Abstract

Background

COVID-19 is known to be associated with a myriad of cardiovascular (CV) complications during acute illness, but the rates of readmissions for CV complications after COVID-19 infection are less well established.

Methods

The US Nationwide Readmission Database was utilized to identify COVID-19 admissions that occurred in the period from April 1st to November 30th, 2020, using International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition, Clinical Modification administrative claims.

Results

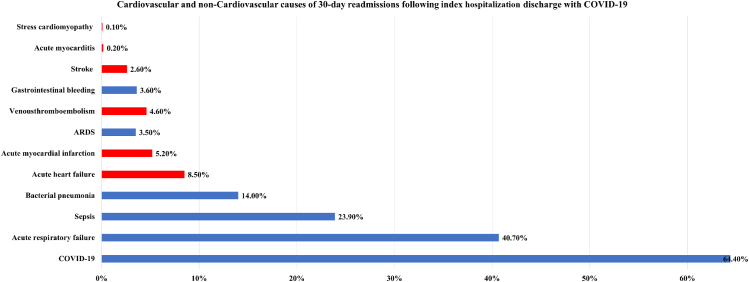

A total of 521,351 admissions for COVID-19 were identified. The all-cause 30-day readmission rate was 11.6% (n = 60,262). The incidence of CV-related readmissions was 5.1% (n = 26,725), accounting for 44.3% of all-cause 30-day readmissions. Both CV-related and non-CV-related readmissions occurred at a median of 7 days. Patients readmitted with CV causes had a higher comorbidity burden, with a median Charlson comorbidity score of 6. The most common CV cause of readmission was acute heart failure (8.5%), followed by acute myocardial infarction (5.2%). Venous thromboembolism and stroke during 30-day readmission occurred at rates of 4.6% and 3.6%, respectively. Stress cardiomyopathy and acute myocarditis were less frequent, with incidences of 0.1% and 0.2%, respectively. CV-related readmissions were associated with higher mortality, compared with non-CV-related readmissions (16.5% vs 7.5%, P < 0.01). Each 30-day CV-related readmission was associated with greater cost of care than each non-CV-related readmission ($13,803 vs $10,310, P < 0.01).

Conclusions

Among survivors of index COVID-19 admission, 44.7% of all 30-day readmissions were attributed to CV causes. Acute heart failure remains the most common cause of readmission after COVID-19, followed closely by acute myocardial infarction. CV causes of readmissions remain a significant source of mortality, morbidity, and resource utilization.

Résumé

Contexte

La COVID-19 est connue pour être associée à une myriade de complications cardiovasculaires (CV) durant la maladie en phase aiguë, mais les taux de nouvelles hospitalisations pour des complications CV après une infection par le virus causant la COVID-19 sont moins bien établis.

Méthodologie

La Nationwide Readmission Database des États-Unis a servi à recenser les hospitalisations pour la COVID-19 dans la période allant du 1er avril au 30 novembre 2020, à l’aide de la Classification internationale des maladies, 10e révision, modifications cliniques, selon les données administratives sur les demandes de remboursement.

Résultats

Au total, 521 351 hospitalisations pour la COVID-19 ont été recensées. Le taux de nouvelle hospitalisation à 30 jours, toutes causes confondues, a été de 11,6 % (n = 60 262). La fréquence de nouvelles hospitalisations liées à des causes CV a été de 5,1 % (n = 26 725), ce qui représente 44,3 % des nouvelles hospitalisations à 30 jours, toutes causes confondues. Les nouvelles hospitalisations, liées ou non liées à des causes CV, se sont produites à une médiane de sept jours. Les patients réadmis à l’hôpital pour des causes CV avaient un plus lourd fardeau de comorbidité, la valeur médiane du score de comorbidité de Charlson étant de 6. La cause CV la plus fréquente de nouvelle hospitalisation a été une insuffisance cardiaque aiguë (8,5 %), suivie d’un infarctus aigu du myocarde (5,2 %). Une thromboembolie veineuse et un accident vasculaire cérébral sont survenus durant une nouvelle hospitalisation dans les 30 jours à des taux de 4,6 % et de 3,6 %, respectivement. Une cardiomyopathie de stress et une myocardite aiguë ont été signalées à des fréquences moindres de 0,1 % et de 0,2 %, respectivement. Les nouvelles hospitalisations pour des causes CV ont été associées à une mortalité accrue comparativement aux nouvelles hospitalisations pour des causes autres que CV (16,5 % contre 7,5 %; p < 0,01). Les coûts des soins de santé associés à chaque nouvelle hospitalisation liée à une cause CV à 30 jours ont été plus élevés que pour chaque nouvelle hospitalisation non liée à une cause CV (13 803 $ contre 10 310 $; p < 0,01).

Conclusions

Chez les survivants de la première hospitalisation pour la COVID-19, 44,7 % des nouvelles hospitalisations à 30 jours ont été attribuées à des causes CV. Une insuffisance cardiaque aiguë demeure la principale cause de nouvelle hospitalisation après la COVID-19, suivie de près par un infarctus aigu du myocarde. Les causes CV des nouvelles hospitalisations sont encore une importante source de mortalité, de morbidité et d’utilisation des ressources.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is known to be associated with a myriad of acute cardiovascular (CV) complications, including acute myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure (HF), venous thromboembolism (VTE), stress cardiomyopathy, myocarditis, and cardiac arrhythmias.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 In-hospital CV outcomes during acute COVID-19 illness have been well described in existing literature6,7; however, data are scarce, specifically on CV outcomes of COVID-19 beyond the index hospitalization. Evidence in prior literature shows that readmissions attributed to CV causes remain a source of significant mortality, morbidity, and resource utilization.8,9 In the US, the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program evaluates hospital performance by excess readmission ratio, which is comprised of MI and HF.10 Yet no large-scale study has evaluated readmission rates due to CV causes following discharge from index COVID-19 admission in the US. Furthermore, current literature pertaining to all-cause readmission following COVID-19 has been limited to a few hospital systems or organizations and has not been reported in a diverse national database.11,12

Hence, we aimed to evaluate outcomes and predictors of 30-day CV readmissions in a US national cohort, among survivors of an index hospitalization for COVID-19, using the Nationwide Readmission Database (NRD) during the pandemic year 2020.

Methods

Study data

The NRD is sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and developed through the federal-state industry partnership.13,14 The database was developed for the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) and houses data on approximately 35 million annual weighted discharges. The discharge data available from 28 states represent 59.7% of the US population and 58.7% of inpatient hospitalizations. The NRD is an all-payer database that captures all admissions and readmissions in the US, facilitating the analysis of causes for readmissions, as well as resources utilization in terms of cost of care. Each patient is assigned a unique identifier code (NRD_VistLink) for tracing readmissions within a calendar year. The NRD days-to-event variable captures readmissions within a calendar year but not across different years.

