bounce back to the previous balance or grow toward higher levels of functioning.

These models suggest that resilience levels may strengthen or weaken the associations between COVID-19 stressors and psychological symptoms. Limited empirical studies have examined the potential buffering effects of resilience against psychological distress in response to pandemic-related stressor variables, which have produced limited and mixed evidence for the buffering model. Chan et al. (2021) reported that the association between the summed number of COVID-19 stressors participants experienced and depression, but not anxiety, was significantly moderated by resilience in a US adult sample. By contrast, Traunmüller et al. (2021) found that resilience had a buffering effect for anxiety, but not for depression and stress levels, in response to early pandemic psychological impacts in Austrian adults. Knowles et al. (2021) reported that resilience moderated the association between the number of COVID-19 related stressors people experienced and suicidal thoughts in adults in the United Kingdom (UK). Still unknown is whether resilience plays a buffering role in the associations between specific pandemic stressors and psychological symptoms in different cultural groups, such as Hispanic individuals.

An equally important stress-buffering factor relevant to Hispanic culture is social support. Hispanic cultures are known for strong family ties (e.g., familismo) (e.g., Campos et al., 2014; Sabogal et al., 1987). The buffering hypothesis of social support (Cohen & Wills, 1985) would suggest that despite the relatively greater load of pandemic-related stressors experienced by this group, familismo may provide some buffering via perceived social support. Perceived social support has been found to have a strong buffering effect among people who developed psychological symptoms in response to traumatic or negative life events (e.g., Evans et al., 2013; Gaffey et al., 2019). The few COVID-19 studies conducted to date have produced inconsistent findings regarding the potential benefits of perceived social support during the pandemic. For example, Northfield and Johnston (2021) found that perceived social support acted as a moderator on the relationship between posttraumatic stress severity and posttraumatic growth in US adults, the majority of which were non-Hispanic White Americans, with those with the highest levels of perceived social support also showing the strongest posttraumatic growth in response to posttraumatic stress symptoms. Lee and Waters (2021) surveyed Asian Americans and Asians living in the US and found mixed evidence for a moderating role of perceived social support, with higher levels of perceived social support weakening the association of depression symptoms, but not of anxiety symptoms, with racial discrimination experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. To date there is no research on the potential buffering role of perceived social support in the associations between COVID-19 stressors and psychological symptoms for Hispanics.

Hypothesis

The current study examined the effects of specific COVID-19 stressors (e.g., family member’s death due to COVID-19, COVID-19 infection) on psychopathology and the potential buffering roles of resilience and perceived social support in the association between such COVID-19 stressors and psychological symptoms in a Hispanic student sample, which is an understudied, high-risk group. The following hypotheses were examined: 1) On average, participants would report the most intense psychological symptoms resulting from an experience of COVID-19-related death in the family (DTH), relatively fewer symptoms in response to an experience of COVID-19 infection (self or family) (INF), and the fewest symptoms in response to financial and/or school stressors caused by the pandemic in the absence of COVID-19 infection and death (FSC); and 2) the magnitudes of the associations between the COVID-19 stressor types (DTH, INF, or FSC) and psychological symptoms would be moderated by resilience and perceived social support, such that higher resilience and higher perceived social support would weaken the associations.

Method

Participants and procedure

The current study was approved by the institutional review board of the university. Participants were recruited from the subject pool of a psychology department at a state university in Texas. Individuals who were 18 years old or older were eligible for the study. No other selection criteria were used. Interested and eligible individuals logged onto an online research sign-up system hosted by the psychology department. Individuals who signed up for the study via the online sign-up system were led to the online study page. They first read the online consent form and individuals who agreed to participate completed the online questionnaires anonymously. Participants completed the stressor section of the questionnaire and were then instructed to report their psychological symptoms in reference to the COVID-19 stressors they endorsed. The platform of the survey was Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Participants received course extra credit as compensation for their time. Data were collected from January 2021 to April 2021 while students were engaged in distance online learning due to the pandemic. The university is located in a south Texas region where 92.6% of the population are Hispanic, and the socio-economic (SES) levels (e.g., household income, education, health insurance, computer and internet use) of the region are below the national averages (US Census, 2016–2020).

Measures

Demographic items

A demographic questionnaire asked participants to provide their age, sex, and ethnicity.

COVID-19 stressors

To assess COVID-19 stressors, participants were provided with a list of stressors. Accompanying each stressor was a description of each item: (1) own infection, (2) infection in the family, (3) death of a family member due to COVID-19, (4) financial concerns due to COVID-19, and (5) school-related stress due to COVID-19. Participants were asked to select all the stressors they experienced. In addition, the respondent was asked to provide simple descriptions of the stressor(s) in a small text box in an open-ended manner (e.g., my family member passed away due to COVID-19 and I contracted COVID-19). To confirm the COVID-19 stressor selection from the list, two graduate research assistants (RAs) independently coded the open-ended stressor descriptions to classify them into the five categories, blind to participant responses to the close-ended stressor list. If the respondent provided descriptions that included more than one stressor, all the reported stressors were recorded. For example, if the respondent wrote “My family member passed away due to COVID-19 and I contracted COVID-19,” this person’s statement was coded as both the “(1) own infection” category and the “(3) death of a family member due to COVID-19” category. The first author checked the results. The agreement rates between the two coders for the categories ranged from 96 to 99%. The participant responses to the stressor category list and the coded categories were fully matched.

Stress

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen et al., 1983) is a 10-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the level of stress associated with experienced stressful events during the last month. Participants rated items on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). The scale produces total scores. Higher scores indicate greater levels of stress. Past studies with college students reported mean scores ranging from 15 to 18.4 (e.g., Baik et al., 2019; Roberti et al., 2006). Good internal consistency reliability estimates (alpha = 0.84-0.86) have been reported (Cohen et al., 1983). The Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was 0.81.

