This randomized clinical trial assesses the safety and efficacy of roflumilast foam, 0.3%, in adults with seborrheic dermatitis affecting the scalp, face, or trunk.

Key Points

Question

What is the efficacy and safety of once-daily roflumilast foam, 0.3%, in adult patients with seborrheic dermatitis?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 226 patients with seborrheic dermatitis, 73.8% of roflumilast-treated patients achieved Investigator Global Assessment success at week 8 compared with 40.9% in the vehicle group, a statistically significant difference. Roflumilast was well tolerated, with the rate of adverse events similar to that of the vehicle.

Meaning

These phase 2a data demonstrate that once-daily roflumilast foam, 0.3%, may be a viable nonsteroidal topical treatment of seborrheic dermatitis.

Abstract

Importance

Current topical treatment options for seborrheic dermatitis are limited by efficacy and/or safety.

Objective

To assess safety and efficacy of roflumilast foam, 0.3%, in adult patients with seborrheic dermatitis affecting the scalp, face, and/or trunk.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This multicenter (24 sites in the US and Canada) phase 2a, parallel group, double-blind, vehicle-controlled clinical trial was conducted between November 12, 2019, and August 21, 2020. Participants were adult (aged ≥18 years) patients with a clinical diagnosis of seborrheic dermatitis for a 3-month or longer duration and Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) score of 3 or greater (at least moderate), affecting 20% or less body surface area, including scalp, face, trunk, and/or intertriginous areas. Data analysis was performed from September to October 2020.

Interventions

Once-daily roflumilast foam, 0.3% (n = 154), or vehicle foam (n = 72) for 8 weeks.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcome was IGA success, defined as achievement of IGA score of clear or almost clear plus 2-grade improvement from baseline, at week 8. Secondary outcomes included IGA success at weeks 2 and 4; achievement of erythema score of 0 or 1 plus 2-grade improvement from baseline at weeks 2, 4, and 8; achievement of scaling score of 0 or 1 plus 2-grade improvement from baseline at weeks 2, 4, and 8; change in Worst Itch Numeric Rating Scale (WI-NRS) score from baseline; and WI-NRS success, defined as achievement of 4-point or greater WI-NRS score improvement in patients with baseline WI-NRS score of 4 or greater. Safety and tolerability were also assessed.

Results

A total of 226 patients (mean [SD] age, 44.9 [16.8] years; 116 men, 110 women) were randomized to roflumilast foam (n = 154) or vehicle foam (n = 72). At week 8, 104 (73.8%) roflumilast-treated patients achieved IGA success compared with 27 (40.9%) in the vehicle group (P < .001). Roflumilast-treated patients had statistically significantly higher rates of IGA success vs vehicle at week 2, the first time point assessed. Mean (SD) reductions (improvements) on the WI-NRS at week 8 were 59.3% (52.5%) vs 36.6% (42.2%) in the roflumilast and vehicle groups, respectively (P < .001). Roflumilast was well tolerated, with the rate of adverse events similar to that of the vehicle foam.

Conclusions and Relevance

The results from this phase 2a randomized clinical trial of once-daily roflumilast foam, 0.3%, demonstrated favorable efficacy, safety, and local tolerability in the treatment of erythema, scaling, and itch caused by seborrheic dermatitis, supporting further investigation as a nonsteroidal topical treatment.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04091646

Introduction

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that affects patients of all ages, with a global prevalence of 5% or greater.1,2,3,4 Cardinal features are erythematous, scaly, pruritic patches and plaques, with a yellowish, greasy appearance, affecting areas with abundant sebaceous glands, often accompanied by dyspigmentation in patients with darker skin.4,5 Seborrheic dermatitis can have deleterious effects on quality of life, particularly in patients with more severe disease.6

Treatment options for seborrheic dermatitis include topical antifungals, corticosteroids, and sulfur/sulfacetamide; topical calcineurin inhibitors are also used off label.4,7 Coal tar is less commonly used and is associated with safety concerns.1 Treatments are available as creams, lotions, ointments, foams, shampoos, gels, and solutions/topical suspensions.4,7,8 Corticosteroids are effective, but should not be used long term due to risk of atrophy, telangiectasia, acne, rosacea, and ocular toxic effects when used on the eyelid.9 Topical calcineurin inhibitors are not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat seborrheic dermatitis; however, efficacy and safety have been assessed in patients with severe facial seborrheic dermatitis.10,11 Topical calcineurin inhibitors are associated with short-term warmth and burning sensations, and labeling includes a warning for rare cases of lymphoma and skin cancer, although clinical data do not suggest higher risk compared with the general population.9 Scalp seborrheic dermatitis is often treated with shampoos containing antifungal agents, selenium sulfide, or zinc pyrithione.4,7,8 Nonpharmacologic treatments, such as prescription nonsteroidal medical device creams, may also be useful to treat erythema, scaling, and itching associated with seborrheic dermatitis.12