Given the deidentified nature of the database, institutional review board approval and informed consent were not required for this study.

Study design and data selection

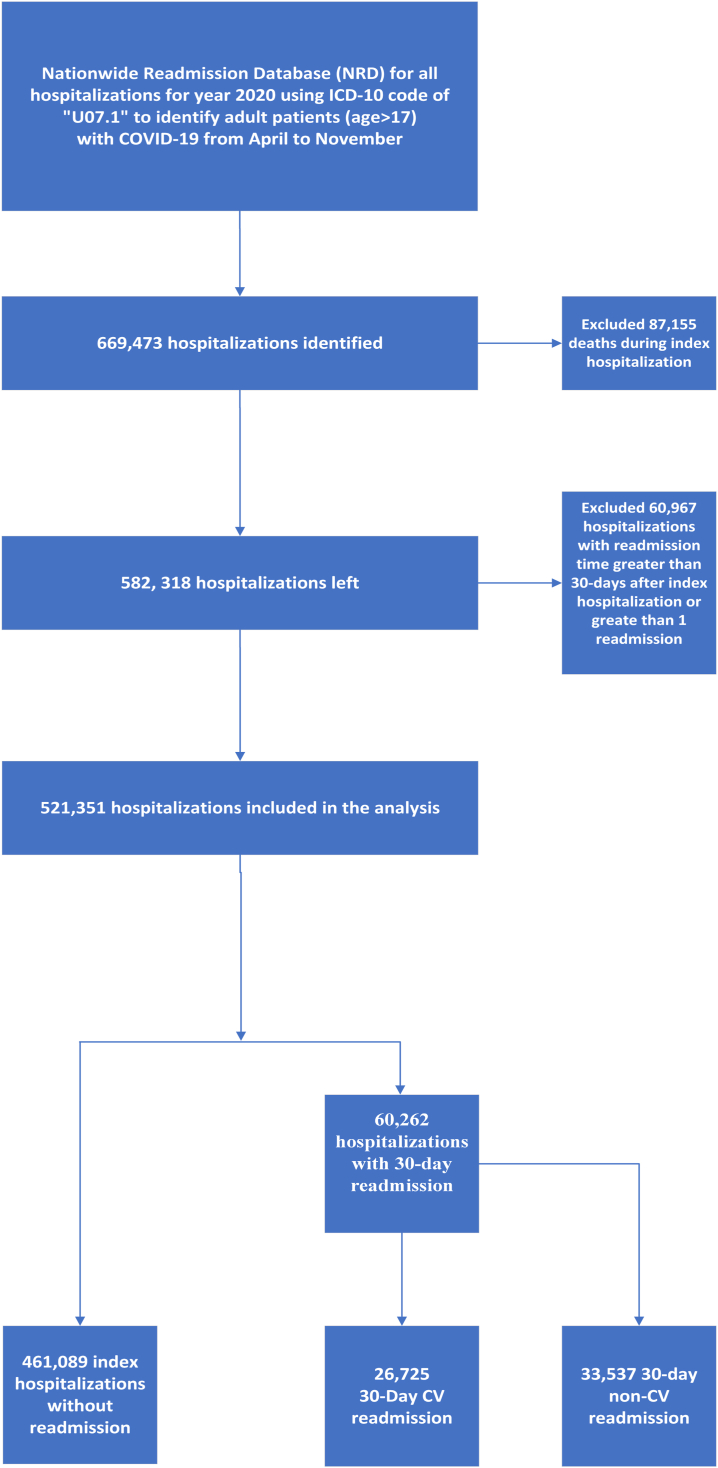

For the study, International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) administrative claims were used to identify patients with COVID-19 (ICD-10-CM code U07.1) from April 1st, 2020 to November 30, 2020. The NRD contains data on total hospital charges, which are the amounts billed by the hospital. However, charges differ from the actual costs, including the total expense of hospital services, counting utilities, wages, and supplies. To calculate the cost, the HCUP provides “cost-to-charge ratio” files that provide hospital-specific ratios or weighted-average ratios to supplement the original NRD file.15 The cost information was obtained from accounting reports of the participating hospitals collected by the Centres for Medicare and Medicaid, with missing values imputed when necessary. We determined the adjusted cost of care by multiplying the elements of the total charge provided by the NRD by the cost-to-charge ratios. A detailed flowchart of study methods is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. CV, cardiovascular; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition.

Study definitions

Index admissions were defined as patients admitted with COVID-19 who were discharged alive from the hospital. Index admissions were identified per calendar year from April to November 2020, and December admissions were excluded. Given that the NRD cannot track cases across different years, we had to exclude December COVID-19 admissions to allow for the analysis of 30-day readmission data. Readmission was defined as emergent nonelective or elective readmissions within 30 days of discharge. In patients who had multiple 30-day hospitalizations, only the first hospitalization was included in the analysis. Readmission mortality was defined as any death occurring in the hospital within 30 days of discharge from the index hospitalization (excluding deaths occurring outside the hospital). Median household annual income (US dollar) was categorized into 4 quartiles: 0-25th quartile ($1 to $55,999), 26-50th quartile ($56,000 to $70,999), 51-75th quartile ($71,000 to $93,999), and 76-100th quartile ($94,000+). Based on prior literature review and Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program definitions16 of the common cardiac complications, CV-related readmission was defined as a composite of acute HF (including acute myocarditis and stress cardiomyopathy), acute MI, acute stroke, VTE, and cardiac arrhythmia. All variables were defined by the ICD-10 codes used, and a complete list of all codes is given in Supplemental Table S1.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome was 30-day readmission rates for CV causes after index hospital discharge with COVID-19. Secondary outcomes included predictors of 30-day CV-related readmissions, and comparing the outcomes of CV-related vs non-CV-related readmissions in terms of in-hospital mortality, discharge disposition, in-hospital complications (acute kidney injury [AKI], AKI requiring dialysis, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy [PEG tube], tracheostomy), and resource utilization (length of stay [LOS] and cost of hospitalization). We used the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines to report the study findings; the checklist can be found in Supplemental Table S2.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using non-weighted data. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables were reported as medians with an interquartile range (IQR). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality of continuous data. Baseline characteristics were compared using Pearson’s χ2 testand Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables.