Anxiety

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006) is a 7-item self-report questionnaire that assesses anxiety symptom severity during the past 2 weeks consistent with the DSM criteria for generalized anxiety disorder. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (nearly every day). The scale yields total scores, and higher scores indicate higher anxiety levels. The cutoff scores are 5 for mild, 10 for moderate, and 15 for severe anxiety, and with a score of 10, the GAD-7 has a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 82% for Generalized Anxiety Disorder (Spitzer et al., 2006). A high internal consistency reliability estimate (alpha = 0.92) was reported (Spitzer et al., 2006). The Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was 0.92.

Depression

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001) is a 9-item self-report questionnaire that assesses depression symptom severity corresponding to DSM criteria. Participants in the study rated each item on a 4-point Likert scale (0–3) where 1 is “not at all” and 3 is “nearly every day.” The scale produces total scores, and higher scores suggest greater depression levels. The cutoff scores are 5 for mild, 10 for moderate, 15 for moderately severe, and 20 for severe depression (Kroenke et al., 2001). Good internal reliability estimates (alpha = 0.86-0.89) have been reported (Kroenke et al., 2001). The Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was 0.89. Scores of 15 or greater indicate potentially diagnosable levels of depression (Kroenke et al., 2001).

Resilience

The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale-10 (CD-RISC10; Campbell-Sills & Stein, 2007) is a 10-item self-report questionnaire developed based on the original 25-item version (Connor & Davidson, 2003) that assesses resilience. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (not true at all) to 4 (true nearly all the time). The scale yields total scores. Higher scores indicate higher levels of resilience. Good internal consistency reliability estimate (alpha = 0.85) has been reported (Campbell-Sills & Stein, 2007). A mean score of 27.2 (SD = 5.84) for a college student sample was reported (Campbell-Sills & Stein, 2007). The Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was 0.90.

Perceived social support

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Zimet et al., 1988) is a 12-item self-report questionnaire that assesses perceived social support. Participants rated each item on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree). The current study used total scores, with higher scores indicating greater levels of perceived social support. A psychometric study on the MSPSS in a college student sample reported item means ranging from 5.32 to 5.91 (Ermis-Demirtas et al., 2018). Good internal consistency reliability of the total scale (alpha = 0.85) was reported (Zimet et al., 1988). The Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was 0.93.

Analysis plan

The COVID-19 stressor variable was coded as a categorical variable. Individuals who reported school and/or financial stressors due to the pandemic in the absence of infection and death in the family were in the FSC group. Individuals who reported at least one infection case within their family (self, family) but reported no death were in the INF group. Individuals who reported at least one death due to COVID-19 in their family were in the DTH group. Descriptive statistics and correlations among the groups, symptoms, and moderator variables were obtained with SPSS version 25. ANOVAs were conducted to compare the groups on the variables.

A series of moderation analyses were performed using PROCESS (Hayes, 2022). Two sets of dummy coding were applied to the categorical predictor to generate the three group comparison predictors (Hayes & Montoya, 2017). The first set used the FSC group as the reference group to generate two group comparison predictors: FSC(0) vs. INF(1) and FSC(0) vs. DTH(1), and the second set used the INF group as the reference group to generate a group comparison predictor: INF(0) vs. DTH(1). Stress, depression, and anxiety were the criteria. Resilience and perceived social support were examined separately as a moderator. The two sets of coding were run for each model. To obtain 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals for the moderation models, 5,000 bootstrap estimates were used.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The total sample included 664 Hispanic students, 179 males (27.0%), 483 females (73.2%), and 2 gender-unspecified individuals. The mean age of participants was 20.2 (SD = 3.92, range 18 to 56). Among the 664 participants, 104 (15.7%) reported a family member’s death due to COVID-19 infection (DTH) and 236 participants (35.5%) reported their own or a family member’s COVID-19 infection but no death in the family (INF). Since all participants (n = 664) reported financial and/or school-related stressors due to the pandemic, the remaining 324 participants (48.8%) were in the financial/school related stress only group (FSC).

Means and standard deviations of stress (PSS), anxiety (GAD7), depression (PHQ9), resilience (CD-RISC10), and perceived social support (MSPSS) and the group comparison results are presented in Table 1. Significant group differences were found for stress, anxiety, and depression. On average the DTH and INF groups reported significantly higher stress, anxiety, and depression than the FSC group. The DTH and INF groups did not significantly differ on any symptom levels. No significant group differences were found for resilience or perceived social support.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Group Comparisons

| Variable | Financial/ school stress (n = 324) |

Infection (n = 236) |

Death (n = 104) |

Group comparison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F | p | |

| PSS | 20.24a | 5.17 | 22.38b | 6.02 | 23.62b | 6.10 | 18.32 | < .01 |

| GAD7 | 6.82a | 5.32 | 8.36b | 5.76 | 9.13b | 6.29 | 8.87 | < .01 |

| PHQ9 | 8.74a | 6.07 | 10.21b | 6.45 | 11.13b | 6.69 | 7.09 | < .01 |

| CD-RISC10 | 25.09 | 7.37 | 24.28 | 7.03 | 23.48 | 7.09 | 2.22 | .11 |

| MSPSS | 5.26 | 1.25 | 5.30 | 1.29 | 5.36 | 1.22 | .28 | .76 |

Note: PSS = Perceived Stress Scale; PHQ9 = Patient Health Questionnaire 9; GAD7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale; CD-RISC10 = Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale-10; MSPSS = Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Significant differences (p < .05) between the three groups are denoted with alphabetical superscripts

Anxiety and depression symptoms were also examined categorically. Regarding severity of anxiety symptoms, 48 (46.2%) of those in the DTH group, 98 (41.5%) in the INF group, and 93 (28.7%) in the FSC group reported at least moderate levels of anxiety (GAD7 ≥ 10), which may need clinical attention (Spitzer et al., 2006). For depressive symptoms, 57 (54.8%) individuals in the DTH group, 121 (51.3%) in the INF group, and 126 (39.5%) in the FSC group reported at least moderate levels of depression (PHQ9 ≥ 10), which may need clinical attention (Kroenke et al., 2001). The perceived stress measure (PSS) has not typically been used categorically and does not have established clinical cut points, but an examination of the average scores for college students reported in past studies (e.g.,Baik et al., 2019; Roberti et al., 2006) suggests a typical range between 15 and 18 and the means of perceived stress across our three groups (DTH, INF, FSC) were all above these previous scores, suggesting elevated stress in all three groups.