Phosphodiesterase (PDE) 4 inhibition may be effective for seborrheic dermatitis based on its capacity to suppress proinflammatory cytokines implicated in seborrheic dermatitis pathophysiology by elevating cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels.5,13 Limited evidence from case reports and a small clinical trial supported efficacy of the topical PDE4 inhibitor crisaborole and the oral PDE4 inhibitor apremilast, both used off label, for treatment of seborrheic dermatitis.14,15,16 Roflumilast is a selective, highly potent PDE4 inhibitor with between 25- and more than 300-fold greater potency than crisaborole or apremilast in vitro.17 An oral formulation of roflumilast is approved for treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.13,17,18 Topical roflumilast is under investigation for long-term management of various dermatologic conditions, including atopic dermatitis, scalp psoriasis, and chronic plaque psoriasis (approved July 29, 2022, by the US Food and Drug Administration).19,20,21,22 We present results of a phase 2a randomized clinical trial of roflumilast foam, 0.3%, for once-daily treatment of seborrheic dermatitis on scalp and nonscalp locations.

Methods

Study Design

This was a parallel-group, double-blind, vehicle-controlled randomized clinical trial of once-daily roflumilast foam, 0.3%, for treatment of seborrheic dermatitis, conducted at 24 sites in the US and Canada. The study protocol and statistical analysis plans are in Supplements 1 and 2. Eligible patients were adults (aged ≥18 years) with clinical diagnosis of seborrheic dermatitis of a 3-month or greater duration, Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) score of 3 or greater, and affecting 20% or less body surface area (BSA), including the scalp, face, trunk, and/or intertriginous areas (eFigure 1 in Supplement 3). Patients had to discontinue topical antifungals, corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, sulfur-based treatments, medical devices, crisaborole, azelaic acid, or metronidazole 2 or more weeks before randomization (additional excluded medications are in eTable 1 in Supplement 3). Nonmedicated emollients, moisturizers, and sunscreens were allowed once daily as normally used by patients and applied 3 or more hours after application of the investigational product to untreated areas only.

Patients were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to roflumilast foam, 0.3%, or a vehicle foam. Assignment to treatment group was based on an interactive response technology system using a computer-generated randomization list generated by an unblinded statistician not involved in the trial and stratified by study site and baseline disease severity. The study design included an initial screening period (up to 4 weeks), randomization, 8-week treatment phase, and follow-up phase of 1 week. At week 8, patients who met eligibility requirements were given the option to enroll in an open-label, single-arm, long-term safety extension of the current trial.

Roflumilast foam is uniquely formulated to contain 0.3% roflumilast in an emollient, water-based (65% water) foam without fragrances, propylene glycol, polyethylene glycol, isopropyl alcohol, or ethanol. The foam has a propellant that dissipates rapidly when applied. Vehicle foam was identical to roflumilast foam, 0.3%, without the active ingredient. Each patient received blinded, uniquely numbered kits, each containing 2 blinded, 60-g canisters of the assigned product. The number of kits dispensed to each patient was based on BSA involvement.

Study staff instructed patients how to apply the treatment foam at the randomization (baseline) visit. Investigational product was applied to seborrheic dermatitis lesions as a thin film and rubbed in thoroughly but gently until the product disappeared. The foam was self-administered once daily, in the evening 20 or more minutes before going to bed, except when treatment was applied at the study site on day 0 and week 2. For scalp lesions, treatment was applied when the skin and hair were dry, with special attention given to ensure the treatment was applied to scalp skin and not rubbed off on hair. Patients were to maintain treatment for the duration of the trial regardless of whether treatable areas of seborrheic dermatitis cleared. The study was conducted in accordance with ethical principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki and International Council for Harmonisation tripartite guideline. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients at screening prior to trial enrollment. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

End Points

The primary efficacy end point was IGA success, defined as achievement of IGA score of clear (0) or almost clear (1) plus 2-grade improvement from baseline (scale: 0 [clear] to 4 [severe]; eTable 2 in Supplement 3) at week 8. As baseline included patients with moderate (3) and severe (4) disease, the end point is referred to as IGA score of 0 or 1, as the 2-grade improvement is required to meet the end point. Secondary end points included IGA success at weeks 2 and 4; achievement of overall assessment of erythema score of 0 or 1 (scale: 0 [none] to 3 [severe]) plus 2-grade improvement from baseline (erythema success); achievement of overall assessment of scaling score of 0 or 1 (scale: 0 [none] to 3 [severe]) plus 2-grade improvement from baseline (scaling success); change from baseline on the Worst Itch Numeric Rating Scale (WI-NRS; scale 0 [no itch] to 10 [worst imaginable itch]); and WI-NRS success, defined as achievement of a 4-point or greater WI-NRS score improvement from baseline in patients with baseline score of 4 or greater. Safety end points included incidence of adverse events (AEs), clinical laboratory parameters, changes in vital signs, Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale (PHQ-8), and Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). Local tolerability at application sites was assessed by investigators (prior to study drug application) and patients (recall of their experience 10-15 minutes after application of study drug) at baseline and weeks 4 and 8. Hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation were assessed by investigators at each visit on 4-point scales (scale: 0 [none] to 3 [severe]). Demographic information was collected for each patient, including gender, age, race, and ethnicity according to categories required by regulatory agencies.

