ABSTRACT

Treatment-resistant hypertension is common among patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD). In people with preserved kidney function, spironolactone is an evidence-based treatment. However, the risk for hyperkalemia limits its use in people with more advanced CKD. In the Chlorthalidone in Chronic Kidney Disease (CLICK) trial, 160 patients with stage 4 CKD and poorly controlled hypertension as confirmed by 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure (ABP) monitoring were randomly assigned to either placebo or chlorthalidone 12.5 mg daily in a 1:1 ratio stratified by prior loop diuretic use. The primary endpoint was the change in 24-hour systolic ABP from baseline to 12 weeks. The trial showed a treatment-induced reduction of 24-hour systolic ABP by 10.5 mmHg. Of the 160 patients randomized, 113 (71%) had resistant hypertension, of which 90 (80%) were on loop diuretics and the mean number of antihypertensive medications prescribed was 4.1 (standard deviation 1.1). In this subgroup of patients with treatment-resistant hypertension, the adjusted change from baseline to 12 weeks in the between-group difference in 24-hour systolic ABP was −13.9 mmHg (95% CI −19.4 to −8.4; P < .0001). Furthermore, compared with placebo, the urine albumin:creatinine ratio in the chlorthalidone group at 12 weeks was 54% lower (95% CI −65 to −40). Following randomization, hypokalemia, reversible increases in serum creatinine, hyperglycemia, dizziness, orthostatic hypotension and hyperuricemia occurred more frequently in the chlorthalidone group. Chlorthalidone has the potential to improve BP control among patients with advanced CKD and treatment-resistant hypertension. However, caution is advised when treating patients, especially when they are on loop diuretics.

Keywords: albuminuria, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, chronic renal failure, creatinine, diuretics, hypertension

Resistant hypertension is defined as blood pressure (BP) that remains above the desired goal despite treatment with optimally tolerated doses of three antihypertensive drugs from different classes, preferably including a diuretic [1, 2]. The prevalence of true resistant hypertension evaluated by 24-hour BP monitoring in a meta-analysis of 12 studies was found to be ≈10%, [3] suggesting that it affects >100 million people globally. Compared with the general population of people with hypertension, in people with chronic kidney disease (CKD), the prevalence of resistant hypertension is two to three times higher [4]. Patients with resistant hypertension are at an increased risk for cardiovascular events and end-stage kidney disease compared with those with controlled hypertension [5]. Yet few therapies exist for treating resistant hypertension, especially among people with CKD.

In the PATHWAY-2 study, spironolactone was shown to be more effective in lowering BP than bisoprolol, doxazosin or placebo [6]. However, spironolactone is associated with frequent adverse effects in those with CKD. For example, the European Society of Hypertension cautions its use among people with serum potassium >4.5 mEq/l and those with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <45 ml/min/1.73 m2 because of an increased risk of hyperkalemia [7]. In PATHWAY-2, patients with an eGFR <45 ml/min/1.73 m2 were excluded. In a 2019 trial, use of the potassium binding agent patiromer enabled the use of spironolactone in people with resistant hypertension and CKD [6]. However, even with the use of patiromer, ≈1 in 3 people experienced hyperkalemia (defined as serum K ≥5.5 mEq/l) within 12 weeks of treatment [6]; the frequency of hyperkalemia with spironolactone in the absence of patiromer was ≈3 in 5. Newer drugs, such as the non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist KBP-5074, are in development for the treatment of resistant hypertension in advanced CKD [8, 9]. Another non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, esaxerenone, is approved in Japan for treating hypertension. Still, the drug has a small but significant risk for hyperkalemia [10].

In the randomized, double-blind, controlled Chlorthalidone in Chronic Kidney Disease (CLICK) trial, we demonstrated that chlorthalidone could substantially reduce BP in those with stage 4 CKD [11]. CLICK recruited patients that had stage 4 CKD (eGFR <30 ml/min/1.73 m2 but ≥15 ml/min/1.73 m2) and uncontrolled hypertension, confirmed by 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) following a 2-week period during which antihypertensive medications were standardized. Uncontrolled hypertension was defined as average 24-hour ABPM ≥130 mmHg systolic or ≥80 mmHg diastolic while on antihypertensive treatment.

In a secondary analysis that included patients with treatment-resistant hypertension, i.e. receiving three or more antihypertensive medications but still those who had uncontrolled hypertension by 24-hour ABPM (≥130 mmHg systolic or ≥80 mmHg diastolic), we found that the adjusted change in the 24-hour systolic ABPM from baseline to 12 weeks was −12.6 mmHg in the chlorthalidone group and +1.3 mmHg in the placebo group, for a mean difference of −13.9 mmHg [95% confidence interval (CI) −19.4 to −8.4; P < .001); similar reductions were observed during the day and night [12]. The adjusted change in the 24-hour diastolic ABPM from baseline to 12 weeks had a mean difference of −5.8 mmHg (95% CI −9.0 to −2.6) between groups.