A multivariable logistic regression model was developed to compute independent predictors of 30-day CV-related readmission by using the enter regression method. The index hospitalization characteristics of patients readmitted with CV causes were compared with those of patients who were not readmitted (Supplemental Table S3). Variables included in the model included demographic variables (age and sex), socioeconomic variables (median household income and insurance status), comorbidities, complications during index admission, and medications (antiplatelet or anticoagulants). A complete list of variables included in the regression model is shown in Supplemental Table S3. A logistic regression model was constructed also, to compare outcomes of CV-related vs non-CV-related readmissions. Variables included in the model included demographic variables (age and sex), socioeconomic variables (median household income and insurance status), comorbidities, complications during index admission, and medications (antiplatelet or anticoagulants). A complete list of variables included in the regression model is shown in Table 1. R’s survival package17 was used to compute cumulative incidence of readmission and survivals using the log-rank test. A complete set of data was available for all variables except for primary expected payer (n = 1022; 0.1%) and median household income (n = 5963;1.1%). As the overall missing values were minimal, we used listwise deletion and did not include missing values in the logistic regression analysis. All missing values are reported in the baseline characteristics in Table 1 and Supplemental Table S3.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with index COVID-19 infection who were readmitted to the hospital within 30 days with cardiovascular (CV) vs non-CV causes

| Characterisitc | Non-CV-related readmission (n = 33,537) | CV-related readmission (n = 26,725) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y | 65 (52–76) | 73 (53–82) | < 0.01 |

| Age categories, y | |||

| ≤ 64 | 16,529 (49.3) | 7706 (28.8) | < 0.01 |

| 65–74 | 7801 (23.3) | 6806 (25.5) | < 0.01 |

| 75–84 | 6084 (18.1) | 7503 (28.1) | < 0.01 |

| ≥ 85 | 3123 (9.3) | 4710 (17.6) | < 0.01 |

| Female sex | 16,424 (49.0) | 11,444 (42.8) | < 0.01 |

| Socioeconomic characteristics | |||

| Primary payer | 19,155 (57.2) | 19,338 (72.5) | < 0.01 |

| Medicare | 6174 (18.4) | 2697 (10.1) | < 0.01 |

| Medicaid | 6205 (18.5) | 3525 (13.2) | < 0.01 |

| Private insurance | 793 (2.4) | 374 (1.4) | < 0.01 |

| Self-pay | 86 (0.3) | 43 (0.2) | < 0.01 |

| No charge | 1055 (3.2) | 708 (2.7) | < 0.01 |

| Others | 19,155 (57.2) | 19,338 (72.5) | < 0.01 |

| Missing | 69 (0.2) | 40 (0.1) | |

| Median household income percentile | |||

| 0–25 | 12,275 (37.0) | 9020 (34.1) | < 0.01 |

| 26–50 | 9158 (27.6) | 7477 (28.3) | < 0.01 |

| 51–75 | 6914 (20.9) | 5759 (21.8) | < 0.01 |

| 76–100 | 4802 (14.5) | 4191 (15.8) | < 0.01 |

| Missing | 388 (1.2) | 278 (1.0) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Charlson comorbidity index | 5 (3–6) | 6 (5–8) | < 0.01 |

| Charlson comorbidity index score > 6 | 7618 (22.7) | 12,032 (45.0) | < 0.01 |

| Anemias | 1783 (5.3) | 1683 (6.3) | < 0.01 |

| Hypertension | 22412 (66.8) | 21,481 (80.4) | < 0.01 |

| Preexisting heart failure | 4618 (13.8) | 11,571 (43.3) | < 0.01 |

| Coronary artery disease | 5642 (16.8) | 8625 (32.3) | < 0.01 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1681 (5.0) | 3100 (11.6) | < 0.01 |

| Diabetes | 14,800 (44.1) | 12,995 (48.6) | < 0.01 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 8187 (24.4) | 7960 (29.8) | < 0.01 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 776 (2.3) | 4929 (18.4) | < 0.01 |

| Valvular disease | 573 (1.7) | 1392 (5.2) | < 0.01 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1350 (4.0) | 1855 (6.9) | < 0.01 |

| Obesity | 6782 (20.2) | 5794 (21.7) | < 0.01 |

| Liver disease | 2367 (7.1) | 1670 (6.2) | < 0.01 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 8573 (25.6) | 9856 (36.9) | < 0.01 |

| End-stage kidney disease | 2928 (8.7) | 2673 (10.0) | < 0.01 |

| Prior MI | 1464 (4.4) | 2145 (8.0) | < 0.01 |

| Prior PCI | 1367 (4.1) | 1819 (6.8) | < 0.01 |

| Prior CABG surgery | 1000 (3.0) | 1661 (6.2) | < 0.01 |

| Preexisting pacemaker | < 11∗ | 1855 (6.9) | < 0.01 |

| Complications during the index admission | |||

| Pacemaker implanted during index hospitalization | < 11∗ | 65 (0.2) | < 0.01 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 983 (2.9) | 10,982 (41.1) | < 0.01 |

| Cardiac arrest | 418 (1.2) | 972 (3.6) | < 0.01 |

| Stress cardiomyopathy | 17 (0.1) | 37 (0.1) | < 0.01 |

| Acute myocarditis | 35 (0.1) | 69 (0.3) | < 0.01 |

| Acute kidney injury | 9013 (26.9) | 9334 (34.9) | < 0.01 |

| Respiratory failure | 12,916 (38.5) | 12,489 (46.7) | < 0.01 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 46 (0.1) | 201 (0.8) | < 0.01 |

| Vasopressor use | 398 (1.2) | 451 (1.7) | < 0.01 |

| Septic shock | 7317 (21.8) | 6214 (23.3) | < 0.01 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 2783 (8.3) | 3009 (11.3) | < 0.01 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 603 (1.8) | 1089 (4.1) | < 0.01 |

| Mechanical circulatory support during the index admission† | < 11∗ | 35 (0.1) | < 0.01 |

| Medications | |||

| Current use of antiplatelets | 1420 (4.2) | 1540 (5.8) | < 0.01 |

| Current use of anticoagulants | 2813 (8.4) | 7584 (28.4) | < 0.01 |

Values are n (%), or median (interquartile range), unless otherwise indicated.

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CV, cardiovascular; IQR, interquartile range; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Observations < 11 are not reported per Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project guidelines.

Mechanical circulatory support devices included intra-aortic balloon pump, Impella, percutaneous ventricular assist device, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).