Statistical Analysis

A sample size of 184 participants provided approximately 90% power to detect an active response of 58.5% or greater, assuming 159 participants completed the study and vehicle response of 30%, based on 2-group χ2 test of equal proportions (without continuity correction), using a 2-sided α of .10. The intention-to-treat (ITT) population included all randomized patients, while the modified ITT (mITT) population included all randomized patients except patients who missed the week-8 IGA assessment due to COVID-19 disruption. The primary efficacy end point was analyzed using a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (CMH) test stratified by study site and baseline disease severity. Statistical significance was concluded at the 10% significance level (2-sided). The primary efficacy analysis was based on the mITT population and repeated for the ITT population. Missing IGA scores were imputed using multiple imputation for CMH test.

Secondary end points of IGA success (weeks 2 and 4), erythema success, scaling success, and WI-NRS success were analyzed using the CMH test, similar to the primary end point. Change and percentage change from baseline in WI-NRS score were analyzed using analysis of covariance with independent variables of treatment, study site, baseline IGA, and baseline value of the respective scale. All secondary efficacy analyses were performed using the mITT and ITT populations except WI-NRS success, which was based on the subset of the ITT population with baseline WI-NRS score of 4 or greater. Percentage of patients satisfying response criteria and the treatment difference in percentage were estimated with observed data, and 95% CIs were calculated using the Wilson method. Analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

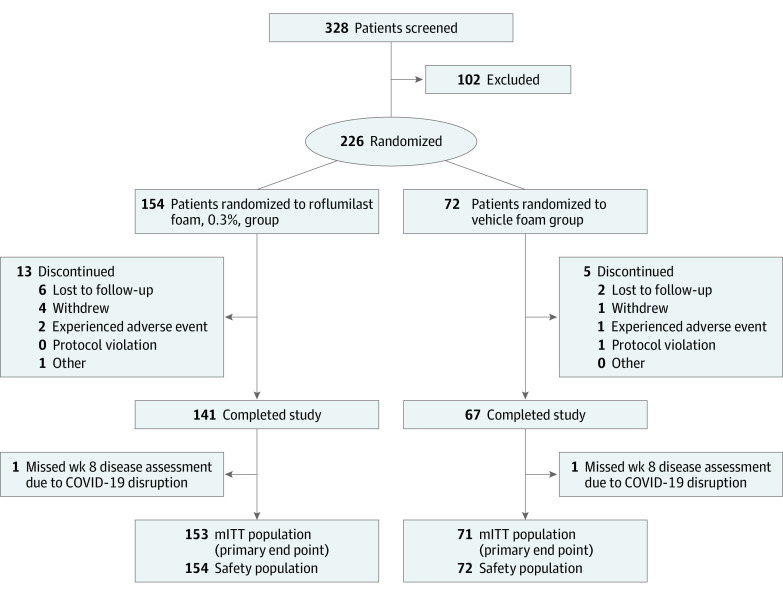

A total of 328 patients were screened, and 226 patients (mean [SD] age, 44.9 [16.8] years; 116 men, 110 women) were randomized to roflumilast foam (n = 154) or vehicle foam (n = 72; Figure 1). Most patients (208 of 226 [92.0%]) completed the study. Only 2 (1.3%) roflumilast-treated patients discontinued due to AEs, compared with 1 (1.4%) vehicle-treated patient. Additionally, 2 patients (1.3%) missed the IGA assessment at week 8 due to COVID-19 disruption and were excluded from the mITT population (n = 224).

Figure 1. Patient Flow Diagram.

mITT indicates modified intention-to-treat.

Treatment groups were well balanced for demographic and baseline disease characteristics (Table 1). More than 90% of patients had moderate severity of seborrheic dermatitis (IGA score of 3) at baseline, approximately 90% had a moderate score for erythema, and slightly more than 80% had a moderate score for scaling. Mean WI-NRS scores were slightly less than 6 in both groups. Mean percentage BSA affected was 3.3% in the roflumilast group and 3.0% in the vehicle group. More roflumilast-treated patients than vehicle-treated patients presented with facial involvement (64.9% vs 50.0%).

Table 1. Baseline Demographic and Disease Characteristics (Safety Population).