The percent change in the urinary albumin:creatinine ratio (UACR) from baseline was −44% in the chlorthalidone group and −5% in the placebo group at 4 weeks after the initiation of the assigned regimen [between-group difference −41% (95% CI −23 to −55)]; −44% and −4%, respectively, at 8 weeks [between-group difference −42% (95% CI −55 to −23)]; and −55% and −2%, respectively, at 12 weeks [between-group difference −54% (95% CI −65 to −40)]. Two weeks after the assigned regimen was discontinued, the percent change in UACR remained at −33% in the chlorthalidone group and −9% in the placebo group [between-group difference −33% (95% CI −51 to −8)].

From the time of randomization to the end of the trial, compared with placebo, increases in the serum creatinine level >25% from baseline were observed more frequently in the chlorthalidone group, especially when they were also on loop diuretics. The odds ratio associated with a ≥25% increase in creatinine was 1.1 (95% CI 0.1–18.3) among patients not on loop diuretics at baseline and 8.5 (95% CI 2.7–29.2) among those that were.

Taken together, in this secondary analysis of the CLICK trial, [11] restricted to patients with a diagnosis of resistant hypertension, stage 4 CKD and with a mean antihypertensive intake of 4.1 medications at baseline, chlorthalidone lowered clinic BP rapidly within 4 weeks and this was sustained over the 12 weeks of the trial. Seated clinic systolic BP was reduced 13.2 mmHg with chlorthalidone in 4 weeks, 14.5 mmHg at 8 weeks and 16.2 mmHg at 12 weeks. Thus 81% of the treatment effect was evident with the lowest dose of chlorthalidone (12.5 mg/day) in 4 weeks. This demonstrates the potency of the drug. Prior studies have reported that chlorthalidone is approximately three times as potent as hydrochlorothiazide [13]. Two weeks after stopping the drug, 76% of the treatment effect persisted, suggesting that the treatment effect is long-acting.

Although the treatment effect was similar among patients on loop diuretics (a 14.0-mmHg reduction in 24-hour systolic ABP) or not on loop diuretics (a 14.4-mmHg reduction), the acute effects on kidney function were remarkably different. Among those on placebo, the percentage of patients who had a reversible increase in serum creatinine of 25% was similar irrespective of loop diuretic use: 17% in those not on a loop diuretic versus 15% in those on a loop diuretic. However, this was in sharp contrast to those on chlorthalidone; the reversible increase in serum creatinine occurred in 18% of those not on loop diuretics versus 60% of those on a loop diuretic. Therefore the dosage of chlorthalidone should be minimized, especially in patients who are on loop diuretics. For the treatment of resistant hypertension in advanced CKD among patients receiving loop diuretics, we initiate chlorthalidone therapy at 6.25 mg/day or 12.5 mg every other day to minimize large decreases in systolic BP and kidney function.

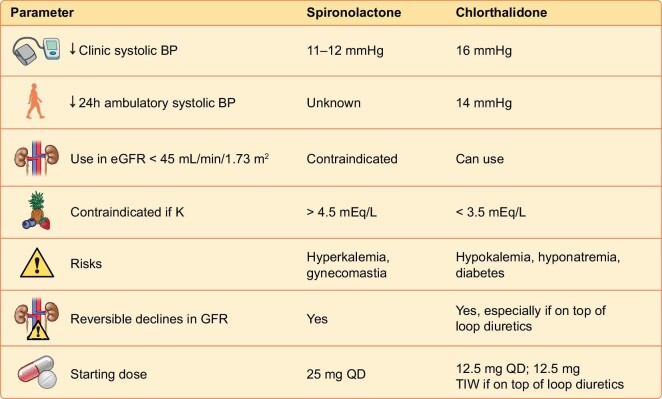

Spironolactone is the standard of care for the treatment of resistant hypertension [14]. A Cochrane meta-analysis reported that spironolactone doubled the risk of hyperkalemia [11 studies, 632 patients; relative risk (RR) 2.00 (95% CI 1.25–3.20)] and increased the risk of gynecomastia compared with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (or both) [4 studies, 281 patients; RR 5.14 (95% CI 1.14–23.23)] [15]. In a randomized trial of patients with resistant hypertension and an eGFR of 25–≤45 ml/min/1.73 m2, use of the potassium binding polymer patiromer enabled the use of spironolactone [16]. At week 12, 98 of 148 patients (66%) in the placebo group and 126 of 147 patients (86%) in the patiromer group remained on spironolactone [between-group difference 19.5% (95% CI 10.0–29.0); P < .0001]. But even with patiromer, approximately one in three patients administered spironolactone had experienced hyperkalemia, defined as potassium ≥5.5 mEq/l over 12 weeks. Given the difficulty of using spironolactone and its general underutilization, [17] we believe that chlorthalidone can serve as an attractive alternative in the treatment of resistant hypertension in advanced CKD. An important advantage of chlorthalidone over spironolactone is that the risk of hyperkalemia is essentially nonexistent. However, hypokalemia becomes a concern. Serum creatinine, BP, blood glucose and serum sodium would therefore require careful monitoring (Fig. 1).