For all analyses, a 2-tailed P-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 27 (IBM, Armonk, NY) and R software for Statistical Computing, version 4.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study population

A total of 521,351 index hospitalizations for COVID-19 were included in the analysis for the pandemic year 2020. Of the included cases, 461,089 did not get readmitted (Fig. 1). The all-cause readmission rate within 30 days of discharge was 11.6% (n = 60,262). The incidence of CV-related readmissions was 5.1% (n = 26,725), accounting for 44.3% of all-cause 30-day readmissions. The incidence of non-CV-related readmissions was 6.4% (33,537), accounting for 55.7% of all-cause readmissions. Of the patients who survived the index admission, the mortality rate during the episode of readmission at 30 days was 1.3%. Among CV-related readmissions, the in-hospital mortality rate was 0.8% of the total index-hospitalization survivors.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of those readmitted within 30 days for CV (n = 26,725) vs non-CV (n = 33,537) causes. Supplemental Table S3 shows the baseline characteristics of those readmitted within 30 days for CV causes (n = 26,725), compared to those who were not readmitted within 30 days after index hospitalization (n = 461,089). Patients with CV-related readmission had a higher median age of 73 years, compared with the median age of 65 years of patients with non-CV-related readmissions (P < 0.01; Table 1). Readmissions for both CV and non-CV causes occurred at a median of 7 days (IQR 3-15). The temporal trend of 30-day CV-related readmission rates during the study period is shown in Supplemental Figure S1.

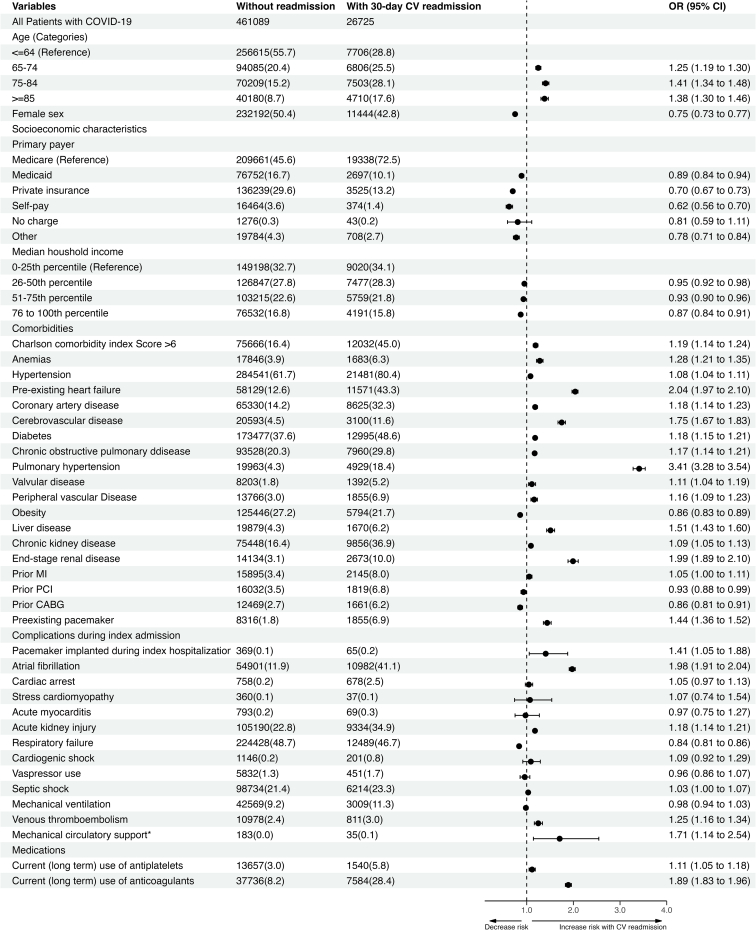

Predictors of 30-day CV-related readmission

The hospitalization characteristics of the 26,725 30-day readmissions for CV causes were compared with those of the 461,089 index hospitalization patients who did not get readmitted. Independent variables associated with 30-day CV-related readmission after index hospitalization discharge with COVID-19 included the following: Charlson Comorbidity score > 6 (odds ratio [OR] 1.19, 95% confidence interval [CI; 1.14-1.24]), hypertension (OR 1.08, 95% CI [1.04-1.11]), preexisting HF (OR 2.04, 95% CI [1.97-2.10]), coronary artery disease (OR 1.18, 95% CI [1.14-1.23]), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; OR 1.17, 95% CI [1.14-1.21]), pulmonary hypertension (OR 3.41, 95% CI [3.28-3.54]), atrial fibrillation (OR 1.98, 95% CI [1.91-2.04]), VTE on index admission (OR 1.25, 95% CI [1.16-1.34]), chronic kidney disease (CKD; OR 1.09, 95% CI [1.05-1.13]), and end-stage kidney disease (OR 1.99, 95% CI [1.88-2.10]). In contrast, female sex (OR 0.75, 95% CI [0.73-0.77]), private insurance (OR 0.70, 95% CI [0.67-0.73]), and high median household income (OR 0.87, 95% CI [0.84-0.91]) were associated with lower odds of readmission within a month after discharge from index COVID-19 hospitalization. A complete list of variables and their association with 30-day CV-related readmissions is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Independent predictors of 30-day hospital readmissions for cardiovascular (CV) causes. ∗Mechanical circulatory support devices included intra-aortic balloon pump, Impella (Abiomed, Danvers, MA) device, percutaneous ventricular assist device, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Adjusted odds ratio is based on multivariable logistic regression model adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic characteristics, median household income, comorbidities, complications during index admissions, and current (long-term) use of antiplatelets and anticoagulants. CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range; MI, myocardial infarction; OR, odds ratio; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

