Seizures occur in one-third of glioblastoma patients, and in another third, seizures develop during the course of the disease.1 Nevertheless, the choice of antiseizure medication (ASM) remains challenging, and many patients need an increase in dosage or a polytherapy to achieve seizure control.2 We recently demonstrated that the DNA methylation subclass RTK II has a strong epileptogenic potential, as a high frequency of preoperative and follow-up seizures was observed.1 Here, we investigated the efficacy of levetiracetam to achieve seizure control and define therapeutic targets in RTK I, RTK II, and mesenchymal (MES) glioblastoma. We studied 201 patients with IDH-wildtype glioblastoma from 2 neurooncological centers (Hamburg and Bonn) and DNA methylation was analyzed using the Illumina EPIC array. Differential methylation analysis was performed, examining differentially methylated CpG sites of genes that are therapeutic targets of the most clinically relevant ASM. To further identify RNA expression of these genes, we queried the TCGA database to vertically integrate DNA methylation and RNA expression (n = 68). This study was approved by the medical ethics committee of the Hamburg chamber of physicians (PV4904). Informed written consent was obtained from all patients.

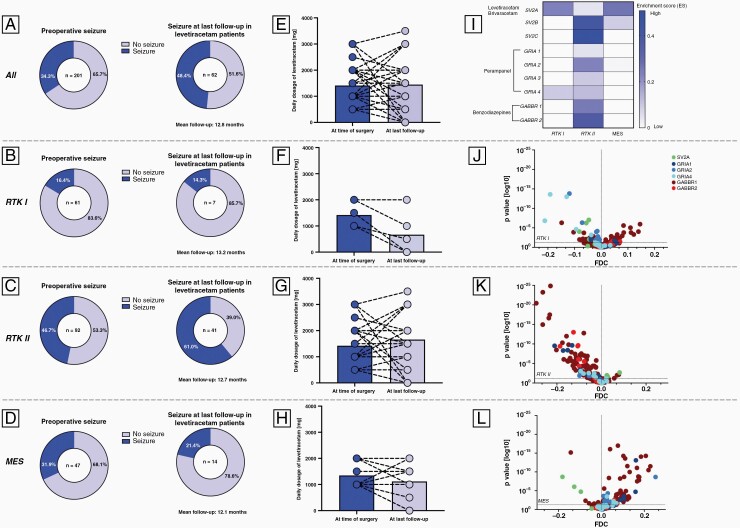

Preoperative seizures were observed in 69 (34.3%) patients. Of these, 62 (89.9%) patients were treated with levetiracetam achieving seizure freedom in 51.6% (Figure 1A). Subdivision into methylation subclasses revealed seizure freedom in 85.7% (6/7) of RTK I (Figure 1B) and 78.6% (11/14) of MES tumors (Figure 1D). In RTK II, only 39.0% (16/41) were seizure-free (Figure 1C). Additionally, the average daily dose of levetiracetam decreased in patients with RTK I (Figure 1F) and MES (Figure 1H) tumors during follow-up, whereas in RTK II tumors, the dose was increased (Figure 1G). These results raised the question of whether the low rates of seizure freedom in RTK II patients treated with levetiracetam were due to the high epileptogenic potential of this subclass or whether levetiracetam was the wrong ASM choice. To address this, we analyzed target receptor genes of levetiracetam (SV2A), perampanel (GRIA), and benzodiazepines (GABRR). RNA expression revealed enrichment of SV2A in RTK I and MES but not RTK II tumors (Figure 1I). However, SV2B and SV2C genes were upregulated in RTK II, highlighting its epileptogenic potential (Figure 1I). Among the differentially methylated CpG sites of the SV2A gene, significant hypomethylation was observed in RTK I and MES subclasses, whereas the RTK II subclass was significantly hypermethylated (Figure 1J–L). Further analysis revealed gene enrichment of GRIA1, GRIA2, and GRIA3 in the RTK II subclass (Figure 1I). These results obtained from RNA expression were reflected in methylation profiling, with CpG sites of GRIA genes significantly hypomethylated in the RTK I and RTK II subclasses (Figure 1J–K).

Figure 1.

(A)–(D) Visualization of rates of preoperative seizures and freedom or persistence of seizures at last follow-up in (A) all patients, (B) RTK I, (C) RTK II, and (D) MES patients. (E)–(H) In addition, the average daily dosage of levetiracetam is presented at the time of surgery and last follow-up for (E) all patients and each DNA methylation subclass (F: RTK I, G: RTK II, H: MES). (I) RNA expression is visualized for each DNA methylation subclass and volcano plots represent the differential methylation analysis of CpG sites of target genes in (J) RTK I, (K) RTK II, and (L) MES tumors.