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Roflumilast foam, 0.3% (n = 154) | Vehicle foam (n = 72) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 45.3 (17.0) | 44.2 (16.3) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 78 (50.6) | 32 (44.4) |

| Male | 76 (49.4) | 40 (55.6) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 29 (18.8) | 16 (22.2) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 125 (81.2) | 56 (77.8) |

| Race | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (0.6) | 0 |

| Asian | 7 (4.5) | 1 (1.4) |

| Black or African American | 17 (11.0) | 6 (8.3) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0 | 0 |

| White | 123 (79.9) | 62 (86.1) |

| Othera | 1 (0.6) | 2 (2.8) |

| >1 Race | 5 (3.2) | 1 (1.4) |

| BSA affected, mean (SD), % | 3.3 (2.51) | 3.0 (2.11) |

| Baseline IGA (scale: 0-4) | ||

| 3 (Moderate) | 141 (91.6) | 69 (95.8) |

| 4 (Severe) | 13 (8.4) | 3 (4.2) |

| Baseline erythema (scale: 0-3) | ||

| 2 (Moderate) | 135 (87.7) | 66 (91.7) |

| 3 (Severe) | 19 (12.3) | 6 (8.3) |

| Baseline scaling (scale: 0-3) | ||

| 2 (Moderate) | 130 (84.4) | 58 (80.6) |

| 3 (Severe) | 24 (15.6) | 14 (19.4) |

| WI-NRS | ||

| Mean (SD) | 5.8 (2.7) | 5.7 (2.3) |

| Median (range) | 6.0 (0-10) | 6.0 (0-10) |

| Patients with baseline score ≥4 | 125 (81.2) | 59 (81.9) |

| Facial involvement | 100 (64.9) | 36 (50.0) |

Abbreviations: BSA, body surface area; IGA, Investigator Global Assessment; WI-NRS, Worst Itch Numeric Rating Scale.

Patients selected “other” when the patient did not feel that their race fit within 1 of the selected categories. The 3 patients entered the following into the free-text field: mixed race, Arabic, Trinidadian.

Efficacy

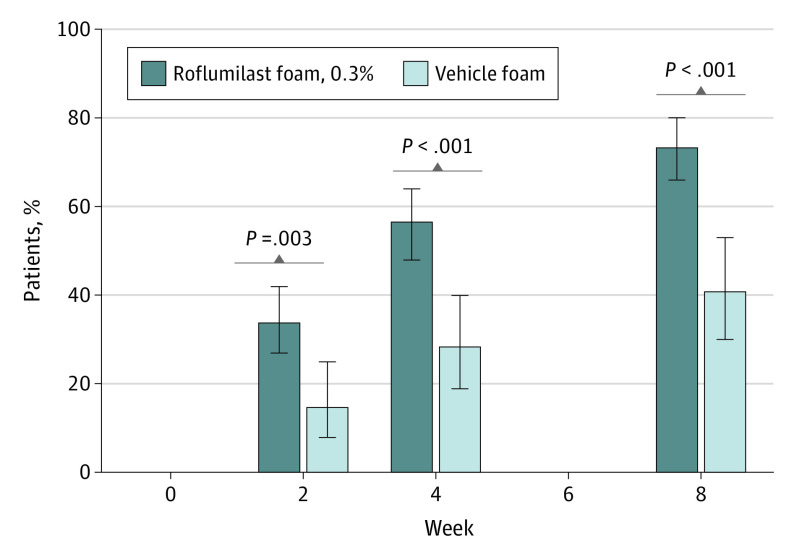

For the primary end point of IGA score of 0 or 1 at week 8, a statistically significant higher number of roflumilast-treated patients (104 [73.8%]) achieved IGA success compared with vehicle-treated patients (27 [40.9%]; absolute difference, 32.8% [95% CI, 18.5%-45.7%]; P < .001; Figure 2). The small number of patients with severe disease at baseline showed similar results, with 6 of 10 roflumilast-treated patients achieving IGA score of 0 or 1 vs 0 of 3 vehicle-treated patients. At week 8, 50 (35.5%) roflumilast-treated patients achieved IGA of clear, and 54 (38.3%) achieved IGA of almost clear, compared with 10 (15.2%) and 17 patients (25.8%), respectively, in the vehicle group. Differences in percentages of patients achieving IGA score of 0 or 1 at week 2 (the first posttreatment assessment) and week 4 were statistically significant in favor of roflumilast (week 2: 33.8% vs 14.7%; absolute difference, 19.1% [95% CI, 6.6%-29.3%]; P = .003; week 4: 56.6% vs 28.4%; absolute difference, 28.3% [95% CI, 14.0%-40.5%]; P < .001; Figure 2).