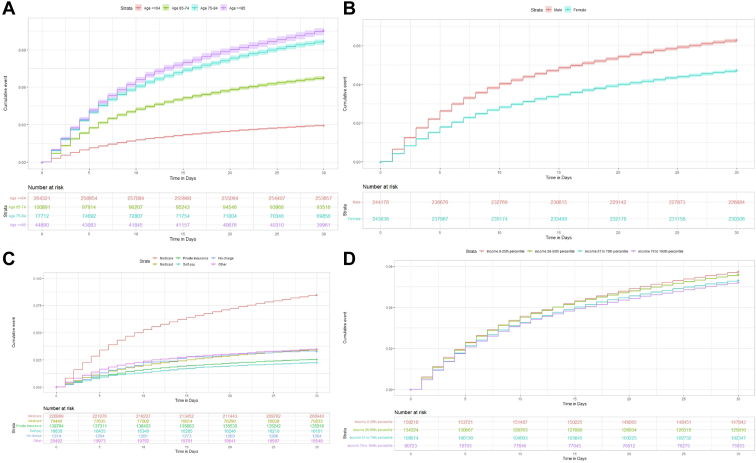

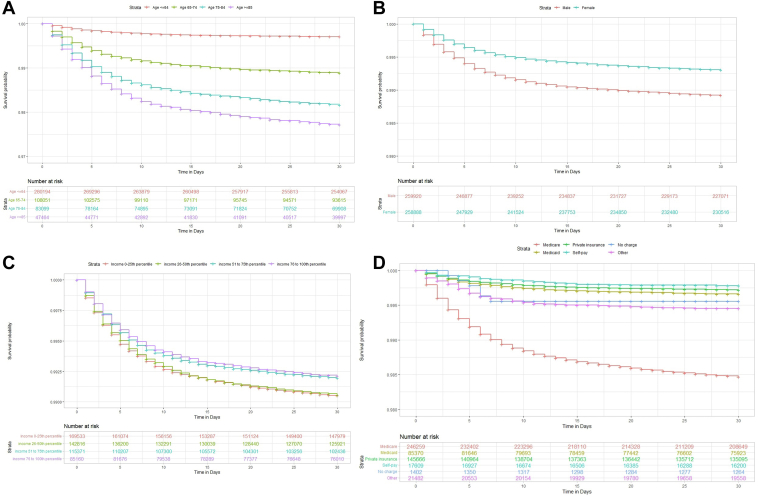

Cumulative incidence of 30-day readmission and 30-day readmission mortality by demographic variables and socioeconomic characteristics

The cumulative incidence of 30-day CV-related readmission was highest among those with the following characteristics: male sex, age > 84 years, lower quartile of income, and having Medicare as primary insurance (Fig. 3). Similarly, the cumulative survival rates concerning CV-related deaths were lowest for those with the following characteristics: male sex, age > 84 years, lowest quartile of income, and Medicare insurance (P log-rank < 0.01; Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence of 30-day hospital readmissions for cardiovascular causes. (A) The cumulative incidence curve shows increased cumulative incidence of readmissions among those aged > 85 years, compared to other age groups (P log-rank < 0.01). (B) The cumulative incidence curve shows increased cumulative incidence of readmissions among male patients, compared to female patients (P log-rank < 0.01). (C) The cumulative incidence curve shows increased cumulative incidence of readmissions among patients with Medicare as their primary insurance, compared to the incidence among patients with other types of insurance coverage (P log-rank < 0.01). (D) The cumulative incidence curve shows increased cumulative incidence of readmissions among patients in the lowest quartile of income, vs the incidence among those in other income quartiles (P log-rank < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Cumulative survival rates for 30-day mortality during readmission for cardiovascular causes. (A) Kaplan-Meier curve shows reduced survival rates among those aged > 85 years, compared to the rate among those in other age groups (P log-rank = < 0.01). (B) Kaplan-Meier curve shows reduced survival rates among male patients, compared to the rate among female patients (P log-rank = < 0.01). (C) Kaplan-Meier curve shows reduced survival rates among patients in the lower quartile of income, compared to the rates among those in other income groups (P log-rank = < 0.01) (D) Kaplan-Meier curve shows reduced survival rates among patients with Medicare as their primary insurance, compared to the rates among those in other insurance groups (P log-rank = < 0.01).

Cardiovascular and noncardiovascular causes of 30-day readmission

The most common CV cause of readmission was acute HF (8.5%), followed by acute MI (5.2%). VTE and stroke during the episode of 30-day readmission occurred at rates of 4.6% and 3.6%, respectively. Stress cardiomyopathy and acute myocarditis were less-frequent causes of CV-related readmissions, with an incidence of 0.1% and 0.2%, respectively. The incidence of cardiac arrhythmias was 31.6% among all readmissions. The most common non-CV cause of readmission was recurrent COVID-19, which occurred at a rate of 64.6%. Acute respiratory failure was seen in 40.7% of cases, and bacterial pneumonia in 14% of cases (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Causes of readmissions. Bar chart shows causes of readmissions among survivors of index COVID-19 hospitalization. Red denotes primary cardiovascular causes, Blue denotes primary noncardiovascular cause of readmission. ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; COVID-19: coronavirus disease-2019.

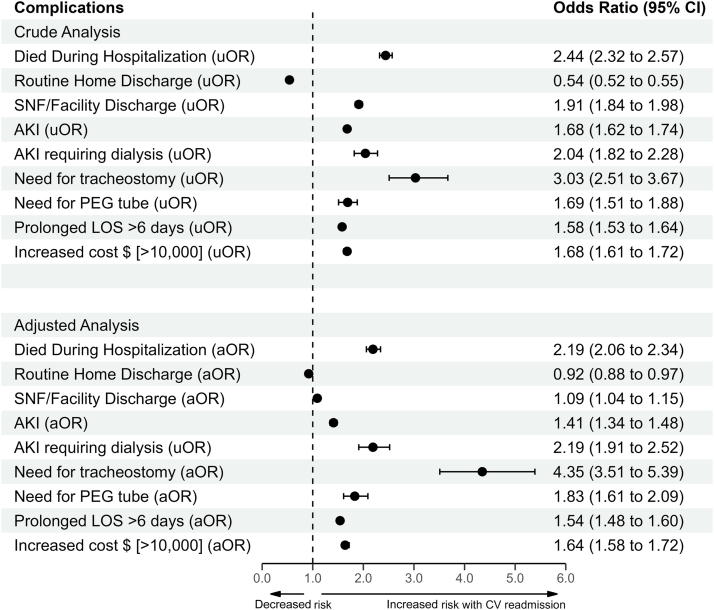

Outcomes of CV-related readmissions compared with non-CV-related readmissions

A total of 26,725 CV-related readmissions were compared with non-CV-related readmissions (n = 33,537). CV-related readmissions were associated with higher mortality, compared with readmissions for non-CV causes (16.5% vs 7.5%, P < 0.01). Similarly, more patients with HF readmissions were discharged to skilled nursing or rehab facilities than patients with non-CV-related readmission (32.7% vs 26.6%, P < 0.01). In addition, rates of AKI, AKI requiring dialysis, need for tracheostomy, and placement of PEG tubes were higher for patients with CV-related readmissions, compared with those readmitted for non-CV causes (Fig. 6, Table 2).

Figure 6.

Adjusted odds for in-hospital complications for cardiovascular (CV)-related vs non-CV-related readmissions. Adjusted odds ratio (aOR) is based on multivariable logistic regression model adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic characteristics, median household income, comorbidities, complications during index admissions, and current (long-term) use of antiplatelets and anticoagulants. AKI, acute kidney injury; CI, confidence interval; LOS, length of stay; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; SNF, skilled nursing facility; uOR, unadjusted odds ratio.