The combination of clinical data, DNA methylation, and RNA expression presented here suggests that the efficacy of ASM in glioblastoma depends on the underlying tumor profiles and that methylation subclass-based selection of ASM could potentially improve the rate of seizure freedom. Our study shows satisfactory seizure freedom in RTK I and MES patients treated with levetiracetam. In contrast, RTK II tumors are recognized as a levetiracetam-resistant subclass. These findings are in line with recent results in PDX models of IDH-wildtype high-grade glioma.3 Instead of levetiracetam, the RTK II subclass could be targeted by AMPAR antagonists. Venkataramani et al. demonstrated the importance of AMPAR in glioma-associated epilepsy.4 Moreover, AMPAR gene expression was enriched in unconnected glioblastoma cells with neuronal and non-MES-like cell states.5 Another study demonstrated the reduction of extracellular glutamate levels in glioblastoma cell lines when exposed to Perampanel.6 However, the detailed biological rationale for this difference between the subclasses is currently unclear, and the small number of patients in the RTK I and MES subclasses must be mentioned, so validation in larger cohorts or clinical trials should be sought.

Our study provides evidence for DNA methylation-based anticonvulsant treatment in glioblastoma patients. According to our findings, levetiracetam achieves satisfactory seizure-free rates in RTK I and MES tumors, whereas perampanel may be the optimal ASM choice in RTK II tumors.

Contributor Information

Richard Drexler, Department of Neurosurgery, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Jennifer Göttsche, Department of Neurosurgery, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Thomas Sauvigny, Department of Neurosurgery, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Ulrich Schüller, Institute of Neuropathology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany; Department of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, Research Institute Children’s Cancer Center Hamburg, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany; Research Institute Children’s Cancer Center Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany.

Robin Khatri, Institute of Medical Systems Biology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany; Center for Biomedical AI, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Fabian Hausmann, Institute of Medical Systems Biology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany; Center for Biomedical AI, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Sonja Hänzelmann, Institute of Medical Systems Biology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany; Center for Biomedical AI, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany; III. Department of Medicine, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Tobias B Huber, III. Department of Medicine, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany; Hamburg Center for Translational Immunology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Stefan Bonn, Center for Biomedical AI, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany; III. Department of Medicine, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany; Hamburg Center for Translational Immunology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Dieter H Heiland, Department of Neurosurgery, Medical Center University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany.

Daniel Delev, Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital Aachen, Aachen, Germany.

Varun Venkataramani, Department of Neurology, University Hospital Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany.

Frank Winkler, Department of Neurology, University Hospital Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany.

Johannes Weller, Division of Clinical Neurooncology, Department of Neurology, University Hospital Bonn, Bonn, Germany.

Thomas Zeyen, Division of Clinical Neurooncology, Department of Neurology, University Hospital Bonn, Bonn, Germany.

Ulrich Herrlinger, Division of Clinical Neurooncology, Department of Neurology, University Hospital Bonn, Bonn, Germany.

Jens Gempt, Department of Neurosurgery, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Franz L Ricklefs, Department of Neurosurgery, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Lasse Dührsen, Department of Neurosurgery, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Funding

U.S. was supported by the Fördergemeinschaft Kinderkrebszentrum Hamburg. R.K. and F.H. are funded by the EU eRare project Maxomod. S.H. and T.B.H. received funding from SFB 1192 B8 and S.B. was supported by SFB 1192 C3.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Authorship statement

Study concept and design: R.D, F.L.R., T.S., and L.D. Acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation: R.D., J.G., T.S., R.K., and S.H. Statistical analysis: R.D., and R.K. Technical and material support: U.S., F.H., T.H., F.W., and S.B. TCGA integrative DNA methylation: D.H.H. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1. Ricklefs FL, Drexler R, Wollmann K, et al. DNA methylation subclass receptor tyrosine kinase II (RTK II) is predictive for seizure development in glioblastoma patients. Neuro Oncol. 2022;24(11):1886–1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Bruin ME, van der Meer PB, Dirven L, Taphoorn MJB, Koekkoek JAF.. Efficacy of antiepileptic drugs in glioma patients with epilepsy: a systematic review. Neurooncol Pract. 2021;8(5):501–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barron T, Yalçın B, Mochizuki A, et al. GABAergic Neuron-to-glioma synapses in diffuse midline gliomas. Neuroscience. 2022. doi: 10.1101/2021.11.04.467325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Venkataramani V, Tanev DI, Strahle C, et al. Glutamatergic synaptic input to glioma cells drives brain tumour progression. Nature. 2019;573(7775):532–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Venkataramani V, Yang Y, Schubert MC, et al. Glioblastoma hijacks neuronal mechanisms for brain invasion. Cell. 2022;185(16):2899–2917.e31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lange F, Weßlau K, Porath K, et al. AMPA receptor antagonist perampanel affects glioblastoma cell growth and glutamate release in vitro. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0211644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]