Figure 2. Percentage of Patients Achieving IGA Successa.

aInvestigator Global Assessment (IGA) success = clear or almost clear (on a scale of 0 [completely clear] to 4 [severe]). Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

A statistically significant increase in percentages of patients achieving erythema success was found among roflumilast-treated patients compared with vehicle-treated patients (week 2: 22.5% vs 5.9%; absolute difference, 16.6% [95% CI, 6.4%-24.8%]; week 4: 35.7% vs 10.4%; absolute difference, 25.2% [95% CI, 13.1%-34.9%]; week 8: 44.7% vs 21.2%; absolute difference, 23.5% [95% CI, 9.6%-35.0%]; P ≤ .006 for all time points; eFigure 2 in Supplement 3). A statistically significant increase in the percentage of roflumilast-treated patients achieving an erythema score of 0 was also observed at all time points (week 2: 16.6% vs 5.9%; absolute difference, 10.7% [95% CI, 1.0%-18.3%]; week 4: 32.2% vs 10.4%; absolute difference, 21.7% [95% CI, 9.8%-31.3%]; week 8: 43.3% vs 19.7%; absolute difference, 23.6% [95% CI, 9.9%-34.9%]; eFigure 2 in Supplement 3). Patients treated with roflumilast foam, 0.3%, demonstrated a greater mean (SD) change from baseline erythema score at weeks 2, 4, and 8 (−1.0 [0.73], −1.3 [0.73], and −1.4 [0.78], respectively) compared with that observed in vehicle-treated patients (−0.4 [0.65], −0.7 [0.67], and −0.8 [0.85], respectively; P < .001 for each week).

Similar results were observed for scaling success, with statistically significant differences favoring roflumilast at all time points (week 2: 26.5% vs 14.7%; absolute difference, 11.8% [95% CI, −0.3% to 21.8%]; week 4: 41.3% vs 21.0%; absolute difference, 20.4% [95% CI, 6.8%-31.8%]; week 8: 56.0% vs 27.2%; absolute difference, 28.8% [95% CI, 14.4%-41.0%]; P ≤ .08; eFigure 3 in Supplement 3). A statistically significant increase in percentages of roflumilast-treated patients achieving a scaling score of 0 occurred at all time points (week 2: 22.5% vs 8.8%; absolute difference, 13.7% [95% CI, 2.8%-22.4%]; week 4: 37.8% vs 14.9%; absolute difference, 22.8% [95% CI, 10.0%-33.3%]; week 8: 49.6% vs 24.2%; absolute difference, 25.4% [95% CI, 11.3%-37.3%]; eFigure 3 in Supplement 3). Patients treated with roflumilast foam, 0.3%, demonstrated a greater mean (SD) change from baseline scaling score at weeks 2, 4, and 8 (−1.0 [0.77], −1.3 [0.76], and −1.5 [0.75], respectively) compared with vehicle-treated patients (−0.6 [0.78], −0.8 [0.81], and −1.0 [0.83], respectively; P < .001 for each week).

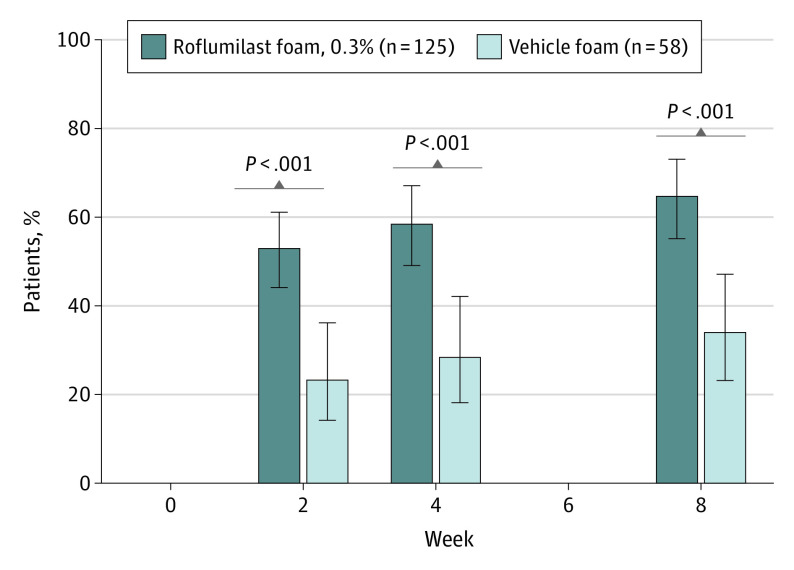

Patients receiving roflumilast experienced greater improvements in WI-NRS score compared with those receiving the vehicle foam. At week 2, mean (SD) change from baseline in the roflumilast group was −3.0 (2.8), a 47.2% (51.7%) decrease, vs −1.7 (2.1) with vehicle, a 30.9% (40.1%) decrease. Change at week 4 in the roflumilast group was −3.5 (2.7), a reduction of 56.7% (44.6%), and −1.9 (2.2), a reduction of 35.7% (39.9%), for the vehicle group. At week 8, mean (SD) change was −3.7 (2.8) for the roflumilast group and −2.0 (2.4) for the vehicle group, reductions of 59.3% (52.5%) and 36.6% (42.2%), respectively (P < .001). The percentage of patients who achieved WI-NRS success was greater in the roflumilast group at weeks 2, 4, and 8 (Figure 3). At week 8, 73 (64.6%) roflumilast-treated patients achieved WI-NRS success compared with 18 (34.0%) vehicle-treated patients (absolute difference, 30.6% [95% CI, 14.4%-44.6%]).