Table 2.

Hospital outcomes and resource utilization associated with 30-day readmissions for CV vs non-CV causes

| Non-CV readmission (n = 33,537) | CV readmission (n = 26,725) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Readmission outcomes, n (%) | |||

| Died during hospitalization | 2505 (7.5) | 4397 (16.5) | < 0.01 |

| Routine home discharge | 14,763 (44.0) | 7292 (27.3) | |

| SNF/facility discharge | 8924 (26.6) | 8736 (32.7) | < 0.01 |

| AKI | 8370 (25.0) | 9575 (35.8) | < 0.01 |

| AKI requiring dialysis | 487 (1.5) | 779 (2.9) | < 0.01 |

| Need for tracheostomy | 153 (0.5) | 367 (1.4) | < 0.01 |

| Need for PEG tube | 580 (1.7) | 771 (2.9) | < 0.01 |

| Resource utilization, median (IQR) | |||

| LOS, d | 5 (3-8) | 6 (3-11) | < 0.01 |

| Hospitalization cost, $ | $10,310 ($5836–$19,148) | $13,803 ($7601–$27,740) | < 0.01 |

AKI, acute kidney injury; CV, cardiovascular; IQR, interquartile range; LOS, length of stay; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

Resource utilization for CV-related readmissions, compared to that for non-CV-related readmissions

On average, each 30-day CV-related readmission was associated with a greater increase in the cost of care than non-CV-related readmission ($13,803 vs $10,310, P < 0.01). Similarly, LOS on readmission was significantly higher for CV-related readmissions at 6 days (IQR 3-11), compared with that of patients readmitted for non-CV causes at 5 days (IQR 3-8; Table 2).

Discussion

Our US nationwide analysis of COVID-19 index hospitalizations and 30-day readmissions during the pandemic year 2020 revealed the following principal findings: (i) the 30-day CV-related readmission rate following index COVID-19 hospitalization discharge with COVID-19 was 5.1%, accounting for 44.3% of all-causes 30-day readmissions. (ii) The most frequent CV complication following COVID-19 hospital discharge was acute HF followed by acute MI. (iii) Thrombotic complications, such as VTE, and cerebrovascular complications, such as stroke, occurred at rates of 4.6% and 2.6%, respectively. (iv) As opposed to non-CV-related readmissions, CV-related readmissions were associated with a 2-fold increased risk of death during the episode of the 30-day readmission. (v) CV-related readmissions posed a significant burden to the healthcare system, as they were associated with increased resource utilization in terms of the need for dialysis, PEG tube placement, tracheostomies, increased LOS, and the cost of hospitalization (Box 1).

Box 1: Clinical Perspective.

What is new?

-

•

We evaluated national US hospitalization data during the pandemic year 2020 and found that among survivors of index COVID-19 hospitalization, 44.3% of all 30-day readmissions were attributed to CV causes.

-

•

Acute HF remains the most common cause of CV-related readmission, with acute MI as the second-most-frequent cause.

-

•

CV causes of readmission remain a significant source of mortality, morbidity, and resource utilization.

What are the clinical implications?

-

•

Clinicians need to be vigilant about CV complications among individuals discharged from the hospital following hospitalization for COVID-19.

-

•

Our study stresses the importance of early discharge follow-up (within 1 week), with a special focus on vulnerable population groups, to prevent CV-related readmissions and associated morbidity.

-

•

Further studies are needed to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 vaccination on CV-related readmissions, mortality, and morbidity after COVID-19 infection.

CV-related readmission rates following discharge after COVID-19 hospitalization

Prior studies have shown that adverse events such as hospital readmissions and mortality among survivors of COVID-19 occur within 30 days of discharge.18 However, prior literature reported variable all-cause readmission rates after COVID-19 hospitalization, ranging between 5% and 20%, with large variability in study design as well as study population.11,19, 20, 21, 22 For example, Donnelly and colleagues reported data from a US cohort from the Veterans Affairs (VA) health system comprising 2179 index COVID-19 cases, of whom 19.9% were readmitted within 60 days of discharge.11 On the other hand, a prospective study from Brazil reported readmission rates of 6.7% from 1589 patients.19 Data from New York state comprising 1666 patients reported an all-cause 30-day readmission rate of 5%.20 Furthermore, data are scarce on what burden of readmissions following COVID-19 was due to CV causes. Using a national US dataset, our study has now demonstrated an all-cause readmission rate of 11% within 30 days of a COVID-19 hospitalization. Our study has a noteworthy advantage over previous reports, as we used a US population that includes all individuals, without geographic, demographic, or healthcare system restrictions. This feature makes our analysis important, as our findings are widely generalizable and representative of the US population. Additionally, we found that approximately half of all readmissions were due to CV causes, which had not been reported previously in a national dataset from the US.

CV complications during 30-day readmission

Previous reports from the Veterans Affairs healthcare system in the US indicated that the most common cause of readmissions in addition to COVID-19, sepsis, and pneumonia, was HF.11 An established finding from the literature is that individuals are still at elevated risk of developing CV complications after discharge, even if they have completely recovered from their COVID-19 symptoms.23, 24, 25 A prior large Swedish study of 86,742 patients showed a significant association of COVID-19 with an approximately 3-fold higher risk of developing MI in the first week (OR 2.9, 95% CI 1.51-5.55) and a 2.5-fold risk in the second week (OR 2.53, 95% CI 1.29-4.94) after COVID-19 hospitalization.26 Similarly, a 3-fold higher risk of stroke was present in the first week following COVID-19 infection.26 Further, an association of VTE with COVID-19 has been well established, with some studies suggesting that the risk for VTE may remain high even 1 year after recovery from COVID-19.27,28 On the same note, acute myocarditis and stress cardiomyopathy also have been shown to have an association with COVID-19, with prior literature restricted to case reports and case series.1,29, 30, 31

Our study constitutes a significant addition to the existing literature by leveraging an all-payer national database to report rates of CV complications beyond the index admission within 30 days of discharge. We report that HF is a frequent cause of readmission, followed closely by MI. Similarly, thrombotic complications, such as VTE as well as stroke, are also seen in about 2%-4% of the patients. We also showed that the median time to readmission was 7 days, suggesting that this is a critical period for instituting preventive interventions against CV readmissions and complications.