A series of Chi-square analyses of the potential clinical cut points for depression and anxiety found significant differences in the proportion of individuals with moderate or higher depression and anxiety between the DTH and FSC groups and between the INF and FSC groups. The DTH and INF groups had no difference in the proportion of participants with these higher levels of depression and anxiety.

Correlations

Correlations among a single combined COVID-19 stressor variable (FSC = 0; INF = 1; DTH = 2), the three psychological symptom variables (stress, anxiety, and depression), resilience, and perceived social support are presented in Table 2. The COVID-19 stressor variable was significantly positively correlated with all psychological symptom levels and negatively correlated with resilience. The stressor variable had no significant correlation with perceived social support. Levels of all psychological symptom variables were significantly negatively correlated with resilience and perceived social support.

Table 2.

Correlations

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Stressor | - | ||||

| 2. PSS10 | .226** | - | |||

| 3. GAD7 | .159** | .659** | - | ||

| 4. PHQ9 | .144** | .610** | .755** | - | |

| 5. CD-RISC10 | -.082* | -.429** | -.265** | -.279** | - |

| 6. MSPSS | .029 | -.284** | -.254** | -.283** | .272** |

Note: PSS = Perceived Stress Scale; PHQ9 = Patient Health Questionnaire 9; GAD7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale; CD-RISC10 = Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale-10; MSPSS = Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. **p < .01. *p < .05

The stressor variable was coded as follows: death = 2; infection = 1; financial/school = 0