Figure 3. Percentage of Patients Achieving WI-NRS Success Among Patients With Baseline WI-NRS Score of 4 or Greatera.

aWorst Itch Numeric Rating Scale (WI-NRS) success = 4-point improvement from baseline WI-NRS score. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

For all efficacy analyses, outcomes for the ITT population were similar to those for the mITT population.

Safety

Roflumilast foam was well tolerated with a low rate of AEs (Table 2). Incidence of AEs was slightly higher in the roflumilast group compared with the vehicle group (37 of 154 [24.0%] vs 13 of 72 [18.1%]). Of 37 AEs reported in the roflumilast group, 35 were mild or moderate, while 2 were severe (hyperkalemia, migraine), both of which were considered unrelated to treatment (eTable 3 in Supplement 3). For the vehicle-treated group, 11 of the 13 AEs were mild or moderate, and the remaining 2 were severe (increased alanine aminotransferase level, anemia). Only 3 (1.9%) AEs in the roflumilast-treated group (application site pain, diarrhea, and insomnia) and 3 (4.2%) in the vehicle-treated group (application site pain, insomnia, and application site dysesthesia) were considered related to treatment by the investigator. Overall, only 3 patients had AEs of application site pain: 2 (1.4%) in the roflumilast-treated group and 1 (1.3%) in the vehicle-treated group.

Table 2. Adverse Events.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Roflumilast foam, 0.3% (n = 154) | Vehicle foam (n = 72) | |

| Any TEAE | 37 (24.0) | 13 (18.1) |

| Any treatment-related TEAE | 3 (1.9) | 3 (4.2) |

| Any serious AE | 0 | 0 |

| Discontinued study due to AEa | 2 (1.3) | 1 (1.4) |

| Most common TEAEs (>1.5% in any group), preferred term | ||

| Contact dermatitisb | 3 (1.9) | 2 (2.8) |

| Insomnia | 3 (1.9) | 1 (1.4) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 3 (1.9) | 0 |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Adverse events leading to discontinuation were application site pain, migraine, and dyspnea in the roflumilast-treated group and application site dysesthesia in the vehicle-treated group.

Contact dermatitis was reported to be unrelated to treatment in all cases, and no cases caused interruption of drug application; 2 cases were reported as “poison ivy rash” by investigators.

Two (1.3%) patients in the roflumilast group discontinued treatment due to AEs. One patient experienced both migraine (considered unrelated to treatment) and moderate application site pain, both of which resolved. The second patient discontinued due to dyspnea, which also resolved and was considered not treatment related. One (1.4%) patient in the vehicle group discontinued due to application site dysesthesia. No serious AEs or deaths occurred.

No clinically meaningful differences between groups were observed in changes in vital signs, PHQ-8, or C-SSRS, and laboratory values did not indicate any safety concerns. Investigator-assessed local skin irritation was rated as no evidence of irritation in 98% or greater of evaluations in both groups. On patient-rated local tolerability of roflumilast, scores were low (favorable) and similar to vehicle at all time points. Over 95% of patients reported no or mild sensation after applying roflumilast foam at week 4 and week 8, similar to vehicle.

Most patients were classified as having no hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation at any visit. At baseline, both hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation were disproportionately more common in non-White patients (hypopigmentation: 9 of 39 [23.1%]; hyperpigmentation: 7 of 41 [17.1%]) than in White patients (hypopigmentation: 2 of 180 [1.1%]; hyperpigmentation: 7 of 180 [3.9%]). Most patients with hypopigmentation at baseline (11 of 226 [4.9%]; 7 mild, 4 moderate) experienced full resolution (6 of 11; 54.5%) by week 8. Similarly, most patients with hyperpigmentation at baseline (14 of 226 [6.8%]; 10 mild, 4 moderate) experienced full resolution (11 of 14; 78.5%) by week 8. At week 8, new instances of hypopigmentation (n = 0) and hyperpigmentation (n = 3, all in White patients) were uncommon.

Discussion

This phase 2a randomized clinical trial assessed efficacy of a topical PDE4 inhibitor foam in patients with seborrheic dermatitis. Once-daily treatment with roflumilast foam, 0.3%, resulted in consistent improvements from baseline for key signs and symptoms of seborrheic dermatitis. Significantly more roflumilast-treated patients than vehicle-treated patients achieved the primary end point, IGA success, at week 8, with superiority achieved by the first postbaseline assessment at week 2. It is notable that 35.5% of patients achieved an IGA status of clear.