Death during an episode of readmission for CV causes

Prior literature suggests that the postdischarge period following COVID-19 admission in high-risk individuals is a time of heightened patient vulnerability associated with increased odds of mortality.12 Estimates of the incidence of postdischarge mortality have been reported in the range of 1% to 20%.11,19,21 The reason for the variability in reporting of postdischarge mortality is due to variation in study design, sample size, and population of interest. In our study, the reported 30-day readmission mortality rate was 1.3%, which is similar to prior reported estimates. Moreover, we also reported that CV causes of readmissions contribute considerably to the mortality burden, thereby highlighting an area of focus for future interventions. Furthermore, our reported mortality rates may still be underestimated, as our study sample does not capture those deaths that occur outside the hospital or in the emergency room.

Demographic and socioeconomic factors associated with post-COVID CV-related readmissions

Demographic factors, such as age and sex, have been shown to have a significant association with adverse COVID-19 outcomes. For instance, increasing age, as well as male sex, is a marker of poor outcomes.32, 33, 34 Our study extends these findings beyond the index admission to 30-day readmission. More importantly, socioeconomic disparities were uncovered by the pandemic in the US, with the most vulnerable population groups at risk for the greatest complications.35,36 Our study enhances the existing literature by revealing that post-COVID-19 CV-related readmissions and mortality rates were highest among individuals in the lowest socioeconomic groups. This finding highlights the significance of our current analysis, as it incorporates unique features specific to the US population, including annual household incomes and insurance status, with a particular focus on Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. Prior to our study, such associations between these factors and COVID-19- and CV-related readmissions had not been well described, particularly at the national level. These findings warrant an urgent public health intervention, with a focus on underserved groups. Although racial disparities are well documented, we were not able to take those into account, as the NRD does not report data on race/ethnicity.

Healthcare cost utilization

We also report US national cost estimates for the burden of COVID-19 related to CV causes, which have not been explored before. The pandemic paralyzed the healthcare systems in many countries, including the US.37 Now that the peak of the pandemic is over and we enter the postpandemic era, in which COVID-19 appears to have taken on an endemic pattern, the financial burden of CV complications through COVID-19 continues to linger.38 Our study provides national estimates of the cost to the healthcare system during the episode of readmission. Furthermore, events beyond readmission, such as increased rates of tracheostomy and need for PEG tubes, as well as the need for skilled nursing facilitites, adds to the cumulative financial burden.

Limitations

Our study is constrained by the following limitations. First, the NRD cannot capture deaths that occur outside of the hospital. Hence, our study estimates should be interpreted as 30-day readmission mortality and not as 30-day mortality. Second, granular data, such as home medications with their doses, inpatient treatment regimens, and laboratory data, such as blood chemistry, radiologic findings, and echocardiographic findings, are lacking. Third, the NRD is an administrative, claims-based database that uses ICD-10-CM codes for diagnosis and identification of procedures. Although data based on procedural codes are less likely to contain error, coding errors and variability cannot be excluded entirely. Also, the nature of the database means that the study outcomes were not centrally adjudicated but rather defined by the ICD-10 codes used. However, the HCUP does have internal validation and quality control measures to minimize coding errors and ensure accurate reporting of data.

Fourth, although we performed multivariable logistic regression analysis to report adjusted estimates, residual confounding cannot be ruled out completely. Fifth, collider bias is well documented in recent observational studies evaluating COVID-19.39,40 Although we did not restrict our study sample to any particular group, and the NRD provides a random sample of the US population, the introduction of bias through adjustment for variables in the logistic regression model may still have occurred. Sixth, our study captured outcomes that occurred during the first year of the pandemic, in 2020, when vaccines were not available. Hence, we could not study outcomes stratified by vaccination status.

The NRD data for the years 2021 and 2022 currently are not available to the public. Hence, a new analysis of the readmission rates and reasons following hospitalization for COVID-19 would be appropriate when the latest data become available in the postvaccine era. In this regard, our study can serve as a benchmark for future research, allowing for a comparison of readmission rates for COVID-19-related CV causes across the US healthcare system at the national level, for both vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals. This comparison will provide valuable insights into changes in the trends of readmission rates for vaccinated individuals, vs what can be gleaned from data collected during the peak of the pandemic in the current study. Vaccination against the influenza virus already has been demonstrated to reduce CV risk,41 and one would anticipate that COVID-19 vaccination would have a similar impact on reducing CV outcomes. The seventh point to consider is that even though a significant reduction in COVID-19 hospitalizations has occurred recently, our study was conducted during the peak of the pandemic and hence may not reflect current COVID-19 readmission rates. However, an important point to note is that because COVID-19 virus remains present in the community, it continues to increase the risk of CV complications in susceptible patients, similar to the influenza virus.41,42 Therefore, our study's data are valuable in providing ongoing insight into the prevalence, rates, and epidemiology of CV complications following the initial hospitalization for COVID-19 infection. Finally, as with any observational, retrospective study, association does not imply causation, and conclusions are hypothesis-generating and should be interpreted cautiously.

Conclusions

In our national cohort study of the US population, among survivors of index COVID-19 hospitalization, 44.3% of all 30-day readmissions were attributed to CV causes. Acute HF remains the most common cause of COVID-19 readmission, followed closely by acute MI. CV causes of readmissions remain a significant source of mortality, morbidity, and resource utilization, as compared with non-CV causes of readmissions. In addition, the rates of CV-related readmissions were the highest for vulnerable population groups belonging to lower quartiles of income, as well as individuals with a high comorbidity burden. Moreover, the first week after discharge remains the period in which patients are most vulnerable to CV-related readmissions.

These findings warrant public health intervention, as well as reforms at the level of hospital systems, to implement strategies for the prevention of CV-related readmissions among patients discharged following COVID-19 hospitalization, with a special focus on vulnerable population groups in the first week following discharge. Prevention of CV-related readmissions will have broad implications in lowering the financial burden on an already strained healthcare system. The current findings in this study may help policymakers in their decision-making and future planning. Further studies are needed to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 vaccination on CV-related readmissions, mortality, and morbidity after COVID-19 infection.

Acknowledgments

Data Availability Statement

The NRD data are publicly available. The specific data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethics Statement

Given the deidentified nature of the database, institutional review board approval and informed consent were not required for this study.

Patient Consent

Given the de-identified nature of the database, informed consent was not required for this study.

Funding Sources

E.D.M. is supported by the Amato Fund for Women's Cardiovascular Health Research at Johns Hopkins University. The other authors have no funding sources to declare.

Disclosures

Unrelated to this work, E.D.M. reports consulting for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Amarin, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Edwards Life Science, Esperion, Medtronic, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Pfizer. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

See page 565 for disclosure information.