Moderation models

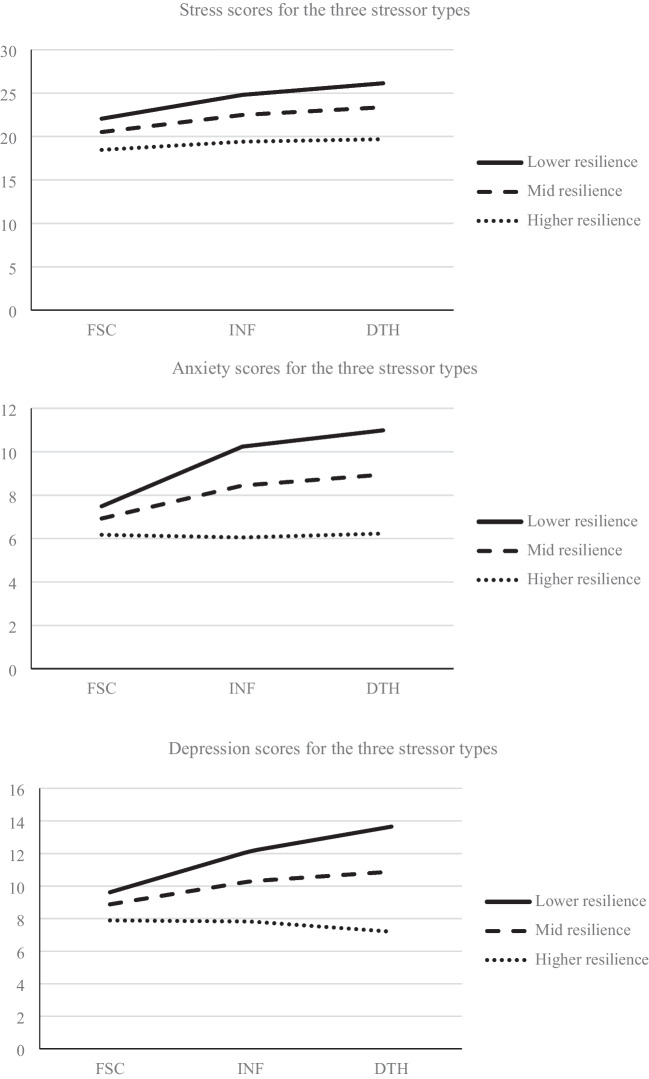

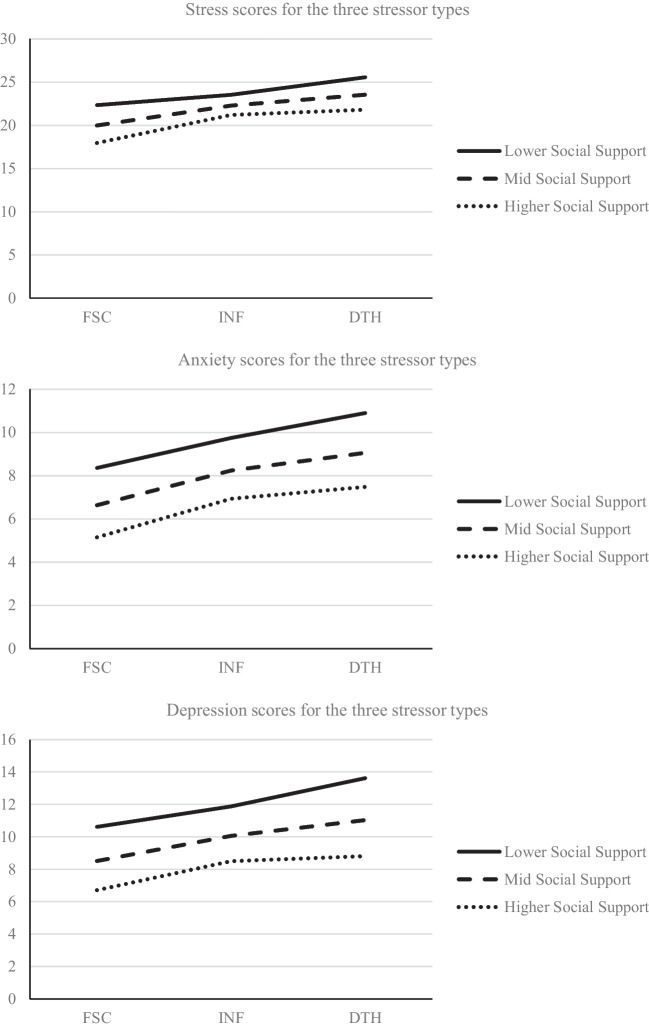

A series of moderation analyses were performed to examine the moderating roles of resilience and perceived social support in the association between the COVID-19 stressor variable and psychological symptoms. Results of the moderation effects are illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

Moderating role of resilience. Note: Stressor types: FSC = Financial/school stress due to COVID-19; INF = COVID-19 infection; DTH = death due to COVID-19

Fig. 2.

Moderating role of perceived social support. Note: Stressor type: FSC = Financial/school stress due to COVID-19; INF = COVID-19 infection; DTH = death due to COVID-19

The role of resilience as a moderator

When the FSC group was the reference group, the FSC(0)/INF(1) comparison predictor was significant for stress (β = 0.33, p < 0.01), anxiety (β = 0.25, p < 0.01), and depression (β = 0.21, p < 0.05). The FSC(0)/DTH(1) comparison predictor was also significant for stress (β = 0.47, p < 0.01), anxiety (β = 0.33, p < 0.01), and depression (β = 0.29, p < 0.01). Resilience was significant for stress (β = -0.32, p < 0.01), anxiety (β = -0.12, p < 0.05), and depression (β = -0.14, p < 0.01). In contrast, when the INF group was the reference group, the INF(0)/DTH(1) comparison predictor was not significant for stress (β = 0.15, p = 0.16), anxiety (β = 0.08, p = 0.45), or depression (β = 0.08, p = 0.48). Resilience was significant for stress (β = -0.48, p < 0.01), anxiety (β = -0.38, p < 0.01), and depression (β = -0.35, p < 0.01).

The overall models were significant for stress (R2 = 0.23, F(5, 658) = 39.77, p < 0.01), anxiety (R2 = 0.11, F(5, 658) = 16.78, p < 0.01), and depression (R2 = 0.11, F(5, 658) = 16.14, p < 0.01). The interaction effects significantly improved the models for stress (ΔR2 = 0.01, F(2, 658) = 4.22, p < 0.05), anxiety (ΔR2 = 0.02, F(2, 658) = 7.06, p < 0.01), and depression (ΔR2 = 0.02, F(2, 658) = 7.53, p < 0.01). The coefficients for the interaction terms (predictor x resilience) revealed that resilience moderated the paths between the FSC(0)/INF(1) comparison predictor and stress (β = -0.16, p < 0.01), anxiety (β = -0.26, p < 0.01), and depression, (β = -0.21, p < 0.05), and the paths between the FSC(0)/DTH(1) comparison predictor and stress (β = -0.25, p < 0.05), anxiety (β = -0.31, p < 0.01), and depression (β = -0.38, p < 0.01). The significant conditional effects by resilience levels are shown in Table 3. Among individuals with relatively low resilience and those with average resilience, both DTH and INF predicted significantly higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression than FSC. Among individuals with relatively high resilience, DTH, INF, and FSC predicted similarly lower levels of stress, anxiety, and depression. The coefficients for the interaction terms (predictor x resilience) showed that resilience did not moderate the path between the INF(0)/DTH(1) comparison predictor and stress (β = -0.09, p = 0.38), anxiety (β = -0.05, p = 0.65), and depression (β = -0.17, p = 0.13). The differences between the INF and DTH groups on their symptom scores remained relatively similar across levels of resilience.

Table 3.

Significant Conditional Effects: Resilience (CD-RISC 10) as a Moderator

| Predictor | Moderator level | Criterion | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSS | GAD7 | PHQ9 | |||||||||||

| Conditional | 95% CI | Conditional | 95% CI | Conditional | 95% CI | ||||||||

| Effects | SE | LL | UL | Effects | SE | LL | UL | Effects | SE | LL | UL | ||

| DTH(1) vs. FSC(0) | Lower | .47** | .11 | .27 | .68 | ..48** | .11 | .27 | .70 | .40** | .11 | .18 | .61 |

| Mid | .34** | .08 | .19 | .49 | .27** | .08 | .11 | .43 | .22** | .08 | .06 | .38 | |

| Higher | .16 | .11 | -.05 | .38 | -.02 | .12 | -.25 | .21 | -.01 | .11 | -.24 | .22 | |

| INF(1) vs. FSC(0) | Lower | .71** | .13 | .45 | .96 | .61** | .14 | .34 | .89 | .63** | .14 | .36 | .90 |

| Mid | .49** | .10 | .30 | .69 | .36** | .11 | .14 | .57 | .31** | .11 | .10 | .52 | |

| Higher | .21 | .15 | -.08 | .51 | -.01 | .16 | -.31 | .33 | -.11 | .16 | -.43 | .21 | |

Note. DTH = death due to COVID-19; INF = COVID-19 infection; FSC = financial/school stress due to COVID-19; PSS = Perceived Stress Scale; PHQ9 = Patient Health Questionnaire 9; GAD7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale; CD-RISC10 = Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale-10; CI = Confidence Interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit. **p < .01, *p < .05

The role of perceived social support as a moderator

When the FSC group was the reference group, the FSC(0)/INF(1) comparison predictor was significant for stress (β = 0.38, p < 0.01), anxiety (β = 0.28, p < 0.01), and depression (β = 0.24, p < 0.01). The FSC(0)/DTH(1) comparison predictor was also significant for stress (β = 0.61, p < 0.01), anxiety (β = 0.43, p < 0.01), and depression (β = 0.42, p < 0.01). Perceived social support was significant for stress (β = -0.36, p < 0.01), anxiety (β = -0.27, p < 0.01), and depression (β = -0.29, p < 0.01). When the INF group was the reference group, the INF(0)/DTH(1) comparison predictor was significant for stress (β = 0.23, p < 0.05), and was not significant for anxiety (β = 0.15, p = 0.19) or depression (β = 0.16, p = 0.15). Perceived social support was significant for stress (β = -0.12, p < 0.05), anxiety (β = -0.24, p < 0.01), and depression (β = -0.25, p < 0.01).