Figure 1:

Efficacy, safety and dosing of spironolactone and chlorthalidone in CKD.

In summary, the resistant hypertension group in CLICK demonstrates that chlorthalidone effectively reduces both systolic and diastolic 24-hour ABP with stage 4 CKD, independent of loop diuretic use. The only guideline-recommended mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist for resistant hypertension is not widely used in advanced CKD due to the increased risk for hyperkalemia. In the USA, the smallest pill size for chlorthalidone is 25 mg. In this trial we used 12.5 mg once daily. Among patients on loop diuretics, the risk for reversible changes in serum creatinine might be lower if we use an even lower dose, such as 12.5 mg three times per week. Monitoring kidney function, electrolytes, glycemic control and BP, including orthostatic symptoms when prescribing this drug, would be essential to mitigate risk. Chlorthalidone appears to be an attractive option for the management of resistant hypertension in patients with advanced CKD. However, in patients with CKD who have low baseline K, the expectation of hyperkalemia is small and spironolactone might be an attractive option.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (R01 HL126903).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

R.A. reports personal fees and nonfinancial support from Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Akebia Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Vifor Pharma; personal fees from Lexicon and Reata; is a member of data safety monitoring committees for Vertex and Chinook; a member of steering committees of randomized trials for Akebia Therapeutics, Bayer and Relypsa; a member of adjudication committees for Bayer; has served as Associate Editor of the American Journal of Nephrology and Nephrology Dialysis and Transplantation and has been an author for UpToDate; and has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Veterans Administration.

REFERENCES

- 1. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: a Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2018;71:e13–115. 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Calhoun DA, Jones D, Textor S et al. Resistant hypertension: diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension 2008;51:1403–19. https://doi.org/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.189141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Noubiap JJ, Nansseu JR, Nyaga UF et al. Global prevalence of resistant hypertension: a meta-analysis of data from 3.2 million patients. Heart 2019;105:98–105. 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-313599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rossignol P, Massy ZA, Azizi M et al. The double challenge of resistant hypertension and chronic kidney disease. Lancet 2015;386:1588–98. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00418-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. De Nicola L, Gabbai FB, Agarwal R et al. Prevalence and prognostic role of resistant hypertension in chronic kidney disease patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:2461–7. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Williams B, MacDonald TM, Morant S et al. Spironolactone versus placebo, bisoprolol, and doxazosin to determine the optimal treatment for drug-resistant hypertension (PATHWAY-2): a randomised, double-blind, crossover trial. Lancet 2015;386:2059–68. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00257-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J 2018;39:3021–104. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bakris G, Pergola PE, Delgado B et al. Effect of KBP-5074 on blood pressure in advanced chronic kidney disease: results of the BLOCK-CKD Study. Hypertension 2021;78:74–81. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.17073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bakris G, Yang YF, Pitt B. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists for hypertension management in advanced chronic kidney disease: BLOCK-CKD Trial. Hypertension 2020;76:144–9. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ito S, Itoh H, Rakugi H et al. Antihypertensive effects and safety of esaxerenone in patients with moderate kidney dysfunction. Hypertens Res 2021;44:489–97. 10.1038/s41440-020-00585-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Agarwal R, Sinha AD, Cramer AE et al. Chlorthalidone for hypertension in advanced chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2021;385:2507–19. 10.1056/NEJMoa2110730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Agarwal R, Sinha AD, Tu W. Chlorthalidone for resistant hypertension in advanced chronic kidney disease. Circulation 2022;146:718–20. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.060167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Peterzan MA, Hardy R, Chaturvedi N et al. Meta-analysis of dose-response relationships for hydrochlorothiazide, chlorthalidone, and bendroflumethiazide on blood pressure, serum potassium, and urate. Hypertension 2012;59:1104–9. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.190637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nishizaka MK, Zaman MA, Calhoun DA. Efficacy of low-dose spironolactone in subjects with resistant hypertension. Am J Hypertens 2003;16:925–30. 10.1016/s0895-7061(03)01032-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bolignano D, Palmer SC, Navaneethan SD et al. Aldosterone antagonists for preventing the progression of chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;4:CD007004. 10.1002/14651858.CD007004.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Agarwal R, Rossignol P, Romero A et al. Patiromer versus placebo to enable spironolactone use in patients with resistant hypertension and chronic kidney disease (AMBER): a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2019;394:1540–50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32135-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. de Pinho NA, Levin A, Fukagawa M et al. Considerable international variation exists in blood pressure control and antihypertensive prescription patterns in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2019;96:983–94. 10.1016/j.kint.2019.04.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]