To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit CJC Open at https://www.cjcopen.ca/ and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjco.2023.04.007.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Chilazi M., Duffy E.Y., Thakkar A., Michos E.D. COVID and cardiovascular disease: what we know in 2021. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2021;23:37. doi: 10.1007/s11883-021-00935-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bikdeli B., Madhavan M.V., Jimenez D., et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2950–2973. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Writing Committee. Gluckman T.J., Bhave N.M., et al. 2022 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on cardiovascular sequelae of COVID-19 in adults: myocarditis and other myocardial involvement, post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and return to play: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:1717–1756. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abbasi J. The COVID heart-one year after SARS-CoV-2 infection, patients have an array of increased cardiovascular risks. JAMA. 2022;327:1113–1114. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang W., Wang C.Y., Wang S.I., Wei J.C. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in COVID-19 survivors among non-vaccinated population: a retrospective cohort study from the TriNetX US collaborative networks. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;53 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vasbinder A., Meloche C., Azam T.U., et al. Relationship between preexisting cardiovascular disease and death and cardiovascular outcomes in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2022;15 doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.122.008942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen N.T., Chinn J., Nahmias J., et al. Outcomes and mortality among adults hospitalized with COVID-19 at US medical centers. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwok C.S., Abramov D., Parwani P., et al. Cost of inpatient heart failure care and 30-day readmissions in the United States. Int J Cardiol. 2021;329:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeo I., Cheung J.W., Feldman D.N., et al. Assessment of hospital readmission rates, risk factors, and causes after cardiac arrest: analysis of the US Nationwide Readmissions Database. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.12208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khera R., Dharmarajan K., Wang Y., et al. Association of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program with mortality during and after hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donnelly J.P., Wang X.Q., Iwashyna T.J., Prescott H.C. Readmission and death after initial hospital discharge among patients with COVID-19 in a large multihospital system. JAMA. 2021;325:304–306. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.21465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chopra V., Flanders S.A., O'Malley M., Malani A.N., Prescott H.C. Sixty-day outcomes among patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:576–578. doi: 10.7326/M20-5661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steiner C., Elixhauser A., Schnaier J. The healthcare cost and utilization project: an overview. Eff Clin Pract. 2002;5:143–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Overview of the Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nrdoverview.jsp Available at:

- 15.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) https://www.ahrq.gov/data/hcup/index.html Available at: [PubMed]

- 16.Kang Y., Chen T., Mui D., et al. Cardiovascular manifestations and treatment considerations in COVID-19. Heart. 2020;106:1132–1141. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Therneau T.M. A package for survival analysis in R. 20202020. R package version 3.5-5. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survival/index.html Available at:

- 18.Ramzi Z.S. Hospital readmissions and post-discharge all-cause mortality in COVID-19 recovered patients; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;51:267–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2021.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perazzo H., Cardoso S.W., Ribeiro M.P.D., et al. In-hospital mortality and severe outcomes after hospital discharge due to COVID-19: a prospective multicenter study from Brazil. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;11 doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2022.100244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi J.J., Contractor J.H., Shaw A.L., et al. COVID-19-related circumstances for hospital readmissions: a case series from 2 New York City hospitals. J Patient Saf. 2021;17:264–269. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kingery J.R., Martin P.B.F., Baer B.R., et al. Thirty-day post-discharge outcomes following COVID-19 infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:2378–2385. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06924-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banerjee J., Canamar C.P., Voyageur C., et al. Mortality and readmission rates among patients with COVID-19 after discharge from acute care setting with supplemental oxygen. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall J., Myall K., Lam J.L., et al. Identifying patients at risk of post-discharge complications related to COVID-19 infection. Thorax. 2021;76:408–411. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siripanthong B., Asatryan B., Hanff T.C., et al. The pathogenesis and long-term consequences of COVID-19 cardiac injury. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2022;7:294–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2021.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie Y., Xu E., Bowe B., Al-Aly Z. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2022;28:583–590. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01689-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katsoularis I., Fonseca-Rodríguez O., Farrington P., Lindmark K., Fors Connolly A.-M. Risk of acute myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke following COVID-19 in Sweden: a self-controlled case series and matched cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398:599–607. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00896-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knight R., Walker V., Ip S., et al. Association of COVID-19 with major arterial and venous thrombotic diseases: a population-wide cohort study of 48 million adults in England and Wales. Circulation. 2022;146:892–906. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.060785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee Y., Jehangir Q., Li P., et al. Venous thromboembolism in COVID-19 patients and prediction model: a multicenter cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22:462. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-07421-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajpal S., Kahwash R., Tong M.S., et al. Fulminant myocarditis following SARS-CoV-2 infection: JACC patient care pathways. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:2144–2152. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.03.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minhas A.S., Scheel P., Garibaldi B., et al. Takotsubo Syndrome in the setting of COVID-19. JACC Case Rep. 2020;2:1321–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jabri A., Kalra A., Kumar A., et al. Incidence of stress cardiomyopathy during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romero Starke K., Reissig D., Petereit-Haack G., et al. The isolated effect of age on the risk of COVID-19 severe outcomes: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tharakan T., Khoo C.C., Giwercman A., et al. Are sex disparities in COVID-19 a predictable outcome of failing men’s health provision? Nat Rev Urol. 2022;19:47–63. doi: 10.1038/s41585-021-00535-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abate B.B., Kassie A.M., Kassaw M.W., Aragie T.G., Masresha S.A. Sex difference in coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Magesh S., John D., Li W.T., et al. Disparities in COVID-19 outcomes by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.34147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arceo-Gomez E.O., Campos-Vazquez R.M., Esquivel G., et al. The income gradient in COVID-19 mortality and hospitalisation: an observational study with social security administrative records in Mexico. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;6 doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2021.100115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graves J.A., Baig K., Buntin M. The financial effects and consequences of COVID-19: a gathering storm. JAMA. 2021;326:1909–1910. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.18863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cutler D.M. The costs of long COVID. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3 doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holmberg M.J., Andersen L.W. Collider bias. JAMA. 2022;327:1282–1283. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Griffith G.J., Morris T.T., Tudball M.J., et al. Collider bias undermines our understanding of COVID-19 disease risk and severity. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5749. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19478-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maniar Y.M., Al-Abdouh A., Michos E.D. Influenza vaccination for cardiovascular prevention: further insights from the IAMI trial and an updated meta-analysis. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2022;24:1327–1335. doi: 10.1007/s11886-022-01748-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khan M.S., Shahid I., Anker S.D., et al. Cardiovascular implications of COVID-19 versus influenza infection: a review. BMC Med. 2020;18:403. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01816-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The NRD data are publicly available. The specific data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon request.