The overall models were significant for stress (R2 = 0.14, F(5, 658) = 21.97, p < 0.01), anxiety (R2 = 0.09, F(5, 658) = 13.58, p < 0.01), and depression (R2 = 0.10, F(5, 658) = 15.42, p < 0.01). The interaction effects did not improve the models for stress (ΔR2 = 0.006, F(2, 658) = 2.379, p = 0.09), anxiety (ΔR2 = 0.0004, F(2, 658) = 0.127, p = 0.88), and depression (ΔR2 = 0.001, F(2, 658) = 0.446, p = 0.64), revealing no moderation effects of perceived social support. The group differences for symptom scores did not change significantly in response to perceived social support levels.

Discussion

The current study examined the associations between specific COVID-19 stressors and psychological symptoms and the moderating roles of resilience and perceived social support among Hispanic young adults in a socioeconomically disadvantaged south Texas region. The effects of self and family member’s COVID-19 infection, family member’s death due to COVID-19, and financial and/or school-related pandemic stresses in the absence of COVID-19 infection and death were compared.

Overall, elevated psychological symptoms were found for all three stressor groups compared to the norms and scores reported in pre-pandemic research (Baik et al., 2019; Kroenke et al., 2001; Roberti et al., 2006; Spitzer et al., 2006). This is consistent with other COVID-19 studies reporting increased psychopathological symptoms associated with the death of someone close (e.g., Fan et al., 2021; Nie et al., 2021), one’s own COVID-19 infection or infection in the family (e.g., Fan et al., 2021; Oh et al., 2021; Wang, et al., 2020), and educational and financial stressors due to the pandemic (e.g.,Oh et al., 2021; Tasso et al., 2021) in college students in the US and internationally. The results also provide counter evidence for studies reporting no associations between COVID-19 stressors and significant psychological consequences (e.g., Díaz-Jiménez et al., 2020; Horesh et al., 2020). These results seem to suggest the possibility that Hispanics are vulnerable to various negative psychological outcomes in response to COVID-19 stressors, similar to many non-Hispanic US and international samples. Yet alternative explanations for the results exist, such that elevated symptoms were due partly to unmeasured stressors unrelated to the COVID-19 pandemic, declining mental health in college students globally (Auerbach et al., 2018), or other factors, which the current study did not assess.

Importantly, the current study found that all participants reported financial or school-related stress or both due to the pandemic. These results appear to reflect the socio-economic disadvantages Hispanic individuals have been experiencing, which the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated (e.g., Montenovo et al., 2021). It is likely that the online distance learning taking place during the data collection period negatively affected particularly those who had limited access to computing devices, the internet, and quiet private spaces for schoolwork and study time. Those with financial and/or school stressors due to the pandemic in the absence of COVID-19 infection and death was the reference group in the current study, and they reported elevated psychopathology symptoms.

As expected, the COVID-19 infection and death groups reported significantly higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression, on average, than the financial and/or school stress group. However, there were no mean symptom level differences between the COVID-19 infection and death groups. In addition, the proportions of moderate or greater anxiety and depression cases were similar for the COVID-19 infection and death groups. Although a general assumption may be that bereavement due to the COVID-19 pandemic may result in more negative psychological consequences than COVID-19 infection in the family, the average magnitudes of these impacts were similar among the present Hispanic sample. This finding suggests the potential importance of planning similarly high levels of preventive and intervention efforts against severe psychological distress for those who have experienced a COVID-19 infection only or COVID-19 death. Although research examining acute responses to pandemic stressors will also be needed to create a fuller picture, as the present research examined current symptoms (e.g., last 2 weeks, last month) related to COVID-19 stressors occurring up to a year previously, it is possible that acute responses to COVID-19 death and infection differed whereas delayed response did not.

The hypothesized buffering role of resilience, but not of perceived social support, was largely supported by the current data. Specifically, greater resilience buffered against the negative effects of COVID-19 infection and death on mental health (Table 3, Fig. 1). Among relatively highly resilient people, the magnitudes of the impact of COVID-19 infection or death on stress, anxiety, and depression were similar to those of school and financial stressors due to COVID-19. By contrast, among people with lower to average resilience, COVID-19 infection and death were associated with significantly elevated stress, anxiety, and depression compared to school and financial stress due to the pandemic. These results confirm the significant buffering role of resilience, consistent with protective models of resilience (e.g., Carver, 1998; Connor & Davidson, 2003), when comparing effects of COVID-19 death or COVID-19 infection stressors with those with financial and/or school stressors due to COVID-19.