Similar results were observed for the secondary end point of WI-NRS success, as nearly two-thirds of roflumilast-treated patients who had baseline WI-NRS score of 4 or greater achieved a 4-point or greater improvement at week 8. This success rate for improvement in itch is noteworthy considering that the baseline WI-NRS score was relatively high and because itch is a major complaint among patients with seborrheic dermatitis.6,23

The high rate of response in vehicle-treated patients suggests the vehicle, which has a number of unique properties, has beneficial effects on seborrheic dermatitis. Roflumilast foam, 0.3%, is formulated with a water-based emollient vehicle nearly identical to the vehicle for roflumilast cream, 0.3%. This vehicle performed generally similarly to a leading ceramide-containing moisturizer across most assessments in a double-blinded, intraindividual study in patients with asteatotic eczema.24 Additionally, the unique emulsifier used does not act as a surfactant at skin temperature, and thus is not able to extract lipids from the skin.25 While the mechanism is speculative at this point, these results suggest the potential importance of the skin barrier in patients with seborrheic dermatitis.

Roflumilast foam, 0.3%, was well tolerated and demonstrated a favorable safety and tolerability profile. Rates of treatment-related treatment-emergent AEs, serious AEs, and AEs leading to discontinuation were low and generally comparable with vehicle. Few patients reported stinging, burning, application site reactions, or application site pain with either roflumilast or vehicle treatment. The tolerability profile demonstrates emollient properties of the vehicle formulated without excipients known to cause irritation, such as propylene glycol. This is important because of high rates of application site pain with the only other topical PDE4 inhibitor (crisaborole), which is approved for atopic dermatitis and has rates of application site pain between 13.8% and 31.7%.26,27,28 The low rates of application site pain in the current study suggest this is not a general feature of PDE4 inhibition. Additionally, in a trial evaluating efficacy and tolerability of tacrolimus, 1%, ointment in patients with severe facial seborrheic dermatitis, approximately 47% of patients reported burning.10 Local tolerability issues and adverse effects associated with other topical treatments of seborrheic dermatitis, such as corticosteroids, antifungals, and off-label use of calcineurin inhibitors, may limit their duration and usage.

The current standard of care for seborrheic dermatitis is to use multiple agents (usually an antifungal and anti-inflammatory).4 In addition to an anti-inflammatory effect, roflumilast inhibits yeast PDE activity, suggesting a possible additional antifungal effect.29

Limitations

A limitation of this study was the 8-week treatment period. A second limitation is the relatively small patient population enrolled in the current trial. A phase 3 randomized clinical trial (n = 457) should provide additional information about efficacy and safety of once-daily roflumilast foam, 0.3%, in patients with seborrheic dermatitis. Third, the number of patients with severe seborrheic dermatitis was small.

Conclusions

In this randomized clinical trial, nonsteroidal, once-daily roflumilast foam, 0.3%, demonstrated efficacy and safety results with favorable local tolerability in the treatment of erythema, scaling, and itch caused by seborrheic dermatitis. These results suggest roflumilast foam, 0.3%, has the potential to help address the unmet need for an effective, cosmetically tolerable, treatment for seborrheic dermatitis.

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. Excluded Medications and Treatments

eTable 2. Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) scale

eTable 3. Treatment Emergent Adverse Events by Severity

eFigure 1. Study Design

eFigure 2. Percentage of Patients Achieving Erythema Success and Erythema score of None (mITT Population)

eFigure 3. Percentage of Patients Achieving Scaling Success and Scaling Score of None (mITT Population)