In contrast, resilience did not play a buffering role when comparing stress, anxiety, and depression levels between groups with COVID-19 infection and COVID-19 death. The lack of buffering effects of resilience against psychological symptoms when comparing COVID-19 infection and COVID-19 death stressors may be attributable to several possibilities. One possibility is that the impact of COVID-19 infection was sufficiently high that there may be ceiling effects to the buffering model for these stressors. Another possibility is that buffering effects for the two groups might emerge in the longer run. It may be that there is little difference in the acute aftermath of COVID-19 infection and death but that differences would emerge over time. In addition, the relatively smaller sample size of the COVID-19 death group might have made it difficult to detect small effects. Replications with longitudinal assessments with a larger sample size per group are needed to examine these possibilities. The effect of the pandemic on resilience levels (lowered, bounced back, or increased) for this group is unknown, as there is no study that reported norms for resilience scores for healthy Hispanic students prior to the pandemic. A reference score of resilience obtained from a college sample is 27.2 (SD = 5.84) (Campbell-Sills & Stein, 2007), suggesting a possibility that the current participants were experiencing relatively lower resilience levels on average (mean scores ranging from 23.5 to 25.1) during the pandemic. Importantly, the buffering effects of resilience demonstrated by the current study are somewhat limited but are consistent with the moderating effect of resilience on the association between the number of COVID-19 related stressors and suicidal thoughts in adults in the UK reported by Knowles et al. (2021). Altogether, some empirical evidence supports the buffering model of resilience for the negative consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic in different cultural groups, including Hispanic young adults. Importantly, resilience itself was a significant predictor of levels of the three symptom domains. Specifically, higher resilience was significantly associated with lower stress, anxiety, and depression. It is possible that resilience played a causal role in preventing the development of psychological symptoms or in reducing psychological symptoms developed in response to various COVID-19 stressors. The reverse may also be the case, with those with fewer psychological symptoms experiencing and reporting higher resilience levels (e.g., Eddington et al., 2017; McGuire et al., 2018).

The hypothesized buffering effects of perceived social support were not found in the current study. The gaps of symptom levels for the death, infection, and financial/school stressor groups did not change statistically significantly across levels of perceived social support (Fig. 2). These results are contrary to a buffering hypothesis of social support (Cohen & Wills, 1985). These findings are also somewhat inconsistent with the buffering role of perceived social support identified by past COVID-19 studies in non-student samples with different predictor variables (Lee & Waters, 2021; Northfield & Johnston, 2021). The differences between these studies and the current research (e.g., student vs. non-student samples, COVID-19 stressors as predictors vs. psychological symptoms as predictors, Hispanic individuals vs. White Americans vs. Asians/Asian Americans) are likely responsible for the different outcomes. It is also possible that the cultural characteristics of the current sample played an important role in our findings. Family ties are central in Hispanic culture (e.g., familismo) (e.g.,Campos et al., 2014; Sabogal et al., 1987). In addition, data were collected while classes were online and on-campus, in-person interactions and peer support were at best quite limited. In fact, the current three groups all reported lower MSPSS scores than healthy Hispanic college students prior to the pandemic (Ermis-Demirtas et al., 2018). Reduced levels of actual and perceived social support due to social isolation, remote learning, quarantine, COVID-19 infection, or the death of a family member due to COVID-19 might have reduced the buffering power of social support, particularly within this family-centric cultural group. Notably however, direct effects of perceived social support on psychological symptoms, similar to those of resilience, were significant. A possible interpretation of these findings is an additive model of perceived social support (Barrera, 1986), rather than a buffering model. The additive model suggests that lowered perceived social support during the pandemic may have played a causal role in exacerbating psychological distress in response to the pandemic.

In sum, the current results align with the theoretical models of resilience (Carver, 1998; Connor & Davidson, 2003), which suggest resilience as a protective factor against adversity, and provide some support for the buffering role of resilience in response to COVID-19 stressors in Hispanic young adults. On the other hand, perceived social support did not show its theorized buffering role. Both resilience and perceived social support had direct effects to psychological outcomes. These results have important implications. Under circumstances such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which limit social interactions, internal personal resources such as resilience, rather than external personal resources such as social support, might be a critical factor that may protect psychological well-being from the impacts of significant stressors, such as COVID-19 death or infection. Lowered perceived social support, which was likely an inevitable consequence of the pandemic, may directly negatively impact psychological well-being. Efforts to improve or at least maintain resilience may protect Hispanic individuals from elevated psychological distress in response to the continuing COVID-19 pandemic or other long-term adverse situations.

Limitations and future directions

The current results should be interpreted in light of several strengths and limitations of the study. First, although the large Hispanic sample is a strength of the study and also provides information about those residing in socio-economically disadvantaged areas, the results may not be fully applicable to other cultural, ethnic, racial, or age groups, or those in economically prosperous areas. The large proportion of female participants may also offer limited applicability to non-females. Second, the current study examined models based on solid psychological theories and empirical evidence, yet there is always more to be examined and future research should explore the possible effects of variables such as family composition, socioeconomic factors, stressors unrelated to the pandemic, and preexisting psychopathology. Third, although the current cross-sectional design with self-report measures produced a relatively large number of participants within a short period of time, the design also has disadvantages including the lack of data to address the directionality between the moderators and psychological outcomes and the possible presence of common method biases inflating associations between variables. The longitudinal consequences of the COVID-19 stressors were not addressed in the current study. Fourth, the current study was conducted in the region where the SES levels are below the national averages (US Census, 2016–2020), yet SES variables such as income were not directly measured and the role of SES in the current results is unknown. Finally, the current study conceptualized resilience through Connor and Davidson’s (2003) lens and assessed resilience with their measure, but there are other formulations of resilience including a socio-ecological model (Ungar, 2007), a family-based resilience model (e.g., Prime et al., 2020), and a cognitive sets model (Munoz et al., 2017). Different resilience conceptualizations and measures may have led to different results. Future research should attempt to replicate these findings in diverse samples and examine broadened models with COVID-19 and non-COVID stressor variables as well as a wider variety of demographic variables over longitudinal assessment points through diverse assessment methods.

Conclusion

Overall, the current study was the first to examine the buffering roles of resilience and perceived social support in the association between specific COVID-19 stressors (death, infection, and financial/school stressors) and psychological outcomes (stress, anxiety, and depression) in Hispanics who are an understudied and underserved cultural group significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The examined models were new to the literature and the results offer the important implications stated above. Continuing investigations into the buffering roles of various internal and external personal resources against the negative consequences of the pandemic, among Hispanics and beyond, will contribute to understanding and improving mental health in response to the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic. These efforts will, in turn, support the development of more targeted preventive actions and interventions against the negative impacts of the pandemic for vulnerable groups including Hispanic young adults.