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Berk T, Scheinfeld N. Seborrheic dermatitis. P T. 2010;35(6):348-352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheong WK, Yeung CK, Torsekar RG, et al. Treatment of seborrhoeic dermatitis in Asia: a consensus guide. Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;1(4):187-196. doi: 10.1159/000444682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dessinioti C, Katsambas A. Seborrheic dermatitis: etiology, risk factors, and treatments: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31(4):343-351. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tucker D, Masood S. Seborrheic dermatitis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adalsteinsson JA, Kaushik S, Muzumdar S, Guttman-Yassky E, Ungar J. An update on the microbiology, immunology and genetics of seborrheic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol. 2020;29(5):481-489. doi: 10.1111/exd.14091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peyrí J, Lleonart M; Grupo español del Estudio SEBDERM . Clinical and therapeutic profile and quality of life of patients with seborrheic dermatitis. Article in Spanish. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2007;98(7):476-482. doi: 10.1016/S1578-2190(07)70491-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark GW, Pope SM, Jaboori KA. Diagnosis and treatment of seborrheic dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(3):185-190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Del Rosso JQ. Adult seborrheic dermatitis: a status report on practical topical management. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4(5):32-38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wollenberg A, Christen-Zäch S, Taieb A, et al. ; European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis/EADV Eczema Task Force . ETFAD/EADV eczema task force 2020 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults and children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(12):2717-2744. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joly P, Tejedor I, Tetart F, et al. Tacrolimus 0.1% versus ciclopiroxolamine 1% for maintenance therapy in patients with severe facial seborrheic dermatitis: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(5):1278-1284. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warshaw EM, Wohlhuter RJ, Liu A, et al. Results of a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled efficacy trial of pimecrolimus cream 1% for the treatment of moderate to severe facial seborrheic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(2):257-264. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elewski B. An investigator-blind, randomized, 4-week, parallel-group, multicenter pilot study to compare the safety and efficacy of a nonsteroidal cream (Promiseb Topical Cream) and desonide cream 0.05% in the twice-daily treatment of mild to moderate seborrheic dermatitis of the face. Clin Dermatol. 2009;27(6)(suppl):S48-S53. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milakovic M, Gooderham MJ. Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibition in psoriasis. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2021;11:21-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen SR, Gordon SC, Lam AH, Rosmarin D. Recalcitrant seborrheic dermatitis successfully treated with apremilast. J Cutan Med Surg. 2020;24(1):90-91. doi: 10.1177/1203475419878162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu D, Chow P, Strawn S, Rajpara A, Wang T, Aires D. Chronic nasolabial fold seborrheic dermatitis successfully controlled with crisaborole. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17(5):577-578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peña SM, Oak ASW, Smith AM, Mayo TT, Elewski BE. Topical crisaborole is an efficacious steroid-sparing agent for treating mild-to-moderate seborrhoeic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(12):e809-e812. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong C, Virtucio C, Zemska O, et al. Treatment of skin inflammation with benzoxaborole phosphodiesterase inhibitors: selectivity, cellular activity, and effect on cytokines associated with skin inflammation and skin architecture changes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;358(3):413-422. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.232819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daliresp (roflumilast). Package insert. AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP; March 2020.

- 19.Gooderham MJ, Kircik LH, Zirwas M, et al. The safety and efficacy of roflumilast cream 0.15% and 0.05% in atopic dermatitis: phase 2 proof-of-concept study. European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV); October 28-November 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kircik LH, Moore A, Bhatia N, et al. Once-daily roflumilast foam 0.3% for scalp and body psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled phase 2b study. American Academy of Dermatology Virtual Annual Meeting; 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lebwohl M, Kircik LH, Moore A, et al. Roflumilast Cream, a once-daily, potent phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, in chronic plaque psoriasis patients: efficacy and safety from DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 phase 3 trials. EADV Spring Symposium; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lebwohl MG, Papp KA, Stein Gold L, et al. ; ARQ-151 201 Study Investigators . Trial of roflumilast cream for chronic plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(3):229-239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2000073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Araya M, Kulthanan K, Jiamton S. Clinical characteristics and quality of life of seborrheic dermatitis patients in a tropical country. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60(5):519. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.164410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Draelos ZD, Higham RC, Osborne D, Burnett P, Berk DR. Assessment of the vehicle for roflumilast cream compared to a commercially marketed, ceramide-containing moisturizing cream in patients with mild eczema. Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis (RAD) Virtual Conference; December 11-13, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berk D, Osborne DW. Krafft temperature of surfactants in vehicles for roflumilast and pimecrolimus cream and effects on skin tolerability. Society for Investigative Dermatology (SID) Annual Meeting; May 18-22, 2022; Portland, Oregon. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eucrisa (crisaborole). Package insert. Pfizer Inc; April 2020.

- 27.Clinical trial results: a phase 3B/4, multicenter, randomized, assessor blinded, vehicle and active (topical corticosteroid and calcineurin inhibitor) controlled, parallel group study of the efficacy, safety, and local tolerability of crisaborole ointment, 2% in pediatric and adult subjects (ages 2 years and older) with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. Accessed September 14, 2021. https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/trial/2018-001043-31/results

- 28.Pao-Ling Lin C, Gordon S, Her MJ, Rosmarin D. A retrospective study: application site pain with the use of crisaborole, a topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(5):1451-1453. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.10.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matencio A, García-Carmona F, López-Nicolás JM; Study of Yeast Lifespan . Characterization of resveratrol, oxyresveratrol, piceatannol and roflumilast as modulators of phosphodiesterase activity. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2020;13(9):225. doi: 10.3390/ph13090225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. Excluded Medications and Treatments

eTable 2. Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) scale

eTable 3. Treatment Emergent Adverse Events by Severity

eFigure 1. Study Design

eFigure 2. Percentage of Patients Achieving Erythema Success and Erythema score of None (mITT Population)

eFigure 3. Percentage of Patients Achieving Scaling Success and Scaling Score of None (mITT Population)

Data Sharing Statement