Acknowledgements

None

Funding

We received no funding for this study.

Data availability

The dataset contains sensitive information and thus only partial data without sensitive information are available from the following link.

Item-level data without sensitive information can be obtained from the first author upon request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aucejo EM, French J, Ugalde Araya MP, Zafar B. The impact of COVID-19 on student experiences and expectations: Evidence from a survey. Journal of Public Economics. 2020;191:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach RP, Mortier P, Bruffaerts R, Alonso J, Benjet C, Cuijpers P, Demyttenaere K, Ebert DD, Green JG, Hasking P, Murray E, Nock MK, Pinder-Amaker S, Sampson NA, Stein DJ, Vilagut G, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2018;127(7):623–638. doi: 10.1037/abn0000362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baik SH, Fox RS, Mills SD, Roesch SC, Sadler GR, Klonoff EA, Malcarne VL. Reliability and validity of the perceived stress scale-10 in Hispanic Americans with English or Spanish language preference. Journal of Health Psychology. 2019;24(5):628–639. doi: 10.1177/1359105316684938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan V, Ng KS, Kaur W, Govaichelvan K, Lee ZL. COVID-19 depression an1d its risk factors in Asia Pacific—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2022;298:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.11.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M. Distinctions between social support concepts, measures, and models. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1986;14(4):413–445. doi: 10.1007/BF00922627. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. Resilience and thriving: Issues, models, and linkages. Journal of Social Issues. 1998;54(2):245–266. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.641998064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20(6):1019–1028. doi: 10.1002/jts.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos B, Ullman JB, Aguilera A, DunkelSchetter C. Familism and psychological health: The intervening role of closeness and social support. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2014;20(2):191–201. doi: 10.1037/a0034094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Demographic Trends of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the US reported to CDC. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#demographics.

- Chan, A. C. Y., Piehler, T. F., & Ho, G. W. K. (2021). Resilience and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from Minnesota and Hong Kong. Journal of AffectiveDisorders, 295, 771–780. 10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chang J, Ji Y, Li Y, Pan H, Su P. Prevalence of anxiety symptom and depressive symptom among college students during COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;292:242–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24(4):385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98(2):310–357. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Research Service Report (2020). Unemployment Rates During the COVID-19 Pandemic. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R46554.pdf.

- Cunningham TJ, Fields EC, Garcia SM, Kensinger EA. The relation between age and experienced stress, worry, affect, and depression during the spring 2020 phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Emotion. 2021;21(8):1660–1670. doi: 10.1037/emo0000982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Jiménez RM, Caravaca-Sánchez F, Martín-Cano MC, De la Fuente-Robles YM. Anxiety levels among social work students during the Covid-19 lockdown in Spain. Social Work in Health Care. 2020;59(9–10):681–693. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2020.1859044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) Depression and Anxiety. 2003;18:76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JR, Payne VM, Connor KM, Foa EB, Rothbaum BO, Hertzberg MA, Weisler RH. Trauma, resilience and saliostasis: Effects of treatment in post-traumatic stress disorder. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2005;20(1):43–48. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200501000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermis-Demirtas H, Watson JC, Karaman MA, Freeman P, Kumaran A, Haktanir A, Streeter AM. Psychometric properties of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support within Hispanic college students. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2018;40(4):472–485. doi: 10.1177/0739986318790733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eddington KM, Burgin CJ, Silvia PJ, Fallah N, Majestic C, Kwapil TR. The effects of psychotherapy for major depressive disorder on daily mood and functioning: A longitudinal experience sampling study. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2017;41(2):266–277. doi: 10.1007/s10608-016-9816-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire AP, Mota NP, Sippel LM, Connolly KM, Lyons JA. Increased resilience is associated with positive treatment outcomes for veterans with comorbid PTSD and substance use disorders. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2018;14(3):181–186. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2018.1464237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SE, Steel AL, DiLillo D. Child maltreatment severity and adult trauma symptoms: Does perceived social support play a buffering role? Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37(11):934–943. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan C, Fu P, Li X, Li M, Zhu M. Trauma exposure and the PTSD symptoms of college teachers during the peak of the COVID-19 outbreak. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress. 2021;37(5):914–927. doi: 10.1002/smi.3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French MT, Mortensen K, Timming AR. Psychological distress and coronavirus fears during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics. 2020;23(3):93–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frontera JA, Lewis A, Melmed K, Lin J, Kondziella D, Helbok R, Yaghi S, Meropol S, Wisniewski T, Balcer L, Galetta SL. Prevalence and predictors of prolonged cognitive and psychological symptoms following COVID-19 in the United States. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2021;13:11. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.690383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffey AE, Aranda F, Burns JW, Purim-Shem-Tov YA, Burgess HJ, Beckham JC, Bruehl S, Hobfoll SE. Race, psychosocial vulnerability and social support differences in inner-city women's symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Anxiety, Stress & Coping: An International Journal. 2019;32(1):18–31. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2018.1532078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: 3rd Edition. A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press.

- Hayes AF, Montoya AK. A tutorial on testing, visualizing, and probing an interaction involving a multicategorical variable in linear regression analysis. Communication Methods and Measures. 2017;11(1):1–30. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2016.1271116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horesh D, Kapel Lev-Ari R, Hasson-Ohayon I. Risk factors for psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel: Loneliness, age, gender, and health status play an important role. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2020;25(4):925–933. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt LT, Cohen AK, Dull B, Maker Castro E, Yazdani N. “Constant stress has become the new normal”: Stress and anxiety inequalities among U.S. college students in the time of COVID-19. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2021;68(2):270–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs M, Burch AE. Anxiety during the pandemic: Racial and ethnic differences in the trajectory of fear. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;292:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jehi, T., Khan, R., Dos Santos, H., & Majzoub, N. (2022). Effect of covid-19 outbreak on anxiety among students of higher education; a review of literature. Current Psychology: A Journal for Diverse Perspectives on Diverse Psychological Issues. 10.1007/s12144-021-02587-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Knowles, J. R. P., Gray, N. S., O'Connor, C., Pink, J., Simkiss, N. J., & Snowden, R. J. (2021). The role of hope and resilience in protecting against suicidal thoughts and behaviors during the covid-19 pandemic. Archives of Suicide Research, 26(3), 1487–1504. 10.1080/13811118.2021.1923599. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kujawa A, Green H, Compas BE, Dickey L, Pegg S. Exposure to COVID-19 pandemic stress: Associations with depression and anxiety in emerging adults in the United States. Depression and Anxiety. 2020;37(12):1280–1288. doi: 10.1002/da.23109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Waters SF. Asians and Asian Americans’ experiences of racial discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts on health outcomes and the buffering role of social support. Stigma and Health. 2021;6(1):70–78. doi: 10.1037/sah0000275. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montenovo, L., Jiang, X., Lozano Rojas, F., Schmutte, I.M., Simon, K.I., Weinberg, B.A., & Wing, C. (2021). Determinants of Disparities in Covid-19 Job Losses, National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w27132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Munoz, R. T., Brady, S., & Brown, V. (2017). The psychology of resilience: A model of the relationship of locus of control to hope among survivors of intimate partner violence. Trauma, 23(1), 102–111. 10.1037/trm0000102. [DOI]

- Nie X, Wang Q, Wang M, Zhao S, Liu L, Zhu Y, Chen H. Anxiety and depression and its correlates in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in wuhan. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 2020;25(2):1–6. doi: 10.1080/13651501.2020.1791345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie, X., Wang, Q., Wang, M., Zhao, S., Liu, L., Zhu, Y., & Chen, H. (2021). Anxiety and depression and its correlates in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in wuhan. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 25(2), 109–114. 10.1080/13651501.2020.1791345. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nitschke JP, Forbes PAG, Ali N, Cutler J, Apps MAJ, Lockwood PL, Lamm C. Resilience during uncertainty? Greater social connectedness during COVID-19 lockdown is associated with reduced distress and fatigue. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2021;26(2):553–569. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northfield, E., & Johnston, K. L. (2021). “I get by with a little help from my friends”: Posttraumatic growth in the COVID-19 pandemic. Traumatology.28(1), 195–201. 10.1037/trm0000321.

- Oh H, Marinovich C, Rajkumar R, Besecker M, Zhou S, Jacob L, Koyanagi A, Smith L. COVID-19 dimensions are related to depression and anxiety among US college students: Findings from the healthy minds survey 2020. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;292:270–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prime, H., Wade, M., & Browne, D. T. (2020). Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist, 75(5), 631–643. 10.1037/amp0000660. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Roberti JW, Harrington LN, Storch EA. Further psychometric support for the 10-item version of the perceived stress scale. Journal of College Counseling. 2006;9(2):135–147. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1882.2006.tb00100.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rudenstine S, McNeal K, Schulder T, Ettman CK, Hernandez M, Gvozdieva K, Galea S. Depression and anxiety during the covid-19 pandemic in an urban, low-income public university sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2021 doi: 10.1002/jts.22600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F, Marín G, Otero-Sabogal R, Marín BV, Perez-Stable E. Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn't? Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9(4):397–412. doi: 10.1177/07399863870094003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santabárbara J, Lasheras I, Lipnicki DM, Bueno-Notivol J, Pérez-Moreno M, López-Antón R, De la Cámara C, Lobo A, Gracia-García P. Prevalence of anxiety in the COVID-19 pandemic: An updated meta-analysis of community-based studies. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2021;109:14. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Teruel, D., Robles-Bello, M., & Valencia-Naranjo, N. (2021). Do psychological strengths protect college students confined by COVID-19 to emotional distress? the role of gender. Pers Individ Differ,171(3). 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Shanahan, L., Steinhoff, A.,Bechtiger, L., Murray, A. L., Nivette, A., Hepp, U., Ribeaud, D., & Eisner, M. (2020). Emotional distress in young adults during the covid-19 pandemic: Evidence of risk and resilience from a longitudinal cohort study. Psychological Medicine, 52(5), 824–833. 10.1017/S003329172000241X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasso AF, HisliSahin N, San Roman GJ. COVID-19 disruption on college students: Academic and socioemotional implications. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2021;13(1):9–15. doi: 10.1037/tra0000996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traunmüller, C., Stefitz, R., Schneider, M., & Schwerdtfeger, A. (2021). Resilience moderates the relationship between the psychological impact of COVID-19 and anxiety. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 10.1080/13548506.2021.1955137. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ungar, M., Brown, M., Liebenberg, L., Othman, R., Kwong, W. M., Armstrong, M., & Gilgun, J. (2007). Unique pathways to resilience across cultures. Adolescence, 42(166), 287–310. [PubMed]

- U.S. Census Bureau (2020). https://www.census.gov.

- Wang Z, Yang H, Yang Y, Liu D, Li Z, Zhang X, Shen D, Chen PL, Song WQ, Wang XM, Wu XB, Yang XF, Mao C. Prevalence of anxiety and depression symptom, and the demands for psychological knowledge and interventions in college students during COVID-19 epidemic: A large cross-sectional study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;275:188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, Lui LMW, Gill H, Phan L, Chen-Li D, Iacobucci M, Ho R, Majeed A, McIntyre RS. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;277:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1988;52(1):30–41. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset contains sensitive information and thus only partial data without sensitive information are available from the following link.

Item-level data without sensitive information can be obtained from the first author upon request.